Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Design thinking pedagogy effects on undergraduates’ career decision-making self-efficacy and employability: A pilot intervention study

1 School of Life Sciences and Food Engineering, Hanshan Normal University, Chaozhou, 521041, China

2 Faculty of Education, Languages, Psychology, and Music (FoELPM), SEGi University, Petaling Jaya, 47810, Malaysia

3 School of Geography, Tourism and Teochew Cuisine, Hanshan Normal University, Chaozhou, 521041, China

* Corresponding Author: Yukai Chen. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 327-333. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068042

Received 08 January 2025; Accepted 17 April 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study examined the effects of design thinking pedagogy on undergraduates’ career decision-making self-efficacy and employability in career education. Using a quasi-experimental design, Chinese college students (N = 93) were participants in two wings. The experimental group (n = 47) received the design thinking pedagogy, while the control group (n = 46) followed the regularly teacher-centered method. The students completed the career decision-making self-efficacy scale and employability scale before and after the intervention. Independent samples t-test results showed that design thinking pedagogy significantly improves students’ career decision-making self-efficacy and employability. The ANCOVA results showed that the pretest scores of career decision-making self-efficacy and employability had no significant association with the experimental intervention. There was no interaction between the treatment and pretest scores. It would seem that experimental design thinking pedagogy implemented in career guidance courses has little effect compared to the usual course presentation. Nonetheless, prospects for the implementation of design thinking-guided learning activities to support interdisciplinary learning for improved higher education and career development outcomes need further exploration.Keywords

Design thinking is the process by which education providers conceptualize and create new products, services, or systems, with the ultimate aim of enhancing learner-centered experiences and lifelong learning adaptability (Dunne & Martin, 2006). In the digital age, this is implemented broadly as a student-focused instructional strategy (Simeon et al., 2022; Yang and Hsu, 2020). Its many advantages include improving instructional efficacy (Liu et al., 2024; Simeon et al., 2022) and adapting to the demands of the information era. However, the efficacy of design thinking has not been tested utilizing a case comparison study approach. Efficacy studies that utilized quasi-experimental design to compare design thinking learner outcomes hold great prospects for advancing the field. Career decision-making self-efficacy and employability are key factors in college student learning outcomes (Hu et al., 2019), of which no studies have examined design thinking effects as a pedagogy. Our study examined the effects of design thinking pedagogy on the career decision-making self-efficacy and employability self-perceptions of college students. Employment is the foundation of economic security. The findings can provide some empirical evidence to fill the gap in the interdisciplinary use of design thinking for career education and undergraduates’ career development.

Design thinking and theoretical basis

Design thinking pedagogy is an approach that creates learning project situations for students from real-life problems and guides them to use their knowledge to define problems and propose solutions. It comprises five elements of empathize (E), define (D), ideate (I), prototype (P) and test (T) based on EDIPT model (Taimur & Onuki, 2022). Empathize refers to designers deeply understanding the needs of learners and educators through observation, interviews, and immersion in their context. Define means synthesizing insights from the empathy phase to articulate a clear, actionable problem statement focused on learner or institutional needs. Ideate refers to generating a wide range of creative, divergent ideas to address the defined problem, often through collaborative brainstorming. Prototype means developing representations of ideas to explore feasibility and gather early feedback. Test refers to iteratively refining prototypes by gathering feedback from students and measuring impact. In the context of education for employment, design thinking pedagogy prioritizes student-centered thinking, problem-solving, teamwork and goal-oriented, which as critical employability skills (Bhatti et al., 2023).

Design Thinking can be used as a pedagogy to develop learners’ creativity, collaboration, problem solving, and innovation in the teaching and learning process (Luka, 2019; Högsdal & Grundmeier, 2021). Regardless, and as previously noted, design thinking pedagogy is scarcely used in the field of education other than in the fields of business, STEM education, and service design (Liu, 2021; Rusmann & Ejsing-Duun, 2022).

The social cognitive career theory (SCCT) emphasizes choice options, and coping is consistent with design thinking (Brown & Lent, 2013; Lent et al., 2017; Lent & Brown, 2019, 2020; Miles & Naidoo, 2017). As examples, SCCT proposes for information banks for career guidance and exposure to work opportunities (Aprile & Knight, 2020). Design thinking pedagogy as a SCCT-based intervention would increase students’ decision-making self-efficacy (McWhirter et al., 2019; Miles & Naidoo, 2017), as needed for the development of the ongoing knowledge economies (Sharma, 2023). Design thinking pedagogy is not a one size fits all and outcomes would depend of the context of implementation, as by the education system priorities and resources.

The Chinese student learning outcomes contexts

An increased number of Chinese college graduates are struggling to obtain employment to meet employers’ expectations in the context of digitalizing economies (Cheng, 2017; Ntale et al., 2020; Han & Huo, 2022). Part of the solution would be to rely less on teacher-centered instruction, which limits their capacity to help students develop critical thinking and to utilize design thinking pedagogy for more marketable skills upon graduation. Yet, design thinking pedagogy for employment preparation is less well studied in the Chinese context.

For instance, in China, the majority of career guidance courses still use conventional teaching methods, in which knowledge is delivered to students through lecturers, supported by teaching media (Qin, 2022). In this instructional modality, the majority of students are relegated to a passive role, merely receiving knowledge. However, in a design thinking instructional classroom, students work in groups to complete the design of a product using design thinking procedures and tools of empathy, ideation, prototyping, feedback, and reflection. Increasingly, Chinese education systems seek to integrate design thinking into the curriculum, students’ creativity and self-assurance increase dramatically (Tae, 2016; Wingard et al., 2022; Yang & Hsu, 2020). As an example, the Chinese education policy proposes that students take a career guidance course to master job search skills through self-analysis, environmental analysis, understanding the employment situation, and clarifying the employment skills that meet the requirements of employers. These education processes would enhance the students’ career decision self-efficacy and employability (Li et al., 2018). Nonetheless, evidence is needed on how and whether design thinking works to expectations in the context of career education and employability.

We tested a pilot intervention to provide evidence on the efficacy of design thinking pedagogy effects for career guidance course outcomes. We proposed to answer the following questions in the Chinese context.

1: To what extent would design thinking pedagogy enable career decision-making self-efficacy?

2: Would design thinking pedagogy explain students’ self-perceived employability?

Research design, participants and setting

The study adopted a quasi-experimental design. Study participants were 93 undergraduate students majoring in biological sciences, and also taking a career guidance course. By age, they were between the ages of 20–21.

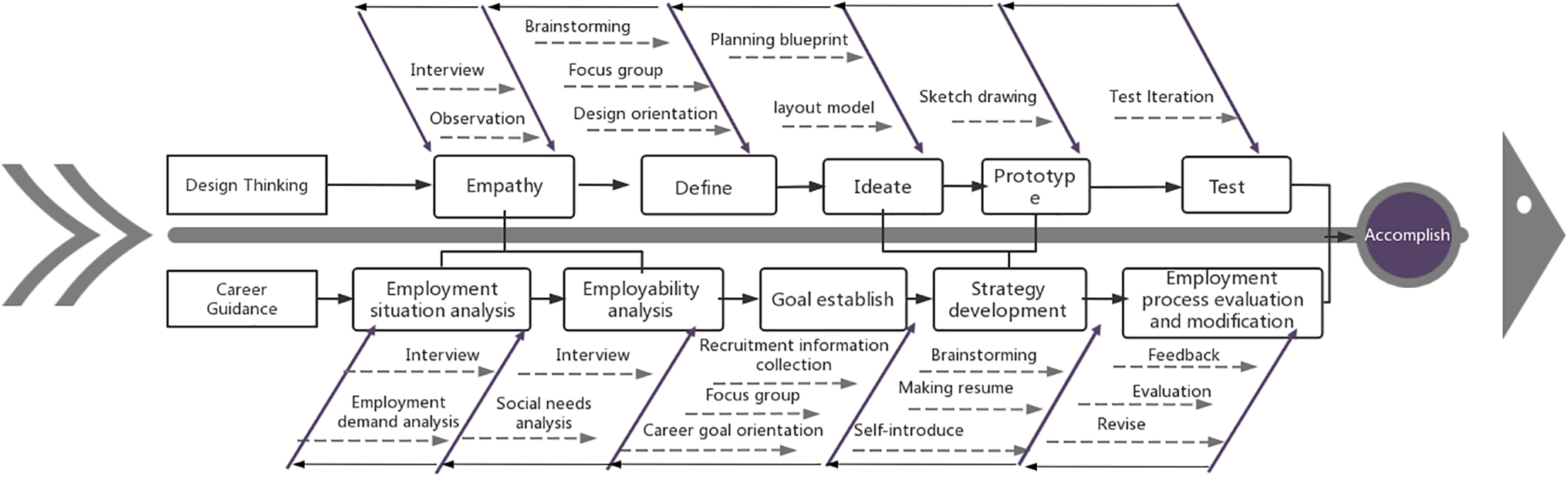

The experimental group (EG) consisted of 47 students (male: 9, female: 38) and the control group consisted of 46 students (male: 9, female: 37). In career guidance course, experimental group (n = 47) received design thinking pedagogy, while control group (n = 46) followed conventional teaching method (see study Figure 1). Both classes were taught by the same lecturer with 7 years of career guidance course teaching experience. Every student who volunteered to take part in this experiment provided their consent and they all completed the pre-test and post-test, which included the career decision-making self-efficacy scale and employability scale.

Figure 1: The intervention procedure

Study protocol and implementation

Over a 9-week experiment, students in the experimental group participated in weekly career guidance course with the design thinking pedagogy, and students in the control group participated in career guidance classes with the conventional teaching pedagogy. The effects of the design thinking intervention on career decision-making self-efficacy and employability were determined through pre-test and post-test to answer the research question one and research question two.

Through structured career guidance teaching training, students learn about employment situation and policies, competition, and legal rights. The intervention process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Modules and design thinking pedagogy. Students in both the experimental and control groups were taught by the same lecturer. The 9-week, 18-credit career guidance course consisted of 5 modules: employment situation analysis, employability analysis, goal setting, strategy development, and employment process evaluation and modification.

During the first week, both experimental group and control group students completed pre-test, including the career decision-making self-efficacy scale and the employability scale. The experimental group of students utilized the design thinking pedagogy and the control group of students used the conventional teaching method. Students were divided into groups to accomplish tasks in the design thinking process in the experimental group. The experimental group utilized Stanford University School of Design’s 5-step design thinking model: empathy, definition, idea, prototype, and test (Taimur & Onuki, 2022). The instructor teaches essential concepts, tools, and methods related to career guidance throughout the course, enabling students to acquire theoretical foundations and develop design thinking. In terms of practice, each group selects a practical task to apply the steps and tools of design thinking to, and the resulting design is shared and evaluated to determine the direction of the career guidance iteration.

Figure 2 illustrates the 5 modules of a career guidance course, the five processes of design thinking, and how to integrate design thinking in a career guidance course adapted from Lin and Wang (2022). In week 9, both experimental group and control group students completed post-test, including the career decision-making self-efficacy scale and the employability scale.

Figure 2: The integration of design thinking in career guidance course employing design thinking

During the first week, both experimental group and control group students completed pre-test, including the career decision-making self-efficacy scale and the employability scale.

Career decision-making self-efficacy scale

The Career Decision Self-Efficacy Scale (CDMSE, Peng & Long, 2001), measures three dimensions of goal selection (7 items, e.g., I can choose the career or job I want, even if its employment opportunities are trending downward.), self-evaluation (3 items, e.g., I can determine what my ideal career is.), and information gathering (3 items, e.g., I can find out information about a career or job that I am interested.) The items are scores on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (fully not confident) to 5 (fully confident). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for scores from CDMSE Scale was 0.862, indicating high reliability. The average variance extracted (AVE) value was 0.783, indicating good convergent validity of the variables.

The Employability Scale (ES; Yu et al., 2014) includes 15 items on five dimensions of interpersonal relationship (5 items, e.g., I can manage complex interpersonal relationships easily.), teamwork (4 items, e.g., I am willing to work with others.), professional identity (2 items, e.g., I have a clear career plan.), network differences (2 items, e.g., The people I associate with are from different majors and schools.) and learning ability (2 items, e.g., I always want to learn new knowledge.). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scores from ES was 0.801, indicating high reliability. The average variance extracted (AVE) value was 0.558, indicating good convergent validity of the variables.

Ethics approval and participant consent

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Segi University (SEGiEC/SR/FOELPM/17/2023-2024). Participants consented to the study. They were made aware that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without needing to give a reason. They completed the data surveys manually. All data was securely stored on a computer protected by a unique password.

Debriefing. After the study conclusion, students were informed about the nature of their treatment in both the experimental and control groups. We did this to provide an understanding that none of them would necessarily be harmed by their study assignment.

Data were analyzed utilizing the SPSS 25.0. Firstly, the normal distribution test was conducted to determine whether the sample data obey a normal distribution, which is a prerequisite for parametric statistical analysis. Table 1 presents the data following the Shapiro-Wilk test are all above 0.05, indicating that the data follow a normal distribution the experimental and control groups. Between group comparisons were by the independent samples t-test regarding the on the pre-test and post-test scores. Then, using pre-test scores as a covariate to account for initial pre-test differences, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was done to examine the differences between the two groups’ post-test scores.

Compared to the control group, the experimental group’s participants’ employability scores and self-efficacy in making career decisions significantly improved following the intervention. We present the specific findings aligned to our research questions.

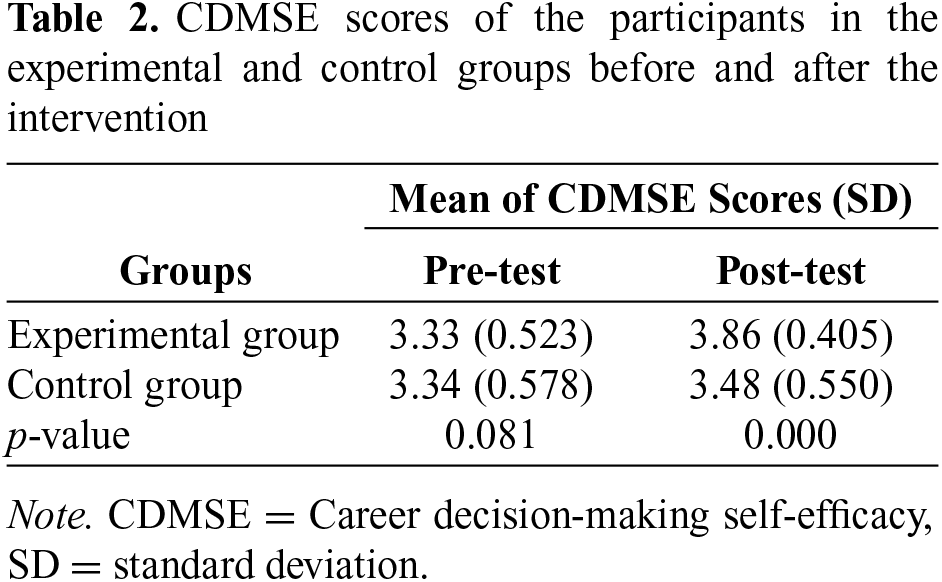

Design thinking effects on self-efficacy scores in professional decision-making

Table 2 shows the mean of students’ career decision-making self-efficacy scores in the experimental and control groups. As in Table 2, there was no significant difference in the scores of students’ perceived level of career decision-making self-efficacy between the control group (M = 3.34, SD = 0.578) and the experimental group (M = 3.33, SD = 0.523; t (91) = 0.150, p = 0.881, two-tailed). After the intervention, there was a significant difference in the scores of students’ perceived level of career decision-making self-efficacy between the control group (M = 3.48, SD = 0.550) and the experimental group (M = 3.86, SD = 0.405; t (91) = –3.727, p = 0.000, two-tailed).

Controlling for pre-test scores. Table 3 shows the ANCOVA results of career decision-making self-efficacy on the post-test. After adjusting for pre-test scores, there was a significant difference between the control group and experimental group on post-test scores on the career decision-making self-efficacy, F (1,90) = 13.875, p = 0.000, partial eta squared = 0.134. Moreover, there was no significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores on the career decision-making self-efficacy, as indicated by a partial eta squared value of 0.005.

Design thinking and employability scores

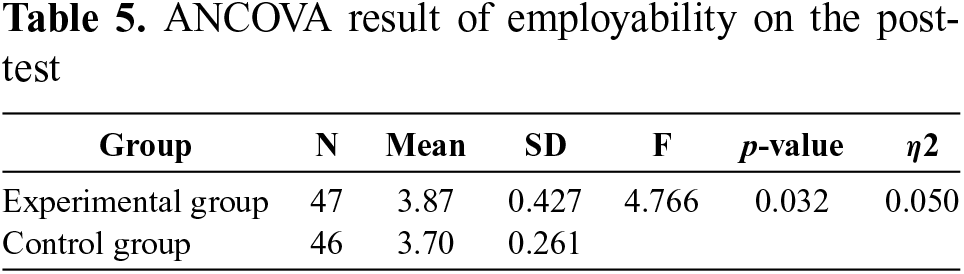

Table 4 presents the mean of students’ employability scores in the experimental group and control group. As apparent from Table 4, there was no significant difference in the scores of students’ perceived level of employability between the control group (M = 3.64, SD = 0.386) and the experimental group (M = 3.49, SD = 0.418; t (91) = 1.757, p = 0.082, two-tailed). After the intervention, there was a significant difference in the scores of students’ perceived level of employability between the control group (M = 3.70, SD = 0.261) and the experimental group (M = 3.87, SD = 0.427; t (91) = –2.410, p = 0.018, two-tailed).

Table 5 shows the ANCOVA results of employability on the post-test. There was a significant difference between the control group and experimental group on post-test scores on the employability, F (1,90) = 4.766, p = 0.032, partial eta squared = 0.050. Moreover, there was no significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores on employability, as indicated by a partial eta squared value of 0.010.

In short, employing design thinking in career guidance courses can significantly improve students’ self-efficacy in making career decisions and employability.

Interaction effects. The ANCOVA results showed that the pretest scores had no significant impact on the experimental intervention, indicating no interaction between treatment and pre-test (Ary et al., 2010). Thus, it can be concluded that the improvement is because of the treatment alone which employs design thinking in career guidance course.

Undergraduates’ career decision-making self-efficacy in the post-test was significantly higher than their pre-test. Moreover, the results showed that there was a significant difference between the control group and experimental group on post-test scores on the career decision-making self-efficacy. The finding is consistent with the conclusion that design thinking had a positive influence in the career decision-making self-efficacy of students (Sun, 2019). Previous research has shown that design thinking can improve students’ problem-solving abilities (Fields & De Jager, 2022; Guaman-Quintanilla et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2023). These findings imply that design thinking pedagogy resulted in improved student career decision-making self-efficacy in career guidance course. This effect likely resulted from design thinking pedagogy emphasizes on self-appraisal, career information gathering and goal selection (Lake et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023) as tools for generating creative solutions with engagement of the curriculum and improved the quality of instruction.

During the learning process in career guidance course employ design thinking pedagogy, students resulted with enhanced self-exploration and clarity their employability and self-efficacy in professional decision-making. This study finding is similar to the prior study of Reid and Kelestyn (2022), which found that design thinking interventions are beneficial in enhancing the employability of college students. The finding may be explained by the fact that learners combine creative collaboration and effective cooperation to promote deep learning (Lin et al., 2022), and for knowledge of the labour market from an employer’s perspective (Yang, 2018). Thus, the design thinking would increase students’ employability skills.

Design thinking pedagogy has the potential to significantly improve students’ 21st century skills like creativity, problem solving, communication, collaboration, and critical thinking (Luka, 2019; Rusmann & Ejsing-Duun, 2022; Taimur et al., 2022), which are all closely related to employability and may be able to effectively enhance college students’ employability. Findings extend the application of design thinking in career development of college students, with the aim of enhancing college students’ career decision-making self-efficacy and employability.

The five steps of design thinking, namely empathy, define, ideate, prototype and test, can be applied to a variety of activities in career guidance course (Sun, 2019). When effectively implemented, these elements of design thinking can affect students’ career objective selection, problem solving, career information gathering, and job search skills, all of which are crucial for their long-term career development.

Limitations and future directions

The main limitation of this study was the use of a convenience sample, limiting of generality findings. Future studies may consider utilizing a probability sample for the generalizability of the results.

Moreover, this study did not validate the instructional effects on students’ self-efficacy in career decision-making and the employability of different design thinking stages. Effects may be different by stage in unknown ways. Finally, uncontrollable teacher and student attributes may have influenced study outcomes in unknown ways. Future longitudinal iterative design or mixed studies would improve on the findings.

This study conducted a quasi-experiment in career guidance courses for college students to investigate whether design thinking pedagogy can enhance college students’ career decision-making self-efficacy and employability. Career guidance courses employing design thinking significantly increase college students’ self-efficacy in making career decisions (Sun, 2019). Self-efficacy in career decision-making is significantly related to employability (Wang et al., 2019; Huang, 2015a, 2015b). The results demonstrated that the integration of design thinking pedagogy in career guidance courses is effective in enhancing college students’ career decision-making self-efficacy and employability.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the Hanshan Normal University under Grant [QD2024214].

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Hanshan Normal University Research Initiation Program (QD2024214).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yahong Cai, Nalini Arumugam; data collection: Yukai Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on request.

Ethics Approval: Ethics Committee of Segi University (SEGiEC/SR/FOELPM/17/2023-2024).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Aprile, K. T., & Knight, B. A. (2020). The WIL to learn: Students’ perspectives on the impact of work-integrated learning placements on their professional readiness. Higher Education Research and Development, 39(5), 869–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1695754 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ary, D., Jacobs, L. C., & Sorensen, C. (2010). Introduction to research in education. Belmont, CA, USA: Wadsworth. [Google Scholar]

Bhatti, M., Alyahya, M., Alshiha, A. A., Qureshi, M. G., Juhari, A. S., et al. (2023). Exploring business graduates employability skills and teaching/learning techniques. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 60(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2022.2049851 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 557–568. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cheng, W. (2017). An empirical study on the employability of college students and its improvement—based on the effective sample analysis of 64 colleges and universities in China. Higher Education Exploration, 7, 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dunne, D., & Martin, R. (2006). Design thinking and how it will change management education: An interview and discussion. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 5(4), 512–523. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMLE.2006.23473212 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fields, Z., & De Jager, C. (2022). The Educational Design Ladder and design thinking pedagogy: A customised training programme for creative problem-solving. Journal of Contemporary Management, 19(2), 135–156. https://doi.org/10.35683/jcm21075.162 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guaman-Quintanilla, S., Everaert, P., Chiluiza, K., & Valcke, M. (2023). Impact of design thinking in higher education: A multi-actor perspective on problem solving and creativity. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 33(1), 217–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-021-09724-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Han, L., & Huo, F. (2022). The improvement of college students’ employability in the context of supply-side reform. China University Employment, 18, 42–47. https://doi.org/10.20017/j.cnki.1009-0576.2022.18.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hu, Y. H., Jing, Y., & Cao, X. M. (2019). The relationship between college students’self-efficacy in career decision-making and employability: The intermediary role of career planning. Theory and Practice of Education, 39(12), 38–40. [Google Scholar]

Huang, B. C. (2015a). The study on the elements, the characteristics and the building way of college students’ employment ability structure. Employment of Chinese College Students, 8, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

Huang, J. T. (2015b). Hardiness, perceived employability, and career decision self-efficacy among taiwanese college students. Journal of Career Development, 42(4), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845314562960 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Högsdal, S., & Grundmeier, A.-M. (2021). Integrating design thinking in teacher education: Student teachers develop learning scenarios for elementary schools sabine. The International Journal of Design Education, 16(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-128X/CGP/v16i01/1-26 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lake, D., Flannery, K., & Kearns, M. (2021). A cross-disciplines and cross-sector mixed-methods examination of design thinking practices and outcome. Innovative Higher Education, 46(3), 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09539-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2019). Social cognitive career theory at 25: Empirical status of the interest, choice, and performance models. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115(3), 103316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.06.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2020). Career decision making, fast and slow: Toward an integrative model of intervention for sustainable career choice. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103448 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lent, R. W., Ireland, G. W., Penn, L. T., Morris, T. R., & Sappington, R. (2017). Sources of self-efficacy and outcome expectations for career exploration and decision-making: A test of the social cognitive model of career self-management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.01.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, F., Huang, W., Ge, L., Wang, J., Rao, Z., et al. (2018). Teaching of employment guidance course in colleges based on design thinking method. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, 290, 80–84. https://doi.org/10.2991/icedem-18.2018.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, L., Dong, Y., & Shen, S. (2022). Theoretical framework and supporting technologies of design thinking pedagogy. Modern Distance Education Research, 34(4), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-5195.2022.04.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, Q., & Wang, C. (2022). Construction of the educational model of vocational college students’ career planning based on design thinking. Ergonomics in Design, 47(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.54941/ahfe1001912 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, X. L. (2021). The relationship between occupational values, professional commitment and employability of college students. Jiangsu Higher Education, 12, 128–131. https://doi.org/10.13236/j.cnki.jshe.2021.12.022 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, X., Gu, J., & Xu, J. (2024). The impact of the design thinking model on pre-service teachers’ creativity self-efficacy, inventive problem-solving skills, and technology-related motivation. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 34(1), 167–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-023-09809-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luka, I. (2019). Design thinking in pedagogy: Frameworks and uses. European Journal of Education, 54(4), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12367 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

McWhirter, E. H., Rojas-Araúz, B. O., Ortega, R., Combs, D., Cendejas, C., et al. (2019). ALAS: An intervention to promote career development among latina/o immigrant high school students. Journal of Career Development, 46(6), 608–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845319828543 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Miles, J., & Naidoo, A. V. (2017). The impact of a career intervention programme on South African Grade 11 learners’ career decision-making self-efficacy. South African Journal of Psychology, 47(2), 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246316654804 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ntale, P., Ssempebwa, J., Musisi, B., Ngoma, M., Genza, G. M. et al. (2020). Interagency collaboration for graduate employment opportunities in Uganda: Gaps in the structure of organizations. Education and Training, 62(3), 271–291. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-08-2019-0193 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peng, Y. X., & Long, L. R. (2001). Study on the scale of career decision-making self-efficacy for university students. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 7(2), 38–43. [Google Scholar]

Qin, W. (2022). The use of group work method in teaching college students’ career planning course. Educational Observation, 17, 95–98. https://doi.org/10.16070/j.cnki.cn45-1388/g4s.2022.17.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Reid, E. R., & Kelestyn, B. (2022). Problem representations of employability in higher education: Using design thinking and critical analysis as tools for social justice in careers education. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 50(4), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2022.2054943 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rusmann, A., & Ejsing-Duun, S. (2022). When design thinking goes to school: A literature review of design competences for the K-12 level. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 32(4), 2063–2091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-021-09692-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sharma, A. (2023). Consolidation of employability in Nepal: A reflective look. Industry and Higher Education, 37(5), 673–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/09504222221151138 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Simeon, M. I., Samsudin, M. A., & Yakob, N. (2022). Effect of design thinking approach on students’ achievement in some selected physics concepts in the context of STEM learning. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 32(1), 185–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-020-09601-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun, Z. M. (2019). The effect of design thinking on students’ career self-efficacy in career guidance course. [Doctoral dissertation, University of the Pacific]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (Order No. 13814393). [Google Scholar]

Tae, J. (2016). The effect of design thinking-based STEAM education on elementary school student interest in math and science, personality, and science and technology career choice. Asia-Pacific Journal of Educational Management Research, 1(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.21742/ajemr.2016.1.1.01 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Taimur, S., & Onuki, M. (2022). Design thinking as digital transformative pedagogy in higher sustainability education: Cases from Japan and Germany. International Journal of Educational Research, 114, 101994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2022.101994 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Taimur, S., Onuki, M., & Mursaleen, H. (2022). Exploring the transformative potential of design thinking pedagogy in hybrid setting: A case study of field exercise course. Japan Asia Pacific Education Review, 23(4), 571–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09776-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, J., Liu, Z. G., & Duan, H. M. (2019). The effect of career decision self-efficacy on graduate students’ employability. Education Management, 19, 147–148. [Google Scholar]

Wang, X. H., Wang, H. P., & Lai, W. Y. (2023). Sustainable career development for college students: An inquiry into SCCT-based career decision-making. Sustainability, 15(1), 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010426 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wingard, A., Kijima, R., Yang-Yoshihara, M., & Sun, K. (2022). A design thinking approach to developing girls’ creative self-efficacy in STEM. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 46(3), 101140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2022.101140 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, J. (2018). Employers’ evaluation of college graduates’ employability: Based on the importance-satisfaction perspective. Higher Education Exploration, 9, 118–122. [Google Scholar]

Yang, C. M., & Hsu, T. F. (2020). Integrating design thinking into a packaging design course to improve students’ creative self-efficacy and flow experience. Sustainability, 12(15), 5929. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12155929 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yu, H. B., Zheng, X. M., Xu, C. Y., & Yan, C. L. (2014). The relationships between university student’s employability with subjective and objective job-search performance: Liner and invert-U relationships. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 46(6), 807–822. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2014.00807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools