Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Speak up in a safe space: The role of inclusive leadership and collectivism in fostering upward voice

1 School of Economics and Management, Zhongshan Polytechnic, Zhongshan, 528404, China

2 School of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, 100871, China

* Corresponding Author: Lei Lu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 309-317. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068580

Received 09 September 2024; Accepted 10 April 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study examined the relationship between inclusive leadership and subordinates’ upward voice, focusing on the mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of collectivism. Data were collected from 284 subordinates and supervisors across 11 organizations in China in three cross-lagged waves. Structural equation modeling results indicated that inclusive leadership was associated with subordinates’ upward voice via psychological safety. Moreover, collectivism strengthens the association between inclusive leadership and upward voice via psychological safety, leading to a higher upward voice. These findings highlight the importance of inclusive leadership in fostering an environment that promotes open communication and psychological safety between supervisors and subordinates, ultimately enhancing workplace health and well-being. The implications of these findings suggest that management practices should cultivate inclusive leadership behaviors for enhancing psychological safety, and encouraging subordinates to voice their opinions for the overall success of the organization.Keywords

Inclusive leadership emphasizes valuing employees’ priorities, fostering inclusivity, and promoting collaborative partnerships (Carmeli et al., 2010; Korkmaz et al., 2022; Randel et al., 2018). When employees perceive that they are included in managerial practices, they are more likely to engage in extra-role behaviors that enhance organizational innovation and adaptability to environmental changes (Liu et al., 2017, 2024; Kao et al., 2021), ultimately improving organizational performance (Hughes et al., 2019; Stoner et al., 2011). Furthermore, employees who feel included in workplace decision-making believe they have a voice in organizational processes and are more likely to respond proactively to advance their organizations (Liu et al., 2017; King et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2021). Inclusive leadership encourages diverse perspectives and active engagement (Shore & Chung, 2022; Van Knippenberg & van Ginkel, 2022), fostering employees’ sense of value as integral team members and enhancing their psychological safety. However, in hierarchical collectivist cultural settings, employees may prefer to remain silent rather than voice their opinions (Li & Xing, 2021; Morrison et al., 2011; Weiss & Morrison, 2019; Wilkinson et al., 2020), and the impact of inclusivity on leadership dynamics in such contexts remains underexplored. This study investigates the qualities of workplace inclusivity that promote employee voice behavior in Chinese collectivist cultural settings.

Inclusive Leadership and Collectivist Culture. Inclusive leadership, a distinct form of relational leadership, emphasizes openness, accessibility, and availability in interactions with employees (Carmeli et al., 2010). Inclusive leaders value employees’ unique attributes and contributions, actively involving them in organizational decision-making to enhance their sense of participation and belonging (Nishii & Leroy, 2022; Roberson & Perry, 2022). This leadership style involves actively listening to employees, appreciating their contributions, and encouraging diverse perspectives, which reduces anxiety and perceived risks (Carmeli et al., 2010; Nishii & Leroy, 2022). According to psychological safety theory (Edmondson, 1999), employees who feel psychologically safe believe they can express opinions or suggestions without fear of punishment or negative consequences (Milliken et al., 2003; Sherf et al., 2021). This sense of safety increases the likelihood of employees offering innovative ideas and constructive feedback (Edmondson & Lei, 2014). Inclusive leadership, marked by behaviors that invite and appreciate input (Korkmaz et al., 2022), reinforces employees’ psychological safety (Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006; Zhao et al., 2023). Thus, inclusive leadership fosters an open, trusting environment that encourages upward voice, promoting organizational innovation and development.

To foster upward voice, inclusive leadership must first establish an environment of trust and freedom from fear of punishment, enabling employees to feel safe expressing suggestions. Employees are more likely to offer upward suggestions when psychological safety is assured. For instance, Carmeli et al. (2010) find that inclusive leadership enhances employees’ psychological safety, which promotes upward voice behavior.

Although inclusive leadership creates a supportive environment, collectivist orientation can both encourage and suppress upward voice behavior (Morrison et al., 2011; Weiss & Morrison, 2019). Collectivism emphasizes group well-being, which may encourage employees to offer suggestions benefiting the organization (Farooq et al., 2014; Rego & Cunha, 2009). However, the desire to avoid conflict and maintain harmony may prevent individuals from raising concerns or dissenting opinions, even in an inclusive environment (Li & Xing, 2021; Wilkinson et al., 2020). Therefore, understanding and addressing these cultural factors enables leaders to navigate the complexities of collectivism. Knowing how inclusive leadership fosters psychological safety and encourages upward voice is crucial for both theory and practice.

Employee Voice Behavior and Psychological Safety. When employees feel psychologically safe, they are more willing to express upward voice, believing their input benefits both the group and the organization (Morrison, 2011; 2014), rather than solely serving personal interests (Lu et al., 2024). Psychological safety refers to employees’ belief that they can speak up or raise concerns without fear of negative consequences (Edmondson, 1999). Inclusive leadership enhances this belief by fostering a supportive environment where employees feel valued (Nishii & Leroy, 2022). Psychological safety theory suggests that when employees feel secure, they are empowered to express ideas freely without fear of retaliation (Carmeli et al., 2010; Detert & Burris, 2007).

Theoretical Foundations. Social exchange theory (SET) offers a strong framework for explaining how inclusive leadership shapes employee upward behavior via psychological safety. SET suggests that social behavior results from an exchange process where individuals assess the potential benefits and risks of their actions in relationships (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). In organizations, this theory suggests that leader-employee interactions are based on reciprocity, trust, and mutual benefit (Cropanzano et al., 2017). When leaders foster inclusivity through openness, accessibility, and appreciation for diverse contributions (Randel et al., 2018), they create an environment that encourages employees to reciprocate with positive behaviors, including voice behavior (Grant, 2013; Randel et al., 2016). SET suggests that when employees perceive their leaders as investing in them by fostering a supportive and inclusive environment, they feel obligated to reciprocate (Jolly & Lee, 2021; Sherf et al., 2021). According to SET, when employees see that their leaders are investing in them by fostering a supportive, inclusive environment (Shore & Chung, 2022), they tend to feel obligated to reciprocate (Jiang et al., 2022). This reciprocation typically manifests as increased engagement, particularly a willingness to voice concerns and suggestions that drive organizational improvement. Moreover, this reciprocity shows in employee willingness to voice concerns and suggestions for organizational improvement. Moreover, social exchange theory (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005) posits that leader-employee interactions are grounded in reciprocal trust and support (Kilroy et al., 2023). When leaders show respect, support, and recognition, employees tend to reciprocate with positive behaviors, such as voice behavior (Blau, 1964). Inclusive leaders, through their openness and inclusive actions (Carmeli et al., 2010; Roberson & Perry, 2022), boost employees’ psychological safety, increasing their confidence that suggestions will be well-received and contribute to organizational improvement.

Moderating Effect of Collectivism. Collectivism is a pivotal dimension in cultural classification, with China commonly regarded as a quintessential collectivist nation (Hofstede, 2011). In China, organizations must consider collectivism as a critical factor when managing and promoting upward voice behavior (Morrison et al., 2011; Lu et al., 2024). Collectivism emphasizes interpersonal relationships, collective goals, and team-oriented outcomes (Oyserman et al., 2002).

In collectivist cultures, where harmony and collective goals are paramount (Ng et al., 2019; Oyserman et al., 2002), employees are likely to trust inclusive leaders and focus on team success (Marcus & Le, 2013; Lu et al., 2024), which enhances their psychological safety. Moreover, in collectivist cultures, inclusive leadership is for collective harmony and success (Choi et al., 2017; Shore et al., 2018), with a focus role within the work team and contributions to collective performance (Bachrach et al., 2007; Walumbwa & Lawler, 2003). Employees with a high collectivist orientation value the collective good over individual interests (Moorman & Blakely, 1995; Rego & Cunha, 2009). They are more inclined to embrace inclusive leadership, as it emphasizes teamwork and the achievement of shared goals, fostering a sense of safety.

In highly collectivist cultures, employees place greater emphasis on reciprocal behavior and collective interests within the team (Eby & Dobbins, 1997; Erdogan & Liden, 2006). As a result, when feeling psychologically safe, they view upward suggestions as a way to reciprocate to the group and leadership. Since highly collectivist employees prioritize group success and long-term relationship maintenance (Oyserman et al., 2002), they are more likely to be motivated by psychological safety and engage in positive upward voice.

Collectivist culture employees are more concerned about aligning their opinions with collective expectations (Oyserman et al., 2002; Triandis, 2001), placing greater value on collective recognition from colleagues and leaders (De Clercq et al., 2019; Erdogan & Liden, 2006). Finally, employees with a strong collectivist orientation are more likely to consider collective interests in their decisions and behaviors (Farooq et al., 2014; Oyserman et al., 2002).

The Chinese work culture context

To understand how inclusive leadership influences follower upward voice in collectivist culture, we consider the practices in Chinese employer organization (Li & Sun, 2015; Liu et al., 2017). In Chinese culture, Confucianism and collectivism significantly influence organizational management (Marcus & Le, 2013; Warner, 2010). Confucian philosophy promotes harmony and cooperation, highlighting the role and responsibility of individuals in society and organizations (Chu & Moore, 2020; Li, 2006). In this cultural context, employees tend to prioritize relationships, avoid conflict, and show greater obedience, especially when interacting with leaders (Lin et al., 2013). Employees in collectivist cultures, like China, often prioritize harmony and group cohesion (Chen et al., 2016; Marcus & Le, 2013), which influences their willingness to engage in upward voice behavior. Consequently, Chinese employees are more cautious about expressing their opinions, particularly when dealing with superiors (Morrison, 2011; Morrison et al., 2011).

Goal of the study. This study examines the relationship between inclusive leadership and subordinates’ upward voice, focusing on the mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of collectivism. We examined how collectivism moderate employee upward voice or willingness to express thoughts and suggestions with psychological safety, believing their suggestions will promote group harmony and success without causing conflict or negative evaluations from the group.

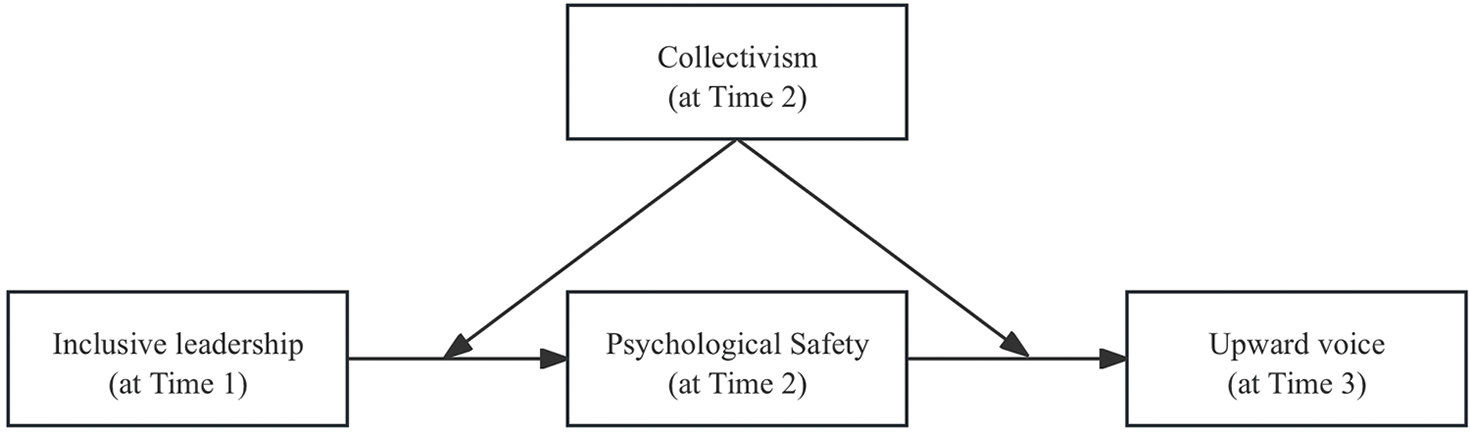

Based on social exchange theory and psychological safety theory, we propose that inclusive leadership enhances subordinates’ psychological safety, we tested the following hypotheses (see Figure 1):

Figure 1: Theoretical model of the study. Note. Inclusive leadership behavior = rated by subordinates; Subordinates’ psychological safety and collectivism = rated by subordinates; Subordinates’ upward voice = rated by supervisors.

H1: Psychological safety mediates the relationship between inclusive leadership and subordinates’ upward voice for higher upward voice of the subordinates.

H2: Collectivism moderates the relationship between inclusive leadership and to be higher psychological safety.

H3: Collectivism moderates the relationship between psychological safety and subordinates’ upward voice for higher subordinates’ upward voice.

H4: Collectivism moderates the indirect effect of inclusive leadership on subordinates’ upward voice to be stronger.

Participants and setting. The study were 400 subordinates and their corresponding 400 supervisors matched one-to-one, and from various Eastern China industries, including banking, retail, and technology. We sampled them on two occasions resulting with 397 responses at time 1, and 355 at time 2.

Among these subordinates, 50% were male, with an average age of 39.65 years (SD = 4.80). Additionally, 76.1% had a college degree or higher, and the average job tenure was 9.77 years (SD = 4.65). Among these team supervisors, 51% were male and 94% were married, with an average age of 44.7 years (SD = 5.56). Additionally, 77.8% had a college degree or higher, and the average supervisor job tenure was 8.92 years (SD = 5.13).

Measures. We used scales that had been previously validated in the Chinese context with Brislin’s (1986) back translation procedures. Survey items were on a five-point Likert-type options, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Inclusive leadership. At Time 1, subordinates were asked to evaluate their supervisors’ inclusive leadership using 9-item scale from Carmeli et al. (2010). A sample item is “My supervisor is accessible for discussing emerging problems”. The Cronbach’s alpha for inclusive leadership scale scores was 0.926.

Psychological safety. At Time 2, subordinates self-evaluated their psychological safety using the 5-item scale developed by May et al. (2004). A sample item is “It is important for me to evaluate the things that I do”. The Cronbach’s alpha for psychological safety scale scores was 0.907.

Collectivism. At Time 2, subordinates were asked to evaluate their collectivism using 5-item scale from Bachrach et al. (2007). A sample item is “To make people realize that sometimes, to be part of a working group, I have to do things I don’t want to do”. The Cronbach’s alpha for collectivism scale scores was 0.916.

Upward voice. Team supervisors were asked to evaluate their subordinates s’ upward voice using 3-item scale from Liu et al. (2017). A sample item is “expressed his/her opinions to me, which are different from mine”. The Cronbach’s alpha for upward voice scale scores was 0.781.

Control variables. We controlled for work tenure among subordinates because it has been shown to be related to upward voice behaviors (e.g., Liu et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2021). Additionally, we controlled for age, gender, and education level in this study because prior research has demonstrated that these variables impact upward voice (Davidson et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2022).

The Research Ethics Committee of the Zhongshan Polytechnic approved the study (ID: ZP2024-10-0012). All participants read the questionnaire’s preamble and gave their informed consent. The employer organizations granted study permission, The employees consented to the We implemented a coding scheme to assign each participant a unique code, ensuring the confidentiality of all subordinate responses. Data were collected using WeChat, the most popular social communication tool in China.

We employed structural equation modeling (SEM) with bootstrapping to test our proposed hypotheses, utilizing Mplus v8.4 (Cheung et al., 2021). Since our theoretical model outlines pathways between multiple independent and dependent variables, we adopted an observed variable SEM approach. In this approach, the score for each independent variable was calculated as the mean of its corresponding items (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011). To test the hypothesized mediating and moderated mediation relationships, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations to estimate their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using Mplus software with 10,000 iterations.

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using Mplus v8.4 to examine the convergent and discriminant validity of a measurement model comprising four latent factors with 22 indicators: nine items for inclusive leadership, five items for psychological safety, five items for collectivism, and three items for upward voice. The CFA results are presented in Table 1. The proposed four-factor model demonstrated good goodness-of-fit indices (χ²/df = 1.19, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.03, and all factor loadings exceeded 0.70). Comparing the hypothetical model with the other three models, the model fit indices and the results of the two difference tests in Table 1 indicated that the hypothetical model fit better than the others, supporting acceptable discriminant validity in our study. Additionally, these results suggested that common method variance (CMV) was not an issue in this study (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for each variable, including the means and standard deviations. Consistent with our hypotheses, inclusive leadership is positively related to upward voice (r = 0.16, p < 0.01), and psychological safety significantly correlates with upward voice (r = 0.47, p < 0.001), as we proposed. Furthermore, we tested all hypotheses using structural equation modeling, which allows us to estimate all proposed paths simultaneously.

Figure 2 shows that the relationship between inclusive leadership and psychological safety is significant (B = 0.40, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001), as is the relationship between psychological safety and upward voice (B = 0.37, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001). Additionally, Table 3 presents the path from inclusive leadership to upward voice via psychological safety (B = 0.15, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.10, 0.20]). Thus, the hypothesis 1 was supported.

Figure 2: Model path coefficient diagram of the study. Note. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01.

Figure 2 shows that collectivism moderates the positive relationship between inclusive leadership and psychological safety (B = 0.15, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001). To clarify the interaction effect, we followed the procedures proposed by Aiken et al. (1991) and plotted the interaction using cut values of one standard deviation above and below the mean of collectivism (see Figure 3). Additionally, Table 3 shows that inclusive leadership is more positively related to psychological safety at high levels of collectivism (B = 0.56, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.43, 0.69]) than at low levels (B = 0.24, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.11, 0.37]). Thus, the hypothesis 2 was supported.

Figure 3: Moderating effect of collectivism on the relationship of inclusive leadership and psychological safety

Similarly, Figure 2 shows that collectivism moderates the positive relationship between psychological safety and upward voice (B = 0.13, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01). Additionally, Table 3 shows that psychological safety is more positively related to upward voice at high levels of collectivism (B = 0.50, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.36, 0.64]) than at low levels (B = 0.23, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.10, 0.36]) (see Figure 4). Thus, the hypothesis 3 was supported.

Figure 4: Moderating effect of collectivism on the relationship of psychological safety and upward voice

We calculated the indirect mediation effect of psychological safety at varying levels of collectivism. Table 3 shows that the indirect impact of inclusive leadership on upward voice through psychological safety is significant at both low and high levels of collectivism (B = 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.01, 0.12] at low levels; B = 0.28, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.20, 0.37] at high levels). Thus, the hypothesis 4 was supported.

First, we found that psychological safety mediates the link between inclusive leadership and upward voice (Edmondson, 1999). Our findings confirmed that when leaders create a psychologically safe environment, employees feel more comfortable voicing their opinions and ideas without fear of negative repercussions, supporting Edmondson’s (1999) theory. This study contributed to the growing body of literature by further emphasizing the importance of inclusive leadership in fostering an environment conducive to open communication and employee engagement.

Second, the study found that collectivism enhances the positive link between inclusive leadership and upward voice via psychological safety. In collectivist cultures, such as China, employees prioritize group harmony and collective success (Chen et al., 2021; Schwartz, 1990). As a result, when inclusive leaders show openness and accessibility (Nishii & Leroy, 2022), it boosts psychological safety, encouraging employees to voice their opinions for the benefit of the collective. This finding underscored the importance of cultural context in understanding leadership effectiveness, particularly in cultures where collectivism is a fundamental value.

Additionally, the study suggested that collectivism not only supports but also amplifies the impact of inclusive leadership on upward voice by strengthening the role of psychological safety. Employees in collectivist cultures are more likely to view their contributions as benefiting the group, making them more inclined to speak up when they feel their voices will be valued (Zare & Flinchbaugh, 2019).

Implications for theory, research and practice

This study makes several significant contributions to the literature on inclusive leadership, psychological safety, collectivism, and upward voice behavior. First, our study extends the application of social exchange theory (SET) by illustrating how inclusive leadership motivates employees to engage in upward voice through psychological safety. SET suggests that when leaders invest in trust, openness, and inclusivity (Carmeli et al., 2010; Nishii & Leroy, 2022; Roberson & Perry, 2022), employees are more likely to reciprocate with constructive behaviors such as voice. This perspective provides a clear explanation of the mechanism through which inclusive leadership promotes a culture of speaking up, where employees feel valued and confident in their contributions.

We extend the literature on inclusive leadership exploring the role of trusting and open environment for boosting employees’ psychological safety and in collectivist culture. HR managers should integrate psychological safety as a key criterion in performance evaluations and leadership assessments (Beltrán-Martín et al., 2023; Newman et al., 2017). Ensuring that leaders are results-driven and capable of creating a safe space for open communication can yield long-term benefits for organizational innovation and employee engagement (Kang & Sung, 2017). Training programs aimed at enhancing leaders’ abilities to foster psychological safety can create a more engaged and proactive workforce.

Practice implications for managers include a need to invest in leadership development programs that promote inclusive practices (Kuknor & Bhattacharya, 2022; Nishii & Leroy, 2022), such as being accessible, receptive to feedback, and valuing diverse perspectives (Randel et al., 2018; Roberson & Perry, 2022). This approach would enable managers to build a psychologically safe environment where employees feel empowered to share ideas and contribute to organizational success. In collectivist culture. Employer organizations should adapt their leadership practices to align with collectivist values by emphasizing team goals, collective success, and harmonious relationships (Marcus & Le, 2013; Saad et al., 2015).

Strengths, limitations and future research directions

Our use of time-lagged and multisource design helped mitigate concerns about common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Our design to use a month interval is in line with previous research on inclusive leadership (as rated by followers; Asghar et al., 2023; Ma & Tang, 2023). Furthermore, our data were collected from various companies to maximize the generalizability of the findings.

Despite its theoretical and practical implications, our study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to make strong causal inferences about the relationships between inclusive leadership, psychological safety, collectivism, and upward voice. Although structural equation modeling offers valuable insights into these relationships, future studies should use longitudinal or experimental designs to better establish the temporal order of constructs and validate causal pathways (Antonakis et al., 2010; Ployhart & Vandenberg, 2010). Second, focusing on Chinese organizations limits the generalizability of the findings to other cultural contexts. Since collectivism is a dominant cultural value in China, the findings may not directly apply to more individualistic cultures (e.g., Varma et al., 2009). Future studies should explore whether these relationships hold across different cultural settings, especially in individualistic societies where upward voice may be driven by other factors and leadership styles. Third, this study used social exchange theory and psychological safety theory to examine the mediating role of psychological safety (Cropanzano et al., 2017; Edmondson, 1999). Our work analyzes the influence of leadership on employee behavior from a static perspective, but fails to fully consider the influence of dynamic organizational environment and employee cognitive and emotional changes on these relationships. Therefore, future research should apply dynamic theory to explore how these factors evolve and interact over time (Clark et al., 2007; Gooty & Yammarino, 2016). Finally, our study did not explore potential boundary conditions beyond collectivism that may further moderate the relationships in the model. For example, individual traits like personality may influence how employees experience psychological safety and engage in upward voice behavior (Liang et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2017; Sherf et al., 2021). Future research should investigate these individual-level factors to enhance our understanding of how inclusive leadership promotes upward voice in diverse organizational settings.

This study found inclusive leadership to affected employee upward voice and noted the mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of collectivism in that relationship. Specifically, psychological safety mediated the effect of inclusive leadership on employee upward voice, and this mediation effect was moderated by collectivism. Moreover, the mediation effect was stronger when collectivism was high. Our study showed that inclusive leadership fosters a trusting and open environment, boosting employees’ psychological safety and encouraging them to voice their ideas without fear of negative repercussions.

Acknowledgement: This study was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Certificate Number: 2024M760126).

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Certificate Number: 2024M760126).

Author Contributions: Each author made significant contributions to this research project, including involvement in the conception, study design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, or other critical aspects of the study. All authors participated in drafting, revising, and critically reviewing the article, ultimately providing their approval for the version to be published. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Lei Lu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The Research Ethics Committee of the Zhongshan Poly-technic approved the study (ID: ZP2024-10-0012). All participants read the questionnaire’s preamble and gavetheir informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2010). On making causal claims: a review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 1086–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Asghar, M., Gull, N., Xiong, Z., Shu, A., Faraz, NA. et al. (2023). The influence of inclusive leadership on hospitality employees’ green innovative service behavior: A multilevel study. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 56(1), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.07.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bachrach, D. G., Wang, H., Bendoly, E., & Zhang, S. (2007). Importance of organizational citizenship behaviour for overall performance evaluation: Comparing the role of task interdependence in China and the USA. Management and Organization Review, 3(2), 255–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00071.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beltrán-Martín, I., Guinot-Reinders, J., & Rodríguez-Sánchez, A. M. (2023). Employee psychological conditions as mediators of the relationship between human resource management and employee work engagement. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(11), 2331–2365. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2022.2078990 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.1964.tb00583.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In: W. J. Lonner, J. W. Berry (Eds.Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

Carmeli, A., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Ziv, E. (2010). Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creativity Research Journal, 22(3), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2010.504654 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, C. C., Ünal, A. F., Leung, K., & Xin, K. R. (2016). Group harmony in the workplace: Conception, measurement, and validation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(4), 903–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-016-9457-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2021). Testing moderation in business and psychological studies with latent moderated structural equations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(6), 1009–1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09717-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Choi, S. B., Tran, T. B. H., & Kang, S. W. (2017). Inclusive leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of person-job fit. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(6), 1877–1901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9801-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, S., Fan, Y., Zhang, G., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Collectivism-oriented human resource management on team creativity: Effects of interpersonal harmony and human resource management strength. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(18), 3805–3832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1640765 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chu, I., & Moore, G. (2020). From harmony to conflict: MacIntyrean virtue ethics in a Confucian tradition. Journal of Business Ethics, 165(2), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04305-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Clark, TD.Jr, Jones, MC., & Armstrong, CP. (2007). The dynamic structure of management support systems: Theory development, research focus, and direction. MIS Quarterly, 31(3), 579–615. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148808 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E. L., Daniels, S. R., & Hall, A. V. (2017). Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 479–516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Davidson, T., Van Dyne, L., & Lin, B. (2017). Too attached to speak up? It depends: How supervisor-subordinate guanxi and perceived job control influence upward constructive voice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 143(2), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2017.07.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., & Azeem, M. U. (2019). Why happy employees help: How meaningfulness, collectivism, and support transform job satisfaction into helping behaviours. Personnel Review, 48(4), 1001–1021. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2018-0052 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.26279183 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eby, L. T., & Dobbins, G. H. (1997). Collectivistic orientation in teams: An individual and group-level analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18(3), 275–295. [Google Scholar]

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Erdogan, B., & Liden, R. C. (2006). Collectivism as a moderator of responses to organizational justice: Implications for leader-member exchange and ingratiation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.365 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Farooq, M., Farooq, O., & Jasimuddin, S. M. (2014). Employees response to corporate social responsibility: Exploring the role of employees’ collectivist orientation. European Management Journal, 32(6), 916–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2014.03.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gooty, J., & Yammarino, F. J. (2016). The leader-member exchange relationship: A multisource, cross-level investigation. Journal of Management, 42(4), 915–935. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313503009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Grant, A. M. (2013). Rocking the boat but keeping it steady: The role of emotion regulation in employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1703–1723. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0035 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hughes, D. E., Richards, K. A., Calantone, R., Baldus, B., & Spreng, R. A. (2019). Driving in-role and extra-role brand performance among retail frontline salespeople: Antecedents and the moderating role of customer orientation. Journal of Retailing, 95(2), 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.03.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jiang, J., Ding, W., Wang, R., & Li, S. (2022). Inclusive leadership and employees’ voice behavior: A moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 41(9), 6395–6405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01139-8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jolly, P. M., & Lee, L. (2021). Silence is not golden: Motivating employee voice through inclusive leadership. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(6), 1092–1113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020963699 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kang, M., & Sung, M. (2017). How symmetrical employee communication leads to employee engagement and positive employee communication behaviors: The mediation of employee-organization relationships. Journal of Communication Management, 21(1), 82–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-04-2016-0026 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kao, K. Y., Hsu, H. H., Thomas, C. L., Cheng, Y. C., Lin, M. T. et al. (2021). Motivating employees to speak up: Linking job autonomy, PO fit, and employee voice behaviors through work engagement. Current Psychology, 41, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01222-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Khan, N., Dyaram, L., & Dayaram, K. (2022). Team faultlines and upward voice in India: The effects of communication and psychological safety. Journal of Business Research, 142(3), 540–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kilroy, J., Dundon, T., & Townsend, K. (2023). Embedding reciprocity in human resource management: A social exchange theory of the role of frontline managers. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(2), 511–531. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12468 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

King, C., So, K. K. F., DiPietro, R. B., & Grace, D. (2020). Enhancing employee voice to advance the hospitality organization’s marketing capabilities: A multilevel perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91(7), 102657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102657 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Korkmaz, A. V., Van Engen, M. L., Knappert, L., & Schalk, R. (2022). About and beyond leading uniqueness and belongingness: A systematic review of inclusive leadership research. Human Resource Management Review, 32(4), 100894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100894 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kuknor, S. C., & Bhattacharya, S. (2022). Inclusive leadership: New age leadership to foster organizational inclusion. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(9), 771–797. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-07-2019-0132 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, C. (2006). The Confucian ideal of harmony. Philosophy East and West, 56, 583–603. https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2006.0055 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, X., & Xing, L. (2021). When does benevolent leadership inhibit silence? The joint moderating roles of perceived employee agreement and cultural value orientations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(7), 562–575. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-07-2020-0412 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, Y., & Sun, J. M. (2015). Traditional Chinese leadership and employee voice behavior: A cross-level examination. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.08.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0176 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, L. H., Ho, Y. L., & Lin, W. H. E. (2013). Confucian and Taoist work values: An exploratory study of the Chinese transformational leadership behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 113(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1284-8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, Y., Meng, L. M., Wang, H., & Chen, Y. (2024). Differential leadership and hospitality employees’ in-role performance: The role of constructive deviance and competitive climate. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 122(2), 103870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2024.103870 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, W., Song, Z., Li, X., & Liao, Z. (2017). Why and when leaders’ affective states influence employee upward voice. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 238–263. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.1082 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lu, L., Duan, J., Wu, W., & Ma, G. (2024). Exploring the dual impact of workplace gossip on employee voice behavior: A social identity perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 227(1), 112711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112711 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ma, Q., & Tang, N. (2023). Too much of a good thing: The curvilinear relation between inclusive leadership and team innovative behaviors. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 40(3), 929–952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09862-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marcus, J., & Le, H. (2013). Interactive effects of levels of individualism-collectivism on cooperation: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(6), 813–834. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1875 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1476. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00387 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moorman, R. H., & Blakely, G. L. (1995). Individualism-collectivism as an individual difference predictor of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160204 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.574506 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Morrison, E. W., Wheeler-Smith, S. L., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Speaking up in groups: A cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(7), 941–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.413 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Newman, A., Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ng, K. Y., Van Dyne, L., & Ang, S. (2019). Speaking out and speaking up in multicultural settings: A two-study examination of cultural intelligence and voice behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 151(1), 150–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2018.10.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nishii, L. H., & Leroy, H. (2022). A multi-level framework of inclusive leadership in organizations. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 683–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/10596011221111505 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128(1), 3–72. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ployhart, R. E., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2010). Longitudinal research: The theory, design, and analysis of change. Journal of Management, 36(1), 94–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309352110 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Randel, A. E., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., Chung, B., & Shore, L. (2016). Leader inclusiveness, psychological diversity climate, and helping behaviors. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(1), 216–234. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-04-2013-0123 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Randel, A. E., Galvin, B. M., Shore, L. M., Ehrhart, K. H., Chung, B. G. et al. (2018). Inclusive leadership: Realizing positive outcomes through belongingness and being valued for uniqueness. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.07.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2011). Introduction to psychometric theory. England, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Rego, A., & Cunha, M. P. (2009). How individualism-collectivism orientations predict happiness in a collectivistic context. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-007-9059-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Roberson, Q., & Perry, J. L. (2022). Inclusive leadership in thought and action: A thematic analysis. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 755–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/10596011211013161 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Saad, G., Cleveland, M., & Ho, L. (2015). Individualism-collectivism and the quantity versus quality dimensions of individual and group creative performance. Journal of Business Research, 68(3), 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.09.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schwartz, S. H. (1990). Individualism-collectivism: Critique and proposed refinements. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology, 21(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022190212001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sherf, E. N., Parke, M. R., & Isaakyan, S. (2021). Distinguishing voice and silence at work: Unique relationships with perceived impact, psychological safety, and burnout. Academy of Management Journal, 64(1), 114–148. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.1428 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shore, L. M., & Chung, B. G. (2022). Inclusive leadership: How leaders sustain or discourage work group inclusion. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 723–754. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601121999580 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shore, L. M., Cleveland, J. N., & Sanchez, D. (2018). Inclusive workplaces: A review and model. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.07.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stoner, J., Perrewé, P. L., & Munyon, T. P. (2011). The role of identity in extra-role behaviors: Development of a conceptual model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26(2), 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111102146 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tan, L., Wang, Y., & Lu, H. (2021). Leader humor and employee upward voice: The role of employee relationship quality and traditionality. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 28(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051820970877 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Van Knippenberg, D., & van Ginkel, W. P., (2022). A diversity mindset perspective on inclusive leadership. Group & Organization Management, 47(4), 779–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601121997229 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Varma, A., Pichler, S., Budhwar, P., & Biswas, S. (2009). Chinese host country nationals’ willingness to support expatriates: The role of collectivism, interpersonal affect and guanxi. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 9(2), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595808101155 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Walumbwa, F. O., & Lawler, J. J. (2003). Building effective organizations: Transformational leadership, collectivist orientation, work-related attitudes and withdrawal behaviours in three emerging economies. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(7), 1083–1110. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958519032000114219 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Warner, M. (2010). In search of confucian HRM: Theory and practice in greater China and beyond. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(12), 2053–2078. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.509616 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Weiss, M., & Morrison, E. W. (2019). Speaking up and moving up: How voice can enhance employees’ social status. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2262 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wilkinson A., Sun J‐M, K Mowbray P (2020). Employee voice in the Asia Pacific. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 58(4), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12274 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zare, M., & Flinchbaugh, C. (2019). Voice, creativity, and big five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Human Performance, 32(1), 30–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2018.1550782 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhao, F., Hu, W., Ahmed, F., & Huang, H. (2023). Impact of ambidextrous human resource practices on employee innovation performance: The roles of inclusive leadership and psychological safety. European Journal of Innovation Management, 26(5), 1444–1470. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-04-2021-0226 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools