Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Social support and career adaptability among college students: The mediating roles of proactive personality and career decision making self-efficacy

Sociology Department, Changchun University of Science and Technology, Changchun, 130000, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhijun Liu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 361-368. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068059

Received 30 January 2025; Accepted 27 April 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

We examined the relationship between social support and career adaptability, as well as the mediating roles of proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy in this process. A total of 1354 Chinese college students (female = 964; mean age = 19.53 years, SD = 1.33 years) completed an online questionnaire. Path analysis indicated that social support was positively associated with higher levels of career adaptability. Both proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy served as parallel mediators, strengthening the relationship between social support and career adaptability. The complete chain mediation analysis revealed that social support influences career adaptability primarily through proactive personality, which in turn enhances career decision-making self-efficacy, further contributing to increased career adaptability. These findings extend career capital theory by demonstrating that social and psychological resources jointly facilitate career adaptability.Keywords

There is a growing recognition that various career resources possessed by individuals can help address these challenges (Hirschi, 2012). Among these, the role of social capital in career development has been widely acknowledged (Huang et al., 2021; Wilk, 2023). Social support, as a form of career development capital, can facilitate career success by providing individuals with information, resources, and sponsorship (Sou et al., 2022). Moreover, individuals’ intangible skills, such as personality traits, enhance their ability to cope with stress and environmental changes, thereby helping them navigate through difficult times in life (Avey et al., 2009). Nonetheless, the mechanisms that explain the relationship between social support and career adaptability among college students remain underexplored. The current study aims to examine the relationship between social capital and career adaptability, considering the influence of proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy.

Social support and career adaptability

Social capital is an interpersonal network formed through relationship investments, reflecting a reciprocal exchange of mutual benefits (Ehsan et al., 2019). The significance of social relationships cannot be overstated; individuals leverage these connections to access external resources (Tulin et al., 2018), fostering diversity and horizontalization within their professional networks (Arthur et al., 1999). Furthermore, according to social norms and exchange theory, individuals with abundant social capital are more likely to receive external assistance. They also tend to reciprocate support, thereby enhancing the vitality and robustness of their social networks (Wang et al., 2019). This process not only strengthens interconnectedness and the ethos of mutual aid within social networks but also contributes to individual career development.

Social support, a critical component of social capital, encompasses feelings and experiences of being loved, cared for, respected, and valued by others. Embedded within a network of mutual assistance and obligations (Wills, 1991), it can buffer against stressful environments. Research has demonstrated that social support exerts a positive influence on career adaptability (Ataç et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022). For example, the career development of university students is significantly affected by external environmental support, including social support from parents, friends, and other key contacts (Ghosh & Fouad, 2017; Hiester et al., 2009). Individuals who receive such positive social support tend to adapt better to their careers (Öztemel & Yıldız-Akyol, 2021).

Career adaptability refers to an individual’s readiness and resources for coping with current and future vocational development tasks, occupational transitions, and personal challenges; it consists of four key abilities or resources: career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). Career adaptability has a significant impact on employability in various contexts, enhancing subjective career success and employment quality (Chen et al., 2020; Rossier, 2015), and it also plays a crucial role in labor efficiency and overall employability (Hamzah et al., 2021). Scholars regard these psychological resources as self-regulation skills that individuals use to cope with and resolve everyday challenges. They encompass attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that individuals employ to adapt to their job roles (Savickas & Porfeli, 2012). Consequently, current research increasingly focuses on identifying intermediary strategies to enhance career adaptability amonguniversity students, with the goal of guiding their career preparation and improving their prospects of employment success.

The concept of proactive personality, introduced by Bateman and Crant (1993), describes a behavioral tendency to take initiative and overcome obstacles to influence one’s environment. This enduring personality trait embodies proactive coping strategies when facing challenges and is regarded as a key component of psychological capital, which has been shown to improve academic achievement, corporate performance, and nursing outcomes (Grözinger et al., 2022; Martínez et al., 2019; Nasurdin et al., 2018; Ozturk & Karatepe, 2019). Research indicates that proactive personality promotes sustainable personal development and plays a crucial role in enhancing career adaptability (Lee et al., 2021). In practice, individuals with proactive personalities are more likely to actively seek out career opportunities, thereby increasing their career adaptability (Fawehinmi & Yahya, 2018).

Proactive personality primarily manifests across various facets of human functioning, such as work performance, ethical behavior, personal beliefs, attitudes, and relevant cognitions. Career decision-making self-efficacy refers to an individual’s confidence in their ability to perform and complete tasks related to career choices. As a core component of psychological capital, it significantly influences individuals’ further career development, career pursuits, and job satisfaction (Betz, 2007). Research demonstrates that career decision-making self-efficacy is positively correlated with multiple dimensions of career adaptability (Hamzah et al., 2021). Specifically, individuals with high career decision-making self-efficacy are more likely to engage in career exploration and planning, identify their interests, and strive to achieve their career goals with greater success (Choi & Jung, 2018). Furthermore, empirical evidence suggests that social support can indirectly affect career adaptability via general self-efficacy. When individuals perceive higher levels of social support, their career decision-making self-efficacy tends to be enhanced (Angeline, 2021).

It is noteworthy that recent research on career adaptability has increasingly drawn upon the theoretical framework of Career Capital Theory, which offers a novel perspective. This theory proposes three distinct types of career capital: “knowing whom,” “knowing why,” and “knowing how” to navigate unpredictable career environments (Arthur et al., 1995; Beigi et al., 2018), corresponding to social capital, psychological capital, and human capital, respectively (Dickmann et al., 2018). These types of career capital are regarded as possessing cyclical and convertible characteristics. In essence, they can be repurposed to acquire other forms of capital, thereby generating additional resources, including psychological resources (Bourdieu, 1986; Xu et al., 2023). Specifically, social capital and psychological capital are considered to play a crucial role in fostering career adaptability (Arthur et al., 1999). Scholars advocate for integrating social capital, which emphasizes the social environment, with psychological capital, which focuses on the individual, to comprehensively explore career adaptability (Lazarova & Taylor, 2009).

In summary, previous literature has demonstrated that proactive personality positively influences career decision-making self-efficacy (Preston & Salim, 2019). Individuals with high levels of proactive personality are more likely to stand out in their professional roles, achieve success, and exhibit confidence in making career decisions. They generally demonstrate strong self-motivation and autonomy, actively pursue career development opportunities, and effectively manage workplace challenges. Moreover, evidence indicates that proactive personality indirectly predicts career adaptability through its effect on career decision-making self-efficacy (Xin et al., 2020).

The current study aims to examine the relationship between social support and career adaptability, and the roles of proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy in this context. This study tested the following hypotheses.

H1. Social support is associated with career adaptability

H2. Proactive personality and career decision making self-efficacy act strengthen the social support and career adaptability for higher career adaptability.

H3. The indirect effect of social support on career adaptability is mediated by proactive personality, specifically through its influence on career decision making self-efficacy, ultimately increasing career adaptability.

The innovative aspect of this study lies in its integration of social capital and psychological capital in examining their impact on career development based on the theory of career capital. It investigates the relationship between these two forms of capital and explores how social support, as a distal variable, affects career adaptability through proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy. Furthermore, this study enhances the understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between social support and college students’ career adaptability.

Participants were recruited between 8 July and 24 July, 2023. Specifically, a total of 1354 students were selected from six universities in Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Liaoning provinces. From a sociodemographic perspective, the sample included 964 females (71.2%), 533 freshmen (36.6%), 462 sophomores (31.7%), 309 juniors (21.2%), and 152 seniors (10.4%). The mean age was 19.53 years (SD = 1.33). Additionally, 662 students (45.5%) were from rural areas, 303 students (20.8%) came from townships, and 491 students (33.7%) were from urban areas.

The Chinese version of the Perceived Social Support Scale, developed by Zimet et al. (1988), emphasizes individual self-understanding and perception of social support. The scale is a 12-item self-report instrument (e.g., “There is a special person who is around when I am in need”), with participants rating responses on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). A higher score indicates a greater level of perceived social support. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.967.

The Chinese version of the Proactive Personality Scale, adapted by Shang and Gan (2009), based on the original scale by Bateman and Crant (1993), comprises 11 items (e.g., “When I encounter problems, I can face them head-on”) and uses a 7-point Likert scoring system, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). Higher scores indicate stronger proactive personality traits. The scale demonstrated high reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.957.

Career decision making self-efficacy

The Chinese version of the Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale, revised by Peng and Long (2001). It comprises 39 items (e.g., “You are capable of identifying the occupation or job that you are best suited for”) and uses a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), with higher scores indicating greater career decision-making self-efficacy. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.980.

The Chinese version of the Career Adaptability Scale, developed by Hou et al. (2012), contains 24 items (e.g., “I am fully prepared for my future career”) and uses a 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores reflect greater career adaptability. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.949.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Sociology at Changchun University of Science and Technology (Approval No. 20240623). Participants provided informed consent prior to participation. We clarified to participants that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time, and that all data collected would be used solely for research purposes.

Data were analyzed using the SPSS 20.0 software package. To examine mediation and serial mediation effects, we employed the PROCESS macro (http://www.afhayes.com) developed by Hayes (2016, 2017). A rigorous approach was adopted, involving 1000 bias-corrected bootstrap resampling iterations to estimate the 95% confidence intervals of the mediating effects, with significance determined only when the interval did not include zero.

Following recommendations from relevant scholars, Harman’s single-factor test was used to assess potential common method bias (Aguirre-Urreta & Hu, 2019). The unrotated principal component analysis revealed that the first factor accounted for only 37.96% of the total variance, below the critical threshold of 40%. This suggests that common method bias was unlikely to significantly affect the results, allowing subsequent analyses to proceed with confidence.

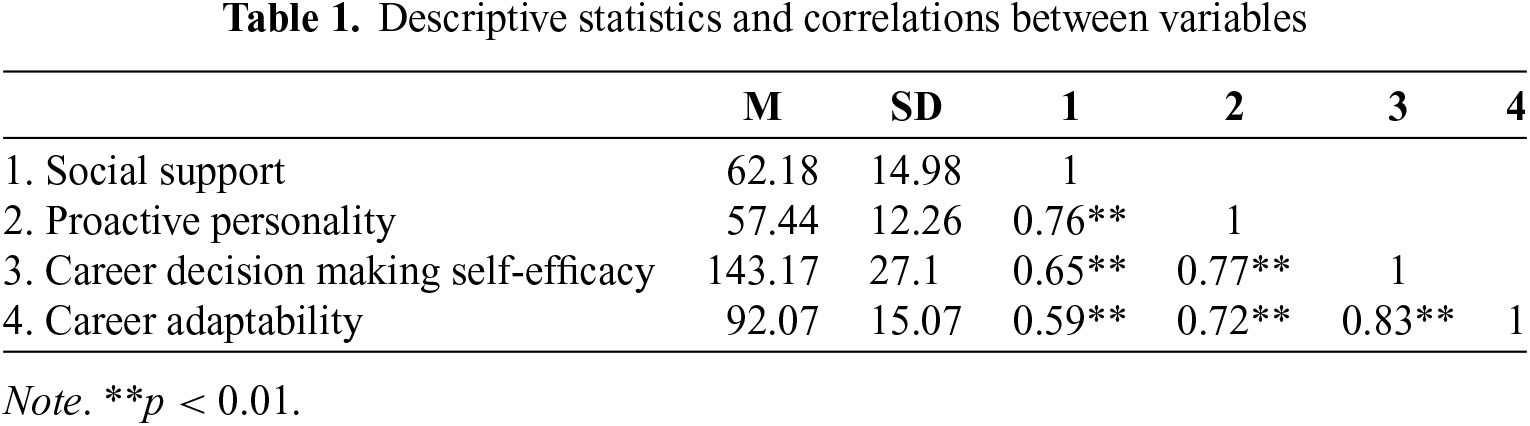

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The results of means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlation analyses are shown in Table 1. The correlation analysis revealed significant relationships among social support, proactive personality, career decision-making self-efficacy, and career adaptability (p < 0.01), satisfying the conditions for mediation analysis.

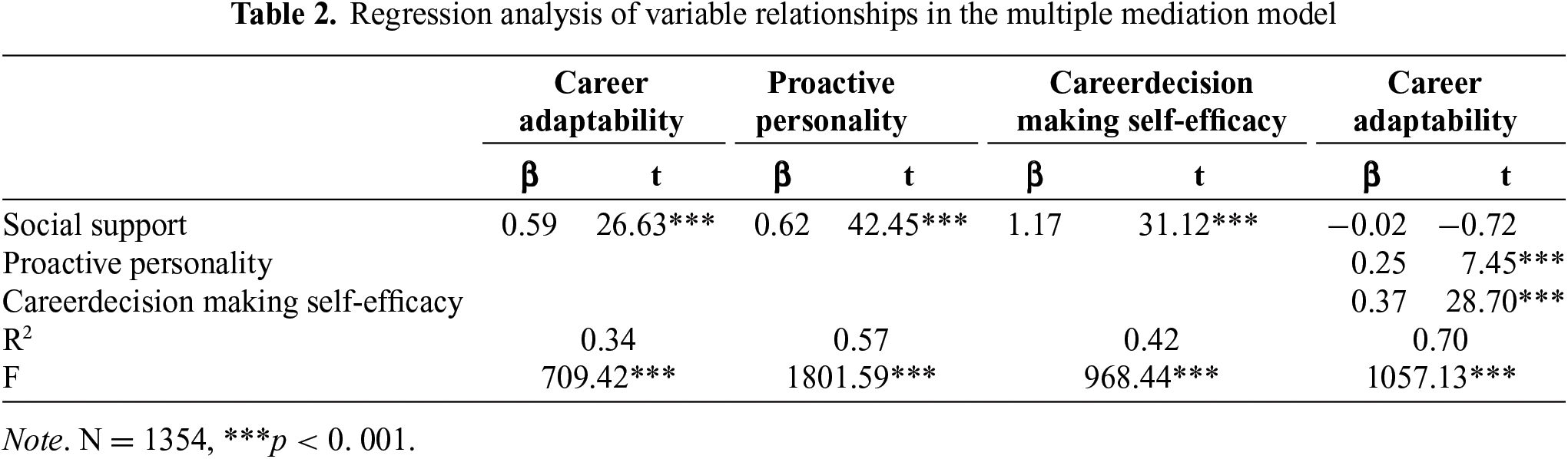

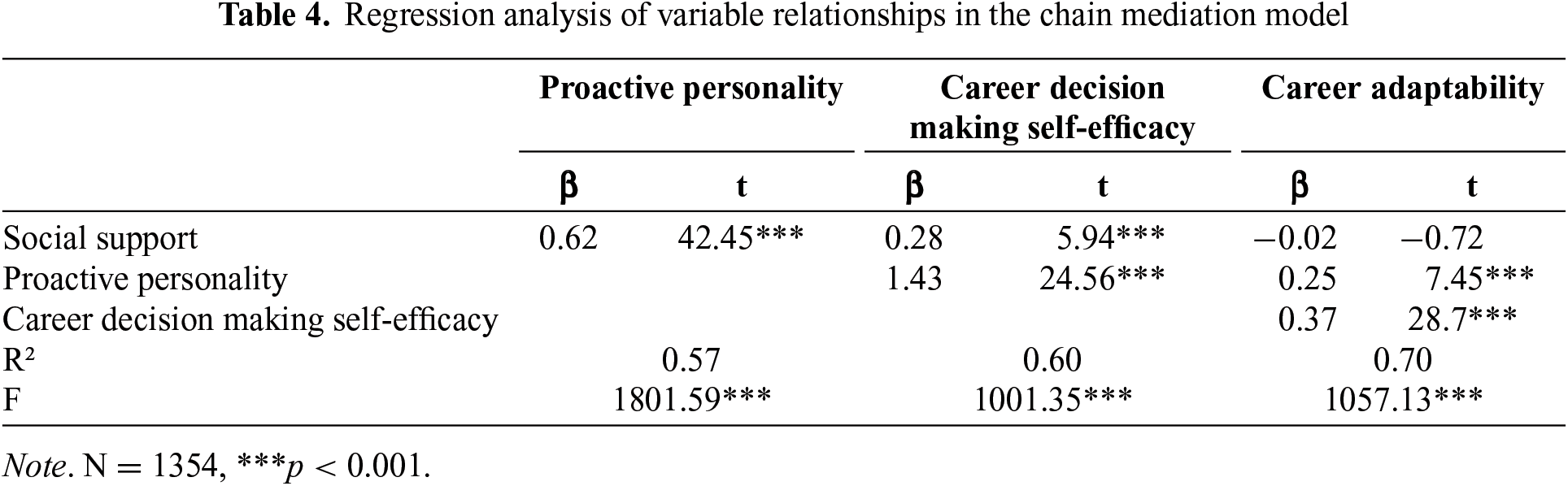

Multiple mediation effects of proactive personality and career decision making self-efficacy between social support and career adaptability

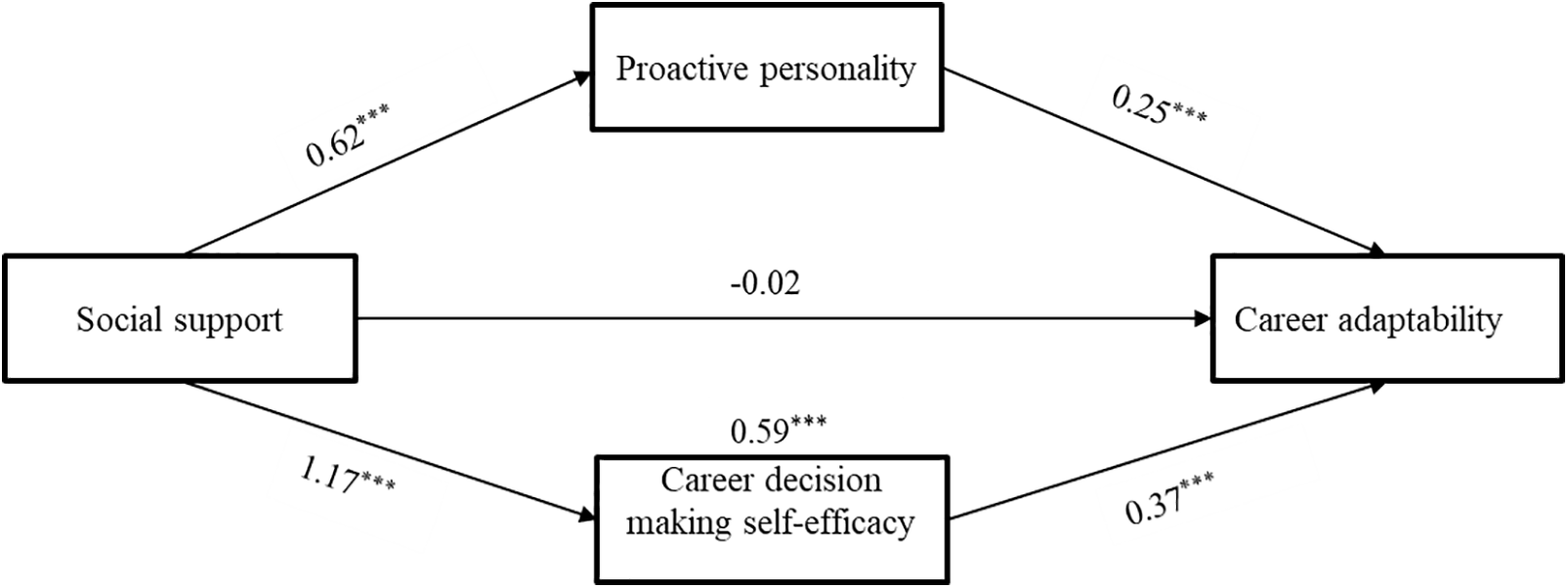

A multiple mediation analysis was employed through Hayes’ SPSS macro PROCESS (model 4; Hayes, 2016, 2017), with the main results summarized in Table 2. The findings indicated that social support, as the independent variable, significantly predicted career adaptability (β = 0.59, t = 26.63, p < 0.001), and also positively predicted the two mediators: proactive personality (β = 0.62, t = 42.45, p < 0.001) and career decision-making self-efficacy (β = 1.17, t = 31.12, p < 0.001). Furthermore, each mediator significantly predicted career adaptability (β = 0.25, t = 7.45, p < 0.001; β = 0.37, t = 28.7, p < 0.001). Notably, when both mediators were included in the model, the direct effect of social support on career adaptability was no longer significant (β = -0.017, t = -0.716, p = 0.943).

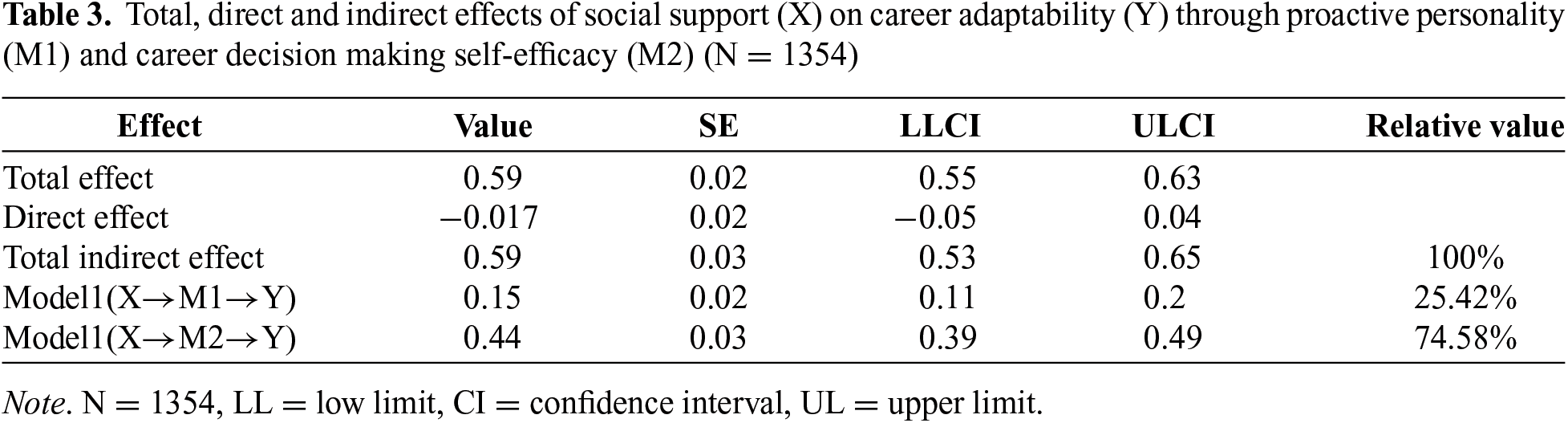

Next, a bootstrap procedure was employed to test the significance of the mediating effects within this multiple mediation model (see Fig. 1). The results showed that neither the mediating path through proactive personality nor the path through career decision-making self-efficacy included zero in their 95% confidence intervals (β = 0.15, 95% CI = [0.11, 0.20]; β = 0.44, 95% CI = [0.39, 0.49]),as parallel mediating variables, each mediating path was significant simultaneously, indicating that both mediators significantly accounted for the relationship between social support and career adaptability. Interestingly, the indirect effects accounted for nearly 100% of the total effect of social support on career adaptability, highlighting the substantial contribution of these mediators to the explained variance in this model. The effect sizes and proportions for each mediating path relative to the total effect are presented in Table 3. Thus, Hypotheses 1 and 2 are supported.

Figure 1: The pathway of the multiplemediating model. Note: ***p < 0.001.

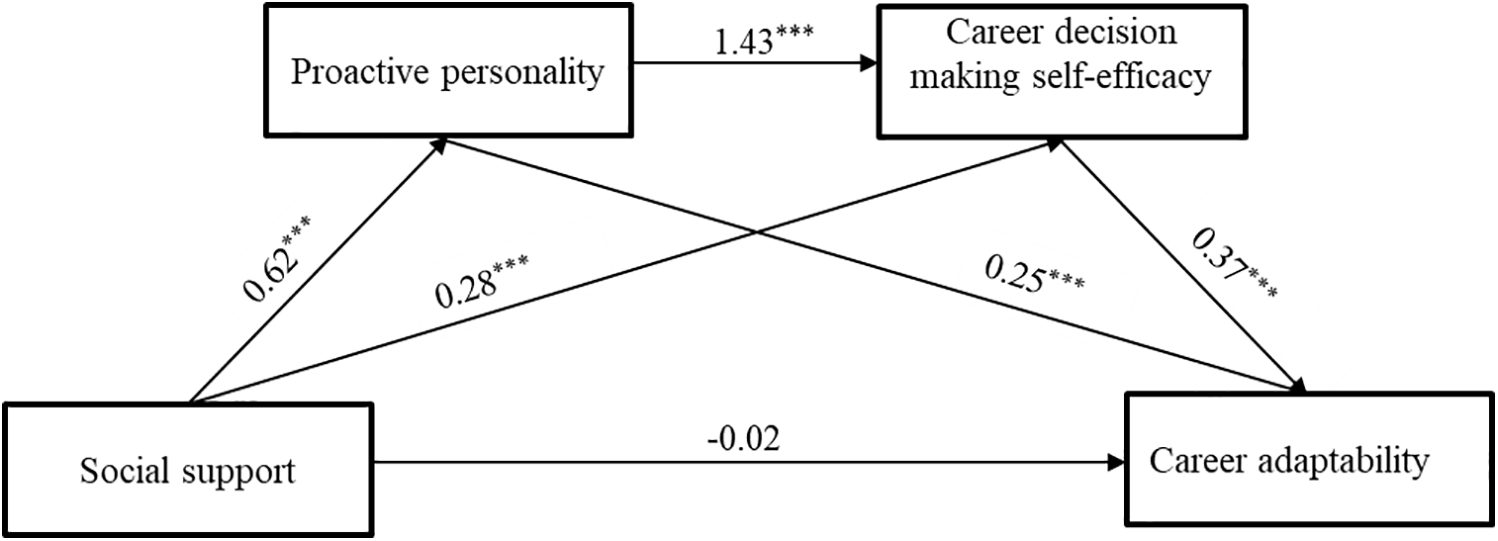

Chain mediation models of social support on career adaptability

To further investigate whether a chain-mediated model exists, that is, whether the effect of social support on career adaptability occurs sequentially through proactive personality and then through career decision-making self-efficacy, Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 6) was employed (Hayes, 2016, 2017). The detailed results are presented in Table 4 and Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The pathway of the chain mediating model. Note: ***p < 0.001.

The results revealed a significant positive predictive relationship between social support (β = 0.62, t = 42.45, p < 0.001) and proactive personality (β = 0.28, t = 5.94, p < 0.001), as well as with career decision-making self-efficacy. Meanwhile, both proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy positively predicted career adaptability (β = 0.25, t = 7.45, p < 0.001; β = 0.37, t = 28.70, p < 0.001). Consistent with our previous findings, once proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy were included in the model, the direct effect of social support on career adaptability became non-significant (β = −0.02, t = −0.72, p = 0.942).

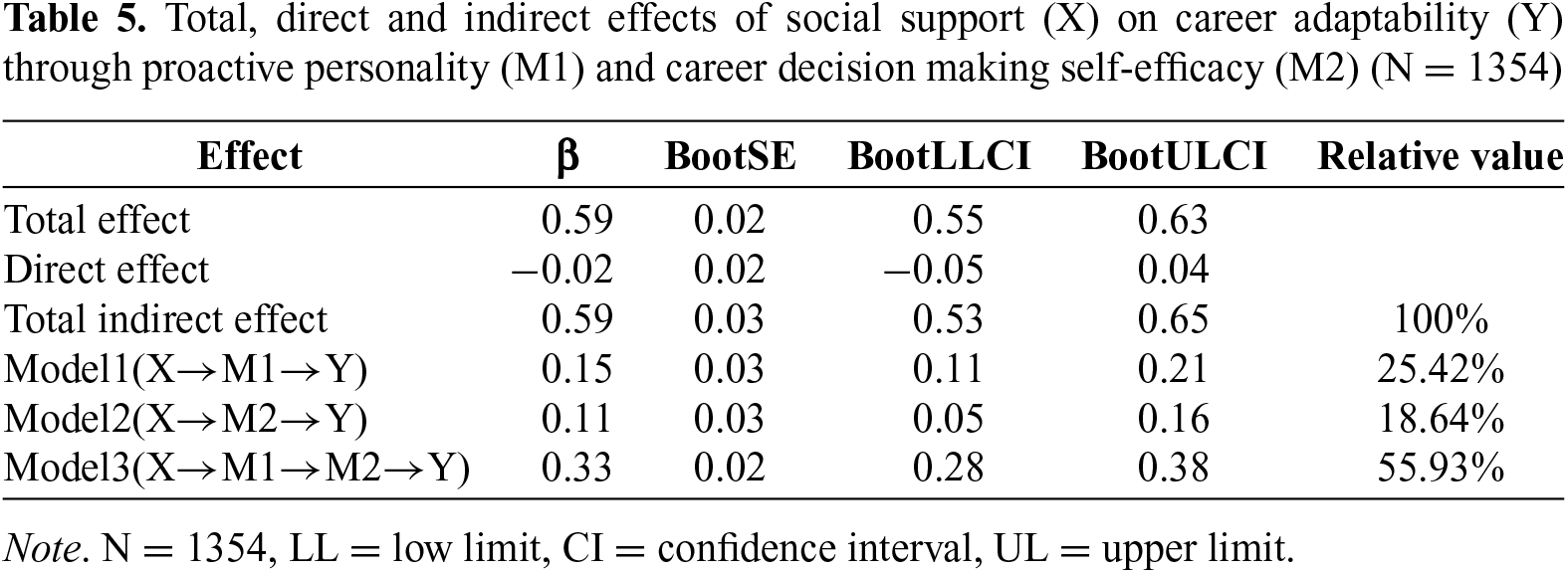

After conducting 5000 bootstrap resamples, it was determined that the indirect effects fall outside the 95% confidence intervals (β = 0.59, 95% CI = [0.53, 0.65]), confirming the significance of the mediation effects, as shown in Table 5. Specifically, the mediation pathways were as follows:

(1) Through proactive personality, which exerted an effect of 0.15, representing 25.42% of the total effect, with a 95% confidence interval [0.11, 0.21], excluding zero (M1);

(2) Through career decision-making self-efficacy, which exhibited an effect of 0.11, accounting for 18.64% of the total effect, with a confidence interval [0.05, 0.16], excluding zero (M2);

(3) A significant chained mediation pathway wherein social support influences career adaptability first through proactive personality and subsequently via career decision-making self-efficacy. This pathway had an effect of 0.33, with a 95% confidence interval [0.28, 0.38], excluding zero, and accounted for 55.93% of the total effect (M3). The confidence interval for the direct effect from social support to career adaptability was [−0.05, 0.04], which includes zero, indicating that the direct effect was no longer significant.

Finally, based on the above results, it can be concluded that the influence of social support on career adaptability is completely mediated through the chain pathway, supporting Hypothesis 3.

Career adaptability is widely regarded as a vital resource that enables individuals to effectively manage current and future vocational development tasks, occupational transitions, and associated challenges (Savickas et al., 2005, p. 52). Grounded in career capital theory, our study investigates the combined influence of social capital and psychological capital—two fundamental forms of career resources—on career adaptability. To our knowledge, previous research has examined the effects of social capital and psychological capital on career development separately (Hou et al., 2014, 2019); however, this is the first study to explore their joint impact on career adaptability.

The findings demonstrate that social support, a key component of social capital, is positively associated with increased career adaptability among college students. This relationship can be explained by social norms and reciprocal exchanges, which help maintain the vitality of social networks (Wang et al., 2019). Previous studies have shown that higher levels of social support from parents, friends, and significant others are positively correlated with better career adaptability in university students (Öztemel & Yıldız-Akyol, 2021), indicating that greater social resources facilitate adaptive capacity.

Furthermore, this research reveals that proactive personality mediates the relationship between social support and career adaptability. Psychological capital, a stable personality trait centered on self-esteem and locus of control, influences work ethics, beliefs, attitudes, and cognition (Goldsmith et al., 1997; Nolzen, 2018). Proactive individuals are more likely to create opportunities and actively pursue their career goals (Fawehinmi & Yahya, 2018; Hu et al., 2018, 2021). The results suggest that social support enhances career adaptability indirectly by positively impacting proactive personality.

Meanwhile, this study also shows that career decision-making self-efficacy acts as a mediator in the relationship between social support and career adaptability. Previous research has indicated that social support improves career adaptability (Ataç et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022; Öztemel & Yıldız-Akyol, 2021), and that perceived psychological capital, particularly self-efficacy, significantly influences career preparation behaviors (Jun & Song, 2014). This study further demonstrates that social support indirectly boosts college students’ career adaptability through its effect on their career decision-making self-efficacy.

More importantly, this study found that social support influences career adaptability through a comprehensive pathway: social support positively impacts proactive personality, which subsequently enhances career decision-making self-efficacy, ultimately benefiting career adaptability. This chain-mediated pathway is essential for understanding the role of social support in fostering career adaptability. Previous research has suggested that social support can indirectly improve career decision-making self-efficacy through an individual’s proactive personality (Preston & Salim, 2019). Individuals with high levels of proactivity are more likely to take actions that influence their environment, thereby increasing their career decision-making self-efficacy (Xin et al., 2020), consistent with our findings.

Implications for theory, research, and practice

Our results confirm that applying the career capital theory to the field of career adaptability is appropriate for exploring how individuals adapt to their careers through the integration of social capital and psychological capital. Our specific findings reveal that both social capital and psychological capital significantly influence college students’ career adaptability. Although social support is indeed essential for students to achieve their desired career outcomes, the components of psychological capital—namely, proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy—are equally crucial in facilitating individuals’ adaptation to the dynamic challenges of career transitions.

This study further advances the understanding of career capital transformation (Arthur et al., 1999) by uncovering the complete pathway through which social capital and psychological capital influence career adaptability. Given that previous research has seldom addressed the combined impact of social capital and psychological capital on individual career development, the significant contribution of this study lies in revealing how social support, a key element of social capital, can influence career decision-making self-efficacy via proactive personality, a core component of psychological capital, ultimately promoting the development of career adaptability.

The strong correlation between career decision-making self-efficacy and proactive personality has a profound impact on career development, offering valuable insights for future strategies to enhance career adaptability. This suggests that fostering proactive personalities and strengthening career decision-making self-efficacy can be effective approaches for improving individuals’ capacity to succeed in their careers.

The findings also provide practical guidance for universities to design comprehensive career counseling programs that incorporate both social capital and psychological capital. For instance, this approach recognizes the interplay of individual, social, and psychological factors in shaping career trajectories and offers actionable strategies to foster successful career development.

Limitations and future directions

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study that should be addressed in future research: Firstly, the current study employed a cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inferences. Future studies could adopt a longitudinal approach to examine the temporal dynamics among the four variables, thereby providing more robust evidence for the study’s conclusions. Secondly, the sample consisted solely of university students, which limits the extensibility of the findings. Future research could expand the sample to include a more diverse demographic, such as working professionals or individuals at different career stages. Lastly, while this study emphasized social capital and psychological capital within the framework of the career capital theory, it did not extensively explore human capital. Future investigations could incorporate human capital as a key variable to further validate and enrich the explanatory power of the career capital framework.

This study explored how social and psychological capital factors impact career adaptability. Students who possess or perceive less social support, fostering their proactive personality and enhancing their career decision-making self-efficacy can assist in improving their career adaptability. Social support is capital for career adaptability through with proactive personality and career decision-making self-efficacy. This process works through a chain mediation model: social support → proactive personality → career decision-making self-efficacy → career adaptability. According to this model, career capital can be understood as the relevant social networks and resources that assist individuals in continuously fulfilling career tasks and moving towards career success consequently, an integrated consideration of both social capital and psychological capital is essential for guiding university students entering or newly entered into the workforce self-managing career transitions effectively.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that helped improve the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by “Planning Subject for the 14th Five Year Plan of National Education Sciences of China (DBA210296)”.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhijun Liu; data collection: Jiaxin Liang; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhijun Liu; draft manuscript preparation: Zhijun Liu and Jiaxin Liang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original data presented in this study are openly accessible from the publicly available repository (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DSHPX).

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Changchun University of Science and Technology (24-012).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Aguirre-Urreta, M. I., & Hu, J. (2019). Detecting common method bias: Performance of the Harman’s single-factor test. In: ACMSIGMIS database: The DATABASE for advances in information systems (vol. 50, pp. 45–70). https://doi.org/10.1145/3330472.3330477 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Angeline, J. (2021). Influence of perceived social support on career decision-making self efficacy among undergraduate students. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education (TURCOMAT), 12(7), 1824–1829. [Google Scholar]

Arthur, M. B., Claman, P. H., & DeFillippi, R. J. (1995). Intelligent enterprise, intelligent careers. Academy of Management Perspectives, 9(4), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1995.9512032185 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arthur, M. B., Pringle, J. K., & Inkson, J. H. (1999). The new careers: Individual action and economic change. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

Ataç, L. O., Dirik, D., & Tetik, H. T. (2018). Predicting career adaptability through self-esteem and social support: A research on young adults. International Journal For Educational and Vocational Guidance, 18(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-017-9346-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Avey J. B., Luthans F., & Jensen S. M. (2009). Psychological capital: A positive resource for combating employee stress and turnover. Human Resource Management, 48(5), 677–693. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20294 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational behavior: A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030140202 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beigi, M., Shirmohammadi, M., & Arthur, M. (2018). Intelligent career success: The case of distinguished academics. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 107(4), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.05.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Betz, N. E. (2007). Career self-efficacy: Exemplary recent research and emerging directions. Journal of Career Assessment, 15(4), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707305759 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In: J. G. Richardson, (Ed.Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (pp. 241–258New York, NY: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

Chen, H., Fang, T., Liu, F., Pang, L., Wen, Y. et al. (2020). Career adaptability research: A literature review with scientific knowledge mapping in web of science. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Choi H. J., & Jung K. I. (2018). Moderating effects of career decision-making self-efficacy and social support in the relationship between career barriers and job-seeking stress among nursing students preparing for employment. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 24(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2018.24.1.61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dickmann, M., Suutari, V., Brewster, C., Mäkelä, L., Tanskanen, J. et al. (2018). The career competencies of self-initiated and assigned expatriates: Assessing the development of career capital over time. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(16), 2353–2371. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1172657 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ehsan, A., Klaas, H. S., Bastianen, A., & Spini, D. (2019). Social capital and health: A systematic review of systematic reviews. SSM-population Health, 8(5), 100425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fawehinmi, O. O., & Yahya, K. K. (2018). Investigating the linkage between proactive personality and social support on career adaptability amidst undergraduate students. Journal of Business and Social Review in Emerging Economies, 4(1), 81–92. https://doi.org/10.26710/jbsee.v4i1.370 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ghosh, A., & Fouad, N. A. (2017). Career adaptability and social support among graduating college seniors. The Career Development Quarterly, 65(3), 278–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12098 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Goldsmith, A. H., Veum, J. R., & Darity, W.Jr (1997). The impact of psychological and human capital on wages. Economic Inquiry, 35(4), 815–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1997.tb01966 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Grözinger, A. C., Wolff, S., Ruf, P. J., & Moog, P. (2022). The power of shared positivity: Organizational psychological capital and firm performance during exogenous crises. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 689–716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00506-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hamzah, S. R. A., Kai Le, K., & Musa, S. N. S. (2021). The mediating role of career decision self-efficacy on the relationship of career emotional intelligence and self-esteem with career adaptability among university students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 26(1), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2021.1886952 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2016). The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS. Processmacro.Org. Available online: http://www.processmacro.org/index.html (accessed August 20, 2020). [Google Scholar]

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

Hiester, M., Nordstrom, A., & Swenson, L. M. (2009). Stability and change in parental attachment and adjustment outcomes during the first semester transition to college life. Journal of College Student Development, 50(5), 521–538. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hirschi, A. (2012). The career resources model: An integrative framework for career counsellors. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 40(4), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.700506 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hou, Z. J., Leung, S. A., Li, X., Li, X., & Xu, H. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale—China form: Construction and initial validation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hou, C., Wu, L., & Liu, Z. (2014). Effect of proactive personality and decision-making self-efficacy on career adaptability among Chinese graduates. Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal, 42(6), 903–912. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.6.903 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hou, C., Wu, Y., & Liu, Z. (2019). Career decision-making self-efficacy mediates the effect of social support on career adaptability: A longitudinal study. Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal, 47(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.8157 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hu, X., He, Y., Ma, D., Zhao, S., Xiong, H. et al. (2021). Mediating model of college students’ proactive personality and career adaptability. The Career Development Quarterly, 69(3), 216–230. [Google Scholar]

Hu, R., Wang, L., Zhang, W., & Bin, P. (2018). Creativity, proactive personality, and entrepreneurial intention: The role of entrepreneurial alertness. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 335323. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Huang, S., Yu, Z., Shao, Y., Yu, M., & Li, Z. (2021). Relative effects of human capital, social capital and psychological capital on hotel employees’ job performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(2), 490–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2020-0650 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jun, J. Y., & Song, B. K. (2014). Influences of the positive psychological capital perceived by adolescents on career barriers and career preparation behaviors. Korean Journal of Youth Studies, 21(3), 171–200. [Google Scholar]

Lazarova, M., & Taylor, S. (2009). Boundaryless careers, social capital, and knowledge management: Implications for organizational performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 30(1), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.545 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, P. C., Xu, S. T., & Yang, W. (2021). Is career adaptability a double-edged sword? The impact of work social support and career adaptability on turnover intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94(1), 102875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, T., Tien, H. L. S., Gu, J., & Wang, J. (2022). The relationship between social support and career adaptability: The chain mediating role of perceived career barriers and career maturity. International Journal For Educational and Vocational Guidance, 23(2), 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09515-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Martínez, I. M., Youssef-Morgan, C. M., Chambel, M. J., & Marques-Pinto, A. (2019). Antecedents of academic performance of university students: Academic engagement and psychological capital resources. Educational Psychology, 39(8), 1047–1067. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1623382 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nasurdin, A. M., Ling, T. C., & Khan, S. N. (2018). The role of psychological capital on nursing performance in the context of medical tourism in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Society, 19(3), 748–761. [Google Scholar]

Nolzen, N. (2018). The concept of psychological capital: A comprehensive review. Management Review Quarterly, 68(3), 237–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-018-0138-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ozturk, A., & Karatepe, O. M. (2019). Frontline hotel employees’ psychological capital, trust in organization, and their effects on nonattendance intentions, absenteeism, and creative performance. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(2), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2018.1509250 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Öztemel, K., & Yıldız-Akyol, E. (2021). The predictive role of happiness, social support, and future time orientation in career adaptability. Journal of Career Development, 48(3), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845319840437 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peng, Y. X., & Long, L. R. (2001). Study on the scale of career decision-making self-efficacy for university students. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 2, 38–43. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-6020.2001.02.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Preston, M., & Salim, R. M. A. (2019). Parenting style, proactive personality, and career decision self-efficacy among senior high school students. Humanitas, 16(2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.26555/humanitas.v16i2.12174 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rossier, J. (2015). Career adaptability and life designing. In: L. Nota, & J. Rossier, (Eds.Handbook of the Life Design Paradigm: From Practice to Theory, from Theory to Practice (pp. 153–168Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

Savickas, M. L., Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In: R.W. Lent, & Brown S. D. (Eds.Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 42–70Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shang, J., & Gan, Y. (2009). Analysis of the effects of the proactive personality on graduates’ career decision-making self-efficacy. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis, 45(3), 548–554. https://doi.org/10.13209/j.0479-8023.2009.081 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sou, E. K., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2022). Career adaptability as a mediator between social capital and career engagement. The Career Development Quarterly, 70, 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12289 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tulin, M., Lancee, B., & Volker, B. (2018). Personality and social capital. Social Psychology Quarterly, 81(4), 295–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272518804533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, T., Long, L., Zhang, Y., & He, W. (2019). A social exchange perspective of employee-organization relationships and employee unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of individual moral identity. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(2), 473–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3782-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wilk, A. (2023). Career capital as a factor contributing to success on the labor market-a case study of a selected professional group. Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Administratio Locorum, 22(3), 433–446. https://doi.org/10.31648/aspal.8725 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wills, T. A. (1991). Social support and interpersonal relationships. In: M. S. Clark, (Ed.Prosocial Behavior (pp. 265–289Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

Xin, L., Tang, F., Li, M., & Zhou, W. (2020). From school to work: Improving graduates’ career decision-making self-efficacy. Sustainability, 12(3), 804. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030804 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xu, Q., Zhang, C., Cui, Y., Hu, X., & Yu, S. (2023). Career capital and well-being: The moderating role of career adaptability and identity of normal student. Social Indicators Research, 169(1), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-023-03157-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools