Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

“Why Do I Write?”: A psychobiographical study of Bessie Amelia Emery Head

Department of Psychology, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2092, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Adeline T. Kingsley. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 187-197. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065998

Received 13 October 2024; Accepted 25 March 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This psychobiographical study on Bessie Head, a bi-racial writer from the South African apartheid period, explored early experiences that defined her identity, personality development and prominence in post-colonial African literature. For the case conceptual framing, we integrate Donald W. Winnicott’s object relations theory with intersectional feminism to explore her identity by the complex interactions between her psychological experiences and socio-political contexts. Our mixed-methodological approach that combines du Plessis’ (2017) structured framework and Knight’s (2019) Phenomenological-hermeneutic Life-narrative Analysis. The analysis revealed three central findings. First, Bessie’s identity development was shaped by early abandonment and racial liminality, resulting in a fragmented sense of self. Second, her emotional and psychological instability was compounded by intersecting experiences of racism, sexism, and exile. Third, her writing and relationships functioned as coping mechanisms and transitional phenomena, offering potential spaces of psychological resilience. From this psychobiographical study framed on intersectional research, the evidence suggests that marginalized identities and a commitment to social justice are revealed by exploring the relationships between individual psychology and systemic influences.Keywords

Psychobiographies seek to reconstruct the life narratives of individuals, thereby advancing or challenging theoretical understandings of human development across the lifespan (Fouché & van Niekerk, 2010; Mayer et al., 2021). However, the lives of historically significant female figures remain underrepresented in this field. Bessie Head (1937–1986), an eminent writer in post-colonial Africa, exemplifies this gap. Her semi-autobiographical narratives explore themes of racism, sexism, and post-colonial identity, establishing her as a literary icon (Agbo, 2021; Al-Ghalith et al., 2023; Cowling & Roberts, 2022; Jeyadharshini & Gnanaprakasam, 2022; Lederer, 2019, 2022). However, a notable gap remains in the literature—a lack of comprehensive analysis examining the psychological development of her identity and personality within the broader socio-political context of her life. We seek to address this gap in psychobiographical literature by analyzing the life and contributions of Bessie Head, a biracial, critically acclaimed writer who lived through the tumultuous period of apartheid in South Africa and later became exiled to Botswana.

Why a Psychobiographical Study?

A defining characteristic of psychobiography is its interpretive and holistic nature, as it seeks to comprehend the subjective meaning of an individual’s life within their unique historical and cultural milieu (Bulut & Usman, 2021; Ponterotto, 2014). The approach is idiographic, focusing on the individual’s unique aspects rather than broad generalizations across populations (Bulut & Usman, 2021; De Luca Picione, 2015; Mayer et al., 2023; Ponterotto, 2014). This method often involves using primary sources such as letters, diaries, and autobiographies, allowing researchers to study the subject’s inner world (du Plessis, 2017). Psychobiography has evolved significantly since its origins, with modern approaches emphasizing the importance of cultural and social contexts in shaping an individual’s life story (Mayer et al., 2022; McAdams, 2018; Schultz & Lawrence, 2017). It has become particularly valuable in understanding the lives of individuals from marginalized groups, offering insights into how socio-cultural dynamics influence psychological development (Mayer, 2023b; Mayer et al., 2023). Psychobiography is an ideal framework to explore Bessie’s identity formation and personality development within the socio-political context of apartheid and post-colonial Africa.

Brief Life History of Bessie Head

Bessie Amelia Emery Head was born into a deeply divided and racially stratified society in South Africa during the apartheid era (1948–1994), a time when the nation was governed by strict segregationist policies that entrenched racial inequality (Eilersen, 2007). The socio-political landscape of apartheid South Africa was marked by the systemic oppression of the Black and Coloured population with laws designed to enforce racial purity and segregation, such as the Group Areas Act (1950), the Immorality Act (1950), and the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 (Arendse, 2021; Seekings, 2021). These laws criminalized relationships between people of different races, a reality that profoundly affected Bessie’s life from birth.

Born on 6 July 1937, in the Fort Napier Mental Institution in Pietermaritzburg, Bessie’s existence directly challenged these oppressive racial policies (Eilersen, 2007; Lederer, 2022). Her birth to a White mother and an unknown Black father marked her as a physical embodiment of racial mingling in a society where such unions were not only frowned upon but criminalized under apartheid’s dehumanizing laws (Eilersen, 2007; Lederer, 2022). Bessie’s mixed-race heritage placed her in a position of extreme marginalization, subjected to the arbitrary and dehumanizing racial classifications that were a hallmark of the apartheid system (Eilersen, 2007).

Growing up in apartheid South Africa

The apartheid era was characterized by a rigid hierarchy that privileged White South Africans while subjugating racialized others. For example, the Population Registration Act of 1950 required all South Africans to be classified into racial groups, which determined every aspect of their lives, including where they could live, work, and attend school (Arendse, 2021; Henrico & Fick, 2019). For Bessie, who was classified as Coloured, this meant living in a liminal space—neither entirely accepted by the White community nor the Black community.

The Coloured community in South Africa occupied a unique and often paradoxical position within the apartheid hierarchy (Ellison & de Wet, 2020; Harrison & Watermeyer, 2019; Yengde, 2021). While they were granted certain privileges over the Black population, such as limited voting rights and access to slightly better schools, they were still subject to systemic discrimination and forced removals under apartheid laws (Eilersen, 2007; Harrison & Watermeyer, 2019; van der Pol et al., 2022). This paradoxical positioning had layered effects, varying by geographical location, social class, and individual circumstances, ultimately shaping their experiences and responses to apartheid’s systemic oppression. Bessie’s childhood was deeply affected by these socio-political dynamics, growing up in an environment where her identity and sense of belonging were constantly challenged by the pervasive racial segregation of the time (Lederer, 2022).

My psychobiographical study adopts the terminology—‘Black’, ‘White’ and ‘Coloured’—consistent with the terms used during apartheid. These categories, while legally and socially significant then, are recognized today as socially constructed, rife with racial essentialism and stereotyping. These terms aim to ensure historical accuracy, not to endorse these racial classifications or their underlying assumptions. The discussion acknowledges ongoing debates and complexities surrounding racial identities.

When Bessie was born, she was initially placed for adoption until her mixed-race heritage was discovered, and she was returned to the adoption organization by the White family who had adopted her (Eilersen, 2007). Bessie was subsequently placed in foster care with a Coloured couple, Nellie and George Heathcote, who lived in the city’s poorest part (Eilersen, 2007). Raised in poverty and marked by the instability of her early years, Bessie’s childhood was one of financial hardship, strict discipline, and a fraught relationship with her foster mother, although she remained largely unaware of her origins and was raised believing she was Nellie’s biological daughter (Eilersen, 2007; Head, 1975).

Her relationship with Nellie was complex: affectionate but marred by severe discipline and instances of being “violently beaten for the slightest thing” (Eilersen, 2007, p. 14; Head, 1975). Bessie stated, “In spite of all this, I adored her, but only through sheer terror of being utterly alone. That was the last defenceless love I had for any human being. The other loves, if they were love, were all defended” (Head, 1975, p. 110). Despite these challenges, Bessie developed a deep love for reading and writing, which became her refuge (Eilersen, 2007; Head, 1975). At the age of twelve, Bessie was sent to St. Monica’s Diocesan Home for Coloured Girls, where she found a more structured environment that allowed her to pursue her educational and literary interests (Eilersen, 2007). Here, she was callously told the truth about her parentage (Eilersen, 2007; Head, 1975). Bessie described the event thus:

There was no ‘coming home.’ The English missionary, in charge of the Durban orphanage, abruptly announced: “You can’t go back there. That’s not your mother.” I went and flung myself under a bush in the school grounds and started to howl my head off. A teacher soon came past and asked what was wrong. “I’m going to die because they won’t let me go home to my mother,” I wailed. She hauled me off to the missionary principal’s office, and that lady, in turn, bundled me into a car and straight to the juvenile section of the Durban Magistrate’s Court. There, a young man read something out in a quick gabble, most of which I didn’t hear except that he insisted that my real mother was a white woman, not the Coloured foster-mother I’d grown up with. This seemed to relieve the missionary. The law had confirmed it. On return to the orphanage, she produced a huge file. Most of what she said was that my mother had been insane and my father was ‘a native.’ That was the big horror, but then there were so many of us at that orphanage who were horrors (Head, 1975, p. 107)

The court’s findings were that Bessie was a child in need of care, and she was placed in the custody of St. Monica’s Home (Eilersen, 2007). Bessie struggled emotionally with this development, as she was cut adrift from the only home she had known and “had to sort out an almost fanatic attachment to the foster-mother” (Head, 1975, p. 107). The revelation deepened Bessie’s sense of abandonment and reinforced her feelings of being an outsider, even within her racial group (Eilersen, 2007; Head, 1975).

As an adult, Bessie continued to experience displacement and struggle. After a brief teaching career, she became a journalist, working first in Durban and later in Cape Town and Johannesburg (Eilersen, 2007). Her work with publications such as the Golden City Post, Drum magazine, The New African and Transition exposed her to the harsh realities of apartheid, intensifying her commitment to writing about social injustices (Abrahams, 1990; Eilersen, 2007). As a woman of mixed race, Bessie faced compounded layers of oppression. Patriarchal structures within both the White-dominated and Black communities further marginalized her, limiting her opportunities and subjecting her to various forms of gender-based discrimination.

Exile in botswana and literary career

In 1964, her involvement with politically charged publications and her association with anti-apartheid activists, led to increasing police harassment. This compelled Bessie, now separated from her husband, to leave South Africa for Serowe, Botswana, with her infant son on a one-way exit permit (Cullinan & Cullinan, 2005; Eilersen, 2007). Bessie faced new challenges in Botswana, including feelings of ostracism and cultural alienation. In a letter to her friend and mentor Patrick Cullinan, a few months after arriving in Serowe, Bessie described how

[I]t’s possible to go for weeks and weeks without having a soul to speak to–to really speak to–about things other than bread and butter matters. I’ve had to work out a system of making myself tolerable to myself. It’s not so easy to face (Cullinan & Cullinan, 2005, p. 23).

In the same letter, she gave some insight into her process of self-discovery as a writer,

I’ve been forced to do a lot of re-thinking. If I write to you it’s only because I need an audience–a tonic–a relief from silence! Actual writing to some publisher, editor at the moment is beyond me. It’s no longer S. Africa and protest writing. Anyone can be justifiably indignant! How well I know that! But who am I? What the damned hell am I doing on this planet? Why? My consciousness inside me is such a heavy burden. (Cullinan & Cullinan, 2005, p. 23).

It was in this environment that she produced some of her most significant literary works, including When Rain Clouds Gather (1968), Maru (1971), and A Question of Power (1974). These works are profoundly autobiographical, reflecting the external challenges that catalyzed her internal emotional turbulence, which she transmuted into her writing (Eilersen, 2007; Head, 1975; Vigne, 1991). When Rain Clouds Gather explores themes of exile, resilience, and the clash between tradition and modernity in a rural African village, mirroring Bessie’s experiences of displacement in Botswana (Head, 1968; Vigne, 1991). Maru probes into the complexities of racial prejudice and the possibility of transcending social barriers, while A Question of Power, perhaps her most personal work, is a psychological exploration of a woman’s battle with mental illness, rooted in Bessie’s struggles with depression and her experiences of alienation in a foreign land (Cowling & Roberts, 2022; Cullinan & Cullinan, 2005; Eilersen, 2007; Head, 1971, 1974). Writing to Cullinan about the book, Bessie stated:

It is autobiographical and explains the peculiar state of torment I have lived in in Botswana, right up till this day […] I wrote the book in an appeal for help, thinking help would turn up-I don’t know in what form, but that someone would see the evil the way I see it and lift the burden off me. (Cullinan & Cullinan, 2005, p. 133).

Bessie’s experiences of marginalization, displacement, and identity conflict are recurrent themes in her literary output, reflecting the broader struggles of those who, like her, existed on the fringes of a society rigidly divided by race and gender (Mackenzie, 1989; Rafapa & Nengome, 2011). Her writing, much of which was produced during her exile in Botswana, serves as both a personal catharsis and a powerful commentary on the socio-political realities of her time, making Bessie a significant figure in African literature and a critical voice in the discourse on race, identity, and resilience in the face of systemic oppression (Mackenzie, 1989; Rafapa & Nengome, 2011).

Bessie’s later life was marked by increasing psychological challenges, including a severe breakdown in 1971 that led to her hospitalization in Botswana (Eilersen, 2007). Despite these difficulties, she continued to write, using her personal experiences to inform her literary work. However, her psychological well-being continued to deteriorate, and she faced significant challenges, including a failed citizenship application in Botswana and personal and professional disputes that exacerbated her sense of isolation (Cullinan & Cullinan, 2005; Eilersen, 2007; Vigne, 1991). During this time, Bessie planned her ambitious autobiography, which she envisioned as an epistle of self-exploration (Eilersen, 2007). Bessie’s relationships with mentors and friends provided some solace, but her sense of being an outsider remained pervasive.

Bessie died on 17 April 1986, in Serowe, Botswana, virtually destitute and alone, succumbing to hepatitis (Eilersen, 2007). Despite her struggles and societal challenges, her legacy as a writer endures. Her works offer profound insights into the complexities of race, identity, and the human condition, remaining vital contributions to African literature and a testament to her enduring spirit of resilience and creativity (Abrahams, 1990; Agbo, 2021; Lederer, 2019, 2022; Rafapa & Nengome, 2011; Seligman, 2021).

This research employs an integrative theoretical framework combining Donald W. Winnicott’s object relations theory with intersectional feminist theory to provide complementary perspectives, enabling a nuanced understanding of how Bessie’s identity, emotional struggles, and activism were shaped by both her early relational experiences and the broader socio-political context of apartheid and post-colonial Africa (Mayer, 2022; Ponterotto & Reynolds, 2019).

Winnicott’s object relations theory

Donald W. Winnicott’s object relations theory highlights how early relationships shape self-development. Key concepts from this theory—such as the holding environment, true and false self, potential space, and transitional objects—are essential in understanding Bessie’s life. The holding environment, for example, refers to the nurturing space provided by a caregiver that fosters emotional security and psychological growth (Bahn, 2022; Winnicott, 1964, 1975, 1986). In Bessie’s case, the absence of a stable holding environment—due to her abandonment and institutionalization—contributed to deep feelings of insecurity and fragmentation. These early experiences of relational failure led to the development of psychological mechanisms, evident in her later life and literary work, where themes of abandonment and identity confusion feature prominently (Bahn, 2022; Winnicott, 1964, 1975, 1986).

Winnicott’s concepts of the true self and false self would explain Bessie’s internal struggles. The true self reflects an individual’s authentic feelings and desires, while the false self develops in response to environmental failures, such as inadequate caregiving (Winnicott, 1965). For Bessie, the absence of consistent, nurturing care likely necessitated the construction of a false self as a protective strategy, allowing her to navigate a hostile and fragmented world. Her writing vividly illustrates this conflict, with characters often grappling with authenticity, identity, and the societal pressures that demand conformity (Summers, 2014; Vo, 2020).

Moreover, potential space—where creativity and self-exploration occur between the internal and external worlds—is essential in understanding Bessie’s engagement with writing (Seligman, 2021; Summers, 2014; Vo, 2020). For Bessie, writing provided a vital outlet to process her emotions, confront her fragmented identity, and assert her agency within the restrictive socio-political context of apartheid South Africa. Her literary works, such as A Question of Power and Maru, reflect her profound engagement with this creative space, offering insights into her personal and political struggles (Seligman, 2021; Summers, 2014; Vo, 2020).

Finally, transitional objects and phenomena refer to objects or activities that help individuals transition from dependence to independence (Winnicott, 1953). For Bessie, her relationships with mentors, friends, and literary communities likely functioned as transitional phenomena, offering support and emotional continuity in a world marked by displacement and marginalization (Caldwell, 2022; Summers, 2014; Vo, 2020; Winnicott, 1971). These relationships and her creative pursuits provided emotional sustenance and contributed to her resilience and personal growth (Caldwell, 2022).

Intersectional feminist theory

Intersectional feminist theory, pioneered by Crenshaw (1989), provides a critical framework for examining how multiple forms of discrimination—such as race, gender, and class—intersect, creating unique experiences of oppression and privilege. This theory emphasizes that social categories do not exist in isolation but are deeply interconnected, leading to compounded and complex effects on marginalized individuals (Collins, 2019; Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). In the context of Bessie’s life, intersectionality reveals how her identities as a biracial woman, an exile, and a writer interacted to shape her experiences of marginalization, resilience, and agency (Collins, 2019; Crenshaw, 1991).

Bessie’s experiences of systemic oppression—rooted in apartheid, patriarchal structures, and economic marginalization—can be fully understood through an intersectional lens. The apartheid regime discriminated based on race, while gendered and class-based oppression further compounded her marginalization (Abrahams, 1990; Cowling & Roberts, 2022). Intersectional feminism also illuminates how Bessie’s struggles were not confined to one axis of oppression; instead, they resulted from overlapping systems of inequality that shaped her identity and life choices (Cho et al., 2013; Collins, 2019, 2022). Her literary works critique these systems, offering a vision of social justice and human dignity transcending these divisions (Abrahams, 1990; Agbo, 2021; Cowling & Roberts, 2022).

A significant concept within intersectional feminism is the notion of chosen families—networks of friends, mentors, and communities providing emotional support outside biological or legal family structures (Jackson Levin et al., 2020; Lynch et al., 2022). For marginalized individuals like Bessie, who may face rejection from their biological families, chosen families offer critical emotional sustenance and a sense of belonging (Jackson Levin et al., 2020; Lynch et al., 2022). Bessie’s relationships with literary mentors and close friends provided the solidarity and affirmation that her biological family and broader society often failed to provide, helping her navigate the emotional and psychological challenges of marginalization (Jackson Levin et al., 2020; Lynch et al., 2022).

Goals of the Study and Research Question

This study aims to explore the psychological development and identity formation of Bessie Head within the socio-political context of apartheid and post-colonial Southern Africa. By applying psychobiographical methods through Winnicott’s object relations theory and intersectional feminist theory, the study examines how early relational disruptions and systemic marginalization shaped her identity, emotional life, and literary expression. The central research question guiding this study is: How did Bessie Head’s early life experiences influence her sense of identity and personality development as a racialised ‘other’ to become an eminent female writer in post-colonial Africa? This study addresses an existing disparity in South African psychobiographical research, which has primarily overlooked Black female historical figures (Fouché, 2015; Mayer, 2023a). Findings will illuminate the personal and psychological dimensions of Bessie’s life experiences within the broader systemic forces that influenced her creative and activist work.

This study employs a qualitative research design rooted in psychobiography to explore and understand Bessie’s life by applying Winnicott’s object relations theory and intersectional feminist theory. Psychobiography is a qualitative research method that seeks to understand the intricate relationship between an individual’s experiences and their psychological development, mainly focusing on historically significant figures (Burnell et al., 2019; du Plessis & Stones, 2019; Elms, 1994; Fouché & van Niekerk, 2005, 2010; Kőváry, 2018; Mayer & Kőváry, 2019). This approach is grounded in the belief that an individual’s life story is shaped by external and internal factors, including social and cultural contexts, family background, and personal experiences (Kőváry, 2018; Mayer et al., 2022; Mayer, 2023b; Schultz & Lawrence, 2017). Psychobiography aims to provide a comprehensive and nuanced exploration of an individual’s personality, motivations, and behaviours by employing psychological theories to interpret biographical data (Bulut & Usman, 2021; Mayer & Kőváry, 2019; Mayer et al., 2022).

This study relies on both primary and secondary data sources. Primary sources include Bessie’s autobiographical writings, letters, and recorded interviews, which offer direct insights into her thoughts, emotions, and experiences. Secondary sources include biographical accounts, scholarly articles, and other literature that provide contextual and interpretive analyses of Bessie’s life and work (du Plessis, 2017; Ponterotto & Reynolds, 2019). The data collection process involved thorough searches of academic databases, library archives, and the Amazwi South African Museum of Literature, which houses significant materials related to Bessie’s life.

The data collection process followed a structured approach inspired by du Plessis’ (2017) four-phase framework, integrated with Knight’s (2019) Phenomenological-hermeneutic Life-narrative Analysis (PLA). This combination facilitated a comprehensive examination of Bessie’s life, focusing on the psychological and socio-cultural dimensions of her experiences. The primary and secondary data were systematically analyzed using coding strategies to identify key themes and patterns that reflect Bessie’s identity formation and personality development (du Plessis, 2017).

Integral to this analysis was the rigorous application of Schultz’s (2005) criteria for identifying prototypical scenes that are pivotal in understanding the key moments that shaped Bessie’s psychological development. Prototypical scenes are distinguished by their vividness, specificity, and emotional intensity—qualities that make them particularly memorable and impactful (Schultz, 2005). By integrating Schultz’s (2005) criteria into the data collection and analysis process, the study selectively identified scenes that profoundly influenced Bessie’s personality development, ensuring that the data collected was rich in detail and significance. This approach allowed for a nuanced analysis of how these emotionally charged and multidimensional moments contributed to the formation of her identity and psychological landscape.

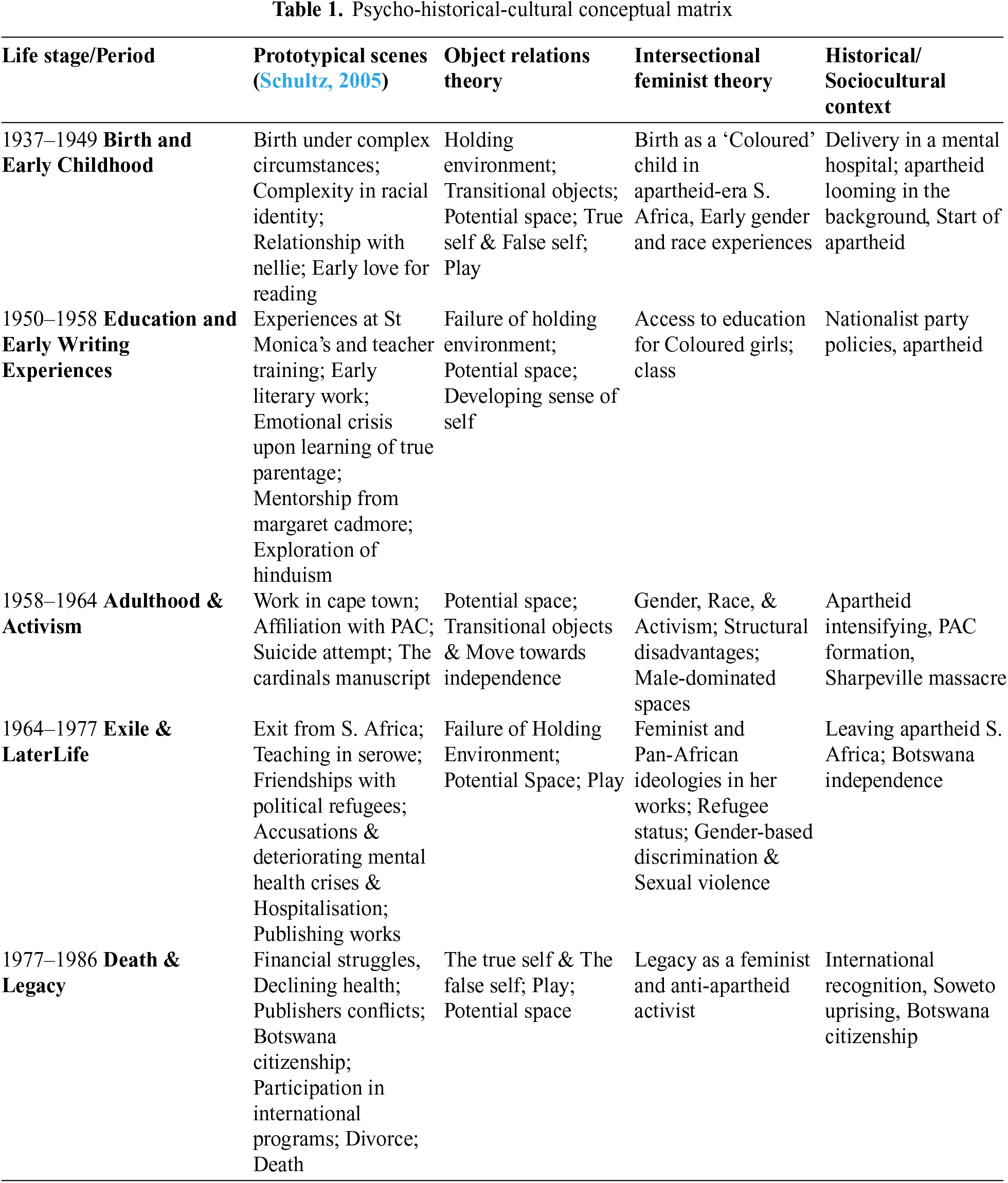

Following the methodologies outlined by Yin (2018) and Fouché (1999), Table 1 illustrates the structured framework used in this study to analyze Bessie’s life through a socio-historical lens. Guided by Schultz’s (2005) criteria for identifying prototypical scenes, this matrix correlates pivotal life stages, emotionally significant events, and relevant theoretical paradigms to comprehensively explore Bessie’s developmental trajectory–serving as a roadmap for understanding her life and a data collection and interpretation tool.

As the lead author, I identify as a person of mixed heritage, and my background significantly influenced my attraction to Bessie Head as a subject for psychobiographical study, given the parallels between her life experiences and those of my own family. Growing up in a mixed-heritage family, I was exposed to narratives of community acceptance struggles and identity conflicts, much like those Bessie faced. These personal connections resonated with Bessie’s life, which required careful management to maintain the academic rigour of my study (Knight, 2019). As second author, my positionality is one of White, middle class, female who was born in Southern Africa and exposed to diversity such as class, race, gender, and sexuality from a young age. My family and community were activists in dismantling racial injustice. Moving to South Africa as a young university student towards the end of Apartheid in the late 80s, opened me up further to the plight and injustice of institutional racism. The story of Bessie’s experiences of struggle to find her freedom and identity was additional conscious-raising experience and deepened my understanding of many people of similar circumstances and their search for equality and identity.

To mitigate the potential personal biases, we adopted a dual-strategy approach grounded in self-reflection and self-awareness. As Knight (2019) recommended, this approach involved acknowledging our “fore-structures of understanding” (p. 145)—the preconceived notions and biases stemming from our personal experiences—and striving to minimize their impact on our research. The necessity of self-reflection in academic research cannot be overstated. This process of reflexivity was critical in enhancing the validity and reliability of the study, ensuring that empathetic responses to Bessie’s story did not cloud an objective analysis (Grindler, 2021; Ponterotto & Moncayo, 2018).

Since Bessie is a deceased subject, the study adhered to ethical guidelines concerning the use of posthumous data. All sources used were publicly available, ensuring that the research did not intrude on private or sensitive areas of Bessie’s life that could cause harm to her legacy (Ponterotto & Reynolds, 2019; van Niekerk, 2021). The study was conducted following the ethical standards outlined by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (Health Professions Council of South Africa, 2016) and the American Psychological Association (American Psychological Association, 2017), as well as the ethical framework for psychobiographical research proposed by Ponterotto and Reynolds (2019).

This section explores the key themes that emerged from the psychobiographical analysis of Bessie’s life: (1) Identity and Self-Understanding, (2) Emotional and Mental Health, (3) Activism and Social Inequality, and (4) Personal Relationships and Community. These are discussed next, along with the evidence for them.

Identity and self-understanding

A fragmented and unstable holding environment marked Bessie’s early life. Born to a White mother and a Black father in apartheid South Africa, her very existence defied the rigid racial categories of the time. From her earliest years, Bessie was exposed to an environment that could not offer her the emotional security and stability she needed. Winnicott (1975, 1986) posits that the holding environment, provided by a consistent and nurturing caregiver, is critical to developing a cohesive sense of self. In Bessie’s case, this environment was marked by abandonment and rejection, which contributed to a deep sense of insecurity and fragmentation.

This sense of displacement was further compounded by the intersectional factors of race, gender, and class (Collins, 2019; Crenshaw, 1991). As a Coloured individual, Bessie was situated in a liminal space within South African society, where she was not fully accepted by the Black or White communities (Mafe, 2013). This placed her in what Winnicott (1971) might describe as a potential space, a realm of psychological ambiguity where her identity was neither fixed nor fully formed. Intersectional feminist theory helps to explain how these overlapping systems of oppression—rooted in race, gender, and class—further complicated her identity development as she navigated multiple layers of marginalization (Collins, 2019).

A critical moment in Bessie’s identity formation occurred during her teenage years when she discovered the truth about her biological parents, shattering the foundation of her self-perception. Winnicott’s (1953) concept of transitional objects, typically used to stabilize a person’s emotional world during distress, becomes relevant here. Bessie’s race, family, and social status, which could have functioned as stabilizing elements, were sources of ambiguity and emotional turmoil. This led to an identity crisis in which Bessie was forced to confront the realities of her marginalized status and redefine her sense of self (Eilersen, 2007).

Bessie’s involvement in political activism also played a crucial role in her identity development. Winnicott (1963, 1975) describes achieving independence as a critical stage in personal development. For Bessie, her activism became a way of asserting her individuality and agency in a hostile socio-political environment. Her alignment with political movements reflected her desire to fight for justice and establish her identity within a broader socio-political struggle. Intersectional feminism illuminates how Bessie’s activism was intricately tied to her complex identity as a woman of mixed race and how her involvement in political movements was a means of resisting the multiple forms of oppression she faced (Burnell & Nel, 2022; Cowling & Roberts, 2022).

Bessie’s exile to Botswana marked a significant shift in her identity journey. As she adjusted to life in a new country, she found herself again navigating a fractured holding environment (Winnicott, 1975). The psychological impact of exile, coupled with her already fragile sense of self, forced Bessie to confront new layers of identity as a refugee. Her sense of self was further fragmented by the realities of living in a foreign land, where she faced new forms of marginalization (Ibrahim, 1996; Crenshaw, 1991). Winnicott’s (1971) concept of potential space becomes again relevant, as Bessie’s intellectual and creative life provided her with a means of navigating this uncertainty and forging a new identity in the face of continued displacement.

In Bessie’s early adulthood, the failure of her holding environment becomes apparent. According to Winnicott (1975), a secure holding environment fosters a stable sense of self, but Bessie’s lack of nurturing care in her childhood led to emotional fragility. Without a consistent emotional foundation, she was vulnerable to fluctuating self-esteem, an unstable identity, and frequent episodes of emotional distress (Winnicott, 1975; Bahn, 2022). Her activism, which emerged during this period, further intensified her emotional vulnerability. Intersectional feminism highlights how Bessie’s position as a Coloured woman intersected with systemic racism and sexism, compounding her marginalization (Collins, 2019; Crenshaw, 2017). She faced unique challenges navigating both racial and gender oppression, and the activism that sought to address these inequalities also deepened her emotional turmoil. As a result, her emotional volatility was not merely a personal trait but a reflection of the hostile environments she inhabited.

While crucial for her political engagement, Bessie’s activism did not offer a space for emotional healing. It exposed her to more alienation from societal norms, further destabilizing her internal emotional world. Movements for racial justice were often male-dominated, marginalizing her voice as a woman (Crenshaw, 2017). Simultaneously, gender equality movements frequently failed to address the racial disparities Bessie confronted (Crenshaw, 2017). These overlapping systems of oppression left her struggling to find a stable emotional ground, perpetuating her psychological instability. Her activism became a dual-edged sword—critical for her identity and a source of deeper emotional conflict.

Exile introduced a new phase in Bessie’s emotional journey. Winnicott’s (1971) concept of potential space—an area for identity exploration and emotional growth—applies to her time in Botswana. While exile offered Bessie an opportunity for self-discovery, it was fraught with challenges. Her suicide attempt marked a critical moment when her potential space threatened to collapse into a psychological void rather than fostering growth (Roitman, 2021). The precarious balance between emotional healing and disintegration mirrored the contradictions in her life. Bessie’s writings during this period reflect this tension as she grappled with the duality of emotional growth and potential disintegration.

Her later years were marked by a continued decline in mental health, exacerbated by deteriorating relationships and professional disputes (Davis, 2018). Bessie’s attempt to write her autobiography seemed like an effort to reclaim her narrative, a therapeutic process that allowed her to assert some control over her rapidly disintegrating identity (Winnicott, 1971). This effort can be seen as a final attempt to create emotional stability through self-expression despite the deteriorating state of her mental and physical health (Seligman, 2021). Bessie’s indomitable spirit allowed her to continue writing, advocating, and connecting with others, carving out her form of potential space even amidst emotional instability.

Activism and social inequality

As Bessie entered adulthood, her activism became more pronounced. This activism represented a movement towards both personal and societal freedom, aligning with Winnicott’s (1963, 1975) concept of moving towards independence. Her involvement with the anti-apartheid movements was a powerful statement of her political liberation. However, as a Coloured woman, Bessie’s activism was marked by additional struggles that her White and male counterparts did not experience. Intersectional feminism explains how her activism was shaped by the overlapping oppressions of race and gender (Crenshaw, 2017; Nash, 2008). In addition to confronting apartheid, Bessie had to contend with the marginalization of women within resistance movements and the racial hierarchies that limited solidarity within these communities (Crenshaw, 2017). This dual struggle complicated her activism and required her to navigate multiple forms of inequality.

During her exile in Botswana, Bessie’s relationships with political refugees and the broader diaspora added complexity to her emotional life. Winnicott’s (1971) concept of play provides a valuable framework for understanding her activism during this phase. Bessie’s activism became a form of creative engagement in Botswana—a space to explore her complex ideological identity and express herself safely. Play, in this sense, allowed Bessie to engage with the world creatively, fostering emotional well-being and personal development (Winnicott, 1971). Her activism in exile thus served as a political and psychological outlet, enabling her to process her struggles.

In later years, Bessie’s introspective writing transcended anti-apartheid activism and feminist resistance, reflecting deeper on social inequality (Abrahams, 1990; MacKenzie, 1989). Through the lens of intersectional feminism, Bessie’s work highlights the interconnected systems of oppression she confronted, and her writings provide a lasting contribution to the dialogue on social justice (Jeyadharshini & Gnanaprakasam, 2022). Her literary legacy extends beyond the specific context of apartheid and feminism, addressing broader issues of systemic inequality (Jeyadharshini & Gnanaprakasam, 2022).

Personal relationships and community

To fully understand Bessie’s life, her personal relationships and community connections, we explore these through psychological and socio-political lenses. Bessie’s early life was marked by the absence of a stable holding environment, which, according to Winnicott (1975, 1986), left Bessie emotionally vulnerable and hesitant to trust others fully (Bahn, 2022; Winnicott, 1975). This emotional instability meant that she approached relationships with insecurity, seeking connections that could provide her with emotional sustenance, even if they were unconventional. Bessie’s relationships with her mentors and friends were emotional anchors during her turbulent life. These bonds, while important, also functioned as transitional objects—temporary sources of comfort rather than lasting emotional security (Winnicott, 1953, 1969). Her reliance on such relationships reflects Winnicott’s idea that individuals often use objects or relationships to manage emotional instability, particularly in the absence of a stable holding environment.

From an intersectional feminist perspective, Bessie’s relationships highlight the importance of chosen families. Traditional family structures did not give her the emotional support she needed, so she formed meaningful bonds outside conventional frameworks. These chosen families became vital sources of emotional support, demonstrating the transformative power of non-traditional relationships, especially for those marginalized by race, gender, and social status (Jackson Levin et al., 2020; Lynch et al., 2022).

Bessie’s sense of isolation extended to her relationship with the broader community, particularly when her application for Botswana citizenship was rejected. This rejection amplified her feelings of being an outsider, further complicating her sense of belonging in society (Cullinan & Cullinan, 2005; Eilersen, 2007; Vigne, 1991). This denial reinforced her alienation in a cultural context where community acceptance is crucial (Lederer, 2019). However, Winnicott’s (1971) concept of potential space offers another perspective: Bessie’s writing became her personalized holding environment, where she could confront her challenges safely and explore her inner world.

Her writing also served as a medium for social engagement, allowing her to address issues of social inequality and community expectations. Through the lens of intersectional feminism, we see how Bessie’s multiple marginalized identities shaped her experiences and challenges (Collins, 2019; Crenshaw, 2017). Despite the absence of a nurturing environment and the complex intersections of her identity, Bessie exhibited resilience, finding emotional anchors in her chosen relationships and work. These elements gave her potential spaces to assert her voice, foster dialogue, and create meaning (Vo, 2020).

Implications for theory and research

By integrating Winnicott’s object relations theory and intersectional feminist theory, this research provides a holistic framework for understanding Bessie’s life. Winnicott’s focus on early relational experiences explains the psychological consequences of Bessie’s abandonment and relational deficits. At the same time, intersectional feminism highlights the external socio-political forces—such as apartheid, sexism, and economic marginalization—that shaped her identity formation and personality development. This combined framework enables a comprehensive exploration of how Bessie’s internal psychological struggles intersect with broader systems of oppression, contributing to her lifelong quest for identity and belonging. This integrative approach underscores the importance of combining intrapersonal and systemic perspectives in psychobiographical research (Burnell & Nel, 2022). It provides a more comprehensive understanding of how marginalized individuals navigate and resist oppressive structures throughout their lives (Burnell & Nel, 2022).

Limitations and suggestions for further research

One limitation of this study is that the psychobiographical analysis may have inadvertently overlooked some significant aspects of Bessie’s complex identity and personality development. In a previous section, we noted how our personal experiences may have introduced certain biases or blind spots in our interpretation of the findings. Additionally, this study’s primary and secondary sources were limited to those accessed through academic databases and archival research, potentially excluding unpublished or less accessible materials that could have further enriched the analysis.

Another limitation lies in the specific theoretical frameworks used—Winnicott’s object relations theory and intersectional feminist theory. While these frameworks provided a robust structure for analyzing Bessie’s life, they are not exhaustive. Other psychological or socio-political theories, such as Jungian archetypes or post-colonial theory, could offer alternative insights and interpretations, particularly in understanding the symbolic dimensions of Bessie’s literary work or her broader socio-cultural impact.

Future research could address these limitations by incorporating a more comprehensive range of sources, including unpublished letters, interviews with contemporaries, or archival materials inaccessible for this study. Additionally, future psychobiographies might benefit from a comparative approach, examining the lives of other biracial individuals or prominent African writers who navigated similar socio-political landscapes. A comparative approach could help contextualize Bessie’s experiences within a broader framework and potentially reveal commonalities or differences that would enhance our understanding of the impact of systemic oppression on identity formation.

Finally, expanding the theoretical frameworks to include other perspectives, such as those from African-centered psychology or narrative theory, could provide a more holistic understanding of Bessie’s life and work. Such approaches would enrich the analysis and contribute to the ongoing discourse on the intersection of psychology, literature, and cultural identity in African contexts.

This psychobiographical study has provided a nuanced and multidimensional understanding of Bessie Head’s life, illustrating how her personal experiences of abandonment, marginalization, and emotional struggle were intertwined with the socio-political realities of apartheid and post-colonial Africa. By applying Winnicott’s object relations theory and intersectional feminist theory, the research sheds light on the complex interplay between Bessie’s early psychological development and the broader systemic forces that shaped her identity formation, psychological development, and artistic output.

Psychobiography as a method offers unique insights into how both internal dynamics and external socio-political forces shape an individual’s life trajectory. In Bessie Head’s case, early relational disruptions and institutionalization compounded her experiences of marginalization. Her identity and resilience were forged in response to these early deficits, as well as the harsh realities of apartheid, exile, and the ongoing search for belonging. Moreover, Bessie’s life highlights the critical role that creativity and activism play in navigating and resisting systemic oppression. Her literary works, deeply influenced by her psychological struggles and socio-political context, are powerful expressions of resilience and agency. This study underscores the importance of psychobiographical research in expanding our understanding of how lives unfold in response to both internal psychological dynamics and external societal forces.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Adeline T. Kingsley; data collection: Adeline T. Kingsley; analysis and interpretation of results: Adeline T. Kingsley, Zelda G. Knight; draft manuscript preparation: Adeline T. Kingsley, Zelda G. Knight. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new statistical data was created or analyzed in this study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Abrahams, C. A. (Ed.). (1990). The tragic life: Bessie Head and literature in Southern Africa. Trenton, NJ: Africa Research and Publications. [Google Scholar]

Agbo, J. (2021). Bessie Head and the Trauma of Exile: Identity and alienation in Southern African Fiction. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Al-Ghalith, A., Nashwan, A., Al-Ghammaz, S. A. D., Alzghoul, M., & Al-Salti, M. (2023). The treatment of women in selected works by Bessie Head. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 14(4) , 968–976. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.1404.14 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (including 2010 and 2016 amendments). Washington, DC: Author. Available from: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index. [Google Scholar]

Arendse, D. E. (2021). Culture as a colonial hub: My reflections as a ‘coloured’ [Woman] in post-Apartheid South Africa. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 42(4) , 515–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2021.1939281 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bahn, G. H. (2022). Understanding of holding environment through the trajectory of Donald Woods Winnicott. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(4) , 84. https://doi.org/10.5765/jkacap.220022 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bulut, S., & Usman, A. C. (2021). Psychobiography: Understanding concepts, steps, and procedures in the study of lives. Problems of Psychology in the 21st Century, 15(1) , 7–17. https://doi.org/10.33225/ppc/21.15.07 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Burnell, B., & Nel, C. (2022). A comparative psychobiographical exploration of the role of generativity in meaning making for two women in the anti-apartheid movement. In: C.-H. Mayer, J. P. Fouché & R. Van Niekerk (Eds.Psychobiographical illustrations on meaning and identity in socio-cultural contexts (pp. 97–117). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

Burnell, B., Nel, C., Fouché, P. J., & van Niekerk, R. (2019). Suitability indicators in the study of exemplary lives: Guidelines for the selection of the psychobiographical subject. In: C. H. Mayer & Z. Kőváry (Eds.New trends in psychobiography (pp. 173–193). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Caldwell, L. (2022). A discussion of three versions of Donald Winnicott’s ‘Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena’, 1951–1971. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 38(1) , 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12700 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4) , 785–810. https://doi.org/10.1086/669608 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Collins, P. H. (2019). Intersectionality as critical social theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

Collins, P. H. (2022). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Cowling, L., & Roberts, S. (2022). The non-conformist writing of olive schreiner, Noni Jabavu, and Bessie Head. In: J. S. Bak & B. Reynolds (Eds.The routledge companion to world literary journalism (pp. 59–73). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1) . [Google Scholar]

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6) , 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Crenshaw, K. W. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. New York, NY: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

Cullinan, P., & Cullinan, W. (2005). Imaginative trespasser: Letters between Bessie Head and Patrick and Wendy Cullinan, 1963–1977. Johannesburg, South Africa, Trenton, NJ: Wits University Press, Africa World Press. [Google Scholar]

Davis, C. (2018). A question of power: Bessie Head and her publishers. Journal of Southern African Studies, 44(3) , 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2018.1445354 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

De Luca Picione, R. (2015). The idiographic approach in psychological research: The challenge of overcoming old distinctions without risking to homogenize. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 49(3) , 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12124-015-9307-5 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

du Plessis, C., (2017). The method of psychobiography: Presenting a step-wise approach. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 14(2) , 216–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2017.1284290 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

du Plessis, C., & Stones, C. R. (2019). The use of unusual psychological theories in psychobiography: A case study and discussion. In: C. H. Mayer Z. Kőváry (Eds.New trends in psychobiography (pp. 209–227). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Eilersen, G. S. (2007). Bessie Head: Thunder behind her ears. Johannesburg, South Africa: Wits University Press. [Google Scholar]

Ellison, G. T., & de Wet, T., (2020). The classification of South Africa’s mixed-heritage peoples 1910–2011: A century of conflation, contradiction, containment, and contention. In: Z. L. Rocha, P. J. Aspinall (Eds.The palgrave international handbook of mixed racial and ethnic classification (pp. 425–455). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Elms, A. C. (1994). Uncovering lives: The uneasy alliance of biography and psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Fouché, J. P. (1999). The Life of Jan Christiaan Smuts: A psychobiographical study [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Port Elizabet. [Google Scholar]

Fouché, P. (2015). The ‘coming of age’ for southern African psychobiography. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 25(5) , 375–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2015.1101261 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fouché, J. P., & van Niekerk, R., (2010). Academic psychobiography in South Africa: Past, present and future. South African Journal of Psychology, 40(4) , 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124631004000410 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fouché, J. P., & van Niekerk, R. (2005). Psychobiography: An interdisciplinary approach between psychology and biography in the narrative reconstruction of personal lives. Port Elizabeth, South Africa: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. [Google Scholar]

Grindler, Y. (2021). A psychobiographical study of Elie Wiesel: Our brother’s keeper [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Johannesburg. [Google Scholar]

Harrison, J., & Watermeyer, B. (2019). Views from the borderline: Extracts from my life as a coloured child of Deaf adults, growing up in apartheid South Africa. African Journal of Disability, 8(1) , 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v8i0.473 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Head, B. (1968). When rain clouds gather. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

Head, B. (1971). Maru. London, UK: Gollancz. [Google Scholar]

Head, B. (1974). A question of power. London, UK: Davis-Poynter. [Google Scholar]

Head, B. (1975). Dear Tim, will you please come to my birthday party?. In: D. Barber (Ed.One parent families (pp. 106–111). London, UK: Davis-Poynter. [Google Scholar]

Health Professions Council of South Africa (2016). Guidelines for good practice: General ethical guidelines for health care professionals (Booklet 1). Pretoria, South Africa: Health Professions Council of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

Henrico, R., & Fick, S. (2019). The state of emergency under the South African Apartheid System of Government: Reflections and criticisms. Zeitschrift Für Menschenrechte, 13(2) , 71–97. https://doi.org/10.46499/1411.2364 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ibrahim, H. (1996). Bessie Head: Subversive identities in exile. University of Virginia Press. [Google Scholar]

Jackson Levin, N., Kattari, S. K., Piellusch, E. K., & Watson, E. (2020). We just take care of each other: Navigating ‘chosen family’ in the context of health, illness, and the mutual provision of care amongst queer and transgender young adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19) , 7346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197346 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jeyadharshini, X. A. L., & Gnanaprakasam, V. (2022). Subjugation and exploitation of the marginalized African women in the select works of Bessie Head. Specialusis Ugdymas, 1(43) , 6751–6763. [Google Scholar]

Knight, Z. G. (2019). The case for the psychobiography as a phenomenological-hermeneutic case study: A new phenomenological-hermeneutic method of analysis for life-narrative investigations. In: C.-H. Mayer & Z. Kőváry (Eds.New trends in psychobiography (pp. 133–153). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Kőváry, Z. (2018). Life history, clinical practice and the training of psychologists: The potential contribution of psychobiography to psychology as a “rigorous science”. International Journal of Psychology and Psychoanalysis, 4(1) , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845319867425 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lederer, M. S. (2019Conversation with Bessie Head. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

Lederer, M. S. (2022). Bessie Head: A world writer from Africa. In: H. O. Chukwuma & C. C. Opara (Eds.Legacies of departed african women writers: Matrix of creativity and power (pp. 153–166). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

Lynch, S., Davies, L., Ahmed, D., & McBean, L. (2022). Complicity, trauma, love: An exploration of the experiences of LGBTQIA+ members from physical education spaces. Sport, Education and Society, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2022.2141216 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

MacKenzie, C. (1989). Bessie Head. An introduction. Grahamstown, South Africa: National English Literary Museum. [Google Scholar]

Mafe, D. A. (2013). “An unlovely Woman”: Bessie Head’s mulatta (Re) vision. In: D. A. Mafe (Ed.Mixed race stereotypes in South African and American literature: Coloring outside the (Black and White) lines (pp. 57–83). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. [Google Scholar]

Mayer, C.-H. (2022). Psychobiographical trends: Untold stories and international voices in the context of social change. Journal of Personality, 91(1) , 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12771 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mayer, C.-H. (2023a). Graça simbine machel: A psychobiography of an ultra-committed change-maker and global woman activist. In: C.-H. Mayer, R. van Niekerk P. J. Fouché, J. G. Ponterotto (Eds.Beyond WEIRD: Psychobiography in times of transcultural and transdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 117–135). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Mayer, C.-H. (2023b). Psychobiographical trends: Untold stories and international voices in the context of social change. Journal of Personality, 91(1) , 262–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12771 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mayer C.-H., Fouché, P. J., & van Niekerk, R. (2021). Editorial: Psychobiographical illustrations on meaning and identity in socio-cultural contexts. In: C. -H. Mayer, P. J.Fouché, R. van Niekerk (Eds.Psychobiographical illustrations on meaning and identity in socio-cultural contexts (pp. 1–19). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

Mayer, C.-H., Fouché, J. P., & van Niekerk, R. (Eds.). (2022). Psychobiographical Illustrations on Meaning and Identity in Socio-Cultural Contexts. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

Mayer, CH., & Kőváry, Z. (Eds.). (2019New trends in psychobiography. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Mayer, C.-H., van Niekerk, R., Fouché, P. J., & Ponterotto, J. G. (Eds.). (2023). Beyond WEIRD: Psychobiography in times of transcultural and transdisciplinary Perspectives. Springer. [Google Scholar]

McAdams, D. P. (2018). McAdams in interview with Claude-Hélène Mayer. In: Mayer C. -H., & Kőváry (Eds.New trends in psychobiography (pp. 79–93). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Nash, J. C. (2008). Re-thinking intersectionality. Feminist Review, 89(1) , 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2008.4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ponterotto, J. G. (2014). Best practices in psychobiographical research. Qualitative Psychology, 1(1) , 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ponterotto, J. G., & Moncayo, K. (2018). A cautious alliance: The psychobiographer’s relationship with her/his subject. Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 18(sup1) , 97–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2018.1511311 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ponterotto, J. G., & Park-Taylor, J. (2021). Careerography: Application of psychobiography to career development. Journal of Career Development, 48(1) , 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845319867425 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ponterotto, J. G., & Reynolds, J. D. (2019). An ethics guide to psychobiography: A best practice model. In: C. H.Mayer, & Z. Kőváry (Eds.New trends in psychobiography (pp. 55–78). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Rafapa, L. J., & Nengome, A. Z. (2011). Instances of Bessie Head’s distinctive feminism, womanism and Africanness in her novels. Tydskrif Vir Letterkunde, 48(2) , 112–121. https://doi.org/10.4314/tvl.v48i2.68306 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Roitman, Y. (2021). Soldering Abyss: The intersubjective roots of the sense of the void. Rereading clinical case reported by winnicott. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 31(6) , 703–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/10481885.2021.1976185 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schultz W. T. (2005). Introducing psychobiography. In: W. T. Schultz (Ed.Handbook of psychobiography (pp. 3–18). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Schultz, W. T., & Lawrence, S. (2017). Psychobiography: Theory and method. American Psychologist, 72(3) , 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000130 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Seekings, J. (2021). The social question in pre-apartheid South Africa: Race, religion and the state. In: L.Leisering (Eds.One hundred years of social protection: The changing social question in Brazil, India, China, and South Africa (pp. 191–220). Cham: Palgrave Mcmillan. [Google Scholar]

Seligman, S. (2021). Reconstructing the depressive position: Creativity and style in Winnicott’s “Concern” paper. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 69(3) , 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/00030651211022659 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Summers, F. (2014). Object relations theories and psychopathology: A comprehensive text (2nded.). New York, NY: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

van der Pol, N., Essack, Z., Viljoen, M., & van Rooyen, H., (2022). Strategies employed by biracial people when encountering unofficial racial census-takers in post-apartheid South Africa. In: G. Houston, M. Kanyane, Y. D. Davids (Eds.Paradise lost (pp. 269–285). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. [Google Scholar]

van Niekerk, R. (2021, October 21). Psychobiographical perspectives on the development and manifestation of extraordinary human achievements [Inaugural Lecture]. Retrieved from: https://lectures.mandela.ac.za/lectures/media/Store/documents/Inaugural%20lectures/Prof-R-van-Niekerk-full-lecture.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Vigne, R. (1991). A gesture of belonging: Letters from Bessie Head, 1965–1979. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

Vo, P. (2020). Swimming with Winnicott: An ode to the spirit of creativity, inquiry and learning. Psychoanalytic Social Work, 27(2) , 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228878.2020.1816183 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Winnicott, D. (1953). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 34, 89–97 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Winnicott, D. W. (1963). The development of the capacity for concern. In: D. W. Winnicott (Ed.The maturational processes and the facilitating environment (vol. 1965, pp. 83–92). New York, NY: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

Winnicott, D. W. (1964). The child, the family and the outside world. London, UK: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

Winnicott, D. W. (1965). The maturational processes and the facilitating environment. New York, NY: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

Winnicott, D. W. (1969). The use of an object. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 50, 711–716. [Google Scholar]

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. London, UK: Tavistock. [Google Scholar]

Winnicott, D. W. (1975). Collected papers: Through pediatrics to psychoanalysis (2nd ed.London, UK: Tavistock Publications. [Google Scholar]

Winnicott, D. W. (1986). Home is where we start from: Essays by a psychoanalyst. London, UK: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

Yengde, S. (2021). Indians in Apartheid South Africa: Class, compromise, and controversy in the era of the Group Areas Act, 1952–1962. Diaspora Studies, 14(1) , 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09739572.2020.1816801 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and Applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools