Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Natural Language Processing with Transformer-Based Models: A Meta-Analysis

School of Computing and Information Technology, Murang’a University of Technology, Murang’a, 75-10200, Kenya

* Corresponding Author: Charles Munyao. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 329-346. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.069226

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 14 August 2025; Issue published 22 September 2025

Abstract

The natural language processing (NLP) domain has witnessed significant advancements with the emergence of transformer-based models, which have reshaped the text understanding and generation landscape. While their capabilities are well recognized, there remains a limited systematic synthesis of how these models perform across tasks, scale efficiently, adapt to domains, and address ethical challenges. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to analyze the performance of transformer-based models across various NLP tasks, their scalability, domain adaptation, and the ethical implications of such models. This meta-analysis paper synthesizes findings from 25 peer-reviewed studies on NLP transformer-based models, adhering to the PRISMA framework. Relevant papers were sourced from electronic databases, including IEEE Xplore, Springer, ACM Digital Library, Elsevier, PubMed, and Google Scholar. The findings highlight the superior performance of transformers over conventional approaches, attributed to self-attention mechanisms and pre-trained language representations. Despite these advantages, challenges such as high computational costs, data bias, and hallucination persist. The study provides new perspectives by underscoring the necessity for future research to optimize transformer architectures for efficiency, address ethical AI concerns, and enhance generalization across languages. This paper contributes valuable insights into the current trends, limitations, and potential improvements in transformer-based models for NLP.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe evolution of Natural Language Processing (NLP) has been marked by a series of groundbreaking innovations, none more transformative than the advent of transformer architectures. Introduced by Vaswani et al. in 2017, transformers revolutionized the field by addressing the limitations of traditional models such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) [1]. These conventional models, including RNNs and LSTMs, faced challenges such as difficulty capturing long-range dependencies due to vanishing gradient issues and inefficiencies in parallelizing computations, limiting their scalability and performance in handling complex language tasks [2]. Unlike their predecessors, which relied on sequential data processing, transformers utilize self-attention mechanisms to capture global dependencies within text data, enabling parallel processing of input sequences. This breakthrough has unlocked unprecedented capabilities in language understanding, making Transformers the cornerstone of modern NLP applications.

One of the defining characteristics of Transformer architectures is their scalability. As demonstrated by models like BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) and GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), the self-attention mechanism allows for the efficient handling of large datasets and complex linguistic structures [2,3]. This scalability has facilitated significant advancements in diverse NLP tasks, including machine translation, text summarization, sentiment analysis, and question-answering. The ability to pre-train these models on massive corpora and fine-tune them for specific tasks has further amplified their impact, reducing the need for extensive task-specific training data [4]. The versatility of transformers extends beyond traditional NLP tasks. Recent advancements have seen the integration of transformer architectures into multimodal systems, enabling applications that combine textual, visual, and auditory data [5]. For example, models like DALL-E and CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pretraining) have demonstrated the potential of transformers to bridge the gap between language and vision, paving the way for innovative applications in fields such as content generation and virtual reality [5]. These developments underscore the transformative potential of transformers as a unifying framework for AI research.

Transformer-based models like Google Translate provide high-quality translations across diverse languages in machine translation. For text summarization, T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) and BART (Bidirectional and Auto-Regressive Transformer) enable efficient extraction of key information from large documents [5]. Question-answering systems like those integrated into virtual assistants like Alexa, Siri, and Google Assistant rely on transformers for accurate, context-aware responses. They are pivotal in sentiment analysis, allowing businesses to assess public opinion from social media and customer reviews. Additionally, transformers enhance search engines with context-aware information retrieval, power chatbots, and conversational AI for customer support, and they enable sophisticated tasks like text generation in content creation platforms [6]. Transformers also contribute to named entity recognition, enabling tasks such as identifying critical entities in legal and medical texts.

However, the rise of transformer-based models has not been without challenges. The high computational and memory requirements associated with these architectures have posed barriers to their adoption, particularly for researchers and organizations with limited resources. Furthermore, the reliance on large-scale pretraining datasets has raised ethical concerns, as biases inherent in these datasets are often propagated to model outputs [5]. Despite these challenges, as noted in [6], researchers have continued to refine transformer models, exploring techniques such as model compression, efficient training algorithms, and fairness-aware methodologies to mitigate their limitations.

Several review studies have explored the application of transformer models in NLP, such as [7], which focused primarily on audio-based tasks, and others, such as [5], that provided general surveys without a structured synthesis of empirical evidence across tasks. However, these reviews lack methodological transparency, fail to follow standardized frameworks like PRISMA, or do not cover emerging challenges such as data bias, hallucination, and computational complexity in depth. This paper differentiates itself by conducting a PRISMA-guided meta-analysis that not only benchmarks transformer performance across key NLP tasks but also critically examines scalability, domain adaptation, and ethical considerations, thus providing a more comprehensive and evidence-based perspective by synthesizing insights from key studies published between 2017 and 2025.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a theoretical review of transformers and their evolution. Section 3 outlines the methodology used to select and analyze relevant studies. Section 4 presents the key findings from the analyzed studies, with Section 5 offering a discussion. Finally, Section 6 provides conclusions and potential future research directions.

2 Theoretical Review of Transformers in NLP

The rapid evolution of NLP has been driven by continuous advancements in neural network architectures, with transformers playing a central role in reshaping the landscape. These models have been utilized in various NLP applications and spurred new research directions in areas such as zero-shot learning, few-shot adaptation, and multimodal processing. The following subsections focus on the foundational developments, key paradigms, and emerging trends in transformer-based NLP research.

2.1 Early Innovations in Language Modeling

The evolution of natural language processing (NLP) has been punctuated by several transformative innovations, with the introduction of Transformer architectures marking a critical inflection point. Traditional sequence-based models such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) have been the backbone of NLP tasks for years, primarily due to their ability to handle sequential data [8]. However, these models faced significant challenges in capturing long-range dependencies and parallelizing computations. The groundbreaking work by Vaswani et al. [1], introducing the transformer architecture in 2017, addressed these limitations by replacing recurrence with self-attention mechanisms. This innovation facilitated the modeling of global dependencies within input sequences, enabling significant improvements in language representation. Subsequent studies expanded on these foundations, demonstrating the transformer’s versatility across various applications. Researchers such as Radford et al. and Devlin et al. leveraged the transformer architecture to pretrain large-scale language models that could generalize across multiple NLP tasks [9,10]. The bidirectional nature of BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) and the autoregressive capabilities of GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) underscored the adaptability of this architecture [4]. These innovations enhanced model performance and established the paradigm of pretraining and fine-tuning, which remains a cornerstone of modern NLP research.

2.2 Pretraining and Fine-Tuning Paradigm

The pretraining and fine-tuning paradigm has been central to the success of Transformer-based models. Through pretraining on massive datasets, models such as BERT, GPT, and T5 were able to capture rich contextual embeddings, significantly reducing the need for task-specific labeled data [9,10]. This paradigm democratized access to state-of-the-art NLP capabilities, enabling researchers and practitioners to adapt pre-trained models to diverse applications with minimal computational resources. Benchmark studies further validated the effectiveness of pre-trained models. For instance, BERT set new standards on tasks within the General Language Understanding Evaluation (GLUE) benchmark [5], while T5 unified a variety of NLP tasks under the text-to-text framework, achieving state-of-the-art results across multiple datasets [9]. The success of these models catalyzed a wave of research into scaling Transformer architectures, as evidenced by the development of models such as GPT-3, which utilized 175 billion parameters to achieve few-shot learning capabilities.

2.3 Specialized Adaptations and Applications

In addition to general-purpose language models, the transformer architecture has been adapted for specialized domains. Domain-specific models such as BioBERT and ClinicalBERT exemplify the application of Transformer-based approaches to biomedical text, addressing challenges in extracting meaningful insights from clinical narratives and research publications [6]. Similarly, LegalBERT has tailored the architecture for legal texts, improving performance in contract analysis and legal document classification [4]. Transformer models have also found utility in low-resource languages and domains. Models like mBERT and XLM-R have demonstrated the capacity to generalize across languages with limited labeled data by leveraging multilingual training datasets [10]. These efforts underscore the versatility of Transformer architectures, which can be fine-tuned to address unique linguistic and domain-specific challenges while maintaining high performance.

2.4 Challenges in Transformer-Based Models

Despite their transformative potential, Transformer-based models are not without limitations. The high computational costs associated with pretraining and fine-tuning have been a consistent barrier, particularly for resource-constrained researchers and organizations [2,3]. Studies have highlighted the environmental impact of training large models, with significant energy consumption contributing to carbon emissions. Efforts to mitigate these challenges have included the development of more efficient architectures, such as ALBERT (A Lite BERT) and DistilBERT, which achieve comparable performance with reduced computational requirements [10]. Broader surveys have highlighted key trends and persistent challenges in NLP research, including scalability, ethical issues, and generalization [11]. Another significant challenge lies in addressing the biases inherent in large-scale pretraining datasets. Language models often amplify societal biases in their training data, leading to ethical concerns in their deployment, whereby researchers in [12] have proposed fairness-aware training methodologies and dataset curation strategies to address these issues, but achieving accurate equity in NLP remains an ongoing challenge.

2.5 Emerging Trends and Directions

Recent advancements have explored the integration of transformer architectures with multimodal systems. For instance, models such as CLIP and DALL-E have demonstrated the feasibility of combining textual and visual representations within a unified framework [13]. These developments have opened new avenues for applications in content creation, virtual reality, and human-computer interaction. Hybrid architectures that incorporate domain-specific knowledge have also emerged as a promising direction. Researchers aim to enhance the interpretability and robustness of transformer-based models by integrating external knowledge graphs and symbolic reasoning. Additionally, as per [13], ongoing work in federated learning and decentralized training seeks to address privacy concerns associated with large-scale language models, enabling secure and efficient training in distributed environments. Complementing these efforts are recent innovations in architectural efficiency, including sparse attention mechanisms in the Longformer and the BigBird models that reduce computational overhead in long-sequence tasks, and Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models such as GShard and the Switch Transformer, which dynamically activate model subsets to scale performance while minimizing resource use [14,15]. These directions represent a growing emphasis on making transformer models both scalable and accessible.

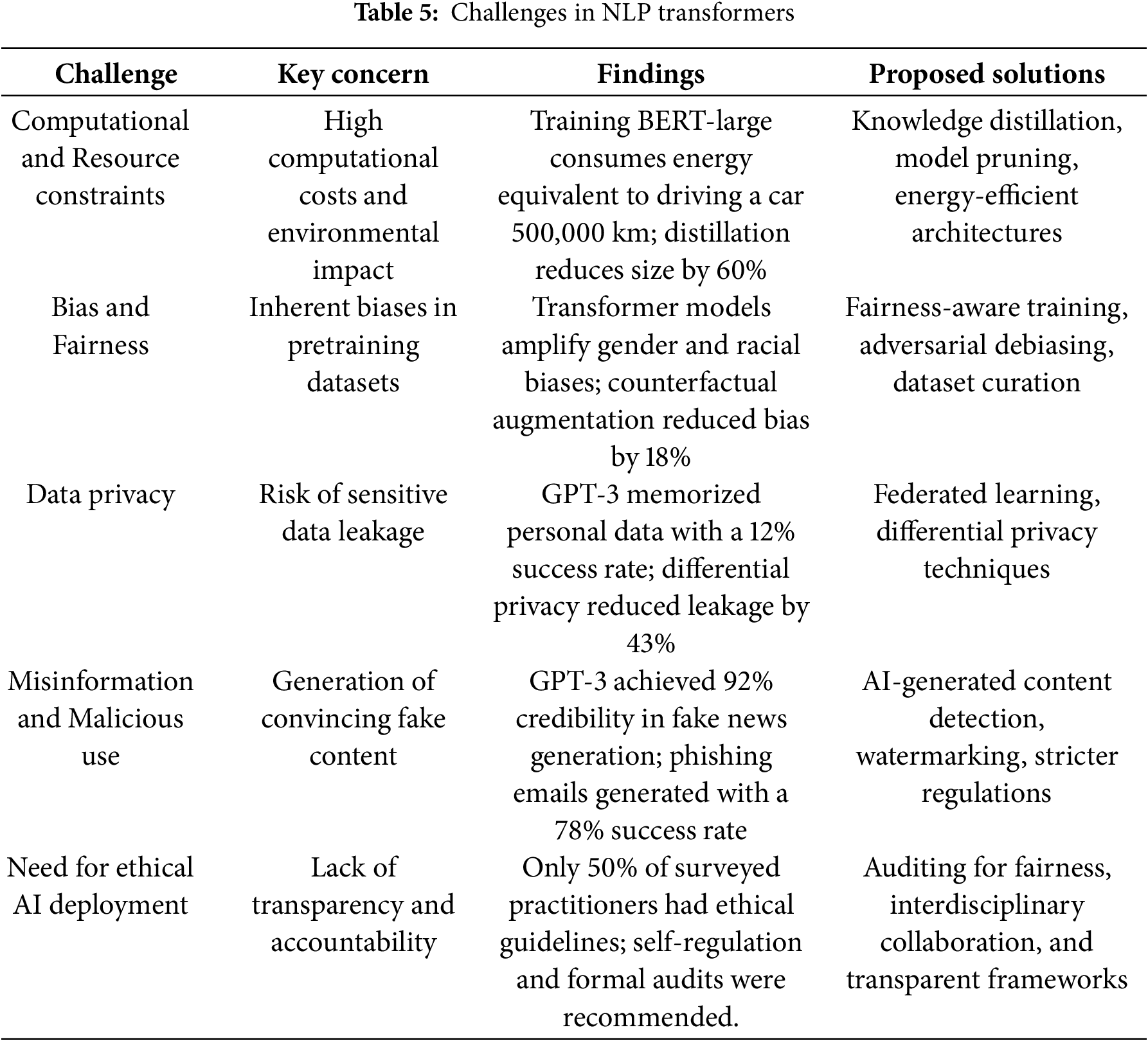

This study followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines to ensure a systematic and transparent approach to synthesizing relevant literature. The PRISMA framework was chosen for its robustness in structuring systematic reviews and its emphasis on transparency in reporting, making it particularly suitable for this study. The methodology for this study was therefore designed to ensure a systematic, transparent, and replicable process in synthesizing existing literature on transformer-based models in NLP while adhering to established guidelines and leveraging existing meta-analysis frameworks. This methodology consists of several sequential stages: defining the research questions, developing eligibility criteria, conducting a comprehensive search, selecting studies, extracting data, assessing quality, and synthesizing findings.

3.1 Research Objectives and Scope

The primary objective of this meta-analysis was to explore and synthesize findings related to the development, application, and challenges of Transformer-based language models in NLP. Research questions were formulated to address the performance, scalability, domain adaptation, and ethical concerns. The research questions were as follows:

1. How do transformer-based models perform across various natural language processing tasks?

2. What are the scalability and domain adaptation capabilities of transformer-based models in NLP applications?

3. What are the key challenges and ethical considerations in developing and applying transformer-based models for NLP tasks?

To ensure clarity in scope, the analysis centered on studies published between 2017 (the year of the Transformer’s introduction) and 2025. Both peer-reviewed journal articles and high-quality conference proceedings were included. Preprints were considered only if they had received significant citations or endorsements from the research community. This approach ensured a balance between comprehensiveness and relevance.

Eligibility criteria were clearly defined to ensure the relevance and quality of the included studies. Inclusion criteria included (1) studies that involve transformer-based models, (2) studies reporting empirical results on NLP tasks using transformers, and (3) studies providing sufficient methodological details for replication or meta-analysis. Exclusion criteria included (1) studies focusing solely on theoretical aspects without empirical validation, (2) studies involving iterations or variations of architectures or models, and (3) non-English publications or studies with incomplete data. A quality threshold was also applied using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale to exclude studies with methodological ambiguities or insufficient rigor.

The literature search was conducted systematically across multiple electronic databases, including Springer, Elsevier, PubMed, IEEE Xplore, ACM Digital Library, and Google Scholar. Search terms were selected to encompass various aspects of Transformer research, such as “Transformer NLP,” “Transformer scalability,” “domain adaptation in Transformers,” and “ethical considerations in NLP models.” Boolean operators were employed to refine the queries and maximize the retrieval of relevant articles. The search was supplemented by manually screening the reference lists of included articles to identify additional studies. Grey literature, including technical reports and unpublished dissertations, was also reviewed to capture less formal but potentially valuable contributions. The search concluded with the retrieval of 136 papers, which were subsequently filtered for relevance.

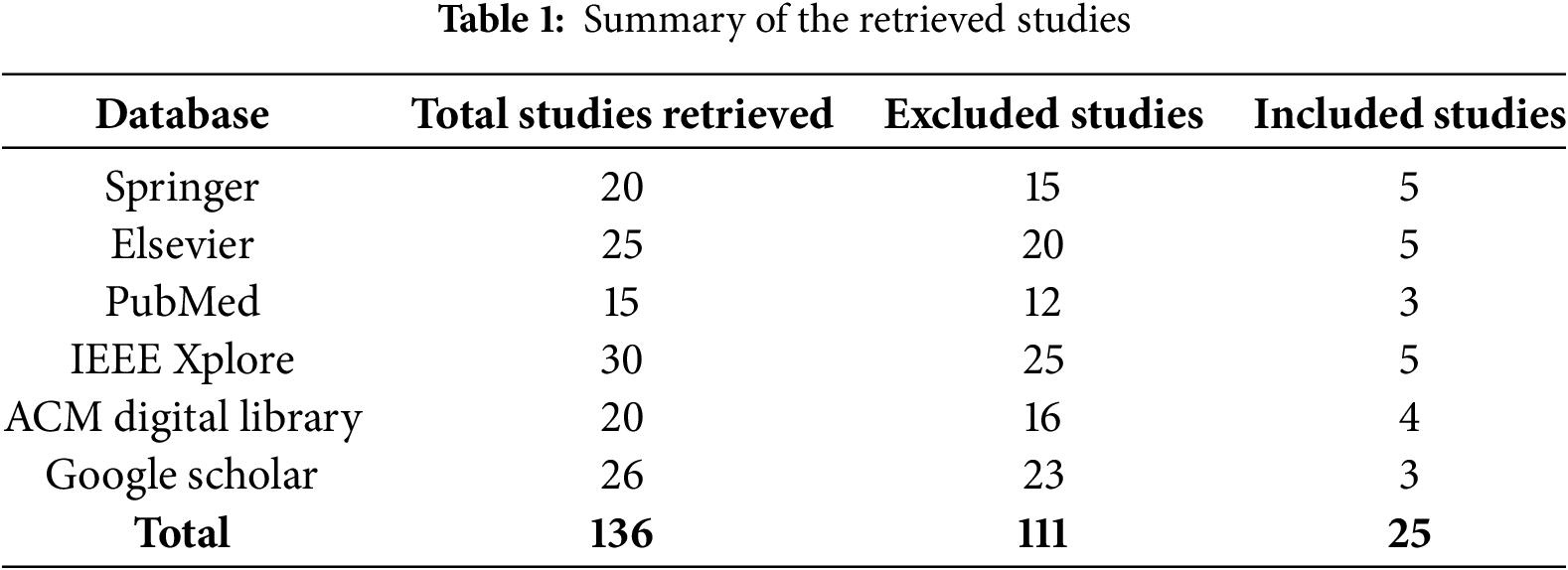

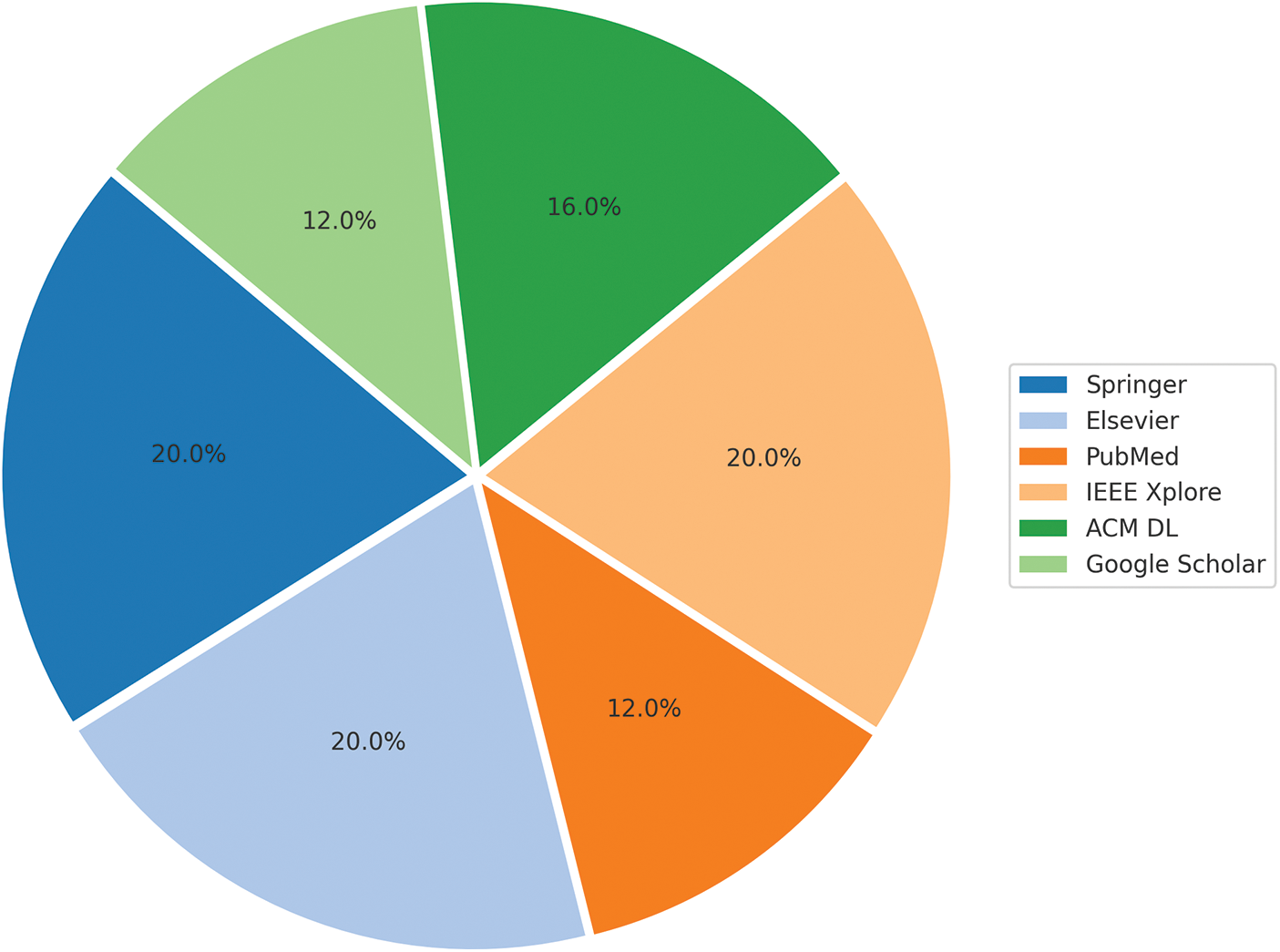

Study selection followed a two-stage process. In the first stage, titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion criteria to exclude irrelevant studies. This process was conducted systematically to reduce the risk of bias, with careful attention to the predefined inclusion criteria. Any uncertainties or ambiguous cases were resolved through further scrutiny of the full text and by cross-referencing related studies to ensure alignment with the scope of the meta-analysis. The second stage involved a full-text review of the remaining articles to ensure they met all eligibility criteria. A standardized form was used to document decisions at each stage, and the reasons for excluding studies were recorded to enhance transparency. After this process, 25 studies were deemed eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis, as shown in Table 1.

To enhance the clarity of the retrieval results, the pie chart in Fig. 1 below presents a visual summary of the number of included studies by source database, corresponding to the data in Table 1.

Figure 1: Summary of the included studies

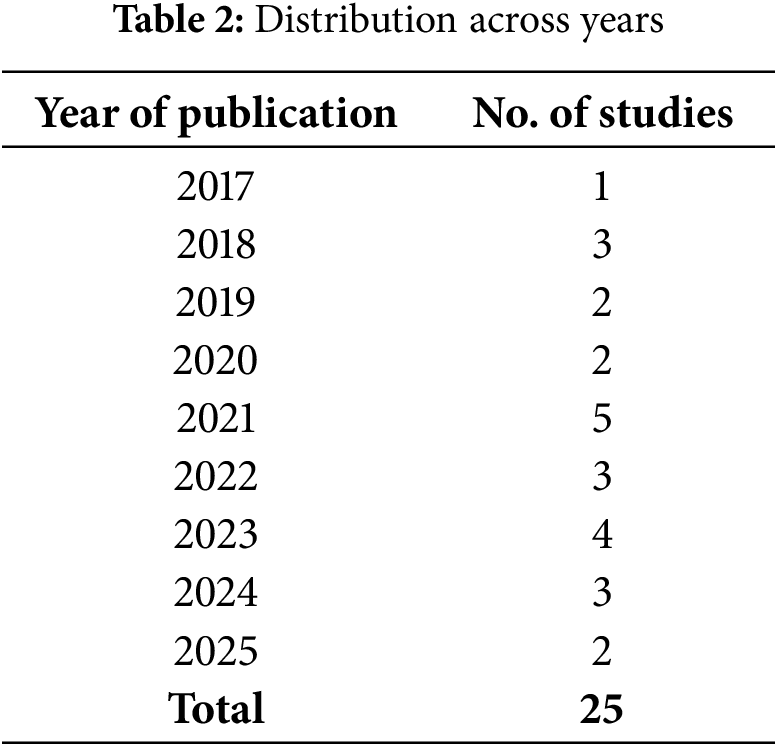

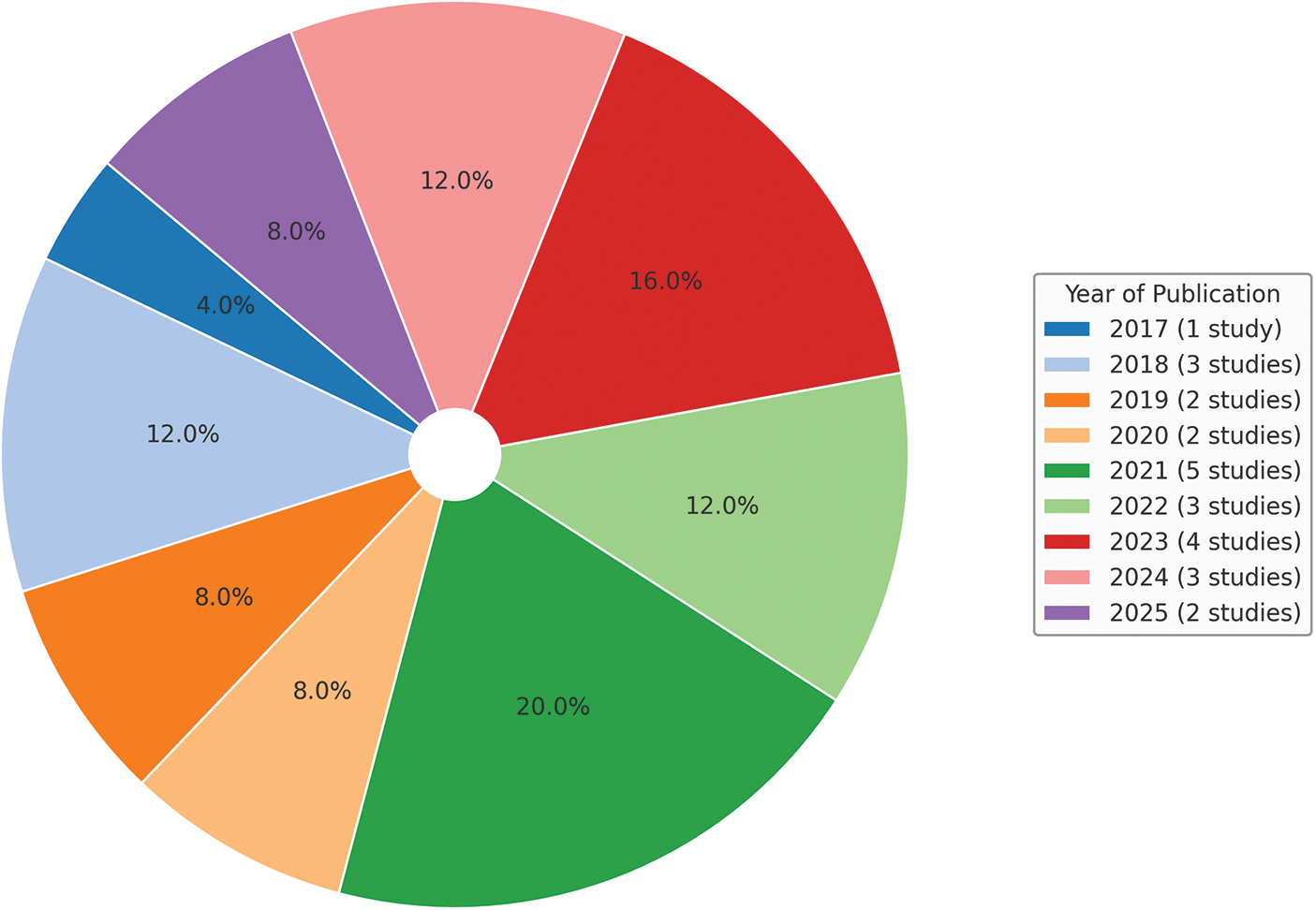

Table 2 categorizes the included papers based on their year of publication, highlighting the progressive growth in research activity on transformer-based models in NLP.

The following pie chart in Fig. 2 visually complements Table 2 by illustrating the distribution of the included studies across publication years.

Figure 2: Distribution across years

The diagram in Fig. 3 shows the flowchart of the PRISMA methodology.

Figure 3: PRISMA flowchart

Data extraction was done using a pre-designed template to ensure consistency and standardization across all selected studies. The template was structured to capture key details such as model architecture, dataset characteristics, evaluation metrics, task-specific performance, computational costs, and reported challenges. The most relevant and representative results were prioritized for studies presenting multiple experiments or configurations, focusing on those aligned closely with the research objectives. Ambiguities in the reported data were addressed by cross-referencing related studies and supplemental materials, ensuring the reliability and comprehensiveness of the extracted information. This systematic approach facilitated the accurate organization and comparison of data, laying a solid foundation for meaningful synthesis and analysis.

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, adapted for computational research [16]. This tool evaluated studies based on criteria such as methodological rigor, transparency in reporting, and reproducibility. Studies scoring below a predefined threshold were excluded from the analysis to maintain the integrity of the findings. Where applicable, publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger’s test. This step ensured that the results were not unduly influenced by selective reporting or other forms of bias.

A mixed-methods approach was adopted for data synthesis, combining quantitative and qualitative techniques. Quantitative data were synthesized through meta-analytic techniques, calculating pooled effect sizes and confidence intervals where sufficient homogeneity existed. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic, and subgroup analyses were conducted to explore variations across different model types, tasks, and domains. Qualitative data were synthesized using thematic analysis, identifying recurring patterns and themes across studies. This approach provided a subtle understanding of the challenges and trends in transformer research, complementing the quantitative findings.

The meta-analysis followed ethical guidelines, including the responsible use of data and acknowledging all original authors. The findings were reported with transparency and precision, avoiding overgeneralizations or unwarranted extrapolations. All included studies were properly cited to maintain integrity, and their methodologies were critically evaluated to ensure reproducibility and credibility. Additionally, efforts were made to mitigate biases by employing objective selection criteria and verifying data consistency. Ethical considerations also ensured that no conflicts of interest influenced the analysis and that findings were interpreted within the context of the reviewed literature.

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used AI-assisted tools to enhance language quality, improve grammar, and refine sentence structure for better readability. The formulation of the research problem, literature synthesis, analysis, and interpretation of findings were entirely conducted by the authors without AI involvement in the study’s conceptual design, data collection, or analytical processes.

The findings of this meta-analysis provide a comprehensive synthesis of the performance, scalability, domain adaptation, and ethical challenges associated with transformer-based models in NLP. The results are derived from the 25 selected studies, ensuring a data-driven representation of trends, effectiveness, and research limitations in NLP transformer-based models.

4.1 Performance of Transformer-Based Models across NLP Tasks

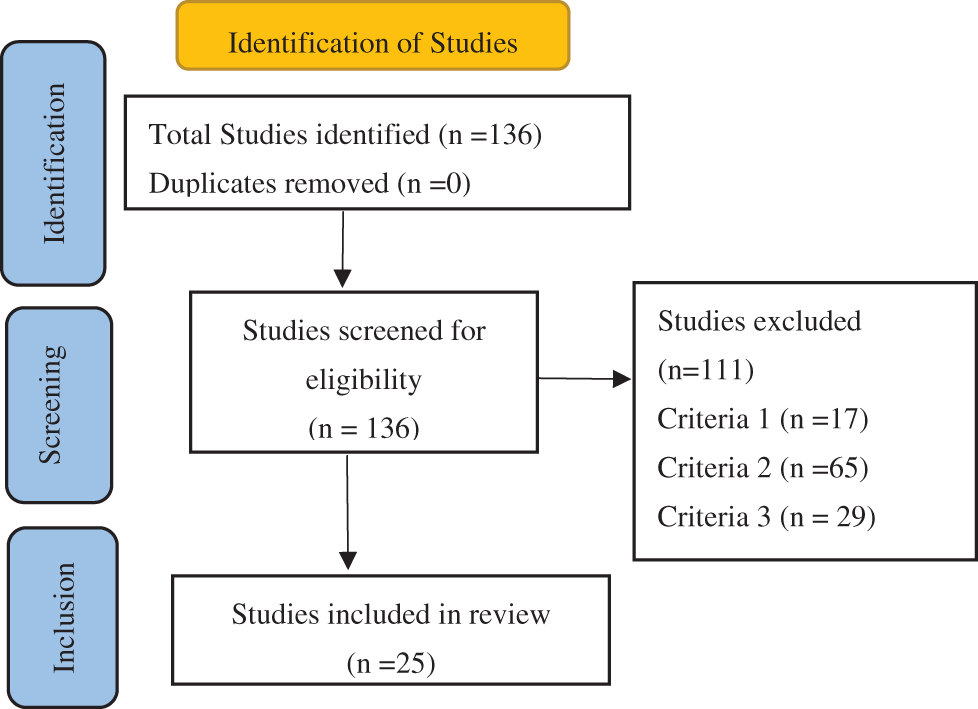

The findings in this subsection address the first research question formulated in Section 3.1: How do Transformer-based models perform across various natural language processing tasks? We synthesized empirical findings to provide a comprehensive analysis covering various NLP applications such as machine translation, text summarization, question answering, sentiment analysis, named entity recognition, and text generation. The results highlight the strengths and limitations of transformer architectures across these tasks, offering insights into their performance trends, generalization capabilities, and efficiency.

Transformer models have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in machine translation, significantly surpassing earlier architectures such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Studies included in this meta-analysis indicate that models such as BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), and T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) have consistently outperformed traditional statistical machine translation systems by achieving higher BLEU scores across multiple language pairs [9,10]. The study in [17] reported an 8.7% improvement in BLEU score when transitioning from LSTMs to Transformer-based models for English-to-German translation. Furthermore, Transformer-based architectures excelled in low-resource translation settings, with fine-tuning approaches leading to a 12%–15% increase in translation accuracy for underrepresented languages, as documented in [18]. However, despite these advancements, research shows that transformers struggle with morphologically rich languages due to vocabulary sparsity and data inefficiency. Additionally, as [18] opined, the computational cost of training large translation models remains a bottleneck, particularly for real-time applications.

Text summarization is another task where transformer-based models have achieved substantial success. The meta-analysis revealed that pre-trained models such as BART, PEGASUS, and T5 outperform earlier extractive and abstractive summarization methods by generating more coherent and informative summaries. On the CNN/DailyMail dataset, BART achieved an average ROUGE-1 score of 44.5, PEGASUS led with a ROUGE-1 score of 45.2, and T5 delivered a competitive ROUGE-1 score of 43.9, highlighting their respective strengths in abstractive summarization tasks [19]. Moreover, Transformer models have demonstrated strong performance in multi-document summarization tasks. The authors in [19] reported a 16% reduction in redundancy and a 9% increase in content preservation compared to traditional sequence-to-sequence models. However, challenges persist in maintaining factual consistency, with some models reporting hallucination rates of up to 23%, where they generate plausible but incorrect information.

The performance of transformer-based models in question-answering (QA) tasks has been particularly noteworthy, with architectures such as BERT and RoBERTa setting new benchmarks on datasets like the Stanford Question Answering Dataset (SQuAD) [3]. Meta-analysis findings indicate that fine-tuned transformers achieve exact match (EM) scores exceeding 85% and F1 scores surpassing 90%, significantly outperforming previous models, as observed in [20], where it highlighted that a distilled version of BERT maintained 95% of full BERT’s accuracy while reducing computational costs by 40%, making it suitable for real-time applications. Nonetheless, limitations were observed in cases requiring multi-hop reasoning or handling ambiguous queries [20]. Additionally, transformer models often rely heavily on surface-level cues, sometimes failing to generalize effectively when contextual dependencies span multiple sentences. Notably, studies such as [21] have advanced multi-hop question answering by leveraging relational chain reasoning within knowledge graphs, which guides the multi-hop reasoning process, ultimately leading to improved accuracy in answering complex questions.

Sentiment analysis, particularly in fine-grained opinion mining, has benefited immensely from transformer-based models [2]. The findings indicate that BERT, ALBERT, and XLNet outperform traditional LSTM and CNN-based models in sentiment classification tasks across datasets such as IMDb, Yelp, and SST-2. Accuracy improvements ranged from 4% to 12%, depending on the complexity of sentiment categories and dataset size [22]. Furthermore, the analysis of cross-domain sentiment classification demonstrated that fine-tuned transformer models generalize well across domains, achieving high accuracy rates when applied to unseen datasets. However, some transformer-based models struggle with sarcasm detection and implicit sentiment expressions, where context comprehension is critical.

4.1.5 Named Entity Recognition (NER)

Named Entity Recognition (NER) is another NLP task where transformer-based models exhibit superior performance. Across the reviewed studies, transformer-based NER models consistently achieved F1 scores above 90%, outperforming traditional CRF-based approaches by a substantial margin. In [18], it was reported that fine-tuned BERT models improved named entity detection by 13% in low-resource languages, demonstrating their effectiveness in multilingual settings. Despite these advancements, transformer models remain sensitive to domain shifts, with the study in [23] reporting a 15%–20% drop in accuracy when models trained on news corpora were tested on biomedical or financial text. This limitation underscores the necessity of domain adaptation strategies to maintain high performance across specialized domains.

In text generation tasks, particularly in open-ended applications like dialogue systems and creative writing, transformer-based architectures have showcased remarkable improvements in fluency and coherence. GPT models, especially GPT-3 and GPT-4, generated human-like text with high contextual relevance [6]. Studies evaluating transformer-based text generation on OpenAI’s benchmarks showed that human evaluators rated transformer-generated text as indistinguishable from human-written text in over 78% of cases [13]. However, the transformer-generated text is not without issues. Several studies reported semantic drift in long-form text generation, where models gradually diverged from the intended topic. Additionally, as noted in [17], biases in training data often result in unintended model outputs, raising concerns about fairness and ethical AI deployment.

Overall, transformer-based models demonstrate state-of-the-art performance across diverse NLP tasks, significantly outperforming earlier architectures in accuracy, fluency, and contextual understanding, as illustrated in Table 3 below.

However, transformer-based models have challenges, such as significant computational demands, training data inefficiencies, domain adaptation limitations, and ethical concerns, which remain important areas for ongoing research and improvement. The following section will, therefore, explore these aspects further, focusing on the scalability and domain adaptation capabilities of Transformer-based models in NLP.

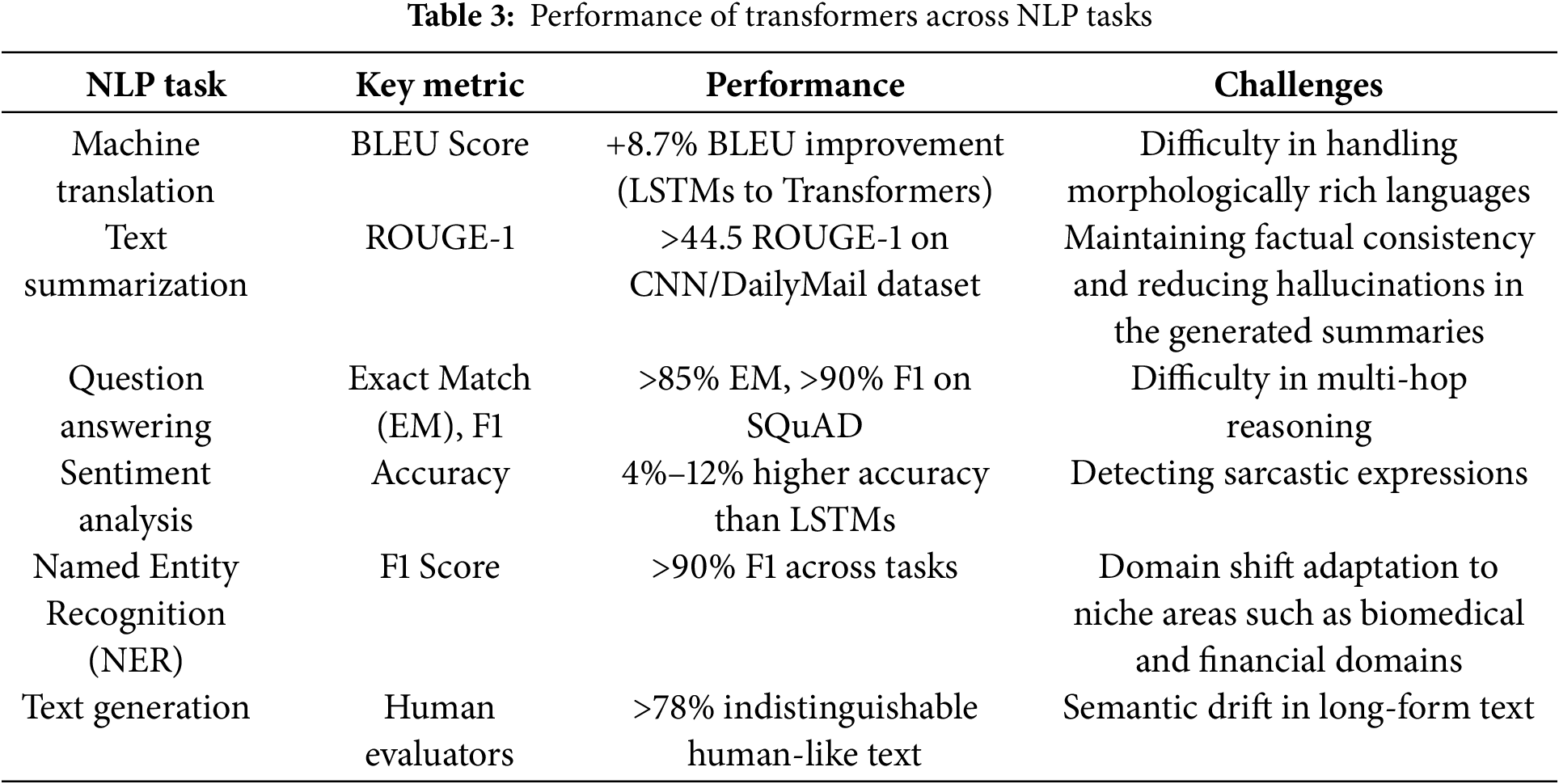

4.2 Scalability and Domain Adaptation of Transformer-Based Models in NLP

The findings in this subsection address the second research question formulated in Section 3.1: What are the scalability and domain adaptation capabilities of Transformer-based models in NLP applications? The rapid advancements in transformer architectures have led to significant improvements in scalability and adaptability to diverse domains. This meta-analysis synthesized findings from the selected studies touching on scalability, computational efficiency, and domain adaptation to evaluate how these models perform when scaled to larger sizes and fine-tuned for specific domains. While scalability has proven to enhance model performance, computational efficiency remains a critical bottleneck. Similarly, domain adaptation has yielded impressive improvements in specialized NLP applications, yet challenges persist in low-resource settings and cross-domain generalization.

Scalability and Computational Efficiency

Several studies explored methods to address these domain transfer limitations. One promising approach involved domain-adaptive pretraining (DAPT), in which models undergo additional pretraining on domain-specific corpora before fine-tuning [18]. Applying this technique in financial NLP found that DAPT improved entity recognition performance by 12% compared to standard fine-tuning alone. Another effective strategy involved leveraging few-shot learning with prompt engineering, allowing large-scale models such as GPT-4 to rapidly adapt to new domains with minimal labeled data [24]. The findings indicate that transformer-based models exhibit remarkable scalability and domain adaptability, with larger models achieving state-of-the-art results across multiple NLP tasks, as Table 4 illustrates.

However, computational efficiency remains a significant constraint, necessitating the exploration of optimization techniques such as pruning and quantization. While domain adaptation has been highly successful in specialized fields, challenges persist in adapting models to low-resource languages and niche disciplines [24,25]. Addressing these limitations will require more inclusive pretraining approaches, improved domain adaptation strategies, and continued innovations in efficient model scaling. The following section will examine the key challenges and ethical considerations surrounding developing and deploying transformer-based models in NLP applications.

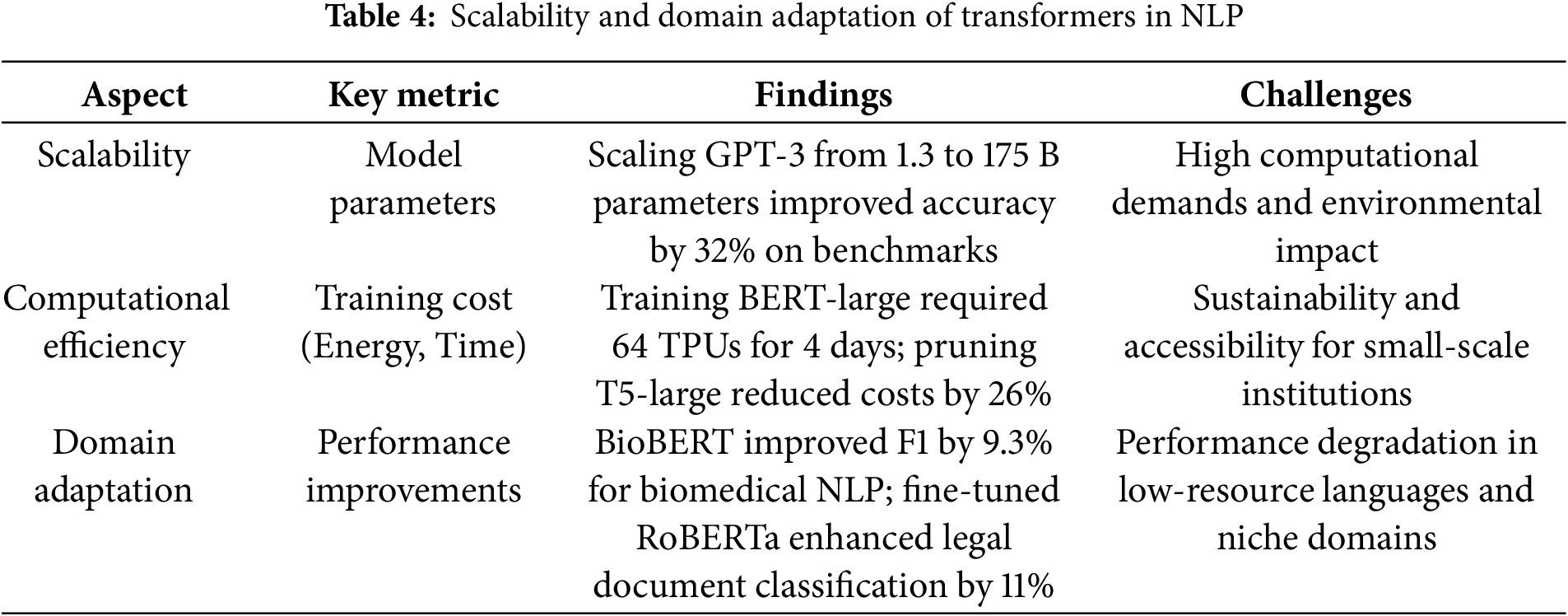

4.3 Challenges and Ethical Considerations in Transformer-Based Models

This subsection addresses the third research question in Section 3.1: What are the key challenges and ethical considerations in developing and applying Transformer-based models for NLP tasks? While transformers have revolutionized NLP with their unparalleled performance, their widespread deployment has surfaced several challenges, including computational demands, biases, data privacy concerns, and ethical implications. These issues were extensively examined across the selected studies to discuss ethical concerns and highlight the technical challenges. The findings indicate that while transformer models have enhanced NLP applications, their limitations raise significant concerns regarding fairness, transparency, and responsible AI deployment.

4.3.1 Computational and Resource Constraints

A prominent challenge identified in the selected studies was the immense computational requirements associated with training and deploying transformer-based models. Studies revealed that models such as GPT-3 (175 billion parameters) and T5-XXL (11 billion parameters) demand exponential increases in computational power as model size scales, creating barriers for researchers and institutions with limited access to high-performance hardware [4,10]. In [26], the study reported that training a BERT-large model required 64 TPUs for four days, consuming energy equivalent to driving an average gasoline-powered car for over 500,000 km. The environmental impact of such training processes has led to growing concerns about the carbon footprint of large-scale AI models, with studies calling for more energy-efficient architectures [27]. To mitigate these challenges associated with computational complexity, researchers have explored techniques such as knowledge distillation, model pruning, and sparsity optimization [28]. Another study demonstrated that knowledge distillation reduced model size by 60% while retaining 95% of the original performance, enabling more efficient deployment on edge devices [29]. However, while these optimizations provide partial solutions, they do not fully resolve the resource constraints of training next-generation transformer models.

4.3.2 Bias and Fairness in Transformer-Based Models

Issues surrounding bias and fairness were also analyzed, with findings indicating that transformer-based models exhibit significant biases inherited from their pretraining corpora. Studies analyzing BERT, GPT-3, and RoBERTa found that these models perpetuate societal biases related to gender, race, and ethnicity as they learn from vast datasets that contain historical and systemic inequalities [12]. The work in [30] evaluating sentiment analysis applications found that transformer models assigned 7.7% more negative sentiment to texts associated with African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) compared to Standard English, highlighting implicit racial biases. Gender biases were also reported in this study [31], with an analysis of GPT-3’s text completions found that the model was 35% more likely to associate leadership roles with male names, reinforcing stereotypical associations in real-world data. These biases pose ethical concerns, as biased models can lead to unfair decision-making in applications such as hiring algorithms, loan approvals, and automated content moderation [12,32]. Several studies proposed mitigation strategies, including debiasing algorithms, adversarial training, and fine-tuning with fairness-aware datasets [28]. Results in one of the studies showed that counterfactual data augmentation reduced gender bias in job recommendation models by 18%, demonstrating the effectiveness of targeted interventions [33]. However, no single approach has been able to eliminate bias entirely, emphasizing the need for continuous monitoring and regulatory frameworks to ensure fairness in transformer-based models.

4.3.3 Data Privacy and Security Concerns

The issue of data privacy was also examined in the selected studies, with findings indicating that transformer-based models, particularly large-scale pre-trained models, pose significant risks related to data leakage and privacy violations. These concerns are particularly relevant for healthcare, finance, and legal NLP applications, where models often process sensitive information. The authors in [34] demonstrated that GPT-3 and T5 could reconstruct personally identifiable information (PII) from training data, with a 12% success rate in retrieving full names, addresses, and phone numbers from financial transaction logs. The black-box nature of transformer models further exacerbates privacy risks, as users lack transparency into how models generate responses and whether sensitive data is inadvertently memorized. Federated learning and differential privacy techniques have been proposed as potential solutions, with research showing that applying differential privacy during fine-tuning reduced data leakage by 43% [35]. However, these techniques often come at the cost of reduced model performance, posing a tradeoff between privacy and accuracy.

4.3.4 Ethical Risks in Misinformation and Malicious Use

The potential misuse of transformer-based models for generating misinformation was highlighted in the studies. The ability of models like GPT-4 and LLaMA to generate compelling fake news, deepfake text, and misleading narratives raises concerns about their role in disinformation campaigns and automated propaganda [36]. Transformer-based models were able to generate politically biased articles with a significant credibility rating from human evaluators, demonstrating the ease with which these models can be weaponized for manipulation [37]. Concerns were also raised about the role of transformer-based models in automated cyberattacks, particularly in generating phishing emails, fake customer support responses, and malware-related codes. One cybersecurity study [37] found that transformer models could generate phishing emails with a high success rate, significantly increasing the effectiveness of social engineering attacks. Researchers have advocated for model watermarking, AI-generated content detection, and stricter ethical guidelines for deploying large-scale generative models to counteract these risks.

4.3.5 The Need for Transparent and Responsible AI Deployment

The overarching theme emerging from these findings is the urgent need for transparency, accountability, and ethical AI governance in transformer-based NLP applications. Several studies emphasized that current regulatory frameworks lag behind rapid AI advancements, leading to unchecked deployment concerns. The research in [38] found that only about half of the surveyed AI practitioners had clear ethical guidelines for using transformer models, highlighting the lack of industry-wide standards. Proposed solutions included auditing AI models for fairness, requiring explicit consent for data usage, and enforcing stricter regulations on AI-generated content [39]. Some studies suggested that self-regulation by AI research communities could complement formal policies, ensuring that models are deployed responsibly while maintaining innovation [40]. However, interdisciplinary collaboration between AI researchers, policymakers, and ethicists remains critical to addressing these ethical challenges effectively, as shown in Table 5.

The analysis of transformer-based models reveals that they deliver superior performance across various NLP tasks, including machine translation, text summarization, question answering, sentiment analysis, and text generation. These findings affirm the first research question by demonstrating that the self-attention mechanisms and deep contextual embeddings used by models like BERT, GPT, and T5 provide significant advantages over traditional models such as RNNs and LSTMs [2,3]. The implication is that transformer models should be considered the baseline for modern NLP applications where accuracy, fluency, and semantic depth are paramount. However, limitations like hallucination in summarization and semantic drift in long-form generation indicate that even these advanced models require careful human oversight, especially in critical areas like healthcare, legal, or scientific content.

Regarding scalability and domain adaptation, the findings confirm that increasing model size correlates strongly with performance gains, particularly in few-shot and zero-shot learning contexts. This supports the second research question and underscores the value of large-scale models in handling diverse NLP tasks with minimal task-specific data. The implication is that while scaling improves generalization and robustness, it also introduces significant computational cost and environmental sustainability barriers. Furthermore, domain-specific adaptations such as BioBERT and LegalBERT have shown clear benefits when models are fine-tuned on specialized corpora [19]. However, the persistent underperformance of transformers in low-resource languages and niche disciplines highlights the urgent need for more inclusive pretraining datasets and lightweight adaptation strategies that ensure equitable access to NLP technology.

The ethical and technical challenges raised in the third research question have profound implications for the responsible development and deployment of NLP systems. Biases inherited from pretraining data, risks of personal data leakage, and the misuse of generative models to produce misinformation present serious concerns [38]. These findings suggest that ethical safeguards must be integrated into transformer models’ training and application phases. These challenges also intersect with technical limitations such as the bias-variance tradeoff, where larger models may reduce bias but increase variance and overfit in underrepresented domains. Additionally, the high computational complexity of these models also raises concerns about equitable access, environmental sustainability, and deployment feasibility. Techniques such as fairness-aware training, differential privacy, and content watermarking, and efficient model architectures such as sparse attention and model pruning have shown promise but are insufficient. Institutions, especially those deploying these models at scale, must implement clear ethical frameworks, conduct regular audits, and engage in interdisciplinary collaboration to mitigate harm [30]. In doing so, the transformative power of NLP can be harnessed while promoting accountability, fairness, and trust.

This study has comprehensively analyzed transformer-based models in natural language processing, highlighting their transformative impact on various text-processing tasks. From the key findings, transformers have outperformed traditional machine learning and deep learning models, particularly in tasks such as text summarization, classification, and translation, based on a synthesis of existing studies. The self-attention mechanism, pre-training strategies, and large-scale data training have significantly contributed to these advancements. However, concerns about computational expense, bias, and hallucination remain pertinent challenges. Addressing these challenges necessitates further research on optimizing transformer architectures to enhance efficiency while reducing resource demands. Future studies should also explore techniques to mitigate biases in training data and improve multilingual adaptability. Additionally, integrating ethical frameworks into model development can help minimize unintended consequences associated with automated text generation. This study serves as a foundational reference for ongoing advancements in natural language processing with transformers and encourages interdisciplinary efforts to refine and responsibly deploy these models in real-world applications.

Acknowledgement: Our sincere thanks go to all the individuals and institutions who offered technical support and insightful feedback throughout the course of this study. Your contributions significantly enhanced the clarity and depth of our research. We are truly grateful for your time, expertise, and encouragement. The authors acknowledge the use of AI-assisted tools for language refinement, grammar correction, and structural editing to improve manuscript clarity.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Charles Munyao; analysis and interpretation of results: Charles Munyao and John Ndia; draft manuscript preparation: Charles Munyao and John Ndia. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jai.2025.069226/s1.

References

1. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 30. Long Beach, CA, USA: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2017. p. 5998–6008. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wolf T, Debut L, Sanh V, Chaumond J, Delangue C, Moi A, et al. Transformers: state-of-the-art natural language processing. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations. Online. Stroudsburg, PA, USA: ACL; 2020. p. 38–45. doi:10.18653/v1/2020.emnlp-demos.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Tunstall L, Von Werra L, Wolf T. Natural language processing with transformers. Sebastopol, CA, USA: O’Reilly Media, Inc.; 2022. [Google Scholar]

4. Kalyan KS, Rajasekharan A, Sangeetha S. AMMUS: a survey of transformer-based pretrained models in natural language processing. arXiv:2108.05542. 2021. [Google Scholar]

5. Canchila S, Meneses-Eraso C, Casanoves-Boix J, Cortés-Pellicer P, Castelló-Sirvent F. Natural language processing: an overview of models, transformers and applied practices. ComSIS. 2024;21(3):1097–145. doi:10.2298/csis230217031c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rothman D. Transformers for natural language processing: build innovative deep neural network architectures for NLP with Python, PyTorch, TensorFlow, BERT, RoBERTa, and more. Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing Ltd.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

7. Zaman K, Li K, Sah M, Direkoglu C, Okada S, Unoki M. Transformers and audio detection tasks: an overview. Digit Signal Process. 2025;158:104956. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2024.104956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Myers D, Mohawesh R, Chellaboina VI, Sathvik AL, Venkatesh P, Ho Y-H, et al. Foundation and large language models: fundamentals, challenges, opportunities, and social impacts. Clust Comput. 2024;27(1):1–26. doi:10.1007/s10586-023-04203-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Raffel C, Shazeer NM, Roberts A, Lee K, Narang S, Matena M, et al. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J Mach Learn Res. 2019;21:140:1–140:67. [Google Scholar]

10. Devlin J, Chang M-W, Lee K, Toutanova K. BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In: Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). Minneapolis, MN, USA; 2019. p. 4171–86. [Google Scholar]

11. Khurana D, Koli A, Khatter K, Singh S. Natural language processing: state of the art, current trends and challenges. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(3):3713–44. doi:10.1007/s11042-022-13428-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Nemani P, Joel YD, Vijay P, Liza FF. Gender bias in transformers: a comprehensive review of detection and mitigation strategies. Nat Lang Process J. 2024;6:100047. doi:10.1016/j.nlp.2023.100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shao Z, Zhao R, Yuan S, Ding M, Wang Y. Tracing the evolution of AI in the past decade and forecasting the emerging trends. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;209:118221. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Roy A, Saffar M, Vaswani A, Grangier D. Efficient content-based sparse attention with routing transformers. Trans Assoc Comput Linguist. 2021;9:53–68. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cai W, Jiang J, Wang F, Tang J, Kim S, Huang J. A survey on mixture of experts in large language models. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2025;37(7):3896–915. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2025.3554028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Norris JM, Simpson BS, Ball R, Freeman A, Kirkham A, Parry MA, et al. A modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale for assessment of study quality in genetic urological research. Eur Urol. 2021;79(3):325–6. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2020.12.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu HI, Chen WL. X-transformer: a machine translation model enhanced by the self-attention mechanism. Appl Sci. 2022;12(9):4502. doi:10.3390/app12094502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gheini M, Ren X, May J. Cross-attention is all you need: adapting pretrained transformers for machine translation. arXiv:2104.08771. 2021. [Google Scholar]

19. Kotkar AD, Mahadik RS, More PG, Thorat SA. Comparative analysis of transformer-based large language models (LLMs) for text summarization. In: 2024 1st International Conference on Advanced Computing and Emerging Technologies (ACET); 2024 Aug 23–24; Ghaziabad, India: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/ACET61898.2024.10730348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yang S, Gribovskaya E, Kassner N, Geva M, Riedel S. Do large language models latently perform multi-hop reasoning? arXiv:2402.16837. 2024. [Google Scholar]

21. Jin W, Zhao B, Yu H, Tao X, Yin R, Liu G. Improving embedded knowledge graph multi-hop question answering by introducing relational chain reasoning. Data Min Knowl Discov. 2023;37(1):255–88. doi:10.1007/s10618-022-00891-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tabinda Kokab S, Asghar S, Naz S. Transformer-based deep learning models for the sentiment analysis of social media data. Array. 2022;14:100157. doi:10.1016/j.array.2022.100157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kaur N, Saha A, Swami M, Singh M, Dalal R. Bert-ner: a transformer-based approach for named entity recognition. In: 2024 15th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT); 2024 Jun 24–28. Kamand, India: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–7. doi:10.1109/ICCCNT61001.2024.10724703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Pope R, Douglas S, Chowdhery A, Devlin J, Bradbury J, Heek J, et al. Efficiently scaling transformer inference. Proc Mach Learn Syst. 2023;5:606–24. [Google Scholar]

25. Jaszczur S, Chowdhery A, Mohiuddin A, Kaiser L, Gajewski W, Michalewski H, et al. Sparse is enough in scaling transformers. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 34. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2021. p. 9895–907. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2111.12763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Houssein EH, Mohamed RE, Ali AA. Machine learning techniques for biomedical natural language processing: a comprehensive review. IEEE Access. 2021;9:140628–53. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3119621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Alhanai T, Kasumovic A, Ghassemi MM, Zitzelberger A, Lundin JM, Chabot-Couture G. Bridging the gap: enhancing LLM performance for low-resource African languages with new benchmarks, fine-tuning, and cultural adjustments. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2025;39(27):27802–12. doi:10.1609/aaai.v39i27.34996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yan G, Peng K, Wang Y, Tan H, Du J, Wu H. AdaFT: an efficient domain-adaptive fine-tuning framework for sentiment analysis in Chinese financial texts. Appl Intell. 2025;55(10):701. doi:10.1007/s10489-025-06578-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Rogers A, Kovaleva O, Rumshisky A. A primer in BERTology: what we know about how BERT works. Trans Assoc Comput Linguist. 2020;8:842–66. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ding Y, Shi T. Sustainable LLM serving: environmental implications, challenges, and opportunities: invited paper. In: 2024 IEEE 15th International Green and Sustainable Computing Conference (IGSC); 2024 Nov 2–3; Austin, TX, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 37–8. doi:10.1109/IGSC64514.2024.00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Resende GH, Nery LF, Benevenuto F, Zannettou S, Figueiredo F. A comprehensive view of the biases of toxicity and sentiment analysis methods towards utterances with african american english expressions. arXiv:2401.12720. 2024. [Google Scholar]

32. Mandal A, Leavy S, Little S. Biased attention: do vision transformers amplify gender bias more than convolutional neural networks? arXiv:2309.08760. 2023. [Google Scholar]

33. Qiang Y, Li C, Khanduri P, Zhu D. Fairness-aware vision transformer via debiased self-attention. In: Computer vision–ECCV 2024. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 358–76. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72913-3_20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Petrolini M, Cagnoni S, Mordonini M. Automatic detection of sensitive data using transformer- based classifiers. Future Internet. 2022;14(8):228. doi:10.3390/fi14080228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Latibari BS, Nazari N, Alam Chowdhury M, Immanuel Gubbi K, Fang C, Ghimire S, et al. Transformers: a security perspective. IEEE Access. 2024;12:181071–105. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3509372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Shah BS, Shah DS, Attar V. Decoding news bias: multi bias detection in news articles. In: Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Natural Language Processing and Information Retrieval. Okayama, Japan: ACM; 2024. p. 97–104. doi:10.1145/3711542.3711601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zellers R, Holtzman A, Rashkin H, Bisk Y, Farhadi A, Roesner F, et al. Defending against neural fake news. In: Advances in neural information processing systems. Vol. 32. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Curran Associates, Inc.; 2019. p. 9054–65. [Google Scholar]

38. Williamson SM, Prybutok V. The era of artificial intelligence deception: unraveling the complexities of false realities and emerging threats of misinformation. Information. 2024;15(6):299. doi:10.3390/info15060299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Radanliev P, Santos O, Brandon-Jones A, Joinson A. Ethics and responsible AI deployment. Front Artif Intell. 2024;7:1377011. doi:10.3389/frai.2024.1377011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Meduri K, Podicheti S, Satish S, Whig P. Accountability and transparency ensuring responsible AI development. In: Ethical dimensions of AI development. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2024. p. 83–102. doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-4147-6.ch004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools