Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The association between social support and decent work among rural primary school teachers: A chain mediation model

1 Students Affairs Office, Sanming University, Sanming, 365004, China

2 Faculty of Social Science and Liberal Arts, UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur, 56000, Malaysia

3 School of Education Science, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, 210024, China

* Corresponding Author: Jiajian Wang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 223-230. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068063

Received 21 January 2025; Accepted 03 May 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

Amidst the unique challenges faced by rural educators is their sense of decent work influenced by levels of social support, career self-efficacy, and marginalization. To investigate these relationships, we surveyed 435 rural school teachers (females = 69.32%, mean years teaching experience = 13.6, SD = 7.7 years). The Structural Equation Modeling results indicated that social support positively predicts teachers’ perceptions of decent work. Career self-efficacy mediated the relationship between social support and a higher sense of decent work, while marginalization mediated the relationship such that lower social support predicted lower perceptions of decent work. Career self-efficacy and marginalization also had a sequential mediation relationship: higher social support enhanced career self-efficacy, which in turn reduced marginalization experiences, ultimately improving teachers’ perceptions of decent work. These findings align with the predictions of Social Cognitive Career Theory and the Psychology of Working Theory, demonstrating that environmental supports enhance personal psychological resources, reduce marginalization risks, and promote positive work-related outcomes. The study findings highlight the necessity for education departments to improve rural teachers’ perceptions of decent work by providing social support to foster positive work experiences for teachers at high risk for marginalization and diminished career self-efficacy.Keywords

Across occupations, people desire decent work to enhance their quality of work life. The concept of decent work is closely related to an individual’s career development, including job satisfaction, turnover intention, work motivation, and career commitment (Wei & Duffy, 2022; Xu et al., 2022). At the same time, social support makes a difference in how individuals manage their work lives (Taylor, 2011). Similarly, career self-efficacy (CSE) influences career beliefs, career adaptability, decent work perception, and career decision-making processes (Chan, 2020; Duffy et al., 2016; Hou et al., 2019). Conceivably, with higher social support, people have a sense of decency in their work lives, although this may vary in unknown ways by their career self-efficacy and sense of marginalization or deprivation.

Although substantial research has been conducted on decent work among various populations, such as blue-collar workers, urban employees, and minority groups, limited attention has been given to rural primary school teachers (Kekana et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2023). Given this gap, conducting in-depth research on rural primary teachers holds significant theoretical and practical significance.

Theoretical foundations. Social Cognitive Career Theory (SCCT) proposes an interplay among environmental factors, such as learning experiences and social support, individual psychological traits, and behavioral outcomes (Lent et al., 2002). Within this theory, Career Self-Efficacy is a core concept in shaping an individual’s career decisions, career beliefs, and work attitudes (Chan, 2020; Lent et al., 1994; Lent et al., 2019). Additionally, CSE is influenced by factors such as social support and learning experiences (Bassi et al., 2007; Orakci et al., 2022). Hence, when teachers have greater social support, their CSE would also increase. This heightened CSE enhances their personal beliefs in their ability to perform the teaching tasks they face, which, in turn, positively influences their perceptions of decent work. Moreover, by their socio-cognitive assets, people may experience less marginalization or a sense of derogation of social status (Ma et al., 2019). In the Psychology of Working Theory (PWT), a sense of marginalization would negatively affect decent work lives (Duffy et al., 2021). Therefore, we propose that when rural teachers lack social support, they are more likely to feel marginalized, thereby affecting their perception of decent work.

Social Support and Decent Work

Within the SCCT framework, social support includes encouragement, information sharing, and advice important to people’s work motivations, interests, and abilities, which would extend to a sense of decent work experiences (Lent et al., 2022). Decent work comprises five components: safe working conditions, access to healthcare, fair compensation, leisure time during the workweek, and alignment of workplace values with home life (Duffy et al., 2016). Perception of decent work predicted their overall well-being and job satisfaction (Alfa et al., 2023; Blustein et al., 2020; Kozan et al., 2019; McIlveen et al., 2021), as well as work volition and career adaptability (Blustein et al., 2016). Perception of decent work was often constrained by marginalization experiences (Wang & Chang, 2025).

CSE includes factors such as social support, role models, and career exploration and decision-making learning experiences (Chan, 2020; Ireland & Lent, 2018; Rivera et al., 2007) for guiding career decisions and behaviors (Lent, 2002). Individuals with high CSE are more inclined to proactively pursue challenging career objectives, persevere in their efforts, and ultimately experience greater job satisfaction (Bandura, 2012; Perera et al., 2022). Conversely, individuals with low CSE may be more susceptible to feelings of discouragement and a tendency to withdraw from career pursuits. CSE mediated the relationship between calling and career outcome expectations (Domene, 2012) and career exploration (Zhang & Huang, 2018).

Marginalization is associated with employment discrimination, economic inequality, and social exclusion (Blustein et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2016). Rural teachers are at higher risk for marginalization. This is primarily due to the challenges typically encountered in rural areas, such as limited educational resources, relatively low socioeconomic status, a lack of professional development opportunities, and the remote geographical locations of schools (Sargent & Hannum, 2005). Marginalization often involves limitations on job opportunities and instability in social status, which can impact how individuals perceive decent work (Duffy et al., 2020).

CSE and marginalization chain mediation

Higher CSE instills greater confidence in individuals to confront career challenges and actively seek good work, consequently enhancing their prospects for attaining such employment (Chan, 2020). Conversely, marginalization may erode an individual’s CSE, leading them to perceive a lack of value and opportunities within the occupational sphere, thereby diminishing their motivation to seek decent work (Blustein et al., 2019). Social support plays a pivotal role in this process. It can aid in strengthening an individual’s CSE by offering emotional, informational, and resource-based support, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of marginalization on CSE. Consequently, social support can act as a mediating factor in the relationship between CSE and the pursuit of decent work by elevating an individual’s CSE.

The Chinese rural teaching context

As of 2022, there were 2.2 million rural teachers in China, constituting 25% of the total teaching workforce (Wu & Qin, 2023). Additionally, the number of students in non-urban compulsory education in China reached 93.208 million, approximately 60% of the total compulsory education enrollment in the country (Fu & Liu, 2022). This data indicated that rural teachers carried a substantial teaching workload. Furthermore, previous research has shown that many of these teachers desire to leave their positions. Specifically, approximately 30% of teachers consistently express a desire to resign, and about 52% of teachers indicated a moderate to strong intention to resign (Wang, 2023). Rural teachers in China have been deeply rooted in grassroots education for years. However, due to poor working conditions, limited social resources, underdeveloped local economies, and limited interaction with a less diverse population, these factors often make rural primary teachers feel marginalized (Zhou, 2020).

Goals of the study. We aimed to examine the perception of decent work among Chinese rural primary teachers by their sense of social support, career self-efficacy and marginalization. (see Figure 1). We tested the following hypotheses.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework. Note. SS: Social Support, CSE: Career Self-efficacy, M: Marginalization, DW: Decent Work.

Hypothesis 1: Social support is positively related to decent work.

Hypothesis 2: CSE mediates the relationship between social support and decent work.

Hypothesis 3: Marginalization mediates the relationship between social support and decent work.

Hypothesis 4: CSE and marginalization mediate the relationship between social support and decent work.

The participants were 435 rural school teachers, of whom 69.32% were female. In terms of age distribution, 28.84% of the teachers were aged 30 years or younger, 19.41% were between 31 and 40 years old, 30.13% were between 41 and 50 years old, and 21.63% were aged 51 years or older. Regarding marital status, 76.71% of the participants were married, while 23.29% were unmarried.

Social support. To assess participants’ perceived social support, we utilized the 22-item Chinese Social Support Questionnaire (CSSQ, Liu, 2010). This scale comprises three distinct dimensions: family support (7 items), friend support (12 items), and other support (3 items). Sample items include statements such as “My family provided emotional support when I needed it”, “I have friends who assist me during times of trouble”, and “I have someone to offer guidance in my work or studies”. Respondents rate their level of agreement on a scale ranging from 1 to 5, where 1 corresponds to “never” and 5 corresponds to “always”. Higher scores on the scale indicated a greater level of perceived social support. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for CSSQ scores was 0.981, indicating strong internal consistency.

Career self-efficacy. To measure participants’ CSE, we employed the 12-item Teacher Efficacy Scale (TSE, Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). Sample items from each of the three subscales include statements such as “Being able to stop disruptive student behavior in the classroom”, “Being able to encourage students who are not interested in learning”, and “Being able to assess students from multiple perspectives”. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represents ‘never’ and 5 represents ‘very much’. Higher scores on this scale were indicative of greater teacher self-efficacy. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for TES scores was 0.968, indicating strong internal consistency.

Marginalization. To assess participants’ perceptions of marginalization experiences, we utilized the 3-item Lifetime Experiences of Marginalization Scale (LEMS, Duffy et al., 2019). An example item from the scale was “During my lifetime, I have had many interpersonal interactions that have often left me feeling marginalized”. Items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating “Strongly Disagree” and 7 indicating “Strongly Agree”. Higher scores on this scale signified a greater degree of perceived marginalization. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the LEMS in the present study was 0.943.

Decent work. To assess participants’ perceptions of decent work, we employed the 15-item Decent Work Scale (DWS, Duffy et al., 2017). This scale comprises five subscales: adequate compensation (3 items), access to adequate healthcare (3 items), safe working conditions (3 items), work hours allowing for sufficient rest and leisure (3 items), and organizational values congruent with familial and social values (3 items). Sample items include, “I feel emotionally safe interacting with people at work”, “I receive good healthcare benefits from my job”, “I am fairly compensated for my work”, “I have leisure time during the workweek”, and “My organization’s values resonate with my family values”. Items are on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”. Higher scores on this scale signified a greater degree of perception of decent work. DWS scores yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.924.

The UCSI University Ethics Committee approved the study. The teachers consented to the study on the Wenjuanxing (www.wjx.cn) in the WeChat workgroup. We assured the participants of the anonymity of the study responses.

Following these analyses, we employed AMOS 26.0 software to explore the relationships between various constructs and variables, thereby validating the theoretical model proposed in our study, including an examination of factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and other indicators to assess the construct validity of the measurement model. Moreover, we conducted various fit indices, including χ2/df (the ratio of the chi-square statistic to degrees of freedom), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI, SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual), and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) were considered to ensure the adequacy of the model’s fit to the data. These analyses were conducted to investigate the interrelationships between variables and verify our research hypotheses.

Descriptive statistics and measurement model. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the research variables and the results of the reliability and validity assessments conducted through CFA. The standardized factor loadings all exceeded 0.6, and all indicator factor loadings were significantly different from zero at the 0.001 level. Furthermore, AVE values were all greater than 0.5, demonstrating excellent convergent validity for each dimension of the measurement model (see Table 2).

Structural model. Model fit was employed to assess the degree of alignment between the theoretical model and actual data. In this process, a range of indicators was utilized to measure the adequacy of model fit. Firstly, χ2/df serves as a crucial indicator, where a value less than 5 signifies an acceptable level of model fit. Secondly, SRMR and RMSEA should fall within the range of 0 to 1, exhibiting an inverse relationship with model fit. Values less than 0.05 indicated a good fit, while a value of 0.08 suggested an acceptable level of fit. Moreover, various other indices such as GFI (Goodness of Fit Index), CFI, and TLI should exceed 0.9, indicating a positive association with the model fit.

In the study, χ2/df = 3.089, SRMR = 0.0463, RMSEA = 0.069, GFI = 0.931, IFI = 0.970, CFI = 0.970, and TLI = 0.962. According to the aforementioned criteria, the preliminary assessment suggested a substantial level of fit between the data and the model, indicating our ability to proceed with further empirical analysis.

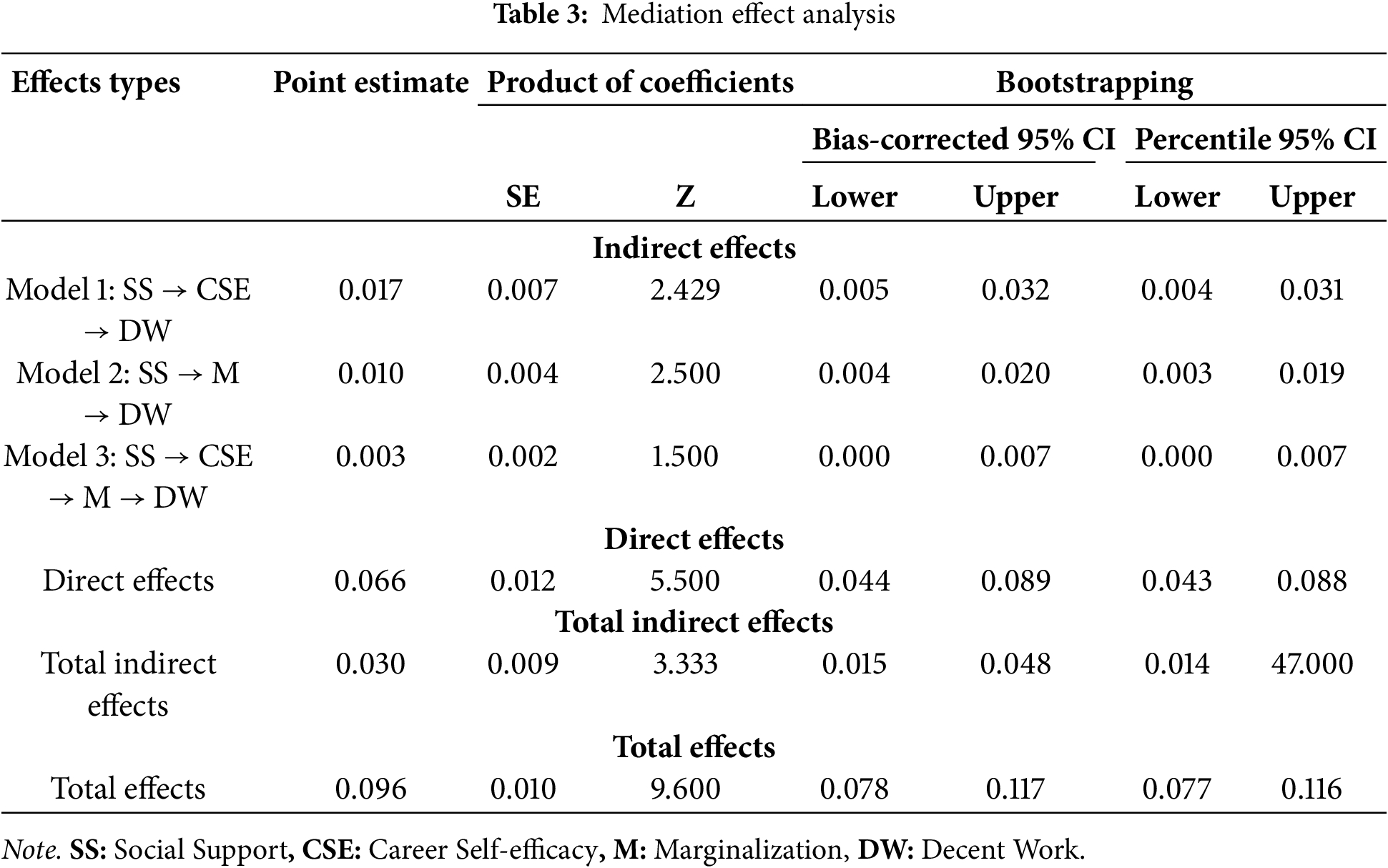

Social support and decent work with CSE. As in Table 3, social support predicted a higher sense of decent work (β = 0.329, Z = 5.716, p < 0.001), thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. Social support predicted CSE (β = 0.537, Z = 11.904, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2. Furthermore, higher CSE predicted decent work (β = 0.158, Z = 2.848, p < 0.05) in support of Hypothesis 2.

Marginalization mediation. Marginalization media-ted the relationship between social support and perceptions of decent work, such that lower levels of social support led to higher marginalization, which in turn was associated with lower perceptions of decent work (see Table 2) (β = −0.22, Z = −3.759, p < 0.001). Furthermore, marginalization predicted lower decent work (β = −0.23, Z = −4.692, p < 0.001). The indirect effect of social support through marginalization was a B = 0.010, with a 95% BC bootstrap confidence interval of [0.004, 0.020]. This lends support to Hypothesis 3.

CSE and marginalization sequential mediation. The relationship between social support and decent work was explained by the strong positive correlation between social support and CSE (β = 0.537, p < 0.001)and negative CSE and marginalization (β = −0.118, Z = −2.042, p < 0.05). Moreover, within the comprehensive model, marginalization is negatively correlated with decent work (β = −0.23, Z = −4.692, p < 0.001). The estimated value for the chained mediation effect is B = 0.003, with a 95% BC bootstrap resampling confidence interval of [0.000, 0.007]. This outcome lends support to Hypothesis 4. Table 3 presents three sets of comparisons: Model 1 vs. Model 2, Model 1 vs. Model 3, and Model 2 vs. Model 3. Model 1 vs. Model 2 showed no significant difference as the 95% BC bootstrap resampling confidence interval for the comparison includes zero. On the other hand, Model 2 and Model 3 exhibited a significant difference. This comparison revealed that the mediating effect of marginalization was greater than the chain mediation effect of CSE and marginalization. Furthermore, there was also a significant difference between Model 1 and Model 3. Among these three types of indirect effects, the indirect effect of CSE (Model 1) had the largest magnitude.

Social support was found to positively predict higher levels of decent work perceptions among rural primary school teachers. Strengthening individuals’ awareness of decent work is critical, as it contributes to enhanced job satisfaction and overall career well-being (Koekemoer & Masenge, 2023). The pivotal influencing factor of decent work, social support, should receive ample attention at both educational authority and school management levels. According to SCCT, enhancements can be implemented across various dimensions, such as improving material conditions, including income and working environment (Lent et al., 2002). Additionally, at the psychological level, school management should exhibit greater concern for teachers’ daily work situations.

The results indicated that CSE mediated the relationship between social support and perceptions of decent work among rural primary school teachers. This finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that higher levels of social support enhance individuals’ career self-efficacy, which in turn positively influences their work-related outcomes (Chan, 2020; Hou et al., 2019). Based on SCCT, environmental supports, such as social support, can strengthen individuals’ beliefs in their ability to successfully navigate career tasks, ultimately promoting more positive perceptions of their work environment (Lent & Brown, 2013). In the context of rural education, enhancing teachers’ CSE through supportive resources appears critical for fostering a stronger sense of decent work and improving their career satisfaction and stability.

The findings further revealed that marginalization mediated the relationship between social support and perceptions of decent work, such that lower levels of social support were associated with increased experiences of marginalization, which in turn diminished individuals’ perceptions of decent work. This result is aligned with prior research indicating that social and economic marginalization negatively impacts work-related outcomes, including access to decent work opportunities (Blustein et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2016). Within the framework of the PWT, marginalization is considered a key barrier that restricts individuals’ fulfillment of work needs and undermines their perceptions of career quality (Kim et al., 2021). For rural teachers, the lack of adequate social support may exacerbate their sense of marginalization, thus limiting their sense of empowerment and career satisfaction (Dong & Wang, 2023). These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions to reduce marginalization and foster more equitable and supportive work environments for teachers in under-resourced areas.

The results also demonstrated that CSE and marginalization jointly served as chained mediators between social support and perceptions of decent work. Specifically, greater social support enhanced individuals’ career self-efficacy, which subsequently reduced their experiences of marginalization, ultimately leading to stronger perceptions of decent work. This finding extends prior research suggesting that psychological resources and social barriers jointly shape work-related outcomes (Blustein et al., 2016; Duffy et al., 2016). Consistent with the frameworks of SCCT and the PWT, the results highlight that social support not only directly fosters career self-efficacy but also indirectly mitigates feelings of marginalization, both of which are critical pathways toward enhancing perceptions of decent work. These insights underscore the importance of holistic intervention strategies that simultaneously build psychological strengths and reduce structural barriers in supporting the career development of rural teachers.

From the perspective of PWT, previous academic inquiries seemed to have not delved deeply into exploring the direct impact of social support on individuals’ perception of decent work and its underlying mechanisms (Duffy et al., 2016). According to SCCT, social support was believed to positively influence individuals’ self-efficacy (Lent et al., 2002). Through the affirmation, encouragement, and assistance from others, individuals gained confidence in their abilities and potential within the professional domain (Reddan, 2015).

The mediating roles of career self-efficacy and marginalization in the relationship between social support and the perception of decent work could also be explained through SCCT. Individuals, by receiving recognition, support, and guidance from others, were more likely to believe in their ability to overcome professional challenges, enhancing their occupational confidence (Lent et al., 2000). In situations where individuals perceive themselves as competent and capable of achieving professional goals, a higher perception of decent work is likely to be obtained (Pajares, 2006).

As for the explanation of marginalization as a mediating variable, the decrease in self-efficacy may also impact marginalization. This may be due to individuals lacking sufficient external support over an extended period in society, leading to feelings of marginalization and causing doubts about their abilities (Lord & Hutchison, 1993). These doubts may influence their goal-setting and achievement in their careers. In this context, the introduction of SCCT becomes particularly crucial.

Grounded in the SCCT framework, this study employed empirical research methods to address gaps in previous research within this domain, providing a fresh theoretical perspective on understanding how individuals perceive decent work. This research offers additional theoretical insights for scholars working within the frameworks of SCCT and PWT.

This study holds significant practical implications, particularly within the realm of managing teachers in rural primary schools. Firstly, the research underscores the crucial importance of enhancing social support for teachers in rural primary schools in influencing their perception of decent work. Rural teachers serve as the cornerstone of successful rural education and play a pivotal role in driving rural revitalization (Peng et al., 2014).

Educational authorities can institute incentive and reward policies, including preferential treatment in professional title evaluations, raising the income levels of rural primary school teachers, and improving their daily living and working environments (Chapman & Adams, 2002). Creating a social environment that respects rural primary school teachers and alleviates their sense of marginalization can further enhance their perception of decent work.

In conclusion, this research offered valuable insights into education policies and practices at a practical level. Strengthening social support for decent work, enhancing teachers’ self-efficacy, and mitigating marginalization can contribute to improvements in education quality. It provided substantial guidance for education policymakers, school leaders, and government decision-makers, thereby supporting the development of a robust education system.

In summary, this study provided crucial revelations for both theoretical and practical domains, guiding enhancements in the career development of the education sector and offering valuable references for career development research and policy-making in other fields. This research not only enriched the theoretical framework but also positively influenced actual education policies and practices.

Limitations and directions for future research

The study had several limitations. Firstly, the data primarily originated from China and may not be generalizable to other settings. Secondly, the study employed a cross-sectional research design, and self-reporting by participants, which can be susceptible to recall biases, potentially impacting the accuracy of the data (Rindfleisch et al., 2008). To address these limitations, future research could consider using more longitudinal research designs to delve into causal relationships, as well as conduct more in-depth investigations into specific themes to enhance the credibility and transparency of the research.

The study found that social support is an important protective factor for decent work among rural primary school teachers. CSE mediated the relationship between social support and decent work. Marginalization mediated the relationship between social support and decent work. This chained mediation emphasized the pivotal role of CSE and marginalization in the occupational development process, highlighting how social support impacted decent work through multiple pathways. Therefore, education systems should help rural primary school teachers get a higher perception of decent work by improving social support, CSE, or declining marginalization to effectively enhance their perceptions of decent work.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jiajian Wang: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Validation; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Mansor Bin Abu Talib: Supervision. Biru Chang: Investigation; Writing—review & editing. Jingwen Zhang: Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research has been conducted by the ethical standards and guidelines established by the UCSI University Ethics Committee. The ethical approval number is DEC/PSY/2022/09/2023-05(15).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study. The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Alfa, A., Rouamba, B., Tchonda, M., Meda, M.w J., Leeming, C. S. et al. (2023). Decent work and entrepreneurial intentions in West Africa and Switzerland. Australian Journal of Career Development, 32(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/10384162231193221 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bandura, A. (2012). Cultivate self-efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In: Handbook of principles of organizational behavior: Indispensable knowledge for evidence-based management (pp. 179–200). Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119206422.ch10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bassi, M., Steca, P., Fave, A. D., & Caprara, G. V. (2007). Academic self-efficacy beliefs and quality of experience in learning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(3), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9069-y [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Blustein, D. L., Kenny, M. E., Di Fabio, A., & Guichard, J. (2019). Expanding the impact of the psychology of working: Engaging psychology in the struggle for decent work and human rights. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(1), 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072718774002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Blustein, D. L., Olle, C., Connors-Kellgren, A., & Diamonti, A. J. (2016). Decent work: A psychological perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00407 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Blustein, D. L., Perera, H. N., Diamonti, A. J., Gutowski, E., Meerkins, T. et al. (2020). The uncertain state of work in the U.S.: Profiles of decent work and precarious work. J Vocat Behav, 122(3), 103481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103481 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chan, C.-C. (2020). Social support, career beliefs, and career self-efficacy in determination of Taiwanese college athletes’ career development. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 26(6), 100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.100232 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chapman, D. W., & Adams, D. K. (2002). The quality of education: Dimensions and strategies. Asian Development Bank Hong Kong. [cited 27 May 2025]. Retrieved from: https://cerc.edu.hku.hk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Vol5_ChapAdams_bookletr4.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Domene, J. F. (2012). Calling and career outcome expectations: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711434413 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong, S., & Wang, J. (2023). The actual difficulties and relevant solutions of the marginalization of rural teachers. Contemporary Teacher Education, 16(20), 74–79. https://doi.org/10.16222/j.cnki.cte.2023.02.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., England, J. W., Blustein, D. L., Autin, K. L. et al. (2017). The development and initial validation of the Decent Work Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(2), 206. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000191 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Duffy, R. D., Blustein, D. L., Diemer, M. A., & Autin, K. L. (2016). The psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000140 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Duffy, R. D., Gensmer, N., Allan, B. A., Kim, H. J., Douglass, R. P. et al. (2019). Developing, validating, and testing improved measures within the Psychology of Working Theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112(2), 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.02.012 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Duffy, R. D., Kim, H. J., Allan, B. A., & Prieto, C. G. (2020). Predictors of decent work across time: Testing propositions from Psychology of Working Theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 123(4), 103507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103507 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Duffy, R. D., Prieto, C. G., Kim, H. J., Raque-Bogdan, T. L., & Duffy, N. O. (2021). Decent work and physical health: A multi-wave investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 127(1), 103544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103544 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fu, L., & Liu, A. (2022). China statistical yearbook 2022. Beijing, China: China Statistics Press. [cited 27 May 2025]. Retrieved from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=KaAwsYWd1tK8EGZWWAc1lXtilXN9J9uUYBKjbnTOGwOQZco6or83Zcg-cr72B5D8GUdM7zXYTAQLYfeXQhE3w8mZ1KnNVkgc27EqYxhQ_3gSm9XpnNE9Ws8zFPfeR2g3ucWSk-Gr4og=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS. [Google Scholar]

Hou, C., Wu, Y., & Liu, Z. (2019). Career decision-making self-efficacy mediates the effect of social support on career adaptability: A longitudinal study. Social Behavior and Personality, 47(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.8157 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ireland, G. W., & Lent, R. W. (2018). Career exploration and decision-making learning experiences: A test of the career self-management model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106(2), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.11.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kekana, E., Koekemoer, E., & O’Neil, S. (2022). Unpacking the concept of decent work in the psychology of working theory for blue-collar workers. Journal of Career Development, 50(2), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/08948453221086980 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim, H. J., Duffy, R. D., & Allan, B. A. (2021). Profiles of decent work: General trends and group differences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000434 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Koekemoer, E., & Masenge, A. (2023). Outcomes of decent work among blue-collar workers in South Africa: The role of job satisfaction. Journal of Career Assessment, 32(2), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727231187639 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kozan, S., Işık, E., & Blustein, D. L. (2019). Decent work and well-being among low-income Turkish employees: Testing the psychology of working theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(3), 317. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000342 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. (2002). Career development from a social cognitive perspective. In: D. Brown, l. brooks, & associates (Eds.Career choice and development (4th ed.) (pp. 255–311). San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 557. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033446 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual supports and barriers to career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2002). Social cognitive career theory. Career Choice and Development, 4(1), 255–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. W., Morris, T. R., Penn, L. T., & Ireland, G. W. (2019). Social-cognitive predictors of career exploration and decision-making: Longitudinal test of the career self-management model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000307 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. W., Morris, T. R., Wang, R. J., Moturu, B. P., Cygrymus, E. R. et al. (2022). Test of a social cognitive model of proactive career behavior. Journal of Career Assessment, 30(4), 756–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727221080948 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, X. (2010). A study on the correlation between social support and mental health of Chinese people [master’s thesis]. Chongqing, China: Southwestern University. [Google Scholar]

Lord, J., & Hutchison, P. (1993). The process of empowerment: Implications for theory and practice. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 12(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar]

Ma, Y., You, J., & Tang, Y. (2019). Examining predictors and outcomes of decent work perception with chinese nursing college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 17(1), 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010254 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

McIlveen, P., Hoare, P. N., Perera, H. N., Kossen, C., Mason, L. et al. (2021). Decent work’s association with job satisfaction, work engagement, and withdrawal intentions in Australian working adults. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720922959 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Orakci, S., Yuregilli Goksu, D., & Karagoz, S. (2022). A mixed methods study of the teachers’ self-efficacy views and their ability to improve self-efficacy beliefs during teaching. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1035829. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1035829 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pajares, F. (2006). Self-efficacy during childhood and adolescence. In: Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (pp. 339–367). [Google Scholar]

Peng, W. J., McNess, E., Thomas, S., Wu, X. R., Zhang, C. et al. (2014). Emerging perceptions of teacher quality and teacher development in China. International Journal of Educational Development, 34(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2013.04.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Perera, H. N., Maghsoudlou, A., Miller, C. J., McIlveen, P., Barber, D. et al. (2022). Relations of science teaching self-efficacy with instructional practices, student achievement and support, and teacher job satisfaction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 69(5), 102041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.102041 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Reddan, G. (2015). Enhancing students’ self-efficacy in making positive career decisions. Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education, 16(4), 291–300. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1113595. [Google Scholar]

Rindfleisch, A., Malter, A. J., Ganesan, S., & Moorman, C. (2008). Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(3), 261–279. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.45.3.261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rivera, L. M., Chen, E. C., Flores, L. Y., Blumberg, F., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2007). The effects of perceived barriers, role models, and acculturation on the career self-efficacy and career consideration of Hispanic women. The Career Development Quarterly, 56(1), 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2007.tb00019.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sargent, T., & Hannum, E. (2005). Keeping teachers happy: Job satisfaction among primary school teachers in rural northwest China. Comparative Education Review, 49(2), 173–204. https://doi.org/10.1086/428100 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Taylor, S. E. (2011). Social support: A review. In: The Oxford handbook of health psychology (pp. 189–214). [Google Scholar]

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Y. (2023). The change of influencing factors of rural teachers’ turnover intention: The comparison before and after the implementation of the rural teachers support plan of yunnan province (2015—2020). Journal of East China Normal University (Education Science), 41(9), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.16382/j.cnki.1000-5560.2023.09.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, J., & Chang, B. (2025). More marginalization, less career development? Linking marginalization profiles to decent work among rural teachers. Acta Psychologica, 252(2), 104668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104668 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, D., Jia, Y., Hou, Z. -J., Xu, H., Zhang, H. et al. (2019). A test of psychology of working theory among Chinese urban workers: Examining predictors and outcomes of decent work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115(6), 103325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103325 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wei, W., & Duffy, R. D. (2022). Decent work and turnover intention among new generation employees: The mediating role of job satisfaction and the moderating role of job autonomy. SAGE Open, 12(2), 21582440221. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221094591 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Williams, T. R., Autin, K. L., Pugh, J., Herdt, M. E., Garcia, R. G. et al. (2023). Predicting decent work among US black workers: Examining psychology of working theory. Journal of Career Assessment, 31(4), 756–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727221149456 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, Z., & Qin, Y. (2023). Report of Rural Education Development in China. Beijing, China: Science Press. [Google Scholar]

Xu, Y., Liu, D., & Tang, D. S. (2022). Decent work and innovative work behaviour: Mediating roles of work engagement, intrinsic motivation and job self-efficacy. Creativity and Innovation Management, 31(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12480 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, H., & Huang, H. (2018). Decision-making self-efficacy mediates the peer support-career exploration relationship. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 46(3), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6410 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhou, Y. (2020). “Leaving” or “Staying”: The intention to resign of young teachers in rural primary schools. Journal of Educational Science of Hunan Normal University, 19(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.19503/j.cnki.1671-6124.2020.02.012 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools