Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Building the profession of psychological counselling in Ethiopia—achievements, challenges, and future directions

1 Department of Psychology, Rhodes University, Makhanda, 6140, South Africa

2 Department of Psychology, Hawassa University, Hawassa, P.O. Box 05, Sidama, Ethiopia

* Corresponding Author: Megan M. Campbell. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 277-285. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065771

Received 08 August 2024; Accepted 18 January 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

Mental healthcare in Ethiopia is underutilized due to a lack of resources and skilled practitioners. Psychological counselling offers unique intervention possibilities because of its focus on a wide range of mental health and social justice issues. This literature review tracks the historical development of the profession of psychological counselling in Ethiopia to establish what has been achieved to date and the development challenges. Key achievements include recognition of the profession by the Ministry of Education, growing public awareness, and increasing capacity of practitioners skilled in psychological counselling. Challenges include limited contextually relevant training, poor representation of the profession within Ministry of Health policies, poor public and government mental health literacy, and a lack of regulatory frameworks. Postgraduate training would benefit from more culturally, contextually, and linguistically appropriate evidence-based, indigenous psychology practices. The profession would benefit from engagement in government policy development that promotes mental health, and professional regulatory bodies to hold practitioners accountable to professional standards and ethical practice.Keywords

Ethiopia is the second most populated country in sub-Saharan Africa with an estimated 113.5 million people (UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), 2022). The country boasts a diversity of languages and over 60 different ethnic groups spread across twelve regional states. The estimated prevalence of common mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety and psychological distress in the general population is 21.58% with women reporting higher rates of mental illness than men (Kassa & Abajobir, 2018) Because Ethiopia is frequently hit by man-made and natural disasters (including wars, floods, drought and famine), malnutrition and preventable infectious disease are common (UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), 2022). One in every four Ethiopians is classified as absolutely poor, and only 51.8% of the adult population is literate (UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), 2022). While research has demonstrated that mental health problems have a direct impact on health and poverty, and that psychological treatment helps to break the cycle of poverty (World Health Organisation, 2010), mental illness is not currently given its due attention (Wondie, 2014). Access to and implementation of psychological diagnostic procedures and evidence-based intervention and treatment strategies are extremely limited (Zeleke et al., 2019). In fact Hughes et al. (2020) note that the 2015–2016 National Mental Health Strategy (of Ethiopia) estimated that only 40 psychiatrists, 461 psychiatric nurses, 14 psychologists and 3 social workers were servicing the mental health needs of the country, with a population estimated to exceed 85 million at the time.

Local explanatory models attribute mental health symptoms to religious, supernatural, and spiritual factors (Hughes et al., 2020), causing those afflicted to seek out support from close family members, local community healers like priests and other religious practitioners initially (Zeleke et al., 2019). Consequently, mental healthcare services are often considered a last resort (Bekele et al., 2009), particularly in more rural areas. Misunderstandings and inaccurate perceptions of mental health issues are reinforced by a lack of public awareness regarding emotional, psychological, and behavioral problems (Wandie, 2014). There is, however, emerging evidence recognizing the need for, acceptance and utilization of mental healthcare services in Ethiopia, particularly in primary care contexts in cities and urban settings (for example Lund et al., 2012), and the local adaptation and implementation of evidence-based interventions. See, for example the adaptation of a brief problem-solving therapy intervention for pregnant Ethiopian women living in Sodo managing depression and intimate partner violence (Keynejad et al., 2024) and the implementation of a client-centred psychosocial intervention for adolescents in Addis Ababa (Jani et al., 2016).

The historical development of psychological counselling in Ethiopia

In Ethiopia, psychological counselling, as an umbrella term, refers to counselling services that address emotional, psychological and behavioural problems, provided by a trained professional. Depending on the level of training and expertise, this professional may provide short-term counselling interventions to address personal, social and psychological problems (Likisa & Tura, 2020); career guidance interventions to improve academic and scholastic performance, and aid in career development (Getachew, 2019); and more complex interventions that focus on emotional, social, vocational and educational health, developmental and organizational concerns for society (Kebede & Wubshet, 2018). Psychological counselling includes undergraduate training courses in counselling; specialised postgraduate training at Master’s level to become a psychologist, and more sophisticated research-focused training at PhD level.

However, there is currently no formal register of psychological counsellors nationally or regulatory professional and ethics frameworks, making it difficult to clearly ascertain the size and scope of the discipline, and to protect the scope of practice of professionals trained at undergraduate and postgraduate levels (Zeleke et al., 2019). Disassa (2020) has called upon the Ethiopian Psychology Association to be a stronger presence in this regulatory space, particularly with regard to licensing and regulating professionals at national and regional levels to safeguard and legitimize professional service delivery in Ethiopia. But until regulatory practices are put in place, legitimizing the scope of practice and professional identity of psychological counselling, at various levels of training, remains a considerable challenge. As does differentiating these professionals from those who provide counselling services without formal training.

Furthermore, psychological counselling as a discipline in Ethiopia is deeply rooted in North American and European conceptualizations of wellness and distress, which are not always compatible with ideologies in local contexts (Swancott et al., 2014). Therefore, the use of counselling services may at times be viewed as fairly irrelevant, possibly even an overindulgence. This is particularly relevant in Ethiopia where people face a host of social, political, and economic challenges, and mental health services are perceived as less urgent in comparison with other societal difficulties. However, seeking support from religious leaders, elders, relatives, and family members is deeply ingrained within Ethiopian cultures, as evidenced by their demonstrated history of valuing this practice. As a consequence, professional counselling support should be well endorsed, if provided in a culturally accessible and relevant manner. And a prominent and thriving psychological counselling profession would make a valuable contribution to the mental health and overall wellbeing of Ethiopian citizens.

The concepts of ‘psychology’ and ‘counselling services’ were first introduced in Ethiopia through the higher education system, when Haile Selassie I University College (known today as Addis Ababa University) began offering counselling psychology courses, taught by an American scholar, Dr. David Cox from the University of Utah, in the 1960s (Abdi, 1998). This coursework gradually expanded into a focus on career counselling (Zeleke et al., 2019) and professional counselling services were offered in local secondary schools, typically by American volunteers working as high school teachers (Kebede & Wubshet, 2018). But Abdi (1998) argues that this American style of counselling was not well received because of cultural incompatibility. Barriers included the challenges of integrating an American approach towards the framing of psychological distress into an Ethiopian context, and finding appropriate indigenous Ethiopian language equivalent vocabulary to validate American conceptualizations of how psychological distress presents and is experienced (Kirmayer & Swartz, 2013). These challenges likely contributed significantly to creating barriers to service utilization. Many Ethiopians still view mental health problems as a curse from God and much stigma is attached to seeking help for common mental disorders like depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems (Zeleke et al., 2019).

The Department of Psychology opened at Addis Ababa University in 1974, with the intention of training school psychologists (Kebede & Wubshet, 2018). Soon, psychological counselling training expanded from a few courses offered at undergraduate level (Abdi, 1998) to an independent, postgraduate programme. Over time the department began producing Ethiopian graduates who became psychological counsellors, career counsellors, counselling psychologists, lecturers, and researchers, assisting with the acculturation of psychological counselling into different Ethiopian sectors (Abdi, 1998). Postgraduate counselling psychology programmes spread to other universities across Ethiopia, including Hawassa University in the Sidama region of Southern Ethiopia, Jimma University in Southwestern Ethiopia, Wolaita Sodo and Dilla University in Southern Ethiopia (Woldie, 2021). Later, PhD programmes were established at Jimma and Addis Ababa Universities. However, the discipline struggled to establish its own indigenous identity and practice, and continues to draw heavily on North American influences (Kebede & Wubshet, 2018).

Taking this complex history into consideration, the authors conducted a literature review to establish: 1) what has been achieved in the field of psychological counselling in Ethiopia to date? and 2) What have been the challenges/barriers to the profession’s development?

Exploratory review. The review included documents that held historical significance, relevance to the research question, and representativeness. Digital databases (Google Scholar, PubMed, and Google Search) were used to search and retrieve documents from 1998 to 2023, using the keywords: “Psychological Counselling”; “Counselling Psychology”; “Guidance and Counselling”, “Mental Health” and “Ethiopia”. Sources encompassed empirical research in peer-reviewed journals, books, dissertations, and policy documents in both English and the Amharic languages. Books were accessed from university libraries, journal articles and theses from online databases, and policy documents from ministry archives.

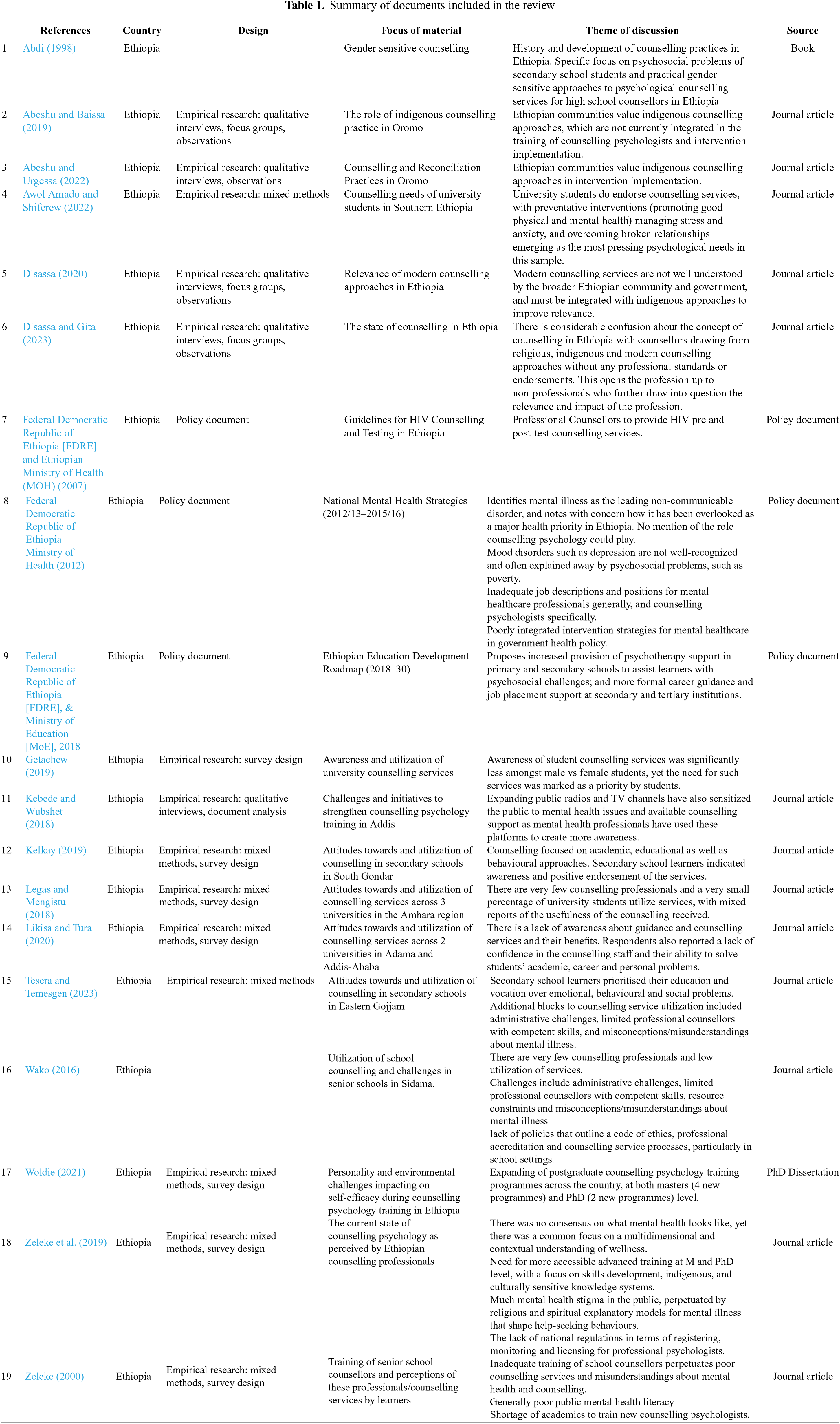

Data extraction protocol. A data extraction protocol was developed and guided data extraction. The data extraction process focused on the themes outlined in the research questions viz. developments and achievements in the field of psychological counselling in Ethiopia, and challenges and barriers to the profession’s development. To maintain the quality of the review, the first (AJ) and third (MC) authors evaluated each article independently to assess whether the selected materials aligned with the aims of the review. All non-English/Amharic manuscripts and purely medical studies were excluded from the review. After initial screening, 19 sources were included for review and analyzed. Procedures involved scanning printed books, screening titles and abstracts, thematizing discussions, and manual data extraction.

Data synthesis. The focus was on the quality of evidence rather than quantity, with the first (AJ) and third (MC) authors reviewing documents to identify similarities, differences, and patterns based on the discussion themes. Results are summarized in Table 1.

Achievements within the discipline

Three important achievements emerge from the available literature pertaining to establishing the professional identity and practice of psychological counselling in Ethiopia. First, psychological counselling has been formally recognized by Teferra et al. (2018), who aims to increase school-based counselling services nationwide. These services intend to include the provision of psychotherapy support in primary and secondary schools to assist learners with psychosocial challenges, and more formal career guidance and job placement support at secondary and tertiary institutions (Teferra et al., 2018). This has been an important step in recognizing the value that psychological counselling plays within the education sector. Early experiences of psychosocial support will also familiarize Ethiopian youth with counselling services, demystifying the practice, and hopefully, improving mental health literacy.

Second, there is growing public awareness and acceptance of the counselling services in some parts of Ethiopia, particularly in schools and universities. For example, in South Gondar, secondary school pupils demonstrate both awareness and positive endorsements of counselling services available at their schools (Kelkay, 2019). In Eastern Gojjam, pupils reported prioritizing their education and vocational needs, wanting counselling support to focus on these aspects over their emotional, behavioural, and social problems (Tesera & Temesgen, 2023). Within universities, Awol Amado and Shiferew (2022) found that students valued the opportunity to access preventative mental health services that promoted good physical and mental health, as well as interventions that assisted with stress management, anxiety and overcoming broken relationships. These are useful understandings of the growing psychological needs identified by Ethiopian pupils and students that could be the focus of future interventions. Expanding public radio and TV channels have also sensitized the public to mental health issues and available counselling support as mental health professionals have used these platforms to create more awareness (Kebede & Wubshet, 2018).

Third, the profession of Ethiopian psychological counselling is growing. Woldie (2021) documents the expansion of postgraduate counselling psychology training programmes from a single course in the 1970’s to four postgraduate professional master’s programmes and two PhD programmes, to accommodate demand, in line with government directives for massification of higher educational institutes. As of 2024, there are at least 7 postgraduate training programmes in counselling psychology available across the country. With increasing graduates, Janetius et al. (2013) note that the profession has seen a diversification of work placements beyond the education sector to government placements, NGOs, private practices and rehabilitation centers. During the 1980’s roles for psychological counsellors and psychologists, outside of the education sector, were focused on HIV/AIDS pre/post-test counselling (Abdi, 1998). However, the recent COVID-19 pandemic saw psychological counsellors playing a far broader role in psychosocial support and intervention work, boosting public awareness about the profession and further impacting positively on its expansion beyond the education sector (Kebede & Wubshet, 2018).

Despite the above-mentioned valuable achievements, four key challenges emerge from the current literature. First, limited opportunities for contextually and culturally relevant training hamper the professional growth of Ethiopian psychological counsellors and psychologists and the quality of the counselling interventions they provide. Indigenous counselling approaches are well established traditions amongst Ethiopian communities. For example, Abeshu and Baissa (2019) and Abeshu and Urgessa (2022) provide case studies of local indigenous counselling practices employed within the Oromo community to reduce conflict and promote reconciliation, that could be drawn upon to better inform intervention approaches locally. But cultural values are not typically incorporated into current higher institution curricular for the training of psychological counsellors and psychologists (Zeleke et al., 2019), yet there is a great need to integrate these indigenous knowledge systems into Ethiopian therapeutic interventions to make counselling practices more meaningful and relevant to local Ethiopian communities (Abeshu & Baissa, 2019; Abeshu & Urgessa, 2022). One particular limitation Abeshu and Baissa (2019) note is the negation of diverse language and multicultural perspectives in professional training curricular, intervention resources and subsequent implementation. Zeleke et al. (2019) add that postgraduate training continues to be limited to a few universities, heavily theory-based, with a noticeable absence of culturally sensitive, practical therapeutic materials, and skills-based training specific to the Ethiopian context. These important limitations reduce the relevance of counselling interventions and add to the considerable misunderstanding the public, and government, currently hold about psychological counselling and mental health services (Disassa, 2020).

Second, a lack of representation of psychological counselling outside of clinical psychology, within Ministry of Health policy denies the legitimate role of the profession within healthcare, apart from providing pre/post HIV test counselling services (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia [FDRE], Ethiopian Ministry of Health (MOH), 2007). This further hinders the development and contribution psychological counselling could make towards societal health and wellbeing. Examples include inadequate job descriptions and positions for mental healthcare professionals generally, and psychological counsellors and counselling psychologists specifically, within the Ministry of Health (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, 2012); poorly integrated intervention strategies for mental healthcare in government health policy (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, 2012); and a lack of collaboration across similar mental health disciplines such as psychiatry and social work (Zeleke et al., 2019).

Third, poor public and government mental health literacy and awareness restrict the growth of professional counselling services in healthcare settings. The National Mental Health Strategy for 2012–2015 (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, 2012) identified mental illness as the leading non-communicable disorder (with schizophrenia and depression out-ranking HIV/AIDS in more rural areas of Ethiopia), and noted how it has been overlooked as a major health priority in Ethiopia. Yet mental health stigma remains high, and is perpetuated by traditional religious and spiritual explanatory models that shape help-seeking behaviours (Zeleke et al., 2019). In school settings, a general lack of mental health knowledge and support by school administrators results in limited time and resources being made available for pupils to access these services (Kelkay, 2019). In university settings lack of awareness of the available counselling services (Getachew, 2019; Legas & Mengistu, 2018) and a lack of confidence in the counselling staff’s abilities to address students’ psychological problems and concerns (Likisa & Tura, 2020) appear to be barriers to service utilization. Disassa (2020) found that in addition to poor mental health literacy, counselling services are not well understood by the broader Ethiopian community and government, and must be integrated with indigenous approaches to improve their relevance. In a follow-up study Disassa and Gita (2023) found that there is considerable confusion about the concept of counselling in Ethiopia with mental health professionals drawing from religious, indigenous and more Eurocentric counselling approaches without any professional standards to guide their implementation. Zeleke et al. (2019) argue that these confusions about mental health and counselling interventions hinder the development of psychological counselling as an academic discipline and as a healthcare service.

Fourth, the lack of national regulations in terms of registering, monitoring and licensing for professional counsellors and psychologists in Ethiopia opens the profession up to abuse and exploitation by non-professionals who provide counselling services for a professional fee, without the necessary training, harming the reputation and credibility which the profession has been so diligently developing (Zeleke et al., 2019). Moreover, a lack of well-delineated professional boundaries between professional counsellors such as counselling psychologists and other fields of psychology or similar professions like social work and psychiatry creates considerable confusion amongst mental healthcare users. Within the profession, there is a lack of policies that outline a code of ethics, professional accreditation and counselling service processes, particularly in school settings (Wako, 2016). Zeleke et al. (2019) also stress that the lack of culturally relevant standards regarding ethics and professional practice hinders the development of the profession. For example, psychological counsellors employed in schools to provide psychosocial support and career guidance report that much of their time is taken up by administrative duties (Zeleke, 2000) and teaching of unrelated academic subjects (Disassa, 2020) rather than counselling-related services. Without strong policies, ethical standards and professional guidelines, psychological counsellors find it difficult to protect and promote their scope of practice and professional identity.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Psychological health is essential to effect social and economic change within Ethiopia and psychological counselling services offer an excellent vehicle to bring about better mental wellbeing. The formal recognition of psychological counsellors and counselling psychologists specifically, by the FDRE Ministry of Education, coupled with growing public awareness and acceptance of the counselling services in some parts of Ethiopia, and the growing numbers of Ethiopian psychological counsellors and psychologists being trained, have led to important achievements in the field. However, considerable challenges and barriers continue to undermine the development of the profession. These include: limited opportunities for contextually and culturally relevant training which hampers the professional growth of Ethiopian psychological counsellors and the quality of the counselling interventions they provide; a lack of representation of psychological counsellors, and specifically counselling psychology within FDRE Ministry of Health policies which denies the legitimate role of the profession within healthcare; poor public and government mental health literacy and awareness restricts the growth of professional counselling services; and the lack of national regulations opens the profession up to abuse and exploitation by non-professionals.

When envisioning future directions for the field of psychological counselling, it is important to highlight that Ethiopia is a multi-ethnic nation with culturally unique and diverse practices. It has much to offer in terms of developing its own indigenous psychology grounded in local research and practice. Postgraduate training would benefit from a shift away from heavily theory-based instruction to practical, applied skills training focused on evidence-based interventions that are culturally, contextually and linguistically relevant. The profession would benefit from more active engagement in government policy development that integrates these mental health interventions, counselling services and research into government strategy and development planning. Establishing professional regulatory bodies that hold practitioners accountable to professional standards and ethical practice would aid in legitimizing the profession. The Ethiopian Psychologist Association (EPA) is well-positioned to lead this process. Support from other African countries that have built this professional infrastructure, such as South Africa, may be of value. Universities offering postgraduate training in counselling psychology (and other categories) would benefit from stronger academic collaborations within the country and on the continent in order to further develop Ethiopian scholarship in the field. This networking initiative could be facilitated through bodies such as the Pan-African Psychology Union, and professional bodies within other African countries like the Psychological Society of South Africa.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received financial support from the South African National Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences (NIHSS) in the form of a Mobility Grant (BMG21/1008) to foster collaboration and networking between Counselling Psychology Programmes at Hawassa University in Ethiopia and Rhodes University South Africa.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Adane W. Jarsso; data collection: Adane W. Jarsso; analysis and interpretation of results: Adane W. Jarsso, Elron S. Fouten, Megan M. Campbell; draft manuscript preparation: Adane W. Jarsso, Megan M. Campbell. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available through the references provided within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Abdi, Y. (1998). Gender Sensitive Counselling. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Printing Press. [Google Scholar]

Abeshu, G., & Baissa, T. (2019). Indigenous counseling system of oromo community in Ethiopia. J Psychol Psychother, 9(355), 2161–0487. https://doi.org/10.35248/2161-0487.19.9.355 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Abeshu, G., & Urgessa, D. (2022). Counselling and reconciliation practices among the Oromo community. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 22(3), 583–593. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12478 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Awol Amado, A., & Shiferew, B. (2022). Perceived need to counseling service and associated factors among higher education institutions: The case of Dilla University, Southern Ethiopia. Education Research International, 2022(1), 7307306. [Google Scholar]

Bekele, Y., Flisher, A., Alem, A., & Baheretebeb, Y. (2009). Pathways to psychiatric care in Ethiopia. Psychological Medicine, 39(3), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708003929 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Disassa, G. (2020). Counselling and Counselling services status in Ethiopia. The International Journal of Counselling and Education, 5(3), 101–106. https://doi.org/10.23916/0020200528430 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disassa, G. A., & Gita, D. U. (2023). Counselling and Counselling services status in Ethiopia. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 33(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2021.1994903 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health (2012). The national mental health strategies (2012/13–2015/16). Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia [FDRE], & Ethiopian Ministry of Health (MOH) (2007). Guidelines for HIV counselling and testing in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia [FDRE], & Ministry of Education [MoE] (2018). Ethiopian education development roadmap (2018–30An integrated executive summary (Vol. 4, pp. 9–12). Addis Ababa: Ministry of Education Education Strategy Center (ESC). [Google Scholar]

Getachew, A. (2019). Assessment of Psychological Counseling service for higher education institution students. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 7(4), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.7n.4p.53 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hughes, T., Quinn, C., Tiberi, A., & Zeleke, W. (2020). Developing a framework to increase access to mental health services for children with special needs in Ethiopia. Frontiers in Sociology, 5, 583931. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.583931 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Janetius, S. T., Tibebe, A. I., & Mini, C. T. (2013). Abyssina in the New Millennium: (Revised Edition). Ethiopia: Amazon CS Publication. [Google Scholar]

Jani, N., Vu, L., Kay, L., Habtamu, K., & Kalibala, S. (2016). Reducing HIV-related risk and mental health problems through a client-centred psychosocial intervention for vulnerable adolescents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Journal of The International AIDS Society, 19, 20832. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.19.5.20832 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kassa, G. M., & Abajobir, A. A. (2018). Prevalence of common mental illnesses in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research, 30, 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npbr.2018.06.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kebede, W., & Wubshet, N. (2018). Challenges and initiatives to strengthen counselling psychology program and services at Addis Ababa University and different places. Ethiopian Journal of Behavioral Studies, 2(1), 174–180. [Google Scholar]

Kelkay, A. D. (2019). Practice and challenges in the provision of guidance and counselling services in secondary schools of South Gondar, Ethiopia. Global Journal of Guidance and Counselling in Schools: Current Perspectives, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.18844/gjgc.v9i1.3859 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Keynejad, R. C., Bitew, T., Sorsdahl, K., Myers, B., Honikman, S. et al. (2024). Adapting brief problem-solving therapy for pregnant women experiencing depressive symptoms and intimate partner violence in rural Ethiopia. Psychotherapy Research, 34(4), 5381–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2023.2222899 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kirmayer, L. J., & Swartz, L. (2013). Culture and global mental health. In V. Patel, H. Minas, A. Cohen & M. Prince (Eds) Global mental health: Principles and practice (pp. 41–62). UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Legas, A. M., & Mengistu, A. A. (2018). The practice of guidance and counselling service in Amhara regional state public universities, Ethiopia. Perspectives, 8(3), 119–127. [Google Scholar]

Likisa, K. D., & Tura, J. A. (2020). The status of guidance and counselling service in ethiopian science and technology universities. Ethiopian Journal of Science and Sustainable Development, 7(2), 50–63. [Google Scholar]

Lund, C., Tomlinson, M., De Silva, M., Fekadu, A., Shidhaye, R. et al. (2012). PRIME: A programme to reduce the treatment gap for mental disorders in five low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med, 9(12), e1001359. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001359 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Swancott, R., Uppal, G., & Crossley, J. (2014). Globalization of psychology: Implications for the development of psychology in Ethiopia. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(5), 579–584 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Tesera, B., & Temesgen, A. (2023). Guidance and counselling services in secondary schools in eastern gojjam administrative zone: A mixed design evaluation of priority needs, service barriers and facilitators. The Ethiopian Journal of Behavioural Studies, 6(1), 122–145. [Google Scholar]

Teferra, T., Asgedom, A., Oumer, J., Dalelo, A., & Assefa, B. (2018). Ethiopian education development roadmap (2018–30). An integrated executive summary. Ministry of education strategy center (ESC) draft for discussion: Addis Ababa, 4, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) (2022). Data for the sustainable development goals: UIS stat bulk data download service. Retrieved from: http://uis.unesco.org. [Google Scholar]

Wako, A. (2016). The status of utilization of school guidance and counselling services in ethiopian secondary schools in addressing the psychosocial and academic needs of secondary school students: The case of Sidama zone, SNNPRS. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 21(2), 27–35. [Google Scholar]

Woldie, G. (2021). Practice and challenges of counselling training in Ethiopian Universities [doctoral thesis]. South Africa: University of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

Wondie, Y. (2014). Reflections on the development of psychology in Ethiopia and future directions. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(5), 585–588 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

World Health Organization (2010). Mental health and development: Targeting people with mental health conditions as a vulnerable group. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

Zeleke, S. (2000). Major problems of counselling in Ethiopian high schools. IER Flambeau, 7(2), 17–26. [Google Scholar]

Zeleke, W., Nichols, L., & Wondie, Y. (2019). Mental health in Ethiopia: Exploratory study of counselling alignment with culture. International Journal of Advanced Counselling, 41, 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-018-9368-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools