Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Attribute-Based Encryption for IoT Environments—A Critical Survey

Department of Computer Science, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 40506, USA

* Corresponding Author: Daskshnamoorthy Manivannan. Email:

Journal on Internet of Things 2025, 7, 71-97. https://doi.org/10.32604/jiot.2025.072809

Received 04 September 2025; Accepted 20 November 2025; Issue published 24 December 2025

Abstract

Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE) secures data by tying decryption rights to user attributes instead of identities, enabling fine-grained access control. However, many ABE schemes are unsuitable for Internet of Things (IoT) due to limited device resources. This paper critically surveys ABE schemes developed specifically for IoT over the past decade, examining their evolution, strengths, limitations, and access control capabilities. It provides insights into their security, effectiveness, and real-world applicability, highlights the current state of ABE in securing IoT data and access, and discusses remaining challenges and open issues.Keywords

As more sensitive data is shared and stored on third-party platforms, strong encryption is increasingly essential. Traditional encryption offers limited, coarse-grained access control–sharing data often means giving others full access via your private key. This lack of flexibility makes it hard to share specific information securely. Therefore, there’s a growing need for advanced encryption methods that enable fine-grained access control, allowing users to share only selected data without compromising everything.

Evolution of Attribute-Based Encryption

Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE) originated from Sahai and Waters [1], who introduced fuzzy identity-based encryption where identities were sets of attributes—the conceptual basis of ABE. Goyal et al. [2] and Bethencourt et al. [3] soon developed the first concrete models: Key-Policy ABE (KP-ABE) and Ciphertext-Policy ABE (CP-ABE), respectively, which are discussed below.

To eliminate single points of trust, Chase [4] proposed Multi-Authority ABE, later enhanced by Lewko and Waters [5] with decentralized trust and dual system encryption proofs. Green et al. [6] introduced outsourced decryption, allowing users to delegate most computation to the cloud without exposing plaintext. Rouselakis and Waters [7] developed large-universe ABE schemes supporting arbitrary attributes, with efficient implementations in Charm. Agrawal and Chase [8] achieved the first fully secure CP-ABE and KP-ABE under standard assumptions on Type-III pairings, outperforming prior schemes. Riepel and Wee [9] further optimized pairing-based ABE, enabling expressive, adaptive, and efficient constructions. Their schemes are demonstrated to perform better than the state-of-the-art (Bethencourt et al. [3], Agrawal and Chase [8] and Ambrona et al. [10]) on all parameters of interest.

More recently, lattice-based ABE schemes such as the one proposed by Hsieh et al. [11] have provided quantum-resistant security and richer predicate support. Overall, ABE has evolved from a conceptual idea into practical, scalable, and auditable systems featuring multi-authority trust, outsourced computation, hidden policies, efficiency gains, and post-quantum resilience—making it a cornerstone for fine-grained encrypted data access.

1.1 Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption (CP-ABE)

CP-ABE, introduced by Bethencourt et al. [3], enables fine-grained access control over encrypted data, even when storage servers are untrusted. CP-ABE resists collusion attacks, ensuring that users cannot collude to decrypt data unless their combined attributes meet the specified access policy. Unlike earlier ABE schemes, which embedded access policies in users’ keys, CP-ABE assigns attributes to users and lets the data owner define the access policy during encryption. This design aligns more closely with traditional access control models like Role-Based Access Control (RBAC). Bethencourt et al. [3] also provided a working implementation and evaluated its performance, demonstrating CP-ABE’s practicality for real-world, secure data sharing scenarios.

1.2 Key-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption (KP-ABE)

KP-ABE, introduced by Goyal et al. [2], enables fine-grained access control by encrypting data with a set of attributes and issuing users private keys tied to access structures. Unlike CP-ABE, where policies are embedded in ciphertexts, KP-ABE defines policies in the decryption keys. A key feature of KP-ABE is its support for hierarchical delegation of decryption rights. Inspired by Hierarchical Identity-Based Encryption (HIBE) [12,13], KP-ABE allows users to delegate subsets of their access privileges without contacting a central authority. This makes it ideal for scalable, layered access control systems that reflect real-world hierarchies, such as organizational roles or clearance levels. Only users whose access structures match the ciphertext’s attributes can decrypt the data, ensuring secure and flexible policy enforcement.

1.3 Attribute-Based Signature(ABS) Scheme

Attribute-Based Signature (ABS) [14,15] schemes, allow users to sign messages based on predicates over their attributes, issued by a trusted authority. Rather than verifying a signer’s identity, ABS verifies that the signer possesses attributes satisfying the predicate. ABS ensures unforgeability–even colluding users cannot produce valid signatures for attributes they don’t hold. At the same time, it preserves anonymity: valid signatures reveal nothing about the signer beyond the satisfied predicate. This makes ABS especially useful for privacy-preserving applications like anonymous credentials and fine-grained access control systems.

Organization of the Paper

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews related survey efforts and outlines the motivation and unique contributions of the present work. Section 3 provides a critical review of existing research on attribute-based encryption and access control mechanisms proposed for the Internet of Things, with a focus on developments over the past decade. In Section 4, we highlight and analyze the key open challenges and unresolved issues in this domain. Finally, Section 5 offers concluding remarks and directions for future research.

In this section, we discuss the recent related surveys in this area and also justify need for our survey.

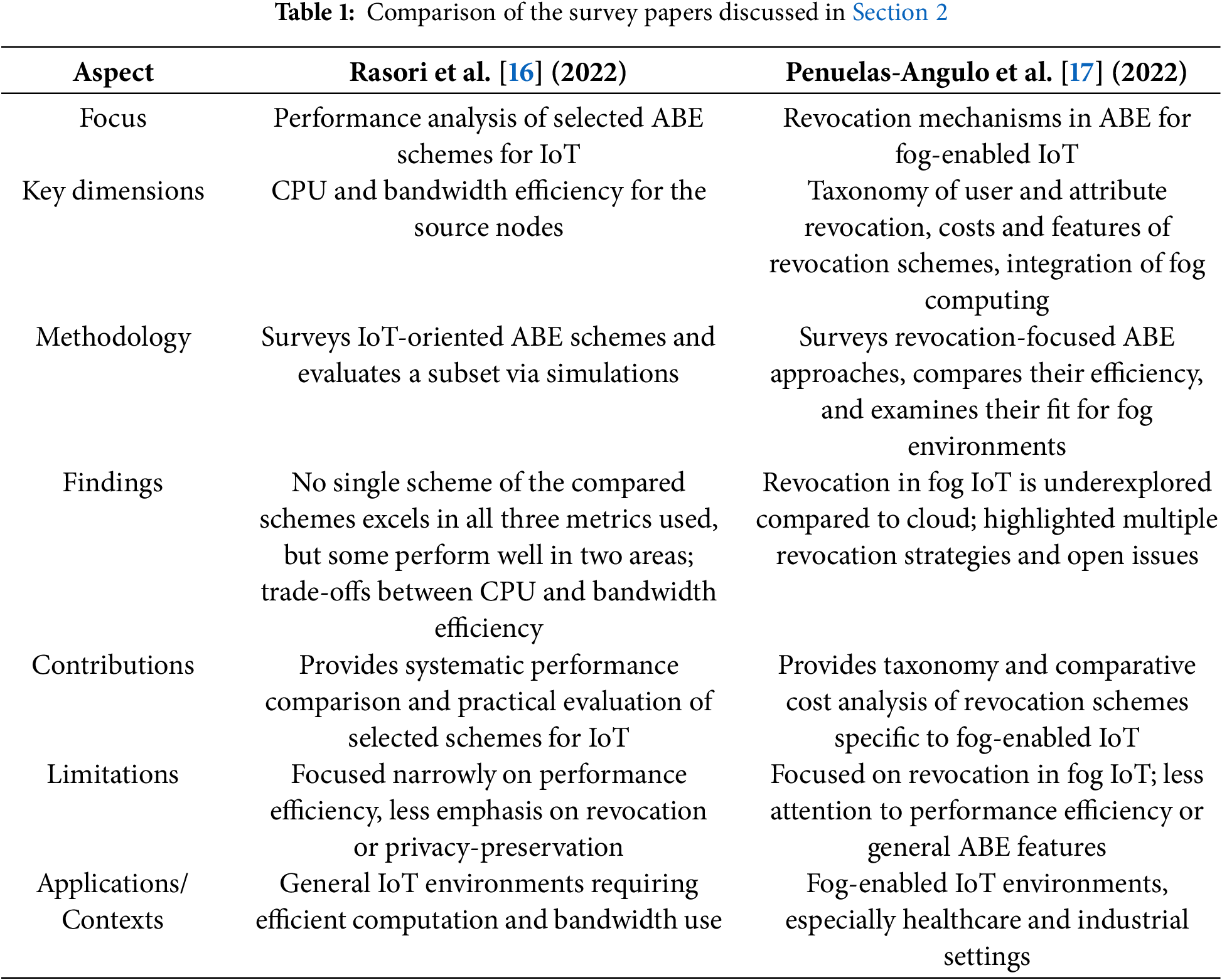

Rasori et al. [16] survey ABE schemes tailored for IoT applications by focusing on three key performance indicators: CPU efficiency at the data producer, bandwidth efficiency at the data producer, and bandwidth efficiency at the key authority. They analyze only those schemes that show promise in one or more of these areas. Additionally, they evaluate a selected subset through simulations, revealing that while no single scheme excels in all three metrics, some perform well across two.

Penuelas-Angulo et al. [17] survey attribute-based encryption (ABE) revocation schemes specifically for fog-enabled IoT, a domain less explored compared to cloud-based IoT scenarios. Recognizing the unique constraints of fog environments—common in healthcare and industrial applications—they present a taxonomy of user and attribute revocation methods. The study also examines how fog computing is utilized in these schemes, compares their costs and features, and highlights current challenges and future opportunities for enhancing revocable ABE in fog-based IoT systems.

Table 1 presents a comparison of the above survey papers discussed in this section.

Justification for Our Survey

The need for this survey arises from the recent surge of research on ABE and ABAC tailored to IoT, most of which has appeared only within the last three years. Prior to this period, work in this domain was relatively limited, reflecting the fact that the unique security and access control challenges of IoT environments have only recently attracted significant research attention.

While Rasori et al.’s [16] and Penuelas-Angulo et al.’s [17] surveys have offered insights into specific aspects–for example, Rasori et al.’s on performance trade-offs and Penuelas-Angulo et al.’s on revocation in fog-enabled IoT–they remain narrow in scope, each emphasizing a subset of issues. Our survey extends beyond these works by consolidating, systematizing, and critically analyzing a broader set of contributions. In doing so, it highlights open issues such as scalability, efficiency, revocation, and privacy-preservation, while also pointing toward promising directions for future exploration.

Out survey complements and extends both these surveys by:

(i) Consolidating and critically analyzing recent IoT-ABE and ABAC works across efficiency, revocation, scalability, and privacy dimensions. Highlighting open issues and research gaps overlooked in earlier surveys (e.g., dynamic attribute updates, usability, integration into real IoT ecosystems).

(ii) Providing a timely resource that captures the momentum of this emerging research area and guiding future directions in designing secure, efficient, and scalable access control solutions for IoT systems.

(iii) Including and discussing most recently published papers in this area.

3 Research Works on Attribute-Based Encryption and Access Control for IoT Environments

With the rapid proliferation of the Internet of Things (IoT), the number of interconnected sensors and smart devices has increased dramatically, leading to the generation of vast volumes of data. A significant portion of this data is sensitive, encompassing information such as personal identifiers, location traces, healthcare records, and industrial metrics. The large-scale and distributed nature of data collection in IoT environments introduces substantial security and privacy challenges, particularly in ensuring that only authorized entities can access sensitive information. To address these challenges, ABE has emerged as a promising solution for fine-grained access control in IoT systems. By allowing access policies to be defined over descriptive attributes, ABE offers greater flexibility and scalability than traditional identity-based approaches. This section presents an overview of ABE schemes proposed for IoT in the literature over the past decade.

We categorize the existing research contributions in the domain of Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE) for IoT into distinct classes based on their core design principles, system architectures, and targeted application scenarios. This classification facilitates a structured understanding of the diverse approaches adopted in the literature and highlights the key features, objectives, and trade-offs associated with each category. We present and analyze representative works within each class to illustrate the evolution and current state of research in this area. It is important to note that this classification is not rigid, as some studies may span multiple categories due to overlapping design goals or hybrid approaches.

Criteria Used for Selecting Papers

To ensure that our literature review is both comprehensive and of the highest scholarly quality, we adopted a systematic and rigorous paper selection methodology. Research articles were primarily gathered primarily from leading peer-reviewed journals and and some top-tier international conferences that are widely recognized for their stringent review processes, academic credibility, and substantial contributions to the fields of computer science, cybersecurity, and information security. In particular, we relied extensively on reputable publishers such as IEEE, ACM, Elsevier, and Springer, all of which consistently uphold high standards of editorial excellence and technical depth. Conversely, publications originating from relatively low-impact venues were deliberately excluded to maintain the integrity and reliability of the surveyed body of work.

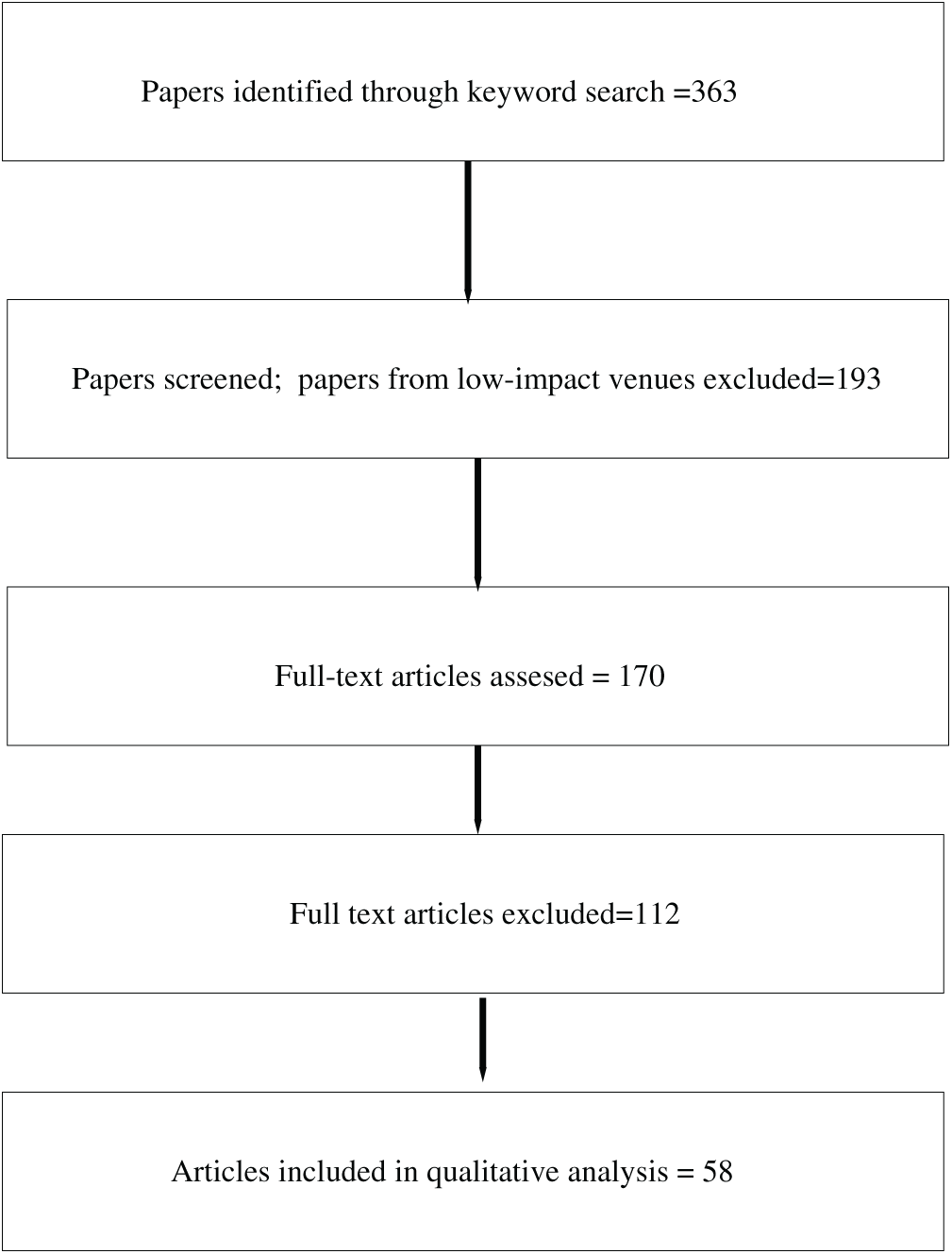

To identify relevant literature, we conducted searches using Google Scholar and journal publisher websites with keywords including “attribute-based encryption” and “IoT.” This process initially yielded a total of 363 research papers. We then performed a preliminary screening based on title, abstract, and venue quality, resulting in the exclusion of 193 papers associated with lower-impact outlets. The remaining 170 papers were subjected to full-text analysis. During this eligibility assessment, 112 papers were removed because they were not IoT-related, were not primarily focused on ABE, or lacked sufficient technical depth. Ultimately, 58 high-quality papers were selected for inclusion in this survey.

The resulting collection of literature provides an authoritative, well-validated foundation for analyzing the evolution, challenges, and applicability of ABE schemes within IoT environments. In addition to serving as the basis of this work, it also offers a valuable reference point for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers seeking to understand current trends, identify research gaps, and design more secure and scalable access control solutions for next-generation IoT systems. A PRISMA-style diagram summarizing the inclusion and exclusion criteria used during the selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: PRISMA-style diagram representing the inclusion/exclusion criteria for selecting the papers

3.1 Research Works Based on CP-ABE and KP-ABE

In IoT environments, CP-ABE and KP-ABE have emerged as two widely adopted variants of ABE for achieving fine-grained access control. CP-ABE is often favored in IoT applications because it allows data owners, such as sensors or smart devices, to embed access policies directly into the ciphertext. This ensures that only users with matching attributes can decrypt the data, which is particularly useful for resource-constrained devices that need to enforce flexible access policies without relying on a central authority at query time. By contrast, KP-ABE assigns policies to users’ private keys, making it suitable in scenarios where the data producers are lightweight and cannot afford the computational burden of policy embedding. In IoT deployments, KP-ABE is often used when data producers only need to encrypt with attribute sets, leaving the policy enforcement to the authority that issues keys. Both schemes support fine-grained, scalable, and decentralized access control, but they also face challenges such as computational overhead, dynamic attribute management, and revocation. Consequently, CP-ABE and KP-ABE serve as foundational cryptographic tools in securing IoT ecosystems, each offering distinct advantages depending on the balance between data owner control and system efficiency. In this subsection, we discus the CP-ABE and KP-ABE based schemes designed for IoT environment.

Han et al. [18] introduced an innovative CP-ABE scheme tailored specifically for IoT environments. This scheme effectively addresses a crucial privacy concern by safeguarding users’ attribute values from the attribute authority using a 1-out-of-n oblivious transfer technique. This approach ensures that the attribute authority, which is responsible for granting access rights, is unable to ascertain specific attribute values during the decryption process, thereby significantly enhancing user privacy. In addition to this protective measure, the scheme employs an Attribute Bloom Filter designed to protect the types of attributes utilized within the access policy embedded in the ciphertext. This additional mechanism provides an extra layer of security by preventing unauthorized entities from inferring sensitive information related to the attributes that govern access control policies. Comprehensive security and performance evaluations of the scheme demonstrate its effectiveness in meeting essential security objectives, including the maintenance of data confidentiality and user privacy. Furthermore, the computational overhead associated with the proposed scheme remains comparable to that of existing solutions, making it a practical option for resource-constrained IoT devices. This careful balance between security and efficiency underscores the scheme’s suitability for IoT applications, where both performance and privacy are of paramount importance.

Zhang and Zhou [19] introduce an IND-CCA-secure multi-authority ciphertext-policy ABE (MA-CP-ABE) scheme that incorporates outsourced decryption and a progressive attribute-based authentication (ABAuthen) system. This approach employs zero-knowledge proof to safeguard user secrets and guard against impersonation attacks through randomized authentication messages. Analytical and performance evaluations demonstrate that this encryption and authentication scheme is both efficient and suitable for distributed IoT-assisted cloud computing.

Fog computing’s ability to reduce data transfer requirements and latency is increasingly favored for applications demanding secure, fine-grained access control. CP-ABE is well-suited for fog-enabled IoT applications; however, conventional CP-ABE faces challenges regarding effective access revocation. Zhao et al. [20] address this with an efficient CP-ABE scheme called AC-FEH, designed specifically for fog-based E-health systems. This scheme delegates encryption and decryption tasks to fog nodes, significantly alleviating computational burdens on users. Proven selectively secure based on the q-parallel BDHE problem, AC-FEH achieves lower computational costs than competing CP-ABE-based access control systems.

To ensure data privacy, IoT data in the cloud needs to be encrypted and made accessible solely to authorized entities. Li et al. [21] propose a CP-ABE scheme that delivers fine-grained access control over encrypted IoT data in the cloud, making it particularly well-suited for secure cloud-based IoT systems. They introduce an access control model tailored for a Cloud-IoT platform using ABE, developing a ciphertext-policy hiding CP-ABE scheme designed to protect user privacy. To guard against user and authorization key misuse, they also design a white-box traceable CP-ABE scheme that provides accountability. Experimental results confirm the scheme’s efficiency.

Huang et al. [22] propose RS-CPABE-ASP, a revocable storage CP-ABE scheme leveraging arithmetic span programs to reduce policy definition overhead. It integrates indirect revocation and ciphertext updates to block access by revoked users. The outsourced decryption version shifts heavy computation to the cloud, requiring only a single exponentiation by users. Security analysis and simulations confirm its efficiency for cloud-assisted IoT.

Mehla et al. [23] integrate blockchain with IoT to protect attribute privacy in CP-ABE schemes for cloud-IoT. Their design encrypts attribute information, preventing leakage at both owner and user ends. Using ElGamal’s homomorphic property, the system verifies authorized users privately while enabling secure data sharing and access control. Tan et al. [24] enhance a lightweight KP-ABE scheme for IoT by fixing a flaw that allowed unauthorized decryption under certain policies. They further extend the design into a hierarchical KP-ABE (H-KP-ABE) that supports role delegation, demonstrating its usefulness in IoT-based healthcare scenarios. Benchmarks on Android devices using NIST curves (secp192k1, secp256k1) show the scheme remains the fastest among existing solutions.

3.2 Research Works Based on Hierarchical and Centralized ABE

In IoT environments, hierarchical and centralized ABE schemes offer the advantage of simplified key management and policy enforcement, since a single trusted authority is responsible for generating keys, distributing attributes, and enforcing access control. This hierarchical or centralized structure reduces system complexity and makes deployment straightforward, which can be beneficial for small to medium-scale IoT networks where administrative overhead must be minimized. However, the same centralization also introduces significant disadvantages. The single point of trust creates a vulnerability: if the authority is compromised, the entire system’s confidentiality and integrity are at risk. Moreover, hierarchical or centralized schemes often struggle to scale in large IoT deployments due to the high demand on the authority for key issuance, attribute updates, and revocation management. This bottleneck leads to performance degradation, latency, and limited adaptability in dynamic IoT environments. Thus, while hierarchical or centralized ABE schemes provide ease of management, their lack of scalability, resilience, and robustness makes them less suitable for large, distributed IoT ecosystems where decentralization and fault tolerance are critical. In this subsection, we discuss the research works based on hierarchical and centralized ABE.

3.2.1 Blockchain- and Edge-Assisted ABE for Decentralized Trust and Privacy Preservation

A growing body of work focuses on integrating blockchain and decentralized computing infrastructures into ABE-based IoT architectures. Sasikumar et al. [25] propose a decentralized hierarchical attribute-based encryption (HABE) scheme that integrates edge computing with blockchain technology to enable IoT devices to securely transmit data to nearby cloud networks while preserving user privacy. Their approach leverages encryption-based authentication executed at the network edge to verify user access in a decentralized manner and is particularly well-suited to privacy-preserving IoT applications in smart logistics. By combining HABE with edge-cloud infrastructure, the architecture provides improved responsiveness and autonomy while delivering 1.5 times faster authentication performance than centralized systems. Experimental evaluations further demonstrate superior data-sharing throughput, confidentiality, and resistance to privacy leakage compared to existing methods.

Addressing a long-standing key escrow concern associated with traditional ABE schemes, Guo et al. [26] propose a revocable blockchain-aided ABE system with escrow-free (BC-ABE-EF), which replaces the traditional trusted key authority with a consortium blockchain. In this configuration, key generation is jointly performed by blockchain nodes and users so that no party possesses the full private key. A decryption cloud server handles pre-decryption operations, significantly reducing computational load on IoT devices, while a group manager updates keys and coordinates re-encryption processes. Security claims are substantiated under the Decisional Composite Diffie-Hellman (DCDH) assumption, and simulation results demonstrate high efficiency and practical viability in distributed IoT ecosystems.

Expanding the role of blockchain into secure storage, Zhang et al. [27] introduce StorSec, a security framework for distributed IoT storage built on the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS). StorSec integrates an enhanced ABE algorithm for fine-grained access control, a hashchain-based anomaly detection mechanism to ensure data integrity, and a blockchain-based auditing process to track malicious activity. Experimental results and security analyses validate the framework’s effectiveness, performance, and ability to deter attacks. Collectively, these works illustrate a critical research trajectory in which blockchain decentralizes trust, strengthens auditability, and removes single points of failure when designing privacy-preserving IoT access-control infrastructures.

3.2.2 Outsourced and Proxy-Based Computation for Overcoming Resource Constraints

Resource limitations on IoT devices frequently motivate outsourcing-based enhancements to ABE. Li et al. [28] present an efficient attribute-based encryption outsourcing scheme specifically designed for fog-enabled IoT environments, incorporating both user and attribute revocation. Their system improves encryption efficiency by employing attribute groups for revocation and by delegating computationally expensive encryption and decryption operations to fog nodes that also manage portions of the secret keys. Security is rigorously validated under the DBDH assumption, and performance results show high practicality for fog computing contexts, particularly in scenarios where frequent ciphertext updates are required.

Similarly, Zheng et al. [29] propose a secure and efficient IoT data-sharing model based on revocable ABE, where cloud assistance alleviates resource limitations. The approach incorporates fine-grained access control and user revocation mechanisms, and experimental results support its effectiveness for secure data sharing and user lifecycle management.

Hao et al. [30] extend the concept into cloud-assisted IoMT by proposing a secure and fine-grained data-sharing scheme that combines ABE with proxy re-encryption and key blinding techniques. Their approach enables cloud servers to efficiently re-encrypt ciphertexts affected by revocation while updating keys for authorized users and adding new attributes to extend privileges without reissuing keys. Security proofs and performance evaluations verify both efficiency and strong access-control properties.

Taha et al. [31] further reduce cryptographic overhead by introducing an ABE framework that offloads expensive encryption and decryption tasks to proxy servers while preserving privacy and integrity. Their performance evaluation–considering execution time, ciphertext size, and memory usage–shows that the proposed scheme outperforms existing approaches, providing improved practicality for real-world IoT deployments.

To support constrained medical devices, Zhang et al. [32] incorporate outsourced encryption and decryption into an efficient attribute-based data-sharing scheme for IoMT that hides sensitive attribute values, supports dynamic policy updates, and includes a user revocation mechanism that mitigates collusion between revoked users, non-revoked users, and cloud service providers. Formal proofs demonstrate full security—considered stronger than most competing schemes—and simulation results validate its efficiency, scalability, and privacy-preserving properties. Taken together, these works demonstrate that outsourcing, proxy re-encryption, and blinding techniques are now central strategies for accommodating the severe computational limitations of IoT devices.

3.2.3 Revocable, Unbounded, and Adaptively Secure ABE Constructions

Efficient revocation remains one of the most difficult challenges in ABE for IoT. Xiong et al. [33] propose an unbounded, efficient, revocable ABE scheme that provides adaptive security under the standard decision linear assumption. By eliminating predefined system parameters and employing a monotonic span program (MSP) to encode access policies, the scheme reduces computational overhead associated with bilinear pairing and exponentiation operations, improving key generation and decryption performance. Empirical evaluations confirm both feasibility and effectiveness.

Building on this direction, Xiong et al. [34] extend ABE into digital twin environments by employing arithmetic span programming (ASP) as a more expressive generalization of MSPs. ASP operates on arithmetic circuits and is particularly relevant to zero-knowledge proofs and secure computation. Their unbounded construction eliminates predefined parameters and satisfies adaptive security under the Matrix Decisional Diffie-Hellman (MDDH) assumption. Empirical performance testing confirms practicality, scalability, and efficiency in cloud-assisted DT environments.

To defend against coercion threats in IoMT, Zhai et al. [35] design CR2-ABE, a coercion-resistant scheme combining chameleon hashing, deniable encryption, and CP-ABE. Blockchain ensures integrity, and secure enclaves based on Intel SGX enable ciphertext policy revocation. Formal analysis demonstrates resilience against coercion, and performance measurements show efficiency in key generation, encryption, decryption, and revocation.

Addressing attribute revocation in the Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT), Li et al. [36] develop EPREAR, an efficient attribute-based proxy re-encryption scheme with fast attribute revocation verified using blockchain-based non-interactive zero-knowledge proofs. It supports boundless encryption/decryption with constant computation cost and allows unlimited attribute expansion without reinitialization. Analytical comparisons highlight improved scalability and performance for AIoT environments. These contributions collectively advance the practical deployment of scalable, revocable, and adaptively secure ABE systems in complex IoT ecosystems.

3.2.4 ABE in IoMT and Healthcare Data Sharing

Healthcare environments require strict privacy guarantees and fine-grained access control for patient data. Zeng et al. [37] introduce PTIoMT, an efficient ABE scheme with partially hidden access policies that conceal sensitive attribute labels, provide public traceability to detect key misuse, and support scalability by accommodating unlimited attributes. By reducing the number of bilinear pairing operations during decryption, PTIoMT improves efficiency in real-world IoMT deployments. Comprehensive security and performance analyses substantiate its effectiveness.

Zhang et al. [32] contribute a scheme that supports dynamic policy updates, user revocation, outsourced computation, and fine-grained privacy protection through the separation of attribute names and values. Bagchi et al. [38] introduce a Ring-LWE-based multi-authority CP-ABE scheme resistant to quantum attacks, employing Shamir’s secret sharing and Lagrange interpolation to simplify key management while supporting blockchain-based storage for smart healthcare. Comparative analysis shows superior efficiency and robustness, demonstrating the importance of post-quantum security in future healthcare deployments. Together, these works illustrate how ABE continues to evolve to address evolving regulatory and ethical data-sharing requirements in the medical domain.

3.2.5 ABE in Intelligent Transportation and Industrial Environments

Smart cities and industrial IoT environments introduce unique security challenges due to the potential consequences of unauthorized actuator control. Gupta et al. [39] develop ITS-ABAC-G, an attribute-based access control system for the Industrial Internet of Vehicles (IIoV), grouping smart entities based on attributes to enable fine-grained security policies aligned with user privacy preferences and overarching system policies. Their prototype implementation on Amazon Web Services IoT validates its practicality.

He et al. [40] present a fine-grained access-control scheme tailored for identity resolution and Prognostics and Health Management (PHM) systems. By combining unique identifier encoding with ABE, the system enables dynamic data categorization and permission control suited to industrial environments. Blockchain is integrated to trace malicious activity while preserving user privacy, and formal security verification under the decisional bilinear Diffie-Hellman (DBDH) assumption confirms scheme soundness. Experimental comparisons show improvements in computation time and storage efficiency.

Lu et al. [41] propose a lightweight encryption method for IIoT based on the subset-sum problem, supporting multi-entity data sharing with ABE-based key forwarding and revocation through device key updates. The lightweight design meets the resource constraints of IIoT devices while maintaining strong security guarantees for data streams. These solutions demonstrate how ABE can be tailored to industrial workloads that prioritize safety, low latency, and hardware efficiency.

3.2.6 Feasibility Evaluations and Benchmark Optimization

To evaluate the feasibility of deploying ABE on constrained hardware, Perazzo et al. [42] assess three representative ABE schemes on IoT platforms such as ESP32 and RE-Mote. Their analysis shows that, with hardware acceleration and policies containing at most 10 attributes, ABE can operate within acceptable energy consumption limit. They also propose an improved benchmarking methodology demonstrating that worst-case assumptions used in prior literature tend to significantly overestimate computation time and power usage. These findings underscore the importance of realistic performance modeling rather than relying exclusively on theoretical upper bounds.

3.2.7 Summary and Emerging Trends

Across these grouped themes, recent research reveals several converging trends in ABE-based IoT security. Blockchain increasingly serves as a decentralized trust anchor to eliminate key-authority single points of failure, support auditability, and strengthen accountability. Outsourced encryption, proxy re-encryption, and key blinding address computational and energy constraints for resource-limited devices. New revocation models support unbounded attribute sets, flexible privilege updates, and adaptive security properties without predefined parameters. Policy-hiding mechanisms protect user identities in privacy-sensitive applications such as IoMT. Lightweight and post-quantum constructions anticipate both hardware constraints and future cryptographic threats. Finally, feasibility studies demonstrate that practical deployment is increasingly viable when optimized configurations and accelerators are applied.

Collectively, these efforts mark significant progress toward securing diverse IoT environments with fine-grained, privacy-preserving, scalable, and practically deployable access-control mechanisms grounded in Attribute-Based Encryption.

3.3 Research Works Based on Multi-Authority ABE

In IoT settings, Multi-Authority Attribute-Based Encryption (MA-ABE) addresses many of the limitations of centralized schemes by distributing trust and key management across multiple independent authorities. This distribution improves scalability, since different authorities can manage attributes within their domains, thereby reducing the computational and communication load on any single entity. Moreover, MA-ABE provides fine-grained and flexible access control, as users can obtain attributes from multiple authorities that collectively determine their decryption capabilities. This aligns well with heterogeneous IoT ecosystems, where devices and users often span multiple administrative domains.

However, MA-ABE also presents notable disadvantages. Coordination among multiple authorities introduces complexity in system design and communication overhead, which can be problematic in resource-constrained IoT environments. Ensuring collusion resistance—so that users cannot combine attributes from different authorities to gain unauthorized access—remains a critical challenge. Additionally, issues such as synchronization, policy conflicts, and attribute revocation become more difficult to manage when multiple authorities are involved. The need for secure communication channels between authorities further increases system overhead. Thus, while MA-ABE enhances security, scalability, and domain autonomy in IoT, it also introduces management complexity and efficiency concerns, requiring careful design trade-offs to balance practicality with robustness. In this subsection, we discuss the research works on Multi-authority ABE schemes for IoT.

Belguitha et al. [43] propose PHOABE, a Policy-Hidden Outsourced Attribute-Based Encryption scheme designed to address critical challenges in secure data sharing across IoT and cloud platforms. PHOABE enables multiple attribute authorities to manage distinct attribute sets, offering flexible and decentralized access control, while shielding access policies from both unauthorized users and the cloud server. To reduce the heavy computational overhead associated with decryption on resource-limited devices, a substantial portion of the decryption process is outsourced to a semi-trusted cloud server. PHOABE further provides verifiability to ensure the correctness of outsourced computations and demonstrates selective security under the random oracle model. Performance evaluations confirm that PHOABE’s processing overhead remains practical for IoT deployments.

Motivated by privacy concerns in IoT-driven smart oceans, Yu et al. [44] introduce a privacy protection scheme for crowdsourced marine data that employs multi-authority ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption. The use of multiple attribute authorities decentralizes security responsibilities, preventing dependence on a single platform. Their design incorporates partial decryption to reduce computational burden on end users, while ensuring that the platform cannot access the plaintext data. The framework also supports efficient attribute revocation and a keyword-search mechanism that enables dynamic, on-demand task querying. Forward and backward security properties further protect against unauthorized access resulting from attribute changes. Simulation results demonstrate improved decryption and keyword-matching performance, highlighting the suitability of multi-authority approaches for complex, multi-role IoT data-sharing scenarios.

In fog computing environments, which operate between cloud data centers and end-users, traditional ABE often incurs high latency and significant computational cost. To address these limitations, Tu et al. [45] propose a multi-authority ABE (MA-ABE) scheme that supports dynamic attribute revocation and computation outsourcing to fog servers. Their approach allows secret keys to be updated immediately upon revocation and offloads complex encryption tasks to fog nodes, thereby improving system responsiveness and reducing computational demand on constrained IoT devices. Comparative evaluations indicate clear efficiency advantages over existing solutions.

Enhancing this direction, Huang [46] introduces the first revocable, large-universe, decentralized MA-ABE scheme resistant to key abuse. Constructed over prime-order bilinear groups, the scheme supports dynamic expansion of users, attributes, and authorities while preventing malicious actors from generating unauthorized keys. Efficient attribute revocation minimizes decryption overhead and enables scalability. Security under the q-DPBDHE2 assumption confirms robustness against advanced adversarial capabilities, making the scheme particularly well-suited for distributed IoT deployments that require flexible trust boundaries.

Focusing on healthcare, Wang et al. [47] propose EAPDS, an Efficient and Auditable Privacy-preserving Data Sharing scheme tailored for the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT). Built upon a multi-authority ABE model, EAPDS introduces an auditable anonymous authentication mechanism to protect user identity privacy and prevent unauthorized tracking. Its optimized MA-ABE construction supports secure, scalable data sharing among diverse medical entities, while formal security analysis demonstrates resistance to replayable chosen-ciphertext attacks–critical for safeguarding sensitive medical information. Comprehensive experimental evaluation shows that EAPDS outperforms existing medical data-sharing methods in efficiency, privacy preservation, and practical usability, positioning it as a strong candidate for real-world IoMT deployments.

Overall, these advances reflect an ongoing trend toward decentralized authority management, outsourced computation, verifiable security, and privacy-aware policy handling, providing promising pathways for secure and efficient data sharing across heterogeneous IoT domains.

3.4 Research Works That Support Searchable Encryption

In IoT environments, searchable encryption (SE) provides a powerful mechanism for enabling keyword-based or attribute-based queries over encrypted data without revealing the plaintext to untrusted servers. Its main advantage lies in preserving data confidentiality while maintaining efficient searchability, which is crucial for resource-constrained IoT devices that generate large volumes of sensitive data such as medical records, sensor readings, or industrial logs. SE methods allow users or applications to perform secure data retrieval without exposing contents to cloud or edge servers, thereby supporting fine-grained access control, reduced data leakage, and privacy-preserving analytics. However, SE also comes with several disadvantages. Most schemes incur computational and communication overhead, which may not be well-suited to low-power IoT devices. Many SE designs risk information leakage through search patterns, access patterns, or frequency analysis, raising privacy concerns. Additionally, managing dynamic updates, revocation, and scalability remains challenging, especially in distributed IoT ecosystems with heterogeneous devices and frequent attribute changes. Thus, while searchable encryption enhances privacy and secure data usability, its efficiency, leakage resilience, and revocation support remain active research challenges for practical IoT deployment. In this subsection, we discuss the schemes based on searchable encryption for IoT.

Bao et al. [48] propose a lightweight attribute-based searchable encryption (LABSE) scheme that combines fine-grained access control with keyword search functionality while maintaining low computational overhead for resource-constrained devices. Their rigorous semantic security proofs, supported by experimental comparisons, demonstrate that LABSE outperforms existing approaches in efficiency and practicality.

Building on the need for scalable search capabilities, Yan and Zhang [49] introduce an efficient attribute-based multi-keyword searchable encryption scheme that conceals access policies using blockchain. The design incorporates an attribute Bloom filter, which filters unauthorized queries early to reduce bilinear pairing operations and enhance search performance. Valid search requests are processed by the cloud for attribute verification, while encrypted data is stored through the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) to support scalable, distributed storage. Blockchain further secures the system by providing immutable, traceable search records. Security and performance evaluations confirm the practicality of this approach for real-world IoT deployments.

Focusing on dynamic policy management, Li et al. [50] present an efficient attribute-based searchable proxy re-encryption scheme that supports policy hiding for IoT data sharing. Their system integrates symmetric encryption for data confidentiality with ABE to protect encryption keys, enabling dynamic policy updates through proxy re-encryption without requiring bulk data to be re-encrypted. An AND-gate access model supports multi-valued attributes while ensuring policy privacy and constant-size overhead. Formal security analysis and performance results verify its feasibility for flexible IoT access control scenarios.

Targeting healthcare-driven IoT environments, Ma et al. [51] develop PC-SE, a privacy-preserving conjunctive searchable encryption scheme based on attribute-value databases for cloud-IoT healthcare systems. PC-SE enables flexible, fine-grained keyword and attribute searches while providing forward and backward privacy, thereby preventing inference from past or revoked queries. Its integration of attribute-based access control restricts unauthorized data retrieval, and both security proofs and experimental evaluations demonstrate strong privacy guarantees and efficient performance. These approaches reflect ongoing advancements toward lightweight, privacy-preserving, and dynamically adaptable searchable encryption solutions tailored for diverse and resource-constrained IoT environments.

3.5 Research Works on Attribute-Based Signature Schemes

In IoT environments, Attribute-Based Signature (ABS) schemes play an important role in providing authentication and accountability while preserving privacy. Unlike traditional signatures that directly bind a signer’s identity to a message, ABS allows a user to sign a message based on a set of attributes (e.g., device type, role, or location) rather than their unique identity. This offers several advantages: it enables fine-grained authentication, ensuring that only entities with appropriate attributes can generate valid signatures; it provides privacy-preserving guarantees by hiding the actual signer’s identity while still proving membership in an authorized group; and it enhances accountability and trust in IoT applications such as smart healthcare, vehicular networks, and industrial IoT. However, ABS schemes also face notable disadvantages. Efficient revocation of attributes or users remains a challenge, as compromised devices or expired attributes may still produce valid signatures if not handled properly. Furthermore, designing ABS schemes that are collusion-resistant, scalable, and lightweight enough for large, heterogeneous IoT systems continues to be a difficult task. Thus, while ABS schemes strengthen privacy and trust in IoT, their efficiency, revocation support, and practical deployment remain open research challenges. In this subsection, we discuss the works based on ABS proposed for IoT.

To advance the capability of ABS, Yuen et al. [52] introduce the forward-secure ABS model and provide a generic construction leveraging well-established cryptographic primitives. Building on the need for efficient authentication in resource-constrained settings, Yu et al. [53] propose the Lightweight Hybrid Policy Attribute-Based Signcryption (LH-ABSC) scheme, which integrates ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption (CPABE) with key-policy attribute-based signatures (KPABS). In this design, CPABE enables data owners to control who may decrypt the encrypted content, while KPABS ties the signature to the owner’s attribute set, ensuring authenticity. Notably, LH-ABSC maintains a constant signature size, a crucial benefit for IoT applications where public verification is required. The scheme also offloads most of the computationally intensive operations—signing, verification, and decryption—to fog nodes, thereby optimizing resource utilization. It achieves a comprehensive security profile, including confidentiality, unforgeability, verifiability, selective chosen-ciphertext security, selective chosen-message security, and signer anonymity, making it well-suited for secure data sharing in distributed IoT ecosystems.

Addressing the limitations of existing server-aided ABS (SA-ABS) schemes in industrial IoT deployments, Xiong et al. [54] present a novel SA-ABS protocol that mitigates vulnerability to collusion attacks and supports expressive linear secret-sharing scheme (LSSS) access structures. Their protocol offloads intensive operations such as signature generation and verification to a third-party server, while rigorous proofs in the standard model demonstrate its unforgeability. Both theoretical analysis and simulation results confirm its feasibility and efficiency, highlighting its suitability for IIoT environments where complex policy enforcement is necessary.

To eliminate dependence on centralized control and reduce computational overhead, Li et al. [55] propose a decentralized attribute-based server-aided signature (DABSAS) scheme. In this approach, a server provides computational assistance for signature generation and verification, enabling anonymity and unforgeability while avoiding reliance on a central authority that could become a single point of failure. The scheme is proven secure under the co-Diffi—Hellman assumption and demonstrates improved efficiency compared to traditional multi-authority solutions, particularly for resource-limited IoT devices.

Further improving efficiency, Chen et al. [56] introduce a pairing-free attribute-based signature scheme with message recovery for IIoT environments. By leveraging linear secret sharing for flexible policy definition and basing security on the hardness of the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem, their design achieves unforgeability and anonymity under chosen-policy security. The scheme removes the need to transmit signed messages explicitly and demonstrates superior performance when compared to pairing-based ABS constructions.

These works demonstrate a clear evolution in attribute-based signature design: from forward-secure constructs and hybrid signcryption models, to server-assisted and decentralized frameworks, and finally to pairing-free optimizations. These advancements collectively support scalable, flexible, and privacy-preserving authentication mechanisms tailored to the computational constraints and security demands of modern IoT and IIoT systems.

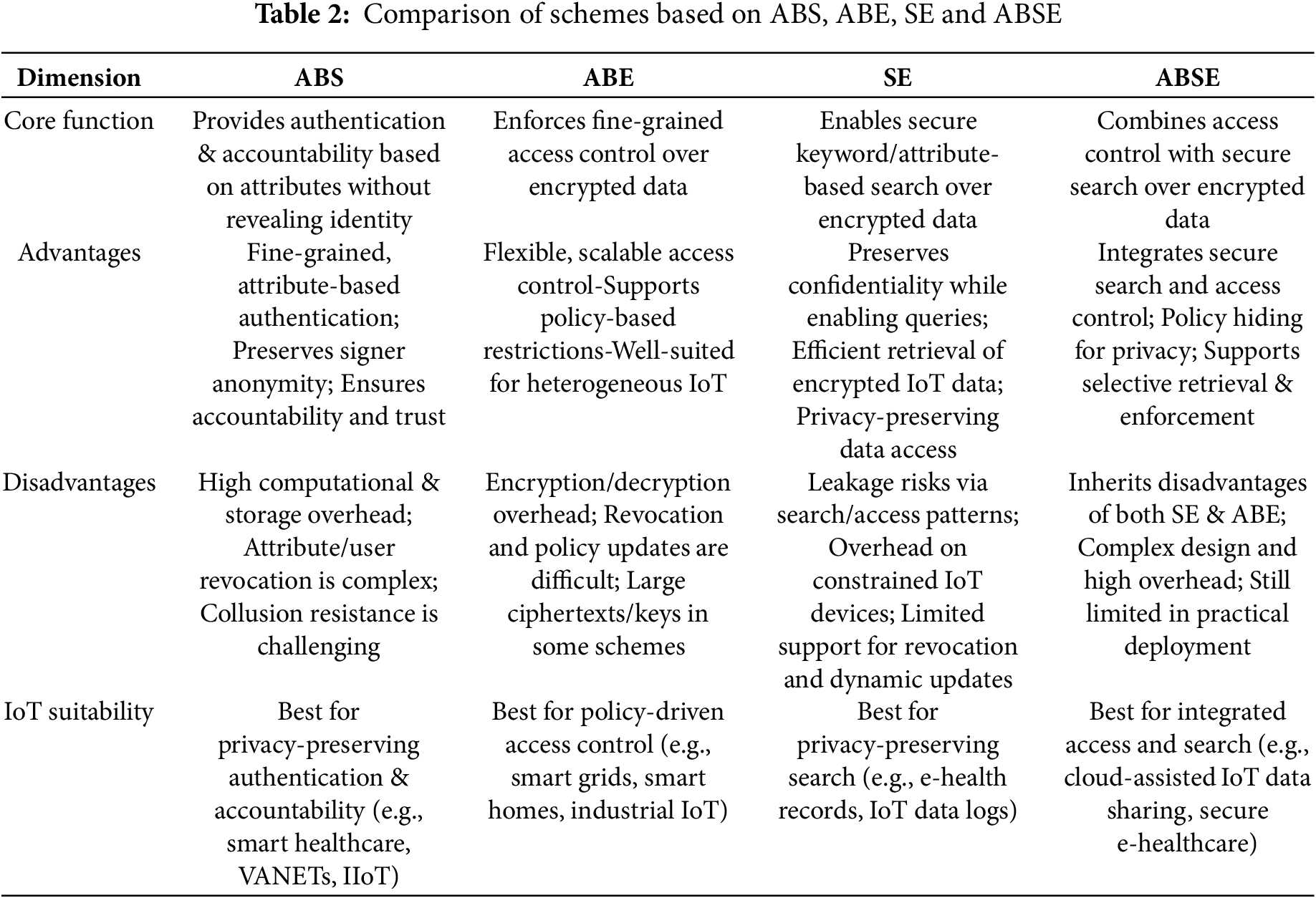

Table 2 provides a summary of the advantages and disadvantages and suitability for IoT of the schemes based on ABS, ABE, SE and ABSE.

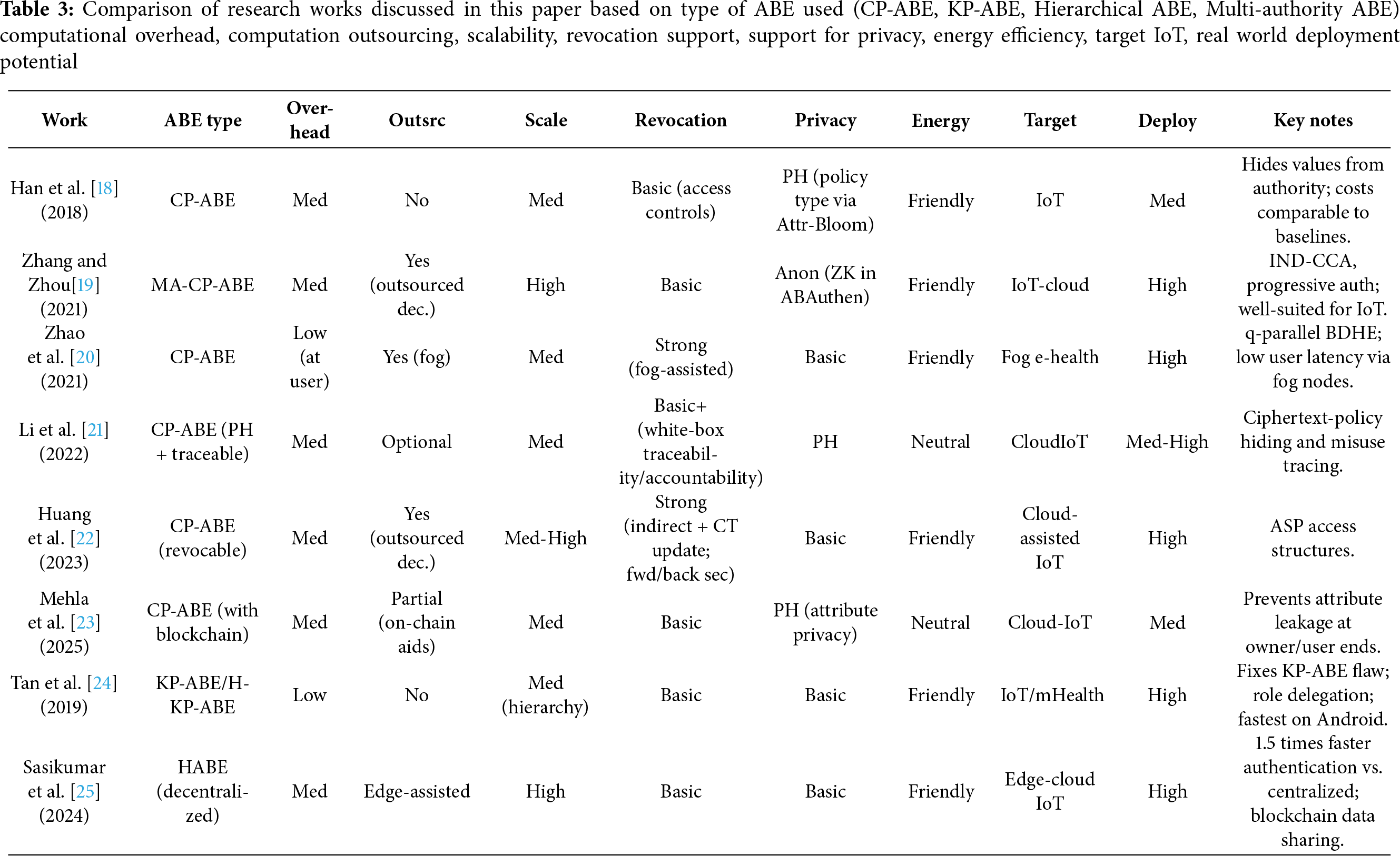

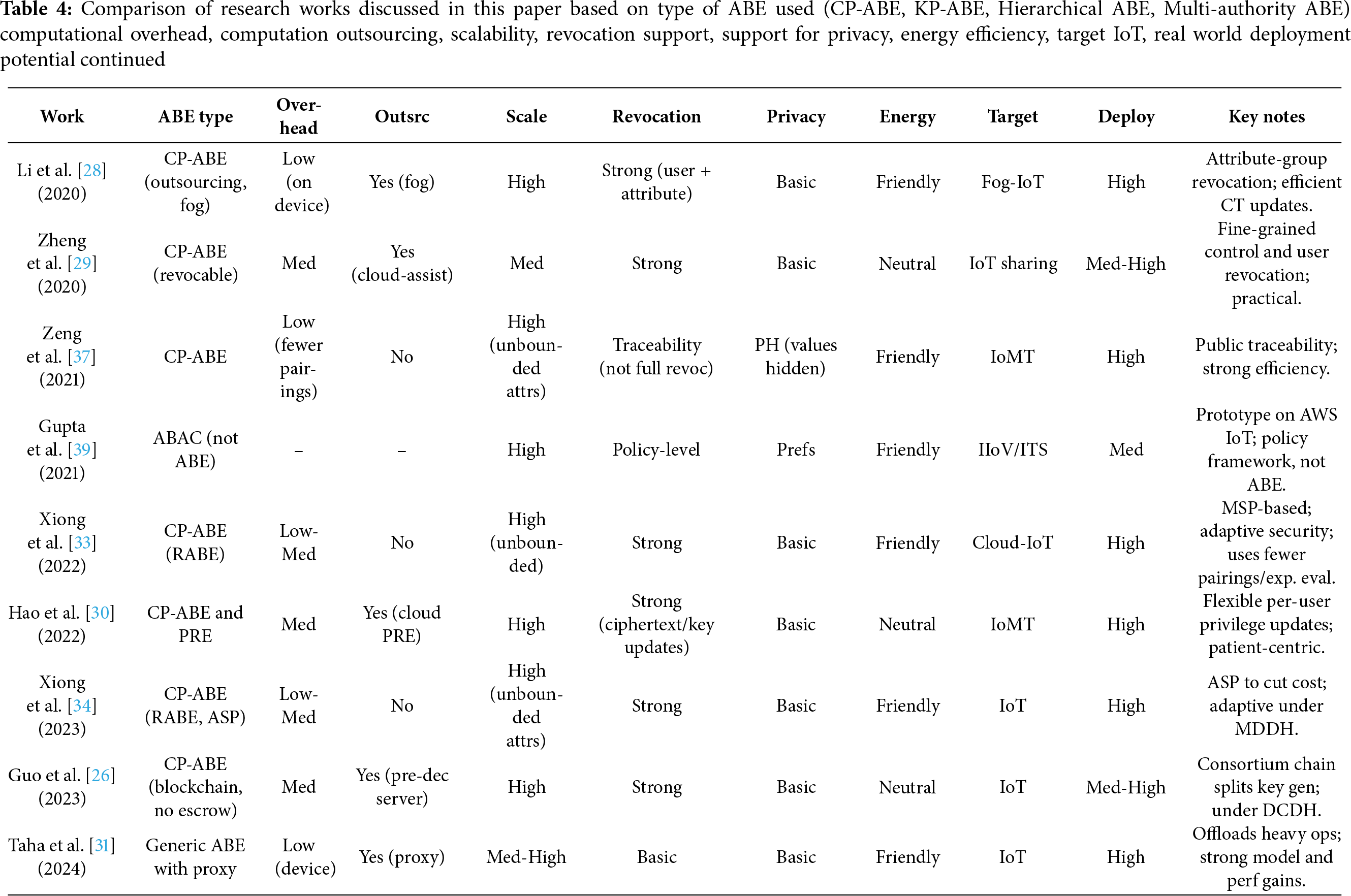

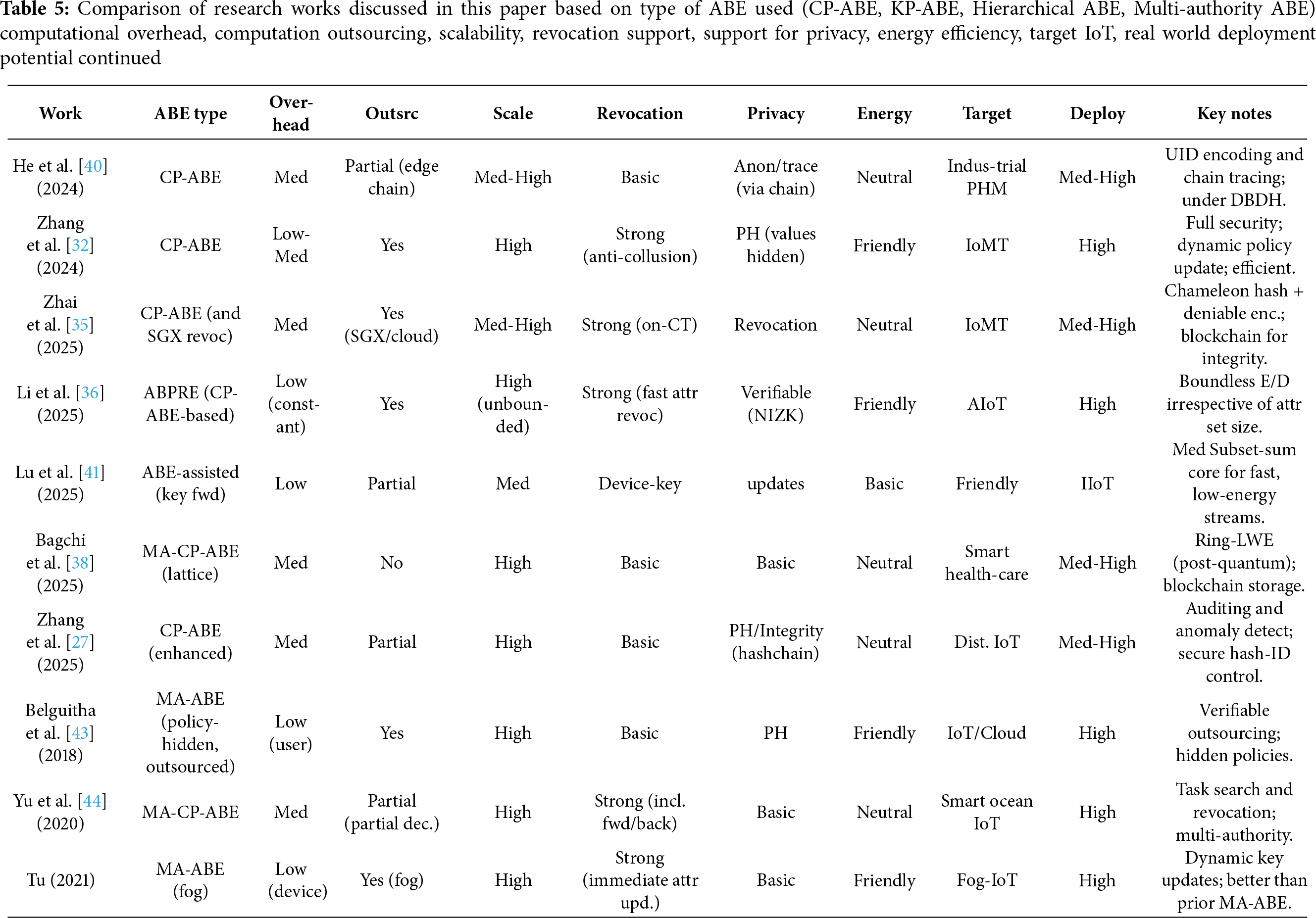

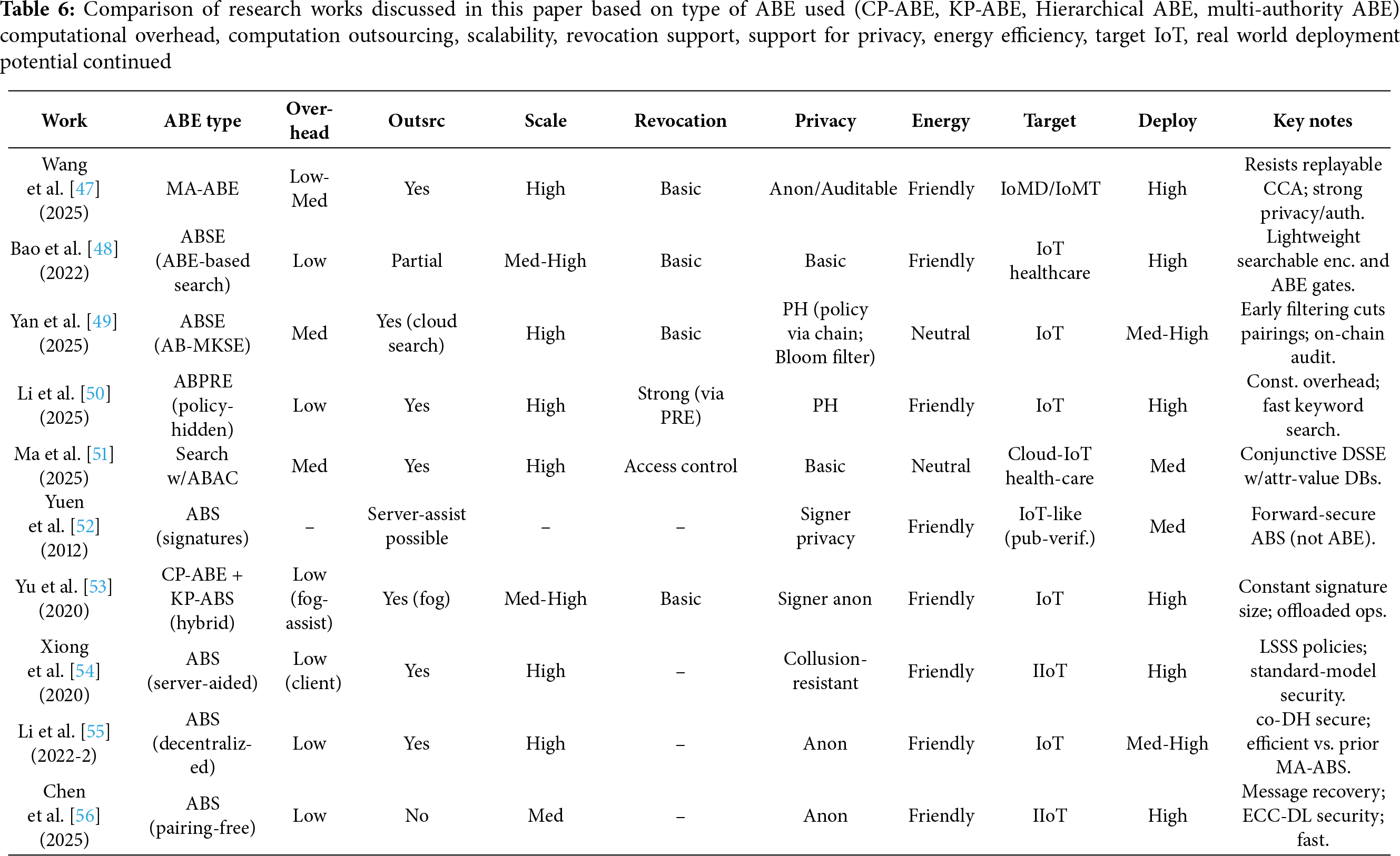

Tables 3–6 provide a compact, side-by-side classification and comparison of the research works surveyed in this paper.

Legend for the tables:

Overhead = computational overhead on end devices.

Outsrc = computation outsourcing;

Scale = scalability of the protocol;

Revoc = revocation support;

Privacy = privacy features (PH=policy hiding, Anon=anonymous/auth-private);

Energy = energy efficiency of the protcol on devices;

Target = primary setting;

Deploy = real-world deployment potential.

Here are the quick takeaways from the comparison in Tables 3–6:

• Li et al. [14,15] (2020), Zheng et al. [29] (2020), Huang et al. [22] (2023), Xiong et al. [33,34] (2022/2023), Tu et al. [45] (2021), Li et al. [50] (2025), Zhang et al. [32] (2024), Yu et al. [53] (2020) support strong revocation capability and scalability.

• Han et al. [18] (2018), Li et al. [21] (2022), Zeng et al. [37] (2021), Zhang et al. [32] (2024), Mehla et al. [23] (2025), Wang et al. [47] (2025), Zhai et al. [35] (2025), Yan and Zhang [49] (2025) and Li et al. [50] (2025) support good privacy features (policy hiding/anonymity ).

• Zhao et al. [20] (2021), Li et al. [28] (2020), Zhang and Zhou [19] (2021), Huang et al. [22] (2023), Zeng et al. [37] (2021), Tu et al. [45] (2021) and Yu et al. [53] (2020) are energy-friendly for resource-constrained devices by outsourcing computation to cloud/fog/noded or using low number of pairing operations.

• Zhang and Zhou [19] (2021), Phoabe (2018), Yu et al. [44] (2020), Tu et al. [45] (2021), Huang [46] (2021), Wang et al. [47] (2025) and Bagchi et al. [38] (2025) use Multi-authority ABE which is useful when sharing across different organization is needed.

• Zeng et al. [37] (2021), Zhang et al. [32] (2024), Zhai et al. [35] (2025), Hao et al. [30] (2022), Wang et al. [47] (2025) are focused on IoMT and show strong clinical applicability.

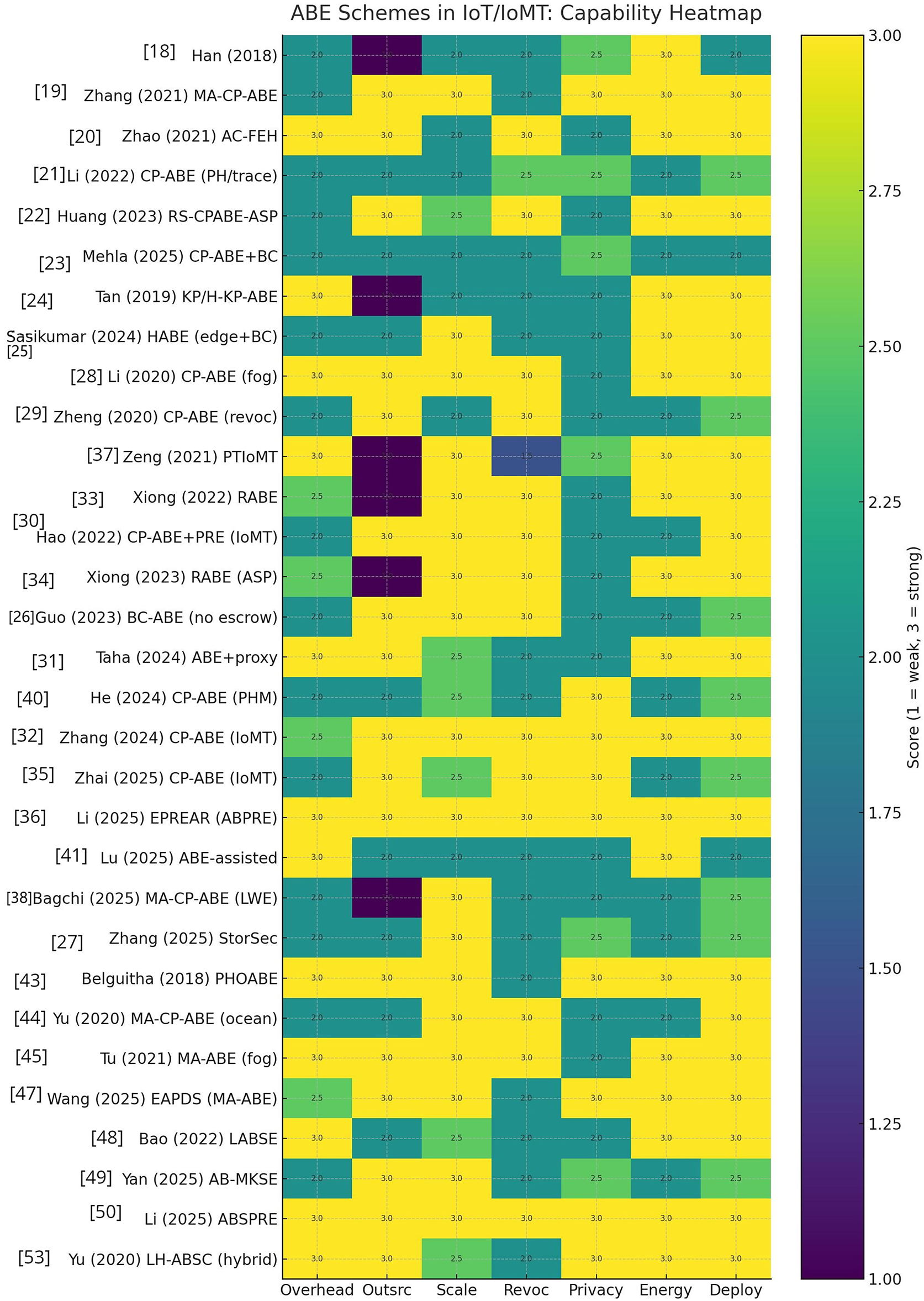

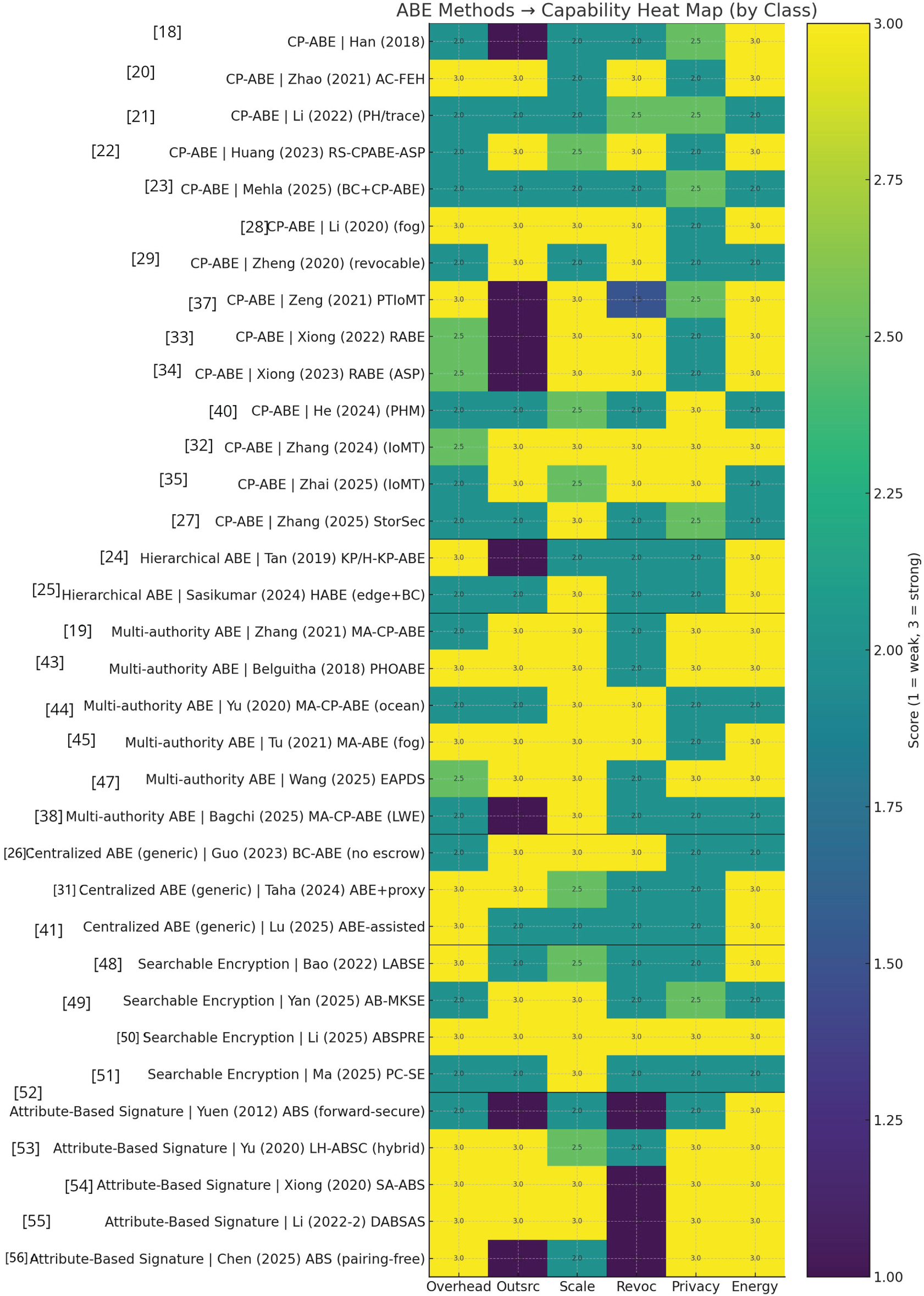

The heat map comparing the schemes across overhead, outsourcing, scalability, support for revocation, privacy-preservation, energy-efficiency, and deployment (scores: 1 = weak, 3 = strong) of all works discussed in this paper is shown in Fig. 2. A grouped heat map shown in Fig. 3 clusters works by method class—CP-ABE, Centralized ABE (single-authority generic), Hierarchical ABE, Multi-authority ABE, Searchable Encryption, and Attribute-Based Signature—and scores each on overhead, outsourcing, scalability, revocation, privacy, and energy use (1 = weak, 3 = strong).

Figure 2: Capability heat map of the reseach works discussed in this paper [18–38,41,43–45,47–50,53]

Figure 3: Capability heat map of the reseach works discussed in this paper, classified based on ABE methods used [18–38,41,43–45,47–50,53]

Even though ABE has been extensively studied in academic literature, applying Attribute-Based Encryption in IoT environments presents several challenges due to the unique characteristics of IoT systems. Below is a summary of some of the key challenges and open issues:

Computational Overhead and Resource Constraints: ABE operations–particularly CP-ABE and KP-ABE–involve computationally intensive cryptographic processes, such as pairing-based encryption, which are often unsuitable for resource-constrained IoT devices with limited processing power, memory, and battery life. To address this limitation, several studies have proposed offloading encryption and decryption tasks to fog nodes [20,28,45] or cloud servers [19,22,37]. Others have explored the use of decentralized, attribute-based server-aided signature schemes [29,32,53–56], while some employ Bloom filters [18,49] to efficiently filter unauthorized access requests before full decryption. However, outsourcing cryptographic operations introduces additional security concerns, such as data exposure and reliance on third-party trust. As a result, the design of lightweight and optimized ABE schemes that can be executed directly on constrained IoT devices—without compromising on security or flexibility—remains an important and ongoing research challenge.

Scalability: IoT environments often consist of thousands or even millions of devices and users, each requiring distinct access privileges. To address this, some efforts have been made toward supporting an unlimited number of attributes (or large universe attributes) [33,34,37,46]. Others used cloud-based or fog-enabled decryption [19,20,22,28,32,37,45] or multi-authority ABE schemes [44,45] to support scalability. However, designing ABE schemes that can scale efficiently with the growing number of devices and users–while minimizing key management overhead and ciphertext size as well as minimal outsourced decryption–remains an open research challenge.

Attribute and User Revocation: Revoking a user’s access or updating their attributes without re-encrypting all previously stored data remains a significant challenge in traditional ABE schemes. Typically, attribute revocation requires either re-encrypting affected ciphertexts or distributing updated decryption keys to all relevant users–both of which incur substantial overhead. Several studies have proposed solutions to this problem. Some support fine-grained access control and user revocation [29,33]. Others leverage arithmetic span programs [22,34] and some use dynamic updating of secret keys for immediate attribute revocation [45]; some support not only user revocation but also prevent collusion by revoked users [32]; some use dynamic policy updates via proxy encryption [50] for efficient revocation; attribute revocation and a task search function that supports dynamic on-demand services, all while ensuring forward and backward security has been proposed in [44]. However, many of these approaches introduce additional system complexity, potential security vulnerabilities, or delays in revocation enforcement, limiting their practical applicability in dynamic IoT environments. Consequently, the development of efficient, scalable, and secure revocation mechanisms that can handle dynamic changes in user privileges with minimal overhead remains an important area for future research.

Key Management and Distribution: Centralized ABE schemes typically depend on a single trusted authority for managing attribute keys. However, in large-scale or dynamic IoT networks, this centralized approach can become a performance bottleneck and introduces a single point of failure. To mitigate these issues, several studies have explored the use of multiple attribute authorities [19,38,43–47,55]. Despite these efforts, the design of fully decentralized or hierarchical ABE architectures that enable efficient, secure, and scalable key generation, distribution, and revocation remains an open area for further research.

Privacy Leakage: ABE schemes often embed access policies and attribute information directly into ciphertexts, which can inadvertently leak sensitive details about the underlying data or the intended access structure. To address this privacy concern, various research efforts have proposed different techniques, including: (i) protecting attribute information from the attribute authority [18,43], (ii) employing multi-authority CP-ABE frameworks for ciphertext-policy hiding [21,44], (iii) using partially hidden access policies [37], (iv) adopting decentralized ABE architectures [25], (v) integrating identifier encoding with ABE [40], (vi) concealing sensitive attribute values within access policies [32], (vii) implementing auditable privacy-preserving data sharing mechanisms [47], and (viii) encrypting attribute information for preventing leakage at both owner and user ends [23]. Despite these advances, the development of efficient and practical privacy-preserving ABE schemes that fully hide or obfuscate attributes and access policies from unauthorized parties remains an open and important research direction.

Latency and Real-Time Constraints: IoT applications such as smart grids, healthcare monitoring, and the Internet of Vehicles demand low-latency and real-time data processing. However, the computational overhead of traditional ABE schemes makes them unsuitable for these time-sensitive environments. Despite its importance, this challenge has received limited attention in existing research. Many of the schemes proposed try to address Latency by outsourcing decryption to cloud or fog-nodes [19,20,22,28,37,45]. Therefore, further investigation is needed to develop ABE schemes that can effectively meet real-time data access and encryption/decryption latency requirements while maintaining security and efficiency.

Fine-Grained Access vs. Performance: As access control policies in ABE-based systems become more fine-grained and expressive, they introduce increased computational and storage overhead. Complex policies result in larger ciphertexts and keys, leading to higher costs in encryption, decryption, and key management—particularly problematic in resource-constrained IoT environments. While several works [20,26,27,29,30,33,35,37,39,40,48,55] address fine-grained access control, few provide a thorough evaluation of its impact on performance. Thus, the design of efficient, low-overhead fine-grained access control mechanisms remains an important area for future research.

Collusion Resistance: Many ABE schemes are vulnerable to collusion attacks, where users combine their individual secret keys to decrypt a ciphertext that none of them is authorized to access individually. Preventing such unauthorized decryption is especially difficult in systems with large and complex attribute spaces. While some researchers have addressed this issue [32,54], collusion can occur in various forms—including among revoked users, among valid users, or between users and semi-trusted entities like cloud servers. Designing ABE schemes that are robust against all forms of collusion—ensuring that even coordinated adversaries cannot escalate their access privileges—remains a fundamental and ongoing challenge in the field.

Large Ciphertext and Key Sizes: In many ABE schemes—particularly CP-ABE and KP-ABE schemes [2,3]—the size of ciphertexts and decryption keys increases linearly, or even more rapidly, with the number of attributes involved. This growth significantly degrades system efficiency, rendering such schemes impractical for resource-constrained environments like IoT devices, where memory, processing power, and energy are limited. Despite its importance, this issue has received limited attention in the literature. Therefore, further research is needed to develop ABE schemes with reduced ciphertext and key sizes suitable for IoT applications.

Interoperability and Standardization: IoT systems typically comprise heterogeneous devices and platforms, many of which lack standardized support for ABE. As a result, developing interoperable and standardized ABE frameworks that can operate seamlessly across diverse IoT architectures and communication protocols remains an important area for future research.

Verifiability: Users often require assurance that ciphertexts are generated and decrypted correctly, without placing full trust in the system. This need arises from concerns about system vulnerabilities, human error, or malicious interference. Therefore, developing methods that enable users to independently verify the integrity and authenticity of both ciphertexts and decrypted data is essential for maintaining trust and ensuring system reliability.

Usability and Policy Design: Designing and managing complex attribute-based access policies can be challenging and error-prone, particularly for non-expert users. Therefore, developing intuitive policy languages and user-friendly tools for defining, validating, and managing access control policies is essential, especially in large-scale IoT deployments.

While Attribute-Based Encryption provides a promising framework for implementing fine-grained, attribute-based access control, its practical deployment in real-world systems encounters several significant challenges. These challenges span multiple dimensions, including efficiency, security, scalability, usability, and integration with existing infrastructure. For instance, ABE schemes often struggle with performance bottlenecks due to the complexity of encryption and decryption operations, and ensuring robust security under diverse attack models remains a constant concern. Additionally, scaling these systems to handle large numbers of users or attributes while maintaining optimal performance is a complex task. Usability issues arise when trying to make ABE systems intuitive for end-users, and integration into pre-existing platforms or services often requires extensive custom engineering. Overcoming these barriers demands innovative advancements not only in cryptographic algorithms but also in systems design, to enhance efficiency and scalability, and in usability engineering, to ensure that ABE solutions can be easily adopted in practical, real-world applications.

In this paper, we have presented a comprehensive and critical survey of research developments in the domain of Attribute-Based Encryption and Attribute-Based Access Control within the context of Internet of Things environments, as documented in the academic literature over the past decade. Our survey traces the conceptual evolution of Attribute-Based Encryption, providing a structured understanding of how the field has progressed from its theoretical foundations to more practical, application-oriented implementations. We systematically examine key trends, including the increasing emphasis on designing lightweight, scalable, and energy-efficient cryptographic solutions tailored to the resource-constrained nature of IoT devices.

Furthermore, we critically evaluate a wide range of ABE-based access control schemes, assessing their design goals, cryptographic frameworks, system architectures, and deployment feasibility. Particular attention is given to their performance trade-offs, security guarantees, and adaptability to dynamic IoT environments. In doing so, we highlight not only the strengths and innovations of existing approaches but also the persistent limitations and open challenges—such as efficient key management, real-time processing constraints, and revocation mechanisms—that continue to shape and motivate ongoing research in this area.

Acknowledgement: I did not receive any support.

Funding Statement: There was no funding support for this work.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable. This article does not involve data availability, and this section is not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sahai A, Waters B. Fuzzy identity based encryption. In: Proceedings of Eurocrypt-Springer LNCS. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2005. Vol. 3494, p. 457–73. [Google Scholar]

2. Goyal V, Pandey O, Sahai A, Waters B. Attribute-based encryption for fine-grained access control of encrypted data. In: Proceedings of 13th Computer and Communications Security Conference. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2006. p. 89–98. [Google Scholar]

3. Bethencourt J, Sahai A, Waters B. Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption. In: Proceedings of 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP ’07). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2007 May. p. 321–34. [Google Scholar]

4. Chase M. Multi-authority attribute based encryption. In: Vadhan SP, editor. Theory of cryptography. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2007. p. 515–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70936-7_28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Lewko A, Waters B. Decentralizing attribute-based encryption. In: Proceedings of EUROCRYPT 2011. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. Vol. 6632, p. 568–88. [Google Scholar]

6. Green M, Hohenberger S, Waters B. Outsourcing the decryption of ABE ciphertexts. In: Proceedings of the 20th USENIX Conference on Security, SEC’11. Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2011. 34 p. [Google Scholar]

7. Rouselakis Y, Waters B. Practical constructions and new proof methods for large universe attribute-based encryption. In: Proceedings of the 2013 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer & Communications Security (CCS ’13). New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2013 Nov. p. 463–74. [Google Scholar]

8. Agrawal S, Chase MP. FAME: fast attribute-based message encryption. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2017. p. 665–82. [Google Scholar]

9. Riepel D, Wee H. FABEO: fast attribute-based encryption with optimal security. In: Proceedings of the 2022 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS ’22. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2022. p. 2491–504. doi:10.1145/3548606.3560699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ambrona M, Barthe G, Gay R, Wee H. Attribute-based encryption in the generic group model: automated proofs and new constructions. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS ’17. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2017. p. 647–64. doi:10.1145/3133956.3134088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hsieh Y-C, Lin H, Luo J. A general framework for lattice-based abe using evasive inner-product functional encryption. In: Advances in Cryptology 9 EUROCRYPT 2024: 43rd Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques; 2024 May 26–30; Zurich, Switzerland. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. p. 433–64. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-58723-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gentry C, Silverberg A. Hierarchical ID-based cryptography. In: Zheng Y, editor. Advances in cryptology—ASIACRYPT 2002. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2002. p. 548–66. [Google Scholar]

13. Horwitz J, Lynn B. Toward hierarchical identity-based encryption. In: International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2002. p. 466–81. [Google Scholar]

14. Maji HK, Prabhakaran M, Rosulek M. Attribute-based signatures. In: Kiayias A, editor. Topics in cryptology—CT-RSA 2011. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. p. 376–92. [Google Scholar]

15. Li J, Au MH, Susilo W, Xie D, Ren K. Attribute-based signature and its applications. In: Proceedings of the 5th ACM Symposium on Information, Computer and Communications Security (ASIACCS ’10). New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2010 Apr. p. 60–9. [Google Scholar]

16. Rasori M, Manna ML, Perazzo P, Dini G. A survey on attribute-based encryption schemes suitable for the internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(11):8269–90. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3154039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Peñuelas-Angulo A, Feregrino-Uribe C, Morales-Sandoval M. Revocation in attribute-based encryption for fog-enabled internet of things: a systematic survey. Internet of Things. 2023;23(4):100827. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2023.100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Han Q, Zhang Y, Li H. Efficient and robust attribute-based encryption supporting access policy hiding in internet of things. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2018 Jun;83(7):269–77. doi:10.1016/j.future.2018.01.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang Z, Zhou S. A decentralized strongly secure attribute-based encryption and authentication scheme for distributed internet of mobile things. Comput Netw. 2021;201(1):108553. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2021.108553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhao J, Zeng P, Choo K-KR. An efficient access control scheme with outsourcing and attribute revocation for fog-enabled e-health. IEEE Access. 2021;9:13 789–99. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3025140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li J, Zhang Y, Ning J, Huang X, Poh GS, Wang D. Attribute based encryption with privacy protection and accountability for Cloud IoT. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2022;10(2):762–73. doi:10.1109/tcc.2020.2975184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Huang X, Xiong H, Chen J, Yang M. Efficient revocable storage attribute-based encryption with arithmetic span programs in cloud-assisted internet of things. IEEE Trans Cloud Comput. 2023;11(2):1273–85. doi:10.1109/tcc.2021.3131686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mehla R, Garg R, Khan MA. Privacy-preserving solution for data sharing in IoT-based smart consumer electronic devices for healthcare. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(2):4586–95. doi:10.1109/tce.2025.3540642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Tan S-Y, Yeow K-W, Hwang SO. Enhancement of a lightweight attribute-based encryption scheme for the internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(4):6384–95. doi:10.1109/jiot.2019.2900631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sasikumar A, Ravi L, Devarajan M, Selvalakshmi A, Almaktoom AT, Almazyad AS, et al. Blockchain-assisted hierarchical attribute-based encryption scheme for secure information sharing in industrial internet of things. IEEE Access. 2024;12:12 586–601. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3486869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Guo Y, Lu Z, Ge H, Li J. Revocable blockchain-aided attribute-based encryption with escrow-free in cloud storage. IEEE Trans Comput. 2023;72(7):1901–12. doi:10.1109/tc.2023.3234210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang S, Zhang W, Liang W, Jin W, Li K. StorSec: a comprehensive design for securing the distributed IoT storage systems. IEEE Trans Netw Serv Manag. 2025. doi:10.1109/tnsm.2025.3597550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li L, Wang Z, Li N. Efficient attribute-based encryption outsourcing scheme with user and attribute revocation for fog-enabled IoT. IEEE Access. 2020;8:176 738–49. doi:10.1109/access.2020.3025140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zheng D, Qin B, Li Y, Tian A. Cloud-assisted attribute-based data sharing with efficient user revocation in the internet of things. IEEE Wirel Commun. 2020;27(3):18–23. doi:10.1109/mwc.001.1900433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hao J, Tang W, Huang C, Liu J, Wang H, Xian M. Secure data sharing with flexible user access privilege update in cloud-assisted IoMT. IEEE Trans Emerg Top Comput. 2022;10(2):933–47. doi:10.1109/tetc.2021.3052377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Taha MB, Khasawneh FA, Quttoum AN, Alshammari M, Alomari Z. Outsourcing attribute-based encryption to enhance IoT security and performance. IEEE Access. 2024;12:166 800–13. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3491951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang L, Xie S, Wu Q, Rezaeibagha F. Enhanced secure attribute-based dynamic data sharing scheme with efficient access policy hiding and policy updating for IoMT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(16):27 435–47. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3399734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xiong H, Huang X, Yang M, Wang L, Yu S. Unbounded and efficient revocable attribute-based encryption with adaptive security for cloud-assisted internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(4):3097–111. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3094323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Xiong H, Qu Z, Huang X, Yeh K-H. Revocable and unbounded attribute-based encryption scheme with adaptive security for integrating digital twins in internet of things. IEEE J Sel Areas Commun. 2023;41(10):3306–17. doi:10.1109/jsac.2023.3310076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhai Y, Yang H, Yao J, Wang T, Zhou Y, Zhu F, et al. CR2-ABE: a blockchain-assisted coercion-resistant and revocable attribute-based encryption for IoMT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(9):13075–96. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3523959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li X, Xie Y, Peng C, Luo E, Li X, Zhou Z. EPREAR: an efficient attribute-based proxy re-encryption scheme with fast revocation for data sharing in AIoT. IEEE Trans Mob Comput. 2025;24(10):11005–18. doi:10.1109/tmc.2025.3573288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zeng P, Zhang Z, Lu R, Choo K-KR. Efficient policy-hiding and large universe attribute-based encryption with public traceability for internet of medical things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021;8(13):10 963–72. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3051362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bagchi P, Bisht A, Das AK, Saxena N, Hossain MS. Designing quantum-safe lattice-based multi-authority CP-ABE scheme for blockchain-enabled IoT-based consumer healthcare electronics. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2025;71(2):4983–94. doi:10.1109/tce.2025.3552021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Gupta M, Awaysheh FM, Benson J, Alazab M, Patwa F, Sandhu R. An attribute-based access control for cloud enabled industrial smart vehicles. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2021;17(6):4288–97. doi:10.1109/tii.2020.3022759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. He Y, Yan Z, Yuan T. Attribute-based access control scheme for secure identity resolution in prognostics and health management. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024;11(13):23 140–55. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3387079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lu J, Hu C, Chen J, Xia H, Li X, Yu J. A revocable fast and lightweight parallel encryption scheme for IIoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(15):30 808–19. [Google Scholar]

42. Perazzo P, Righetti F, La Manna M, Vallati C. Performance evaluation of attribute-based encryption on constrained IoT devices. Comput Commun. 2021;170:151–63. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2021.02.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Belguitha S, Kaaniche N, Laurent M, Jemai A, Attia R. PHOABE: securely outsourcing multi-authority attribute based encryption with policy hidden for cloud assisted IoT. Comput Netw. 2018 Mar;133(7):141–56. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2018.01.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Yu Y, Guo L, Liu S, Zheng J, Wang H. Privacy protection scheme based on CP-ABE in crowdsourcing-IoT for smart ocean. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(10):10061–71. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.2989476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Tu S, Waqas M, Huang F, Abbas G, Abbas ZH. A revocable and outsourced multi-authority attribute-based encryption scheme in fog computing. Comput Netw. 2021;195(4):108196. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2021.108196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Huang K. Revocable large universe decentralized multi-authority attribute-based encryption without key abuse for cloud-aided IoT. IEEE Access. 2021;9:151713–28. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3126780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang H, Xie Y, Luo M, Liu Y, Shirazi SH. EAPDS: efficient auditable and privacy-preservation data sharing scheme based on attribute-based encryption for IoMT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(14):26844–54. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3562541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Bao Y, Qiu W, Cheng X. Secure and lightweight fine-grained searchable data sharing for IoT-oriented and cloud-assisted smart healthcare system. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(4):2513–26. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3063846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Yan Z, Zhang B. An efficient attribute-based multi-keyword searchable encryption with access policy hiding in IoT using blockchain. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(15):32148–60. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3575802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Li M, Zhang Y, Huang C, Fang H, Shen J. Efficient attribute-based searchable proxy re-encryption with policy hiding over IoT data. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025;12(24):52766–80. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3613006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ma J, Peng T, Bei G, Waqas M, Alasmary H, Chen S. Efficient privacy-preserving conjunctive searchable encryption for cloud-iot healthcare systems. ACM Trans Priv Secur. 2025;29(1):1–27. doi:10.1145/3769425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Yuen TH, Liu JK, Huang X, Au MH, Susilo W, Zhou J. Forward secure attribute-based signatures. In: Chim TW, Yuen TH, editors. Information and communications security. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2012. p. 167–77. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-34129-8_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Yu J, Liu S, Wang S, Xiao Y, Yan B. LH-ABSC: a lightweight hybrid attribute-based signcryption scheme for cloud-fog-assisted IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020;7(9):7949–66. doi:10.1109/jiot.2020.2992288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Xiong H, Bao Y, Nie X, Asoor YI. Server-aided attribute-based signature supporting expressive access structures for industrial internet of things. IEEE Trans Ind Inform. 2020 Feb;16(2):1013–23. doi:10.1109/tii.2019.2921516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Li J, Chen Y, Han J, Liu C, Zhang Y, Wang H. Decentralized attribute-based server-aid signature in the internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(6):4573–83. doi:10.1109/jiot.2021.3104585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Chen Y, Li J, Lu Y, Zhang Y. Pairing-free attribute-based signature with message recovery for industrial internet of things. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput. 2025;22(6):6797–808. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2025.3590954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools