Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Using Hate Speech Detection Techniques to Prevent Violence and Foster Community Safety

1 Department of Information Technology, Lahore Leads University, Lahore, 42000, Pakistan

2 School of Electronics and Information Engineering, Taiyuan University of Science and Technology, Taiyuan, 030000, China

* Corresponding Author: Muhammad Hasnain. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 485-498. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.071933

Received 15 August 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

Violent hate speech and scapegoating people against one another have emerged as a rising worldwide issue. But identifying and combating such content is crucial to create safer and more inclusive societies. The current study conducted research using Machine Learning models to classify hate speech and overcome the limitations posed in the existing detection techniques. Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN) and Decision Tree were used on top of a publicly available hate speech dataset. The data was preprocessed by cleaning the text and tokenization and using normalization techniques to efficiently train the model. The experimental results indicate that LR and RF achieved good performance compared to other models, with LR achieving the highest testing accuracy of 93.66 and RF providing good general performance. These results demonstrate that the state-of-the-art applications of deep learning models are surpassed by optimized, and traditional machine learning models for hate speech detection. The research also highlights the need for constant re-adaptation to a linguistic shift and new forms of intolerance, emphasizing the interest of machine learning to support the actions against prejudice and social injustice in digital environments. This study benchmarks optimized machine learning algorithms for hate speech detection, demonstrating that traditional models can rival deep learning performance.Keywords

The world is witnessing a dramatic increase in hate speech, which is a significant danger to the peace and security of society [1,2]. The hate speech term is focused on the offensive language that aims at targeting individuals or specific groups.

Individual characteristics or combined features include gender, age, religion, race and ethnicity, and sexual orientation, which are primarily the targets of hate speeches [3,4]. Hate speech detection is a problem to be solved, given how big the problem has become and given the growing volume of data that is available online. Hate speech detection aims to fight hate speech, especially voice-breeding violence by means of machine learning. Therefore, the effective machine learning-based detection of hate speech is more vital to maintaining a stable social order, aiming at social cohesion.

The ability to detect hate speech is invaluable when it comes to abating the rate of physical violence in cases like hate crimes, mass shootings and genocides. Identifying hateful content early to allow authorities to take action in preventing the escalation of violence and promoting an atmosphere of acceptance and inclusivity [5]. By infighting and fixing hate speech, it may assist in remedying core societal problems, such as discrimination and prejudice and make way for a more united and peaceful civilization. But it is a daunting task, trapped with challenges such as regional differences in culture, data overload and detection of subtle levels of hate speech.

Hate speech detection becomes extremely hard because of how we define hate speech in a world of different societies and cultures. This adds a layer of further complexity, as each culture has very subtly different terms and expressions, and might be horrifying to other people. It is another completely different set of terms, making a nearly impossible detection system. In addition, with the expansion of existence online activities, they require scalable, and mainstream, machine learning-type (ML-type) models to operate on enormous data sizes. Detection systems have problems with both false positives (mistaking something does not hate speech as being hate speech) and false negatives (not detecting hate speech), which are resilient methods to reduce the problem.

Recent advancements in ML and Natural Language Processing (NLP) have brought some interesting approaches to identifying hate speeches [6]. Viewer model approaches can be broadly categorized into, three distinct sub-types, namely, rule-based systems for blatant hate speech, ML models for subtle or ambiguous kinds of hate speech and hybrid systems that combine multiple approaches to mitigate the limitations of these various individual approaches and undertake a more thorough analysis of the text in question [7,8]. Despite being efficient, deep learning models are costly in term of computational resources and biased due to the training data set. Recent advances (e.g., using transformer-based architectures) such as Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) open the possibility of addressing these challenges by enabling the capture of complex relationships and contextual details in text inputs. Hate speech detection even shares some similarities with cyberbullying detection, where contextual cues and culture are important factors. The potential of prompt-based large language models in detecting cyberbullying and learning show that how robust the frameworks should be in place to detect harmful online content. This study aims to devise and benchmark the optimized ML-based techniques for accurate hate speech detection. This research establishes the optimized ML-based techniques to be able to classify hate accurately.

Unlike most previous studies that relied heavily on deep learning architectures (e.g., CNN, LSTM, or BERT) and language-specific datasets, this research focuses on benchmarking optimized traditional machine learning algorithms using a balanced English-language dataset. The study uniquely demonstrates that with proper preprocessing, feature engineering, and hyperparameter optimization, classical models such as Logistic Regression and Random Forest can outperform or match the accuracy of more complex deep learning models while remaining models are computationally efficient. This practical contribution bridges the gap between resource-heavy AI methods, accessible and deployable solutions for real-world moderation systems.

This study contributes to the literature as follows:

1. Proposing the application of machine learning models to efficiently classify hate speeches and using innovative feature selection and ensemble techniques.

2. Providing insights into the performance of different machine learning algorithms under varied conditions, with a focus on practical deployment challenges.

3. Highlighting societal implications, including ethical considerations and strategies to promote tolerance and inclusiveness.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of the related studies on hate speech. Section 3 gives us details on the methods used in this study, and Section 4 provides experimental results and their discussion. Section 5 concludes the main points of the research study.

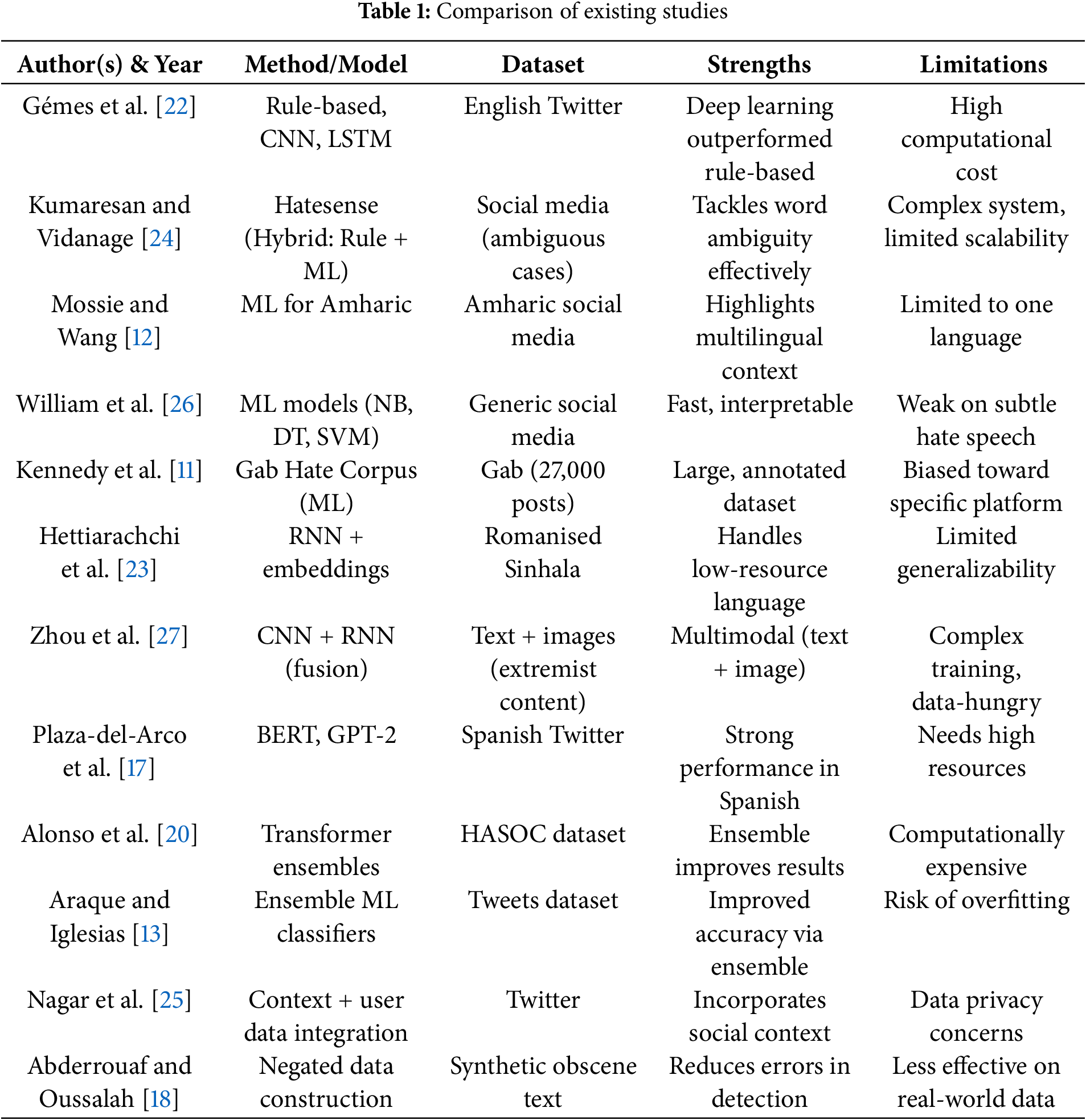

Arcila-Calderón et al. [9] explored online hate speeches, including the feelings expressed on the Spanish Twitter platform during the Aquarius’s arrival. According to this study, immigrants and refugees were the targets of widespread hate speeches. The authors suggested that social media platforms should be developed in a way to combat hate speech and spread positive messages. By studying the power of the arts and arts education to combat hate speech, Jääskeläinen [10] found that these disciplines can encourage acceptance and understanding of one another’s differences. As part of the fight against hate speech, it was suggested that arts education be included. After annotating 27,000 posts for hate speech, Kennedy et al. [11] created the Gab Hate Corpus. The research showed that hate speech targeting marginalized groups was on Gab every day. To help social media networks in better identifying hate speeches, the Gab Hate Corpus was suggested. Mossie and Wang [12] proposed a method to determine hate speech on social media in Amharic. Although their research works did good job by drawing attention to the variety of languages spoken, it deals with only one language.

A new ensemble strategy for monitoring the internet for symptoms of radicalization and hate speech has been introduced in a research study [13]. The research integrates numerous machine learning classifiers to improve accuracy in sentiment analysis. The research found encouraging precision and recall results when testing the proposed method on a tweets dataset. This study employed a transformer-based encoder for recognizing and categorizing hateful speech in Arabic texts. An advanced Seagull Optimization Algorithm based on NLP technique is presented. The study proposes a method to obtain higher accuracy and F1-score by validating it on a dataset of tweets with the extracted features from the word embedding. The authors in [14] stated that a transfer learning-based approach, such as BERT, is better in detecting hate speech. The BERT models has been evaluated on tweets dataset. This shows better performance and competitiveness compared to other models in giving us extensive experimental results [15]. Pariyani et al. [16] approached this by employing language flow analysis and NLP. The proposed research aimed to find hate speech tweets from Twitter. They used a technique for representational learning based on word embedding and machine learning that classifies tweets into a hateful or non-hateful class. The method relies upon a set of tweets and obtains strong performance in the assessment.

Post analysis was conducted, where a multimodal approach was used for the detection of hate speech. This technique uses textual, visual, and auditory elements. It shows good accuracy when tested on a Facebook dataset. Plaza-del-Arco et al. [17] explored pre-trained language models like BERT and GPT-2, which are effective for hate speech detection in Spanish text, using Spanish Twitter posts. Results show that the models are surprisingly accurate in hate speech detection, with BERT outperforming all other models.

Abderrouaf and Oussalah [18] investigated the consequences of finding hate speech online, utilizing negated data construction. To improve hate speech identification methods, they suggested to create the fictitious instances of the obscene language. Results demonstrated that negated data was helpful in hate speech detection algorithms. Using genetic programming, Aljero and Dimililer [19] investigated hate speech identification. By optimizing traits and using classifiers with the genetic algorithm, they were able to identify hate speech examples more accurately than the tconventional machine learning methods.

Alonso et al. [20] explored the application of transformer ensembles for hate speech identification on the HASOC dataset. To perform mean extraction from text, they utilized a transformer model such as BERT. They improved the accuracy of hate speech identification by using a collection of different transformer models. To categorize hate speech on Twitter, Ayo et al. [21] put forward a probabilistic clustering methodology. Twitter sets containing similar expressions of hate were compiled using topic modelling. The model did a good job of grouping hate speech incidents on Twitter, which is encouraging.

To detect offensive tweets on English Twitter, Gémes et al. Use of rule-based systems and deep learning models [22]. Compared a rule-based system with a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network. The results suggested that the deep learning models (CNN and LSTM) were better than the rule-based system at predicting offensive content.

Hettiarachchi et al. [23] explored the instances of hate speech from Romanized Sinhala on social media, the widely spoken language of Sri Lanka. The proposed research work aimed to address the challenges in processing such text using machine learning based approaches. The proposed research utilized word embedding and recurrent neural networks for hate speech detection. Supported by experimental results, their method effectively identifies hate speech in online content. The concept of “Hatesense,” which was presented by Kumaresan and Vidanage [24], introduces “Hatesense” to tackle ambiguity in hate speech classification. They discuss differentiating words with multiple meanings for hateful or non-hateful intent, proposing a hierarchical classifier merging rule-based and machine learning techniques. Experimental comparisons demonstrate Hatesense’s superiority over recent methods in accurately identifying hate speech.

Nagar et al. [25] proposed a hate speech detection method that enhances accuracy through the social context and users’ data integration. They highlight the influence of the social setting on hate speech perception and impact, particularly in recurring incidents. The study introduces a comprehensive framework amalgamating network-based attributes, user behavior, and textual content for hate speech detection. Experimental results affirm the method’s effectiveness in enhancing hate speech detection accuracy by incorporating contextual information.

William et al. [26] used ML models for an automated hate speech recognition approach. This study centers on ML algorithms such as NB, Decision Trees (DT), and support vector machines for hate speech classification. A wide range of feature sets and classifiers is explored to determine the optimal configuration. Results suggest that the ML techniques may be applied as valuable tools for accurate and timely recognition of hate speech. Zhou et al. [27] presented a fusion strategy based on deep learning techniques for hate speech detection. Using CNNs and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to address issues of prediction and classification of textual and image information, the authors aimed to detect hate contents from speeches. Real-world experiments validate the experimental superiority of the fusion method of detection of hate speech.

As illustrated in Table 1, current studies differ significantly in terms of methods, dataset and performance. However, most are heavily biased towards accuracy, are language-or platform specific or have high computational requirements. This encourages the present study to benchmark classical ML algorithms using ample-specific informative metrics using a balanced dataset.

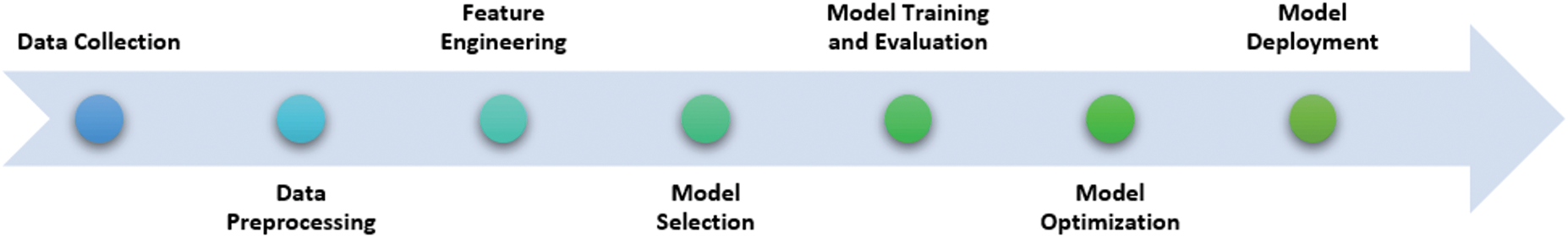

The goal of this study is to use machine learning approaches that can identify and report hate speech with higher accuracy. The process flow of methodology employed in this research is demonstrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Process flow of the proposed research method

Normalized and annotated datasets were collected from the Kaggle platform, which is ideal for ML-based applications. The dataset consists of samples of text labelled as hate speech, non-hate speech, and samples placed within a borderline context. These annotations are essential for preparing the model to identify offensive and non-offensive text. The dataset diversity was ensured by thoroughly analyzing it to capture different kinds of lingual forms, cultural nuance and expression forms.

The data collected was preprocessed by cleaning and structuring the text to be more suitable for machine learning algorithms. It started with the raw text being cleaned of unwanted data such as URLs, memorable characters, and additional whitespace. All the text was lowercased to ensure consistency in the dataset. The text was tokenized to convert it into separate words or tokens for further analysis. High-frequency stopwords, which add less contextual value and most likely would not help in differentiating the relevance of the paper to search terms (e.g., “and” “is” “the”), were removed. In addition, to achieve consistency of word representation, stemming techniques and lemmatization techniques were applied on the word to reduce it to its base form (such as converting “running” into “run”).

We employed feature engineering to extract and enhance the meaningful features from textual data. The purpose was to boost the model in classifying hate speech. For the textual data, N-grams are used for sequences of words or characters, to identify the surrounding context relations. We used word embedding, like pre-trained GloVe vectors, to depict the words in a dense vector space. The semantic association between words is captured to understand the context of words. Lexical features, including document length, punctuation, and capitalization, were created as extrinsic features to aid in the classification of hate vs. non-hate speech. Text sentiment analysis is performed to analyzing the emotional tone of textual data. In this case, possible hate speech was screened based on the text being offensive or vulgar, detecting periods of hostility or profanity.

ML algorithms, including DT, K-Nearest Neighbours, LR, and RF, were evaluated for their ability to detect hate speech. For this binary classification problem, we have settled on LR, one of the most straightforward and effective linear model. We included RF, an ensemble approach that uses multiple decision trees, for its ability to capture complex interactions in high-dimensional data. The DT baseline results for the sake of interpretability, and K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN), being a similarity-based measure, was evaluated to compare baseline accuracy with more sophisticated algorithms. These models were specifically selected so that the strengths and weaknesses of detecting hate speech could be appropriately compared.

3.5 Model Training and Evaluation

The dataset was preprocessed and divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets. The models learned from the patterns presented in the training and were evaluated on unseen data. Various cross-validation strategies were used to confirm the model’s generalization and further minimize overfitting risk. Performance evaluation metrics such as F1-score, recall, precision, and accuracy were used in this study.

The baseline models were then tuned to increase their accuracy. Feature extraction was carried to select the most informative features and apply dimension reduction with feature selection measures (i.e., chi-squared test and L1 regularization). Optimal parameters of each algorithm such as the depth of decision trees or the number of estimators in RF were obtained by grid search and Bayesian optimization. This made sure that the models were highly accurate and reliable.

The optimized models were used for practical applications with either an interactive user interface or using APIa. The code buys a configuration of a classifier that receives some text data as input and produces truth values based on the classification of hate speech or not. The primary considerations during deployment included scalability (a required capacity to analyze large amounts of data in a close to near real-time fashion), and adaptability (a need to constantly monitor shifts in the language and to learn new forms of hate speech usage).

The model’s performance is primarily assessed based on accuracy. The accuracy formula is given by:

In addition to the accuracy, we also report the Precision, Recall and F1-score results in the present study.

4 Experiments, Results and Discussion

The experiments were carried out using Jupiter notebooks on a computer with 512 GB SSD and 8 GB specifications. Several experiments were performed using machine learning algorithms. Fine-tuning of algorithms was performed on the Kaggle dataset as described below.

Hate speech dataset was downloaded from Kaggle [28]. The hate speech dataset is hosted on Kaggle, comes from Andrii Samoshyn and was built for a text classification task to detect toxicity in speech content. It contains 25,904 labelled tweets as being toxic (1) and non-toxic (0) (a binary classification task). This dataset is relevant for this study since tweets contain informal language, including slang, abbreviations and types common for social media. Each of the tweets in the collected dataset has been labelled yes or no to indicate how many of them include hate speech. Of those, 6779 were considered non-toxic (0) and 18,975 toxic (1), thus forming a problem of classification with two classes. Preprocessing included stripping away URLs, special characters and excess whitespace, down casing the text, and tokenization of the text using TweetTokenizer. Stop words were dropped and the language was normalized by carrying out stemming and lemmatization to make words uniform in representation. The diversity in the dataset can be seen from the examples, including explicit hate, neutral, and borderline cases. Secondly, the datasets were specially balanced to avoid biases and ensure better model performance.

Although the dataset provides valuable insights, it has certain limitations. First, it uses a binary classification scheme (toxic vs. non-toxic), which may not capture the full nuance of hate speech such as sarcasm, implicit bias, or targeted group severity. Second, the dataset is primarily sourced from Twitter, which may introduce social media bias and limit generalizability to other platforms or languages. Future studies should explore multi-class and multilingual datasets to ensure broader applicability.

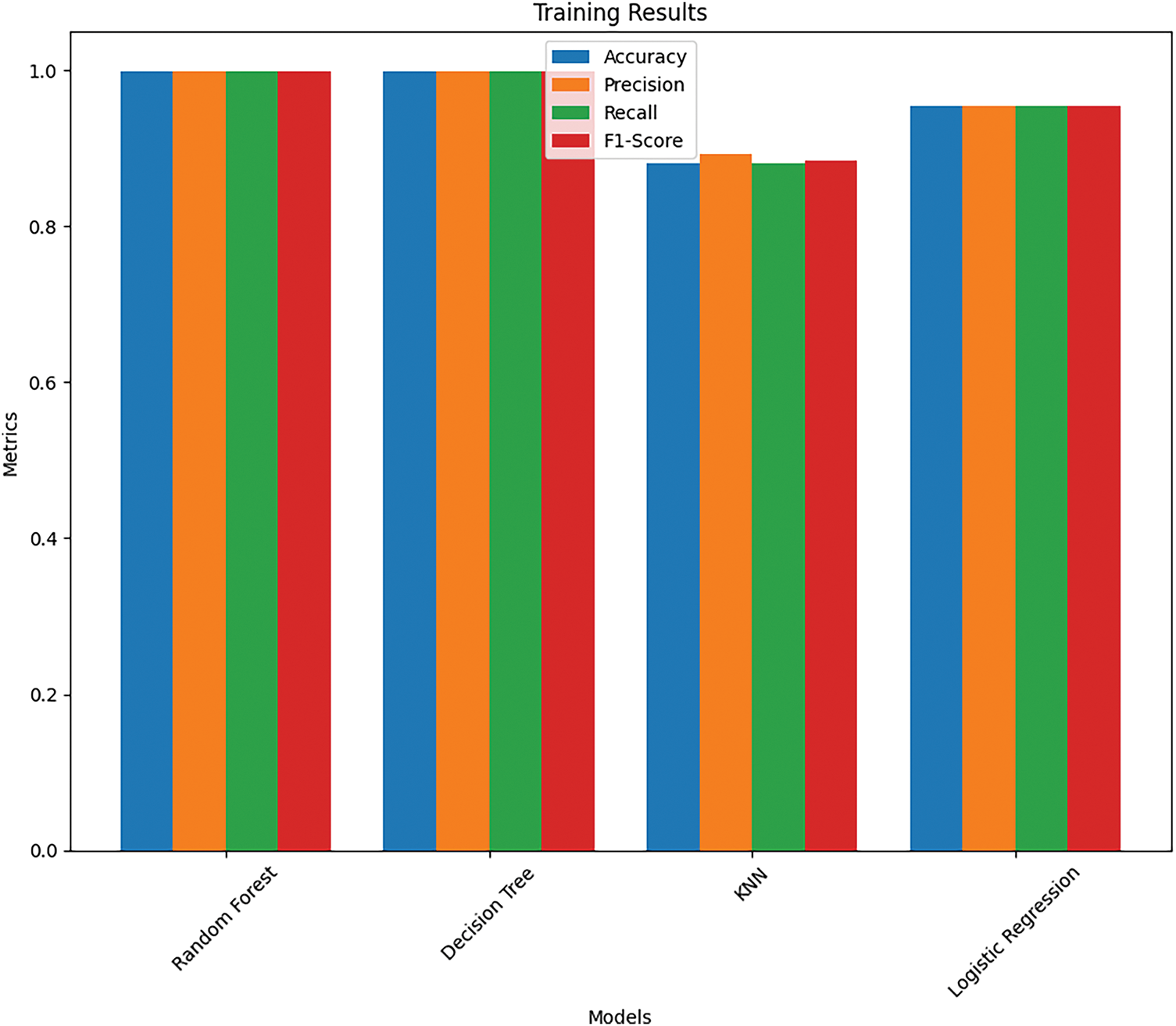

This section presents results that can be interpreted from the four ML approaches used in this study. RF shows training accuracy of 99.96% proving that the proposed model is practical in hate speech detection if implemented in time and skillful ways (see Fig. 2). We usually obtain the best results for ML algorithms such as RF and LR, DT and KNN classifiers. Other performance metric results are given in the following Table 2.

Figure 2: Training results

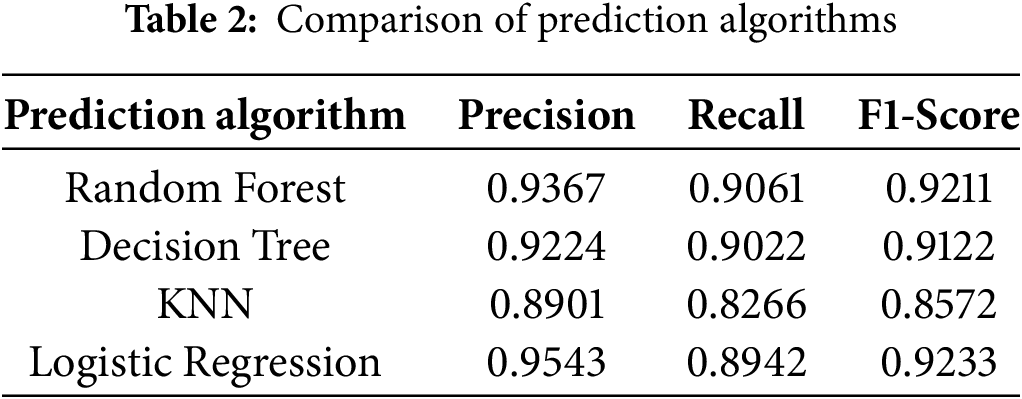

Table 2 provides us the performance metric results of four prediction models, using precision, recall and F1-Score. Fig. 2 shows us the training accuracy results for the four classifiers studied.

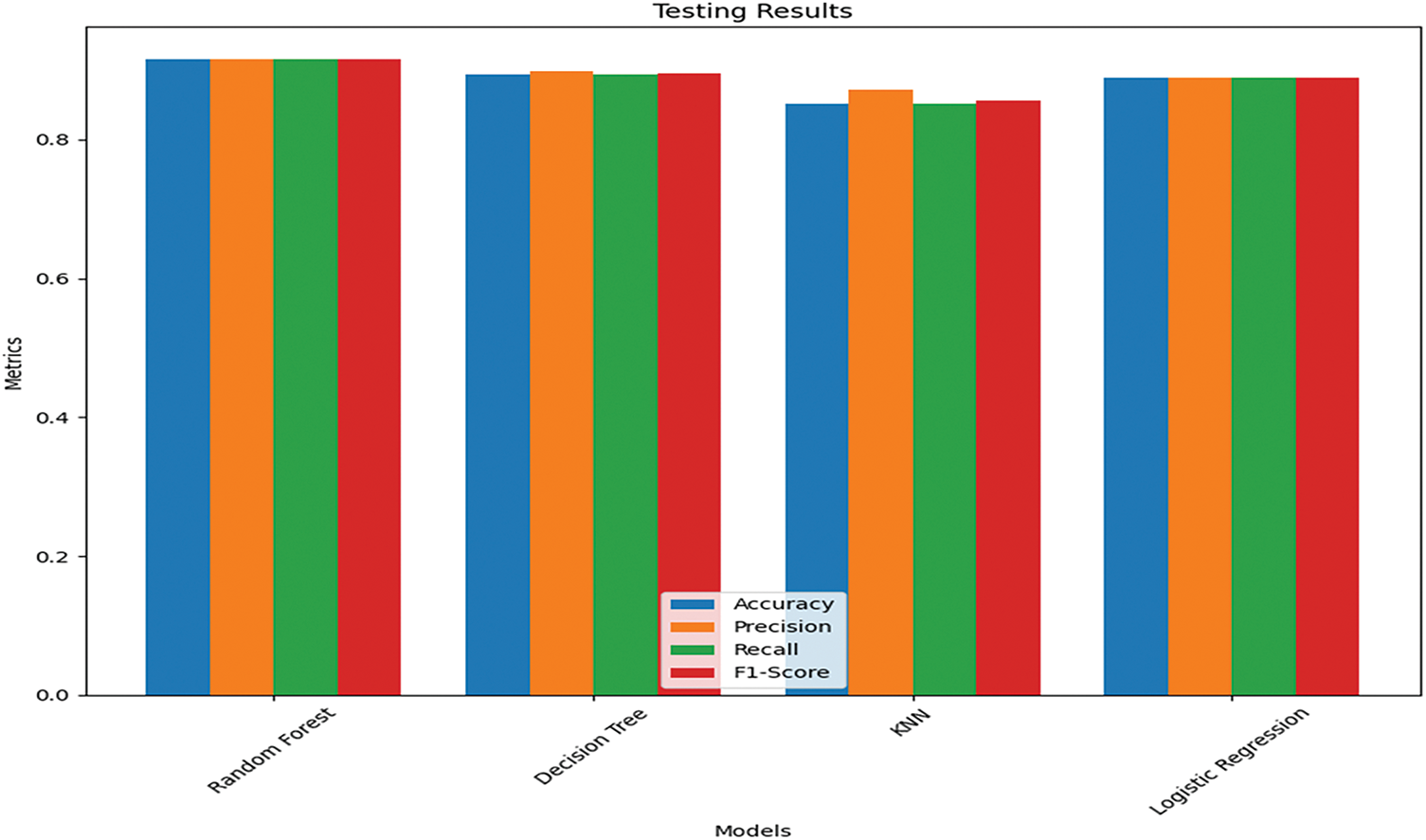

Fig. 3 shows the outcomes of the algorithms that were tested for accuracy. RF and LR outperformed DT and KNN algorithms, as demonstrated in Fig. 3. LR has a test accuracy of 93.66%, while RF shows 93.388% accuracy results.

Figure 3: Testing results

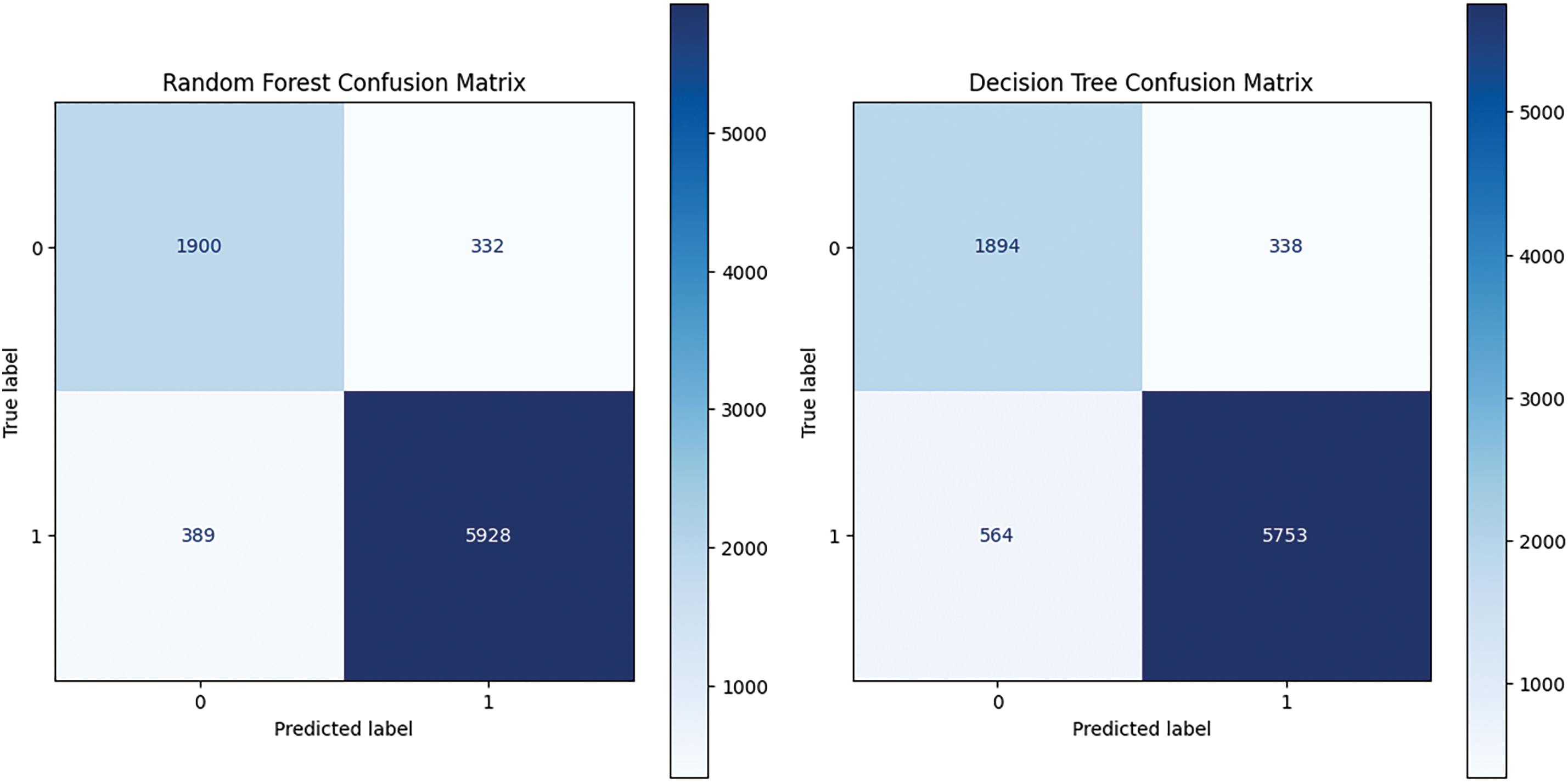

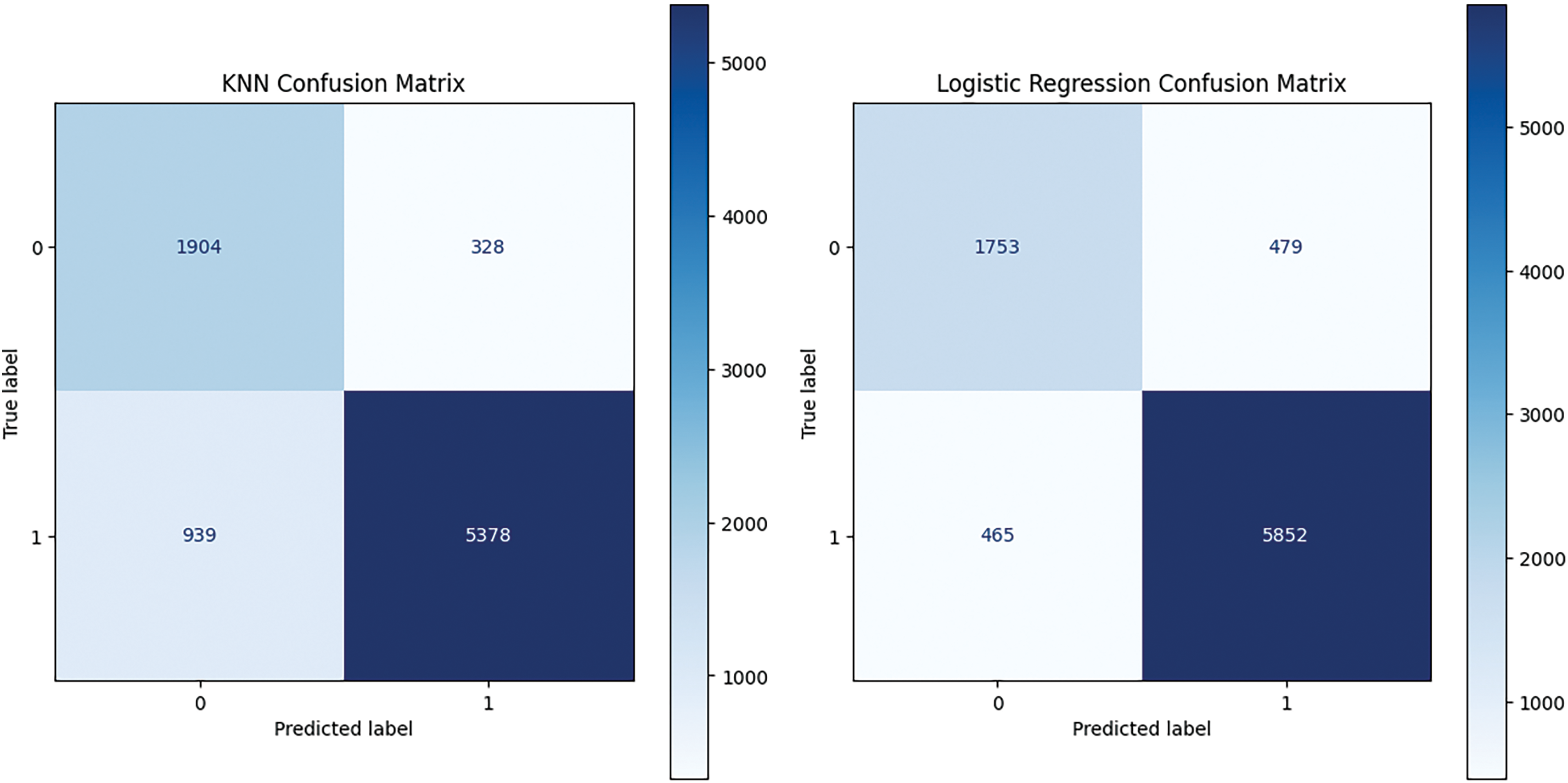

The confusion matrix for all algorithms is mentioned in Fig. 4:

Figure 4: Confusion matrix of classification algorithms

RF and LR resulted in at least misclassifications, while DT and KNN are behind these models in performance. We can see that RF produces 332 false positives and 389 false negatives, which means that RF has an equal capacity to manage hate speech and non-hate speech. On the other hand, the LR model shows a bit higher false positive (479), but lower false negatives (465), indicating that it is leaning more towards classifying a comment as hate speech, but with more overclassification. In contrast, DT produces a false negative (564), which means that it might have trouble picking up all hate speech inatnces. KNN then gives us a lot of false negatives (939), severely harming its ability to identify hate speech. In summary, the confusion matrices illustrate the relative advantages and disadvantages of each model, with LR and RF performing more reliably on the datasets. The ROC curve of ML models used in this study is shown in Fig. 5.

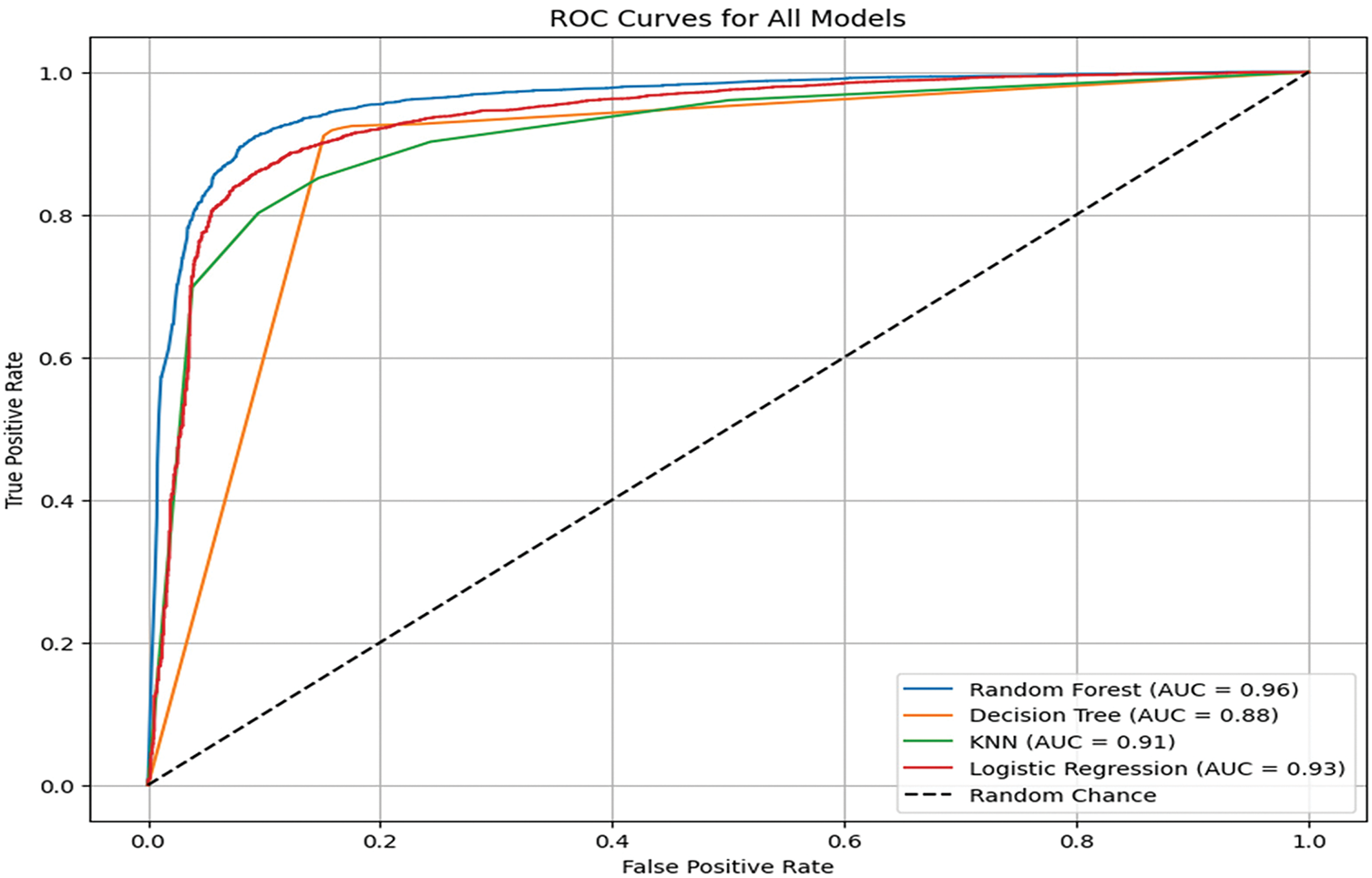

Figure 5: ROC curve of classification algorithms

RF has the highest area under the curve (AUC = 0.96), which indicates that it is one of the best classifiers to distinguish between hate and non-hate speech datasets. Logistic Regression, with AUC = 0.93, received a fair classification performance. Next is KNN with an AUC of 0.91, and DT has the lowest AUC of 0.88, meaning that it is not as good as keeping the sensitivity to specificity balance.

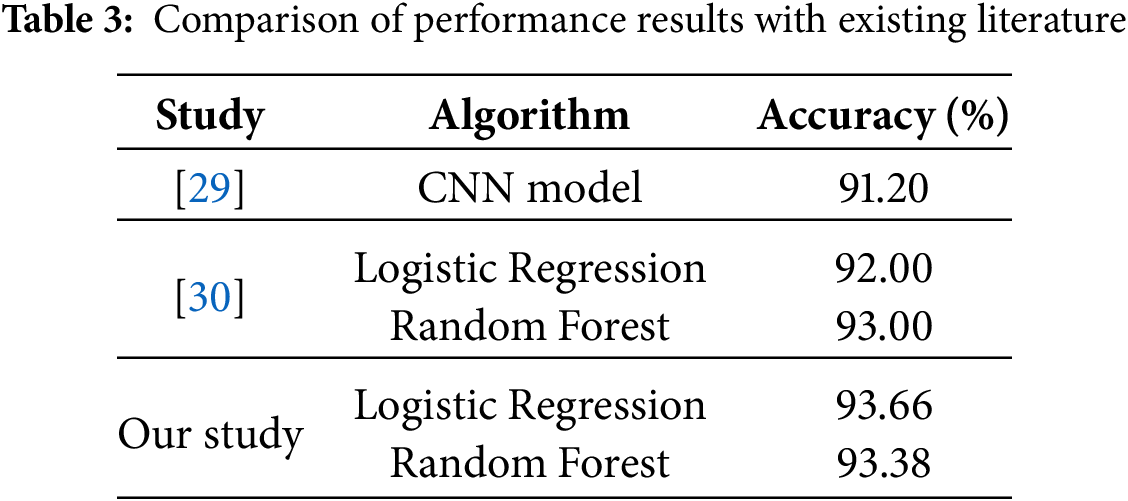

According to Table 3, this study significantly shows improvement compared to previous studies in terms of identifying hate speech. The RF and LR models in the present study outperform most of the previous research studies due to their higher accuracy. Results from this study’s comparisons and contrasts with other algorithms demonstrate that LR and RF are the most suitable machine learning algorithms for this task. Other ML algorithms include DT, and KNN.

This novelty lies in offering a thorough and reproducible benchmarking of multiple machine learning algorithms for hate speech detection, rather than the previous work having either reported accuracy only or been restricted to one model at a time. By systematically comparing LR, RF, DT, and KNN with a variety of metrics (e.g., precision, recall, F-1 score, and confusion matrix), this work demonstrates that conventional ML models with proper optimization can exceed prior published performance and even can compete with the deep learning models. This study involves important ethical and practical considerations for implementing such systems (for example, issues of dataset bias, cultural applicability and cultures danger), and for this reason, we approach our contribution not merely as a technical innovation but as a step in the right direction towards proactive AI for common good.

Findings of this research underline profound implications of hate speech on individuals, communities and societies which may be widespread and, potentially, harmful. The results show that detecting hate speech certainly can create less violence and a more cohesive community. Nonetheless, the rate of such cases is difficult to find because of the massive data, false positives and negatives, as well as a culturally and socially context-specific definition of hate speech.

With the models having been optimally harmonic opinionated in this study, these stand by for deploying. These models can be considered as workable application of hatred detection in text data as it allows users to place text data and predict to detect the presence of hatred. Such models need to be updated on a regular basis and inspected since language is dynamic and new forms of hate speech appear. This study provides important implications, since it enhances our knowledge of hate speech detection and the impact on society and sheds light on difficulties in defining and combating hate speech: the fight for online spaces and public debates, in particular. These results underscore the importance of context specific approaches and targeted strategies to reflect the diversity of characteristics and complexities of communities.

This study presents the successful implementation of ML algorithms for hate speech detection in the cyber sphere. The ML models are perfect in reporting hateful and abusive content, which can help to lessen the impact of hate speech, such as violence and social discord. These systems can help the formation of a feeling of acceptance among people, thus they can create healthier, safer, more inclusive communities by reducing the injurious messages.

This paper considers key ethical and practical issues around the deployed use of hate speech detection systems. Mental health datasets are notoriously hard and expensive to collect, issues of onward research remain as important as ever: concerns of bias, cultural and linguistic differences, and risks of censorship are major barriers to overcome before any of this technology is a realistic application. Therefore, future research should be focused on multilingual data, fairness-conscious models, and explainability methods of AI systems for effective the responsible use of AI models. Future work will explore fine-grained hate speech categorization (e.g., racist, sexist, political) and the integration of sentiment-shift and context-aware transformers to handle evolving linguistic trends.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper are as follows: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Ayaz Hussain; Methodology, Asad Hayat; Software and Validation, Muhammad Hasnain. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Muhammad Hasnain, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gover AR, Harper SB, Langton L. Anti-Asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the reproduction of inequality. Am J Crim Justice. 2020;45(4):647–67. doi:10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Saha K, Chandrasekharan E, De Choudhury M. Prevalence and psychological effects of hateful speech in online college communities. In: Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science; 2019 Jun 26; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2019. p. 255–64. [Google Scholar]

3. Castaño-Pulgarín SA, Suárez-Betancur N, Vega LMT, López HMH. Internet, social media and online hate speech systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2021;58(6):101608. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2021.101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mossie Z, Wang J-H. Vulnerable community identification using hate speech detection on social media. Inf Process Manag. 2020;57(3):102087. doi:10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ullmann S, Tomalin M. Quarantining online hate speech: technical and ethical perspectives. Ethics Inf Technol. 2020;22(1):69–80. doi:10.1007/s10676-019-09516-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Srba I, Lenzini G, Pikuliak M, Pecar S. Addressing hate speech with data science: an overview from computer science perspective. In: Wachs S, Koch-Priewe B, Zick A, editors. Hate speech-multidisziplinäre analysen und handlungsoptionen: theoretische und empirische annäherungen an ein interdisziplinäres phänomen. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 317–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-31793-5_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Farrell A, Lockwood S. Addressing hate crime in the 21st century: trends, threats, and opportunities for intervention. Annu Rev Criminol. 2023;6(1):107–30. doi:10.1146/annurev-criminol-030920-091908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Argyrou A, Agapiou A. A review of artificial intelligence and remote sensing for archaeological research. Remote Sens. 2022;14(23):6000. doi:10.3390/rs14236000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Arcila-Calderón C, Blanco-Herrero D, Frías-Vázquez M, Seoane-Pérez F. Refugees welcome? Online hate speech and sentiments on twitter in Spain during the reception of the boat Aquarius. Sustainability. 2021;13(5):2728. doi:10.3390/su13052728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jääskeläinen T. Countering hate speech through arts and arts education: addressing intersections and policy implications. Policy Futures Educ. 2020;18(3):344–57. doi:10.1177/1478210319848953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kennedy B, Atari M, Davani AM, Yeh L, Omrani A, Kim Y, et al. The gab hate corpus: a collection of 27k posts annotated for hate speech. PsyArXiv. 2018;18:1–47. [Google Scholar]

12. Mossie Z, Wang JH. Social network hate speech detection for the Amharic language. Comput Sci Inf Technol. 2018;28:41–55. [Google Scholar]

13. Araque O, Iglesias CA. An ensemble method for radicalisation and hate speech detection online, empowered by sentiment computing. Cogn Comput. 2022;14(1):48–61. doi:10.1007/s12559-021-09845-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Mozafari M, Farahbakhsh R, Crespi N. A BERT-based transfer learning approach for hate speech detection in online social media. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Complex Networks and Their Applications; 2019 Nov 26; Cham, Switzerland; 2019. p. 928–40. [Google Scholar]

15. Vidgen B, Yasseri T. Detecting weak and strong Islamophobic hate speech on social media. J Inf Technol Politics. 2020;17(1):66–78. doi:10.1080/19331681.2019.1702607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Pariyani B, Shah K, Shah M, Vyas T, Degadwala S. Hate speech detection in twitter using natural language processing. In: Proceedings of the 2021 Third International Conference on Intelligent Communication Technologies and Virtual Mobile Networks (ICICV); 2021 Feb 4; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2021. p. 1146–52. [Google Scholar]

17. Plaza-del-Arco FM, Molina-González MD, Urena-López LA, Martín-Valdivia MT. Comparing pre-trained language models for Spanish hate speech detection. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;166(3):114120. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Abderrouaf C, Oussalah M. On online hate speech detection. Effects of negated data construction. In: Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data); 2019 Dec 9; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 5595–602. [Google Scholar]

19. Aljero MK, Dimililer N. Hate speech detection using genetic programming. In: Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Advanced Science and Engineering (ICOASE); 2020 Dec 23; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

20. Alonso P, Saini R, Kovács G. Hate speech detection using transformer ensembles on the hasoc dataset. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Speech and Computer; 2020 Sep 29; Cham, Switzerland. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

21. Ayo FE, Folorunso O, Ibharalu FT, Osinuga IA, Abayomi-Alli A. A probabilistic clustering model for hate speech classification in twitter. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;173(1):114762. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gemes KA, Kovács Á, Reichel M, Recski G. Offensive text detection on English Twitter with deep learning models and rule-based systems. In: Mehta P, Mandl T, Majumder P, Mitra M, editors. FIRE-WN, 2021 [FIRE, 2021 Working Notes]; 2021 Dec 13–17; Gandhinagar, India: CEUR-WS.org; 2021. p. 283–96. [Google Scholar]

23. Hettiarachchi N, Weerasinghe R, Pushpanda R. Detecting hate speech in social media articles in romanized sinhala. In: Proceedings of the 2020 20th International Conference on Advances in ICT for Emerging Regions (ICTer); 2020 Nov 4; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 250–55. [Google Scholar]

24. Kumaresan K, Vidanage K. Hatesense: tackling ambiguity in hate speech detection. In: Proceedings of the 2019 National Information Technology Conference (NITC); 2019 Oct 8; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 20–6. [Google Scholar]

25. Nagar S, Barbhuiya FA, Dey K. Towards more robust hate speech detection: using social context and user data. Soc Netw Anal Min. 2023;13(1):47. doi:10.1007/s13278-023-01051-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. William P, Gade R, Esh Chaudhari R, Pawar AB, Jawale MA. Machine learning based automatic hate speech recognition system. In: Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS); 2022 Apr 7; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 315–18. [Google Scholar]

27. Zhou Y, Yang Y, Liu H, Liu X, Savage N. Deep learning based fusion approach for hate speech detection. IEEE Access. 2020;8:128923–9. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3009244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Iyer AU. Toxic tweets dataset [Internet]. San Francisco, CA, USA: Kaggle Inc. [cited 2025 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ashwiniyer176/toxic-tweets-dataset. [Google Scholar]

29. Georgakopoulos SV, Tasoulis SK, Vrahatis AG, Plagianakos VP. Convolutional neural networks for twitter text toxicity analysis. In: Proceedings of the INNS Big Data and Deep Learning Conference; 2019 Apr 3; Cham, Switzerland. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2019. p. 370–9. [Google Scholar]

30. Costales JA, Christian M, Catulay JJ, Albino MG. Sentiment analysis for twitter tweets: a framework to detect sentiment using naïve bayes algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Computer Communication and the Internet (ICCCI); 2022 Jul 1; Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2022. p. 39–44. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools