Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Psychache and suicidal ideation among firefighters: The chain mediation effect of hopelessness and nostalgia

1 School of Education, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, 200234, China

2 School of Humanities/Department of College English Teaching, Hunan City University, Yiyang, 413000, China

3 School of Psychology, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, 200234, China

4 College of Information and Electronic Engineering, Hunan City University, Yiyang, 413000, China

5 Center for Mental Health Education, Hunan Software Vocational and Technical University, Xiangtan, 411100, China

6 Center for Mental Health Education and Counseling, Hunan Chemical Vocational Technology College, Zhuzhou, 412000, China

7 Department of Endocrinology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University, Shanghai, 200433, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yanyan Hu. Email: ; Yang He. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 419-427. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068039

Received 01 January 2025; Accepted 17 May 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study tested a chain mediation model on whether hopelessness and nostalgia play a mediating role in psychache and suicidal ideation of firefighters. A total of 652 firefighters participated in the survey (male = 94.94%; mean age = 23.71 years, SD = 4.18 years). The firefighters completed the Chinese Revised Psychache Scale (PAS), Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), Southampton Nostalgia Scale (SNS), and Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The path analysis results indicated that psychache positively predicted suicidal ideation. Hopelessness plays a significant mediating role between psychache and suicidal ideation further strengthening this relationship. In contrast, nostalgia mediates and weakened the relationship between psychache and suicidal ideation. Hopelessness and nostalgia jointly constructed a chain mediating effect between psychache and suicidal ideation, for higher suicidal ideation with higher hopelessness and lower nostalgia. The findings align with the Three-Step Theory of Suicide, which proposes that suicidal ideation results from the combination of pain and hopelessness and that connectedness is a key protective factor against escalating ideation. Therefore, interventions to reduce suicidal ideation in firefighters should aim to enhance their nostalgia, while reducing sense of hopelessness.Keywords

Firefighters need to be resilient to the vicissitudes of frequent exposure to hazardous physical, chemical, mechanical, and socio-psychological environments, which heightens their risks for premature mortality (Cuenca-Lozano & Ramírez-García, 2023). Some may result with psychache, a well-established risk factor for suicide (Cheng et al., 2021). Psychache refers to a lasting, unpleasant, and unsustainable feeling characterized by a perception of inability or deficiency of self (Meerwijk & Weiss, 2014). A meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of suicidal ideation among U.S. firefighters was as high as 46.8% (Stanley et al., 2016). Longitudinal studies found that the rate of suicidal ideation among U.S. female firefighters increased from 28.4% pre-service to 37.7% in-service (Stanley et al., 2017).

Firefighters may experience a sense of both hopelessness and psychache due to the hazards they are exposed to (Stanley et al., 2020). However, they may have a sense of nostalgia as a bittersweet emotion, which has been shown to enhance self-continuity and social connectedness (Sedikides et al., 2004; Tilburg et al., 2018). Yet the role of hopelessness and nostalgia in firefighters’ psychache and suicidal ideation remains unclear.

Psychache and suicidal ideation

Existing research suggests that when psychache becomes unbearable, suicide seems to be the only way to stop the suffering (Shneidman, 1993). Furthermore, studies indicated that individuals with a history of suicidal ideation—whether persistent or recent—showed significantly higher levels of psychache than those without such ideation (Ducasse et al., 2018). Certain professions, like firefighting, face exceptionally high risks of accumulating debilitating psychache due to their unique occupational stressors. For instance, a survey documented the immense operational burden on Chinese fire services (e.g., 1,189,000 responses in 2017; Chen et al., 2020), which represents a significant chronic stressor. Critically, the tragic outcomes of rescue efforts and exposure to brutal scenes create a profound gap between firefighters’ idealized self-concept and their lived experiences, constituting a major source of psychache (Tossani, 2013). In conclusion, fluctuations in psychache may predict variations in suicidal ideation, positioning psychache as a key risk factor for suicidal tendencies (Chen et al., 2024), particularly when combined with a sense of hopelessness.

Hopelessness is widely recognized as a key predictor of suicidal ideation (Klonsky et al., 2016; Ballard et al., 2022), and previous studies have identified it as a significant risk factor for suicide ideation among police officers (Violanti et al., 2016). Hopelessness is characterized by negative expectations about oneself and the future, often accompanied by a pessimistic outlook (Beck et al., 1974). Research indicates a moderate correlation between psychache and hopelessness (Siau et al., 2024). Another study showed that individuals who are more tolerant of pain are more confident in managing negative emotions (Xu et al., 2024). According to the Three-Step Theory (3ST), suicidal ideation arises from psychache, but it occurs only when hopelessness is also present. In other words, suicidal ideation emerges when individuals perceive their suffering as unchangeable and permanent (Klonsky & May, 2015). Firefighters, due to the special nature of their work, are often exposed to repeated traumatic events (Shin et al., 2023; Tsai et al., 2021). As we know, such exposure can influence their psychache and pain tolerance (Zegel et al., 2023). However, it remains unclear how hopelessness interacts with the relationship between psychache and suicidal ideation in firefighters.

Nostalgia is a ubiquitous, self-related, bittersweet but predominantly positive social emotion that involves a sense of longing for significant past experiences that are personally meaningful (Sedikides et al., 2004; Sedikides et al., 2008). Nostalgia has been shown to strengthen social connections (Juhl & Biskas, 2023; Wildschut et al., 2010), promote meaning in life (Routledge et al., 2011), and reduce loneliness and psychache (Abeyta et al., 2020).

Interestingly, initial psychache can predict stronger feelings of nostalgia (Wang et al., 2023), and nostalgia can help alleviate bereavement (Reid et al., 2021). Neurobehavioral evidence suggests that nostalgia can enhance the detection of death threats (Yang et al., 2021) and reduce suicidal ideation (Tian, 2023). For firefighters, frequent disruptions in family and social support (Regehr et al., 2005) can weaken social connections, potentially contributing to psychache and suicidal ideation. However, when experiencing psychache and hopelessness, individuals’ nostalgia may be triggered (Routledge et al., 2013; Maher et al., 2021). Thus, from this perspective, nostalgia may serve as a buffer against psychache and hopelessness, foster a sense of belonging (Abeyta et al., 2024), and potentially reduce suicidal ideation.

Nevertheless, the role of nostalgia in mitigating psychache and suicidal ideation in firefighters—who often face interpersonal (Igboanugo et al., 2021) and family-work conflicts (Regehr et al., 2005)—remains unclear. Specifically, it is uncertain how nostalgia interacts with hopelessness to influence psychache and suicidal ideation in this population.

The Three-Step Theory (3ST) of Suicide proposes that suicidal behavior evolves through three stages. Step 1: The combination of pain and hopelessness causes suicidal desire. Step 2: Suicidal desire intensifies when pain exceeds or overwhelms connectedness. Step 3: Strong suicidal desire progresses to suicide attempts if capability for suicide is present (Klonsky et al., 2021). Central to the suicidal ideation development, the interaction of psychache and hopelessness predicts suicidal ideation, while connectedness modulates their intensity (Klonsky & May, 2015). When psychache exceeds connectedness (e.g., nostalgia), strong ideation emerges; stronger connectedness conversely buffers against escalation (Klonsky & May, 2015). Empirical validations across populations confirm the framework’s explanatory power for suicide risk assessment (Pachkowski et al., 2021; Baker et al., 2025). This study applies 3ST to examine how psychache, hopelessness (Step 1), and nostalgia (Step 2) collectively influence suicidal ideation among firefighters.

Although previous studies have confirmed the relationship between psychache, suicidal ideation, hopelessness, and nostalgia, few have investigated how psychache influences suicidal ideation through the mediating roles of hopelessness and nostalgia in firefighters.

Based on the 3ST and prior research, we propose the following four hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Psychache has a significant positive predictive effect on suicidal ideation in firefighters.

Hypothesis 2: Hopelessness plays a mediating role in the relationship between psychache and suicidal ideation in firefighters, contributing to a higher level of suicidal ideation.

Hypothesis 3: Nostalgia is a mediator between psychache and suicidal ideation in firefighters, contributing to a lower level of suicidal ideation.

Hypothesis 4: Hopelessness and nostalgia play a chain mediating effect between psychache and suicidal ideation in firefighters, higher suicidal ideation linked to greater hopelessness and lower nostalgia.

A convenience sample of 652 firefighters were participants. The sample comprised 33 female (5.06%), 619 male (94.94%). Their age range was from 18 to 46 (mean = 23.71 years, SD = 4.18 years). Fifty-eight of the participants (8.90%) reported experiencing suicidal ideation.

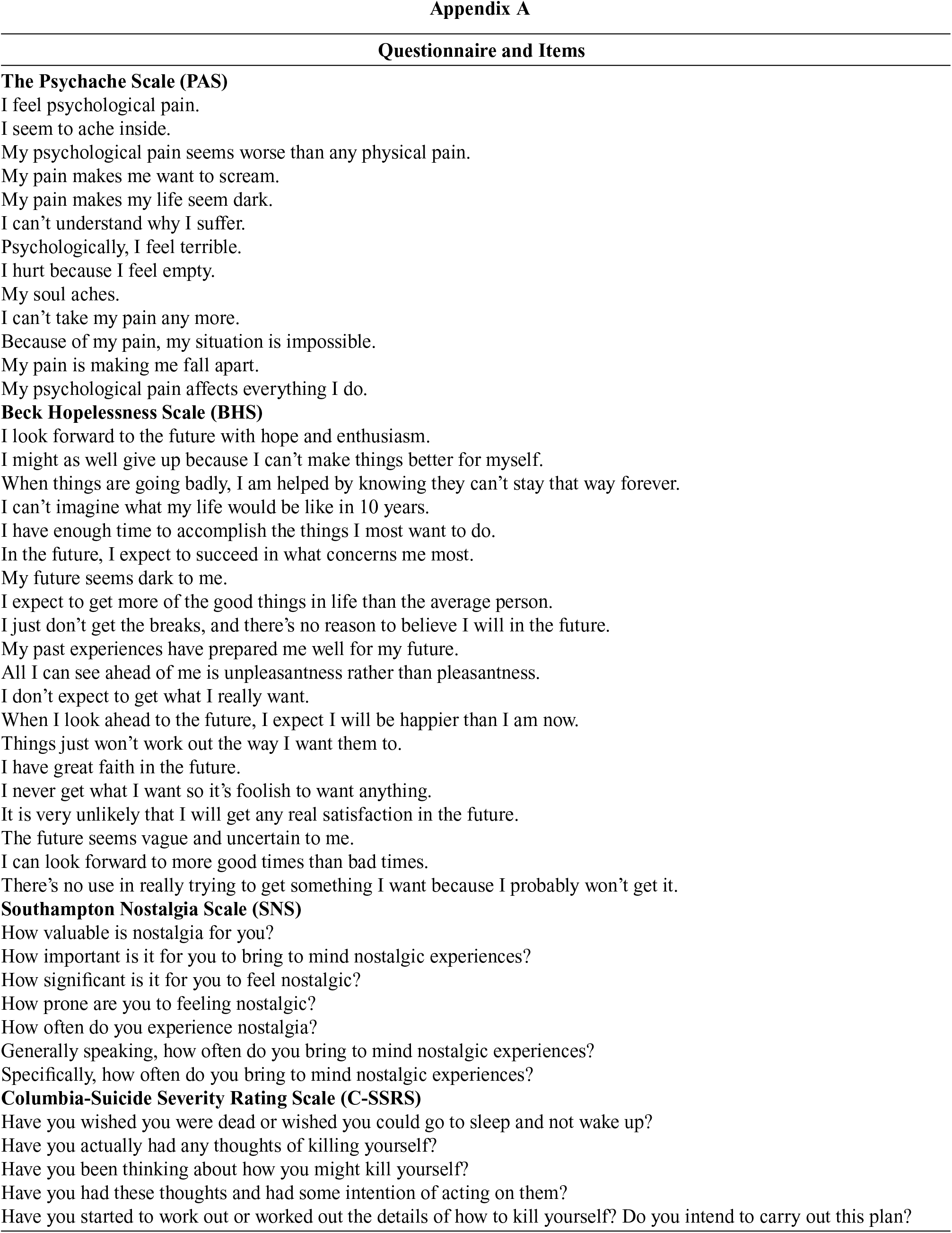

The 13 items PAS was developed by Holden et al. (2001) and later revised for the Chinese version by Li and wei (2017). Items are scores on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = Never, to 5 = Always). An example item is, “I feel psychological pain”, higher scores indicate greater levels of psychache. The alpha reliability coefficient for PAS scores was 0.96 in this study.

The BHS was developed by Beck et al. (1974) and adapted for the Chinese population by Kong et al. (2007). It comprises 20 items. An example item is, “I look forward to the future with hope and enthusiasm”, higher total scores indicating a greater degree of hopelessness. The items are on a binary scale of 1 = True or 0 = False. Also, 9 items of the items require reverse scoring. The alpha reliability coefficient for BHS scores was 0.79 in this study.

Southampton Nostalgia Scale (SNS)

The SNS was created by Wildschut et al. (2006) and revised by Zhang et al. (2024) for the Chinese version. The scale consists of 7 items, to measure the frequency of nostalgic feelings. The items are on a 7-point Likert scale (from 1 = Not at all, to 7 = Very much). An example item is, “How valuable is nostalgia for you?” Higher scores reflect a stronger tendency for nostalgia. The alpha reliability coefficient for SNS scores was 0.94 in this study.

Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

The C-SSRS was developed by Posner et al. (2011) and revised for the Chinese version by Li et al. (2023). The C-SSRS comprises 5 items to assesses suicidal ideation. Items are binary coded as 1 = yes or 0 = No. An example item is, “Have you wished you were dead or wished you could go to sleep and not wake up?” Higher scores indicate more severe suicidal ideation. The alpha reliability coefficient for C-SSRS scores was 0.72 in this study. The complete items for all scales used in this study are provided in Appendix A.

The Shanghai Normal University Ethics Committee approved the study (2025-005). Participants consented to the study. Data collection was conducted via an online platform, where firefighters accessed the electronic questionnaire by scanning a QR code with their smartphones. Participants first read the electronic informed consent form. If they selected “I agree to participate,” they were automatically redirected to the questionnaire page, where they could complete the survey based on their individual circumstances. If they selected “I do not agree to participate,” the system automatically logged them out.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (Version 26.0). First, Harman’s one-way test was conducted to assess common method bias, identifying eight items with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor explained 32.19% of the variance, which is below the 40% threshold, indicating that there was no significant common method bias in this study. Second, Model 6 of the PROCESS macro developed by Hayes (2013) was used to examine the chain mediation effect of hopelessness and nostalgia on psychache and suicidal ideation among firefighters. The model employed a bias-corrected nonparametric percentile bootstrap method with 5000 resamples to compute 95% confidence intervals.

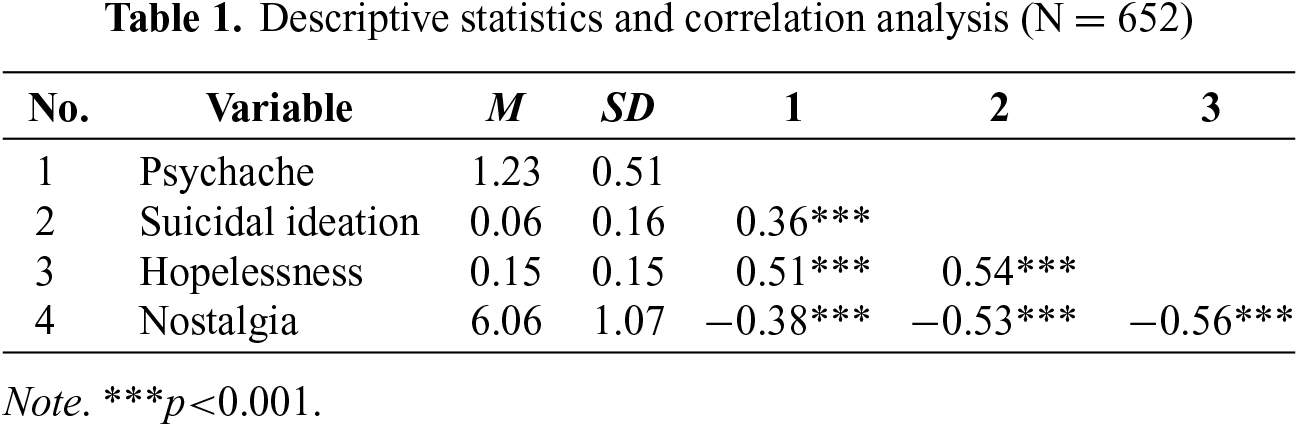

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

As in Table 1, there was a significant positive correlation between psychache and suicide ideation (r = 0.36, p < 0.001). Hopelessness was positively correlated with psychache (r = 0.51, p < 0.001) and suicidal ideation (r = 0.54, p < 0.001). Nostalgia was negatively correlated with psychache (r = −0.38, p < 0.001) and suicidal ideation (r = −0.53, p < 0.001). Nostalgia was also negatively correlated with hopelessness (r = −0.56, p < 0.001).

Predicting suicidal ideation from psychache

The regression analysis revealed that, after controlling for hopelessness and nostalgia, psychache remained a significant positive predictor of suicidal ideation in firefighters (β = 0.08, p < 0.05), accounting for 21.54% of the total effect (β = 0.36). This finding suggests that suicidal ideation among firefighters was predicted by psychache, thus supporting Hypothesis 1.

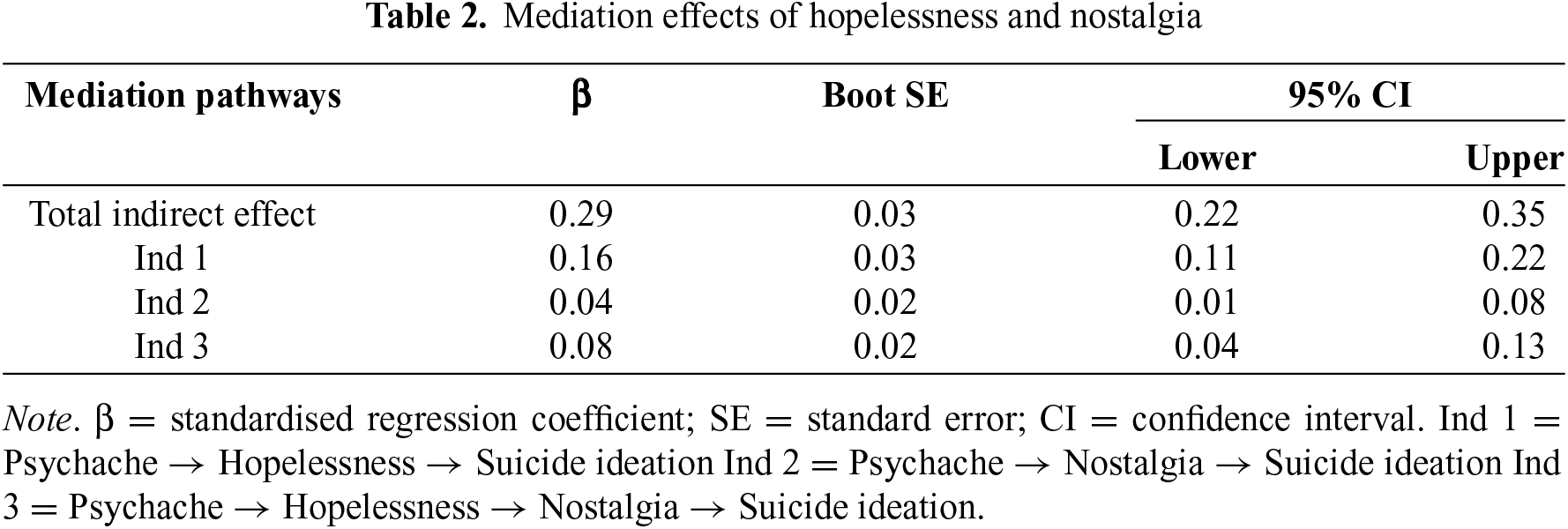

Hopelessness adjustment mediation

The regression analysis showed that psychache was a significant positive predictor of hopelessness (β = 0.51, p < 0.001), and hopelessness, in turn, significantly predicted suicidal ideation (β = 0.32, p < 0.001). Mediation effects analysis (see Table 2) revealed that hopelessness significantly mediated the relationship between psychache and suicidal ideation (β = 0.16, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.11, 0.22]), accounting for 44.68% of the total effect. This suggests that higher levels of hopelessness amplify the effect of psychache on suicidal ideation in firefighters, thus supporting Hypothesis 2.

Nostalgia adjustment mediation

The results indicated that psychache negatively predicted nostalgia (β = −0.13, p < 0.001), and nostalgia, in turn, negatively predicted suicidal ideation (β = −0.32, p < 0.001). Nostalgia significantly mediated the relationship between psychache and suicidal ideation (β = 0.04, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08]), accounting for 11.69% of the total effect. These findings suggest that higher levels of nostalgia weaken the impact of psychache on suicidal ideation in firefighters, supporting Hypothesis 3.

Hopelessness and nostalgia chain adjustment mediation

Using psychache as the independent variable (X), suicidal ideation as the dependent variable (Y), and hopelessness (M1) and nostalgia (M2) as mediators, a chain mediation model was tested (see Figure 1). The chain mediation effect was significant (β = 0.08, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.04, 0.13]), accounting for 22.09% of the total effect. This finding indicates that psychache significantly influences suicidal ideation in firefighters through both hopelessness and nostalgia, thus supporting Hypothesis 4.

Figure 1: Hopelessness and nostalgia chain mediation model. Note. *p< 0.05, ***p< 0.001.

Psychache predicted suicidal ideation among firefighters, which is consistent with previous studies (Shneidman, 1993; Verrocchio et al., 2016). The demanding and complex nature of rescue tasks, combined with inadequate fire station infrastructure and safety deficiencies, may lead to the failure of rescue efforts of “fire heroes” (Chen et al., 2020; Kennedy et al., 2019). The disillusionment stemming from failure to meet both personal and societal expectations reinforces feelings of incompetence, leading to great psychache (Goren, 2007). In an attempt to escape psychache, suicidal ideation may emerge as a coping mechanism, offering a way to alleviate internal distress. This could involve the belief that suicide would end the suffering, thereby enhancing pain tolerance (Orbach et al., 2003), particularly in firefighters, who are often expected to be more resilient to psychache.

This study findings indicate that hopelessness mediates the relationship between psychache and suicidal ideation, which aligns with previous studies (Berardelli et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2024). The findings are consistent with 3ST proposition the interaction between psychache and hopelessness contributes to the emergence of suicidal ideation. Firefighters are under immense pressures in rescue operations, carrying the responsibility for their own safety and that of others, and often making life-or-death decisions (Duarte et al., 2024). Despite rigorous training, unavoidable casualties among colleagues or rescued individuals can evoke intense self-loathing and a sense of helplessness (Phelps et al., 2018). Furthermore, disruptions in family support and difficulties in forming colleague support networks often lead to burnout and loneliness among firefighters (Smith et al., 2018). Additionally, firefighters are at risk for feelings of indebtedness toward their families, departmental accountability mechanisms, and a lack of understanding from the public exacerbate their self-doubt, shame, and guilt (Lakoma, 2023; Lentz et al., 2021; Hyun et al., 2020). These factors lead firefighters to perceive themselves as incompetent and powerless, thereby triggering suicidal ideation (Klonsky & May, 2015).

This study found that nostalgia mediates the relationship between psychache and suicidal ideation in firefighters. Previous research has shown that nostalgia can alleviate psychache (Reid et al., 2021) and reduce suicidal ideation (Tian, 2023). By the second step of the 3ST, the intensity of suicidal ideation is primarily determined by connectedness. When pain exceeds connectedness, individuals are more prone to develop strong suicidal ideation. Conversely, when connectedness outweighs experienced pain, only mild suicidal ideation may manifest (Klonsky & May, 2015). Nostalgia, as a positive resource among firefighters as by the success memories and experiences with others (Routledge et al., 2011), which can counteract loneliness (Zhou et al., 2008) and strengthen self-continuity and connectedness (Wildschut et al., 2010). Their occupational role often provides a sense of meaning in life (Tilburg et al., 2018), thereby buffering the impact of psychache on suicidal ideation among firefighters.

The results also showed that hopelessness is a risk factor for the development of suicidal ideation (Klonsky et al., 2016). According to the 3ST, both psychache and hopelessness are necessary conditions for suicidal ideation to arise, with disruptions in connectedness acting as amplifying factors. The 3ST posits that suicide originates in overwhelming physical or psychological pain that diminishes the will to live. While necessary, psychache alone cannot trigger suicidal ideation—hopelessness is essential. When psychache persists with no perceived hope of relief, suicidal ideation emerges. This framework demonstrates that deficient social connectedness facilitates escalation, whereas robust connections may restore life-sustaining motivation and reduce suicidal ideation (Klonsky & May, 2015; Klonsky et al., 2021).

The study found nostalgia serves as a suicidal ideation protective factor (Tian, 2023). Nostalgia helps firefighters mitigate one of the conditions that trigger further suicidal ideation—disruptions in social connections (Seehusen et al., 2013; Wildschut et al., 2010). Thus, nostalgia buffers the effects of psychache and hopelessness resulting from rescue-related trauma, thereby reducing the likelihood of suicidal ideation.

Implications for research and practice

The findings offer valuable insights for addressing suicidal ideation in this group. For instance, governments could establish structured incentive and accountability systems to help firefighters reframe traumatic experiences and mitigate hopelessness. Fire agencies should implement support programs to strengthen firefighters’ connections with their families and colleagues, fostering a stronger sense of belonging and hope. Additionally, psychological workers could encourage firefighters to actively document their lives through photos or diaries, could provide them with material for nostalgia, offering an emotional resource during times of psychache.

Limitations and future recommendations

This study utilized an online survey and convenience sampling, which resulted in a relatively young sample with few older firefighters participating. Therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings to other populations. Furthermore, while existing studies have distinguished the effects of different types of nostalgia on mental health, future studies could refine these distinctions. Finally, the use of self-reported data and cross-sectional sampling limits the ability to infer causality and introduces the potential for common method bias. Future research could adopt longitudinal tracking or multi-source reporting designs to enhance causal inference.

In summary, the results found psychache to predict suicidal ideation among firefighters. Hopelessness is a risk factor for suicidal ideation among firefighters, while nostalgia serves as a protective factor. Hopelessness and nostalgia act as chain mediators between firefighters’ psychache and suicidal ideation; increased hopelessness coupled with reduced nostalgia heightens suicide risk. These findings support the applicability of the 3ST within the firefighter population: psychache and hopelessness synergistically generate suicidal ideation, whereas social connectedness critically buffers against its exacerbation. Interventions aimed at alleviating psychache and preventing suicidal ideation among firefighters should seek to reduce their sense of hopelessness and to boost their sense of nostalgia.

Acknowledgement: The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Yiyang Fire and Rescue Detachment, Hengyang Fire and Rescue Detachment, Xiangtan Fire and Rescue Detachment, and Zhuzhou Fire and Rescue Detachment for their strong support for this investigation.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Wenqin Chen and Yang He; methodology, Wenqin Chen and Yuting Wen; software, Chen Hong; validation, Yuting Wen and Yanyan Hu; formal analysis, Yuting Wen and Nan Ma; investigation, Nan Ma, Wenting Yi and Guiliang Peng; resources, Yanyan Hu; data curation, Yuting Wen; writing—original draft preparation, Wenqin Chen and Wenting Yi; writing—review and editing, Yanyan Hu and Yang He; visualization, Chen Hong; supervision, Yang He; project administration, Wenqin Chen and Yang He. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee for Shanghai Normal University (2025-005) and was conducted in strict accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abeyta, A. A., Corley, D., & Hasna, N. (2024). Nostalgia promotes positive beliefs about college belonging and success among first-generation college students. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 9, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-024-00163-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Abeyta, A. A., Routledge, C., & Kaslon, S. (2020). Combating loneliness with nostalgia: Nostalgic feelings attenuate negative thoughts and motivations associated with loneliness. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1219. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01219 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Baker, S. N., Bowers, C. A., Beidel, D. C., & Rozek, D. C. (2025). Testing the three-step theory of suicide. Crisis, 46(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000987 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ballard, E. D., Farmer, C. A., Gerner, J., Bloomfield-Clagett, B., Park, L. T. et al. (2022). Prospective association of psychological pain and hopelessness with suicidal thoughts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 308, 243–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.033 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Beck, A., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. D. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(6), 861–865. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037562 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Berardelli, I., Rogante, E., Sarubbi, S., Trocchia, M. A., Longhini, L. et al. (2023). Interpersonal needs, mental pain, and hopelessness in psychiatric inpatients with suicidal ideation. Pharmacopsychiatry, 56(6), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2154-0828 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chen, M., Wang, K., Dong, X., & Li, H. (2020). Emergency rescue capability evaluation on urban fire stations in China. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 135, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

Chen, I. W., Weng, H. L., & Hung, K. C. (2024). Use of prediction interval to explore the relationship between psychological pain and suicidality. Journal of Affective Disorders, 354(1), 321–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.03.093 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cheng, Y., Zhao, W. W., Chen, S. Y., & Zhang, Y. H. (2021). Research on psychache in suicidal population: A bibliometric and visual analysis of papers published during 1994-2020. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 727663. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.727663 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cuenca-Lozano, M. F., & Ramírez-García, C. O. (2023). Occupational hazards in firefighting: Systematic literature review. Safety and Health at Work, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2023.01.005 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Duarte, I. C., Dionísio, A., Oliveira, J., Simões, M., Correia, R. et al. (2024). Neural underpinnings of ethical decisions in life and death dilemmas in naïve and expert firefighters. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 13222. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63469-y [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ducasse, D., Holden, R. R., Boyer, L., Artéro, S., Calati, R. et al. (2018). Psychological pain in suicidality: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(3), 16r10732. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16r10732 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Goren, E. (2007). Society’s use of the hero following a national trauma. American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 67(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ajp.3350013 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Holden, R. R., Mehta, K., Cunningham, E. J., & McLeod, L. D. (2001). Development and preliminary validation of a scale of psychache. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 33(4), 224–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087144 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hyun, D., Jeung, D., Kim, C., Ryu, H., & Chang, S. J. (2020). Does emotional labor increase the risk of suicidal ideation among firefighters? Yonsei Medical Journal, 61(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.3349/ymj.2020.61.2.179 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Igboanugo, S., Bigelow, P. L., & Mielke, J. G. (2021). Health outcomes of psychosocial stress within firefighters: A systematic review of the research landscape. Journal of Occupational Health, 63(1), e12219. https://doi.org/10.1002/1348-9585.12219 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Juhl, J., & Biskas, M. (2023). Nostalgia: An impactful social emotion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 49, Article 101545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101545 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kennedy, H. R., Jones, V. C., & Gielen, A. (2019). Reported fire safety and first-aid amenities in Airbnb venues in 16 American cities. Injury Prevention, 25(4), 328–330. https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2018-042740 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2015). The Three-Step Theory (3STA new theory of suicide rooted in the ideation-to-action framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 114–129. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., & Saffer, B. Y. (2016). Suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12(1), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093204 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Klonsky, E. D., Pachkowski, M. C., Shahnaz, A., & May, A. M. (2021). The three-step theory of suicide: Description, evidence, and some useful points of clarification. Preventive Medicine, 152(Pt 1), 106549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106549 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kong, Y. Y., Zhang, J., Jia, S. H., & Zhou, L. (2007). Reliability and validity of the beck hopelessness scale for adolescent. Chinese Mental Health Journal, (10), 686–689. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2007.10.008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lakoma, K. (2023). A comparative study of governance changes on the perceptions of accountability in Fire and Rescue Services in England. Public Administration, 102(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12923 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lentz, L. M., Smith-MacDonald, L., Malloy, D., Carleton, R. N., & Brémault-Phillips, S. (2021). Compromised conscience: A scoping review of moral injury among firefighters, paramedics, and police officers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 639781. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.639781 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, Z. G., Huang, L. H., Ye, D., & Peng, K. Y. (2023). Test of Columbia suicide screening scale short version in Chinese college students. Psychologies Magazine, 18(3), 58–60+64. https://doi.org/10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2023.03.015 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, Y., & wei, C. (2017). Reliability and validity of the psychache scale in Chinese undergraduates. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25(3), 475–478+583. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.03.017 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maher, P. J., Igou, E. R., & van Tilburg, W. A. P. (2021). Nostalgia relieves the disillusioned mind. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 92(3), 104061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2020.104061 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Meerwijk, E. L., & Weiss, S. J. (2014). Toward a unifying definition: Response to ‘The concept of mental pain’. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 62–63. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348869 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Orbach, I., Mikulincer, M., Sirota, P., & Gilboa-Schechtman, E. (2003). Mental pain: A multidimensional operationalization and definition. Suicide & Life-threatening Behavior, 33(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.33.3.219.23219 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pachkowski, M. C., Hewitt, P. L., & Klonsky, E. D. (2021). Examining suicidal desire through the lens of the three-step theory: A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation in a community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000546 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Phelps, S. M., Drew-Nord, D. C., Neitzel, R. L., Wallhagen, M. I., Bates, M. N. et al. (2018). Characteristics and predictors of occupational injury among career firefighters. Workplace Health & Safety, 66(6), 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079917740595 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Posner, K., Brown, G. K., Stanley, B., Brent, D. A., Yershova, K. V. et al. (2011). The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Regehr, C., Dimitropoulos, G., Bright, E., George, S., & Henderson, J. (2005). Behind the brotherhood: Rewards and challenges for wives of firefighters. Family Relations, 54(3), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.00328.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Reid, C. A., Green, J. D., Short, S. D., Willis, K. D., Moloney, J. M. et al. (2021). The past as a resource for the bereaved: Nostalgia predicts declines in distress. Cognition & Emotion, 35(2), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2020.1825339 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Routledge, C., Arndt, J., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Hart, C. M. et al. (2011). The past makes the present meaningful: Nostalgia as an existential resource. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(3), 638–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024292 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Routledge, C., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., & Juhl, J. (2013). Nostalgia as a resource for psychological health and well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 7(11), 808–818. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12070 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2008). Nostalgia: Past, present, and future. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5), 304–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00595.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Baden, D. (2004). Nostalgia: Conceptual issues and existential functions. In: J. Greenberg, S. L. Koole, T. Pyszczynski (Eds.Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 200–214The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Seehusen, J., Cordaro, F., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Routledge, C. et al. (2013). Individual differences in nostalgia proneness: The integrating role of the need to belong. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(8), 904–908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.020 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shin, Y., Nam, J. K., Lee, A., & Kim, Y. (2023). Latent profile analysis of post-traumatic stress and post-traumatic growth among firefighters. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), 149. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2159048 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Shneidman, E. S. (1993). Suicide as psychache. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 181(3), 145–147. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199303000-00001 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Siau, C. S., Klonsky, E. D., Kõlves, K., Huen, J. M. Y., Chan, C. M. H. et al. (2024). Psychache, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A cross-sectional study from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(7), 885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21070885 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Smith, T. D., Hughes, K., DeJoy, D. M., & Dyal, M. (2018). Assessment of relationships between work stress, work-family conflict, burnout and firefighter safety behavior outcomes. Safety Science, 103, 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2017.12.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Gallyer, A. J., Gray, J. S., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Suicidal behaviors among American Indian/Alaska Native firefighters: Evidence for the role of painful and provocative events. Transcultural Psychiatry, 57(2), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461519847812 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2016). A systematic review of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. Clinical Psychology Review, 44(6), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.002 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Spencer-Thomas, S., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among women firefighters: An examination of associated features and comparison of pre-career and career prevalence rates. Journal of Affective Disorders, 221(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.06.016 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tilburg, W. A., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Vingerhoets, A. J. (2018). How nostalgia infuses life with meaning: From social connectedness to self-continuity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 49(3), 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2519 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tossani, E. (2013). The concept of mental pain. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(2), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1159/000343003 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tsai, M., Lari, H., Saffy, S., & Klonsky, E. D. (2021). Examining the three-step theory (3ST) of suicide in a prospective study of adult psychiatric inpatients. Behavior Therapy, 52(3), 673–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.08.007 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Verrocchio, M. C., Carrozzino, D., Marchetti, D., Andreasson, K., Fulcheri, M. et al. (2016). Mental pain and suicide: A systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00108 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Violanti, J. M., Andrew, M. E., Mnatsakanova, A., Hartley, T. A., Fekedulegn, D. et al. (2016). Correlates of hopelessness in the high suicide risk police occupation. Police Practice & Research, 17(5), 408–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2015.1015125 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, Y., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Yang, Y., & Cai, H. (2023). Distress prospectively predicts higher nostalgia, and nostalgia prospectively predicts lower distress. Journal of Personality, 91(6), 1478–1492. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12824 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tian, W. (2023). Effect of Nostalgia on Suicide Ideation and its EEG Study [M.A. thesis]. Shaanxi, China: University of Chinese Medicine. [Google Scholar]

Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2006). Nostalgia: Content, triggers. functions Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(5), 975–993. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.975 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Routledge, C., Arndt, J., & Cordaro, F. (2010). Nostalgia as a repository of social connectedness: The role of attachment-related avoidance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017597 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xu, J., Falkenstein, M. J., & Kuckertz, J. M. (2024). Feeling more confident to encounter negative emotions: The mediating role of distress tolerance on the relationship between self-efficacy and outcomes of exposure and response prevention for OCD. Journal of Affective Disorders, 353(7), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.02.091 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yang, Z., Sedikides, C., Izuma, K., Wildschut, T., Kashima, E. S. et al. (2021). Nostalgia enhances detection of death threat: Neural and behavioral evidence. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 12662. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-91322-z [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zegel, M., Kabel, K. E., Lebeaut, A., & Vujanovic, A. A. (2023). Distress overtolerance among firefighters: Associations with posttraumatic stress. Psychological Trauma : Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 15(Suppl 2), S315–S318. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001393 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, J., Kang, T., Zhao, K., Wei, M., & Liu, L. (2024). The relationship between life satisfaction and nostalgia: Perceived social support and meaning in life chain mediation. Acta Psychologica, 243(6), 104154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104154 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhou, X., Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., & Gao, D. G. (2008). Counteracting loneliness: On the restorative function of nostalgia. Psychological Science, 19(10), 1023–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02194.x [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools