Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Lightweight and Optimized YOLO-Lite Model for Camellia oleifera Leaf Disease Recognition

1 College of Computer and Mathematics, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, 410000, China

2 College of Aeronautical Engineering, Hunan Automotive Engineering Vocational University, Zhuzhou, 412000, China

* Corresponding Author: Xu-Yu Xiang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Artificial Intelligence for Engineering and Sciences)

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 437-450. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.072332

Received 24 August 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 20 October 2025

Abstract

Camellia oleifera is one of the four largest oil tree species in the world, and also an important economic crop in China, which has overwhelming economic benefits. However, Camellia oleifera is invaded by various diseases during its growth process, which leads to yield reduction and profit damage. To address this problem and ensure the healthy growth of Camellia oleifera, the purpose of this study is to apply the lightweight network to the identification and detection of camellia oleifolia leaf disease. The attention mechanism was combined for highlighting the local features and improve the attention of the model to the key areas of Camellia oleifera disease images. To prove the recognition of the optimized network on Camellia oleifera leaf disease, we tested the network performance of the optimized model with other object detection algorithms such as YOLOV5s, SSD, Faster-RCNN, YOLOv8, and YOLOv10. The results show that the mAP, recall, and accuracy of the trained network achieved 82.9%, 75.7% and 80.6%, respectively. The optimized YOLO-Lite model has the advantages of small size and few parameters while ensuring high accuracy, thus it has a satisfactory effect on leaf disease identification of Camellia oleifera.Keywords

Camellia oleifera is one of the four largest oil tree species in the world and an important economic crop in China with significant economic benefits. However, Camellia oleifera is susceptible to various diseases during its growth process, which leads to yield reduction and economic losses in the Camellia oleifera industry [1]. Traditional diagnostic methods rely on consulting books, online resources, and experienced experts. These methods suffer from low efficiency and excessive subjectivity [2]. Therefore, automatic detection of diseased leaves is beneficial for the cultivation and management of Camellia oleifera, bringing substantial economic gains. This technology can not only provide early, effective treatment for Camellia oleifera leaf diseases but also reduce environmental harm caused by excessive pesticide use [3].

With the continuous advancement of computer vision, image processing technology has developed rapidly and found applications in multiple fields [4]. Object detection technology has a significant impact on the timely detection and control of agricultural pests and diseases [5]. Agricultural intelligent technology has transformed the inefficiency of traditional methods, profoundly impacting agricultural research and production. Object detection techniques can be generally divided into two categories: one-stage and two-stage algorithms. Two-stage algorithms are mainly represented by RCNN [6] and its variants, including Faster-RCNN. These algorithms first extract candidate boxes from input images, then perform object classification and location regression. Although they achieve satisfactory detection accuracy, their speed requires improvement. One-stage algorithms do not need to generate candidate boxes, directly using CNN for feature extraction and performing object classification and location regression simultaneously. SSD [7] and YOLO series [8] are representative algorithms with lower computational requirements and stronger real-time performance, better meeting real-time object detection requirements.

Traditional CNNs have limitations such as complex structures, large parameters, and high computational demands, making them difficult to deploy on embedded or mobile devices for practical applications. To address these issues, we propose a lightweight CNN with a simple network structure, fewer parameters, fast identification speed, and mobile deployment capability. Considering complex backgrounds and uneven lighting conditions, we employ Mosaic data augmentation and integrate channel attention mechanisms to improve model detection performance, enabling deployment on embedded devices and mobile equipment for real-world applications.

Recent advances in computer vision have greatly benefited crop disease recognition and detection through image processing technology. Paymode et al. [9] focused on crop disease identification, collecting leaf images from mobile devices and organizing them into datasets. Their CNN model achieved 97% accuracy in detecting early-stage diseases across six different crops. Dwivedi et al. [10] developed a scheme for grape disease prevention and control, employing dual attention mechanisms to detect various grape diseases with remarkable results, achieving approximately 99.93% accuracy. Zhou et al. [11] designed a recognition network for tomato disease detection, achieving high-precision results. Akshai and Anitha [12] conducted extensive work on early crop disease identification to ensure crop yields and food security, using datasets containing over 50,000 images of various crops. After comparison, DenseNet achieved 98.27% accuracy.

The YOLO algorithm has significantly impacted crop disease identification. Qi et al. [13] developed the SE-YOLOv5 model with visual attention mechanisms, achieving 94.10% accuracy in tomato disease recognition experiments. Chen et al. [14] applied YOLOv5 to rubber tree disease detection, incorporating SE modules for improved performance. Karegowda et al. [15] researched tomato disease detection using YOLO, achieving over 97% accuracy with reduced computation time compared to Faster R-CNN. Lightweight networks like MobileNet [16] and ShuffleNet [17] have attracted increasing attention due to their compact models and faster processing speeds. Wang et al. [18] applied lightweight YOLOv5 for plant disease classification, incorporating attention mechanisms and achieving 92.57% classification accuracy. Recent YOLO developments have shown remarkable progress with improved architectures and training strategies.

In our work, we proposed a lightweight network to solve the problem of rapid detection of Camellia oleifera leaf disease. In order to highlight the useful information in the image, we have added the attention mechanism in YOLO-Lite. The result shows that the optimized network achieves fast detection speed and high accuracy when compared to the competing algorithms.

3.1.1 Disease Categories and Characteristics

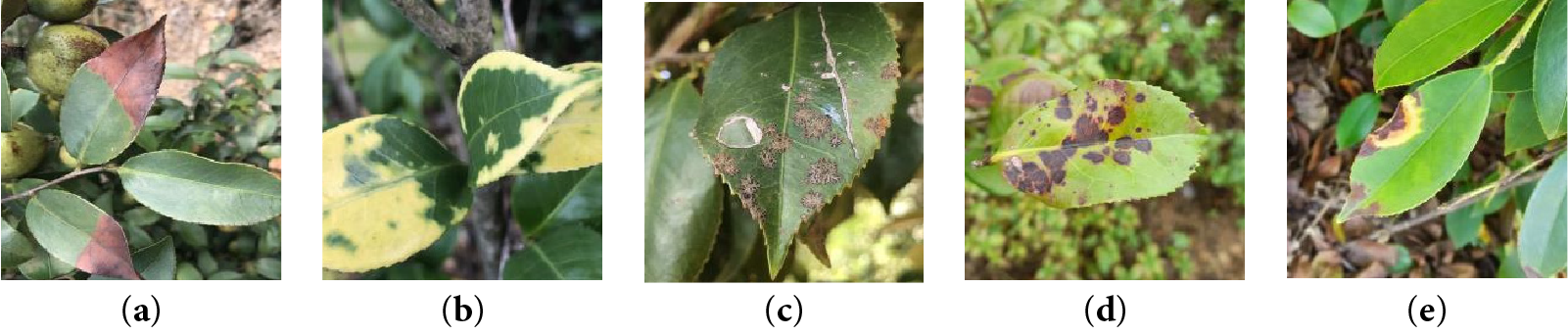

The object of this paper is identification of leaf disease of Camellia oleifera. Among the leaf diseases of Camellia oleifera, Phyllosticta theicola, palm Yellow leaf disease, Cephaleuros virescens, Cercosporella theae and Agaricodochium camellia are the most common diseases of Camellia oleifera. The characteristics of Camellia oleifera disease are shown in Fig. 1, and the related symptoms are described in Table 1:

Figure 1: Example of common Camellia oleifera disease images. (a): Phyllosticta theicola, (b): palm Yellow leaf disease, (c): Cephaleuros virescens, (d): Cercosporella theae, (e): Agaricodochium camellia

In this paper, we collected 2093 diseased leaf images of Camellia oleifera through field photography, and image acquisition was completed through multiple shots. And all the disease images were shot in complex natural scenes, and were taken in multiple periods of the day. The dataset is composed of five common Camellia oleifera diseases, including Phyllosticta theicola, palm Yellow leaf disease, Cephaleuros virescens, Cercosporella theae, and Agaricodochium camellia. Using the LabelImg tool to annotate the leaf diseases in images, and the annotation information was saved as a TXT file in Yolo format. Each line of the file had five values. The Camellia oleifera dataset was randomly divided into a 70% training set, 15% verification set, and 15% testing set.

In practical application, the proposed detection model of Camellia oleifera leaf disease should meet the following requirements:

1. Realize efficient detection of Camellia oleifera leaf disease: Considering the actual requirements of outdoor detection tasks, how to improve the detection speed of disease images and realize the rapid diagnosis of the disease leaves of Camellia oleifera leaf disease are the key detection work.

2. Implement an embeddable lightweight model. In order to improve users’ sense of use and meet their actual usage scenarios, the network must be applied to the mobile terminal to avoid excessive power consumption.

In order to meet the above requirements, this paper improved the backbone network of the lightweight network YOLO-Lite and proposed shuffle attention block (SFAB) to replace shuffle block in the backbone network.

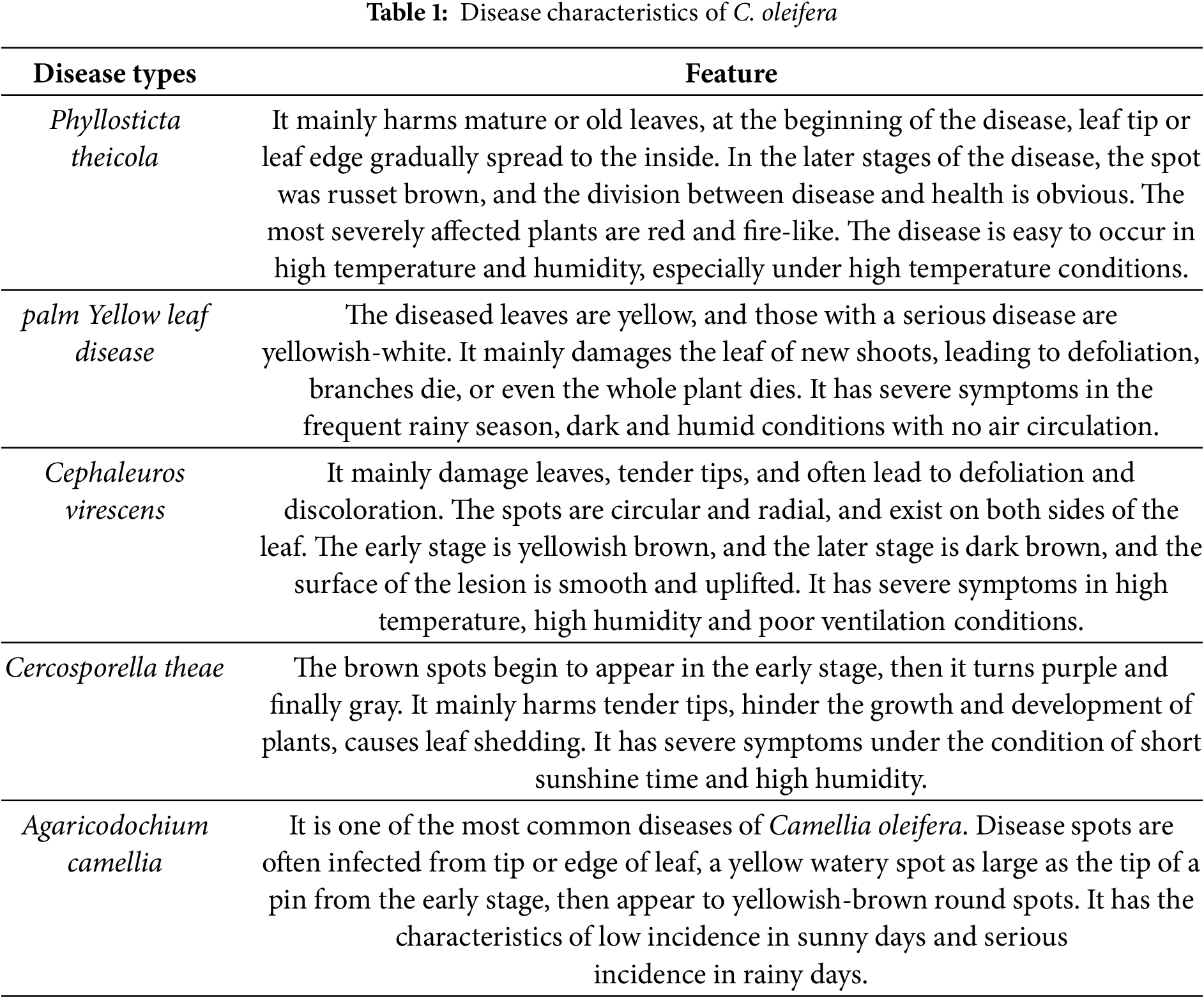

The overall structure of the model for detecting diseased leaves of Camellia oleifera proposed in this paper is shown in Fig. 2. It is mainly divided into Backbone, Neck, and Precision.

Figure 2: Improved YOLO-Lite network

Let the input terminal input picture of Camellia oleifera diseased leaves, as

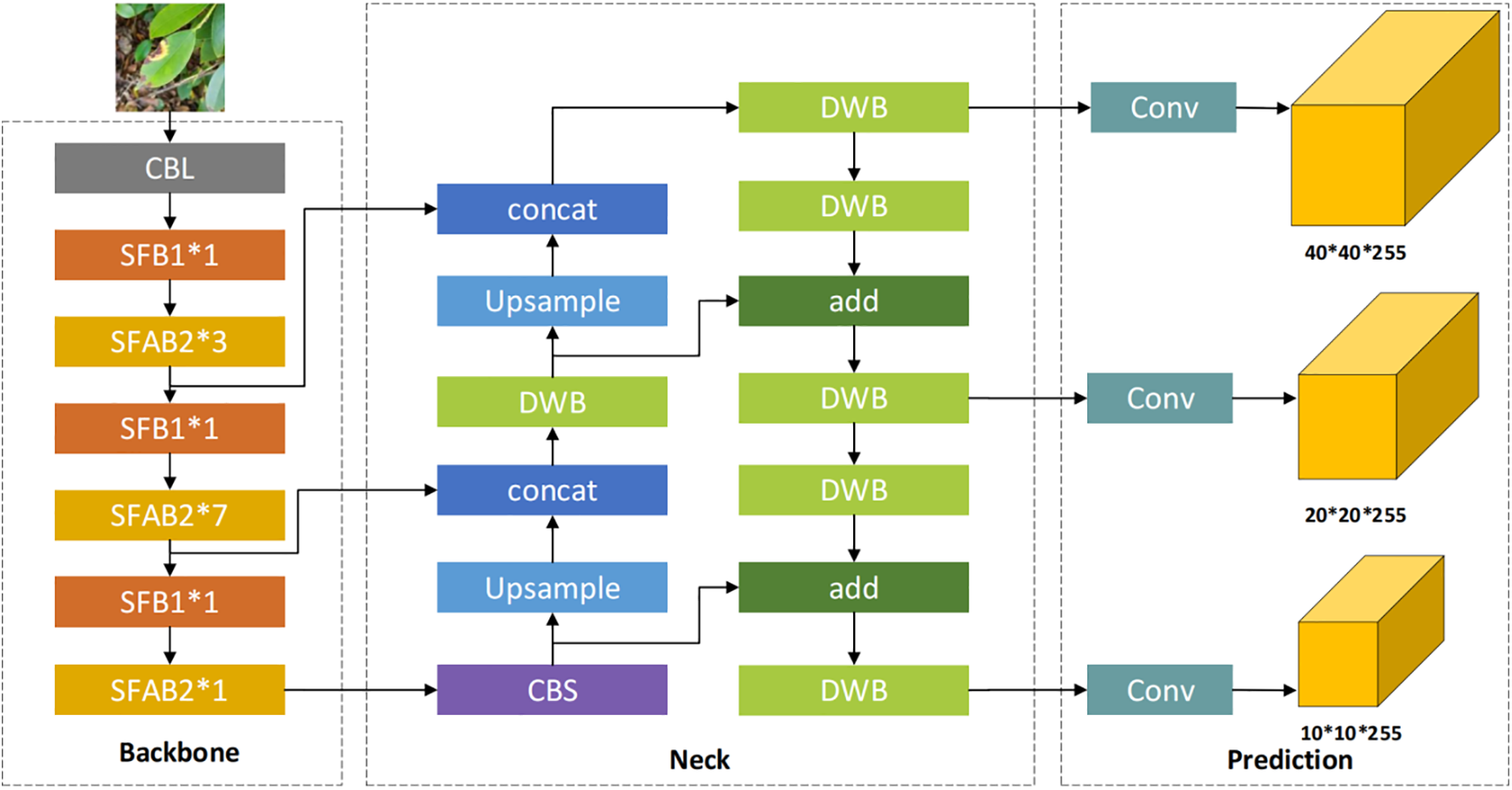

Backbone removes the Focus layer in YOLOv5 and adopts ShuffleNet v2 [19] structure (Fig. 3). ShuffleNet v2 proposes the Channel Split operation based on ShuffleNet v1.

Figure 3: (a,b) are ShuffleNet v1 modules with different structures, where (b) with spatial down sampling structure. (c,d) are ShuffleNet v2 modules with different structures, where (d) with spatial down sampling

ShuffleNet v2 puts forward four design principles for a lightweight network:

(1) To minimize MAC, keep the number of input and output channels as similar as possible.

(2) Too much Group Convolution will increase MAC.

(3) Fragmentation operations are not friendly to parallel acceleration.

(4) The memory and time consumption generated by Element-Wise operations such as Shortcut and Add cannot be ignored.

Therefore, the YOLO-Lite complies with the above guidelines and makes the following improvements based on Yolov5:

Firstly, remove the Focus layer to reduce the computational burden by avoiding multiple slice operations. Secondly, avoid frequent use of C3 Leyer and high channel C3 Layer. Because C3 Layer adopts multi-channel separated convolution, this will reduce the running speed of too much use. Thirdly, channel pruning is performed on YoloV5 head. Fourth, 1024 CONV and 5 × 5 pooling of the ShuffleNet v2 backbone are removed.

The neck structure includes FPN [13] and PAN [20], which are mainly used to extract image features [21]. The FPN layer conveys high-level features from bottom to top, and the PAN layer conveys the positioning information of the lower layers from the bottom up, so as to integrate high-level features with low-level features better.

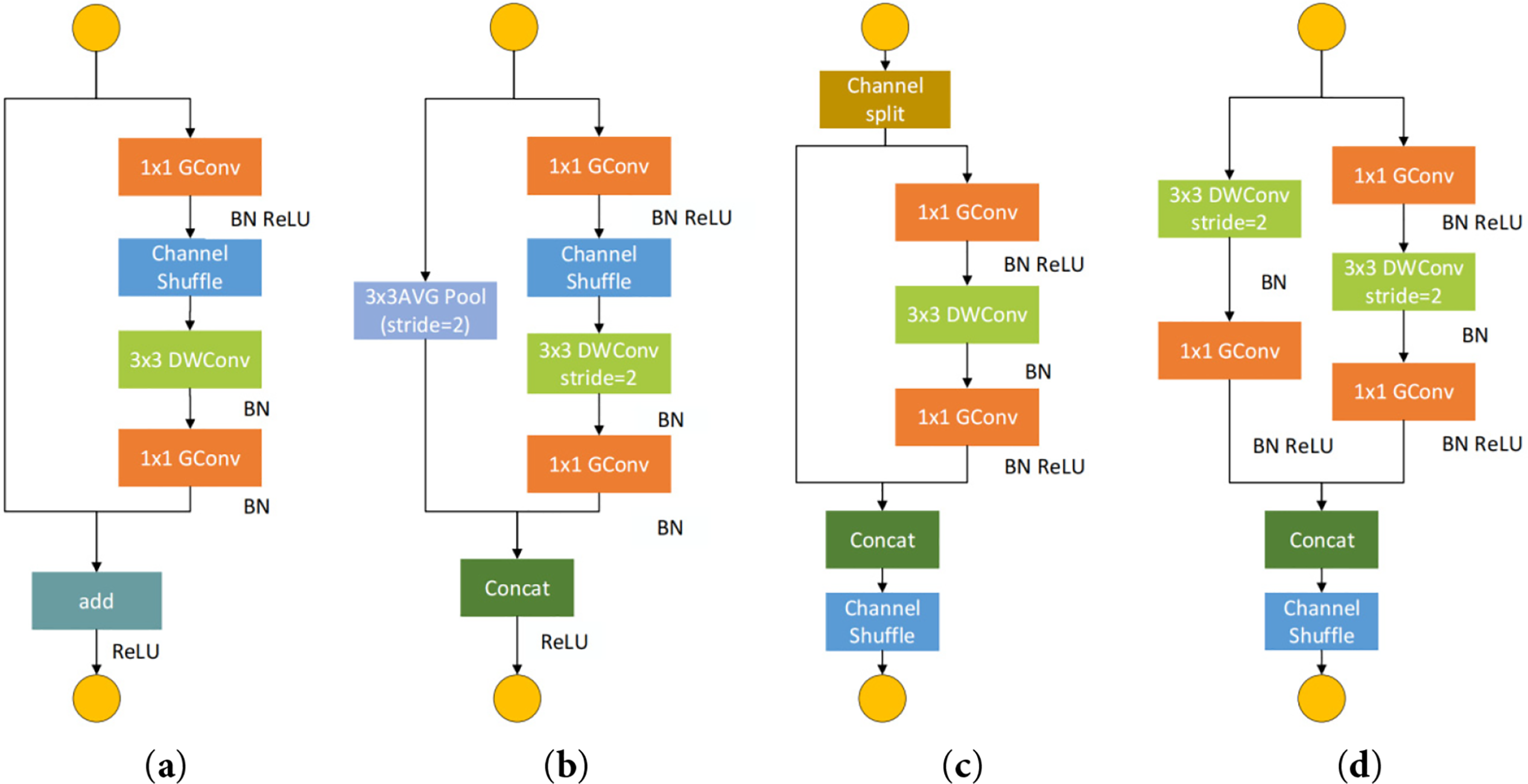

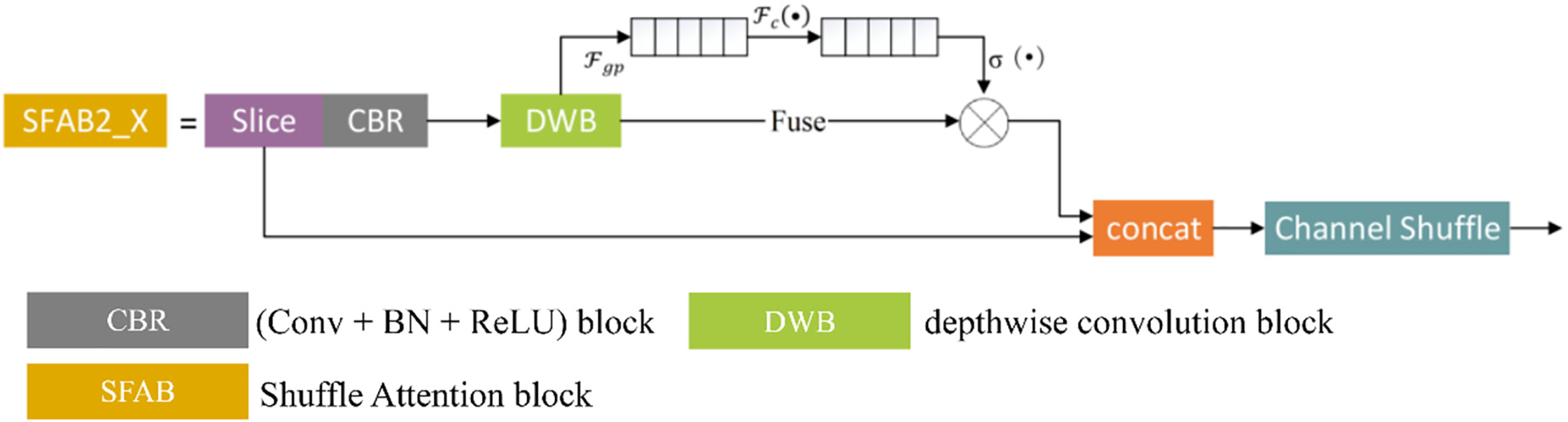

3.2.2 Shuffle Attention Block (SFAB)

To enhance feature discriminability in agricultural vision tasks while preserving lightweight properties, this study introduces an improved Shuffle Attention Block, denoted as SFAB2_X. Its structural design is illustrated in Fig. 4 where the main components include Slice CBR (Conv + BN + ReLU) DWB (Depthwise Conv + BN) Channel Attention and Channel Shuffle (CS).

Figure 4: The SFAB2_X unit structure

Let the input feature map be

To further enhance discriminative capability, a channel attention mechanism is embedded in the first branch. After obtaining

Subsequently, a single fully connected (FC) layer is used to generate channel-wise attention weights:

where

where ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication.

Finally, the recalibrated feature

The figure illustrates the overall workflow of the proposed Shuffle Attention Block (SFAB2_X). The input feature map is first divided into two equal channel groups by the Slice operation. The first branch processes the feature subset through a CBR (Conv + BN + ReLU) block and a depthwise convolution block (DWB), followed by an embedded channel attention mechanism that adaptively recalibrates channel responses. The second branch applies a standard convolution to retain original feature representations. The outputs from both branches are concatenated and subsequently subjected to a Channel Shuffle (CS) operation, which enables cross-branch information exchange and alleviates channel independence. This design ensures efficient feature extraction with improved discriminability while maintaining a lightweight structure suitable for deployment in compact detection models.

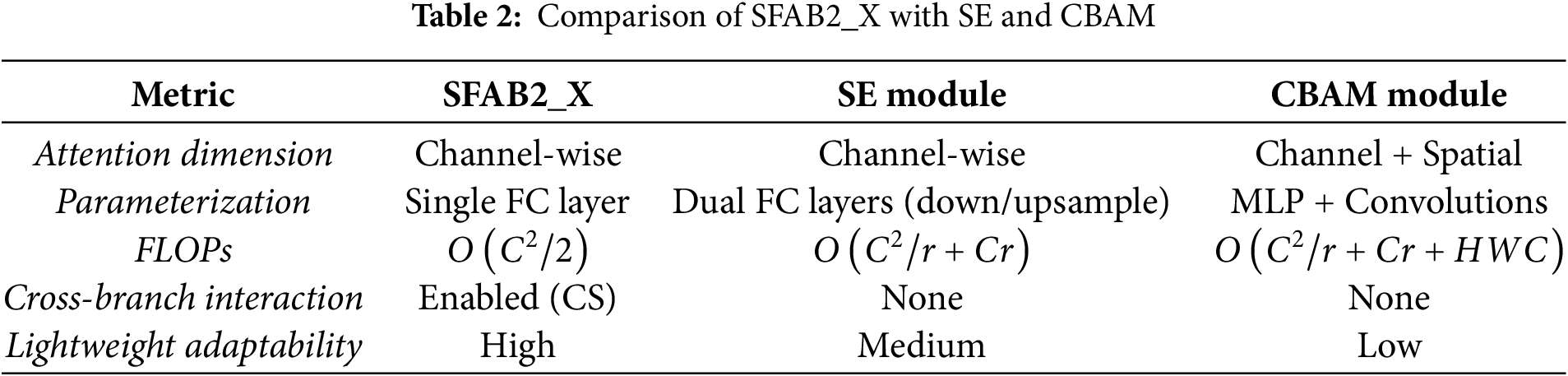

Compared with existing attention modules SFAB2_X exhibits several key differences. As summarized in Table 2, unlike the Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block which employs two fully connected layers with a reduction ratio SFAB2_X adopts a single FC layer, thereby reducing parameters by approximately 20%–30%. In addition, while both SE and CBAM modules lack cross-branch interaction, the channel shuffle operation in SFAB2_X explicitly addresses this issue, enabling effective feature exchange across channels. Moreover, compared with CBAM, which integrates both channel and spatial attention at the cost of increased FLOPs

In summary, SFAB2_X achieves enhanced feature discriminability through branch-wise processing and channel recalibration while maintaining low parameter and computational overhead. Its design demonstrates clear advantages over conventional SE and CBAM modules, especially for lightweight agricultural vision applications.

The development platform for this study is PyCharm 2021. The experimental environment is based on PyTorch 1.11.0 with Python 3.7. The hardware configuration includes an Intel Core i5-12600KF CPU @ 3.70 GHz, 16 GB of memory, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080Ti GPU. For model training, we adopt the Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) optimizer and weight decay of 0.0005. The initial learning rate is set to 0.01 and adjusted using a cosine annealing schedule throughout the training process. The batch size is fixed at 32, and the total number of training epochs is 200 to ensure convergence. Data augmentation strategies include random horizontal flipping, random scaling, mosaic augmentation, and color jittering, which are applied to enhance the generalization ability of the model in complex agricultural scenes.

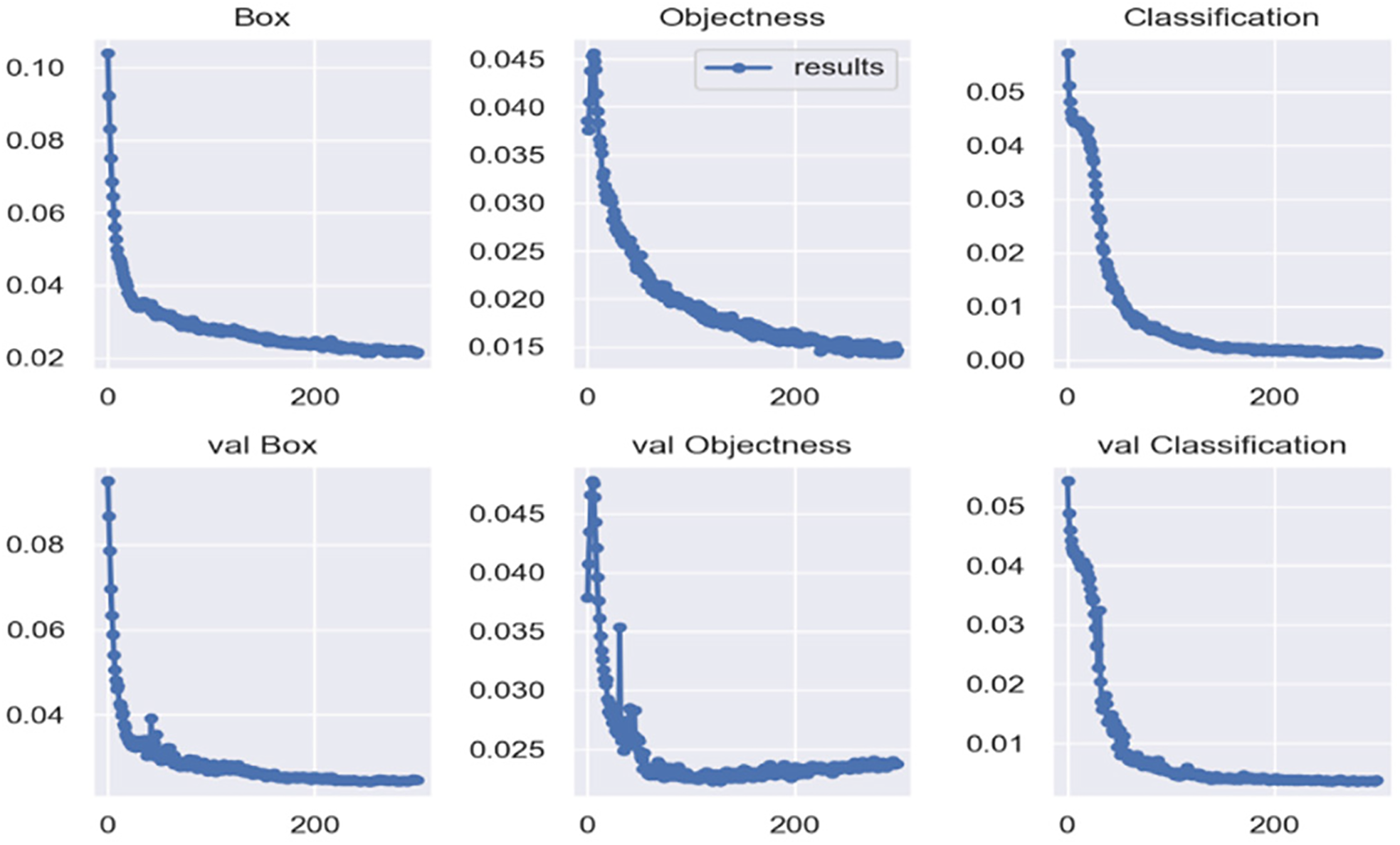

Fig. 5 shows the loss values for different components during training, including Box Loss, Objectness Loss, and Classification Loss, along with their corresponding validation losses (val Box, val Objectness, and val Classification). From 0 to 100 epochs, the loss values decline rapidly, and they stabilize around 200 epochs, indicating that the model converges quickly in the early stages and stabilizes later on.

Figure 5: Graphs of training and validation sets loss functions

Each subgraph follows a similar trend, with a rapid decrease in loss during the first 100 epochs, followed by gradual stabilization. This suggests that the model learns the key features for each task quickly, especially in terms of Box and Objectness prediction, where the optimization process is efficient. The classification loss shows a similar decline, indicating that the model also stabilizes and improves its accuracy in predicting object classes.

Overall, the stabilization of the loss values indicates that the model effectively learns the key features for the object detection task during training and generalizes well to the validation set. The rapid convergence and subsequent stabilization suggest that the model reaches an ideal balance during training, with no signs of overfitting or non-convergence in the later stages.

The following are the evaluation indicators of the leaf diseases detection model of C. oleifera.

(1) Precision: represents the proportion of the prediction of a class that actually belongs to that class.

(2) Recall: represents the proportion of the number that actually belongs to this category to the total number of this category.

(3) Intersection over Union (IoU): IoU measures the spatial overlap accuracy between predicted and ground truth segmentation masks for each class:

(4) mAP: represents the mean of the average Precision for all prediction categories.

where TP is true positive, FP is false positive and FN is false negative.

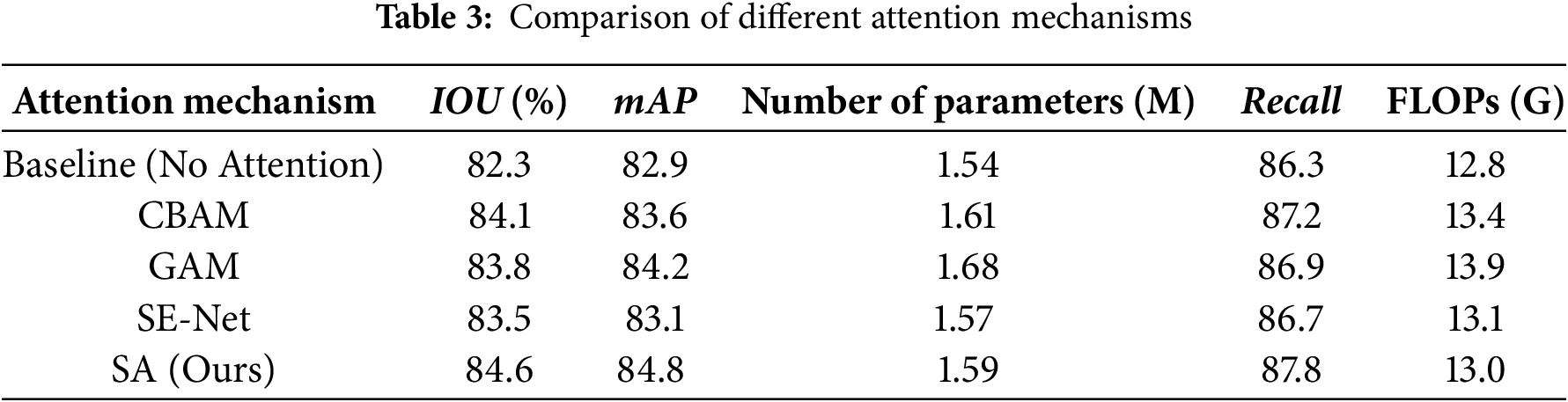

4.1 Attention Mechanism Evaluation

Table 3 presents a comprehensive comparison of different attention mechanisms integrated into our baseline model. The proposed SA (Spatial Attention) module demonstrates superior performance across all key metrics, achieving the highest IoU of 84.6% and mAP of 84.8%, representing improvements of 2.3% and 1.9% respectively, over the baseline (82.3% IoU, 82.9% mAP). SA also achieves the best recall rate of 87.8%, surpassing CBAM (87.2%), GAM (86.9%), and SE-Net (86.7%), which indicates an enhanced capability in accurately detecting agricultural field boundaries.

In terms of computational efficiency, SA maintains a lightweight design with only 1.59 M parameters and 13.0 G FLOPs, which is slightly lower than CBAM (1.61 M, 13.4 G) and GAM (1.68 M, 13.9 G), and comparable to SE-Net (1.57 M, 13.1 G). This demonstrates that SA not only improves accuracy but also avoids introducing significant computational overhead.

It is worth noting that while SA achieves consistent gains in IoU and mAP, the recall values across different modules exhibit slight fluctuations. This reflects the inherent precision–recall trade-off: optimization of attention modules tends to enhance precision (fewer false positives) at the potential expense of recall (increased false negatives). In our case, SA mitigates this trade-off effectively by reaching the highest recall (87.8%) among all compared modules, demonstrating its balanced performance.

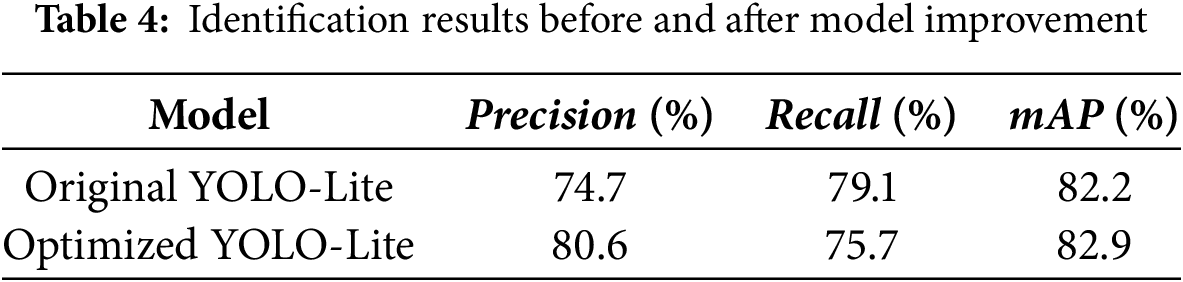

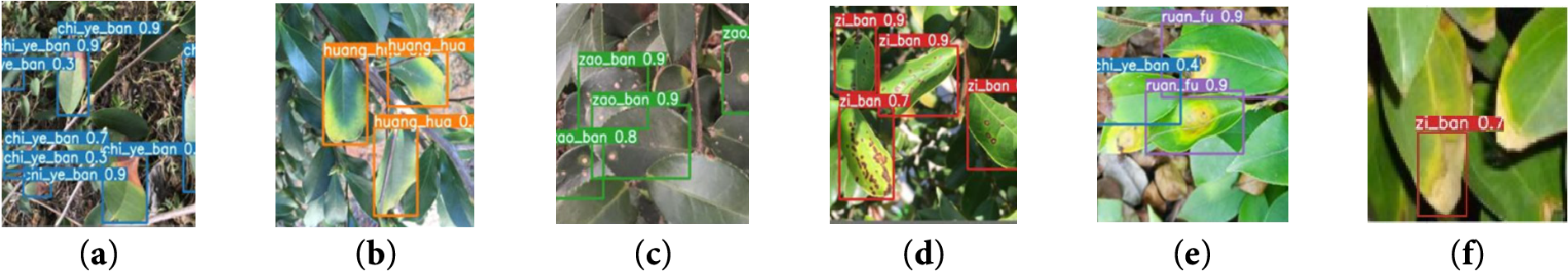

In this section, we further analyze the recognition results of the model on the test set images. Statistical analysis of detection results of five diseases is shown in Table 4 and Fig. 6:

Figure 6: The recognition results of the Optimized YOLO-Lite. (a): Phyllosticta theicola, (b): palm Yellow leaf disease, (c): Cephaleuros virescens, (d): Cercosporella theae, (e): Agaricodochium camellia, (f): failure cases

Recognition results of the original YOLO-Lite and optimized YOLO-Lite are shown in Table 4, which indicate that the precision, recall, and mAP of the original YOLO-Lite were 74.7%, 79.1% and 82.2%, respectively. For improved YOLO-Lite, the recognition results were 80.6%, 89.32%, 75.7% and 82.9%, respectively. Overall, the effect of the optimized YOLO-Lite is better than that of the original YOLO-Lite, the precision of disease identification increased by 5.9% and the average precision increased by 0.7%. At the same time, recall decreased by 3.4%. In summary, compared to the previous network, the performance of the optimized YOLO-Lite has been greatly enhanced.

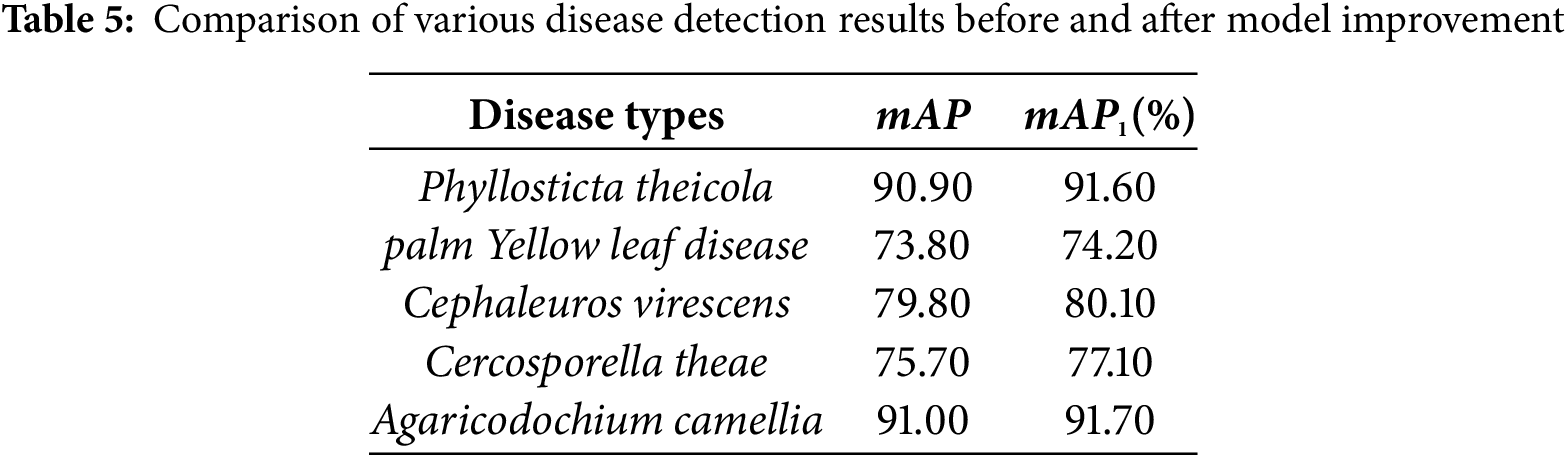

The disease detection results of five kinds of Camellia oleifera diseases are shown in Table 5, where mAP and mAP1 represent the recognition results before and after the improvement of YOLO-Lite, respectively. The results demonstrate that the optimized model achieves consistent performance gains across all disease types. In particular, Phyllosticta theicola and Agaricodochium camellia exhibit clear improvements of 0.70% while Cephaleuros virescens achieves a gain of 0.30%. The most notable enhancement is observed in Cercosporella theae, where the mAP increases by 1.40%, indicating that the improved network effectively strengthens feature representation for relatively difficult-to-detect lesions.

These improvements highlight the enhanced feature extraction capability of the optimized model, which enables more accurate localization of disease symptoms, especially in the case of small-scale lesions and early-stage infections. Furthermore, the robustness of the model is validated by its stable performance across different lighting conditions and leaf orientations, as evidenced by the consistent detection accuracy across the diverse test samples illustrated in Fig. 6. To provide more informative insights, Fig. 6 also reports the bounding box confidence levels, which further demonstrate the model’s ability to assign high confidence scores to true positive detections while maintaining low scores for background regions. In addition, representative failure cases were also proposed, such as the detection of visually similar erroneous disease symptoms, which revealed the limitations of the current model. These cases suggest potential directions for further improvement, such as incorporating occlusion-aware data augmentation or refining the loss function to better handle ambiguous samples.

4.3 Comparison of the Recognition Results of the Our Object Detection Algorithms

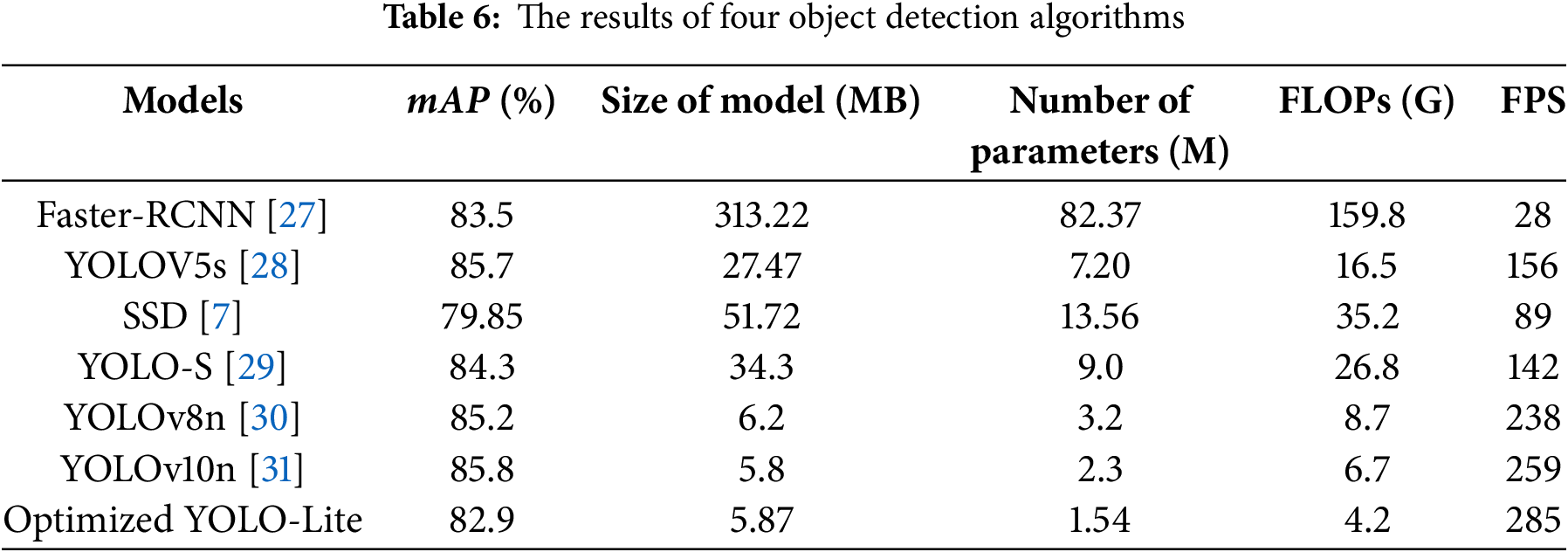

In order to verify the effectiveness of the improved Yolov5 Lite model, we compared the performance of the proposed model with the classical algorithms on the same dataset. Recent advances in agricultural object detection have shown promising results. Zhang et al. [21] enhanced apple detection using lightweight YOLOv4, while Tang et al. [16] specifically addressed Camellia oleifera fruit recognition challenges. Yu et al. [22] developed fruit detection systems for strawberry harvesting robots, and applied transfer learning to Camellia oleifera disease recognition. Mobile deployment considerations have been addressed by Li et al. [23], who focused on agricultural pest detection on mobile devices. Lightweight architectures like MobileNets [19,24] have been widely adopted for mobile applications. Attention mechanisms have proven effective in agricultural vision tasks CBAM [25] and SE-Net [26] have been successfully integrated into detection frameworks to improve feature representation capabilities. Table 6 shows the data statistics. In order to verify the effectiveness of the improved Yolov5 Lite model, Building upon these foundations, our approach introduces several key innovations: (1) an enhanced backbone network that balances detection accuracy with computational efficiency, (2) an improved feature fusion mechanism that better captures multi-scale disease characteristics, and (3) optimized anchor strategies specifically designed for small-scale leaf disease detection. The integration of these components addresses the unique challenges in Camellia oleifera disease recognition, including variable disease symptom sizes, complex background interference, and the need for real-time processing in field conditions. Our experimental validation encompasses both controlled laboratory conditions and real-world field scenarios to ensure practical applicability.

According to Table 6, our optimized YOLO-Lite demonstrates exceptional efficiency advantages. Compared with Faster-RCNN, the number of parameters is reduced by 98.13% (from 82.37 M to 1.54 M), while the accuracy loss is only 0.6% (from 83.5% to 82.9%). The model size is also dramatically reduced by 98.13% (from 313.22 to 5.87 MB).

When compared with other lightweight models, our approach maintains competitive performance: the model size is only 21.4% of YOLOv5s and 11.3% of SSD, and it achieves the highest inference speed of 285 FPS, which is 83% faster than YOLOv5s (156 FPS) and 220% faster than SSD (89 FPS). Furthermore, compared with the latest YOLO series, our model achieves the smallest parameter count (1.54 M vs. 3.2 M for YOLOv8n and 2.3 M for YOLOv10n) and the highest inference speed (285 FPS vs. 238 FPS for YOLOv8n and 259 FPS for YOLOv10n), while maintaining reasonable accuracy for practical agricultural applications.

To further strengthen the reliability of the results, we conducted experiments across five independent runs and report the mean and variance of mAP and recall values. The variance of mAP for YOLO-Lite is within ±0.3%, indicating stable convergence and reproducibility of the proposed method. In addition, we performed paired t-tests between YOLO-Lite and competing models, which confirmed that the improvements in inference speed and parameter efficiency are statistically significant (p < 0.05).

We also compared our method with recent state-of-the-art detectors, including YOLOv7 [32] and YOLOv8 [33], to further demonstrate the effectiveness of our lightweight approach. Through the above analysis, the improved network not only guarantees lightweight properties but also achieves satisfactory accuracy with statistically validated improvements and strong real-time performance, making it highly suitable for mobile deployment in C. oleifera disease detection applications.

The proposed lightweight YOLO-Lite–based method for Camellia oleifera leaf disease detection achieves satisfactory accuracy while maintaining the advantages of low memory usage, fewer parameters, and smaller model size compared with classical object detection models. These characteristics highlight its potential for practical use in resource-constrained agricultural scenarios. At the same time, the model shows strong adaptability to different disease types, but its current evaluation is limited to a single dataset.

In future work, we will address these limitations by conducting cross-dataset validation to verify generalization, performing real-time deployment tests on mobile and edge devices, and introducing explainable AI techniques (e.g., Grad-CAM) to enhance the interpretability of the detection process. Furthermore, considering the variations in Camellia oleifera diseases across different growth stages, we will further summarize disease characteristics and continue to optimize the model through parameter reduction, aiming to improve both recognition accuracy and deployment feasibility in real-world applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Lin Luo and Qiang Bu for their valuable contributions to this study—specifically, their support in the planning of the research design, the conduct of experimental procedures, the editing of manuscript content, and the preparation of study reports. Special thanks are extended to all members of the public who volunteered to participate in this research and provided assistance throughout the process. Their dedication and collaboration were invaluable to the successful completion of this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jia-Yu Yang, Qiang Peng; data collection: Jia-Yu Yang; analysis and interpretation of results: Jia-Yu Yang, Xu-Yu Xiang; draft manuscript preparation: Xu-Yu Xiang, Qiang Peng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author Xu-Yu Xiang, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li G, Ma L, Yan Z, Zhu Q, Cai J, Wang S, et al. Extraction of oils and phytochemicals from Camellia oleifera seeds: trends, challenges, and innovations. Processes. 2022;10(8):1489. doi:10.3390/pr10081489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhu Y, Ni X, Wang H, Yao Y. Face recognition under low illumination based on convolutional neural network. Int J Auton Adapt Commun Syst. 2020;13(3):260–72. doi:10.1504/ijaacs.2020.110746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Long M, Long S, Peng F, Hu XH. Identifying natural images and computer-generated graphics based on convolutional neural network. Int J Auton Adapt Commun Syst. 2021;14(1–2):151–62. doi:10.1504/ijaacs.2021.114295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision; 2017 Oct 22–29; Venice, Italy. p. 2961–9. [Google Scholar]

5. Nyakuri JP, Nkundineza C, Gatera O, Nkurikiyeyezu K. State-of-the-art deep learning algorithms for internet of things-based detection of crop pests and diseases: a comprehensive review. IEEE Access. 2024;12(7553):169824–49. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3455244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Redmon J, Divvala S, Girshick R, Farhadi A. You only look once: unified, real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 779–88. [Google Scholar]

7. Liu W, Anguelov D, Erhan D, Szegedy C, Reed S, Fu CY, et al. SSD: single shot multibox detector. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision; 2016 Oct 11–14; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

8. Wang L, Bai J, Li W, Jiang J. Research progress of YOLO series target detection algorithms. J Comput Eng Appl. 2023;59(14):15–29. [Google Scholar]

9. Paymode AS, Magar SP, Malode VB. Tomato leaf disease detection and classification using convolution neural network. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI); 2021 Mar 5–7; Pune, India. p. 564–70. [Google Scholar]

10. Dwivedi R, Dey S, Chakraborty C, Tiwari S. Grape disease detection network based on multi-task learning and attention features. IEEE Sens J. 2021;21(16):17573–80. doi:10.1109/jsen.2021.3064060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhou C, Zhou S, Xing J, Song J. Tomato leaf disease identification by restructured deep residual dense network. IEEE Access. 2021;9:28822–31. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3058947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Akshai KP, Anitha J. Plant disease classification using deep learning. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication (ICPSC); 2021 May 13–14; Coimbatore, India. p. 407–11. [Google Scholar]

13. Qi J, Liu X, Liu K, Xu F, Guo H, Tian X, et al. An improved YOLOv5 model based on visual attention mechanism: application to recognition of tomato virus disease. Comput Electron Agric. 2022;194(1):106780. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2022.106780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chen Z, Wu R, Lin Y, Li C, Chen S, Yuan Z. Plant disease recognition model based on improved YOLOv5. Agronomy. 2022;12(2):365. doi:10.3390/agronomy12020365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Karegowda AG, Jain R, Devika G. State-of-art deep learning based tomato leaf disease detection. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Integrated Intelligent Computing Communication & Security (ICIIC 2021); 2021 Aug 6–7; Bangalore, India. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Atlantis Press; 2021. p. 303–11. [Google Scholar]

16. Tang Y, Zhou H, Wang H, Zhang Y. Fruit detection and positioning technology for a Camellia oleifera C. Abel orchard based on improved YOLOv4-tiny model and binocular stereo vision. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;211(3):118573. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang X, Zhou X, Lin M, Sun J. ShuffleNet: an extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 6848–56. [Google Scholar]

18. Wang H, Shang S, Wang D, He X, Feng K, Zhu H. Plant disease detection and classification method based on the optimized lightweight YOLOv5 model. Agriculture. 2022;12(7):931. doi:10.3390/agriculture12070931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ma N, Zhang X, Zheng HT, Sun J. Shufflenetv2: practical guidelines for efficient CNN architecture design. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. p. 116–31. [Google Scholar]

20. Zhang Y, Zhang H, Huang Q, Han Y, Zhao M. DsP-YOLO: an anchor-free network with DsPAN for small object detection of multiscale defects. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;241(13):122669. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.122669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang C, Kang F, Wang Y. An improved apple object detection method based on lightweight YOLOv4 in complex backgrounds. Remote Sens. 2022;14(17):4150. doi:10.3390/rs14174150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yu Y, Zhang K, Liu H, Yang L, Zhang D. Real-time visual localization of the picking points for a ridge-planting strawberry harvesting robot. IEEE Access. 2020;8:116556–68. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3003034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li Y, Huang H, Xie Q, Yao L, Chen Q. Research on a surface defect detection algorithm based on MobileNet-SSD. Appl Sci. 2018;8(9):1678. doi:10.3390/app8091678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. [Google Scholar]

25. Sheng W, Yu X, Lin J, Chen X. Faster RCNN target detection algorithm integrating CBAM and FPN. Appl Sci. 2023;13(12):6913. [Google Scholar]

26. Lin TY, Dollár P, Girshick R, He K, Hariharan B, Belongie S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2017 Jul 21–26; Honolulu, HI, USA. p. 2117–25. [Google Scholar]

27. Jiang D, Li G, Tan C, Huang L, Sun Y, Kong J. Semantic segmentation for multiscale target based on object recognition using the improved faster-RCNN model. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2021;123(1):94–104. doi:10.1016/j.future.2021.04.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang D, He D. Channel pruned YOLO V5s-based deep learning approach for rapid and accurate apple fruitlet detection before fruit thinning. Biosyst Eng. 2021;210(6):271–81. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2021.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Betti A, Tucci M. YOLO-S: a lightweight and accurate YOLO-like network for small target detection in aerial imagery. Sensors. 2023;23(4):1865. doi:10.3390/s23041865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Subramani SS, Shakeel MP, Bin Mohd Aboobaider B, Salahuddin LB. Classification learning assisted biosensor data analysis for preemptive plant disease detection. ACM Trans Sen Netw. 2022. In press. doi:10.1145/3572775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ge Z, Liu S, Wang F, Li Z, Sun J. Yolox: exceeding yolo series in 2021. arXiv:2107.08430. 2021. [Google Scholar]

32. Jocher G, Chaurasia A, Qiu J. YOLO by Ultralytics. [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

33. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J. Yolov10: real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. 2024;37:107984–8011. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools