Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evaluating Industry 4.0 readiness: A quantitative analysis of human and technological factors in the Russian context

1 School of Management and Economics, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China

2 Center for West African Studies, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China (UESTC), Chengdu, 611731, China

3 Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Kumasi, P.O. Box 1277, Ghana

4 School of Economics and Management, Southwest University of Science and Technology, Mianyang, 621010, China

* Corresponding Author: Addo Prince Clement. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 287-298. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.067165

Received 26 May 2024; Accepted 04 April 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the influence of human capital development and technological, strategic, cognitive, and environmental factors on Industry 4.0 readiness, as well as cultural factors acting as a mediator. Respondents were 478 employees from across eight regions in Russia. Survey data were collected on employee technological readiness, human capital development, strategic planning, cognitive perceptions, and environmental and cultural factors influencing the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies, with cultural factors mediating. These findings from the structure equation analysis show that technological factors and human capital development are the strongest predictors of readiness, suggesting that robust digital infrastructure and a skilled workforce are critical for Industry 4.0 adoption. These findings contribute specifically to the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) by expanding its application to the context of Industry 4.0 adoption. Furthermore, the findings provide practical insights for policymakers and industry leaders, empowering them to enhance technological implementation strategies by identifying areas such as human resource development to improve implementation strategies for Industry 4.0.Keywords

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, or Industry 4.0, has revolutionized global manufacturing by integrating IoT, AI, robotics, and big data analytics (Gunal, 2019; Jideani et al., 2020; Telang, 2019). This transformation can significantly boost productivity, flexibility, and sustainability (Purwanto, 2024; Saudi et al., 2019; Venkateshalu, 2023). Presently, the evidence is less established on the influence of human capital development and technological, strategic, cognitive, and environmental factors on Industry 4.0 readiness, taking into account cultural factors. This is despite the fact that findings would be necessary for a coherent policy framework for guiding technological infrastructure and workforce readiness initiatives. This study aimed to explore how cultural factors mediate human capital and how technological, strategic, cognitive, and environmental factors collectively shape Industry 4.0 readiness. It focuses on Russia’s adaptation of Industry 4.0 as a case study.

Adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies and value chains

Recent research highlights the relationship between Industry 4.0 technologies and the participation of Russian manufacturing firms in global and domestic value chains (GVCs and DVCs). For instance, companies in DVCs demonstrate broader utilization of Industry 4.0 technologies across various application areas, indicating that Industry 4.0 adoption encourages firms to establish enduring relationships with domestic suppliers (Fedyunina et al., 2024). Regardless, a significant barrier to widespread Industry 4.0 adoption is the lack of understanding of the value and potential of these technologies among industrial stakeholders (Tortorella & Fettermann, 2018). Additionally, the complexity of integrating advanced technologies into existing systems and the need for substantial investments in digital infrastructure pose considerable hurdles (Dalenogare et al., 2018).

The transition to Industry 4.0 also has profound implications for labor markets and social structures. Automating tasks traditionally performed by humans is expected to lead to significant job displacement, raising ethical and legal concerns. For example, the relocation of production facilities by companies like Nike and Adidas from Southeast Asia to more technologically advanced regions further illustrate the disruptive impact of Industry 4.0 on global labor markets (Frank et al., 2019).

Theoretical foundations. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) framework categorizes the challenges industries into three key areas: (1) human capital issues, (2) technological infrastructure deficits, and (3) cultural factors. To develop and scale policies and frameworks that maximize the benefits of AI and IoT requires the fostering collaboration between businesses, policymakers, and civil society to co-design innovative approaches to technology governance (World Economic Forum, 2021). Moreover, enhancing digital literacy and workforce skills is critical for thriving digital economies (Kumar & Korovin, 2022).

The Russian Industry 4.0 Context

Given its strengths in software development, mathematics, and intelligent algorithms, Russia has significant potential to become a leader in Industry 4.0. Russian specialists have consistently been at the forefront of these fields, supported by strong educational and scientific institutions (Frank et al., 2019). Moreover, Russia’s abundant natural and mineral resources provide a solid foundation for developing new productive forces essential for Industry 4.0 (Kagermann et al., 2013).

Russia’s recent partnership with the World Economic Forum’s Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution Network highlights the nation’s aspiration to accelerate Industry 4.0 adoption by focusing on AI, IoT, and other pilot projects (World Economic Forum, 2021). While these efforts are promising, adoption across sectors and regions has been inconsistent. This study will explore the systemic challenges hindering Industry 4.0 adoption in Russia and identify areas where strategic intervention is most needed.

In summary, technological readiness, infrastructure, and capabilities are fundamental for adopting and implementing Industry 4.0 technologies. These factors directly affect the feasibility and execution of digital transformation initiatives (Oesterreich & Teuteberg, 2017). Advanced technology availability, digital infrastructure, cybersecurity measures, and IoT integration are critical elements that drive technological innovation. The workforce’s skills, training, and education are crucial for leveraging Industry 4.0 technologies. Human capital development ensures employees have the necessary competencies to use and manage new technologies effectively (Davis, 1985; Davis et al., 1989). Key elements include training programs, educational initiatives, skill levels, and continuous professional development. Organizational strategies, resource allocation, and planning are vital for aligning technology adoption with business objectives. Strategic factors, including strategic planning, resource allocation, leadership commitment, and organizational policies, determine how well-prepared an organization is to integrate and sustain Industry 4.0 technologies (Arnold et al., 2016). Perceptions and attitudes towards new technologies influence their acceptance and usage. Cognitive factors are important for understanding how individuals within an organization view and interact with Industry 4.0 technologies (Venkatesh et al., 2023). Elements such as perceived ease of use, usefulness, technology acceptance, and user attitudes are crucial.

External influences such as market dynamics, competition, government policies, and regulatory frameworks play a significant role in shaping the readiness and adoption of Industry 4.0. These factors provide the broader context within organizations’ operations (Machado et al., 2019). The key components are market demand, competitive pressures, regulatory support, and industry standards. Cultural factors encompass an organization’s values, beliefs, and practices that influence how technologies are adopted and implemented. These factors mediate the relationships between various determinants and Industry 4.0 readiness, providing deeper insights into the internal dynamics that facilitate or hinder technology adoption.

Goals of the study: The current study examines the human and technological factors affecting industrial readiness (IR) for I4.0, identify hindrances to its implementation, and advance workable solutions to promote industrial readiness for Industry 4.0.

Hypothesis 1: Technological Factors (TF) are significantly related to Industry 4.0 Readiness (I4R) readiness.

Hypothesis 2: Human Capital Development (HCD) is significantly related to Industry 4.0 Readiness (I4R).

Hypothesis 3: Strategic Factors (SF) are significantly related to Industry 4.0 Readiness (I4R).

Hypothesis 4: Cognitive Factors (CF) are significantly related to Industry 4.0 Readiness (I4R).

Hypothesis 5: Environmental Factors (EF) are significantly related to Industry 4.0 Readiness (I4R).

Hypothesis 6: Cultural Factors mediate the relationship between Human Capital Development (HCD), Technological Factors (TF), Strategic Factors (SF), Cognitive Factors (CF), Environmental Factors (EF), and Industry 4.0 Readiness (I4R). The summary of the hypotheses is indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Hypothetical model for Industry 4.0 readiness

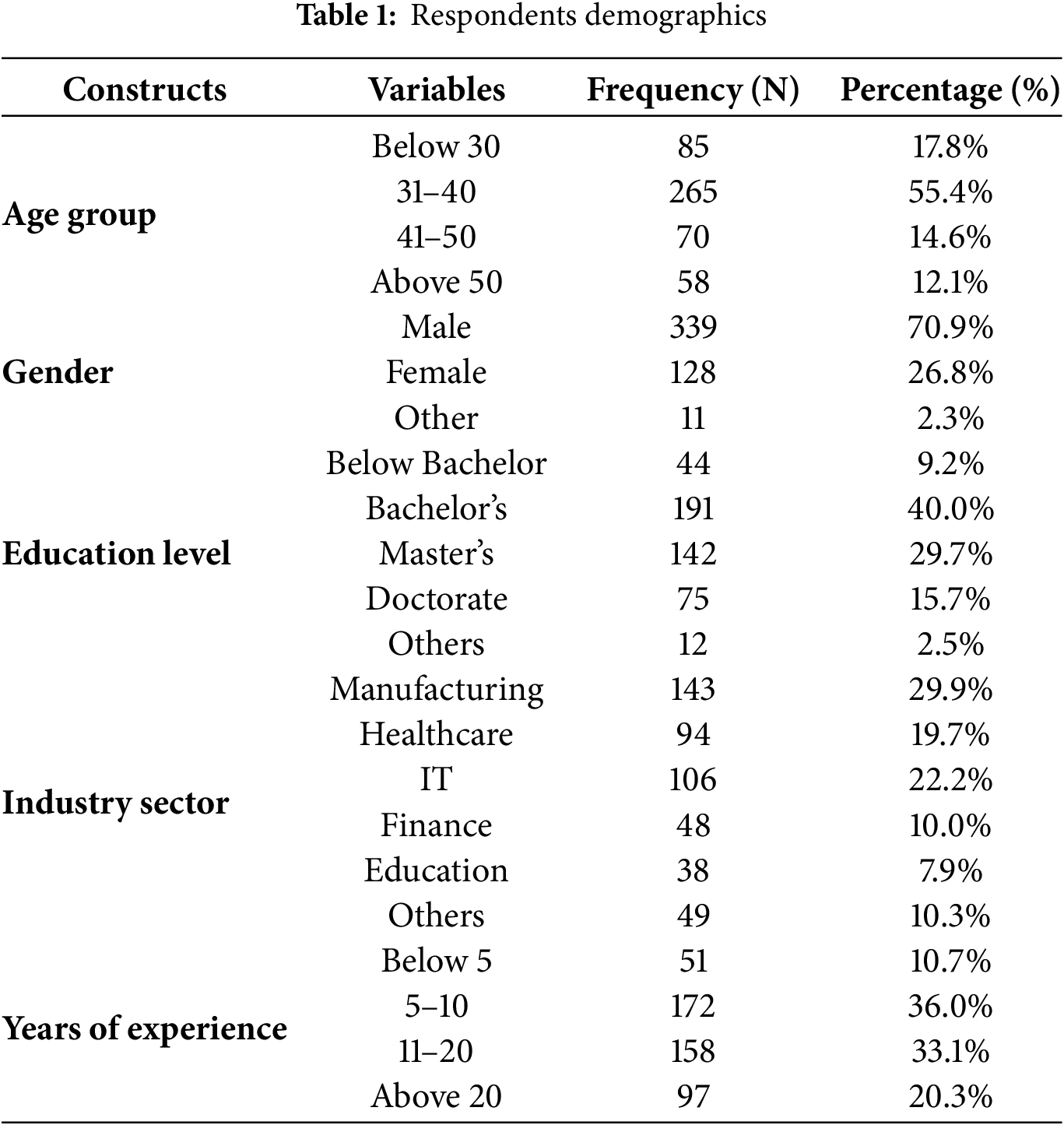

This study sampled 647 respondents across 8 main industrial sectors and 2 district and administrative regions of Moscow (see Table 1). The sample demographics comprised 70.9% males, 26.8% females, and 2.3% identified as others.

The age distribution of respondents shows that a majority, 55.4%, falls within the 31–40 age group, followed by 17.8% below 30, 14.6% between 41 and 50, and 12.1% above 50. This indicates a predominantly young to middle-aged demographic involved in the study, reflecting a workforce likely adaptable and open to new technology. Regarding education, 40.0% of the respondents hold a Bachelor’s degree, 29.7% have a Master’s degree, 15.7% hold a Doctorate, 9.2% have an education level below a Bachelor’s degree, and 2.5% fall into the ‘Others’ category. A stratified sampling approach was adopted, placing the industries into 3 strata: Small (<50 employees), Medium (50–250 employees), and Large (>250 employees). The industry sectors represented in the survey include Manufacturing (29.9%), IT (22.2%), Healthcare (19.7%), Finance (10.0%), Education (7.9%), and Others (10.3%). This diverse sector representation ensures a comprehensive understanding of Industry 4.0 readiness across different fields. Regarding work experience, 36.0% of the respondents have 5–10 years of experience, 33.1% have 11–20 years, 20.3% have more than 20 years, and 10.7% have less than 5 years of experience. This distribution suggests that most respondents are experienced professionals, which is critical for providing informed insights into Industry 4.0 readiness. They may also resist change since they may be used to and comfortable with the status quo.

The Human Resource Management and Practice Survey (HRMPS, Aycan et al., 2000). The HRMPS comprised 18 items to measure human capacity development components of training programs (5 items), educational initiatives (4 items), skills levels (5 items), and continuous professional development (4 items). Each items are measured over a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The reliability of HRMPS scores in the present study using Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89, indicating a high internal consistency and reliability of the instrument for measuring human capital development within the context of Industry 4.0 readiness.

Assistive Technology Questionnaire Using Factor Analyses (ATQUFA, Seok & Dacosta, 2014) was used to measure technological factors relevant to Industry 4.0 readiness. The ATQUFA consists of 20 items on digital infrastructure (5 items), advanced technology (5 items), availability (4 items), cybersecurity (4 items), and IoT integration (3 items) (e.g.,“Our company has adequate digital infrastructure to support Industry 4.0 technologies”, “We regularly update our technological systems to keep pace with Industry 4.0 advancements”). The items are measured over a 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). The reliability of ATQUFA scores in the present study was 0.94 indicating excellent internal consistency and robustness for measuring technological readiness components.

Strategic digital transformation scale (SDTS)

The Strategic Digital Transformation Scale (SDTS; Chiarini et al., 2020) was used to measure strategic factors relevant to Industry 4.0 readiness. The SDTS consists of 13 items across three dimensions: strategic planning (5 items), resource allocation (4 items) and leadership commitment (4 items). Example items include “Our leadership has a clear strategy for adopting Industry 4.0 technologies” and “Resources are allocated effectively to support our digital transformation initiatives.” This items are measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The reliability of SDTS scores in the present study was 0.89, showing a strong internal consistency and reliability of evaluating strategic factors in the context of Industry 4.0 readiness.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy skills questionnaire (CBTSQ)

Cognitive factors (e.g., technology acceptance, perceived usefulness) were evaluated using a modified Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Skills Questionnaire (CBTSQ; Jacob et al., 2011). The CBTSQ consists of 12 items, covering dimensions such as technology acceptance (4 items), perceived usefulness (4 items), and confidence in technology use (4 items). Example items include “I believe that using new digital technologies will enhance my job performance” and “I feel confident in my ability to learn and adapt to new Industry 4.0 technologies.” The items are measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The reliability of CBTSQ scores in the present study, as assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.87, indicating strong internal consistency and reliability for measuring cognitive factors in the context of Industry 4.0 readiness.

ALPHA questionnaire (Spittaels et al., 2010)

Environmental Factors, such as regulatory support and competitive pressures, were assessed using items from the ALPHA questionnaire (Spittaels et al., 2010). The ALPHA questionnaire consists of 12 items, divided into government regulations (4 items), market competition (4 items), and stakeholder expectations (4 items). Example items include “Regulatory frameworks support the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in our industry” and “Market competition drives our organization to adopt new technologies.” The items are measured on a 7-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree. The reliability of ALPHA questionnaire scores in the present study was 0.88, indicating strong internal consistency and reliability for measuring environmental factors relevant to Industry 4.0 readiness.

Readiness to change questionnaire (Heather et al., 1993)

In measuring the dependent variable Industry 4.0 readiness, the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (Heather et al., 1993) was modified to include items specifically connected to Industry 4.0 adoption. The modified questionnaire consists of 10 items, with a focus on operational readiness (4 items), technological readiness (3 items), and strategic readiness (3 items). Example items include “Our organization is well-prepared to implement Industry 4.0 technologies” and “We have established processes in place to support the transition to Industry 4.0.”

In addition, cultural factors related to readiness were assessed with items such as “Our organizational culture encourages innovation and experimentation with new technologies” and “Employees in our organization are open to changing their work processes to integrate new technologies.” The items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree. The reliability of the modified Readiness to Change Questionnaire scores in this study was 0.94, indicating excellent internal consistency and reliability for measuring Industry 4.0 readiness and cultural factors.

The industry sector and company size Small (<50 employees), Medium (50–250 employees), and Large (>250 employees) were the control variables used in this study. Biographical data was measured with self-developed items. All items with over 50% of the same mid-point response were eliminated to improve the validity of the items collected. Items from respondents who failed the attention-related questions and items with more than 10% missing data were not included. All other validity concerns, such as construct, convergent, and discriminant validity, are handled at different stages of the study to ensure that the final data used is valid and reliable.

The Ethics committee of the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China approved the study. The industry collaborating companies granted study permission. Participant employees consented to the study. All participants provided informed consent before participating, and the purpose of the study, along with assurances of data confidentiality, was clearly explained at the beginning of the survey. Respondents had the option to withdraw from the study at any point without any repercussions.

The surveys were administered online to ensure broader accessibility and flexibility for participants. A survey link was distributed via email and workplace social platforms through union leaders to the selected employees, and participants were asked to complete the survey at their convenience. All responses were anonymized to maintain confidentiality.

The SPSS AMOS (version 22) used to analyze the data First Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to model the relationships between multiple predictors and outcome variables, construct unobserved latent variables, account for measurement errors in observed variables, and to assess hypotheses based on a robust quantitative framework (Chin, 1998). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the constructs, employing fit indices such as Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Residual (RMR), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The model demonstrated a good fit with CFI > 0.90 and RMSEA < 0.08, confirming the validity of the measurement model.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to evaluate the discriminant validity and reliability of the constructs. To assess the model fit, three fit indices were employed: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Residual (RMR), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). According to Harrington (2009) and Brown (2015), a CFI value of 0.9 or higher, combined with RMR and RMSEA values of 0.1 or less, indicates a good fit.

The CMIN/DF (chi-square statistics to degrees of freedom) value was 2.809, within the acceptable range, providing strong model support (Hair et al., 2014). The CFI was 0.937, exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.90 (Hair et al., 2014). The RMSEA was 0.069, slightly above the recommended level of 0.05 but below the upper limit of 0.08 (Hair et al., 2014). These results confirm that the measurement model is fit (CMIN/DF = 2.351, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.937, RMR = 0.069, RMSEA = 0.069).

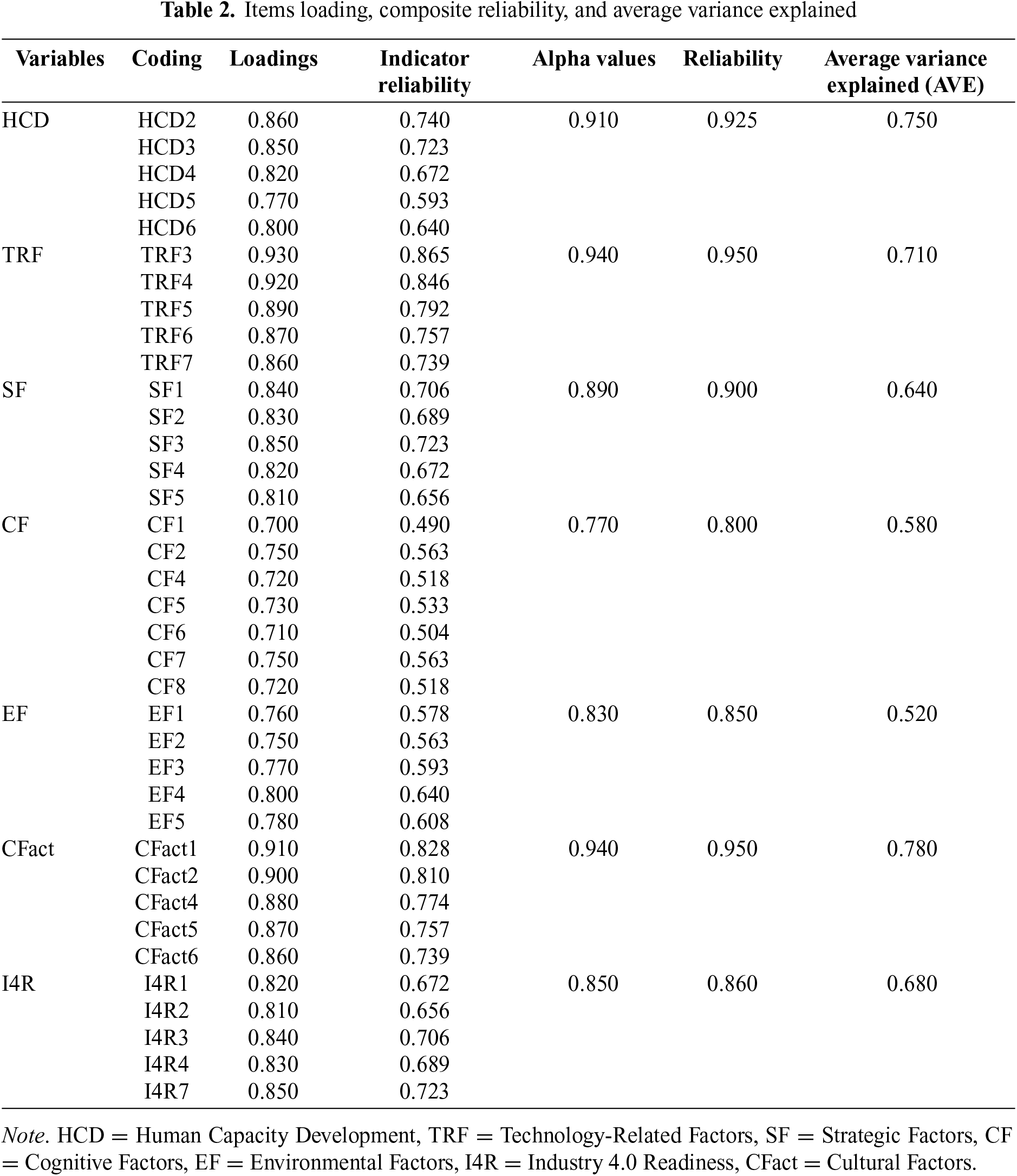

Following Hair et al. (2014), the measurement model was assessed for convergent and discriminant validity as follows:

Convergent Validity: Convergent validity (CV) evaluates the extent to which multiple items consistently measure a single construct. As recommended by Urbach and Ahlemann (2010) and Hair et al. (2014), CV was assessed using factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE).

The recommended values are AVE greater than 0.5 and CR greater than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2014). Additionally, CR values must exceed the corresponding AVE values to satisfy CV criteria. Table 2 and Figure 2 show that the measurement model results surpass these recommended values, indicating strong convergent validity (Hair et al., 2014).

Figure 2: Confirmatory factor analysis for I4R constructs

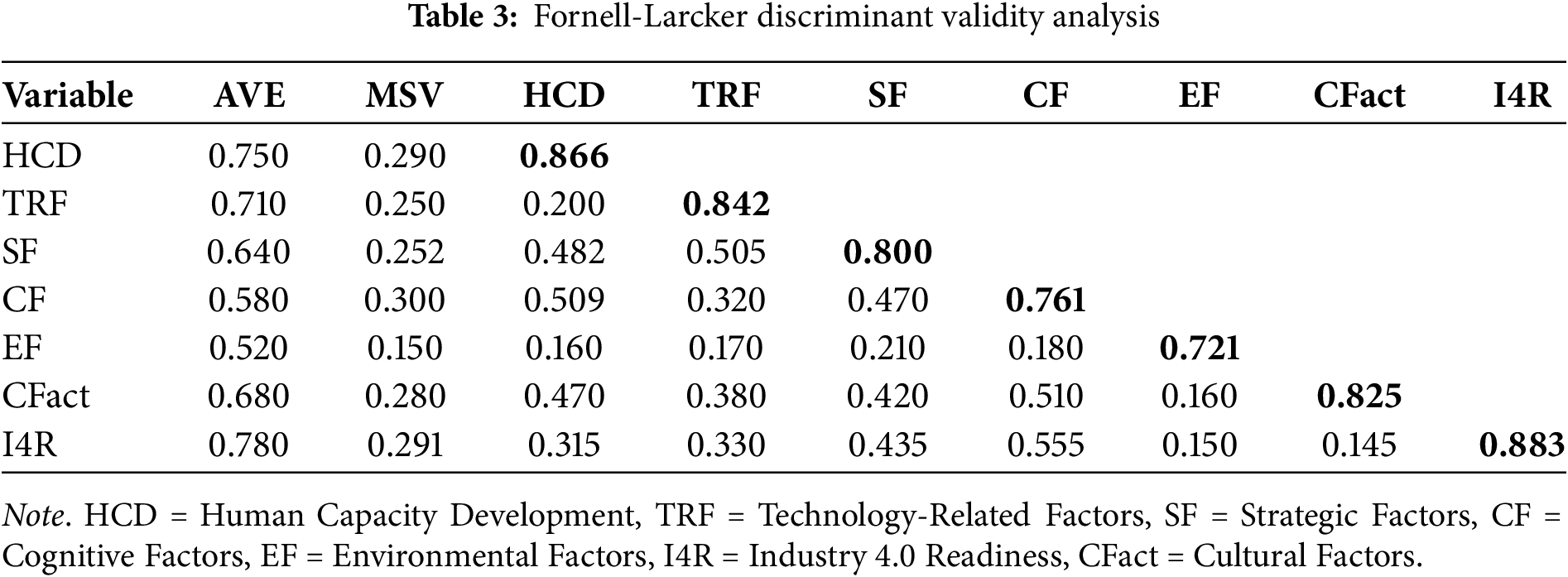

Discriminant Validity: Discriminant validity evaluates the degree to which constructs measure distinct concepts, analyzed through the Fornell and Larcker (1981) technique. The criterion involves comparing the AVE square root to the correlations among constructs. As shown in Table 3, the square root of the AVE values (displayed diagonally) exceed the correlations in their respective columns and rows, confirming sufficient discriminant validity.

The structural model’s predictive strength was assessed using R-square (R2) values, showing the independent variables’ variation (Barclay & Smith, 1995). Chin (1998) suggested that R2 values of 0.67, 0.33, and 0.19 indicate significant, moderate, and low explanatory strength, respectively. The R2 values for the dependent variables were found to be 0.37 and 0.33, indicating moderate explanatory strength. To ensure robustness, key assumptions were checked before the SEM analysis. Normality was verified using skewness and kurtosis values within the acceptable range of ±2. Multicollinearity was assessed using Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs), all below 5, indicating no multicollinearity issues (Hair et al., 2010). These checks confirm the data’s suitability for SEM. T-tests and path coefficients were used to determine relationships among the variables using 5000 bootstrapping samples.

The Structural Equation Model (SEM) demonstrates a good fit with the data, indicated by a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.937, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) of 0.912, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.069. These indices confirm the model’s reliability and suitability for analyzing Industry 4.0 readiness (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Technological Factors (H1) and Human Capital Development (H2) were the strongest predictors of Industry 4.0 readiness, with path coefficients of β = 0.390 and β = 0.450 (both p < 0.001).

The industrial readiness for adopting Industry 4.0 was measured using the readiness index, including 15 enabling technologies identified by Pacchini et al. (2019). These technologies encompass Autonomous robots, Simulation, Cloud computing, Horizontal and vertical integration, Cybersecurity, Additive manufacturing, Autonomous and self-driving vehicles, Machine to Machine communication, Smart factories, Intelligent materials, Mobile and edge computing, RFID, Artificial intelligence, and Cyber-physical systems. The survey results indicate that while some industries have begun to develop digital infrastructure, 82.92% do not have such infrastructure. Furthermore, only 5.68% of industries use Autonomous robots, and 4.50% utilize Simulation in their organizational processes. Vertical/horizontal integration is almost nonexistent, with 95.47% of industries not engaging in this practice. Only 4% of the surveyed industries have also implemented data protection measures.

The adoption of other critical technologies such as Cloud computing (2%), RFID (3%), Artificial intelligence (1.38%), and Intelligent materials (2.43%) is also very low. The Smart factory concept is adopted by 2.78% of industries, Autonomous vehicles by 3.13%, and M2M communication by 8.36%. These statistics suggest that the average industry has knowledge of only 9.22% of the technologies that enable I4.0, indicating a nascent stage of readiness.

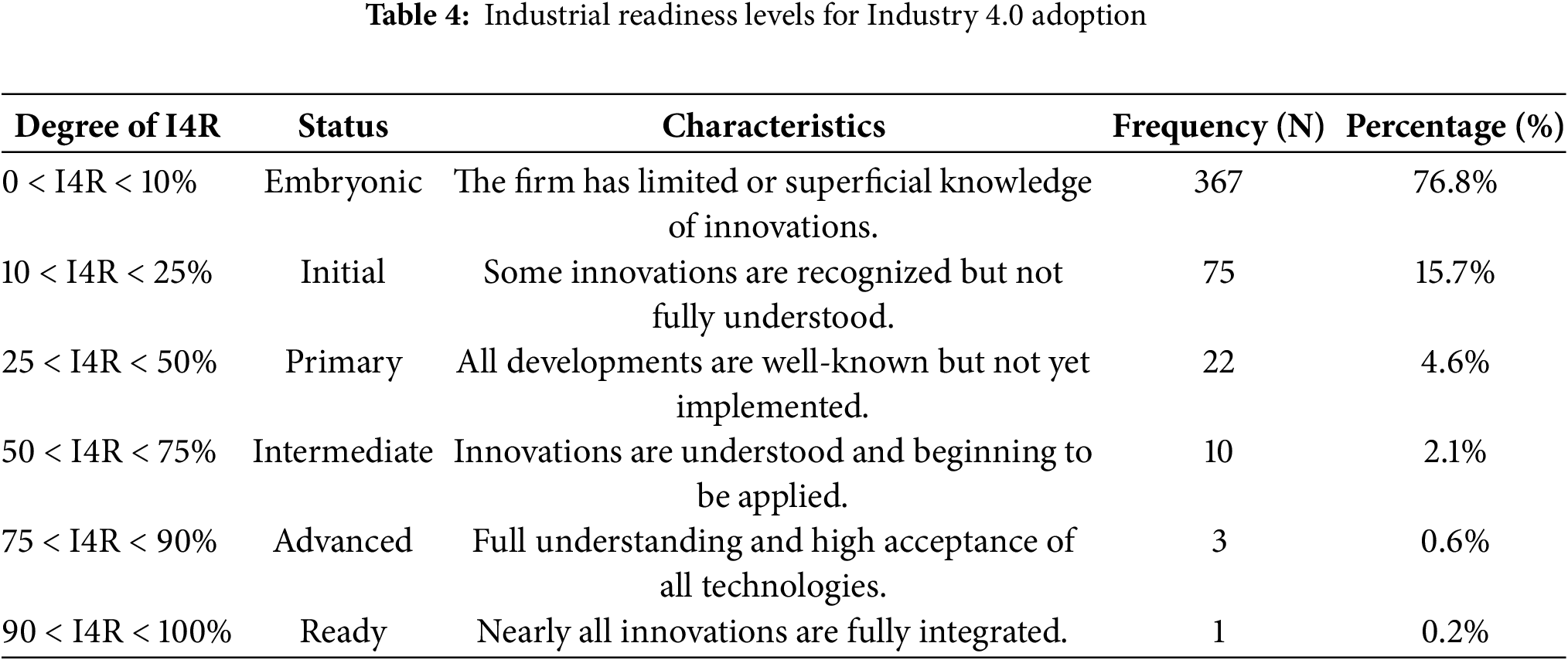

Most firms (76.8%) are embryonic, possessing only limited or superficial knowledge of innovations. About 15.7% are at the initial stage, recognizing some innovations but not fully understanding them.

A smaller segment, 4.6%, is in the primary stage, where all developments are known but not yet implemented. In the intermediate stage, representing 2.1% of firms, innovations are understood and starting to be applied. Advanced readiness is seen in 0.6% of firms with a full understanding and high acceptance of all technologies. Finally, only 0.2% of firms, mostly from the automotive industry, are ready for Industry 4.0, with nearly all innovations fully integrated. This distribution highlights a significant gap in technological adoption, with most firms at the early stages of readiness and few demonstrating comprehensive integration of Industry 4.0 technologies shown in Table 4. The overall conclusion is that industries in our study area are unfamiliar with Industry 4.0’s enabling technologies. They are in the early stages of readiness and require comprehensive policy measures to increase awareness and knowledge about these technologies before moving toward full-scale implementation.

Structural path model and hypotheses testing

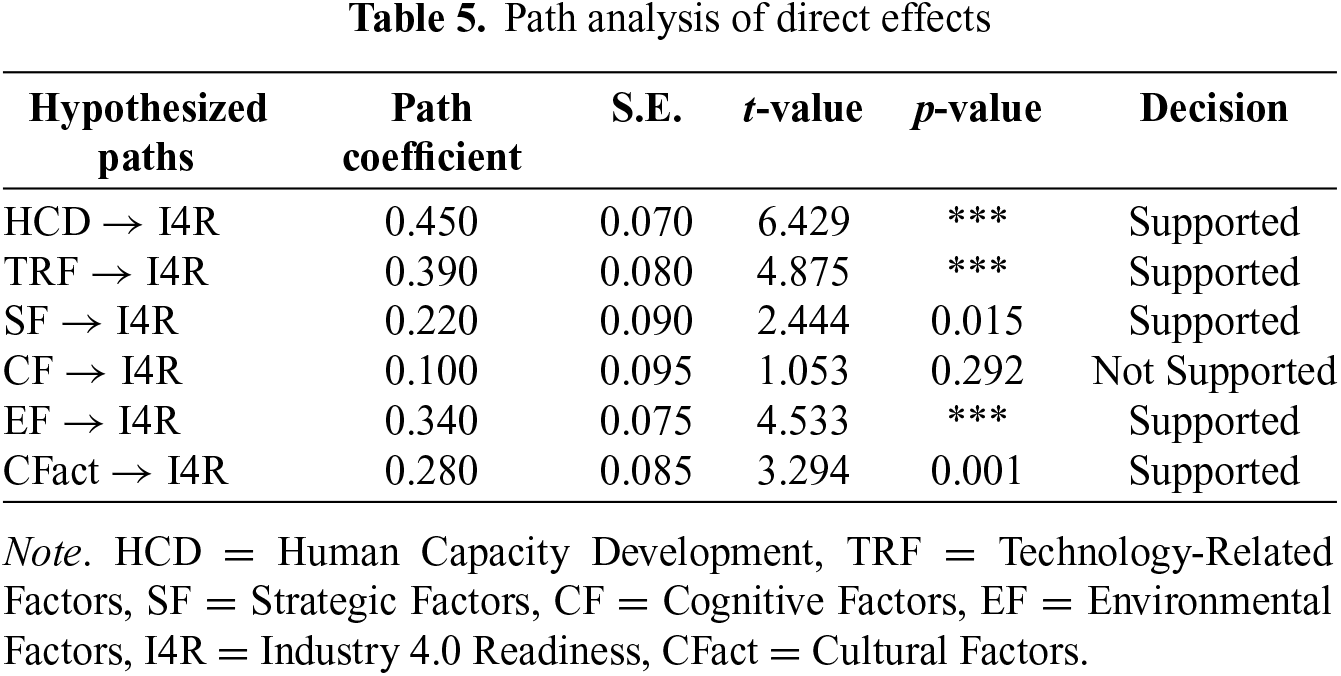

Table 5 illustrates the results of the structural path model, revealing significant effects of Human Capacity Development (HCD) (β = 0.450, t-value = 6.429, p < 0.001), Technology-Related Factors (TRF) (β = 0.390, t-value = 4.875, p < 0.001), Strategic.

Factors (SF) (β = 0.220, t-value = 2.444, p = 0.015), Environmental Factors (EF) (β = 0.340, t-value = 4.533, p < 0.001), and Cultural Factors (CFact) (β = 0.280, t-value = 3.294, p = 0.001) on Industry 4.0 Readiness (I4R). However, Cognitive Factors (CF) did not have a significant direct effect (β = 0.100, t-value = 1.053, p = 0.292).

A 5000-sample bootstrapped method was employed to assess the indirect effects of independent variables on the dependent variable (I4R) via the mediator (Cultural Factors), using a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval with 1000 replications.

Table 6 details the mediation analysis results, revealing significant indirect effects of HCD (β = 0.060, t-value = 2.300, p = 0.021), TRF (β = 0.050, t-value = 1.900, p = 0.048), and EF (β = 0.070, t-value = 2.400, p = 0.016) on I4R through Cultural Factors (CFact).

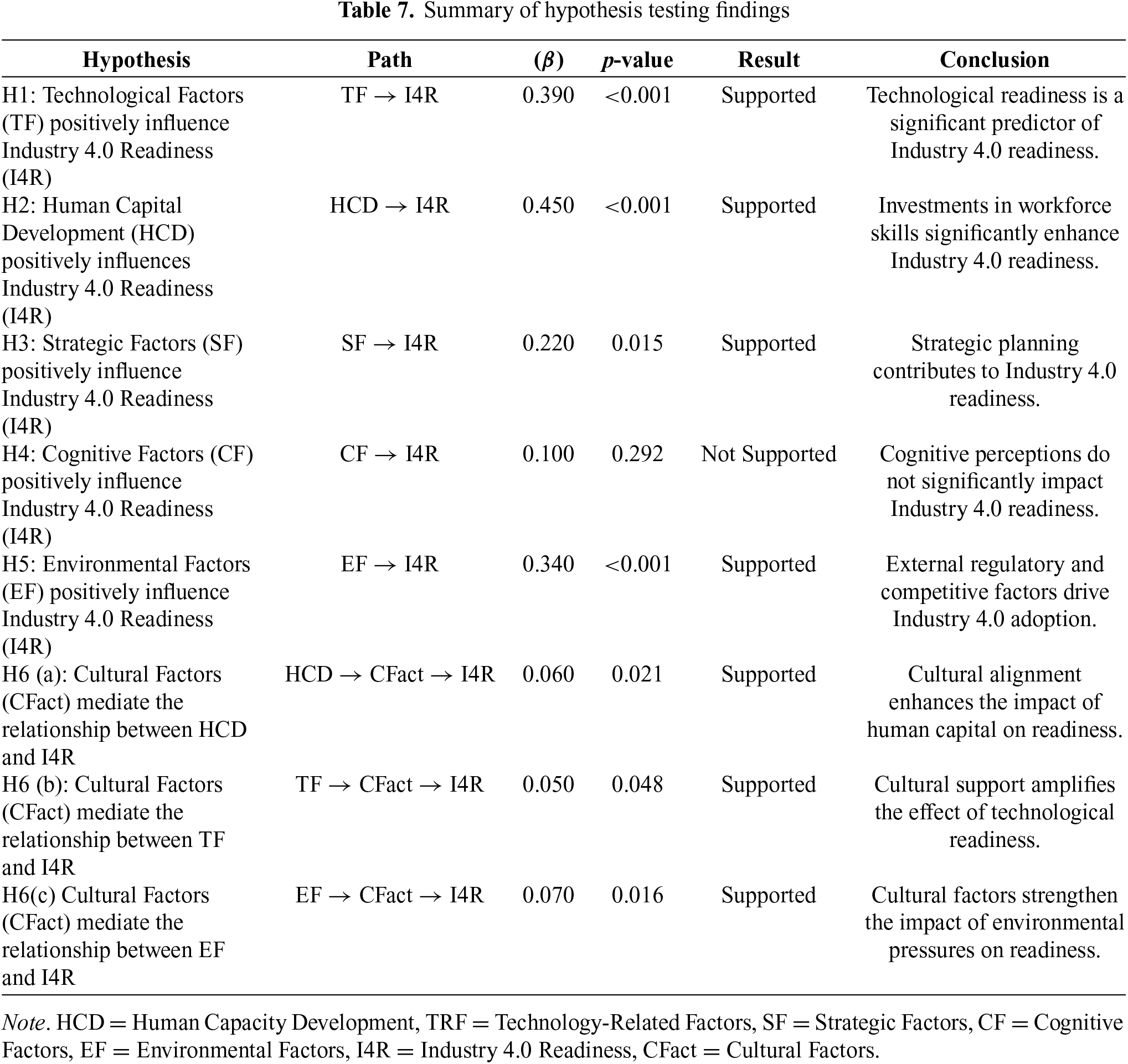

The results show that CFact significantly mediates the relationships for Human Capacity Development (HCD), Technology-Related Factors (TRF), and Environmental Factors (EF), but not for Strategic Factors (SF) or Cognitive Factors (CF). These findings align with prior literature emphasizing the critical role of cultural alignment in technology adoption (Hofstede, 1980; Tung, 2008). HCD → CFact → I4R: With a path coefficient of 0.060 (p = 0.021), this pathway indicates that cultural alignment significantly enhances the impact of workforce development on Industry 4.0 readiness. This finding supports Hofstede’s (1980) assertion that cultural values shape organizational outcomes, suggesting that Russian firms can strengthen human capital investments by fostering a culture open to digital transformation. TRF → CFact → I4R: The significant mediation effect (0.050, p = 0.048) implies that cultural openness can amplify the influence of technological infrastructure on readiness. This aligns with Tung’s (2008) argument that culturally adaptive organizations are more likely to succeed in technology integration, indicating that Russian industries with supportive cultural environments are better positioned to utilize their technological resources effectively. EF → CFact → I4R: The mediation effect of 0.070 (p = 0.016) suggests that regulatory and competitive pressures are more effective in driving Industry 4.0 readiness when aligned with an adaptive cultural environment. This finding is consistent with Ilina and Klypin’s (2020) observations on the role of regulatory support, emphasizing that cultural adaptability can enhance the responsiveness of organizations to external pressures.

Table 7 provides a comprehensive summary of the hypotheses tested in this study, detailing the relationships between key factors and Industry 4.0 readiness (I4R) within Russian industries. The results as presented reveal that technological readiness, human capital development, strategic planning, and environmental influences significantly contribute to Industry 4.0 readiness. Specifically, hypotheses 1, 2, 3 and 5 were supported, demonstrating the importance of these structural and environmental components in facilitating digital transformation.

These findings suggests that Russian industries should prioritize investments in digital infrastructure and workforce training to enhance readiness, supporting findings by Dalenogare et al. (2018) and Shrigiriwar and Bhalerao (2022). Strategic Factors (H3) and Environmental Factors (H5) also positively influenced readiness (β = 0.220, p = 0.015; β = 0.340, p < 0.001), indicating that structured planning and regulatory support are crucial for adoption. This aligns with prior studies (Machado et al., 2019) and highlights the importance of both internal and external drivers in promoting Industry 4.0. Cognitive Factors (H4) were not significant (β = 0.100, p = 0.292), suggesting that individual attitudes toward technology may be less impactful in Russian industries compared to structural factors.

Cultural factors significantly mediated the relationships between human capital, technological, and environmental factors, and Industry 4.0 readiness. For instance, cultural alignment enhanced the effect of human capital on readiness (β = 0.060, p = 0.021), suggesting that fostering an adaptive culture can amplify the benefits of workforce and technological investments (Hofstede, 1980).

The findings reveal strong support for hypotheses related to technological, human capital, strategic, and environmental factors, affirming their critical roles in shaping Industry 4.0 readiness. This aligns with previous literature on the enabling conditions required for Industry 4.0, as indicated by studies such as Solodova et al. (2021) and Ilina and Klypin (2020), which emphasize the significance of both technological infrastructure and workforce development for digital transformation.

Discussion, and implications for research and practice

This study represents the first effort to examine “Industrial Readiness for Adoption of Industry 4.0” within the context of the Ghanaian industrial sector. In addition to evaluating the overall readiness of industries for Industry 4.0 (I4.0), the study aimed to assess the status of industries in key regions, propose a readiness index for the adoption of I4.0, examine the human and technological factors affecting industrial readiness (IR) for I4.0, identify hindrances to its implementation, and advance workable solutions to promote industrial readiness for Industry 4.0.

The findings align with the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), connecting Technological Factors (TF) and Human Capital Development (HCD) to facilitating conditions, which are critical for Industry 4.0 readiness (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Environmental Factors (EF) reflect the influence of external pressures, corresponding to UTAUT’s social influence construct. The role of Cultural Factors (CFact) as a mediator enriches UTAUT by demonstrating that cultural alignment enhances readiness, consistent with Hofstede’s (1980) perspective on the impact of cultural values. This adaptation provides a comprehensive framework that incorporates both technological and cultural influences on Industry 4.0 adoption in Russia. Our findings reveal that most industries in the sampled regions are manufacturing-oriented and small to medium-scale. We developed a readiness index based on 15 questions about I4.0’s enabling technologies, categorizing readiness levels from Embryonic to Ready. The results indicate that, on average, industries possess only 7.0% knowledge about enabling technologies, suggesting an embryonic stage of readiness with limited familiarity with I4.0 technologies.

The study’s reliability and validity were confirmed through Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (BTS) and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, both yielding satisfactory results (KMO > 0.5 and BTS < 0.001). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) ensured that the data fit the model well, satisfying all validity criteria.

Significantly, we found that Human Capacity Development, Technology-Related Factors, Strategic Factors, Environmental Factors, and cultural factors substantially impact Industry 4.0 readiness. Mediation analysis indicated that cultural factors significantly mediate between various independent variables and Industry 4.0 readiness. These findings align with the hypotheses supported through structural path model analysis.

This study offers several practical implications for stakeholders, institutions, and decision-makers aiming to enhance industrial readiness for Industry 4.0. Firstly, the findings highlight the need to improve strategy implementation mechanisms. Many industries reported poorly executing formulated policies and regulations as a major barrier to technology adoption. To create a more conducive environment for adopting new technologies, stakeholders should focus on refining strategic implementation processes.

Secondly, the study identifies customs hurdles as a significant challenge when importing new technologies. The government should streamline customs processes to facilitate smooth technology adoption, making it easier for industries to import necessary technologies. By removing these barriers, industries can more readily embrace and integrate new technologies into their operations.

Thirdly, there is a critical need for developing specific mechanisms to support technology implementation. This could involve creating dedicated units or task forces within industries to oversee and support the integration of new technologies. Such mechanisms would ensure that industries have the necessary infrastructure and support to adopt and utilize Industry 4.0 technologies effectively.

Limitations, conclusions and future directions

Despite the comprehensive approach and significant findings, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. One major limitation is the geographic focus, as the study was conducted primarily within specific Moscow and findings may not be generalizable Future studies could benefit from a larger and more diverse sample to enhance the generalizability of the results. The study’s cross-sectional design, which captures data at a single point, further limits the ability to infer causal relationships between variables. Longitudinal studies are recommended to observe changes and trends over time, providing a deeper understanding of the factors influencing Industry 4.0 readiness.

The reliance on self-reported measures from respondents introduces potential biases such as social desirability bias and recall bias. Future research could incorporate objective measures and triangulate data sources to enhance the reliability and validity of the findings. Furthermore, the study overlooked other relevant factors influencing Industry 4.0 readiness, such as organizational culture, leadership styles, and specific technological capabilities. Future research should consider these additional factors to provide a more comprehensive analysis.

The study findings underscore the importance of investing in human capital. A major challenge is the lack of skilled manpower to operate new technologies. Industries must invest in comprehensive training programs and continuous professional development to build a workforce that effectively leverages Industry 4.0 technologies. This investment in human capital is essential for successfully adopting and implementing advanced technologies.

Lastly, ensuring robust policy and regulatory support is crucial for mitigating the challenges faced by industries in adopting Industry 4.0 technologies. Creating incentives for innovation and supporting research and development can help industries overcome barriers and enhance their readiness for digital transformation. These practical implications provide a roadmap for industries and policymakers to enhance readiness and successfully navigate the complexities of Industry 4.0 adoption.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Gumashvili Megi, Yiping Mu; data collection: Addo Prince Clement, Gumashvili Megi; analysis and interpretation of results: Addo Prince Clement, Kiti Kanokon, Kulbo Nora Bakabbey, Baidoo Bernard Ekow; draft manuscript preparation: Menezes Dalila Batista de Sousa de, Addo Prince Clement, Bakabbey Kulbo, Gumashvili Megi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Addo P.C.], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This research has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Akenten Appiah-Menka University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development (AAMUSTED-IRB) ierc@aamusted.edu.gh.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Arnold, C., Kiel, D., & Voigt, K. I. (2016). How the Industrial Internet of Things changes business models in different manufacturing industries. International Journal of Innovation Management, 20(8), 1640015. [Google Scholar]

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R. N., Mendonca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J. et al. (2000). Impact of culture on human resource management practices: A 10-country comparison. Applied Psychology, 49(1), 192–221. [Google Scholar]

Barclay, D. W., & Smith, C. H. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Studies, 2(2), 285–309. [Google Scholar]

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). New York, NY, USA: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

Chiarini, A., Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2020). Industry 4.0 strategies and technological developments. An exploratory research from Italian manufacturing companies. Production Planning & Control, 31(16), 1358–1398. [Google Scholar]

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Modern Methods for Business Research, 295(2), 295–336. [Google Scholar]

Davis, F. D. (1985). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results [Doctoral dissertation]. Cambridge, MA, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. [Google Scholar]

Dalenogare, L. S., Benitez, G. B., Ayala, N. F., & Frank, A. G. (2018). The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. International Journal of Production Economics, 204, 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.08.019 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fedyunina, A. A., Gorodnyi, N. A., & Simachev, Y. V. (2024). How the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies is related to participation in global and domestic value chains: Evidence from Russia. International Journal of Information Management, 64, 102002. [Google Scholar]

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar]

Frank, A. G., Dalenogare, L. S., & Ayala, N. F. (2019). Industry 4.0 technologies: Implementation patterns in manufacturing companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 210, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

Gunal, M. M. (2019). Simulation and the fourth industrial revolution. In: Simulation for Industry 4.0 (pp. 1–17Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04137-3_1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). London, UK: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 40(3), 414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Harrington, D. (2009). Confirmatory factor analysis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Heather, N., Rollnick, S., & Bell, A. (1993). Predictive validity of the Readiness to Change Questionnaire. Addiction. 88(12), 1667–1677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02042.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization. 10(4), 15–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1980.11656300 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ilina, I., & Klypin, A. (2020). Scientific and technological advancement of the Russian Federation: Current state and prospects. Science Governance and Scientometrics Journal, 15(4), 458–485. [Google Scholar]

Jacob, K. L., Christopher, M. S., & Neuhaus, E. C. (2011). Development and validation of the cognitive-behavioral therapy skills questionnaire. Behavior Modification, 35(6), 595–611. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Jideani, A. I. O., Mutshinyani, A. P., Maluleke, N. P., Mafukata, Z. P., Sithole, M. V. et al. (2020). Impact of industrial revolutions on food machinery—an overview. Journal of Food Research, 9(5), 42. https://doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v9n5p42 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kagermann, H., Wahlster, W., & Helbig, J. (2013). Recommendations for implementing the strategic initiative Industrie 4.0: Securing the future of German manufacturing industry. Acatech-National Academy of Science and Engineering, 72, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

Kumar, V., & Korovin, G. (2022). A comparision of digital transformation of Industry in the Russian federation with the European union. In: International Scientific Conference on Digital Transformation in Industry: Trends, Management, Strategies, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

Machado, C. G., Winroth, M. P., & da Silva, E. H. D. R., (2019). Sustainable manufacturing in Industry 4.0: An emerging research agenda. International Journal of Production Research, 57(8), 165–171. [Google Scholar]

Oesterreich, T. D., & Teuteberg, F. (2017). Understanding the implications of digitisation and automation in the context of Industry 4.0: A triangulation approach and elements of a research agenda for the construction industry. Computers in Industry, 83(4), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2016.09.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pacchini, A. P. T., Lucato, W. C., Facchini, F., & Mummolo, G. (2019). The degree of readiness for the implementation of Industry 4.0. Computers in Industry, 113(B), 103125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compind.2019.103125 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Purwanto, M. (2024). Sustainable leadership: A new era of leadership for organizational sustainability and challenges. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation, XI(III), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.51244/IJRSI.2024.1103007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Saudi, M. H. M., Sinaga, O., Roespinoedji, D., & Razimi, M. S. A. (2019). Environmental sustainability in the fourth industrial revolution: The nexus between green product and green process innovation. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 9(5), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijeep.8281 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Seok, S., & DaCosta, B. (2014). Distinguishing addiction from high engagement: An investigation into the social lives of adolescent and young adult massively multiplayer online game players. Games and Culture, 9(4), 227–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412014538811 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shrigiriwar, N, & Bhalerao, V (2022). Education 4.0 in the era of fourth industrial revolution. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology, 2(2), 64–68. https://doi.org/10.48175/IJARSCT-7415 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Solodova, E., Solovova, N., & Kalmykova, D. (2021). Innovative industry development in the Russian federation. 1978–1985. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.09.02.222 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Spittaels, H., Foster, C., Oppert, J. M., Rutter, H., Oja, P. et al. (2010). Assessment of environmental correlates of physical activity: Development of a European questionnaire. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 7(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

Telang, A. (2019). Fourth Industrial revolution and health professions education. Archives of Medicine and Health Sciences, 7(2), 265. https://doi.org/10.4103/amhs.amhs_155_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tortorella, G. L., & Fettermann, D. (2018). Implementation of Industry 4.0 and lean production in Brazilian manufacturing companies. International Journal of Production Research, 56(8), 2975–2987. [Google Scholar]

Tung, R. L. (2008). The cross-cultural research imperative: The need to balance cross-national and intra-national diversity. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(1), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400331 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Urbach, N., & Ahlemann, F. (2010). Structural equation modeling in information systems research using partial least squares. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 11(2), 5–40. [Google Scholar]

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2023). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 70, 102644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102644 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Venkateshalu, B. A. (2023). An Indian perspective of fourth industrial revolution. International Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Studies, 5(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.33545/26648652.2023.v5.i1a.42 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

World Economic Forum (2021). Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution Russia [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 9]. Retrieved from: https://www.weforum.org/press/2021/10/russia-joins-centre-for-the-fourth-industrial-revolution-network/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools