Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Workplace territorial behaviors and employee knowledge sharing: Team identification mediation and task interdependence moderation

Business School, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, 411105, China

* Corresponding Author: Hui Wang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 489-496. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.070068

Received 12 February 2025; Accepted 01 June 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

This study tested a multilevel model of the workplace territorial behaviors and employees’ knowledge sharing relationship, with team identification serving as a mediator and task interdependence as a moderator. Data were collected from 253 employees (females = 128, mean age = 28.626, SD = 6.470) from 40 work teams from different industries in China. Path analysis results indicated that workplace territorial behaviors were associated with lower employee knowledge sharing. Team identification enhanced employee knowledge sharing and partially mediated the relationship between workplace territorial behaviors and employee knowledge sharing. Task interdependence enhanced knowledge sharing and strengthened the relationship between team identification and knowledge sharing. These findings extend the proposition of social information processing theory by revealing the mediating role of team identification in the relationship between workplace territorial behaviors and knowledge sharing, and clarifying the boundary conditions of team identification. Practical implications of these findings include a need for managers to foster collaborative atmospheres, design interdependent tasks, and mitigate territorial behaviors to enhance team identification and knowledge sharing.Keywords

Employee knowledge sharing is critical to organizational competitiveness (Alsharo et al., 2017; Gibbert & Krause, 2002; Gagné, 2009). It comprises both the supply of new knowledge and the demand for new knowledge (Ardichvili et al., 2003) for managing complex and non-routine tasks. Yet, workplace territoriality would hinder employees’ knowledge sharing in ways that are less well understood, perhaps depending on employee team identification (Chiu et al., 2006; Zhu, 2016), and task interdependence. Workplace territorial behaviors refer to selfish or self-serving behaviors that involve denying collaboration with coworkers (e.g., “this is mine and not yours!”) (Brown et al., 2005). We aimed to determine how workplace territorial behaviors effects on employee knowledge sharing taking into account team identification and task interdependence.

Workplace territorial behaviors and employees’ knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing consists of both “knowledge collecting” and “knowledge donating” (Lin, 2007; Tohidinia & Mosakhani, 2010). Knowledge donating means communicating one’s personal intellectual capital to others, and knowledge collecting is defined as consulting colleagues to obtain their intellectual capital (Van den Hooff & De Ridder, 2004).

Through workplace territoriality, employees may encrypt electronic documents, personalize office space, or refuse collaboration with others. This denial of collaboration extends to knowledge items or competences (Baumeister & Leary, 1995).

Workplace territorial behaviors may cause tensions among team members (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). For instance, the boundary-setting of territorial behaviors will fuel isolation and distrust among members and ultimately lead to individuals’ deviation from collectivism. Employees with a strong territorial sense are difficult to collaborate with (Connelly et al., 2012) and less willing to share work knowledge. Based on reciprocity (Peng, 2012), they are less likely to consult colleagues (i.e., knowledge collecting) or share knowledge with colleagues (i.e., knowledge donating).

Second, workplace territorial behaviors may weaken an individual’s collectivism orientation. The boundary-setting of such behaviors fuels isolation and distrust, ultimately leading to non-conformity with collectivist norms.

Third, workplace territorial behaviors may threaten individuals’ needs for respect within the team. Such behaviors increase potential conflict: when an employee’s territory is threatened by invasion or loss, conflict likelihood rises (Brown et al., 2005). Verbal insults during conflicts and workplace exclusion can easily induce frustration, which severely undermines the need for respect in teams and weakens individual team identification.

Work team identification refers to employees’ co-ownership of work goals, benefits, and rules (Ellemers et al., 2004). Team identification is associated with reduced uncertainty (Hobman & Bordia, 2006), collective orientation (Gundlach et al., 2006), and team pride and self-esteem (Ellemers et al., 1999).

Team members with high identification are more likely to develop a sense of psychological security within the team and therefore are more willing to consult colleagues to obtain the knowledge they need. Building on social identity theory and prior research, team identification has been positively associated with knowledge sharing (Chiu et al., 2006; Kane, 2010).

Task interdependence moderation

Task independence refers to the degree to which employees need to cooperate with each other in the team to finish their work (Kiggundu, 1981; Wageman, 2001). The moderating effect of task interdependence on the relationship between team identification and knowledge sharing can be explained as follows: First, higher task interdependence requires more employee cooperation. To enhance team task performance, individuals with stronger team identification are more likely to engage in knowledge sharing, including both donating and collecting knowledge from colleagues.

Second, higher task interdependence implies greater reliance on coworkers. To secure support from other team members, individuals with higher team identification often exhibit knowledge sharing behaviors as part of a reciprocal exchange.

Drawing on social information processing theory, this study aims to fill the gap by exploring the influence of workplace territorial behaviors on employee knowledge sharing, with team identification as a mediator and task interdependence as a moderator. According to the logic of “social information-individual attitude-individual behavior” in social information processing theory (Liu et al., 2016), workplace territorial behaviors is the social information which perceived by individuals, while team identification is individuals’ attitude toward the team (Salancik & Pfeeffer, 1978). From this perspective, we suggest that when individuals perceive workplace territory behavior, their team identification will be weakened and knowledge sharing behavior also will be reduced as follows. In addition, social information processing theory also implies that in terms of moderating mechanism, social environment which individuals are located in can be view as an important factor (Peng & Su, 2010). Just as team interdependence is an important feature of team tasks, it is the degree to which individuals rely on each other, and receive direct support from coworkers to finish the task. Therefore, we predict that the interaction between team identification and task interdependence can affect employees’ knowledge sharing.

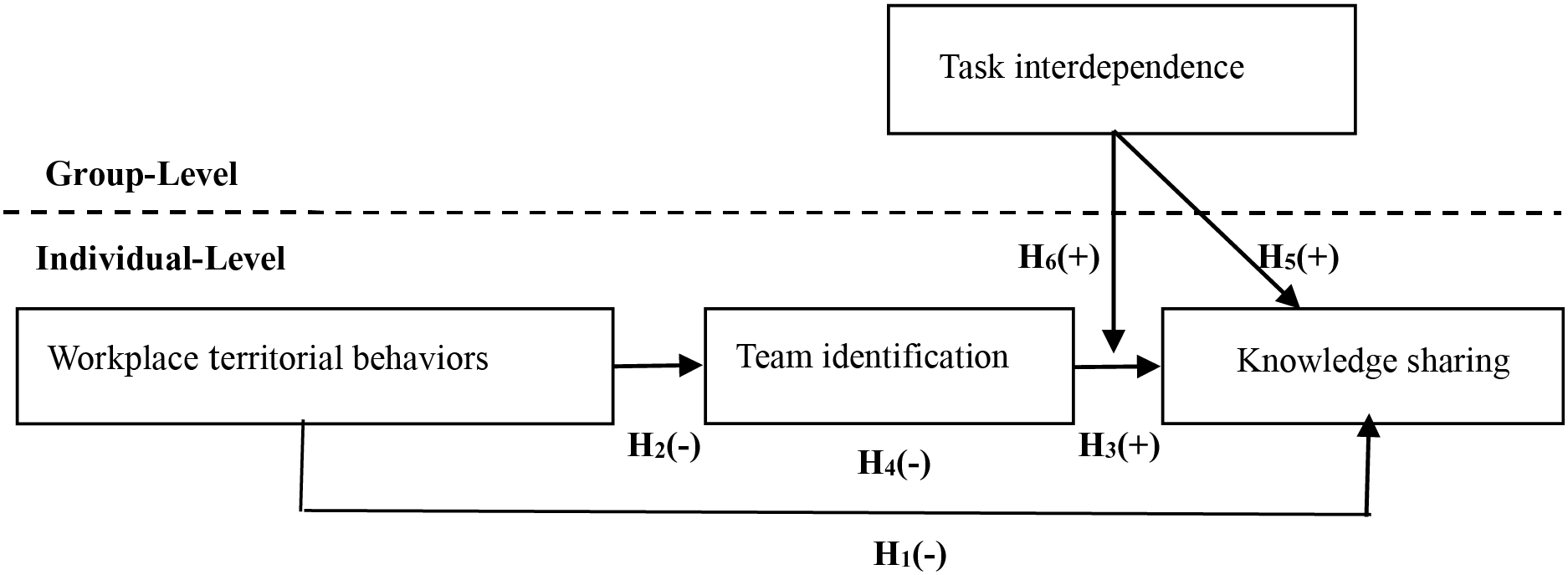

Drawing from social information processing theory, this study constructed a multilevel model (see Figure 1) in which workplace territorial behaviors influence employees’ knowledge sharing, with team identification serving as a mediator and task interdependence as a moderator. We proposed to test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Workplace territorial behaviors lower employees’ knowledge sharing.

Hypothesis 2: Workplace territorial behaviors lower team identification.

Hypothesis 3: Team identification promotes employees’ knowledge sharing.

Hypothesis 4: Team identification mediates the relationship between workplace territorial behaviors and employees’ knowledge sharing.

Hypothesis 5: Task interdependence enhances knowledge sharing.

Hypothesis 6: Task interdependence moderates the relationship between team identification and knowledge sharing.

Figure 1: Theoretical model

The study sample comprised 253 employees (females = 128, mean age = 28.626 SD = 6.470) from 40 work teams across different industries in China. In terms of gender, 49.407% of the sample was male, 50.593% of the sample was female. The average age of the sample was 28 years old. Most participants had 15 years or above of education (94.467%), 58.103% of the sample had a bachelor’s degree, 10.672% of the sample had a master’s degree. Regarding industry distribution, 25.651% were in manufacturing, 33.525% in communications and IT, 15.376% in services, and 25.448% in finance.

We utilized validated measures of workplace territorial behaviors, team identification, knowledge sharing, and task interdependence. The survey used Chinese language. Participants used a 5-point scale Likert scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to rate the items.

Workplace territorial behaviors. Workplace territorial behavior was measured with a 4-items scale developed by Liu et al. (2009). Sample items include: “Our team/department advocates a manage-your-own-space policy”, “Members in our team/department care much about their own ideas and do not allow others to use them at will”. The Cronbach’s alpha for scores from this scale was 0.789.

Team identification. Team identification was measured with a 5-item scale developed by Hobman and Bordia (2006). Sample items include “I feel strong ties between myself and other group members” and “I see myself as a member of this group”. The Cronbach’s alpha for scores from this scale was 0.776.

Knowledge sharing. This study used a 6-item knowledge sharing behavior scale designed by De Vries et al. (2006). The scale consists of both the “knowledge collecting” and “knowledge donating”, Sample items for knowledge donating are “When I have learned something new, I always tell my colleagues about it”. The knowledge collecting three items include such as “When I need certain knowledge, I ask my colleagues about it”. The Cronbach’s alpha for scores from this scale was 0.889.

Task interdependence. The 3-item scale developed by Liden et al. (1997) was utilized to measure task interdependence. Sample item is “Team members must work together to complete tasks”. The Cronbach’s alpha for scores from this scale was 0.843.

Control variables. Consistent with prior research indicating that individual traits and organization characteristic can influence employee’s knowledge sharing (De Vries et al., 2006), this study selected gender, age, education, and industry as control variables.

This study was approved by the Xiangtan University Ethics Committee. The participants were informed that the survey was anonymous and solely for academic research purposes. All participants individually consented to the study and completed the surveys online. The participants completed the surveys in two stages: At Time 1 (T1), participants completed surveys on workplace territorial behavior, task interdependence and control variables. After one month, at Time 2 (T2), the same participants completed surveys on team identification and knowledge sharing.

We conducted the analysis using MPLUS 8.3, SPSS 25.0, and HLM 8.0. First, we used MPLUS 8.3 to perform confirmatory factor analysis and assess common method variance. Then, we applied SPSS 25.0 to conduct descriptive statistics and correlation analyses. Lastly, we utilized both SPSS 25.0 and HLM 8.0 to test our hypotheses. Specifically, this study used SPSS25.0 to test the main effects of workplace territorial behaviors on knowledge sharing (Hypothesis 1), and the mediating effect of team identification on the relationship between workplace territorial behaviors and knowledge sharing (Hypothesis 4).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to verify the convergent and discriminant validity of the research constructs. Table 1 presents the results of CFA. As shown in Table 1, compared with the single-factor model, the two-factors model, and the three-factors model, the four factors fit the data best (X2/df = 1.451, RMSEA = 0.046, CFI = 0.982, IFI = 0.982, GFI = 0.951), thereby indicating that the discriminant validity of the questionnaire was appropriate.

As all the variables in this study were measured via the employees’ self-evaluation, the problem of common method variance should be considered. Therefore, the Harman single-factor method was used for the testing, and unrotated principal component analysis was conducted for all the variables. The results indicated that the variance interpretation rate of the first factor is 41.339% (less than 50%), thereby indicating the absence of common method variance in this study.

Task interdependence is a group-level variable, and the task interdependence scale is filled out by individuals. Therefore, the intra-group consistency and inter-group variability of variables need to be tested before data aggregation. Test results show that the average Rwg is 0.855, which meets the basic requirements for consistency within the group; ICC (1) = 0.409, ICC (2) = 0.830, indicating high intra-group consistency and significant inter-group difference. Therefore, it is reasonable to aggregate task interdependence to team-level research.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses

Table 2 indicates a significant negative correlation between workplace territorial behaviors and knowledge sharing (r = −0.291, p < 0.01) and a significant negative correlation between workplace territorial behaviors and team identification (r = −0.255, p < 0.01) Also, there is a significant positive correlation between team identification and knowledge sharing (r = 0.522, p < 0.01); and a significant positive correlation between task interdependence and knowledge sharing (r = 0.620, p < 0.01). This result provides preliminary support for subsequent hypothesis verification.

The main effect test: Workplace territoriality and employee knowledge sharing

As Table 3 shows, workplace territorial behaviors have a significant negative effect on knowledge sharing (β = −0.266, p < 0.001, Model 4), Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

We conducted the mediation effect test according to the four-step method (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The results are shown in Table 3. The first step was to verify the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable, which was supported by Model 4. The second step was to verify that the independent variable has a significant influence on the mediating variable. As Table 3 shows, workplace territorial behaviors demonstrated a significant negative association with team identification (β = −0.205, p < 0.001, Model 2). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Subsequently, in the third step, we investigated the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable. Findings revealed that team identification had a significant positive influence on knowledge sharing, providing support for Hypothesis 3. The fourth step was to test the mediation effects. Model 6 introduced the mediating variable of team identification. Compared with Model 2, the regression coefficient of workplace territorial behaviors on knowledge sharing was reduced from −0.205 to −0.165 and remained significant (p < 0.001). At the same time, team identification was shown to have a significant effect on knowledge sharing (β = 0.489, p < 0.001, Model 6). These results indicate that, upon introducing team identification as a mediator, the direct effect of workplace territorial behaviors on knowledge sharing weakened yet remained significant. This confirms that team identification partially mediates the relationship between workplace territorial behaviors and knowledge sharing. Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Task interdependence moderation

Since the independent variables, mediating variables, and dependent variables in this study were all at the individual level, while the moderating variable was at the team level, a cross-level analysis framework was required. Therefore, this study used HLM 8.0 to first test the direct effect of task interdependence on knowledge sharing (Hypothesis 5), and the moderating effect of task interdependence on the relationship between team identification and knowledge sharing (Hypothesis 6). The results are shown in Table 4. The intra-group variance and the inter-group variance of knowledge sharing were tested using null model (Model 1 in Table 4). Results of Model 1 revealed that the intra-group variance σ2 of knowledge sharing was 0.383, and the inter-group variance τ00 = 0.265, both being significant (χ2 = 211.221, df = 39, p < 0.001, Model 1). Furthermore ICC (1) = 0.409 (>0.138), indicating that the inter-group variance accounted for 40.900% of the total variance. This showed that the difference between groups was large enough to provide the basis for subsequent cross-level analysis.

The first step was to verify the effect of team identification on knowledge sharing. As shown in Table 4, the individual team identification has a significant influence coefficient on knowledge sharing (γ10 = 0.420, p < 0.001, Model 2) and intercept term is also significant (γ00 = 3.889, p < 0.001, Model 2). In the variance test for random coefficient regression models, the intragroup variance σ2 of Model 2, compared to that of Model 1, decreased from 0.383 to 0.285, a decrease of 25.587%, indicating that 25.587% of the intra-group variance of knowledge sharing can be explained by individual team identification. Model 2 supported the significant positive effect of team identification on knowledge sharing behavior. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was further supported.

The second step was to verify the effect of task interdependence on knowledge sharing. The results showed that task interdependence had a significant influence coefficient for the knowledge sharing (γ01 = 0.858, df = 38, p < 0.001, Model 3), and the intercept term was also significant (γ00 = 3.891, p < 0.001, Model 3). In the variance test for random coefficient regression models, the inter-group variance τ00 of Model 3, compared to that of Model 2, decreased from 0.282 to 0.075, down 73.404%. These findings suggest that task interdependence explains a substantial proportion of between-group differences in knowledge sharing, thereby supporting Hypothesis 5, which posited that task interdependence positively influences knowledge sharing.

The third step was to test the moderating effect of task interdependence on the influence process of team identification on knowledge sharing. The results showed that the interaction terms of task interdependence and team identification had a significant influence on knowledge sharing (γ11 = 0.111, df = 37, p < 0.001, Model 4), and the intercept term was also significant (γ00 = 3.898, p < 0.001, Model 4). In the variance test for random coefficient regression models, the intragroup variance σ2 of Model 4, compared to that of Model 2, decreased from 0.285 to 0.284, down 0.351%, and the inter-group variance τ00 decreased from 0.282 to 0.055, down 80.496%, indicating that 80.496% of the inter-group variance in knowledge sharing can be explained by the interaction terms of team identification and task interdependence. Thus, Hypothesis 6 was supported.

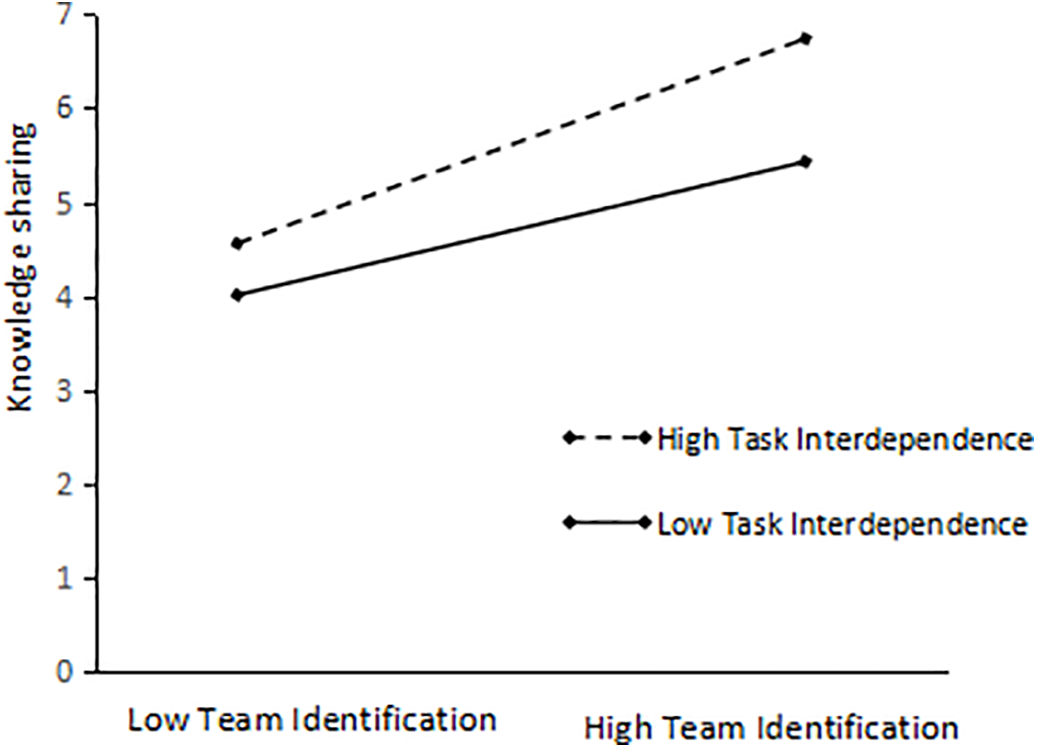

To describe the moderating effect more clearly, we conducted a simple slope analysis. As illustrated in Figure 2, the simple slope plot showed that under high task interdependence, the positive relationship between team identification and knowledge sharing was significant (simple slope = 0.520, p < 0.001), while under low task interdependence, this relationship remained significant but weaker (simple slope = 0.355, p < 0.01). The plot clearly demonstrated that the positive effect of team identification on knowledge sharing strengthened as task interdependence increased, confirming that task interdependence positively moderated this relationship. Therefore, Hypothesis 6 was further supported.

Figure 2: Moderation effect of task interdependence between team identification and knowledge sharing

The findings are as follows: First, workplace territorial behaviors have a significant negative effect on team identification and knowledge sharing. Thus, colleagues’ territorial behaviors weaken individuals’ team identification and impede their knowledge sharing. Workplace territorial behaviors manifest the competitive relationship between members. Although previous literature has shown that individuals who implement workplace territorial behaviors are likely to reject cooperation (Brown & Baer, 2015) and tend to withhold knowledge at work (Liden et al., 2006), little research has explored the relationship between workplace territorial behaviors and the recipients’ knowledge sharing. This study addresses this gap. From the perspective of the recipients, the findings indicate that employees’ perceived workplace territorial behaviors significantly and negatively impact their knowledge sharing.

Second, team identification has a positive effect on knowledge sharing and partially mediates the relationship between workplace territorial behaviors and knowledge sharing. In other words, employees with stronger team identification are more likely to share knowledge, whereas workplace territorial behaviors negatively relate to knowledge sharing by weakening team identification. Building on social information processing theory, our study reveals the mediating mechanism through which workplace territorial behaviors influence knowledge sharing. As team identification reflects individuals’ attitudes toward the team (Janssen & Huang, 2008), prior literature indicates that team identification is positively associated with knowledge sharing (Webster et al., 2008; Chang & Chuang, 2011). Extending this work and following the “social information-individual attitude-individual behavior” logic of social information processing theory, we posit team identification as a mediating variable. The findings suggest that workplace territorial behaviors indirectly and negatively affect knowledge sharing by weakening team identification.

Third, task interdependence has a significant positive effect on knowledge sharing and positively moderates the relationship between team identification and knowledge sharing. Specifically, in contexts of high task interdependence, knowledge exchange among team members is more pronounced. Social information processing theory (Salancik & Pfeeffer, 1978) posits that the social environment is critical for understanding individual behavior and suggests that situational variables can act as moderators. This aligns with our findings regarding task interdependence’s moderating role: Higher levels of task interdependence strengthen the positive relationship between team identification and knowledge sharing. Thus, as task interdependence increases, the positive association between team identification and knowledge sharing becomes more robust.

Implications for theory and practice

The results of this study contribute to existing theories in several aspects. First, within a team, members exhibit both cooperative and competitive dynamics. However, previous studies on knowledge sharing have primarily focused on the cooperative side (Gardner et al., 2012; Gong et al., 2013), while research on competitive relationships has been insufficient. Second, our study extends the current understanding of the boundary conditions under which the team identification impact on knowledge sharing stronger or weaker.

Based on this understanding, managers should pay attention to constructing a harmonious working atmosphere that supports team members in communicating with each other instead of showing territorial behaviors toward colleagues. Moreover, since workplace territorial behaviors have an indirect negative effect on knowledge sharing by weakening team identification, managers can take active measures to promote employees to share knowledge with coworkers—which includes both knowledge donating and knowledge collecting. For example, designing an open office environment (Oldham & Cummings, 1996) may send positive signals to employees and enhance their team identification. Under higher interdependence tasks, individuals who have higher team identification will show more knowledge sharing, including both knowledge donating and knowledge collecting. Therefore, managers should create tasks that require both process and resource interdependence. This means structuring tasks so that team members must collaborate and share resources to complete them.

Limitations and future directions

Despite this study’s use of a multilevel analysis approach to examine the mechanism of workplace territorial behaviors’ impact on employees’ knowledge sharing behaviors, this study has some limitations. First, due to convenience sampling and the use of cross-sectional design, we are not able to make strong inferences of causality on the basis of the current data. Therefore, in future research, a probability sample and the time-lagged design should be used. Second, this study only examined the workplace territorial behaviors within the team. However, territorial behaviors include both internal territorial behaviors and external territorial behaviors. In future research, the behaviors of both internal and external territories could be integrated into one model to examine whether the effect on employees’ knowledge sharing is different.

This study developed and tested a multilevel model to examine the influence of workplace territorial behaviors on employee knowledge sharing, with team identification acting as a mediator and task interdependence as a moderator. The findings of this research provide robust evidence to support our hypotheses. Specifically, the results indicated that workplace territorial behaviors exert a significant negative impact on employee knowledge sharing, highlighting the detrimental effects of such behaviors on the dissemination and exchange of knowledge within organizations. Furthermore, team identification emerged as a positive correlate of employee knowledge sharing and partially mediated the relationship between workplace territorial behaviors and knowledge sharing. This finding underscores the importance of fostering a strong sense of team identity in mitigating the negative consequences of territorial behaviors and promoting a culture of knowledge sharing. Lastly, task interdependence was found to have a significant positive effect on knowledge sharing and to positively moderate the relationship between team identification and knowledge sharing. This suggests that when tasks are highly interdependent, the positive influence of team identification on knowledge sharing is amplified, further emphasizing the need for organizations to design work structures that encourage collaboration and interdependence among team members. Overall, the findings of this study contribute to our understanding of the complex dynamics that govern knowledge sharing in the workplace and offer practical implications for managers and organizations seeking to enhance knowledge sharing and foster a collaborative work environment.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research has no funding support.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Ziyuan Meng, Hui Wang; Data collection: Ziyuan Meng, Yongjun Chen; Analysis and interpretation of results: Ziyuan Meng, Yongjun Chen, Hui Wang; Draft manuscript preparation: Ziyuan Meng, Hui Wang, Yongjun Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Alsharo, M., Gregg, D., & Ramirez, R. (2017). Virtual team effectiveness: The role of knowledge sharing and trust. Information & Management, 54, 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.10.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ardichvili, A., Page, V., & Wentling, T. (2003). Motivation and barriers to participation in virtual knowledge sharing communities of practice. Journal of Knowledge, 11(7), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270310463626 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brown, G., & Baer, M. (2015). Protecting the turf: The effect of territorial marking on others’ creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1785–1797. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Brown, G., Lawerence, T. B., & Robinson, S. L. (2005). Territoriality in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 30(3), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.17293710 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chang, H. H., & Chuang, S. S. (2011). Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Information & Management, 48(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2010.11.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chiu, C.-M., Hsu, M. H., & Wang, E. T. G. (2006). Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decision Support Systems, 42(3), 1872–1888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2006.04.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., & Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(1), 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.737 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

De Vries, R. E., Van den Hooff, B., & De Ridder, J. A. (2006). Explaining knowledge sharing: The role of team communication styles, job satisfaction, and performance beliefs. Communication Research, 33(2), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205285366 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ellemers, N., De Gilder, D., & Haslam, S. A. (2004). Motivating individuals and groups at work: A social identity perspective on leadership and group performance. Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2004.13670967 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ellemers, N., Kortekaas, P., & Ouwerkerk, J. W. (1999). Self-categorisation, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(2), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199903/05)29:2/3<371:AID-EJSP932>3.0.CO;2-U [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gagné, M. (2009). A model of knowledge-sharing motivation. Human Resource Management, 48(4), 571–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20298 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gardner, H. K., Gino, F., & Staats, B. R. (2012). Dynamically integrating knowledge in teams: Transforming resources into performance. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 998–1022. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0604 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gibbert, M., & Krause, H. (2002). Practice exchange in a best practice marketplace. In: Davenport, T. H., & Probst, G. J. B. (Eds.Knowledge management case book: Siemens best practices (pp. 89–105Erlangen, Germany: Publicis Corporate Publishing. [Google Scholar]

Gong, Y., Kim, T. Y., Lee, D. R., & Zhu, J. (2013). A multilevel model of team goal orientation, information exchange, and creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 56(3), 827–851. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0177 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gundlach, M., Zivnuska, S., & Stoner (2006). Understanding the relationship between individualism-collectivism and team performance through an integration of social identity theory and the social relations model. Human Relations, 59, 1603–1632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726706073193 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hobman, E. V., & Bordia, P. (2006). The role of team identification in the dissimilarity-conflict relationship. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 9(4), 483–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430206067559 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Janssen, O., & Huang, X. (2008). Us and me: team identification and individual differentiation as complementary drivers of team members’ citizenship and creative behaviors. Journal of Management, 34, 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307309263 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kane, A. A. (2010). Unlocking knowledge transfer potential: Knowledge demonstrability and superordinate social identity. Organization Science, 21(3), 643–660. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kiggundu, M. N. (1981). Task interdependence and the theory of job design. Academy of Management Review, 6, 499–508. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1981.4285795 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liden, R. C., Erdogan, B., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2006). Leader-member exchange, differentiation, and task interdependence: Implications for individual and group performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 723–746. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.409 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Bradway, L. K. (1997). Task interdependence as a moderator of the relation between group control and performance. Human Relations, 20, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016921920501 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, H.-F. (2007). Knowledge sharing and firm innovation capability: An empirical study. International Journal of Manpower, 28(3/4), 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720710755272 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, C., Liu, J., & Zhu, L. (2016). Team territory behavior and knowledge sharing behavior: Based on the perspective of identity theory. Human Resources Development of China, 21, 61–70. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Liu, J., Zhang, K., & Zhong, L. F. (2009). The formation and impact of the atmosphere of the “error routine” of the work team: A case study based on successive data. Management World, 8, 93–102. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Oldham, G. R., & Cummings, A. (1996). Employee creativity: Personal and contextual factors at work. Academy of Management Journal, 39(3), 607–634. https://doi.org/10.5465/256657 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peng, H. (2012). Territorial behaviors research: An emerging area in organizational behavior. Economic Management, 34(1), 182–189. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Peng, J.-C., & Su, F.-C. (2010). An integrative model linking feedback environment and organizational citizenship behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 150(6), 582–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903365455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 224–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392563 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tohidinia, Z., & Mosakhani, M. (2010). Knowledge sharing behaviour and its predictors. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 110(4), 611–631. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635571011039052 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van den Hooff, B., & De Ridder, J. A. (2004). Knowledge sharing in context: The influence of organizational commitment, communication climate and CMC use on knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(6), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270410567675 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wageman, R. (2001). The meaning of interdependence. In: M. E. Turner (Ed.Groups at work: Theory and research (pp. 197–217Mahwah, NJ, USA: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

Webster, J., Brown, G., Zweig, D., Connelly, C. E., Brodt, S. et al. (2008). Beyond knowledge sharing: Withholding knowledge at work. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 27, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(08)27001-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhu, Y.-Q. (2016). Solving knowledge sharing disparity: The role of team identification, organizational identification, and in-group bias. International Journal of Information Management, 36(6), 1174–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2016.08.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools