Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Role of Thermal Radiation Effect on Unsteady Dissipative MHD Mixed Convection of Hybrid Nanofluid over an Inclined Stretching Sheet with Chemical Reaction

1 Department of Mathematics, Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation, Green Fields, Vaddeswaram, 522302, India

2 Department of Mathematics, Vignan Nirula Institute of Technology and Science for Women, Guntur, 522009, India

3 Department of Mathematics, Narasaraopeta Engineering College (Autonomous), Narasaraopet, 522601, India

4 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Istanbul Medeniyet University, İstanbul, 34730, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Hasan Koten. Email:

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(5), 1555-1574. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.069392

Received 22 June 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) radiative chemically reactive mixed convection flow of a hybrid nanofluid (Al2O3–Cu/H2O) across an inclined, porous, and stretched sheet is examined in this study, along with its unsteady heat and mass transport properties. The hybrid nanofluid’s enhanced heat transfer efficiency is a major benefit in high-performance engineering applications. It is composed of two separate nanoparticles suspended in a base fluid and is chosen for its improved thermal properties. Thermal radiation, chemical reactions, a transverse magnetic field, surface stretching with time, injection or suction through the porous medium, and the effect of inclination, which introduces gravity-induced buoyancy forces, are all important physical phenomena that are taken into account in the analysis. A system of nonlinear ordinary differential equations (ODEs) is derived from the governing partial differential equations for mass, momentum, and energy by applying suitable similarity transformations. This simplifies the modeling procedure. The bvp4c solver in MATLAB is then used to numerically solve these equations. Different governing parameters modify temperature, concentration, and velocity profiles in graphs and tables. These factors include radiation intensity, chemical reaction rate, magnetic field strength, unsteadiness, suction/injection velocity, inclination angle, and nanoparticle concentration. A complex relationship between buoyancy and magnetic factors makes hybrid nanofluids better at heat transmission than regular ones. Thermal systems including cooling technologies, thermal coatings, and electronic heat management benefit from these findings.Keywords

The complex fluid dynamics phenomena of mixed convection arises when forced and natural convection processes combine. In heat exchangers, electronic cooling systems, and building ventilation, buoyancy-driven and externally imposed flow can significantly affect heat transfer rates and temperature distributions [1–4].

In the past few decades, nanofluids have gained attention in scientific and engineering research because of their enhanced thermal characteristics and heat transfer efficiency in energy conversion technologies, cooling units, and heat exchangers. To enhance thermophysical behavior, nanoparticles are dissolved in base fluids. These nanoparticles can be metals, metal oxides, carbides, or carbon-based substances like nanotubes. Thermal performance has been the subject of much research since Choi and Eastman [5] first presented nanofluids. Nanofluids are intriguing possibilities for improved thermal management, as basic studies, including Choi et al. [6], demonstrated that they can raise thermal conductivity even at low concentrations. Whereas mono nanofluids only contain one nanoparticle, hybrid nanofluids contain two or more. The hybrid technique is increasingly popular because the synergistic effects of particles often lead to superior thermal performance than mono nanofluids. Because of its simplicity and capacity to capture important thermal processes, the single-phase model put forth by Tiwari and Das [7] is widely used to investigate nanofluid flow and heat transfer. Increases in nanofluid thermal conductivity due to nanoparticle volume fraction have been measured by a number of experimental and numerical studies, including Yoo et al. [8] and Kang et al. [9].

It is well-established argument that the thermal conductivity of nanomaterials is higher than that of corresponding ordinary liquids [10]. Hybrid nanofluids are a modified version of conventional or single nanofluids in which there are two or more distinct nanoparticles. Different nanoparticles are dispersed in nanomaterials to produce an ordered arrangement of liquid molecules in order to increase heat conductivity [11]. The investigations [12–14] have shown that binary hybrid nanofluids have better thermophysical characteristics than single nanofluids. Many researchs have explored the volume percentage of nanoparticles [15], particle size [16], base fluids [17], and particle type [18], as well as comparing heat conductivity and heat transfer coefficients of various nanomaterials. Kumar et al. [19] considered an Al2O3 nanofluid and evaluated its thermal conductivity. When compared to water, their results demonstrated an improvement in convective heat transfer up to 28%. Alatawi [20] explored nanofluid analysis for an enhancement of heat transfer efficiency in a cavity by employing multi-walled carbon nanotube. Nasrin et al. [21] developed a regression model of nanoliquid for thermal enhancement in the interconnected regime.

Thermal science continues to research nanofluid flow on stretched surfaces to improve heat transfer for modern engineering. The inclined stretching sheet is useful in industrial processes like polymer extrusion, metal forming, and surface coating, as noted by Sakiadis [22], Magyari and Keller [23], and Bachok et al. [24]. When physical events are added, such configurations’ fluid dynamics become more complex. Magnetic fields, Joule heating, viscous dissipation, and surface mass transfer (by suction or injection) are important. These mechanisms change the boundary layer’s velocity and temperature distributions and determine thermal system efficiency. Thus, nanofluid models must include them to accurately simulate real-world heat transport scenarios and optimise industrial processes (Mahdy [25]). Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD), the study of electrically conducting fluids in magnetic fields, is important in this field. The interaction creates Lorentz forces, which oppose fluid motion and alter flow structure and thermal gradients (Alfvén [26]; Kabeel et al. [27]). Butt et al. [28] conceptualisation of a novel design intelligent computing paradigm based on artificial neural networks by utilizing radial basis function to analyse magnetohydrodynamic Williamson nanofluid 2-dimensional flow along a stretchy sheet under the impact of chemical reaction and thermal radiation in a porous medium. These effects contribute to nanofluid systems’ complicated thermal and hydrodynamic behavior and should be studied to develop next-generation thermal technologies.

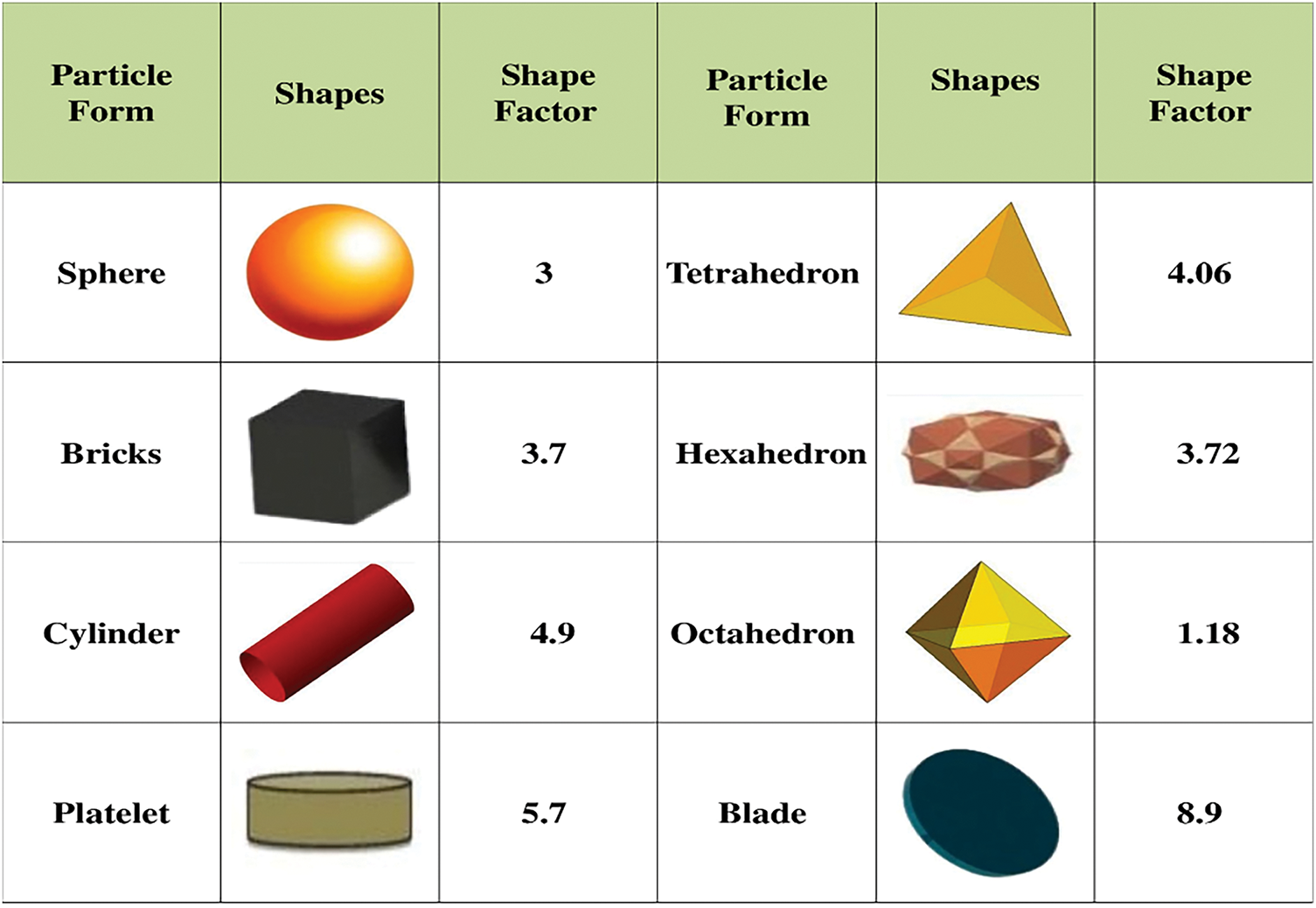

Morphology of scattered nanoparticles affects nanofluid thermal performance but is generally overlooked. The effective thermal conductivity and viscous behavior of hybrid nanofluids depend on nanoparticle form and geometry, whether spherical, cylindrical, platelet-like, or irregular. Non-spherical particles can create more efficient thermal routes and change flow resistance, improving heat transfer (Kumar et al. [29], Bakar et al. [30], Lavanya et al. [31]). These shape-dependent properties emphasize the importance of nanoparticle geometry selection for constructing nanofluids for electronic device cooling, thermal energy storage, and high-efficiency heat exchangers. Beyond nanoparticle shape, surface suction at a stretching sheet’s edge modulates boundary layer behaviour. Many engineering systems use suction to postpone boundary layer separation, reduce skin friction, and increase convective heat transfer. Suction reduces momentum and thermal boundary layer thicknesses by pushing fluid toward the surface, typically resulting in steeper thermal gradients and higher Nusselt numbers, which facilitate heat transfer (Elbashbeshy [32], Anjali Devi and Devi [33]). Additional temperature regulation is possible with suction in hybrid nanofluid flow across sloped stretching surfaces. This is useful in advanced applications, including jet impingement cooling, aerodynamic surface control, and adaptive thermal management. Thus, optimizing current heat transfer systems requires assessing suction in such settings. Upreti et al. [34], Mallesh et al. [35], Sen et al. [36], and Shaw et al. [37] show the importance of studying hybrid nanofluid thermal boundary layer phenomena. These studies emphasize the need to study nanoparticle morphology, boundary layer control mechanisms, and external factors to improve thermal efficiency in modern engineering.

Heat transfer increase and heat loss reduction in electrically conducted hybrid nanofluids rely heavily on thermal radiation. Heat radiation impacts mixed convection, making it important in physics and engineering, especially in building, gas turbines, electronics, and aerospace engineering. Investigators initiated research on a variety of hybrid nanofluid flows under different conditions with thermal radiation. Some attempts about studies in this direction can be seen through the attempts [38–42]. The effects of chemical reactions and thermal radiation on hybrid nanofluids have been investigated in a number of research [43–46].

This study analyses unsteady magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) flow of an Al2O3–Cu/water hybrid nanofluid over an inclined, permeable surface. The study focuses on Joule heating, viscous dissipation, surface suction, and nanoparticle shape factor. The single-phase technique described by Tiwari and Das [7] is used to model the hybrid nanofluid’s thermal and hydrodynamic dynamics, capturing nanoparticle dispersion’s thermal enhancements. To appropriately characterize the hybrid suspension’s thermophysical properties, the Brinkman model [47] estimates effective viscosity, and the Hamilton-Crosser correlation [48] accounts for the particle shape’s effect on heat conductivity. These models show the hybrid nanofluid’s response to flow and thermal conditions more realistically. Similarity transformations convert the partial differential equations regulating mass, motion, and energy conservation into nonlinear ordinary differential equations. Numerically solving these equations under proper boundary conditions yields velocity, temperature, and concentration, skin friction, Nusselt, and Sherwood number profiles. This study carefully evaluates how unsteadiness, magnetic field intensity, suction rate, nanoparticle form, and inclination angle affect system flow and heat transfer. This research has significant implications for designing and optimizing advanced thermal systems, such as next-generation cooling, thermal energy storage, and high-efficiency heat exchangers which are essential in modern energy, electronics, and industry.

A two-dimensional unsteady MHD boundary layer flow of a hybrid nanofluid along an inclined stretching sheet has been considered. The flow configuration is given in Figs. 1 and 2. The sheet is making an angle

Figure 1: Flow diagram

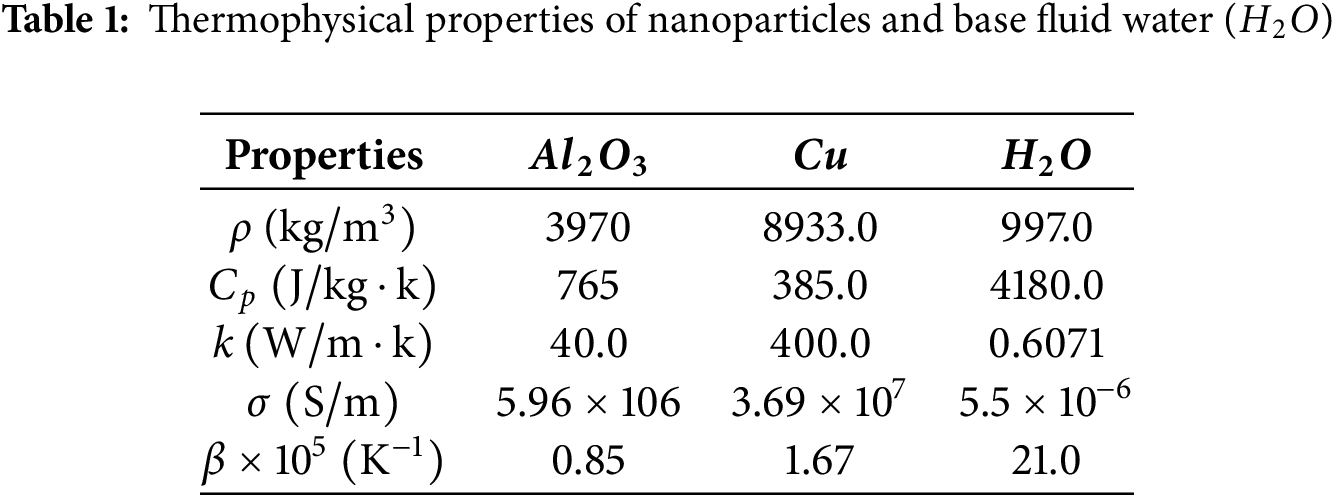

Figure 2: Flow chart bvp4c technique

Based on the assumptions outlined in the previous section, the governing equations of the system namely the continuity, momentum, and energy equations are given as follows (Ref. Mahdy et al. [25]).

Continuity equation:

Momentum equation:

Energy equation:

Concentration equation:

here Radiation flux

Now expanding Taylor series about

Boundary Conditions:

where the symbols have their usual meanings and have been mentioned in the nomenclature. For the computation of the effective value of measures of hybrid nanofluid, a number of models are available. One can apply these models by choosing an appropriate solid volume fraction of nanoparticles in the base fluid and the shape factor of nanoparticles.

Similarity Transformations:

where

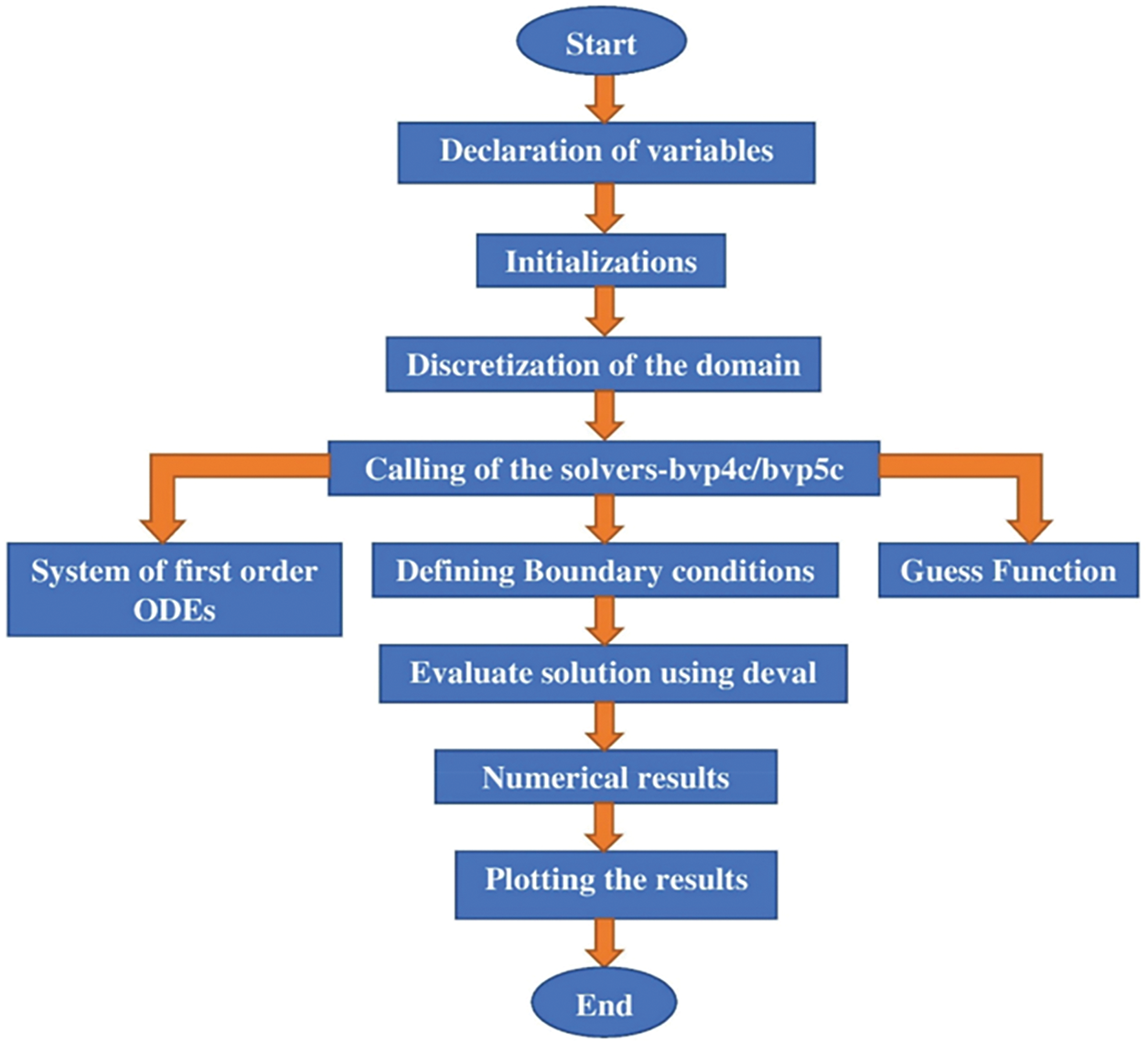

here, for effective dynamic viscosity and thermal conductivity, Brinkman [47] and Hamilton-Crosser [48] models have been used. Eq. (5) shows the expressions for the effective values of various measures (Devi & Devi [33]). Thermal characteristics of the base fluid and different nano particles are given in Table 1.

The main objective of this study is to find the shear stress and heat transfer at the sheet along with the velocity and temperature profiles. The expressions for shear stress (

By Using Eq. (6) in Eqs. (1)–(4), the equation of continuity identically satisfied which validates the corrections of the transformation used. Eqs. (2) and (3) take the following form:

Transformed boundary conditions are:

Used non dimensional parameters are defined as:

The mixed convection parameter

Where,

The dimensionless form of shear and rate of heat transfer at the surface, known as the skin friction coefficient

Numerical Procedure:

Due to the nonlinear and coupled nature of Eqs. (9)–(11) along with the associated boundary conditions outlined in Eq. (12), obtaining an analytical solution is highly challenging. To address this complexity, the numerical solver bvp4c, developed by Kierzenka and Shampine [50], is employed. This built-in MATLAB function is specifically designed to handle boundary value problems using a R-K shooting method, which ensures high accuracy and stability in solving stiff systems. Since bvp4c operates on systems of first-order ordinary differential equations, the original higher-order Eqs. (9)–(11) are transformed into an equivalent system of first-order equations using appropriate substitutions, as detailed below:

The boundary conditions are

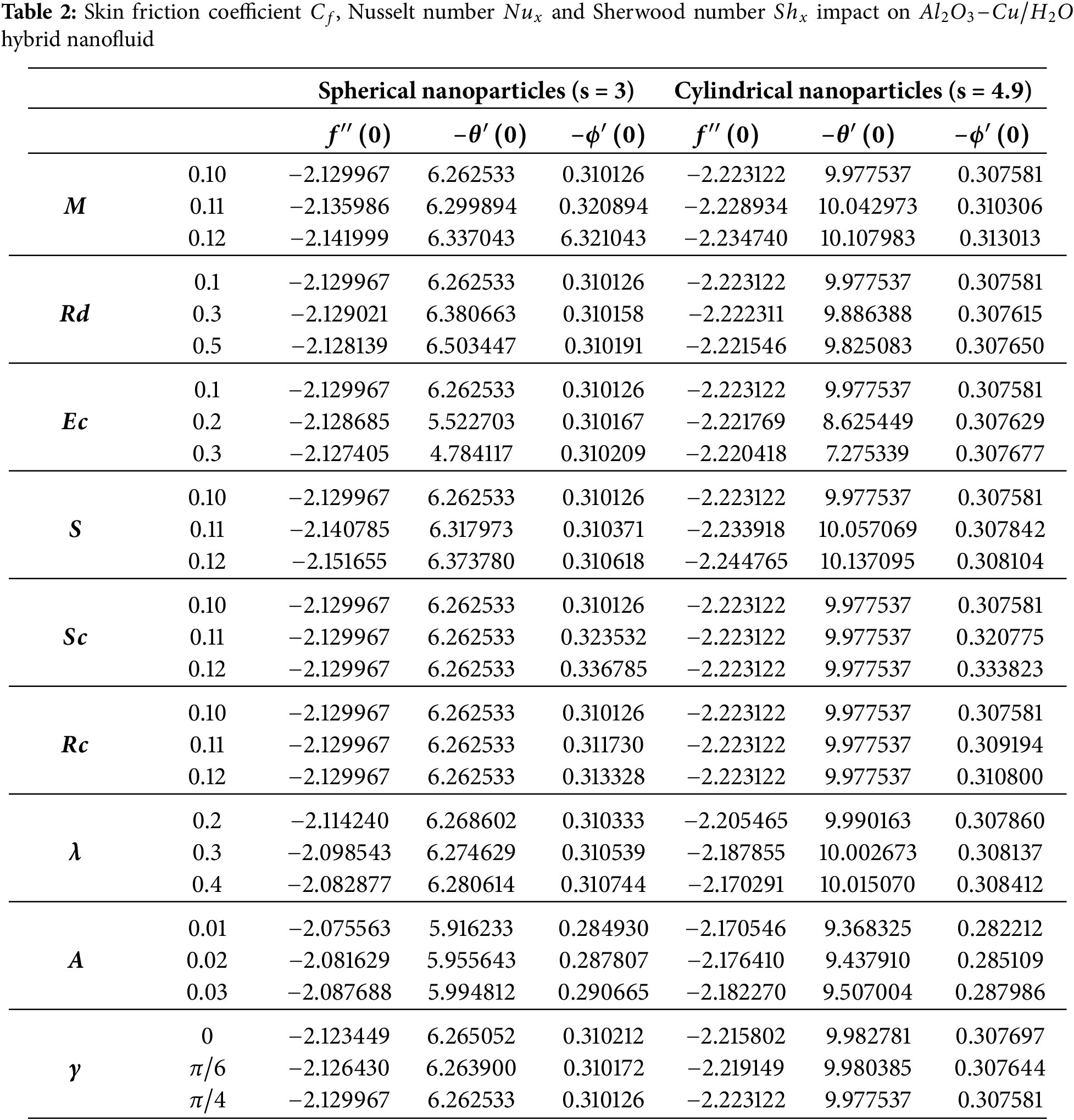

There has been a comprehensive investigation of the impact of essential influencing parameters on the distributions of concentration, temperature, and velocity, as well as on the skin friction coefficient, Nusselt, and Sherwood number by considering both spherical and cylindrical nanoparticle shapes. Figs. 3–15 depict the corresponding results, while Table 2 provides a quantitative summary. The intricate relationship between boundary layer behavior alongside external physical factors like surface suction, chemical reaction, magnetic field intensity, inclined angle, mixed convection parameter, thermal radiation, mixed convection parameter, and unsteady parameter is illustrated graphically in the results.

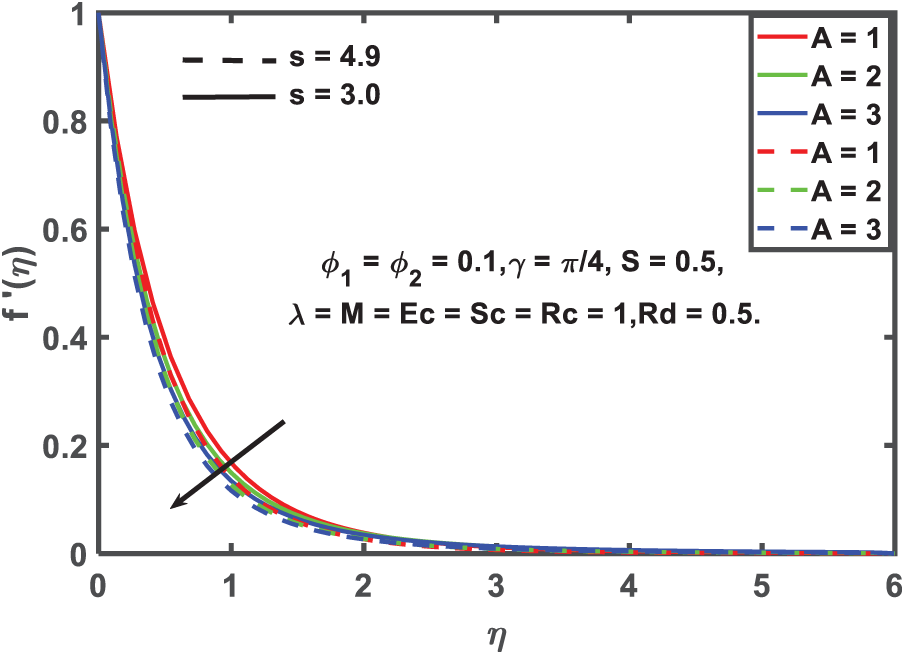

Figure 3: Velocity profile for unsteady parameter

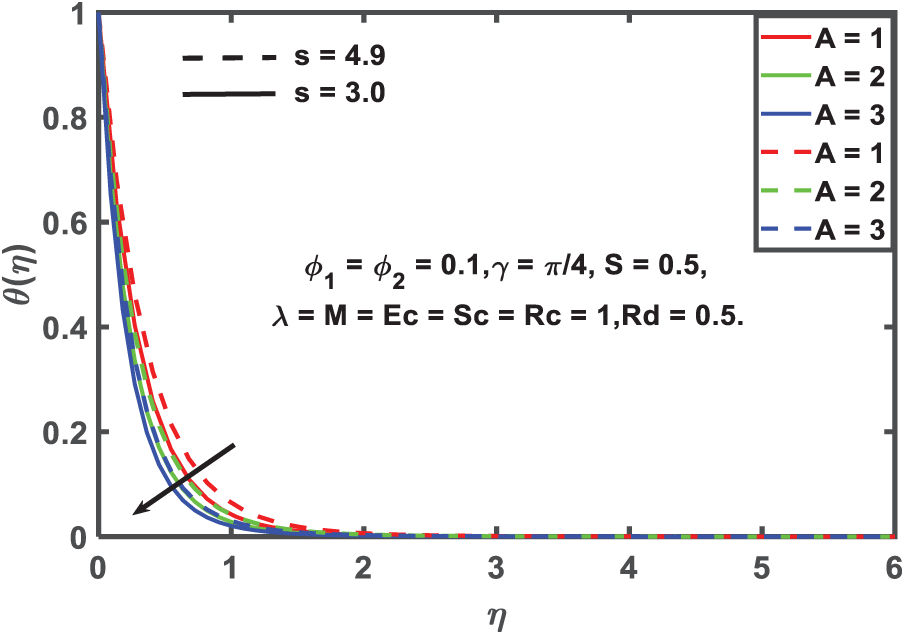

Figure 4: Temperature profile for unsteady parameter

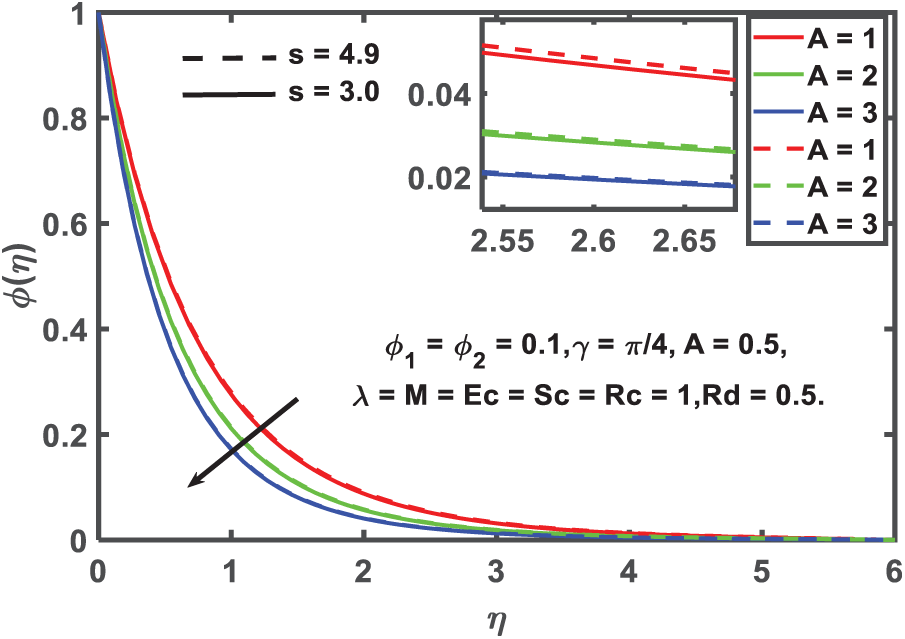

Figure 5: Concentration profile for unsteady parameter

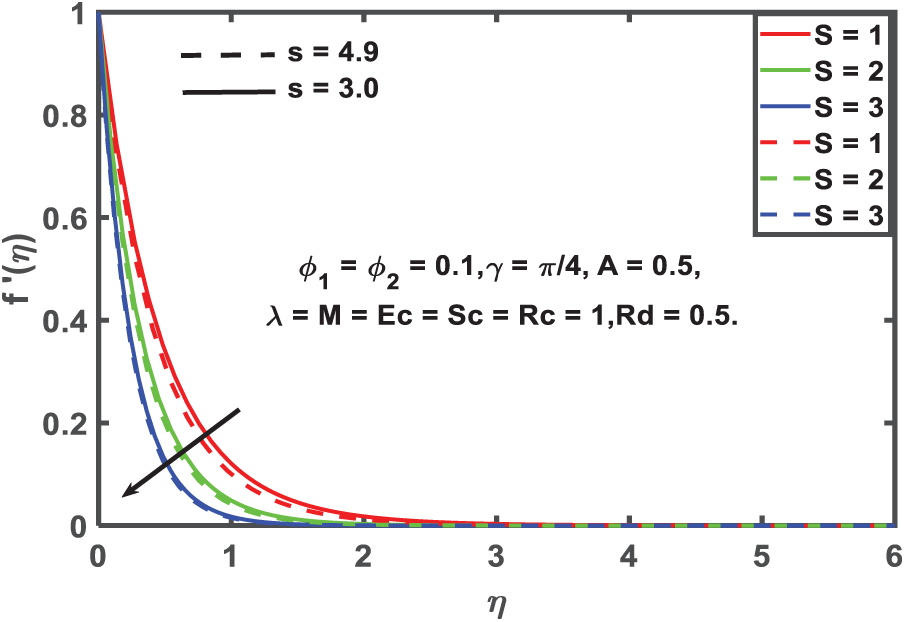

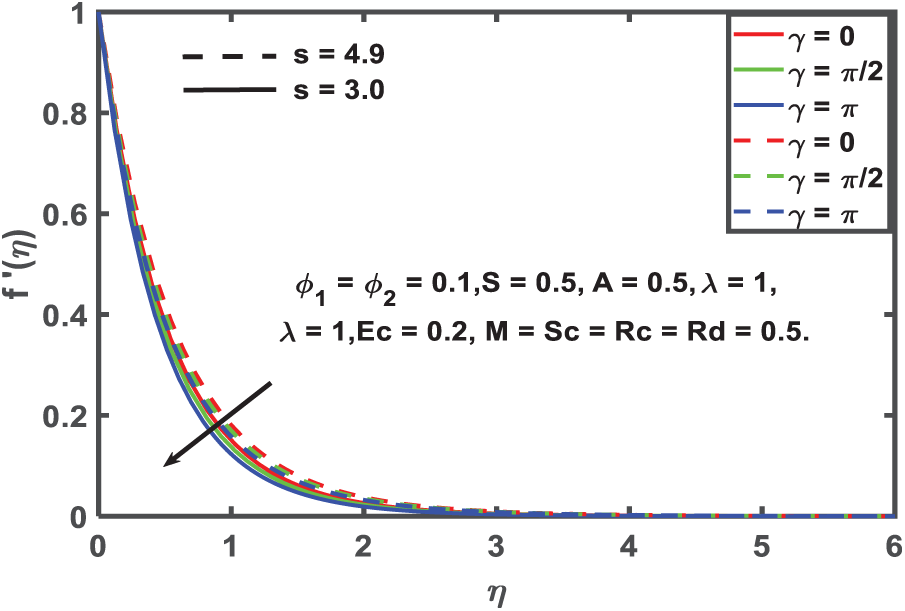

Figure 6: Velocity profile for Suction

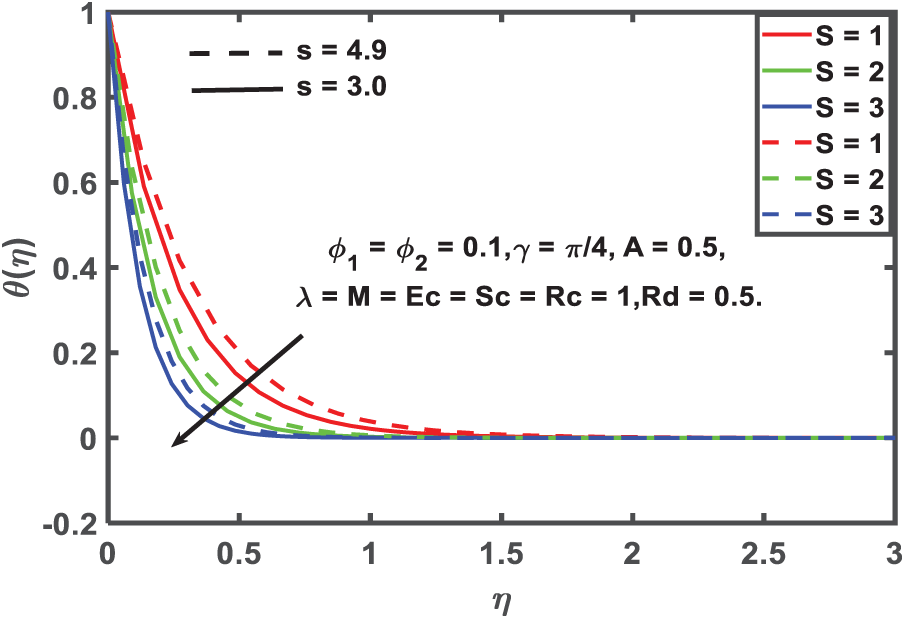

Figure 7: Temperature profile for Suction

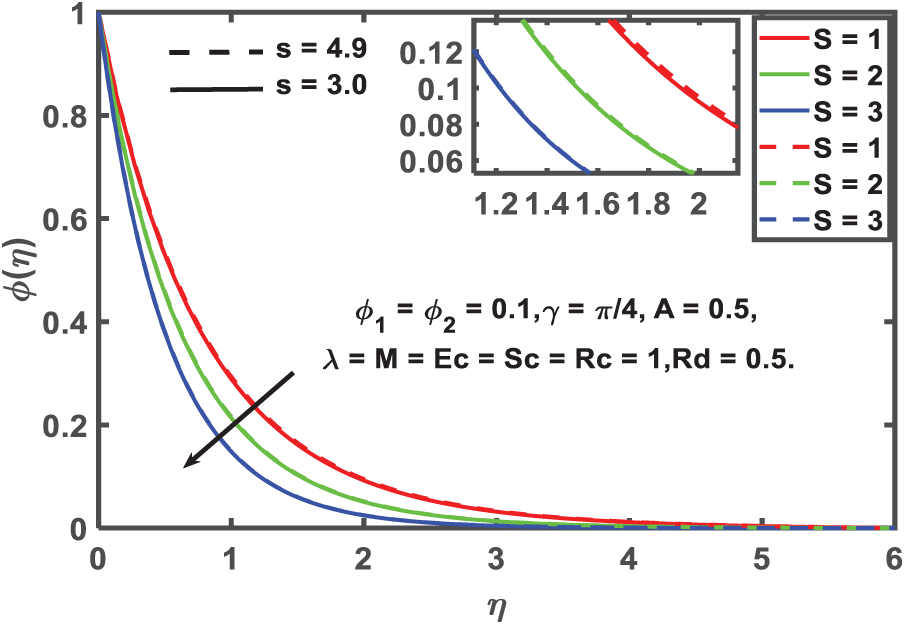

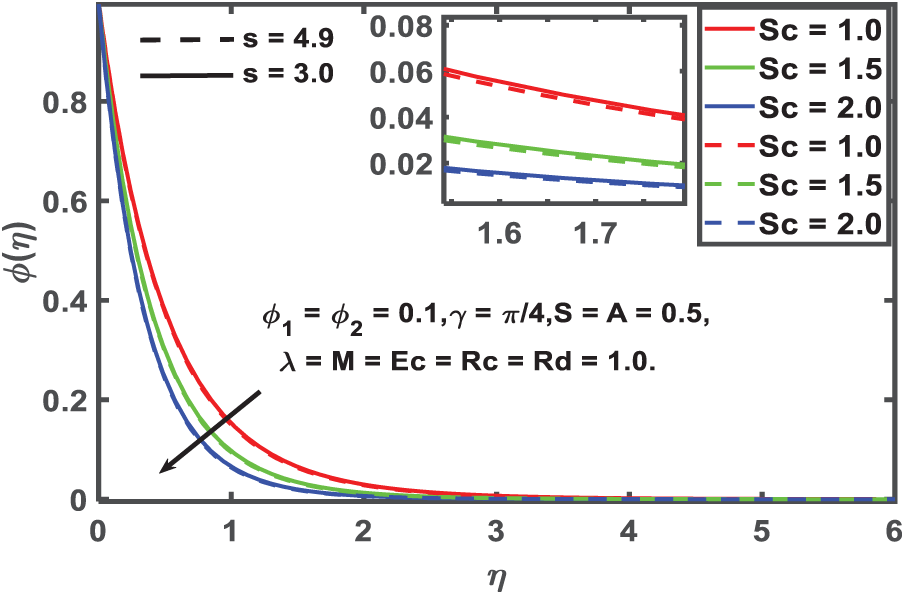

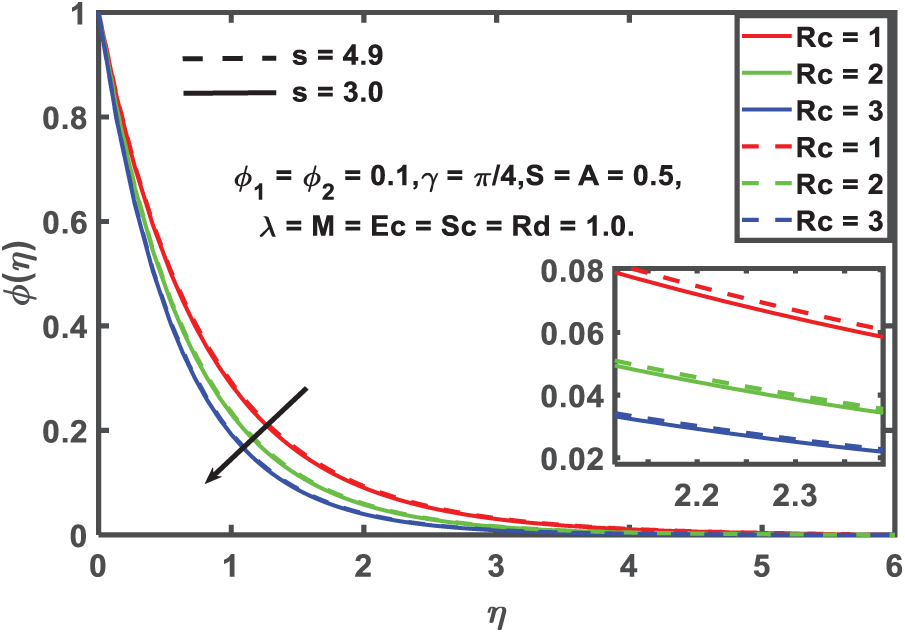

Figure 8: Concentration profile for Suction

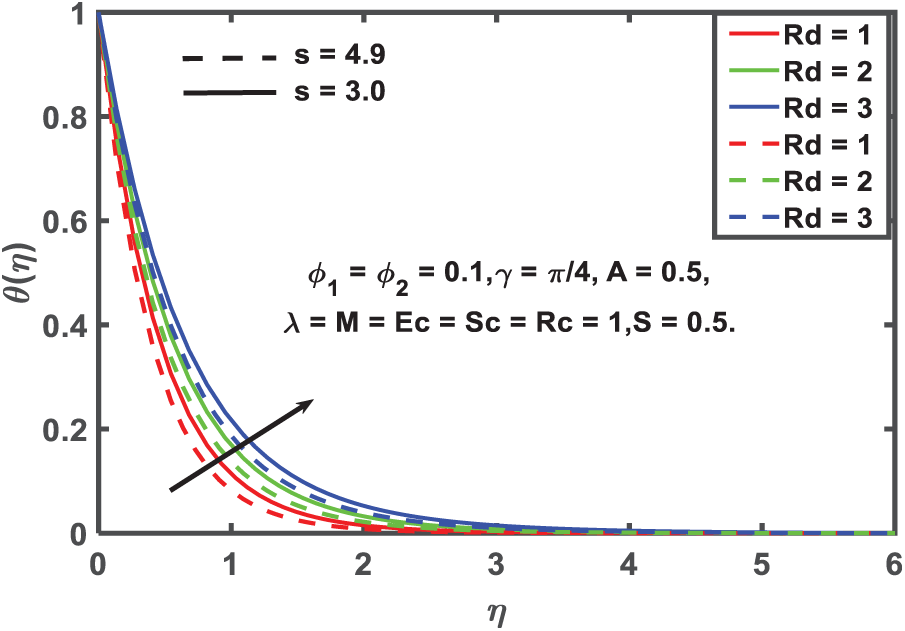

Figure 9: Temperature profile for Thermal radiation

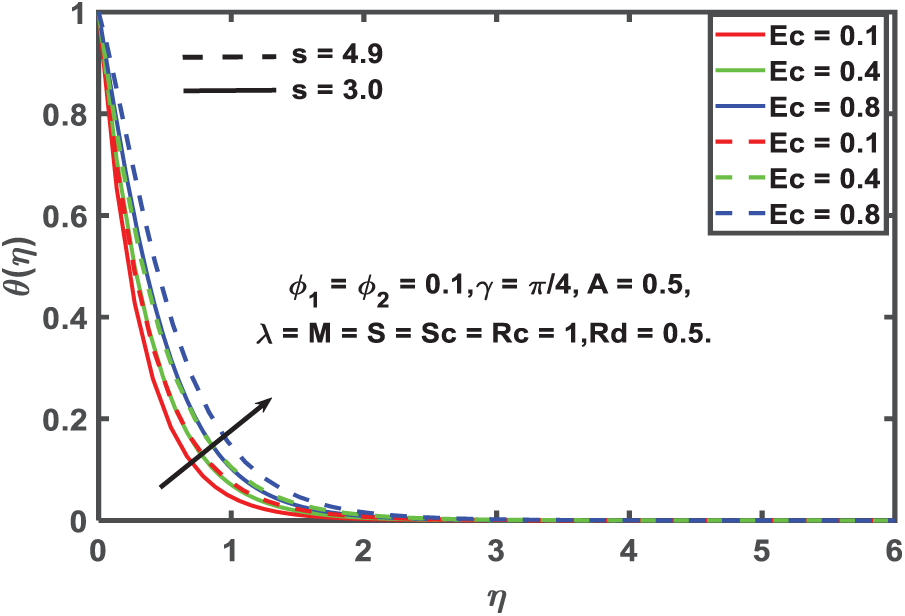

Figure 10: Temperature profile for Eckert number

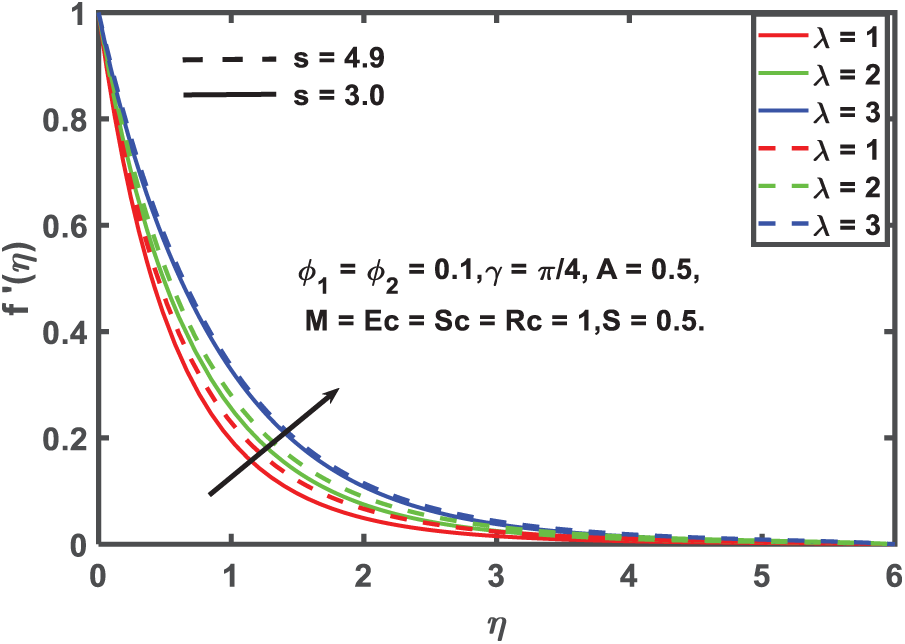

Figure 11: Velocity profile for Mixed convection parameter

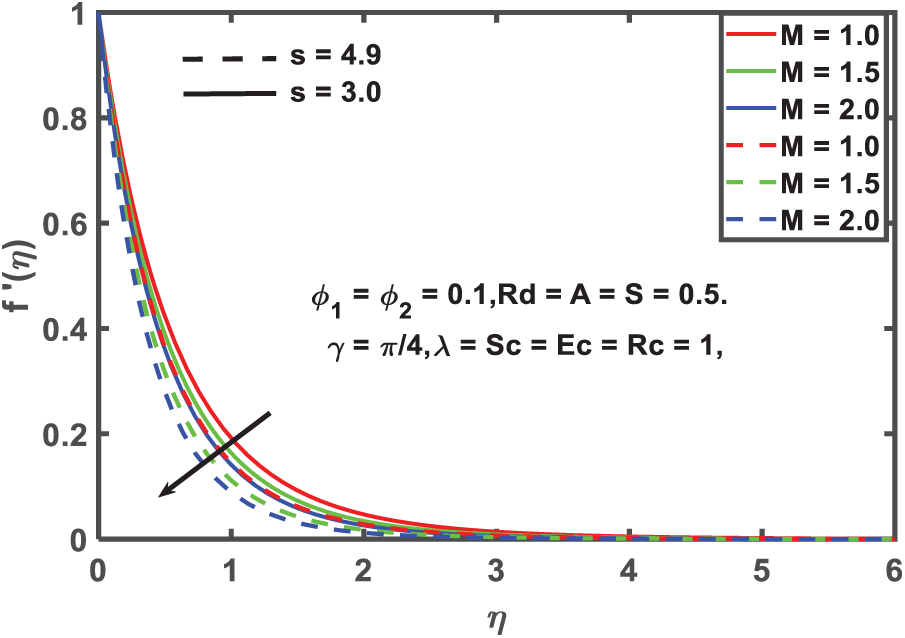

Figure 12: Velocity profile for Magnetic parameter

Figure 13: Velocity profile for aligned angle

Figure 14: Concentration profile for Schmidt number

Figure 15: Concentration profile for Chemical Reaction

According illustrated by Figs. 3–5, the velocity, temperature, and concentration properties of the hybrid nanofluid are affected by the unsteadiness parameter, which takes into account both spherical and cylindrical nanoparticle shapes. Fluid flow, temperature, and concentration all go down as the unsteadiness parameter values go up in the figures, suggesting that thermal diffusion is suppressed by transient effects. Pulsed heating in manufacturing and dynamic cooling cycles in electronics are two examples of unstable industrial processes where this is of paramount importance. Using two form variables that correspond to spherical and cylindrical nanoparticles, the impact of nanoparticle shape is additionally examined. Because of their larger surface area and the drag forces acting upon them, cylindrical nanoparticles have lower velocity profiles, whereas spherical nanoparticles display a more consistent distribution of temperatures. These results are directly applicable to the development of hybrid nanofluids for bio-thermal applications, microelectronic thermal management, and enhanced cooling fluids for the aerospace and automotive industries, where the shape of nanoparticles is an important factor in thermal performance.

Figs. 6–8 show a clear trend: for both spherical and cylindrical nanoparticle forms, a rise in the suction parameter significantly lowers the velocity, temperature, and concentration profiles. The removal of fluid from the boundary layer causes the layer to become thinner and the velocity of nanofluids close to the surface to decrease, leading to this behavior. Due to reduced mass and thermal energy close to the wall, convective transport is inhibited and thermal gradients are reduced as suction becomes stronger. The total temperature distribution is reduced due to improved suction, which restricts thermal retention near the surface, because the wall temperature is higher than the ambient fluid temperature. In thermal management applications, where manipulating the boundary layer is critical, this outcome is practically significant. To reduce drag and control surface heat flux, suction is commonly used in thermal insulation systems and aerodynamic surface treatments. The results of this study lend credence to the idea that surface suction could be a useful tool for engineering systems to manage hydrodynamic and thermal boundary layers, and they provide evidence in favor of such implementations.

This is demonstrated in Fig. 9, which shows that an increase in the thermal radiation parameter (Rd) results in an increase in the distribution of fluid temperature. This effect is to be anticipated due to the fact that thermal radiation functions as an additional source of heat, hence boosting the total mechanism of heat transmission. The thermal boundary layer is the zone that is characterized by the presence of temperature gradients between the heated surface and the fluid that comprises the surrounding environment. An rise in Rd results in a greater amount of radiative energy penetrating deeper into the fluid, which in turn causes the boundary layer to expand. Because of this, the temperature of the diffusion increases, and the heated zone that is contained within the convective region of the convective flow expands.

Fig. 10 examines the influence of the Eckert number, which measures the speed of viscous dissipation, or the transformation of kinetic energy into thermal energy resulting from internal friction within the fluid, on temperature profiles. With an increase in the Eckert number, temperature profiles demonstrate upward trends. This improvement results from increased internal heat generation, leading to a thicker thermal boundary layer and higher fluid temperatures. The implications of these findings are relevant to engineering systems that exhibit high shear rates or rapid fluid motion, including high-speed journal bearings, microchannel cooling arrays, and viscous-dominated microfluidic devices. Dissipative heating is a critical factor in these contexts, affecting both thermal performance and the mechanical stability of the flow regime. However, this temperature increases results in a decrease in the Nusselt number, signifying a reduction in the efficiency of heat transfer from the surface to the fluid.

Fig. 11 demonstrates the beneficial effect of the mixed convection parameter on the velocity field, highlighting the contribution of buoyancy forces to the flow enhancement. With an increase in this parameter, the influence of the thermal gradient becomes more significant, facilitating fluid acceleration. Mixed convection mechanisms are critical in solar collectors, electronic device cooling, and HVAC systems, where accurate control of natural and forced convection is necessary.

Fig. 12 illustrates the impact of the magnetic field parameter on the velocity characteristics of hybrid nanofluid, considering various nanoparticle shape factors, demonstrating the typical behavior of electrically conducting fluids in magnetic fields. An improvement in the magnetic field number is associated with a reduction in the significant velocity segment u. This is because u, the important velocity component, decreases as the magnetic field number increases. As expected initially, a gradual decrease in velocity can be observed as a result of raising the magnetic field number M. This result follows from the standard interpretation, which states that the capacitive field immediately preceding the electrically manipulated liquid’s ascent to the opposite force category appears to supply the Lorentz strength. The observation of this phenomenon is what prompted this change. After being hit by the aforementioned strengths, the indicators of the liquid streamlet eventually reached a point where they stalled in the thrust boundary stratum thicknesses. This happened as the fluid stream’s velocity decreased. This behavior is particularly significant in magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) applications, where magnetic fields regulate flow and temperature in electrically conductive fluids. Examples include thermal management in nuclear reactors, magnetic guidance in biomedical fluid systems, and temperature control in metallurgical casting or smelting operations. Analyzing the thermal response to different magnetic field intensities is essential for enhancing performance and maintaining stability in these systems.

For both spherical and cylindrical nanoparticle geometries, Fig. 13 displays the way the aligned angle (γ) affects the velocity field. The distinctive drop in velocity away from the surface, observed in boundary layer flows, is indicated by the fact that the fluid velocity decreases with increasing aligned angle in both instances. Cylindrical nanoparticles with greater inclination angles

Fig. 14 provides a description of the behavior of the Schmidt number (Sc) on the concentration contours. There is a variable known as the Schmidt number Sc that is utilized for the purpose of describing the ratio of mass diffusivity to speed diffusivity. It provides a specification of the equivalent relevance of speed and mass transmission by utilizing dispersion in the hydrodynamic boundary layer. This is accomplished by the utilization of water. The mass dispersion of the fluid will decrease in a manner that is proportional to the decrease in the Schmidt numeral. Fig. 15 presents an investigation of the impact that a chemical reaction has on concentration silhouettes. This analysis is illustrated in the figure. The scope of this inquiry includes the discussion of a chemical response that is destructive (Kr > 0). With an increase in the number of chemical processes, the diffusions of concentration become more constrained. The chemistry is accompanied by a physical manifestation that is distinguished by a significant number of disturbances with the intention of causing damage. The concentration distributions of fluid flow are reduced as a result of increased molecular mobility, which leads to an increase in conveyance spectacles. This is the consequence of the increased molecular mobility.

The numerical results for skin friction, Sherwood number, and Nusselt number are shown in Table 2 for spherical and cylindrical nanoparticles of hybrid nanofluids. Increasing the parameters Magnetic field parameter, diminishes the drag coefficient. Conversely, enhancing the parameter missed convective parameter raises the drag coefficient. Higher values of viscous dissipation result in reduced the heat transfer rate (Nusselt number), while larger values of

Figure 16: The appearance of nanoparticles and their shape factor Ali Akbar et al. [51]

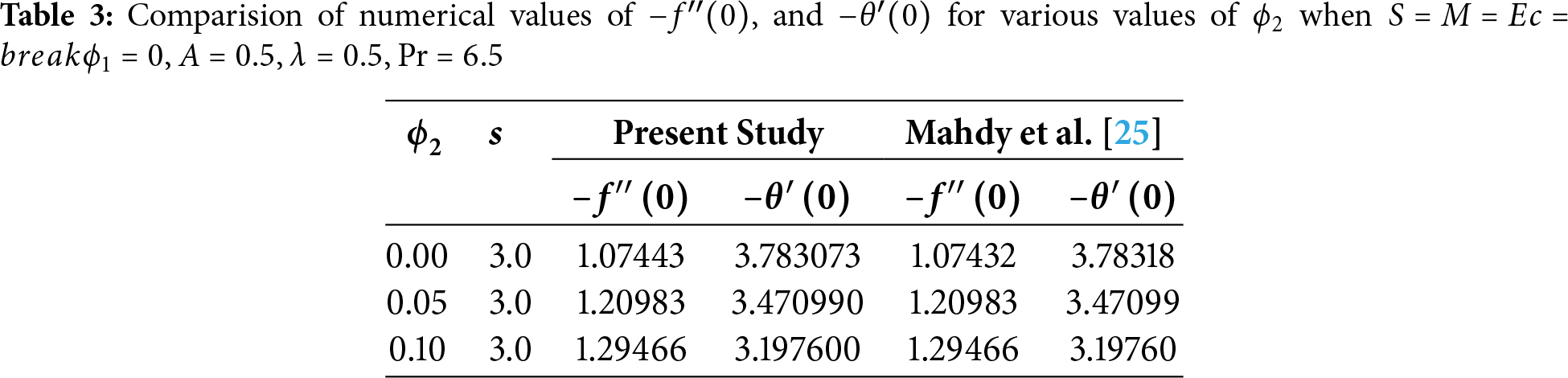

Validation of Procedure: The correctness of bvp4c code for the present problem is verified by comparing the values of

Closing remarks:

An in-depth analysis of the coupled effects of chemical, thermal radiation, viscous dissipation, Joule heating, surface suction, and nanoparticle geometry is described in this study, which examines the unsteady magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) flow of a water-based hybrid nanofluid containing

• The increase in the magnetic parameter and Eckert number leads to higher fluid temperatures, attributed to enhanced Joule heating and viscous dissipation, which both contribute to increased internal energy generation and thermal diffusion.

• An increase in suction strength and magnetic field intensity results in a significant decrease in fluid velocity and wall shear stress, due to enhanced resistance forces within the boundary layer that obstruct near-wall fluid motion.

• The temperature profile is elevated by an increase in the parameters

• Cylindrical nanoparticles exhibit superior thermal conduction compared to spherical nanoparticles, leading to enhanced temperature gradients and more effective heat transport within the fluid domain.

• Among all tested nanofluid configurations, the

Future work: Future goals include incorporating non-Newtonian fluid models and complex nanoparticle interactions, exploring time-dependent magnetic and non-linear radiative effects, and extending the model to three-dimensional geometries with experimental validation for applications in industrial solar energy and thermal management systems.

Applications: This research enhances the understanding of hybrid nanofluid dynamics in magnetohydrodynamic flow environments and offers insights for optimizing thermal management systems. The findings have significant implications for the design of advanced cooling technologies, such as high-efficiency heat exchangers, intelligent energy storage systems, and thermal management devices in electronics, aerospace, and process industries.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, Shaik Mohammed Ibrahim; Software, writing—review and editing, Bhavanam Naga Lakshmi; Investigation, resources, Chundru Maheswari; Supervision, Hasan Koten. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Requests for data can be made at any time.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Base fluid | |

| Free Stream Conditions | |

| Conditions at the wall | |

| Magnetic parameter | |

| Reynold approximation | |

| Eckert Number | |

| First kind Nanoparticle volume fraction (Al2O3) | |

| Second kind Nanoparticle volume fraction (Cu) | |

| Suction/Injection | |

| Rc | Chemical reaction |

| Kinematic viscosity (m2/s) | |

| Free stream heat | |

| Stream function (kg/ms) | |

| Specific heat | |

| Magnetic field | |

| Schmidt number | |

| Rd | Thermal radiation |

| Nanoparticle shape factor | |

| Suction/injection velocity | |

| Constants | |

| Electrical Conductivity | |

| Similarity Variable | |

| Cartesian coordinates | |

| Unsteady parameter | |

| Local Grashof number | |

| Prandtl Number | |

| Thermal conductivity | |

| Heat capacitance of the base fluid (J/K) | |

| Velocity components along x and y axes resp. (m/s) | |

| Velocity of stretching the sheet | |

| Ambient constant of velocity | |

| Angle of inclination from x-axis | |

| Chemical reaction parameter | |

| Temperature (K) | |

| Dynamic viscosity (Pa s) | |

| Density (kg/m3) | |

| Shear stress (Pa) | |

| Mixed convection parameter | |

| Gravitational acceleration | |

| Thermal expansion coefficient | |

| Heat flux | |

| Mass diffusivity |

References

1. Wahid NS, Md Arifin N, Khashi'ie NS, Pop I, Bachok N, Hafidzuddin MEH. MHD mixed convection flow of a hybrid nanofluid past a permeable vertical flat plate with thermal radiation effect. Alex Eng J. 2022;61(4):3323–33. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2021.08.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Abood FA, Radhi ZK, Hadi AK, Homod RZ, Mohammed HI. MHD mixed convection of nanofluid flow Ag-Mgo/water in a channel conta in a rotational cylinder. Int J Thermofluids. 2024;22(22):100713. doi:10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Maya MUM, Alam MN, Ali AR. Influence of magnetic field on MHD mixed convection in lid-driven cavity with heated wavy bottom surface. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):18959. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-45707-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Konwar H, Bendangwapang, Jamir T. Mixed convection MHD boundary layer flow, heat, and mass transfer past an exponential stretching sheet in porous medium with temperature-dependent fluid properties. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2023;83(12):1346–64. doi:10.1080/10407782.2022.2104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Choi SU, Eastman JA. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. Argonne, IL, USA: Argonne National Lab; 1995. Report No.: ANL/MSD/CP-84938. [Google Scholar]

6. Choi SUS, Zhang ZG, Yu W, Lockwood FE, Grulke EA. Anomalous thermal conductivity enhancement in nanotube suspensions. Appl Phys Lett. 2001;79(14):2252–4. doi:10.1063/1.1408272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tiwari RK, Das MK. Heat transfer augmentation in a two-sided lid-driven differentially heated square cavity utilizing nanofluids. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2007;50(9–10):2002–18. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2006.09.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yoo DH, Hong KS, Yang HS. Study of thermal conductivity of nanofluids for the application of heat transfer fluids. Thermochim Acta. 2007;455(1–2):66–9. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2006.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kang HU, Kim SH, Oh JM. Estimation of thermal conductivity of nanofluid using experimental effective particle volume. Exp Heat Transf. 2006;19(3):181–91. doi:10.1080/08916150600619281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dhinesh Kumar D, Valan Arasu A. A comprehensive review of preparation, characterization, properties and stability of hybrid nanofluids. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;81(10):1669–89. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Xuan Z, Zhai Y, Ma M, Li Y, Wang H. Thermo-economic performance and sensitivity analysis of ternary hybrid nanofluids. J Mol Liq. 2021;323(56):114889. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ma M, Zhai Y, Yao P, Li Y, Wang H. Synergistic mechanism of thermal conductivity enhancement and economic analysis of hybrid nanofluids. Powder Technol. 2020;373:702–15. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2020.07.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Huminic G, Huminic A. Entropy generation of nanofluid and hybrid nanofluid flow in thermal systems: a review. J Mol Liq. 2020;302:112533. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2020.112533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Soltani F, Toghraie D, Karimipour A. Experimental measurements of thermal conductivity of engine oil-based hybrid and mono nanofluids with tungsten oxide (WO3) and MWCNTs inclusions. Powder Technol. 2020;371(2):37–44. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2020.05.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Qiu L, Zhu N, Feng Y, Michaelides EE, Żyła G, Jing D, et al. A review of recent advances in thermophysical properties at the nanoscale: from solid state to colloids. Phys Rep. 2020;843:1–81. doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2019.12.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Teng TP, Hung YH, Teng TC, Mo HE, Hsu HG. The effect of alumina/water nanofluid particle size on thermal conductivity. Appl Therm Eng. 2010;30(14–15):2213–8. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2010.05.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Pryazhnikov MI, Minakov AV, Rudyak VY, Guzei DV. Thermal conductivity measurements of nanofluids. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2017;104(4):1275–82. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2016.09.080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Khanafer K, Vafai K. A critical synthesis of thermophysical characteristics of nanofluids. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2011;54(19–20):4410–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2011.04.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kumar N, Sonawane SS, Sonawane SH. Experimental study of thermal conductivity, heat transfer and friction factor of Al2O3 based nanofluid. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2018;90(4):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2017.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Alatawi ES. Enhancing heat transfer efficiency through controlled magnetic flux in a partially heated circular cavity using multi-walled carbon nanotube nanofluid and an internal square body. Sustainability. 2024;16(23):10632. doi:10.3390/su162310632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Nasrin R, Hasan S, Alatawi ES, Biswas C. Regression model featuring nanofluid in interconnected domain: an innovative way of thermal enhancement. J Nanofluids. 2024;13(5):1145–64. doi:10.1166/jon.2024.2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sakiadis BC. Boundary-layer behavior on continuous solid surfaces: i. Boundary-layer equations for two-dimensional and axisymmetric flow. AlChE J. 1961;7(1):26–8. doi:10.1002/aic.690070108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Magyari E, Keller B. Heat and mass transfer in the boundary layers on an exponentially stretching continuous surface. J Phys D Appl Phys. 1999;32(5):577–85. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/32/5/012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Bachok N, Ishak A, Pop I. Boundary layer flow and heat transfer with variable fluid properties on a moving flat plate in a parallel free stream. J Appl Math. 2012;2012(1):372623. doi:10.1155/2012/372623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mahdy A. Unsteady mixed convection boundary layer flow and heat transfer of nanofluids due to stretching sheet. Nucl Eng Des. 2012;249:248–55. doi:10.1016/j.nucengdes.2012.03.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alfvén H. Existence of electromagnetic-hydrodynamic waves. Nature. 1942;150(3805):405–6. doi:10.1038/150405d0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kabeel AE, El-Said EMS, Dafea SA. A review of magnetic field effects on flow and heat transfer in liquids: present status and future potential for studies and applications. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;45(1):830–7. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Butt ZI, Raja MAZ, Ahmad I, Hussain SI, Shoaib M, Ilyas H. Radial basis kernel harmony in neural networks for the analysis of MHD Williamson nanofluid flow with thermal radiation and chemical reaction: an evolutionary approach. Alex Eng J. 2024;103(10):98–120. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.06.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kumar A, Ray AK, Saha S, Tanwar DV, Kumar B, Sheremet MA. Flow of hybrid nanomaterial over a wedge: shape factor of nanoparticles impact. Eur Phys J Plus. 2023;138(10):901. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-023-04535-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Abu Bakar S, Ismail NS, Arifin NM. Hybrid nanofluid flow over a shrinking darcy-forchheimer porous medium with shape factor and solar radiation: a stability analysis. CFD Lett. 2024;16(11):60–81. doi:10.37934/cfdl.16.11.6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lavanya B, Kumar JG, Babu MJ. Influence of thermal radiation and shape factor on a hybrid nanofluid flow over a permeable flat plate with cross-diffusion effects: an irreversibility analysis. Numer Heat Transf Part A Appl. 2025;86(17):6003–28. doi:10.1080/10407782.2024.2337764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Elbashbeshy EMA. Heat transfer over an exponentially stretching continuous surface with suction. Arch Mech. 2001;53(6):643–51. [Google Scholar]

33. Anjali Devi SP, Devi SSU. Numerical investigation of hydromagnetic hybrid Cu-Al2O3/water nanofluid flow over a permeable stretching sheet with suction. Int J Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. 2016;17(5):249–57. doi:10.1515/ijnsns-2016-0037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Upreti H, Pandey AK, Joshi N, Makinde OD. Thermodynamics and heat transfer analysis of magnetized casson hybrid nanofluid flow via a Riga plate with thermal radiation. J Comput Biophys Chem. 2023;22(3):321–34. doi:10.1142/s2737416523400070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Mallesh MP, Makinde OD, Rajesh V, Kavitha M. Time-dependent thermal convective circulation of hybrid nanoliquid past an oscillating porous plate with heat generation and thermal radiation. J Appl Nonlinear Dyn. 2023;12(1):171–89. doi:10.5890/jand.2023.03.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Sen SS, Das M, Nayak MK, Makinde OD. Natural convection and heat transfer of micropolar hybrid nanofluid over horizontal, inclined and vertical thin needle with power-law varying boundary heating conditions. Phys Scr. 2023;98(1):15206. doi:10.1088/1402-4896/aca3d7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Shaw S, Samantaray SS, Misra A, Nayak MK, Makinde OD. Hydromagnetic flow and thermal interpretations of Cross hybrid nanofluid influenced by linear, nonlinear and quadratic thermal radiations for any Prandtl number. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;130(11):105816. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2021.105816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ullah H, Abas SA, Fiza M, Jan AU, Akgul A, El-Rahman MA, et al. Thermal radiation effects of ternary hybrid nanofluid flow in the activation energy: numerical computational approach. Results Eng. 2025;25:104062. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ali A, Kanwal T, Awais M, Shah Z, Kumam P, Thounthong P. Impact of thermal radiation and non-uniform heat flux on MHD hybrid nanofluid along a stretching cylinder. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):20262. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-99800-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Saran HL, RamReddy C. Effect of thermal radiation on aqueous hybrid nanofluid: the stability analysis. Eur Phys J Plus. 2024;139(3):209. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-024-05027-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ishak SS, Ilias MR, Kechil SA, Bosli F. Aligned magnetohydrodynamics and thermal radiation effects on ternary hybrid nanofluids over vertical plate with nanoparticles shape containing gyrotactic microorganisms. J Adv Res Numer Heat Transf. 2024;18(1):68–91. doi:10.37934/arnht.18.1.6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Arulmozhi S, Sukkiramathi K, Santra SS, Nandi S. Impact of thermal radiation on water-based hybrid nanofluid (Cu-Al2O3–H2O) flow over a forward/backward moving vertical porous plate. Arab J Sci Eng. 2025;50(1):477–87. doi:10.1007/s13369-024-09108-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Arifuzzaman M, Uddin MJ. Convective flow of alumina-water nanofluid in a square vessel in presence of the exothermic chemical reaction and hydromagnetic field. Results Eng. 2021;10(5):100226. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2021.100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Khan Y, Tufail MN, Shahzad K, Alameer A, Iqbal N. Impact of chemical reaction on thermal magnetized hybrid nanofluid over a curved stretching surface. Results Eng. 2025;27(1):105556. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.105556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Vijay N, Sharma K. Entropy generation analysis in MHD hybrid nanofluid flow: effect of thermal radiation and chemical reaction. Numer Heat Transf Part B Fundam. 2023;84(1):66–82. doi:10.1080/10407790.2023.2186989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Arshad M, Hassan A, Haider Q, Alharbi FM, Alsubaie N, Alhushaybari A, et al. Rotating hybrid nanofluid flow with chemical reaction and thermal radiation between parallel plates. Nanomater. 2022;12(23):4177. doi:10.3390/nano12234177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Brinkman HC. The viscosity of concentrated suspensions and solutions. J Chem Phys. 1952;20(4):571. doi:10.1063/1.1700493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hamilton RL, Crosser OK. Thermal conductivity of heterogeneous two-component systems. Ind Eng Chem Fund. 1962;1(3):187–91. doi:10.1021/i160003a005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sandeep N, Sulochana CK, Raju CS, Babu MJ, Sugunamma V. Unsteady boundary layer flow of thermophoretic MHD nanofluid past a stretching sheet with space and time dependent internal heat source/sink. Appl Appl Math Int J. 2015;10(1):20. doi:10.18869/acadpub.jafm.68.225.24784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kierzenka J, Shampine LF. A BVP solver based on residual control and the Maltab PSE. ACM Trans Math Softw. 2001;27(3):299–316. doi:10.1145/502800.502801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ali Akbar A, Ahammad NA, Awan AU, Hussein AK, Gamaoun F, Tag-ElDin EM, et al. Insight into the role of nanoparticles shape factors and diameter on the dynamics of rotating water-based fluid. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(16):2801. doi:10.3390/nano12162801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools