Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Attitude Estimation Using an Enhanced Error-State Kalman Filter with Multi-Sensor Fusion

1 School of Electrical Engineering and Automation, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, Ganzhou, 341000, China

2 CRRC Academy, Beijing, 100000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yang Jie. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 549-570. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.072727

Received 02 September 2025; Accepted 21 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

To address the issue of insufficient accuracy in attitude estimation using Inertial Measurement Units (IMU), this paper proposes a multi-sensor fusion attitude estimation method based on an improved Error-State Kalman Filter (ESKF). Several adaptive mechanisms are introduced within the standard ESKF framework: first, the process noise covariance is dynamically adjusted based on gyroscope angular velocity to enhance the algorithm’s adaptability under both static and dynamic conditions; second, the Sage-Husa algorithm is employed to estimate the measurement noise covariance of the accelerometer and magnetometer in real-time, mitigating disturbances caused by external accelerations and magnetic fields. Additionally, a dual-mode correction strategy is proposed for yaw angle estimation: a computationally efficient quaternion-based direct correction method is used for small-angle errors, while the system switches to a higher-precision adaptive ESKF algorithm for large-angle deviations. This strategy ensures estimation accuracy while effectively reducing computational complexity. Experimental results in mixed static-dynamic scenarios show that the proposed algorithm achieves the lowest root mean square error (RMSE) in roll (5.638°) and yaw (6.315°), and ranks first in pitch (2.616°), validating the effectiveness of the improvements. In magnetic interference tests, it delivers the best overall performance, achieving the highest accuracy in roll and yaw and near-optimal performance in pitch, highlighting its excellent anti-interference capability and dynamic tracking performance. Complexity analysis further confirms a significant reduction in computational time compared to the standard ESKF. The results consistently demonstrate that the proposed method offers higher estimation accuracy and robustness under complex conditions, making it suitable for practical applications involving magnetic disturbances and rapid motions.Keywords

In recent years, attitude estimation technology based on Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS) Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) has become an indispensable core sensing method in fields such as robotic motion control, Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) flight stabilization, virtual/augmented reality interaction, and human motion capture [1]. However, inherent limitations of MEMS sensors, such as thermal drift and noise, significantly restrict the accuracy and long-term reliability of attitude estimation, while external disturbances and motion-induced acceleration further exacerbate these issues [2]. To overcome these limitations and achieve high-precision, highly robust attitude estimation, it is essential to effectively fuse multi-source sensor data and perform systematic error compensation [3]. Current mainstream attitude estimation methods are mainly divided into two categories: complementary filtering and Kalman filtering [4].

Complementary filtering has a simple structure and low computational overhead, but its estimation accuracy deteriorates sharply in environments with intense motion and magnetic interference. To address these issues, Literature [5] employed a PI controller for sensor fusion, whose integral term estimates gyroscope bias online to suppress attitude drift, with stability guaranteed by Lyapunov theory. To optimize efficiency, Literature [6] developed a gradient descent orientation filter that minimizes the error between calculated and measured vector directions, enabling high-precision updates with minimal computation. Literature [7] presents an adaptive complementary filter that employs least squares estimation to auto-tune its gains, eliminating manual tuning and demonstrating superior performance over fixed-gain filters. Literature [8] proposes a Double-Complementary Filter (DCF) that decouples magnetometer interference from pitch/roll estimation by isolating it to yaw correction within a two-layer architecture, effectively mitigating magnetic disturbances.

Kalman filtering excels in theoretical rigor and accuracy in dynamic environments but heavily relies on precise system models, involves complex parameter tuning processes, and has high computational complexity. To tackle these problems, Literature [9] proposed a novel dual-stage Kalman filter with reduced computational complexity, enabling high-precision, real-time orientation tracking on a low-cost, compact integrated IMU chip. Literature [10] introduced differential manifold theory, describing attitudes in the Lie group space, which better aligns with their geometric nature, thereby resolving the structural distortion issues caused by linear approximation in traditional Kalman filtering in three-dimensional rotation space. Based on the standard Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) algorithm, Literature [11] enhances the accuracy and robustness of attitude estimation by adaptively adjusting parameters, dynamically processing noise, introducing correction factors, and eliminating anomalous data points. Literature [12] proposes an interval type-3 fuzzy adaptive extended Kalman filter that enhances attitude estimation accuracy for low-cost sensors by dynamically tuning noise covariance.

To enhance the algorithm’s adaptability and robustness in complex dynamic environments, this paper introduces an improved Sage-Husa adaptive mechanism within the ESKF framework. This mechanism dynamically estimates the process noise covariance matrix Q and the measurement noise covariance matrix R online: Q is adjusted adaptively based on the angular rate magnitude, combined with an exponential smoothing strategy to ensure numerical stability; R is updated recursively according to the real-time innovation covariance. A multi-stage anomaly detection mechanism is designed to address the susceptibility of the magnetometer to interference, incorporating dynamic variations in magnetic field intensity, steady-state deviations, and valid range checks. Based on this, a dual-path update strategy for yaw angle correction is implemented: when the yaw angle deviation is significant, a full ESKF measurement update is performed; for minor deviations, a direct correction method based on the minimum-bias rotation quaternion is adopted, ensuring accuracy while significantly reducing computational complexity.

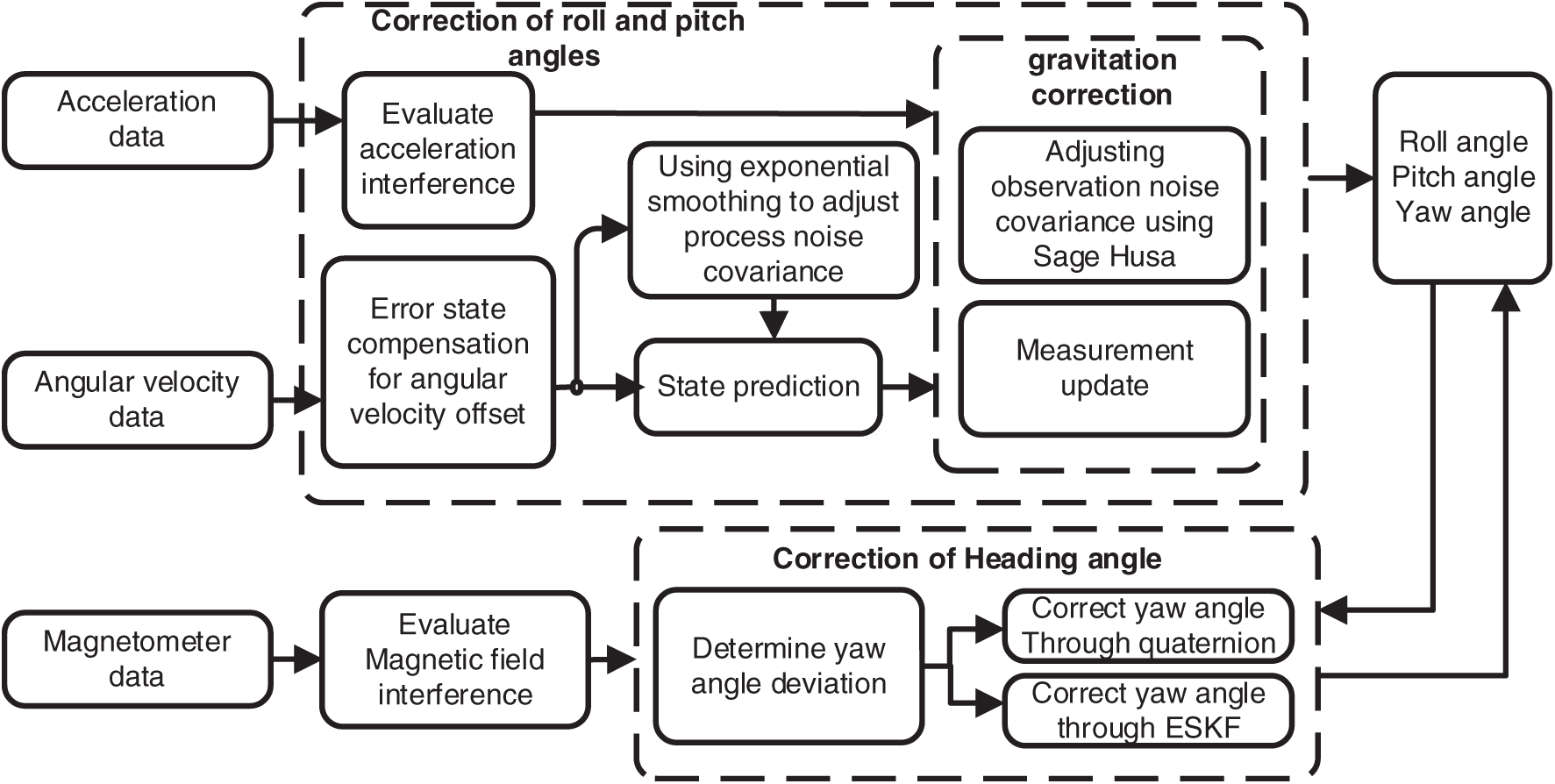

The ESKF algorithm directly estimates the error quantities of the system state and performs linearization operations in the error state space. This approach effectively avoids direct linearization of the original complex nonlinear system equations, thereby reducing approximation errors introduced by linearization and lowering computational burden [13,14]. To further enhance the algorithm’s adaptability and robustness under complex dynamic working conditions, this paper introduces key enhancements to the ESKF framework: a Sage-Husa adaptive mechanism is incorporated to respond in real time to system state variations and environmental disturbances, enabling dynamic online updates of the process and measurement noise covariance matrices. To reduce the computational complexity of the algorithm, a magnetic heading correction method based on the minimum-bias rotation quaternion is proposed. When the deviation angle is below a set threshold, this method replaces the magnetometer update module in the ESKF, ensuring both accuracy in yaw angle correction and reduced computational load. The overall architecture of the algorithm is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Framework diagram for improving ESKF algorithm

2.1 Attitude Calculation Based on Quaternions

To describe the attitude transformation in three-dimensional space, it is necessary to establish a spatial attitude transformation model between the body coordinate system (b-frame) and the navigation coordinate system (n-frame, using the NED (North-East-Down) coordinate system). Due to the gimbal lock problem associated with Euler angles, unit quaternions are employed for attitude modeling and updating:

The dynamic change of attitude is driven by the angular velocity

where

The vector transformation from the body frame to the navigation frame can be achieved using the direction cosine matrix:

Using the Z-Y-X Euler angle rotation sequence, the attitude angles (Roll-ϕ, Pitch-θ, Yaw-ψ) can be derived as:

2.2 Attitude Estimation Based on ESKF

The ESKF decomposes the system state into a nominal state and an error state. The nominal state is typically predicted directly through the integration of IMU or other sensor data. This nonlinear integration process ignores various sources of error. As a result, the nominal state can be computed rapidly but exhibits low accuracy and tends to diverge over time. The error state represents the difference between the nominal state and the true state. Instead of directly estimating the complete system state, the ESKF focuses on estimating this error state [15]. In the algorithm presented in this paper, the nominal state of the system is defined as the attitude quaternion

where

The compensated gyroscope measurement

where

where

Using the measurement matrix

Finally, the attitude error

The magnetometer measurement update is a key step in the attitude estimation filter for correcting heading angle drift. The input raw magnetometer vector

To eliminate the influence of magnetic inclination and provide only heading (yaw) observation, the predicted vector his projected onto the local horizontal plane to construct a reference vector

The magnetometer measurement matrix

Similar to the accelerometer measurement update, the Kalman gain

Before feedback correction, the roll and pitch error components in the error state vector are set to zero, retaining only the heading angle error term. The attitude error

2.3 Adaptive ESKF Based on Improved Sage-Husa

The aforementioned ESKF algorithm assumes that the statistical characteristics of the process noise and observation noise are known and time-invariant. However, in practical applications, these characteristics are often unknown or time-varying, leading to performance degradation of filters based on fixed noise parameters [16]. The Sage-Husa adaptive filtering method can utilize real-time measurement data to adaptively adjust the process noise covariance matrix

However, when both the process noise covariance matrix

In the ESKF algorithm, introducing an improved Sage-Husa adaptive filtering algorithm enables dynamic adjustment of the measurement noise covariance matrix, thereby better handling sensor noise variations and abnormal interference.

2.4 Magnetic Heading Correction Using a Minimum-Bias Rotation Quaternion

This section proposes a magnetic heading correction method based on the minimum deviation rotation quaternion to reduce the computational complexity of the yaw angle correction process. The measured value of the magnetometer in the b-frame be:

Under ideal undisturbed conditions, when the navigation coordinate system (n-frame) aligns with the body coordinate system (b-frame), the magnetic field should primarily distribute along the horizontal and vertical directions [18]:

where

Thus, the estimated yaw angle calculated from the magnetometer can be obtained as:

Define the deviation between the magnetometer-estimated heading value and the ESKF-calculated value

This paper adopts a dual-mode adaptive yaw angle correction mechanism. By setting a threshold for the absolute deviation between the magnetometer-estimated yaw angle and the ESKF-fused output yaw angle, dynamic switching of fusion strategies is achieved, thereby balancing accuracy and computational efficiency. The specific strategies are as follows:

When the absolute deviation

When the absolute deviation is less than or equal to the threshold, a computationally efficient direct quaternion compensation method is employed for fine-tuning. This approach directly adjusts the current attitude through a small-angle rotation quaternion around the Z-axis, significantly reducing computational complexity while enabling rapid and precise adjustments for minor deviations. A small-angle rotation correction quaternion

where

2.5 Anti-Interference Protection Strategy

2.5.1 Hard Iron and Soft Iron Compensation

In attitude estimation systems, magnetometer measurements are often affected by environmental magnetic fields and the structure of the carrier, primarily manifesting as hard iron effects (fixed biases) and soft iron effects (distortions in scale and orientation across axes) [19]. Without proper compensation, the magnetometer output exhibits an ellipsoidal distribution rather than the ideal spherical distribution centered at the origin with a radius equal to the Earth’s magnetic field strength, significantly degrading attitude estimation accuracy. The measurement model of the magnetometer can be expressed as:

where

To achieve calibration, an ellipsoid fitting method is employed. The core idea is to fit the magnetometer data points to a three-dimensional ellipsoid model and then decompose the parameters to compensate for hard and soft iron effects. The general quadratic form of the ellipsoid equation is:

where

Define parameter vector

Constructing Design Matrix

The solution to this problem is the eigenvector corresponding to the minimum eigenvalue of the matrix MT M. Reconstruct the symmetric matrix and vector from the solution p:

Hard iron bias is given by the center of the ellipsoid:

To compensate for soft iron effects, the fitted ellipsoid is normalized. From the ellipsoid equation, it follows that:

where W is the normalized ellipsoid shape matrix, reflecting the scaling and rotational characteristics of the soft iron effect in three-dimensional space W meets:

Performing eigenvalue decomposition on W:

where U is an orthogonal matrix and Λ is a diagonal matrix. The calibration matrix is derived as:

The calibrated magnetometer output is then given by:

Theoretically, the calibrated data should satisfy all points lie on a spherical surface, thereby eliminating the impact of hard and soft iron effects on attitude estimation.

2.5.2 Linear Acceleration and Magnetic Interference

Linear acceleration disrupts the accuracy of the gravitational component in accelerometer measurements, which is a major source of attitude estimation errors [20]. The proposed algorithm uses the Exponentially Weighted Moving Average (EWMA) to compute a smoothed value

where

The Earth’s magnetic field is susceptible to disturbances from ferromagnetic materials in the environment, causing drift in yaw angle estimation [21]. Similar to acceleration detection, the system calculates the relative EWMA deviation

If

The anomaly detection module not only relies on relative EWMA deviation to perceive signal mutations, but also sets an absolute threshold as a safety guarantee to ensure that the system can effectively identify and respond to continuous external interference.

3 Experimental Tests and Results Analysis

To evaluate the performance of the improved ESKF attitude estimation method (denoted as ESKF-MYC) under different operational conditions, this study conducted two categories of validation experiments: dynamic and static mixed experiment and magnetic interference experiments.

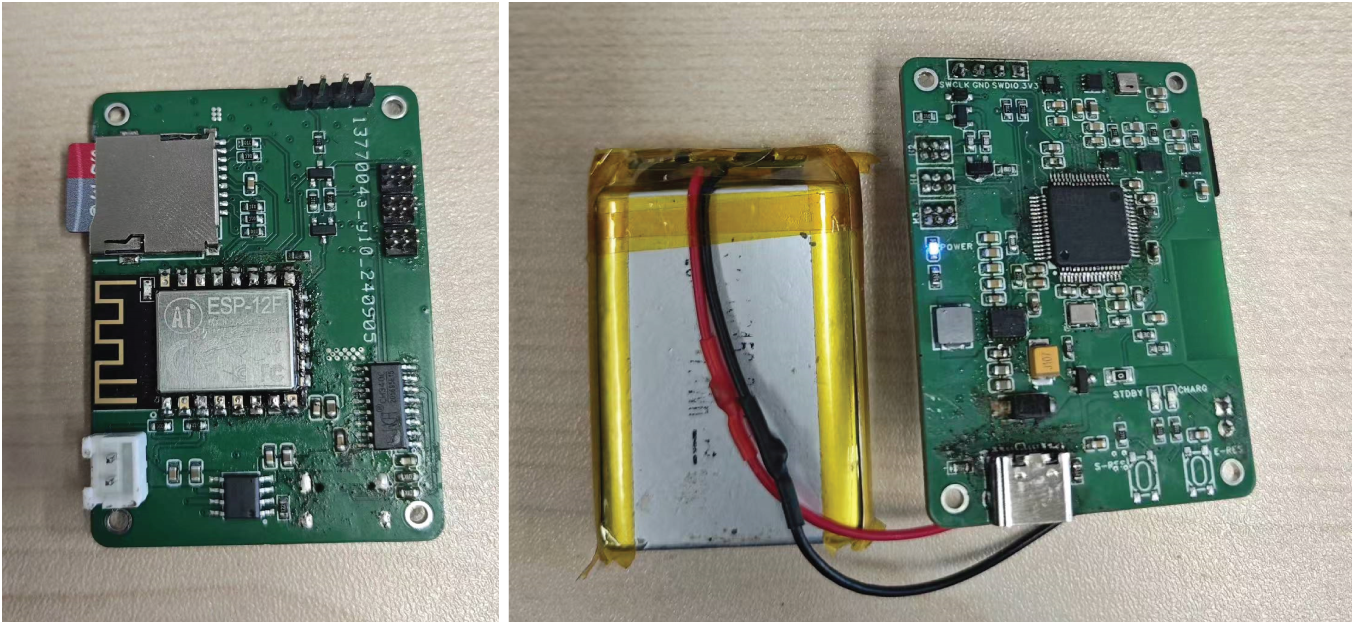

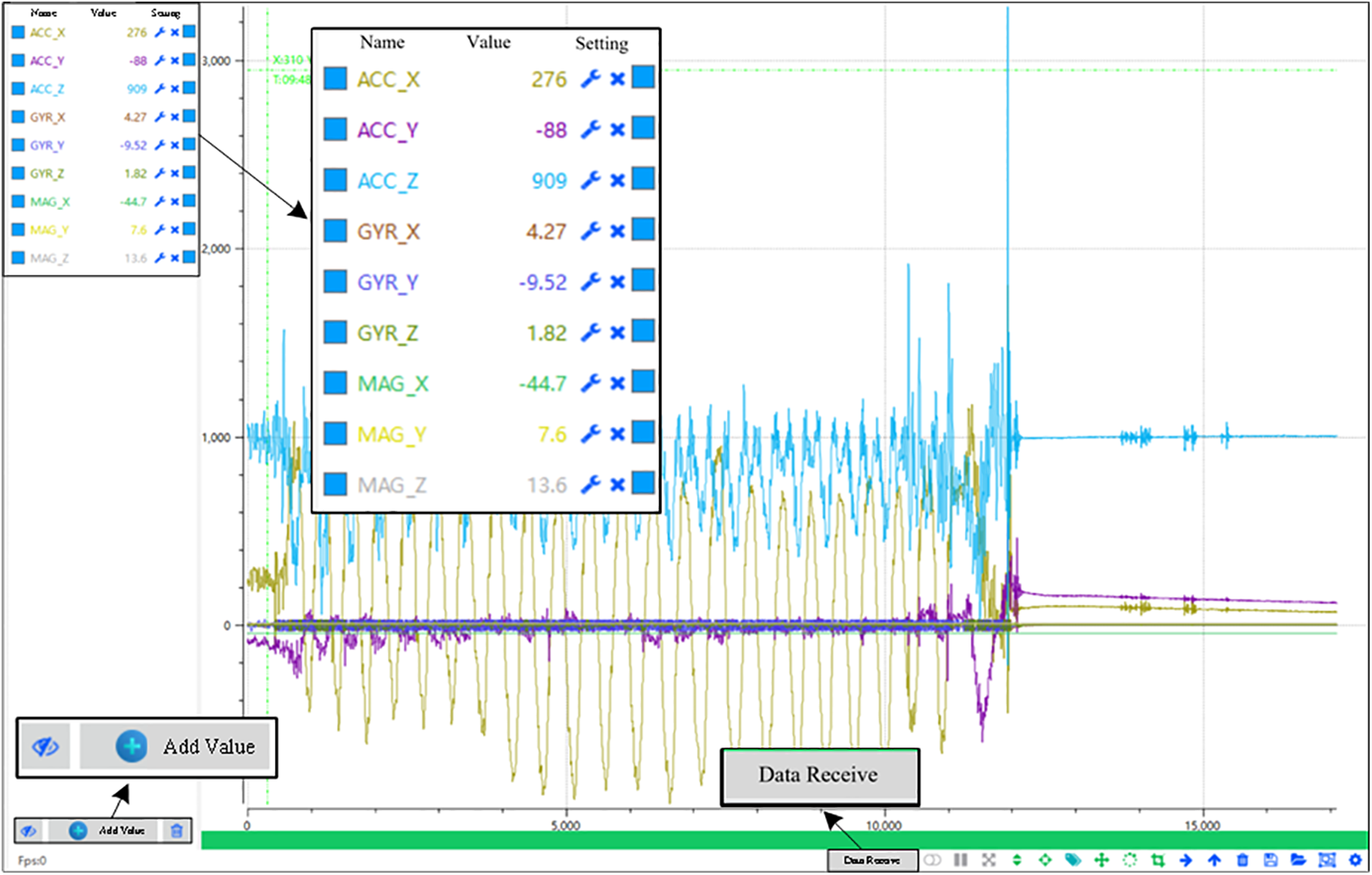

The dynamic and static mixed experiment utilized the real-time attitude monitoring device shown in Fig. 2 as the data acquisition platform. This device collects raw data from MEMS inertial sensors and transmits it in real time to the monitoring terminal (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Real time attitude monitoring equipment

Figure 3: Monitoring terminal interface

To prevent limitations that could arise from a single hardware configuration and to further examine the algorithm’s generalization capability and resilience to magnetic interference across IMUs with varying noise characteristics, this study also selected sequences involving magnetic interference from the public Berlin Robust Orientation Estimation Assessment Dataset (BROAD) [22] for additional validation.

To ensure objective comparison, all collected data—whether from our self-developed platform or the public dataset—were processed offline in MATLAB under a unified evaluation framework. In terms of comparative algorithm selection, in addition to the Error State Kalman Filter (ESKF) algorithm, two representative complementary filter-based attitude estimation methods were introduced: the Mahony algorithm [5] and its improved version, the Madgwick algorithm [6]. The Madgwick algorithm enhances the attitude estimation process by introducing a gradient descent strategy, which effectively improves attitude convergence accuracy and stability while reducing the number of tuning parameters to one. The two sets of experiments conducted a comparative analysis of the performance of the aforementioned algorithms and the proposed ESKF-MYC algorithm, and the results are discussed.

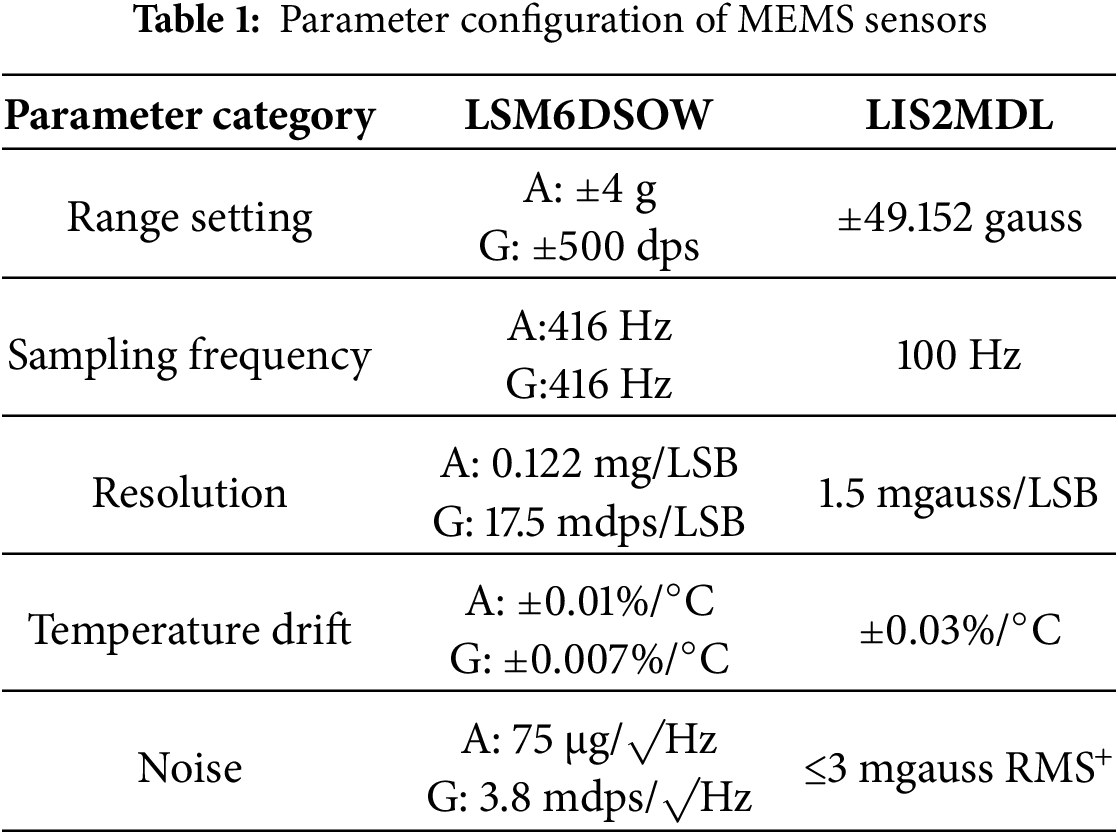

To achieve high-precision, low-power attitude measurement, the device integrates two MEMS sensors: the LSM6DSOW and the LIS2MDL. The sensor parameters are listed in Table 1, where A denotes the accelerometer and G denotes the gyroscope.

3.1 Dynamic and Static Mixed Experiment

To validate the performance of the proposed attitude estimation method in mixed static-dynamic scenarios, the following experimental procedure was designed: The attitude monitoring device was fixed on one side of a rigid acrylic board, while a high-precision attitude sensor HWT905 (accuracy: ±0.05°) was installed on the opposite side as the ground truth reference (REF.). The experiment was conducted in an open indoor area with a uniform magnetic field distribution and no external interference. Prior to the experiment, the attitude monitoring node was calibrated to align its initial attitude with the reference sensor. During the experiment, complex high-dynamic attitude changes were simulated by rapidly and irregularly moving the acrylic board. Each movement was followed by a period of static holding, and this sequence was repeated four times. In the final stage of the experiment, the movement speed was further increased to test the algorithm’s adaptability and convergence capability during rapid transitions between dynamic and static conditions. Data from both the attitude monitoring node and the reference sensor were synchronously collected and uploaded to the host computer, with a data reporting period set to 3.5 ms. The data acquired by the attitude monitoring node was imported into MATLAB for offline processing, where the attitude angles were computed and compared with the reference attitude angles for analysis. The parameter settings for the comparative algorithms are as follows: Mahony: KP = 10, KI = 0.02; Madgwick: β = 0.8; ESKF: Q = diag([1e−4, 1e−4, 1e−4, 0, 0, 0]), Ra = 10 I2, Rm = 5 I3, The proposed ESKF-MYC was initialized with the same parameters as the ESKF, with the magnetic anomaly correction gain kmag set to 0.002 and the mode-switching threshold set to 0.15 rad.

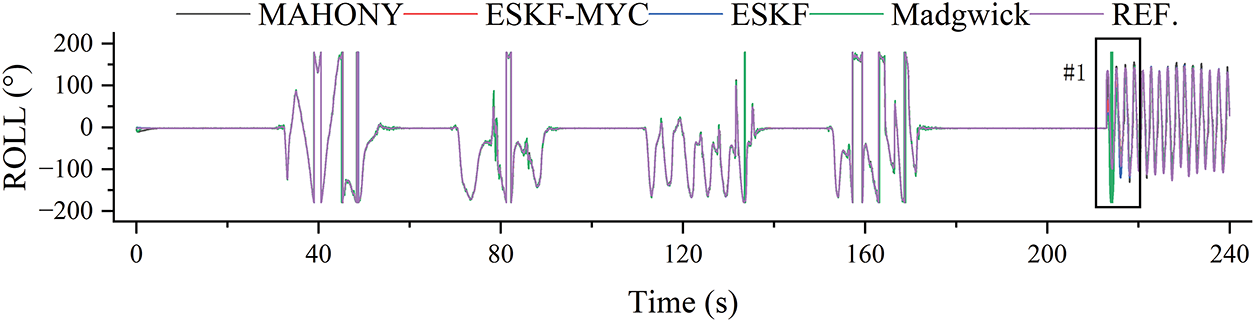

As shown in the static-dynamic solution results of the roll angle (ROLL) in Figs. 4 and 5, during the low-speed motion phase from 0 to 200 s, all algorithms are able to track the reference attitude angle well, with the solution results aligning closely with the ground truth. However, when the experimental setup abruptly enters a rapid motion state at 213 s, significant differences emerge in the responses of the algorithms. Among them, the Mahony algorithm responds most quickly to the dynamic change, but its solution exhibits noticeable jitter, indicating insufficient stability. The ESKF-MYC algorithm follows closely, responding rapidly while maintaining a smooth output trajectory, demonstrating good dynamic performance. In contrast, the ESKF and Madgwick algorithms show relatively slower responses to the rapid motion, with a certain degree of lag observed.

Figure 4: Calculation results of roll angle in dynamic and static mixed experiment

Figure 5: Enlarged detail of #1 location

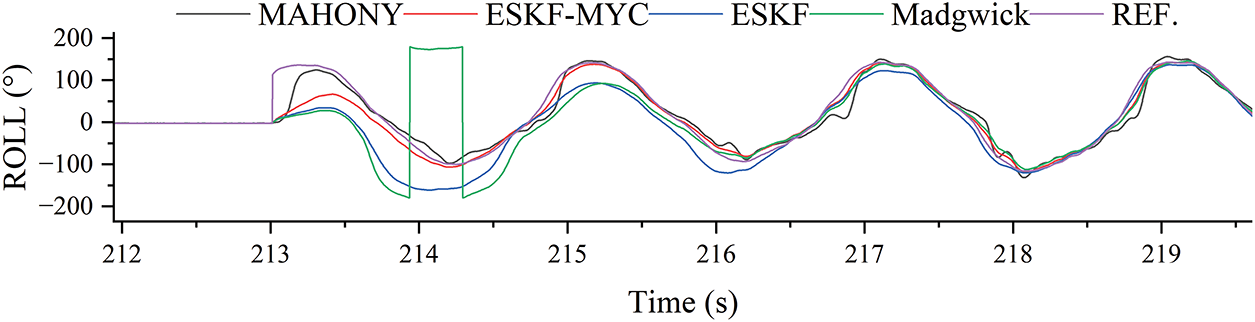

Table 2 presents the roll angle estimation errors of each algorithm in dynamic and static mixed experiment, the ESKF-MYC algorithm achieved the lowest Root Mean Square Error (RMSE = 5.638°), indicating superior overall estimation accuracy and strong robustness against outliers. The ESKF algorithm recorded the lowest Mean Absolute Error (MAE = 1.499°), suggesting more stable estimation performance under most conditions. The Mahony algorithm, while outperforming the Madgwick algorithm (MAE = 3.640°) with an MAE of 2.942°, exhibited a significantly higher RMSE of 8.069°, reflecting noticeable jitter or deviation during dynamic phases. The Madgwick algorithm yielded the highest RMSE (11.467°), indicating poor adaptability to abrupt changes in motion states. Overall, the ESKF-based algorithms demonstrated better performance in mixed static-dynamic scenarios, with ESKF-MYC showing notable effectiveness in controlling maximum error, while the standard ESKF slightly outperformed in terms of steady-state accuracy.

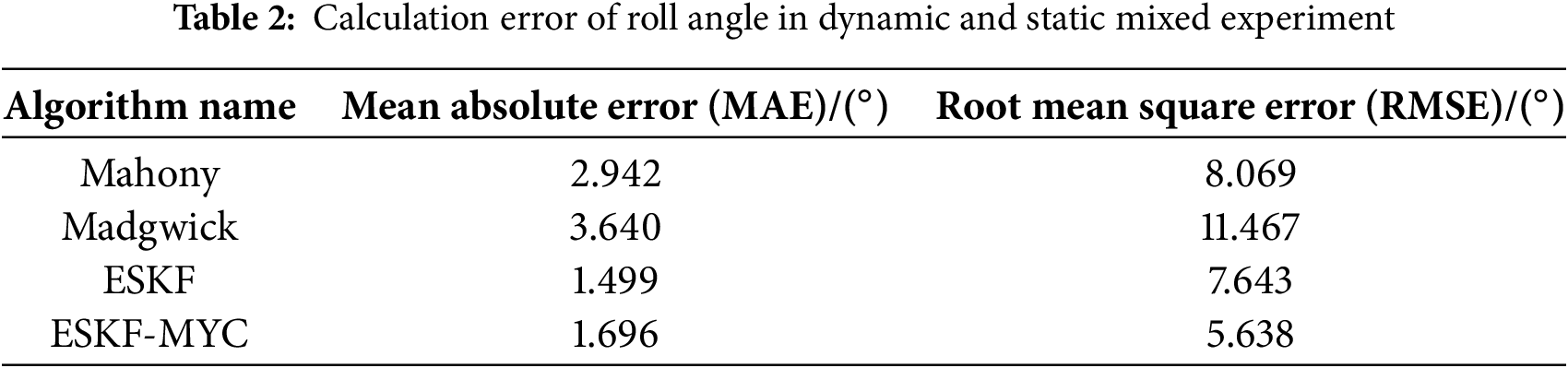

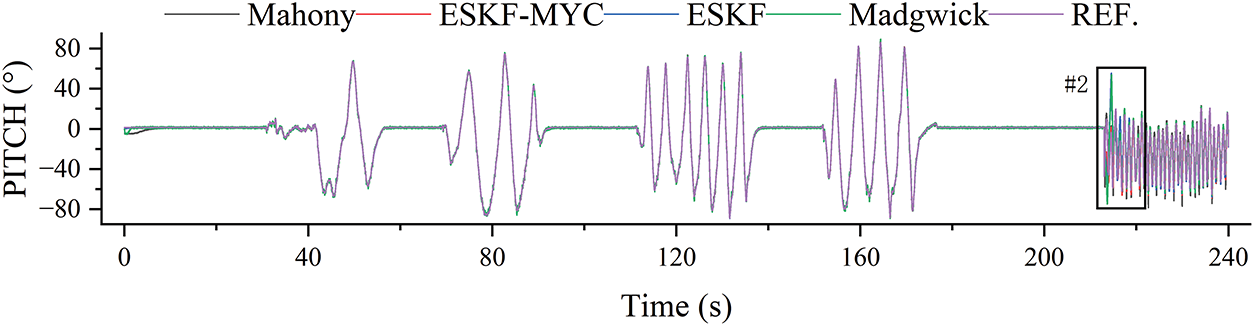

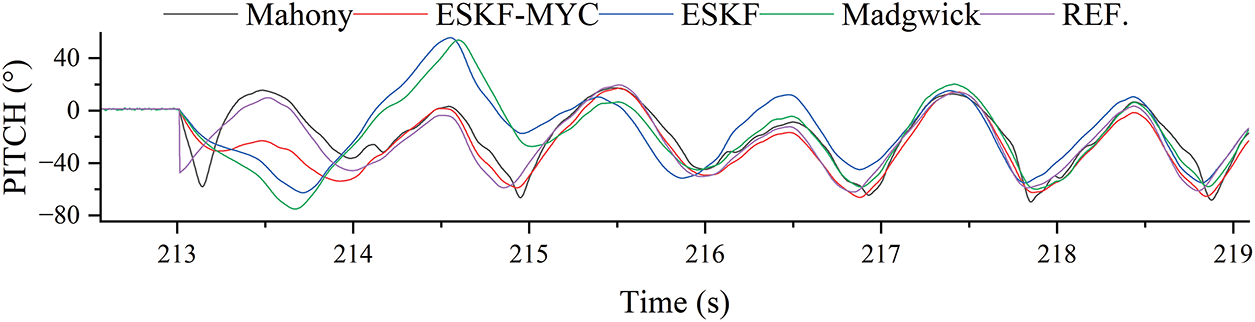

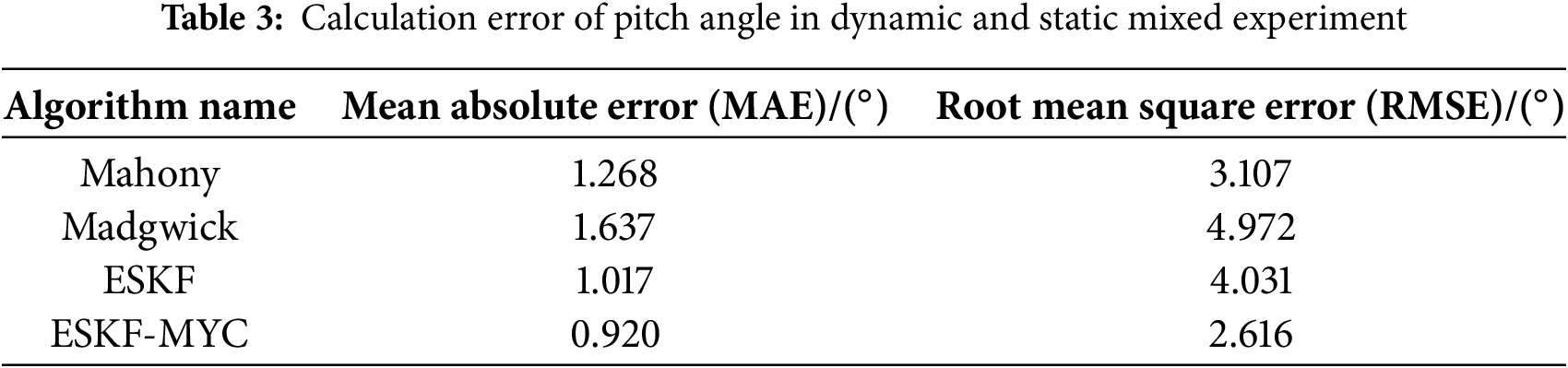

As shown in Figs. 6 and 7, the pitch angle solution results are similar to those of the roll angle. When confronted with sudden angular changes, the Mahony algorithm demonstrates the fastest response and tracks the reference angle effectively. The ESKF-MYC algorithm follows with a slightly slower response speed, while both the Madgwick and ESKF algorithms exhibit relatively slower responses along with significant estimation deviations.

Figure 6: Calculation results of pitch angle in dynamic and static mixed experiment

Figure 7: Enlarged detail of #2 location

Table 3 presents the pitch angle estimation errors of each algorithm in dynamic and static mixed experiment. The ESKF-MYC algorithm achieves the best performance on both error metrics, with an RMSE of 2.616° and an Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 0.920°, demonstrating the highest overall accuracy. The ESKF algorithm ranks second with an MAE of 1.017°. Although the Mahony algorithm has an MAE of 1.268°, its RMSE (3.107°) is superior to that of the Madgwick algorithm (4.972°), indicating better stability. The Madgwick algorithm performs relatively weakly on both metrics. The ESKF-MYC algorithm not only maintains high precision (lowest MAE) but also exhibits the best robustness to outliers (lowest RMSE), confirming its stable performance across various motion states. While the ESKF algorithm has a low MAE, its relatively higher RMSE suggests the occurrence of larger errors during rapid motion. The Mahony algorithm delivers balanced performance with mid-range results for both RMSE and MAE. The notably higher RMSE of the Madgwick algorithm indicates its greater sensitivity to changes in motion state.

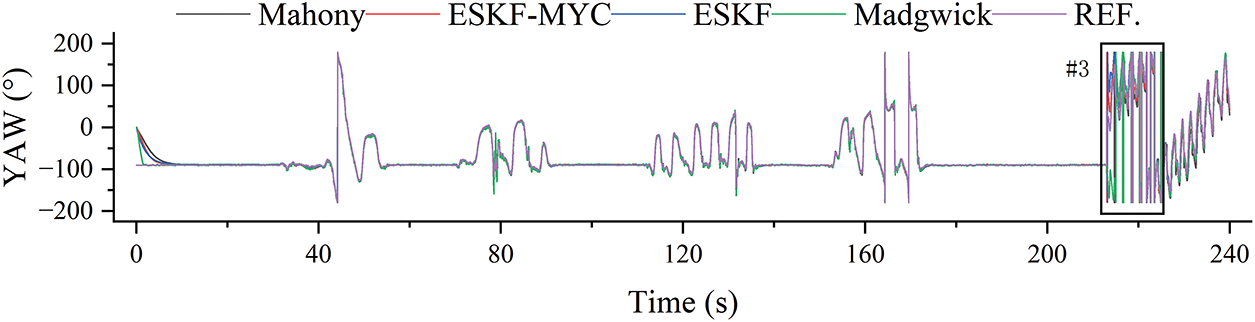

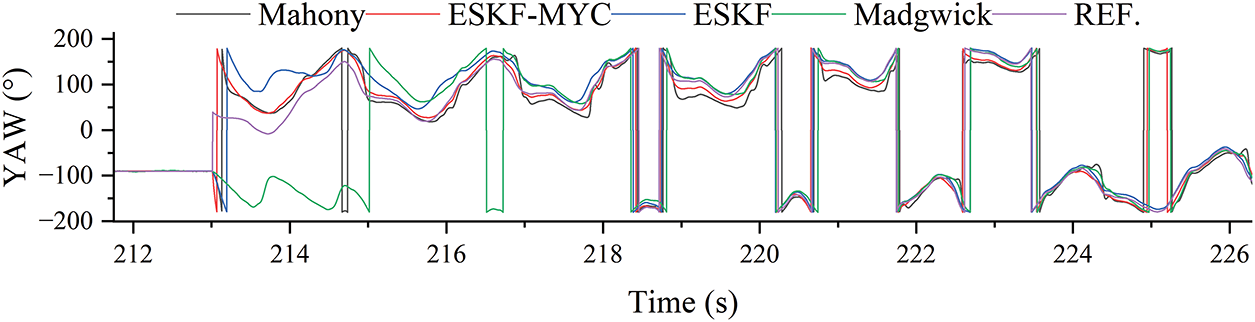

As depicted in Figs. 8 and 9, the yaw angle estimation results demonstrate that the ESKF-MYC algorithm achieves the fastest response to angular changes, producing smooth trajectories that align closely with the reference values. The ESKF algorithm follows with a slightly slower response yet maintains good tracking accuracy. In contrast, the Mahony algorithm exhibits significant jitter in its output, while the Madgwick algorithm responds sluggishly and fails to reflect the actual attitude variations effectively.

Figure 8: Calculation results of yaw angle in dynamic and static mixed experiment

Figure 9: Enlarged detail of #3 location

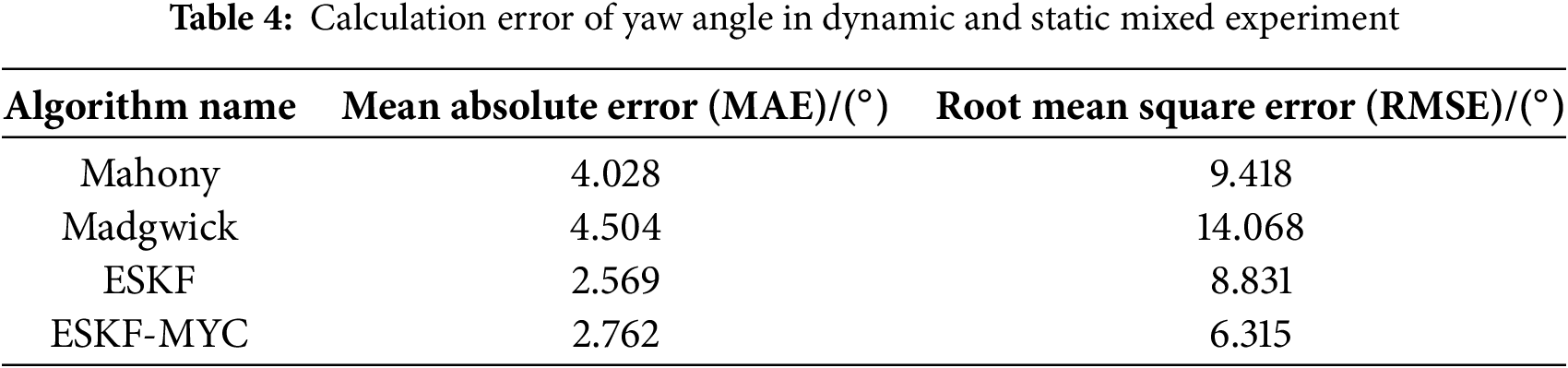

Table 4 presents the yaw angle estimation errors of each algorithm in dynamic and static mixed experiment. The results indicate that the ESKF-MYC algorithm delivers the best performance in terms of Root Mean Square Error (RMSE = 6.315°), demonstrating superior overall estimation accuracy and stability. The ESKF algorithm follows closely (RMSE = 8.831°), and slightly outperforms the ESKF-MYC algorithm in Mean Absolute Error (MAE = 2.569° vs. 2.762°), indicating exceptionally high precision under most normal conditions. In contrast, both the Mahony algorithm (RMSE = 9.418°, MAE = 4.028°) and the Madgwick algorithm (RMSE = 14.068°, MAE = 4.504°) exhibit significantly larger errors.

In summary, the ESKF-MYC algorithm achieves the lowest RMSE in both the roll (RMSE: 5.638°) and yaw (RMSE: 6.315°) dimensions, and ranks first in the pitch angle (RMSE: 2.616°) as well. This fully demonstrates the effectiveness of its improvement strategy, particularly in mixed static-dynamic scenarios that require controlling maximum error and ensuring overall stability, where ESKF-MYC exhibits the strongest comprehensive robustness and the highest accuracy. The ESKF algorithm achieves the best MAE indicators in both the pitch (MAE: 1.017°) and yaw (MAE: 2.569°) angles, indicating that its fundamental design can provide extremely precise estimations under normal conditions without abnormal interference. Its slightly inferior performance in roll angle estimation compared to ESKF-MYC reveals the enhancement effect of the improved algorithm in handling specific dynamic errors. The Mahony and Madgwick algorithms generally exhibit higher errors in three-axis estimation compared to the ESKF-based algorithms, especially in the roll and yaw angles where dynamic performance requirements are higher. This indicates that in scenarios involving rapid motion, the ESKF framework based on the error-state Kalman filter holds a clear advantage over complementary filter methods in terms of both accuracy and stability.

3.2 Magnetic Interference Experiment

The BROAD dataset utilizes a high-precision optical motion capture (OMC) system to obtain the ground-truth attitude of the measurement unit, providing a high-accuracy attitude reference in interference-prone environments. This enables a comprehensive, fair, and reproducible evaluation of algorithm performance. The dataset employs a myon aktos-t nine-axis inertial measurement unit (IMU) to collect IMU data, with a gyroscope range of ±2000°/s, an accelerometer range of ±16 g, and a magnetometer range of ±1 mT. The reference attitude ground truth is provided by an OptiTrack optical motion capture system at a sampling rate of 120 Hz. A specially designed rigid structure ensures a fixed relative pose between the IMU sensor and the optical markers, while an optimization-based time synchronization method aligns timestamps across systems, effectively reducing spatiotemporal deviations between heterogeneous data sources and achieving a comprehensive sampling rate of 287 Hz. To validate the anti-interference performance of the algorithms in magnetically disturbed environments, this section selects data containing magnetic interference scenarios for analysis. The parameter settings for the comparative algorithms are as follows:

Mahony: KP = 5, KI = 0.005; Madgwick: β = 0.5 ;ESKF: Q = diag([5e−5, 5e−5, 5e−5, 0, 0, 0]), Ra = 6.5 I2, Rm = 10 I3. The proposed ESKF-MYC was initialized with the same parameters as the ESKF, with the magnetic anomaly correction gain kmag set to 0.002 and the mode-switching threshold set to 0.3 rad.

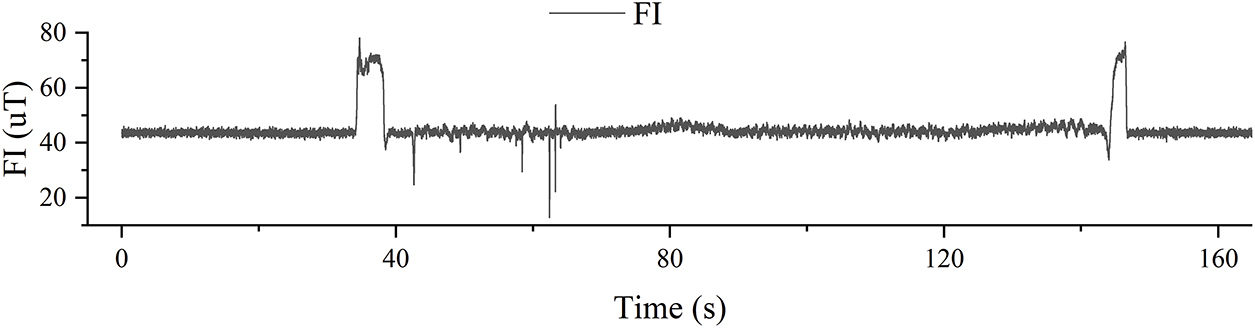

Fig. 10 shows the variation curve of magnetic field intensity over a period of 160 s, clearly illustrating the movement of the IMU unit in the vicinity of the magnetic interference source.

Figure 10: Variation curve of magnetic field intensity

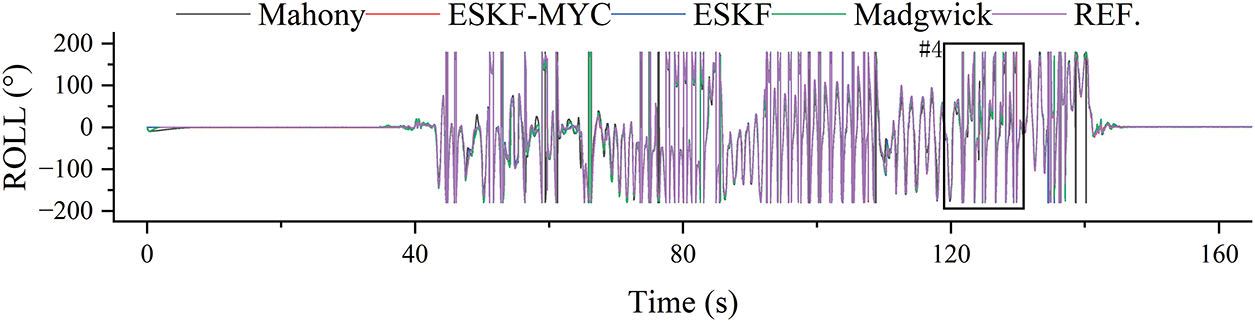

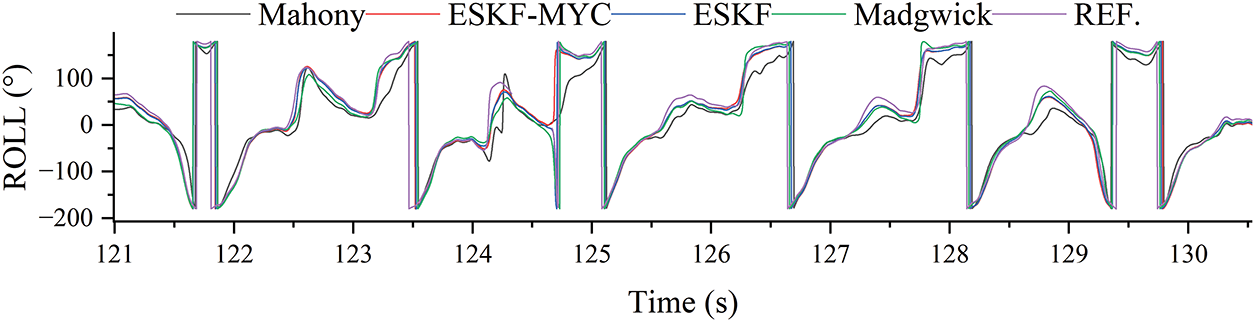

As shown in Figs. 11 and 12, the overall impact of magnetic interference on the roll angle solution is limited, but the algorithms exhibit significant differences in dynamic performance. The ESKF-MYC, ESKF, and Madgwick algorithms are all able to accurately track rapid attitude changes, whereas the Mahony algorithm demonstrates noticeable overshooting and jitter.

Figure 11: Calculation results of roll angle in magnetic interference experiment

Figure 12: Enlarged detail of #4 location

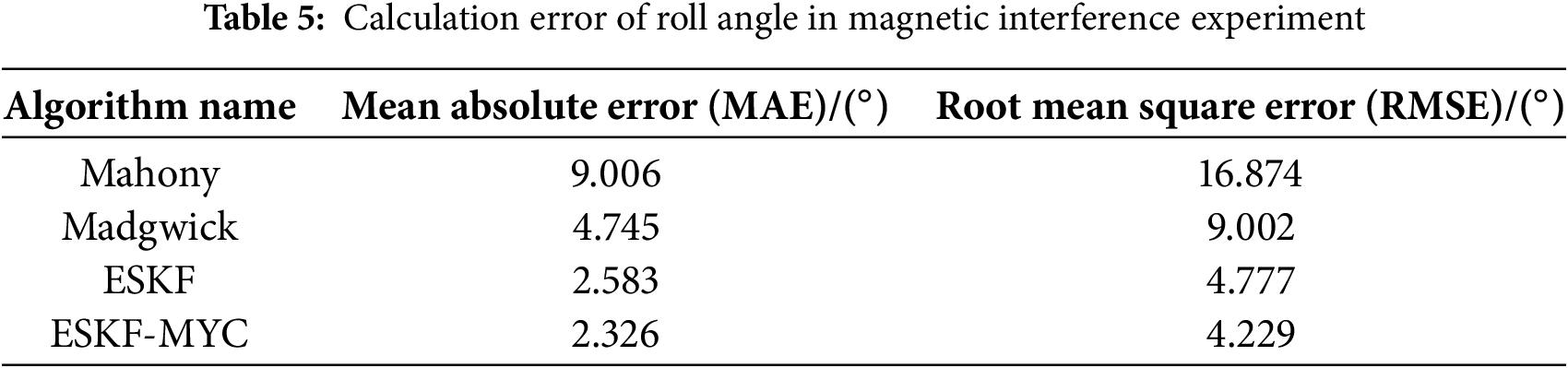

As can be seen from the detailed roll angle (ROLL) solution results in Table 5, the estimation accuracy of the algorithms shows a clear gradient difference. Specifically: the ESKF-MYC algorithm performs optimally, achieving a root mean square error (RMSE) of 4.229° and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 2.326°; the ESKF algorithm follows with corresponding errors of 4.777° and 2.583°; the Madgwick algorithm ranks third with errors of 9.002° and 4.745°; while the Mahony algorithm has the largest solution errors, with RMSE and MAE as high as 16.874° and 9.006°, respectively, indicating significantly lower accuracy compared to the other algorithms. Compared to the baseline ESKF algorithm, the ESKF-MYC algorithm further reduces the RMSE by approximately 11.5%.

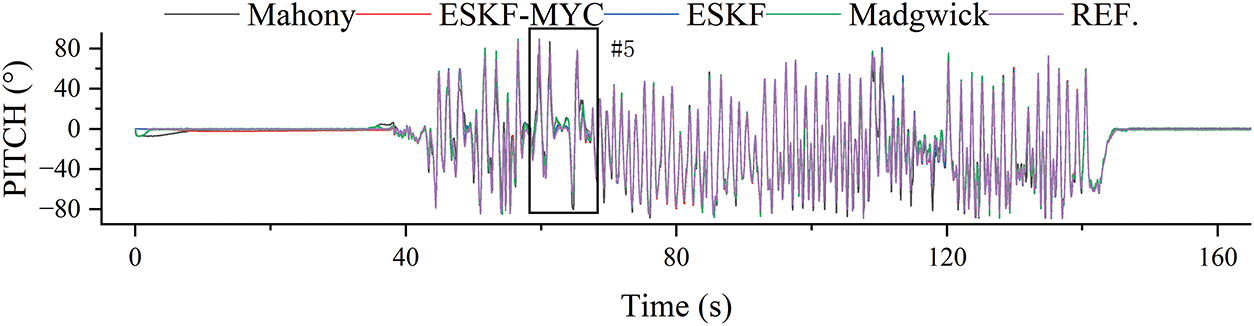

As shown in Figs. 13 and 14, the overall impact of magnetic interference on pitch angle estimation remains relatively limited, with all algorithms generally exhibiting smaller deviations in this dimension compared to other axes. However, notable differences emerge in dynamic performance: both the ESKF-MYC and ESKF algorithms demonstrate accurate tracking capability during rapid attitude variations, while the Madgwick and Mahony algorithms exhibit more pronounced overshooting and jitter, indicating their relatively inferior dynamic response performance and stability.

Figure 13: Calculation results of pitch angle in magnetic interference experiment

Figure 14: Enlarged detail of #5 location

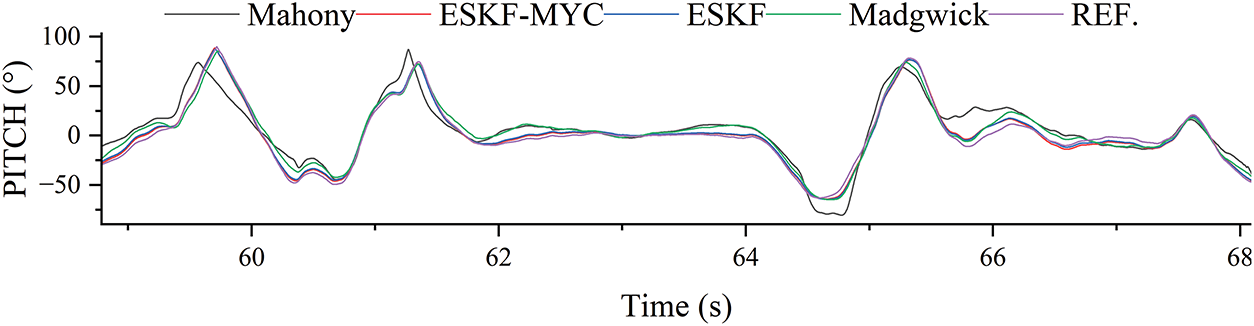

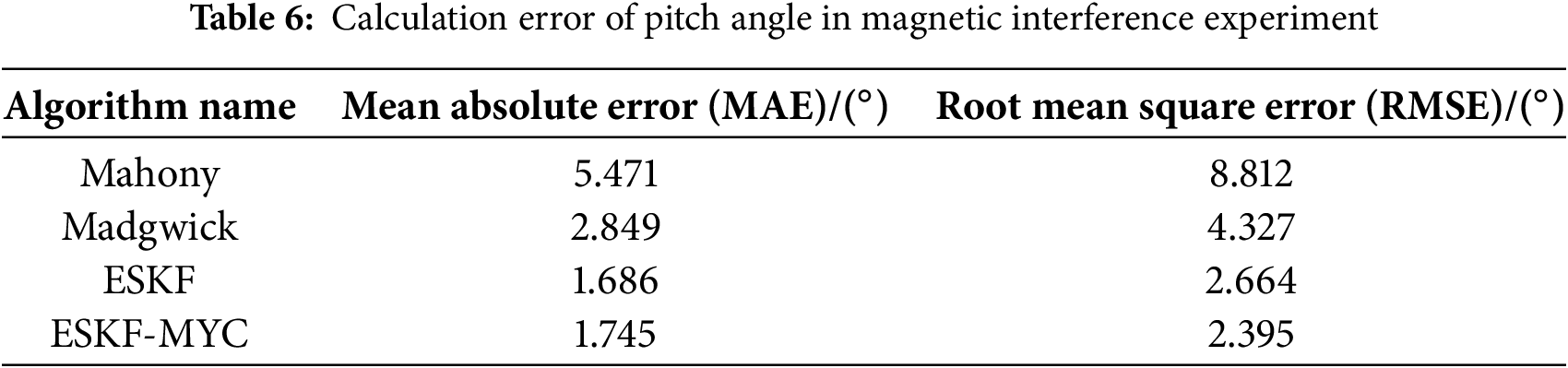

The pitch angle solution results in Table 6 clearly demonstrate the accuracy gradient among the algorithms. The ESKF-MYC algorithm achieves optimal performance with errors of 2.395° (RMSE) and 1.745° (MAE), representing an approximate 10.8% improvement in accuracy compared to the ESKF algorithm, which has an RMSE of 2.686° and MAE of 1.849°. The errors of the Madgwick algorithm (RMSE: 4.327°, MAE: 2.849°) and Mahony algorithm (RMSE: 5.471°, MAE: 3.812°) increase progressively, ranking third and fourth respectively in terms of performance.

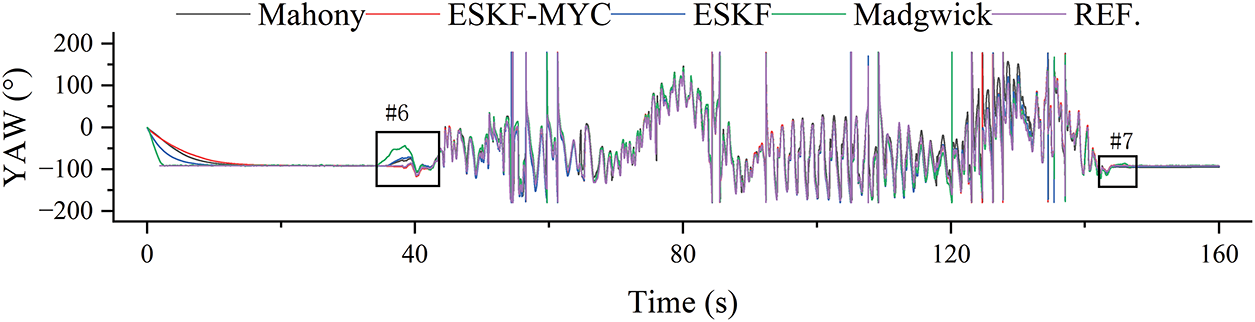

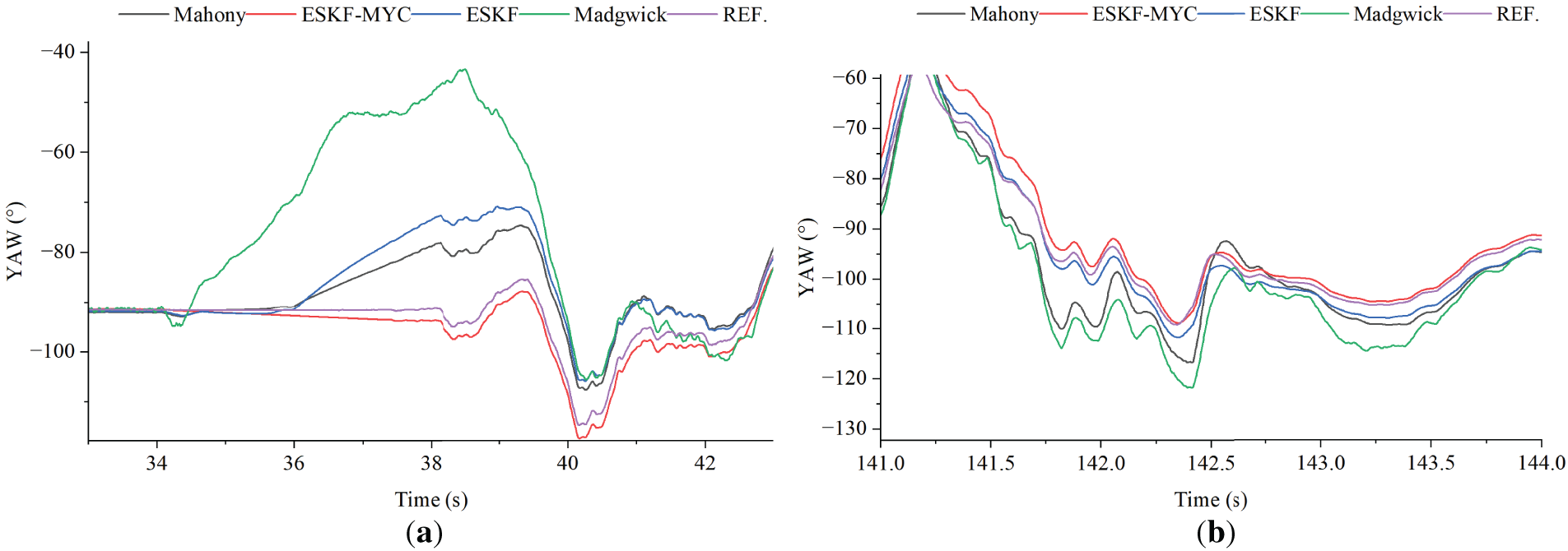

As shown in Figs. 15 and 16, magnetic interference has a significant impact on the yaw angle solution. At position #6, the ESKF-MYC algorithm detects the magnetic interference and disables the magnetometer correction, thereby effectively immunizing itself against this disturbance. The other algorithms, however, are all affected by the sudden magnetic field change to varying degrees, with the Madgwick algorithm experiencing the most severe impact. At position #7, both the ESKF-MYC and ESKF algorithms are able to track the reference angle well, while the Mahony and Madgwick algorithms still exhibit noticeable estimation deviations.

Figure 15: Calculation results of yaw angle in magnetic interference experiment

Figure 16: Enlarged detail of #6 and #7 location. (a) Enlarged detail of #6 location; (b) Enlarged detail of #7 location

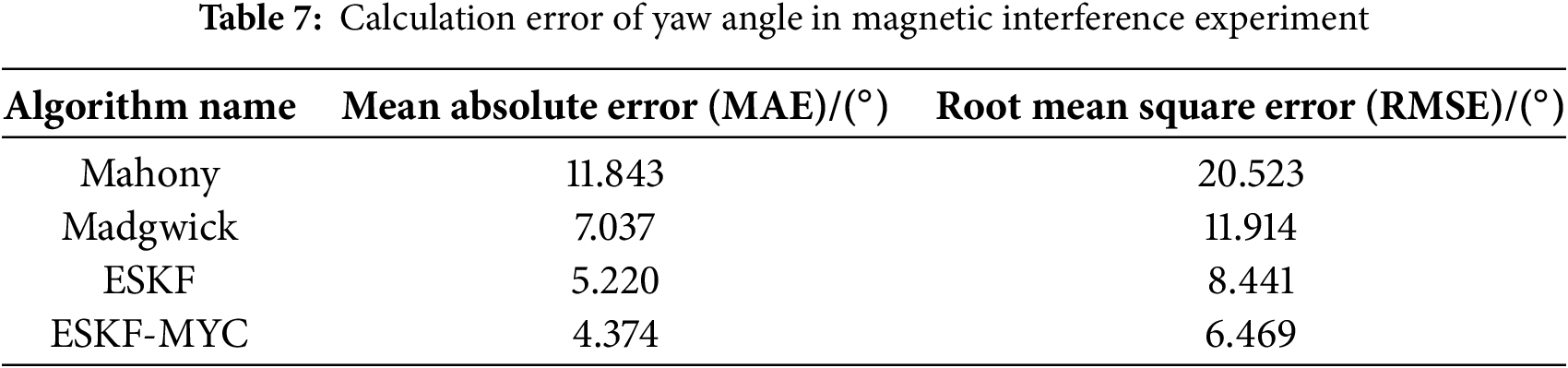

As evidenced by the yaw angle estimation errors in Table 7, significant performance disparities exist among the algorithms in magnetically disturbed environments. The ESKF-MYC algorithm outperforms all comparative methods in both Root Mean Square Error (RMSE = 6.469°) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE = 4.374°), demonstrating superior anti-interference capability and estimation accuracy. The ESKF algorithm follows with RMSE and MAE of 8.441° and 5.220°, respectively, maintaining stable overall performance. The Madgwick algorithm shows substantially increased errors (RMSE = 11.914°, MAE = 7.037°), indicating relatively weak robustness against magnetic disturbances. The Mahony algorithm exhibits the largest estimation errors (RMSE = 20.523°, MAE = 11.843°), significantly exceeding other algorithms and revealing poor adaptability in strong magnetic interference environments. In summary, the ESKF-MYC algorithm demonstrates the strongest robustness and highest precision in yaw angle estimation, making it particularly suitable for practical applications involving magnetic disturbances.

The experimental results in this section demonstrate that the ESKF-MYC algorithm achieves the best overall performance. It delivers the highest accuracy in both roll (ROLL) and yaw (YAW) angles, while maintaining near-optimal performance in pitch (PITCH) angle estimation, exhibiting excellent anti-interference capability and dynamic stability. The ESKF algorithm shows robust performance, ranking second. In contrast, both the Madgwick and Mahony algorithms, particularly in yaw angle estimation and anti-magnetic interference performance, demonstrate significantly larger errors compared to the ESKF-based algorithms. Overall, the ESKF-MYC algorithm demonstrates substantial advantages in both accuracy and robustness under complex scenarios, making it more suitable for practical applications involving magnetic disturbances and rapid motions.

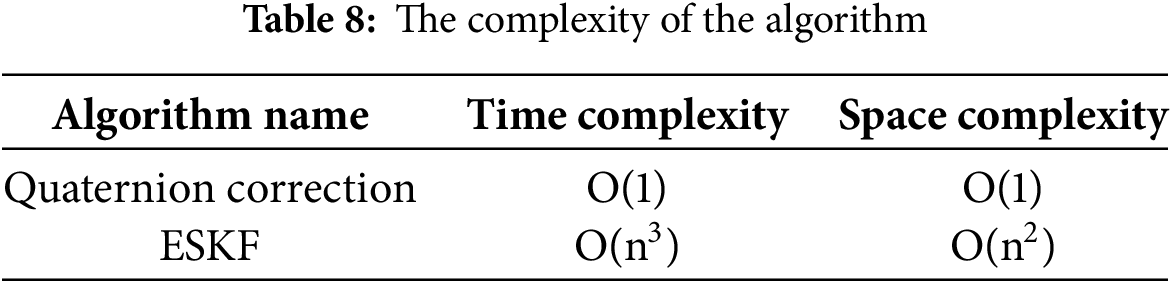

4 Algorithm Complexity Analysis

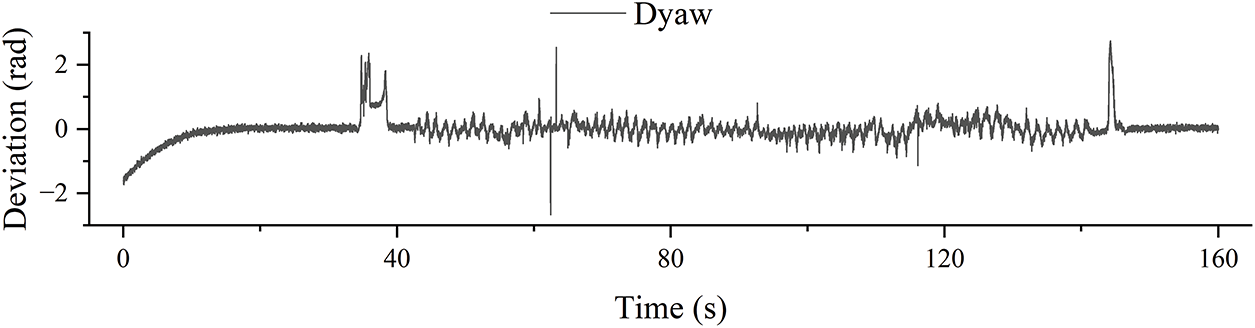

This paper proposes a dual-mode correction strategy for yaw angle estimation: a computationally efficient quaternion-based direct correction method is employed for small-angle errors, while the system switches to a higher-precision adaptive ESKF algorithm for large-angle error conditions. The distribution of yaw angle errors from the magnetic interference experiment is shown in the Fig. 17, with the mode-switching threshold set at 0.3 rad. The time and space complexity of the two correction algorithms are compared in the following Table 8:

Figure 17: Variation of yaw angle deviation angle in magnetic interference experiment

All pose estimation algorithms in this study were tested on the MATLAB platform, using a laptop equipped with an AMD Ryzen 7 6800H processor and 16 GB of memory. In the 160-s magnetic interference data experiment, the processing time of the ESKF-MYC algorithm was only 1.111 s, which is approximately 11.5% faster than the 1.255 s required by the standard ESKF algorithm. In the 240-s mixed experiment involving both dynamic and static phases, with the mode switching threshold set to 0.15 rad, the processing time of the proposed algorithm was only 1.410 s, significantly outperforming the 1.671 s of the standard ESKF algorithm, with a computational efficiency improvement of approximately 15.6%. The results demonstrate that the proposed dual-mode switching strategy effectively enhances computational efficiency while maintaining estimation accuracy.

This research focuses on enhancing the accuracy of attitude estimation based on inertial measurement units. Through methodological improvements and systematic experimental validation, a multi-sensor fusion attitude estimation method based on an improved Error-State Kalman Filter (ESKF) is proposed. The approach deeply integrates two key innovations within the standard ESKF framework: a real-time measurement noise estimation strategy using an improved Sage-Husa algorithm, and a dual-mode switching method for yaw angle correction. These enhancements significantly improve the algorithm’s adaptability and estimation accuracy in mixed static-dynamic scenarios.

Experimental results under mixed static-dynamic environmental conditions demonstrate that the proposed ESKF-MYC algorithm achieves optimal estimation accuracy in both roll angle (RMSE = 5.638°) and yaw angle (RMSE = 6.315°), while also exhibiting the best performance in pitch angle (RMSE = 2.616°), fully validating the effectiveness of the proposed improvement strategies.

Magnetic interference experiments based on the BROAD public dataset further confirm that the algorithm maintains excellent anti-interference capability and stable dynamic tracking performance even under complex magnetic environmental disturbances, while demonstrating good generalization across different hardware platforms and noise characteristics.

Complexity analysis indicates that the dual-mode correction strategy adopted in this study significantly reduces computational time compared to the standard ESKF algorithm while maintaining yaw angle estimation accuracy, showing potential for application in real-time embedded systems.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research received no specific grants from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Author Contributions: Yu Tao was responsible for the primary research execution, including algorithm development, implementation, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript. Yang Jie and Tian Yin contributed to the manuscript by providing revision suggestions. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lan J, Wang K, Song S, Li K, Liu C, He X, et al. Method for measuring non-stationary motion attitude based on MEMS-IMU array data fusion and adaptive filtering. Meas Sci Technol. 2024;35(8):086304. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad44c8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Candan B, Soken HE. Robust attitude estimation using magnetic and inertial sensors. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2023;56(2):4502–7. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2023.10.941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Narkhede P, Poddar S, Walambe R, Ghinea G, Kotecha K. Cascaded complementary filter architecture for sensor fusion in attitude estimation. Sensors. 1937 2021;21(6):1937. doi:10.3390/s21061937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kottath R, Narkhede P, Kumar V, Karar V, Poddar S. Multiple model adaptive complementary filter for attitude estimation. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2017;69(1):574–81. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2017.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mahony R, Hamel T, Pflimlin JM. Nonlinear complementary filters on the special orthogonal group. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 2008;53(5):1203–18. doi:10.1109/TAC.2008.923738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Madgwick SOH, Harrison AJL, Vaidyanathan R. Estimation of IMU and MARG orientation using a gradient descent algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Rehabilitation Robotics; 2011 Jun 29–Jul 1; Zurich, Switzerland. doi:10.1109/ICORR.2011.5975346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Narkhede P, Joseph Raj AN, Kumar V, Karar V, Poddar S. Least square estimation-based adaptive complimentary filter for attitude estimation. Trans Inst Meas Control. 2019;41(1):235–45. doi:10.1177/0142331218755234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Lu Y, Wang C, He Q. Double-complementary filter attitude estimator for decoupling magnetometer interference on pitch and roll. J Phys Conf Ser. 2025;3032(1):012019. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/3032/1/012019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sabatelli S, Galgani M, Fanucci L, Rocchi A. A double-stage Kalman filter for orientation tracking with an integrated processor in 9-D IMU. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2013;62(3):590–8. doi:10.1109/TIM.2012.2218692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bernal-Polo P, Martínez-Barberá H. Kalman filtering for attitude estimation with quaternions and concepts from manifold theory. Sensors. 2019;19(1):149. doi:10.3390/s19010149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Chen S, Hu F, Chen Z, Wu H. Correction method for UAV pose estimation with dynamic compensation and noise reduction using multi-sensor fusion. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(1):980–9. doi:10.1109/TCE.2023.3339729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Faraji J, Keighobadi J, Janabi-Sharifi F. Design and implementation of an adaptive extended Kalman filter with interval type-3 fuzzy set for an attitude and heading reference system. Signal Process. 2025;233(1):109947. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2025.109947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ren Z, Liu S, Dai J, Lv Y, Fan Y. Research on kinematic and static filtering of the ESKF based on INS/GNSS/UWB. Sensors. 2023;23(10):4735. doi:10.3390/s23104735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Luo J, Yin Z, Gui L. A GNSS UWB tight coupling and imu eskf algorithm for indoor and outdoor mixed scenario. Clust Comput. 2024;27(4):4855–65. doi:10.1007/s10586-023-04208-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Brigadnov I, Lutonin A, Bogdanova K. Error state extended Kalman filter localization for underground mining environments. Symmetry. 2023;15(2):344. doi:10.3390/sym15020344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Davari N, Gholami A, Shabani M. Multirate adaptive Kalman filter for marine integrated navigation system. J Navigation. 2017;70(3):628–47. doi:10.1017/s0373463316000801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen P, Li P, Ji B, Wang S, Song S, Yan T, et al. Integrated underwater navigation algorithm for AUV based on improved Sage-Husa and iterated maximum mixture correntropy unscented Kalman filter. Ocean Eng. 2025;341(14):122610. doi:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.122610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jiang W, Tan X. Low cost inertial sensor attitude fixation algorithm and accuracy analysis. Adv Space Res. 2023;72(6):2270–82. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2023.06.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Pang H, Pan M, Chen J, Li J, Zhang Q, Luo S. Integrated calibration and magnetic disturbance compensation of three-axis magnetometers. Measurement. 2016;93(6):409–13. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2016.06.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wei X, Fan S, Zhang Y, Gao W, Shen F, Ming X, et al. A robust adaptive error state Kalman filter for MEMS IMU attitude estimation under dynamic acceleration. Measurement. 2025;242:116097. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.116097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shi G, Li X, Jiang Z. An improved yaw estimation algorithm for land vehicles using MARG sensors. Sensors. 2018;18(10):3251. doi:10.3390/s18103251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Laidig D, Caruso M, Cereatti A, Seel T. BROAD—a benchmark for robust inertial orientation estimation. Data. 2021;6(7):72. doi:10.3390/data6070072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools