Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Drying Characteristics and Process Optimization of Banana Slices Using Hot Air-Infrared Combined Drying

Engineering Research Center for Forestry Equipment of Hunan Province, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, 410004, China

* Corresponding Author: Dan Huang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovations in Drying Technologies: Bridging Industrial, Environmental, and Energy Efficiency Challenges)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(6), 1981-1999. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.074593

Received 14 October 2025; Accepted 02 December 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

Bananas are highly perishable after harvest, and processing them into dried products is a crucial approach to reducing losses and adding their economic values. To address the inefficiency and prolonged duration of traditional hot air drying (HAD) and the quality inconsistency associated with single infrared drying (IRD), this study proposed a novel hot air-infrared combined drying (HAD-IRD) strategy. The effects of HAD, IRD, and HAD-IRD on the drying kinetics, color, rehydration capacity, moisture diffusion mechanism, and sensory quality of banana slices were systematically investigated. The parameters of the combined drying process were optimized using an L9(33) orthogonal experimental design. Results indicated that both IRD and HAD-IRD significantly reduced drying time compared to single HAD. While single IRD achieved a rapid drying rate, the lack of effective convective airflow led to potential case-hardening and unstable product quality. In contrast, the HAD-IRD strategy demonstrated a synergistic effect. The optimal parameters were determined as follows: hot air temperature of 70°C, infrared temperature of 60°C, and radiation distance of 16 cm. Under these optimized conditions, HAD-IRD reduced the total drying time by over 70% while simultaneously yielding products with superior color, higher sensory scores, and improved rehydration ratio. This study confirms that HAD-IRD is an efficient and high-quality drying method for banana slices, providing a reliable theoretical foundation and technical solution for the drying of thermosensitive fruits.Keywords

Banana is one of the most important tropical fruits globally [1], characterized by its massive production and high nutritional value, and being rich in carbohydrates, potassium, vitamins, and dietary fiber [2]. However, bananas exhibit high postharvest respiratory activity, leading to rapid softening and decay [3], poor storability, and low tolerance for long-distance transport, which results in significant postharvest losses [4]. Consequently, processing fresh bananas into dried products that are easy to preserve and possess desirable flavor and texture is a key way to extend the industrial chain, enhance added value, and reduce waste. Among these products, banana chips have gained widespread consumer popularity due to their crisp texture, and unique flavor [5].

Drying is the core step in banana chip processing, aimed at removing moisture to inhibit microbial activity and extend shelf life, while simultaneously preserving the product’s nutritional components, color, flavor, and ideal crisp texture as much as possible. Currently, Hot Air Drying (HAD) is widely adopted due to its simple equipment, operational convenience, and relatively low cost [6–9]. Farias et al. [10] investigated the heat and mass transfer and volume change of banana slices during HAD, with the finding that the hot air temperature significantly influenced the heating, dehydration, and drying rate of the samples. Drying at a higher hot air temperature combined with a lower air relative humidity resulted in a higher rate of product drying and a shorter drying time, providing valuable insights for the parameter selection in the HAD stage. However, conventional HAD has significant drawbacks, including long drying times, high energy consumption, and low thermal efficiency. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures can lead to severe enzymatic and non-enzymatic browning in banana chips, resulting in darkening color, substantial loss of heat-sensitive nutrients (such as vitamins), and the potential formation of a severely shrunken texture, ultimately compromising product quality and commercial value.

To overcome the limitations of single HAD, various novel drying technologies and combined drying strategies have been actively explored in recent years [11–15]. For example, Wang et al. [16] demonstrated that compared to conventional HAD, the application of high-voltage electric field-assisted HAD significantly accelerated the drying rate, reduced processing time, and yielded final products with markedly superior quality. Madhankumar et al. [17] investigated the drying kinetics, energy efficiency, and environmental impact of bitter gourd using an innovative forced-convection indirect solar dryer equipped with copper thin fins and paraffin-wax thermal energy storage. Their results demonstrated that this novel solar drying system exhibited high efficiency and environmental sustainability, showing significant potential for sustainable food drying applications. However, the authors also pointed out that climatic variability and seasonal fluctuations could alter the system’s performance, thereby affecting its drying efficiency. Infrared Drying (IRD), as an efficient and clean drying method, utilizes infrared radiation energy to penetrate the material directly and be absorbed by internal water, converting it into thermal energy. It offers advantages such as uniform heating, fast drying rate, and high thermal efficiency [18–20]. Tao et al. [21] summarized the application of IRD in the field of fruit and vegetable dehydration. Their findings confirmed that infrared drying technology exhibited penetrative properties, which significantly enhanced drying efficiency. The technique offered multiple advantages, including minimal energy loss, accelerated heat absorption rates, reduced energy consumption, and uniform temperature distribution. Furthermore, infrared radiation could partially inactivate enzymes, contributing to better preservation of color and certain nutritional components in fruits and vegetables. However, single-layer infrared drying may sometimes cause surface overheating or scorching, while internal moisture migration remained insufficient, thereby compromising the uniformity of the final product.

Given the distinct characteristics and limitations of both HAD and IRD, combining them to form a Hot Air-Infrared Combined Drying (HAD-IRD) technology holds promise for creating synergistic effects and achieving complementary advantages. Optimizing the key parameters of this combined drying process through orthogonal experimental design is therefore of significant interest. Tabtiang et al. [22] investigated the application of HAD coupled with infrared radiation in the production of banana chips. Their study demonstrated that the HAD-IRD approach not only achieved significantly higher drying efficiency compared to HAD alone, but also improved the crispness and overall product quality of the banana chips. In a study on the drying kinetics and process parameter optimization of Hami melon slices using HAD-IRD, Chang [23] similarly found that compared to single HAD, the HAD-IRD approach could enhance the drying rate, shorten the drying duration, and accelerate the overall drying process. Their research further demonstrated that the drying temperature, slice thickness, and infrared radiation distance all exerted significant influences on product quality attributes, including color, hardness, and vitamin retention.

Based on the aforementioned considerations, although individual studies have validated the potential advantages of HAD-IRD in specific applications, a systematic optimization of its critical process parameters—particularly the synergistic configuration of hot air temperature, infrared temperature, and radiation distance—for banana chip production remains insufficiently explored. Therefore, this study aims to systematically investigate the drying characteristics of banana slices under HAD, IRD, and HAD-IRD regimes. By employing an L9(33) orthogonal experimental design, it focuses on optimizing the key interactive parameters of the HAD-IRD process. The objective is to elucidate the synergistic drying mechanisms, quantitatively evaluate the quality attributes (including color, texture, rehydration capacity, and sensory properties) of the final product, and ultimately establish an efficient and high-quality drying protocol for banana chips. The findings are expected to provide both theoretical insight and practical guidance for reducing postharvest losses and enhancing the commercial value of banana products.

The bananas used in the experiment were Fen Jiao (also known as Chinese dwarf banana, Musa AA Group ‘Xiāngyá jiāo’) purchased from a local supermarket in Changsha, China. Bananas at a maturity stage of 7–8 (commercially mature, characterized by bright yellow peels with slight greenish tints), uniform in fruit size and color, and free from pests, diseases, and mechanical damage were selected for the experiments.

DHG-9075A Electric Thermostatic Blow-drying Oven (Fig. 1) (Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), temperature control accuracy ≤ ±1°C, with a box size of 450 × 440 × 500 mm3 and a constant air velocity of 1 m/s; YLHW Short-wave Electric Thermostatic Blow-drying Oven (Fig. 2) (Wujiang Yonglian Mechanical Equipment Factory, Suzhou, China), temperature control accuracy ≤ ±1°C, with a box size of 450 × 350 × 400 mm3, containing four 500 W infrared lamps inside; HC5003X Electronic Analytical Balance (Shanghai Huachao Industrial Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), with an accuracy of 0.001 g; WR-10 Colorimeter (Shenzhen Wefo Photoelectric Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), with a D65 light source and the CIELAB color space.

Figure 1: Hot air drying oven

Figure 2: Infrared drying oven

The peeled bananas were sliced into pieces with a uniform thickness of 6 mm using a mechanical slicer. The slices were immediately immersed in a prepared color-protecting solution for 10 min. The solution consisted of 0.05% (w/v) citric acid, 0.5% (w/v) ascorbic acid (Vc), and 0.6% (w/v) sodium chloride (NaCl) [24].

The pretreated banana slices were arranged in a single layer on trays, the trays were then placed in a drying oven. Drying temperatures were set at 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C based on the pre-experiments, respectively. During the process, the samples were weighed every 30 min. The moisture content at different time points was calculated based on the initial moisture content and the sample weight. The experiment continued until the dry basis moisture content of the banana slices dropped below 5% [25].

The pretreated banana slices were spread evenly on the sample tray of an infrared dryer with a power of 500 W. The experimental design for infrared drying comprised two distinct sets. The first set of experiments was performed by maintaining a constant radiation distance of 16 cm and systematically varying the infrared temperature at 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C. The second set of experiments was conducted by fixing the infrared temperature at 60°C and altering the radiation distance to 14, 16, and 18 cm. Drying commenced once the dryer reached the set temperature. During this process, the samples were weighed at 10-min intervals. The moisture content at different time points was calculated based on the sample weight until the dry basis moisture content decreased below 5%.

2.3.4 Hot Air-Infrared Combined Drying (HAD-IRD)

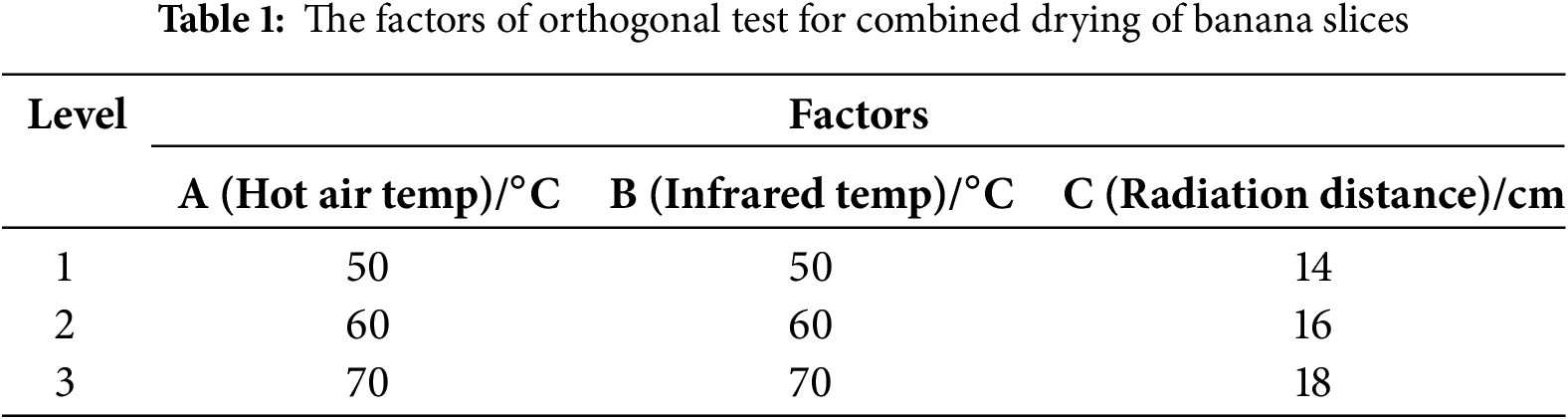

In the combined drying process, the samples were first pre-dried using HAD until the dry basis moisture content was reduced to about 55%. Subsequently, IRD was applied to further reduce the moisture content to the target value [26]. An orthogonal experimental design, as shown in Table 1, was employed to optimize the key parameters of this combined drying process [27]. The moisture content transition point was determined through preliminary experiments, which revealed that when the moisture content (dry basis) of banana slices during HAD fell within the range of 43%–67%, the hot air drying rate decreased significantly. Continuing HAD beyond this point would require substantially prolonged drying time, lead to reduced product quality, and higher energy consumption.

All drying experiments described above were performed in triplicate. The average moisture content values from the replicates were used for plotting and analysis. Upon completion of drying, the samples were immediately packaged for subsequent analysis.

2.4 Moisture Content Determination (Mt)

The moisture content was determined using the standard oven-drying method at atmospheric pressure. The moisture content at time t (Mt) was calculated using the following formula:

where Mt is the dry basis moisture content of the banana slice at time t (%);

The drying rate (DR) can reflect the ability to removing moisture per unit mass of the material to be dried per unit time:

where

The color parameters of the banana slices, namely

where

2.7 Rehydration Ratio Measurement

The dried samples were immersed in a beaker containing 150 mL of water maintained at 90°C. After 5 min, the samples were removed, drained, and the surface moisture was gently blotted with absorbent paper before weighing. The Rehydration Ratio (RR) was calculated as the ratio of the mass of the sample after rehydration to its mass before rehydration, using the following formula:

where

where

2.9 Effective Moisture Diffusivity

The effective moisture diffusivity (Deff) is a critical parameter representing the diffusion of moisture within the material during drying, reflecting the material’s dehydration capability under specific drying conditions [29]. A higher effective moisture diffusivity indicates easier migration and diffusion of internal moisture. Based on Fick’s second law of diffusion, the calculation equation for the effective moisture diffusivity was derived and transformed into its logarithmic form [30]:

where Deff is the effective moisture diffusivity (m2/s); L is the half-thickness of the drying material (m); t is the drying time (s); MR is the dimensionless moisture ratio.

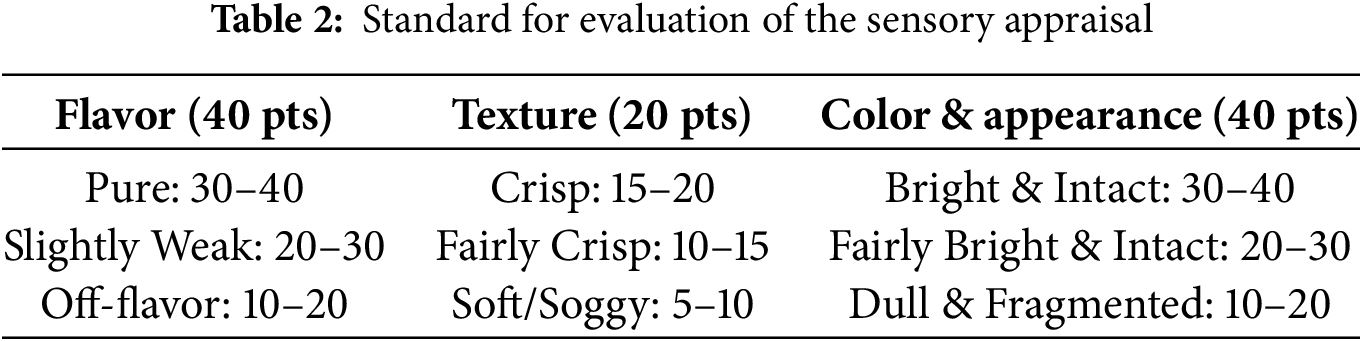

Sensory evaluation was conducted using a scoring system to assess product quality. The dried banana slices were evaluated and scored based on flavor, color & appearance, and texture, with a total possible score of 100 points. Higher scores were assigned for a purer flavor, a crispier texture, and a brighter, more intact color and appearance. Conversely, lower scores were given for the presence of off-flavors, a soft or soggy texture, and a dull or fragmented appearance. The detailed scoring criteria are presented in Table 2. For each sample group, five random individuals were recruited for evaluation, and the results were averaged [31].

A comprehensive score (S) was calculated to reflect the overall drying performance, considering both the drying process efficiency and the final product quality, based on the drying rate (Y1), sensory evaluation score (Y2), and rehydration ratio (Y3). Considering their relative importance (Drying rate > Sensory evaluation > Rehydration ratio), weights were assigned in a 3:2:1 ratio. After normalization, the final weights were: λ1 = 1/2 for drying rate, λ2 = 1/3 for sensory evaluation, and λ3 = 1/6 for rehydration ratio. The comprehensive score (S) was calculated using the following formula:

where

3.1 Characteristics of Hot Air Drying (HAD)

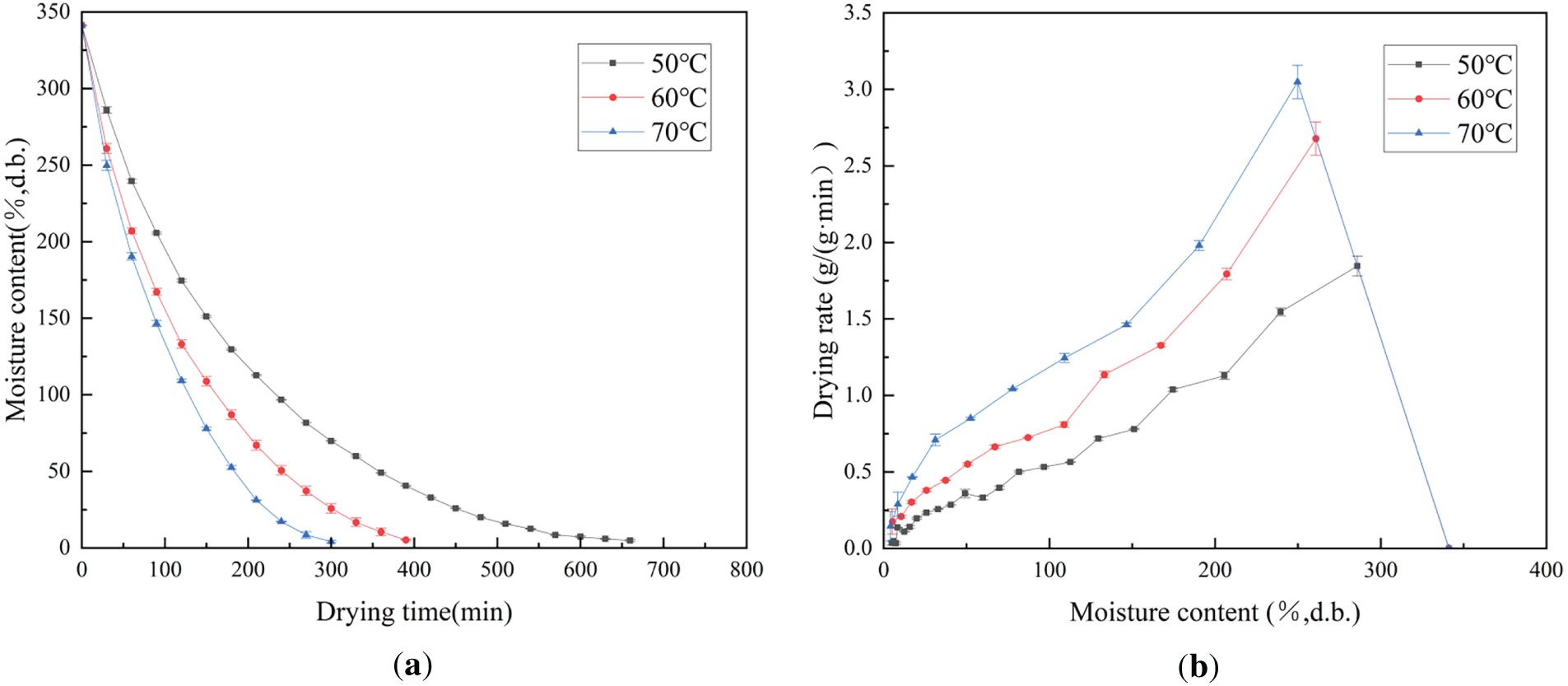

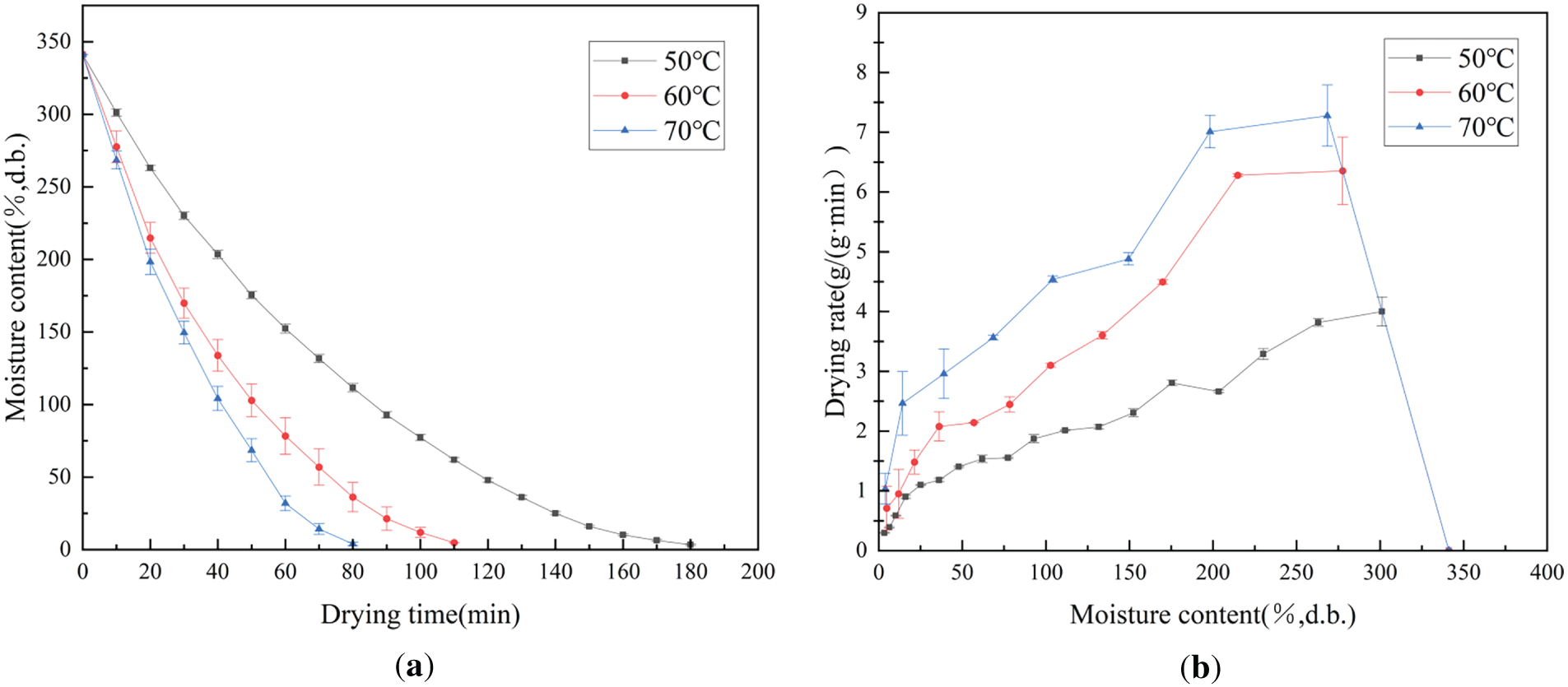

Banana slices were dried at hot air temperatures of 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C, respectively. The drying curves are shown in Fig. 3. As expected, the total drying duration decreased with increasing temperature, requiring 660 min (50°C), 390 min (60°C), and 300 min (70°C) to reach the target moisture content. At all temperatures, the moisture loss was rapid during the initial stage but gradually slowed down as drying progressed [32]. This phenomenon can be attributed to the presence of both free water with high mobility, and bound water. In the initial phase, the moisture content, particularly the free water content, is high. The banana slice surfaces are directly exposed to the hot air, facilitating the relatively easy migration of this highly mobile water. As drying proceeds, the surfaces of the banana slices undergo structural changes: the cell structures soften, shrink, and collapse. This leads to a reduction in porosity and diffusion pathways, effectively blocking the micro-channel formation. Consequently, the resistance to moisture migration increases, and the removal of the remaining bound water, which has limited mobility, becomes progressively more difficult, thereby slowing down the overall drying process.

Figure 3: HAD characteristics of banana slices: (a) Mt vs. drying time; (b) DR vs. Mt

As shown in Fig. 3b, higher temperatures resulted in greater drying rates (DR) and shorter drying times. The entire drying process of banana slices was predominantly characterized by the falling rate period, with no distinct constant rate phase observed—a typical feature of convective drying for porous fruit and vegetable materials. The drying rates at all temperatures exhibited a declining trend. This phenomenon occurs because the free water within the banana slices continuously diffuses to the surface and evaporates rapidly during the initial stage, leading to high DR values. As drying progresses, the easily removable free water diminishes, leaving bound water that is tightly associated with the internal structure of the material. The limited mobility of this bound water increases mass transfer resistance, causing a gradual decrease in the drying rate. However, as a surface-to-interior heating method, HAD primarily acts on the material surface, resulting in rapid surface moisture loss and the formation of a dense layer that impedes outward moisture migration [33,34]. Consequently, the drying process quickly transitions from being controlled by surface evaporation to being governed by internal diffusion—entering the falling rate period. At the high temperature of 70°C, the DR declined more rapidly, which may be attributed to faster surface moisture loss, leading to pronounced shrinkage and the formation of a dense, hard crust that hindered internal moisture transfer. In contrast, at 50°C, surface shrinkage was less severe; however, due to the lower driving force for internal moisture migration, the overall drying rate remained lower than that at 70°C.

In summary, hot air drying of banana slices is an internal moisture diffusion-controlled process without a constant rate period. Although increasing the hot air temperature can effectively enhance the drying rate and shorten the drying time, there exists a practical limit. Excessively high temperatures may adversely affect product quality due to surface case-hardening and increased risk of thermal damage.

3.2 Characteristics of Infrared Drying (IRD)

3.2.1 Effect of Infrared Temperature

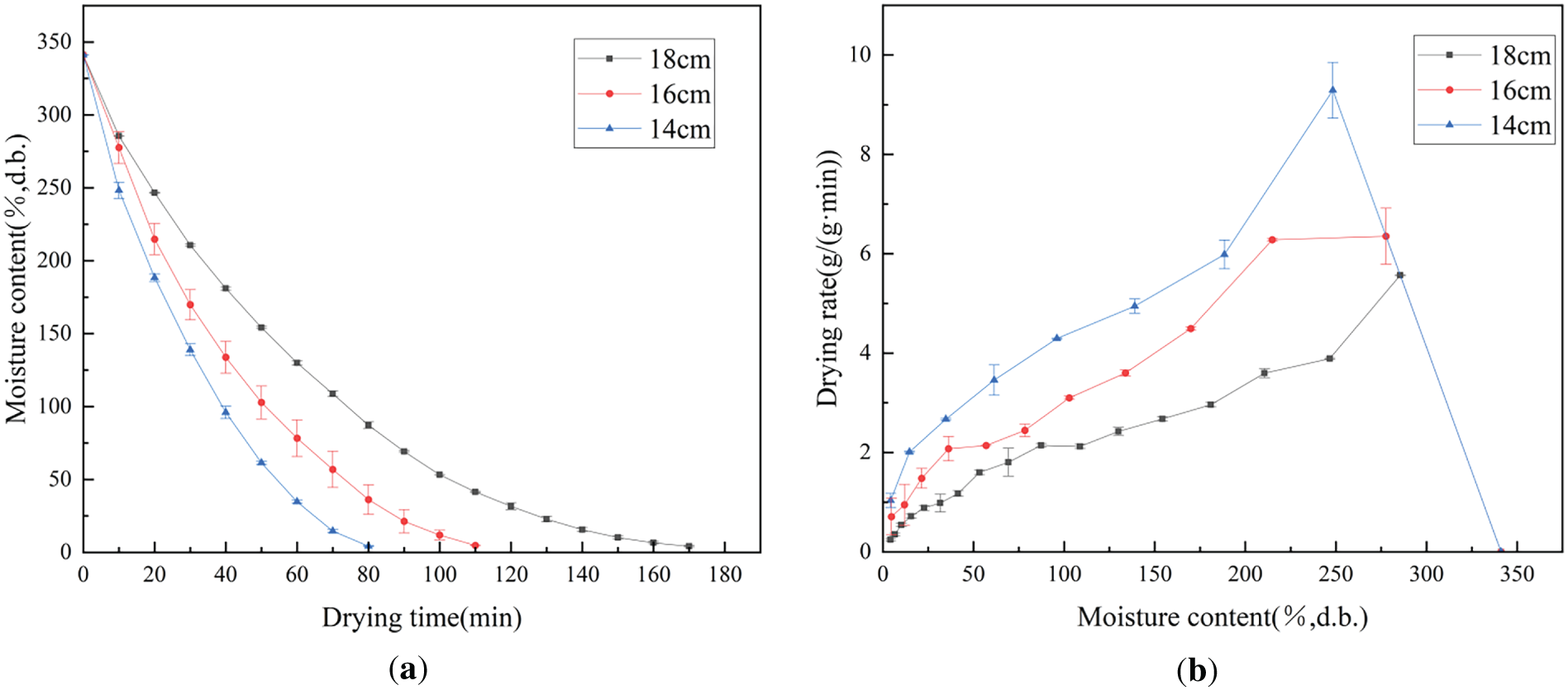

Fig. 4 illustrates the drying characteristics of banana slices undergoing Infrared Drying (IRD) at temperatures of 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C, with a fixed radiation distance of 16 cm. Similar to HAD, higher infrared temperatures resulted in shorter total drying times, specifically 180, 110, and 80 min at 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C, respectively. This heating modality generates heat simultaneously within and on the surface of the banana slices, which helps mitigate the hindrance effects caused by the temperature gradient and surface case-hardening that can occur in HAD where heat is primarily transferred from the surface. Consequently, the observed DR values were relatively higher. It is evident that the drying times for IRD were consistently shorter than those for HAD under comparable temperature conditions, with a reduction by up to 73%.

Figure 4: IRD characteristics of banana slices (Different Temperatures): (a) Mt vs. drying time; (b) DR vs. Mt

Fig. 4b illustrates the relationship between the DR and MC. The DR values at different temperatures exhibited a continuous falling rate period throughout the entire process. This phenomenon can be attributed to the rapid evaporation of a substantial amount of moisture from both the surface and the interior of the banana slices at the initial stage, facilitated by the penetrating nature of infrared heating. Subsequently, the declining drying rate was governed by the combined effects of the low mobility of the remaining bound water, structural changes such as surface softening and pore reduction, and potential case-hardening at elevated temperatures, which collectively increased the resistance to moisture migration. The consistent absence of a constant rate period across all drying curves indicates that the infrared drying process of banana slices was predominantly controlled by internal moisture diffusion mechanisms from beginning to end.

A comparison between HAD and IRD revealed that the drying rate of banana slices under IRD was significantly higher than that under HAD, with the drying time reduced by up to 73%. This is because HAD is a surface heating method where moisture evaporates directly from the surface [35]. Under HAD conditions, the surface of the banana slices is prone to shrinkage, which impedes the outward migration of internal moisture. The HAD drying plots appeared to be more linear, representing a more consistent removal of moisture during drying. A similar trend was seen in studies with onions [36,37]. In contrast, IRD provides more uniform heating by utilizing infrared radiation to penetrate and directly heat the material’s interior, enabling simultaneous moisture removal from both internal and external regions. The volumetric heating mechanism of IRD reduces the thermal gradient and the shrinkage effects commonly prevalent in HAD. Consequently, IRD achieves a higher drying rate and a shorter drying time [38–41]. Similar studies on carrot drying have also demonstrated that the drying rate of IRD remains consistently higher than that of HAD throughout the entire drying process [42].

3.2.2 Effect of Radiation Distance

Fig. 5 shows the drying characteristics of banana slices under IRD at a fixed temperature of 60°C with varying radiation distances of 18, 16, and 14 cm. A shorter radiation distance resulted in a shorter total drying time, specifically 170, 110, and 80 min at distances of 18, 16, and 14 cm, respectively. This is because a shorter distance corresponds to a higher radiative energy flux incident on the banana slices. This result in faster heating, stronger drying driving force, and an effect similar to increasing infrared temperature.

Figure 5: HAD characteristics of banana slices (Different Radiation Distances): (a) Mt vs. drying time; (b) DR vs. Mt

A comparison between the effects of infrared temperature and radiation distance reveals remarkably similar drying characteristics. A shorter radiation distance effectively mimics an increase in infrared temperature, with both conditions exhibiting a continuous falling rate period. Notably, the initial drying rate observed at a 14 cm radiation distance was even higher than that achieved by raising the temperature to 70°C at a 16 cm distance, and was followed by a more rapid decline in rate. This can be attributed to the higher radiation intensity associated with a shorter distance, which delivers greater energy flux to the banana slices. Therefore, when analyzing and optimizing the IRD process for banana slices, it is imperative to consider both infrared temperature and radiation distance concurrently, as these parameters interact to critically determine the drying kinetics.

3.3 Characteristics of Hot Air-Infrared Combined Drying (HAD-IRD)

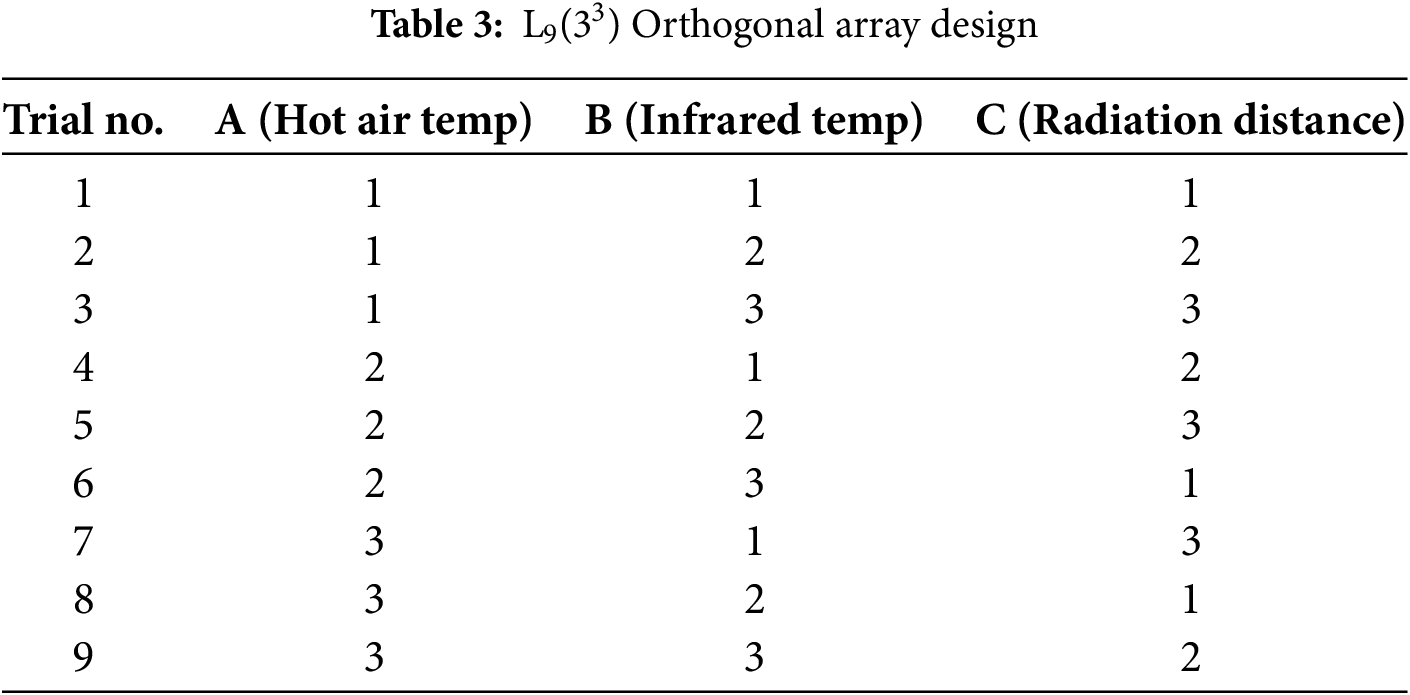

This study proposed a combined drying approach integrating HAD and IRD. The initial stage utilizes HAD to remove a substantial portion of the free water from the product, followed by an IRD stage to complete the drying of the banana slices. This strategy not only retains the relatively high drying rate characteristic of the initial HAD phase but also reduces the operational load on the infrared system, thereby enhancing the overall drying efficiency. Furthermore, this approach enhanced the drying rate while simultaneously ensuring the product quality. To optimize this combined drying process, an L9(33) orthogonal experimental design was employed (see Table 3). The factors investigated were Hot Air Temperature, Infrared Temperature, and Infrared Radiation Distance [43].

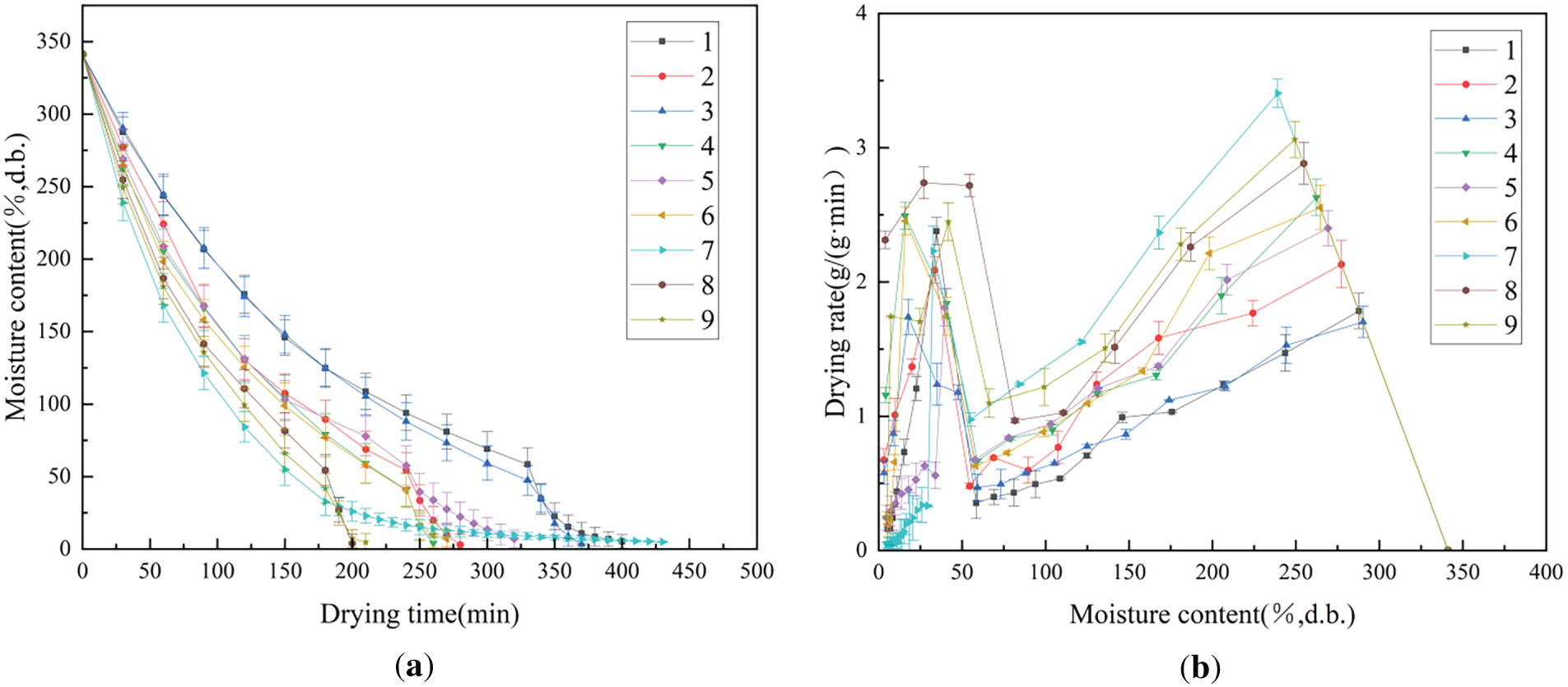

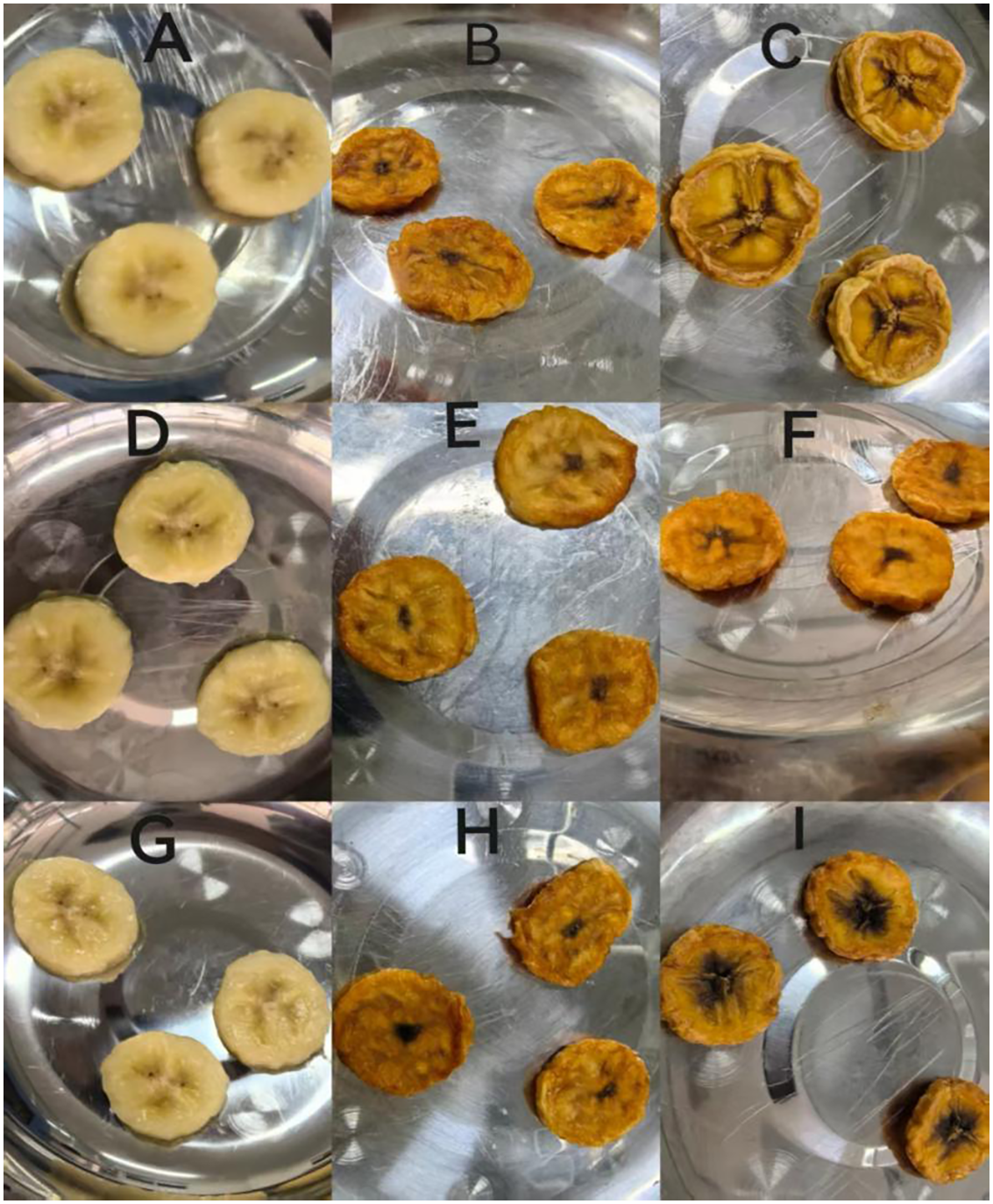

Fig. 6 shows the HAD-IRD characteristics of banana slices and Fig. 7 presents the images of banana slices during the drying process. Based on the analysis of Fig. 6, significant differences in drying efficiency were observed among the different parameter combinations of the HAD-IRD process. Specifically, Trial 7 (A3B1C3) exhibited the lowest drying efficiency and the longest total drying time. This is primarily attributed to its incompatible parameter settings: a high hot air temperature (70°C) combined with a low infrared temperature (50°C) and a large radiation distance (18 cm). During the initial drying stage, while the high-temperature hot air rapidly removed surface free water, it also readily caused excessive surface moisture loss, leading to the formation of a dense, hard crust. This crust significantly increased the resistance to subsequent moisture migration. When the process transitioned to the intermediate and later infrared drying stages, the insufficient infrared energy input failed to effectively penetrate the material or provide adequate driving force for the migration of internal bound water. Consequently, the drying process became exceedingly slow during the falling rate period. This result underscores that in HAD-IRD, the process parameters of the sequential stages must be well-matched. Excessively high initial hot air temperatures, without sufficiently intense subsequent infrared radiation, not only fail to enhance efficiency but can paradoxically prolong the total drying time by exacerbating surface case-hardening, as shown in Fig. 7C.

Figure 6: HAD-IRD characteristics of banana slices: (a) Mt vs. drying time; (b) DR vs. Mt

Figure 7: Images of banana slices under different HAD-IRD drying conditions: (A–C) Trial 7; (D–F) Trial 8; (G–I) Trial 9: (A,D,G) Fresh Banana Slices; (B,E,H) Banana slices at the intermediate drying stage; (C,F,I) Dried banana slices

In stark contrast to Trial 7, Trials 8 (A3B2C1: HAD 70°C, IRD 60°C, Distance 14 cm) and 9 (A3B3C2: HAD 70°C, IRD 70°C, Distance 16 cm) demonstrated superior performance. In Fig. 6a,b, the drying curves for these two groups show a steep decline, indicating significantly shorter total drying times and maintenance of a high drying rate throughout the process. Trial 8 (A3B2C1) employed a strategy of “high-intensity HAD + medium-intensity IRD (short distance)”. The initial HAD stage at 70°C rapidly removed a substantial amount of free water. The subsequent transition to IRD at 60°C, with its short radiation distance (14 cm) and consequently high energy flux, allowed for effective internal heating. This provided a powerful driving force for internal moisture migration, effectively overcoming the slight surface hardening potentially formed in the initial stage. Furthermore, the moderate infrared temperature (compared to 70°C) reduced the risk of thermal damage to product color and nutrients. This indicates that a balanced yet robust subsequent infrared treatment is the key to ensuring both the efficiency and quality of the combined drying process. Trial 9 (A3B3C2) represented a “consistently high-intensity” mode. The combination of high-temperature HAD and high-temperature IRD (70°C) provided the maximum drying driving force, resulting in a particularly prominent drying rate curve in the initial stage. However, compared to its final product color data (Table 4), its ΔE value was likely higher than that of Trial 8, suggesting that while efficiency is extremely high, the consistently high temperatures might have a slight negative impact on color preservation, as shown in Fig. 7I. This reveals a necessary trade-off between pursuing ultimate efficiency and guaranteeing optimal product quality.

In conclusion, HAD-IRD is not a simple superposition of two techniques but a system requiring precise synergy. The primary task of the initial HAD stage is to effectively and controllably remove free water, preparing the material for subsequent stages while avoiding surface hardening caused by excessively high temperatures or prolonged duration. The core mission of the subsequent IRD stage is to break through the bottleneck of the falling rate period, which requires sufficient and uniform energy input to drive internal moisture migration, while simultaneously considering the preservation of heat-sensitive quality attributes.

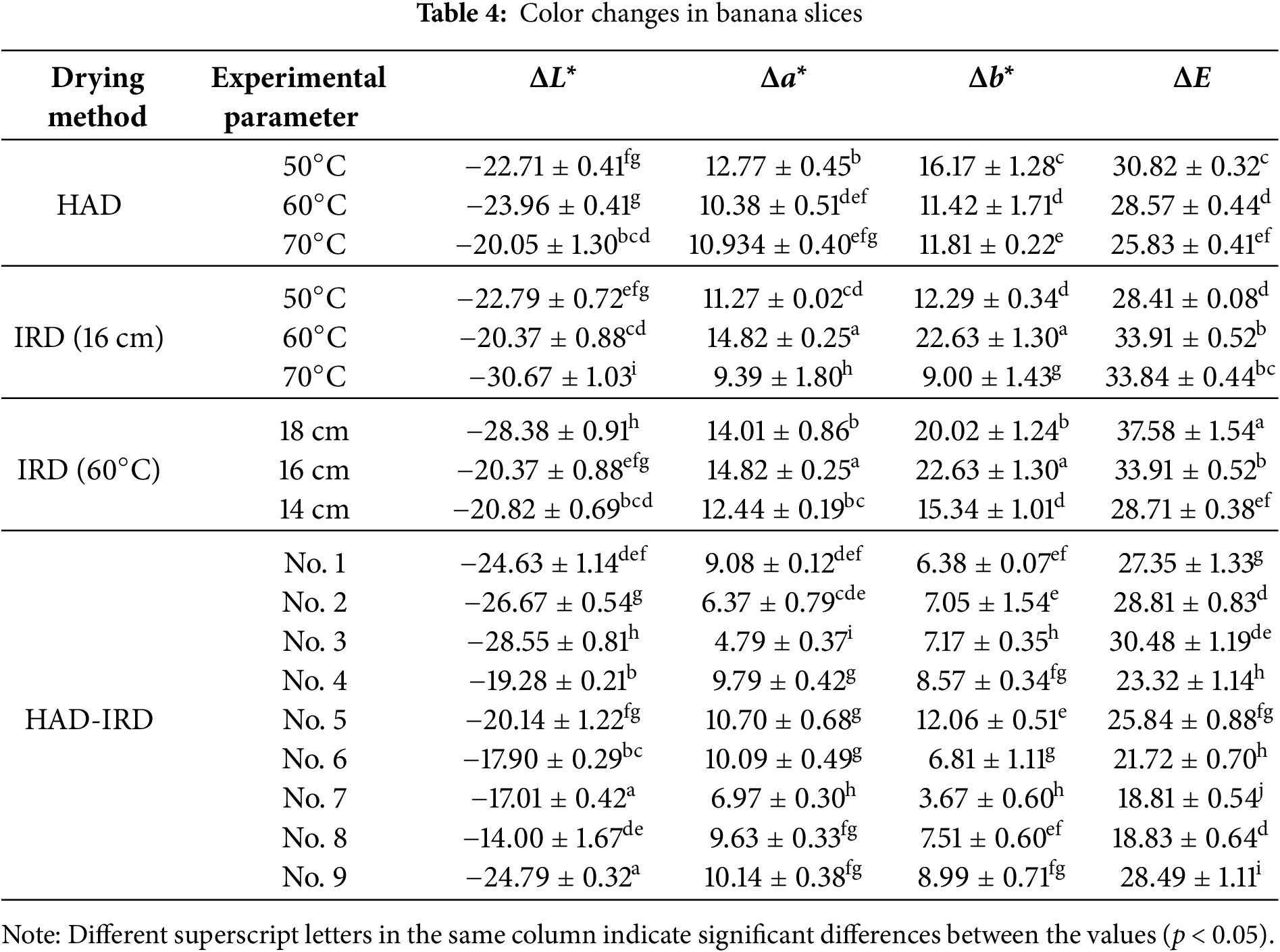

The color data of dried banana slices serve as a critical indicator within the product quality evaluation system, holding significant academic research value and industrial application importance. These parameters not only provide the most direct basis for assessing the product’s sensory quality but also objectively reflect the extent of physicochemical alterations occurring during the drying process. The color values of fresh banana slices were L* (60.2 ± 1.32), a* (2.65 ± 1.19), and b* (19.0 ± 1.6). As shown in Table 4, the ΔL* values for dried banana slices across different treatments were all negative, while the Δa* and Δb* values were positive. This indicates that the color of the banana slices darkened and developed a more pronounced yellow hue after drying. Notably, under specific HAD-IRD conditions—namely, A = 70°C, B = 50°C, C = 18 cm and A = 70°C, B = 60°C, C = 14 cm—the dried samples exhibited significantly smaller total color difference (ΔE) values of 18.813 and 18.833, respectively. This finding demonstrates that, compared to conventional HAD and IRD methods, the HAD-IRD combination exhibits superior performance in minimizing color changes induced by caramelization and Maillard reaction during drying.

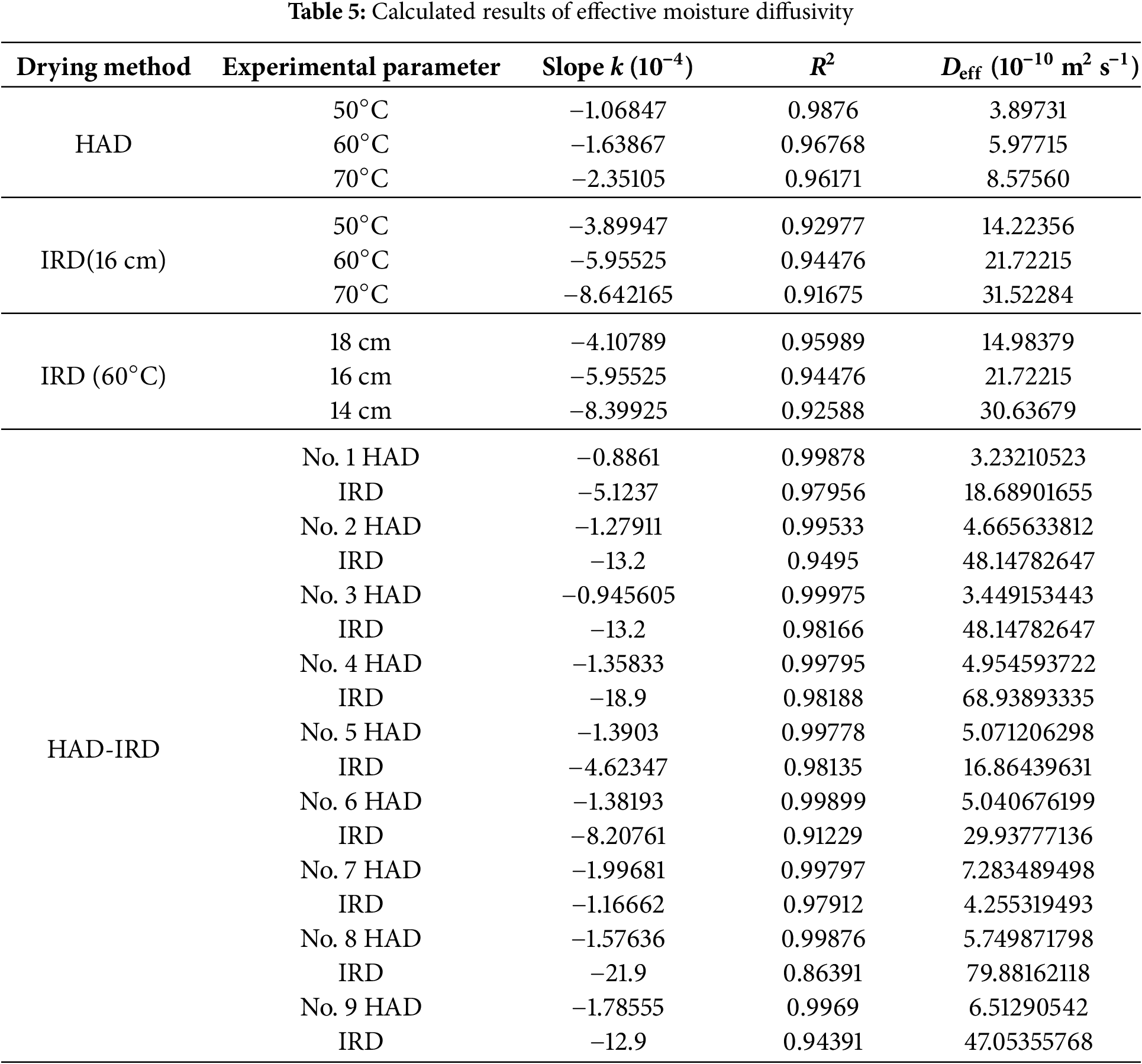

3.5 Effective Moisture Diffusivity

Table 5 shows the calculated results of effective moisture diffusivity (Deff). The results indicated that the Deff value increased with rising drying temperature. Under HAD conditions, the Deff value increased from 3.89731 × 10−10 m2/s at 50°C to 8.57560 × 10−10 m2/s at 70°C. At all tested temperatures, the Deff values under IRD were substantially higher than those under HAD, with the difference being particularly pronounced at elevated temperatures. This confirms that infrared radiation, by transferring energy directly into the material, shortens the heat transfer path and improves thermal efficiency. Consequently, IRD significantly enhances the internal moisture migration capability within the material, increases water molecule mobility, and accelerates the moisture diffusion process.

Furthermore, under the HAD-IRD combined drying regime, the subsequent introduction of IRD resulted in consistently higher effective moisture diffusivity (Deff) during the later stages. Notably, the Deff values observed in the combined drying process even surpassed those achieved by standalone IRD in certain cases. Specifically, two HAD-IRD parameter sets yielded relatively high Deff values: one with hot air temperature at 60°C, infrared temperature at 50°C, and radiation distance of 16 cm; and another with hot air temperature at 70°C, infrared temperature at 60°C, and radiation distance of 14 cm. This enhancement can be attributed to the penetrative heating mechanism of the subsequently applied infrared radiation, which more effectively facilitates the removal of internal moisture from the banana slices compared to conventional HAD alone. The synergistic effect suggests that the initial HAD stage creates favorable structural conditions that enable the subsequent IRD stage to achieve superior moisture diffusion performance.

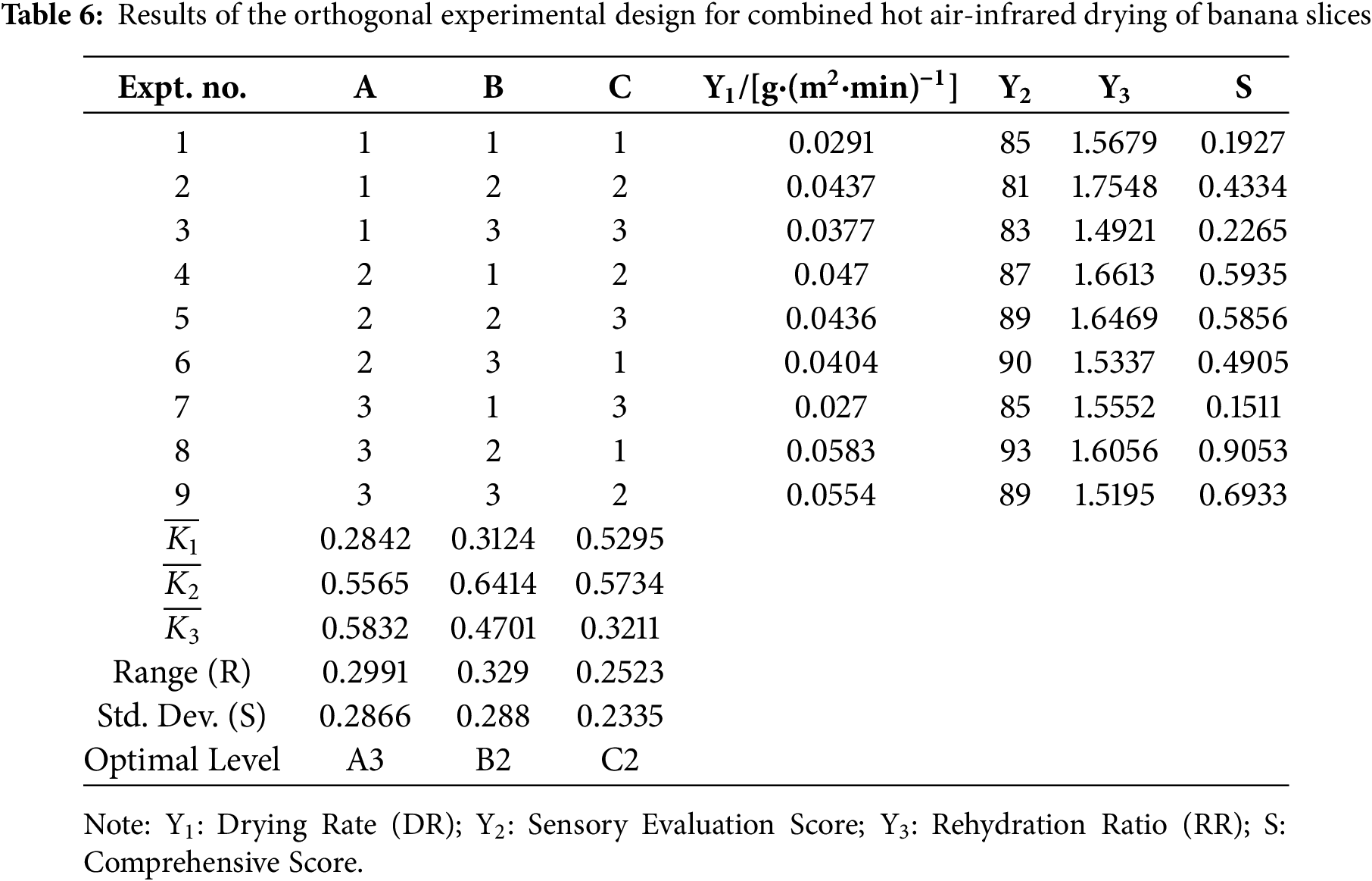

As can be observed from Table 6, combining hot air and infrared drying technologies for banana slices indeed improves the drying rate while better preserving the quality of the dried product. Furthermore, employing an orthogonal experimental design allowed for the optimization of the HAD-IRD process parameters from the three factors: hot air temperature, infrared temperature, and infrared radiation distance.

Analysis of the Range (R) and Standard Deviation values revealed the relative importance of the three factors on the combined drying outcome, yielding the order B > A > C, i.e., Infrared Temperature > Hot Air Temperature > Infrared Radiation Distance. The optimal combination derived from the orthogonal analysis was A3B2C2, corresponding to a hot air temperature of 70°C, an infrared temperature of 60°C, and an infrared radiation distance of 16 cm. The drying times required for all nine orthogonal trials under HAD-IRD were significantly shorter than those for HAD alone and were also very close to the times observed for IRD used independently. Furthermore, most samples from the orthogonal experimental groups demonstrated a superior rehydration ratio compared to those processed by any single drying method, with a particularly notable improvement over samples dried using high-temperature IRD alone. Regarding sensory evaluation, the orthogonal groups received consistently higher scores than those dried solely by HAD. While their scores were generally comparable to those achieved by single IRD, certain combinations—specifically, Trial 8—achieved marginally higher sensory ratings.

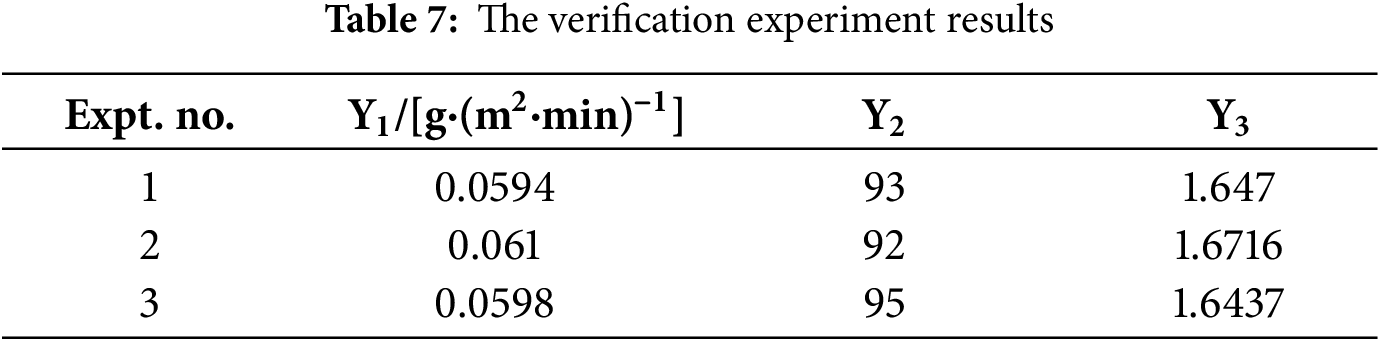

Verification experiments were designed and conducted, comprising three replicate trials under the theoretically optimal parameters (HAD at 70°C, IRD at 60°C, and a radiation distance of 16 cm). The banana slices were dried to the target moisture content, during which the relevant data were recorded. The obtained dried banana slices were subsequently evaluated for sensory score and rehydration ratio. The results are presented in Table 7.

The results of the verification experiments were highly satisfactory. Therefore, it can be concluded that the optimized HAD-IRD process parameters identified in this study—namely, a hot air temperature of 70°C, an infrared temperature of 60°C, and an infrared radiation distance of 16 cm—are effective and valid. This optimized protocol warrants further investigation by relevant researchers and facilitates the progression of this combined drying technique towards industrial application.

This study systematically evaluated the drying characteristics, quality attributes, and efficiency of Hot Air Drying (HAD), Infrared Drying (IRD), and a novel Hot Air-Infrared Combined Drying (HAD-IRD) strategy for banana slices. The key findings and implications are summarized as follows:

(1) Mechanistic Insights into Single Drying Methods: Conventional HAD exhibits a characteristic drying profile, predominantly marked by a distinct falling rate period with no clearly defined constant rate phase. While elevated temperatures can enhance the drying rate to some extent, they fail to alleviate the intrinsic diffusion limitations in the later stages and often lead to product quality degradation. In contrast, IRD utilizes volumetric heating for rapid moisture removal, significantly reducing drying time. However, the absence of convective surface moisture removal disrupts the kinetic balance, increasing the risk of case-hardening and inconsistent product quality.

(2) Synergistic Effect of Combined Drying: The proposed HAD-IRD strategy successfully integrates the advantages of both techniques. The initial HAD stage efficiently removes a substantial amount of free surface moisture via convection, preparing the matrix for subsequent drying. The follow-up IRD stage then effectively drives out the internally bound water through penetrating radiation. This synergistic sequence not only shortens the total drying time by over 70% compared to HAD alone but also circumvents the quality control challenges associated with single IRD, resulting in products with superior color, texture, and rehydration capacity.

(3) Process Optimization and Validation: Through a structured L9(33) orthogonal experimental design, the critical process parameters for HAD-IRD were successfully optimized. The factor significance was determined as Infrared Temperature > Hot Air Temperature > Radiation Distance. The optimal combination was identified as HAD at 70°C, followed by IRD at 60°C with a radiation distance of 16 cm. The high reproducibility and excellent performance metrics (drying rate, sensory score, rehydration ratio) obtained from the verification experiments confirm the robustness and practical viability of this optimized protocol.

(4) Broader Implications and Future Outlook: This work demonstrates that a phase-separated combined drying approach is a highly effective strategy for thermosensitive biological materials like bananas. It provides a viable pathway to reconcile the often-conflicting objectives of process efficiency and end-product quality in industrial drying operations. Future research could focus on the scale-up of this combined process, conduct a detailed life-cycle assessment for energy consumption and environmental impact, and explore its application to other challenging fruits and vegetables to further validate its universality and economic benefits.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the financial support for the work by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Changsha Municipal Nature Science Foundation, and Regional Joint Funds of Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52306124 (received by Dan Huang), URL: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/HHNYjgYKAynqYR7ySxYwzQ (accessed on 01 January 2025); the Changsha Municipal Natural Science Foundation, grant number kq2402259 (received by Shuai Huang), URL: http://kjj.changsha.gov.cn/zfxxgk/tzgg_27202/202501/t20250122_11726939.html (accessed on 01 January 2025); and the Regional Joint Funds of the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, grant number 2025JJ70463 (received by Shuai Huang), URL: https://kjt.hunan.gov.cn/kjt/xxgk/tzgg/tzgg_1/202502/t20250212_33585991.html (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Author Contributions: The author confirms the following contributions to the paper: Study conception and design: Guofeng Han; Data collection: Chenxi Luo, Xin Liu; Result analysis and interpretation: Guofeng Han, Chenxi Luo, Dan Huang; Manuscript preparation: Yuling Cheng, Yuanyuan Li, Shuai Huang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the results of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author Dan Huang upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mostafa HS. Banana plant as a source of valuable antimicrobial compounds and its current applications in the food sector. J Food Sci. 2021;86(9):3778–97. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.15854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Borges CV, Maraschin M, Coelho DS, Leonel M, Gomez HAG, Belin MAF, et al. Nutritional value and antioxidant compounds during the ripening and after domestic cooking of bananas and plantains. Food Res Int. 2020;132(11):109061. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Martínez S, Roman-Chipantiza A, Boubertakh A, Carballo J. Banana drying: a review on methods and advances. Food Rev Int. 2024;40(8):2188–226. doi:10.1080/87559129.2023.2262030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ding JX, Wu XH, Wang P, Yang XF. Overview of the application of drying technology in fruits and vegetables. Refrig Air-Cond. 2019;19(8):29–33+64. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

5. Ali Nawaz Ranjha MM, Irfan S, Nadeem M, Mahmood S. A comprehensive review on nutritional value, medicinal uses, and processing of banana. Food Rev Int. 2022;38(2):199–225. doi:10.1080/87559129.2020.1725890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen C, Khir R, Shen Y, Wu X, Zhang R, Cao X, et al. Energy consumption and product quality of off-ground harvested almonds under hot air column drying. LWT. 2021;138(6):110768. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Karim N, Shishir MRI, Bao T, Chen W. Effect of cold plasma pretreated hot-air drying on the physicochemical characteristics, nutritional values and antioxidant activity of shiitake mushroom. J Sci Food Agric. 2021;101(15):6271–80. doi:10.1002/jsfa.11296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Kumar Y, Singh L, Sharanagat VS, Mani S, Kumar S, Kumar A. Quality attributes of convective hot air dried spine gourd (Momordica dioica Roxb. Ex Willd) slices. Food Chem. 2021;347(1):129041. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang D, Ji H, Liu S, Gao J. Similarity of aroma attributes in hot-air-dried shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) and its different parts using sensory analysis and GC-MS. Food Res Int. 2020;137:109517. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Farias RP, Gomez RS, Silva WP, Silva LPL, Oliveira Neto GL, Santos IB, et al. Heat and mass transfer, and volume variations in banana slices during convective hot air drying: an experimental analysis. Agriculture. 2020;10(10):423. doi:10.3390/agriculture10100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Shi X, Yang Y, Li Z, Wang X, Liu Y. Moisture transfer and microstructure change of banana slices during contact ultrasound strengthened far-infrared radiation drying. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2020;66(12):102537. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Natarajan SK, Elangovan E, Elavarasan RM, Balaraman A, Sundaram S. Review on solar dryers for drying fish, fruits, and vegetables. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(27):40478–506. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-19714-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Salehi F. Recent progress and application of freeze dryers for agricultural product drying. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023;10(5):618–27. doi:10.1002/cben.202300003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhu Z, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Wu X, Liu J, Shi Q, et al. Effects of ultrasound pretreatment on the drying kinetics, water status and distribution in scallop adductors during heat pump drying. J Sci Food Agric. 2021;101(15):6239–47. doi:10.1002/jsfa.11290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. de Souza JVB, Perazzini H, Lima-Corrêa RAB, Borel LDMS. Combined infrared-convective drying of banana: energy and quality considerations. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2024;48:102393. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2024.102393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang H, Liu Y, Gao L, Meng ZF, Yu ZY, Wang FX, et al. Effects of high-voltage electric field on hot-air drying characteristics and mathematical model of banana slices. Food Sci Technol. 2020;45(7):69–75. (In Chinese). doi:10.13684/j.cnki.spkj.2020.07.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Madhankumar S, Viswanathan K, Taipabu MI. Experimental investigation of indirect solar dryer with integration of copper thin fins and paraffin wax as thermal energy storage. Appl Therm Eng. 2025;275:126771. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2025.126771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shi X, Liu Y, Li Z, Sun X, Li X. Effects of radiation temperature on dehydration and moisture migration in banana slices during far-infrared radiation drying. J Food Process Preserv. 2020;44(11):e14901. doi:10.1111/jfpp.14901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Khampakool A, Soisungwan S, Park SH. Potential application of infrared assisted freeze drying (IRAFD) for banana snacks: drying kinetics, energy consumption, and texture. LWT. 2019;99(2):355–63. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2018.09.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Salehi F. Recent applications and potential of infrared dryer systems for drying various agricultural products: a review. Int J Fruit Sci. 2020;20(3):586–602. doi:10.1080/15538362.2019.1616243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Tao YL, Li MY, Li MQ, Zhang XT, Zhu LC, Che X, et al. Research status of infrared drying in the field of fruit and vegetable drying. Food Ferment Ind. 2025;51(21):435–46. (In Chinese). doi:10.13995/j.cnki.11-1802/ts.041938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tabtiang S, Yodrux A, Nimmol C, Soponronnarit S. Application of combined hot air drying and infrared radiation coupled with hot air puffing for banana crisp production. Dry Technol. 2025;43(8):1259–72. doi:10.1080/07373937.2025.2516127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chang AT. Kinetics and process parameters optimization of combined infraredand hot air drying of cantaloupe (Cucumis melon L.) slices [master’s thesis]. Shihezi, China: Shihezi University; 2022. (In Chinese). doi:10.27332/d.cnki.gshzu.2022.000107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Qi HP, Hu WZ, Jiang AL, Tian MX. Study on the hot-air drying processing technology of banana slices. Hubei Agric Sci. 2011;50(14):2936–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.14088/j.cnki.issn0439-8114.2011.14.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Gong GF, Li Y. Research on banana drying by hot air and vacuum microwave combination. Food Ferment Ind. 2016;42(11):138–41. (In Chinese). doi:10.13995/j.cnki.11-1802/ts.201611024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang B, Hou XZ. Study on banana slice drying process by combining hot air and microwave. Food Mach. 2010;26(2):97–9,142. (In Chinese). doi:10.13652/j.issn.1003-5788.2010.02.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wu PY, Tang FN, Pei J. Application of orthogonal experimental design method in process scheme design. Ordnance Ind Autom. 2024;43(5):20–3. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

28. Ding C, Liu Q, Tao TT, Tu K, Yang GF. Analysis moisture diffusion characteristics of paddy drying parameters based Logarithmic model equation. Sci Technol Food Ind. 2015;36(23):53–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2015.23.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Mbegbu NN, Nwajinka CO, Amaefule DO. Thin layer drying models and characteristics of scent leaves (Ocimum gratissimum) and lemon basil leaves (Ocimum africanum). Heliyon. 2021;7(1):e05945. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen X, Zhang XC, Wang ZX, He XM, Sun J. Effects of different processing methods on the quality of banana slices. J South Agric. 2022;53(5):1305–15. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.2095-1191.2022.05.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wei S, Chen P, Xie W, Wang F, Yang D. Prediction of stress cracks in corn kernels drying based on three-dimensional heat and mass transfer. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng. 2019;35(23):296–304. doi:10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2019.23.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. de Farias RP, Sousa Santos R, Soares Gomes R, da Silva WP, de Almeida Barbalho GH, de Melo Cavalcante AM, et al. Drying of banana slices in cylindrical shape: theoretical and experimental investigations. Defect Diffus Forum. 2020;399(4):183–9. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/ddf.399.183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Farias RP, Gomez RS, Lima ES, Silva WP, Santos IB, Figueredo MJ, et al. Geometric and thermo-gravimetric evaluation of bananas during convective drying: an experimental investigation. Agriculture. 2022;12(8):1181. doi:10.3390/agriculture12081181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang C, Kou X, Zhou X, Li R, Wang S. Effects of layer arrangement on heating uniformity and product quality after hot air assisted radio frequency drying of carrot. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2021;69(8):102667. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2021.102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rahman MH, Ahmed MW, Islam MN. Drying kinetics and sorption behavior of two varieties banana (sagor and sabri) of Bangladesh. SAARC J Agric. 2019;16(2):181–93. doi:10.3329/sja.v16i2.40269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. De Souza LF, De Andrade ET, De Almeida Rios P. Determination of volumetric contraction and drying kinetics of the dryed banana. Theor Appl Eng. 2019;3(1):20–30. doi:10.31422/taae.v2i4.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kumar PS, Nambi E, Shiva KN, Vaganan MM, Ravi I, Jeyabaskaran KJ, et al. Thin layer drying kinetics of Banana var. Monthan (ABBinfluence of convective drying on nutritional quality, microstructure, thermal properties, color, and sensory characteristics. J Food Process Eng. 2019;42(4):e13020. doi:10.1111/jfpe.13020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Skåra T, Løvdal T, Skipnes D, Nwabisa Mehlomakulu N, Mapengo CR, Otema Baah R, et al. Drying of vegetable and root crops by solar, infrared, microwave, and radio frequency as energy efficient methods: a review. Food Rev Int. 2023;39(9):7197–217. doi:10.1080/87559129.2022.2148688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Liu ZL, Xie L, Zielinska M, Pan Z, Deng LZ, Zhang JS, et al. Improvement of drying efficiency and quality attributes of blueberries using innovative far-infrared radiation heating assisted pulsed vacuum drying (FIR-PVD). Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2022;77(8):102948. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2022.102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang J, Zheng X, Xiao H, Shan C, Li Y, Yang T. Quality and process optimization of infrared combined hot air drying of yam slices based on BP neural network and gray wolf algorithm. Foods. 2024;13(3):434. doi:10.3390/foods13030434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Mishra S, Parth K, Balavignesh V, Sharma A, Kumar N, Kaur E. A study on the dehydration of fruits using novel drying techniques. Pharm Innov J. 2022;11:1071–80. [Google Scholar]

42. Kılıç F. Effects of three drying methods on kinetics and energy consumption of carrot drying process and modeling with artificial neural networks. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util Environ Eff. 2021;43(12):1468–85. doi:10.1080/15567036.2020.1832163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ma L, Cheng S, Shi Y. Enhancing learning efficiency of brain storm optimization via orthogonal learning design. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern Syst. 2021;51(11):6723–42. doi:10.1109/TSMC.2020.2963943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools