Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Surface Wettability and Boiling Heat Transfer Enhancement in Microchannels Using Graphene Nanoplatelet and Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube Coatings

1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Skudai Campus, Johor, 81310, Malaysia

2 Kunskapscompaniet, Eskilstuna, 63356, Sweden

* Corresponding Author: Natrah Kamaruzaman. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Microscale Heat and Mass Transfer and Efficient Energy Conversion)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(6), 1933-1956. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.070118

Received 08 July 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

The pivotal role microchannels play in the thermal management of electronic components has, in recent decades, prompted extensive research into methods for enhancing their heat transfer performance. Among these methods, surface wettability modification was found to be highly effective owing to its significant influence on boiling dynamics and heat transfer mechanisms. In this study, we modified surface wettability using a nanocomposite coating composed of graphene nano plate (GNPs) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) and then examined how the modification affected the transfer of boiling heat in microchannels. The resultant heat transfer coefficients for hydrophilic and hydrophilic composite (GNPs+MWCNT) microchannels were, respectively, 42.8% and 33.95% higher compared with that of the uncoated surface. These results verify that hydrophilic GNP-based coating significantly improves boiling heat transfer performance. It was observed that a minor increase in contact angle,Keywords

Nomenclature

| A | Area, m2 |

| Cp | Specific heat at constant pressure, J/kg K |

| D | Diameter, m |

| f | Fanning friction factor |

| g | Gravitational acceleration, m/s2 |

| G | Mass flux, kg/m2 s |

| h | Heat transfer coefficient, W/m2 K |

| H | Depth, m |

| i | Enthalpy, J/kg |

| I | Current, A |

| k | Thermal conductivity, W/m K |

| L | Length, m |

| m | Mass flow rate, kg/s |

| P | Power, Watt |

| P | Pressure, Pa |

| q″ | Heat flux, W/m2 |

| Q | Heat, W |

| th | Distance between thermocouple location |

| T | Temperature, °C |

| V | Voltage, V |

| v | Velocity, m/s |

| W | Width, m |

| Z | Distance measured from inlet channel m |

| Re | Reynolds number |

| kl | Thermal conductivity of the liquid, W/m·K |

| Greek Symbols | |

| σ | Surface tension (N/m) |

| ρ | Density kg/m3 |

| β | Aspect ratio |

| Δ | Difference, Drop (K, Pa) |

| μ | Viscosity kg/m s |

| Subscripts | |

| a | Ambient |

| app | Apparent |

| Avg. | Average |

| b | Base |

| ch | Channel |

| cu | Copper |

| f | Fluid |

| FD | Fully developed flow |

| e | Exit |

| g | Gas, vapour |

| h | Hydraulic |

| hfg | Latent heat of vaporization (J/kg) |

| ρg | Density of the vapor (gas) phase (kg/m3) |

| i | Inlet |

| l | Liquid |

| lg | Vaporization |

| m | Measured |

| o | Outlet |

| sat | Saturation |

| sp | Single-phase |

| sc | Sudden contraction |

| se | Sudden expansion |

The increasing power density of microelectronic devices and the widespread use of compact refrigeration systems highlight the need for reliable thermal management solutions that dissipate high heat flux while ensuring consistently high-quality device performance (refer to Fig. 1). A popular approach to dealing with this challenge is the use of flow boiling phase-change in microscale heat exchangers comprising one or more microchannels. In comparison with single-phase liquid cooling, flow boiling has shown higher effectiveness in heat transfer. The reason is that by using the latter, more thermal energy can be extracted through the latent heat of vaporization instead of depending only on sensible heat, as in single-phase systems [1,2].

Figure 1: Flow diagram of a cooling system problem statement [35]

Flow boiling offers numerous advantages and was found to be more effective in dissipating the heat, though two-phase flow in microchannels often encounters an early onset of critical heat flux (CHF) [3–5]. CHF occurs when a vapor blanket forms because of bubble coalescence, insulating the heated surface. This abruptly raises the surface temperature and sharply reduces the heat transfer coefficient (HTC). To avoid overheating and probable system failure in practical applications, they must operate below their CHF limits.

A commonly used approach to reducing flow instability is modifying the geometry of the heated surface, especially with complex designs [6–8]. However, creating intricate geometries often demands advanced, costly fabrication equipment. One of the most explored geometric modifications involves using an inlet restrictor, which aids in counteracting the significant evaporative momentum force through flow inertia. This also introduces an unwanted increase in pressure drop. Structured surfaces, despite their susceptibility to fouling, mechanical failure, and clogging, hold promise for improving the performance of two-phase heat transfer. In addition, the techniques of surface modification [9,10] have been used in the literature at two levels of micro-scale and nano-scale for the enhancement of capillary wicking [11] and the stabilization of the contact line through pinning [12]. This facilitates an earlier transition to annular flow. The problem is that these coatings tend to degrade after multiple uses, diminishing their effectiveness.

A substrate’s surface properties, such as adhesion, corrosion resistance, and wettability, can be improved using coatings. Due to environmental and economic challenges, coating industry professionals are developing new technologies and materials for more efficient coatings. The effectiveness of a coating against possible damage depends on a number of factors, including the environment’s corrosiveness, the coating quality, the substrate physical features, and the properties of the coating/substrate interface [13]. Since nanocomposites generally offer superior properties at relatively low cost, they have increasingly been investigated and applied in coating processes to meet the existing demands of industry. Also, the processing of nanocomposite coatings is comparatively straightforward compared to that of multilayer coatings [14,15].

In addition to these advantages, recent advancements in nanotechnology highlight the potential of surface modifications and nanocoatings not only for improving mechanical and chemical durability but also for enhancing thermal performance through tailored surface architectures. These advances have significantly expanded the potential for enhancing heat transfer through surface modifications [16,17]. Surface morphology can be altered either by mechanical roughening techniques—such as sand or abrasive blasting, shot peening, and chemical etching—without altering the surface’s chemical composition, or by applying nanocoating composed of various materials (such as metals, polymers, ceramics, and composites). These nanocoatings are often engineered into complex micro- and nanoscale architectures such as porous structures, pyramidal shapes, bumps, and pillars, employing advanced deposition techniques including self-assembled monolayers (SAM), chemical vapor deposition (CVD), ion implantation, electrodeposition, and electroless plating, among others [18,19].

A wide variety of applications, including biological engineering [20,21], filtration [22,23], material strengthening [24–26], and heat transmission [26–29], have increasingly utilized graphene. Recent researches have shown that the wettability of surfaces functionalized with graphene may be adjusted when subjected to light irradiation, pH changes [30], electro-wetting [31], and high-temperature treatments [32,33].

For the initiation of bubble nucleation at reduced surface temperatures, surfaces need to be designed to retain vapor embryos and air pockets. These structures help prevent surface dry out by continuously supplying liquid to the boiling surface at higher heat fluxes. Those nanostructures that have micro-scale flaws are particularly effective, as they hold air pockets for highly wetting fluids under reduced heat fluxes. For super hydrophilic surfaces, carbon-based nanostructures are considered ideal because of their ability to support early bubble nucleation and maintain thermal efficiency without compromising heat transfer capabilities.

Researchers [34] have examined the relationship between boiling heat transfer and permeability, porosity, the capillary impact, and thermal effusivity/conductivity. They proposed a covalently linked hybrid structure containing graphene and carbon nanotubes (CNT) to improve the heat transfer capabilities using computer simulations. This structure was found to reduce total thermal resistance while outperforming the heat conduction of few-layer graphene and CNT coatings. They proposed using a graphene-based intermediate layer to grow CNT on a copper substrate, improving CNT adhesion and thermal performance due to graphene’s high thermal conductivity and increased surface contact area. This combination of superhydrophobic graphene and CNT promotes higher latent heat absorption because of film wise evaporation at the graphene-CNT interface. The present paper used a superhydrophobic surface coated by graphene and CNT and could realize a passive Cassie-to-Wenzel transition, resulting in effective flow boiling without any requirement for liquid infiltration or active degassing.

This study accomplished flow boiling heat transfer of a high efficiency by using the coupled effects of a high nucleation rate with lower bubble departure resistance and film wise evaporation. This was aided by a high ratio of surface/volume of the water thin film on the GNP-CNT-coated surface. The findings of this paper provide new insights into the ways hydrophobic graphene and hydrophilic CNT coatings could be used to boost flow boiling heat transfer within a microchannel.

2.1 Sample Preparation (Electroplating Process)

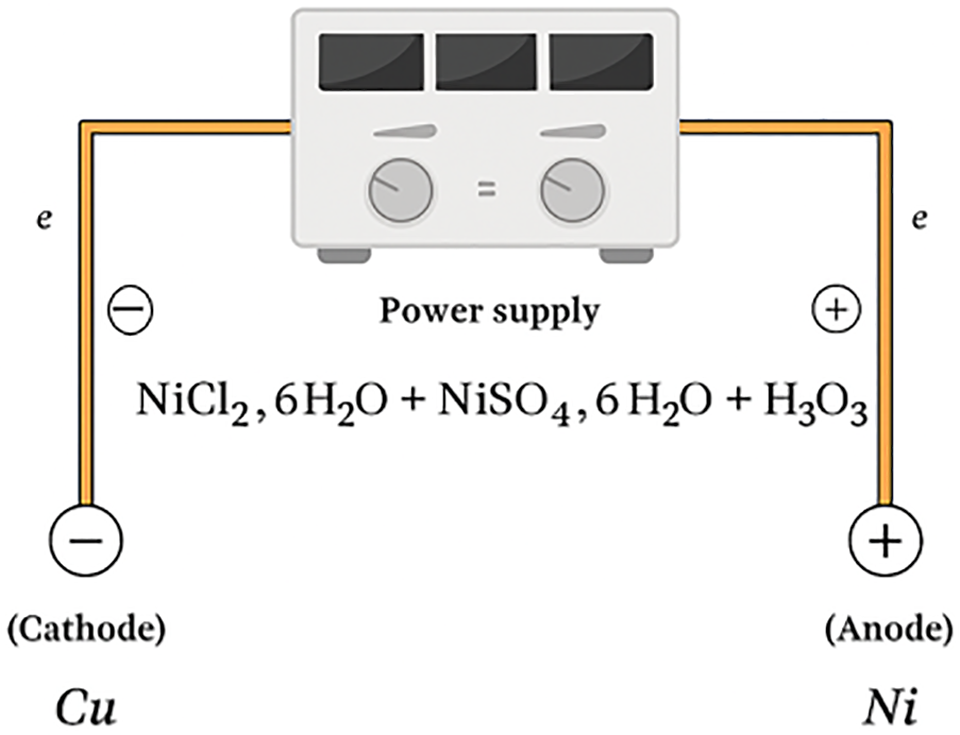

Electrochemical deposition is a well-established electroanalytical technique that involves the selective deposition of metal ions onto an electrode surface under controlled potential conditions. The electrode potential is adjusted to facilitate the desired plating reaction while preventing interference from competing reactions that could lead to the deposition of other insoluble substances [36]. In this study, the electroplating technique was employed to develop a uniform, tenacious, and thick coating on the surface of metallic (primarily copper) specimens. This process was conducted through electrodeposition, by passing an electric current through an electrolyte solution to deposit a metal layer onto a conductive substrate. The electrodeposition system consisted of several essential components: (i) an electrolyte solution (electroplating bath), which serves as the medium for ion exchange; (ii) a cathode, represented by the copper specimens and models of plane and microchannel surfaces to be coated; (iii) a soluble nickel anode; (iv) a magnetic stirrer to ensure the homogeneous dispersion of nanoparticles in the electrolyte; (v) a vessel to contain the electrolyte and other components; and (vi) a direct current (DC) power source to facilitate the electrochemical reaction, as illustrate in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the electroplating process

The electrodeposition technique adopted in this study followed a four-step process [37]. In Step 1, a current density of 109 mA/cm2 was applied, corresponding to a current of 343 mA and a voltage of 3.6 V, for a duration of 30 s. In step 2, the current density was reduced to 36 mA/cm2 (115 mA, 1.7 V) and maintained at that condition for 1200 s. In steps 3 and 4, the two previous steps were repeated, in sequence.

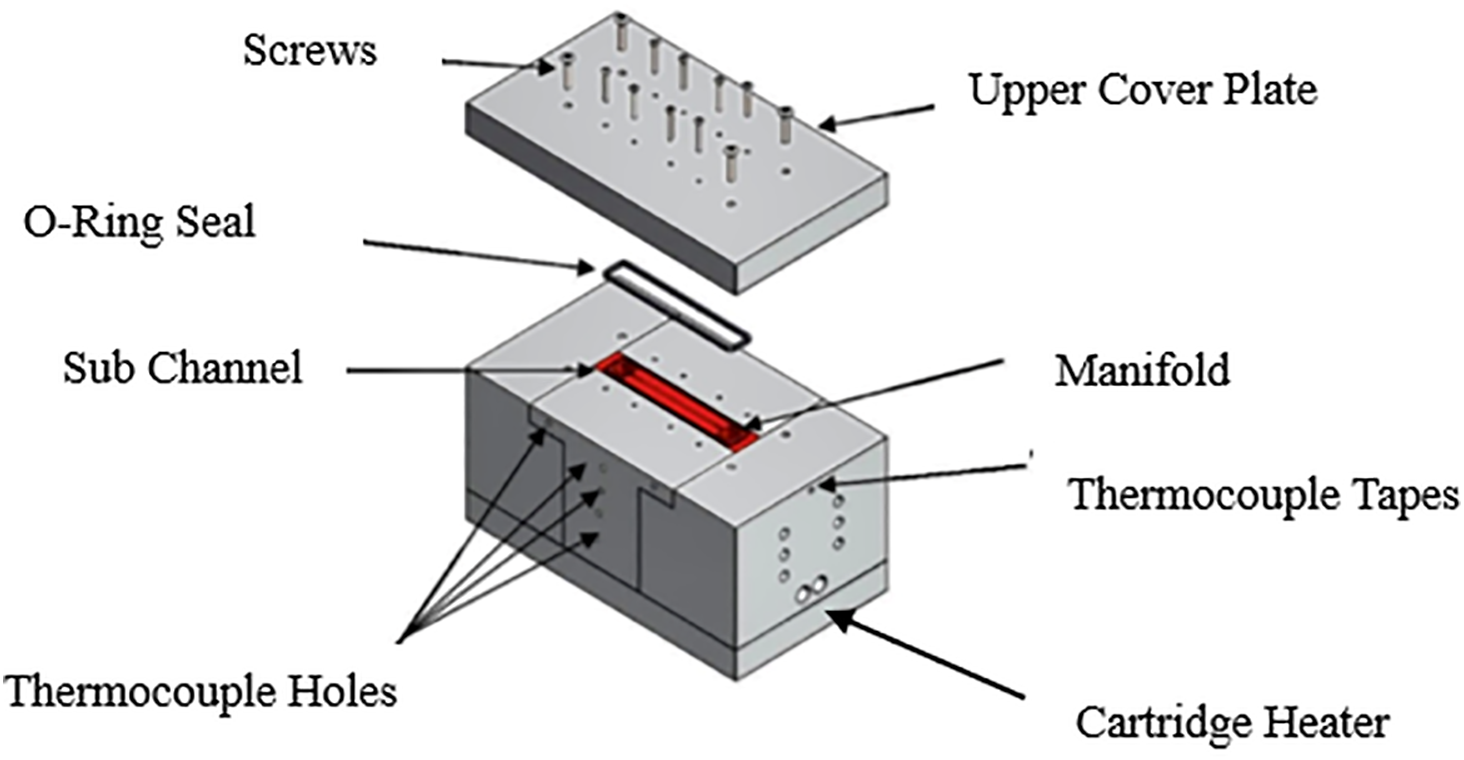

As Table 1 demonstrates, the electrolyte solution for this study was prepared with a total volume of 250 mL. More specifically, it comprised 30 g/L of nickel chloride (NiCl2·6H2O), 240 g/L of nickel sulfate (NiSO4·6H2O), and 37.5 g/L of boric acid (H3BO3). The boric acid caused the solution’s pH to be maintained at 4, ensuring optimal deposition conditions. Prior to the coating process, the nanoparticle additives were introduced into the electrolyte solution and dispersed under magnetic stirring at 400 rpm for 60 min to achieve uniform distribution.

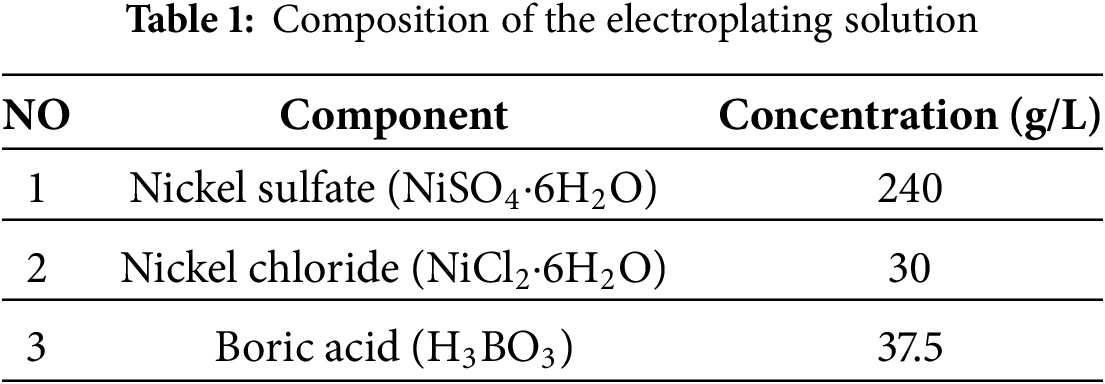

Surface preparation was a critical step to ensure proper adhesion of the coating. Before electrodeposition, all copper substrates in Table 2 underwent a polishing and cleaning process using a mixture of ethanol and hydrochloric acid (HCl·5H2O) in a 1:1 ratio. Subsequently, any residual contaminants were removed from the specimens using distilled water. During the electroplating process, the nickel substrate functioned as the anode, while the copper substrates served as the cathode. A specially designed fixture was used to fix the distance of the two electrodes at 20 mm.

This methodology ensured the deposition of high-quality coatings with enhanced mechanical and structural properties, particularly through incorporating nanocomposites and nanoparticles into the nickel matrix. The detailed characterization of the coatings and their performance evaluation are discussed in subsequent sections of this study.

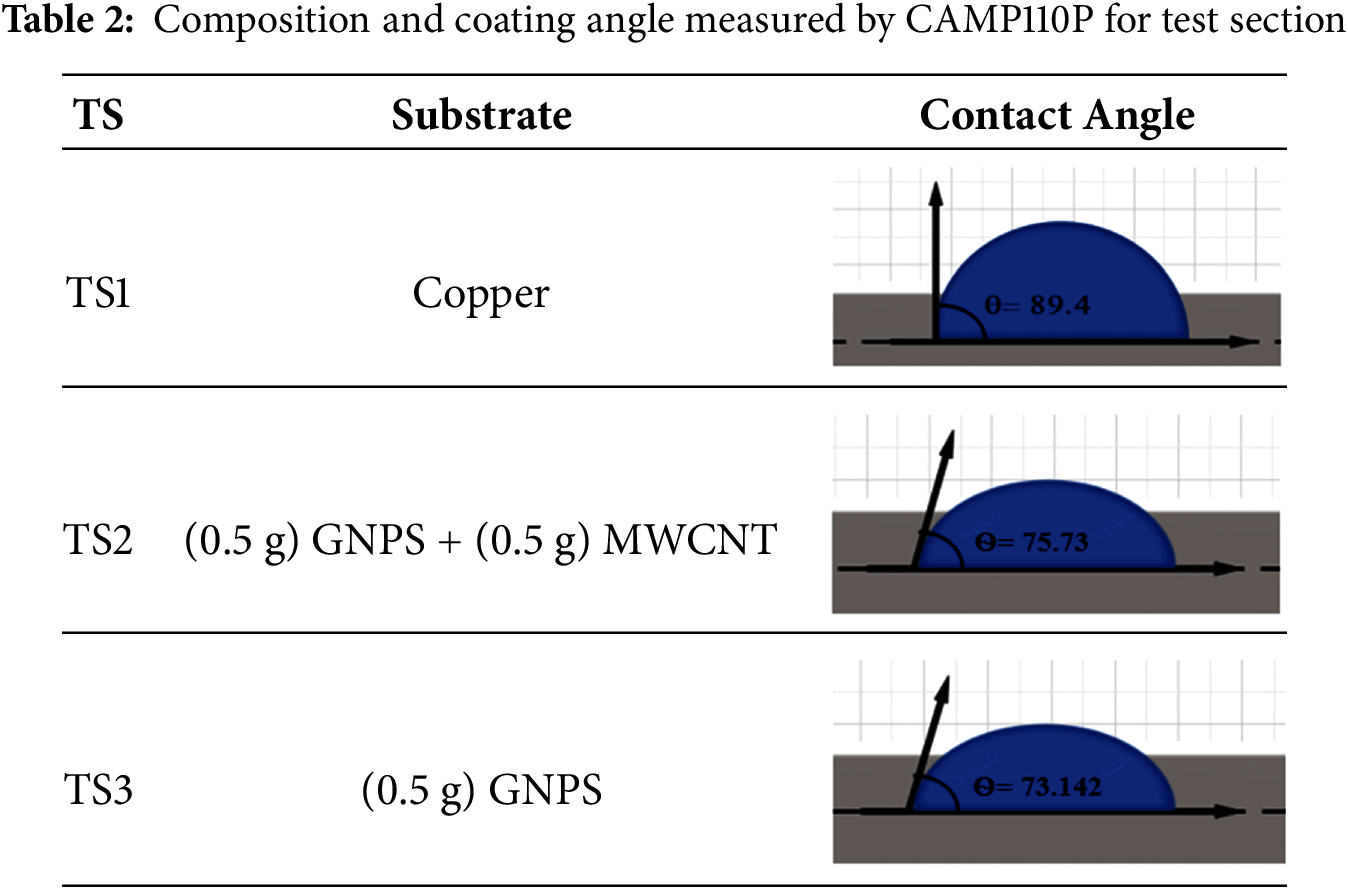

The test section comprises four parts, i.e., the bottom plate, the housing, the cover plate, and the heat sink block see Fig. 3. For the accommodation of the thermocouple wires, thirteen 0.7 mm-diameter holes were drilled into the housing. This study used oxygen-free copper (OFHC) to build the heat sink block, with a length of 114 mm, a width of 20 mm, and a height of 81 mm. The heat sink block was embedded with two cartridge heaters that had a heating capacity of 100 W; the heaters were positioned in their places horizontally, from the bottom side.

Figure 3: Microchannel block geometry

Four type-K thermocouples were placed vertically at equal intervals of 14 mm along the centerline of the copper block. In addition, seven thermocouples were positioned at a depth of 1 mm from the lower surface of the microchannel. All thermocouples used had a diameter of 0.5 mm and a calibration error of ±0.42 K. Furthermore, for the measurement of both the outlet and inlet temperatures of the working fluid, two type-K thermocouples were submerged in the manifolds.

MPX5500DP pressure transducers (with the accuracy of ±0.96%) were used in this study to measure the inlet pressure at the manifolds. In the meantime, an MPX5100DP differential pressure transducer (with the accuracy of ±0.94%) was used to measure the pressure drop across the test section. In addition, to avoid fluid leakage, the top of the housing was covered using a cover plate by inserting an O-ring between the heat sink and the plate.

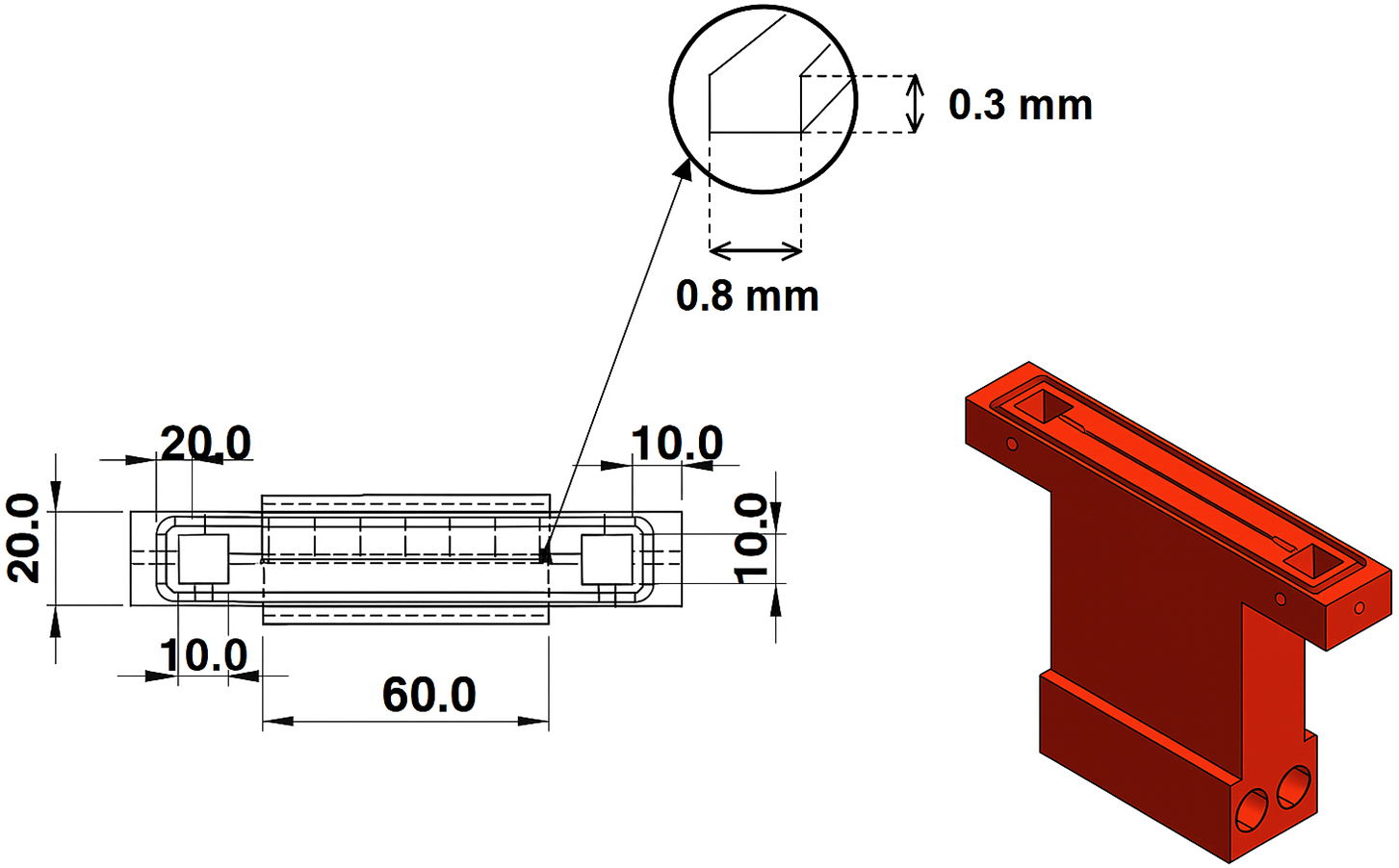

The microchannel geometry used in this study, as shown in Fig. 4, had a width of 0.8 mm, a height of 0.3 mm, and a length of 60 mm. Based on these dimensions, the calculated hydraulic diameter of the channel was 0.48 mm. These details ensure a clear description of the flow passage and allow proper characterization of the Reynolds number range in the experiments.

Figure 4: Microchannel block geometric design, in (mm)

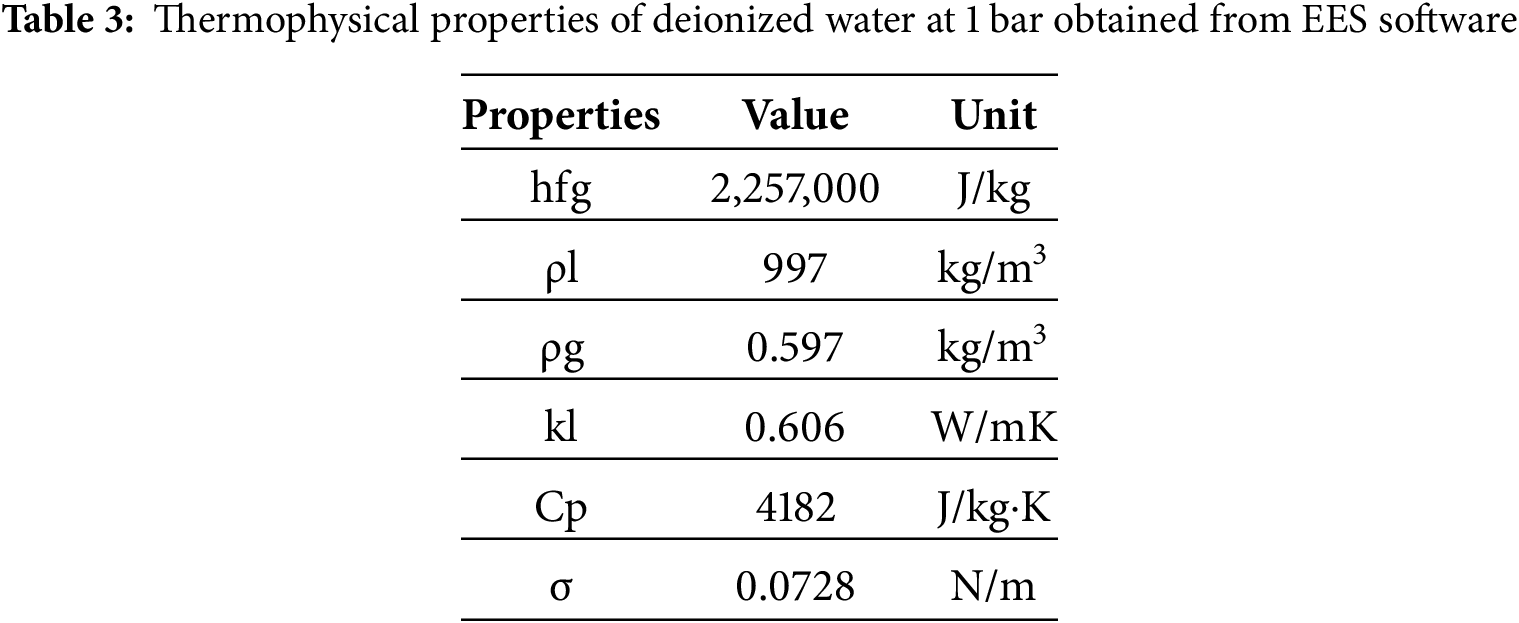

A structured and consistent experimental procedure was implemented throughout the study, as shown in Fig. 5. Prior to each test, the deionized water at near atmospheric pressure of 1 bar with a low inlet subcooling of 15 K within the loop’s reservoir was subjected to vigorous boiling to expel any dissolved gases into the surrounding environment. The flow rate was determined using a KYTOLA® Model A variable area flow meter—Finland, to measure the mass flux that was in the range of 700–1000 kg/m2·s, whereas the wall heat flux varied accordingly. Table 3 summarizes the thermophysical properties of the working fluid at atmospheric pressure.

Figure 5: Schematic of experimental facility

Prior to each experiment, the working fluid was degassed by maintaining it at vigorous boiling for 30 min to remove dissolved gases, including oxygen, which are recognized as influencing nucleation behavior, The operational conditions of particular interest—flow rate, inlet temperature, and test module outlet pressure—were then modified carefully after the degassing process to set up intended experimental conditions and obtain uniform and repeatable outcomes. After that, electrical power was supplied in an incremental way to the cartridge heaters that were embedded in the copper block. When the copper block reached thermal equilibrium, the UT3200 data acquisition system, interfaced with a personal computer, was used to record the most important parameters such as the inlet and outlet temperatures (Tin and Tout), the inlet and outlet pressures (Pin and Pout), and the thermocouple readings in the copper block. The ratio of the measured electrical power input to the heated surface area was determined by calculating the heat flux (q″) from the heated surface. After performing each set of measurements, the electrical power was raised; then, the measurement cycle was repeated.

The net pressure drops along the microchannel Pch for single phase flow is calculated as follows:

Plm quantitatively represents the pressure differential between the output and input manifolds. Several minor losses contribute to the overall pressure drop, including the input subchannel loss (∆Psch,i), the output subchannel loss (∆Psch,o), the abrupt contraction loss (∆Psc), and the abrupt expansion loss (∆Pse). These losses together are represented by ∆Ploss and can be calculated as follows [38].

Because of the rapid contraction and expansion, the pressure reductions induced by all the microscopic losses were calculated using Eq. (3) [38].

The volume significantly reduces by transitioning from a manifold to a subchannel and then from a microchannel to a subchannel. The loss parameters of ksc1 and ksc2 represent the changes that occur in the volume. In addition, the pressure loss or gain during the transition from the microchannel to the subchannel and then to the manifold is represented by the coefficients kse1 and kse2. The loss coefficient values are as follows: ksc1 = 0.5, ksc2 = 0.47, kse1 = 0.72, and kse2 = 0.81.

At the heat sink, the base heat flow was calculated using Eq. (4) [38]. P stands for the applied electrical power, and

The thermal power (P) in Watts stands for the energy transfer rate within an electrical circuit; this is computed as the product of the electrical current (I) in amperes and the electrical voltage (V) in volts, expressed by Eq. (5), as follows:

To determine the heat transfer area (

The empirical determination of parasitic thermal losses (Qloss) from microchannel test sections to ambient environments uses a static-fluid heating protocol. Electrical power inputs are incrementally applied to the substrate, while thermally insulated boundary conditions are maintained. Equilibrium temperature measurements at the channel’s base surface (Twall) and ambient reference values (Tamb) are recorded under steady-state heat transfer regimes. Sequential experimental trials at varied power levels establish a linear correlation between applied electrical power and the thermal gradient (Twall−Tamb), analyzed through regression techniques. This methodology, validated in prior studies, isolates conductive/convective losses by eliminating forced convection effects. The resultant slope-intercept relationship extrapolates baseline heat dissipation for subsequent flow-phase analyses, preserving energy conservation principles while addressing measurement uncertainties inherent to microscale thermal characterization.

Spatially resolved coefficients of convective thermal transport, denoted as hsp(z), are empirically derived according to the methodology outlined in Reference [38]. This approach enables quantification of local heat transfer characteristics along the axial dimension of the microchannel.

The microchannel geometry is defined by its height,

Assuming a condition of uniform heat flux at the microchannel wall, the local fluid temperature,

The mean Nusselt number was determined from Eq. (10), as specified in the procedure set out in reference [39].

In the case of developing laminar flow, where the (Re ≤ 2000), the analysis follows the formulation given in Eq. (11) [40]

For fully developed laminar flow (Re ≤ 2000), according to Shah and London [40], the Nusselt number correlation for this configuration is expressed as follows (Eq. (13))

For laminar developing flow (Re < 2000), Mirmanto [41] reported the following correlation

4 Validation and Uncertainty Analysis

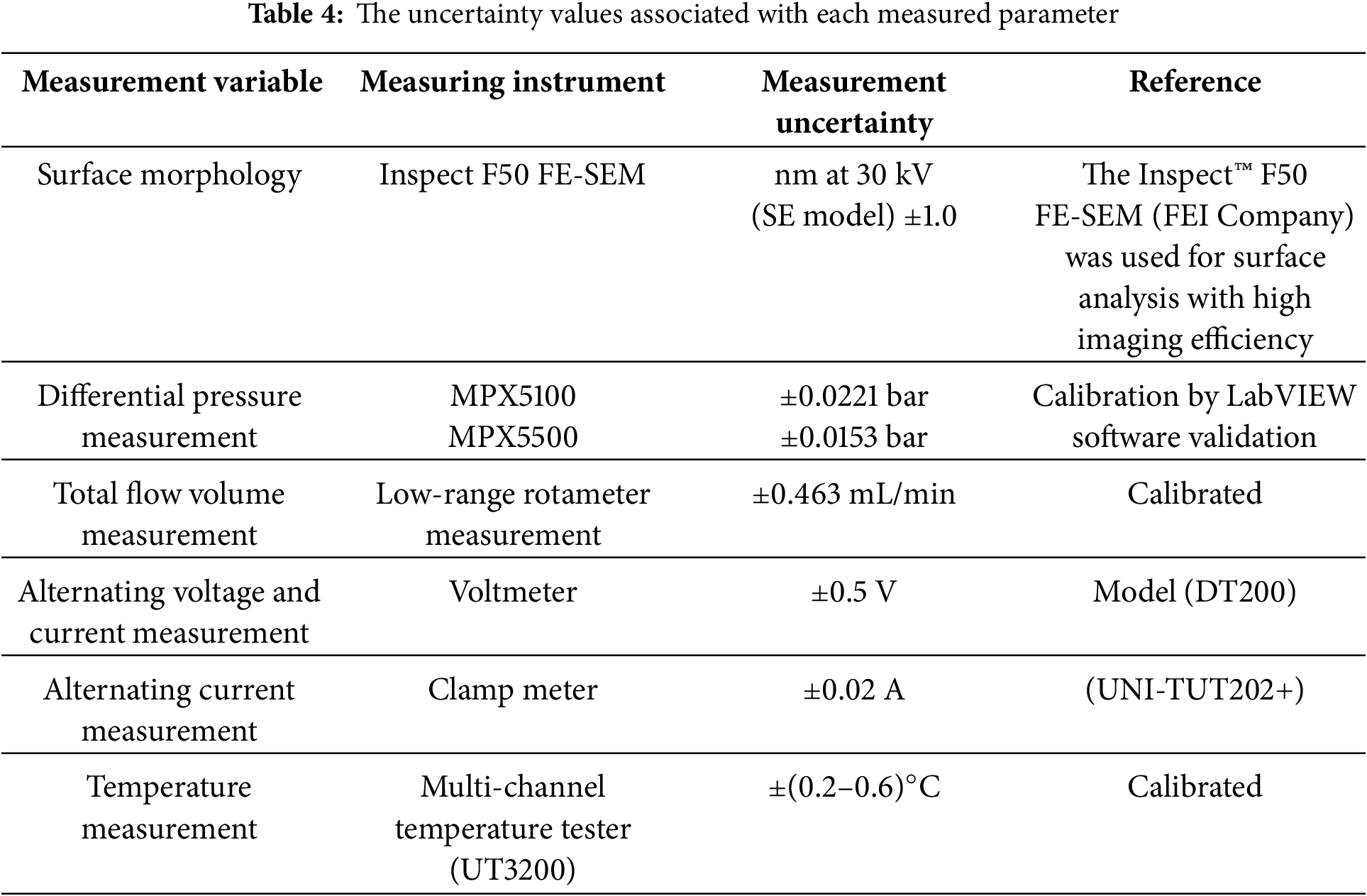

To ensure reproducibility, repeatability tests were performed by conducting each measurement at least three times under identical operating conditions. The scatter from tests was within the estimated experimental uncertainty and confirmed stable performance. The uncertainties of the measurements were determined on the basis of the precision of the measuring instruments used and error propagation according to conventional uncertainty analysis procedures. Table 4 summarizes the measurement variables, sensors utilized, and their associated uncertainties. The measured values were obtained from instrument calibration data or through repeated tests with certified procedures.

In total, 27 unique operating-condition sets were investigated, each repeated three times, resulting in 81 experimental runs. This ensured that all operating conditions were adequately covered, thereby improving the statistical reliability of the results.

5.1 GNPS and GNPS+MWCNT Nanocomposite Characterization

(FESEM, Inspect F50, USA) Characterization was used to study the surface morphology of GNPS- Hybrid GNPD+MWCNT. One of the major demands of realizing optimum nucleate boiling performance is that the intercalation and desorption of water molecules be allowed by the surface morphology.

Fig. 6a presents an overview of the cured GNP coating, while Fig. 6c shows the GNP nanostructure. These figures demonstrate the existence of large micro-cavities and the layer-by-layer loading of GNP flakes. The micro-cavities aid water in permeating into the GNP structure’s interlayers. In addition, when GNP flakes are arranged in a stratified way, water can spread efficiently, which helps more water molecules to be intercalated through the interlayers of GNP. In comparison with the confined tubular structure of MWCNT+GNPS, the GNP nanostructure offers more available space for water molecules to maneuver, making it easier for them to escape from the surface. This characteristic enhances the ability of the material to support water movement and escape, improving its performance in thermal applications.

Figure 6: FESEM micrograph of graphene nanoplatelets, (a,c) (GNPs), and (b,d) (GNPs+MWCNT) at 8000× and 120,000× taken with Inspect F50 FESEM (USA), representing the surface texture and morphology

Fig. 6b shows the morphology of the hybrid cured GNP/MWCNT coating and Fig. 6d shows the magnified image of the hybrid GNP/MWCNT nanostructure. The hybrid GNP/MWCNT coating is characterized by the agglomeration of MWCNT clusters and GNP flakes. There is a strong synergistic effect between GNP and MWCNT in facilitating water permeation and evaporation. The tubular structure of MWCNT and the open spaces between intertwining CNTs have pathway access for infiltrating water molecules. Simultaneously, a layered GNP sheet has channels for facilitating the outgoing evaporation of water molecules from the nanostructure. Such synergy between GNP and MWCNT provides a perfect result regarding hybrid coating performance for water movement and temperature control.

The contact angles were obtained as 89.4°, 73.142°, and 75.73°, respectively, for the hybrid GNP/MWCNT, GNP, and the benchmark uncoated surfaces. By observing these initial contact angle values, it can be inferred that the uncoated surface exhibits hydrophilic characteristics. The cured GNP and GNP/MWCNT surfaces demonstrate the highest hydrophilicity, indicating their enhanced affinity for water in comparison with the uncoated surface.

The exceptional hydrophilicity observed is primarily because of not only the existence of oxygenated functional groups that were introduced in the process of thermal curing but also the micro/nano-porosity inherent in both MWCNT and GNP nanostructures. Incorporating oxygenated functional groups helps water to be intercalated through the attraction of polar water molecules, whereas the tubular structure of MWCNTs and the layer-by-layer arrangement of GNP flakes create efficient pathways for water molecule ingress [42]. These micro/nano-structural features and chemical modifications are directly responsible for the observed boiling enhancement. The increased porosity and layered structure provide more active nucleation sites, while the porous CNT–GNP network promotes efficient liquid supply through capillary wicking, delaying local dryout. Moreover, the improved thermal properties of the coated surfaces accelerate temperature recovery after bubble departure, leading to a higher bubble generation frequency [43,44]. Therefore, the enhancement in flow boiling performance of GNP and GNP+MWCNT coatings is attributed to the combined effects of increased nucleation, enhanced wicking, and modified bubble dynamics.

5.2 Flow Boiling Heat Transfer

5.2.1 Nusselt Number Correlations

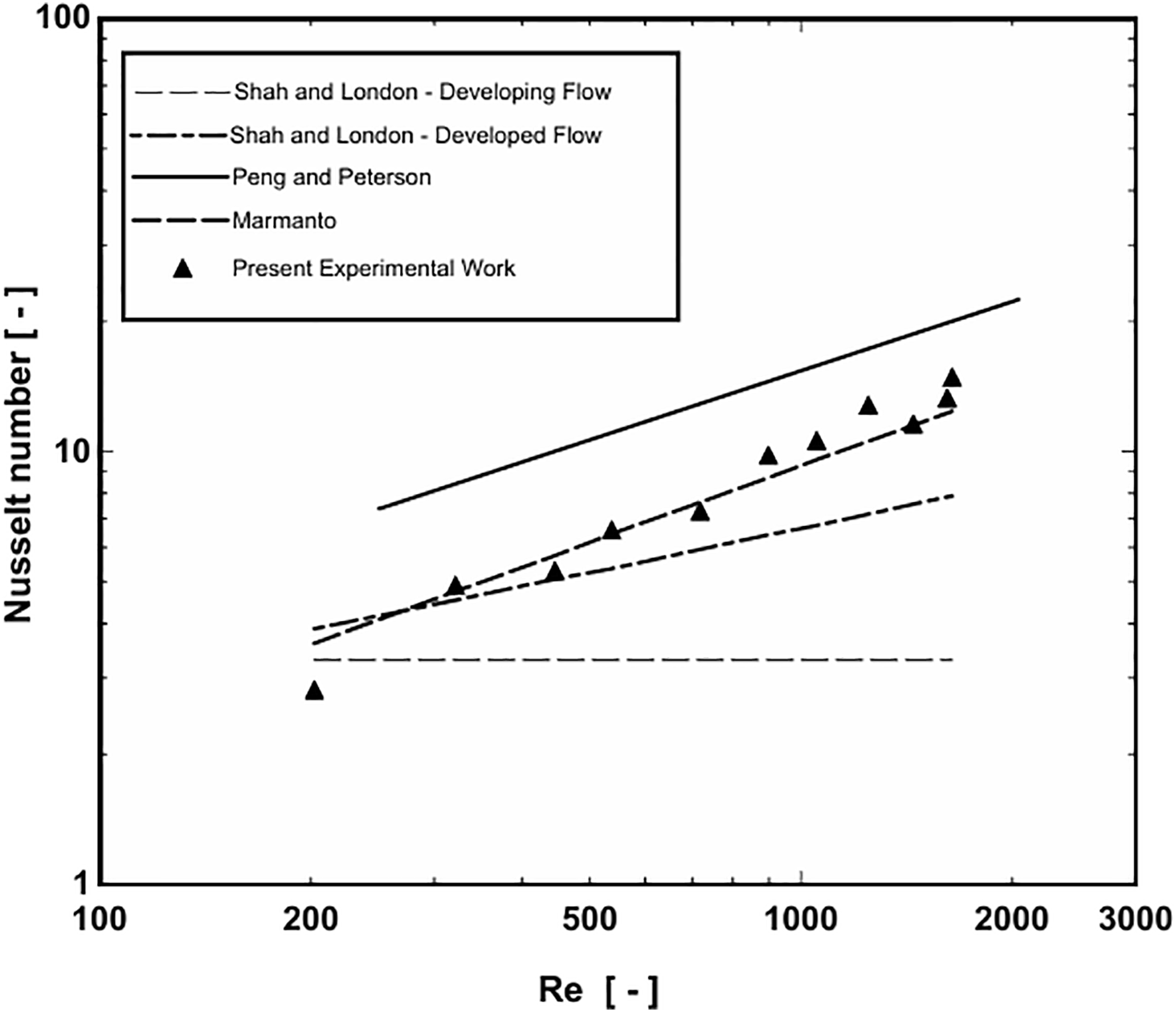

Single-phase flow tests were conducted prior to two-phase flow boiling experiments in order to establish baseline thermal performance trends. The single-phase Nusselt number, defined by the correlation in Eq. (10), was plotted against the Reynolds number (Re), as illustrated in Fig. 7. The adiabatic experiments were performed at an inlet pressure of 1 bar and an inlet temperature of 30°C, corresponding to a Reynolds number range of 202 ≤ Re ≤ 1641.

Figure 7: Experimental average Nusselt number results compared with laminar flow correlation

The experimentally obtained mean Nusselt numbers from the single-phase tests showed excellent agreement with several well-established correlations for laminar flow in microchannels [36–38], as presented in Eqs. (11), (13) and (15). It should be noted that the models of Shah and London [40] and Mirmanto [41] were originally developed for thermally developing laminar flows under constant wall heat flux conditions. Although derived for circular channels, these correlations are commonly extended to non-circular geometries through the use of the hydraulic diameter approximation, which largely explains the strong agreement observed between the experimental data and these models, particularly in the low Reynolds number regime (Re ≈ 300–700).

In contrast, Peng and Peterson [45] proposed their correlation specifically for rectangular microchannels, covering a wider applicability range of Reynolds numbers (50 < Re < 4000). They further identified the transition regime in microchannels as 400 < Re < 1000, while flows at Re > 1000 were classified as fully turbulent.

As shown in Fig. 7, the experimental trend of the average Nusselt number in the simple microchannel exhibit’s characteristics of developing flow, where Nu increases with increasing Re. This enhancement in heat transfer within the laminar regime can be attributed to the relatively thin thermal boundary layer in the developing region, which enables greater local heat transfer compared to the fully developed thermal condition.

The selection of graphene nanoplatelets (GNPs) combined with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) is based not only on their superior thermal conductivity but also on their complementary structural features. GNPs provide large, planar surfaces that enhance nucleation site density due to increased surface roughness and wettability, while MWCNTs contribute a 3D scaffold that enhances mechanical interconnectivity and suppresses nanoparticle agglomeration within the coating. Furthermore, hybrid GNP/MWCNT coatings have demonstrated synergistic effects in improving boiling heat transfer and maintaining coating integrity under thermal cycling conditions, which are critical in practical applications [46,47]

Average heat transfer in the microchannels that were coated with varying materials (GNPs and Hybrid GNPs+MWCNT) was experimentally investigated for subcooled flow boiling at different mass fluxes of 700, 850, and 1000 kg/m2·s. The uncoated microchannel was the reference. Fig. 8a–c demonstrates the flow boiling curves at these mass fluxes with a subcooled temperature fixed at 15°C. The two hydrophilic coatings, i.e., GNPs+MWCNT and GNPs, were shown to be significantly improved in performing the boiling heat transfer process over the bare copper surface for all of the mass flow rates that were taken into consideration in this study.

Figure 8: Average heat transfer coefficient vs. wall heat flux for TS, TS2, and TS3 over different mass flux: (a) 700 kg/

First, hydrophilic surface microchannels demonstrated meaningfully superior heat transfer performance in comparison with the untreated surface microchannels, with this advantage becoming more pronounced at higher mass fluxes. At a lower mass flux of 700 kg/(m2·s), the average heat transfer coefficients of hydrophilic GNPS and hydrophilic composite GNPS+MWCNT microchannels are approximately 27.2% and 14.71% higher, respectively, when compared to those of untreated surface microchannels. Conversely, at a higher mass flux of 1000 kg/m2·s, the average heat transfer coefficients of hydrophilic and hydrophilic composite (GNPS+MWCNT) microchannels increased by 42.8% and 33.95%, respectively, in comparison to untreated surface microchannels. This highlights the more significant impact of heat flux on the heat transfer characteristics of the composite hydrophilic microchannel at elevated mass fluxes.

The heat transfer coefficient (HTC) varies depending on a number of variables such as surface roughness, porosity, pore size, the surface area of the coating layer, and surface wettability. In addition, as supported by [48] findings, the GNPs’ higher thermal conductivity causes enhancement in heat conduction between nanoparticle layers because of their lowered thermal resistance. The average pore size, from among the above-noted parameters, significantly augments HTC, as noted by [49], who emphasized its importance in the overall enhancement of heat transfer.

For GNPS+MWCNT microchannels, both heat flux and mass flux had considerable effects on the two-phase HTC, with the HTC values increasing with an increase in the mass flux. The initial HTC value at G = 700 kg/m2⋅s was comparable to the value at G = 850 kg/m2⋅s; this was because of the increased adhesion of vapor bubbles to the hydrophilic GNPS+MWCNT surface, which inhibited their detachment under higher flow velocities. Fig. 8a–c compares the way the three wettability samples performed heat transfer under identical mass flux conditions. GNPS+MWCNT microchannels showed greater heat dissipation performance at low to medium heat flux levels of 212.8–464.5 kW/m2 at G = 700 kg/m2⋅s and 236.2–476 kW/m2 at G = 850 kg/m2⋅s. At a mass flux of 1000 kg/m2·s, the enhancement in heat transfer was observed to be relatively uniform along the entire length of the microchannel, with the heat transfer coefficient increasing steadily approximately in the range of 229.4–761.6 kW/m2·K. However, at high heat flux, the HTC values of the GNPS samples became comparable to the curves for the nano composite (GNPS+MWCNT) samples that were generally between those of the GNPS and uncoated surfaces and exhibited trends similar to the GNPS samples. The observed performance degradation at θ = 75.73° is attributed to a reduction in nucleation site activity, which is strongly influenced by surface wettability. According to [50] surface contact angle has a direct impact on the number and activation of nucleation sites. Higher contact angles, indicating reduced wettability, tend to suppress bubble nucleation by lowering nucleation site density. Although nucleation site density was not measured directly in this study due to optical constraints, the correlation between contact angle and HTC trends serves as an indirect indicator, consistent with established literature. Moreover, the GNPS microchannels achieved the highest heat transfer coefficients at the maximum heat flux across all mass fluxes, primarily because of delayed local dry out during stratified flow conditions. Overall, The GNP-coated surfaces demonstrated maximum heat transfer performance before local dry out under particular conditions of mass flux by maximizing the surface wettability and liquid supply. At larger contact angles, however, film stability is reduced and may cause film breakup under certain heat flux and flow conditions. This effect emphasizes the intricate interaction between liquid film dynamics and wettability in boiling heat transfer from nanostructured surfaces [51]. The claimed 33.95% HTC enhancement for GNPs+MWCNT nanocomposite coatings is a considerable enhancement and similar to the highest performing nanocoating techniques reported thus far. For instance, Sujith Kumar et al. (2015) reported a maximum HTC improvement of 44.11% with spray pyrolysis deposited Fe-doped Al2O3–TiO2 composite coatings, which indicates nanostructured coatings performance in boiling heat transfer. Such a result provides a higher benchmark against which others are measured [52].

Some previous studies have also reported some improved boiling performance with great advancements employing nanostructured coatings. Copper nanowire films, for instance, exhibited as much as 56% CHF improvement over bare copper, and silicon nanowire films showed as much as 300% CHF improvement in microchannels. Sintered aluminum coatings have also been seen to achieve 2–5 times higher heat transfer coefficient enhancement in boiling compared to plain surfaces, while TiO2 coatings are seen to have 10%–50.4% CHF enhancement based on the working fluid and the manufacturing process employed. Nevertheless, most of these enhancements have been achieved in CHF, with no clear HTC enhancements being less commonly reported [32].

It is the better enhancement in HTC that renders the novel GNPs+MWCNT technique special, apart from its ability for enhanced-quality uniformity of coating and scalability. Most of the previous approaches—like sintering, sol–gel, or adhesive-type coating—are conventionally plagued with issues of uniform dispersion of nanostructures over large surfaces or undergoing convoluted, costly processing that does not fit industrial-scale scalability. Conversely, scalable and relatively simple methods—such as spray pyrolysis or electrodeposition—are preferred due to their simplicity in doping, thickness control, tunable film composition, and scalability to be implemented more efficaciously on the large scale [19]. Due to the summed thermal benefits of the graphene nanoplatelets and the multi-walled carbon nanotubes, the GNPs+MWCNT nanocomposite can attain homogeneous dispersion and high interfacial contact with the substrate. This not only provides better thermal performance but also eliminates consistency and repeatability problems associated with earlier nanocomposite coatings. Therefore, the innovation of the process is to combine high HTC improvement with practical, scalable processing and enhanced uniformity of the coating, distinguishing it from many earlier nanocoating approaches.

5.2.3 Role of Microchannel Confinement on Heat Transfer

The influence of microchannel confinement plays a crucial role in shaping the observed boiling and heat transfer behavior. In the present study, a rectangular channel with (aspect ratio = 2.67) was employed. Previous investigations have reported that the aspect ratio strongly affects bubble dynamics and flow boiling regimes. For instance, Al-Zaidi et al. [53] demonstrated that intermediate aspect ratios can enhance heat transfer while reducing pressure drop by moderating bubble confinement and facilitating liquid replenishment. Similarly, Anredaki et al. [54] highlighted that both excessively small and aspect ratios can negatively influence bubble detachment, either by restricting bubble motion against the sidewalls or by limiting nucleation stability.

Given that the channel used in this study falls within the favorable intermediate aspect ratio range, the stable nucleation and bubble detachment observed during the experiments can be attributed to this geometric confinement effect. This behavior reinforces the thermal benefits introduced by the coating layers. Specifically, the GNP coating, with its enhanced surface wettability and uniform film stability, was able to exploit the confinement conditions more effectively, thereby achieving superior HTC performance compared to the GNPs+MWCNT composite. In contrast, the incorporation of MWCNTs may have compromised coating homogeneity due to possible agglomeration, reducing the synergistic interaction between surface properties and confinement-driven bubble dynamics.

Although high-speed cameras are often preferred for detailed bubble dynamics in flow boiling microchannels, recent studies have demonstrated that conventional optical cameras can effectively capture bubble behavior and nucleation site density. Xiao and Zhang [55] employed video imaging with bubble tracking algorithms to analyze bubble motion and growth under ultrasonic fields in vertical minichannels, showing that non-high-speed optical techniques can still provide valuable insights into boiling enhancements. Therefore, in the absence of high-speed imaging, adopting similar optical visualization methods is recommended to support nucleation and boiling performance analysis [56].

Overall, the results highlight the intricate interplay between coating characteristics and channel confinement. The aspect ratio not only governs bubble stability and detachment but also amplifies the effectiveness of surface modifications, underscoring the importance of considering geometric confinement when evaluating coating-enhanced boiling heat transfer in microchannels.

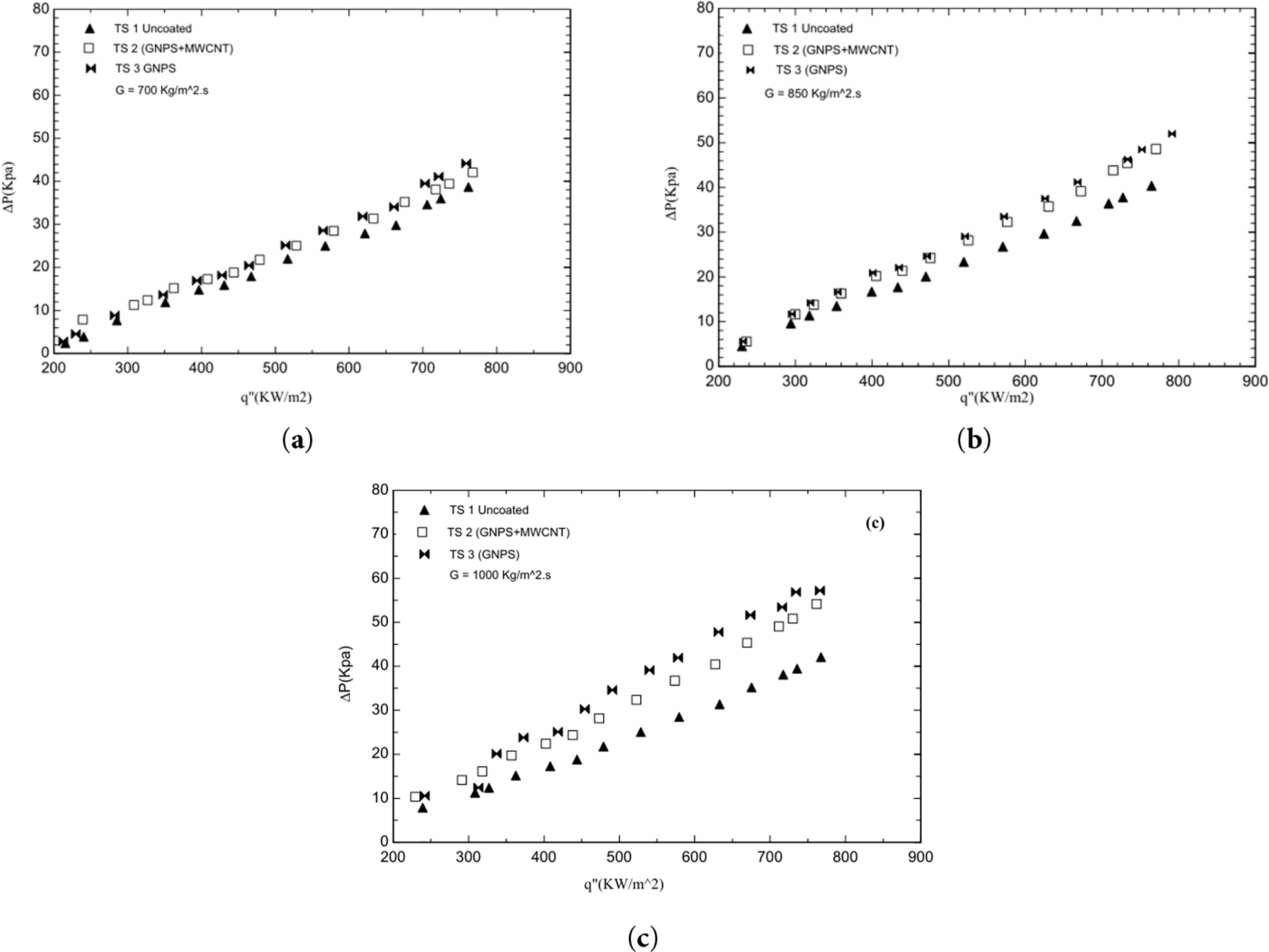

The pressure drop behavior of various microchannels considering effective heat flux is shown in Fig. 9a–c. For the conditions of two-phase flow boiling being maintained, pressure drop was controlled by vapor acceleration losses for phase transformation from liquid to vapor, and frictional pressure losses. In all the samples, the increase of linear pressure drop with an increase in the heat flux was observed at the early boiling stages, which was because of the increasing vapor fraction with transition from bubbly flow to slug flow.

Figure 9: The two-phase pressure drops variations as a function of effective heat flux at (a): G = 700 kg/m2⋅s, (b): G = 850 kg/m2⋅s, (c): G = 1000 kg/m2·s

Trapped vapors and vapor films in GNPs+MWCNT microchannels were responsible for the greater percentage of vapor. The least frictional resistance to liquid flow was on hydrophobic surfaces, and (GNPS+MWCNT) microchannels showed the greatest viscous forces. Under the conditions of high heat flux, however, GNPS samples showed the greatest pressure drops at mass flux rates of 700, 850, and 1000 kg/m2·s. This was caused by improved efficiency in the production of vapor owing to the increased densities of nucleation sites for bubbles. On the other hand, the GNPs+MWCNT samples had the least pressure drops, which was an effect of reduced vapor generation efficiency.

Pressure drop rose sharply as the heat flux reached medium-to-high values, showing the transition of flow regime to stratified flow in the GNPs+MWCNT microchannels or partial wetting flow in the GNPS microchannels. The two-phase stratified flow increased the vapor phase fraction and consequently the acceleration pressure losses, which was because of increased vapor acceleration. In this case, the slope of pressure drop curves was higher with increased surface hydrophobicity, reflecting improvement in vapor generation efficiency.

Mass flux was observed to have a substantial influence on primarily the friction pressure losses, and the pressure drop rose with an increase in mass flux. The pressure drops of all three geometries of microchannel were similar at low mass flux (G = 700 kg/m2·s) under the first boiling regime. Flow boiling suppression was found to take place at increased mass flux under the same conditions of heat flux, leading to a moderate rise in pressure drop across all the specimens. In addition, a shallower slope was found for the microchannels at low-to-moderate heat flux for G = 850 kg/m2·s in Fig. 9b compared to those at lower mass fluxes, which was because of the lower efficiency of bubble nucleation.

It was observed that under high mass flux conditions, the GNPs samples exhibited the highest pressure drop values, with a pressure drop increase of up to 36%, compared to 29% for the GNPs+MWCNT composite samples. This is owing to the increased frictional resistance in hydrophilic microchannels, where moderate liquid-solid interactions resulted in augmented viscous forces and augmented pressure losses during two-phase flow boiling. This result is consistent with the previous studies where [57,58] have indicated that hydrophilic surfaces show greater pressure drops than hydrophobic surfaces owing to increased wettability and liquid-wall adhesion. The increase in pressure drops for high heat flux coated surfaces follows theoretical expectations from models accounting for vapor acceleration losses in boiling heat transfer. When the heat flux increases, according to classical boiling flow models [1], the rate of vapor generation increases, resulting in accelerated vapor flow through the microchannels or along the heated surface. This increase in the vapor creates secondary pressure losses beyond viscous friction. Nucleation site density is increased, and boiling activity is increased using coating, thus increasing production and velocity of the vapor. Hence, the increased vapor acceleration is a major contribution to overall pressure drop, which accounts for the experimentally observed 36% increase at high flux rates. This mechanistic correlation of increased vapor formation with pressure drop is consistent with existing models of two-phase flow boiling, with vapor acceleration losses dominating at high heat flux. In addition, the increase in pressure drop can be linked to the higher surface roughness induced by the coatings, where rougher surfaces facilitate nucleation and enhance heat transfer while simultaneously intensifying flow resistance. This behavior was observed in both GNPS and GNPS+MWCNT coatings.

In this study, open microchannel heat sinks with hydrophilic surface properties were designed and fabricated. Deionized water at a controlled inlet temperature of 85°C was used as the working fluid for the flow boiling experiments.

This paper presents an experimental investigation into the characteristics and mechanisms of flow boiling heat transfer in two types of microchannels: a standard hydrophilic surface (

1. It was observed that a minor increase in contact angle, θ from 73.142° to 75.73°, resulted in a noticeable decrease in thermal performance. This degradation is attributed to diminished liquid film stability, reduced nucleation site activity, weakened capillary-driven liquid replenishment, and decreased surface uniformity. These findings underscore the crucial role of optimized surface wettability and surface structure in maintaining efficient microchannel boiling. The heat transfer performance of the hydrophilic surface microchannel was significantly superior to that of the untreated microchannel. At a lower mass flux of 700 kg/m2·s, the average heat transfer coefficients for the GNPS and GNPS+MWCNT microchannels were approximately 27.2% and 18.98% higher, respectively, compared to the untreated sample. At a higher mass flux of 1000 kg/m2·s, the enhancements in the average heat transfer coefficients reached 42.8% and 33.95% for the hydrophilic and nanocomposite hydrophilic microchannels, respectively, compared to the untreated one.

2. At high mass flux, the GNPS microchannels exhibited maximum pressure drop values, and the pressure drop ratio was as high as 36% compared to 29% for the GNPs+MWCNT composite samples. This increase in the pressure drop was owing to extra frictional resistance in the hydrophilic microchannels. The intermediate liquid-solid interaction facilitated higher adhesion between the working fluid and channel wall, leading to higher viscous forces. Because of enhanced heat flux, the increased vapor generation rate also played a role in creating more vapor acceleration losses, which contributed to the net pressure drop. The findings are a witness to the critical necessity of surface wettability to influence flow resistance in two-phase flow boiling microchannels.

3. Two-phase pressure drop in open microchannels was observed to rise with the increase in heat flux and mass flux. During the initial stage of low mass flux, the pressure drops for the whole set of samples were similar. At higher mass fluxes, i.e., medium and high values, the GNPS microchannels showed the maximum pressure drop and the GNPS+MWCNT microchannels showed the lowest values. The two-phase pressure drop performance was dominated mainly by vapor quality and vapor production efficiency.

4. Based on the findings of this study, where GNP demonstrated superior performance compared to its modified counterparts, future research could focus on exploring the underlying mechanisms responsible for this enhancement. Further investigations may also examine the integration of pure GNP with other nanomaterials or polymers to evaluate possible synergistic effects. In addition, scaling up the preparation methods and testing under real-world application conditions could provide valuable insights into the industrial feasibility of using pure GNP. Finally, comparative studies with newly developed nanostructures may help identify whether the advantages observed here are unique to GNP or part of a broader trend among similar materials.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Authors acknowledge contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Ghinwa Al Mimar and Natrah Kamaruzaman; Methodology: Ghinwa Al Mimar and Natrah Kamaruzama Investigation: Ghinwa and Kamil Talib Alkhateeb; Data curation: Ghinwa Al Mimar and Natrah Kamaruzaman; Formal analysis: Ghinwa Al Mimar and Natrah Kamaruzaman; Resources: Ghinwa and Kamil Talib Alkhateeb; Writingoriginal draft preparation: Ghinwa Al Mimar; Writingreview and editing: Natrah Kamaruzaman; Supervision: Natrah Kamaruzaman; Validation: Natrah Kamaruzaman; Project administration: Ghinwa Al Mimar and Natrah Kamaruzaman. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Thome JR, Cioncolini A. Flow boiling in microchannels. Adv Heat Transf. 2017;49(7):157–224. doi:10.1016/bs.aiht.2017.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ding GF, Li J, Kang YX. Flow boiling enhancement and fabrication of enhanced microchannels of microchannel heat sinks. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2021;175:121332. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.121332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dalkilic AS, Celen A, Erdogan M, Sakamatapan K, Newaz KS, Wongwises S. Effect of saturation temperature and vapor quality on the boiling heat transfer and critical heat flux in a microchannel. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2020;117:104768. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2020.104768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Qiu J, Zhao Q, Lu M, Zhou J, Hu D, Qin H, et al. Experimental study of flow boiling heat transfer and pressure drop in stepped oblique-finned microchannel heat sink. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2022;30:101745. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2021.101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu G, He C, Wen Q, Wang Z, Wang X, Shittu S, et al. Investigation on visualization and heat transfer performance study of the mini-channel flow boiling. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2022;138:106360. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2022.106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cheng X, Wu H. Enhanced flow boiling performance in high aspect ratio groove wall microchannels. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2021;164:120468. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.120468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Mengjie S, Chaobin D, Eiji H. Experimental investigation on the heat transfer characteristics of novel rectangle radial microchannel heat exchangers in two-phase flow cooling system for data centers. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2020;141:199–211. doi:10.1007/s10973-019-09090-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang J, Zou Z, Fu C. A review of the complex flow and heat transfer characteristics in microchannels. Micromachines. 2023;14(7):1451. doi:10.3390/mi14071451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ranjan A, Islam A, Pathak M, Khan MK, Keshri AK. Plasma sprayed copper coatings for improved surface and mechanical properties. Vacuum. 2019;168:108834. doi:10.1016/j.vacuum.2019.108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jeong J, Cho H, Kim J. Effect of thermal spray aluminum oxide coating on the long term pool boiling performance of copper surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2025;224:124917. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2024.124917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Volodin OA, Shvetsov DA, Serdyukov V, Zhukov V. Enhanced boiling and evaporation of dielectric fluids on modified surfaces for immersion cooling of electronic components—a review. Appl Therm Eng. 2025;277:127088. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2025.127088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liang G, Mudawar I. Review of channel flow boiling enhancement by surface modification, and instability suppression schemes. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;146:118864. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.118864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Qiu J, Zhao H, Luan S, Wang L, Shi H. Recent advances in functional polyurethane elastomers: from structural design to biomedical applications. Biomater Sci. 2025;13:2526–40. doi:10.1039/D5BM00122F. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang D, Chen C, Hu X, Ju F, Ke Y. Enhancing the properties of water-soluble copolymer nanocomposites by controlling the layered silicate load and exfoliated nanolayers adsorbed on polymer chains. Polymers. 2023;15(6):1413. doi:10.3390/polym15061413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Liao B, Song M, Liang H, Pang Y. Poly(ethylene oxide)/Na+-montmorillonite nanocomposites as polyelectrolytes and polyethylene-block-poly(ethylene glycol) copolymer/Na+-montmorillonite nanocomposites as fillers for reinforcement. Polymers. 2001;42(23):10007–11. doi:10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00557-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Upot NV, Fazle Rabbi K, Khodakarami S, Ho JY, Kohler Mendizabal J, Miljkovic N. Advances in micro and nanoengineered surfaces for enhancing boiling and condensation heat transfer: a review. Nanoscale Adv. 2023;5(5):1232–70. doi:10.1039/d2na00669c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mandrolko V, Termentzidis K, Lacroix D, Isaiev M. Tailoring heat transfer at silica-water interfaces via hydroxyl and methyl surface groups [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 29]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.01141. [Google Scholar]

18. Fotovvati B, Namdari N, Dehghanghadikolaei A. On coating techniques for surface protection: a review. J Manuf Mater Process. 2019;3(1):28. doi:10.3390/jmmp3010028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Escorcia-Díaz D, García-Mora S, Rendón-Castrillón L, Ramírez-Carmona M, Ocampo-López C. Advancements in nanoparticle deposition techniques for diverse substrates: a review. Nanomaterials. 2023;13(18):2586. doi:10.3390/nano13182586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Maji SK. Luminescence-tunable ZnS-AgInS2 nanocrystals for cancer cell imaging and photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2022;5(3):1230–8. doi:10.1021/acsabm.1c01247. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Kim Y, Eom HH, Kim YK, Harbottle D, Lee JW. Effective removal of cesium from wastewater via adsorptive filtration with potassium copper hexacyanoferrate-immobilized and polyethyleneimine-grafted graphene oxide. Chemosphere. 2020;250:126262. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kaveh R, Alijani H, Falletta E, Bianchi CL, Mokhtarifar M, Boffito DC. Advancements in superhydrophilic titanium dioxide/graphene oxide composite coatings for self-cleaning applications on glass substrates: a comprehensive review. Prog Org Coat. 2024;190:108347. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2024.108347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kavimani V, Prakash KS, Thankachan T, Udayakumar R. Synergistic improvement of epoxy derived polymer composites reinforced with graphene oxide (GO) plus titanium dioxide (TiO2). Compos B Eng. 2020;191:107911. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Nan D, Li X, Li D, Liu Q, Wang B, Gao X, et al. Preparation and anticorrosive performance of waterborne epoxy resin composite coating with amino modified graphene oxide. Polymers. 2023;15(1):27. doi:10.3390/polym15010027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Shao P, Chen G, Ju B, Yang W, Zhang Q, Wang Z, et al. Effect of hot extrusion temperature on graphene nanoplatelets reinforced Al6061 composite fabricated by pressure infiltration method. Carbon. 2020;162:455–64. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2020.02.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lay KK, Cheong BMY, Tong WL, Tan MK, Hung YM. Effective micro-spray cooling for LED with graphene nanoporous layers. Nanotechnology. 2017;28(16):164003. doi:10.1088/1361-6528/aa6385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Tong WL, Hung YM, Yu H, Tan MK, Ng BT, Tan BT, et al. Ultrafast water permeation in graphene nanostructures anomalously enhances two-phase heat transfer. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2018;5(13):1800286. doi:10.1002/admi.201800286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Keklikcioglu O, Dagdevir T, Ozceyhan V. Heat transfer and pressure drop investigation of graphene nanoplatelet-water and titanium dioxide-water nanofluids in a horizontal tube. Appl Therm Eng. 2019;162:114256. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2019.114256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Deka MJ, Dutta A, Chowdhury D. Tuning the wettability and photoluminescence of graphene quantum dots via covalent modification. New J Chem. 2018;42(1):355–62. doi:10.1039/C7NJ03280C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zeng J, Zhang S, Tang K, Chen G, Yuan W, Tang Y. 3-D manipulation of a single nano-droplet on graphene with an electrowetting driving scheme. Nanoscale. 2018;10(34):16079–86. doi:10.1039/C8NR03330G. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Feng J, Guo Z. Wettability of graphene: from influencing factors and reversible conversions to potential applications. Nanoscale Horiz. 2019;4:526–30. doi:10.1039/C8NH00348C. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Pedersen MLK, Jensen TR, Kucheryavskiy SV, Simonsen ME. Investigation of surface energy, wettability and zeta potential of TiO2/graphene oxide membranes. J Photochem Photobiol A Chem. 2018;366:162–70. doi:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2018.08.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kumar D, Singh K, Verma V, Bhatti HS. Microwave assisted synthesis and characterization of graphene nanoplatelets. Appl Nanosci. 2016;6(1):97–103. doi:10.1007/s13204-015-0415-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Chen J, Walther JH, Koumoutsakos P. Covalently bonded graphene–carbon nanotube hybrid for high-performance thermal interfaces. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25(48):7539–45. doi:10.1002/adfm.201501593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Galvis E. Single-phase and boiling flow in microchannels with high heat flux [master’s thesis]. Waterloo, ON, Canada: University of Waterloo; 2012. [Google Scholar]

36. Bard AJ, Faulkner LR, White HS. Electrochemical methods: fundamentals and applications. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2022. [Google Scholar]

37. Gupta SK, Misra RD. Effect of dense packed micro-/nano-porous thin film surfaces developed by a combined method of etching, electrochemical deposition and sintering on pool boiling heat transfer performance. Heat Mass Transf. 2024;60(2):281–303. doi:10.1007/s00231-023-03438-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kandlikar SG, Garimella S, Li D, Colin S, King MR. Heat transfer and fluid flow in minichannels and microchannels. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2014. [Google Scholar]

39. Özdemir MR, Mahmoud MM, Karayiannis TG. Flow boiling of water in a rectangular metallic microchannel. Heat Transf Eng. 2021;42(6):492–516. doi:10.1080/01457632.2019.1707390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Shah RK, London AL. Laminar flow forced convection in ducts. Suppl 1 to: advances in heat transfer. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

41. Mirmanto M, Kenning DBR, Lewis JS, Karayiannis TG. Pressure drop and heat transfer characteristics for single-phase developing flow of water in rectangular microchannels. J Phys Conf Ser. 2012;395:012085. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/395/1/012085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ng ECJ, Hung YM. Enhanced subcooled flow boiling in microchannels integrated with nanoporous graphene coatings of distinctive wettability. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2025;246:127065. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2025.127065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hu H, Weibel JA, Garimella SV. A coupled wicking and evaporation model for prediction of pool boiling critical heat flux on structured surfaces. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2019;136:373–82. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2019.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Zhang L, Gong S, Lu Z, Cheng P, Wang EN. A unified relationship between bubble departure frequency and diameter during saturated nucleate pool boiling. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2021;165:120640. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.120640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Peng XF, Peterson GP. Convective heat transfer and flow friction for water flow in microchannel structures. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 1996;39(12):2599–608. doi:10.1016/0017-9310(96)00035-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Devarajan M, Krishnamurthy NP, Balasubramanian M, Ramani B, Wongwises S, Abd El-Naby K, et al. Thermophysical properties of CNT and CNT/Al2O3 hybrid nanofluid. Micro Nano Lett. 2018;13(1):41–5. doi:10.1049/mnl.2017.0029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Kim SJ, Bang IC, Buongiorno J, Hu LW. Surface wettability changes during pool boiling of nanofluids and its effect on critical heat flux. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2007;50(19–20):4105–16. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2007.02.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Gupta SK, Misra RD. Flow boiling performance analysis of copper titanium oxide micro-/nanostructured surfaces developed by single-step forced convection electrodeposition technique. Arab J Sci Eng. 2021;46(12):12029–44. doi:10.1007/s13369-021-05850-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Webb RL. The evolution of enhanced surface geometries for nucleate boiling. Heat Transf Eng. 1981;2(3–4):46–69. doi:10.1080/01457638108962760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Kandlikar SG. A theoretical model to predict pool boiling CHF incorporating effects of contact angle and orientation. ASME J Heat Mass Transf. 2001;123(6):1071–9. doi:10.1115/1.1409265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Guo W, Zeng L, Liu Z. Mechanism of surface wettability of nanostructure morphology enhancing boiling heat transfer: molecular dynamics simulation. J Mol Liq. 2023;380:121678. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2023.121678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Kumar S, Suresh S, Aneesh CR, Santhosh Kumar MC, Praveen AS, Raji K. Flow boiling heat transfer enhancement on copper surface using Fe doped Al2O3–TiO2 composite coatings. Appl Surf Sci. 2015;334(32):102–9. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.08.076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Al-Zaidi HM, Mahmoud MM, Karayiannis TG. Experimental investigation of flow boiling heat transfer in mini/microchannels: effect of aspect ratio. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2020;152(1):120587. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.120587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Anredaki M, Vontas K, Georgoulas A, Miché N, Marengo M. The effect of channel aspect ratio on flow boiling characteristics within rectangular micro-passages. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022;183:122201. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.122201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Xiao J, Zhang J. Experimental investigation on flow boiling bubble motion under ultrasonic field in vertical minichannel by using bubble tracking algorithm. Ultrason Sonochem. 2023;95:106365. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2023.106365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Gerardi C, Buongiorno J, Hu LW, McKrell T. Study of bubble growth in water pool boiling through synchronized infrared thermometry and high-speed video. Int J Heat Mass Transfer. 2009;52(5–6):1187–97. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2008.07.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Vontas K, Andredaki M, Georgoulas A, Miché N, Marengo M. The effect of surface wettability on flow boiling characteristics within microchannels. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2021;172:121133. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.121133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhang Y, Wu H, Zhang L, Yang Y, Niu X, Zeng Z, et al. Flow pattern study and pressure drop prediction of two-phase boiling process in different surface wettability microchannel. Micromachines. 2023;14(5):958. doi:10.3390/mi14050958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools