Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Factors of intention to learning transfer in apprenticeships: Results and implications of a chain mediation model

1 School of Education Science, Hanshan Normal University, Chaozhou, 521041, China

2 Department of Education, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, 41566, Republic of Korea

3 Teachers Development Center, Hanshan Normal University, Chaozhou, 521041, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xin-Xin Chen. Email: ; Young-Sup Hyun. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 393-401. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068038

Received 05 January 2025; Accepted 11 May 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study utilized a sequential mediating model to examine the role of motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy in the relationships between perceived content validity, mentoring function, continuous learning work culture and intention to transfer learning. The sample comprized 429 final-year apprentices in Guangdong province, China (females = 69.9%, Engineering & Medicine = 69%, mean age = 20.99, SD = 1.60). The apprentices completed standardized measures of motivation to learn, transfer self-efficacy perceived content validity, mentoring function, and continuous learning work culture. Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the data. Results showed perceived content validity, mentoring function, continuous learning culture to predict intention to transfer learning. Of these factors, perceived content validity was the strongest predictor of intention to transfer learning. Of these factors, perceived content validity was the most influential predictor of intention to transfer learning. The motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy sequentially mediated the relationship between mentoring function and intention to learning transfer to be stronger than by either alone. Although perceived content validity and continuous learning culture exhibited no significant direct effects on intention to transfer learning, they demonstrated positive indirect associations with intention to transfer via motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy. These study findings extend the applications of the learning transfer framework to individuals undergoing apprenticeship training which also would apply to other a long-term work-based learning programs.Keywords

Apprenticeships provide work learning transfer and application of competencies both within and across industry types, thereby easing the transition from one setting to another (Billett, 1993; Burke & Hutchins, 2008; Poortman et al., 2011). However, research reveals that companies often view apprentices as not matching the performance levels of skilled staff. Apprentices, on the other hand, report struggling to apply theoretical knowledge and practical skills in real work scenarios (Blechinger & Pfeiffer, 1996; Jia, 2018; Chen & Chen, 2021; Zeng et al., 2024). Intention to learning transfer is the ultimate end goals of apprenticeship training. Intention to learning transfer refers to trainees’ motivation at the end of training to apply newly acquired knowledge and skills (Foxon, 1993; Al-Eisa et al., 2009). Learning transfer refers to the degree to which trainees effectively apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes gained in a training context to the job (Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Blume et al., 2010). The level of learning transfer is considered a direct and effective way to assess the success of employee training programs in an organization (Holton et al., 2000). Yet, the correlates of intention to learning are unclear for guiding vocational training by the critical qualities of perceived content validity, mentoring function, and continuous learning culture.

Perceived content validity and intention to learning transfer

Perceived content validity is about the similarity between the skills and knowledge taught in training and the performance expectations in their job. It is a crucial attitudinal factor among the personal variables that influence an individual’s intention to apply learned skills in the workplace (Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Holton et al., 2000; Gegenfurtner et al., 2009). A critical aspect of training transfer is the ability of trainees to apply their newly acquired knowledge and skills to their jobs. If the learning content is not perceived as aligning well with the trainees’ job roles, it is less likely to result in effective transfer (Lim & Johnson, 2002), depending on the mentoring function.

Mentoring function and intention to learning transfer

Mentoring function involves mentors offering support in various forms, including helping with career progression, providing psychological encouragement, and acting as role models (Scandura, 1992). Mentors do not merely offer the typical supervisory support or peer support found in ordinary organizational settings; they may also provide other forms of social support (Hamilton, 1989). The mentor’s role in training apprentices in complex and dynamic work environments is crucial for applying the learned knowledge and skills effectively in job roles (Zeng et al., 2024). Mentoring has been shown to positively affect learning outcomes and knowledge transfer in modern apprenticeship (Fleig-Palmer, 2009; Poortman et al., 2011). The mentoring function indirectly predicts the trainees’ learning transfer through the motivation to train (Chien, 2011). While there have been no studies directly assessing the impact of mentoring functions on intentions to transfer learning, existing research suggests that social support from supervisors or peers significantly influences individuals’ intent to learning transfer (Gegenfurtner et al., 2009; Hyun, 2020).

Continuous learning culture and intention to learning transfer

Continuous learning culture reflects an organizational belief system that values learning as a key responsibility for all employees and supports both learning and its application on the job through formal and informal systems (Tracey et al., 1995; Bates, 2001; Wong, 2012). Poortman (2007) emphasizes the critical role of organizational culture in shaping the learning experiences of apprentices, which has a positive effect on their learning outcomes.

Additionally, organizational culture has been identified as a consistent predictor of the intention to transfer learning to the workplace across different Human Resource Development (HRD) frameworks, as noted by researchers including Bates (2001), Egan et al. (2004), and Gegenfurtner et al. (2009). Specifically, Gegenfurtner et al. (2009) highlights the central influence of organizational culture on employees’ intentions to apply their learning in the workplace. Several studies have shown continuous learning culture is positively related to trainees’ transfer motivation (Bates, 2001; Bates & Holton, 2004; Egan et al., 2004). Trainees who perceive a strong culture of continuous learning are more inclined to have a greater intention to use the skills they have been trained in.

Motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy mediation

Motivation to learn as the trainee’s desire to learn training content (Noe, 1986) is crucial for transfer intention (Gegenfurtner et al., 2009). It rests on transfer self-efficacy or the motivation to learn (Alvelos et al., 2015).

Transfer self-efficacy refers to one’s belief in their ability to maintain newly learned knowledge and skills over time and generalize them to novel work contexts (Washington, 2002). As a type of specific self-efficacy (Wong, 2012), is critical because individuals may fail to maintain learned skills if they lack confidence in transferring new knowledge and skills to the workplace (Washington, 2002). Self-efficacy is regarded as another major individual antecedent of transfer intention and has been widely found to predict participants’ intention to learning transfer (Tai, 2006; Devos et al., 2007; Chiaburu & Lindsay, 2008; Gegenfurtner et al., 2009; Al-Eisa et al., 2009). Prior research shows perceived content validity enhances self-efficacy (Bhatti & Kaur, 2010; Hwang et al., 2017). Mentoring function also boosts self-efficacy, though some studies found no direct effect (Jun et al., 2018; Chen, 2020).

Previous research shows motivation to learn strongly predicts post-training self-efficacy (Colquitt et al., 2000; Gegenfurtner et al., 2009). Therefore, this study hypothesizes the mediating effects of motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy on the relationship between predictive variables and the intention to transfer knowledge.

The learning transfer (Baldwin & Ford, 1988) is particularly pertinent to this study. Learning transfer refers to the process by which knowledge and skills acquired in training are successfully applied to the actual workplace and their use is sustained (Baldwin & Ford, 1988). Baldwin and Ford (1988)’s classic model divides this process into three core phases: Training Input (encompassing trainee characteristics, training design characteristics, and work environment characteristics), Training Output (level of learning and retention), and Transfer Conditions (application and sustainment). Intention to learning transfer is considered a key driver influencing whether training content is translated into actual work behavior, and it typically occurs prior to actual application (Noe, 1986; Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Gegenfurtner et al., 2009).

Building upon this, Gegenfurtner et al. (2019) proposed an integrated model of intention to transfer, aiming to systematically explain the various factors influencing trainees’ intention to transfer. The model emphasizes that intention results from the interplay of individual factors (e.g., attitudes toward training, motivation to learn), training design and implementation quality, and organizational environment factors (e.g., internal norms, organizational culture). Specifically, within these individual factors, motivation to learn is a powerful predictor of post-training self-efficacy, which in turn acts as the core individual driver for the intention to transfer learning (Gegenfurtner et al., 2009; Al-Eisa et al., 2009).

Based on social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986), the hierarchy of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991), it is understood that personal, behavioral, environmental, and self-regulatory processes interact dynamically. The interaction between individuals and external factors can stimulate the motivation to learn, which subsequently enhances individuals’ self-efficacy and influences their decisions regarding learning behaviors—specifically, whether to apply their new learning to their job. Moreover, Vallerand’s (1997) hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which suggests that social environmental factors influence an individual’s motivation level, subsequently shaping their cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

The Chinese apprenticeship setting

Modern Chinese apprenticeship, known as school-enterprise cooperation programs, integrate classroom-based education with workplace learning under the guidance of industry experts (Xie, 2013; Jia, 2018; Li, 2018). In context of modern Chinese apprenticeship, apprentices acquire new knowledge and skills by imitating and learning from their mentors’ guidance and feedback, as well as by observing their work practices in authentic work environments. Therefore, many scholars regard the mentor-apprentice relationship in the workplace as a form of mentoring (Chien, 2011; Chen, 2020; Huang, 2020).

Existing research on Chinese apprenticeships has primarily explored core characteristics, international comparisons, pedagogical processes, pilot projects, and challenges and strategies (Chen, 2014; Shen & Lei, 2016; Gao & Gao, 2022; Zeng et al., 2024). Regarding the training outcome of apprenticeships, many studies suggest that it is influenced by organizational factors such as institutional support (Jia, 2018; Dong & Su, 2020; Zeng et al., 2024) and the workplace learning environment (Poortman, 2007; Chen & Chen, 2021); curriculum design factors like mentoring and mentor-apprentice relationships (Dong & Su, 2020; Gao & Gao, 2022), and training content (Poortman, 2007; Chen & Chen, 2021); as well as apprentices’ individual factors (Poortman, 2007; Dong & Su, 2020; Chen & Chen, 2021).

However, these studies generally focus on descriptive understanding and often lack scientific data support (Chen, 2014). Although quantitative research on apprenticeships is relatively scarce, some studies have begun to focus on factors influencing their training outcomes. For example, Farris (2001) examined the relationship between apprentices’ demographic characteristics and factors affecting learning transfer (such as self-efficacy, motivation, and peer support), but did not delve into specific predictors of learning transfer. Among these, mentoring function has received considerable attention from scholars. Huang (2020) found that mentoring function has a significant positive impact on both the organizational socialization and job satisfaction of apprentices in the life insurance sales sector. Furthermore, scholars have noted the mediating role of individual psychological factors between mentoring function and training outcomes. Specifically, Chien’s (2011) study revealed that mentoring function positively influences learning transfer by enhancing apprentices’ motivation to learn, with motivation to learn playing a fully mediating role. Similarly, Chen (2020) also found that self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between mentoring function and apprentices’ employability.

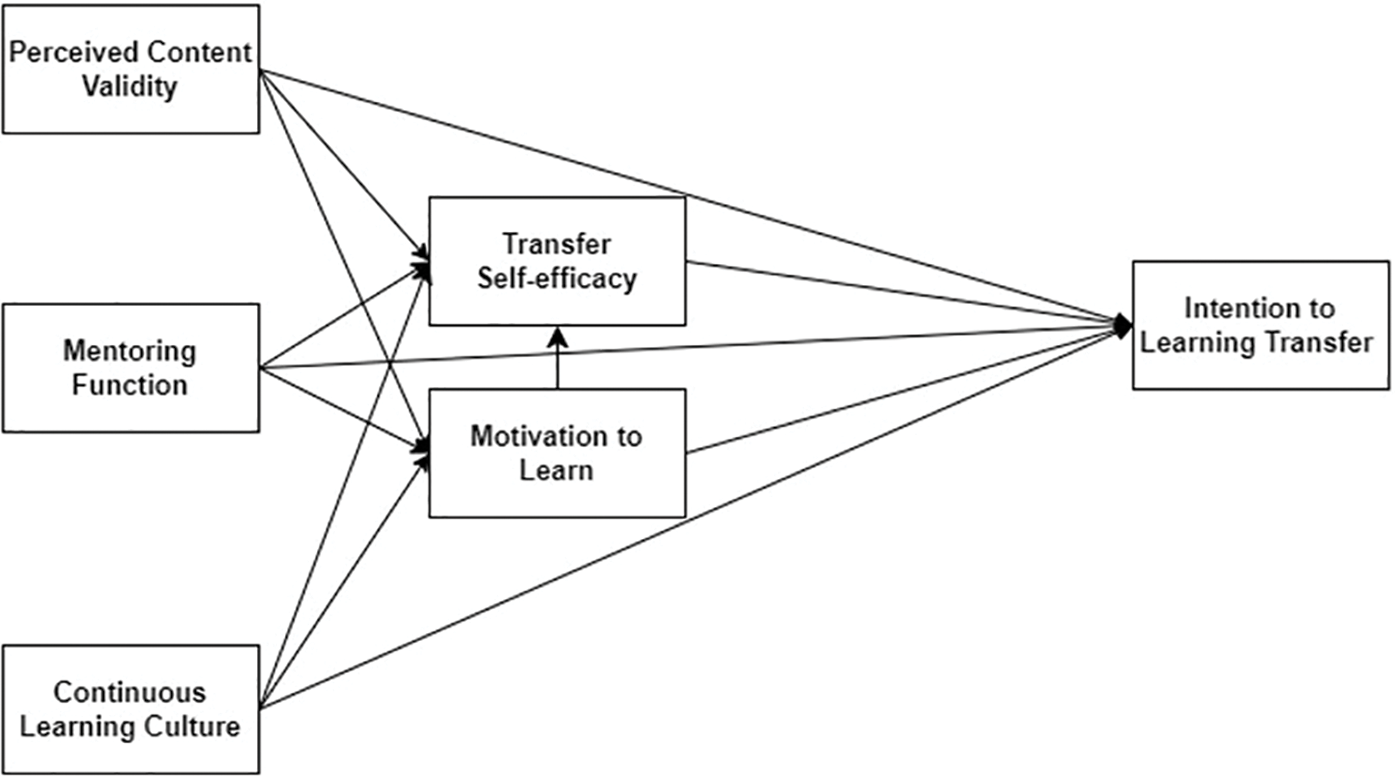

This study aimed to test a serial mediation pathway comprizing predictors → motivation to learn → transfer self-efficacy → intention to learning transfer. Thus, a chain mediator model is proposed (see Figure 1) and tested the following hypotheses:

H1: Motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy sequentially mediate the relationship between perceived content validity and intention to learning transfer.

H2: Motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy sequentially mediate the relationship between mentoring function and intention to learning transfer.

H3: Motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy sequentially mediate the relationship between continuous learning culture and intention to learning transfer.

Figure 1: Hypothesized model

The participants were apprentice students in their final year of study at vocational colleges in Guangdong Province, China. The final sample consisted of 429 participants (with a retention rate of 85.3%), which were employed to test the proposed model. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 24 years (M = 20.99, SD = 1.60), with 300 (69.9%) identifying as female and 129 (30.1%) identifying as male. The engineering and medicine sectors accounted for the majority of participants, representing 69%.

The response format for all measures and items was a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). For the measures, a higher score indicated a higher level of that variable. All measures exhibited good reliability and acceptable correlations with relevant variables (implying good criterion-related validity).

Holton et al.’s (2000) 7-item scale of the LTSI (α = 0.84) was used to measure perceived content validity. A sample item is “What is taught in apprenticeship learning closely matches my job requirements.”

Scandura and Ragins’s (1993) 15-item scale was utilized to assess mentoring function. This scale encompasses three dimensions: career development, psychosocial support, and role modeling, with reported Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.70 to 0.81 for each dimension. Sample items include “Mentor took a personal interest in my career” (career development), “I share personal problems with my mentor” (psychosocial support), and “I try to model my behavior after my mentor” (role modeling).

The continuous learning culture was rated using the Chinese short version from Wong (2012) (α = 0.853) who used Tracey et al.’s (1995) scale with a minor modification. The measure consists of seven items, with an example being “The workplace where I have the on-the-job learning has a progressive atmosphere”.

Noe and Schmitt’s (1986) 7-item scale (α = 0.98) was used to measure motivation to learn. Sample item is “I try to learn as much as can from the apprenticeship program.”

Washington’s (2002) 10-item scale was used to measure transfer self-efficacy (α = 0.91), consists of two dimensions: maintenance self-efficacy and generalization self-efficacy. Sample items include “Maintaining my newly trained skills was probably something I would be good at” (maintenance), and “I believe that generalizing my training to different tasks and settings was a skill that I can master” (generalization).

Intention to learning transfer

Machin and Fogarty’s (2004) 11-item scale (α = 0.90) was used to measure intention to learning transfer with an example being “I will look for opportunities to use the skills which I had learned”.

This study received ethical clearance from the Research and Ethics Committee of Hanshan National University in China (2025010302). Participants consented for study. They were also notified that their involvement in the study was completely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any point during the process. The participants completed the surveys on WeChat, an online platform.

The current research employed IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 and Mplus Editor 8.3 for data analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) to assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the indicators for the six latent variables. Subsequently, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were examined. Following this, structural equation modeling (SEM) with MLE in Mplus Editor 8.3 was utilized to test the proposed mediation model. Robust maximum likelihood estimation was applied for the non-parametric percentile bootstrap with deviation correction, using a 95% confidence interval based on a sample size of 1000 (Shrout & Bolger, 2002).

The Cronbach’s α, means, standard deviations, and correlations between the variables are presented in Table 1. The Cronbach’s α ranged from 0.894 to 0.944, indicating good reliability of the scales (Meyers et al., 2016). Concerning correlations, the lowest was between continuous learning culture and perceived content validity (r = 0.535, p < 0.001), and the highest was between intention to learning transfer and transfer self-efficacy (r = 0.739, p < 0.001). A correlation ranging from 0.65 to 0.85 indicates a good positive correlation, while 0.85 and above indicates a strong positive correlation (Cohen et al., 2000). However, only a correlation exceeding 0.90 is considered multicollinearity (Meyers et al., 2016). Therefore, it could be considered that there was no problem of multicollinearity among the variables.

This study utilized a self-report questionnaire method, which could introduce common method variance. To mitigate potential serious issues related to common method variance, we thoroughly explained our confidentiality protocols to participants during data collection and incorporated deception detection items. Statistically, we applied a structural equation model to perform a Harman’s single-factor test on all items (Podsakoff et al., 2012). The analysis revealed a poor fit of the model, χ2/df = 2721.339/275 = 9.895, TLI = 0.657, CFI = 0.686, SRMR = 0.088, RMSEA = 0.144. Therefore, the study does not exhibit significant common method bias.

Validation of structural model

The measurement model demonstrated adequate fit with the data χ2/df = 2.848, CFI = 0.917, TLI = 0.907, SRMR = 0.059, RMSEA = 0.066. The CFA results provided evidence for convergent validity. Standardized factor loadings for all indicators were statistically significant and above the 0.50 threshold, ranging from 0.572 to 0.907 (Hair et al., 2010). All constructs exceeded the 0.70 cut-off for composite reliability, with values ranging from 0.855 to 0.933. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) for each factor surpassed the 0.50 criterion, spanning from 0.559 to 0.761. Meeting these three criteria confirms adequate convergent validity of the measured constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

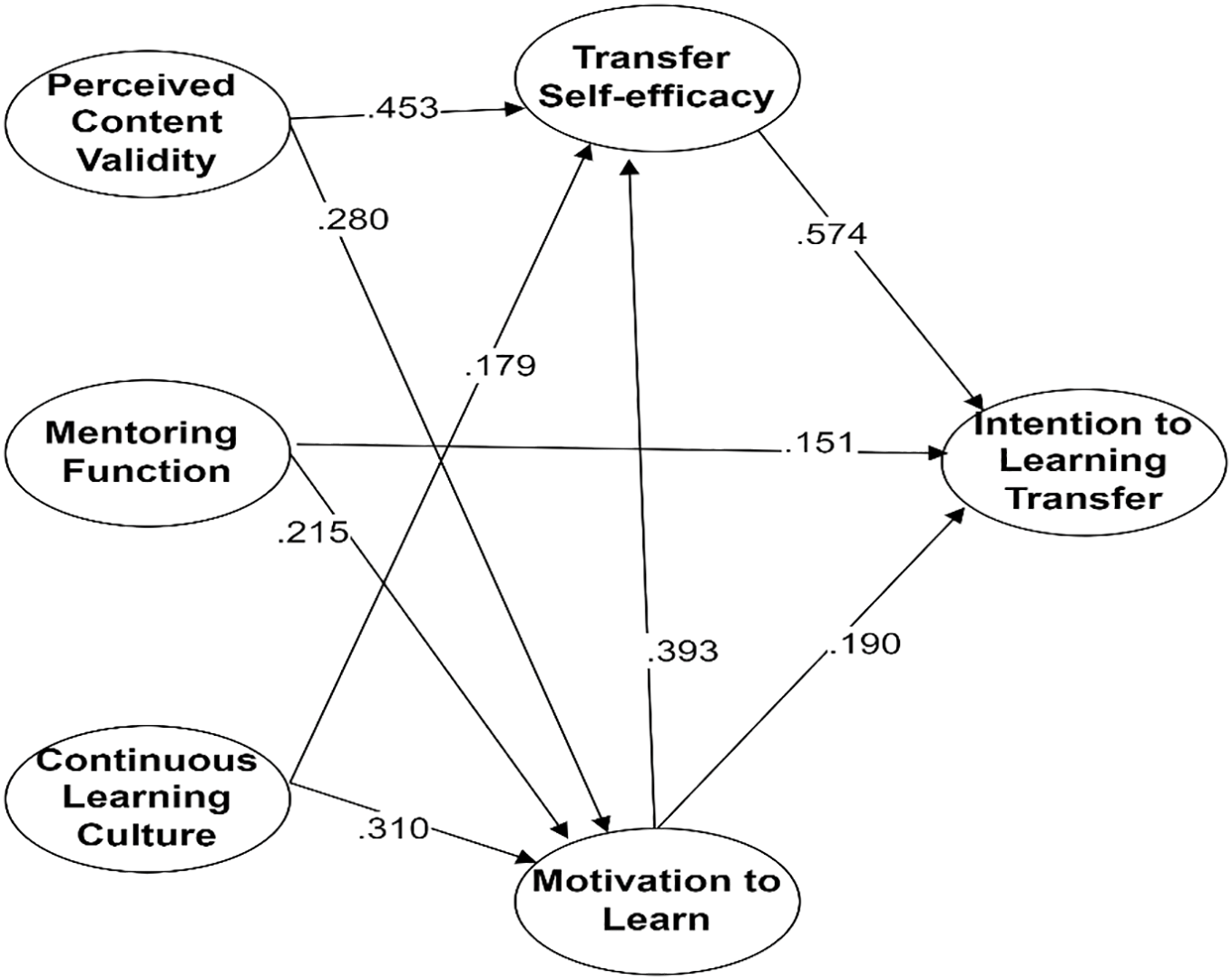

SEM models were then specified, including all constructs as latent variables (see Figure 2). The model fit the data adequately, χ2/df = 2.848, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.919; TLI = 0.909; SRMR = 0.059; and RMSEA = 0.066 (90% CI [0.061, 0.069]). Results from structural equation modeling indicated that mentoring function directly and positively impacted intention to learning transfer (β = 0.151, p < 0.01). However, perceived content validity and continuous learning culture did not directly and positively influence intention to learning transfer. This model accounted for 70.9% of the variance in intention to learning transfer.

Figure 2: Influencing factors of intention to learning transfer in Chinese apprenticeships. Note. Values denote standardized estimates of the paths.

Motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy mediation effects

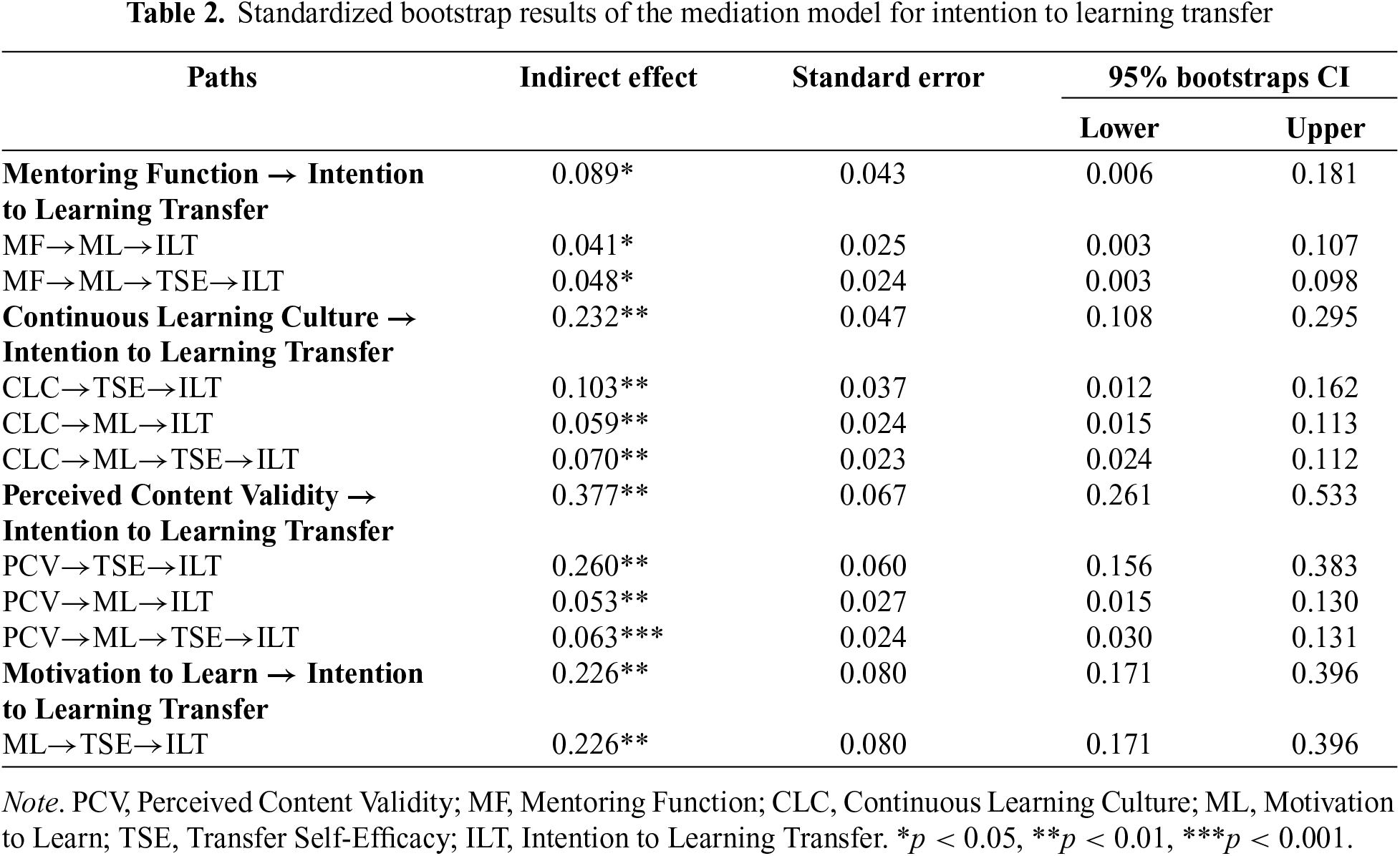

Table 2 presents the results of standardized direct and indirect effects using latent variables. Specifically, the total effect of mentoring function on intention to learning transfer was statistically significant (β = 0.241, p < 0.01). This effect comprised a direct effect (β = 0.151, p < 0.05) and two indirect effects through the mediators, mediated by motivation to learn (β = 0.041, 95% CI [0.003, 0.107], p < 0.05) and dually mediated by motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy in serial (β = 0.048, 95% CI [0.003, 0.098], p < 0.05). This result provides support for H2. However, transfer self-efficacy did not mediate the relationship between mentoring function and the intention to transfer learning.

Perceived content validity had significant indirect effects on intention to learning transfer through two pure mediation paths and one serial multiple mediation path. First, the indirect effect through motivation to learn was significant (β = 0.053, 95% CI [0.015, 0.130], p < 0.01). Second, the indirect effect through transfer self-efficacy was significant (β = 0.260, 95% CI [0.156, 0.383], p < 0.01). Third, the sequential indirect effect through motivation to learn and then transfer self-efficacy was also significant (β = 0.063, 95% CI [0.030, 0.131], p < 0.001). The total indirect effect of perceived content validity on intention to learning transfer was β = 0.377, 95% bootstrapped CI [0.261, 0.533]. Thus, H1 is supported.

Like the pattern for perceived content validity, both the indirect effect through transfer self-efficacy purely (β = 0.103, 95% CI [0.012, 0.162], p < 0.01) and the indirect effect through motivation to learn purely (β = 0.059, 95% CI [0.015, 0.113], p < 0.01) were significant. The sequential indirect effect through motivation to learn and then transfer self-efficacy was also verified to be significant (β = 0.070, 95% CI [0.024, 0.112], p < 0.01). The total indirect effect of continuous learning culture on intention to learning transfer was reported β = 0.232, 95% bootstrapped CI [0.108, 0.295]. Therefore, H3 is supported.

The current study aimed to investigate mediating mechanisms of perceived content validity, mentoring function, and continuous learning culture on intention to learning transfer among college student apprenticeships. The results supported a well-fitting structural path model, which explained 70.9% of the variance in the intention to transfer learning. The proposed structural model is consistent with the learning transfer framework (Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Gegenfurtner et al., 2009), previously used in HRD research. Intention to learning transfer is understood to arise from the interplay of individual, training design, and organizational environment factors in HRD context. The current study provides further evidence that perceived content validity (as an individual factor), mentoring function (as a training design factor), and continuous learning culture (as an organizational environment factor) each exert a positive influence on the learning transfer intention of Chinese apprentices via the sequential dual mediating effects of motivation to learn and training transfer self-efficacy.

The results indicated that perceived content validity and continuous learning culture did not directly influence the intention to transfer learning. This aligns with the mixed findings in past research on whether these factors affect the level of learning transfer (Hwang et al., 2017; Kirwan & Birchall, 2006). The findings are consistent with those of previous studies by Bhatti and Kaur (2010) and Wong (2012), who similarly reported no direct effect. Although perceived content validity and continuous learning culture had no direct impact on learning transfer, their influence was significantly mediated by motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy. This suggested that if an individual lacked learning motivation or had no confidence in their ability to successfully apply the new learned content in a specific situation, they might still lack the intention to transfer learning, even if they believed the content was valid and were in an organizational culture that supported continuous learning.

The results revealed that mentoring function had a direct predictive power on intention to learning transfer. A more robust mentoring function markedly strengthened apprentices’ intention to transfer their learning. Mentors facilitated apprentices’ progress by offering guidance in career advancement, interpersonal skills, and by providing exemplary leadership. When apprentices received positive mentorship, they were better equipped to see the relevance of their training to real-world tasks (Chen & Chen, 2021; Zeng et al., 2024), which in turn boosted their readiness to apply their newfound knowledge and skills in practical settings.

In addition to its direct impact, mentoring function also indirectly affected the intention to transfer learning through the mediation of motivation to learn. This is consistent with the findings of Chien (2011), whose study revealed that the mentoring function positively influences learning transfer by impacting the learning motivation of Chinese apprentices, with learning motivation playing a full mediating role in this process. However, this study revealed that transfer self-efficacy could not serve as the sole mediating factor between mentoring function and intention to learning transfer. This is consistent with the findings of Jun et al. (2018), who similarly observed the lack of a direct enhancement of self-efficacy by mentoring function. Transfer self-efficacy was rooted in an individual’s belief in their capability to successfully apply knowledge in specific work situations (Bandura, 1977; Richman-Hirsch, 2001; Washington, 2002). Our research indicated that although mentors’ positive guidance could aid apprentices in understanding the connection between learning content and real-world work, it did not directly boost their confidence in transferring their learning. Instead, it indirectly influenced changes in self-efficacy by enhancing apprentices’ motivation to learn.

The findings of this study indicated motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy to sequentially mediate the relationship between perceived content validity, mentoring function, continuous learning culture, and the intention to transfer learning. These results align with Colquitt et al. (2000), who, through a meta-analytic investigation, found that the effects of individual and organizational characteristics on learning transfer are mediated by variables such as learning motivation and post-training self-efficacy. Perceived content validity, mentoring function, and continuous learning culture, as key factors in apprenticeship training, can thus directly enhance apprentices’ motivation to learn (Bates, 2001; Chien, 2011; Alvelos et al., 2015). This learning motivation, in turn, reinforces their confidence in their ability to maintain and generalize the newly acquired knowledge, skills, and attitudes from the apprenticeship training and apply them to their work (Colquitt et al., 2000; Gegenfurtner et al., 2009). Ultimately, this self-confidence enhances their intention to transfer their learning (Gegenfurtner et al., 2009). By examining three sequential dual mediation pathways, this study verified how individual, training, and environmental factors, through their interaction within the apprenticeship system, influence learning transfer intention. This aligns with the conclusions of Poortman’s (2007) qualitative research on apprenticeship, further corroborating the perspective that learning outcomes in apprenticeship are a comprehensive reflection of the interplay among the learning environment, learner characteristics, social interaction, and internal acquisition.

Implications for apprenticeship

This research extends the application of the learning of transfer framework (Baldwin & Ford, 1988; Gegenfurtner et al., 2009) to contemporary vocational apprenticeship training initiative. By examining the relevance of training transfer theories within the apprenticeship context and confirming their practicality, our study not only broadens the theoretical application in HRD but also introduces a fresh theoretical lens to the scholarship on apprenticeship. By validating the applicability and practical value of learning transfer theories within the apprenticeship context, this study not only expands their theoretical domain in the HRD field but, more importantly, provides a novel theoretical perspective for apprenticeship scholarship. This perspective is based on individual factors—perceived content validity, motivation to learn, and transfer self-efficacy; the training design factor—mentoring function; and the organizational environment factor—continuous learning culture.

Based on this study’s findings, practitioners should focus on fostering transfer intentions through thoughtful project design and execution, rather than solely concentrating on collaborative frameworks or financial aspects. School-based apprenticeship may suffer from a gap between academic learning and the workplace environment (Billett, 2016; Dong & Su, 2020). Given that all apprentices exhibit some level of transfer intention post-training, it’s imperative for practitioners to implement strategies that enhance the probability of successful transfer initiation and sustainment. Reinforcing selected supportive factors that influence transfer intention before apprentices transition out of the educational setting can bolster the forces driving transfer.

The study’s findings highlight the critical role of learning motivation and the transfer of self-efficacy in enhancing apprentices’ willingness to apply acquired skills. To improve training effectiveness, it is essential for practitioners to emphasize factors that contribute to the growth of positive learning motivation and the transfer of self-efficacy (Colquitt et al., 2000; Gegenfurtner et al., 2009; Chien, 2011; Chen, 2020). This can be accomplished by tailoring training content to align more closely with future job demands and by cultivating an organizational environment that encourages continuous learning and innovation.

The essential role of quality mentor-apprentice relationships in apprenticeships (Chien, 2011; Chen, 2020; Dong & Su, 2020) is further supported by this study’s finding that mentoring directly enhances intention to learning transfer. This finding advances our understanding of how mentorship affects transfer intention by fostering inner motivation and self-efficacy. Mentors should stimulate apprentices’ motivation to learn and help build their self-efficacy in applying new knowledge, skills, and attitudes during the mentoring process, effectively enhancing their willingness to transfer learning.

Limitations and future directions

The present study results need to be considered considering limitations that inform directions for future research. First, the cross-sectional design adopted in this study might not reveal the causal relationship between variables. Future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the research results.

Second, in terms of data collection, all data in this study were self-reported by college students, which might be subjective. To mitigate this, the study implemented specific procedures during both the survey administration and statistical analysis phases to minimize subjective biases. Therefore, indirect methods should be used to measure relevant variables in the future to further validate the research results.

Thirdly, the generalizability of the findings to the broader Chinese apprentice population may be limited by the exclusive focus on samples from school-based programs in Guangdong Province. The lack of unified standards for apprenticeship implementation across China suggests that regional variations may exist. To enhance the external validity and generalizability of the research, future studies should consider testing the proposed model in different geographical locations and among apprentices from a variety of program types and cultural backgrounds.

This study’s findings indicate that perceived content validity, mentoring function, and continuous learning culture may wield influence over an individual’s motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy. Subsequently, these factors, in sequence, may shape the intention to transfer learning within the behavioral process.

The significance of the current study is its contribution of quantitative research that expands on the HRD learning transfer process in a sample of Chinese vocational college apprentices, correctly predicting their intentions to transfer. The data suggest highlighting the dual roles of mentoring function, directly and indirectly influencing intention to learning transfer via the sequential mediation of motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy. Perceived content validity and continuous learning culture indirectly impact intention to learning transfer via motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy. Motivation to learn and transfer self-efficacy appear to be important linkages to intention to learning transfer and its antecedents in vocational training programs.

Acknowledgement: Thank you to our friends and teachers who have provided assistance in the data collection and analysis of this study.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Hanshan Normal University School-Level Research Initiation Program (grant numbers QD202244; QD2024207); the Guangdong Higher Education Society’s “Fourteenth Five-Year” Plan 2024 Higher Education Research (grant number 24GYB43); the 2024 Guangdong Provincial Undergraduate Teaching Quality and Teaching Reform Engineering Project: Excellence Program for Cultivating Publicly-Funded Pre-service Teachers for Primary Education in the Context of Rural Revitalization; and the Hanshan Normal University Guangdong East Regional Education Collaborative Innovation Research Center. The APC was jointly funded by these sources.

Author Contributions: There is no conflict of interest among our members and there is unanimous agreement on the order of attribution of articles. All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Xin-Xin Chen and Wen-Hao Chen. Supervision, methodology and validation was performed by Young-Sup Hyun. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Xin-Xin Chen and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to graduation thesis, data cannot be made publicly available. Investigators may email the corresponding authors if they would like to apply for data access.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee (the Research and Ethics Committee of Hanshan National University, China) (2025010302).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Al-Eisa, A. S., Furayyan, M. A., & Alhemoud, A. M. (2009). An empirical examination of the effects of self-efficacy, supervisor support and motivation to learn on transfer intention. Management Decision, 47(8), 1221–1244. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740910984514 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Alvelos, R., Ferreira, A. I., & Bates, R. (2015). The mediating role of social support in the evaluation of training effectiveness. European Journal of Training and Development, 39(6), 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejtd-12-2014-0081 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baldwin, T. T., & Ford, J. K. (1988). Transfer of training: A review and directions for future research. Personnel Psychology, 41(1), 63–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00632.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

Bates, R. A. (2001). Public sector training participation: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Training and Development, 5(2), 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2419.00128 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bates, R. A., & Holton, E. F.III (2004). Linking workplace literacy skills and transfer system perceptions. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15(2), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1096 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bhatti, M. A., & Kaur, S. (2010). The role of individual and training design factors on training transfer. Journal of European Industrial Training, 34(7), 656–672. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591011070770 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Billett, S. (1993). Evaluating modes of skill acquisition: A report on a research project to determine the effective qualities of three current models of vocational skills acquisition. Nathan, QSL, Austrilia: Griffith University, Centre for Skill Formation Research and Development. Retrieved from: http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/114516. [Google Scholar]

Billett, S. (2016). Apprenticeship as a mode of learning and model of education. Education + Training, 58(6), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1108/et-01-2016-0001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Blechinger, D., & Pfeiffer, F. (1996). Technological change and skill obsolescence: the case of German apprenticeship training (No. 96-15). ZEW Discussion Papers. Retrieved from: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/29394. [Google Scholar]

Blume, B. D., Ford, J. K., Baldwin, T. T., & Huang, J. L. (2010). Transfer of training: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(4), 1065–1105. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352880 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2008). A study of best practices in training transfer and proposed model of transfer. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(2), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1230 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, J. L. (2014). Research on modern apprenticeship in vocational education. Changsha, China: Hunan University Press. [Google Scholar]

Chen, P. J. (2020). Mentoring functions, self-efficacy, and self-perceived employability [Master’s thesis]. Xinbei, Taiwan: Meng Chi University of Technology. Retrieved from: https://hdl.handle.net/11296/hgzxgx. [Google Scholar]

Chen, X. X., & Chen, W. H. (2021). Analysis of influencing factors and promotion of training transfer in modern apprenticeship system in China: Based on the theory of training transfer. Vocational Education Communication, (2), 8–18. [Google Scholar]

Chiaburu, D. S., & Lindsay, D. R. (2008). Can do or will do? The importance of self-efficacy and instrumentality for training transfer. Human Resource Development International, 11(2), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678860801933004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chien, H. Y. (2011). The relation between mentoring function and transfer of training: Trainee motivation as a mediating factor [Master’s thesis]. Taipei, Taiwan: National Taiwan Normal University. Retrieved from: https://hdl.handle.net/11296/wwd439. [Google Scholar]

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th Edition). London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 678–707. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Devos, C., Dumay, X., Bonami, M., Bates, R., & Holton, E. (2007). The Learning Transfer System Inventory (LTSI) translated into French: Internal structure and predictive validity. International Journal of Training and Development, 11(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2419.2007.00280.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dong, L., & Su, H. (2020). The main dilemmas of the modern apprenticeship system in higher vocational education: Manifestations, causes, and countermeasures—A grounded theory study based on 227 pilot colleges. Chinese Vocational and Technical Education, 15, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

Egan, T. M., Yang, B., & Bartlett, K. R. (2004). The effects of organizational learning culture and job satisfaction on motivation to transfer learning and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 15(3), 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1104 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Farris, M. S. (2001). Factors affecting the transfer of related training in a trade union apprenticeship program. Unpublished doctoral dissertation [Doctoral dissertation]. Knoxville, TN, USA: The University of Tennessee. [Google Scholar]

Fleig-Palmer, M. M. (2009). The impact of mentoring on retention through knowledge transfer, affective commitment, and trust [Doctoral dissertation]. Lincoln, NE, USA: The University of Nebraska-Lincoln. [Google Scholar]

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Foxon, M. (1993). A process approach to the transfer of training. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.2104 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gao, M., & Gao, H. (2022). From Pilot demonstration to Chinese characteristics: Retrospect and prospect of modern apprenticeship research in China. Journal of Vocational Education, 38(4), 110–119. [Google Scholar]

Gegenfurtner, A., Veermans, K., Festner, D., & Gruber, H. (2009). Integrative literature review: Motivation to transfer training: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review, 8(3), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484309335970 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. London, UK: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

Hamilton, S. F. (1989). Learning on the job: Apprentices in West Germany. In: The Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

Holton, E. F.III, Bates, R. A., & Ruona, W. E. A. (2000). Development of a generalized learning transfer system inventory. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 11(4), 333–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/1532-1096(200024)11:4<333::aid-hrdq2>3.0.co;2-p [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, T. W. (2020). The Effects of mentoring functions on organization socialization content and job satisfaction: cross generation comparisons [Master’s thesis]. Chaoyang, China: Chaoyang University of Technology. [Google Scholar]

Hwang, B. Y., Yang, Y. S., & Kim, M. S. (2017). Impact factors of KS-QFD training participants of 3 years over startups on transfer intension. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship, 12(6), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.16972/apjbve.12.6.201712.1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hyun, Y. S. (2020). The mediated effect of intention to transfer learning on the relationship between supervisor’s support and learning transfer. CNU Journal of Educational Studies, 40(2), 161–189. [Google Scholar]

Jia, W. S. (2018). A research on the operation mechanism of modern apprenticeship in higher vocational colleges in China [Doctoral dissertation]. Shanghai, China: East China Normal University. [Google Scholar]

Jun, S. Y., Han, J. W., Park, K. H., & Lee, H. (2018). The effect of mentoring function on job motivation and nursing performance with a focus on the mediated effect of self-efficacy and outcome expectation. The Korean Journal of Health Service Management, 12(3), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.12811/kshsm.2018.12.3.041 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kirwan, C., & Birchall, D. (2006). Transfer of learning from management development programmes: Testing the Holton model. International Journal of Training and Development, 10(4), 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2419.2006.00259.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, Z. (2018). A study on the value of modern apprenticeship in vocational education: From the perspective of epistemology [Doctoral dissertation]. Shanghai, China: East China Normal University. [Google Scholar]

Lim, D. H., & Johnson, S. D. (2002). Trainee perceptions of factors that influence learning transfer. International Journal of Training and Development, 6(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2419.00148 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Machin, M. A., & Fogarty, G. J. (2004). Assessing the antecedents of transfer intentions in a training context. International Journal of Training and Development, 8(3), 222–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-3736.2004.00210.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Meyers, L. S., Gamst, G., & Guarino, A. J. (2016). Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

Noe, R. A. (1986). Trainees’ attributes and attitudes: Neglected influences on training effectiveness. The Academy of Management Review, 11(4), 736. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1986.4283922 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Noe, R. A., & Schmitt, N. (1986). The influence of trainee attitudes on training effectiveness: Test of a model. Personnel Psychology, 39(3), 497–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1986.tb00950.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Poortman, C. L. (2007). Workplace learning processes in senior secondary vocational education [Doctoral dissertation, Enschede, Netherland: University of Twente]. [Google Scholar]

Poortman, C. L., Illeris, K., & Nieuwenhuis, L. (2011). Apprenticeship: From learning theory to practice. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 63(3), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2011.560392 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Richman-Hirsch, W. L. (2001). Posttraining interventions to enhance transfer: The moderating effects of work environments. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scandura, T. A. (1992). Mentorship and career mobility: An empirical investigation. Journal of Investigative Behavior, 13, 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130206 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scandura, T. A., & Ragins, B. R. (1993). The effects of sex and gender role orientation on mentorship in male-dominated occupations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 43(3), 251–265. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1993.1046 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shen, X. P., & Lei, C. L. (2016). The origin, practice andreflection of modern apprenticeship. In: Vocational Education Forum (pp. 32–36). [Google Scholar]

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.7.4.422 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tai, W. T. (2006). Effects of training framing, general self-efficacy and training motivation on trainees’ training effectiveness. Personnel Review, 35(1), 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610636786 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tracey, J. B., Tannenbaum, S. I., & Kavanagh, M. J. (1995). Applying trained skills on the job: The importance of the work environment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80(2), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.2.239 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Vallerand, R. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 271–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60019-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Washington, C. L. (2002). The relationships among learning transfer climate, transfer self-efficacy, goal commitment, and sales performance in an organization undergoing planned change [Doctoral dissertation]. Columbus, OH, USA: The Ohio State University. [Google Scholar]

Wong, W. T. (2012). Assessing the factors affecting employees’ e-learning motivation to transfer [Doctoral dissertation]. Taipei, Taiwan: National Taiwan Normal University. Retrieved from: https://hdl.handle.net/11296/ka9bxh. [Google Scholar]

Xie, J. H. (2013). Discussion on the talent training model of modern apprenticeship system in higher vocational colleges. Vocational Education Forum, (16), 24–26. [Google Scholar]

Zeng, H. X., Xu, Y. F., & Guan, J. (2024). Quality examination of the modern apprenticeship pilot program from the apprentice’s perspective: Current situation, dilemmas, and strategies for improvement. Journal of Vocational Education, 40(2), 99–106. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools