Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Social desirability response bias confounds the effect of gender on social media addiction

1 Mental Health and Counseling Center, Guangdong Ocean University, Zhanjiang, 524088, China

2 Department of Psychology/Research Center of Adolescent Psychology and Behavior, School of Education, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, 510006, China

* Corresponding Author: Jian Mao. Email:

# Zuo and Mao contributed equally to this paper

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 241-247. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065765

Received 16 September 2024; Accepted 21 February 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This study examined how social desirability responses confound the relationship between gender and social media addiction. A total of 496 college student social media users (females = 310, 62.5%, mean age = 20.15, SD = 1.26) completed an online questionnaire on Social Media Addiction and Social Desirability. Mediation analysis revealed that females were at higher risk for social media addiction. On the other hand, the indirect effect of gender on social media addiction via social desirability is associated with lower social media addiction, which suggests that social desirability had a suppression effect on social media addiction associated with gender. ANOVA results showed that females reported higher social media addiction scores than males in the low social desirability group; in the high group, gender differences were insignificant. This study’s unique contribution is to suggest that females are at higher risk than males for developing addictive social media behaviors. Based on this finding, student social media safety interventions should be gender sensitive to the social desirability effect on females who may hide their true addiction as a result.Keywords

Social media addiction is a fact of life in this digital age and rapidly overtaking substance use addiction in human populations. A meta-analysis found that the overall prevalence of social media addiction was 24% in 32 countries or regions (Cheng et al., 2021), with a higher prevalence in collectivist countries than at the global level (31%). The prevalence of social media addiction among Chinese college students is even up to 44.5% (Tang et al., 2018). Social media addiction (SMA) refers to the behavioral addictive tendency to use social media at high levels for long periods, with various symptoms (salience, relapse, withdrawal, mood modification, tolerance, and conflict) as in behavioral addiction, and risks for health and wellbeing (Andreassen, 2015). However, risks may vary by gender, as with substance use disorders, and little is known about social media addiction in females. Most studies (e.g., Andreassen et al., 2016; Bányai et al., 2017; Servidio et al., 2021) including a meta-analysis (Su et al., 2020) showed that females report higher social media addiction scores than males, but other empirical studies (e.g., Koc & Gulyagci, 2013; Turel & Serenko, 2020; Teng et al., 2021) do not support this. Some of these differences could be due to social desirability predispositions by gender, which are less well studied, of which females may under-report for various reasons. Social desirability is the tendency of individuals to comply with their culture’s values and standards to win approval from others (Zerbe & Paulhus, 1987). For instance, females are more likely to be influenced by social desirability than males (Dalton & Ortegren, 2011). Therefore, we were interested in determining whether social desirability contaminates the actual gender differences in social media addiction.

Gender and social media addiction

In general, researchers believe that females are more likely than males to be addicted to social media (Kuss & Griffiths, 2014, 2015), and many empirical studies have confirmed gender differences in SMA (Bányai et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018; Servidio et al., 2021; Ünal-Aydın et al., 2020; Samra et al., 2022). The gender role perspectives on social expression preferences by gender are in need of further study. For instance, females are more interested in communicating with others than males and also being understood by others (Bussey & Bandura, 1999; Qian et al., 2000). Moreover, females generally consider it their primary task to maintain relationships in their lives (Eagly, 1987; Liu et al., 2011). Thus, females are more inclined to manage relationships through social media (Krasnova et al., 2017; Kircaburun et al., 2020), and to spend more time on social media than males (Jeong et al., 2016; Müller et al., 2016; Oberst et al., 2017; Servidio et al., 2021).

However, the connection between gender and social media addiction is not as straightforward as one might think. Several other studies have not found gender differences in social media addiction (Koc & Gulyagci, 2013; Turel & Serenko, 2020; Teng et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). Even studies found significantly higher levels of addiction in males than females (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2023; Yang & Jiang, 2020). These differences in findings may be explained by the fact that males and females become addicted based on different motivations for use (Koc & Gulyagci, 2013). To clarify the relationship between gender and social media addiction, Su et al. (2020) took a meta-analytic approach to integrate and estimate data from 41 independent samples from 22 countries and regions. Their results found gender differences in social media addiction levels globally with females scoring significantly higher than males (Su et al., 2020). However, there was a large heterogeneity (Q = 1357.70, p < 0.001) in the effect sizes obtained in this study, suggesting additional factors may complicate the gender-SMA link. We speculate that social desirability response bias may confound the gender-related differences in social media addiction in ways yet to be examined.

Social desirability and social media addiction

Social desirability by which individuals report more socially desirable attitudes and behaviors and less socially undesirable ones (Krumpal, 2013), is associated with reporting more positive emotions, life satisfaction, and happiness (Soubelet & Salthouse, 2011; Surbey, 2011; Heintzelman et al., 2015), and less reporting of substance abuse, mobile phone addiction, social media addiction, and online compulsive buying (Foster, 2013; Poínhos et al., 2015; Davenport et al., 2012; Latkin et al., 2017; Turel & Serenko, 2020; Mohta & Halder, 2021).

Ganster et al., (1983) summarized three models of how social desirability as the primary variable affects other variables. First, the spuriousness model, in which social desirability may lead to spurious correlations among variables. For example, studies have found that females perceive themselves to be more ethical than males (e.g., Ariail et al., 2012). However, the gender differences in ethics were non-significant after controlling for social desirability (Dalton & Ortegren, 2011). Second is the suppression model, where social desirability suppresses the true relationship between the independent and dependent variables. For example, one study found that the predictive effect of extraverted personality on aggression changed from insignificant to significant after controlling for social desirability (Liu & Liu, 2021). Third, in the moderator model, there are interactions between the independent variables and social desirability. For example, Bai and Zhang (1996) found that the level of social desirability moderated the relationship between altruistic orientation and pro-social behavior or intention. Given that the purpose of the present study was to explain why gender was not significantly associated with SMA, and based on the foundation of previous research we suggest that social desirability may play a suppressing and moderating role between gender and SMA.

Gender and social media addiction: social desirability as a suppressor

The suppression variable is an additional factor that strengthens the correlation between the independent variable (X) and the dependent variable (Y) (MacKinnon et al., 2000). The difference between suppressing variables and mediating variables is that the latter explains “how X impacts Y,” while the former explains “why X does not impact Y.” (Wen & Ye, 2014; Ludlow & Klein, 2014). In this study, we contend that the connection between gender and SMA may be masked by social desirability. Specifically, females did not show higher SMA tendencies compared to males because of their higher levels of social desirability.

Gender and social media addiction: social desirability as a moderator

Social desirability may also moderate the gender-SMA association. As mentioned previously, individuals with high social desirability underestimate their SMA scores whereas those with low social desirability report more true SMA levels (Wu & Xu, 2007; Mohta & Halder, 2021; Kwak et al., 2021). Thus, gender differences (female > male) in SMA may be significant in groups with low social desirability tendencies. However, because females are more susceptible to social desirability bias than males, females are more likely to underestimate their level of SMA in groups with high social desirability tendencies. Hence, it may lead to insignificant gender differences in SMA or differences in the opposite direction (male > female). Previous studies can support the above assumptions. A meta-analytic study by Su et al. (2020) showed that the gender difference (female > male) in SMA was significant in the European and North American groups but not in the Asian group. The above distinction may be explained by social desirability. In general, Asians live in a higher collectivist context and these people have a higher social desirability tendency than Europeans and North Americans who live in an individualistic cultural context (Keillor et al., 2001). In addition, other studies have shown that social desirability has a moderating effect. Gucciardi et al. (2010) found that social desirability moderated the relationship between athletes’ attitudes toward doping and susceptibility to doping behaviors.

In particular, the current study has two purposes. First, to examine whether the effect of gender on social media addiction (females > males) holds after controlling for social desirability. Second, to examine whether gender differences in social media addiction depend on the sample group’s level of social desirability. We addressed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Social desirability suppresses the relationship between gender and social media addiction leading females to report lower social media addiction scores due to their higher social desirability levels.

Hypothesis 2. Social desirability moderates the gender-social media addiction relationship to be comparable across gender with low levels of social desirability and not vice versa.

Findings will provide novel insights into gender differences in social media addiction, highlighting the importance of focusing on gendered social desirability responses in social media addiction research.

The participants were 496 students from two colleges in central China. Of the included sample 186 (37.5%) were males and 310 (62.5%) were females; ages ranged from 18 to 26 years (M = 20.15, SD = 1.265). There are 94 (19%) first-year students, 224 (45.2%) second-year students, 166 (33.5%) third-year students, and 12 (2.4%) fourth-year students.

Using the 8-item Facebook Addiction Scale (Koc & Gulyagci, 2013), participants reported on the items on a 5-point Likert scale “1 = not true” and “5 = extremely true”, “Facebook” was replaced with “social media”. Higher scores indicate individuals with a stronger degree of social media addiction. In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient for SMA scores was 0.83.

Using the 13-item Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MCSD) developed by Reynolds (1982) presents five positive descriptions (e.g., When I make a mistake I always dare to admit it) and eight negative descriptions (e.g., Sometimes I take advantage of others.). The participants rated the items as “yes = 1” and “no = 0” (and the inverse questions were scored in reverse). The minimum score is 0 and the maximum score is 13, with higher scores indicating a greater tendency to social desirability. In this study, the MCSD Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.66.

This study was conducted under the ethical standards set forth in the 2013 Helsinki Declaration. Classroom teachers granted study permission. The participants granted consent to the study. They took the surveys online with assurances of voluntary participation and confidentiality.

SPSS 23.0 was used for data analysis. Gender was coded as “0 = male, 1 = female”, and the correlation coefficient between gender and other variables was calculated using point biserial correlation. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated between other variables. The indirect (suppression) effect of Hypothesis 1 was tested using Model 4 in the SPSS macro program PROCESS developed by Hayes (2017). To better understand the moderating role of social desirability, we refer to Latkin et al.’s (2017) study, which was divided into a low and high social desirability group (low = 1, high = 2) using the median (this study: median = 7) boundaries when testing Hypothesis 2. We then tested the interaction of gender and social desirability on SMA using the two-factor ANOVA. To test the suppressing effect of social desirability, Model 4 in the SPSS macro program PROCESS developed by Hayes (2017) was employed, with gender as the independent variable, social desirability as the mediating variable and SMA as the dependent variable.

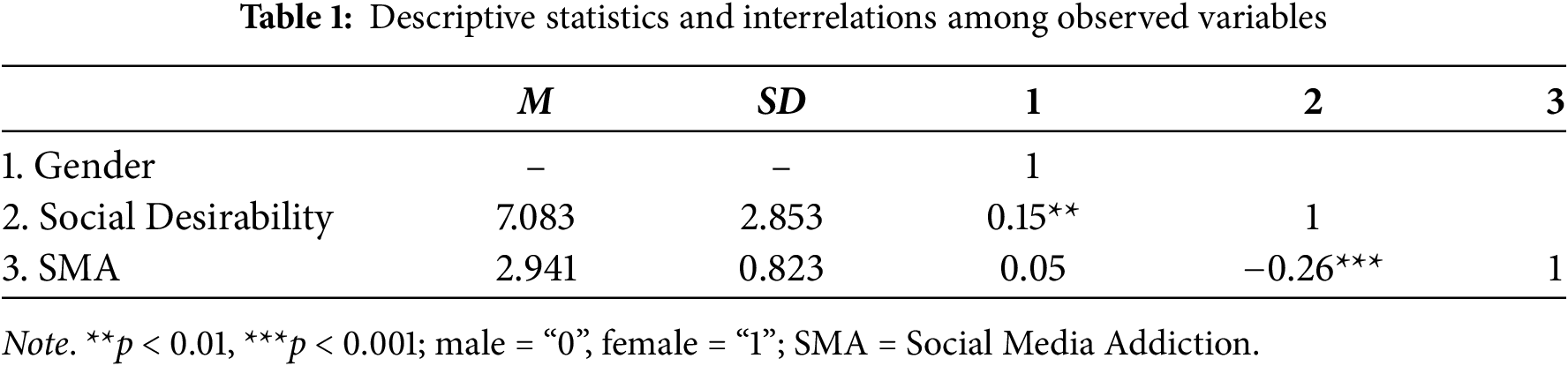

From Table 1, gender was not significantly correlated with SMA, indicating no significant gender differences in SMA. Gender was positively correlated with social desirability, and social desirability was negatively correlated with SMA.

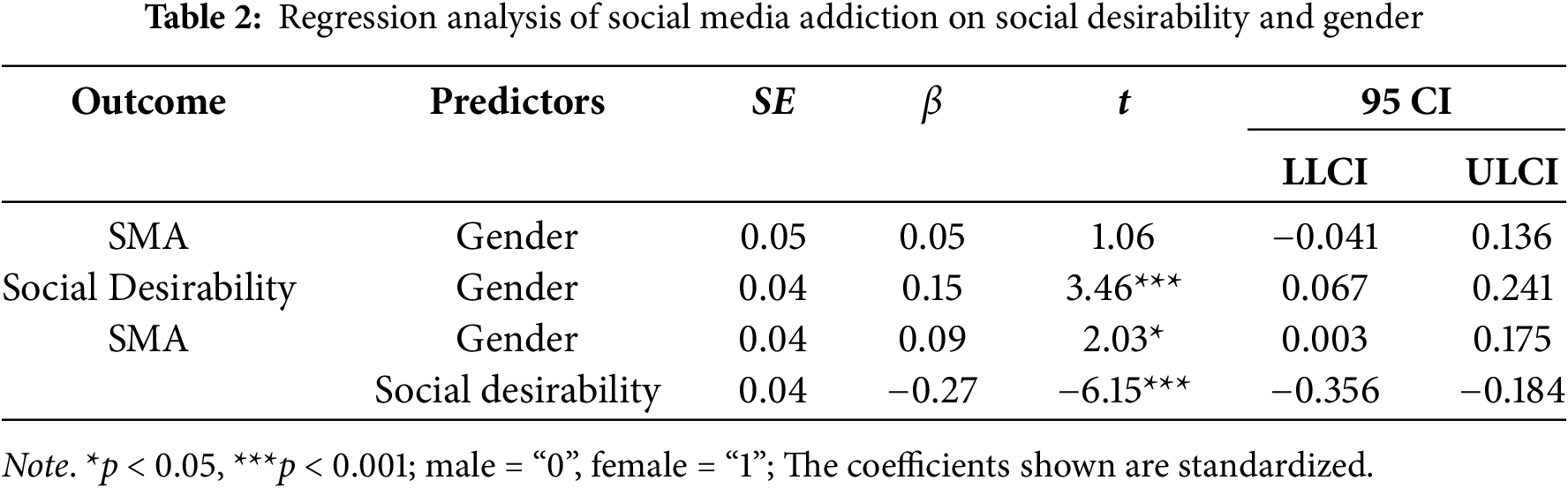

Social desirability as suppression

Table 2 shows the standardization coefficient result that females were associated with higher social desirability (β = 0.15, p < 0.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.067, 0.241]). Females scored higher than males on social desirability; social desirability negatively predicted SMA (β = −0.27, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.356 −0.184]). Thus, gender significantly and positively predicted SMA directly (β = 0.09, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.003 0.175]), indicating that females’ SMA level was significantly higher than males. These results suggest a gendered social desirability suppression effect, as gender was not significantly related to social media addiction. Thus H1 was supported.

Social desirability as moderation

To test the moderating effect of social desirability, a two-factor ANOVA was conducted with gender as the independent variable, social desirability (1 = low, 2 = high) as the moderating variable, and SMA as the dependent variable. The results showed that the main effect of gender on SMA was not significant (F(1,492) = 1.420, p = 0.234 > 0.005), the main effect of social desirability on SMA was significant (F(1,492) = 29.161, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.056), and the interaction effect of gender and social desirability on SMA was significant (F(1,492) = 9.591, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.019). The results of the simple effects test (Figure 1) showed that females showed a higher SMA score of 0.316 than males (95% CI = [0.126, 0.506], p < 0.01) for the low social desirability group; for the high social desirability group, the gender difference in SMA score was not significant (95% CI = [−0.359, 0.078], p = 0.208 > 0.05). Thus H2 was supported.

Figure 1: Gender differences in social media addiction across levels of social desirability. SD = Social desirability

Does social media addiction have a gender difference or not? It is an issue often explored by researchers in the field of SMA. Consistent with the results of the meta-analysis (Su et al., 2020), this paper suggests that females are more likely to be addicted to social media than males. However, the relationship between gender and SMA may be biased and contaminated by social desirability. Females generally have a higher propensity for social desirability than males. Research on gender roles indicated that in general females tend to underestimate their negative traits more and exhibit more social norm compliance (Qian et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2011). Numerous studies have also shown that females score higher than males on social desirability, impression management, and social approval (Bell & Naugle, 2007; Hopwood et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2022).

With social desirability, gender positively predicted social desirability, which in turn was associated with a decrease in SMA. More importantly, the direct predictive effect of gender on SMA was significant and positive. It indicates that the true effect of gender on SMA was suppressed by social desirability (Wen & Ye, 2014; Ludlow & Klein, 2014). The results explain well why gender is not significantly associated with SMA.

The gender-positive prediction of SMA is consistent with the results of meta-analyses (Su et al., 2020) supporting the belief that females are more likely to be addicted to social media than males (Andreassen, 2015; Kuss & Griffiths, 2015). First, research based on biological indicators suggested that females are more sensitive to social information (Proverbio, 2021). Gender role socialization theories also state that females focus more on interpersonal interactions than males (Eagly, 1987; Bussey & Bandura, 1999). Second, previous research has demonstrated that females are more early adopters of social media than males (Fujimori et al., 2015; Chae et al., 2018). In terms of motivation for use, females are keen to use social media to communicate, interact, and share their life status while males tend to be entertained and amused (Kircaburun et al., 2020). Relying on social media to maintain social connections leads females to develop more addictive social media behaviors (Chae et al., 2018).

In contrast, females tend to report lower SMA scores via the indirect effect of social desirability. First, this study found that females tended to report higher social desirability than males, which can be explained in terms of gender roles. Gender socialization theories suggest that males are socialized to relate to energetic values such as confidence and independence. In contrast, females are socialized to relate to collective values such as enthusiasm, and concern for others (Bussey & Bandura, 1999; Qian et al., 2000). Females identify their primary task as managing social relationships (Eagly, 1987; Liu et al., 2011). Therefore, females are more susceptible to the effects of social norms and values and are more likely to project a positive impression, which leads to a stronger desire to respond in a socially expected manner. Second, high levels of social desirability were associated with lower SMA scores. It is understandable because addictive behaviors associated with many negative consequences are not socially expected with society expecting fewer addictive behaviors (Turel et al., 2011).

The present study also found the moderating effect of social desirability on the association between gender and SMA. To be specific, among those with low social desirability, females outscored males on the SMA, whereas, in the high social desirability group, females showed no significant difference in scores with males. In conclusion, in light of our findings, the conclusions that claim males and females are equally susceptible to social media addiction (e.g., Koc & Gulyagci, 2013) and that addiction to social media is more prevalent among males than females (e.g., Yang & Jiang, 2020) need to be treated with caution, because they ignore the role of social desirability bias.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Findings are significant in view of the fact that information technology continues to advance rapidly, social media (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and WeChat) has become an important tool for most people to communicate and entertain themselves. Undoubtedly, social media fulfills psychological needs and provides many conveniences. However, a concern is that users may become addicted to social media, which can be detrimental to mental and physical health (for reviews, see Andreassen, 2015; Kuss & Griffiths, 2017). Numerous studies have been conducted to investigate the causes of and risk factors for addiction to social media, with gender differences being one of the main foci of researchers (Kuss & Griffiths, 2017).

This study has two significant implications. First, SMA is a socially sensitive topic and a socially disapproved negative behavior (Turel et al., 2011). Individuals with high social desirability are more dishonest (Wu & Xu, 2007) and tend to report lower SMA scores, as confirmed by several empirical studies (Turel & Serenko, 2020; Kwak et al., 2021; Mohta & Halder, 2021). Because females are at higher social desirability levels than males, they are more likely to underestimate their true SMA scores resulting in an insignificant overall effect of gender on SMA. This reasoning can be supported by research in other fields. A meta-analytic study on corporate ethical decision-making indicated that social desirability responses influenced females to report more ethical behavior than males but after controlling for social desirability the gender effect was insignificant (Yang et al., 2017).

Second, without considering social expectations, we would have concluded that there is no gender difference in SMA. However, when the effect of social desirability was considered, the opposite conclusion was obtained—a point often neglected in previous studies. Thus, when exploring protective variables for SMA, it is extremely vital to account for social desirability. Methods that can be used include indirect questioning, measuring social desirability for statistical control, and implicit association tests (Krumpal, 2013; Turel & Serenko, 2020). Finally, a greater focus on females is necessary for social media addiction prevention and intervention.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study has certain limitations. One challenge is that the current research was conducted in a Chinese collectivist culture with an overall high level of social desirability. Whether the study results can be generalized to other countries and regions is an open question. In addition, the convenience sample of college students hinders the generalization of the results, and future studies could utilize a probability sample. Finally, the current study presents only early evidence that females may underreport their SMA scores. Future studies need to combine experimental or indirect questioning with self-report to examine how males’ and females’ subjective social media addiction scores differ from their objective scores, and to continue focusing on social desirability.

The present study found social desirability suppressed and moderated the relationship between gender and SMA. Females were found to have a higher prevalence after controlling for this factor compared to males. Furthermore, the gender differences (females > males) in SMA were only significant in the low social desirability group but insignificant in the high social desirability group. Thus, our findings further support the view that females have a higher risk of SMA than males. Females may be more influenced by social desirability and disguise their social media addiction. Therefore, future research related to social media addiction needs to focus on how social desirability bias can be taken into account in the design of social media addiction risk reduction interventions.

Acknowledgement: Sincere thanks to all the students who participated in this study.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Guangdong Education Science Planning Project (2024GXJK612).

Author Contributions: Lihua Zuo: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Jian Mao: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Willingness to disclose and has been uploaded on: https://osf.io/m4qvp/files/osfstorage (accessed on 09 May 2025).

Ethics Approval: This study was conducted under the ethical standards set forth in the 2013 Helsinki Declaration. All of the study participants gave informed consent. Because our study was completely anonymous we did not require participants to sign a written informed consent form. After providing information about the study we asked on the questionnaire “Do you agree to participate in the study?” All participants voluntarily selected “yes.”

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Andreassen, C. S. (2015). Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review. Current Addiction Reports, 2(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Andreassen, C. S., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z. et al. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology Addiction Behaviors, 30, 252–262. https://psycnet.apa.org/buy/2016-13379-006 [Google Scholar]

Ariail, D. L., Abdolmohammadi, M. J., & Smith, L. M. (2012). Ethical predisposition of certified public accountants: A study of gender differences. In: J. Cynthia (Ed.Research on professional responsibility and ethics in accounting (vol. 16, pp. 29–56). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1574-0765(2012)0000016005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bai, L. G., & Zhang, Z. G. (1996). An experimental study on the relationship between altruistic orientation, social desirability and pro-social behavior among middle school students. Psychologyical Development and Education, 12(4), 8–13. http://www.devpsy.com.cn/CN/Y1996/V12/I4/8 [Google Scholar]

Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Király, O., Maraz, A., Elekes, Z. et al. (2017). Problematic social media use: Results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One, 12(1), e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bell, K. M., & Naugle, A. E. (2007). Effects of social desirability on students’ self-reporting of partner abuse perpetration and victimization. Violence and Victims, 22(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1891/088667007780477348 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Brailovskaia, J., Ozimek, P., Rohmann, E., & Bierhoff, H. W. (2023). Vulnerable narcissism, fear of missing out (FoMO) and addictive social media use: A gender comparison from Germany. Computers in Human Behavior, 144(1), 107725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107725 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106(4), 676–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.106.4.676 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chae, D., Kim, H., & Kim, Y. A. (2018). Sex differences in the factors influencing Korean college students’ addictive tendency toward social networking sites. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16(2), 339–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9778-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cheng, C., Lau, Y. C., Chan, L., & Luk, J. W. (2021). Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addictive Behaviors, 117(2), 106845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106845 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Dalton, D., & Ortegren, M. (2011). Gender differences in ethics research: The importance of controlling for the social desirability response bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(1), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0843-8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Davenport, K., Houston, J. E., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Excessive eating and compulsive buying behaviours in women: An empirical pilot study examining reward sensitivity, anxiety, impulsivity, self-esteem and social desirability. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10(4), 474–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9332-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

Foster, D. W. (2013). Readiness to change and gender: Moderators of the relationship between social desirability and college drinking. Journal of Alcoholism & Drug Dependence, 2(1), 1000141. https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-6488.1000141 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fujimori, A., Yamazaki, T., Sato, M., Hayashi, H., Fujiwara, Y. et al. (2015). Study on influence of internal working models and gender differences on addiction of social network sites in Japanese university students. Psychology, 6(14), 1832–1840. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2015.614179 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ganster, D. C., Hennessey, H. W., & Luthans, F. (1983). Social desirability response effects: Three alternative models. Academy of Management Journal, 26(2), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.5465/255979 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gucciardi, D. F., Jalleh, G., & Donovan, R. J. (2010). Does social desirability influence the relationship between doping attitudes and doping susceptibility in athletes? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11(6), 479–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2010.06.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

Heintzelman, S. J., Trent, J., & King, L. A. (2015). Revisiting desirable response bias in well-being reports. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.927903 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hopwood, C. J., Flato, C. G., Ambwani, S., Garland, B. H., & Morey, L. C. (2009). A comparison of Latino and Anglo socially desirable responding. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(7), 769–780. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20584 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jeong, S. H., Kim, H., Yum, J. Y., & Hwang, Y. (2016). What type of content are smartphone users addicted to?: SNS vs. games. Computers in Human Behavior, 54(2), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.035 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Keillor, B. D., Owens, D., & Pettijohn, C. (2001). A cross—cultural/cross national study of influencing factors and socially desirable response biases. International Journal of Market Research, 43(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530104300101 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kircaburun, K., Alhabash, S., Tosuntaş, Ş. B., & Griffiths, M. D. (2020). Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the Big Five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9940-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Koc, M., & Gulyagci, S. (2013). Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: The role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(4), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0249 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Krasnova, H., Veltri, N. F., Eling, N., & Buxmann, P. (2017). Why men and women continue to use social networking sites: The role of gender differences. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 26(4), 261–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2017.01.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kuss, D., & Griffiths, M. (2014). Internet addiction in psychotherapy. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Internet addiction in psychotherapy. London, UK: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 311. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030311 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kwak, D. H. A., Ma, X., & Kim, S. (2021). When does social desirability become a problem? Detection and reduction of social desirability bias in information systems research. Information & Management, 58(7), 103500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2021.103500 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Latkin, C. A., Edwards, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., & Tobin, K. E. (2017). The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore. Maryland Addictive Behaviors, 73(3), 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.005 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, X. R., Jiang, Y. Z., & Zhang, B. (2018). The influence of loneliness on problematic mobile social networks usage for adolescents: The role of interpersonal distress and positive self presentation. Journal of Psychological Science, 41(5), 1117–1123. http://www.psysci.org/CN/Y2018/V/I5/1117 [Google Scholar]

Liu, D. Z., Huang, H. X., Jia, F. Q., Gong, Q., Huang, Q., & Li, X. (2011). A new sex-role inventory (CSRI-50) indicates changes of sex role among Chinese college students. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 43(6), 639–649. https://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/Y2011/V43/I06/639 [Google Scholar]

Liu, X., & Liu, X. (2021). How social desirability influences the association between extraversion and reactive aggression: A suppression effect study. Personality and Individual Differences, 172(1), 110585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110585 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ludlow, L., & Klein, K. (2014). Suppressor variables: The difference between “is” versus “Acting As”. Journal of Statistics Education, 22(2), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2014.11889703 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1026595011371 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mohta, R., & Halder, S. (2021). A comparative study on cognitive, emotional, and social functioning in adolescents with and without smartphone addiction. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(4), 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973134220210404 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Müller, K. W., Dreier, M., Beutel, M. E., Duven, E., Giralt, S., & Wölfling, K. (2016). A hidden type of internet addiction? Intense and addictive use of social networking sites in adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(2), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Oberst, U., Wegmann, E., Stodt, B., Brand, M., & Chamarro, A. (2017). Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. Journal of Adolescence, 55(1), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.008 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Poínhos, R., Oliveira, B. M., & Correia, F. (2015). Eating behavior in Portuguese higher education students: The effect of social desirability. Nutrition, 31(2), 310–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2014.07.008 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Proverbio, A. M. (2021). Sex differences in the social brain and in social cognition. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 101(5), 730–738. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24787 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Qian, M. Y., Zhang, G. J., Luo, S. H., & Zhang, X. (2000). Sex role inventory for college students (CSRI). Acta Psychologica Sinica, 32(1), 99–104, https://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/Y2000/V32/I1/99 [Google Scholar]

Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the marlowe-crowne social desirability scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(1), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198201)38:1<119::AID-JCLP2270380118>3.0.CO;2-I [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Samra, A., Warburton, W. A., & Collins, A. M. (2022). Social comparisons: A potential mechanism linking problematic social media use with depression. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 11(2), 607–614. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00023 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Servidio, R., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2021). Dark triad of personality and problematic smartphone use: A preliminary study on the mediating role of fear of missing out. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8463. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168463 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Soubelet, A., & Salthouse, T. A. (2011). Influence of social desirability on age differences in self-reports of mood and personality. Journal of Personality, 79(4), 741–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00700.x [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Su, W., Han, X., Yu, H., Wu, Y., & Potenza, M. N. (2020). Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 113(1), 106480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106480 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Surbey, M. K. (2011). Adaptive significance of low levels of self-deception and cooperation in depression. Evolution and Human Behavior, 32(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.08.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tang, J. S., Haslam, R. L., Ashton, L. M., Fenton, S., & Collins, C. E. (2022). Gender differences in social desirability and approval biases, and associations with diet quality in young adults. Appetite, 175(4), 106035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106035 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tang, C. S. K., Wu, A. M. S., Yan, E. C. W., Ko, J. H. C., Kwon, J. H. et al. (2018). Relative risks of Internet-related addictions and mood disturbances among college students: A 7-country/region comparison. Public Health, 165(3), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.09.010 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Teng, X. C., Lei, H., Li, J. X., & Wen, Z. (2021). The influence of social anxiety on social network site addiction of college students: The moderator of intentional self-regulation. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 29(3), 514–517. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.03.014 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Turel, O., & Serenko, A. (2020). Cognitive biases and excessive use of social media: The facebook implicit associations test (FIAT). Addictive Behaviors, 105(3), 106328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106328 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Turel, O., Serenko, A., & Giles, P. (2011). Integrating technology addiction and use: An empirical investigation of online auction users. MIS Quarterly, 35(4), 1043–1061. https://doi.org/10.2307/41409972 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ünal-Aydın, P., Balıkçı, K., Sönmez, İ., & Aydın, O. (2020). Associations between emotion recognition and social networking site addiction. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112673 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, M. Y., Yin, Z. Z., Xu, Q., & Niu, G. F. (2020). The relationship between shyness and adolescents’social network sites addiction: Moderated mediation model. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(5), 906–909, 914. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2020.05.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wen, Z., & Ye, B. (2014). Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(5), 731–745. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1042.2014.00731 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, Y., & Xu, J. P. (2007). A study on the social desirability responding in the junior middle school students’ honesty test. Psychological Development and Education, 23(3), 107–111. http://www.devpsy.com.cn/CN/Y2007/V23/I3/107 [Google Scholar]

Xu, S., Li, Q., Yin, Y. X., & Liang, D. (2014). Psychological health diathesis assessment system: Establishing national norms of social desirability for chinese adults. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 12(6), 748–755. https://psybeh.tjnu.edu.cn/CN/Y2014/V12/I6/748 [Google Scholar]

Yang, L. J., & Jiang, Y. L. (2020). Innuence of relative deprivation on problematic mobile social media use: The mediating role of self-esteem. China Journal of Health Psychology, 28(6), 929–933. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2020.06.029 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, J., Ming, X., Wang, Z., & Adams, S. M. (2017). Are sex effects on ethical decision-making fake or real? A meta-analysis on the contaminating role of social desirability response bias. Psychological Reports, 120(1), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294116682945 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zerbe, W. J., & Paulhus, D. L. (1987). Socially desirable responding in organizational behavior: A reconception. Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1987.4307 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools