Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Acculturation and health of international students in China: How cultural values and personality traits influence their attitudes and experience

1 Department of Psychology, School of Philosophy and Sociology, Jilin University, Changchun, 130012, China

2 The Tourism College of Changchun University, Changchun, 130000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yanyan Zhang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 385-392. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068041

Received 07 March 2025; Accepted 13 April 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the political, economic, social, and cultural environment perceptions on international students that define their acculturation and health related quality of life. Participants were 117 international students from 32 countries attending a Chinese university (females = 43%, mean age = 21.17 years, SD = 4.45 years). They reported on their acculturation to China and physical and psychological well-being. Results from t-tests and correlation analyses indicate political liberals had more positive attitudes toward China than the conservatives, and higher self-reported physical and psychological results. Higher scores on the “interdependence” dimension of self-construal, as well as the “extraversion” and “emotional stability” dimensions of personality traits, were associated with more positive views of China and better health outcomes. These findings are consistent with Berry’s framework for acculturation, which posits that individual-level variables are related to cultural adaptation, and that cultural adaptation is associated with improved physical and mental health. International student offices at host universities should implement comprehensive support programs, including language assistance, cultural orientation, and social integration initiatives to effectively enhance the health related quality of life of international students.Keywords

The international student market is one of the fastest-growing sectors, particularly in countries such as Australia, China, the European Union, and North America. Settling in their host countries, international students must make various adjustments to manage their everyday lives—a process known as acculturation. Acculturation refers to changes in cultural practices, values, and identities that occur when individuals encounter unfamiliar cultures (Berry and John, 2006; Gibson, 2001). Most studies have examined international students’ acculturation in North America (e.g., Zander, 2008), while researchers have paid little attention to non-Western host cultures with different cultural orientations (Schwartz et al., 2010). As Schwartz et al. (2010, p. 242) noted, “some caution should be taken when generalizing patterns of acculturation observed in the United States to other countries of settlement.” This study seeks to address this gap in the literature by focusing particularly on East Asian countries, with a specific emphasis on China.

Berry (1997) proposed a fourfold theory to describe the different strategies people use for acculturation, namely, assimilation (acceptance of the host culture and rejection of the original culture), separation (rejection of the host culture and retention of the heritage culture), integration (acceptance of both cultures), and marginalization (rejection of both cultures). Among the four types of acculturation, integration was frequently found to be linked to the most favorable psychosocial outcomes (e.g., high self-esteem, high life satisfaction, low stress, anxiety, and depression). David et al. (2009) studied bicultural individuals (often referred to as the integration type; Benet-Martínez & Haritatos, 2005) and reported a moderate relationship between a high level of acculturation and low levels of various types of psychological stress. As the acculturation level increased, bicultural individuals also reported a higher level of life satisfaction.

Health-related outcomes. Acculturation outcomes depend on “cultural orientation”, which is the relative emphasis society places on the values of individualism and collectivism (Hofstede, 1980). Specifically, a culture whose members stress group and community goals over individual interests is considered a collectivistic culture. In contrast, a culture that values individual independence, personal rights, and self-actualization is considered an individualistic culture. Researchers further linked the concept of individualism-collectivism to the manner in which individuals conceive of themselves—that is, to self-construal (Markus & Kitayama, 2014). Members of individualistic and collectivistic cultures tend to have independent and interdependent “selves,”, respectively. In individualistic cultures (e.g., North American culture, including the U.S. and Canada), people consider themselves separate units, with each person representing a unique part of society. In collectivist cultures (e.g., East Asian cultures, including Korea, Japan, and China), however, people are integrated into groups (e.g., family and community), and the members of groups depend on one another. Therefore, minorities (e.g., immigrants and international students) may enter and change in different ways in Eastern vs. Western cultural contexts.

Acculturation outcomes include health-related well-being (Diaz, 2005). Acculturation not only influences individuals’ physical well-being (e.g., smoking acquisition, obesity, and breastfeeding) but also has significant impacts on their mental health (e.g., stress and depression) (Kodippili et al., 2024; Raval et al., 2025; Rosenthal, 2018).

The Chinese university context and international student services

Compared with other immigrants, international students are regarded as ideal migrants and possess a competitive advantage in the global knowledge economy (King & Raghuram, 2013; Riaño et al., 2018). While Chinese students studying abroad in other countries have been extensively researched, the phenomenon of international students moving against the flow to study in China is still considered relatively new (Lee, 2019). Largely due to the advent of globalization and the flourishing economy, China has become a destination country for international immigrants in the present century. It attracts great numbers of people from a variety of countries in search of jobs, education, and new lives (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2011). In the field of education, China has gradually begun to shift from being a supplier of international education to becoming a recipient. The country aims to attract international students and establish itself as an international education hub (Liu & Lin, 2016). To achieve this goal, the Chinese government has implemented various incentive programs, which have contributed to making China one of the largest study destinations in Asia in recent years (Gao & Hua, 2021). With the implementation of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the proportion of international students coming to China is expected to continue rising in the foreseeable future (Ma & Zhao, 2018). Moreover, several challenges are associated with the education of international students in China. For instance, the proportion of courses taught in English is relatively low, and some regulations and policies have not been updated in a timely manner (Ma & Zhao, 2018). These challenges may collectively contribute to cultural adaptation difficulties faced by international students in China. Therefore, exploring the cultural adaptation of international students in this context can provide guidance for policymakers aimed at improving the quality of life for these students.

This study aims to explore the lived experiences of international students in China, a country characterized by a collectivistic cultural orientation, with a focus on their acculturation (i.e., cultural identification and attitudes toward China) and health-related outcomes. We are also interested in studying the roles of cultural values and personality traits in these international students’ life adjustment. Our specific research hypotheses were.

Specifically, we hypothesized:

Hypothesis 1. As the level of education and the length of stay in China increased, international students would be more acculturated in the Chinese culture (identifying more with the Chinese culture and having more positive attitudes toward China).

Hypothesis 2. International students who identify more with the Chinese culture, have better physical and psychological health.

Hypothesis 3. International students who scored higher on collectivism (and lower on individualism) would identify more with the Chinese culture, which in turn would result in more positive attitudes toward China and better physical and psychological outcomes.

Hypothesis 4. International students who scored higher on openness, extroversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability would identify more with the Chinese culture, which in turn would result in better physical and psychological outcomes.

The sample consisted of 117 international students from 32 countries (57% male; 59% from Asia, 15% from Africa, 10% from North America, 5% from Europe, and 11% from other regions). Participants were recruited from three major universities located in northern China. They were offered course credit in exchange for participating in the study. The mean age was 21.17 years (SD = 4.45). All participants completed the survey using paper-and-pencil questionnaires.

Demographics. The participants indicated their age, sex, nationality, class year, grown-up place (city or countryside), length of stay in China, political attitude and religious belief.

Cultural Values. The Self-Construal Scale (SCS; Singelis, 1994) was used as a measure of cultural orientations. It contains 24 items assessing the independent self-construal (e.g., I enjoy being unique and different from others in many respects) and the interdependent self-construal (e.g., My happiness depends on the happiness of those around me). Items are on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 6 = Strongly agree). The SCS Cronbach’s alpha scores were 0.82 and 0.79 for “Independence” and “Interdependence” self-construal, respectively.

Personality Traits. The Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) (Gosling et al., 2003) comprises 10 items assessing five personality traits (openness to experience, emotional stability, agreeableness, extroversion, and conscientiousness). Items are on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree). The TIPI Cronbach’s alpha scores ranged from 0.60 to 0.85 for each of the five dimensions.

Cultural Identification. We adopted the Abbreviated Multidimensional Acculturation Scale (AMAS–ZABB; Zea et al., 2003), a 21-item measure of identification of the Chinese culture by cultural identity, language and cultural competence. The 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) was used in this study. The overall Cronbach’s alpha for AMAS–ZABB scores was 0.73.

Attitudes toward China. We asked the students to evaluate the economic, political, religious, social and cultural environment of China using a five-point Likert scale. A higher mean score indicated a more positive attitude toward China. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 in the current study. We also included six open-ended questions to examine international students’ life experience in China by asking them to list three things they like the MOST and the LEAST about China.

Physical and Psychological Well-being. The RAND 36-Item Health Survey (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992) comprizes eight dimensions of health: physical functioning, social functioning, physical problem, emotional problem, mental health, vitality, pain and general health perception. In the current study, we mainly focused on the physical and emotional problems of international students. The physical problem dimension included four items and the emotional problem dimension included three items (Cronbach’s alphas were 0.71 and 0.74, respectively). Higher scores indicated less physical and psychological problems and better health perceptions (A general health perception and a perception of health change before and after their visits of China were also measured).

We used SPSS version 27.0 for data analysis. First, descriptive statistics were conducted to gain an overall understanding of the data. Subsequently, we employed t-tests and correlation analyses to test our hypotheses. Finally, we performed an exploratory analysis of open-ended questions to examine international students’ perceptions of China.

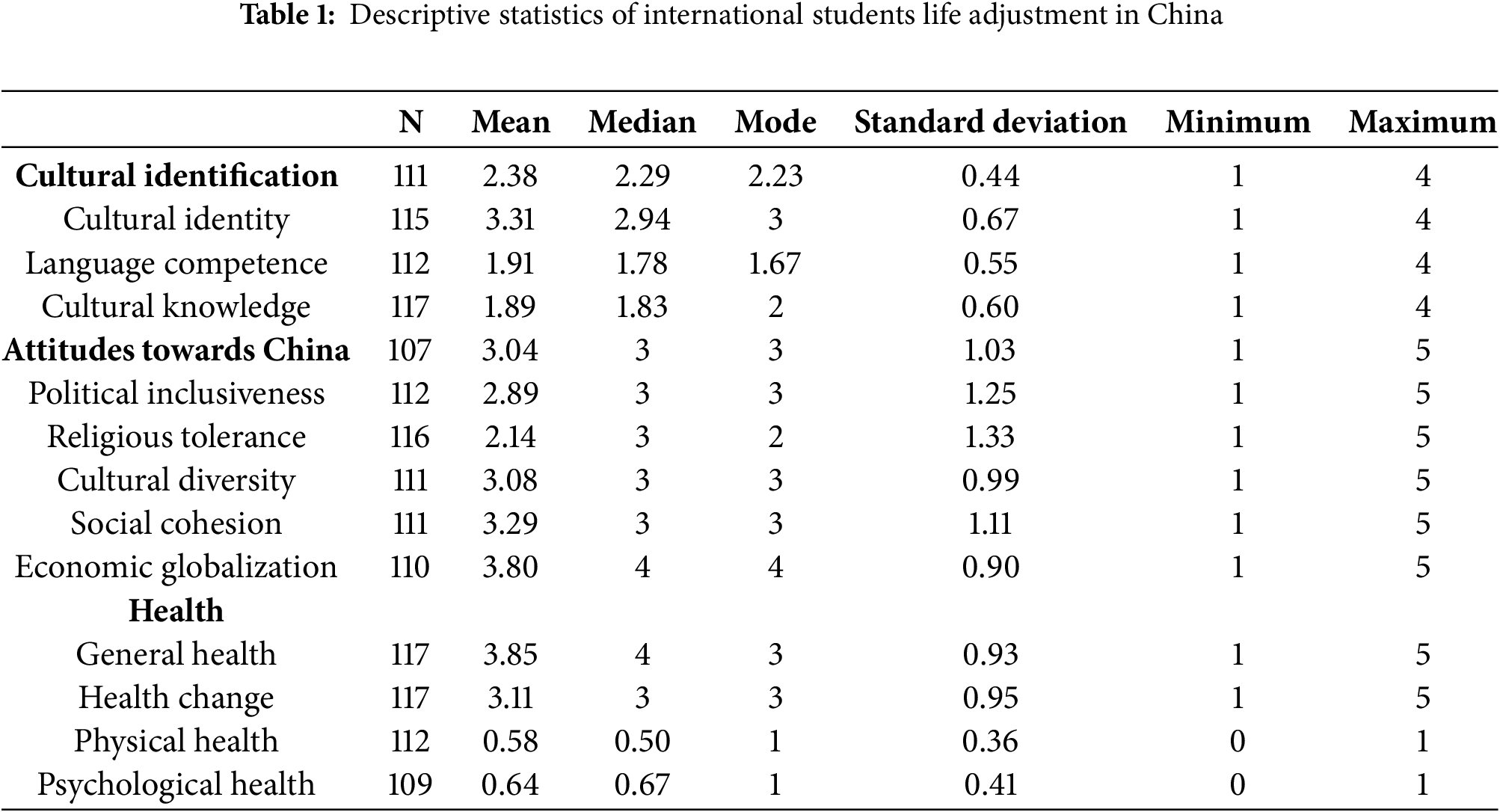

We first evaluated international students’ cultural adjustment by calculating the means of acculturation (cultural identification and attitudes toward China) and health-related outcomes. Results indicated that overall, international students had positive attitudes toward China (Mean = 3.04, SD = 1.03) and good health (Mean = 3.85, SD = 0.93 for General Health; Mean = 3.11, SD = 0.95 for Health Change), although they did not identify a lot with the Chinese culture, particularly regarding language competence and cultural knowledge (Mean = 1.91, SD = 0.55 for Language Competence; Mean = 1.89, SD = 0.60 for Cultural Knowledge). Among the five dimensions of attitudes toward China, international students had the most positive attitude toward the “Economic Globalization” of China (Mean = 3.80, SD = 0.90), followed by “Social Cohesion” (Mean = 3.29, SD = 1.11), “Cultural Diversity” (Mean = 3.08, SD = 0.99), and “Political Inclusiveness” (Mean = 2.89, SD = 1.25). International students had the least positive attitude toward the “Religious Tolerance”, but their opinions largely varied at the individual level (Mean = 2.14, SD = 1.33; see Table 1 for details). For the purpose of parsimony, we focused on the overall level of cultural identification and attitudes toward China, as well as the physical and psychological health in the following analyses.

Relationship between Demographic Variables and Acculturation. To test hypothesis 1), independent samples t-tests were used to examine the effects of sex, age, grown-up place, length of stay, level of education, political attitude, and religious belief on international students’ acculturation (i.e., cultural identification and attitudes toward China). As expected, none of the sex, age, and grown-up place effects on acculturation was found. Consisting with the hypothesis, length of stay and level of education predicted both international students’ cultural identification and their attitudes toward China.

Compared to those who had stayed in China for less than one-year, international students who had been in China for more than one year identified more with the Chinese culture and had more positive attitudes toward China (t = 3.07, p < 0.01 for identification; t = 4.87, p < 0.001 for attitudes). Graduate students identified more with the Chinese culutre and had more positive attitudes toward China than undergraduate students (t = 3.45, p < 0.01 for identification; t = 1.72, p = 0.08, marginally significant for attitudes). Partially supporting the hypothesis, political orientation predicted students’ attitudes toward China but not cultural identification, with the political liberals having more positive views of China than the political conservatives (t = 0.95, ns. for identification; t = 2.41, p < 0.05 for attitudes). Contrary to hypothesis 1), religion was not a predictor for cultural identification or attitudes toward China (see Table 2 for details).

Relationship between Acculturation and Health. To test hypothesis 2), we correlated cultural identification with attitudes toward China and students’ physical and psychological health. Results indicated a strong positive correlation between cultural identification and attitudes toward China (r = 0.38, p < 0.001). It showed that as international students identified more with the Chinese culture, they self-reported better physical and psychological well-being (r = 0.22, p < 0.05 for physical health; r = 0.18, p = 0.06, marginally significant for psychological health). Contrary to hypothesis 2), however, cultural identification did not correlate with students’ physical and psychological health directly (see Table 3 for details).

Relationship between Cultural Orientations and Acculturation, Health. To test hypothesis 3), we correlated cultural values (i.e., independence vs. interdependence self-construal, after controlling for the other cultural orientation) with international students’ cultural identification, attitudes toward China, and health. Partially supporting the hypothesis, interdependence, but not independence self-construal, significantly correlated with international students’ attitudes toward China and their physical and psychological health (r = 0.19, p < 0.05 for attitudes; r = 0.22, p < 0.05 for physical health; r = 0.20, p < 0.05 for psychological health). It indicated that as international students scored higher on the interdependence dimension of self-construal, they had more positive attitudes toward China and better health-related outcomes (see Table 4 for details).

Relationship between Personality Traits and Acculturation, Health. To test hypothesis 4), we correlated personality traits (i.e., openness to experience, extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness and emotional stability) with international students’ cultural identification, attitudes toward China, and health. As expected, all personality traits (except for conscientiousness) were significantly related to international students’ attitudes toward China. That is, as students scored higher on openness, extroversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability, they had more positive attitudes toward China (r = 0.21, p < 0.05 for openness; r = 0.19, p < 0.05 for extroversion; r = 0.27, p < 0.01 for agreeableness; r = 0.24, p < 0.05 emotional stability). In addition, extroversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability were positively related to students’ physical health (r = 0.20, p < 0.05 for extroversion; r = 0.27, p < 0.01 for agreeableness; r = 0.31, p < 0.01 emotional stability). Extroversion and emotional stability were also positively linked to students’ psychological health (r = 0.22, p < 0.05 for extroversion; r = 0.27, p < 0.01 emotional stability). Contrary to the hypothesis, however, none of the personality traits were associated with cultural identification (see Table 5 for details).

Life Experience in China. Findings indicated that the top ten things international students liked about China were, people (21.5%), food (15.9%), historical site (10.9%), weather (6.0%), cultural activity (5.0%), education and job opportunity (4.0%), safety (4.0%), transportation (3.3%), orders and rules (2.6%), and freedom (1.3%). In contrast, the top ten things that international students disliked about China were, language (22.2%), food (14.3%), pollution (13.9%), weather (8.7%), people (6.5%), traffic jam (6.1%), high living expense (4.3%), stereotype of foreigners (3.9%), public restroom (3%), and living condition on campus (2.6%; see Table 6 for details).

Immigration is a global phenomenon in the 21st century, and the issue of acculturation among international students is a widely recognized and important topic (Li et al., 2021; Muganga et al., 2025). As the number of international students in China continues to rise, examining the cultural adaptation issues of international students through the lens of Chinese cultural background holds significant theoretical importance. First, the current study indicated that international students reported overall positive attitudes toward the political, economic, social, and cultural environment of China. This finding aligns with a recent study that found international students in China demonstrate a high level of adaptation to Chinese culture and actively participate in various social activities (Zhao et al., 2023). This highlights the significant role played by the inclusive atmosphere and educational conditions created by China for international students (Mao et al., 2022).

Second, this study also found length of stay and level of education were related to both cultural identification and attitudes toward China. Specifically, as international students stayed longer in China, and the level of education increased, they identified more with the Chinese culture, and had more positive attitudes toward China. Their positive attitudes were also linked to better physical and psychological health, which was consistent with the finding of previous research on the relationship between acculturation and health (Schwartz et al., 2010). This relationship underscores the intricate dynamics between temporal engagement in a cultural context and the psychological adjustments associated with immersion in a new environment. Consistent with Berry’s framework of acculturation, the strong correlation between length of stay and cultural adaptation has led to the consideration of duration of stay as an indicator of cultural adaptation (Ahn & Lee, 2023). Individuals with higher levels of education demonstrate strong adaptability across various domains, including not only academic adjustment (San & Guo, 2023) but also cultural adaptation. This finding aligns with previous research advocating for the inclusion of social determinants in studies of cultural adaptation, as the negative effects of educational inequality can extend to cultural adaptation (Szabó, 2022). Furthermore, a positive attitude toward the host culture is associated with less cognitive dissonance and more proactive coping strategies, making it a significant antecedent of individual health outcomes (Samnani et al., 2012).

Finally, cultural values and personality traits predicted acculturation and health. As international students scored higher on the “interdependence” dimension of self-construal, they adjusted more quickly (i.e., having more positive attitudes and better health), potentially due to the shared cultural values between themselves and the Chinese people. This result is highly consistent with research on person-environment fit, which suggests that individuals experience better adaptation and health outcomes when there is a high degree of compatibility between themselves and their environment (Jung et al., 2024; Van Vianen, 2018). Extraversion and emotional stability were also positively related to both attitudes toward China and health. Extraverted individuals tend to actively expand their social networks (Rollings et al., 2023). As a result, extraverted international students may accumulate greater social capital (Moshkovitz & Hayat, 2021), which accelerates their adaptation to China and contributes to the development of enhanced health capital (Bolin et al., 2003). These frequent social interactions also lead to increased cultural knowledge and reinforce positive attitudes toward the host culture. Emotionally stable individuals typically perceive stress as manageable rather than threatening (Kundi et al., 2022), making it easier for them to adapt to stressful situations. Consequently, this ability contributes to achieving high levels of cultural adaptation and overall well-being.

Implications for international student support services

The results of this study also offer practical insights for relevant departments. First, given the importance of acculturation for the health of international students, it is beneficial to incorporate components of acculturation into public health intervention programs aimed at this population (Wu et al., 2018). For instance, promoting traditional Chinese culture can enhance international students’ cultural identification with China, improve their personal environmental fit, and foster positive attitudes toward China through appropriate ways (Mao & Ji, 2024). Personality traits such as extraversion and emotional stability contribute to acculturation and promote the physical and mental well-being of international students. However, these traits are relatively difficult to change. Therefore, enhancing acculturation can be achieved by intervening in modifiable factors associated with these traits. For example, facilitating greater participation in school activities can help expand international students’ social networks (Arthur, 2017; Hendrickson, 2018). Integrating courses aimed at cultivating emotional stability into the curriculum may also support the cultural adaptation and health of international students.

Limitations, future directions, and conclusions

The current study has several limitations. First, the majority of the participants came from Asia (India and Korea) and/or developing countries (e.g., India and Africa). It is quite possible that international students from Western and developed countries might have different adjustment experiences than those in the current sample (Qadeer et al., 2021). Second, the length of time in China was quite short for most participants. Students who have lived long in China might have different attitudes and experiences. Moreover, many other relevant variables, such as racism and discrimination, are likely to influence international students’ acculturation and well-being in China (Brown & Jones, 2013). Future research could incorporate additional related variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of these dynamics. Finally, the sample size was small, and all participants were recruited from three universities in China. Therefore, this study serves as a preliminary foundational investigation. Future research should collect nationally representative data and compare the findings to those of the current study (Xiang et al., 2024). Despite the above limitations, the current study provides empirical evidence revealing international students’ life experiences in China and their attitudes toward China. The findings help clarify some misunderstandings and biases in lay persons’ perceptions of international students’ lives in China and have implications for future research on acculturation and health.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yang Jia, Yanyan Zhang; data collection: Yang Jia, Yanyan Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Yang Jia. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This investigation was approved by the ethics committees of the School of Philosophy and Sociology, Jilin University (There was no specific approval number attached to the approval.). All participants provided written informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Ahn, S., & Lee, S. (2023). Bridging the gap between theory and applied research in acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 95, 101812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2023.101812 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arthur, N. (2017). Supporting international students through strengthening their social resources. Studies in Higher Education, 42(5), 887–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1293876 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Benet-Martínez, V., & Haritatos, J. (2005). Bicultural identity integration (BIIComponents and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality, 73(4), 1015–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00337.x [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Berry, J. W. (1997). Constructing and expanding a framework: Opportunities for developing acculturation research. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 62–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01095.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Berry, & John, W. (2006). Contexts of acculturation. In: David, L. S. & John, W. B. (Eds.Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology (pp. 27–42New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Bolin, K., Lindgren, B., Lindström, M., & Nystedt, P. (2003). Investments in social capital—implications of social interactions for the production of health. Social Science & Medicine, 56(12), 2379–2390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00242-3 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Brown, L., & Jones, I. (2013). Encounters with racism and the international student experience. Studies in Higher Education, 38(7), 1004–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2011.614940 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

David, E. J. R., Okazaki, S., & Saw, A. (2009). Bicultural self-efficacy among college students: Initial scale development and mental health correlates. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(2), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015419 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Diaz, V. A. (2005). Research involving Latino populations. Annals of Family Medicine, 3(5), 470–471. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.402 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gao, X., & Hua, Z. (2021). Experiencing Chinese education: Learning of language and culture by international students in Chinese universities. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 34(4), 353–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2020.1871002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gibson, M. A. (2001). Immigrant adaptation and patterns of acculturation. Human Development, 44(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1159/000057037 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B.Jr (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hendrickson, B. (2018). Intercultural connectors: Explaining the influence of extra-curricular activities and tutor programs on international student friendship network development. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 63(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.11.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA, USA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

Jung, F. U., Löbner, M., Rodriguez, F. S., Engel, C., Kirsten, T. et al. (2024). Associations between person-environment fit and mental health-results from the population-based LIFE-Adult-Study. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 2083. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19599-z [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

King, R., & Raghuram, P. (2013). International student migration: Mapping the field and new research agendas. Population, Space and Place, 19(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1746 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kodippili, T., Ziaian, T., Puvimanasinghe, T., Esterman, A., & Clark, Y. (2024). The impact of acculturation and psychological wellbeing on South Asian immigrant adolescents and youth: A scoping review. Current Psychology, 43(25), 21711–21722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05981-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kundi, Y. M., Sardar, S., & Badar, K. (2022). Linking performance pressure to employee work engagement: The moderating role of emotional stability. Personnel Review, 51(3), 841–860. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-05-2020-0313 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, C. S. (2019). Global linguistic capital, global cultural capital: International student migrants in China’s two-track international education market. International Journal of Educational Development, 67(3), 94–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.03.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, M., Reese, R. J., Ma, X., & Love, K. (2021). The role of adult attachment in international students’ acculturation process. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 81, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2020.12.008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, W., & Lin, X. (2016). Meeting the needs of Chinese international students: Is there anything we can learn from their home system? Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(4), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316656456 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ma, J., & Zhao, K. (2018). International student education in China: Characteristics, challenges, and future trends. Higher Education, 76(4), 735–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0235-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mao, Y., & Ji, H. (2024). Acculturation in China: Acculturation strategies, social support, and self-assessment of Mandarin learning performance of international students in Chinese universities. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 4, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2024.2399643 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mao, Y., Ji, H., & Wang, R. (2022). Expectation and reality: International students’ motivations and motivational adjustments to sustain academic journey in Chinese universities. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 833407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.833407 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (2014). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. In: College student development and academic life (pp. 264–293Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Moshkovitz, K., & Hayat, T. (2021). The rich get richer: Extroverts’ social capital on twitter. Technology in Society, 65(6), 101551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101551 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Muganga, A., Mekonen, Y. K., Adarkwah, M. A., Oladipo, O. A., Nweze, C. N., & et al. (2025). Is everywhere I go home? Reflections on the acculturation journey of African international students in China. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 105(2), 102136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2024.102136 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2011). China Statistical Yearbook. Retrieved from: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2011/indexeh.htm [Google Scholar]

Qadeer, T., Javed, M. K., Manzoor, A., Wu, M., & Zaman, S. I. (2021). The experience of international students and institutional recommendations: A comparison between the students from the developing and developed regions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 667230. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.667230 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Raval, V. V., Banerjee, M., Patel, P., Gandhi, R., Durazi, A. et al. (2025). Exploring South Asian American identities, acculturation, contexts and the intersections of mental and physical health: A scoping review. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), e70047. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.70047 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Riaño, Y., Van Mol, C., & Raghuram, P. (2018). New directions in studying policies of international student mobility and migration. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 16(3), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2018.1478721 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rollings, J., Micheletta, J., Van Laar, D., & Waller, B. M. (2023). Personality traits predict social network size in older adults. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49(6), 925–938. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672221078664 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rosenthal, T. (2018). Immigration and acculturation: Impact on health and well-being of immigrants. Current Hypertension Reports, 20(8), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-018-0872-0 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Samnani, A. K., Boekhorst, J. A., & Harrison, J. A. (2012). Acculturation strategy and individual outcomes: Cultural diversity implications for human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 22(4), 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2012.04.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

San, C. K., & Guo, H. (2023). Institutional support, social support, and academic performance: Mediating role of academic adaptation. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38(4), 1659–1675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-022-00657-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., & Szapocznik, J. (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019330 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 580–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205014 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Szabó, Á. (2022). Addressing the causes of the causes: Why we need to integrate social determinants into acculturation theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 91(4), 318–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.01.014 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Vianen, A. E. (2018). Person-environment fit: A review of its basic tenets. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 75–101. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104702 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ware, J. E. Jr, & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-ltem short-form health survey (SF-36I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, Q., Ge, T., Emond, A., Foster, K., Gatt, J. M. et al. (2018). Acculturation, resilience, and the mental health of migrant youth: A cross-country comparative study. Public Health, 162(6), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.05.006 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xiang, B., Xin, M., Fan, X., & Xin, Z. (2024). How does career calling influence teacher innovation? The chain mediation roles of organizational identification and work engagement. Psychology in The Schools, 61(12), 4672–4687. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.23302 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zander, S. (2008). Acculturation, perceived social dominance orientation, and perceived social support among European international students [Ph.D. thesis]. Norman, OK, USA: The University of Oklahoma. [Google Scholar]

Zea, M. C., Asner-Self, K. K., Birman, D., & Buki, L. P. (2003). The abbreviated multidimentional acculturation scale: Empirical validation with two Latino/Latina samples. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9(2), 107–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.107 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhao, S., Al-Nahdi, Y. A. A. S., Si, F., & Butt, T. F. (2023). University students adaptation to the Chinese culture: A case study of Middle East and North Africa (MENA) university students in China. International Journal of Islamic Thought, 23, 109–125. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools