Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sleeping the mind before the body: Mechanisms of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality among Chinese college students

1 College of Electronic Commerce, Anhui Business College, Wuhu, 241002, China

2 Institute of Curriculum and Education, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, 210024, China

* Corresponding Author: Mingjie Huang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 369-376. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068057

Received 20 May 2025; Accepted 03 July 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

The present study examined the role of emotional balance and the moderating role of rumination in the relationship between psychological inflexibility and sleep quality among college students. Participants were 837 Chinese college students (females = 52%, mean age = 18.89, SD = 0.93 years). They completed the Multidimensional Psychological Inflexibility Scale (MPIS), Affect Balance Scale (ABS), Ruminative Response Scale (RRS), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). We utilized moderated-mediation analysis to explore the mechanism of action among variables. Emotional balance mediated the relationship between psychological inflexibility and sleep quality, and rumination moderated the direct effect of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality and the mediating effect of emotional balance. Specifically, the direct effect of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality and the mediating effect of emotional balance increased with the increase in rumination level. High levels of rumination in individuals exacerbate the negative effects of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality. It also enhances the disruption of psychological inflexibility on the individual’s emotional balance ability, which leads to poorer sleep quality. The results contribute to the evidence of how psychological inflexibility explains the sleep quality of college students and how sleep quality can be improved by psychological inflexibility interventions, rumination interventions, and emotional balance interventions. Student development services should provide targeted students’ sleep quality counseling for the promotion and maintenance of college students’ physical and mental health.Keywords

College students carry a 27.6 risk for sleep deprivation (Chen and Huang, 2018). Sleep deprivation would harm their physical and psychological health (Wang et al., 2022), with experience of anxiety and depression (Zhang et al., 2015), and self-injurious and suicidal ideation (Shi et al., 2020). Sleep quality abnormalities (e.g., dysfunctions such as difficulty falling asleep and early waking) are prevalent among college students (Zhang et al., 2015). Poor sleep among college students may lead to physical and mental health problems such as obesity (Wang et al., 2022). Mindfulness as psychological flexibility may be an antidote to student’s harms from sleep deprivation (Ong et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2018), and yet less well investigated.

Psychological inflexibility and sleep quality

Psychological inflexibility, refers to an individual’s inability to persist in effective action in pursuit of a worthwhile life due to negative experiences in daily life (Hayes et al., 2006, 2012; Levin et al., 2014). It encompasses six core components, named lack of contact with present, experiential avoidance, self-as-content, fusion, lack of contact with values, and inaction (Fang and Huang, 2022; Fang et al., 2024). Applied to sleep studies, psychological inflexibility severely disrupts sleep (Zakiei et al., 2020), and sleep quality through thought rumination (Fialko et al., 2012). Poor sleep might be associated with college students’ use of flexible and inflexible skill. Use of psychologically inflexible or rigid skills (e.g., fusion, inaction) and reduce or interfere with the use of psychologically flexible skills (e.g., defusion, self-as-context) might promote poor sleep when handling uncomfortable or unwanted thoughts, feelings, and experiences (Huang et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2024). Thereby increasing the sleep abnormalities. Randomized-controlled trials involving mindfulness meditation (to improve ‘lack of contact with present’) have demonstrated some efficacy in treating insomnia (Ong et al., 2014; Ong et al., 2018).

The Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) approach suggests that is an individual’s level of psychological inflexibility an effective predictor of psychological symptoms and disorders (Fang and Huang, 2022, 2023; Fang et al., 2023a, 2023b). Specifically, ACT theory posits that individuals habitually develop avoidance behavior which could be inflexible (Barnes-Holmes et al., 2001). ACT targets for treatment of the processes associated with psychological inflexibility, such as lack of contact with present, experiential avoidance, self-as-content, fusion and lack of contact with values in daily activities (Hayes, 2016; Zhang et al., 2012).

Mediating role of emotional balance

Emotional balance or openness to experience of positive and negative emotions (Chen et al., 2014; Larsen, 2009) is associated with the capacity to regulate emotions (Yu & Liu, 2025). In particular, individuals with emotional balance have cognitive flexibility, and positive emotions, such as pleasure and contentment, have been demonstrated to have a significant facilitating effect on sleep quality (Zoccola et al., 2009; Ong et al., 2017; Liu, 2024). Conversely, poor emotional balance is the disruptive effect on sleep quality (Kahn et al., 2013; Ong et al., 2017). Studies have shown that psychological inflexibility is significantly correlated with emotional balance ability. Psychological inflexibility exacerbates the individual’s experiential experience of negative emotions and inhibits the mobilization of positive emotional resources (Liu & Yan, 2023; Orouji et al., 2022; Peltz et al., 2020). Thus, psychological inflexibility may inhibit the ability of emotional balance to contribute to sleep quality.

Rumination which is the continuous and negative reflection on negative emotions (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) increases the risk of anxiety and depression (Morrison & O’Connor, 2005; Miranda et al., 2013). It achieved this negative effect by weakening problem-solving skills, and reducing social support resources (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Rumination may directly exacerbate an individual’s sleep problems in studies addressing factors influencing sleep quality (Liu, 2024). Given the characteristics of rumination in exacerbating the negative effects of negative factors, it can be hypothesized that the negative effects of psychological inflexibility may be more prominent in individuals with higher levels of rumination. In particular, high levels of rumination may lead to more severe sleep problems by amplifying the damaging effects of psychological inflexibility on the ability to regulate emotional balance. The mechanism of this effect remains unexplored. Therefore, the present study explored these relationships among Chinese college students.

The results of the latest meta-analysis show that the sleep problems of college students in Chinese higher education institutions have shown a trend of gradual exacerbation over the past two decades (Fang et al., 2020). In Chinese culture, there is an old saying that sleeping the mind first, then sleeping the body. This concept suggested to achieve a state of mental calm before engaging in sleep. This entails the process of calming one’s mood, removing distracting thoughts, and attaining a tranquil state of mind. This preliminary step is believed to be a crucial element in attaining a favorable sleep state. It is worth noting that “Sleeping the mind” is related to the self-discipline emphasized by the Mencius’s theory (Huff, 2015). Self-discipline means being conscientious and strict with oneself, as well as emphasizing self-control and repression. “Self-control and repression” are regarded as a virtue by college students growing up in the context of Chinese culture. Following this view, suppressing emotions may damage sleep quality.

The present study examined the role of emotional balance and the moderating role of rumination in the relationship between psychological inflexibility and sleep quality among college students (see Figure 1). It tested the following hypotheses:

Figure 1: The moderated mediation model

H1: Psychological Inflexibility is associated with poor sleep quality.

H2: Emotional Balance plays a mediating role between psychological inflexibility and sleep quality for higher sleep quality.

H3: Rumination moderates the relationship of psychological inflexibility and sleep quality, for lower sleep quality.

H4: Rumination moderates the mediating effect of emotional balance on psychological inflexibility and Sleep quality for lower emotional balance and for lower sleep quality.

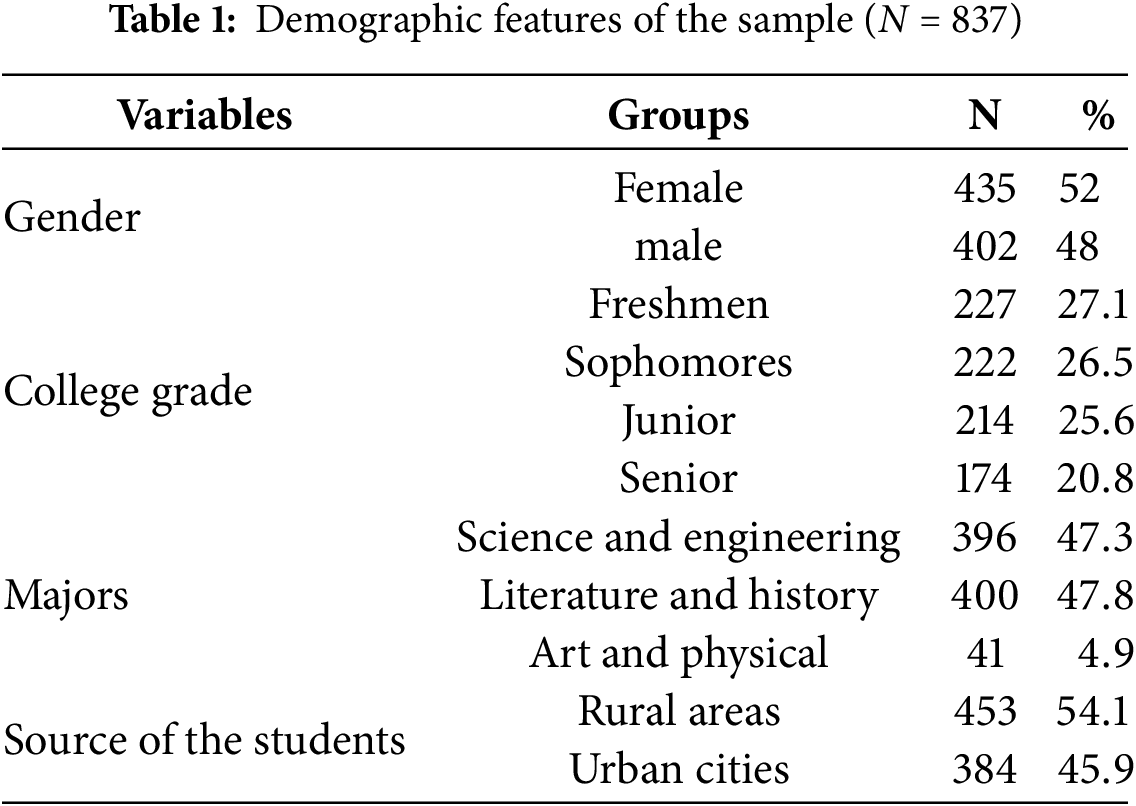

Participants were 837 college students (average age = 18.89 years, SD = 0.93 years) (see Table 1).

Multidimensional psychological inflexibility scale (MPIS)-Chinese version

The MPIS (Fang and Huang, 2022) is a 30-item scale and consists of six dimensions: lack of contact with present, experiential avoidance, self-as-content, fusion, lack of contact with values, and inaction. Each item is scored on a 6-point scale from 1 (never) to 6 (always), e.g., “I tried to distract myself when I felt unpleasant emotions” and the higher the cumulative score, the higher the degree of psychological inflexibility of the individual. The Cronbach’s alpha of the MPIS scores was 0.85.

Affect balance scale (ABS)-Chinese version

The ABS (Wang et al., 1999) is a 10-item scale. Of these, 5 items were used to measure positive emotions (e.g., “feeling happy because I accomplished something”),and 5 items were used to measure negative emotions (e.g., “depressed or very unhappy”). Each item is scored on a 4-point scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The positive emotional Score is subtracted from the negative emotional Score to give an Emotional Balance Score, with higher scores indicating a higher level of Emotional Balance in the individual. The Cronbach’s alpha of the ABS scores was 0.74.

Ruminative response scale (RRS)-Chinese version

The RRS (Dai et al., 2015) is a 22-item scale and contains three dimensions: depression, obsessive meditation, and rumination. Each item is scored on a 4-point scale from 1 (rarely) to 4 (almost always), e.g., “Think about all of your shortcomings, failures, flaws, and mistakes” with higher scores indicating that an individual’s tendency to ruminate is more severe. The Cronbach’s alpha of the RRS scores was 0.89.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)-Chinese VErsion

The PSQI (Liu et al., 1996) is an 18-item scale. Each item is scored on a 4-point scale from 0–3, e.g., “Difficulty falling asleep (inability to fall asleep within 30 min)”. The cumulative score is the total Sleep quality score, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. The Cronbach’s alpha of the PSQI scores was 0.76.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Anhui Business College. All students voluntarily participated in the research and none of them had significant clinical psychological symptoms. Data were collected using an online platform.

The data were organized and analyzed using SPSS 27.0. The initial step involved descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of the data. Subsequently, we conducted hierarchical multiple regression analyses to test the mediating effect by entering the control variables and psychological inflexibility and emotional balance as independent variables in separate steps, while setting sleep quality as the dependent variable. Finally, the SPSS macro program PROCESS was employed to test the moderated mediating model (Model 8), and bootstrapping analyses were used to test our hypotheses.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

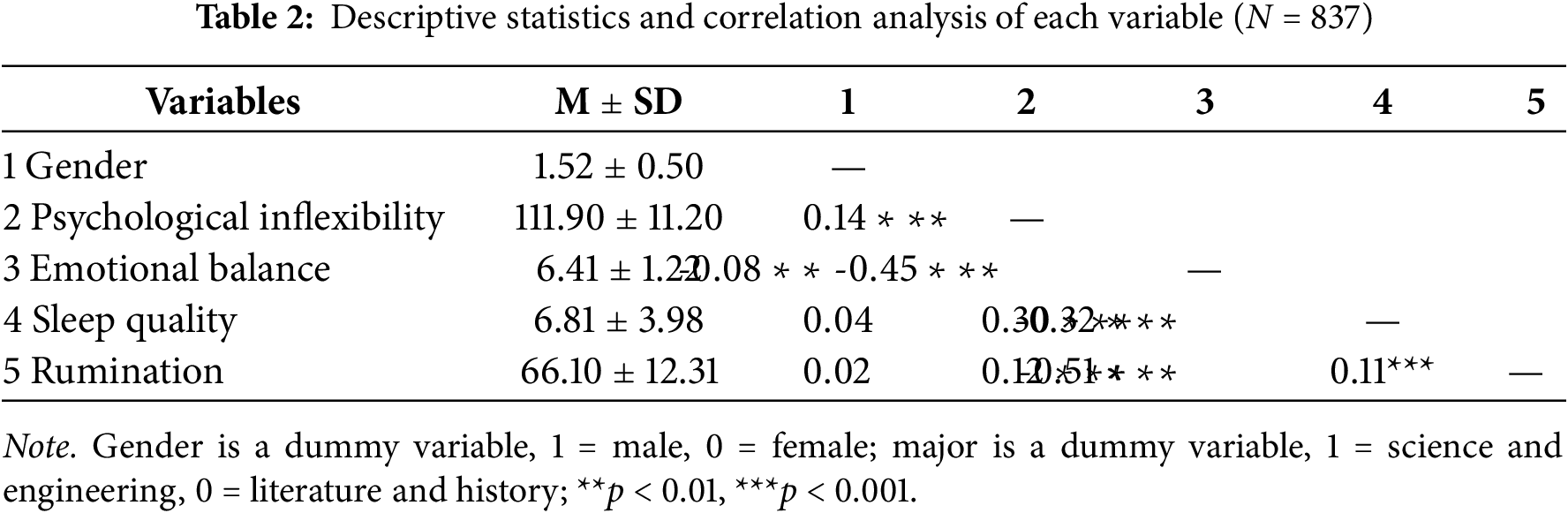

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation analysis for the study variables. The results are higher psychological inflexibility to be associated with poor sleep quality score and rumination. Emotional balance exhibited a significant negative correlation with sleep quality score and rumination, while rumination demonstrated a significant positive correlation with sleep quality score. Gender was the sole significant correlate of psychological inflexibility. This variable was included as a control in the regression equation to exclude its potential influence on the subsequent model test results.

Psychological inflexibility and sleep quality

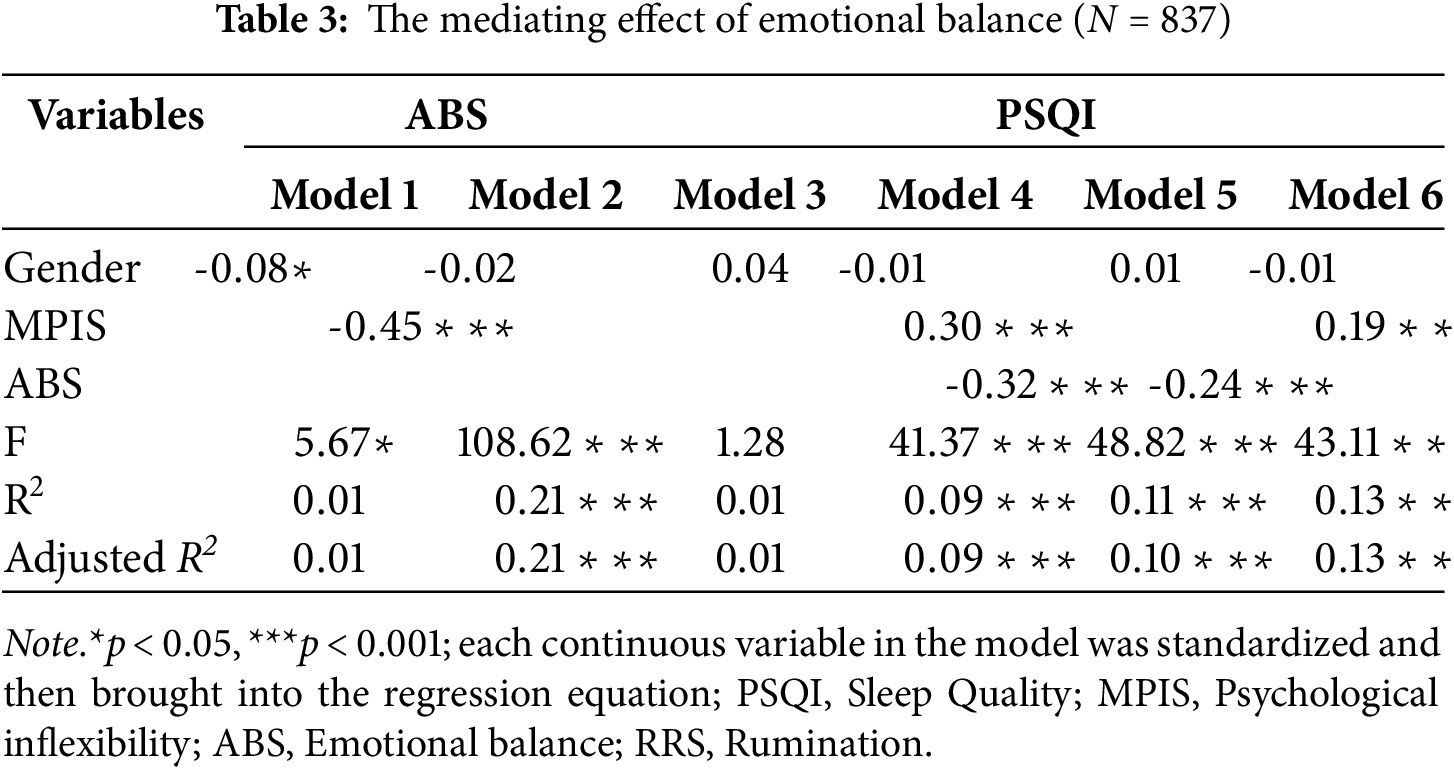

As in Table 3, after controlling for the effect of gender on poor sleep quality, psychological inflexibility significantly positively predicts poor sleep quality (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). It suggests that the higher the psychological inflexibility, the poorer the sleep quality. Hence H1 was supported.

The mediating effect of emotional balance

As in Table 3, psychological inflexibility significantly negatively predicts emotional balance (β = −0.45, p < 0.001)). Emotional balance negatively predicted sleep quality (β = −0.23, p < 0.001), The results indicated that the mediating effect of emotional balance was 0.11, with a 95% bootstrap confidence interval of [0.06, 0.15], and the mediating effect accounted for 36.67% of the total effect. The effect of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality was partially mediated by emotional balance. Hence H2 was supported.

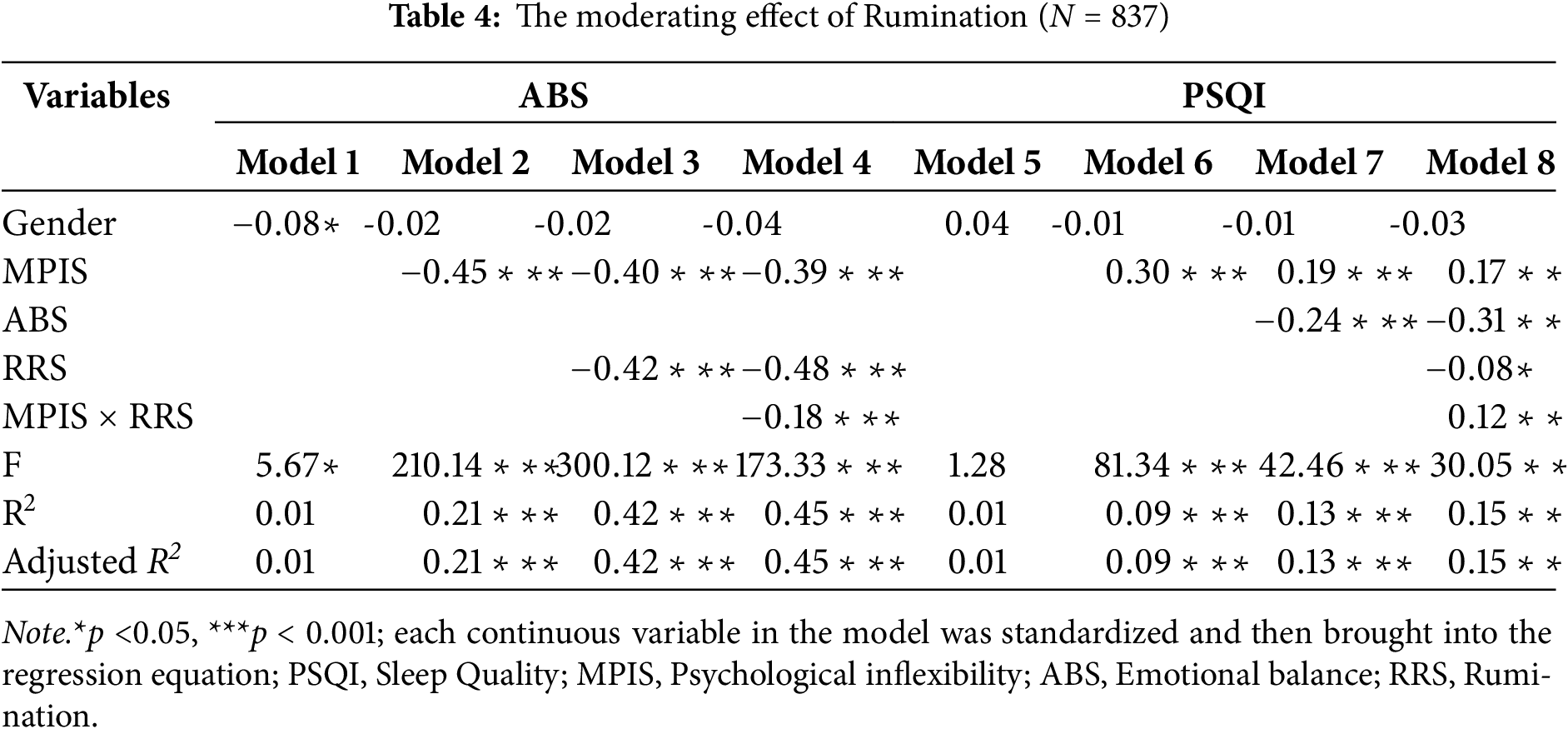

The moderated mediating effects

We conducted bootstrapping procedures to test the conditional indirect effect and chose 5000 bootstrap estimates based on a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval PROCESS, Model 8) to test the moderated mediating model. Table 4 shows the interaction term between Psychological inflexibility and Rumination significantly and positively predicted Sleep quality score (β = 0.12, p < 0.001), indicating that the effect of Psychological inflexibility on Emotional balance is moderated by rumination, hence H3 was supported. Similarly, the interaction term between Psychological inflexibility and rumination significantly negatively predicted Emotional balance (β = −0.18, p < 0.001), indicating that Rumination significantly moderated the effect of psychological inflexibility on emotional balance, hence H4 was supported.

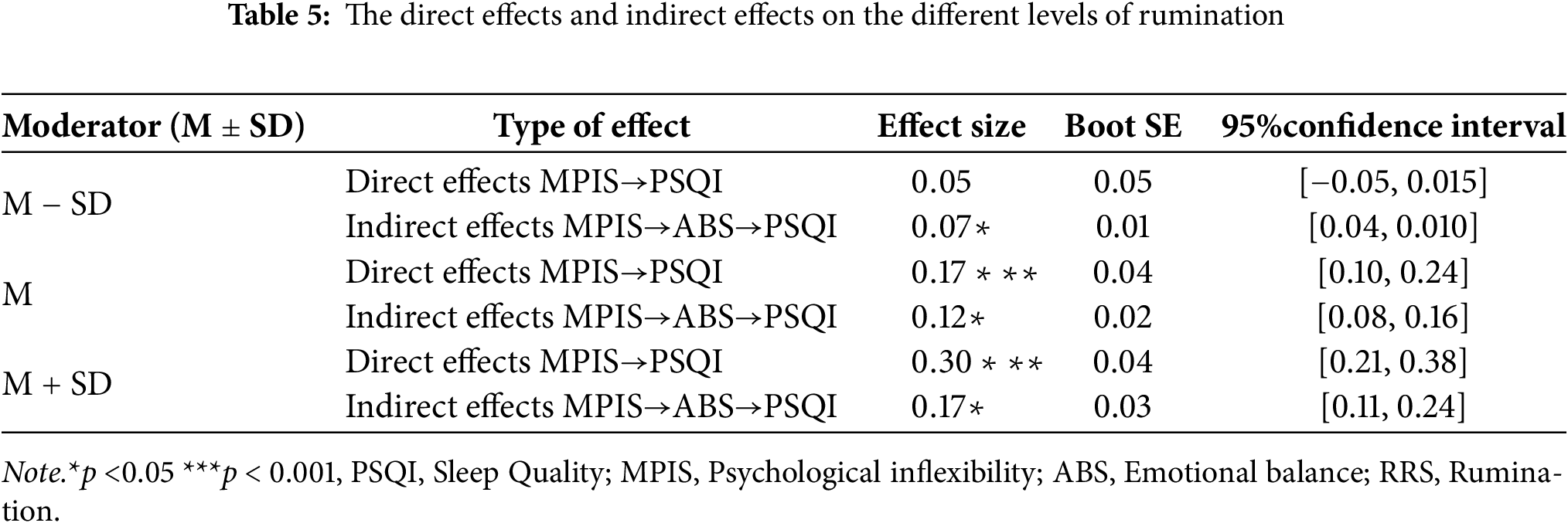

To further elucidate the nature of the moderating effect, the mean of rumination scores plus or minus one standard deviation was divided into two groups: a high-level rumination group, and a low-level rumination group,and plotted this relationship. Figure 2 further revealed that the positive relationship between psychological inflexibility and sleep quality was stronger when rumination was high rather than low. Additionally, Figure 3 shows that as rumination levels increase, the negative impact of psychological inflexibility on emotional balance becomes stronger. Specifically, the direct effect of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality and the mediating effect of emotional balance increased with the increase in rumination level. Table 5 presented the direct effect of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality, the mediating effect value of emotional balance, and the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals at the three levels of rumination scores (M-SD, M, and M+SD). When rumination was higher, we found a more positive direct effect (direct effect = 0.30, 95% CI = [0.21, 0.38], excluding 0), and a more negative indirect effect (indirect effect = 0.17, 95% CI = [0.11, 0.24], excluding 0). In summary, Emotional balance mediated the relationship between Psychological inflexibility and college students’ Sleep quality, and both the direct effect of Psychological inflexibility on Sleep quality and the mediating effect in the first half of Emotional balance were moderated by rumination.

Figure 2: (Standardized) simple slope analysis of moderated direct effects (MPIS, Psychological Inflexibility)

Figure 3: (Standardized) simple slope analysis of moderated indirect effects (MPIS, Psychological Inflexibility)

The current research results showed that psychological inflexibility significantly and positively predicted sleep quality among college students. Consistent with the findings of previous studies (Zakiei et al., 2020), negative cognitive styles such as experiential avoidance and cognitive fusion work together to act on the individual, making the individual wish to achieve the goal of eliminating those unwanted negative emotions and experiences, but instead seriously affecting Sleep quality. Therefore, the impact of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality of college students cannot be ignored, and reducing the level of psychological inflexibility or increasing psychological flexibility may improve Sleep quality to a certain extent (Fang and Huang, 2022; Fang et al., 2023a, 2023b).

Emotional balance mediates between psychological inflexibility and sleep quality, i.e., psychological inflexibility indirectly influences sleep quality through emotional balance. Consistent with the findings of previous studies (Ong et al., 2017; Zoccola et al., 2009; Liu, 2024), the functioning of negative emotions, such as anxiety, stress, depression, and melancholia, which impair sleep quality was enhanced. This consequently results in an exacerbation of sleep disturbances among college students. It is important to note that emotional balance enables individuals to accept their inner feelings in a balanced perspective (there are times when they are “upset” and times when they are “proud of others’ praises”) (Chen et al., 2014; Larsen, 2009). College students with psychological inflexibility are more likely to exhibit inflexibility in response to various negative events, which in turn weakens their emotional balance ability. Once the mechanism of emotional balance of college students was compromised, the functioning of positive emotions, such as contentment and pleasure, which facilitate sleep quality, was weakened (Fredrickson, 2001; Ong et al., 2017). In other words, emotional balance may be a remedy for students suffering from sleep deprivation, yet individuals with psychological inflexibility may exacerbate negative emotional immersion due to rigid cognitive patterns and inhibit the mobilization of positive emotional resources, affecting sleep quality (Orouji et al., 2022; Peltz et al., 2020).

The level of rumination exerted a significant moderating influence on the direct and indirect effects of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality. Specifically, both the direct and indirect effects of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality increased with rising levels of rumination.

Conversely, The findings of this study indicate that rumination serves to exacerbate the adverse effects of psychological inflexibility through two distinct pathways. Path 1: Psychological inflexibility → Sleep quality (H1 was supported), and Path 2: Psychological inflexibility → Emotional balance (H4 was supported). Rumination served as both a catalyst for psychological inflexibility to interfere with sleep and a disruptor of emotional balance’s ability to promote sleep quality. The explanations for this phenomenon can be attributed to three key factors. Primarily, rumination exacerbates the negative thinking patterns observed in college students (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). College students with high levels of rumination may experience decreased sleep quality due to repeated chewing stress events and their resulting negative experiences. Secondly, rumination is associated with psychological inflexibility and an inability to effectively cope with and solve problems (Moberly and Watkins, 2008; Cao et al., 2021). College students with higher levels of rumination perceive less emotional support in interpersonal interactions (Zhang et al., 2021).

The results of this study enrich the research in the field of college students’ sleep problems and provide effective empirical evidence and intervention suggestions for improving Sleep quality, so as to deal with college students’ sleep problems in a scientific and rational way.

Student development and support should utilize positive thought meditation, cognitive defusion, and clarification of values techniques of acceptance and commitment therapy, to cultivate the ability of college students to face negative events flexibly and effectively, thus promoting Sleep quality. This will promote sleep quality. Moreover, educators should provide students with training in self-direction and self-balancing, as well as effective management and regulation of emotional balance, to improve sleep quality. In summary, positive thinking training would prompt students to accept and experience the present moment without judgment, thereby reducing or eliminating the tendency to ruminate on negative emotions. For example, the Chinese proverb “A fall into a pit, a gain in your wit.”. This, in turn, promotes emotional balance, prevents sleep problems, and ultimately develops good sleep habits.

Limitations and future directions

The main shortcomings of this study include reliance on self-report data. Future studies could gather data from a number of sources, including parents, teachers, roommates, classmates, and close friends. Secondly, Also further investigation of the mechanism linking psychological inflexibility and sleep quality is warranted, with the incorporation of diverse samples aligned with the specific objectives of the study.

We examined how psychological inflexibility, emotional balance, and rumination impact sleep quality in Chinese college students. The results revealed the mediating role of emotional balance and the moderating role of rumination. Specifically, psychological inflexibility, as a negative psychological factor, reduces an individual’s emotional balance ability, thereby affecting sleep quality. At the same time, rumination exacerbates the negative impact of psychological inflexibility on sleep quality and emotional balance. The results of this study not only provide empirical support for previous views, but also provide a new perspective for interventions and research on sleep quality among college students.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This project was one of the projects funded by the Anhui Business College (Project for School level Counselors of Anhui Business College in 2023: “Research on the Influencing Factors and Intervention Mechanisms of Sleep Disorders in College Students” Grant No. 2023KYF08).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mingjie Huang, Yaping Pan; data collection: Mingjie Huang, Yaping Pan; analysis and interpretation of results: Mingjie Huang, Yaping Pan and Jing Shen; draft manuscript preparation: Mingjie Huang, Yaping Pan and Jing Shen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All the methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Anhui Business College. All the participants provided written informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Barnes-Holmes, Y., Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (2001). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 28(4), 101–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2407(02)80063-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cao, H., Mak, Y. W., Li, H. Y., & Leung, D. Y. (2021). Chinese validation of the brief experiential avoidance questionnaire (BEAQ) in college students. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 19, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.01.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, S. M., Fang, J., Gao, S. L., Ye, B. J., Sun, P. Z. et al. (2014). The relationship between self-enhancing humor and life satisfaction: A multiple mediation model through emotional well-being and social support. Journal of Psychological Science, 37, 377–382. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2014.02.022 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, L. S., & Huang, D. (2018). The influence of stop-control and start-control on college students’ sleep problems: The mediating effect of mobile phone dependence. China Journal of Health Psychology, 26(7), 1100–1106. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2018.07.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dai, Q., Feng, Z., & Xu, S. (2015). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version ruminative response scale (RRS) in undergraduates. China Journal of Health Psychology, 23, 5, 753–758. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2015.05.031 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fang, S., & Huang, M. (2022). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of multidimensional psychological inflexibility scale in college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30(6), 1367–1370 1375. https://doi.org/10.16128/j [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fang, S., & Huang, M. (2023). Revision and reliability and validity evaluation of the Chinese version of the comprehensive assessment of acceptance and commitment therapy processes (CompACT) in college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(1), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2023.01.022 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fang, S., Huang, M., & Ding, D. (2023a). Factor structure and measurement invariance of the multidimensional psychological flexibility inventory (MPFI) in Chinese samples. Current Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05255-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fang, S., Huang, M., Ding, D., & Zheng, Q. (2024). The Chinese version of the multidimensional psychological flexibility inventory short form (MPFI-24Assessment of psychometric properties using classical test theory and network analysis. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 33(6), 100805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2024.100805 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fang, S., Huang, M., & Wang, Y. (2023b). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of personalized psychological flexibility index (C-PPFI) in college students. Journal Contextual Behaviour Science, 28(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2023.03.008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fang, B., Liu, C., & Yao, J. (2020). Meta-analysis of results on the sleep quality of college students in China during recent 2 decades. Modern Preventive Medicine, 47(19), 3553–3556. [Google Scholar]

Fialko, L., Bolton, D., & Perrin, S. (2012). Applicability of a cognitive model of worry to children and adolescents. Behav Res Ther, 50(5), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.02.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(1449), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, S. C. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies—republished article. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 869–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, S. C., Pistorello, J., & Levin, M. E. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(7), 976–1002. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012460836 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, S., Kong, H., & Song, Y. (2021). The influence of sleep quality and cognitive fusion on the anxiety of vocational school students. Psychologies Magazine, 16(10), 5–7. https://doi.org/10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2021.10.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huff, B. I. (2015). Eudaimonism in the Mencius: Fulfilling the heart. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 14(3), 403–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11712-015-9444-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kahn, M., Sheppes, G., & Sadeh, A. (2013). Sleep and emotions: Bidirectional links and underlying mechanisms. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89(2), 218–228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Larsen, R. (2009). The contributions of positive and negative effects on emotional well-being. Psychological Topics, 18, 247–266. https://hrcak.srce.hr/48212. [Google Scholar]

Levin, M. E., MacLane, C., Daflos, S., Seeley, J., Hayes, S. C. et al. (2014). Examining psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic process across psychological disorders. Journal Contextual Behaviour Science, 3(3), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Liu, S. (2024). A correlation study between rumination and sleep quality among medical college students. Advances in Psychology, 14(10), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.12677/ap.2024.1410724 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, J., Qi, X., Qu, S., & Gong, S. (2024). Chain mediating effect of psychological inflexibility and sleep quality on self-compassion and subjective well-being in patients with postoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer. China Medical Herald, 21(27), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.20047/j.issn1673-7210.2024.27.17 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, X., Tang, M., Hu, L., Wang, A., Wu, X. et al. (1996). The study on the reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Chinese Journal of Psychiatry, 29, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

Liu, Y., & Yan, N. (2023). The effect of anxiety state and mental flexibility on sleep quality in college students. Advances in Psychology, 13(11), 5096–5102. https://doi.org/10.12677/AP.2023.1311642 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Miranda, R., Tsypes, A., Gallagher, M., & Rajappa, K. (2013). Rumination and hopelessness as mediators of the relation between perceived emotion dysregulation and suicidal ideation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(4), 786–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9524-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moberly, N. J. & Watkins, E. R. (2008). Ruminative self-focus, negative life events, and negative affect. Behavior Research and Therapy, 46(9), 1034–1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Morrison, R., & O’Connor, R. C. (2005). Predicting psychological distress in college students: The role of rumination and stress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843X.100.4.569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ong, A. D., Kim, S., Young, S., & Steptoe, A. (2017). Positive affect and sleep: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 35, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2016.07.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ong, J. C., Manber, R., Segal, Z., Xia, Y., Shapiro, S. et al. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for chronic insomnia. Sleep, 37(9), 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Ong, J. C., Xia, Y., Smith-Mason, C. E., & Manber, R. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for chronic insomnia: Effects on daytime symptoms and cognitive-emotional arousal. Mindfulness, 9(6), 1702–1712. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0911-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Orouji, F., Abdi, R., & Chalabianloo, G. (2022). The mediating role of psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic factor in the relationship between emotional dysregulation and sleep problems with symptoms of emotional disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 800041. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.800041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Peltz, J. S., Rogge, R. D., Bodenlos, J. S., Kingery, J. N., & Pigeon, W. R. (2020). Changes in psychological inflexibility as a potential mediator of longitudinal links between college students’ sleep problems and depressive symptoms. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.12.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shi, X., Zhu, Y., & Ma, X. (2020). Relationship between sleep problems and non-suicidal self-injury behavior among college students. Chinese Journal of School Health, 41(6), 918–921. https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2020.06.032 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, X. D., Wang, X. L., & Ma, H. (1999). Rating scales for mental health. Beijing, China: Chinese Mental Health Journal Press. [Google Scholar]

Wang, X., Wang, C., & Xiong, Y. (2022). Research progress on the effect of sleep on obesity among adults. China Preventive Medicine Journal, 34(9), 898–901. https://doi.org/10.19485/j.cnki.issn2096-5087.2022.09.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yu, Z., & Liu, W. (2025). The psychological resilience of teenagers in terms of their everyday emotional balance and the impact of emotion regulation strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1381239. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1381239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zakiei, A., Khazaie, H., Reshadat, S., Rezaei, M., & Komasi, S. (2020). The comparison of emotional dysregulation and experiential avoidance in patients with insomnia and non-clinical population. Journal of Caring Sciences, 9(2), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.34172/JCS.2020.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, D., Hu, X., & Liu, Q. (2021). Stress and sleep quality among undergraduate students: Chain mediating effects of rumination and resilience. Journal of Psychological Science, 44(1), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20210113 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, J., Liu, Y., & Pan, J. (2015). Relationship between insomnia disorder and depression: Update and future direction. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 29(2), 81–86. [Google Scholar]

Zhang, Q., Wang, S., & Zhu, Z. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACTPsychopathological model and processes of change. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 26(5), 377–381. [Google Scholar]

Zoccola, P. M., Dickerson, S. S., & Lam, S. (2009). Rumination predicts longer sleep onset latency after an acute psychosocial stressor. Biopsychosocial Science and Medicine, 71(7), 771–775. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0b013e3181ae58e8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools