Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Unveiling the dark side of leadership: How exploitative leadership undermines employees’ work-related flow

1 School of Economics and Management, North China Electric Power University, No. 2, Beinong Road, Changping District, Beijing, 102206, China

2 Department of Outreach and Cooperation, North China Electric Power University, No. 2, Beinong Road, Changping District, Beijing, 102206, China

* Corresponding Author: Ruiqi Wang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 335-343. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068040

Received 29 November 2024; Accepted 28 April 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study examined how exploitative leadership undermines employees’ experience of flow with work role overload and traditionalist values. Data were collected from 361 staff members across diverse industries in China (females = 58.17%, mean age = 32.14, SD = 5.83). Structural equation modeling results indicated that exploitative leadership reduces employees’ work-related flow via increased role overload. Furthermore, employees’ traditionality level moderates the exploitative leadership effects on role overload. Specifically, employees with higher traditionality reported lower role overload when experiencing exploitative leadership, suggesting that cultural values may buffer its negative impact. This study contributes to understanding the mechanism and contextual factors linking exploitative leadership to work-related flow, filling a gap in the literature. Organizations are encouraged to reduce exploitative leadership behaviors through leadership development programs and to consider employees’ value orientations when designing work environments.Keywords

In today’s fiercely competitive global market, organizations strive not only to enhance performance but also to prioritize employees’ well-being as a foundation for sustainable development. Work-related flow (WF) plays a crucial role in enhancing employees’ well-being and performance (Liu et al., 2023). Numerous studies have shown that when employees are highly intrinsically motivated, deeply engaged in their work, and enjoy their tasks—in other words, when they achieve a state of flow at work (Bakker, 2008)—they tend to perform better (Bakker, 2008), exhibit greater creativity (Fredrickson, 2011), and experience health and happiness (Bryce & Haworth, 2002; Demerouti, 2006). Leadership, as a crucial component of organizations, significantly influences employees’ work-related flow (Lan et al., 2017; Schermuly & Meyer, 2020). However, these positive outcomes may not hold under exploitative leadership, which prioritizes personal gain over the mutual development of employees and the organization. By definition, exploitative leadership negatively impacts employees’ job performance (Moin et al., 2024; Syed et al., 2021) and service performance (Wu et al., 2021), while also diminishing positive behaviors such as voice (Bajaba et al., 2023), innovation (Wang et al., 2023a), and knowledge sharing (Wang et al., 2023b). Yet, the mechanisms behind exploitative leadership and employees’ work-related flow remain a gap in current research, and particularly in collectivistic cultures like China.

Exploitative leadership and employee’s work-related flow

Exploitative leadership (EL), which is widespread in both Eastern and Western organizations, involves gaining personal benefits through pressuring, manipulating, and impeding subordinates’ growth (Schmid et al., 2019). It is a self-interested leadership style characterized by low hostility and directed toward subordinates (Schmid et al., 2018). It comprises five dimensions: genuine egoistic behaviors, exerting pressure, providing insufficient challenge to followers, taking credit, and manipulating subordinates (Schmid et al., 2019). For instance, exploitative leadership behaviors (e.g., taking credit) can trigger a sense of resource threat in employees, leading to anxiety about future resource depletion and heightened psychological stress (Schmid et al., 2019).

We hypothesize that exploitative leadership weakens employees’ work-related flow based on the following reasons. On one hand, exploitative leadership has been shown to reduce diminishes employees’ harmonious passion (Sun et al., 2023), causing negative emotions, psychological distress (Majeed & Fatima, 2020; Akram et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2021), and even depression (Akhtar et al., 2022), thereby leading to a loss of psychological resources. Drawing on the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, resource loss has a stronger impact than resource gain (Hobfoll et al., 2018). When employees face exploitative leadership, they experience significant psychological resource loss, which hinders their ability to develop strong interest in work (Nielsen & Cleal, 2010), derive enjoyment, and experience flow—a peak state that requires substantial psychological resources and energy (Bakker et al., 2023). On the other hand, exploitative leaders often burden subordinates with repetitive and mundane tasks. These low-skill, low-challenge jobs often bore employees, disrupting the optimal balance between challenge and skill, which is essential for flow (Csikszentmihalhi, 2020; Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Based on the above reasoning, we hypothesize a negative relationship between exploitative leadership and employees’ work-related flow.

Employee’s role overload as a mediator

Role overload (RO) is defined as employees’ perception that they have to manage excessive responsibilities or activities within the constraints of time, ability, and other limitations (Bolino & Turnley, 2005). The COR framework posits that people strive to obtain, maintain, and shield their resources (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2018), aiming to prevent their depletion. The abundance of personal resources is positively correlated with experiencing flow (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). Employees experiencing high levels of role overload often find it difficult to achieve flow at work. This is because, on one hand, role overload induces negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, unease) (Wang & Li, 2021), which drain their psychological resources. On the other hand, when employees feel unable to fulfill multiple role demands, allocating more resources to one role reduces the resources available for others.

We hypothesize that exploitative leadership exacerbates employees’ role overload. First, when exploitative leaders impose excessive work pressure and engage in manipulation, employees’ role tasks and job demands are intensified (Schmid et al., 2019), forcing them to handle more tasks within limited time. When employees perceive that they cannot effectively complete assigned tasks, they experience a significant sense of resource loss (Bacharach et al., 1990; Matthews et al., 2014), which further reduces their resource investment in work tasks (Schmitt et al., 2016). Moreover, when exploitative leadership behaviors accumulate, employees’ ability to recover resources may also be weakened, thereby intensifying role overload. Second, intrinsic resources are essential resources that individuals can utilize (Dawson et al., 2016), and employees are particularly sensitive to the loss of their behavioral resources (Ding et al., 2020, 2022). Finally, sustained perceptions of resource threat weaken employees’ adaptability, hindering their ability to handle evolving role requirements in workplace and recover from the spiral of resource loss (Hobfoll et al., 2015). This may be especially pronounced among employees with traditionalist work values in collectivist cultures.

Employee’s traditionality as a moderator

Traditionality serves as a core cultural orientation in Chinese society (Yang, 2003), characterized by respect for authority and strong recognition of hierarchical relationships (Farh et al., 1997). Cultural values serve as key moderators influencing the effectiveness of leadership behaviors (Cheng et al., 2019; Peng & Wei, 2020). In organizational contexts, traditionalist values often denote an individual’s endorsement of hierarchical relationships rooted in Confucian philosophy, demonstrated by compliance with leaders’ directives (Farh et al., 1997; Yang, 2003). In today’s transitioning Chinese society, cultural values, especially traditionality, exhibit significant diversity and differentiation (Farh et al., 1997). Individuals varying in traditionality display significant differences in their value concepts, cognitive attitudes, and behavioral patterns. Scholars have found that traditionality affects the effectiveness of leaders in influencing subordinates’ cognition and behavior (Cheng et al., 2023; Farh et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2024).

According to COR theory, we posit that employees’ traditionality may buffer the positive relationship between exploitative leadership and role overload. Specifically, high-traditionality employees facing exploitative leadership follow the traditional principle of “superiors above, inferiors below”, perceiving leaders’ pressuring actions as normative rather than as direct threats to their resources. In instances where leaders take credit, high-traditionality employees, with a higher tolerance for hierarchical inequalities (Liu et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2021), show reduced sensitivity and stress (Cheng et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2024), lessening their perception of resource threats and mitigating the positive association between exploitative leadership and role overload. Moreover, high-traditionality employees may be more resilient to exploitative leadership effects by their compliance behaviors (Guan et al., 2016), which help them avoid intense perceptions of role overload and partially disrupting the cycle of resource loss. In contrast, low-traditionality employees perceive superior-subordinate relationships as equal (Farh et al., 2007) and prioritize autonomy and independence in work and interactions. Their lower tolerance for exploitative behaviors, heightened sensitivity to exploitation (Ji et al., 2022), stronger negative emotions (Wang et al., 2012), and lower acceptance of such behaviors make them more likely to experience dual depletion of behavioral and psychological resources, thus heightening their sense of role overload. In summary, we posit that employees’ traditionality can attenuate the positive impact of exploitative leadership on role overload.

China is a society deeply rooted in traditional values, where many enterprises adopt top-down management styles, and exploitative behaviors by leaders frequently occur (Sun et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Ye et al., 2023), causing a range of negative effects on employees. Increasing research has revealed that flow positively impacts employees’ well-being (Liu et al., 2023), as well as their job performance, innovation, and organizational citizenship behavior. Thus, investigating the mechanisms and boundary conditions of exploitative leadership on employees’ work-related flow addresses a critical gap in the literature while offering important practical value.

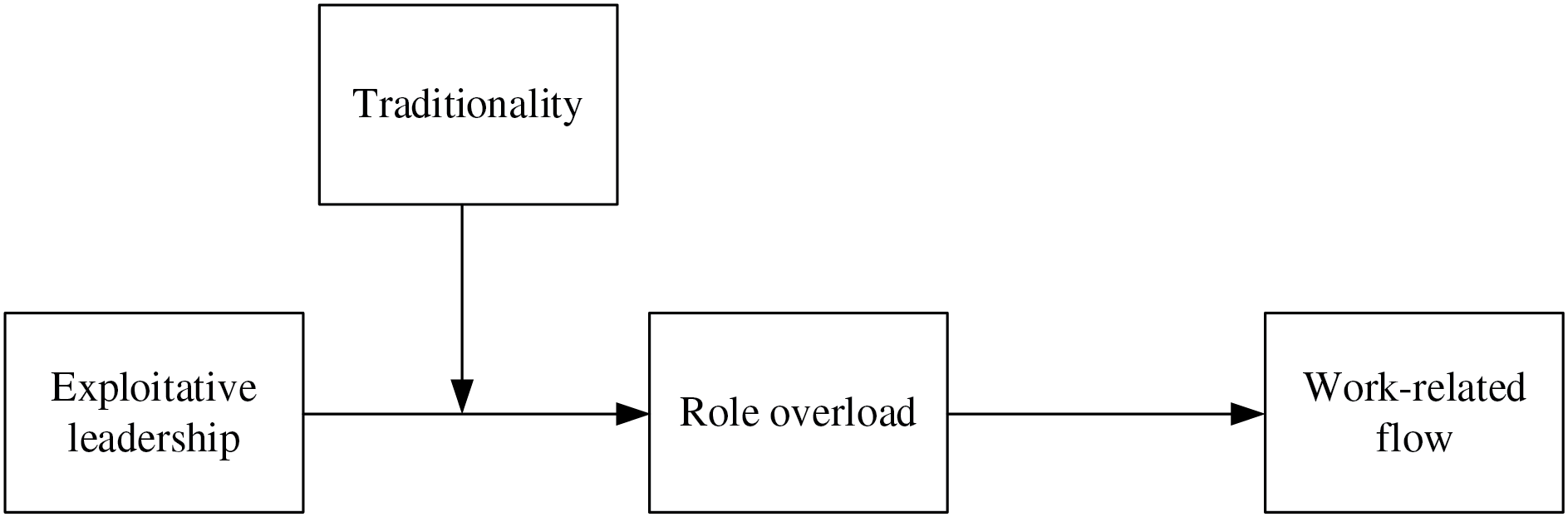

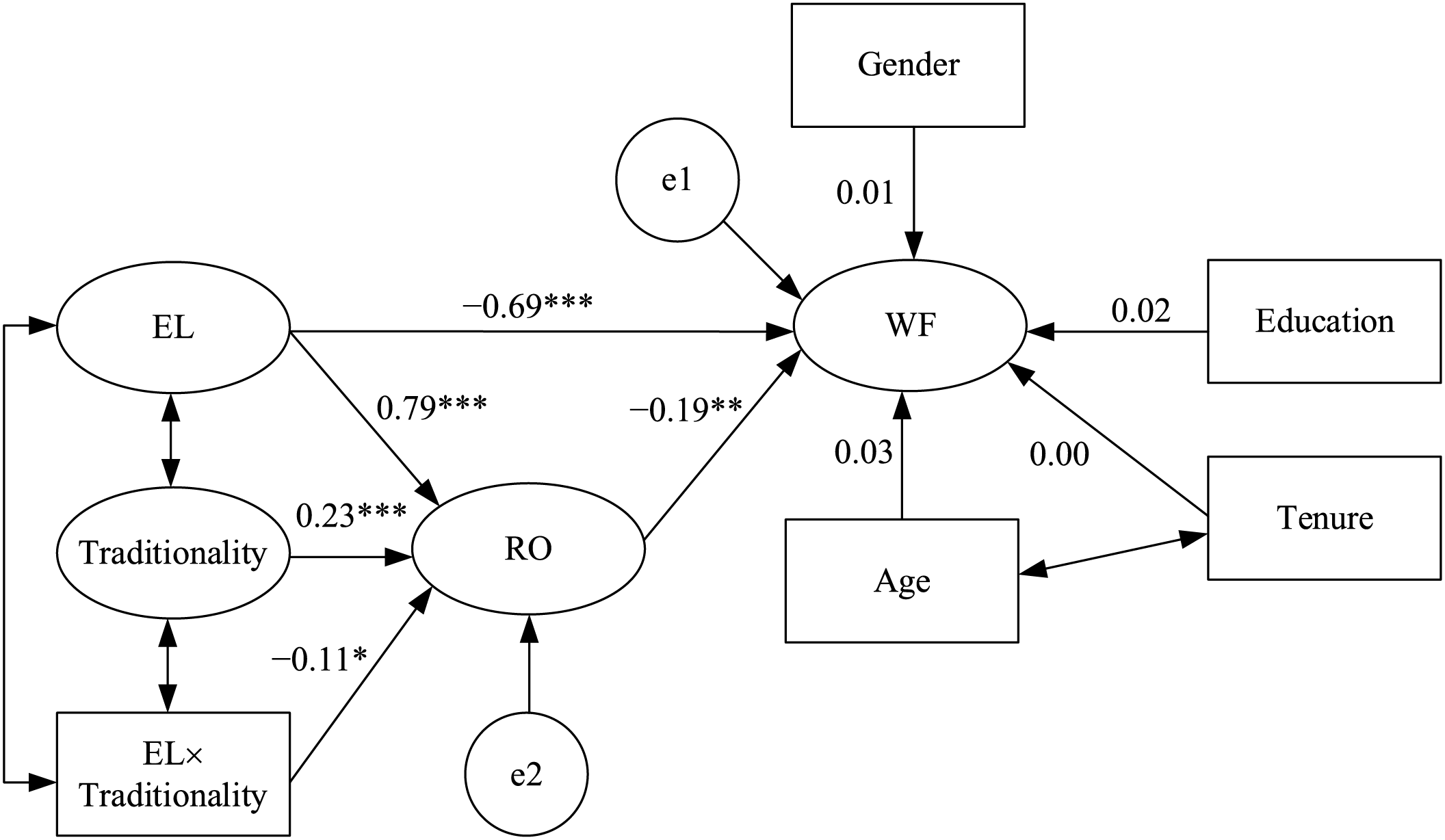

We explored how EL undermines employees’ work-related flow, focusing on the roles of work role overload and traditionalist values. Our specific hypotheses were as follows (see Figure 1 for conceptual model).

Figure 1: The proposed research model

Hypothesis 1. EL has negative effects on employees’ work-related flow.

Hypothesis 2. Employees’ role overload mediates the relationship between EL and employee’s work-related flow, such that higher role overload leads to poorer work-related flow.

Hypothesis 3. Employees’ traditionality moderates the positive relationship between EL and employees’ role overload, such that the positive relationship is weaker when employees’ traditionality is high.

Hypothesis 4. Employees’ traditionality moderates the indirect relationship between EL and employees’ work-related flow via role overload, such that the indirect relationship is weaker when employees’ traditionality is high.

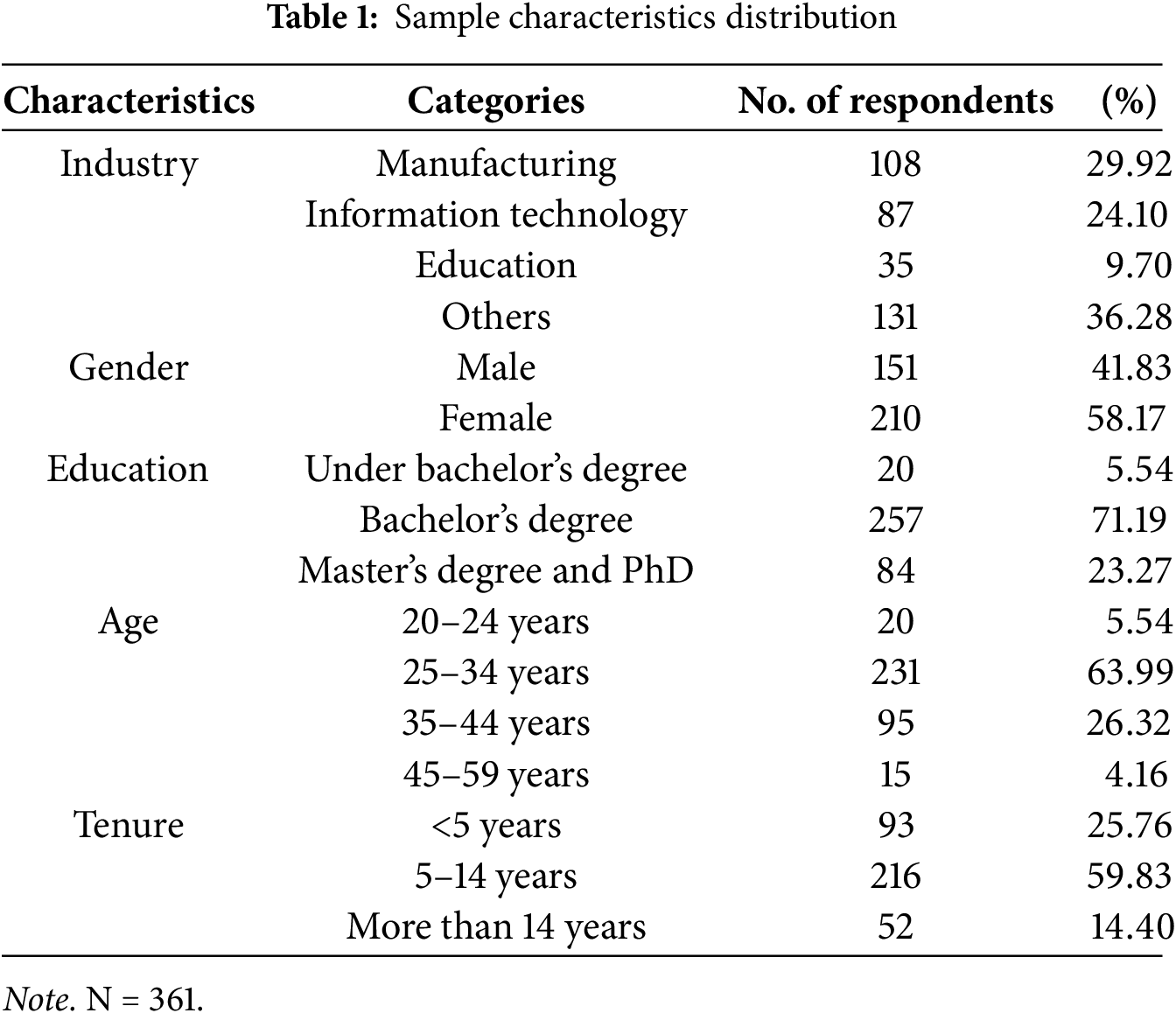

We surveyed 361 employees in China, spanning the manufacturing, information technology, and education industries (see Table 1 for demographics). Of the participants, 41.83% were male. In terms of age, 5.54% were 20–24, 63.99% were 25–34, 26.32% were 35–44, and 4.16% were 45–59. Regarding tenure, 25.76% had under 5 years of experience, 59.83% had between 5 and 14 years, and 14.40% had over 14 years. Additionally, 94.46% held at least a bachelor’s degree.

With the exception of the traditionality measure, all instruments were originally in English; after applying Brislin’s (1976) translation—back translation protocol, we employed validated Chinese versions. All items were evaluated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with participants indicating their level of agreement.

Exploitative leadership. EL was evaluated with a 15-item scale used by Schmid et al. (2019). The EL scale comprises five dimensions, each measured by three items. Example items are “Does not give me opportunities to further develop myself professionally because his or her own goals have priority” and “Uses my work for his or her personal gain”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96.

Traditionality. It was assessed using the five-item scale developed by Farh et al. (1997). Example items are “When people are in dispute, they should ask the most senior person to decide who is right” and “The best way to avoid mistakes is to follow the instructions of senior persons”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

Role overload. It was measured using Bolino and Turnley’s (2005) three-item scale. Example items are “It often seems like I have too much work for one person to do” and “The amount of work I am expected to do is too great”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90.

Work-related flow. It was assessed using the 13-item scale developed by Bakker (2008).

Example items are “When I am working, I think about nothing else” and “I do my work with a lot of enjoyment”. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.94.

Control variables. Referring to previous articles (Bryce & Haworth, 2002; Csikszentmihalyi, 1997; Liu et al., 2023; Sharafi et al., 2006), we controlled for gender, age, education, and tenure in our analyses.

This North China Electric Power University approved the study. Prior to participation, all participants provided informed consent. Data were collected via the online survey platform “Credamo” and administered in two phases. In Wave 1, participants completed a questionnaire covering demographics, EL scale, traditionality scale, and RO scale. Two weeks later, using the platform’s “Targeted Tracking Survey” function, the same participants were asked to complete WF scale.

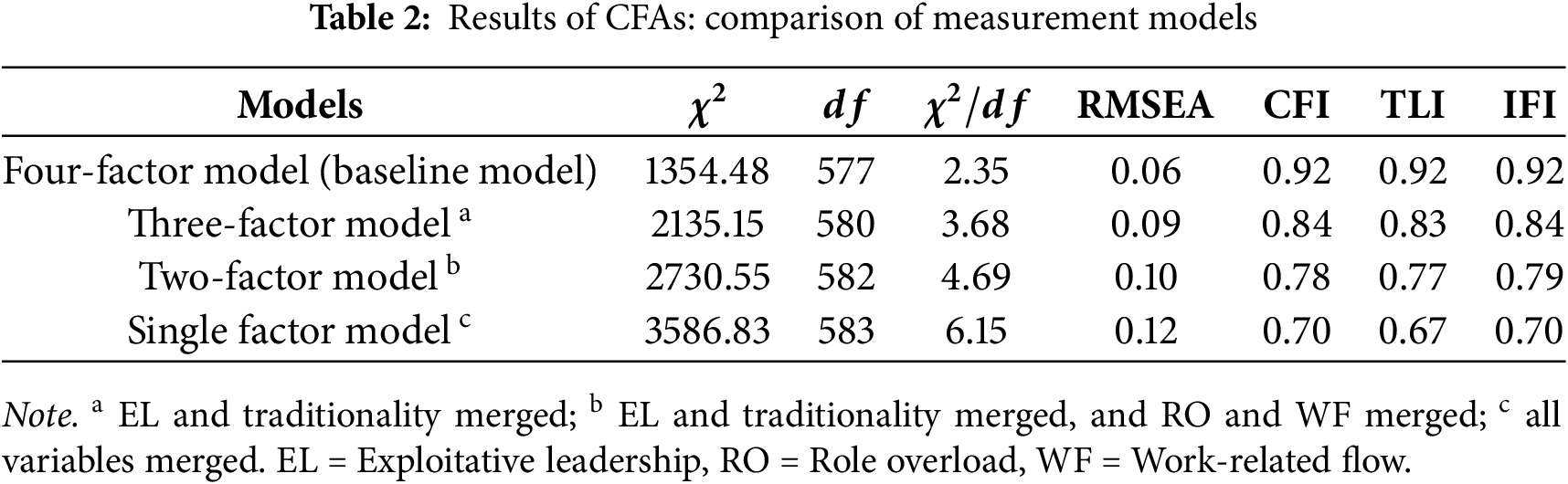

To test the discriminant validity of each construct, this study built four theoretical models (one-factor, two-factor, three-factor, and four-factor) for the main research variables, using confirmatory factor analysis in AMOS 24 to evaluate the discriminant validity of the primary constructs. Table 2 indicates that the four-factor model provides a superior fit to the data compared with the alternative models. This proved that exploitative leadership, traditionality, role overload, and work-related flow were distinct constructs with good discriminant validity.

Since all data originated from a single source, we tested for common method bias (CMB) using the unmeasured latent method factor approach (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Results of CFA showed that five-factor measurement comprising the common method factor and the four focal research variables (

Finally, we employed latent variable structural equation modeling (SEM) to evaluate Hypothesis 1 and applied moderated mediation SEM for Hypotheses 2–4. Furthermore, in AMOS 24, we conducted a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals to assess the significance of the mediating and moderating effects.

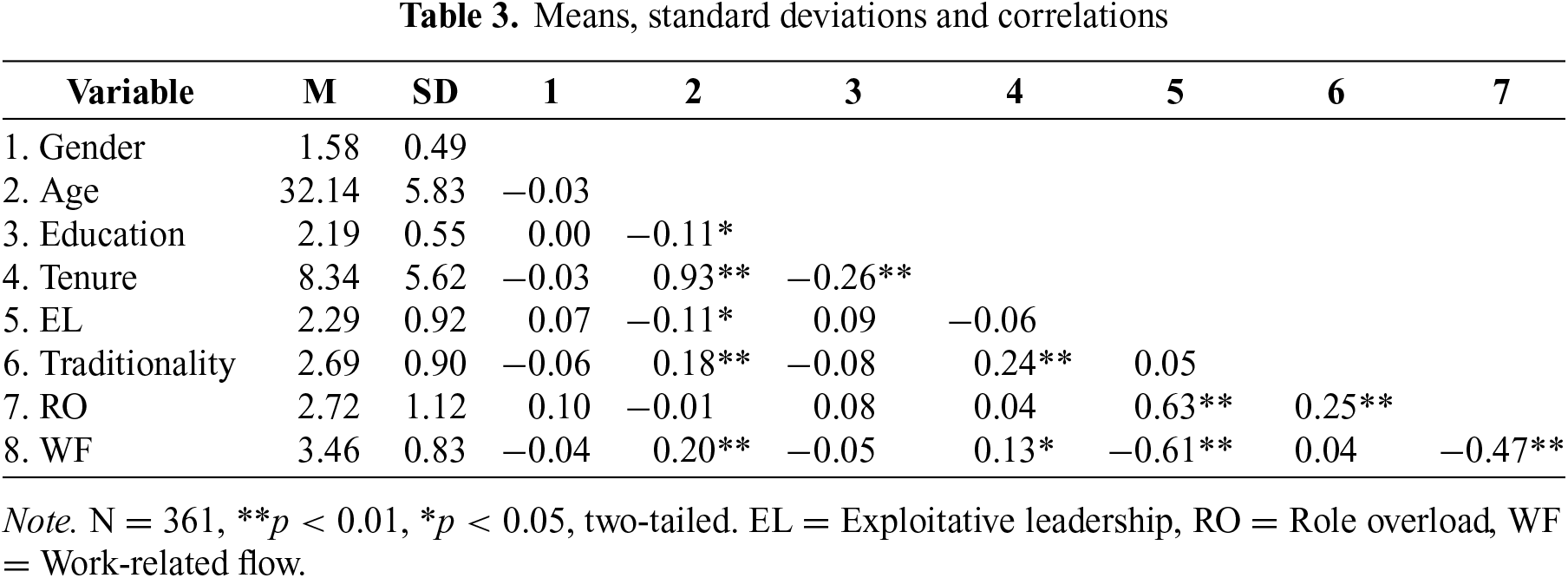

Descriptive statistics and correlational analysis

We computed the means, standard deviations, and correlations of all study variables using SPSS 26.0. As shown in Table 3, EL was positively related to traditionality (r = 0.05, p > 0.05) and RO (r = 0.63, p < 0.01), and negatively related to WF (r = −0.61, p < 0.01). Traditionality was positively associated with RO (r = 0.25, p < 0.01) but had a non-significant association with WF (r = 0.04, p > 0.05), while RO was negatively related to WF (r = −0.47, p < 0.01). These findings provide preliminary support for the hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 stated that EL has a negative effect on WF. To examine this prediction, we estimated a latent variable SEM without mediators or moderators. After adjusting for gender, age, education, and organizational tenure, the model demonstrated an acceptable fit to the data (

To evaluate Hypotheses 2, 3, and 4, we employed a moderated mediation latent variable SEM in AMOS 24. The coefficients were presented in Figure 2. The proposed model exhibited an excellent fit to the data (

Figure 2: The results of the moderated mediating SEM with latent variables. Note. EL = Exploitative leadership, RO = Role overload, WF = Work-related flow, EL × Traditionality = Interaction of exploitative leadership and traditionality; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Hypothesis 2 posited that RO would mediate the EL–WF relationship. The indirect effect was −0.15 (95% CI: [−0.28, −0.03], p < 0.01), confirming this prediction. Because the direct path from EL to WF remained significant (estimate = −0.69, 95% CI: [−0.89, −0.51], p < 0.001) after including RO, the mediation is partial—thereby supporting Hypothesis 2.

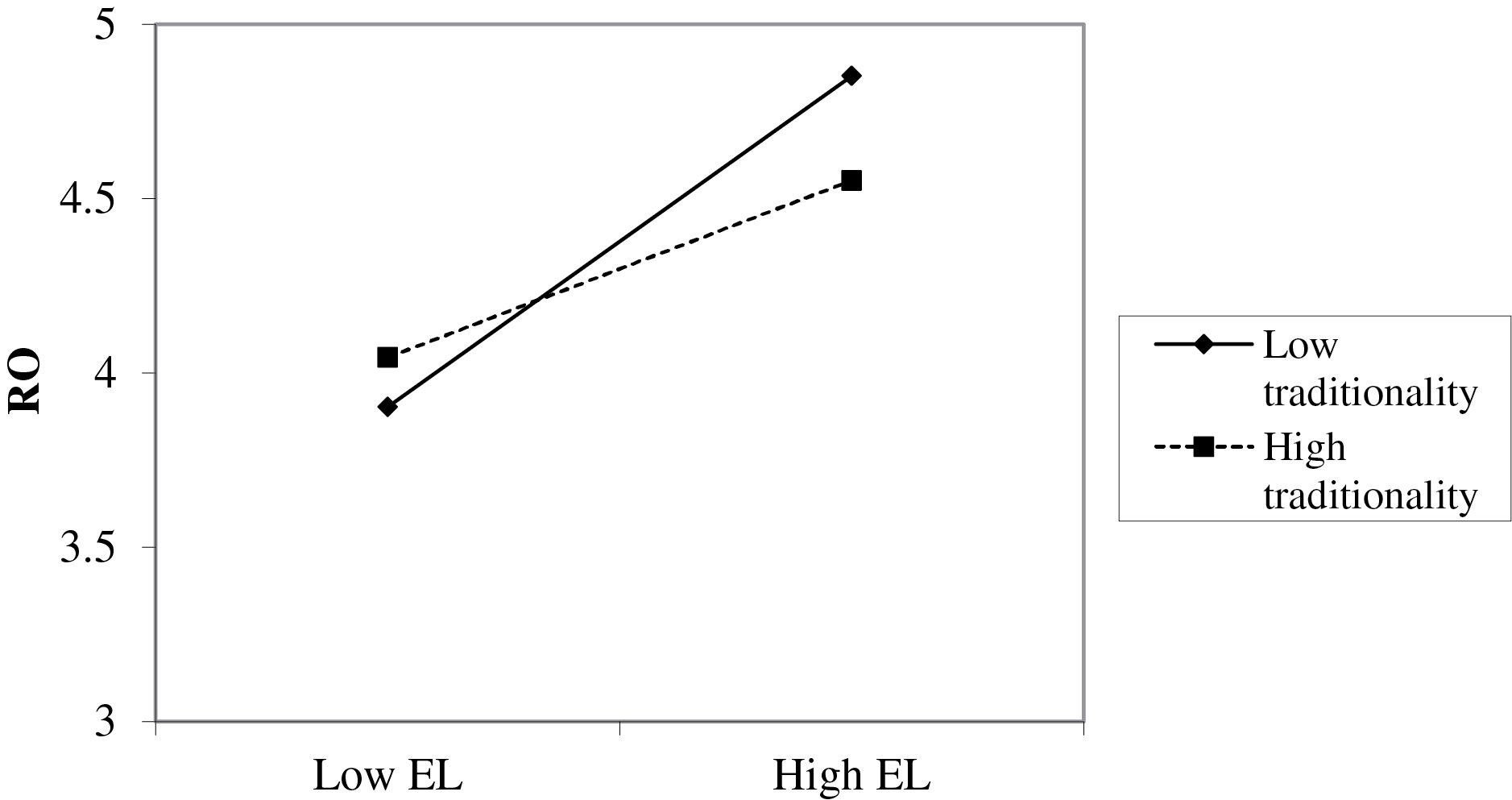

Hypothesis 3 proposed that traditionality would attenuate the positive relationship between EL and RO. Consistent with this, the EL × traditionality interaction was significant (β = –0.11, 95% CI [–0.22, –0.01], p < 0.05). As shown in Figure 3, at low traditionality (M − SD), EL had a robust positive effect on RO (estimate = 0.60, 95% CI [0.35, 0.81], p < 0.001), whereas at high traditionality (M + SD) the effect was non-significant (estimate = 0.40, 95% CI [–0.03, 0.78], p > 0.05). The difference between these estimates was significant (difference = 0.19, 95% CI [0.02, 0.39], p < 0.05), thereby supporting Hypothesis 3.

Figure 3: The interaction plot of EL and traditionality on RO. Note. EL = Exploitative leadership, RO = Role overload

Hypothesis 4 posited that traditionality intensifies the indirect impact of EL on WF via RO. The moderated indirect effect was 0.02 (95% CI [0.001, 0.06], p < 0.05). Specifically, at low traditionality (M − SD), the indirect effect was −0.11 (95% CI [−0.22, −0.03], p < 0.01), and at high traditionality (M + SD), the indirect effect was −0.08 (95% CI [−0.20, −0.01], p < 0.05). The difference between these estimates was significant (difference estimate = −0.04, 95% CI [−0.11, −0.002], p < 0.05), thereby supporting Hypothesis 4.

First, exploitative leadership was harmful to and employees’ work-related flow. Previous studies have mainly examined how hindrance job demands (Van Oortmerssen et al., 2020) and individual characteristics (e.g., neuroticism) (Bakker et al., 2019) negatively affect flow, with limited emphasis on the connection between leadership and employees’ flow. While scholars have found that transformational leadership or empowerment behaviors improve employees’ flow (Park et al., 2021), given that negative leadership typically exerts a stronger influence on employees (Lyu et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2021), this study bridges the literature gap regarding the link between negative leadership and work-related flow.

Second, the mediating effect of role overload explains how exploitative leadership hampers employees’ work-related flow. When employees face exploitative leadership, their role tasks and job demands increase, forcing them to take on more tasks within limited time, thereby intensifying role overload (Bolino & Turnley, 2005; Wang & Ding, 2024). This can be explained by the fact that exploitative leadership causes severe resource loss for employees. Employees are particularly sensitive to the loss of individual resources, especially behavioral resources, making it difficult for them to recover from the spiral of resource depletion (Guo et al., 2021) and leading them to perceive themselves as unable to balance multiple role tasks. The perception of resource loss compels employees to conserve their existing resources, leaving insufficient resources to experience flow—a short-term peak state requiring substantial energy and cognitive resources (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997). Prior studies on exploitative leadership’s impact mainly emphasize emotional dimensions (Guo et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021), with little focus on cognitive mechanisms (Cheng et al., 2021). Through COR theory, we establish that role overload serves as a crucial cognitive mechanism connecting exploitative leadership and flow.

Third, we found that employees’ traditionality influences the indirect relationship between EL and work-related flow via role overload. Traditionality functions as a boundary condition influencing employees’ flow by shaping employees’ cognition and compliance-related behaviors (Cheng et al., 2023; Farh et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2024), whereas those low in traditionality are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of EL (Cheng et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021).

This study provides organizations with a range of actionable insights. First, organizations should carefully screen candidates for dark personality traits associated with exploitative leadership (e.g., Machiavellianism, psychopathy) during selection process to control and reduce exploitative leadership from the outset (Lazreg & Lakhal, 2022). In addition, organizations should implement periodic positive leadership development programs to cultivate ethical and employee-centered leadership behaviors. Second, organizations should establish open grievance mechanisms to ensure employees have accessible channels to report exploitative leadership behaviors that harm them (Remišová et al., 2019). A “zero-tolerance” approach towards such behaviors is essential. Evidence from this and previous research indicates that employees with lower traditionality are especially susceptible to exploitative leadership (Wu et al., 2021), so organizations should promptly address complaints from such employees, treating them as critical “signals”, and take action to prevent prolonged exploitation and role overload, thereby mitigating potential severe outcomes. Third, since flow occurs when challenges and skills are balanced (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 2014), organizations should implement professional training programs to enhance employees’ abilities, reducing anxiety stemming from skill inadequacy and enabling better flow experiences. And high expectations and complex tasks can serve as challenging work demands (Bakker et al., 2023) that encourage employees’ self-development and growth by addressing their competency needs (Ilies et al., 2017), promoting flow (Van Oortmerssen et al., 2020). Organizations can foster employees’ flow by offering supportive resources, setting clear goals, providing explicit feedback, helping employees to identify and develop their strengths (Liu et al., 2022), creating concentration-friendly environments, and minimizing unnecessary bureaucratic processes.

Limitations and directions for future research

Although this research offers valuable insights, it inevitably entails certain limitations. First, because the research was carried out in China, its results may not be applicable to other cultural contexts. Second, the study employed a cross-sectional design, ignoring potential temporal variations in the transmission of variable effects and failing to capture dynamic processes. Consequently, causal relationships cannot be inferred. Future studies might adopt longitudinal designs to validate causal links in this theoretical framework. Third, our exclusive use of self-reported measures may have introduced common method bias. Future research might leverage diverse data sources—for example, matching leader and employee responses—to bolster the objectivity and reliability of the results.

Exploitative leadership undermined employees’ work-related flow, with role overload acting as a partial mediator. Employees’ traditionality weakened both the direct impact of exploitative leadership on role overload and its indirect effect on flow via role overload—meaning that higher traditionality buffered the adverse consequences on flow. This study contributes by uncovering new antecedents of work-related flow and clarifying how cultural values shape boundary conditions in Chinese work contexts. Practically, organizations should incorporate assessments for exploitative leadership tendencies into their hiring processes to minimize its detrimental effects on employees’ flow in the workplace.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the employees who participated in this study. The manuscript has not been submitted elsewhere for publication, in whole or in part.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lingnan Kong, Shunkun Yu; data collection: Lingnan Kong, Ruiqi Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Lingnan Kong, Nuo Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Lingnan Kong, Ruiqi Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data for this study is available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Participants were assured of the voluntary nature of the study and the confidentiality of the data provided. North China Electric Power University approved the study.

Informed Consent: Participants were appropriately informed of the purpose and procedures of the study, and their informed consent was obtained before participating in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Akhtar, M. W., Huo, C., Syed, F., Safdar, M. A., Rasool, A. et al. (2022). Carrot and stick approach: The exploitative leadership and absenteeism in education sector. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 890064. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.890064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Akram, Z., Chaudhary, S., Akram, U., & Han, H. (2024). How leaders exploited the frontline hospitality employees through distress and service sabotage? Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 41(2), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2024.2309182 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bacharach, S. B., Bamberger, P., & Conley, S. C. (1990). Work processes, role conflict, and role overload: The case of nurses and engineers in the public sector. Work and Occupations, 17(2), 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888490017002004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bajaba, A., Bajaba, S., & Alsabban, A. (2023). Exploitative leadership and constructive voice: The role of employee adaptive personality and organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 10(4), 601–623. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-07-2022-0218 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B. (2008). The work-related flow inventory: Construction and initial validation of the WOLF. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(3), 400–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.11.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. (2023). Job demands-resources theory: Ten years later. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-053933 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., Hetland, J., Olsen, O. K., & Espevik, R. (2019). Daily strengths use and employee well-being: The moderating role of personality. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(1), 144–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12243 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2005). The personal costs of citizenship behavior: The relationship between individual initiative and role overload, job stress, and work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 740. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Brislin, R. W. (1976). Comparative research methodology: Cross-cultural studies. International Journal of Psychology, 11(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207597608247359 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bryce, J., & Haworth, J. (2002). Wellbeing and flow in sample of male and female office workers. Leisure Studies, 21(3–4), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/0261436021000030687 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cheng, B., Dong, Y., Kong, Y., Shaalan, A., & Tourky, M. (2023). When and how does leader humor promote customer-oriented organizational citizenship behavior in hotel employees? Tourism Management, 96(1), 104693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104693 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cheng, K., Guo, L., & Luo, J. (2021). The more you exploit, the more expedient I will be: A moral disengagement and Chinese traditionality examination of exploitative leadership and employee expediency. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 40(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-021-09781-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cheng, K., Wei, F., & Lin, Y. (2019). The trickle-down effect of responsible leadership on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Research, 102(5), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.04.044 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Csikszentmihalhi, M. (2020). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. UK: Hachette. [Google Scholar]

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and creativity. Namta Journal, 22(2), 60–97. [Google Scholar]

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Happiness, flow, and economic equality. American Psychologist, 55(10), 1163–1164. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.10.1163 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Larson, R. (2014). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (vol. 10). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Dawson, K. M., O’Brien, K. E., & Beehr, T. A. (2016). The role of hindrance stressors in the job demand–control–support model of occupational stress: A proposed theory revision. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(3), 397–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2049 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Demerouti, E. (2006). Job characteristics, flow, and performance: The moderating role of conscientiousness. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(3), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.11.3.266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ding, H., Yu, E., & Li, Y. (2020). Core self-evaluation, perceived organizational support for strengths use and job performance: Testing a mediation model. Current Psychology, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Ding, H., Yu, E., & Li, Y. (2022). Exploring the relationship between core self-evaluation and employee innovative behaviour: The role of emotional factors. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 32(5), 474–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2022.2120700 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Farh, J.-L., Earley, P. C., & Lin, S.-C. (1997). Impetus for action: A cultural analysis of justice and organizational citizenship behavior in Chinese society. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 421–444. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393733 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Farh, J.-L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50(3), 715–729. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.25530866 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fredrickson, B. L. (2011). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Guan, P., Capezio, A., Restubog, S. L. D., Read, S., Lajom, J. A. L. et al. (2016). The role of traditionality in the relationships among parental support, career decision-making self-efficacy and career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.02.018 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guo, L., Cheng, K., & Luo, J. (2021). The effect of exploitative leadership on knowledge hiding: A conservation of resources perspective. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-03-2020-0085 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J.-P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E., Stevens, N. R., & Zalta, A. K. (2015). Expanding the science of resilience: Conserving resources in the aid of adaptation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(2), 174–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1002377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ilies, R., Wagner, D., Wilson, K., Ceja, L., Johnson, M. et al. (2017). Flow at work and basic psychological needs: Effects on well-being. Applied Psychology, 66(1), 3–24. [Google Scholar]

Ji, L., Ye, Y., & Deng, X. (2022). From shared leadership to proactive customer service performance: A multilevel investigation. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(11), 3944–3961. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2021-1077 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lan, J., Wong, C.-S., Jiang, C., & Mao, Y. (2017). The effect of leadership on work-related flow: A moderated mediation model. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38(2), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-08-2015-0180 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lazreg, C., & Lakhal, L. (2022). The downside of managers: The moderator role of political skill & deceptive situation. Acta Psychologica, 228, 103619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Liu, J., Kwong Kwan, H., Wu, L., & Wu, W. (2010). Abusive supervision and subordinate supervisor-directed deviance: The moderating role of traditional values and the mediating role of revenge cognitions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 835–856. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317909x485216 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, W., Lu, H., Li, P., Van Der Linden, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2023). Antecedents and outcomes of work-related flow: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 144(2), 103891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2023.103891 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu W., van der Linden D., & Bakker A. B. (2022). Strengths use and work-related flow: An experience sampling study on implications for risk taking and attentional behaviors. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 37(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-07-2020-0403 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lyu, Y., Zhou, X., Li, W., Wan, J., Zhang, J. et al. (2016). The impact of abusive supervision on service employees’ proactive customer service performance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(9), 1992–2012. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2015-0128 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Majeed, M., & Fatima, T. (2020). Impact of exploitative leadership on psychological distress: A study of nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1713–1724. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Matthews, R. A., Winkel, D. E., & Wayne, J. H. (2014). A longitudinal examination of role overload and work–family conflict: The mediating role of interdomain transitions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 72–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1855 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moin, M. F., Omar, M. K., Ali, A., Rasheed, M. I., & Abdelmotaleb, M. (2024). A moderated mediation model of knowledge hiding. The Service Industries Journal, 44(5–6), 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2022.2112180 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nielsen, K., & Cleal, B. (2010). Predicting flow at work: Investigating the activities and job characteristics that predict flow states at work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(2), 180. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Park, I.-J., Doan, T., Zhu, D., & Kim, P. B. (2021). How do empowered employees engage in voice behaviors? A moderated mediation model based on work-related flow and supervisors’ emotional expression spin. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 95(5), 102878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102878 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peng, H., & Wei, F. (2020). How and when does leader behavioral integrity influence employee voice? The roles of team independence climate and corporate ethical values. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(3), 505–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04114-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Remišová, A., Lašáková, A., & Kirchmayer, Z. (2019). Influence of formal ethics program components on managerial ethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 160, 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3832-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schermuly, C. C., & Meyer, B. (2020). Transformational leadership, psychological empowerment, and flow at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(5), 740–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1749050 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schmid, E. A., Pircher Verdorfer, A., & Peus, C. V. (2018). Different shades—different effects? Consequences of different types of destructive leadership. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Schmid, E. A., Verdorfer, A. P., & Peus, C. (2019). Shedding light on leaders’ self-interest: Theory and measurement of exploitative leadership. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1401–1433. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063177078 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schmitt, A., Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2016). Transformational leadership and proactive work behaviour: A moderated mediation model including work engagement and job strain. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(3), 588–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12143 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sharafi, P., Hedman, L., & Montgomery, H. (2006). Using information technology: Engagement modes, flow experience, and personality orientations. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(5), 899–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.03.022 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun, Z., Wu, L.-Z., Ye, Y., & Kwan, H. K. (2023). The impact of exploitative leadership on hospitality employees’ proactive customer service performance: A self-determination perspective. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijchm-11-2021-1417 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Syed, F., Naseer, S., Akhtar, M. W., Husnain, M., & Kashif, M. (2021). Frogs in boiling water: A moderated-mediation model of exploitative leadership, fear of negative evaluation and knowledge hiding behaviors. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25(8), 2067–2087. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2019-0611 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Oortmerssen, L. A., Caniëls, M. C., & van Assen, M. F., (2020). Coping with work stressors and paving the way for flow: Challenge and hindrance demands, humor, and cynicism. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(6), 2257–2277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00177-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Z., Chen, Y., Ren, S., Collins, N., Cai, S. et al. (2023a). Exploitative leadership and employee innovative behaviour in China: A moderated mediation framework. Asia Pacific Business Review, 29(3), 570–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2021.1990588 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, F., & Ding, H. (2024). Core self-evaluation and work engagement: Employee strengths use as a mediator and role overload as a moderator. Current Psychology, 43(19), 17614–17624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05687-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, H., & Li, Y. (2021). Role overload and Chinese nurses’ satisfaction with work-family balance: The role of negative emotions and core self-evaluations. Current Psychology, 40(11), 5515–5525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00494-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Y.-Q., Long, L.-R., & Zhou, H. (2012). Organizational injustice perception and workplace deviance: Mechanisms of negative emotion and traditionality. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44, 1663–1676. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2012.01663 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Z., Ren, S., Chadee, D., & Chen, Y. (2024). Employee ethical silence under exploitative leadership: The roles of work meaningfulness and moral potency. Journal of Business Ethics, 190(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05405-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Z., Sun, C., & Cai, S. (2021). How exploitative leadership influences employee innovative behavior: The mediating role of relational attachment and moderating role of high-performance work systems. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(2), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-05-2020-0203 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, C., Zhang, Y., & Feng, J. (2023b). Is it fair? How and when exploitative leadership impacts employees’ knowledge sharing. Management Decision, 61(11), 3295–3315. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-09-2022-1289 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Williams, L. J., Cote, J. A., & Buckley, M. R. (1989). Lack of method variance in self-reported affect and perceptions at work: Reality or artifact? Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(3), 462. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.3.462 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, L.-Z., Sun, Z., Ye, Y., Kwan, H. K., & Yang, M. (2021). The impact of exploitative leadership on frontline hospitality employees’ service performance: A social exchange perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 96(2), 102954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102954 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.11.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, K.-S. (2003). Methodological and theoretical issues on psychological traditionality and modernity research in an Asian society: In response to Kwang-Kuo Hwang and beyond. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 6(3), 263–285. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-839x.2003.00126.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ye, Y., Chen, M., Wu, L.-Z., & Kwan, H. K. (2023). Why do they slack off in teamwork? Understanding frontline hospitality employees’ social loafing when faced with exploitative leadership. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 109(1), 103420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103420 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhao, H., Chen, Y., Zhao, S., & Wang, B. (2024). Green inclusive leadership and hospitality employees’ green service innovative behavior in the Chinese hospitality context: The roles of basic psychological needs and employee traditionality. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 123(7), 103922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2024.103922 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools