Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Modeling and Experimental Research of Heat and Mass Transfer during the Freeze-Drying of Porcine Aorta Considering Radially-Layered Tissue Properties

1 School of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Xinxiang University, Xinxiang, 453003, China

2 Postdoctoral Affairs Office, Postdoctoral Research Workstation of Hualan Biological Engineering Incorporated Company, Xinxiang, 453003, China

3 School of Energy and Power Engineering, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, 200093, China

* Corresponding Author: Yaping Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovations in Drying Technologies: Bridging Industrial, Environmental, and Energy Efficiency Challenges)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(5), 1621-1637. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.072268

Received 23 August 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

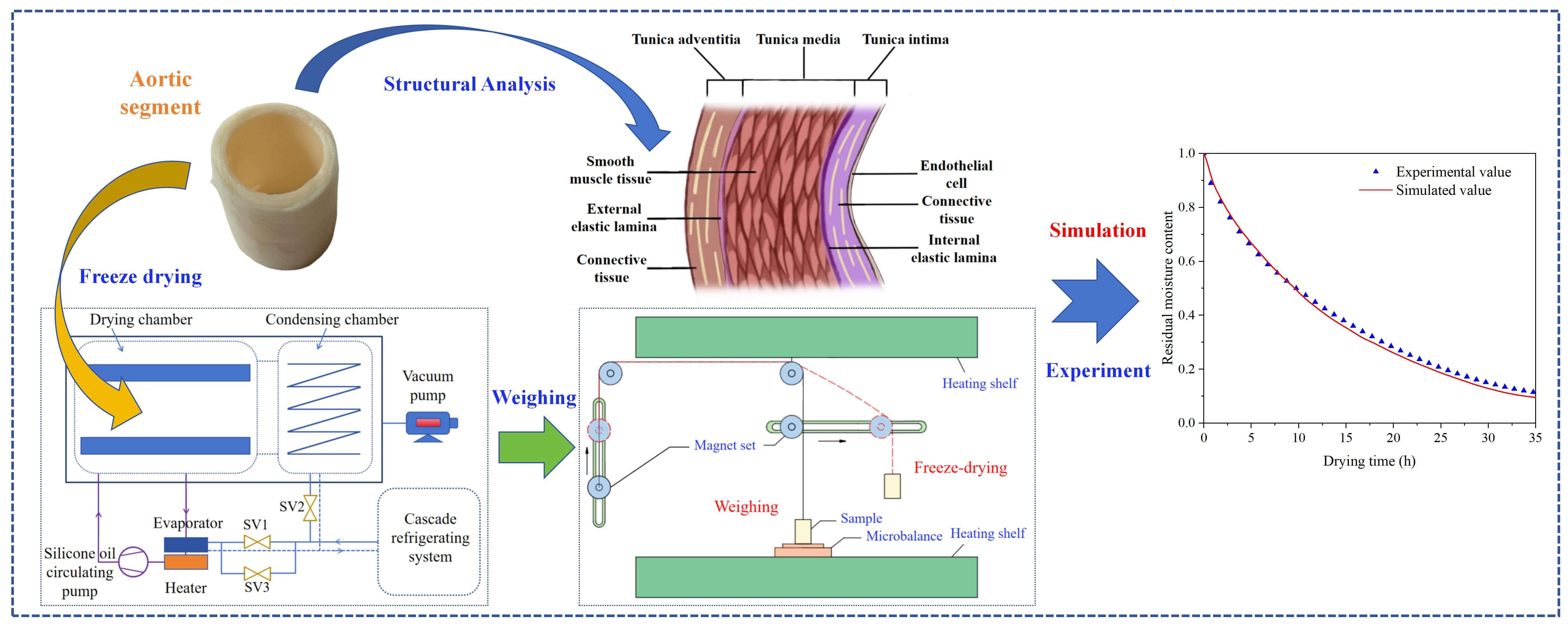

Freeze-drying of structurally heterogeneous biomaterials such as porcine aorta presents considerable modeling challenges due to their inherent multilayer composition and moving sublimation interfaces. Conventional models often overlook structural anisotropy and dynamic boundary progression, while experimental determination of key parameters under cryogenic conditions remains difficult. To address these, this study develops a heat and mass transfer model incorporating a dynamic node strategy for the sublimation interface, which effectively handles continuous computational domain deformation. Additionally, specialized fixed nodes were incorporated to adapt to the multilayer structure and its spatially varying thermophysical properties. A novel non-contact gravimetric system was introduced to monitor mass loss in real time without disrupting vacuum, enabling accurate experimental validation. Combined with dehydration data, the model quantified critical parameters including effective thermal conductivity of the dried layer, vapor diffusivity, and sublimation mass transfer resistance. The results show that the migration of the sublimation fronts from both the inner and outer tunics toward the tunica media significantly alters the drying kinetics and heat-mass transfer characteristics. The proposed approach provides an adaptable and predictive framework for simulating freeze-drying processes in structurally heterogeneous systems with spatially varying thermophysical properties.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The aorta, as a natural biological material, exhibits exceptional mechanical properties and biocompatibility, providing a functional solution for complex vascular disorders (such as aneurysms or stenosis). Relevant clinical studies have demonstrated its suitability for transplantation [1,2]. To achieve the long-term preservation and off-site application of such biological materials, vacuum freeze-drying technology has emerged as a crucial approach. This technology can mitigate immune rejection in allogeneic transplantation, thereby improving allograft survival rate [3].

Freeze-drying is a complex process involving coupled heat and mass transfer, and the process is highly sensitive to the parameter settings. As demonstrated in the studies by Jia et al. [4] on stropharia rugosoannulata and by Yan et al. [5] on pineapple, the optimization of key parameters through experimental design (e.g., orthogonal arrays) and statistical methods (such as one-way ANOVA and the Taguchi method) has proven to be an effective approach for enhancing the quality of lyophilized products. Although these methods require considerable experimental effort, they provide a reliable strategy for process optimization in the production of high-quality dried materials.

However, optimization strategies that rely exclusively on experimental approaches are inadequate for fully elucidating the underlying physical mechanisms of the drying process. This constrains their predictive accuracy and applicability in guiding the research of novel materials, particularly in the biomedical field, as the stability and efficacy of biopharmaceuticals are highly sensitive to uncontrolled freeze-drying conditions [6]. Fundamentally, precise process optimization must be grounded in a thorough understanding of the heat and mass transfer phenomena during freeze-drying. As a foundational tool for mechanistic investigation, mathematical models provide a quantitative framework for the dynamics of heat transfer, ice crystal sublimation, and sublimation front propagation. For instance, Aydin et al. [7] employed a radiation model with a moving interface to simulate the freeze-drying process of black tea extract, and Chaurasiya et al. [8] developed an analytical model incorporating convective effects to study double moving interfaces in a porous half-space.

Constructing a high-fidelity freeze-drying model requires the accurate characterization of essential material properties, particularly the key heat and mass transfer parameters. To determine the key lyophilization parameters, Aydin et al. [7] determined the key lyophilization parameters by fitting a dynamic model to experimental data using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm. Pisano et al. [9] reconstructed the internal structure of lyophilized solutions in vials using X-ray imaging. Based on this structural analysis, they estimated pore size distribution and employed mathematical models to correlate mass transfer resistance with the thickness of the dried layer. Andrieu et al. [10] utilized transient pressure rise methods to determine key lyophilization parameters such as the overall heat transfer coefficient and the vapor mass transfer resistance. Capozzi et al. [11] investigated particle accumulation structures during spray freeze-drying. Using CFD simulations, they characterized key structural parameters—including porosity, pore size distribution, surface curvature, and hydraulic permeability—to elucidate mass transfer dynamics during freeze-drying. Carfagna et al. [12] developed a method to determine heat transfer coefficients through heat flux datas and lyophilized experiments, demonstrating more efficient real-time process characterization than gravimetric analysis. Yu et al. [13] established a methodology based on tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy for real-time monitoring of vapor mass flow in individual vials during lyophilization. By combining flow velocity, temperature, and concentration data with mathematical modeling, vial-specific heat transfer coefficients and drying resistance can be determined.

The integration of experimental and modeling approaches thus offers a robust framework for addressing complex challenges in this field.

This study focuses on the aorta, a material characterized by its annular configuration and relatively thin wall. As such, the movement of its sublimation front differs from that in other lyophilized materials. Furthermore, the aortic wall is generally divided into three layers: the tunica intima, media, and adventitia [14]. The various tunicae exhibit significant differences in chemical composition, microstructure, and mechanical properties. This specific structural composition results in unique heat and mass transfer coefficients and significantly influences the characteristics of the drying process. Consequently, traditional homogeneous modeling approaches are inadequate.

Structural layering is not the only challenge, and monitoring moisture loss also presents significant difficulties. Given the minimal mass of aortic segments and their slow dehydration rate, even minor measurement inaccuracies can substantially compromise experimental outcomes. Meanwhile, the vacuum and cryogenic conditions greatly increased the difficulty of the measurement work. Therefore, developing a reliable approach to monitor moisture transport is essential for the present work.

To address these challenges, this study proposes a novel non-contact weighting system. In addition, a unique mathematical model was developed by incorporating the distinct structural characteristics of the aortic tunics. Critical physical properties during lyophilization were determined by combining experimentally acquired dehydration data with the structural-based model. This integrated approach not only enables a realistic reconstruction of the sublimation drying process within the multilayered tissue but also contributes to the enrichment of heat and mass transfer theory for complex biological systems.

In this experiment, aortic segments were freeze-dried using a TF-SFD-2 vacuum lyophilizer, and the flowchart is illustrated in Fig. 1. This system primarily consists of a cascade refrigeration unit, a thermal conductive silicone oil circulation loop, a freeze-drying chamber, and other essential components such as a heater, a vacuum pump and solenoid valves. The solenoid valve SV1 regulates the evaporator and remains open once the freezing process is initiated, which enables the cooling of the silicone oil. Following the start of the drying phase, solenoid valve SV2 is activated, enabling the cold trap temperature to decrease and commence water vapor capture. Shelf temperature is regulated by the silicone oil via the evaporator, heater, and cooling valve SV3 (automatic start-stop adjustment).

Figure 1: Freeze-drying system and samples: (a) Flowchart of freeze-drying system; (b) Annular segment of porcine aorta

This study utilized porcine aorta as the experimental material. Surface impurities were carefully removed while preserving the integrity of the connective tissue. The samples were subsequently rinsed with 0.9% physiological saline. Following this preparation, the midportion of aorta was sectioned into circular segments (as illustrated in Fig. 1) for use in freeze-drying experiments. Based on previous studies of freeze-drying protocols [3,15], the process parameters were set as follows: (1) pre-freezing temperature: 223.15 K with a duration of 3 h; (2) primary drying temperature: 253.15 K; (3) secondary drying temperature: 283.15 K; (4) chamber pressure: 2 Pa; (5) condensing temperature: 203.15 K.

Unlike typical materials, the annular structure of the aorta allows sublimation to commence from both its inner/outer cylindrical surfaces and upper/lower annular cross-sections; however, 2D micro-CT reconstructions along circumferential and axial directions during primary drying revealed that sublimation was predominantly localized to both sides of the aortic wall, with only minimal retreat observed at the upper and lower cross-sectional regions. This disparity can be attributed to the thinness of the aortic wall, which results in the surface area of these circular cross-sections amounting to less than 10% of that of the inner and outer lateral surfaces, thereby receiving insufficient radiant heat to drive significant sublimation. Furthermore, the two-dimensional reconstruction results also provided an important piece of information: the moving velocity of the inner and outer sublimation fronts were basically the same [16,17].

Given that sublimation heat was transferred primarily radially through the inner and outer surfaces, the sublimation front initiated simultaneously from both surfaces and advanced toward the center after drying commenced. The progression rates of the two sublimation fronts were largely consistent. Therefore, an experimental lyophilization protocol based on radiative heat transfer boundaries was established.

The vacuum and cryogenic conditions of lyophilization pose long-standing challenges to monitoring moisture loss. Given the slow moisture loss rate of aorta, a non-contact weighing device (Fig. 2) was employed to monitor moisture loss without disrupting the vacuum and cryogenic environment. The setup consisted of a microbalance, two set of pulley-magnet-slide rail assembly, and a fine cotton thread. Each magnet group consists of two magnets, which are respectively attached to both sides of the Acrylic plexiglass door. A rod is rigidly attached to the internal magnet and moves accordingly. Under the gravitational force of the sample, the fine cotton thread remains taut. Magnet A moves horizontally to drive the rod, which in turn adjusts the horizontal position of the sample. Magnet B moves vertically to control the height of the sample through the fine cotton thread. Through the coordinated operation of the magnet group, the sample is precisely positioned onto the microbalance for intermittent weighing. Upon completion of weighing, the sample is removed from the microbalance. Moisture loss was recorded once every hour. The instantaneous sublimation rate was calculated as the difference in moisture loss between consecutive measurements, and the process was terminated when the rate drops to an extremely low level (below 0.2 mg/min). Based on the predetermined total free water content of the aorta (approximately 71.96% of the total mass) [14], the residual water content throughout the process was derived from the cumulative mass loss data.

Figure 2: Schematic of the non-contact moisture loss monitoring system, showing the following key components: 1—Upper shelf; 2—Lower shelf; 3—Aortic segment; 4—Microbalance; 5—Magnet assembly A; 6—Slide rail A; 7—Fixed pulley A; 8—Fine cotton thread; 9—Magnet assembly B; 10—Slide rail B; 11—Fixed pulley B

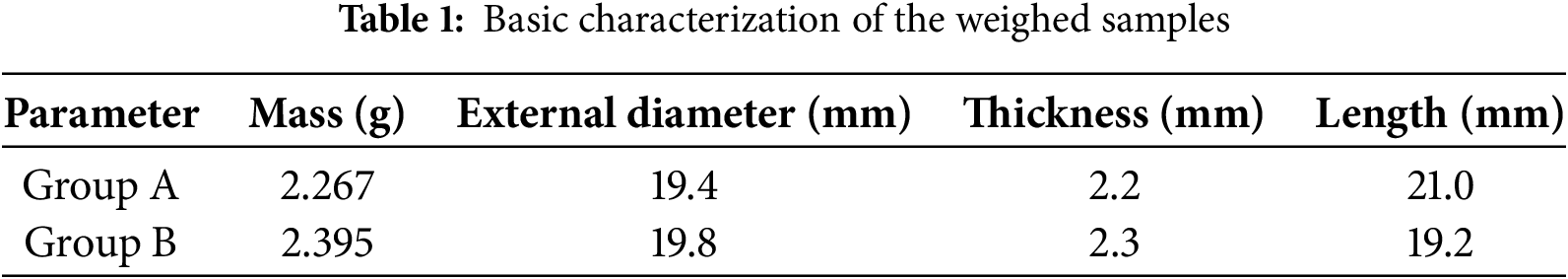

This experiment was conducted in two groups. Initially, the first set of lyophilization tests (Group A) was performed. Analysis of the dehydration data was used to determine the porosity. Combined with mathematical model, the thermal conductivity, diffusion coefficient, and the variation patterns of heat and mass transfer resistance were derived, allowing a detailed analysis of heat and mass transfer characteristics during the primary drying. Subsequently, the obtained parameters were applied to the second set of samples (Goup B) for recalculation. The accuracy of the model was validated by comparing the computational results with experimental measurements. The fundamental parameters of the weighed samples were summarized in Table 1.

3 Numerical Modeling of Heat and Mass Transfer

3.1 Aortic Wall Radial Structure

The aortic segment exhibits an annular morphology. In the radial direction from the lumen outward, it is composed of three distinct layers: the tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica adventitia, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Tunica intima comprises a single layer of endothelial cells and connective tissue. Tunica media consists predominantly of smooth muscle tissue, while tunica adventitia is primarily composed of connective tissue. Structurally, the intima and adventitia are similar in composition and thickness, each accounting for approximately one-third of the total wall thickness. In contrast, the media is considerably thicker, constituting about two-thirds of the wall, and is densely packed with elastic fibers. These elastic fibers play a critical role in maintaining the mechanical properties of the aorta. The elastic tunica, composed of elastic fibers, is sandwiched between two adjacent tunicas and is elusive under microscopic observation [14].

Figure 3: Aortic wall radial structure

The loose organization of connective tissue, which retains significant interstitial fluid, whereas the dense architecture of elastic fiber, which contains relatively less fluid. Higher moisture content leads to the formation of a greater number of ice crystals. Following lyophilization, this results in a more porous structure. These structural variations directly influence the heat and mass transfer resistances within the dried layer.

Huang et al. [18] employed a probe-based method to determine the thermal conductivity of frozen porcine aorta. Following dissection, the thermal conductivity was measured at various temperatures on a radially stacked sample configuration. Within the freeze-drying temperature range, the obtained thermal conductivity value was found to be approximately 1.314 W/(m·K). This value serves as a key parameter in this study.

Similarly, the effective thermal conductivity of dried layers and the vapor effective diffusivity in the dried layer, constitute fundamental parameters in the theoretical modeling of lyophilization processes. However, direct measurement is experimentally challenging. As an alternative, it can be computationally estimated using thermal conductivity models developed for multi-component materials. The frozen material may be conceptualized as a binary system consisting of a dried porous matrix and ice crystals. Several modeling approaches exist for predicting the effective thermal conductivity of such heterogeneous materials, among which the parallel and series models are the most widely adopted. The parallel model assumes uniform heat flux distribution, whereas the series model is based on the distribution of thermal resistances. Empirical evidence shows that the effective thermal conductivity of heterogeneous materials is bounded by the predictions of the parallel (upper limit) and series (lower limit) models. Therefore, the effective thermal conductivity can be represented by a series-parallel combination model (S-P model) [19], as described in Eqs. (1)–(3).

where φ is the volume fraction of ice phase; λice is the thermal conductivity of ice, W/(m·K); λsol is the thermal conductivity of solid phase, W/(m·K); λpar is the average thermal conductivity under parallel model, W/(m·K); λser is the average thermal conductivity under series model, W/(m·K); λave is the comprehensive average thermal conductivity, W/(m·K); β is the empirical weighting factor. Based on the analysis of relevant experimental results, the weighting coefficient for the thermal conductivity model, when applying the S-P model, ranges from approximately 0.53 to 0.86 across different temperatures, with a mean value of approximately 0.70 used for calculation [20].

As a porous medium, the effective thermal conductivity of its dried layer under vacuum conditions can be determined using Eq. (4) [21].

where λsol,eff is the effective thermal conductivity of solid phase in vacuum, W/(m·K).

3.3 Heat and Mass Transfer Model

(1) Convective heat transfer was neglected.

(2) Radiative heat transfer between the upper and lower annular surfaces was neglected.

(3) The sublimation front was smooth and infinitesimally thin.

(4) No bound water was released during the sublimation drying.

(5) Radial progression rates of the inner and outer sublimation fronts were identical.

(6) Free water was uniformly distributed within each individual tunica.

3.3.2 Mathematical Model of Heat and Mass Transfer

Establishing partial differential equations (PDE) for the freeze-drying process of the circumferential aortic segment.

(1) Energy equation of the dried layer [22]

Regarding the energy equation of the dried layer, the physical interpretation of each term is as follows:

The first term represents the net increase in internal energy per unit volume;

The second term represents the net radial heat inflow per unit volume, this equation is derived from differential equation of heat conduction in cylindrical coordinates;

The third term represents the energy change per unit volume resulting from vapor migration through the porous medium.

Where ρd,e is the effective density of dried layer, kg/m3; cd is the specific heat of dried layer, J/(kg·K); Td is the temperature of dried layer, K; t is the drying time, s; λd,e is the effective thermal conductivity of dried layer, W/(m·K); r is the radial position, m; cw is the specific heat of vapor, J/(kg·K); Gw is the mass flux rate of vapor, kg/(m2·s); r1 is the external radius of aorta, m; r2 is the internal radius of aorta, m; rs,1 is the radial position of external sublimation front, m; rs,2 is the radial position of internal sublimation front, m.

(2) Energy equation of the frozen layer [22]

where ρf is the density of frozen layer, kg/m3; cf is the specific heat of frozen layer, J/(kg·K); Tf is the temperature of frozen layer, K; λf is the thermal conductivity of frozen layer, W/(m·K).

(3) Energy equation of the sublimation front [7,22]

where us is the velocity of sublimation front, m/s; ΔHs is the enthalpy of sublimation, J/kg; Ts,1 is the temperature of external sublimation front, K; Ts,2 is the temperature of internal sublimation front, K.

The movement directions of the external and internal sublimation interfaces are opposite. Consequently, the energy equations governing these two interfaces differ.

(4) Continuity equation for vapor flow in the dried layer [22]

where M is the molar mass of ice, kg/kmol; ε is the porosity of the dried layer; pw is the pressure of vapor, Pa; Ra is the universal gas constant, J/(kmol·K).

(5) Diffusion equation of vapor in the dried layer

where D is the diffusion coefficient of vapor, m2/s.

(6) Equation of sublimation resistance

where Rs is the sublimation resistance, (Pa·s·m2)/kg.

(7) Motion Equation of sublimation front

(8) Initial conditions

(9) Boundary conditions

where qrad is the heat flux density of aortic wall, W/m2; σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, 5.67 × 10−8; ζ is the emissivity; ξ is angle coefficient of radiation, the value for outer wall of aorta is 1, and the value for inner wall of aorta is 0.3344 [23]; Th is the radiation temperature of shelf, K; Tsur is the Surface temperature of the aortic wall, K.

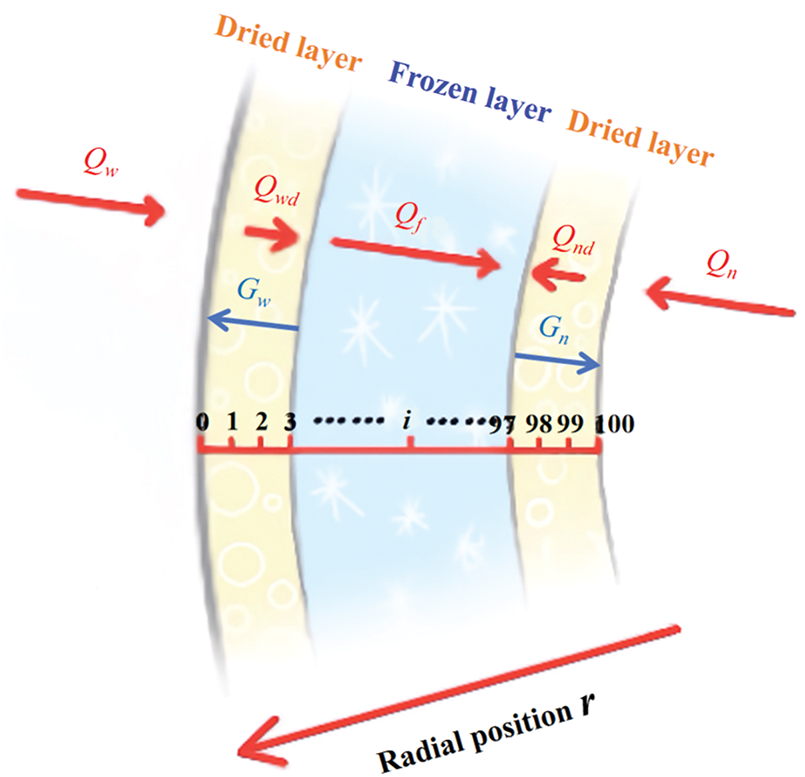

Given the minimal thickness of aortic wall, 100 uniformly spaced nodes were defined along the radial direction, spanning from the outer to the inner wall. The associated heat and mass transfer processes were illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Schematic of heat and mass transfer in the radial direction of aorta

For PDE-based engineering models, the principal computational methods encompass analytical and numerical method, with the finite difference method (FDM) standing out for its algorithmic simplicity and robust numerical precision. Unlike ordinary heat transfer, the moving boundaries has always been a challenge in the study of freeze-drying. To a certain extent, it has restricted the application of the finite difference method. Juckers et al. [24] investigated heat and mass transfer in freeze-drying using a sorption-sublimation model, incorporating two novel coordinates to map the moving boundary onto a fixed domain. This enabled precise tracking of transient transfer dynamics and accurate prediction of key parameters. This suggests a viable approach for discretizing the equation.

Unlike conventional transient heat conduction problems, the continuous movement of the sublimation front necessitates a dynamic treatment of the computational domain. To address this, in this study, a movable node was introduced to explicitly track the position of the sublimation interface, in addition to the fixed spatial and temporal discretizations. This node did not replace fixed node but rather supplements the grid to accommodate domain deformation. Separate energy balance equations were formulated for the sublimation interface and its two adjacent control volumes.

Given that different tunica layers possess distinct physical parameters, and the tunica elastica is not aligned with the fixed nodes, two additional nodes are introduced to represent the positions of inner and outer tunica elastica, respectively. Therefore, the spatial step sizes on both sides of the elastic tunicas differ from those in other regions, and the computational grids must be generated according to their actual dimensions.

Subsequently, the partial differential equations were discretized using the finite difference method. The transient term was approximated by a backward difference scheme, the thermal conduction term by a central difference scheme, and the radial heat flux component in cylindrical coordinates by a backward difference. As the direction of mass transfer is opposite to that of heat transfer, the mass flux term was discretized using a forward difference scheme.

The mass and residual moisture content of the weighted sample from group A varied with drying time, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The total duration of primary drying was 33 h and 15 min. Upon completion of this stage, the mass of the sample reached 0.814 g, corresponding to a cumulative mass loss of 64.08%. The residual moisture content was approximately 10% after primary drying.

Figure 5: Mass and residual moisture content of the weighted sample of group A varied with drying time

Following the initiation of primary drying, ice crystals underwent rapid sublimation, accompanied by a pronounced decrease in sample mass. After 10 h of lyophilization, approximately 50% of the initial ice content had sublimed, increasing to nearly 75% after 15 h. The sublimation rate decreased significantly in the later phase of primary drying. Owing to the substantially reduced sublimation rate toward the end of this stage, the residual moisture content, along with bound water, was removed during secondary drying.

The secondary drying step lasted 6 h and 55 min, resulting in a total lyophilization time over 40 h. Across the nine replicate samples, the average mass loss following lyophilization was 73.52%.

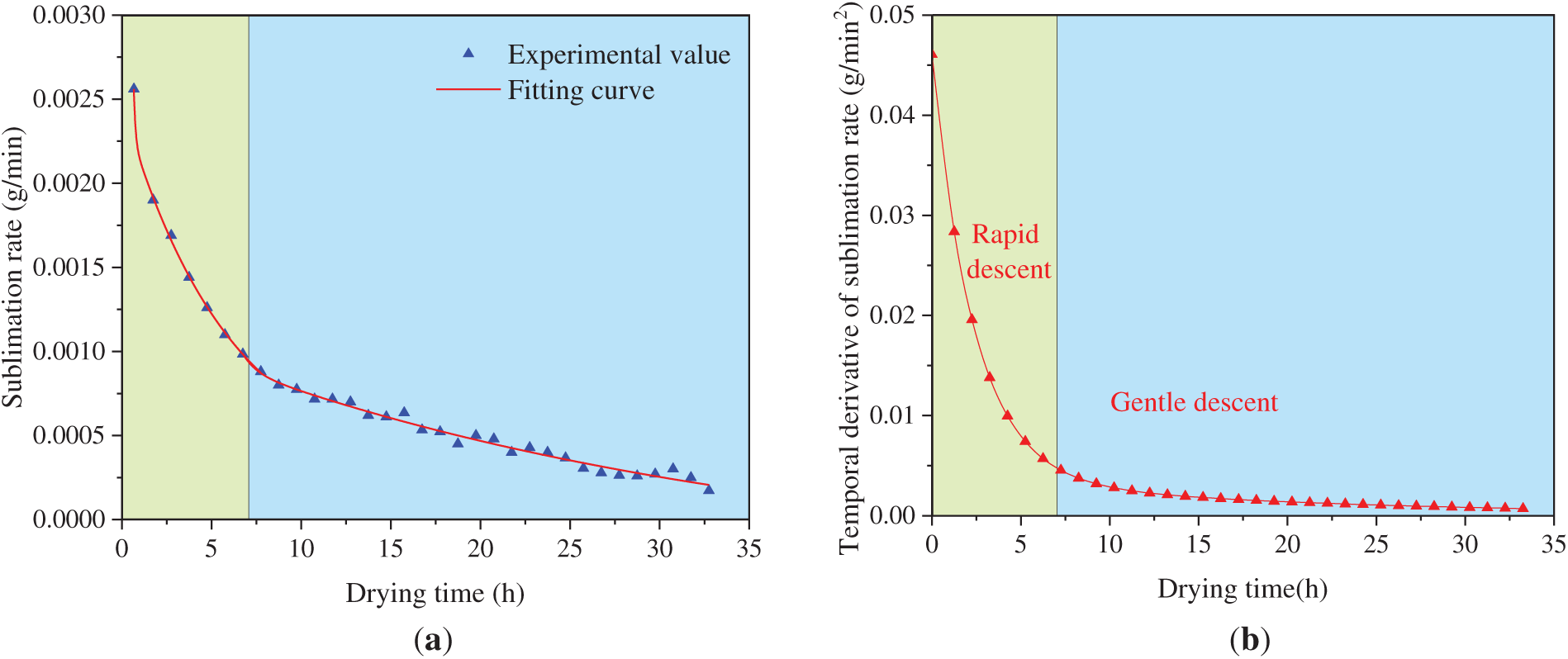

The sublimation rate and its temporal derivative as functions of drying time are shown in Fig. 6. Following the onset of drying, initial sublimation occurred in the ice crystals on the inner and outer surfaces. During the initial stage, the thin dried layer and large temperature gradient resulted in a high but rapidly declining sublimation rate. In the mid-to-late stages, the rate stabilized at a significantly lower level, often falling below 1 mg/min. The main components of the inner and outer membranes of the aorta are connective tissue, which has a high water content. This is the main reason for the relatively large amount of sublimation in the early stage. With increasing dried layer thickness, the thermal gradient decreased and the sublimation rate dropped rapidly. Subsequently, the decline in the sublimation rate moderated significantly and eventually stabilized. This occurred because the lower density of ice crystals (compared to water) leads free water to migrate and aggregate during the pre-freezing process. These observations are consistent with the histological scanning results [13].

Figure 6: Sublimation rate and its temporal derivative of the weighted sample of group A varied with drying time: (a) Sublimation rate; (b) Temporal derivative of sublimation rate

The temporal trend of the sublimation rate closely matched an exponential decay function. After several iterations, fitting the data separately for the pre-7-h and post-7-h drying periods resulted in a comparatively smaller residual error. Furthermore, the change rate in sublimation rate decreased exponentially as a function of dried layer thickness. Following approximately 7 h of drying, the value dropped below 0.005 g/min2, subsequently remaining nearly constant. At this point, the residual water content is approximately 58.92%.

Moisture loss data indicated that the sublimation front reached the tunica media after approximately 7 h of drying. The tight structure of elastic fibers led to low moisture content per unit volume and small pore size, which severely restricted vapor diffusion and transfer. Once the sublimation front reached the tunica media, the diffusion coefficient decreased, the increase in mass transfer resistance slowed, and the decline in sublimation rate diminished significantly.

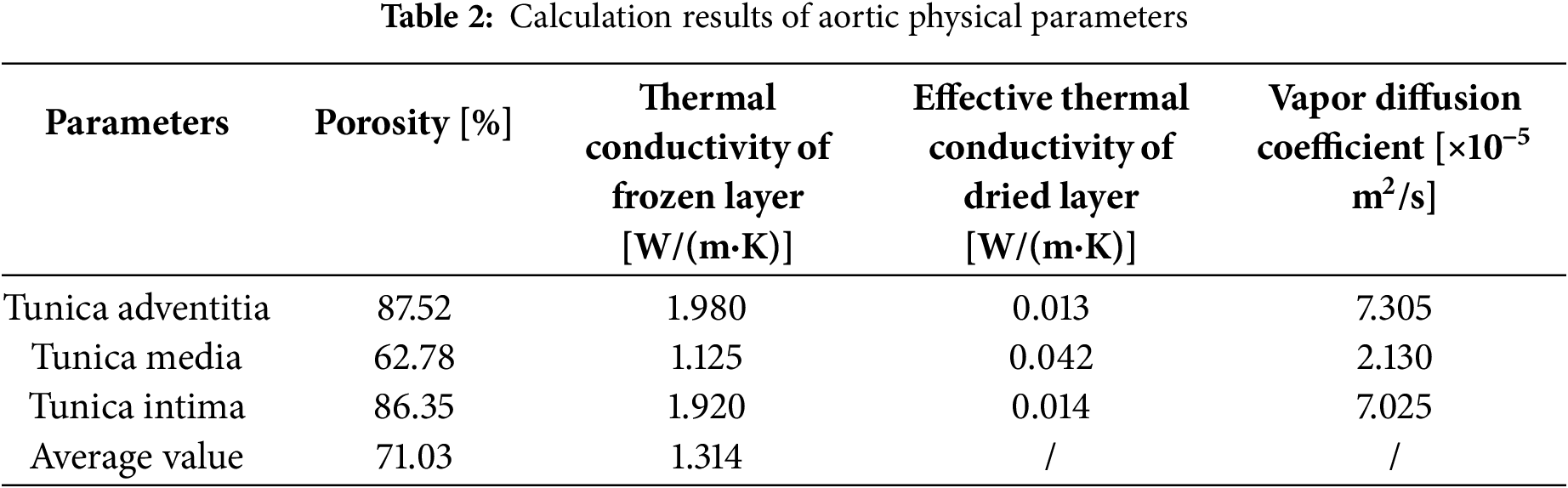

The relevant physical parameters of the freeze-dried aorta were determined from experimental data and mathematical models, as shown in Table 2. Owing to their higher free water content, the tunica adventitia and intima develop a greater porosity than the tunica media following sublimation. The thermal conductivity of the frozen tunica adventitia and intima is relatively high, primarily attributed to the higher thermal conductivity of ice crystals. The vapor diffusion coefficient within the dried layer was derived by combining the heat and mass transfer model with moisture loss data. The diffusion coefficient of the tunica media is constrained by its small pore size. Moreover, the dried layer is characterized by a small average pore size, leading to vapor diffusion that exhibits Knudsen diffusion characteristics.

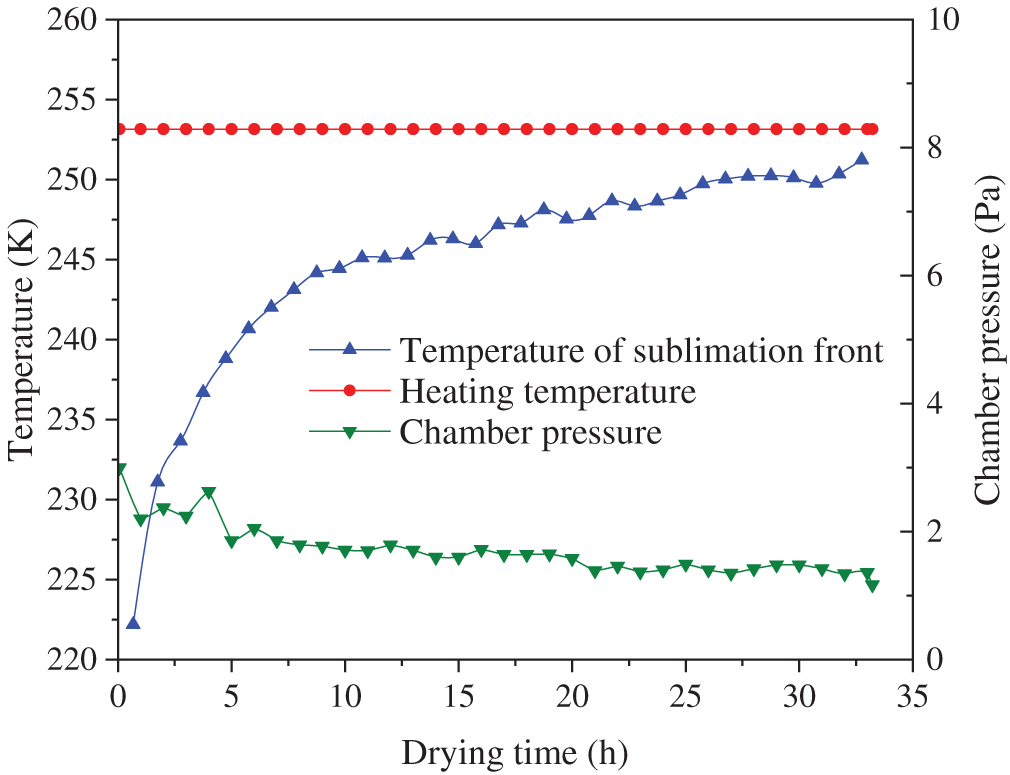

The temporal evolution of chamber pressure and sample temperature is shown in Fig. 7. During the sublimation drying phase, the heating plate temperature remained stable, the chamber pressure was maintained below 2 Pa, and external heat and mass transfer conditions remained consistent. In the initial drying stage, the sublimation temperature remained low while the heating rate was high, primarily due to the high specific heat capacity of ice and the abundance of ice crystals present in both the tunica intima and adventitia. The high moisture content resulted in a relatively large heat capacity. When the sublimation front reached the tunica media, the temperature increase stabilized and exhibited an approximately linear trend, due to the diminished thermal gradient and low volumetric water content.

Figure 7: Chamber pressure and sample temperature of group A varied with time

Since the model calculation results refered to the moiture loss data, the computed sublimation front temperature, similar to the sublimation rate, exhibited minor fluctuations during the middle and late stages of sublimation drying.

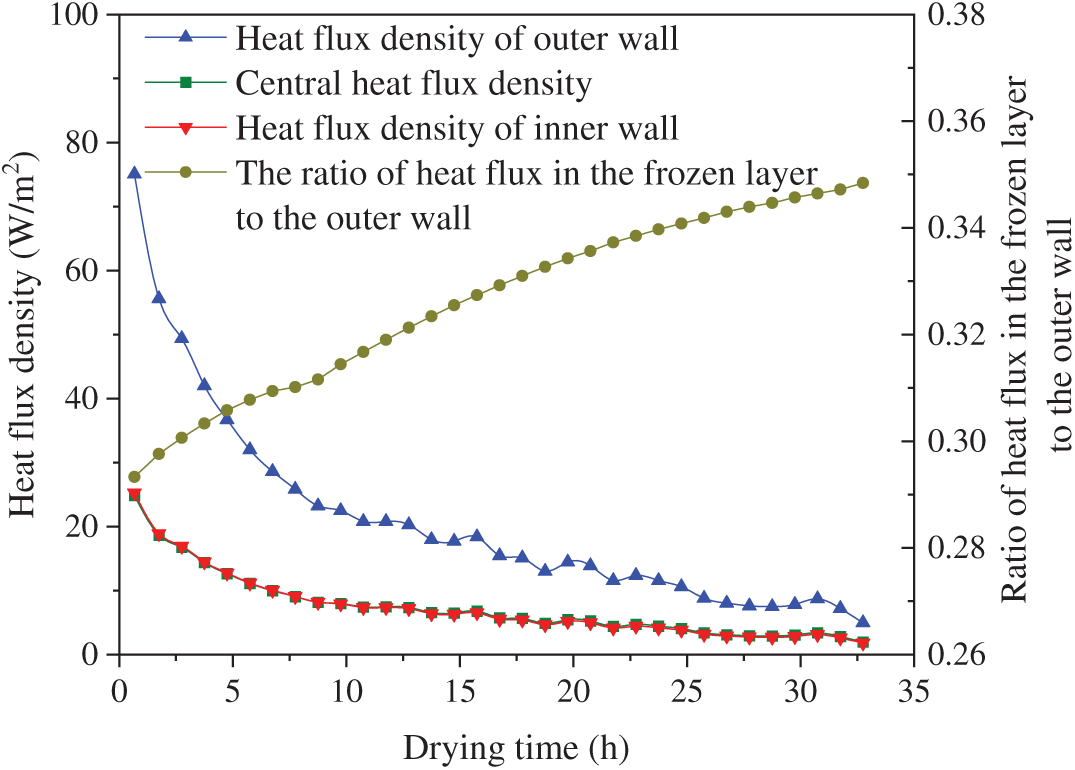

The variation of heat flux density over time is shown in Fig. 8. Driven by the initial temperature gradient, the heat transfer rate was relatively high during the initial drying phase, thereby supplying ample thermal energy for the sublimation of surface ice crystals. As the thickness of the dried layer increases, the heat flux density decreases significantly. The outer wall absorbed more radiant heat compared to the inner wall, resulting in a relatively larger heat flux density. A temperature gradient across the frozen layer facilitated the transfer of a portion of the external heat flux toward the inner region. The sublimation heat flux density was initially high, reaching up to 50 W/m2. However, during the mid-to-late stages, it remained below 10 W/m2 for extended periods, substantially limiting the overall sublimation rate.

Figure 8: Heat flux density of group A samples varied with drying time

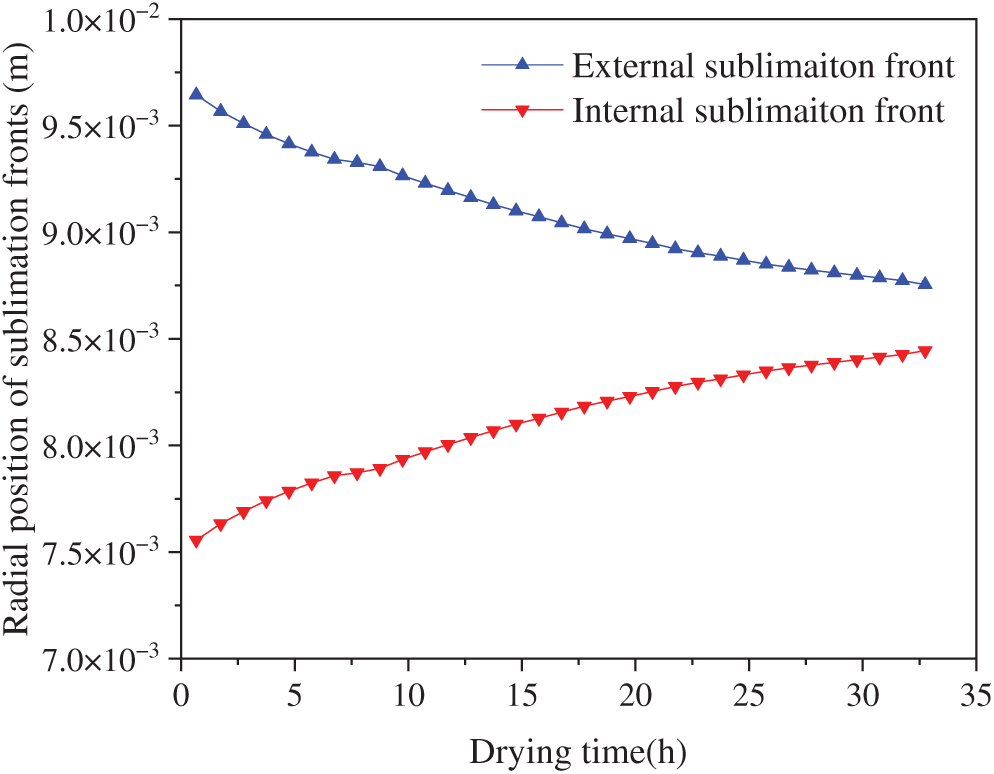

The radial position of sublimation fronts as a function of drying time is shown in Fig. 9. Following the onset of drying, the internal and external sublimation fronts advanced inward simultaneously toward the central region. Although the sublimation rate gradually decreased over the drying duration, the migration rate of the sublimation front remained largely consistent throughout the entire process—a phenomenon primarily attributable to the annular architecture of the aortic wall. Taking external sublimation as an example: as the sublimation front advanced, its radial position shifted inward, accompanied by a substantial reduction in the mass of ice crystals being sublimated.

Figure 9: Radial position of sublimation fronts in group A samples varied with drying time

The internal and external sublimation fronts maintained approximately equal movement rates. This was primarily because, within the radiative heat absorbed by tunica adventitia, the fraction of heat flux conducted through the frozen layer to the internal sublimation front progressively increased, as illustrated in Fig. 8.

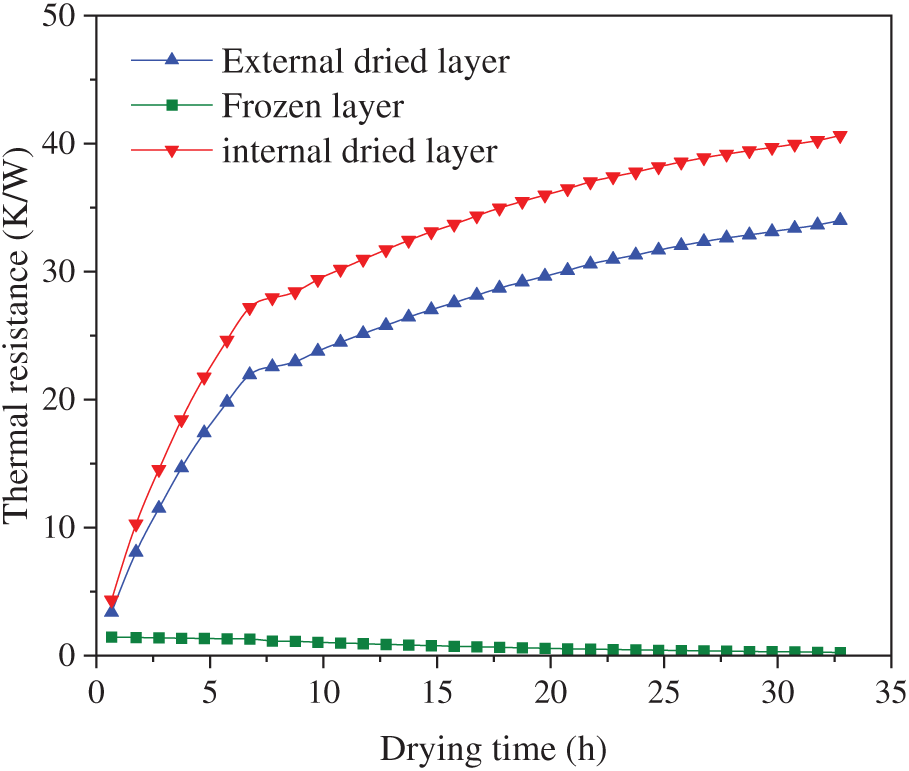

The variation of heat transfer resistance with drying time is shown in Fig. 10. The thermal resistance of the frozen layer remained relatively low, owing to its high thermal conductivity. As the dried layer thickened, the thermal resistance of the frozen layer decreased gradually, albeit to a very limited extent. The initial thermal resistance values did not exceed 1.5 K/W. Furthermore, the thermal resistance of both the inner and outer dried layers exhibited a similar variation pattern, showing an approximately linear increase throughout the process. During the initial drying stage, the dried layer exhibited a substantial increase in thermal resistance. However, once the sublimation front reached the middle layer, this rate of increase diminished significantly. The thermal resistance of the inner dried layer exceeded that of the outer dried layer, a characteristic primarily attributable to the annular geometry of the material, where thermal resistance increased at smaller radial positions.

Figure 10: Heat transfer resistance of group A samples varied with drying time

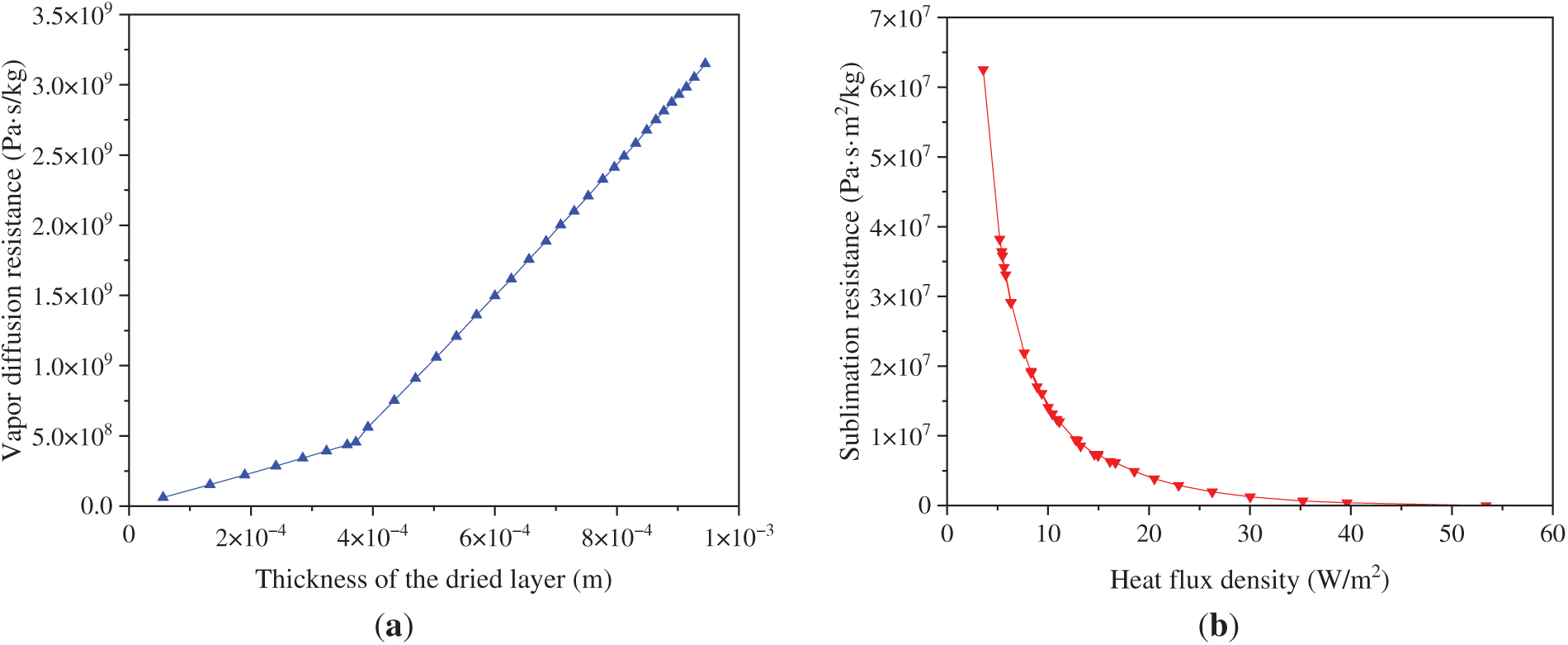

The variation of mass transfer resistance with drying time is shown in Fig. 11. The resistance to vapor diffusion increased linearly with dried layer thickness. Because of the inherently low diffusion coefficient of the tunica media, the diffusion resistance increased significantly once the sublimation front advanced into this layer. The rate of sublimation mass transfer was governed mainly by heat transfer. The sublimation resistance exhibited an exponential increase as the heat flux density decreased. During the later stage of sublimation drying, the temperature difference driving heat transfer was limited to less than 0.001 K. Consequently, the heat flux density dropped below 3 W/m2, and the sublimation mass transfer resistance increased to 6.3 × 107 (Pa·s·m2)/g. This phenomenon accounts for the significant decline in the sublimation rate observed in the later drying phase.

Figure 11: Mass transfer resistance of group A samples varied with drying time: (a) vapor diffusion resistance; (b) sublimation resistance

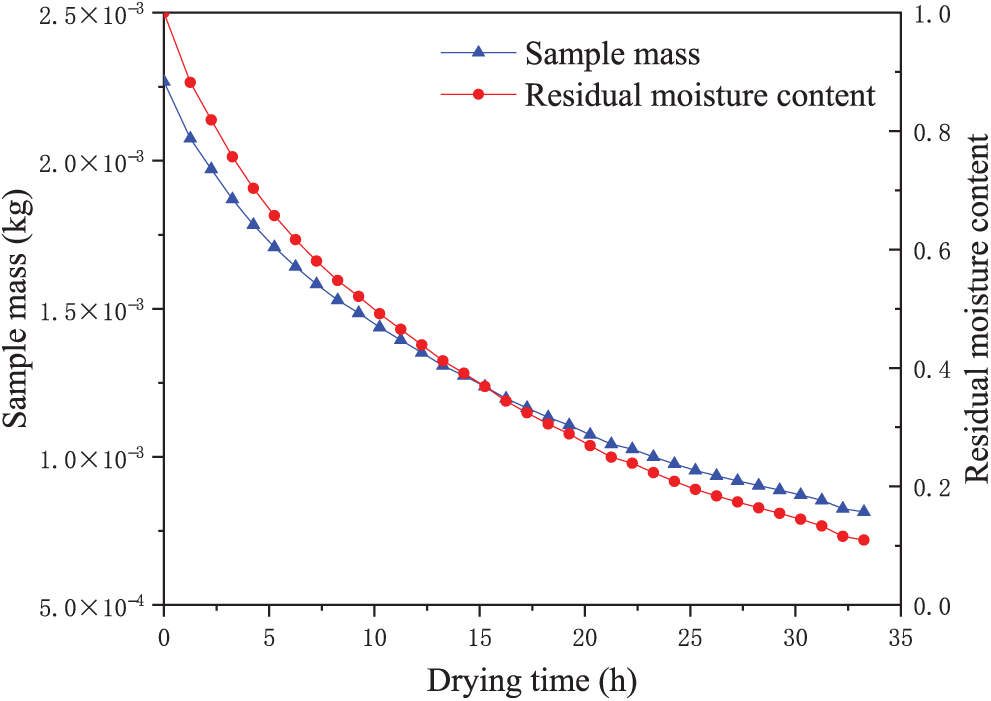

The parameters of the second set of freeze-dried samples were implemented in the numerical model for simulation. Modeled residual water content agreed well with the experimental data, as shown in Fig. 12. A discrepancy emerged in the later drying phase, the model predictions exhibited a more rapid decline than the experimental measurements primarily attributable to variations in the experimental environment. In actual freeze-drying operations, heat transfer to the samples occured not only through radiation from the shelves but also from the inner surfaces of the chamber and acrylic door. Furthermore, these radiative heat contributions were more difficult to predict, introducing a degree of variability into the thermal environment of the process. This is the primary cause of the slight batch-to-batch variations in residual moisture content observed in the freeze-drying experiments.

Figure 12: Residual moisture content of group B samples varied with drying time

This study established a heat and mass transfer model that accounts for the radially layered structure of porcine aorta and validated it experimentally using a novel non-contact dehydration monitoring system. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The freeze-drying process transitioned from high initial sublimation rates to a mass transfer-limited regime in later stages. A key transition occurred as the sublimation front reached the tunica media after approximately 7 h, significantly altering drying kinetics due to the structural properties of this layer.

(2) Integration of dehydration data with the numerical model enabled accurate determination of critical physical parameters—such as effective thermal conductivity, vapor diffusivity, and mass transfer resistance—essential for characterizing the lyophilized tissue.

(3) The model incorporated a dynamic node strategy to track the moving sublimation interface, effectively addressing computational challenges posed by domain deformation. Additionally, specialized fixed nodes targeting the elastic tunica were incorporated to adapt to the multilayer structure and its spatially varying thermophysical properties. This approach improved model accuracy, thereby enhancing the prediction of freeze-drying behavior and quantification of material properties.

(4) Analysis of heat and mass transfer revealed a substantial decrease in heat flux density with increasing dried layer thickness, accompanied by a linear rise in mass transfer resistance. In the final stage, sublimation resistance increased exponentially under reduced thermal driving force, becoming the dominant limiting factor for sublimation rate.

The methodology developed in this study provides a generalized modeling framework suitable for multilayered biological systems. The dynamic node strategy offers an efficient and transferable solution for simulating phase-change processes in materials with structural heterogeneity and moving boundaries.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely acknowledge the Shanghai Key Laboratory of Multiphase Flow and Heat Transfer in Power and Engineering for their equipment support.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Scientific and Technological Research Projects in Henan Province (No. 252102310425), the Key Scientific Research Projects of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province (No. 23A560018).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Chao Gui and Wanying Chang; methodology, Chao Gui and Leren Tao; formal analysis, Yaping Liu and Mengyi Ge; investigation, Chao Gui and Daoming Shen; resources, Leren Tao and Yaping Liu; data collection, Wanying Chang; writing—original draft preparation, Chao Gui; writing—review and editing, Chao Gui, Wanying Chang and Yaping Liu; supervision, Leren Tao; project administration, Yaping Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| c | Specific heat of dried layer, [J/(kg·K)] |

| D | Diffusion coefficient of vapor, [m2/s] |

| G | Mass flux rate, [kg/(m2·s)] |

| M | Molar mass of ice, [kg/kmol] |

| p | Pressure, [Pa] |

| q | Heat flux density, [W/m2] |

| Ra | Universal gas constant, [J/(kmol·K)] |

| Rs | Sublimation resistance, [(Pa·s·m2)/kg] |

| r | Radial position, [m] |

| T | Temperature, [K] |

| t | Drying time, [s] |

| u | Velocity, [m/s] |

| ΔHs | Enthalpy of sublimation, [J/kg] |

| Greek Symbols | |

| β | Empirical weighting factor |

| ε | Porosity of the dried layer |

| ζ | Emissivity |

| λ | Thermal conductivity, [W/(m·K)] |

| ξ | Angle coefficient of radiation |

| ρ | Density, [kg/m3] |

| φ | Volume fraction of ice phase |

| Greek Symbols | |

| 0 | Initial value |

| 1 | Outer wall |

| 2 | Inner wall |

| ave | Average |

| d | Dried layer |

| e | Effective value |

| f | Frozen layer |

| h | Heating |

| ice | Ice crystal |

| par | Parallel |

| rad | Radiation |

| s | Sublimation front |

| ser | Series |

| sol | Solid matrix |

| sur | Surface aortic wall |

| w | Vapor |

References

1. Sheridan WS, Duffy GP, Murphy BP. Mechanical characterization of a customized decellularized scaffold for vascular tissue engineering. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2012;8(2):58–70. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Giovanniello F, Asgari M, Breslavsky ID, Franchini G, Holzapfel GA, Tabrizian M, et al. Development and mechanical characterization of decellularized scaffolds for an active aortic graft. Acta Biomater. 2023;160:59–72. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2023.02.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Sheridan WS, Duffy GP, Murphy BP. Optimum parameters for freeze-drying decellularized arterial scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2013;19(12):981–90. doi:10.1089/ten.TEC.2012.0741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Jia Z, Zhou J, Wang W, Liu D, Zheng X, Hu M, et al. Optimization of vacuum freeze-drying process and quality evaluation of Stropharia rugosoannulata. Appl Sci. 2024;14(22):10158. doi:10.3390/app142210158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yan WM, Chen CY, Chen BL, Amani M, Chien LH, Li WK. Optimization of microwave vacuum drying of pineapples: a three-stage approach. Results Eng. 2025;25:104228. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abla KK, Mehanna MM. Freeze-drying: a flourishing strategy to fabricate stable pharmaceutical and biological products. Int J Pharm. 2022;628:122233. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.122233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Aydin ES, Yucel O, Sadikoglu H. Modelling and simulation of a moving interface problem: freeze drying of black tea extract. Heat Mass Transf. 2017;53(6):2143–54. doi:10.1007/s00231-017-1974-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chaurasiya V, Singh J. An analytical study of coupled heat and mass transfer freeze-drying with convection in a porous half body: a moving boundary problem. J Energy Storage. 2022;55:105394. doi:10.1016/j.est.2022.105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pisano R, Barresi AA, Capozzi LC, Novajra G, Oddone I, Vitale-Brovarone C. Characterization of the mass transfer of lyophilized products based on X-ray micro-computed tomography images. Dry Technol. 2017;35(8):933–8. doi:10.1080/07373937.2016.1222540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Andrieu J, Vessot S. A review on experimental determination and optimization of physical quality factors during pharmaceuticals freeze-drying cycles. Dry Technol. 2018;36(2):129–45. doi:10.1080/07373937.2017.1340895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Capozzi LC, Barresi AA, Pisano R. A multi-scale computational framework for modeling the freeze-drying of microparticles in packed-beds. Powder Technol. 2019;343:834–46. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2018.11.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Carfagna M, Rosa M, Hawe A, Frieß W. Design of freeze-drying cycles: the determination of heat transfer coefficient by using heat flux sensor and MicroFD. Int J Pharm. 2022;621:121763. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2022.121763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Yu T, Marx R, Hinds M, Schott N, Gong E, Yoon S, et al. Development of a single vial mass flow rate monitor to assess pharmaceutical freeze drying heterogeneity. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2024;25(8):245. doi:10.1208/s12249-024-02961-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang M, Liu H, Cai Z, Sun C, Sun W. An improved analytical method to estimate three-dimensional residual stresses of the aorta. Appl Math Model. 2021;90:351–65. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2020.08.063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gui C, Tao L, Zhang Y. Experimental study on improvement of freeze-drying process for porcine aorta. Dry Technol. 2022;40(2):401–15. doi:10.1080/07373937.2020.1802744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wu JQ, Tao LR, Liu MF, Yin M. Micro-CT experimental study concerning movement characteristics of sublimation interface in freeze-drying preservation of the artery. J Clin Rehabil Tissue Eng Res. 2010;14(7):1196–9. (in Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-8225.2010.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yin M. Effect of pre-freezing rate on porosity ratio and mechanical property of pig aorta. Front Biosci. 2012;17(1):575. doi:10.2741/3945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Huang GG, Zhou GY, Li CX, Hua ZZ. Study on thermal conductivity probe for thermal conductivity of artery at low temperature. Gryogenics. 2005;5:49–52. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

19. Renaud T, Briery P, Andrieu J, Laurent M. Thermal properties of model foods in the frozen state. J Food Eng. 1992;15(2):83–97. doi:10.1016/0260-8774(92)90027-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Fu WQ, Gao H, Xue ZX, Guan WJ, Han F, Wang XD. Experimental measurement and calculation of thermal conductivity of porous material. China Meas Test Technol. 2016;42(5):124–30. (In Chinese). doi:10.11857/j.issn.1674-5124.2016.05.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Carson JK, Lovatt SJ, Tanner DJ, Cleland AC. Thermal conductivity bounds for isotropic, porous materials. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2005;48(11):2150–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2004.12.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sheehan P, Liapis AI. Modeling of the primary and secondary drying stages of the freeze drying of pharmaceutical products in vials: numerical results obtained from the solution of a dynamic and spatially multi-dimensional lyophilization model for different operational policies. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;60(6):712–28. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19981220)60:6<712::aid-bit8>3.0.co;2-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gui C, Tao L, Yang W, Zhang Y, Chen S, Shen D, et al. Numerical simulation of heat and mass transfer during sublimation drying of porcine aorta. Dry Technol. 2022;40(11):2260–73. doi:10.1080/07373937.2021.1930038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Juckers A, Potschka A, Strube J. Advanced freeze-drying modeling: validation of a sorption-sublimation model. ACS Omega. 2025;10(16):16962–76. doi:10.1021/acsomega.5c01665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools