Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Does artificial intelligence (AI) anxiety increase employees’ deviant behavior toward the organization? The role of emotional exhaustion and leadership support

Department of Economics and Trade, Guangxi Eco-Engineering Vocational & Technical College, Liuzhou, 545003, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaolei Pan. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 207-214. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065761

Received 13 October 2024; Accepted 30 December 2024; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between AI anxiety and deviant behavior, as well as the roles of emotional exhaustion and leader support in this context. The sample comprised 381 Chinese e-commerce employees (72.7% female, age range 21–36 years). The results of the Process model analysis indicate that AI anxiety significantly is associated with higher deviant behaviour. Emotional exhaustion partially mediates this relationship between AI anxiety and employee deviant behavior exacerbating deviant behaviour. Leader support moderates the AI anxiety effect on emotional exhaustion such that when leader support is low. AI anxiety is associated with higher emotional exhaustion among employees. By implication, high levels of leader support can alleviate AI anxiety of employees. Employer organizations should provide appropriate guidance when introducing AI technology to prevent AI anxiety and associated emotional exhaustion and deviant behavior.Keywords

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology is reshaping the work world in unprecedented ways with its capabilities in automated reasoning, machine learning, and autonomous decision-making (Tang et al., 2023). AI is now integrated across various industries, including intelligent service robots in hospitality, chatbots like ChatGPT, autonomous driving and logistics optimization in transportation, and tools like Midjourney in design resulting in shifts in employment structures (Tschang & Almirall, 2021). However, as new technologies emerge and productivity increases, human labor demand often decreases (Dedrick et al., 2003), and the human labour “substitution effect” of AI is causing anxiety among some employees who fear job displacement Regrettably, AI anxiety can significantly impact individuals’ learning, work, and daily life (Li & Huang, 2020). According to projections from the McKinsey Global Institute, the rapid advance of AI suggests that by 2030, 15% to 30% of the global workforce could face the threat of unemployment, with millions more needing to change careers or upgrade their skills to adapt to these industry shifts (Manyika et al., 2017). Employees may engage in deviant behaviour to counteract what they may perceived as AI threats to their job security, in the absence of proactive leadership.

This calls for studies on the leadership qualities that would provide employees with a sense of AI safety for their work and organization thriving

AI anxiety and workplace deviant behavior

AI anxiety refers presents itself in various forms, including heightened fears of personal privacy breaches with insufficient regulation (Evans, 2009), and threats to employees with reliance by employers on AI massive data analysis in decision-making with a lack of transparency (Lloyd, 2018; Russell et al., 2015; Stahl & Wright, 2018) concerns about AI lack of transparency its operations, and seeming existential threats to human worker continuation (Bostrom, 2002; Clarke, 2019; Haladjian & Montemayor, 2016; Iphofen & Kritikos, 2021; Radanliev et al., 2022; Sehrawat, 2017). On the one hand, as a potential motivational force, AI anxiety can foster learning behavior (Wang & Wang, 2022) which would be advantage the competitiveness of both employees and their employer organizations enhancing their skills with job redesign (Cheng et al., 2023). On the other hand, AI anxiety can also lead to job insecurity, which may have the undesirable effect of increasing unwanted employee turnover (Koo et al., 2021) and employee deviant behavior. The role of leadership in managing this AI anxiety remains unclear, yet essential for organizations navigating the challenges of AI-driven transformations.

To alleviate the discomfort caused by anxiety, individuals may engage in avoidance behaviors. However, avoidance does not address the root of the problem, requiring individuals to exert self-control to cope with ongoing anxiety, which further depletes their resources (Eysenck et al., 2007). For instance, when faced with the pressures of learning complex AI technologies, individuals may feel anxious but realize that avoidance does not resolve the underlying challenge. Consequently, they must exert effort to suppress their anxiety and complete their tasks. In both passive and active scenarios, anxiety depletes self-control resources, ultimately leading to emotional exhaustion.

Psychological resources are critical in regulating individual behavior. When these resources were depleted, employees’ resistance to AI increased (Brougham & Haar, 2018). This resistance behavior manifests in various forms, including service sabotage (Ma & Ye, 2022; Zhao et al., 2023). Research by Zhao et al. (2023) indicates that employees may violate organizational norms and sabotage Employees may express dissatisfaction by intentionally reducing their job performance, which not only compromises service quality but also potentially harms customer satisfaction and organizational reputation. On the one hand, AI anxiety, as a workplace stressor, exacerbates employees’ concerns about future job stability, which may trigger destructive behaviors. On the other hand, AI system services may serve to protect depletion ofemployee resources so that employees would be more successful in their job roles and organizational commitment (Teng et al., 2024).

The mediating role of emotional exhaustion

The introduction of AI technology may exacerbate employees’ feelings of insecurity, triggering anxiety that may lead individuals into a state of self-depletion and emotional exhaustion. The link between AI-induced anxiety and emotional exhaustion can be categorized into two aspects: passive and active. First, anxious individuals often struggle to disengage from stimuli related to environmental threats (Bar-Haim et al., 2007). This heightened sensitivity causes their attention to be automatically drawn to external stimuli, disrupting daily tasks (Englert & Bertrams, 2012). In this scenario, anxious individuals must allocate more self-control resources to manage the distractions (Englert & Bertrams, 2012). Once these resources are depleted, individuals lose the capacity for self-regulation, potentially leading to emotional exhaustion (Prem et al., 2016). Thus, AI-induced anxiety may passively drive individuals into a state of emotional exhaustion. Second, anxious individuals tend to experience heightened insecurity and are more inclined to avoid anxiety-inducing situations (Mackey & Perrewé, 2014).

The moderating effect of leader support

In the workplace, employee motivation and satisfaction largely depend on the level of environmental support they receive (Klaeijsen et al., 2018), and leader support, specifically, is viewed as the level of support employees perceive from their superiors (Zhang et al., 2019). Leadersship is a crucial link between employees and work technologies (Bedi et al., 2016), providing resources and helping employees maintain emotional stability and preventing emotional exhaustion. AI-related anxiety, may lead to emotional exhaustion and deviant workplace behaviour in the absence of leadership support.

According to self-control theory, individuals can experience self-depletion during acts of willpower (Baumeister et al., 2018). When self-control resources are exhausted (i.e., during emotional exhaustion), not only are positive behaviors suppressed, but impulsive behaviors may also emerge (Fehr et al., 2017). This is because, when their control energy is depleted, individuals may abandon responsibility for themselves or others, indulging in short-term desires (Loewenstein, 1996). In essence, self-control is a balancing act between restraint and indulgence, with self-control resources acting as the fulcrum. When the fulcrum is broken (i.e., during emotional exhaustion), behavior may shift toward indulgence. For instance, a person on a diet may, when their self-control energy is depleted, abandon their healthy eating habits and opt for unhealthy food choices (Baumeister et al., 2008). Therefore, when individuals experience emotional exhaustion, they may fail to suppress internal impulses, leading to deviant behaviors as a means of satisfying immediate desires.

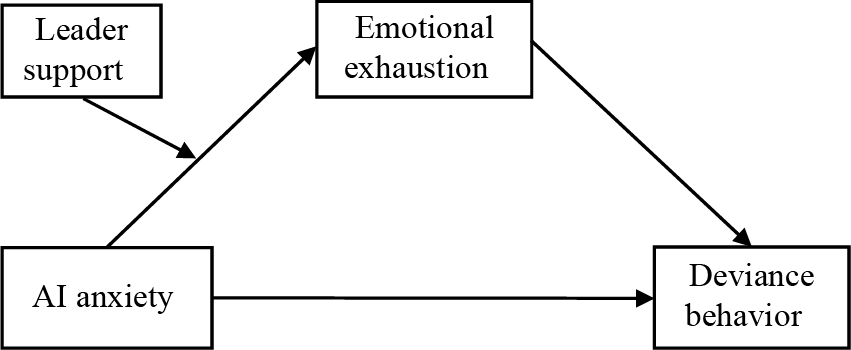

This study aimed to explore how Artificial Intelligence (AI) anxiety may increase employees’ deviant behavior toward the organization, and the role of emotional exhaustion and leadership support in that relationship. Based on these objectives, a moderated mediation model has been developed, as shown in Figure 1 presents our moderated mediation model for studying these relationship. Based on this model, we tested the following hypotheses:

Figure 1: Research model

H1. AI anxiety is associated with higher workplace deviant behavior.

H2. Emotional exhaustion mediates the relationship between AI anxiety and workplace deviant behavior for higher workplace deviant behavior.

H3. Leader support moderates the AI anxiety effect on workplace deviant behavior through emotional exhaustion for lower workplace deviant behavior.

The development of artificial intelligence (AI) technology has brought convenience to daily life and improved production efficiency, but it has also generated anxiety. While many studies have explored the definition and dimensions of AI anxiety, the relationship between AI anxiety and workplace deviant behavior remains under-researched. Therefore, a deeper understanding of employees’ anxiety and its impact on behavior is crucial for organizational management, particularly in the context of rapid technological advancements like AI. Organizations may need to implement effective measures to alleviate employee anxiety, reduce deviant behavior, and foster a healthier work environment.

The data were collected from an e-commerce service company employees (n = 381) located in Guangxi Province, China. The sample comprised 104 males (27.3%) and 277 females (72.7%) (age range 21 to 36 years). In terms of education, the majority of participants held vocational college degrees (75.9%), followed by undergraduate degrees (15.7%), and high school or technical secondary education (8.4%).

This study employed established scales from international research to measure AI anxiety, emotional exhaustion, leader support, and deviant behavior. All scales are on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

The AI anxiety scale, developed by Li and Huang (2020), consists six items on two dimensions: work replacement anxiety and learning anxiety. Sample items include: “I am worried that AI will replace my work in the future.”, “I do not think I would be able to perform well in professional courses in AI.” The Cronbach’s α for AI anxiety scale scores was 0.918.

The emotional exhaustion scale, developed by Maslach et al. (1997), consists of six items, Sample itemsare: “I feel emotionally drained from my work.”, “I feel exhausted after a long day at work.” The Cronbach’s α for the emotional exhaustion scale is 0.926.

The leader support scale, adapted from House and Wells (1978) by Zhang et al. (2019), consists of five items. Example items include: “My leader listens to my work-related problems.”, “My leader gives me aid in making work-related decisions.” The Cronbach’s α for the leader support scale scores was 0.925.

The deviance behavior scale, developed by Bennett and Robinson (2000), includes eight items. Example items are: “Spent too much time fantasizing or daydreaming instead of working.”, “Came in late to work without permission.” The Cronbach’s α for the deviance behavior scale scoreswas 0.941.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Scientific Research Collaboration Department of Guangxi Eco-Engineering Vocational and Technical College. All participants consented to the study. They were informed about the voluntary nature of the study and the confidentiality of their data. Data were collected online in two phases—initially on AI anxiety, emotional exhaustion, and deviant behaviour; and one month later on perceptions of leader support.

We utilized AMOS 24 and SPSS 22 for analysis. First, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis and a common method variance test. Next, we performed Pearson correlation analysis on the primary variables and control variables. Finally, we examined the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion using the PROCESS macro (Model 4) and assessed the moderating effect of leader support on the AI anxiety-emotional exhaustion-deviance behavior mediation using the PROCESS macro (Model 7). Specifically, we employed the bootstrap method to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI). Results were considered significant if the 95% CI did not include zero.

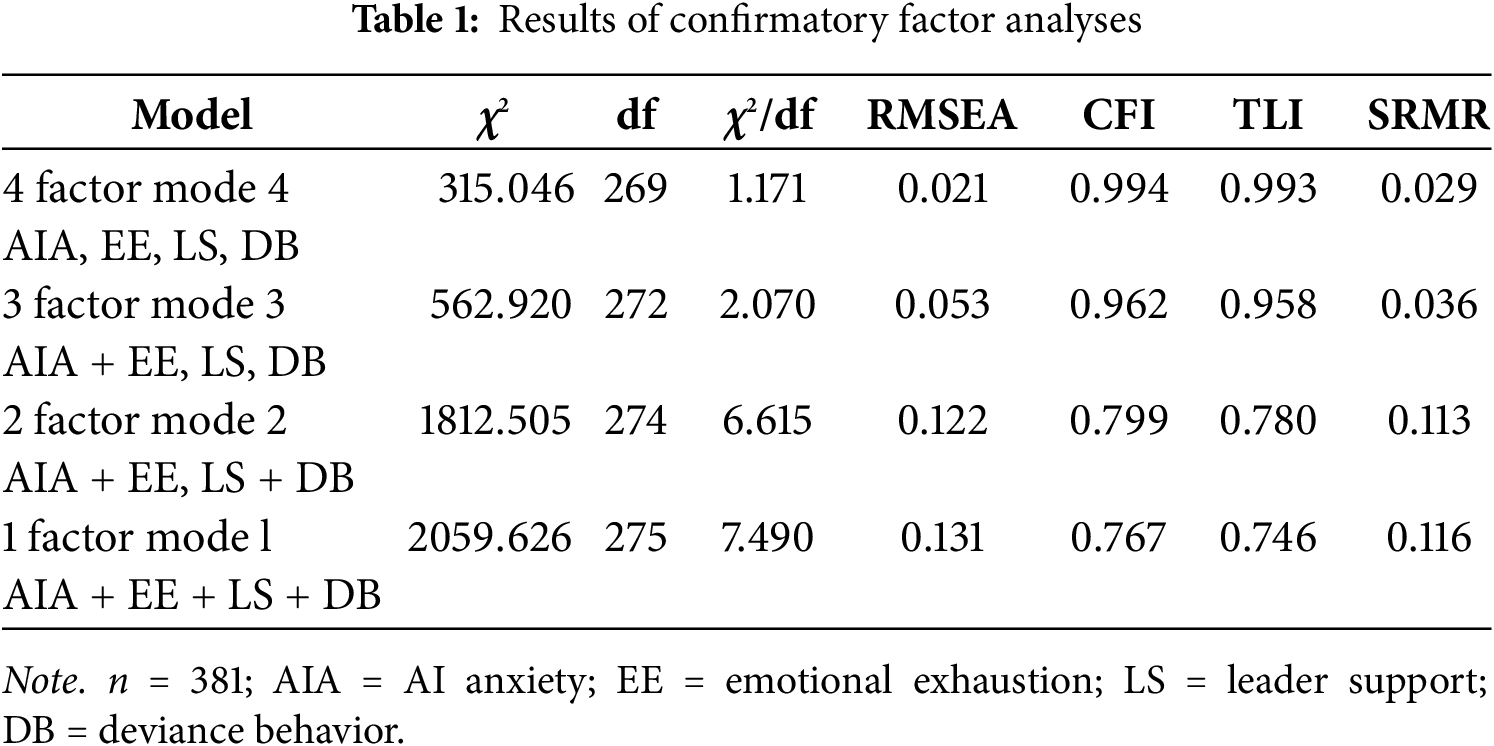

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using AMOS 24, and the model fit indices are presented in the Table 1. Among the models tested, the four-factor model—compri-sing AI Anxiety, Emotional Exhaustion, Leader Support, and Deviance Behavior—demonstrated the best fit [χ2/df = 1.171, RMSEA = 0.021, CFI = 0.994, TLI = 0.993, SRMR = 0.029]. This indicates that the four-factor model exhibits appropriate discriminant validity. For assessing common method variance, Harman’s single-factor test was employed. The results revealed that the variance explained by the first factor was 48.779%, which is below the 50% threshold. Therefore, no serious common method bias was detected in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

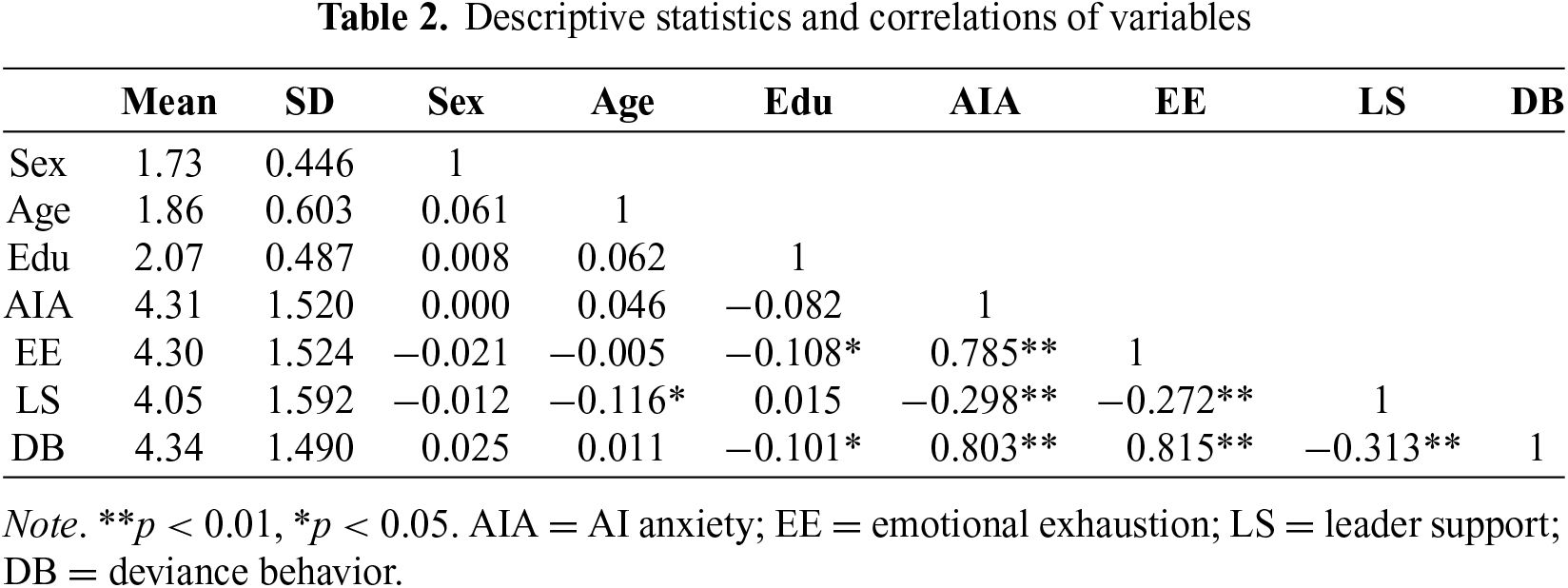

The means and standard deviations of each variable are shown in the Table 2. AI anxiety is positively correlated with emotional exhaustion (r = 0.785, p < 0.01), and negatively correlated with leader support (r = −0.298, p < 0.01). Additionally, AI anxiety is positively correlated with deviance behavior (r = 0.803, p < 0.01). Emotional exhaustion is negatively correlated with leader support (r = −0.272, p < 0.01) and positively correlated with deviance behavior (r = 0.815, p < 0.01). Leader support is negatively correlated with deviance behavior (r = −0.313, p < 0.01).

AI anxiety effect on deviant behavior

As shown in Figure 2, AI anxiety significantly affects deviant behavior (β = 0.7875, p < 0.01), thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

Figure 2: The mediating effect of emotional exhaustion. Note: ***p < 0.001. C’ represents the direct effect of AI anxiety on deviant behavior. C denotes the total effect of AI anxiety on deviant behavior. AIA = AI anxiety. EE = emotional exhaustion. DB = deviance behavior.

Emotional exhaustion mediation

We used PROCESS V3.3 with model 4 for a bootstrap-based analysis to examine the mediation effect of emotional exhaustion. Demographic variables (Sex, Age, Edu) were included as control variables. The results indicate that the direct effect of AI anxiety on deviance behavior is 0.4176, which is significant [95% CI = (0.3345, 0.5007), excluding 0]. Additionally, as Figure 2, emotional exhaustion positively impacts deviance behavior with significant results. Emotional exhaustion mediates the effect of AI anxiety on deviance behavior, with an indirect effect of 0.3683, also significant [95% CI = (0.2684, 0.4738), excluding 0]. Therefore, emotional exhaustion partially mediates the relationship between AI anxiety and deviance behavior, supporting Hypothesis 2.

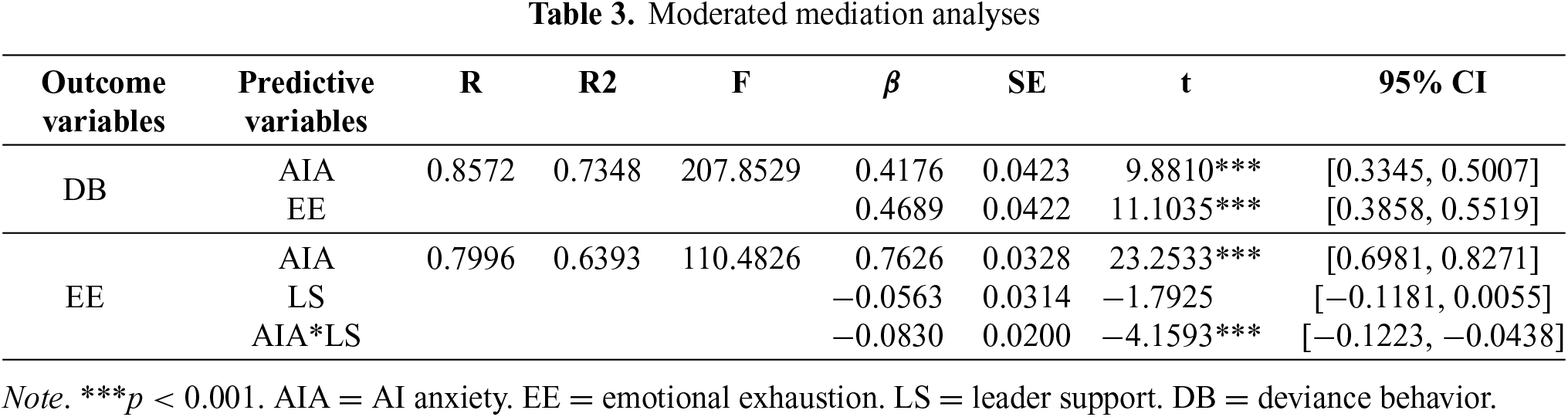

We used the PROCESS V3.3 macro (model 7) to examine the moderated mediation effect. As shown in the Table 3, AI anxiety positively predicts emotional exhaustion (β = 0.7626, p < 0.001), and emotional exhaustion positively predicts deviant behavior (β = 0.4689, p < 0.001). Although leader support does not significantly influence emotional exhaustion, the interaction between AI anxiety and leader support significantly affects emotional exhaustion (β = −0.0830, p < 0.001). This indicates that leader support moderates the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion between AI anxiety and deviant behavior, thus supporting hypothesis 3.

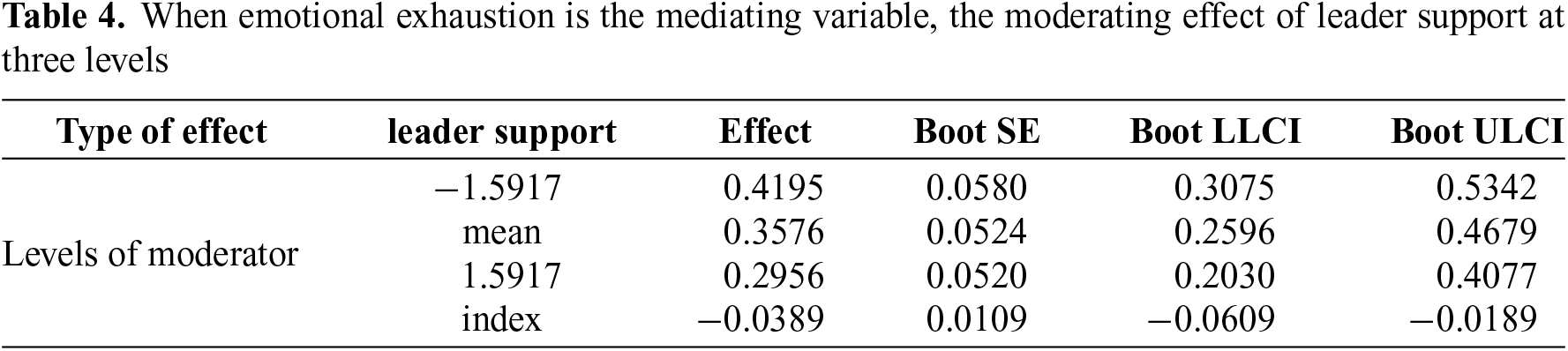

To further explore the moderating effect of leader support, a simple slope analysis was conducted. As shown in the Figure 3 and Table 4, when leader support is low (mean −1 SD), the mediating effect of AI anxiety on deviant behavior through emotional exhaustion is significant and relatively strong [β = 0.4195, 95% CI = (0.3075, 0.5342), excluding 0]. When leader support is high (mean +1 SD), the mediating effect remains significant but is weaker [β = 0.2956, 95% CI = (0.2030, 0.4077), excluding 0]. The difference in the mediating effect of AI anxiety on deviant behavior through emotional exhaustion is significant at different levels of leader support [β = −0.0389, 95% CI = (−0.0609, −0.0189), excluding 0]. These results suggest that the impact of AI anxiety on deviant behavior through emotional exhaustion decreases as leader support increases, thereby supporting Hypothesis 3.

Figure 3: Simple slope of the interaction between AI anxiety and leader support on emotional exhaustion

This study found AI anxiety to be associated with higher employees workplace deviant behavior, which is consistent with previous research findings (Chen et al., 2017). Deviant behavior is often viewed as a direct manifestation of anxiety (Bauer & Spector, 2015; Judge et al., 2006). If negative deviant deviant behaviour, it would pose a serious threat to employer organization competitiveness from workflow disruptions (Christian & Ellis, 2011).

Secondly, our study reveals a partial mediating role of emotional exhaustion in the relationship between AI anxiety and workplace deviant behavior. Although there is no direct evidence supporting this specific hypothesis, existing research has established a significant link between anxiety and emotional exhaustion (Fraschini & Park, 2021), as well as between emotional exhaustion and deviant behavior in the workplace (Ghasemi, 2022; Halbesleben & Buckley, 2004; Karatepe & Choubtarash, 2014). These findings align with the theory of self-control, which posits that individuals have the capacity to consciously regulate their behavior, thoughts, and emotions to suppress immediate impulses (Lange et al., 2012). However, self-control is a resource-depleting process (Hagger et al., 2010). When these resources are exhausted, individuals may experience emotional exhaustion, making it difficult to effectively control behavior, which can lead to deviant actions in the workplace, such as turnover, absenteeism, or ridiculing colleagues (Baumeister et al., 2018; Koutsimani et al., 2019; Neves & Champion, 2015). Therefore, in the age of AI, organizations must pay greater attention to employees’ mental health and emotional management, as these factors may indirectly influence both employee behavior and overall organizational well-being. Additionally, we call upon the academic community to further explore the relationship between AI anxiety and workplace deviance.

Finally, the results of the moderation analysis reveal the role of leader support in moderating the mediating effect of emotional exhaustion between AI anxiety and deviant behavior. This finding is consistent with existing research, which demonstrates that support can alleviate the emotional impact caused by anxiety, whether it be organizational or social support (Jones et al., 1991). Leader support, as a specific form of social support, plays a positive role in reducing subordinates’ stress and anxiety (Zhang et al., 2019). This finding further confirms the resource substitution function of leader support within the self-control theory, suggesting that when employees perceive support from their leaders, their self-control capacity is strengthened (Zhang et al., 2019). Therefore, this study highlights the critical role of leader support in promoting employees’ mental health and reducing deviant behavior.

Implications for Research and Practice

This study holds significant implications for the related field. First, it demonstrates that AI anxiety can significantly influence deviant behavior, extending the understanding of AI anxiety’s effects beyond its impact on learning motivation (Wang & Wang, 2022) to include its influence on negative behaviors. Additionally, we identify the partial mediating role of emotional exhaustion between AI anxiety and deviant behavior, indicating that employees engaging in workplace deviant behavior may be experiencing emotional exhaustion. As posited by self-control theory, anxiety depletes individuals’ control resources. Managers can improve the internal stress environment of the organization through their leadership style, which, in turn, enhances employee satisfaction with the company (Avolio et al., 2004).

Secondly, in the context of AI development, AI anxiety emerges as a critical factor in triggering deviant behavior. Therefore, organizations introducing AI technologies should provide AI training programs to facilitate a smoother transition for employees into the AI era. Moreover, reducing emotional exhaustion may be key to minimizing deviant behavior. Organizations should establish psychological counseling services and related programs to help employees manage anxiety-induced emotional issues. Additionally, our findings suggest that leader support can serve as a substitute resource for self-control, safeguarding employees from emotional strain. Thus, organizations should promote positive leadership practices to mitigate the emotional toll caused by an anxiety-inducing organizational climate.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has certain limitations. First, the sample is drawn from a single organization, without including members from other types of organizations. Future research should collect data from a broader range of organizational contexts to replicate our findings. Second, the assessment of deviant behavior relies on self-reported data, which may introduce bias. Future studies should employ more reliable evaluation methods, such as observational techniques or interviews, to improve the accuracy of behavioral assessments.

The influence of AI extends far beyond productivity gains. Although AI has brought unprecedented convenience to society and significantly increased efficiency, it also demands that employees continuously update and enhance their skills to keep pace with the rapidly evolving technological landscape (Daugherty & Wilson, 2018). For future directions, there is need studies on employee AI adaptation to reduce anxiety by employees struggle to stay in step with the rapid development of AI technologies.

In this study, we examined the relationship between AI anxiety and deviant behavior, as well as the underlying mechanisms of this relationship. The results indicate that emotional exhaustion partially mediates the relationship between AI anxiety and deviant behavior, while leader support mitigates the impact of AI anxiety on deviant behavior through emotional exhaustion. When leader support is low, AI anxiety exerts a stronger influence on individuals’ emotional states. However, with high levels of leader support, employees’ anxiety is alleviated. These findings fill a gap in the research on the relationship between AI anxiety and deviant behavior and offer guidance on how to reduce the negative impact of anxiety in the age of AI.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Guangxi Eco-Engineering Vocational & Technical College Talent Introduction Research Project and 2024 Guangxi Vocational Education Teaching Reform Research Project grant number [GXSTKYZX20240603] and [GXGZJG2024B125] and the APC was funded by GEVT College.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chengcheng Sha, Lin Wang; data collection: Chengcheng Sha, Xiaolei Pan; analysis and interpretation of results: Chengcheng Sha; draft manuscript preparation: Chengcheng Sha, Xiaolei Pan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval for this study was approved by the Scientific Research Collaboration Department of Guangxi Eco-Engineering Vocational and Technical College, with ethical approval number GXST20240708.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Avolio, B. J., Zhu, W., Koh, W., & Bhatia, P. (2004). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(8), 951–968. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.283 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H., (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bauer, J. A., & Spector, P. E. (2015). Discrete negative emotions and counterproductive work behavior. Human Performance, 28(4), 307–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2015.1021040 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (2018). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? In: Self-regulation and Self-control (pp. 16–44). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315175775 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baumeister, R. F., Sparks, E. A., Stillman, T. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2008). Free will in consumer behavior: Self-control, ego depletion, and choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 18(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2007.10.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2625-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bostrom, N. (2002). Existential risks: Analyzing human extinction scenarios and related hazards. Journal of Evolution and Technology, 9, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

Brougham, D., & Haar, J. (2018). Smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARAEmployees’ perceptions of our future workplace. Journal of Management & Organization, 24(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.55 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, Y., Li, S., Xia, Q., & He, C. (2017). The relationship between job demands and employees’ counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effect of psychological detachment and job anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1890. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cheng, B., Lin, H., & Kong, Y. (2023). Challenge or hindrance? How and when organizational artificial intelligence adoption influences employee job crafting. Journal of Business Research, 164(1), 113987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113987 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Christian, M. S., & Ellis, A. P. J. (2011). Examining the effects of sleep deprivation on workplace deviance: A self-regulatory perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 913–934. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0179 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Clarke, R. (2019). Why the world wants controls over artificial intelligence. Computer Law & Security Review, 35(4), 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2019.04.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Daugherty, P. R., & Wilson, H. J. (2018). Human + machine: Reimagining work in the age of AI. Brighton, MA, USA: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

Dedrick, J., Gurbaxani, V., & Kraemer, K. L. (2003). Information technology and economic performance: A critical review of the empirical evidence. ACM Computing Surveys, 35(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1145/641865.641866 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Englert, C., & Bertrams, A. (2012). Anxiety, ego depletion, and sports performance. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 34(5), 580–599. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.34.5.580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Evans, D. S. (2009). The online advertising industry: Economics, evolution, and privacy. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(3), 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.23.3.37 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fehr, R., Yam, K. C., He, W., Chiang, J. T.-J., & Wei, W. (2017). Polluted work: A self-control perspective on air pollution appraisals, organizational citizenship, and counterproductive work behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 143(2), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.02.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fraschini, N., & Park, H. (2021). Anxiety in language teachers: Exploring the variety of perceptions with Q methodology. Foreign Language Annals, 54(2), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12527 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ghasemi, F. (2022). The effects of dysfunctional workplace behavior on teacher emotional exhaustion: A moderated mediation model of perceived social support and anxiety. Psychological Reports, 127(5), 003329412211466. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941221146699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hagger, M. S., Wood, C., Stiff, C., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(4), 495–525. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Haladjian, H. H., & Montemayor, C. (2016). Artificial consciousness and the consciousness-attention dissociation. Consciousness and Cognition, 45(2), 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.08.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Buckley, M. R. (2004). Burnout in organizational life. Journal of Management, 30(6), 859–879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

House, J. S., & Wells, J. A. (1978, April). Occupational stress, social support, and health. In: Reducing Occupational Stress: Proceedings of a Conference (pp. 78–140). Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

Iphofen, R., & Kritikos, M. (2021). Regulating artificial intelligence and robotics: Ethics by design in a digital society. Contemporary Social Science, 16(2), 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2018.1563803 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jones, F., Fletcher, B. E. N., & Ibbetson, K. (1991). Stressors and strains amongst social workers: Demands, supports, constraints, and psychological health. The British Journal of Social Work, 21(5), 443–469. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a055787 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Judge, T. A., Scott, B. A., & Ilies, R. (2006). Hostility, job attitudes, and workplace deviance: Test of a multilevel model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Karatepe, O. M., & Choubtarash, H. (2014). The effects of perceived crowding, emotional dissonance, and emotional exhaustion on critical job outcomes: A study of ground staff in the airline industry. Journal of Air Transport Management, 40(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2014.07.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Klaeijsen, A., Vermeulen, M., & Martens, R. (2018). Teachers’ innovative behaviour: The importance of basic psychological need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, and occupational self-efficacy. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 62(5), 769–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2017.1306803 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Koo, B., Curtis, C., & Ryan, B. (2021). Examining the impact of artificial intelligence on hotel employees through job insecurity perspectives. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95(1), 102763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102763 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., & Georganta, K. (2019). The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lange, P. A. M., van Kruglanski, A. W., & Higgins, E. T. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of theories of social psychology. vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

Li, J., & Huang, J.-S. (2020). Dimensions of artificial intelligence anxiety based on the integrated fear acquisition theory. Technology in Society, 63(9), 101410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101410 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lloyd, K. (2018). Bias amplification in artificial intelligence systems (Version 1). https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.1809.07842 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Loewenstein, G. (1996). Out of control: Visceral influences on behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 65(3), 272–292. [Google Scholar]

Ma, C., & Ye, J. (2022). Linking artificial intelligence to service sabotage. The Service Industries Journal, 42(13–14), 1054–1074. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2022.2092615 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mackey, J. D., & Perrewé, P. L. (2014). The AAA (appraisals, attributions, adaptation) model of job stress: The critical role of self-regulation. Organizational Psychology Review, 4(3), 258–278. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386614525072 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Manyika, J., Lund, S., Chui, M., Bughin, J., Woetzel, J. et al. (2017). Jobs lost, jobs gained: Workforce transitions in a time of automation. McKinsey Global Institute, 150(1), 1–148. [Google Scholar]

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). Maslach Burnout Inventory: Third edition. In C. P. Zalaquett & R. J. Wood (Eds.), Evaluating stress: A book of resources (pp. 191–218). Lanham: Scarecrow Education. [Google Scholar]

Neves, P., & Champion, S. (2015). Core self-evaluations and workplace deviance: The role of resources and self-regulation. European Management Journal, 33(5), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2015.06.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Prem, R., Kubicek, B., Diestel, S., & Korunka, C. (2016). Regulatory job stressors and their within-person relationships with ego depletion: The roles of state anxiety, self-control effort, and job autonomy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Radanliev, P., De Roure, D., Maple, C., & Ani, U. (2022). Super-forecasting the ‘technological singularity’ risks from artificial intelligence. Evolving Systems, 13(5), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12530-022-09431-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Russell, S., Hauert, S., Altman, R. B., & Veloso, M. (2015). Take a stand on AI weapons. Nature, 521(7553), 415–418. https://doi.org/10.1038/521415a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sehrawat, V. (2017). Autonomous weapon system: Law of armed conflict (LOAC) and other legal challenges. Computer Law & Security Review, 33(138–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2016.11.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stahl, B. C., & Wright, D. (2018). Ethics and privacy in AI and big data: Implementing responsible research and innovation. IEEE Security & Privacy, 16(3), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSP.2018.2701164 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tang, P. M., Koopman, J., Mai, K. M., De Cremer, D., Zhang, J. H. et al. (2023). No person is an island: Unpacking the work and after-work consequences of interacting with artificial intelligence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(11), 1766–1789. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Teng, R., Zhou, S., Zheng, W., & Ma, C. (2024). Artificial intelligence (AI) awareness and work withdrawal: Evaluating chained mediation through negative work-related rumination and emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 36(7), 2311–2326. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2023-0240 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tschang, F. T., & Almirall, E. (2021). Artificial intelligence as augmenting automation: Implications for employment. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(4), 642–659. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2019.0062 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Y.-Y., & Wang, Y.-S. (2022). Development and validation of an artificial intelligence anxiety scale: An initial application in predicting motivated learning behavior. Interactive Learning Environments, 30(4), 619–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1674887 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, J., Cao, C., Shen, S., & Qian, M. (2019). Examining effects of self-efficacy on research motivation among Chinese university teachers: Moderation of leader support and mediation of goal orientations. The Journal of Psychology, 153(4), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1564230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhao, J., Hu, E., Han, M., Jiang, K., & Shan, H. (2023). That honey, my arsenic: The influence of advanced technologies on service employees’ organizational deviance. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75(4), 103490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103490 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools