Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Analysis and Prediction of Real-Time Memory and Processor Usage Using Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Department of Mathematical Engineering, Faculty of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering, Yildiz Technical University, Istanbul, 34220, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Kadriye Simsek Alan. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 397-415. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.071133

Received 01 August 2025; Accepted 17 September 2025; Issue published 20 October 2025

Abstract

Efficient utilization of processor and memory resources is essential for sustaining performance and energy efficiency in modern computing infrastructures. While earlier research has emphasized CPU utilization forecasting, joint prediction of CPU and memory usage under real workload conditions remains underexplored. This study introduces a machine learning–based framework for real-time prediction of CPU and RAM utilization using the Google Cluster Trace 2019 v3 dataset. The framework combines Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) with a MultiOutputRegressor (MOR) to capture nonlinear interactions across multiple resource dimensions, supported by a leakage-safe imputation strategy that prevents bias from missing values. Nested cross-validation was employed to ensure rigorous evaluation and reproducibility. Experiments demonstrated that memory usage can be predicted with higher accuracy and stability than processor usage. Residual error analysis revealed balanced error distributions and very low outlier rates, while regime-based evaluations confirmed robustness across both low and high utilization scenarios. Feature ablation consistently highlighted the central role of page cache memory, which significantly affected predictive performance for both CPU and RAM. Comparisons with baseline models such as linear regression and random forest further underscored the superiority of the proposed approach. To assess adaptability, an online prequential learning pipeline was deployed to simulate continuous operation. The system preserved offline accuracy while dynamically adapting to workload changes. It achieved stable performance with extremely low update latencies, confirming feasibility for deployment in environments where responsiveness and scalability are critical. Overall, the findings demonstrate that simultaneous modeling of CPU and RAM utilization enhances forecasting accuracy and provides actionable insights for cache management, workload scheduling, and dynamic resource allocation. By bridging offline evaluation with online adaptability, the proposed framework offers a practical solution for intelligent and sustainable cloud resource management.Keywords

Cloud computing has become the backbone of modern digital infrastructure, with dynamic workloads that directly affect system stability, cost efficiency, and energy sustainability. Accurate prediction of CPU and memory (RAM) usage is central to proactive resource management, enabling improved scheduling, load balancing, and energy-aware provisioning. As cloud environments continue to grow in scale and diversity, the ability to forecast multi-resource utilization in real time has emerged as a critical requirement for operational reliability and economic efficiency.

This necessity has stimulated considerable research interest. Early studies focused mainly on CPU utilization, while subsequent work adopted deep learning models to capture temporal dependencies and nonlinear patterns. More recent contributions have combined predictive modeling with optimization frameworks, emphasized online adaptability, or incorporated operational concerns such as uncertainty, energy efficiency, and Service Level Agreement (SLA) compliance. These developments are systematically reviewed in the Literature Review section under thematic categories.

Literature Review

Research on cloud workload prediction has evolved across several methodological directions, each reflecting different priorities such as accuracy, scalability, efficiency, and adaptability. Early efforts focused on classical machine learning due to their interpretability and low computational cost, whereas subsequent studies increasingly explored deep learning to capture temporal dependencies and nonlinear patterns. More recent contributions have combined predictive models with optimization, emphasized online adaptability, or incorporated operational constraints such as uncertainty and energy efficiency. This section presents the literature under thematic headings and systematically reviews the developments in the field.

Classical Machine Learning Approaches

Early research in cloud workload forecasting relied heavily on classical machine learning techniques, valued for their interpretability and modest computational demands. Shaikh et al. [1] offered one of the most comprehensive benchmarks, comparing linear regression, decision trees, boosting, and support vector regression with deep models such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Bi-LSTM on BitBrains and Azure traces. Their evaluation highlighted (Bi-LSTM) as a strong performer for CPU and throughput forecasting, while also showing that ensemble-based methods retained practical competitiveness.

Further contributions enriched this tradition from different perspectives. Zheng et al. [2] integrated Random Forests and Gradient Boosting with a dynamic scheduling engine, demonstrating how prediction can be embedded directly into provisioning decisions. Deric et al. [3] addressed CPU provisioning in Software-defined networking (SDN) hypervisors by proposing a percentile-based prediction framework validated across multiple network topologies.

Together, these studies established important baselines but were often limited to CPU utilization, showed reduced adaptability to heterogeneous workloads, and captured only partial aspects of long-term temporal dynamics. Such constraints paved the way for more advanced approaches based on deep learning, which sought to capture complex dependencies across time and multiple resources.

Deep Learning Models

As cloud workloads became increasingly complex and heterogeneous, deep learning models emerged as a dominant approach for resource usage prediction. An early precursor was Zhang et al. [4], who applied a recurrent neural network (RNN) to Google’s production traces, demonstrating the feasibility of sequence-aware modeling on operational data and motivating later LSTM/Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) variants for workload prediction.

Ahamed et al. [5] conducted a systematic comparison of recurrent neural networks, multilayer perceptrons, convolutional networks, and LSTMs on real data center traces. Their work emphasized that predictive reliability is strongly influenced by preprocessing steps such as cleaning, normalization, and resampling, alongside the architecture itself.

Xu et al. [6] introduced the efficient supervised learning-based Deep Neural Network (esDNN), a hybrid framework combining gated recurrent units with convolutional layers, further enhanced with Swish activations. Applied to Alibaba and Google traces, the model demonstrated the ability to capture both temporal dependencies and local patterns, reducing server activity in auto-scaling simulations and yielding cost and energy benefits. Its innovation lies in addressing gradient stability while exploiting multivariate correlations.

Other studies illustrate the breadth of deep learning applications. Bi et al. [7] proposed Bi-Gated Long Short-Term Memory (BG-LSTM), integrating Bi-directional LSTM and GridLSTM to jointly capture short-term and structural workload patterns. Girish and Raviprakash [8] showed that stacked LSTM variants outperform Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) in short-horizon CPU forecasting. Al-Asaly et al. [9] reformulated workload prediction as a spatiotemporal graph learning problem, enabling simultaneous modeling of spatial correlations among virtual machines and temporal sequences.

Collectively, these studies demonstrated that deep learning significantly expands the capacity to model temporal dependencies and nonlinear interactions in workload traces. Yet the literature has often remained CPU-centric, with limited exploration of multi-resource interactions such as memory and I/O, and training costs have posed challenges for real-time deployment. These issues motivated hybrid approaches that combine deep architectures with optimization and reinforcement learning to enhance adaptability and efficiency.

Hybrid & Optimization-Based Strategies

Alongside purely statistical or deep learning–driven methods, another research direction has combined predictive models with optimization frameworks, aiming to balance forecasting accuracy with system-level adaptability. Lekkala [10] presented a comprehensive AI-driven framework that integrates workload forecasting, resource utilization prediction, and real-time optimization. The approach leveraged temporal convolutional networks and GRUs for workload prediction, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)–LSTM hybrids for resource usage, and reinforcement learning strategies for adaptive allocation. This orchestration of multiple techniques underscored the potential of combining deep architectures with optimization to achieve both predictive accuracy and efficient control.

Khan et al. [11] advanced this paradigm by emphasizing energy-aware scheduling in cloud environments. Their study combined recurrent neural networks with clustering and regression to forecast workloads while estimating energy consumption states. By clustering VMs and inferring low, medium, and high energy states, the work explicitly linked predictive modeling to sustainability objectives, highlighting the dual benefits of efficiency and cost reduction.

Additional contributions illustrate diverse hybridization strategies. Wen et al. [12] proposed a hybrid model combining Deep Belief Networks (DBNs) with Particle Swarm Optimization, illustrating the stabilizing effect of evolutionary optimization on neural forecasts. Devi and Valli [13] developed a hybrid ARIMA–Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model, balancing linear and nonlinear components for workload prediction. Malik et al. [14] proposed a Functional Link Neural Network trained with genetic algorithm and particle swarm optimization, demonstrating that evolutionary algorithms can improve multi-resource prediction

Taken together, these studies illustrate how predictive modeling can be embedded within optimization and control pipelines, extending beyond accuracy toward energy efficiency, sustainability, and domain-specific adaptation. However, hybrid approaches often introduce algorithmic and orchestration complexity, motivating interest in lighter online learning strategies for real-time adaptability.

Online & Real-Time Learning

With the growing need for immediate adaptability in cloud platforms, a strand of research has focused on online and real-time learning methods. Setayesh et al. [15] proposed a pruned-GRU framework designed for streaming workloads. Their approach reduced the number of parameters through pruning, enabling the model to adapt quickly to new input without sacrificing predictive quality.

At an industrial scale, Wang et al. [16] introduced Amazon Chronos, a transformer-based forecasting system pre-trained on massive datasets. Chronos demonstrated high accuracy and strong scalability, positioning transformers as viable solutions for large-scale workload forecasting. However, its reliance on GPU-class resources underscores the tension between predictive power and computational efficiency in real-time settings.

Other contributions explored variations of online adaptation. Dittakavi [17] integrated GRUs with temporal fusion transformers in feedback loops to handle long-range dependencies while supporting online updates. Nguyen Quoc et al. [18] developed periodicity-aware ensembles that adapt to recurring workload cycles, showing that online learning can benefit from domain-specific temporal priors.

Collectively, this body of work emphasizes the transition from batch-trained models toward adaptive learners capable of evolving with dynamic workloads. Yet challenges remain in balancing predictive accuracy with low-latency constraints and in ensuring robustness under non-stationarity. These limitations have inspired complementary research into uncertainty modeling and sustainability-driven design.

Uncertainty, Energy, and SLA Constraints

Beyond accuracy-centered forecasting, recent studies have increasingly emphasized uncertainty quantification, energy efficiency, and service-level guarantees in workload prediction. Rossi et al. [19] advanced this perspective by applying Bayesian neural networks and probabilistic LSTMs to cloud traces. Their contribution lies in explicitly modeling predictive variance, enabling forecasts to provide not only point estimates but also confidence intervals. This uncertainty-aware approach is particularly valuable in environments with bursty loads or strict quality-of-service requirements.

Energy-aware forecasting has also gained momentum. Building on predictive frameworks, Khan et al. [11] explored semi-supervised transfer learning and clustering techniques to categorize virtual machines into energy states such as low, medium, and high consumption. By integrating workload prediction with energy profiling, the study linked forecasting outcomes to sustainability objectives, showing that energy-efficient scheduling can reduce operational costs without undermining performance.

Other works have highlighted service-level concerns. Sireesha et al. [20] developed an SLA-sensitive LSTM framework that dynamically adjusts predictions to preempt potential violations. By aligning resource forecasts with service contracts, the framework emphasizes resilience and proactive management in cloud environments.

Taken together, this body of research highlights that accuracy alone is insufficient in evaluating forecasting methods. Incorporating predictive uncertainty, energy considerations, and SLA compliance reflects a broader shift toward operationally sustainable and trustworthy cloud resource management. This perspective also sets the stage for integrating these concerns into adaptive learning frameworks.

Despite considerable advances in workload prediction, the existing literature remains constrained by several gaps. Most studies have focused primarily on CPU utilization, with limited treatment of memory or joint multi-resource forecasting. Missing values, which are pervasive in large-scale traces, are often disregarded or handled in ways that risk data leakage, raising concerns about reproducibility. While accuracy metrics such as mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean squared error (RMSE) are widely reported, residual distributions, outliers, and regime-specific errors—critical for operational reliability—are rarely analyzed. In addition, many deep learning solutions achieve high accuracy but rely heavily on GPU resources, limiting their practical deployment in real-time or resource-constrained environments. Finally, online and continuous learning approaches are only beginning to emerge, and lightweight implementations with low latency remain scarce.

This study addresses these shortcomings by presenting a multi-output prediction framework that jointly models CPU and memory usage. Missing data are handled with a leakage-safe, machine-specific imputation strategy. Beyond aggregate accuracy, the framework systematically analyzes out-of-fold residuals, outliers, and workload regimes to provide a deeper view of predictive behavior. Most importantly, we move from offline benchmarking to a continuous prequential (test-then-train) pipeline that sustains near-perfect accuracy with sub-millisecond update latency on CPU-only (GPU-free) hardware, demonstrating feasibility in resource-constrained, cost-sensitive environments. By bridging accuracy, interpretability, and deployability—especially for edge/fog scenarios—our work offers a practical and sustainable solution for real-world cloud systems.

We use the public Google Cluster Trace 2019 v3 (GCT19-v3) dataset, which contains anonymized, large-scale data-center traces of task/instance executions and machine-level resource usage.

In this study, CPU utilization and RAM utilization are the target variables, both evaluated on a relative [0, 1] scale (0 = 0%, 1 = 100%). Predictor variables are derived from relevant system/performance fields in the trace.

Before training, the dataset was preprocessed to handle missing values and prepare features. Two columns, Cycles per Instruction (CPI; number of CPU cycles per retired instruction) and Memory Accesses per Instruction (MAI; average memory references per instruction), contained missing values. These were first imputed using machine-specific averages, and any remaining missing entries were filled with the global mean calculated from the training fold, ensuring no data leakage. To validate that this imputation procedure did not introduce any bias, two conditions were compared within a five-fold (5-fold) cross-validation: S0 (no imputation; rows with missing values excluded) and S1 (machine-specific mean imputation applied). As shown in Table 1, the predictive performance metrics for CPU and RAM (MAE, RMSE, and R2) are identical between S0 and S1 in every fold, with Δ = 0.0000 across all metrics. This finding confirms that the imputation did not affect predictive accuracy and did not introduce any systematic bias.

The variables Page Cache Memory (MB), Assigned Memory (MB), Cycles per Instruction (CPI), Memory Accesses per Instruction (MAI), and Sampling Rate (Hz) were used throughout the manuscript and figures, with standardized human-readable labels and units to improve readability and ensure consistency.

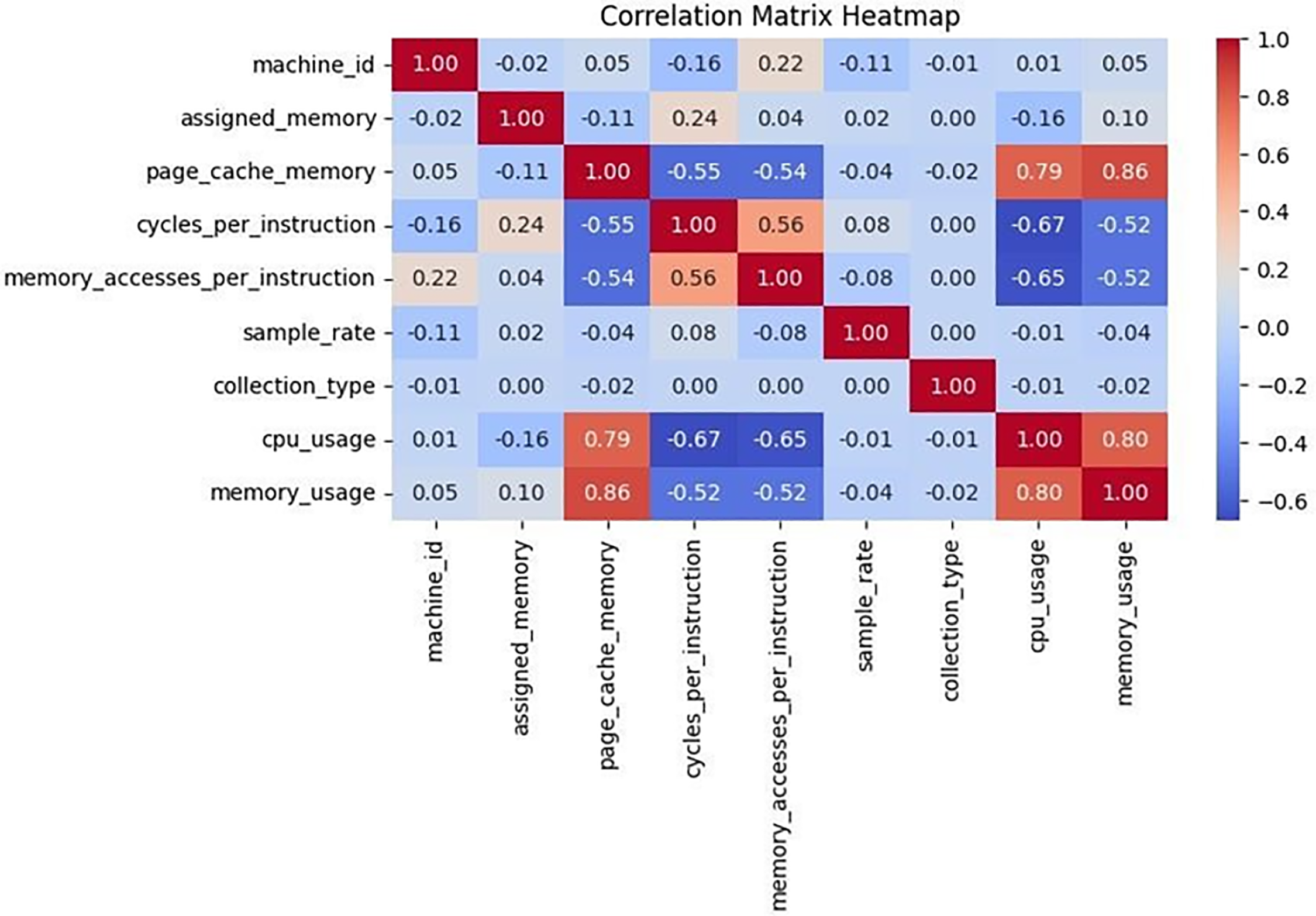

Resource usage fields were separated into CPU and memory components for modeling. Feature scaling was applied where appropriate, and categorical identifiers (e.g., machine ID, collection type) were excluded due to low correlation with the target variables. To justify the use of a multi-output regression approach, the correlation between CPU and memory usage was analyzed and found to be strongly positive, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Correlation matrix heatmap

In the modeling and prediction phase, XGBoost was identified as the best-performing algorithm for the problem at hand due to its ability to learn nonlinear interactions, high predictive accuracy, and fast execution. Because XGBoost natively supports only single-target prediction, we employed it with MultiOutputRegressor, which trains separate models per target (CPU, RAM) under a unified pipeline, ensuring consistent preprocessing, evaluation, and experimental setup. Thus, we obtain an integrated model that predicts CPU and RAM usage separately yet concurrently.

In model selection, XGBoost’s fast training and parallelism were advantageous for large datasets. For reproducibility, hyperparameter tuning was performed via grid search with 5-fold cross-validation on the training set. The search explored 48 candidate configurations across the following ranges: n_estimators ∈ {100, 200, 300, 500}, max_depth ∈ {3, 4, 6, 8}, learning_rate ∈ {0.01, 0.05, 0.1}, subsample ∈ {0.6, 0.7, 0.8}, and colsample_bytree ∈ {0.6, 0.7, 0.8}. The optimization criterion was root mean squared error (RMSE). The best configuration, consistently selected across folds (10 times in the search results), was: colsample_bytree

The best configuration frequently emerged during cross-validation (e.g., colsample_bytree = 0.7, learning_rate = 0.05, max_depth

Performance was then evaluated using MAE, Mean Squared Error (MSE), RMSE, and R2 computed from 5-fold out-of-fold (OOF) predictions. We define residuals as out-of-fold (OOF) prediction errors with no temporal implication:

where index

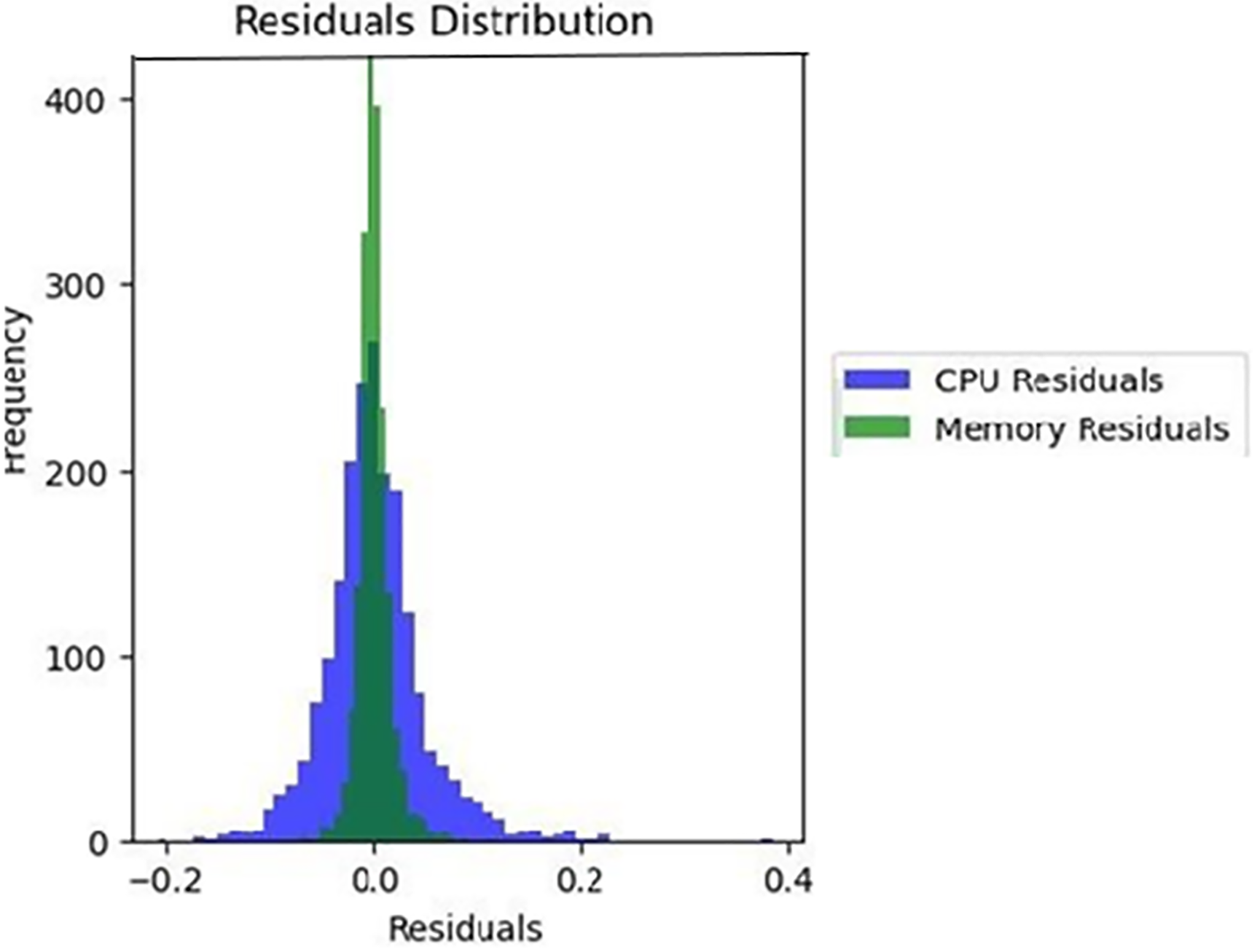

MSE and RMSE were small for both targets (with RAM lower than CPU), and residuals were near-symmetric with means

These quantitative results are further supported by the residual distributions, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Distribution of errors

Fig. 2. OOF residual histograms for CPU and RAM. Dashed vertical lines indicate IQR-based lower/upper cutoffs [Q1 − 1.5⋅IQR, Q3 + 1.5⋅IQR]. Distributions are approximately symmetric with near-zero means; outlier rates remain below 1% (CPU ≈ 0.53%, RAM ≈ 0.37%). CPU residuals are shown in blue and RAM residuals are shown in green.

To further assess robustness, samples were partitioned into tertiles of predicted values (ŷ), representing low, mid, and high operating ranges. The results are summarized in Table 2. Errors increase in the upper regime yet remain within practically acceptable bounds, indicating that the model maintains predictive accuracy across different load conditions.

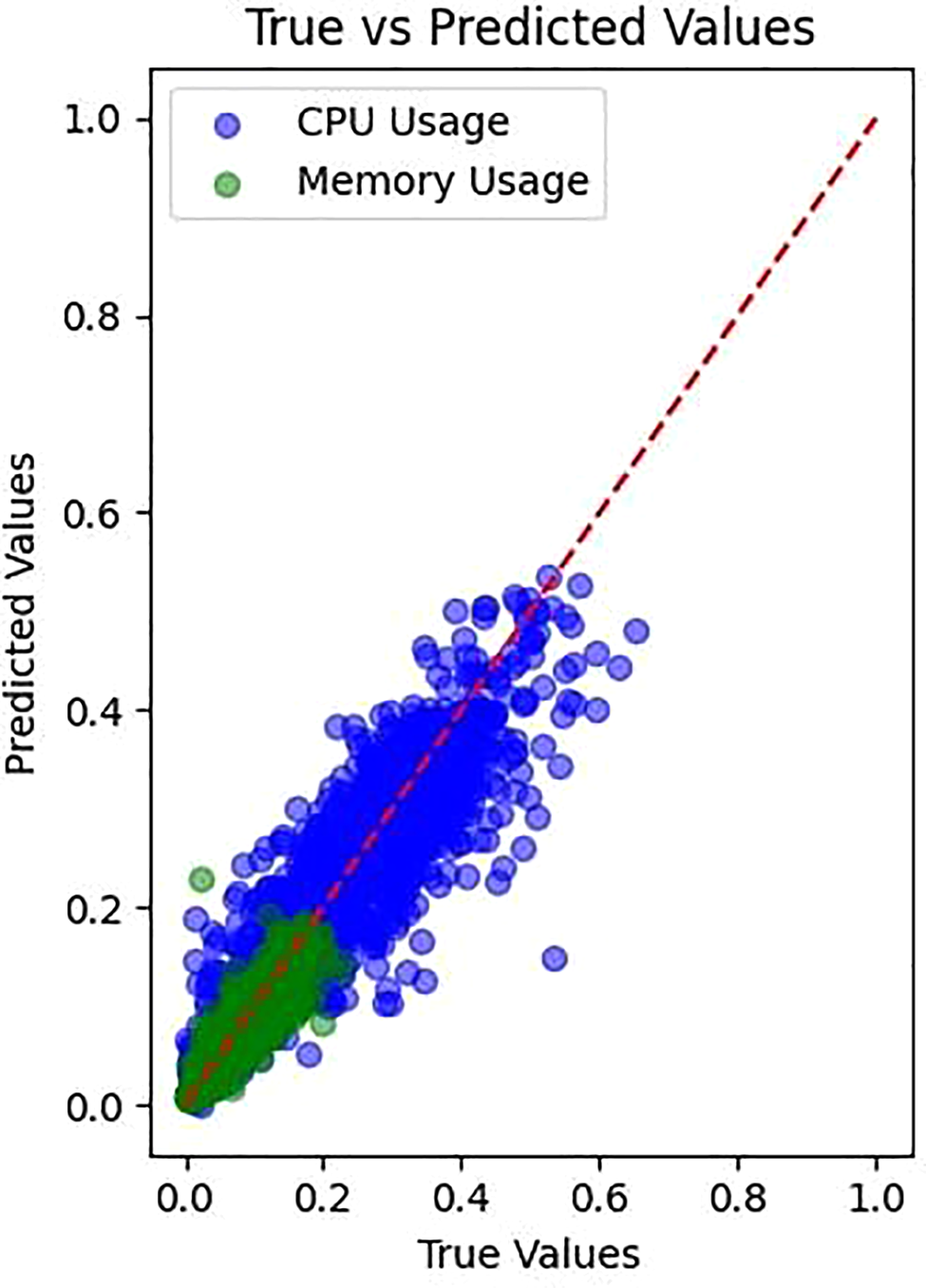

To further validate predictive accuracy, Fig. 3 compares the actual vs. predicted values for both CPU and RAM.

Figure 3: Actual vs. predicted values

Fig. 3. Actual vs. predicted values for CPU and RAM. The red diagonal line represents the ideal case where predictions perfectly match true values. Both CPU and RAM predictions closely followed this ideal line, confirming the model’s overall effectiveness. However, minor deviations were observed, particularly at high usage values, suggesting potential limitations in model accuracy under peak system loads.

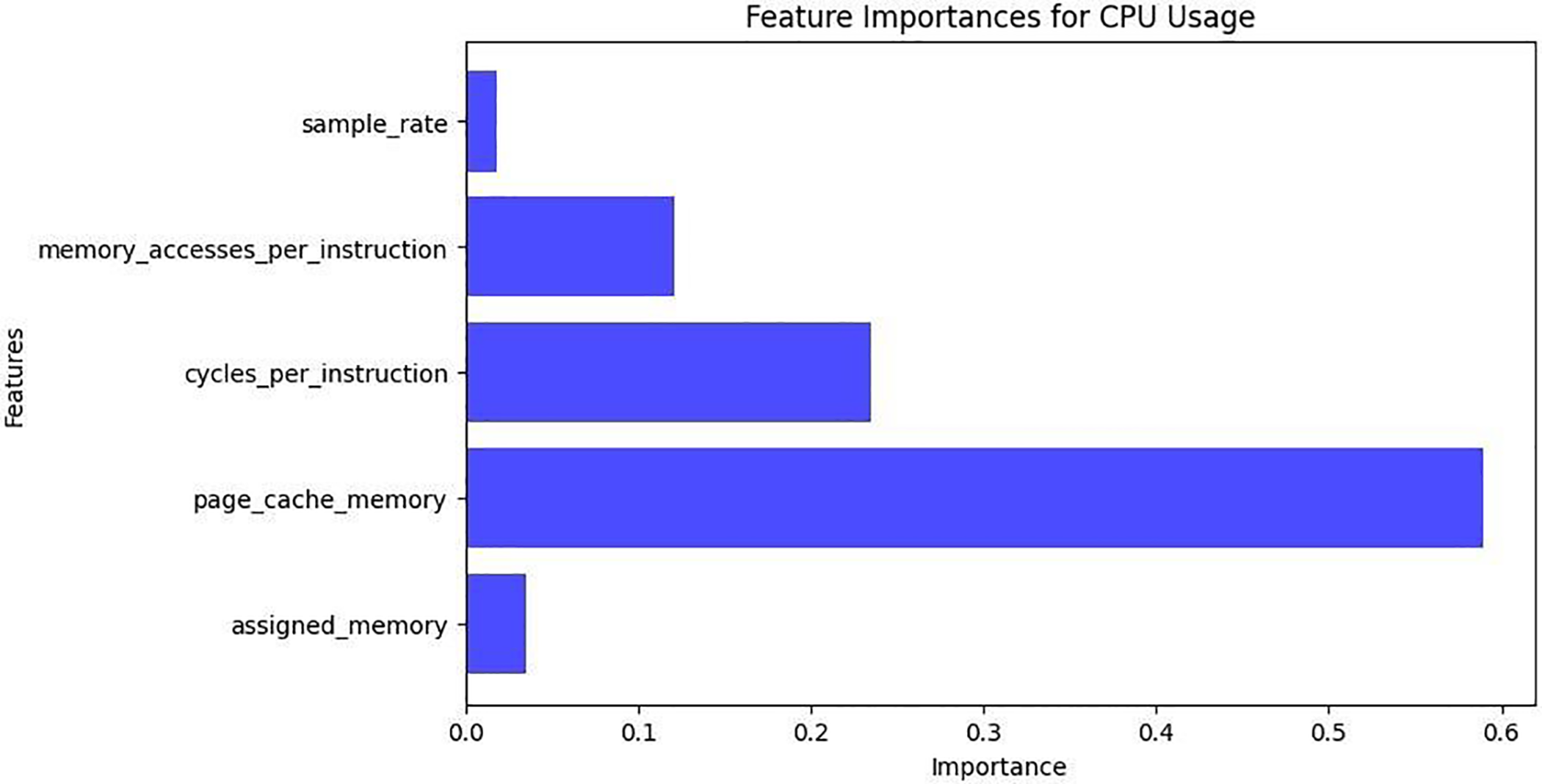

Based on the model results, an in-depth analysis was conducted to identify the key variables influencing CPU and memory usage. The features most heavily weighted by the model during the prediction phase—those contributing significantly to CPU and memory behavior—are presented below, supported by corresponding visuals. For CPU usage, the variable Page Cache Memory emerged as the most influential factor, indicating a high workload due to cache management activities. The second most impactful variable, Cycles per Instruction, represents the number of cycles needed by the processor to execute instructions. Additional variables such as memory_accessesper instruction and Sampling Rate were found to have lesser yet non-negligible impact on CPU load. To further evaluate model behavior, feature importance was analyzed separately for CPU and memory usage predictions.

Fig. 4 displays the relative importance of different features in predicting CPU usage. Among all variables, page cache memory stands out as the most significant predictor, indicating that intensive caching operations have a strong influence on processor load. Cycles per Instruction also contributes notably, reflecting the effect of computational complexity. Memory_accesses_per_instruction and assigned memory show moderate importance, while Sampling Rate has minimal impact on CPU usage. This confirms that managing cache efficiently is central to optimizing CPU performance.

Figure 4: Important features for CPU usage

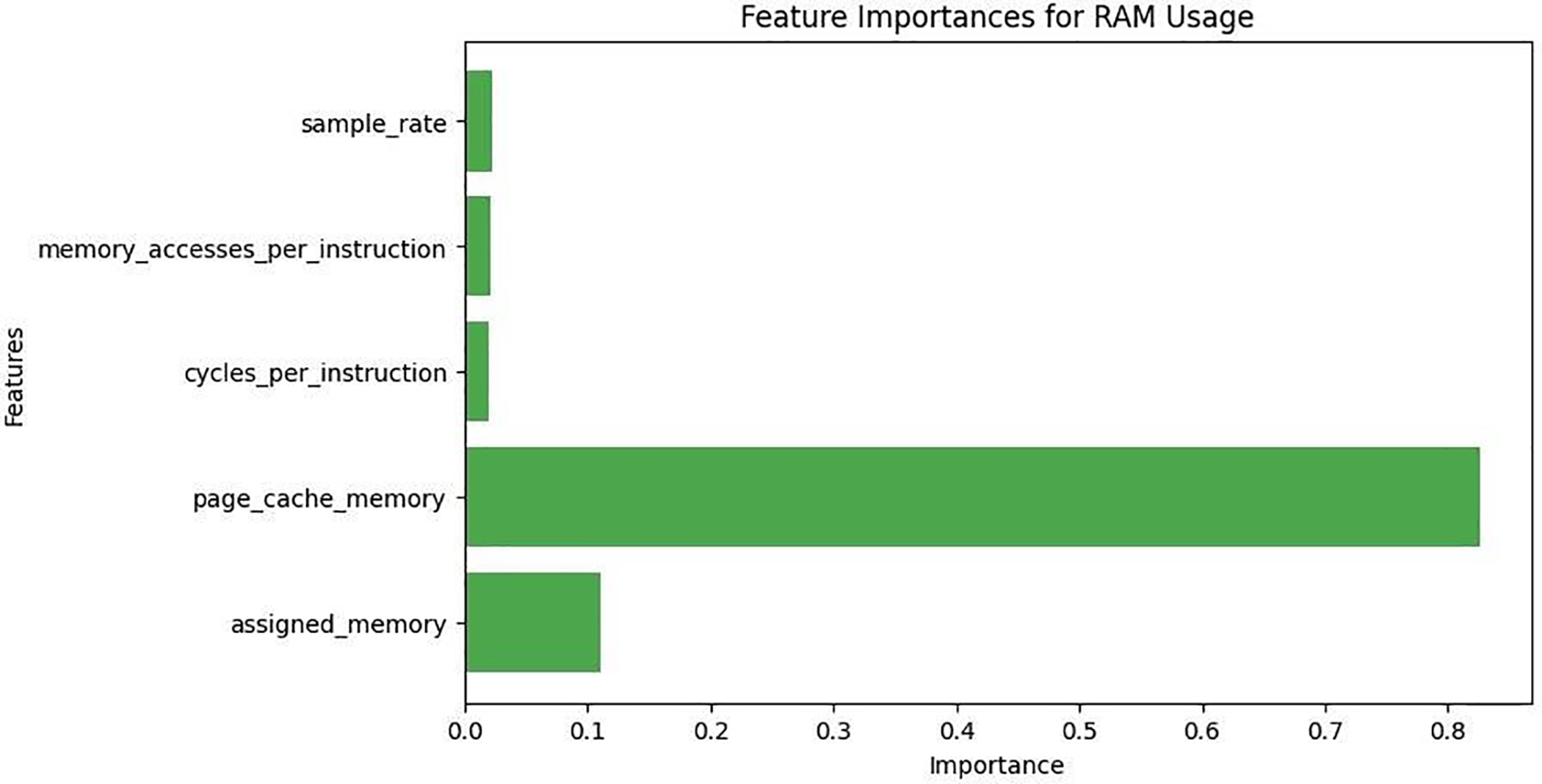

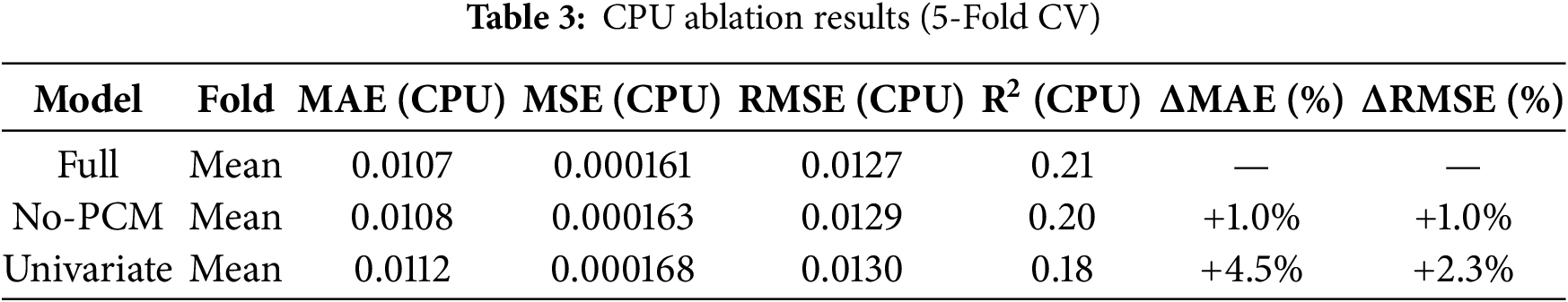

Fig. 5 illustrates the contribution of various features to RAM usage prediction. Page cache memory is by far the most influential factor, highlighting the substantial role of caching in memory consumption. Assigned memory ranks second, indicating its relevance in reflecting system-allocated memory. In contrast, Cycles per Instruction, Memory Accesses per Instruction, and Sampling Rate have minimal impact on RAM usage. These results emphasize that RAM consumption is primarily driven by caching and allocation behaviors, rather than instruction-level operations. These ablation experiments confirm that page cache memory substantially contributes to predictive accuracy. Specifically, removing this variable increased CPU errors by approximately 1% and RAM errors by about 2%, while further restricting the predictors to univariate baselines amplified the degradation (CPU

Figure 5: Important features for memory usage

Taken together, the ablation experiments confirm that page cache memory exerts a measurable impact on both CPU and RAM prediction accuracy, validating its central role in resource utilization. After identifying key variables, anomaly detection was applied to uncover irregularities in CPU and memory usage patterns:

• Page Cache Memory: Spikes in page cache memory suggest inefficiencies in cache handling, potentially causing memory bottlenecks.

• Cycles per Instruction: Deviations indicated the CPU was consuming more cycles than typical, hinting at performance inefficiencies.

• Memory Accesses per Instruction: Detected irregular memory access behaviors may destabilize system performance.

• Sample Rate: Unusual fluctuations suggest issues in data collection frequency, affecting resource monitoring.

• Assigned Memory: Variability here pointed to imbalanced allocation, possibly stemming from memory leaks or inefficient cleanup routines.

These anomalies highlight areas for system-level refinement. Anomaly detection proved to be a useful approach for identifying performance constraints and potential inefficiencies.

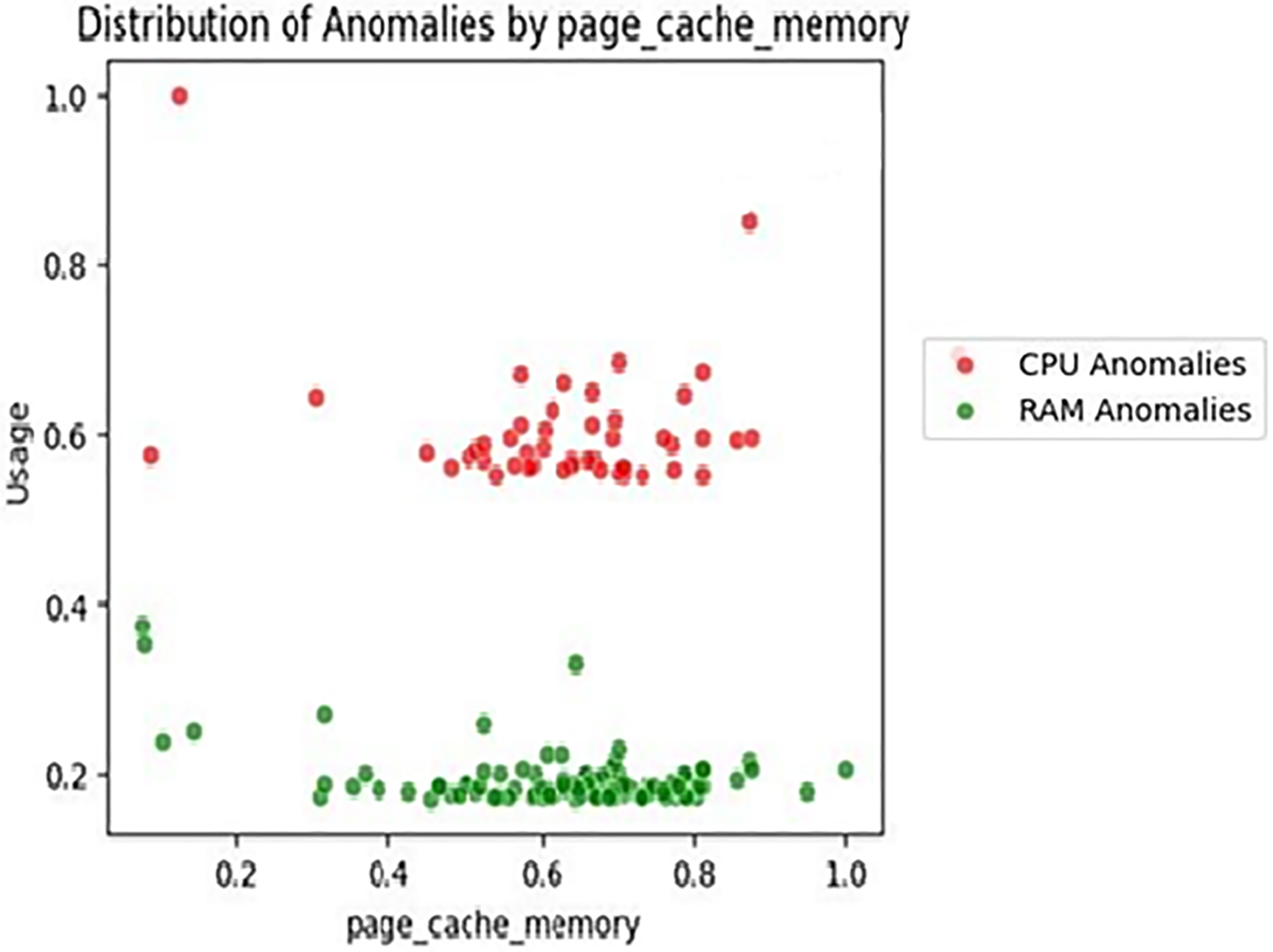

Fig. 6 visualizes how CPU and RAM anomalies are distributed in relation to page cache memory values. CPU anomalies (red) tend to cluster around mid-to-high cache usage levels (0.5–0.8), indicating a strong association between intensive caching and abnormal CPU behavior. In contrast, RAM anomalies (green) appear more scattered and less concentrated, suggesting a weaker correlation. These observations highlight page cache memory as a critical indicator for identifying potential CPU performance degradation.

Figure 6: Distribution of CPU and RAM anomalies with respect to page cache memory

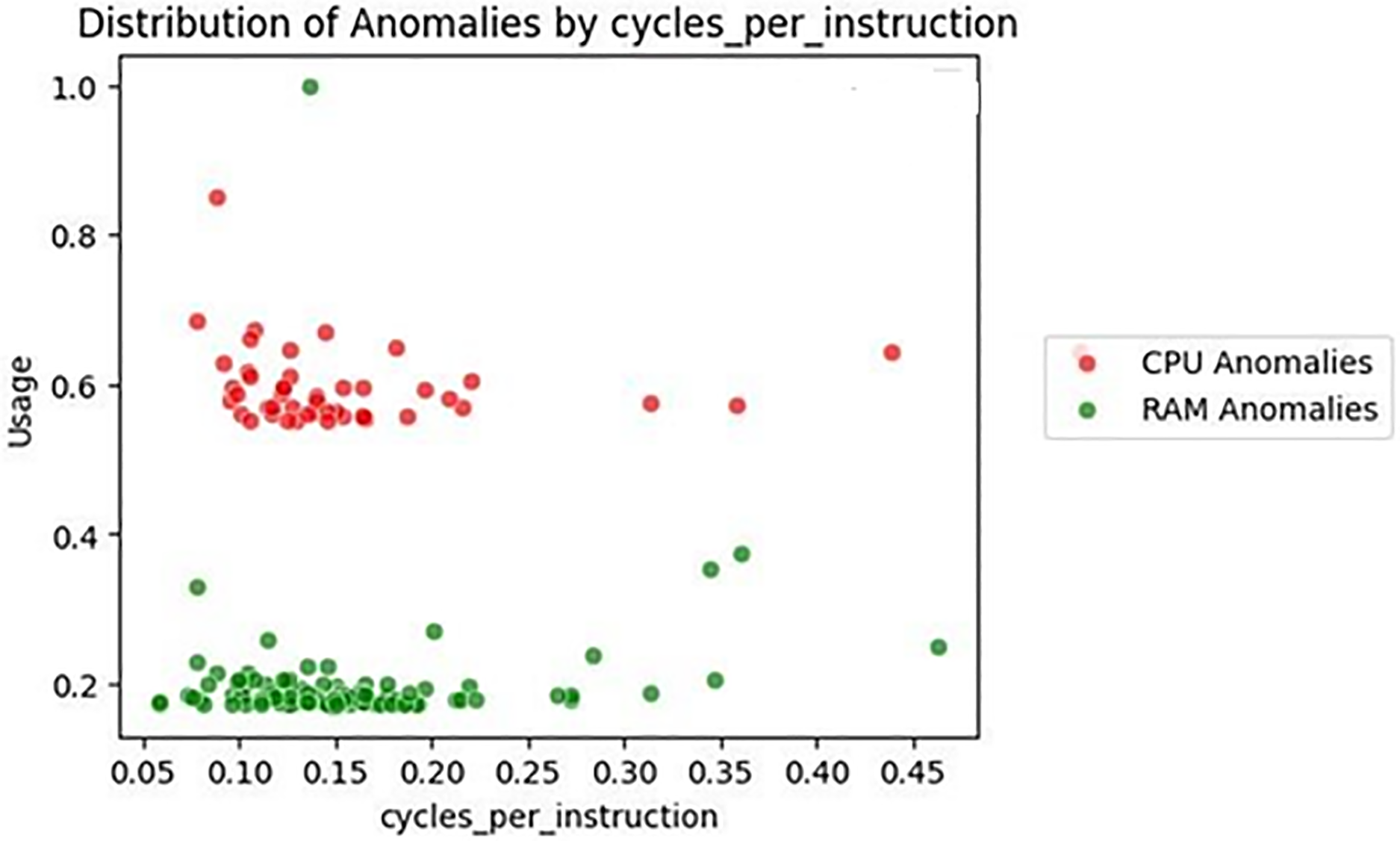

Fig. 7 displays the anomaly distribution across varying values of Cycles per Instruction. CPU anomalies (red) show a concentrated pattern around the 0.10–0.18 range, indicating that anomalies are more likely when instruction execution cycles are moderately high. Conversely, RAM anomalies (green) are more dispersed and less frequent, with no strong clustering pattern. This suggests that Cycles per Instruction is a strong indicator of CPU-specific stress, with limited relevance for RAM-related anomalies

Figure 7: Distribution of cycles per instruction anomalies

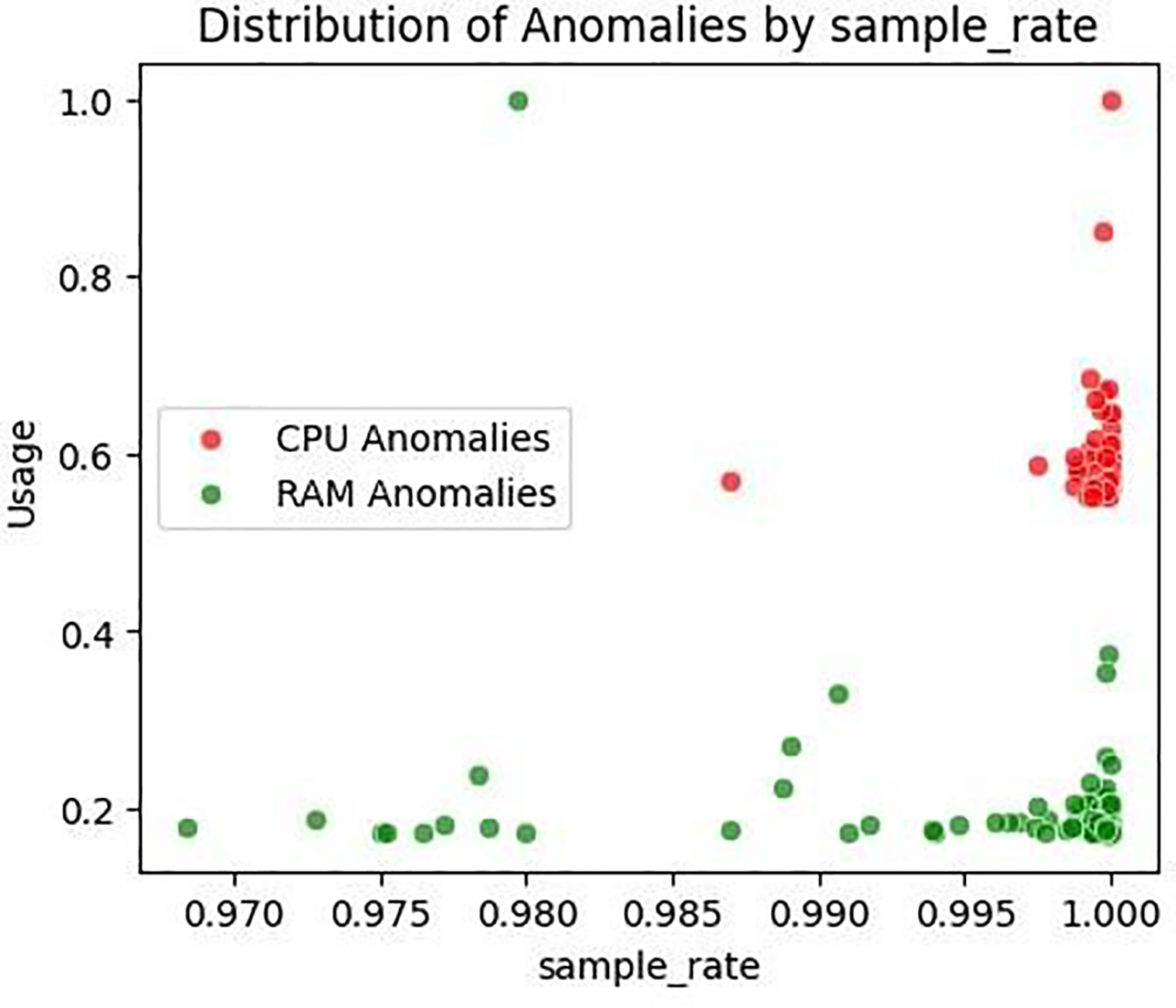

Fig. 8 shows a scatter plot of CPU and RAM anomalies in relation to Sampling Rate. A dense cluster of CPU anomalies appears at high Sampling Rate values (close to 1.0), indicating a potential trade-off between fine-grained monitoring and processor load. In contrast, RAM anomalies are more dispersed and show no strong pattern, suggesting a weaker dependency on sampling frequency.

Figure 8: Distribution of sampling rate anomalies

As shown in Fig. 9, both CPU and RAM anomalies are densely concentrated around nearzero assigned memory values. This indicates that even low memory allocation scenarios can lead to instability, possibly due to inefficient memory management or resource underprovisioning.

Figure 9: Distribution of assigned memory anomalies

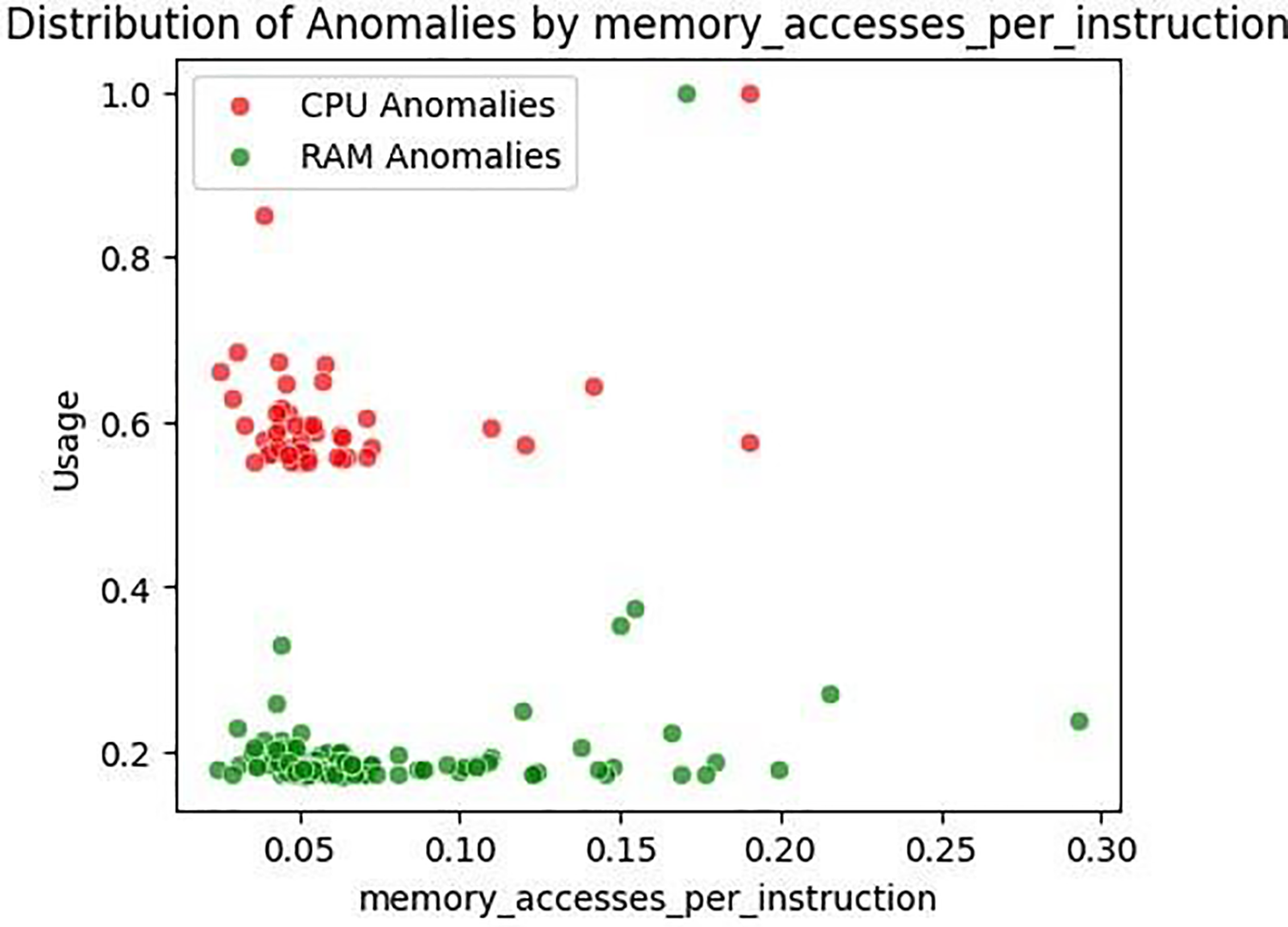

Fig. 10 demonstrates that CPU anomalies predominantly occur within mid-range values of Memory Accesses per Instruction, suggesting instruction-level memory behavior as a sensitive predictor of CPU strain. RAM anomalies, however, remain more dispersed.

Figure 10: Distribution of memory accesses per instruction anomalies

To translate these insights into a deployable mechanism, we introduce a dynamic sampling-rate controller that enhances the framework’s real-time adaptability. The controller adjusts the sampling frequency

For numerical validation, we evaluated the controller under an online prequential (test-then-train) setup with streaming updates, reflecting a real-time environment with continuous adaptation. Table 5 summarizes the online results under the proposed dynamic controller: predictive accuracy is highly stable (CPU MAE 0.01200, RMSE 0.01402; RAM MAE 0.00547, RMSE 0.00651; R2 ≈ 0.999 for both targets) while maintaining sub-millisecond update latencies (p50 = 0.100 ms, p95 = 0.200 ms, p99 = 0.300 ms; mean = 0.150 ms). Together with the UF-based triggering rates implied by the outlier frequencies in Table 4, these results constitute simulated efficacy metrics for the proposed adjustment: the controller preserves offline accuracy in an online regime and meets low-latency constraints while—by design—spending only a rare fraction of time in high-rate operation. Residual error distributions and outlier proportions are reported in Table 4. The results of the online prequential evaluation are presented in Table 5.

2.4 Analysis of High CPU and Memory Load Patterns

To further investigate the system behavior under intensive workload conditions, an in-depth analysis was conducted to identify which variables predominantly contribute to high CPU and memory usage.

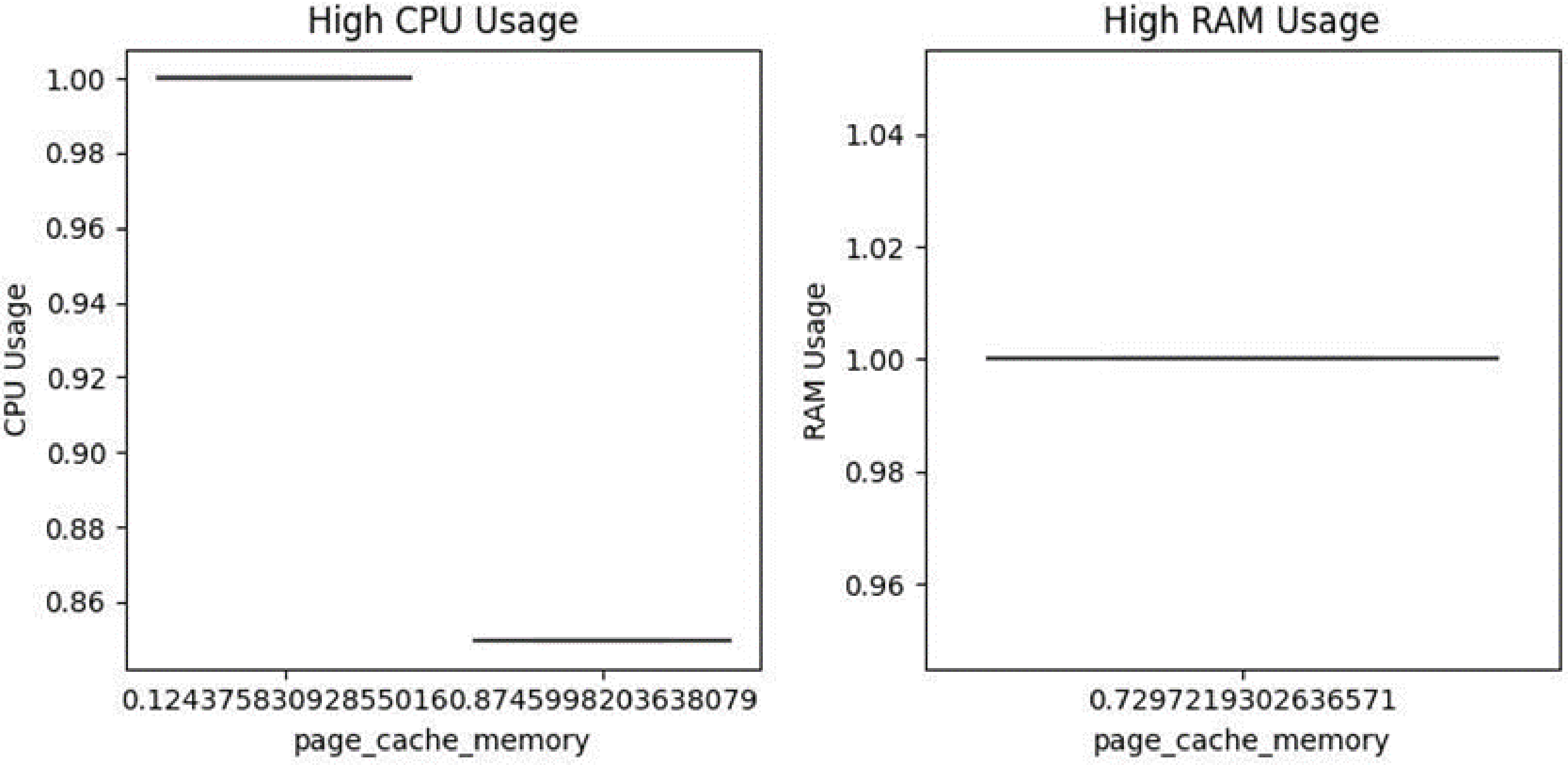

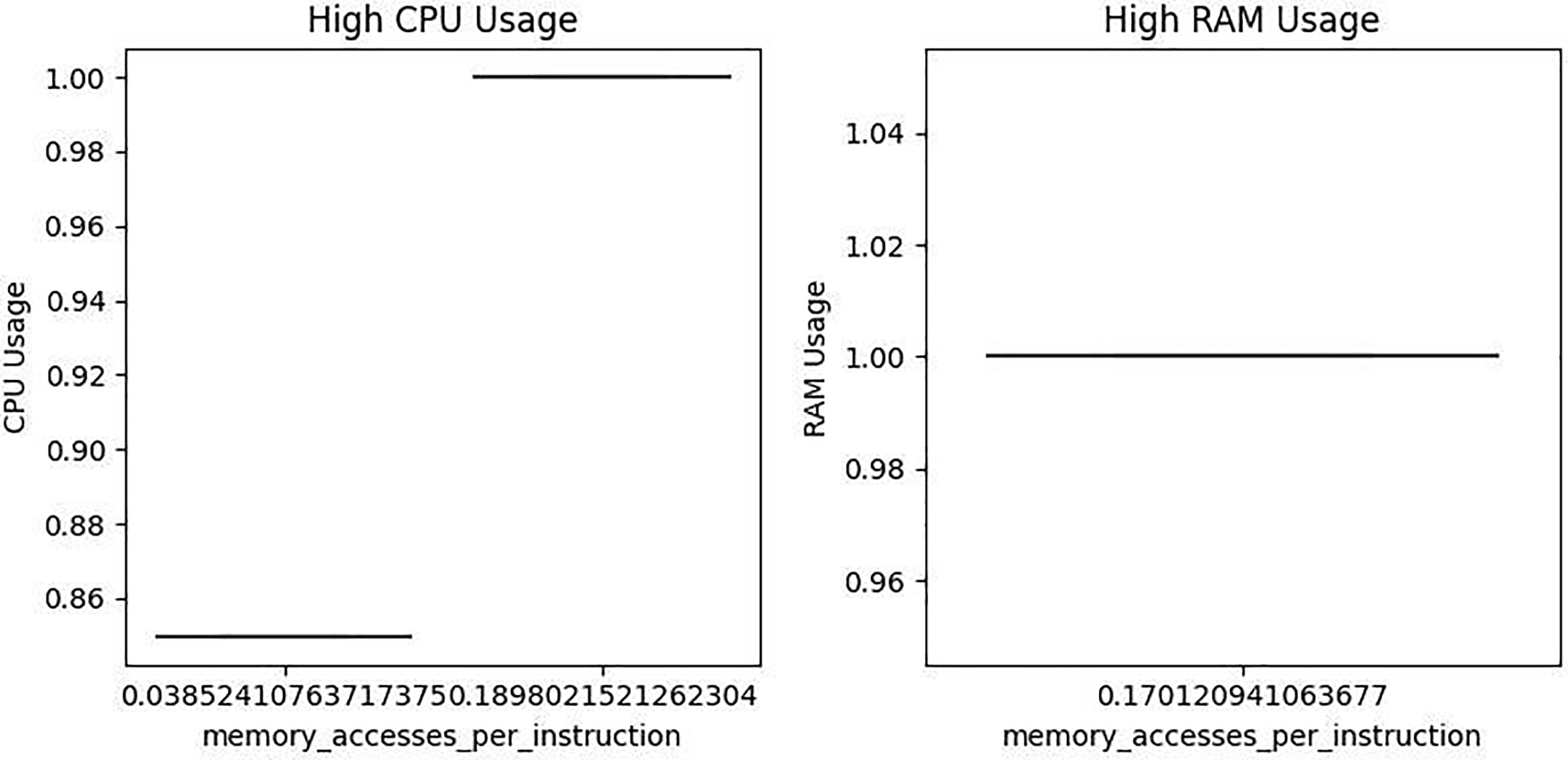

CPU Usage Findings: The features page cache memory, Cycles per Instruction, and Memory Accesses per Instruction were found to be the principal contributors to elevated CPU load. As illustrated in Figs. 11–15, data points tend to cluster at high CPU usage levels in association with these variables. Among them, page cache memory and Cycles per Instruction were particularly influential, suggesting that both caching operations and instruction execution efficiency play central roles in processor workload dynamics.

Figure 11: High CPU and memory usage caused by page cache memory

Figure 12: High CPU and memory usage caused by memory accesses per instruction

Figure 13: High CPU and memory usage caused by cycles per instruction

Figure 14: High CPU and memory usage caused by sampling rate

Figure 15: High CPU and memory usage caused by assigned memory

Memory Usage Findings: In contrast to CPU behavior, memory usage remained relatively unaffected by the same set of variables. Visual assessments (Figs. 11–15) revealed that median memory usage values remained low and stable, with no observable clustering or abrupt changes. This indicates that the analyzed parameters exert limited influence on memory consumption patterns.

These findings collectively suggest that CPU utilization is highly sensitive to specific performance-related features, whereas memory usage displays more consistent and resilient behavior across similar operational scenarios.

Visualizations Overview:

• Fig. 11: High CPU and Memory Usage Caused by page cache memory

• Fig. 12: High CPU and Memory Usage Caused by Memory Accesses per Instruction

• Fig. 13: High CPU and Memory Usage Caused by Cycles per Instruction

• Fig. 14: High CPU and Memory Usage Caused by Sampling Rate

• Fig. 15: High CPU and Memory Usage Caused by assigned memory

This multi-faceted analysis offers valuable, actionable insights for system performance optimization. By integrating feature importance evaluation, anomaly detection, and load concentration visualizations (Figs. 4–15), the study establishes a comprehensive and data-driven framework for sustainable and efficient resource management in cloud computing environments. In particular, the concentration maps in Figs. 11–15 clearly demonstrated that variables such as page cache memory, Cycles per Instruction, and Memory Accesses per Instruction play a central role in elevated CPU usage, while memory usage remains relatively unaffected by fluctuations in these metrics. This finding indicates that CPU workload is more sensitive to instruction complexity and caching behavior, whereas RAM usage follows a more stable and predictable pattern. Such differentiation is critical in designing targeted optimization strategies—for instance, focusing cache improvements and instruction efficiency enhancements specifically for CPU-intensive tasks. Ultimately, the visual evidence reinforces and complements the predictive results, offering a holistic understanding of system behavior under dynamic operational loads.

This study analyzed CPU and RAM utilization to identify factors affecting system performance, determine conditions leading to intensive workloads, and develop recommendations for performance optimization. The evaluation combined predictive modeling, feature importance analysis, anomaly detection, and continuous learning experiments to provide both descriptive and prescriptive insights.

The findings revealed that CPU usage is strongly influenced by page cache memory, cycles per instruction, and memory accesses per instruction. These variables consistently emerged as dominant predictors, confirming that caching efficiency and instruction-level operations are central drivers of processor load. In contrast, RAM usage demonstrated a more stable structure but showed dependencies on both assigned memory and page cache memory. Consistent with Table 6, removing page cache memory increases RAM prediction errors by

The predictive framework quantified these dependencies with high accuracy. Cross-validation results demonstrated reliable performance, with CPU mean absolute error around 0.010 and RAM around 0.004. Residual error analysis showed symmetric distributions with very low outlier rates (<1%), confirming that the model captured underlying dynamics without systematic bias. Importantly, regime-based evaluations indicated that CPU prediction errors increase at the highest load ranges, yet remain within practically manageable limits. This suggests that targeted optimizations, particularly in cache handling and process scheduling, can reduce the risk of performance degradation under peak stress conditions.

RAM behavior was further characterized by its association with assigned memory and irregularities in access rates. Deviations in memory accesses per instruction were linked to performance instabilities, highlighting the importance of minimizing redundant memory calls and ensuring faster access to frequently used data. These findings support the application of dynamic and demand-based RAM allocation mechanisms for improved efficiency.

Another important factor was the sampling rate. High-frequency sampling was observed to increase CPU strain, and may increase RAM usage. The online continuous learning experiments demonstrated that the proposed framework adapts in real time with sub-millisecond update latency while maintaining near-perfect predictive accuracy (R2

To contextualize performance, we compared the proposed model against a median baseline under 5-fold OOF evaluation (Table 4). Results show consistent error reductions for both CPU and RAM, confirming that the framework delivers meaningful gains over a simple baseline, particularly for RAM usage.

In summary, the results highlight the dual role of predictive modeling: identifying workload-related drivers of resource consumption and translating these findings into actionable optimization strategies. By integrating cross-validation, residual error analysis, and online adaptation, the study establishes a comprehensive and practical framework for sustainable CPU and RAM resource management.

Acknowledgement: This study was technically supported within the scope of the SAYZEK–ATP 2024–2025 program, jointly conducted by the Presidency of Defence Industries (SSB) and the Council of Higher Education (YÖK). No additional financial support was received from other public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Kadriye Simsek Alan, Ayca Durgut, Helin Doga Demirel. Methodology: Kadriye Simsek Alan, Ayca Durgut, Helin Doga Demirel. Software: Kadriye Simsek Alan, Ayca Durgut, Helin Doga Demirel. Validation: Kadriye Simsek Alan, Ayca Durgut, Helin Doga Demirel. Formal analysis: Kadriye Simsek Alan. Investigation: Kadriye Simsek Alan, Ayca Durgut, Helin Doga Demirel. Resources: Kadriye Simsek Alan, Ayca Durgut, Helin Doga Demirel. Data curation: Kadriye Simsek Alan, Ayca Durgut, Helin Doga Demirel. Writing—original draft: Kadriye Simsek Alan. Writing—review & editing: Kadriye Simsek Alan. Visualization: Ayca Durgut, Helin Doga Demirel. Supervision: Kadriye Simsek Alan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the “Google Cluster Trace 2019 v3” dataset, provided by Google Inc., at the following URL: https://github.com/google/cluster-data (accessed on 01 January 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This study does not involve human participants or animal subjects.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Glossary

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| RAM | Random Access Memory |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting algorithm |

| MOR | MultiOutputRegressor (a strategy to handle multi-target outputs) |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error (a regression evaluation metric) |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error (a regression evaluation metric) |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination (explained variance score) |

| Google Cluster Trace | A dataset of resource usage in Google’s cloud clusters |

| Feature Importance | Ranking of input variables by predictive impact |

References

1. Shaikh R, Muntean C, Gupta S. Prediction of resource utilisation in cloud computing using machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Services Science; 2024 May 2–4; Angers, France. p. 103–14. doi:10.5220/0012742200003711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zheng H, Xu K, Zhang M, Tan H, Li H. Efficient resource allocation in cloud computing environments using AI-driven predictive analytics. Appl Comput Eng. 2024;82(1):17–23. doi:10.54254/2755-2721/82/2024glg0055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ðerić N, Varasteh A, Van Bemten A, Blenk A, Kellerer W. Enabling SDN hypervisor provisioning through accurate CPU utilization prediction. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2021;18(2):1360–74. doi:10.1109/TNSM.2021.3059366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhang W, Li B, Zhao D, Gong F, Lu Q. Workload prediction for cloud cluster using a recurrent neural network. In: 2016 International Conference on Identification, Information and Knowledge in the Internet of Things (IIKI); 2016 Oct 20–21; Beijing, China. p. 104–9. doi:10.1109/IIKI.2016.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ahamed Z, Khemakhem M, Eassa F, Alsolami F, Al-Ghamdi ASA. Technical study of deep learning in cloud computing for accurate workload prediction. Electronics. 2023;12(3):650. doi:10.3390/electronics12030650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xu M, Song C, Wu H, Gill SS, Ye K, Xu C. EsDNN: deep neural network based multivariate workload prediction approach in cloud environment. arXiv:2203.02684. 2022. [Google Scholar]

7. Bi J, Li S, Yuan H, Zhou M. Integrated deep learning method for workload and resource prediction in cloud systems. Neurocomputing. 2021;424:35–48. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2020.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Girish L, Raviprakash ML. PCU-LSTM: predicting cloud CPU utilization using deep learning. NeuroQuantology. 2022;20(22):2061–9. doi:10.48047/nq.2022.20.22.NQ10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Al-Asaly MS, Bencherif MA, Alsanad A, Hassan MM. A deep learning-based resource usage prediction model for resource provisioning in an autonomic cloud computing environment. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(13):10211–28. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06665-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lekkala C. AI-driven dynamic resource allocation in cloud computing: predictive models and real-time optimization. J Artif Intell Mach Learn Data Sci. 2024;2:450–6. doi:10.51219/JAIMLD/chandrakanth-lekkala/124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Khan T, Tian W, Ilager S, Buyya R. Workload forecasting and energy state estimation in cloud data centres: mL-centric approach. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2022;128:320–32. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.10.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wen Y, Wang Y, Liu J, Cao B, Fu Q. CPU usage prediction for cloud resource provisioning based on deep belief network and particle swarm optimization. Concurr Comput Pract Exp. 2020;32(14):e5730. doi:10.1002/cpe.5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Devi KL, Valli S. Time series-based workload prediction using the statistical hybrid model for the cloud environment. Computing. 2023;105(2):353–74. doi:10.1007/s00607-022-01129-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Malik S, Tahir M, Sardaraz M, Alourani A. A resource utilization prediction model for cloud data centers using evolutionary algorithms and machine learning techniques. Appl Sci. 2022;12(4):2160. doi:10.3390/app12042160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Setayesh A, Hadian H, Prodan R. An efficient online prediction of host workloads using pruned GRU neural nets. arXiv:2303.16601. 2023. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang H, Mathews KJ, Golec M, Gill SS, Uhlig S. AmazonAICloud: proactive resource allocation using Amazon chronos based time series model for sustainable cloud computing. Computing. 2025;107(3):77. doi:10.1007/s00607-025-01435-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dittakavi RSS. Deep learning-based prediction of CPU and memory consumption for cost-efficient cloud resource allocation. Sage Sci Rev Appl Mach Learn. 2021;3(1):45–58. [Google Scholar]

18. Quoc KN, Tong V, Dao C, Le TN, Tran D. Boosted regression for predicting CPU utilization in the cloud with periodicity. J Supercomput. 2024;80(18):26036–60. doi:10.1007/s11227-024-06451-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rossi A, Visentin A, Carraro D, Prestwich S, Brown KN. Forecasting workload in cloud computing: towards uncertainty-aware predictions and transfer learning. Clust Comput. 2025;28(4):258. doi:10.1007/s10586-024-04933-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sireesha P, Vishnu Priyan S, Govindarajan M, Rajan S, Rajakumareswaran V. Revolutionizing cloud resource allocation: harnessing layer-optimized long short-term memory for energy-efficient predictive resource management. EAI Endorsed Trans Energy Web. 2024;11. doi:10.4108/ew.6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools