Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Social anxiety and problematic Internet use in college students: The moderating role of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help

1 Mental Health Education Center, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, 510006, China

2 Psychological Counseling and Guidance Center, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanchang, 330004, China

3 College of Humanities, Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine, Nanchang, 330004, China

* Corresponding Author: Lan Luo. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 231-239. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065770

Received 20 May 2024; Accepted 01 December 2024; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use in college students, and how it is moderated by attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Participants were 1451 Chinese college students (female = 60.2%; mean age = 19.85 years, SD = 1.89 years). They completed the Interaction Anxiousness Scale, the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form, and the Problematic Internet Use Scale. The results revealed that college students with higher social anxiety reported greater severity of problematic Internet use. Moreover, students with negative attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help also reported greater severity of problematic Internet use. Notably, attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help moderated the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use in college student, such that the relationship was weakened when attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help was positive. These findings suggest a need for student development and support programs for promoting openness to seeking professional psychological help if with problematic Internet use from social anxiety.Keywords

In the digital age, while the growing reliance on the Internet has brought numerous benefits to various aspects of life, it has also contributed to the rise of problematic Internet use, particularly among college students (Romero-López et al., 2021). Global estimates indicate that approximately 14.22% of the general population experiences problematic Internet use, with the rate among young adults climbing as high as 68% (Labrague, 2023).

Problematic Internet use (PIU) refers to long-term and unrestrained Internet use that negatively affects individuals’ mental health, social adaptation, study and work, and is also called Internet addiction, pathological Internet use or excessive Internet use (Beard & Wolf, 2001). Excessive Internet use is associated with poor social outcomes such as the decrease of happiness level (Bernardi & Pallanti, 2009), emotional disorders (Longstreet et al., 2019), and even involvement in illegal or criminal behaviors (De Leo & Wulfert, 2013). Social anxiety would be associated with problematic Internet use (Lee & Stapinski, 2012; Sun et al., 2024; Yan et al., 2014), and fewer studies have explored the factors that moderate this relationship among college students. Hence, this study aims to investigate the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use among college students and explore potential moderating factors that may influence this relationship.

Social anxiety and problematic Internet use

Social anxiety involves feelings of nervousness or fear, leading individuals to avoid social interactions in various interpersonal situations (Morrison & Heimberg, 2013). This avoidance can drive socially anxious individuals to turn to the Internet as a means of escaping face-to-face interactions, which often results in overuse or problematic Internet behaviors (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014).

Besides, social anxiety can contribute to mobile phone addiction (Zhou et al., 2021), depression (Gilbert, 2000), sleep disorder (Horenstein et al., 2019) and even deliberate self-harm (Hamdan-Mansour et al., 2022). College students are particularly vulnerable to these consequences, especially in the absence of professional mental health support, which can seriously affect both their physical and mental well-being.

Risk factors for problematic Internet use among college students, include stressful life events (Yan et al., 2014), interpersonal distress (Wongpakaran et al., 2021), academic stress (Jun & Choi, 2015) and negative emotions (Hong et al., 2021). According to the compensatory Internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014) individuals may turn to the Internet as a coping mechanism to alleviate negative emotions or stress. Therefore, social anxiety may indeed predict problematic Internet use among college students.

Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help as a moderator

Admittedly, college students with similar levels of social anxiety may have different levels of problematic Internet use, perhaps by their attitude to seek professional help. Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help refer to an internal reaction tendency of whether an individual is willing to seek professional help and support when facing difficulties and pressures, the more positive an individual’s attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, the more likely they are to engage in professional help-seeking behavior (Fischer & Turner, 1970; Mojtabai et al., 2016; Nam et al., 2013). Individuals who are willing to seek professional psychological help are usually more effective in buffering negative emotions and reducing the occurrence of problem behaviors (Seligman, 1995; Topkaya, 2021).

According to the buffer theory of social support (Alloway & Bebbington, 1987), attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, as a form of perceived social support, can effectively buffer against social anxiety and reduce individuals’ excessive use of the Internet (Sahranç et al., 2018; Seyfi et al., 2013). In addition, the risk-protective model also assume that protective factors can attenuate or buffer the adverse effects of risk factors (Hollister-Wagner et al., 2001). According to this model, protective factors (e.g., positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help) can buffer the impact of risk factors (e.g., social anxiety) on problematic Internet use among college students. In other words, college students with high level of social anxiety can still exhibit fewer problematic Internet use behaviors if they have positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Thus, attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help may play a moderating role in the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use among college students.

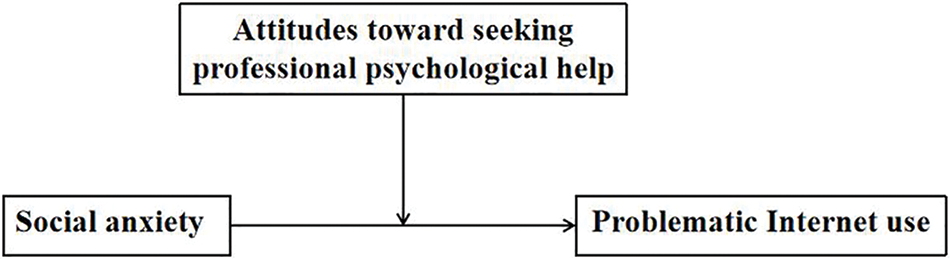

We constructed a moderated model (see Figure 1) to examine the interrelationships between social anxiety, problematic Internet use, and attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help in college students. Specifically, the current study has two aims: (i) To examine whether social anxiety positively predicts problematic Internet use and whether attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help negatively predicts problematic Internet use among college students.

Figure 1: The proposed moderated model

(ii) To explore whether attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help moderates the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use among college students.

Accordingly, we tested the following hypotheses:

H1: Social anxiety predicts higher problematic Internet use while attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help predicts lower problematic Internet use among college students.

H2: Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help moderates the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use among college students for lower risk for problematic Internet use.

College students with social anxiety are more likely to use the Internet to seek comfort and satisfaction, compensating for their difficulties in social interactions. Understanding both the risk factors and protective factors that influence this association is crucial for designing effective interventions to reduce problematic Internet use and promote better mental health outcomes among college students.

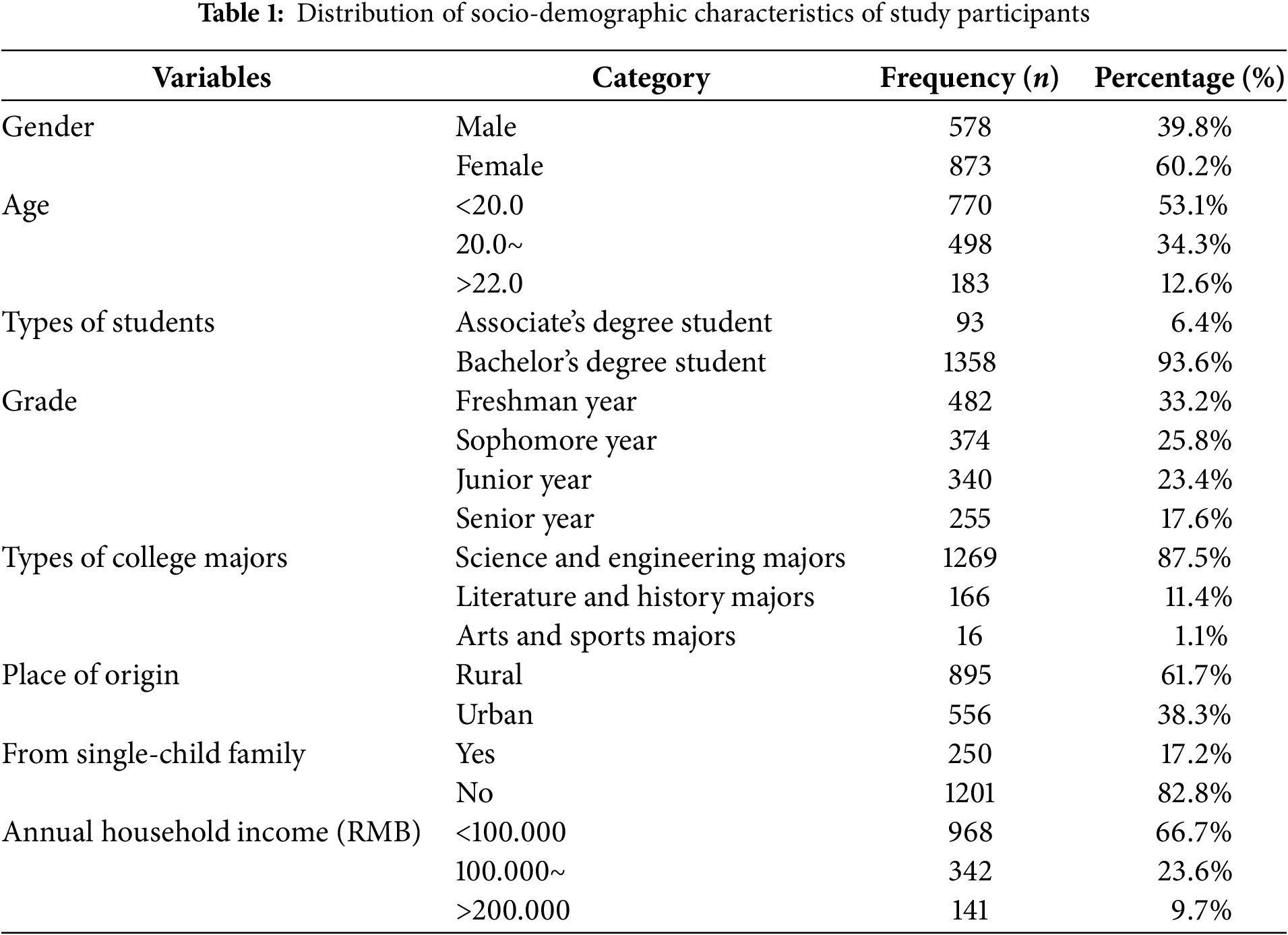

Participants were 1451 Chinese college students of whom 578 (39.8%) were male and 873 (60.2%) were female. Their ages ranged from 17 to 25 years old (M = 19.85 years, SD = 1.89 years). Table 1 presents further socio-demographic information.

Participants self-reported their socio-demographic information including gender, age, types of students, grade, types of college majors, place of origin, single-child situation and annual household income. Further, they completed the Interaction Anxiousness Scale (Leary, 1983; Peng et al., 2004), the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form (Fang et al., 2019; Fischer & Farina, 1995), and the Problematic Internet Use Scale (Li et al., 2010; Young, 1998). These are described next.

This study used the Interaction Anxiousness Scale (IAS) compiled by Leary (1983) and revised by Peng et al. (2004) to measure the social anxiety of college students. This scale comprises 15 items, of which items 3, 6, 10, and 15 are reverse scored. For each item, respondents are asked to indicate the “degree to which the statement is characteristic or true of you” on a 5-point scale: 1 (not at all), 2 (slightly), 3 (moderately), 4 (very), or 5 (extremely) characteristic. The total score ranges from 15 to 75, with higher scores indicating greater social anxiety. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for scores from the IAS was 0.874.

Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help

This study used the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale-Short Form (ATSPPH-SF) compiled by Fischer & Farina (1995) and revised by Fang et al. (2019) to measure the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help of college students. This scale comprises two dimensions: openness to seeking treatment for emotional problems, value and need in seeking treatment. Each dimension consists of 5 items, straight items (e.g., items 1, 3, 5, 6 and 7) are scored 3-2-1-0, and reversal items (e.g., items 2, 4, 8, 9 and 10) 0-1-2-3, respectively, for the response alternatives agree, partly agree, partly disagree, and disagree. The total score ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.774 for the ATSPPH-SF scores overall, 0.777 for openness to seeking treatment for emotional problems, 0.772 for value and need in seeking treatment.

This study used the Problematic Internet Use Scale (PIU) compiled by Young (1998) and revised by Li et al. (2010) to measure the problematic Internet use of college students. Respondents to the 10 items are given on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 6 (very true). The total score ranges from 10 to 60, with higher scores representing higher level of problematic Internet use. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha for scores from the PIU was 0.884.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine. All participants provided individual informed consent prior to taking part in the study. Participants had the choice to access an electronic questionnaire via a QR code or to complete a paper version. Participants were informed that they could withdraw from the survey at any time without penalty. Additionally, they were reassured that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential, and that the data collected would be used solely for research purposes.

This study used SPSS 25.0 and the supplemental PROCESS macro 4.2 for data analysis (Hayes, 2017). Firstly, because all the data were self-reported by participants, common method bias is a possibility. Harman’s single-factor test was used to test for common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The result showed that the contribution rate of the single factor was 23.51%, which did not exceed the critical standard of 40% (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986; Tang & Wen, 2020), proving no serious common method bias in this study. Secondly, descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were calculated among the study variables. Finally, the hierarchical regression analysis and PROCESS macro (Model 1) for SPSS were applied to examine the moderating role of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help.

Notably, the socio-demographic variables (gender, age, types of students, grade, types of college majors, place of origin, single-child situation and annual household income) were controlled when we examine the moderating effect. In the meanwhile, for the substantive analysis addressing the research questions, we analyzed for the covariance arising between the interaction term and the study variables, the remaining variables before hierarchical regression analysis. Except for the control variables, we first standardized into Z-score and formed the interaction term (Social anxiety × ATSPPH) before hierarchical regression analysis. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant (two tailed).

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

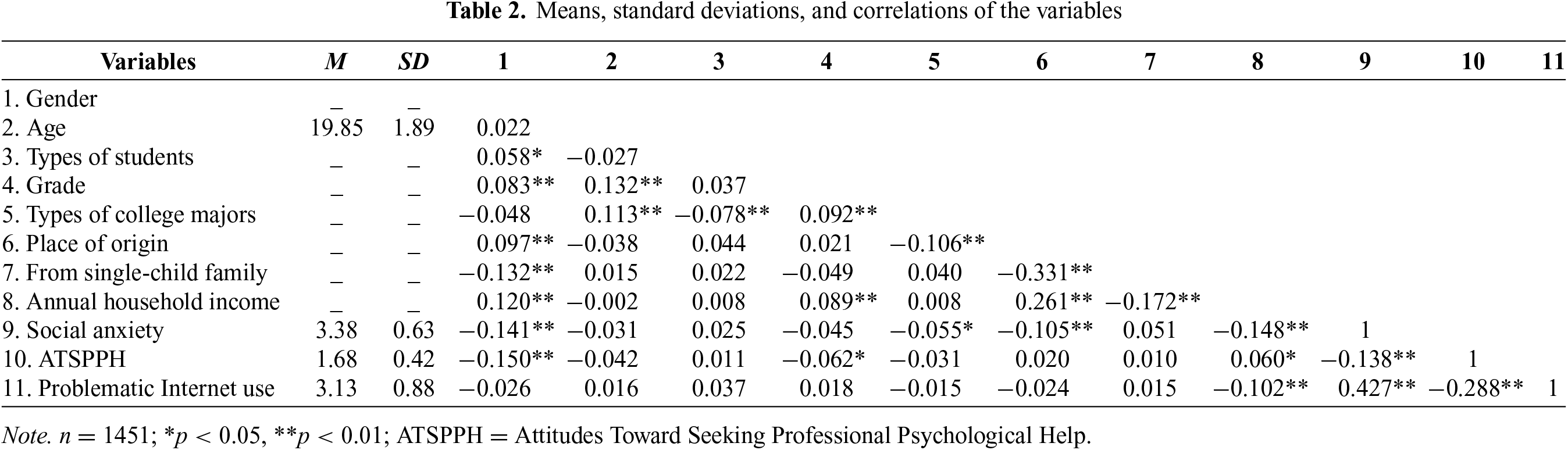

Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables. Social anxiety was positively correlated with problematic Internet use (r = 0.427, p < 0.01), but negatively correlated with attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help (r = −0.138, p < 0.01). Additionally, attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help was negatively associated with problematic Internet use (r = −0.288, p < 0.01).

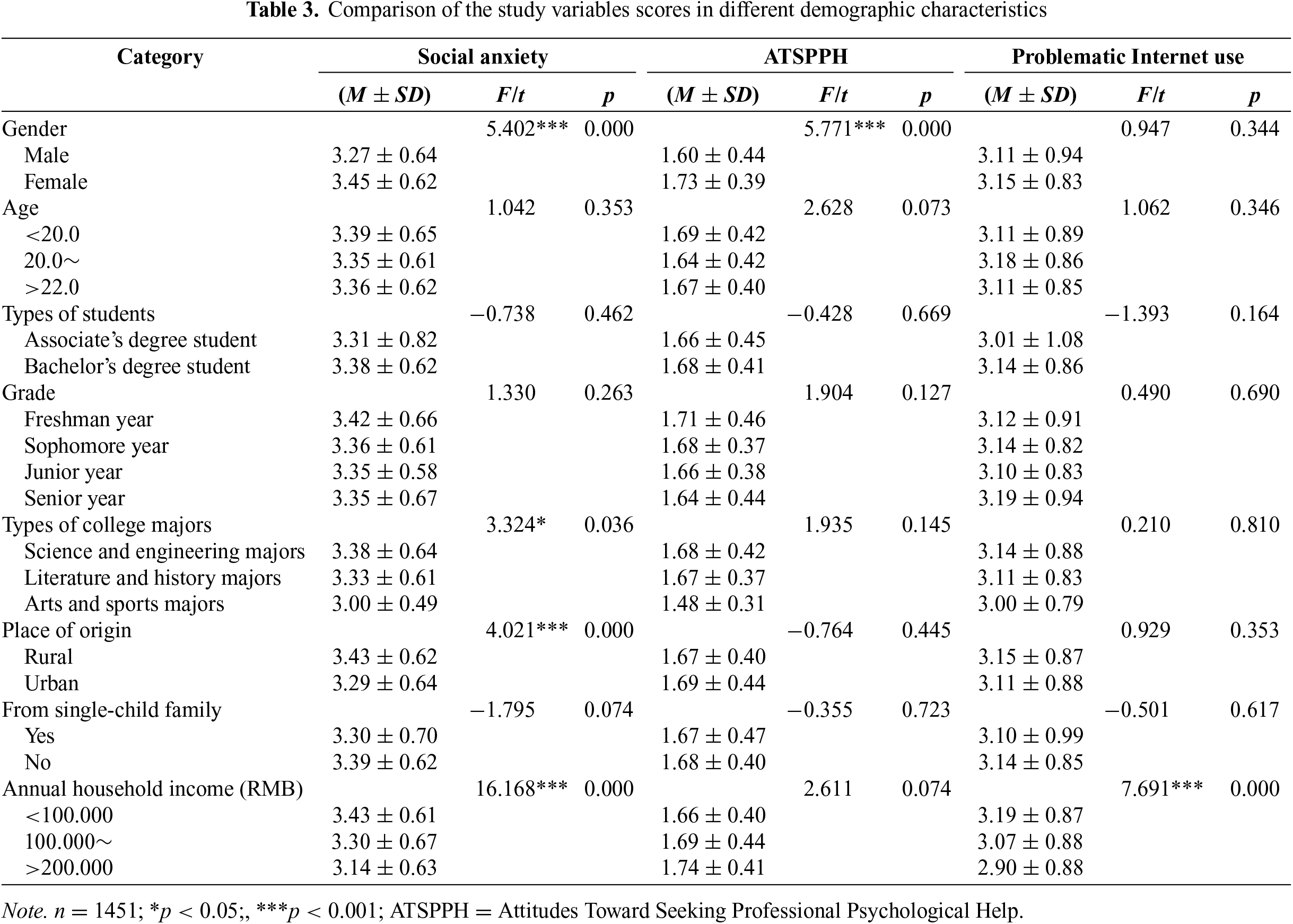

Table 3 shows the comparison of the study variables scores in different demographic characteristics. As the results show, the scores of social anxiety and attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help of female students were significantly higher than that of male students. The social anxiety scores of students majoring in science and engineering, literature and history were significantly higher than those of students majoring in arts and sports. Rural students obtained higher social anxiety score than urban students. Students with annual family income (<100.000) obtained higher social anxiety score than those with annual family income (100.000∼) and (>200.000), and those with annual family income (100.000∼) obtained higher social anxiety scores than those with annual family income (>200.000). In addition, students with annual family income (<100.000) obtained higher problematic Internet use score than those with annual family income (100.000∼) and (>200.000).

Professional psychological help seeking moderation

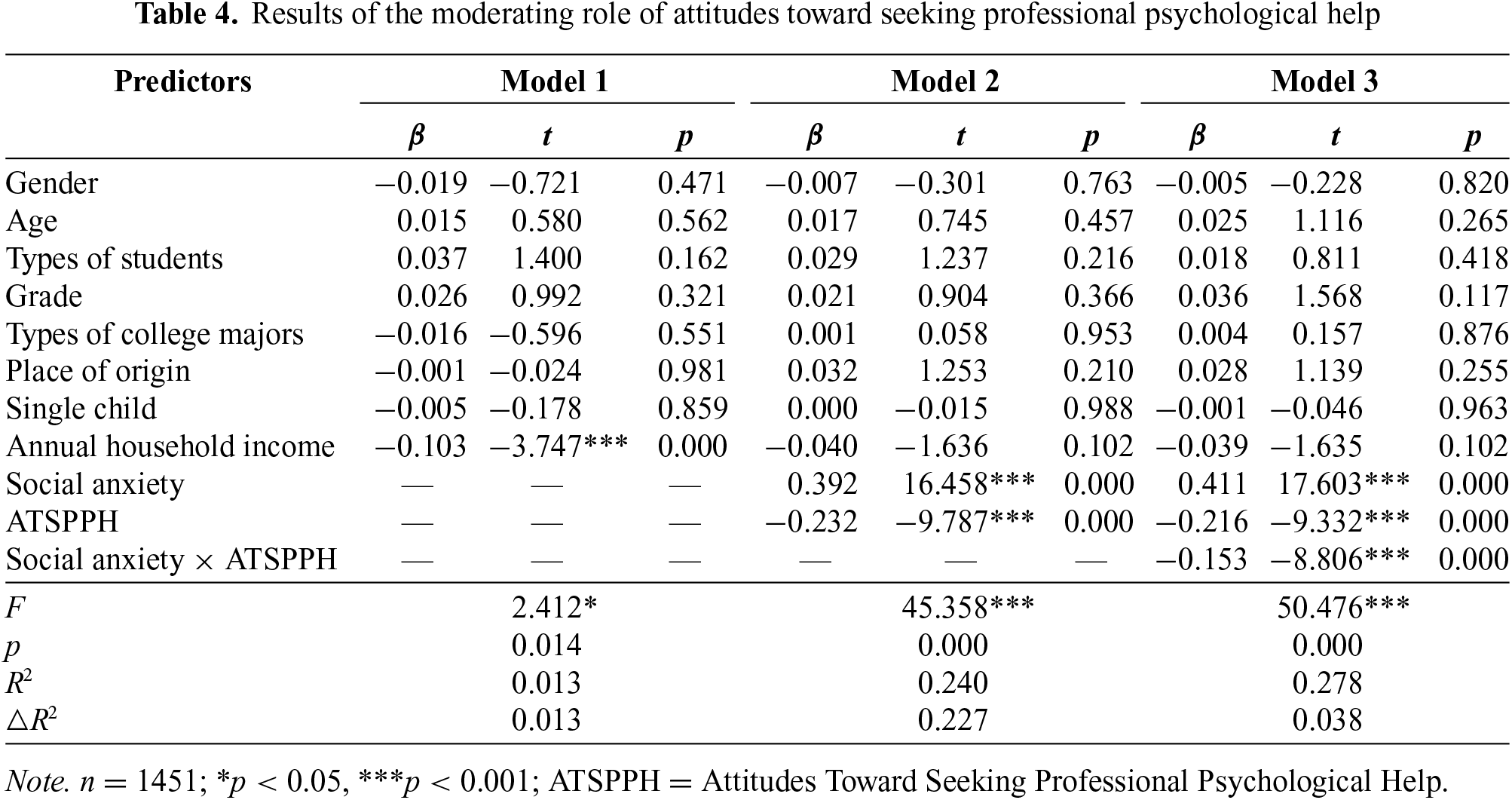

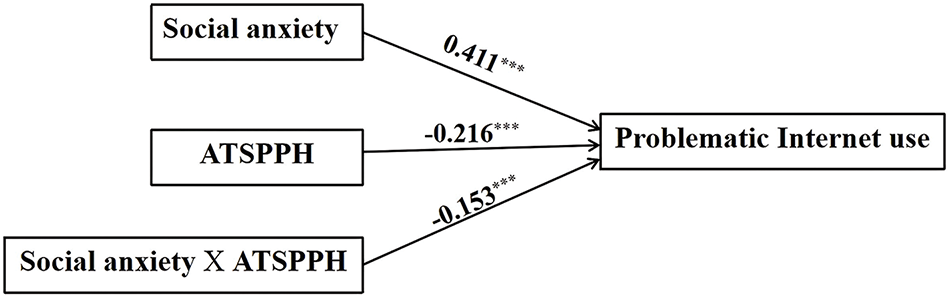

Table 4 presents the results of the moderating role of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. In model 1, only annual household income was significantly related to problematic Internet use (β = −0.103, t = −3.747, p < 0.001). In model 2, social anxiety had a significant positive prediction effect on problematic Internet use (β = 0.392, t = 16.458 p < 0.001), while attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help had a significant negative prediction effect on problematic Internet use (β = −0.232, t = −9.787, p < 0.001). In model 3, the interaction term (Social anxiety × ATSPPH) was significantly associated with problematic Internet use (β = −0.153, t = −8.806, p < 0.001), and the effect size of the moderation effect was 0.038, suggesting that attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help could moderate the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use. Accordingly, H1 (social anxiety predicts higher problematic Internet use while attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help predicts lower problematic Internet use among college students) and H2 (attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help moderates the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use among college students for lower risk for problematic Internet use) were supported (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Test values for the moderated model. Note. n = 1451; ***p < 0.001; ATSPPH = Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help.

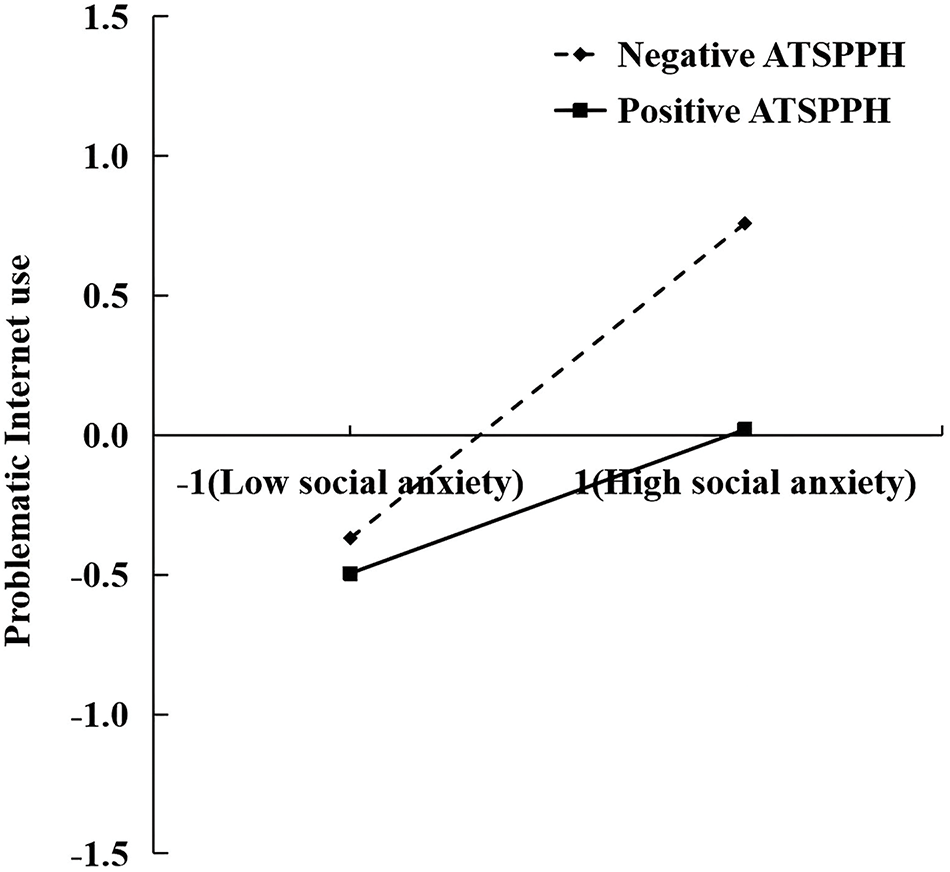

To visualize the interaction pattern, we adopted the PROCESS macro (Model 1) by Hayes (2017) to conduct a simple slope test. The simple slope figures of social anxiety against problematic Internet use under negative and positive (±1 SD from the mean) attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help was plotted (see Figure 3). Simple slope test showed that social anxiety was significantly and positively associated with problematic Internet use for college students with both negative (Z = −1, βsimple = 0.564, t = 18.605, p < 0.001) and positive (Z = 1, βsimple = 0.258, t = 9.258, p < 0.001) attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, but the correlation was significantly stronger in the former. In another word, college students with negative attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help more easily experienced problematic Internet use than those with positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help.

Figure 3: Moderating effect of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help on the relationship between social anxiety and problematic Internet use. Note. ATSPPH = Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help.

The results of this study revealed that social anxiety can positively predict problematic Internet use among college students. This result is consistent with previous research findings (Lee & Stapinski, 2012; Onyekachi et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2021) and support the compensatory Internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014), that is, college students experiencing social anxiety are more inclined to utilize the Internet as a means of seeking compensation and satisfaction. Additionally, the mood enhancement hypothesis (Bryant & Zillmann, 1984) suggests that individuals may regulate their Internet usage based on their emotional states, with negative emotions potentially leading to problematic Internet use. It can be seen that the more anxious college students are about social interactions, the greater the probability of problematic Internet use occurring. Social anxiety is indeed an important risk factor for problematic Internet use.

The study findings indicated that attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help is associated with lower risk for social anxiety and problematic Internet use among college students. Specifically, compared with college students with positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help, college students with negative attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help may be more prone to problematic Internet use after experiencing social anxiety. This result support the buffer theory of social support (Alloway & Bebbington, 1987) and the risk-protective model (Hollister-Wagner et al., 2001). The attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help is positively correlated with social support (Huang et al., 2023; Jung et al., 2017; Nam et al., 2013). Individuals who hold a positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help typically have a stronger social support system, and they consider seeking professional psychological help as an effective coping strategy (Nam et al., 2013; Seyfi et al., 2013). Even if there are risk factors (e.g., social anxiety), protective factors (e.g., positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help) can still inhibit the occurrence of bad psychological behavior problems and protect individual mental health (Hollister-Wagner et al., 2001; Masten, 2001). Therefore, the impact of social anxiety on problematic Internet use among college students weakens with the increase of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help.

Implications for student counselling and development

It is worth noting that our findings have important practical implications. Firstly, previous studies have found that many college students with problematic Internet use lack social and coping skills (Labrague, 2023; Romero-López et al., 2021). Therefore, colleges can offer targeted courses (e.g., health psychology, interpersonal skills, and Internet addiction interventions) to help students master effective coping strategies for social anxiety and problematic Internet use.

Secondly, colleges can also establish a complete psychological early warning system (e.g., regular campus-wide mental health surveys) to identify and intervene college students who have problems related to high social anxiety and negative attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help in time (Eisenberg et al., 2013; Topkaya, 2021). Carrying out campus-wide mental health surveys are helpful to raise college students’ mental health awareness and encourage them to actively seek professional psychological help when they encounter mental health issues (Lipson et al., 2019).

Finally, since positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help is beneficial in alleviating social anxiety and problematic Internet use, the government and education bureau may provide more development activities centered around mental health to college students to improve their attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. For instance, strengthening mental health education to reduce the stigma regarding mental health (Jung et al., 2017; Shim et al., 2022), providing a variety of psychological counseling services (e.g., individual counseling, group counseling, telephone counseling, Internet counseling) (Pace et al., 2018), and establish home-school cooperation mechanisms to enhance social support. These efforts aim to improve the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help and ultimately safeguard the mental well-being of college students (Jung et al., 2017; Stormshak et al., 2009).

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations that future research could seek to address. First, because we adopted a cross-sectional design, causal relationships cannot be inferred from the results. Future research could use a longitudinal or experimental design to reveal causation in the moderated model. Second, all variables were assessed via self-report measures, which might affect the validity of the present study. Future studies should use multiple assessment techniques to investigate the relationships between the study variables. Third, despite the large sample size, this study was conducted in a sample of Chinese college students reasonably homogeneous in culture. Future studies should extend the findings in different cultural contexts. Despite these limitations, however, the current study has several theoretical and practical contributions. From a theoretical perspective, this study further extends previous research by examining the moderating role of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. From a practical perspective, results from this study may be used to examine the efficacy of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help in mitigating the positive effect of social anxiety on problematic Internet use.

In conclusion, this study’s findings indicate that social anxiety can increase risk for problematic Internet use by college students. However, students’ attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help in this relationship may be an anti-dote to their risk for social anxiety and problematic Internet use, with positive attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help playing a key role in effectively reducing both issues among college students. Accordingly, student development and support programs for reducing social anxiety and improving attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help can effectively alleviate the problematic Internet use of college students.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to all college students who participated in the study.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by Science and Technology Research Project of Jiangxi’ Department of Education (GJJ2200929) and Key Project of Guangzhou Psychological Society (2023GZPS05).

Author Contributions: Ronghua Wen and Lan Luo designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Ronghua Wen and Shiping Luo collected and analyzed the data. Tianlin Chen and Meng Fan supervised and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Lan Luo, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangxi University of Chinese Medicine. All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Alloway, R., & Bebbington, P. (1987). The buffer theory of social support—a review of the literature. Psychological Medicine, 17(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700013015 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Beard, K. W., & Wolf, E. M. (2001). Modification in the proposed diagnostic criteria for internet addiction. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 4(3), 377–383. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493101300210286 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bernardi, S., & Pallanti, S. (2009). Internet addiction: A descriptive clinical study focusing on comorbidities and dissociative symptoms. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 50(6), 510–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.11.011 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bryant, J., & Zillmann, D. (1984). Using television to alleviate boredom and stress: Selective exposure as a function of induced excitational states. Journal of Broadcasting, 28(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838158409386511 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

De Leo, J. A., & Wulfert, E. (2013). Problematic Internet use and other risky behaviors in college students: An application of problem-behavior theory. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030823 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Eisenberg, D., Hunt, J., & Speer, N. (2013). Mental health in American colleges and universities: Variation across student subgroups and across campuses. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827ab077 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fang, S., Yang, B., Yang, F., & Zhou, Y. (2019). Study on reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help scale-short form for community population in China. Chinese Nursing Research, 33(14), 2410–2414. [Google Scholar]

Fischer, E. H., & Farina, A. (1995). Attitudes toward seeking professional psychologial help: A shortened form and considerations for research. Journal of College Student Development, 36(4), 368–373. [Google Scholar]

Fischer, E. H., & Turner, J. I. (1970). Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 35(1, Pt.1), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0029636 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gilbert, P. (2000). The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 7(3), 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1099-0879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hamdan-Mansour, A. M., Alzayyat, A. A., Hamaideh, S. H., Rafaiah, M. -Q. B., Al Jammal, O. L., & Hamdan-Mansour, L. A. (2022). Predictors of deliberate self-harm among university students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(5), 2993–3005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00561-8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford publications. Retrieved from: https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=6uk7DwAAQBAJ&hl=zh-CN&num=10. [Google Scholar]

Hollister-Wagner, G. H., Foshee, V. A., & Jackson, C. (2001). Adolescent aggression: Models of resiliency. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 445–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02050.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hong, M., Dyakov, D. G., & Zheng, J. (2021). The influence of self-identity on social support, loneliness, and internet addiction among Chinese college students. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(3), 242–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2021.1927353 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Horenstein, A., Morrison, A. S., Goldin, P., ten Brink, M.,, Gross, J. J., & Heimberg, R. G. (2019). Sleep quality and treatment of social anxiety disorder. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 32(4), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2019.1617854 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Huang, S., Xiao, M., Hu, Y., Tang, G., Chen, Z., Zhang, L., Fu, B., & Lei, J. (2023). Attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help among Chinese pregnant women: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 322, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.034 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jun, S., & Choi, E. (2015). Academic stress and Internet addiction from general strain theory framework. Computers in Human Behavior, 49(2), 282–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jung, H., von Sternberg, K., & Davis, K. (2017). The impact of mental health literacy, stigma, and social support on attitudes toward mental health help-seeking. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 19(5), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623730.2017.1345687 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). Problematizing excessive online gaming and its psychological predictors. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.017 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Labrague, L. J. (2023). Problematic internet use and psychological distress among student nurses: The mediating role of coping skills. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 46(1), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2023.08.009 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Leary, M. R. (1983). Social anxiousness: The construct and its measurement. Journal of Personality Assessment, 47(1), 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4701_8 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lee, B. W., & Stapinski, L. A. (2012). Seeking safety on the internet: relationship between social anxiety and problematic internet use. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(1), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.11.001 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, D., Zhang, W., Li, X., Zhen, S., & Wang, Y. (2010). Stressful life events and problematic Internet use by adolescent females and males: A mediated moderation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1199–1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.031 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lipson, S. K., Lattie, E. G., & Eisenberg, D. (2019). Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800332 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Longstreet, P., Brooks, S., & Gonzalez, E. S. (2019). Internet addiction: When the positive emotions are not so positive. Technology in Society, 57, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.12.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mojtabai, R., Evans-Lacko, S., Schomerus, G., & Thornicroft, G. (2016). Attitudes toward mental health help seeking as predictors of future help-seeking behavior and use of mental health treatments. Psychiatric Services, 67(6), 650–657. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500164 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Morrison, A. S., & Heimberg, R. G. (2013). Social anxiety and social anxiety disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185631 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Nam, S. K., Choi, S. I., Lee, J. H., Lee, M. K., Kim, A. R., & Lee, S. M. (2013). Psychological factors in college students’ attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help: A meta-analysis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029562 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Onyekachi, B. N., Egboluche, F. O., & Chukwuorji, J. C. (2022). Parenting style, social interaction anxiety, and problematic internet use among students. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(1), 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2021.2002030 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pace, K., Silk, K., Nazione, S., Fournier, L., & Collins-Eaglin, J. (2018). Promoting mental health help-seeking behavior among first-year college students. Health Communication. 33(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1250065 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peng, C., Gong, Y., & Zhu, X. (2004). The applicabiliy of interaction anxiousness scale in Chinese undergraduate students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 1, 39–41. [Google Scholar]

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Lee, J. -Y., & Podsakoff, N. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Romero-López, M., Pichardo, C., De Hoces, I., & García-Berbén, T. (2021). Problematic internet use among university students and its relationship with social skills. Brain Sciences, 11(10), 1301. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11101301 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sahranç, Ü., Çelik, E., & Turan, M. E. (2018). Mediating and moderating effects of social support in the relationship between social anxiety and hope levels in children. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(4), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9855-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Seligman, M. E. P. (1995). The effectiveness of psychotherapy: The consumer reports study. American Psychologist, 50(12), 965–974. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.50.12.965 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Seyfi, F., Poudel, K. C., Yasuoka, J., Otsuka, K., & Jimba, M. (2013). Intention to seek professional psychological help among college students in Turkey: Influence of help-seeking attitudes. BMC Research Notes, 6(1), 519. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-519 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Shim, Y. R., Eaker, R., & Park, J. (2022). Mental health education, awareness and stigma regarding mental illness among college students. Journal of Mental Health & Clinical Psychology, 6(2), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.29245/2578-2959/2022/2.1258 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stormshak, E. A., Connell, A., & Dishion, T. J. (2009). An adaptive approach to family-centered intervention in schools: Linking intervention engagement to academic outcomes in middle and high school. Prevention Science, 10(3), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-009-0131-3 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sun, Y., He, J., Li, Y., Yu, L., Li, W., et al. (2024). Social anxiety and problematic smartphone use in Chinese college students: The mediating roles of coping style and the moderating role of perceived friend support. Current Psychology, 43(19), 17625–17634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05699-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tang, D., & Wen, Z. (2020). Statistical approaches for testing common method bias: Problems and suggestions. Journal of Psychological Science, 43(1), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200130 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Topkaya, N. (2021). Predictors of attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help among Turkish college students. Children and Youth Services Review, 120(5), 105782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105782 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wongpakaran, N., Wongpakaran, T., Pinyopornpanish, M., Simcharoen, S., & Kuntawong, P. (2021). Loneliness and problematic internet use: Testing the role of interpersonal problems and motivation for internet use. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 447. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03457-y [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yan, W., Li, Y., & Sui, N. (2014). The relationship between recent stressful life events, personality traits, perceived family functioning and internet addiction among college students. Stress and Health, 30(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2490 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Young, K. S. (1998). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1(3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1998.1.237 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhou, H. -L., Jiang, H. -B., Zhang, B., & Liang, H. -Y. (2021). Social anxiety, maladaptive cognition, mobile phone addiction, and perceived social support: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(3), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2021.1927354 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools