Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Improved YOLO11 for Maglev Train Foreign Object Detection

1 School of Electrical Engineering and Automation, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, Ganzhou, 341000, China

2 Jiangxi Key Laboratory of Maglev Rail Transit Equipment, Ganzhou, 341000, China

* Corresponding Author: Lu Zeng. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 469-484. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.073016

Received 09 September 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 06 November 2025

Abstract

To address the issues of small target miss detection, false positives in complex scenarios, and insufficient real-time performance in maglev train foreign object intrusion detection, this paper proposes a multi-module fusion improvement algorithm, YOLO11-FADA (Fusion of Augmented Features and Dynamic Attention), based on YOLO11. The model achieves collaborative optimization through three key modules: The Local Feature Augmentation Module (LFAM) enhances small target features and mitigates feature loss during down-sampling through multi-scale feature parallel extraction and attention fusion. The Dynamically Tuned Self-Attention (DTSA) module introduces learnable parameters to adjust attention weights dynamically, and, in combination with convolution, expands the receptive field to suppress complex background interference. The Weighted Convolution 2D (wConv2D) module optimizes convolution kernel weights using symmetric density functions and sparsification, reducing the parameter count by 30% while retaining core feature extraction capabilities. YOLO11-FADA achieves a mAP@0.5 of 0.907 on a custom maglev train foreign object dataset, improving by 3.0% over the baseline YOLO11 model. The model’s computational complexity is 7.3 GFLOPs, with a detection speed of 118.6 FPS, striking a balance between detection accuracy and real-time performance, thereby offering an efficient solution for rail transit safety monitoring.Keywords

With the acceleration of urbanization and the continued growth of transportation demand, rail transit is becoming increasingly critical in modern urban transportation systems [1]. Among them, maglev trains, with their high speed, low noise, and low energy consumption, have emerged as a key direction for the future development of urban and intercity transportation. However, the safety of maglev train operations is highly dependent on the stability of the track environment. Any foreign object intrusion onto the track could pose a severe threat to train operations and potentially lead to safety accidents. Therefore, the development of efficient and precise foreign object intrusion detection technology for maglev trains is crucial in ensuring the safe operation of maglev transportation systems.

Early foreign object detection on railways mainly relied on manual inspections [2], a method that not only consumed substantial human labor and time but also lacked efficiency. Additionally, it was heavily influenced by human factors, making it difficult to ensure accuracy and timeliness. With advancements in technology, sensor-based detection methods have gradually been applied. Zhao et al. [3] proposed the FSDF (Fusion-based Self-supervised Detection Framework) framework, which integrates HSV (Hue, Saturation, and Value) color enhancement, YOLOv8 detection, and VQ-VAE (Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoder) unsupervised learning to improve the accuracy and robustness of fire detection, suitable for both forest and urban fire scenarios. Ma et al. [4] introduced MPCA-Net (Multi-Path Convolutional Attention Network), which enhances remote sensing image (PAN and MS) fusion classification performance through ADR-SS (Adaptive Dilation Rate Selection) adaptive dilation rate selection, CPM (Context Prior Module)-optimized sampling, and progressive collaborative fusion modules. Niu et al. [5] developed a FOD (Foreign Object Debris) detection model based on the Swin Transformer-enhanced YOLOv5, combining KNN (K-Nearest Neighbors) and FNN (Feedforward Neural Network) regression for geographical localization, improving detection accuracy and positioning for foreign objects on airport runways. Wang et al. [6] proposed EAL-YOLO (Efficient Attention Lightweight YOLO), using EfficientFormerV2 (Efficient Transformer version 2) as the backbone and integrating LSKA-SPPF (Large Separable Kernel Attention—Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast) and ASF2-Neck (Adaptive Spatial Feature Fusion Neck version 2) for lightweight detection of small equipment defects in substations, significantly reducing parameters and FLOPs. Zhu et al. [7] presented YOLOv8-C2FSf-Faster-EMA (Efficient Multi-scale Attention), optimizing the backbone and neck structures to improve the precision of underwater small trash detection (mAP increased by 5%), which can be transferred to remote sensing for localized monitoring. Khan and Niu [8] introduced CNN-DSCK (Convolutional Neural Network with Depthwise Separable Convolution and Kernel fusion), utilizing depth-separable convolutions and multi-kernel fusion to extract latent user-item features from text comments, enhancing recommendation system rating prediction accuracy. Jia et al. [9] proposed AdaptoMixNet (Adaptive Mixture Network), integrating AFM (Adaptive Feature Modulation), AEFPM (Adaptive Edge Feature Preservation Module), and CARAFE (CARAFE (Content-Aware ReAssembly of FEatures) filters to improve the accuracy and interference resistance of foreign object detection for power transmission lines under harsh weather conditions, RailVoxelDet (Railway Voxel-based Detection) introduces a lightweight voxel-based LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) pipeline optimized for long-range object detection with competitive inference speed and computational efficiency [10]. These methods from various fields have improved detection model performance to some extent and provide new ideas and approaches for this study.

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) series of algorithms, as representatives of single-stage object detection, are widely used in various fields due to their fast detection speed and strong real-time performance. Since the introduction of YOLOv1 in 2015, the YOLO series has undergone continuous evolution and optimization. YOLOv1 transformed the object detection task into a regression problem, simultaneously predicting both the class and location of objects within a single network, significantly improving detection speed. The subsequent YOLOv2 introduced techniques such as Batch Normalization and High-Resolution Classifier, further enhancing detection accuracy. YOLOv3 improved detection capabilities for objects of various sizes by designing more complex network structures, such as Darknet-53, and adopting a multi-scale prediction mechanism. In recent years, YOLO11 has raised the performance of this series to a new level. YOLO11 optimized the network architecture and introduced new modules, including C3K2, SPFF, and C2PSA, effectively reducing the parameter count and computational load while maintaining high detection accuracy and significantly increasing detection speed. However, despite these significant improvements in object detection performance, and camera-based solutions dominate current applications [11], YOLO11 still faces challenges in the specific application of maglev train foreign object detection. The maglev track environment is complex, with substantial background interference, and it contains a variety of foreign objects of differing sizes, making small object detection particularly challenging [12]. Additionally, the high speed of maglev trains places stringent demands on the real-time performance of detection algorithms. Therefore, improving and optimizing the YOLO11 algorithm for detecting foreign objects on maglev trains is of great practical significance.

This paper proposes a multi-module fusion improvement algorithm, YOLO11-FADA, based on YOLO11, which utilizes a three-tier module collaborative optimization approach. The weighted lightweight convolution (wConv2D) [13] module reduces the computational load while maintaining detection accuracy, thereby improving detection efficiency. The Local Feature Augmentation Module (LFAM) [14] enhances the feature representation of small targets, enabling the retention of more critical information during the complex feature extraction process for small objects. The Dynamically Tuned Self-Attention (DTSA) [15] module effectively suppresses background interference through dynamic attention adjustment, enabling the model to identify targets more accurately across various scenarios. The YOLO11-FADA algorithm proposed in this paper offers an effective solution for detecting foreign objects in maglev trains.

2.1 Current Status of Maglev Train Foreign Object Detection Technology

The safe operation of maglev trains is highly dependent on the absence of foreign objects in the track area. Currently, several technological approaches have been developed for foreign object detection on maglev trains [16]. Among traditional methods, sensor-based solutions are the most common. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) emits laser beams and measures the time delay of reflected light, enabling the acquisition of 3D point cloud data of the surrounding track environment. This data can be used to detect the presence and location of foreign objects. However, the detection accuracy of LiDAR is severely affected by adverse weather conditions (such as fog, rain, and snow), and its ability to detect small-sized objects is limited. Millimeter-wave radar utilizes electromagnetic waves in the millimeter-wave frequency band to detect target objects, offering some degree of penetration capability and performing well in identifying moving objects. However, it also suffers from low sensitivity to stationary small objects and is susceptible to interference in complex electromagnetic environments.

Vision detection technologies have emerged as prominent methods for detecting foreign objects in maglev trains in recent years. Systems based on monocular or binocular cameras can capture image information of the track area. By applying image processing and analysis algorithms [17], foreign objects in the images can be identified. Early visual detection methods were mainly based on traditional image processing techniques such as edge detection and threshold segmentation. While these methods could yield some results in simple backgrounds, their accuracy is difficult to maintain in the complex maglev track environment, where background interference and lighting variations are prevalent. With the development of deep learning technologies, convolutional neural network (CNN)-based object detection algorithms have been widely applied in visual detection, offering new solutions for detecting foreign objects on maglev trains.

2.2 Deep Learning-Based Object Detection Algorithms

Deep learning has made significant progress in the field of object detection [18,19], significantly advancing the development of this domain [20]. Currently, deep learning-based object detection algorithms are primarily categorized into two types: two-stage detection algorithms and single-stage detection algorithms.

The R-CNN series represents two-stage detection algorithms. R-CNN first generates a large number of candidate regions that may contain objects through selective search, then inputs these candidate regions into a CNN for feature extraction and classification, and finally refines the object locations using a bounding box regression algorithm. Fast R-CNN improves upon R-CNN by introducing a Region Proposal Network (RPN), which enables end-to-end training for both candidate region generation and object detection, thereby significantly enhancing detection speed. Faster R-CNN further optimizes the RPN, enabling it to generate high-quality candidate regions more efficiently. While two-stage detection algorithms typically offer higher detection accuracy, they are relatively slow due to the need to generate candidate regions and perform multiple processing steps, making them less suitable for real-time applications with high-speed requirements.

The YOLO series and SSD (Single Shot MultiBox Detector) [21] represent single-stage detection algorithms. SSD directly performs object detection on feature maps at different scales by setting prior boxes of various sizes and aspect ratios, and then predicts the object’s class and location. The YOLO series algorithms, on the other hand, transform the object detection task into a regression problem, predicting both the object’s class and location within a single network. YOLOv1 first introduced this single-stage detection approach by dividing the input image into multiple grids, with each grid responsible for predicting the objects that fall within it. Subsequent versions of YOLO have continuously optimized network structures and training methods [22]. For instance, YOLOv2 introduced batch normalization and high-resolution classifiers, enhancing detection accuracy. YOLOv3 [23] employs a multi-scale prediction mechanism, enhancing its ability to detect objects of varying sizes. YOLO11 further optimized the network architecture by introducing novel modules that reduce the number of parameters and computational load, while also increasing detection speed and accuracy. Single-stage detection algorithms are faster due to the absence of candidate region generation, making them suitable for real-time applications. However, they generally achieve slightly lower detection accuracy compared to two-stage detection algorithms.

In the context of maglev train foreign object detection, the high-speed operation of the train demands extremely high real-time performance from the detection algorithm, making single-stage detection algorithms particularly advantageous. As a leader among single-stage detection algorithms, the YOLO series demonstrates significant application potential in the field of maglev train foreign object detection. However, as previously mentioned, the original YOLO11 algorithm still faces performance limitations when confronted with the complex background of maglev tracks and small-sized foreign objects [24]. Therefore, further improvements and optimizations are required.

This paper utilizes YOLO11 as the baseline framework, which comprises three core components: the backbone network, the neck network, and the detection head. The backbone network is designed with alternating C3k2 modules and convolutional layers, performing five down-sampling operations to generate feature maps at three different scales (P3, P4, P5), corresponding to input image resolutions of 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32, respectively. This enables hierarchical extraction from low-level textures to high-level semantic features. The neck network utilizes a PAN-FPN (Path Aggregation Network—Feature Pyramid Network) [25] structure, which enhances cross-scale feature correlations through top-down up-sampling and bottom-up feature fusion. The P3 layer focuses on fine details of small targets, while the P5 layer emphasizes the semantic information of large targets. The detection head adopts an anchor-free design, directly predicting the object’s center coordinates (x, y), width and height (w, h), and class probabilities. The CIoU (Complete Intersection over Union) loss function is used to optimize localization accuracy [26], simplifying the traditional anchor-box matching process.

However, YOLO11 reveals several shortcomings when applied to the specific requirements of the maglev scenario. During the image down-sampling process, repeated convolution and pooling operations can lead to the gradual loss of feature information for small targets, making accurate detection difficult in subsequent layers. YOLO11’s receptive field is fixed by design, whereas the size of foreign objects in the maglev train operating environment varies widely, ranging from small birds to larger objects like fallen rocks. The fixed receptive field is unable to adapt to this multi-scale variation, thereby impacting detection performance. Additionally, convolution operations involve some redundant computations, such as repeated calculations in background areas, which not only increase computational load but also affect the model’s real-time performance, making it inadequate for the fast response requirements of foreign object detection in maglev trains.

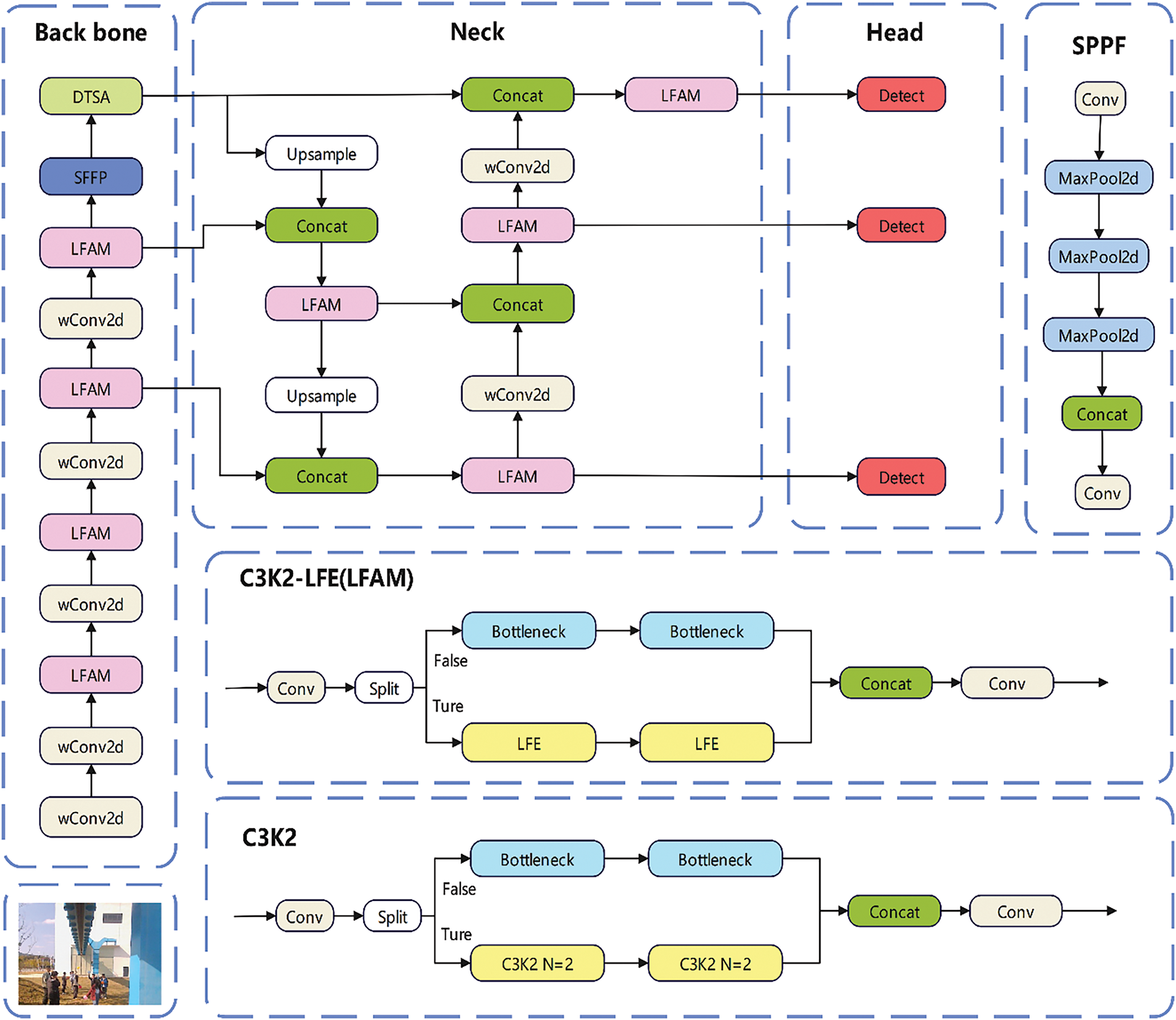

To address the challenges of multi-scene interference, sparse small target features, and the need for lightweight design in maglev train track foreign object detection, this paper proposes a fusion model architecture incorporating the Local Feature Augmentation Module (LFAM), Dynamically Tuned Self-Attention (DTSA) module, and Weighted 2D Convolution (wConv2D), as shown in Fig. 1. First, the LFAM module is integrated into the Backbone network to enhance the feature representation of small targets and reduce feature loss. At the same time, all 3 × 3 convolution layers are replaced by weighted lightweight convolutions (WConv2D). LFAM mitigates slight target information loss through multi-scale parallel feature extraction, and WConv2D reduces computational redundancy through sparsification, together achieving the dual objectives of “feature enhancement” and “lightweight design”. Second, the DTSA dynamic attention module is embedded in the Neck network to dynamically allocate weights to the feature maps, suppressing complex background interference and enhancing the discriminability between target and background features. The detection head (Head) retains the anchor-free design. To address the scale differences of foreign objects in the maglev environment, the bounding box regression formula is optimized by introducing a scale-adaptive weight factor:

Figure 1: YOLO-FADA model structure

In this,

The calculation of the scale-adaptive weight factor

where

Ultimately, through the collaborative optimization of the aforementioned modules, the detection head can more accurately predict the location and class of foreign objects of varying sizes, thereby enhancing the overall detection performance of the model in complex maglev train environments. Experimental results demonstrate that the YOLO11-FADA algorithm effectively enhances detection accuracy while maintaining real-time performance in maglev train foreign object detection.

3.3.1 WConv2D Lightweight Convolution Layer

Based on the theory of weighted convolution, this paper proposes a sparsified convolution layer, referred to as the WConv2D layer. The core of this design achieves lightweight performance through a three-tier strategy involving weight optimization, sparsification processing, and channel pruning.

(1) Symmetric Weight Optimization

To address the issue of small target features being overwhelmed due to the uniform weight distribution of traditional 3 × 3 convolution kernels, a symmetric weight design with a central focus is adopted. This design is based on the observation that target features are more densely distributed in the central region, a characteristic that has been validated in numerous deep learning studies. For instance, Simonyan and Zisserman’s VGGNet research [27] demonstrated that, within convolutional neural networks, the central pixels of a convolution kernel—due to their receptive fields covering a greater number of neighboring pixels—are able to aggregate richer local information. Compared with edge pixels, central pixel positions provide more concentrated feature representations with stronger discriminative power. In the field of object detection, the CenterPoint algorithm proposed by Yin et al. [28] also leverages central features of objects for detection, further underscoring the importance of central region features.

On this basis, the symmetric density pattern is employed to reinforce the weights of core pixels The weight coefficient at the center of the convolution kernel is set to 1. In contrast, the four neighboring coefficients (up, down, left, and right) are set to 0.42, and the four corner regions maintain symmetry with the same coefficient of 0.42. This distribution assigns a central weight 2.38 times that of the edge, focusing on key areas such as the body of a bird or the main body of a plastic bag, while reducing interference from background noise, including track metal reflections and tunnel shadows. Experimental results demonstrate that this design enhances feature response strength by 29% in small object detection for maglev tracks, effectively distinguishing foreign objects as small as 10 × 10 pixels from background textures.

(2) Sparse Processing

To reduce redundant parameters, dynamic threshold sparsification is applied to the weighted convolution kernel. The threshold is defined as:

here,

here,

Compared to a fixed threshold (e.g., 0.05), the dynamic threshold can adapt to different scenarios (e.g., bright/low light). In tunnel environments, it retains 92% of the core weights while sparsifying redundant edge weights (accounting for 78%), resulting in an overall sparsity rate of 90%, thereby preventing the inadvertent removal of key features.

(3) Channel Pruning

Pruning is implemented based on the contribution of channels to foreign object features, with channel importance scores calculated using L1 regularization:

where

The top 70% of channels based on the scores are retained, and the pruning threshold γ is determined through accuracy constraints on the validation set:

here,

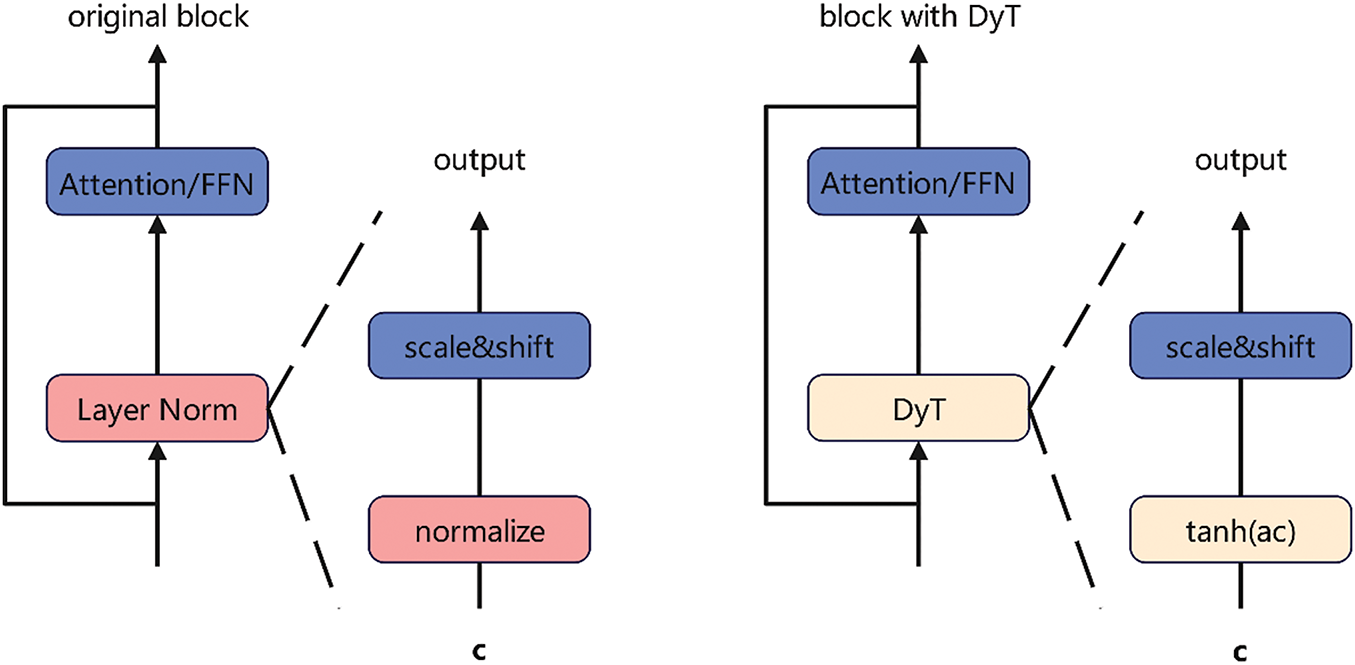

To enhance the model’s ability to differentiate targets in complex backgrounds, this paper proposes an improved C2PSA module, as shown in Fig. 2. The improved C2PSA module is referred to as the DTSA module. The name ‘DTSA’ is derived from its core characteristics: ‘Dynamic’—dynamic weight adjustment achieved through a learnable parameter α combined with the Sigmoid function for adaptive channel attention; ‘Tuned receptive field’—a larger receptive field enabled by the 7 × 7 convolution, providing enhanced spatial perception to better adapt to complex backgrounds; and ‘Self-Attention’—a self-attention mechanism that strengthens the discrimination between targets and background. Hereafter, this module is referred to as the DTSA module. The core improvement lies in the introduction of a dynamic weight adjustment mechanism. By incorporating a learnable parameter αand using a Sigmoid function, dynamic adjustment of channel attention weights is achieved. As training progresses, the model continually adjusts the value of α based on different scenarios and target features, dynamically allocating attention weights to focus more on the target areas while suppressing background interference. In terms of spatial attention optimization, a 7 × 7 convolution is used to replace the original 3 × 3 convolution, thereby expanding the receptive field of the convolution kernel. This enables the model to perceive a broader range of spatial information, thereby better adapting to the relationships between targets and their surrounding environments in complex backgrounds. For normalization, the Dynamic Tanh operation is used to replace the traditional layer normalization. As shown in the ‘block with DyT’ on the right side of Fig. 2, This replacement reduces computational overhead while maintaining model performance stability.

Figure 2: Left: original transformer module; right: module for dynamic tanh (DyT) layer

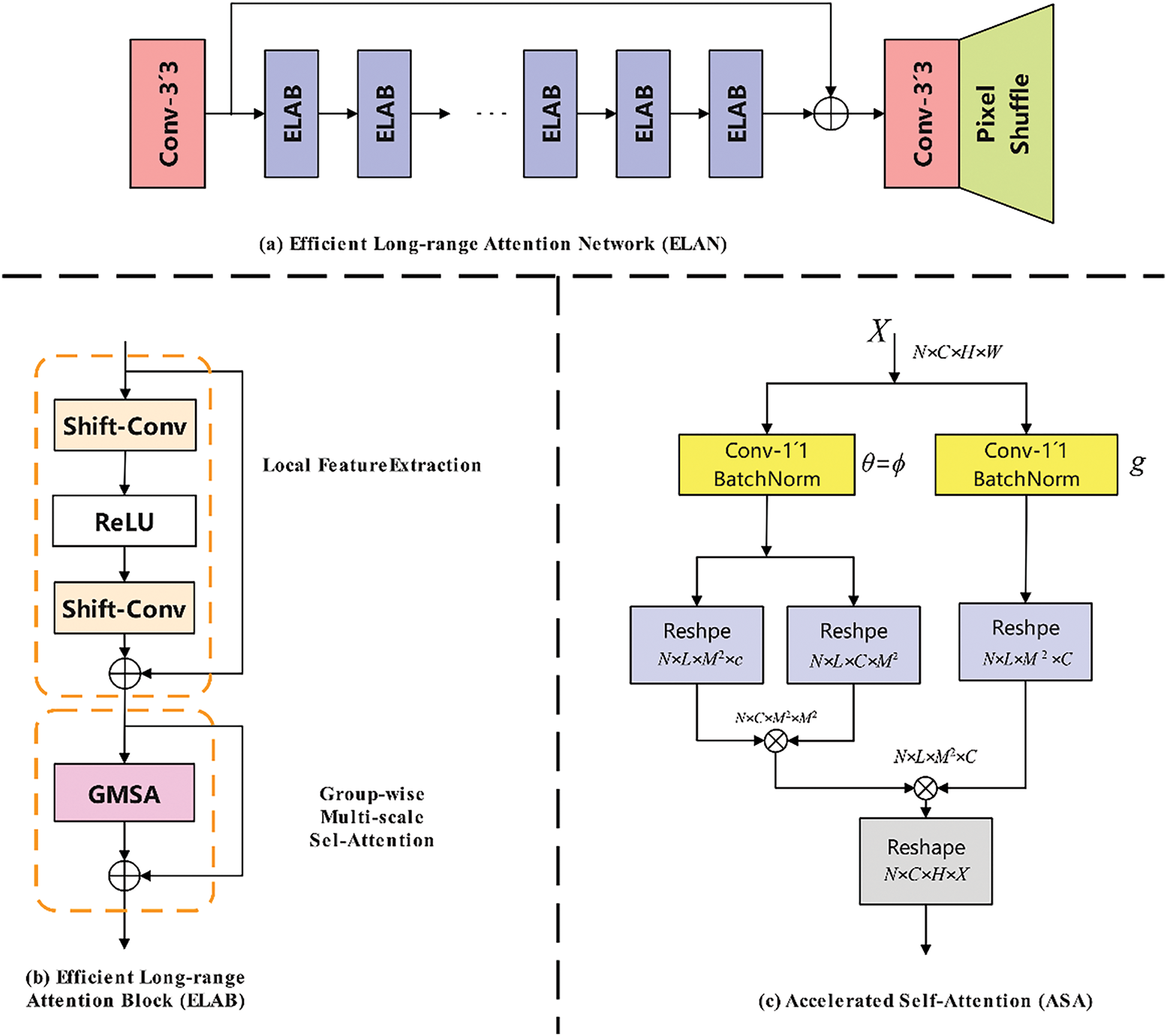

To address the issue of small object features being easily lost during extraction, a Local Feature Augmentation Module (LFAM) was designed within the C3k2 module, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The LFAM module enhances small object features through the following process: LFE multi-scale feature extraction → SE channel attention weighting → residual fusion.

Figure 3: Schematic of the local feature augmentation module (LFAM). (a) Overall workflow of LFAM, including multi-scale parallel feature extraction (corresponding to the core logic of the LFE module) and channel attention weighting (corresponding to the core logic of the SE module); (b) Structure of the feature processing block within LFAM, illustrating the residual fusion mechanism; (c) Computation process of channel attention weighting, corresponding to the internal operations of the SE module

LFE Module: This module employs parallel 1 × 1 and 3 × 3 convolutional branches. The 1 × 1 convolution captures fine details of small objects (e.g., birds, balloons), while the 3 × 3 convolution focuses on extracting the contours of the targets. By operating in parallel, multi-scale features of small objects are comprehensively extracted, providing a rich feature foundation for subsequent processing. This corresponds to the multiple Efficient Long-range Attention Blocks (ELAB) in Fig. 3a, which extract multi-branch features in parallel.

SE Module: After multi-scale features are extracted by the LFE module, the SE module applies channel-wise weighting. It first performs global average pooling to obtain global statistics for each channel, and then learns channel weights through fully connected layers and other operations. The weights are assigned according to feature importance, thereby enhancing the response of small objects in the feature map. This process aligns with the dimension transformation and weight learning steps illustrated in Fig. 3c, Accelerated Self-Attention (ASA) computation diagram.

Residual Fusion: The LFAM module introduces a residual connection that adds the features enhanced by the LFE and SE modules to the original features. This not only preserves the enhanced feature information but also retains important information from the original features, preventing potential information loss during feature enhancement. The residual connection

4 Experiments and Result Analysis

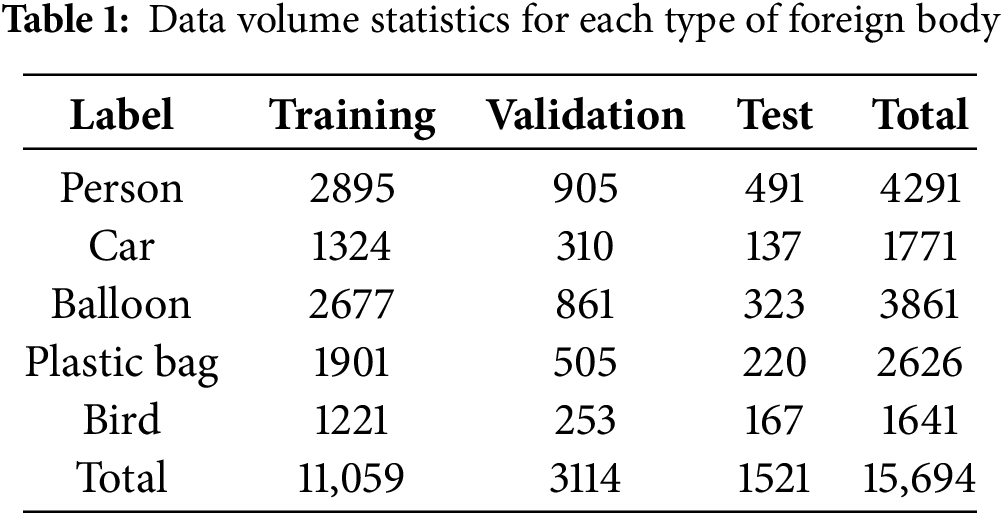

To accurately evaluate the performance of the proposed improved algorithm in foreign object detection for maglev trains, a dataset was constructed using real-world data collected from the “Red Rail” maglev line in Ganzhou City. The dataset contains 3900 images, with foreign objects carefully annotated and categorized into five classes. These include large-scale targets such as a person, a car, as well as small-scale targets such as a balloon, a plastic bag, and a bird.

For dataset partitioning, the images were divided into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio. The training set comprises 2730 images and is used to train the model to recognize the features and patterns of various foreign objects. The validation set, comprising 780 images, is used during training to tune hyperparameters and prevent overfitting. The test set consists of 390 images and is used for the final evaluation of model performance. To further enhance the model’s generalization capability, multiple data augmentation techniques were applied, including random flipping to enable the model to learn object features from different perspectives, brightness adjustment to simulate varying illumination conditions, and Gaussian blurring to introduce noise and help the model adapt to more realistic and complex environments.

The distribution of different foreign objects in the dataset is shown in Table 1. As shown in the table, there are significant differences in both the quantity and size of foreign objects across categories. Large-scale targets, such as persons, cars, have a relatively larger number of samples and greater average size, while small-scale targets, such as balloons, plastic bags, and birds, have fewer samples and smaller average size.

The operating system used in the experiments was Windows 11, with hardware specifications including a 13th Gen Intel (R) Core (TM) i7-13620H CPU at 2.4 GHz and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4060 GPU. The experimental environment was set up in PyCharm, using Python version 3.9.19, and built upon PyTorch 2.3.0 and CUDA 12.1. The input image size for the experiments was 640 × 640. Based on preliminary experiments, the number of training epochs was set to 150, the batch size to 16, the learning rate to 0.01, the momentum for stochastic gradient descent to 0.937, and the weight decay coefficient to 0.0005. All experiments in this study were conducted using this configuration for training, validation, and testing.

The evaluation metrics used to assess the model include Precision (P), Recall (R), Mean Average Precision (mAP), the number of parameters (Params), computational complexity (FLOPs), and Frames Per Second (FPS). mAP50 refers to the mean average precision at an intersection-over-union (IoU) threshold of 0.5.

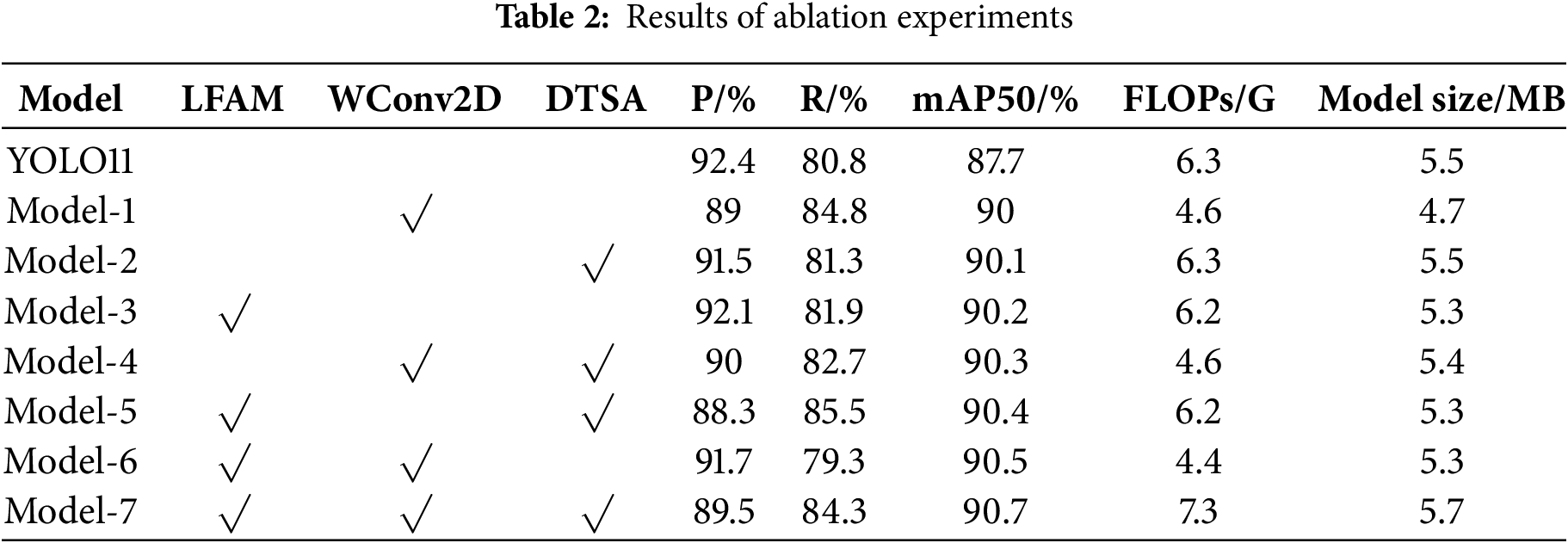

4.3 Effects of Single Module Improvements

To validate the effect of each improvement module, YOLO11 was used as the base model. Ablation experiments were conducted by progressively introducing and combining different modules under the same configuration. A “√” indicates the inclusion of a module in the YOLO11 model. The specific experimental results are shown in Table 2.

In the data for Model 1 in Table 2, after introducing the WConv2D module into the YOLO11 model, FLOPs decreased from 6.3 to 4.6 G, Recall (R) improved to 84.8%, and mAP50 increased to 90%. This demonstrates that the module, through its lightweight design, effectively reduces computational complexity while enhancing feature extraction efficiency and improving the recall of small target detection. For Model 2, after adding the DTSA module, R increased to 81.3% and mAP50 reached 90.1%, validating its effectiveness in suppressing complex background interference and focusing on the target region via the dynamic attention mechanism, thus enhancing the model’s robustness in maglev scenarios. Model 3, with the addition of the LFAM module, saw a 2.5% increase in mAP50, a reduction in FLOPs to 6.2 G, and a decrease in model size to 5.3 MB, demonstrating that this module strengthens small target feature representation through multi-scale feature fusion while optimizing model efficiency. Model-4 (WConv2D+DTSA) achieved a mAP50 of 90.3% and a 1.9% improvement in R, reflecting the synergistic effect of lightweight design and interference suppression mechanisms. Model-5 (LFAM + DTSA) achieved a 4.7% + a mAP50 increase to 90.4%, demonstrating that the combination of feature enhancement and attention modulation further enhances the model’s ability to capture targets. Finally, Model-6 (LFAM+WConv2D) achieved a mAP50 of 90.5%, with FLOPs reduced to 4.4 G, demonstrating the complementary relationship between feature reinforcement and lightweight design in achieving a balance between accuracy and efficiency.

Finally, Model-7, which integrates all three modules, achieved a mAP50 of 90.7% and a Recall (R) of 84.3%, demonstrating a multi-dimensional synergistic optimization of feature enhancement, lightweight design, and interference suppression. This significantly improved the performance of foreign object detection in maglev trains.

4.4 Visualization Analysis of Model Performance

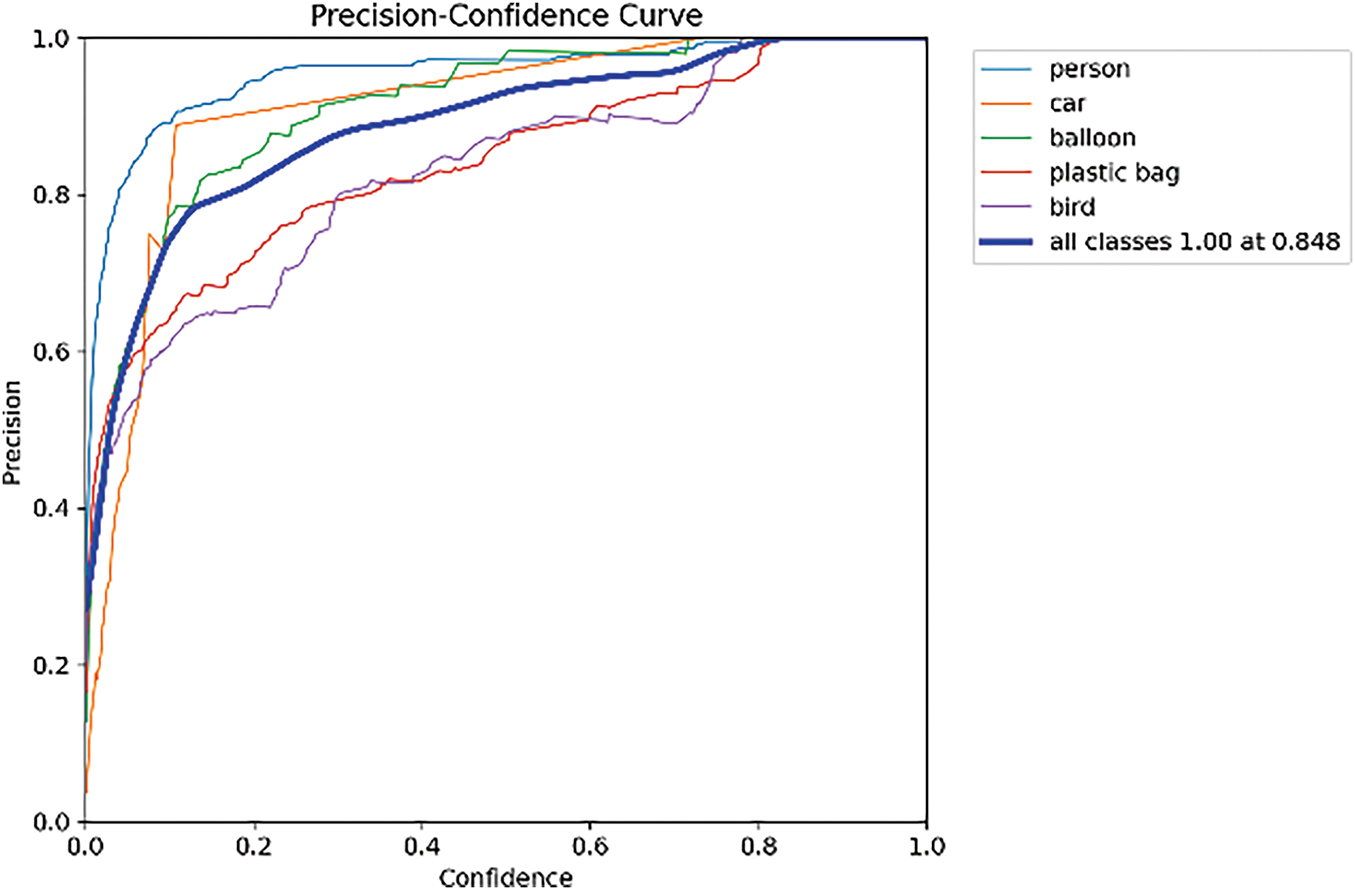

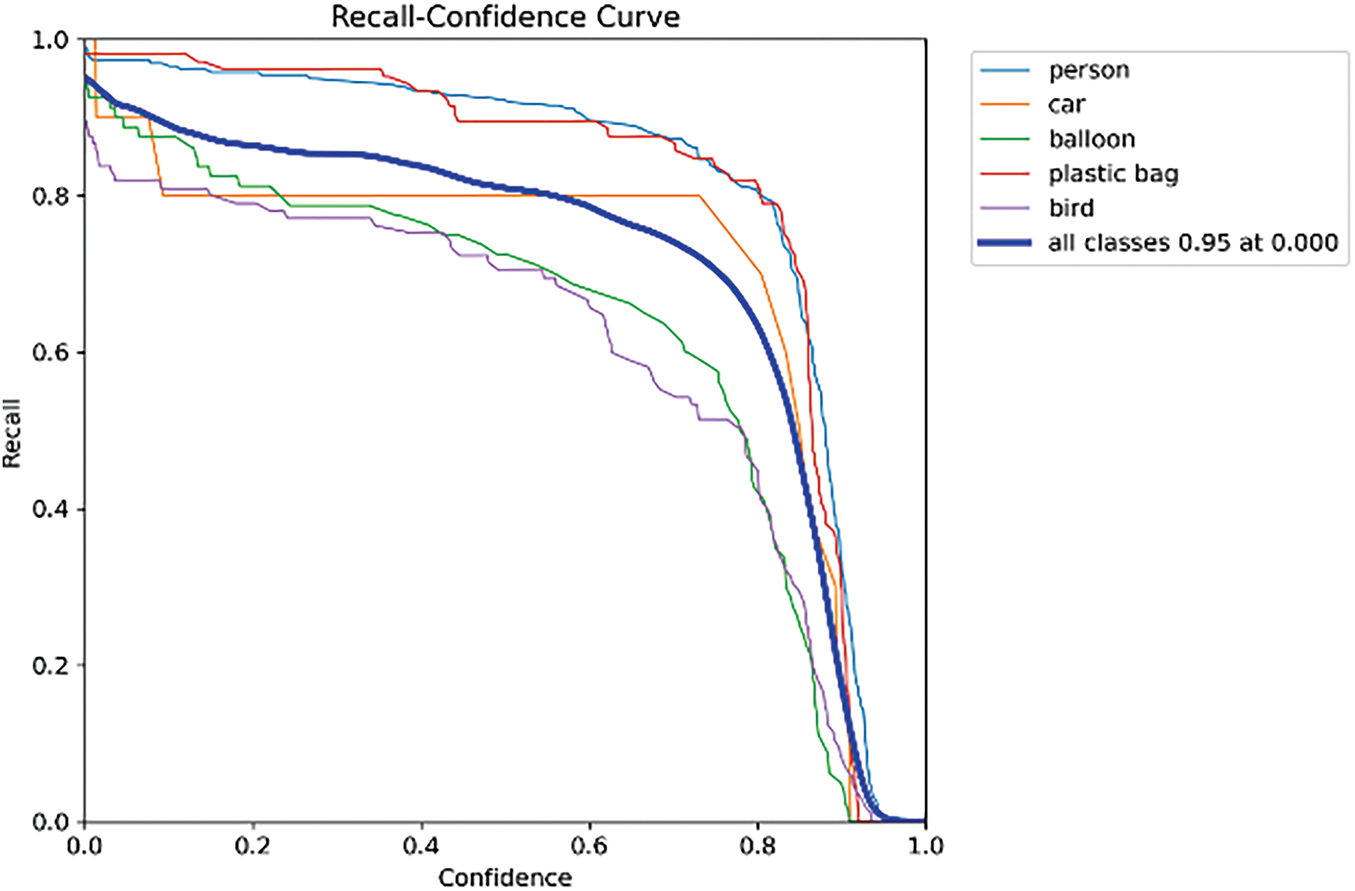

To visually assess the performance of the multi-module fusion algorithm in maglev train foreign object detection, two core curves were plotted: the precision–confidence curve and the recall–confidence curve. These curves cover representative foreign object categories, including person, car, balloon, plastic bag, and bird.

As shown in Fig. 4, a notable variation in precision is observed across different target categories as confidence scores increase. For the person category, when confidence exceeds 0.2, precision consistently holds above 0.95, demonstrating robust performance in pedestrian detection. The car category achieves a precision of 0.92 in the 0.3–0.8 confidence range, effectively detecting track-intruding vehicles. Although small target categories, such as balloons and plastic bags, exhibit steeper curve slopes, they converge to precision levels above 0.85, indicating the LFAM module’s exceptional enhancement of features for low-resolution foreign objects. When the confidence stands at 0.5, the average precision across all categories reaches 0.948, reflecting the global detection capability fostered by the multi-module collaboration.

Figure 4: Precision-confidence curve

Fig. 5 presents the recall–confidence curve, focusing on the negative correlation between confidence and recall rate. For the person category, when the confidence is below 0.3, recall approaches 1.0, indicating a very low miss rate for high-confidence pedestrian detections. For the car and plastic bag categories, recall remains above 0.85 within the confidence range of 0.2–0.6, meeting the requirements for rapid detection in maglev track scenarios. For more vulnerable categories, such as balloon and bird, the slope of the curve is relatively gentle, with recall remaining above 0.7 at a confidence level of 0.5. This demonstrates the feature retention capability of LFAM+DTSA for small and interference-prone targets. At a confidence of 0.1, the recall rate across all categories reaches 0.95, fulfilling the core requirement of “early detection, minimal missed detections.”

Figure 5: Recall-confidence curve

In summary, the two curves cross-validate the advantages of the multi-module fusion algorithm: it demonstrates strong robustness in small target detection, exhibits excellent adaptability to complex scenarios, and achieves a good balance between recall and precision when the confidence threshold is set to 0.5. This provides low-latency, high-reliability detection capabilities suitable for deployment on edge devices.

4.5 Comparison of YOLO Series Algorithms

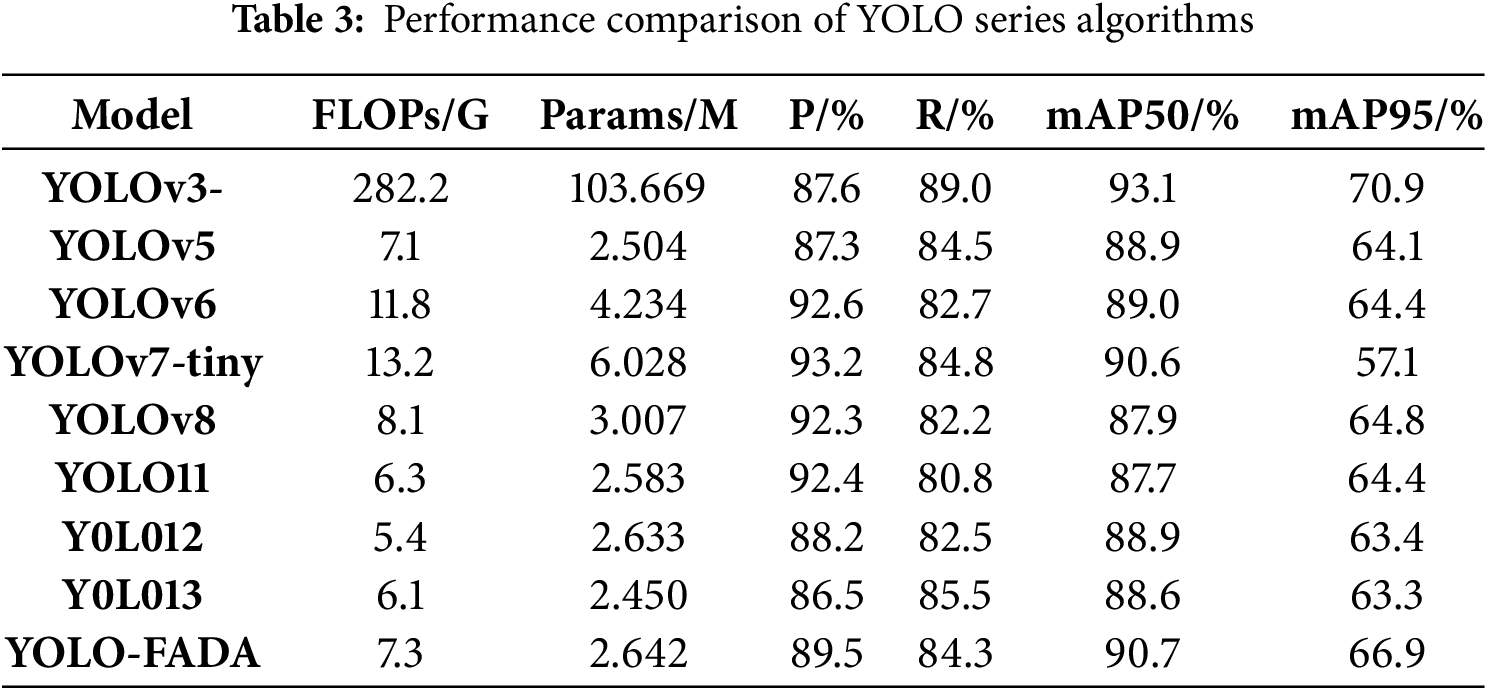

To objectively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed YOLO11-FADA algorithm, comparative experiments were conducted against other YOLO series models. The results are presented in Table 3.

Specifically, comparisons were made with YOLOv3, YOLOv5, YOLOv6, YOLOv7-tiny, YOLOv8, YOLO11, YOLO12, and YOLO13. As shown in the table, the proposed algorithm achieves superior performance on detection accuracy metrics compared with other YOLO variants. In particular, relative to YOLO11, YOLO11-FADA improves the recall (R) by 3.5%, mAP50 by 3.0%, and mAP95 by 2.5%. Compared with YOLOv8, it improves mAP50 by 2.8% and mAP95 by 2.1%. Meanwhile, the proposed model maintains a parameter count of only 2.642 M and a computational complexity of 7.3 GFLOPs, achieving a favorable trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. This lightweight design makes it more suitable for deployment in real-world scenarios such as foreign object detection in maglev trains.

In summary, YOLO11-FADA demonstrates higher detection accuracy than other YOLO series algorithms while requiring relatively low computational resources. The combination of accuracy and lightweight design highlights its significant practical value in maglev train foreign object detection applications.

To address core challenges in maglev train foreign object intrusion detection, such as small target miss detection, false positives in complex scenarios, and inadequate real-time performance, this paper proposes a multi-module fusion improvement algorithm, YOLO11-FADA, based on YOLO11. In the backbone network, the LFAM (Local Feature Attention Module) is introduced to enhance the feature representation of small targets, reducing feature loss during down-sampling through multi-scale parallel convolutions and attention fusion. The traditional convolution layer is replaced with the lightweight WConv2D convolution layer, which reduces the parameter count by 30% through symmetric weight optimization and sparsification, while preserving core feature extraction capabilities and improving computational efficiency. The DTSA (Dynamically Tuned Self-Attention) module is embedded in the neck network, dynamically adjusting attention weights via learnable parameters to expand the receptive field, suppress complex background interference, and improve the distinction between the target and background. Experimental results demonstrate that, compared to the baseline YOLO11 model, the improved algorithm achieves a 3.0% increase in mAP@0.5, with a reduced computational complexity of 7.3 GFLOPs and a detection speed of 118.6 FPS, thereby balancing accuracy and efficiency in maglev train foreign object detection tasks.

In future work, we plan to conduct in-depth research along the following directions. First, we intend to employ knowledge distillation, using the improved YOLO11 model proposed in this study as the teacher model to distill a more lightweight student model. This approach aims to further reduce computational complexity and deployment difficulty while maintaining detection performance, thereby better accommodating the hardware resource constraints of maglev train onboard devices. Second, we will explore hardware–software co-design strategies. Specifically, for computationally intensive operations in the inference process (e.g., convolution operations), we will leverage the characteristics of dedicated hardware such as FPGA (Field-Programmable Gate Array) and ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuit) to perform algorithm–hardware co-optimization, thereby enhancing inference speed in real-world scenarios. Finally, we plan to expand the dataset scale. On the one hand, we will collect more real-world foreign object samples from maglev train operation scenarios; on the other hand, we will incorporate public datasets (e.g., small-object samples from COCO) for cross-domain data fusion. This will enrich dataset diversity and further validate and improve the generalization capability of the proposed model.

Acknowledgement: We extend our sincere gratitude to everyone who supported this work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Research work was conducted by Qinzhen Fang, reviewed, supervised and validated by Dongliang Peng, Lu Zeng and Zixuan Jiang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset used in this study was collected from a proprietary maglev train monitoring system and contains sensitive operational data. Due to confidentiality agreements and institutional policies, the raw data cannot be made publicly available. However, the experimental setup, data acquisition methodology, and model training details are fully described in this manuscript to ensure reproducibility. Upon reasonable request, the corresponding author may provide anonymized data subsets or simulation data for academic research purposes, subject to approval by the relevant authorities.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mirzaei SM, Radmehr A, Holton C, Ahmadian M. In-motion, non-contact detection of ties and ballasts on railroad tracks. Appl Sci. 2024;14(19):8804. doi:10.3390/app14198804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Li M, Lu C, Yan X, He R, Zhao X. Enhanced detection of foreign objects on molybdenum conveyor belt based on anchor-free image recognition. Appl Sci. 2024;14(16):7061. doi:10.3390/app14167061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhao H, Jin J, Liu Y, Guo Y, Shen Y. FSDF: a high-performance fire detection framework. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;238(41):121665. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ma W, Li Y, Zhu H, Ma H, Jiao L, Shen J, et al. A multi-scale progressive collaborative attention network for remote sensing fusion classification. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2021;34(8):3897–3911. doi:10.1109/tnnls.2021.3121490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Niu Z, Zhang J, Li Z, Zhao X, Yu X, Wang Y. Automatic detection and predictive geolocation of foreign object debris on airport runway. IEEE Access. 2024;12:133748–63. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3460788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wang J, Sun Y, Lin Y, Zhang K. Lightweight substation equipment defect detection algorithm for small targets. Sensors. 2024;24(18):5914. doi:10.3390/s24185914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhu J, Hu T, Zheng L, Zhou N, Ge H, Hong Z. YOLOv8-C2f-Faster-EMA: an improved underwater trash detection model based on YOLOv8. Sensors. 2024;24(8):2483. doi:10.3390/s24082483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Khan ZY, Niu Z. CNN with depthwise separable convolutions and combined kernels for rating prediction. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;170(5):114528. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jia X, Ji C, Zhang F, Liu J, Gao M, Huang X. AdaptoMixNet: detection of foreign objects on power transmission lines under severe weather conditions. J Real-Time Image Process. 2024;21(5):172. doi:10.1007/s11554-024-01546-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Chen Z, Yang J, Chen L, Li F, Feng Z, Jia L, et al. RailVoxelDet: an lightweight 3D object detection method for railway transportation driven by on-board LIDAR data. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(18):37175–89. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3582636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen Z, Yang J, Li F, Feng Z, Chen L, Jia L, et al. Foreign object detection method for railway catenary based on a scarce image generation model and lightweight perception architecture. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technol. 2025:3567319. doi:10.1109/TCSVT.2025.3567319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu J, Jing D, Zhang H, Dong C. Srfad-net: scale-robust feature aggregation and diffusion network for object detection in remote sensing images. Electronics. 2024;13(12):2358. doi:10.3390/electronics13122358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. He LH, Zhou YZ, Liu L, Zhang YQ, Ma JH. Research on the directional bounding box algorithm of YOLO11 in tailings pond identification. Measurement. 2025;253(8):117674. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2025.117674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang X, Zeng H, Guo S, Zhang L. Efficient long-range attention network for image super-resolution. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2022. p. 649–67. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhu J, Chen X, He K, LeCun Y, Liu Z. Transformers without normalization. In: Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognitio; 2025 Jun 10–17; Nashville, TN, USA: IEEE; 2025. [Google Scholar]

16. Chen L, Gu L, Zheng D, Fu Y. Frequency-adaptive dilated convolution for semantic segmentation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2024 Jun 16–22; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 3414–25. [Google Scholar]

17. Redmon J, Farhadi A. Yolov3: an incremental improvement. arXiv:1804.02767. 2018. [Google Scholar]

18. Wang Z, Li C, Xu H, Zhu X. Mamba YOLO: SSMs-based YOLO for object detection. arXiv:2406.05835. 2024. [Google Scholar]

19. Li B, Peng F, Hui T, Wei X, Wei X, Zhang L, et al. RGB-T tracking with template-bridged search interaction and target-preserved template updating. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2024;47(1):634–49. doi:10.1109/tpami.2024.3475472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2016;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/tpami.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li Y, Dong H, Li H, Xiao Z. Multi-block SSD based on small object detection for UAV railway scene surveillance. Chin J Aeronaut. 2020;33(6):1747–55. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2020.02.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen LC, Papandreou G, Kokkinos I, Murphy K, Yuille AL. Deeplab: semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2017;40(4):834–48. doi:10.1109/tpami.2017.2699184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sun Y, Xie Z, Qin Y, Chuan L, Wu Z. Image detection of foreign body intrusion in railway perimeter based on dual recognition method. In: European Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2020. p. 645–54. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-64908-1_60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yu Z, Wan J, Qin Y, Li X, Li SZ, Zhao G. NAS-FAS: static-dynamic central difference network search for face anti-spoofing. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2020;43(9):3005–23. doi:10.1109/tpami.2020.3036338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sharma N, Gupta S, Reshan MSA, Sulaiman A, Alshahrani H, Shaikh A. EfficientNetB0 cum FPN based semantic segmentation of gastrointestinal tract organs in MRI scans. Diagnostics. 2023;13(14):2399. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13142399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wu G, Wu Q. Enhancing steel surface defect detection: a Hyper-YOLO approach with ghost modules and Hyper FPN. IAENG Int J Comput Sci. 2024;51(9):1321. [Google Scholar]

27. Simonyan K, Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv:1409.1556. 2014. [Google Scholar]

28. Yin T, Zhou X, Krahenbuhl P. Center-based 3d object detection and tracking. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 11784–93. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools