Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Perceived social support and sense of meaning in life of Chinese rural college students: A coping style and psychological resilience moderated mediation model

1 Faculty of Education, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, 130024, China

2 School of Physical Education, Chinese Center of Exercise Epidemiology, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, 130024, China

3 School of Physical Education, Changchun Normal University, Changchun, 130032, China

* Corresponding Authors: Chaowei Zhang. Email: ; Jingyu Zhang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 179-186. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065798

Received 13 October 2024; Accepted 01 March 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This study explored how perceived social support (PSS) influences the sense of meaning in life (SML) among rural college students, considering positive coping styles (PCS) as a mediator and psychological resilience (PR) as a moderator. 1444 college students (females; 23.55% only child; Mage = 19.76 years, SD = 1.07; 76.66%) were recruited from Jilin province in China. The college students self-reported their perceived social support and positive coping styles, psychological resilience, and sense of meaning in life. The results indicated that higher perceived social support predicted higher college students’ sense of meaning in life. Perceived social support positively contributes to college students’ sense of meaning in life through the mediating role of positive coping styles. Psychological resilience moderates the first path of the indirect association, where the positive effect of perceived social support on positive coping styles is more pronounced in college students with higher psychological resilience compared to those with lower psychological resilience. These align with Social Support Theory and Psychological Resilience Theory. That is, individuals with effective social support systems can enhance their positive coping styles, thereby increasing their sense of meaning in life, while psychological resilience strengthens the positive impact of perceived social support on positive coping styles. These findings offer the evidence for intervening and supporting the development of college students’ sense of meaning in life. To enhance rural college students’ sense of meaning in life, it is essential to establish a comprehensive social support system, promote the development of positive coping styles, and provide targeted training to strengthen psychological resilience.Keywords

College students as emerging adults are working on the their sense of meaning in life to be who they are. They have begun to resist the gradual “involutionalization” of the social development model (Li & Yang, 2024). Most rural college students in China come from resource-deprived rural areas, with relatively poor family economic conditions and traditional educational values (Ma, 2015). Due to their long-term life in rural areas, many rural students face significant cultural adaptation challenges when they enter university (Xiao & Wu, 2019). Among them, rural students’ mental health levels are generally lower than those of urban students (Guo et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2017). It has been found that rural college students are generally weaker in interpersonal skills, and after entering urban universities, they are subjected to greater impacts in terms of both their living habits and ways of thinking, and their life adaptation pressures and relationship distress are significantly higher than those of urban students (Zhang, et al., 2020). In addition, those from rural areas are more prone to psychological maladjustment being away from their families of origin (Hu et al., 2023), risking lower sense of meaning in life. According to Steger et al. (2009), meaning in life encompasses an individual’s perception that their existence holds purpose, direction, and intrinsic value. It is a key indicator of psychological well-being (Wang et al., 2022; Hooker et al., 2018). To flourish their sense of meaning, people need social support from others going beyond trivial and transient events, set meaningful life goals, use their life energy to realize a desired future, and experience life as worth living. Xiao (1994) conceptualized social support as a multifaceted construct, including perceived emotional backing, tangible assistance, and the individual’s engagement with available resources. With college students, their meaning in life futures would depend on sense of coping and psychological resilience in way less well explored among those from rural areas. Coping style refers to the mental and behavioral strategies individuals adopt to relieve psychological stress when encountering difficult or stressful situations, and it is generally divided into positive and negative types (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Xie, 1998). Psychological resilience is defined as the personal qualities and psychological strengths that help individuals withstand adversity (Connor & Davidson, 2003), (Connor & Davidson, 2003) or the psychological capitals of an individual (Luthan et al., 2007). The present study aimed to explore the potential mechanisms underlying the association between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life among Chinese rural college students.

Perceived social support and sense of meaning in life

Social support typically encompasses various forms of assistance from family, friends, and other social networks (Zimet et al., 1988). According to social support theory, individuals who have access to reliable support systems tend to experience more positive emotions and receive consistent feedback (Cohen & Wills, 1985). Relationships and social support are important to all people, regardless of culture. Those who live in collectivist societies, such as China, may prioritize social interactions more (Wong & Tjosvold, 2006). Good social relationships and social support are important sources of sense of meaning in life (Liu et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2016; King & Hicks, 2021). Meaningful relationships with family, friends, and close companions, alongside feelings of belonging and closeness, contribute significantly to a richer sense of meaning in life (Krause, 2007; Elizabeth & Chang, 2021; Stavrova & Luhmann, 2015). The study found that over time, adults who reported more support and less stress in their social relationships were more likely to increase their sense of purpose (Weston et al., 2021). On the contrary, social exclusion and ostracism can lead to a feeling that life is meaningless (Krause, 2007; Lambert et al., 2013).

Recent studies have also found that perceived social support significantly predicts Chinese college students’ sense of meaning in life. In China, college students from rural areas are still at a relative disadvantage compared to those from urban areas (Rui, 2020). However, few studies have focused on the special group of Chinese rural college students. Compared with college students from urban areas, perceived social support plays a more important role in this special group of rural Chinese college students and may influence the formation and development of their sense of meaning in life. Therefore, we recruited a sample of Chinese rural college students to examine this relationship, which enriches the research on Chinese rural college students’ sense of meaning in life.

Positive coping styles as a mediator

A positive coping style involves using cognitive or behavioral efforts aimed at achieving constructive results when dealing with stressful experiences (Wu et al., 2020). Social support can affect an individual’s coping style (Dong et al., 2019). Individuals who experience emotional support and understanding in their relationships are more prone to adopt positive coping styless (Shen et al., 2018). When the level of perceived social support is lower, individuals are more likely to adopt relatively negative coping styles, such as avoidance (Meng & Ma, 2019). Other researchers have studied college students with traumatic childhood experiences and have found that the higher the level of perceived social support, the more likely such college students are to adopt positive coping styles with negative life events (Zhou et al., 2024). At the same time, positive coping styles are related to the individual’s sense of meaning in life. Individuals who utilize positive coping styles are more likely to experience a stronger sense of meaning in life, whereas those who rely on negative coping styles often report a diminished perception of life’s meaning (Li et al., 2014).

Psychological resilience as a moderator

According to resilience theory and the risk-buffering framework, psychological resilience acts as an internal safeguard that mitigates the detrimental effects of various risk factors, thereby fostering healthier developmental outcomes by cushioning individuals from potential harm (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005; Hollister-Wagner et al., 2001). This means that individuals who are more psychological resilience, as opposed to those who are less psychological resilience, are typically more adaptive and flexible, which allows them to better integrate and utilize social support in order to adapt to different challenging and stressful situations using more positive coping styles, resulting in a higher level of sense of meaning in life (Cai, 2010). Thus, with the help of high levels of psychological resilience, perceived social support can be more effective in promoting positive coping styles.

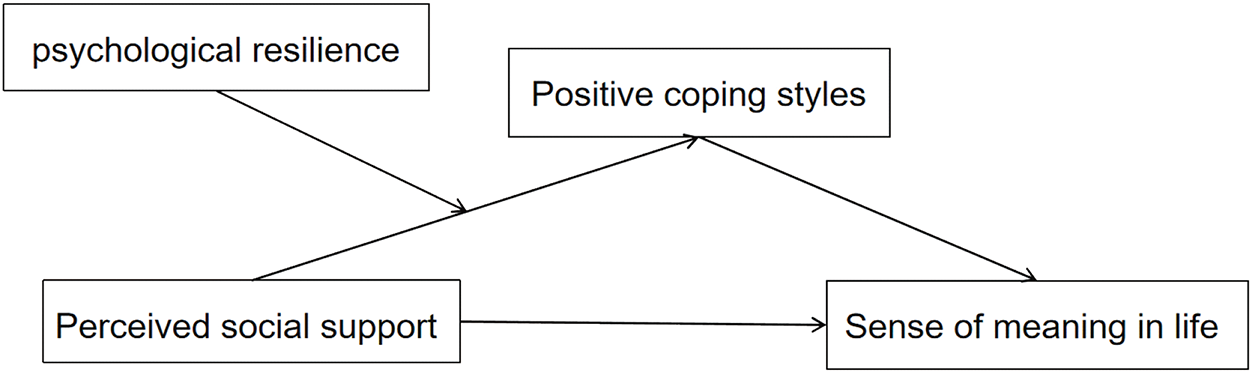

Building on the above review, this study aimed to examine the relationship between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life among rural college students, with positive coping styles serving as a mediator and psychological resilience acting as a moderator. We proposed a moderated mediation model (Figure 1) to examine whether (a) perceived social support is related to rural college students’ sense of meaning in life, (b) positive coping styles mediates the relation between perceived social support and rural college students’ sense of meaning in life, and (c) psychological resilience play a moderating role in the influence mechanism?

Figure 1: The proposed model

Aligned to these research questions, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H1: Higher perceived social support of college students predict higher sense of meaning in life.

H2: Positive coping styles plays a mediating role in the relationship between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life for higher sense of meaning in life.

H3: Psychological resilience moderates the first path of the indirect association, where the positive effect of perceived social support on positive coping styles is more pronounced in college students with higher psychological resilience compared to those with lower psychological resilience.

A total of 1444 rural college students from a normal university in Jilin Province, China, participated in the study. By sociodemographics, 76.66% are females, 23.55% are only child. Furthermore, 44.5%, 54.29%, 0.42%, and 0.76% were freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors, respectively. Participants’ average age was 19.76 years (SD = 1.07). The age distribution ranged from 16 to 29 years.

The perceived social support scale

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) (Zimet et al., 1988; Jiang, 2001) consists of 12 items on assessing support from friends, others and family. Sample items are “I can rely on my friends when things go wrong” and “I can receive emotional help and support from my family when needed”. The items are on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Higher scores indicate greater perception of social support. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for PSSS scores a previous study was 0.88, indicating good reliability (Zimet et al., 1988). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for family support, friend support, and other support were 0.952, 0.962, and 0.948, respectively. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for the total scale was 0.970.

Simplified coping style questionnaire (SCSQ)

The Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ; Xie, 1998) is a 20-item instrument assessing individuals’ typical strategies in response to stress. Items 1 through 12 evaluate positive coping approaches (e.g., “seek advice from relatives, friends, or classmates”), while items 13 to 20 measure negative responses such as substance use or emotional eating. Responses are given on a 4-point frequency scale from 1 (“not adopted”) to 4 (“frequently adopted”). Only the positive coping subscale was utilized in the present study. This subscale demonstrated excellent internal reliability, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.967.

Psychological resilience scale

The Psychological Resilience Scale (Connor & Davidson, 2003; Xu et al., 2016) includes 17 items that assess individual resilience across four domains: tenacity, self-regulation, goal orientation, and social adaptability. An example item is “I will not be discouraged by failures”. Respondents rated each item on a 5-point scale (1 = very inconsistent to 5 = very consistent). Average scores were computed, with elevated scores indicating higher levels of psychological resilience. In this study, internal consistency coefficients for the four dimensions were 0.946 (tenacity), 0.898 (self-regulation), 0.961 (goal orientation), and 0.896 (social adaptability), with the full scale achieving an α of 0.975.

The sense of meaning of life questionnaire

The Chinese version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ-C; originally developed by Steger et al., 2006 and localized by Liu & Gan, 2010) includes two distinct subdimensions.: presence of meaning and search for meaning, each with five items. Example statements include “I have already found a life purpose that satisfies me” (presence) and “I am searching for the meaning of my life” (search). Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely untrue) to 7 (completely true), with the second item reverse-scored. Greater total scores reflect a stronger perceived sense of life meaning. The overall scale exhibited high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.928), with the two subscales yielding α values of 0.839 and 0.937, respectively.

The study received approval from the corresponding author’s University Ethics Committee. Students’ consent was obtained for the survey, with assurances of voluntary, anonymous, and confidential participation. Data were collected online.

IBM SPSS (version 22.0) was used for common method bias testing, descriptive statistics, and correlation analysis, while AMOS 24.0 was used for structural equation modeling and bootstrap analysis. The bootstrap method involved 5000 resamples to estimate 95% confidence intervals.

Common Method Bias Test. In this study, a one-factor confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess common method bias for all items. The results indicated poor model fit, with χ2/df = 26.173, GFI = 0.335, NFI = 0.658, RFI = 0.644, TLI = 0.653, and RMSEA = 0.132. Thus, no significant common method bias was identified. (Zhou & Long, 2004).

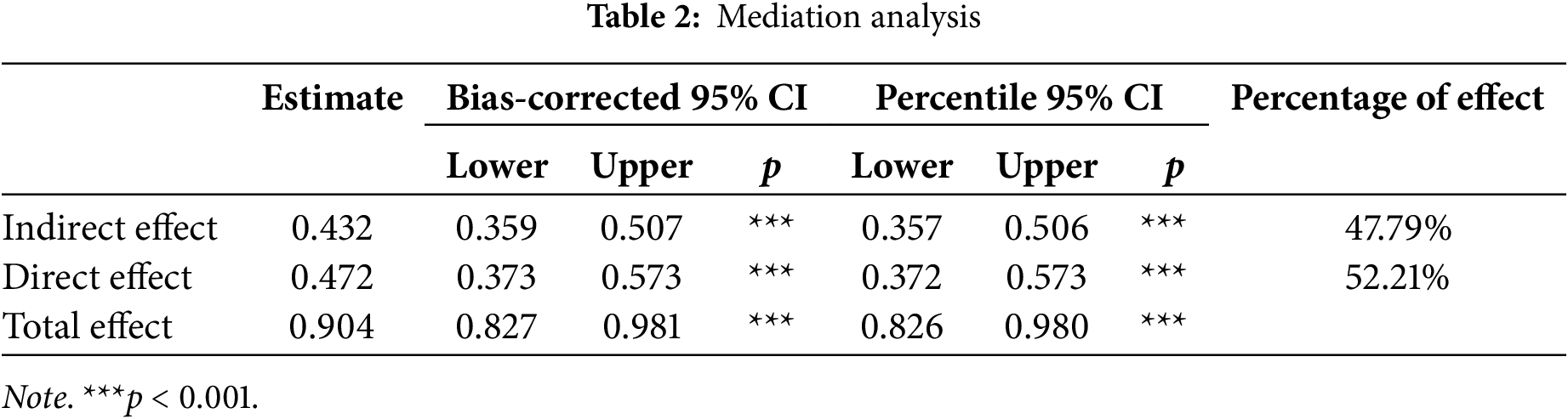

A mediation model with the positive coping styles as a mediator was tested using AMOS 24.0. The data were standardized prior to analysis, and bootstrap resampling (5000 iterations) was used to estimate 95% confidence intervals.

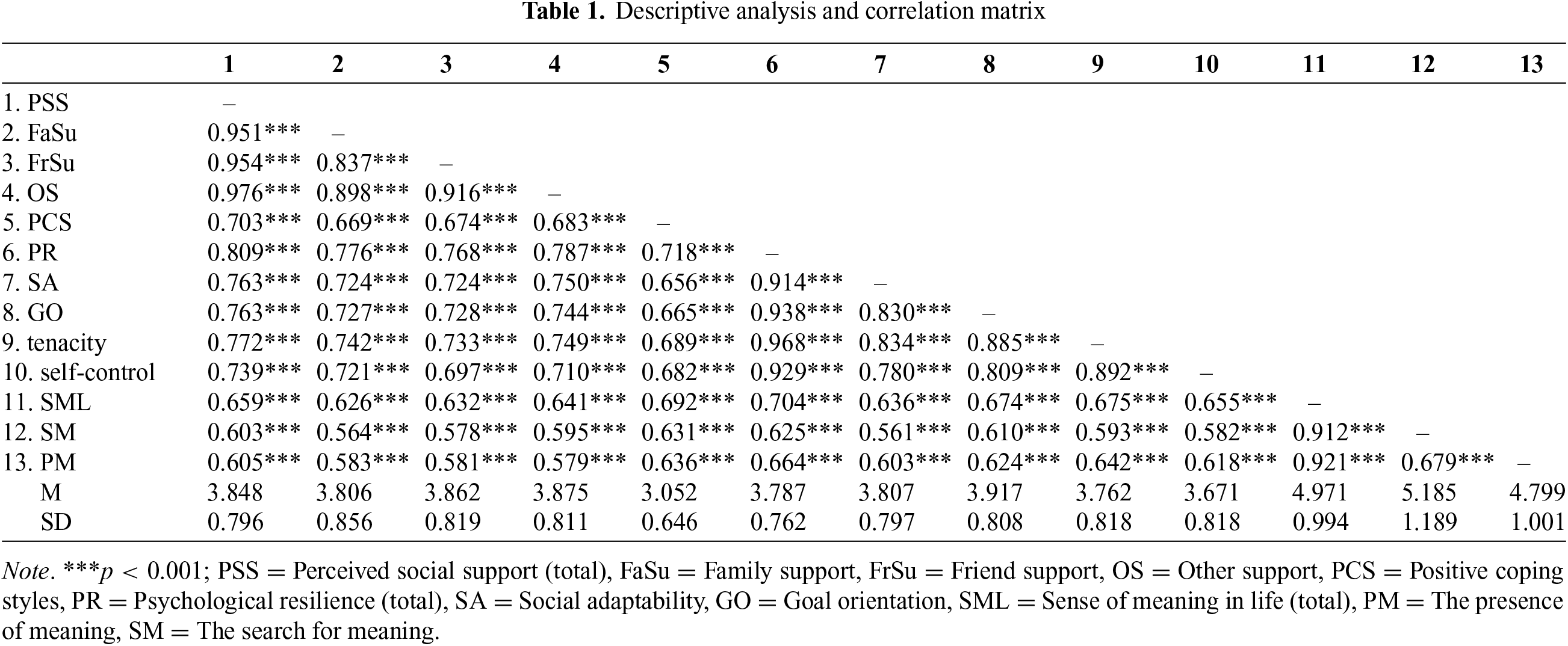

Descriptive statistics and correlation

Pearson correlation was applied to assess the variables in this study, and the results are presented in Table 1. The analysis revealed significant positive correlations between college students’ perceived social support, positive coping styles, psychological resilience, and sense of meaning in life, with all dimensions showing significant positive bidirectional correlations.

Testing the mediation model revealed a good fit: χ2/df = 8.959, RMSEA = 0.074, CFI = 0.993, GFI = 0.987, AGFI = 0.960, NFI = 0.992, and IFI = 0.993.

Table 2 shows that perceived social support directly influences the sense of meaning in life, with a coefficient of 0.472 (95% CI [0.372, 0.673], p < 0.001), indicating that parents’ perceived social support positively predicts sense of meaning in life. Hence, Hypothesis 1 was supported. The indirect effect of the perceived social support, positive coping styles, and sense of meaning in life was 0.432 (95% CI [0.357, 0.506], p < 0.001), with all confidence intervals not containing 0. Both direct and indirect effects were significant, indicating that the positive coping styles partially mediates the relationship between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life. Hence, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Test of the moderated mediation model

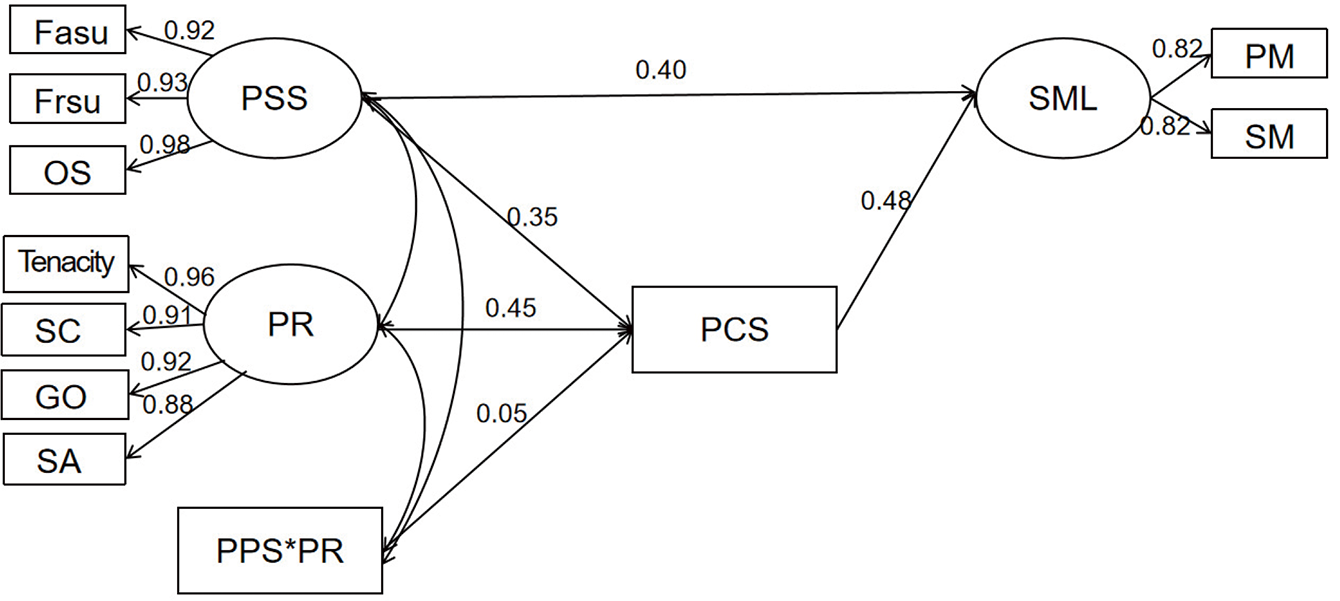

In line with the proposed hypotheses, a latent variable structural equation model was developed, as illustrated in Figure 2. The model was evaluated using the bootstrap method with 5000 resamples and 95% confidence intervals, following the procedure outlined by Wen and Ye (2014). The results indicated a good model fit (χ2/df = 12.700, RMSEA = 0.090, CFI = 0.973, GFI = 0.941, NFI = 0.971, IFI = 0.973, TLI = 0.961). Psychological resilience was found to positively and significantly predict positive coping styles (β = 0.445, 95% CI [0.351, 0.536]). Additionally, the interaction between perceived social support and psychological resilience had a significant positive effect on positive coping styles (β = 0.054, 95% CI [0.023, 0.088]). Since the confidence interval did not include zero, this interaction was statistically significant, indicating that psychological resilience moderated the initial stage of the indirect relationship. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Figure 2: A moderated mediation model. PSS = Perceived social support, FaSu = Family support, FrSu = Friend support, OS = Other support, PCS = Positive coping styles, PR = Psychological resilience, SA = Social adaptability, GO = Goal orientation, SML = Sense of meaning in life, PM = The presence of meaning, SM = The search for meaning

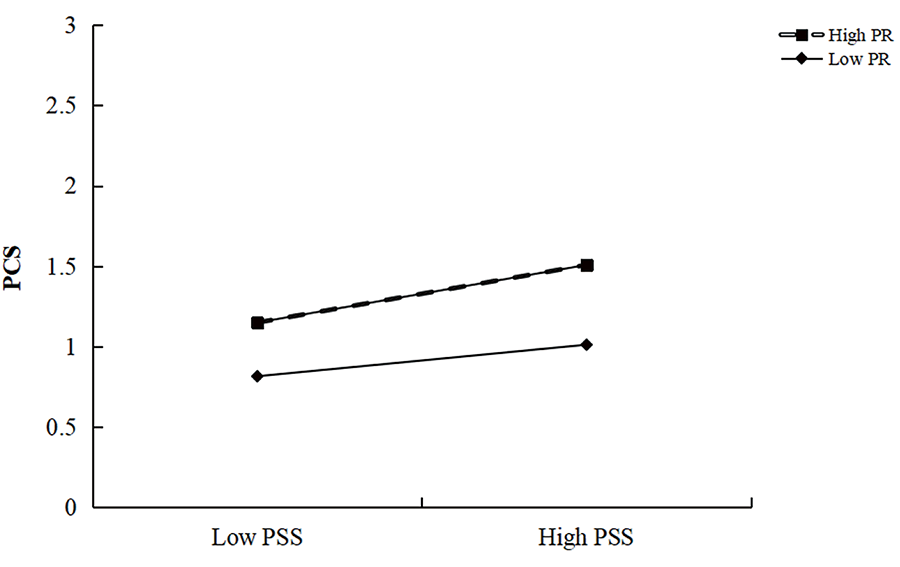

To further investigate the mechanism underlying the first stage of the mediation involving psychological resilience, the sample was divided into high (M + 1SD) and low (M − 1SD) resilience subgroups. A simple slope analysis was then conducted, and the results are illustrated in Figure 3. Among students with high psychological resilience, perceived social support showed a significant positive association with positive coping styles (β = 4.549, 95% CI [0.2706, 0.3762]). Although this relationship remained significant in the low-resilience group, its strength was notably reduced (β = 3.026, 95% CI [0.2113, 0.3118]).

Figure 3: The moderating role of PR. PSS = Perceived social support, PCS = Positive coping styles, PR = Psychological resilience

Our results indicated that higher perceived social support was associated with higher sense of meaning in life among rural college students. This finding can be explained by Social Support Theory in three aspects: first, when feeling more social support, the individual can construct his own positive belief system, he will have stronger motivation to pursue his existing goals, and enhance the sense of meaning in life (Snyder, 2002). Rural college students experience more difficulty adjusting to college life than their urban counterparts, and positive support from family, friends, teachers and the community can enhance their confidence and quality of life. Social support also helps them to better face the challenges of life, and thus strengthen their sense of meaning in life (Liao & Huang, 2020; Jenkins et al., 2013; Trepte, et al., 2015). Second, Rural college students with high social support tend to have access to more resources, such as educational opportunities, economic assistance, and information resources important for their college life with sense of meaning (Awang et al., 2021). Third, When rural college students feel supported and recognized by society, they will feel that they are a useful part of society, and this sense of recognition can also enhance their sense of meaning in life (Lian, 2015).

Our results indicated positive coping styles mediated the relationship between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life of rural college students. In theory, college students perceived social support could have a positive effect on positive coping styles, which in turn helps stimulate their sense of meaning in life. Social support provides individuals with the necessary resources, such as information, material help, emotional comfort, etc., which helps individuals adopt more positive attitudes and actions in the face of stress and challenges (Shen et al., 2018). At the same time, positive coping styles are generally more effective in helping individuals to better solve problems and overcome difficulties, and the sense of accomplishment that comes from successfully coping with challenges can increase individuals’ perceptions of control and understanding of their lives, and individuals who use positive coping styles tend to show higher levels of sense of meaning in life (Li et al., 2014).

This study found psychological resilience to moderate the mediating effect of positive coping styles in the relationship between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life for higher sense of meaning in life. According to the theory of psychological resilience (Gooding et al., 2012), individuals possess an inherent capacity to adjust and transform when confronted with stressful or adverse circumstances. This self-regulatory process emerges as individuals actively engage their internal strengths to cope constructively with external demands and challenges. Rural college students often face more severe existential problems, and the internal strengths of rural college students with high psychological resilience will help them to better utilize the power of social support to positively cope with life’s challenges than those of rural college students with low psychological resilience (Amstadter et al., 2014; Gooding et al., 2012).

Implications for theory and practice

Although there is some evidence that perceived social support has an effect on sense of meaning in life, the underlying mechanisms of this correlation remain unknown. In addition, there are fewer studies on the relationship between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life targeting Chinese rural college students. The progression of online buzzwords from “Buddhist” to “lying flat” and more recently “swinging rotten” reflects more than just playful or carefree language trends—it also reveals a growing existential anxiety among some college students, resulting in a weakened sense of direction and diminished clarity about life’s meaning (Ling & Wang, 2023; Peng & Yu, 2023; Wu & Kong, 2019). This study findings provides some insights into the meaning of life education and mental health promotion of Chinese rural college students and even college students from less developed regions of the world, but will also provide inspiration for policy makers to narrow the urban-rural education gap and promote educational equity.

First, colleges and universities should pay attention to the social support system of rural college students to enhance their social ties and sense of belonging by establishing good teacher-student relationships and peer support groups, et cetera. Families should also endeavor to provide rural college students with emotional care, information help and resource support. Second, educators can help rural college students learn and adopt positive coping styles to face challenges and pressures in life through mental health education programs, guide students to identify and utilize their strengths, and develop problem-solving abilities and optimistic attitudes toward life. Third, schools can help students improve their psychological resilience through activities such as mental toughness training and stress management seminars.

Strengths, limitations, and future recommendations

This study makes two primary contributions to the existing body of literature. First, it adds valuable insights to the relatively limited research on rural college students, enhancing understanding of this underrepresented population. Second, it offers more robust empirical evidence on the association between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life, while further examining the underlying mechanisms involved in this relationship.

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. To begin with, the use of a cross-sectional, self-reported survey design restricts the ability to infer causality. Future research would benefit from employing longitudinal approaches to gain a deeper and more dynamic understanding of the relationships examined. Secondly, we only investigate the role of perceived social support, positive coping styles, and psychological resilience among rural college students and findings may be different for urban background college students. Moreover, the influence of other factors (e.g., personality traits, parent-child relationships, academic achievement and so forth) should be considered by future studies. Finally, this research relied exclusively on quantitative methods. Incorporating qualitative techniques, such as in-depth interviews with rural Chinese college students, could offer richer perspectives and help validate the current findings.

In conclusion, we found that perceived social support is positively related to Chinese rural college students’ sense of meaning in life, and positive coping styles partially mediated this relationship. Moreover, psychological resilience moderates the mediating effect of positive coping styles in the relationship between perceived social support and sense of meaning in life, which means that this mediating effect is stronger when Chinese rural college students have strong psychological resilience. This study deepened the understanding towards Chinese rural college students by investigating how to improve their sense of meaning in life.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wenqi Lin, Chaowei Zhang; data collection: Jingyu Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Wenqi Lin, Chaowei Zhang, Jingyu Zhang; draft manuscript preparation: Wenqi Lin, Chaowei Zhang, Jingyu Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All procedures involving human participants were conducted in compliance with the ethical standards set by the institutional or national research committee (Ethical Approval No. 20240611.03). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Amstadter, A. B., Myers, J. M., & Kenneth, S. K. (2014). Psychiatric resilience: Longitudinal twin study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 205(4), 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.130906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Awang, M. M., Ahmad, A. R., & Allang, B. A. (2021). Rural education: How successful low-income students received socio-educational supports from families, school teachers and peers? International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 10(1), 311–320. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v10-i1/8988 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cai, Y. (2010). The relationship between resilience, stress distress and adjustment [Master thesis]. Tianjin, China: Tianjin Normal University. [Google Scholar]

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1520-6394 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong, R., Hua, L., & Yu, L. (2019). Path analysis on the influence of clinicians’ social support, resilience andcoping style on their occupational stress. Journal of Capital Medical University, 40(5), 677–682. [Google Scholar]

Elizabeth, A. Y., & Chang, E. C. (2021). Relational meaning in life as a predictor of interpersonal well-being: A prospective analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110377 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26(1), 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gooding, P. A., Hurst, A., Johnson, J., & Tarrier, N. (2012). Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(3), 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Guo, Y., Zhang, N., & Zhang, J. (2013). Comparation of positive psychological quality and its influencing factors among nursing students from rural and Urban Areas. Chinese Journal of Public Health, 29(7), 1041–1045. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Hollister-Wagner, G. H., Foshee, V. A., & Jackson, C. (2001). Adolescent aggression: Models of resiliency. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 445–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02050.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hooker, S. A., Masters, K. S., & Park, C. L. (2018). A meaningful life is a healthy life: A conceptual model linking meaning and meaning salience to health. Review of General Psychology, 22(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000115 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hu, F., Tang, C., & Zhang, K. (2023). Analysis of psychological crisis vulnerability among rural college students and its related factors. Chinese Journal of School, 44(7), 1021–1025. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Jenkins, S. R., Belanger, A., Connally, M. L., Boals, A., & Durón, K. M. (2013). First-generation undergraduate students’ social support, depression, and life satisfaction. Journal of College Counseling, 16(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2013.00032.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jiang, Q. (2001). Perceived social support scale. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medicine and Brain Science, 10(10), 41–43. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-072420-122921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Krause, N. (2007). Longitudinal study of social support and meaning in life. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 456. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lambert, N. M., Stillman, T. F., Hicks, J. A., Kamble, S., Baumeister, R. F. et al. (2013). To belong is to matter: Sense of belonging enhances meaning in life. Personality and Social PsychologyBulletin, 39(11), 1418–1427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Li, Y., He, W., Zhang, X., Guo, F., Cai, J. et al. (2014). The relationship between parenting style, coping style, index of well-being and life of meaning of undergraduates. China Journal of Health Psychology, 22, 1683–1685. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Li, Z., & Yang, X. (2024). From “Involution” to “Anti-involution”: Formation and guidance of college students’ values. Education Research Monthly, (6):71–78. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Lian, L. (2015). Relationship among perceived social support, big five personality and subjective well-being in rural college students. China Journal of Health Psychology, 23(5746–749. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Liao, Q., & Huang, Y. (2020). Class ldentity: A new perspective to understand the learning experiencesof rural college students. Tsinghua Journal of Education, 41(6), 75–82. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Ling, X., & Wang, Y. (2023). Inner volume, Buddha System and lying flat: Conceptual evolution, boundary layer order and correction strategies: Interpretation based on the perspective of cultural philosophy. Journal of Xinjiang Normal University (Edition of Philosophy and Social Sciences), 44(5), 130–148. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Liu, S., & Gan, Y. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 24(6), 478–482. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Liu, Y., Zhang, X., Zhu, C., Su, R., Yin, Y. (2020). Research on meaning of life from the perspective of positive psychology. Chinese Journal of Special Education, (11), 70–75. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Luthan, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 54–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ma, D. (2015). Losing mobility at the beginning: Urban pathways for rural students. China Youth Study, 10, 56–60, 65. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Meng, W., & Ma, X. (2019). Correlation study between medical coping mode and perceived socia support of elderly patients with diabetes in communities in Changchun City. Medicine and Society, 32(7), 107–109. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Peng, J., & Yu, T. (2023). A multidimensional analysis of the “lying flat” phenomenon of contemporary college students: Based on a survey and analysis of 23 college students in China. Journal of Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics (Social Sciences Edition), 36(2), 174–181. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Rui, F. (2020). Rural college students’ self-adaptation to urban society: Internal and external dilemma and philosophical cognition. Journal of Xichang University (Social Science Edition), 32(1), 75–77, 124. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Shen, Y., Hu, X., & Ye, B. (2018). The effect of stress on college students’ depression: The mediating effectof perceived social support and coping style. Psychological Exploration, 38(3), 267–272. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13(4249–275. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stavrova, O., & Luhmann, M. (2015). Social connectedness as a source and consequence of meaning in life. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 470–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1117127 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Steger, M., Oishi, S., & Kashdan, T. (2009). Meaning in life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802303127 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Trepte, S., Dienlin, T., & Reinecke, L. (2015). Influence of social support received in online and offline contexts on satisfaction with social support and satisfaction with life: A longitudinal study. Media Psychology, 18(1), 74–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.838904 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, K. Y., Kealy, D., & Cox, D. W. (2022). A pathway to meaning in life: Early parental support, attachment, and the moderating role of Alexithymia. Journal of Adult Development, 29(4), 306–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-022-09418-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wen, Z., & Ye, B. (2014). Different methods for testing moderated mediation models: Competitors or backups? Acta Psychologica Sinica, 46(5), 714–726. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.00714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Weston, S. J., Lewis, N. A., & Hill, P. L. (2021). Building sense of purpose in older adulthood: Examining the role of supportive relationships. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(3), 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1725607 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wong, A., & Tjosvold, D. (2006). Collectivist values for learning in organizational relationships in China: The role of trust and vertical coordination. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(3), 299–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-006-9000-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, N., & Kong, J. (2019). Survival anxiety and resolution of youth in the context of Social acceleration: Based on Rosa’s Social acceleration theory. Journal of Shandong Youth University of Political Science, 40(1), 39–45. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Wu, Y., Yu, W., Wu, X., Wan, H., Wang, Y. et al. (2020). Psychological resilience and positive coping styles among Chinese undergraduate students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00444-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xiao, S. (1994). Theoretical foundations and research applications of the Social Support Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 4(2), 98–100. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Xiao, T., & Wu, Z. (2019). The acculturation strategies of rural undergraduates and their social network characteristics. Journal of Higher Education, 40(9), 78–85. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Xie, Y. (1998). A preliminary study of the reliability and validity of the Brief Coping Style Scale. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 2, 53–54. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Xu, Y., Zhou, R., & Fu, C. (2016). Reliability and validity of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RlSC) in Chinese college students. China Journal of Health Psychology, 24(6), 894–897. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Zhang, J., Li, J., Ma, T. et al. (2020). Analysis on the status and influencing factors of social anxiety of college students in a university in Changchun City. Medicine and Society, 33(3), 112–115. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Zhang, J., Qi, Q., & Delprino, R. P. (2017). Psychological health among Chinese college students: A rural/urban comparison. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 29(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2017.1345745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, H., Sang, Z., Chan, D. K. S., Teng, F., Liu, M. et al. (2016). Sources of meaning in life among Chinese university students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1473–1492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9653-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhou, H., & Long, L. (2004). Statistical remedies for common method biases. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942–950. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Zhou, C., Zhou, Y., & Li, H. (2024). Perceived social support and post-traumatic growth in college students experienced childhood trauma: A moderated mediating model. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 32(4), 755–760, 798. [Google Scholar]

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools