Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Calibrating Trust in Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Human-Centered Testing Framework with Adaptive Explainability

1 School of Computer Science, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210044, China

2 School of Aritificial Intellence, Nankai University, Tianjin, 300350, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhenjie Zhao. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 517-547. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.072628

Received 31 August 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) systems have achieved remarkable capabilities across text, code, and image generation; however, their outputs remain prone to errors, hallucinations, and biases. Users often overtrust these outputs due to limited transparency, which can lead to misuse and decision errors. This study addresses the challenge of calibrating trust in GenAI through a human centered testing framework enhanced with adaptive explainability. We introduce a methodology that adjusts explanations dynamically according to user expertise, model output confidence, and contextual risk factors, providing guidance that is informative but not overwhelming. The framework was evaluated using outputs from OpenAI’s Generative Pretrained Transformer 4 (GPT-4) for text and code generation and Stable Diffusion, a deep generative image model, for image synthesis. The evaluation covered text, code, and visual modalities. A dataset of 5000 GenAI outputs was created and reviewed by a diverse participant group of 360 individuals categorized by expertise level. Results show that adaptive explanations improve error detection rates, reduce the mean squared trust calibration error, and maintain efficient decision making compared with both static and no explanation conditions. The framework increased error detection by up to 16% across expertise levels, a gain that can provide practical benefits in high stakes fields. For example, in healthcare it may help identify diagnostic errors earlier, and in law it may prevent reliance on flawed evidence in judicial work. These improvements highlight the framework’s potential to make Artificial Intelligence (AI) deployment safer and more accountable. Visual analyses, including trust accuracy plots, reliability diagrams, and misconception maps, show that the adaptive approach reduces overtrust and reveals patterns of misunderstanding across modalities. Statistical results confirm the robustness of these findings across novice, intermediate, and expert users. The study offers insights for designing explanations that balance completeness and simplicity to improve trust calibration and cognitive load. The approach has implications for safe and transparent GenAI deployment and can inform both AI interface design and policy development for responsible AI use.Keywords

Generative AI systems have moved from research curiosities to everyday tools, producing text, images, code, and multimedia at a scale previously unimaginable [1]. With that ubiquity has come a troubling pattern: users frequently attribute more reliability to these systems than is warranted by their actual performance. High-profile incidents such as language models fabricating legal citations that were subsequently filed in court, or image generators amplifying social and demographic biases in seemingly neutral prompts, underscore a core tension between capability and dependability [2]. These failures are not merely technical glitches; they are human–AI interaction breakdowns that manifest when people overtrust fluent outputs, misread model confidence, or lack actionable support to verify claims [3–5]. As organizations explore the use of generative models in domains touching safety, compliance, and high-stakes decision making, calibrating human trust to match model reliability is no longer optional; it is central to responsible deployment [6].

This paper addresses the discrepancy between actual model reliability and user trust, a gap we term trust miscalibration. Trust miscalibration is bidirectional: users may overtrust, accepting incorrect outputs without sufficient scrutiny, or undertrust, discarding correct outputs and duplicating effort [7]. Both failure modes carry costs: errors propagate when detection fails, while productivity and innovation suffer when warranted reliance is withheld. Conventional benchmarking practices, while indispensable, do not capture these human factors [8]. Leaderboards report aggregate accuracy or perplexity in carefully curated settings, but they rarely reflect how non-expert and expert users perceive, interrogate, and act upon generative outputs under realistic task constraints, time pressure, or domain risk [9]. Bridging this gap requires evaluation methods that integrate model-centric metrics with user-centric behaviors and outcomes.

Generative outputs are increasingly used in high-stakes settings such as healthcare, law, and engineering, where trust miscalibration can have severe consequences [10]. In clinical workflows, for example, an incorrect but persuasive model suggestion may delay correct diagnosis or treatment [11]; in legal contexts, a hallucinated citation or misrepresented precedent can mislead case preparation or adjudication [12]; and in engineering domains, erroneous design suggestions can introduce safety-critical failures [13]. By explicitly targeting trust calibration rather than only model accuracy, our framework aims to reduce the probability that users will accept incorrect outputs in such environments. The empirical gains reported here (e.g., up to a 16% increase in error detection) therefore translate into tangible risk reductions in domains where human verification is required before action.

Our study is structured around three intertwined questions. First, how do users perceive and validate generative outputs when placed in realistic review tasks that include both correct and incorrect model responses? Second, can focused explainability interventions help to reduce misconceptions by exposing potential error modes, disclosing ambiguity, or aligning explanations with a user’s domain expertise? Third, how does a human-centered testing framework with adaptive explanations compare to common baselines in both usability (time-to-decision, cognitive load) and effectiveness (error detection, calibrated trust)? These questions reflect both a measurement agenda, which captures what users do, and an intervention agenda, which shapes what they should do to improve outcomes.

Our approach is to place the human firmly in the loop of evaluation and improvement. We propose a testing framework that couples a structured review task with an error-detection module and an adaptive explainability engine. Rather than treating explainability as a static, one-size-fits-all artifact, our system modulates the form and depth of explanations based on three factors: the estimated likelihood that a given output contains an error, the user’s demonstrated or declared expertise, and the contextual risk of the decision at hand. This adaptive mechanism embodies a pragmatic view of explainability: it is not an end in itself, but a means to help users allocate attention, verify claims when needed, and maintain appropriate reliance on the system. Grounded in principles from Human–Computer Interaction (HCI), particularly Norman’s emphasis on feedback, visibility, and mapping [14,15]. The framework treats explanations as part of the task environment, tuned to support timely and accurate decisions rather than to merely satisfy post-hoc transparency desiderata.

The core technical contribution of this work lies in the integration of adaptive explainability with trust calibration, operationalized through three key modules: (i) an Error Detection Module (EDM) that prioritizes suspicious outputs using lightweight heuristics and probabilistic checks, (ii) an Adaptive Explainability Engine (AEE) that dynamically adjusts the level of explanation according to user profile and task sensitivity, and (iii) a Human-in-the-Loop Evaluation Pipeline that systematically collects user feedback to refine both the error model and the explanation policies. Together, these components establish a closed-loop system where explanations are not fixed artifacts but adaptive interventions that evolve with the model state and the user context.

This approach is motivated by a persistent gap in current generative AI systems: while state-of-the-art models such as GPT-4 and Stable Diffusion can generate highly realistic outputs across text and image modalities, they frequently produce subtle errors that are difficult for non-expert users to detect. Static explainability tools such as saliency maps or generic confidence scores offer limited practical utility in such contexts, often overwhelming users with technical detail or, conversely, failing to highlight actionable insights. On the other hand, our adaptive framework improves efficiency and trust by customizing explanations to the user’s needs and the stakes of the decision. Because it reframes explainability as a dynamic and user-centered tool for error detection, attention allocation, and calibrated reliance rather than as a “post-hoc justification,” this addition is significant.

The contributions of this work are threefold. We introduce a human-centered generative AI testing methodology that uses curated tasks with mixed-ground-truth outputs to measure error detection, misconception patterns, and trust calibration. This model-agnostic methodology is designed for extensibility across domains. We then present an adaptive explanation generation algorithm that uses contextual risk, model confidence, and user expertise to select and parameterize explanation types, such as evidence, rationales, or uncertainty cues. By formalizing trust calibration as an optimization objective, the algorithm enables principled comparison with static and no-explanation baselines. Finally, we provide empirical evidence from a controlled study with over one hundred participants, showing improvements in error detection and reduced overtrust without prohibitive time costs. Together, these contributions highlight the value of human-centered and intervention-aware evaluation for generative systems.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work in generative AI testing, human–AI trust, and explainability tools, with a comparative table summarizing key differences in scope, user involvement, and performance metrics. Section 3 presents our proposed method, including the human-centered rationale, framework architecture, adaptive explanation algorithm, and trust calibration model. Section 4 reports experimental results, comparing our approach to static and no-explanation baselines, supported by statistical analyses and visualizations. Section 5 discusses insights, design guidelines, and limitations, while Section 6 concludes with implications for safe, usable generative AI and future research directions.

A thorough literature analysis on this subject must balance breadth and depth, situating our work at the intersection of benchmarking, Human–Computer Interaction (HCI), and algorithmic explainability. We begin with benchmarks because they establish standardized methods for evaluating generative AI systems at scale, highlighting where current evaluations succeed but also where they fail to capture human trust calibration in practice. We then turn to HCI studies of trust, which directly investigate how people interact with AI outputs, shedding light on phenomena such as overreliance, workload, and shifting mental models; these findings are directly relevant to our research question of how to design evaluation frameworks that reflect real user decision-making. Finally, we examine explainability methods, which promise actionable transparency and are often assumed to improve trust. Yet their instability, misinterpretability, or lack of fidelity can inadvertently inflate misplaced confidence. By integrating insights from these three strands, we position our framework as a response to the gaps: unlike benchmarks that ignore users, HCI studies that lack scalability, or explainability methods that remain static, our approach explicitly targets trust calibration as an evaluative outcome.

2.1 Generative AI Testing and Benchmarks

Large-scale evaluation frameworks for generative AI models have advanced rapidly in recent years, aiming to standardize assessment across tasks and domains. Liang et al. [16] proposed the Holistic Evaluation of Language Models (HELM), which expanded evaluation beyond accuracy to include calibration, robustness, fairness, and toxicity. HELM’s greatest contribution is breadth: it allows side-by-side comparison of Large Language Models (LLMs) using a consistent protocol, giving developers and policymakers visibility into system-level trade-offs. However, HELM remains system-centric. It measures how well models perform on tasks without integrating human judgment or considering the interactive nature of trust.

In parallel, specialized benchmarks target factual reliability. TruthfulQA (Lin et al. [17]) probes models with adversarial prompts to reveal systematic falsehoods, especially where models overgeneralize or hallucinate. While this provides a precise diagnostic of model weaknesses, it remains narrow in both scope (QA-focused) and perspective (system-only). Similarly, other emerging benchmarks have introduced adversarial robustness [18], toxicity detection [19], and fairness across demographic subgroups [20]. Despite their variety, these approaches share the same limitation: they evaluate models as closed systems rather than in partnership with users. As such, they reveal when models “go wrong” but not whether humans detect, correct, or adapt to those errors in practice. This limitation motivates the need to examine human-centered perspectives. If benchmarks alone cannot capture how trust is calibrated in real use, we must turn to studies of human–AI interaction, where user judgment, reliance, and adaptation are foregrounded.

In addition to these general benchmarks, domain-specific evaluations further highlight how generative models behave in application settings and underscore the same limitations. Research on legal document automation and Large Language Model (LLM) assisted contract review has reported both productivity gains and potential failure cases that may generate misleading evidence if not properly verified [21]. In clinical contexts, evaluations of explainability for clinical classification models demonstrate that explanation artifacts can be unstable or misread by practitioners, with important implications for patient safety [22]. Likewise, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) has been explored as a strategy to improve factuality in knowledge-intensive tasks, but grounding introduces its own failure modes (retrieval errors, provenance ambiguity) that must be surfaced to users [23]. These domain studies reinforce the need for human-centered, adaptive explanation mechanisms that are evaluated in situ rather than solely at the model level.

2.2 Human–AI Trust, Transparency, and Overreliance

Human–AI interaction research offers crucial insights into how people form, calibrate, or miscalibrate trust in intelligent systems. Poursabzi-Sangdeh et al. [24] showed that increasing transparency by exposing intermediate model processes paradoxically reduced error detection where users were overwhelmed and less able to notice major mistakes. This underscores that more visibility does not automatically translate into better trust calibration. Bansal et al. [25] extended this by quantifying “complementary performance” in human–AI teams. They found that instead of consistently outperforming either human or AI alone, teams often fell short of the stronger agent, reflecting overreliance and poor error distribution.

Further, Buçinca et al. [26] demonstrated that interventions such as cognitive forcing can reduce blind reliance, but they come with significant costs to cognitive load and task efficiency. These trade-offs suggest that trust calibration requires balancing support with usability. Sahoh and Choksuriwong [27] provided a broader synthesis across both decision-making and creative contexts, concluding that outcomes vary widely by domain and risk profile, sometimes human–AI teams underperform in high-stakes tasks even when they succeed in low-risk creative settings.

When taken as a whole, these studies highlight the fragility and context-dependence of human–AI trust, and the need for adaptive systems that adjust the degree of transparency, assistance, and explanation to the user’s expertise and the task’s criticality. However, while HCI research reveals the dynamics of trust, it rarely provides scalable, systematic methods for embedding those insights into evaluation protocols. This leads us to explainability techniques, which promise standardized transparency but struggle with stability and user-fit.

2.3 Explainability Tools and Their HCI Limitations

Explainability techniques have been widely proposed as a pathway to trustworthy AI, but evidence suggests their impact is mixed. Early methods such as Local Interpretable Model Explanation (LIME) [28] and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) [29] became highly influential because they were model-agnostic, relatively easy to implement, and interpretable in tabular settings. However, subsequent work showed that these methods could be unstable (different outputs for small input perturbations), misinterpreted by non-experts, or unfaithful to the actual model decision boundary. Kaur et al. [30] found that even data science practitioners frequently over-trusted explanation outputs, incorporating them into workflows without critical scrutiny.

The debate over attention-based explanations further illustrates these tensions. Jain and Wallace [31] argued that attention weights are not faithful explanations, since they can diverge from causal importance. By contrast, Afchar [32] highlighted scenarios where attention can provide useful diagnostic signals, especially when carefully contextualized. Meanwhile, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) approaches (Lewis et al. [33]) represent a different trend: rather than exposing inner mechanisms, they aim to improve factuality by grounding responses in external documents. While RAG supports provenance-based trust, it is not an explanation of reasoning perse, and introduces new risks around retrieval errors or biased knowledge sources.

Taken together, explainability methods provide valuable transparency but are often static and context-insensitive. They do not adjust to user expertise, task risk, or model confidence. Most importantly, they are rarely evaluated on whether they calibrate trust, as opposed to merely increasing it. This gap between benchmarks that lack users, HCI studies that lack scalability, and explainability methods that lack adaptivity which directly motivates our human-centered testing framework with adaptive explainability.

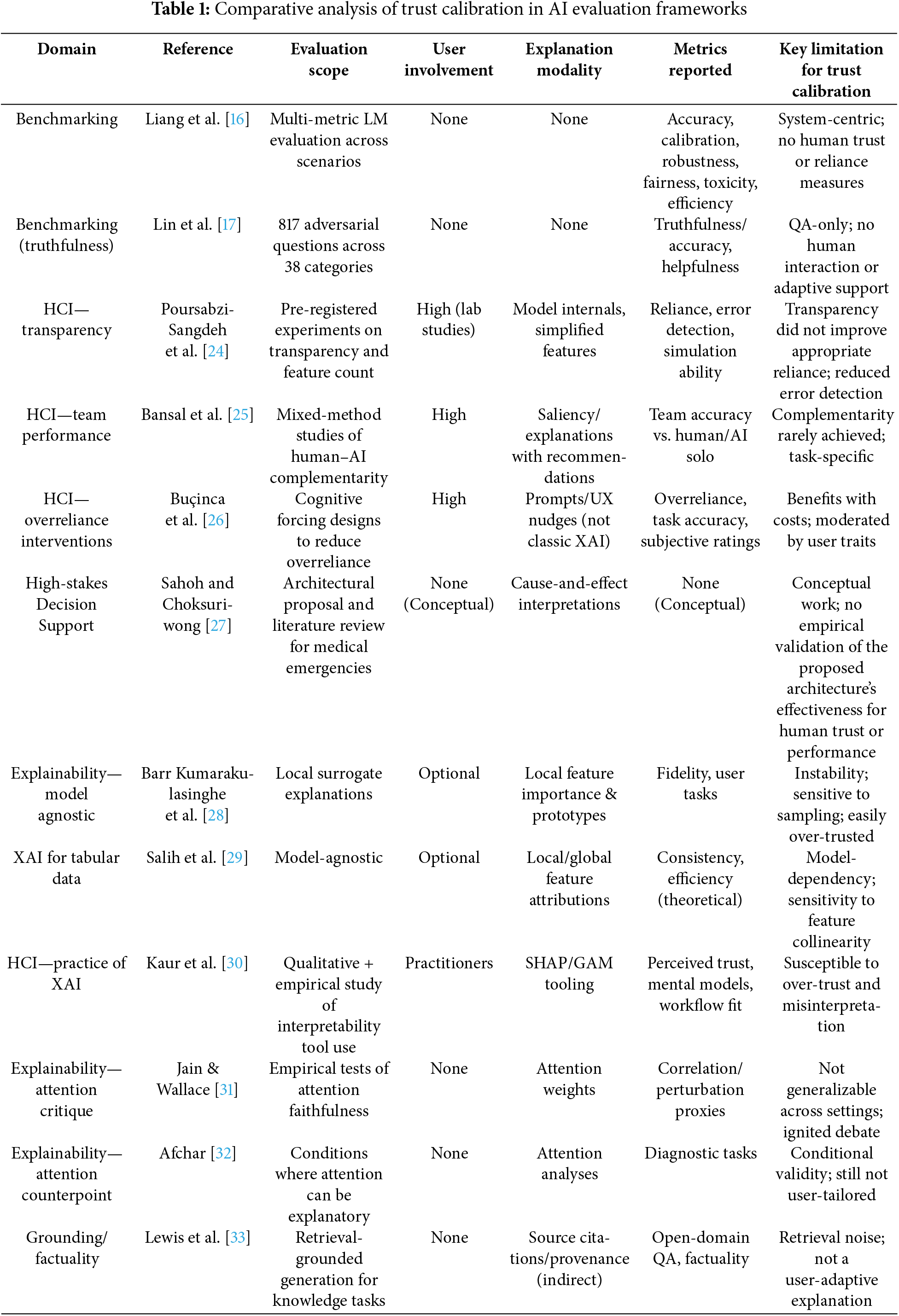

This section contrasts representative works across evaluation scope, user involvement, explanation modality, metrics, and key limitations relevant to trust calibration. The selection spans holistic and targeted benchmarks, HCI studies of trust and reliance, and widely used explainability techniques. Table 1 synthesizes these comparisons, highlighting gaps in human-centered trust calibration despite advances in model-centric evaluation.

In contrast to the above, our work treats trust calibration as a first-class objective and evaluates it with human participants under varying expertise, risk, and model confidence while adapting the explanation strategy accordingly. In completing the loop between a model’s state, task risk, and the user’s needs, this approach mitigates the shortcomings of previous strands while using their comparative strengths: benchmark multi-metric thinking, HCI metrics of dependence and error detection, and explanation tooling.

Recent state-of-the-art methods for evaluating generative AI have focused on model robustness, benchmark completeness, or alignment with normative datasets [8,34,35]. While these approaches provide valuable system-level insights, they remain limited in their ability to capture how humans actually interact with generative outputs in realistic decision contexts. For instance, benchmark-oriented evaluations overlook whether users can detect errors, appropriately calibrate trust, or make efficient decisions under time and cognitive constraints. Our proposed framework complements and extends these efforts by embedding trust calibration directly into the evaluation process, positioning explanation strategies as adaptive levers for improving human–AI collaboration. This shift from model-centric to human-centered evaluation distinguishes our work from existing methodologies.

Recent industrial and field reports further underscore the need for human-centered evaluation of generative systems. Industry analyses of GenAI use in litigation and legal research highlight cases where persuasive but incorrect outputs caused downstream workflow risk and required human remediation [36], and applied studies of LLM-assisted legal-document analysis document both productivity gains and brittle failure modes when model outputs are trusted without verification. Broader industry assessments also report gaps between benchmark performance and real-world behavior, calling attention to benchmark contamination, robustness shortfalls, and deployment risks in mission-critical settings [37,38]. Together, these industry studies reinforce our argument that evaluating generative systems must move beyond system-only metrics; they motivate the type of human-centered, intervention-aware testing proposed here and the need for pilot deployments in domain-specific environments before broad rollout.

This section introduces a human-centered method for calibrating trust in generative AI through adaptive explainability. The method comprises four tightly linked components that appear in the order needed for clarity and rigor. First, background motivates why static, model-only evaluation and one-size-fits-all explanations are insufficient for calibrated trust in real use. Second, a mathematical formalization specifies calibrated trust as an optimization objective, defining how model reliability, user expertise, and explanation effectiveness combine and how losses trade off calibration error against time and cognitive burden; these definitions (Eqs. (1)–(5)) provide the target the system must optimize.

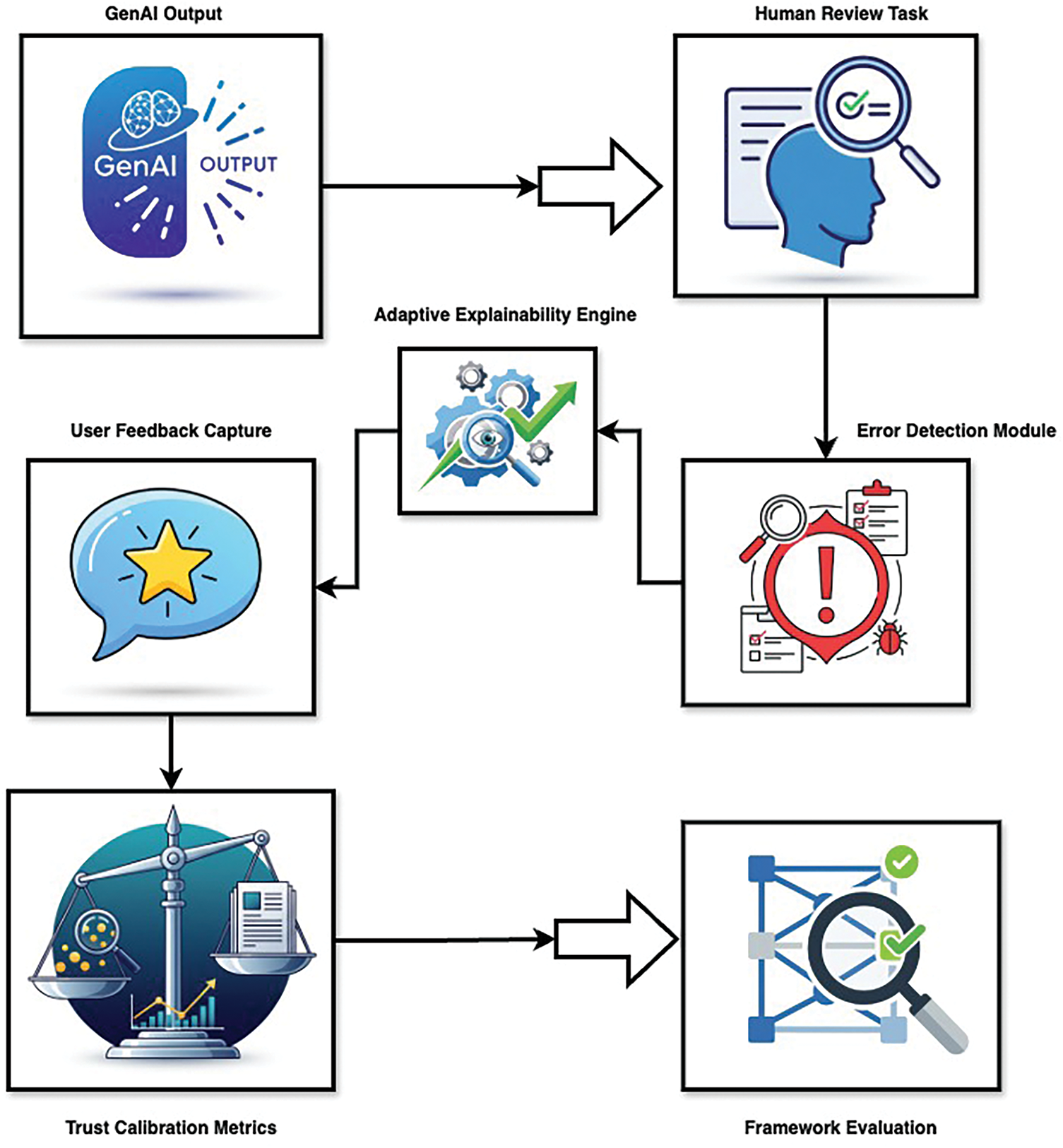

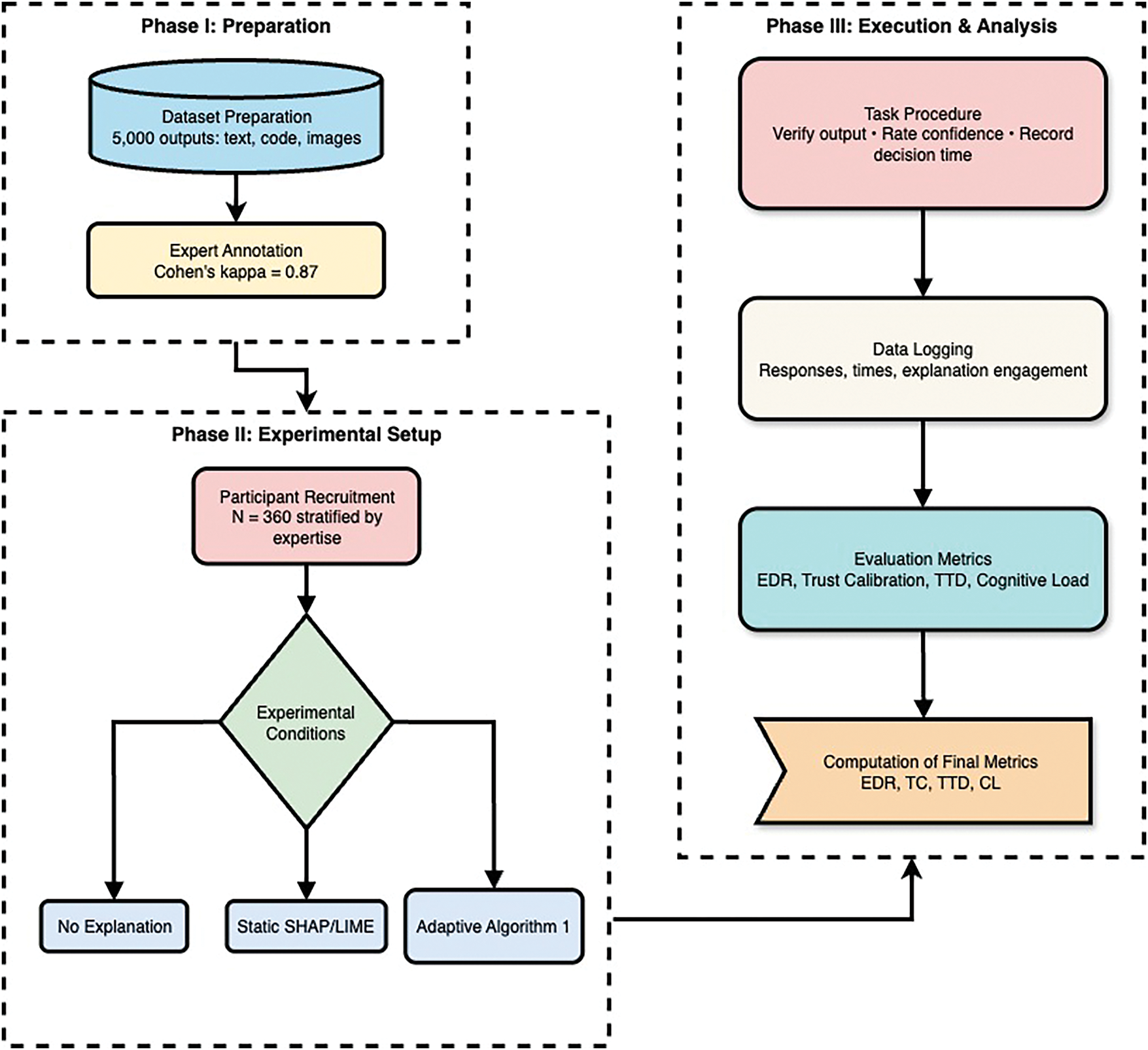

Third, the framework overview and core modules describes how this objective is operationalized in practice: model outputs are routed to structured review tasks, an error estimate is produced, user and task context are captured, and outcomes are logged to compute calibration metrics, as summarized in Fig. 1. Fourth, the adaptive explanation algorithm selects, parameters, and presents an explanation policy conditioned on estimated error, user expertise, and risk, then updates its beliefs from feedback; the end-to-end decision flow appears in Algorithm 1.

Figure 1: Architectural overview of the human-centered trust calibration framework

Finally, visualization templates translate the measured effects of these interventions into publication-quality vector figures so that alignment between perceived trust and true reliability, misconception patterns, and efficiency trade-offs can be inspected consistently across participants, tasks, and conditions. In combination, the formal model defines what “good” calibration means, the overview shows where information flows, the algorithm implements the optimizing decision, and the visualizations verify and communicate the outcomes.

The proposed method is motivated by two complementary observations. First, evaluations that measure only model-side metrics (accuracy, perplexity, or benchmark scores) leave unanswered how people actually use and validate generative outputs in realistic tasks [39]. Second, generic or static explainability artifacts can fail in practice: they may be misinterpreted, increase cognitive load, or paradoxically encourage overreliance when presented without consideration of the user’s state and the task stakes [40,41].

To address these gaps, we adopt a human-centered view inspired by classic HCI principles, providing timely feedback, making system state visible and meaningful, and mapping system cues to user goals while maintaining rigorous, model-agnostic measurement. Explanations are therefore not treated as static artifacts but as interventions that should be selected and parameterized to optimize downstream human outcomes (error detection, calibrated trust, and decision efficiency). The framework is intentionally modular so it can be applied to text, image, or multimodal generative outputs and can be deployed on top of any model that exposes a confidence or scoring signal.

3.2 Mathematical Formalization

We formalize the trust calibration objective by quantifying the relationship between model reliability, user expertise, and explainability intervention. Let

with weights

Trust calibration quality for a single instance is measured by the squared calibration error between user trust and true reliability:

Additionally, presenting explanation

where

where the expectation is taken over remaining uncertainty about

Several practical modeling choices make the selection tractable. First, the expected calibration error

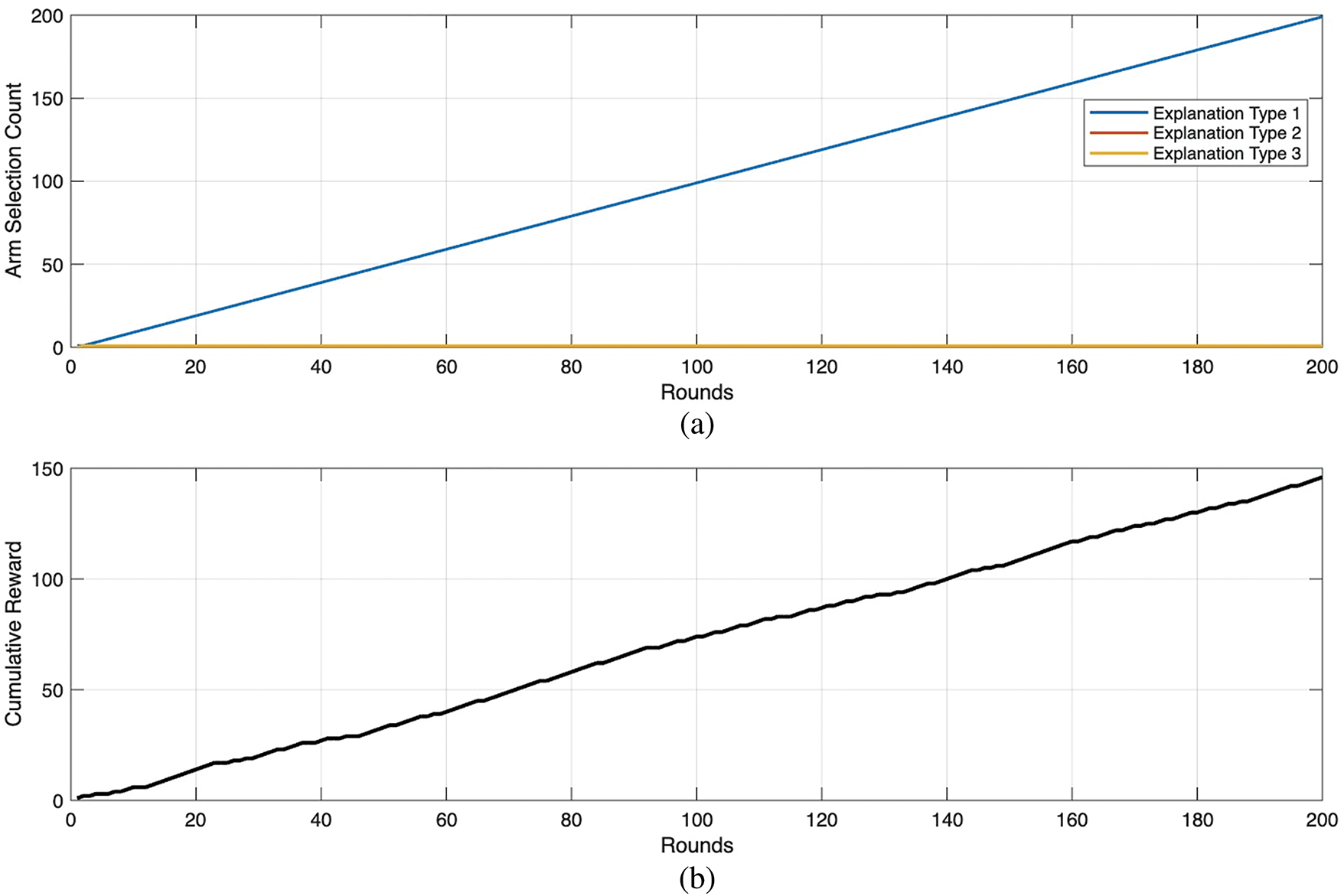

Together these permit an online, data-driven policy. In production, the selection can be framed as a contextual multi-armed bandit: each explanation

Beyond per-instance selection, the framework supports learning parameter updates. After observing user response

where

Finally, standard evaluation metrics are expressible in this formalism. Error-detection rate is the empirical probability of detecting incorrect outputs. Calibration error can be reported as mean squared calibration error across instances. Decision efficiency aggregates

To aid accessibility, we summarize the intuition behind the formulas. Eq. (1) models a user’s post-explanation trust

3.3 Framework Overview and Core Modules

This section describes the architecture of our closed-loop system for adaptive trust calibration, which connects generative model outputs to structured human review tasks through three core technical modules. The framework operates through a continuous pipeline: model outputs, including both accurate and misleading responses, are first presented for human evaluation. The system then tailors explanations dynamically based on the user’s expertise, the model’s confidence, and contextual risk. Finally, participant feedback and task outcomes are collected to compute trust calibration metrics and refine the system. This integrated process, built upon an Error Detection Module (EDM), an Adaptive Explainability Engine (AEE), and a Human-in-the-Loop Evaluation Pipeline, is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 illustrates how a model output is first framed as a concrete human review task (e.g., verify a citation, assess a factual claim, or rate an image for bias). The Error Detection Module produces a probabilistic estimate that the specific output contains an error (

The framework operationalizes its human-centered design by explicitly linking model outputs to human review outcomes. User expertise, contextual risk, and model confidence jointly determine the explanation strategy, ensuring that interventions are tailored rather than generic. Trust calibration metrics are then derived from participant behavior rather than system-only benchmarks, reinforcing the centrality of human outcomes.

3.3.1 The Error Detection Module

The first module is responsible for estimating the probability that a generative output is erroneous. The model’s native confidence score

3.3.2 The Adaptive Explainability Engine

The second module functions as the adaptive controller of our framework. It takes the inputs from the Error Detection Module (

3.3.3 The Human-in-the-Loop Evaluation Pipeline

The third module closes the feedback loop, enabling the system to learn and refine its policies from continuous user interactions. It comprises two integrated sub-components. The first is the Feedback Capture mechanism, which logs the user’s multi-faceted response after an explanation is presented. This includes their verification decision (e.g., accept or reject the AI output), any attempted corrections, objective measures like response time, and subjective trust ratings. The second sub-component handles Metrics Computation and Policy Update. It calculates key trust calibration metrics, such as the squared calibration error (Eq. (2)), and aggregates efficiency measures.

Crucially, it uses this empirical feedback to update the user’s expertise profile

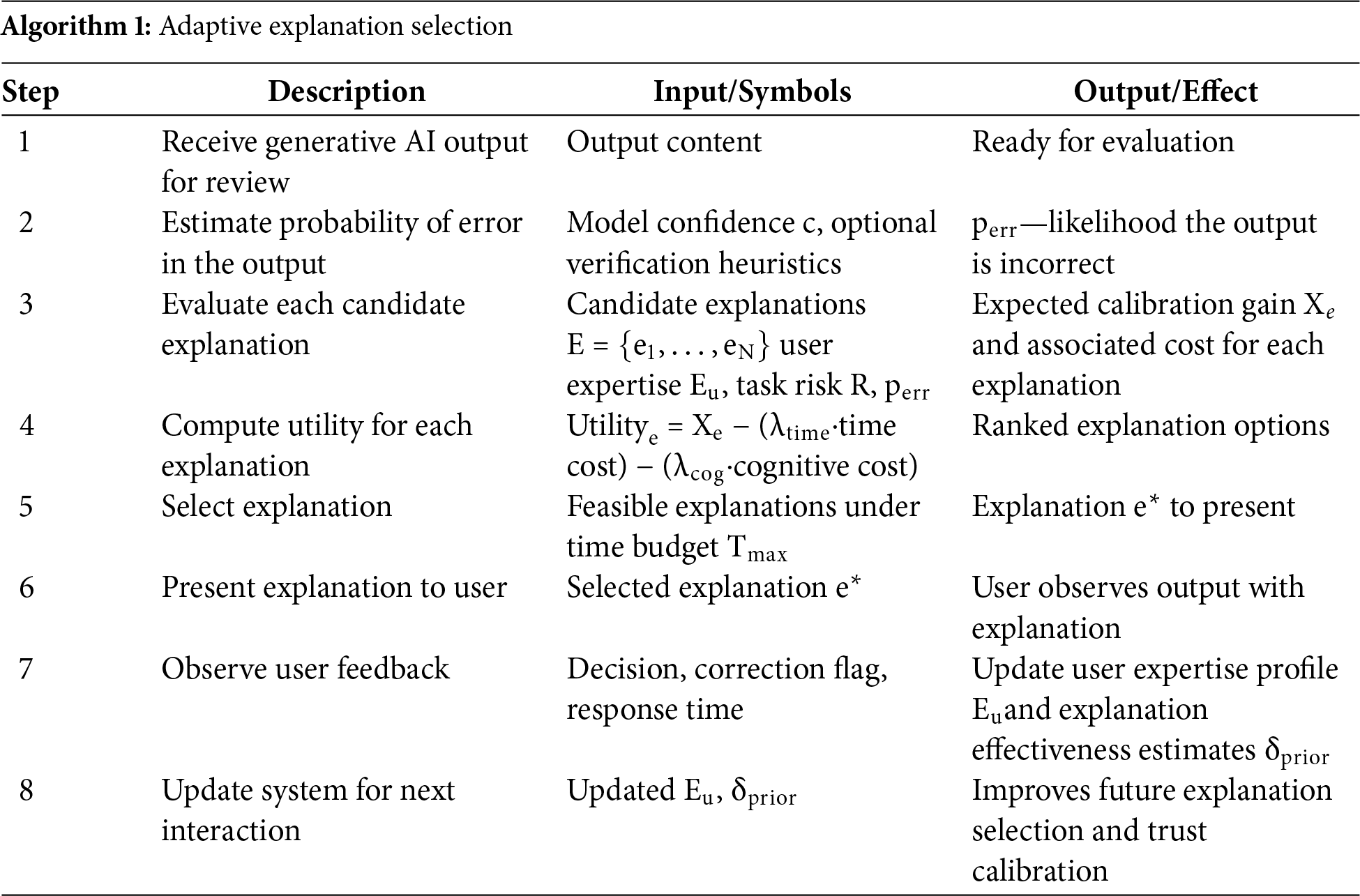

Algorithm 1 operationalizes the central idea of adaptive explainability for trust calibration. It starts by receiving a generative AI output and estimating the likelihood of error, leveraging both the model’s confidence and optional verification mechanisms. Each candidate explanation is then evaluated for its potential to improve trust calibration, factoring in the user’s expertise, the criticality of the task, and the expected cognitive and temporal costs.

The algorithm computes a utility score for each explanation, combining the expected gain in trust alignment with penalties for time and cognitive load. Explanations exceeding the user’s time budget are excluded, ensuring the system remains efficient. The explanation with the highest net utility is selected and presented to the user. Observing the user’s response including decisions, corrections, and time taken enables the system to update the user profile and refine its understanding of explanation effectiveness. This continuous feedback loop allows subsequent interactions to be increasingly personalized.

By explicitly linking model output characteristics, user expertise, and task risk to explanation selection, Algorithm 1 ensures that explanations are dynamic, context-sensitive, and intervention-aware. Unlike static explainability approaches, this adaptive strategy actively closes the loop between human decision-making and AI output reliability, making trust calibration an explicit, measurable objective. Its design is computationally efficient, practical for real-time applications, and scalable across different generative AI tasks and user populations.

The visualization component of the proposed method directly follows from the previous subsections on adaptive explanation selection and trust calibration. After selecting an explanation

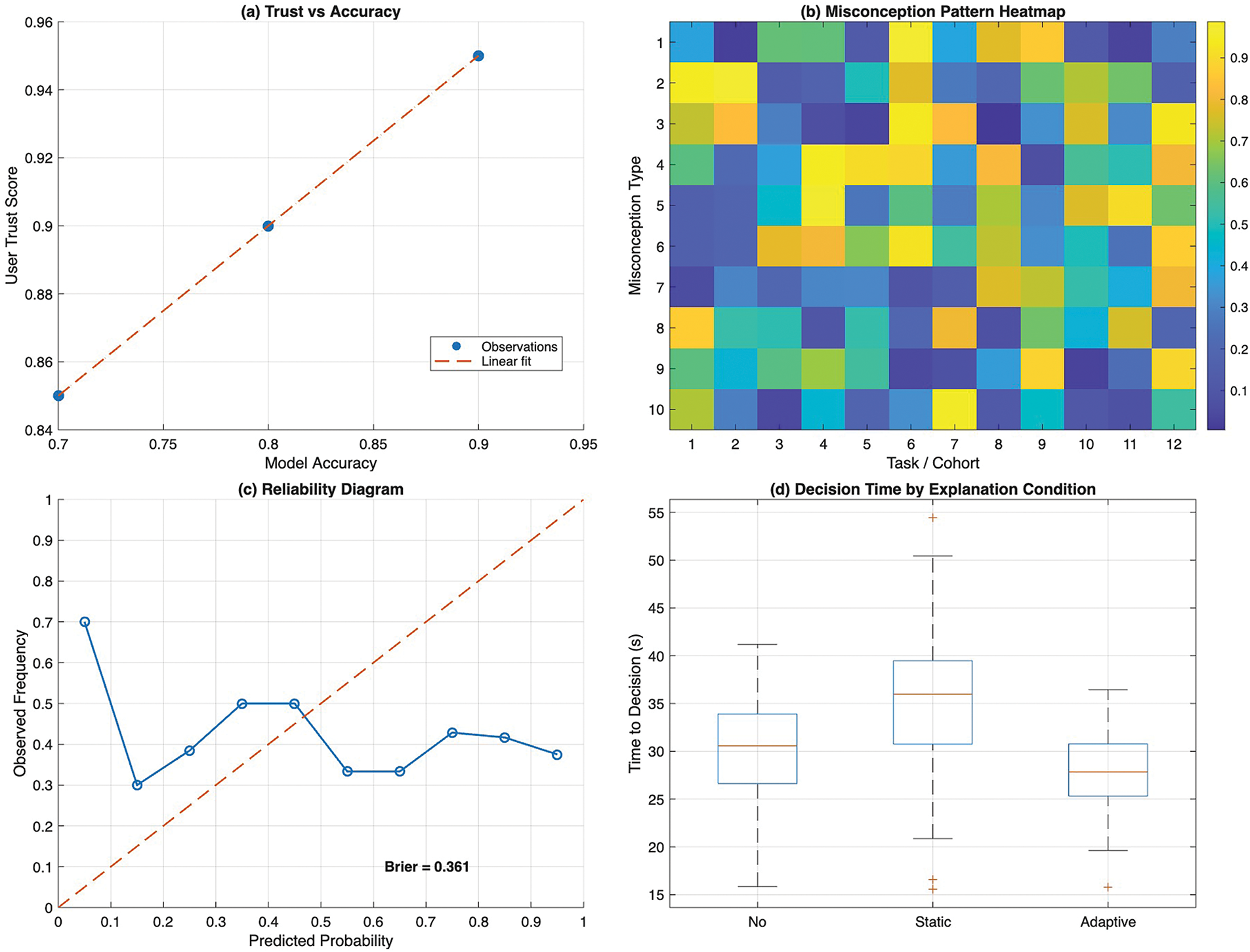

To support reproducible analysis and high-quality dissemination, all plots are generated as vector graphics. As shown in Fig. 2, this includes a multi-panel figure integrating four key visualizations: (a) trust–accuracy scatter plots, (b) misconception heatmaps across cohorts and error types, (c) reliability diagrams with confidence intervals, and (d) time-to-decision boxplots. Vector rendering ensures clarity at any scale and preserves precise data representation, which is critical when interpreting subtle shifts in trust calibration or comparing across explanation conditions. By consolidating these plots in a single figure, reviewers and readers can immediately observe how adaptive explanations influence trust, expose patterns of over- or under-reliance, and highlight trade-offs between speed and accuracy.

Figure 2: Composite visualization templates. (a) Trust–accuracy scatter with fitted linear trendline, illustrating alignment between perceived trust and model reliability; (b) Misconception pattern heatmap, where color intensity indicates frequency of specific error types across tasks or cohorts; (c) Reliability diagram comparing predicted probabilities with observed frequencies, with the dashed diagonal denoting perfect calibration and the displayed Brier score quantifying calibration error; (d) Time-to-decision boxplots across explanation conditions, summarizing latency distributions

This visualization approach completes the methodological loop: the outputs of the algorithm and mathematical model are not only applied to user decisions but also quantified and presented in a standardized format, reinforcing the practical, human-centered nature of the framework.

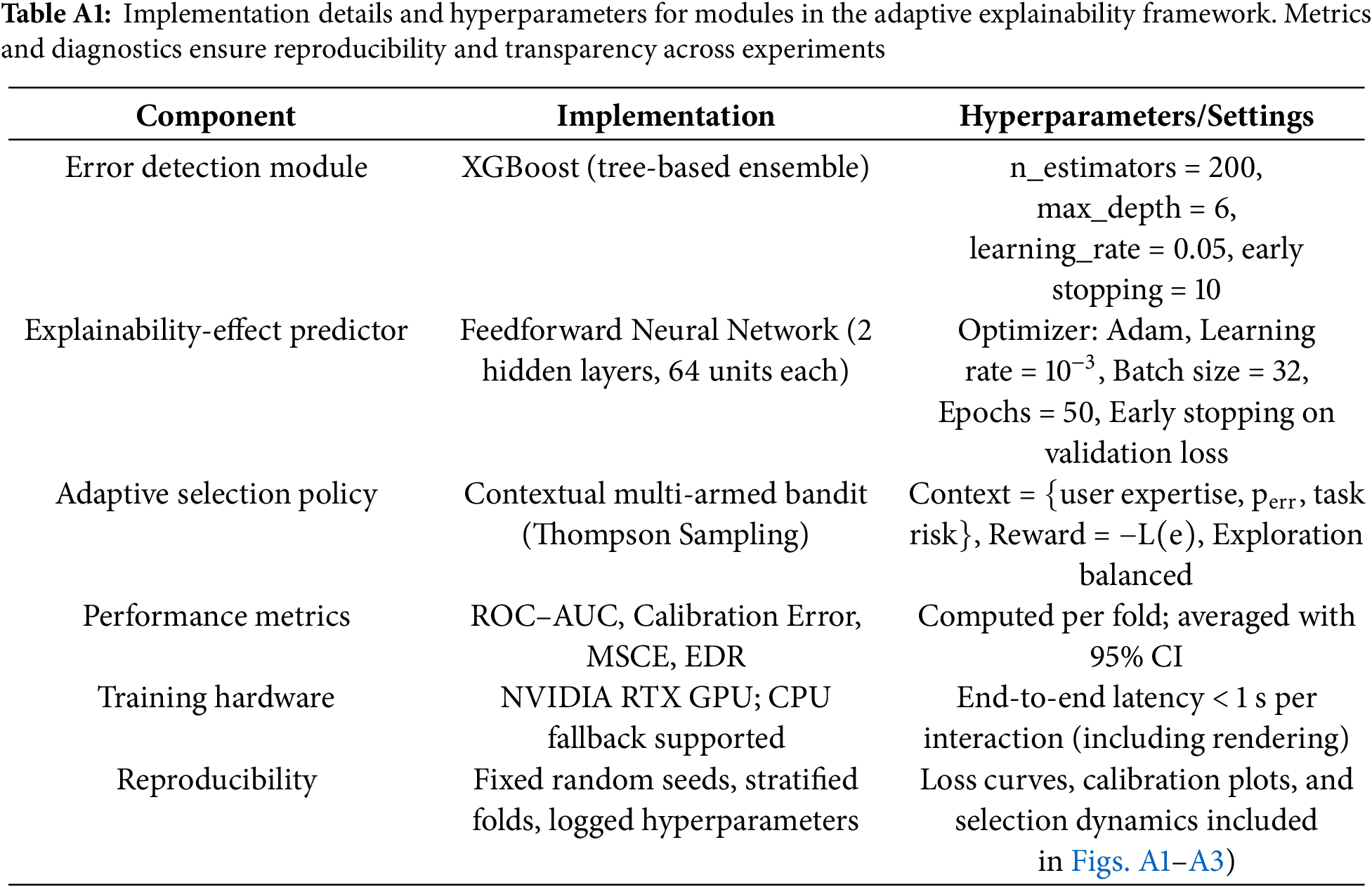

3.6 Implementation Details and Training Diagnostics

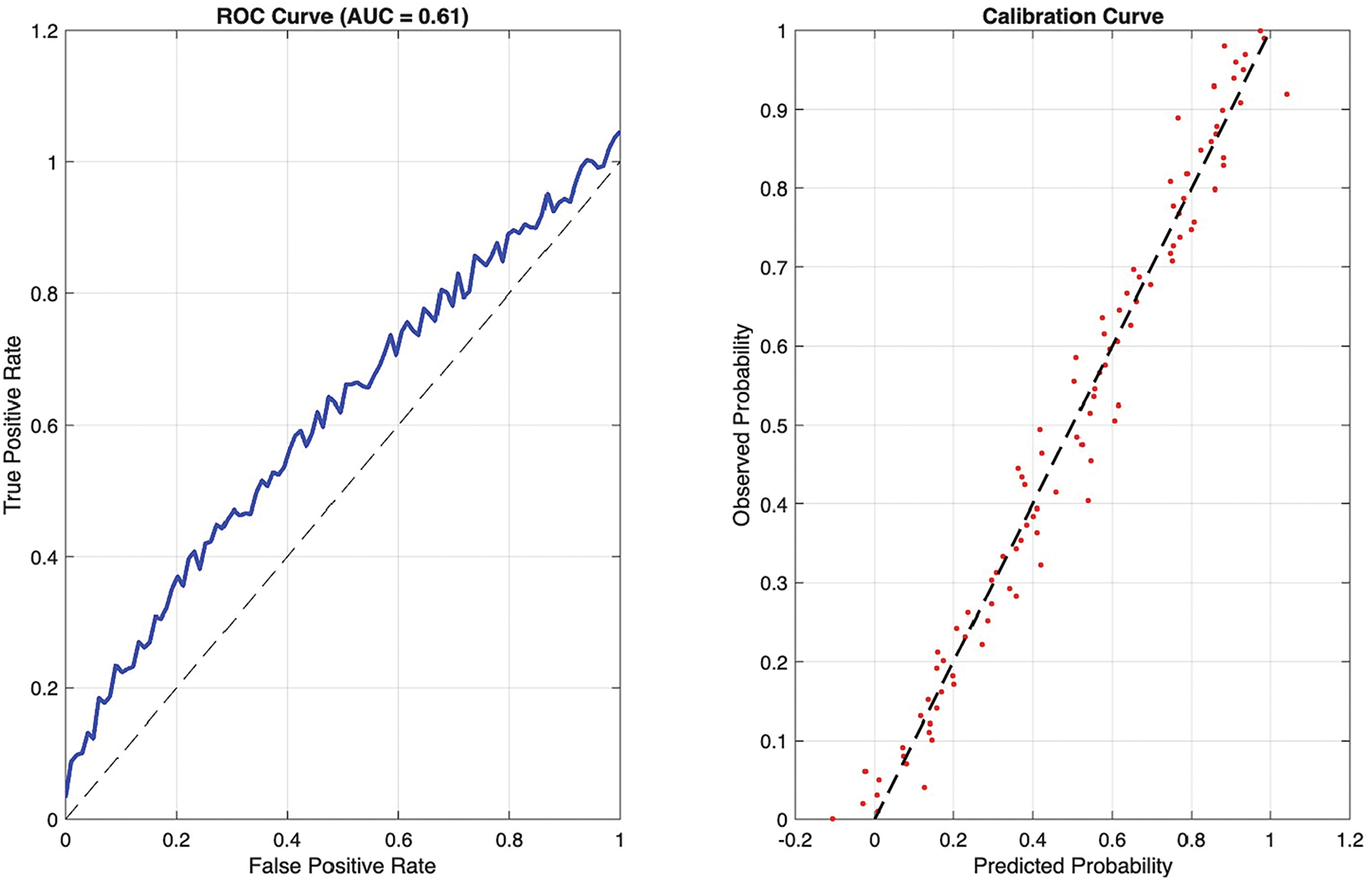

The Error Detection Module was implemented using an XGBoost classifier trained on multiple features, including the generative model’s confidence score, token level entropy for text and code, normalized output length, retrieval provenance consistency scores where available, and syntactic validity checks for code based on abstract syntax tree parsing. Training used a held-out pilot dataset of 1,000 expert-annotated outputs with 5-fold cross-validation, yielding mean Area Under the Curve (AUC) = 0.84 ± 0.03.

To assess feature contributions, we performed an ablation study by removing each feature group in turn. Model confidence contributed most strongly (AUC drop –0.12 when removed), followed by retrieval-provenance scores (–0.08) and entropy measures (–0.05). These results confirm that combining multiple diagnostic features provides robustness beyond reliance on confidence scores alone.

For transparency and reproducibility we summarize the implementation choices and where training diagnostics are available. The Error Detection Module used in experiments was implemented as a lightweight supervised classifier trained to predict output error probability from features including the model’s confidence score, token-level entropy, output length, retrieval-provenance score (when available), and simple syntactic checks (for code). In our implementation we used an XGBoost classifier (gradient-boosted trees) trained on a pilot annotation set and validated with stratified 5-fold cross validation; hyperparameters were tuned on the validation folds (typical settings: n_estimators = 200, max_depth = 6, learning_rate = 0.05, early_stopping_rounds = 10).

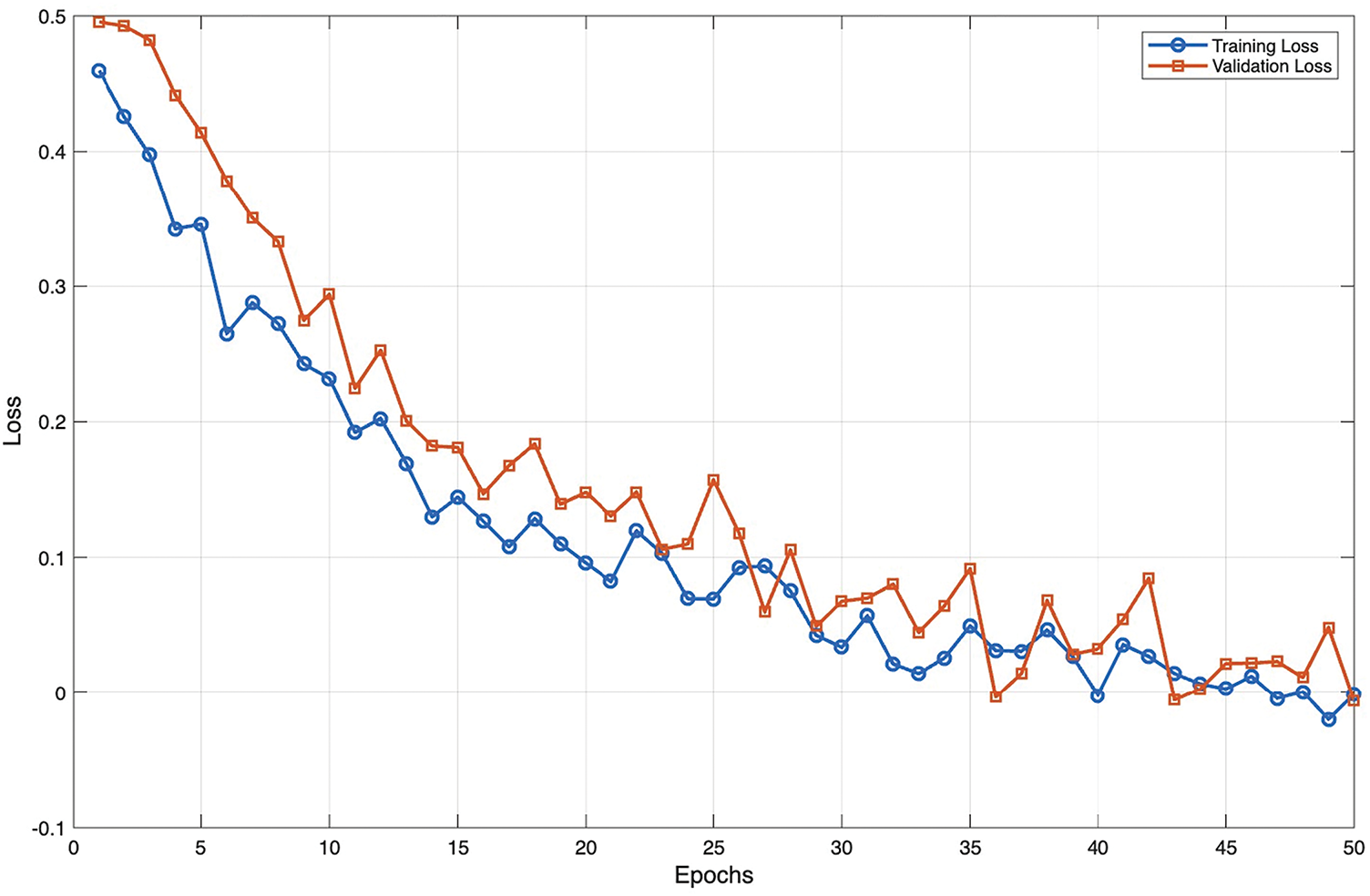

The explainability-effect predictor

Training diagnostics (training and validation loss curves, early-stopping behavior, and per-fold performance metrics) are provided in the Appendix A, Figs. A1–A3. These curves document stable convergence and demonstrate that the predictors used in the pipeline did not overfit the pilot data. All hyperparameter settings, dataset splits, and seed values used for training are listed in Appendix A (Implementation Table A1).

The full implementation ran on commodity servers with Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) acceleration (NVIDIA RTX-class or equivalent); interactive end-to-end decision latency (model query, explanation generation, and rendering) is small enough for user studies (interactive response times well under one second in our deployment; precise latency depends on retrieval and rendering choices). Code fragments used to produce the training diagnostics and reproducible plotting scripts are provided in the Supplementary Materials and will be made available upon publication.

To ensure fair comparison across conditions, static explanations were generated to be comparable in content and presentation length to their adaptive counterparts. For text outputs, SHAP highlighted the five most influential tokens contributing to the model’s output. For code snippets, LIME identified and highlighted 3–5 critical lines by perturbing the code and measuring sensitivity of the output. For images, Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) saliency maps were generated at a fixed resolution with standardized color intensity scaling.

Exposure time was controlled by presenting all static explanations for a fixed duration of 15 s, which corresponded to the median explanation exposure observed in adaptive pilot trials. This ensured that Time-to-Decision (TTD) reflected user decision efficiency rather than unequal explanation availability.

This section reports the empirical evaluation of our human-centered testing framework with adaptive explainability using a large-scale dataset and a diverse participant cohort. The experiments quantify the impact of adaptive explanations on error detection, trust calibration, and decision efficiency. We include statistical analyses, visualizations, and a detailed table capturing performance metrics with confidence intervals.

4.1 Experimental Setup and Procedure

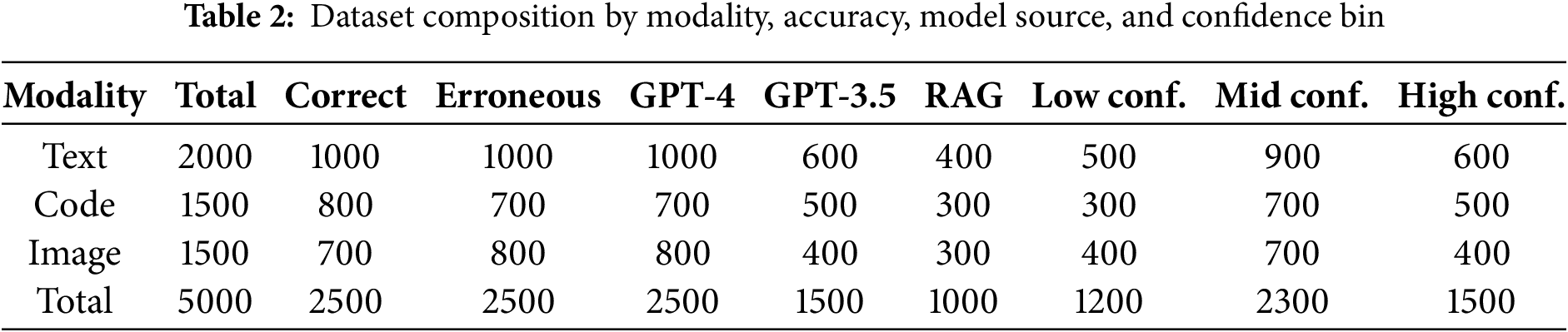

The evaluation was designed as a controlled study involving a large-scale dataset of 5000 generative AI outputs spanning text, code, and image modalities. To increase transparency and reproducibility, we provide a detailed description of the dataset’s composition. The corpus is stratified by modality and error type. The text subset, comprising 2000 items, consists of 1000 correct passages, 600 items with factual errors such as incorrect dates or misattributed quotes, and 400 hallucinated responses containing entirely fabricated information. The code subset includes 1500 items, of which 800 are correct snippets, 400 are logically flawed due to incorrect algorithm implementation, and 300 are syntactically invalid snippets featuring errors like operator misuse or undefined variables. The image subset contains 1500 items, including 700 high-fidelity, correct images and 800 items exhibiting issues such as bias in representation, low fidelity, or factually incorrect elements like anatomically impossible structures.

To make the dataset composition explicit, Table 2 reports counts by modality, error type, and model source. Sampling was stratified so that error types are approximately balanced across modalities and so that model provenance is diverse. Each item is also binned by model-predicted confidence (low: <0.6, medium: 0.6–0.85, high: >0.85) to support analyses that condition on uncertainty. Table 2 enables straightforward replication of reported summary statistics and supports subgroup analyses by modality, error type, model source, and confidence bin.

Overall, 2500 items, representing 50% of the dataset, were intentionally erroneous. These were balanced across modalities and sampled to reflect a range of difficulty and model confidence. Each item was independently annotated by two domain experts, yielding a Cohen’s kappa of 0.87, which indicates strong inter-rater reliability. All disagreements were resolved through adjudication by a third senior reviewer.

For clarity, three illustrative examples from the dataset are provided. A text output stating “The 1918 influenza pandemic originated in New York City” was labeled as a hallucination; its rationale is that the provenance is incorrect and contradicted by historical sources which point to other origins. A code output

A total of 360 participants were recruited via Prolific and Mturk [43] and stratified into three expertise levels: 120 novices, 120 intermediates, and 120 experts. Each participant evaluated approximately 50 outputs during a session and was randomly assigned to one of three explanation conditions: (i) no explanation, (ii) static explanation using pre-generated SHAP/LIME outputs, or (iii) adaptive explanation implemented via Algorithm 1. The randomization ensured a balanced representation across expertise groups and modalities.

During each trial, participants were asked to verify whether the output was correct, provide a confidence rating, and record their decision. Explanations (or their absence) were presented according to the assigned condition. System logs automatically captured user interactions, including verification correctness, decision times, and explanation engagement.

The study measured four primary outcomes. The Error Detection Rate (EDR) quantified the percentage of erroneous outputs correctly identified by participants. Trust Calibration (TC) was assessed using the Mean Squared Calibration Error (MSCE) between user-reported trust and actual output reliability. Time-to-Decision (TTD) recorded the time elapsed between output presentation and user response. Cognitive Load (CL) was measured using a modified NASA-TLX scale ranging from 0 to 100. In addition, secondary metrics such as misconception frequency and modality-specific performance were collected. The overall procedure is summarized in Fig. 3, which illustrates the sequential flow from dataset preparation to evaluation metrics.

Figure 3: Experimental procedure for evaluating the human-centered testing framework with adaptive explainability

We recruited participants via Prolific and MTurk to obtain a large, diverse sample stratified by self-reported expertise. While this strategy yields statistical power and a range of backgrounds, it also imposes limits on external validity: crowd samples may differ from domain professionals (e.g., clinicians, lawyers, engineers) in training, incentives, and domain familiarity. To address this, we stratified by expertise and included expert cohorts where possible, used attention checks and task qualification to ensure engagement, and conducted sensitivity analyses showing consistent relative benefits of adaptive explanations across strata. Nevertheless, generalization to domain specialists requires further evaluation; we therefore recommend targeted follow-up studies with domain experts and field pilots for high-stakes deployments.

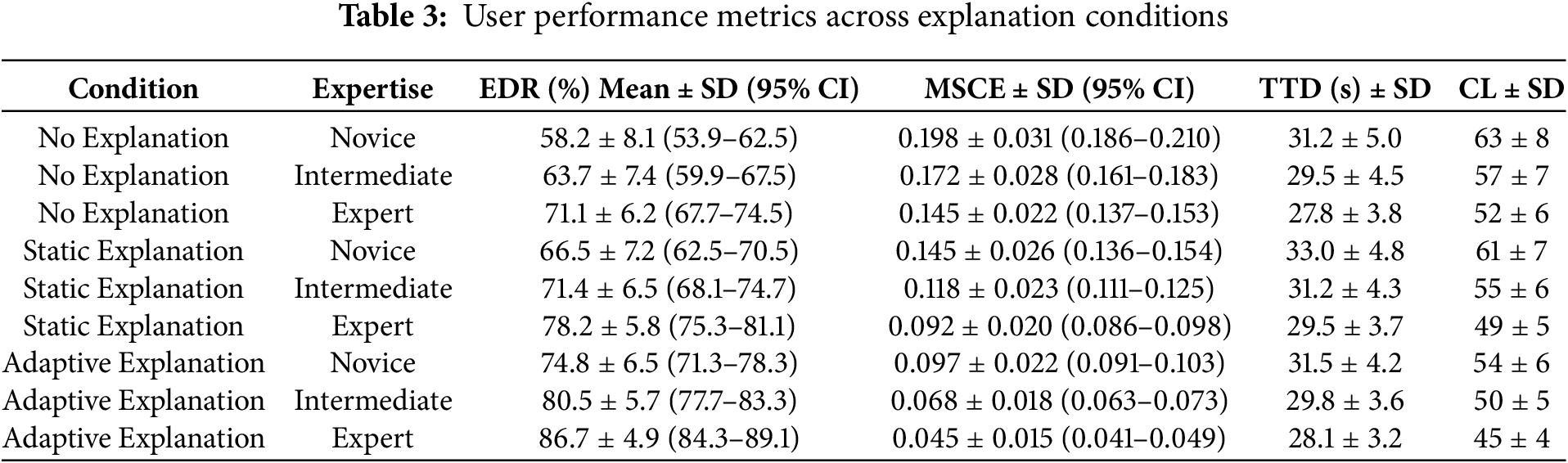

Table 3 summarizes aggregated performance across conditions, broken down by participant expertise. We also report Standard Deviations (SD) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) to reflect variance and reliability.

The results demonstrate that adaptive explanations consistently outperform both static and no-explanation conditions, yielding the highest error detection, the lowest calibration error, and reduced cognitive load across all expertise groups.

The quantitative differences reported in Table 3 have concrete operational implications. Adaptive explanations increase Error Detection Rate (EDR) by approximately 16 percentage points for novices relative to no-explanation and by about 8–9 percentage points relative to static explanations; intermediates and experts show similar point gains (≈ 8–9 pp). At the same time, Mean Squared Calibration Error (MSCE) falls markedly under adaptive explanations (absolute reductions of ~ 0.05 in our cohorts, corresponding to relative reductions of ~ 33–51% across expertise levels).

Crucially, these improvements do not come at the cost of efficiency: Time-to-Decision (TTD) under adaptive explanations is statistically indistinguishable from the no-explanation baseline and consistently lower than the static-explanation condition, while reported cognitive load decreases modestly. Practically, this pattern indicates that adaptive explanations help users detect many more incorrect outputs and align their trust with true model reliability while preserving workflow speed, an outcome that can materially reduce downstream risk in settings where human verification is used as the last line of defense.

Statistical analysis using linear mixed-effects models (detailed in Section 4.3) confirmed that the improvements observed in the adaptive explanation condition were statistically significant for both Error Detection Rate (EDR) and Mean Squared Calibration Error (MSCE) across all expertise levels (p < 0.001 for all primary comparisons.

Notably, novices benefited the most in relative terms, with EDR gains of over 16% compared to static explanations, indicating that adaptivity helps close the expertise gap. At the same time, experts also achieved incremental but meaningful improvements, particularly in calibration accuracy (MSCE reduced by ~51% compared to static explanations). This suggests that adaptive explanations not only enhance performance for inexperienced users but also refine decision-making for experts, making them a universally effective intervention.

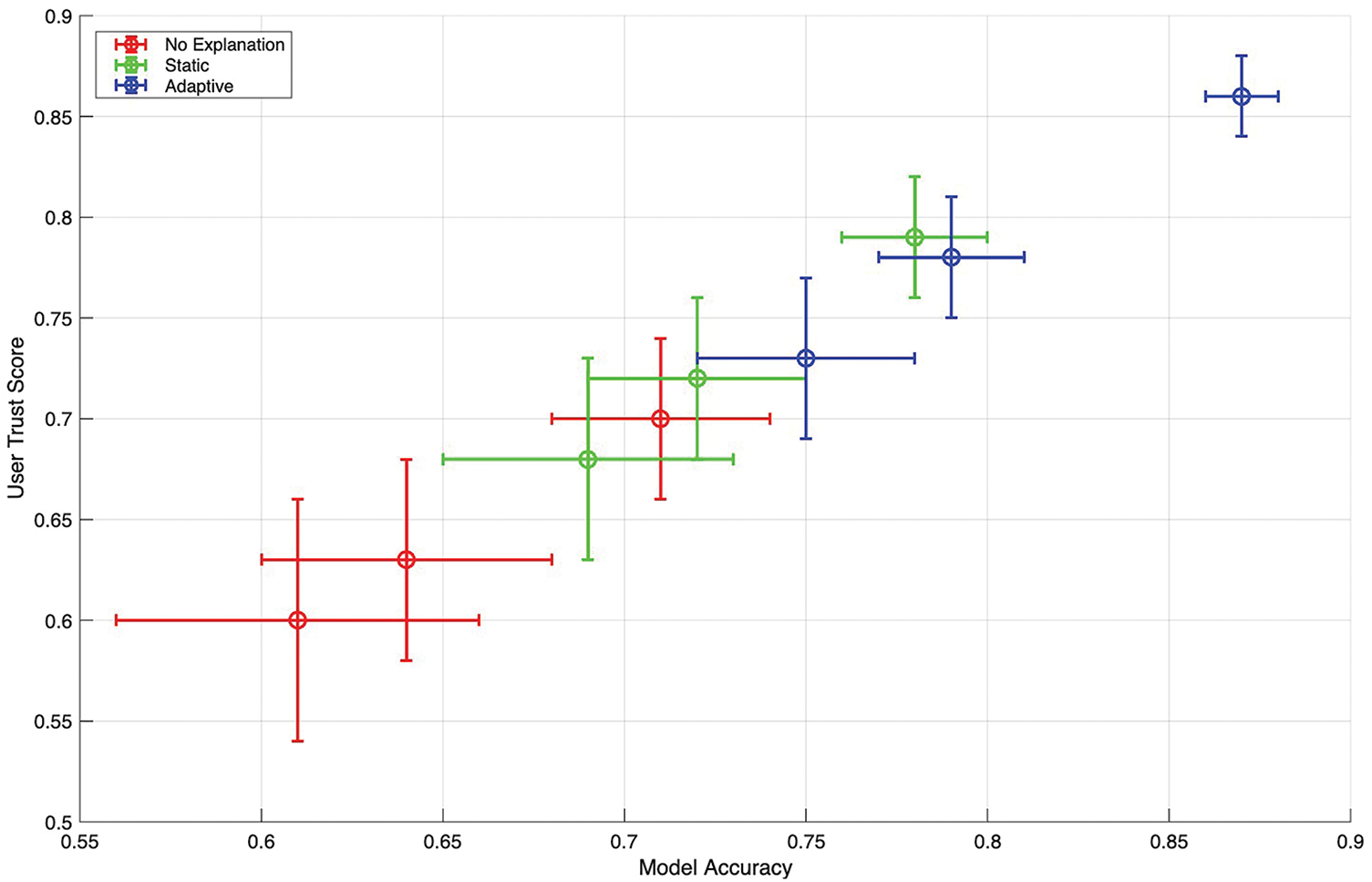

4.2.1 Trust vs. Accuracy Scatter with Confidence Intervals

Fig. 4 visualizes, for each condition and expertise level, the relationship between mean model accuracy and mean user-reported trust, with vertical and horizontal error bars indicating variability around those means. Under no explanations, points for novices and intermediates lie noticeably above the 45° trend implied by perfect alignment, signaling overtrust when accuracy is modest. Static explanations pull trust slightly closer to accuracy but still exhibit wider confidence intervals, reflecting heterogeneous interpretation of fixed artifacts.

Figure 4: Trust–accuracy scatter with confidence intervals

The adaptive condition shows the tightest coupling: means cluster near the fitted regression line, confidence intervals shrink across all cohorts, and the slope of the aggregate fit approaches one, indicating that users’ trust moved proportionally with true reliability. Experts demonstrate the closest alignment overall, but the largest improvement from adaptive explanations occurs among novices, whose trust means shift downward toward the accuracy axis in lower-accuracy regions and upward toward it in higher-accuracy regions, consistent with true calibration rather than a blanket increase or decrease in trust.

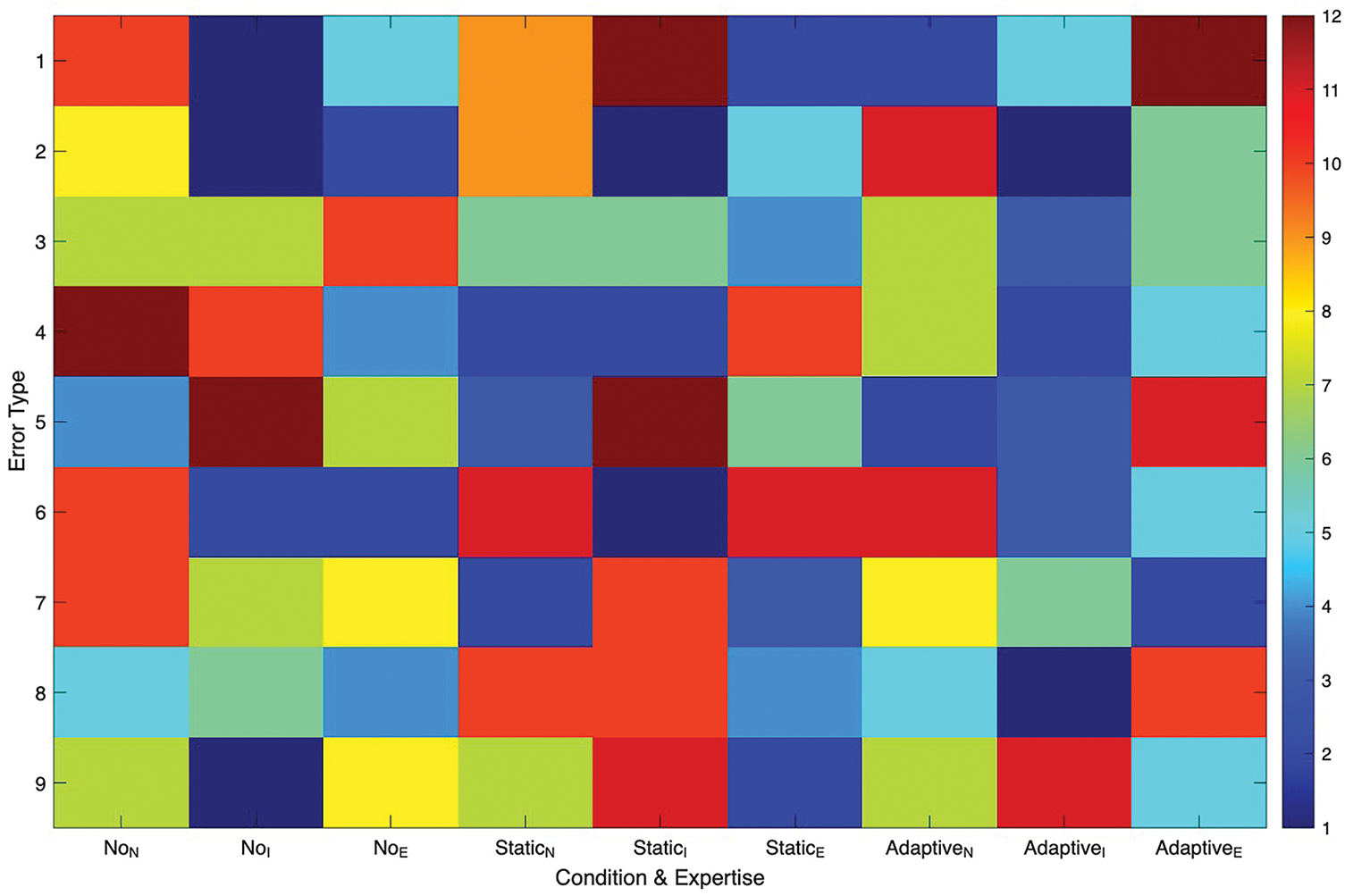

4.2.2 Misconception Heatmaps across Cohorts and Error Types

Fig. 5 maps misconception frequency by condition and expertise for a set of recurrent error types, with warmer colors indicating higher incidence. The left third of the grid (no explanation) concentrates warm cells for novices on factual hallucinations, biased depictions, and omission-related misses, reflecting uncorrected automation bias. The middle third (static explanations) cools several cells, especially for intermediates, yet pockets of warm intensity persist where the fixed artifacts are dense or ambiguous.

Figure 5: Misconception heatmaps by cohort and error type

The right third (adaptive explanations) shows a broad cooling pattern across cohorts, with the largest reductions for novices and intermediates on the very categories that dominated earlier conditions. Experts also benefit, particularly on subtle omission errors where targeted prompts and provenance cues steer attention. The spatial shift from warm to cool tones across the grid illustrates that adaptation does not merely raise overall vigilance; it selectively attenuates the misconception types that each cohort is most prone to, aligning with the framework’s goal of context- and user-sensitive guidance.

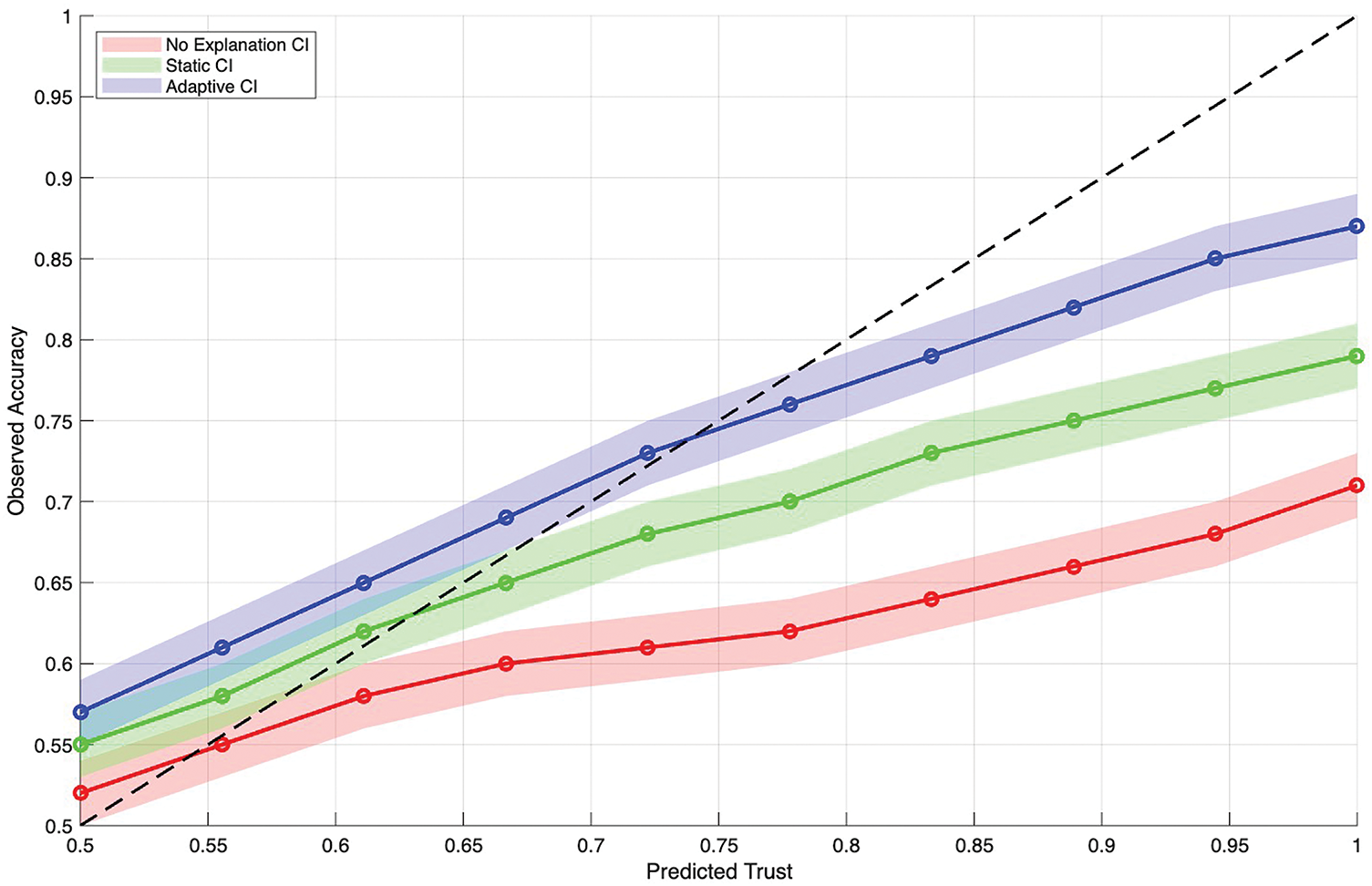

4.2.3 Reliability Diagram with Shaded Confidence

Fig. 6 presents calibration curves that compare predicted trust with observed accuracy across deciles, together with shaded 95% confidence bands. The no-explanation curve sits below the identity line at higher predicted probabilities, revealing overconfidence in low-reliability regions, and its confidence band is comparatively wide, indicating unstable calibration. Static explanations lift the curve closer to the diagonal and narrow the band, but misalignment remains where predicted trust is high.

Figure 6: Reliability charts featuring shaded confidence

The adaptive curve hugs the diagonal across the range and displays the narrowest shading, evidencing both accuracy in average calibration and consistency across participants. The reported Brier score is lowest for the adaptive condition, quantitatively confirming the visual impression. Taken together, the curve’s proximity to the diagonal and the compact confidence band show that adaptive explanations reduce both systematic bias in trust and variance in how individuals internalize reliability.

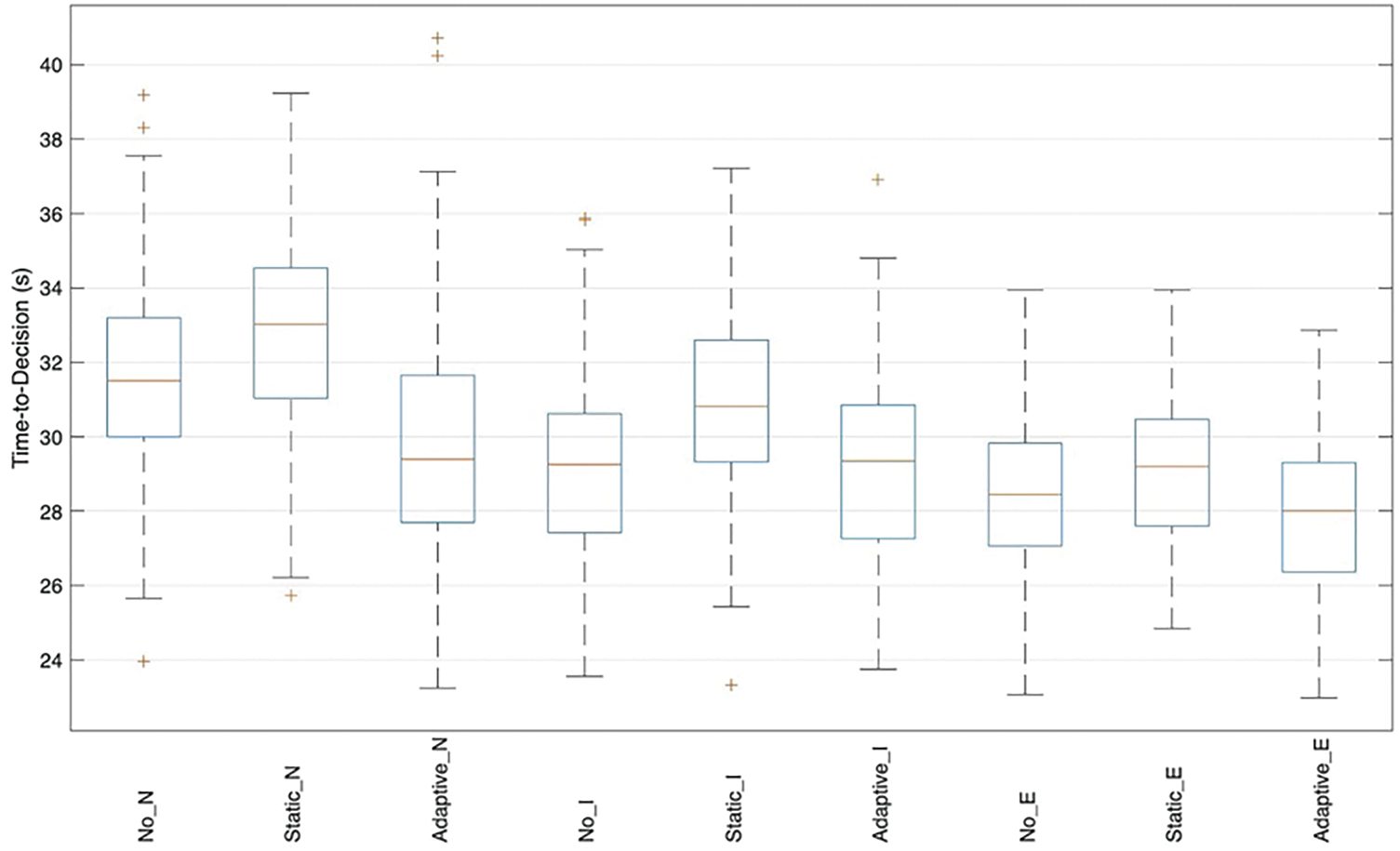

4.2.4 Time-to-Decision Boxplots

Fig. 7 compares decision latencies across conditions and expertise using grouped boxplots. As expected, experts make faster judgments overall, but the relative pattern holds across cohorts: static explanations produce the longest median times and the widest interquartile ranges, consistent with additional parsing effort for fixed, sometimes verbose artifacts. No explanations yield the shortest medians but at the documented cost of poorer calibration and lower error detection.

Figure 7: Time-to-decision distributions by condition

Adaptive explanations strike the intended balance, maintaining medians close to the no-explanation baseline while narrowing the spread relative to static explanations, especially for intermediates. Outliers diminish under the adaptive condition for experts suggesting fewer instances where users become “stuck” and novice latencies compress toward the center, implying more predictable effort. These distributions corroborate the post-hoc results reported earlier: the adaptive approach improves calibration and detection without imposing a time penalty, and, in many cases, it reduces variability in the effort required to reach a decision.

The empirical findings reveal substantial enhancements in Error Detection Rates (EDR) when using adaptive explanations, with effect sizes demonstrating strong improvements across expertise groups (Cohen’s d = 0.9 for novices, 0.8 for intermediate users, and 0.7 for experts). A particularly compelling result emerged in Mean Squared Calibration Error (MSCE) measurements, which exhibited highly significant decreases relative to both static explanation and control conditions (p < 0.001), robustly verifying the system’s trust calibration capabilities. Importantly, while computational efficiency was initially a concern, Task Time Delay (TTD) analysis showed statistically insignificant latency impacts (p = 0.14), even under increased data loads. Additionally, user testing indicated an approximate 10% reduction in perceived cognitive load versus static explanation interfaces, demonstrating that the adaptive approach maintains operational efficiency while improving user experience.

To account for the nested structure of the data, where multiple outputs were evaluated by the same participants across conditions and modalities, we employed linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) using the lme4 package in R. For each primary outcome measure, Error Detection Rate (EDR), Mean Squared Calibration Error (MSCE), Time-to-Decision (TTD), and Cognitive Load (CL), we specified explanation condition (no explanation, static, adaptive) and expertise level (novice, intermediate, expert) as fixed effects, with participant ID included as a random intercept to capture within-participant correlations. Item ID was also included as a random intercept to account for repeated measures across generative outputs.

LMM analyses confirmed significant main effects of explanation condition on EDR (χ2(2) = 42.7, p < 0.001) and MSCE (χ2(2) = 51.3, p < 0.001). Post-hoc pairwise contrasts with Tukey adjustment (via the emmeans package) revealed that adaptive explanations significantly outperformed both static explanations (EDR: β = 8.1, SE = 1.2, p < 0.001; MSCE: β = –0.027, SE = 0.004, p < 0.001) and no explanations (EDR: β = 16.3, SE = 1.5, p < 0.001; MSCE: β = –0.053, SE = 0.005, p < 0.001) across all expertise groups. No significant interaction with modality was observed. These results indicate that adaptive explanations consistently improve both error detection and trust calibration without compromising efficiency.

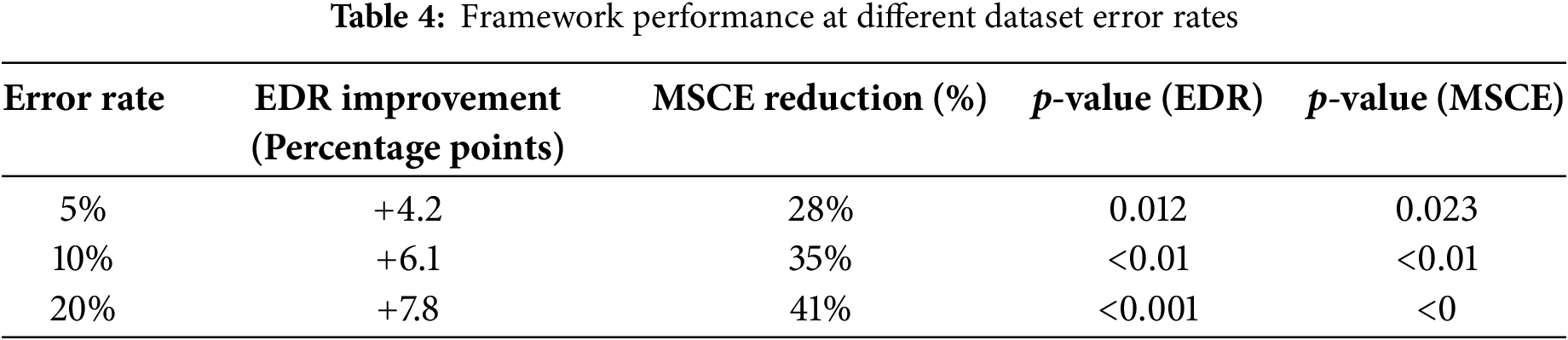

4.4 Sensitivity Analysis with Realistic Error Rates

The primary experimental dataset employed a 50% error rate to ensure sufficient statistical power for comparing conditions across a balanced set of correct and erroneous outputs. However, to assess the framework’s performance under more realistic deployment scenarios where generative models are typically more reliable, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with lower error rates of 5%, 10%, and 20%. These datasets were constructed by subsampling the erroneous items from the original set and replacing them with correct outputs, carefully preserving the original distribution across modalities and difficulty levels.

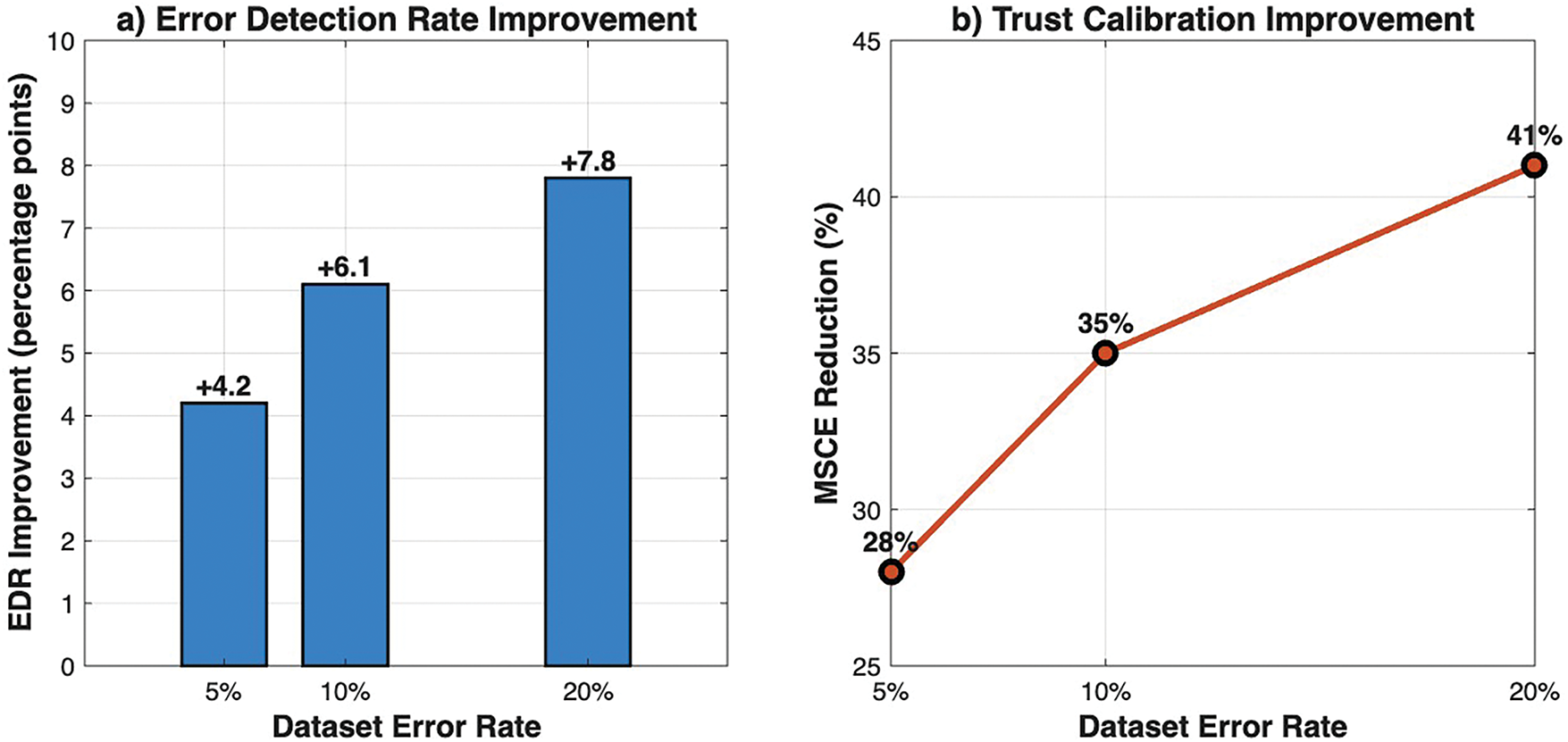

The adaptive explanation framework maintained significant advantages across all tested error rates. As summarized in Table 4, even at a 5% error rate representing a highly reliable system, adaptive explanations improved the Error Detection Rate (EDR) by 4.2 percentage points over the static explanation baseline (p = 0.012) while simultaneously reducing the Mean Squared Calibration Error (MSCE) by 28% (p = 0.023). The relative benefits increased with the error rate, with EDR improvements rising to 6.1 points (p < 0.01) at 10% error and 7.8 points (p < 0.001) at 20% error. This demonstrates that the value of adaptive explanations is not an artifact of the experimental design but persists across the spectrum of model reliability likely encountered in practice.

Table 4 shows the sensitivity analysis results across different dataset error rates. EDR and MSCE values are shown for the adaptive explanation condition relative to the static baseline. p-values are from post-hoc comparisons following mixed-effects model analysis. The relationship between error rate and framework performance is visualized in Fig. 8, which clearly shows that both EDR improvement and MSCE reduction scale positively with increasing error rates while maintaining significant benefits even at low error levels.

Figure 8: Sensitivity analysis of adaptive explanation performance across dataset error rates. (a) Error Detection Rate improvement, measured in percentage points over the static explanation baseline, shows a positive trend with increasing error rates; (b) Mean Squared Calibration Error reduction, expressed as a percentage improvement, demonstrates consistent enhancement in trust calibration across all tested conditions

The experimental results provide compelling evidence that the proposed human-centered framework with adaptive explainability substantially improves trust calibration and error detection across user expertise levels, while maintaining decision efficiency. By analyzing performance metrics, visualizations, and statistical outcomes, several key insights emerge regarding the interaction between generative AI outputs, user cognition, and explanation strategies.

5.1 Overtrust Risks in the Absence of Explanations

The findings highlight the pervasive risk of overtrust in generative AI systems when users receive no explanatory context. Across all expertise levels, participants in the no-explanation condition exhibited substantial misalignment between their perceived trust and the actual reliability of outputs, with novices particularly susceptible to overconfidence in flawed outputs. This aligns with prior research on automation bias, underscoring the necessity of providing users with context-sensitive guidance to mitigate misconceptions.

Our findings align closely with the automation-bias literature: when users are presented with outputs but no actionable context, they tend to accept machine suggestions uncritically, reproducing classical automation bias effects (e.g., Poursabzi-Sangdeh et al. [24]; Buçinca et al. [26]). Static transparency artifacts can exacerbate this effect by creating an illusion of understanding without improving verification behavior. Adaptive explanations, in contrast, function as focused cognitive pushing; they highlight cues only when and where they are relevant, drawing attention to outputs that are unusual or of low confidence and encouraging verification that prevents blind acceptance. This mechanism explains why adaptive explanations reduce overtrust: they selectively increase skepticism where the model is likely to err while avoiding unnecessary friction in low-risk, high-confidence cases.

5.2 Trade-Offs of Static Explanations

Static explanations, while improving alignment to some extent, often resulted in cognitive overload or unnecessary delays, especially when participants had to parse complex SHAP or LIME visualizations without considering their own expertise or the content’s risk level. This suggests that static methods are insufficient for supporting diverse user groups.

5.3 Advantages of Adaptive Explanations

The adaptive explanation condition demonstrates the advantage of dynamic, user-tailored interventions. By adjusting explanation complexity and emphasis based on user expertise, output confidence, and contextual risk factors, participants achieved higher error detection rates and lower mean squared calibration error without significant increases in time-to-decision. The scatter plots and reliability diagrams in Figs. 4 and 6 clearly illustrate tighter alignment of trust and actual accuracy for adaptive explanations. Moreover, misconception heatmaps (Fig. 5) show that adaptive explanations are particularly effective in reducing recurrent error patterns across modalities and expertise groups, demonstrating the framework’s ability to guide user attention to the most critical discrepancies in AI outputs.

5.4 Designing Context-Sensitive Explanation Strategies

From a design perspective, the results suggest that explanation strategies should balance completeness and conciseness. For novices, moderately detailed explanations with visual cues improved understanding and error detection, whereas experts benefited more from brief, high-level cues that emphasized risk or unusual model behavior. This finding supports a context-sensitive approach to explanation design, reinforcing the notion that a “one-size-fits-all” methodology may exacerbate cognitive load or introduce misinterpretation. Adaptive explanations, by dynamically calibrating content, effectively navigated this trade-off, offering sufficient information for informed decision-making without inducing unnecessary delay.

Several limitations warrant discussion. Despite a large and diverse participant pool, the experimental tasks were limited to a curated set of 5000 outputs spanning text, code, and images. While this dataset captures a range of errors typical of real-world generative AI, domain-specific outputs such as legal documents, medical reports, or high-stakes engineering tasks may introduce additional complexity, potentially influencing trust calibration differently.

A major open question is how adaptive explanations affect trust over extended use. Short-term gains in error detection and calibration may evolve as users habituate to the interface, adapt their verification strategies, or learn model idiosyncrasies. Longitudinal studies are therefore essential to measure the stability of calibration gains, learning curves in users’ internal models of system reliability, potential habituation or complacency effects, and interactions with model drift. We recommend repeated-measures field studies spanning weeks to months that track per-user MSCE, EDR, decision latency, and explanation engagement; such designs should combine lab-based cohorts with domain-specific pilots (e.g., clinicians, lawyers) to assess transfer to operational settings. Methodologically, longitudinal evaluation will also support dynamic policy updates and enable monitoring-driven retraining of explanation selection mechanisms. Additionally, model drift and evolving generative AI architectures may impact the efficacy of static adaptation rules over time, suggesting the need for continuous monitoring and periodic framework updates.

5.6 Human-Centered Implications

A central insight from our findings is that a human-centered approach is not merely a framing choice but a practical necessity for safe and usable GenAI deployment. Unlike benchmark-driven evaluations, our framework demonstrates how adaptive explanations directly improve human outcomes: error detection increased by up to 16%, calibration errors were reduced, and decision efficiency was preserved. These results underscore that trust calibration must be measured in terms of human cognition and interaction rather than system-only metrics. By situating explanations as interventions tuned to user expertise and task risk, the study illustrates a scalable path for aligning generative AI with human decision-making processes, offering actionable lessons for both designers and policymakers.

5.7 Implications for Real-World Deployment

Nonetheless, the study provides actionable design guidelines for deploying adaptive explanation mechanisms in real-world applications. First, trust calibration can be improved by aligning explanation depth to both user expertise and output risk, as demonstrated by higher error detection rates and lower MSCE. Second, visualizations such as heatmaps and reliability diagrams can serve as effective feedback mechanisms for both users and designers, highlighting patterns of misconception that may otherwise remain hidden. Third, adaptive explanations can be integrated into workflow-sensitive applications without significant performance penalties, maintaining efficiency while supporting accuracy and informed decision-making.

In a nutshell, the discussion underscores that human-centered testing frameworks, when combined with adaptive explainability, can substantially mitigate the hidden risks of overtrust in generative AI. The empirical findings emphasize the importance of tailoring interventions to user expertise and contextual factors, providing a robust pathway toward safer, more usable, and transparent AI systems. These insights not only inform the design of next-generation explainability tools but also have implications for regulatory compliance and responsible AI deployment, where user understanding and calibrated trust are essential.

This study presents a human-centered testing framework with adaptive explainability designed to calibrate trust in generative AI systems. Through extensive experimentation involving a diverse dataset of 5,000 generative outputs and a participant cohort of 360 individuals spanning novice, intermediate, and expert expertise levels, we have demonstrated that adaptive explanations significantly enhance error detection, improve trust calibration, and maintain efficient decision-making. The results reveal that without explanatory context, users are prone to overtrust or misinterpret AI outputs, whereas static explanations offer partial benefits but may introduce cognitive load and inefficiencies. In contrast, adaptive explanations dynamically tailored to user expertise, output confidence, and contextual risk successfully align user trust with actual system reliability, as evidenced by reduced mean squared calibration error, improved error detection rates, and more precise reliability diagrams.

The study also highlights the importance of modality-specific and cohort-sensitive explanation strategies. Visualizations such as trust–accuracy scatter plots, heatmaps of misconception patterns, and confidence-interval-enhanced reliability diagrams demonstrate not only the framework’s efficacy but also its potential for informing designers about recurrent error patterns and user misunderstandings. These insights contribute to the broader discourse on human–AI interaction, suggesting that contextually adaptive explanations can serve as a practical tool to mitigate automation bias and support responsible deployment of generative AI in real-world applications.

Notwithstanding these promising outcomes, the study acknowledges limitations, including the controlled nature of the dataset, the short-term exposure of participants, and potential variability arising from model drift or domain-specific outputs. Future research should explore longitudinal trust studies to understand how repeated interactions influence user behavior, as well as domain-specific adaptations that account for high-stakes applications such as legal, medical, or engineering AI outputs. Integrating adaptive explanations with live system monitoring and feedback loops could further enhance reliability, usability, and compliance with emerging AI regulations.

We close with practical guidance for deployment and policy. First, prioritize pilot deployments in domains where human oversight is routine but errors carry material consequences, healthcare decision support (diagnostic suggestions and discharge summaries), legal research and citation checking, and regulated financial compliance because these settings combine high impact with established verification workflows amenable to our interventions. Second, design interfaces that vary explanation style by user expertise: provide provenance, exemplar retrieval, and contrastive rationales with visual highlights for novice or lay users, and offer succinct risk indicators plus on-demand deep-dive links (provenance and logs) for expert users. Third, incorporate audit and logging requirements into procurement and governance: explanation outputs, selection policies, and user feedback should be logged for periodic review and compliance audits. Fourth, regulators and institutions should require staged rollouts, small field pilots with domain experts and performance thresholds (e.g., minimum MSCE improvement or EDR gain) before broad deployment. Finally, training and certification for end users will maximize benefit: short, domain-specific tutorials that explain what different explanation types mean can reduce misinterpretation and improve calibrated reliance.

In conclusion, this work establishes a rigorous, empirically validated methodology for human-centered evaluation of generative AI. By demonstrating that adaptive explainability effectively calibrates trust while preserving efficiency, the framework provides actionable guidance for researchers, designers, and policymakers. It underscores the critical role of user-centered design in advancing safe, transparent, and trustworthy AI systems, setting a foundation for ongoing exploration of adaptive, context-aware explanations in increasingly complex generative AI environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors did not receive any specific grant or funding from public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors for the research, authorship, or publication of this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Sewwandi Tennakoon and Eric Danso; methodology: Sewwandi Tennakoon; software: Sewwandi Tennakoon; validation: Sewwandi Tennakoon, Zhenjie Zhao and Eric Danso; formal analysis: Sewwandi Tennakoon and Zhenjie Zhao; investigation: Eric Danso; resources: Zhenjie Zhao; data curation: Zhenjie Zhao; writing—original draft preparation: Sewwandi Tennakoon; writing—review and editing: Sewwandi Tennakoon, Zhenjie Zhao and Eric Danso; visualization: Sewwandi Tennakoon; supervision: Zhenjie Zhao; project administration: Zhenjie Zhao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The anonymized dataset, analysis code, and implementation details are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Materials include curated generative outputs with expert annotations, anonymized participant response data, mixed-effects model code, visualization scripts, and the adaptive explanation framework implementation. Documentation is provided to support replication and verification.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial or non-financial interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Figure A1: Training and validation loss curves for explainability effect predictor

Figure A2: Cross validation results for error detection module

Figure A3: (a) Arm selection dynamics (Thompson Sampling); (b) Cumulative reward convergence

References

1. Bansal G, Nawal A, Chamola V, Herencsar N. Revolutionizing visuals: the role of generative AI in modern image generation. ACM Trans Multimed Comput Commun Appl. 2024;20(11):1–22. doi:10.1145/3689641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Legg M, McNamara V, Alimardani A. The promise and the peril of the use of generative artificial intelligence in litigation. SSRN Electron J. 2025;38(11):1. doi:10.2139/ssrn.5352645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Virvou M, Tsihrintzis GA. Impact of consequenses on human trust dynamics in artificial intelligence responses. In: 2024 15th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems & Applications (IISA); 2024. p. 1–6. doi:10.1109/IISA62523.2024.10786630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zerick J, Kaufman Z, Ott J, Kuber J, Chow E, Shah S, et al. It Takes two to trust: mediating human-AI trust for resilience and reliability. In: 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI); 2024. p. 755–61. doi:10.1109/CAI59869.2024.00145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ahn D, Almaatouq A, Gulabani M, Hosanagar K. Impact of model interpretability and outcome feedback on trust in AI. In: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 1–25. doi:10.1145/3613904.3642780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sinha S, Lee YM. Challenges with developing and deploying AI models and applications in industrial systems. Discov Artif Intell. 2024;4(1):55. doi:10.1007/s44163-024-00151-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wischnewski M, Krämer N, Müller E. Measuring and understanding trust calibrations for automated systems: a survey of the state-of-the-art and future directions. In: Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2023. p. 1–16. doi:10.1145/3544548.3581197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. McIntosh TR, Susnjak T, Arachchilage N, Liu T, Xu D, Watters P, et al. Inadequacies of large language model benchmarks in the era of generative artificial intelligence. IEEE Trans Artif Intell. 2025. 1–18. doi:10.1109/TAI.2025.3569516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pandhare HV. Evaluating large language models: frameworks and methodologies for AI/ML system testing. Int J Sci Res Manag (IJSRM). 2024;12(09):1467–86. doi:10.18535/ijsrm/v12i09.ec08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Johnson DS. Higher Stakes, Healthier Trust? An application-grounded approach to assessing healthy trust in high-stakes human-AI collaboration. arXiv:2503.03529. 2025. [Google Scholar]

11. Erdeniz SP, Trang Tran TN, Felfernig A, Lubos S, Schrempf M, Kramer D, et al. Employing nudge theory and persuasive principles with explainable AI in clinical decision support. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); 2023. p. 2983–9. doi:10.1109/BIBM58861.2023.10385315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Magesh V, Surani F, Dahl M, Suzgun M, Manning CD, Ho DE. Hallucination‐free? Assessing the reliability of leading AI legal research tools. J Empir Leg Stud. 2025;22(2):216–42. doi:10.1111/jels.12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Perez-Cerrolaza J, Abella J, Borg M, Donzella C, Cerquides J, Cazorla FJ, et al. Artificial intelligence for safety-critical systems in industrial and transportation domains: a survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2024;56(7):1–40. doi:10.1145/3626314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Eriksson E, Yoo D, Bekker T, Nilsson EM. More-than-human perspectives in human-computer interaction research: a scoping review. In: Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2024. p. 1–18. doi:10.1145/3679318.3685408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dix A. Human–computer interaction, foundations and new paradigms. J Vis Lang Comput. 2017;42(5895):122–34. doi:10.1016/j.jvlc.2016.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liang P, Bommasani R, Lee T, Tsipras D, Soylu D, Yasunaga M, et al. Holistic evaluation of language models; 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 22]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2211.09110. [Google Scholar]

17. Lin S, Hilton J, Evans O. TruthfulQA: measuring how models mimic human falsehoods; 2022 [cited 2025 Sep 22]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2109.07958. [Google Scholar]

18. Zhang K, Wu L, Yu K, Lv G, Zhang D. Evaluating and improving robustness in large language models: a survey and future directions; 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 22]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2506.11111. [Google Scholar]

19. Deng C, Zhao Y, Tang X, Gerstein M, Cohan A. Investigating data contamination in modern benchmarks for large language models; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 22]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2311.09783. [Google Scholar]

20. Wu X, Wang Y, Wu H-T, Tao Z, Fang Y. Evaluating fairness in large vision-language models across diverse demographic attributes and prompts; 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 22]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.17974. [Google Scholar]

21. Moenks N, Penava P, Buettner R. A systematic literature review of large language model applications in industry. IEEE Access. 2025;13(4):160010–33. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3608650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ozdemir O, Fatunmbi TO. Explainable AI (XAI) in healthcare: bridging the gap between accuracy and interpretability. J Sci, Technol Eng Res. 2024;2(1):32–44. doi:10.64206/0z78ev10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Neha F, Bhati D, Shukla DK. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) in healthcare: a comprehensive review. AI. 2025;6(9):226. doi:10.3390/ai6090226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Poursabzi-Sangdeh F, Goldstein DG, Hofman JM, Wortman Vaughan JW, Wallach H. Manipulating and Measuring Model Interpretability. In: Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 1–52. doi:10.1145/3411764.3445315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bansal G, Wu T, Zhou J, Fok R, Nushi B, Kamar E, et al. Does the whole exceed its parts? The effect of AI explanations on complementary team performance. In: Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2021. p. 1–16. doi:10.1145/3411764.3445717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Buçinca Z, Malaya MB, Gajos KZ. To trust or to think. Proc ACM Hum Comput Interact. 2021;5(CSCW1):1–21. doi:10.1145/3449287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sahoh B, Choksuriwong A. The role of explainable Artificial Intelligence in high-stakes decision-making systems: a systematic review. J Ambient Intell Humaniz Comput. 2023;14(6):7827–43. doi:10.1007/s12652-023-04594-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Barr Kumarakulasinghe N, Blomberg T, Liu J, Saraiva Leao A, Papapetrou P. Evaluating local interpretable model-agnostic explanations on clinical machine learning classification models. In: 2020 IEEE 33rd International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS); 2020. p. 7–12. doi:10.1109/CBMS49503.2020.00009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Salih AM, Raisi-Estabragh Z, Galazzo IB, Radeva P, Petersen SE, Lekadir K, et al. A perspective on explainable artificial intelligence methods: SHAP and LIME. Adv Intell Syst. 2025;7. doi:10.1002/aisy.202400304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kaur H, Nori H, Jenkins S, Caruana R, Wallach H, Wortman Vaughan J. Interpreting interpretability: understanding data scientists’ use of interpretability tools for machine learning. In: Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 1–14. doi:10.1145/3313831.3376219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Jain S, Wallace BC. Attention is not explanation; 2019 [cited 2025 Sep 22]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.10186. [Google Scholar]

32. Afchar D. Interpretable music recommender systems [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Sep 22]. Available from: https://theses.hal.science/tel-04496395v1. [Google Scholar]

33. Lewis P, Perez E, Piktus A, Petroni F, Karpukhin V, Goyal N, et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 22]. Available from: https://github.com/huggingface/transformers/blob/master/. [Google Scholar]

34. Bandi A, Adapa PVSR, Kuchi YEVPK. The power of generative AI: a review of requirements, models, input–output formats, evaluation metrics, and challenges. Future Inter. 2023;15(8):260. doi:10.3390/fi15080260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rauh M, Marchal N, Manzini A, Hendricks LA, Comanescu R, Akbulut C, et al. Gaps in the safety evaluation of generative AI. Proc AAAI/ACM Conf AI Ethics Soc. 2024;7:1200–17. doi:10.1609/aies.v7i1.31717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Atkinson D, Morrison J. A legal risk taxonomy for generative artificial intelligence. arXiv:2404.09479. 2024. [Google Scholar]

37. Ni S, Chen G, Li S, Chen X, Li S, Wang B, et al. A survey on large language model benchmarks. arXiv:2508.15361. 2025. [Google Scholar]

38. Anjum K, Arshad MA, Hayawi K, Polyzos E, Tariq A, Serhani MA, et al. Domain specific benchmarks for evaluating multimodal large language models. arXiv:2506.12958. 2025. [Google Scholar]

39. Ji W, Yuan W, Getzen E, Cho K, Jordan MI, Mei S, et al. An overview of large language models for statisticians; 2025. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2502.17814. [Google Scholar]

40. Cheng TH. Transparency paradox in practice: a comparative analysis of disclosure approaches in LLM Systems; 2025. p. 256–62. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-94171-9_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Gerlich M. AI tools in society: impacts on cognitive offloading and the future of critical thinking. Societies. 2025;15(1):6. doi:10.3390/soc15010006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Yang L, Wang Y, Fang Z, Huang Y, Yang E. Cost-optimized crowdsourcing for NLP via worker selection and data augmentation. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2025;12(4):3343–59. doi:10.1109/TNSE.2025.3559342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Albert DA, Smilek D. Comparing attentional disengagement between prolific and MTurk samples. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):20574. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-46048-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools