Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Family as the first school: How do parenting and family adjustment shape toddler socioemotional development?

1 College of Preschool Education, Capital Normal University, Beijing, 100048, China

2 Faculty of Education, East China Normal University, Shanghai, 200062, China

* Corresponding Author: Fang Wang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 651-659. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.066088

Received 29 March 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study explores parenting and family adjustment profile effects on toddler socioemotional competence by the underlying mechanisms of effortful control. Participants were Chinese parent caregivers (N = 448) of 448 toddlers aged 15–36 months. They completed measures of parenting and family adjustment, toddler socioemotional competence, and effortful control. Latent profile analysis (LPA) identified three family profiles—Strict-Detached, Constrained-Collaborative, and Harmonious-Aligned. These three profiles of parenting and family adjustment directly affect toddler socioemotional competence through variations in emotional support, discipline strategies, and parent–child interactions. Effortful control mediates this relationship of parenting and family adjustment and toddler socioemotional competence, with toddlers from Strict-Detached families at higher risk for socioemotional problems associated with lower effortful control. The harmoniously aligned family profile is associated with healthier development via higher effortful control. The research adds to the developmental understanding of how parenting and family dynamics affect toddler development by identifying effortful control as a key pathway. Based on these findings, parent caregiver profiles should be part of intervention designs aimed to enhance toddlers’ effortful control for healthy development.Keywords

Parenting behaviors and family adaptation, serve to promote socioemotional development and competencies in children (Pontoppidan et al., 2017). However, not all parenting situations are equal, and there would be differences among parenting or family practices for the better or worse psychological and social outcomes for children (Goagoses et al., 2023). Cultural context matters to parenting and family behaviours, and few studies have examined the related effects on childhood outcomes in collectivistic cultures like China, highlighting a critical gap addressed by this study. Our study aimed to address this gap in the evidence.

Parenting and family adjustment to child rearing

Parenting encompasses the practices and behaviors parents employ to raise their children, including caregiving, boundary-setting, and fostering a supportive environment (Spera, 2005). Family adjustment refers to the emotional and psychological adaptation of family members to diverse life circumstances and stressors, encompassing relationship quality, parental well-being, and available support systems, which are vital for maintaining a nurturing environment for children (Lamb, 2012; Thompson et al., 2013).

Necessarily, parenting practices are indicative of family adjustment regarding child rearing (Lansford, 2017; Sanders et al., 2014). Parenting and family adjustment to child-rearing demands would vary by factors such as family structure, socioeconomic status, and parental characteristics (Chen et al., 2019; Roubinov & Boyce, 2017). Moreover, families have diverse ways and manifestations when it comes to handling education and emotional support (Fiese & Fisher, 2019).

Regardless, supportive parenting from both mothers and fathers—marked by sensitivity, warmth, and engagement—promotes better socioemotional functioning in children (Feldman et al., 2023; Zhong et al., 2020). Furthermore, secure attachment, fostered by sensitive and responsive parenting, is essential for optimal socioemotional development (Væver et al., 2016). Family dynamics also play a pivotal role; effective family functioning, including routines, communication, and conflict resolution strategies, supports improved developmental outcomes (Fiese & Winter, 2008). Additionally, marital adjustment and high-quality parent-child relationships foster increased parental involvement and sensitivity, positively impacting infant development (Planalp et al., 2013).

By contrast, the use of coercive power by parents, particularly through harsh corporal punishment and verbal hostility, is associated with lower social competence and increased problem behaviors in children (Baumrind, 2012; Belsky, 2008). Similarly, marital conflict has a detrimental effect on toddlers’ social behavioral development (Whiteside-Mansell et al., 2009). Ultimately, parenting effortful control would differentiate child development outcomes directly or indirectly.

Effortful control refers to an individual’s ability to consciously regulate behavior, emotion, and cognition—including inhibiting a dominant response, activating a subdominant one, focusing or shifting attention, and detecting errors (Santens et al., 2020). It is a central concept in the study of children’s temperament and is often associated with self-regulation abilities (Putnam et al., 2006) and is implicated in how the family environment influences children’s developmental outcomes. For instance, a control-oriented style may suppress toddlers’ emotional expression and regulation, increasing socioemotional difficulties (Engel et al., 2023; Mortensen & Barnett, 2019). In contrast, supportive maternal parenting, referring specifically to parenting by mothers as examined in previous research, is marked by sensitivity and warmth and fosters toddlers’ effortful control—a process mediated by self-regulation abilities that enhance social competence and reduce externalizing problems (Pereira et al., 2021; Spinrad et al., 2007). Higher parental extraversion is associated with effortful control (Behrendt et al., 2020; Gartstein et al., 2013), and fewer children’s behavioral problems (Coe et al., 2024), underscoring its pivotal role in early development.

However, most existing studies have focused on specific dimensions of parenting or family dynamics, such as parenting styles or parental stress (Smetana, 2017; Crnic, 2024). These variable-centered studies have inadvertently neglected parenting and family adjustment patterns by the heterogeneity of family profiles. A variable-centered approach assumes that family characteristics are evenly distributed and overlooks the complex interactions and heterogeneity among the elements within the family system. Latent profile analysis (LPA), as a person-centered approach, enables the identification of these latent family profiles by capturing the multifaceted combinations of parenting practices and family adjustment. This method has been effectively applied in prior studies to uncover distinct family profiles and their differential impacts on child development, e.g., Preston et al. (2022), providing a robust framework for examining the nuanced effects of family dynamics.

Parenting and childrearing are themselves cultural practices (Qi & Du, 2020). In China, traditional parenting concepts emphasize parental authority and strict behavioral control, believing that this approach contributes to children’s development (Wu, 2012). These beliefs are deeply rooted in Confucian philosophy, collectivist ideology, and conformity-oriented cultural values (Liu & Merritt, 2018). Within such cultural frameworks, children’s obedience is often viewed as a manifestation of filial piety and is believed to contribute to academic success and future achievement. This obedience-centered parenting ideal is not only embedded in family-level practices but also reinforced by broader societal expectations of what constitutes “successful parenting” (Qi & Du, 2020). These parenting values have been transmitted across generations, leading many contemporary Chinese parents to maintain control-oriented parenting practices despite increasing exposure to modern parenting ideologies (Li et al., 2019). This highly restrictive parenting style is typically characterized by limited emotional expression, greater use of restrictive or psychological control strategies, and reduced autonomy granted to children (Luo et al., 2013). Cross-cultural studies have further substantiated these differences, demonstrating that Chinese parents, compared to their Western counterparts, are less likely to adopt child-centered approaches that emphasize autonomy, open communication, and emotional expression (Skinner et al., 2022; Lansford et al., 2018).

While China government currently emphasizes the critical role of families in toddler’s development, there is a lack of specific, supportive policies and measures aimed at enhancing parents’ parenting skills, particularly in addressing the cultural prevalence of coercive discipline rooted in Confucian traditions (Zhong et al., 2020). Despite this lack of structural support, China’s rapid economic and social transformation over recent decades has gradually influenced parental beliefs and behaviors. Emerging trends indicate a shift away from traditional authoritarian models toward more emotionally responsive and autonomy-supportive parenting practices (Guo et al., 2017). These changes reflect a growing awareness of children’s emotional needs alongside behavioral regulation, which may better support their social-emotional development.

We aimed to identify the latent profiles of parenting and family adjustment for early childhood socioemotional competence in the Chinese context by the parents and family effort control. We tested the following hypotheses:

H1: Parenting and family adjustment is represented by distinct latent profiles among families with toddlers.

H2: Effortful control mediates the relationship between the latent profiles of parenting and family adjustment for the socioemotional competence of toddlers to be higher.

Participants were a convenience sample of 448 primary caregivers. They looked after 220 boys (49.11%) and 228 girls (50.89%), distributed across age subgroups: 38 children (8.48%) in the 18-month-old subgroup, 89 (19.87%) in the 24-month-old subgroup, 158 (35.27%) in the 30-month-old subgroup, and 163 (36.38%) in the 36-month-old subgroup. Most participants were only children (n = 312, 69.64%) and held urban household registration (n = 378, 84.38%). The mean duration of childcare was 0.57 years (SD = 0.55).

Parent carers completed the following measures: the Parenting and Family Adjustment Scales (PAFAS), the Ages and Stages Questionnaires: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE-2), and the Infant/Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire–Very Short Form. These are described next.

Parenting and family adjustment

The Parenting and Family Adjustment Scales (PAFAS; Sanders et al. (2014)) is an 18-item measure of parenting behaviors (6 items, e.g., “If my child doesn’t do what they’ re told to do, I give in and do it myself.”) and family adjustment (12 items, e.g., “Our family members help or support each other.”). It has been linguistically and culturally adapted and validated in Chinese samples (e.g., Guo et al., 2017). The scale uses a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (4). Higher scores indicate better parenting behaviors and family adjustment, except for the coercive discipline dimension. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for PAFAS scores were 0.76 and 0.88, respectively.

Toddler socioemotional competence

The Ages and Stages Questionnaires: Socioemotional, Second Edition (ASQ:SE, Squires et al. (2015)) comprises 35 items to measure self-regulation (5 items, e.g., Move easily from one activity to another?), compliance (6 items, e.g., Follow your simple or routine directions?), adaptive functioning (4 items, e.g., Stay awake for an hour or more at a time, during the day?), autonomy (5 items, e.g., Cling to you more than you would expect?), affect (5 items, e.g., Show concern for other people’s feelings?) social communication (5 items, e.g., Look at you and seem to listen when you talk?), and interaction (5 items, e.g., Laugh or smile at you and family members?). This questionnaire has been culturally adapted and psychometrically validated in the Chinese context (Xie et al., 2021). Parents rated their child’s behavior based on how well it matched the behavior described in each item. Responses were given on a 3-point scale: ‘Frequently/Always’ (0), ‘Occasionally/Sometimes’ (5), and ‘Rarely/Never’ (10). A higher score indicates a greater likelihood of socioemotional developmental delay. The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for ASQ:SE ranged between 0.84 and 0.92.

The Infant/Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire, Very Short Form (IECBQ-SF; Gartstein and Rothbart, 2003) comprises 12 items (“Can wait when told to do so before a new activity”, “Can easily stop an activity when told ‘no’”). The scale uses a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “Never” (1 point) to “Always” (7 points), with higher scores indicating better effortful control. For this research, the scale was translated by two graduate students in the field of education and proofread by a graduate student majoring in English. Finally, it was evaluated by experts for its ability to assess effortful control in the Chinese context. The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) for IECBQ-SF scores ranged from 0.78 to 0.82, respectively.

Participants were recruited using convenience cluster sampling from early childhood education centers in Beijing, China. Caregivers were invited to participate through collaboration with local kindergartens and community parenting groups. Teachers and administrators helped distribute the survey link (hosted on wjx.cn) via internal parent communication platforms (e.g., WeChat). The inclusion criteria were: (1) caregivers of toddlers aged 15 to 36 months; (2) the primary caregiver (defined as the parent or guardian who spends the most time with the child).The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) children with diagnosed neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, ADHD) or serious physical or medical conditions; and (2) invalid responses, including those completed in under five minutes or those in which all items were answered with identical response options.

This research received ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of College of Preschool Education, Capital Normal University. Participants consented to the study. They were assured that their participation was entirely voluntary, and they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without any consequence or explanation, should they feel uncomfortable during the process. Upon completion of the survey, participants were provided with a small token of appreciation as a gesture of gratitude for their time and participation. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality in this online study, no personally identifiable information (such as names, contact details, or IP addresses) was collected. Responses were automatically anonymized, and all data were stored in encrypted files accessible only to the research team.

Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to examine the potential presence of common method bias in this study. The results indicated that the percentage of variance explained by the first factor was 35.06%, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) was conducted using MPlus 8.3 software to identify latent profiles of parenting and family adjustment. The Latent profile analysis (LPA) was conducted using the seven dimensions of parenting and family adaptation as indicators. Starting with a one-class baseline model, we systematically evaluated model fit indices across successive class solutions. Model selection criteria required entropy values ≥0.80, statistically significant Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMRT) and bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) results, and lower Akaike information criterion (AIC)/Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values indicating superior model fit.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 26.0. The PROCESS macro was employed to test for mediational effects (Hayes & Preacher, 2014). In this study, the independent variable (X) is parenting and family adjustment, which is a three-category independent variable (K = 3). The mediating variable (M) is effortful control, and the dependent variable (Y) is toddler socioemotional competence. Both the mediating variable and the dependent variable are continuous variables. The mediating effect of the multi-category independent variable was tested using the SPSS PROCESS macro based on a bootstrap approach.

Bootstrap sampling was set to 5000 iterations, and the statistical significance of the mediating effects was determined using 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Latent profile analysis of parenting and family adjustment

As shown in Table 1, both 2-class and 3-class models demonstrated statistically significant LMR (p < 0.001) and BLRT (p < 0.001) values. Comparative evaluation revealed that the 2-class solution yielded the highest AIC (12,457.32) and BIC (12,598.14) values. In contrast, the 3-class model exhibited substantially improved fit indices (AIC = 11,892.45; BIC = 12,074.28) with entropy = 0.86, satisfying all predefined criteria for optimal classification. Consequently, the 3-class solution was retained as the parsimonious model that best captured population heterogeneity in family functioning patterns.

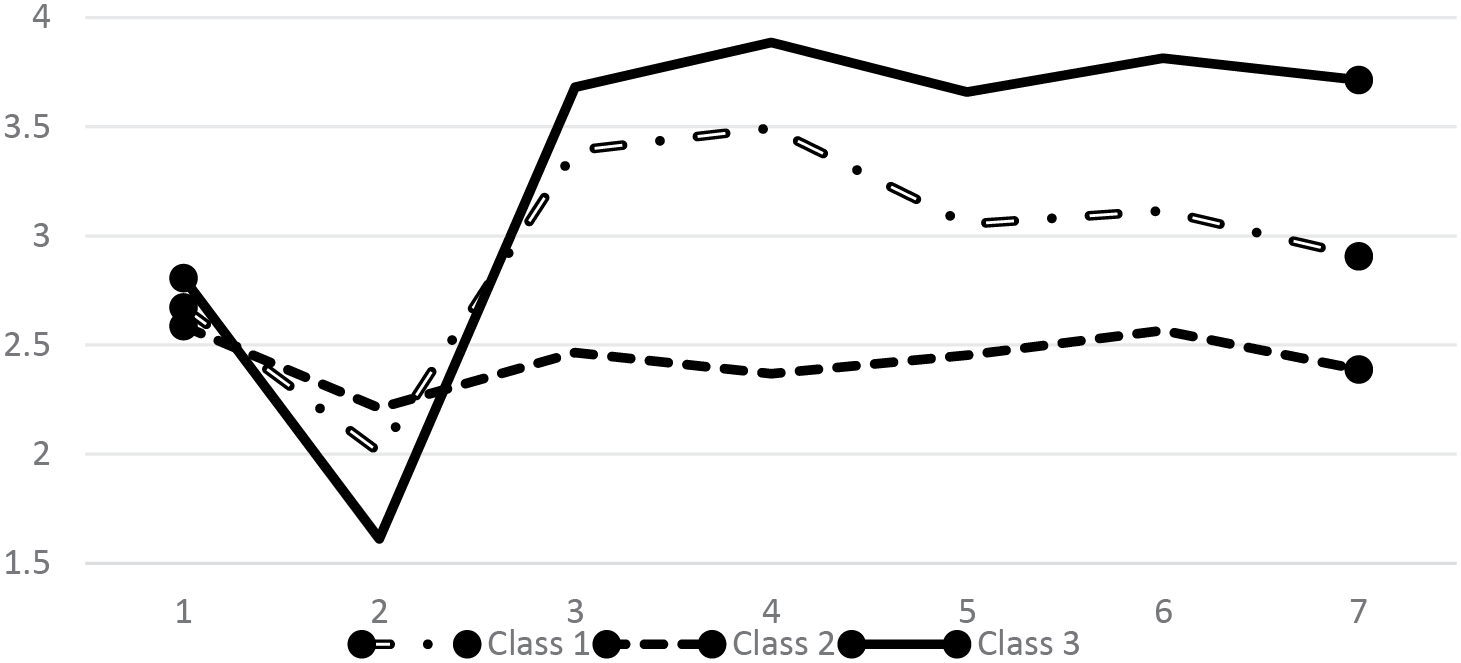

As shown in Figure 1, the conditional means of the three classes exhibit distinct characteristics. Among the three classes, Class 1 exhibits moderate scores across all items, with coercive discipline scores being slightly higher, but positive encouragement, parent-child relationship, and other dimensions showing moderate levels. The family parenting style is clear but lacks warmth, with strict rule enforcement and moderate adaptability. This profile is thus named the “Constrained-Collaborative profile”, comprising 28.5% of the total sample. Class 2 scores the highest on coercive discipline compared to the other two classes, while its scores on the other six dimensions are lower in comparison. This class relies on coercive parenting strategies and provides insufficient encouragement and parent-child closeness, and exhibits the weakest adaptability. Therefore, it is named the “Strict-Detached profile”, comprising 10% of the total sample. Class 3 scores the highest on all dimensions relative to the other two classes, with the lowest score on coercive discipline. Parents in this group demonstrate high consistency in their parenting, effectively use positive encouragement, maintain a close parent-child relationship, and have strong family cooperation and adjustment abilities. Therefore, it is named the “Harmonious-Aligned profile,” comprising 64% of the total sample.

Figure 1: Latent profile analysis of parenting and family adjustment. Note. 1 = parental consistency, 2 = coercive discipline, 3 = positive encouragement, 4 = the parent-child relationship, 5 = parental adjustment, 6 = family relationships, 7 = parental teamwork

To verify the accuracy of the latent profile analysis classification results, discriminant analysis was conducted using the seven dimensions as indicators. The results indicated that the classification accuracy for parenting and family adjustment profiles exceeded 90% for all classes (Class 1–3: 92.2%, 94.6%, and 96.7%, respectively), suggesting that the latent profile analysis results are reliable.

To examine whether there are significant differences among the three family profiles across the seven dimensions, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted (see Table 2). The results showed significant differences in the mean scores of all seven items across the three groups. Specifically, with the exception of coercive discipline, families in the Strict-Detached profile scored significantly lower than those in the Harmonious-Aligned and Constrained-Collaborative profile across all other dimensions. The Constrained-Collaborative profile scored significantly higher than the Strict-Detached profile on all seven dimensions, but lower than the Harmonious-Aligned profile. Regarding coercive discipline, families in the Strict-Detached profile scored significantly higher than the other two profiles, indicating heterogeneity in the latent profiles of parenting and family adjustment. Hypothesis 1 was supported.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix of the main variables and reports the means and standard deviations for each variable. As shown in Table 3, significant correlations exist between parenting and family adjustment, effortful control, and socioemotional competence (p < 0.05).

The omnibus mediation test revealed significant total effects (F(2, 445) = 79.47, p < 0.001), rejecting the null hypothesis of all relative total effects being zero. Similarly, the direct effects reached significance (F(2, 444) = 49.41, p < 0.001), indicating non-zero relative direct effects. The 95% Bootstrap confidence intervals for both relative mediation effects did not include zero, necessitating further relative mediation analysis.

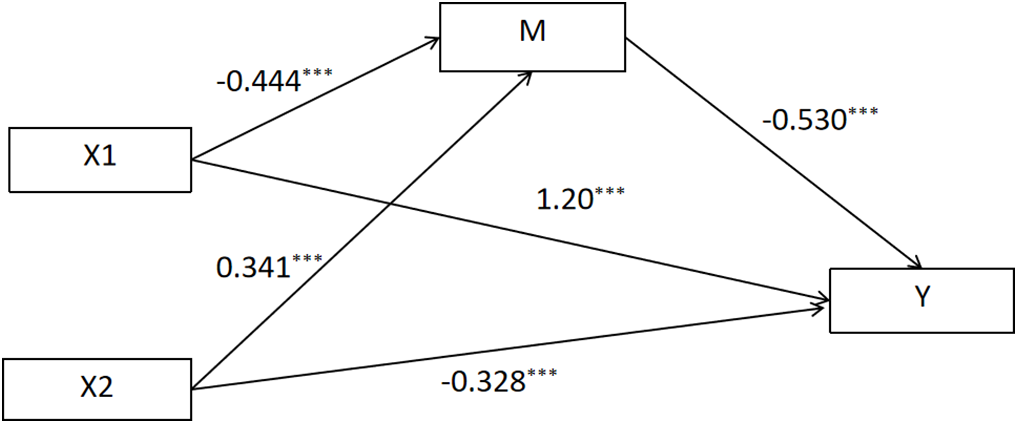

The relative mediation analysis, using the Constrained-Collaborative profile as the reference, showed that the mediation effect of the Strict-Detached profile relative to the Constrained-Collaborative profile was significant, with a 95% Bootstrap confidence interval of [0.102, 0.385] (excluding zero; a1 = −0.44, b = −0.53, a1b = 0.233). Specifically, toddlers in Strict-Detached profiles exhibited 0.44 lower effortful control compared to those in Constrained-Collaborative profiles (a1 = −0.44). Through the mediating role of effortful control, the likelihood of socioemotional developmental delays in toddlers from Strict-Detached profiles indirectly increased by 0.233. The relative direct effect was significant (c’1 = 1.20, p < 0.001), indicating that, after accounting for mediation, the likelihood of socioemotional developmental delays in toddlers from Strict-Detached profiles was 1.20 higher than in Constrained-Collaborative profiles. The relative total effect was also significant (c1 = 1.43, p < 0.0001), with the mediation effect accounting for 16.3% of the total effect.

Similarly, using the Constrained-Collaborative profile as the reference, the relative mediation effect of the Harmonious-Aligned profile compared to the Constrained-Collaborative profile was significant, with a 95% Bootstrap confidence interval of [−0.276, −0.103] (excluding zero; a2 = 0.341, b = −0.53, a2b = −0.18). Specifically, toddlers in Harmonious-Aligned profiles exhibited 0.341 higher effortful control compared to those in Constrained-Collaborative profiles, thereby reducing the likelihood of socioemotional developmental delays through the mediating role of effortful control. The relative direct effect was significant (c’2 = −0.328, p < 0.001), indicating that, after accounting for mediation, the likelihood of socioemotional developmental delays in toddlers from Harmonious-Aligned profiles was 0.328 lower than in Constrained-Collaborative profiles. The relative total effect was also significant (c2 = −0.509, p < 0.001), with the mediation effect accounting for 35.4% of the total effect. Results are presented in Figure 2 and Table 4. Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Figure 2: A mediation model for sense of Parenting and Family Adjustment profile, Effortful Control and Socioemotional Competence. Note. X1: Strict-Detached profiles, X2: Harmonious-Aligned profiles, M: Effortful Control, Y: Socioemotional Competence, *** p < 0.001.

This study identified three heterogeneous family profiles: Strict-Detached Profile, Constrained-Collaborative Profile, and Harmonious-Aligned Profile. Significant differences were found across all seven dimensions, validating the effectiveness of the classification. These results suggest that parenting and family adjustment abilities are not evenly distributed across families, with significant differences. This illustrates the complexity of contemporary parenting in China, where distinct patterns of parenting and family adjustment have emerged even within a shared cultural context (Guo et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2023).

The Strict-Detached Profile scores the lowest across all dimensions, with coercive discipline significantly higher than the other profiles (M = 2.23). This profile suggests that parents overly rely on controlling strategies while lacking emotional support. This represents the most typical parenting style under China’s tradition of valuing authority and behavioral conformity (Lu et al., 2023). On the one hand, it highlights the profound influence of culture on parenting: even after thousands of years, a small proportion of parents still firmly adhere to these traditional beliefs. As Ashdown & Faherty (2020, p. 3) note that cultural beliefs and attitudes are already embedded in the behaviors, beliefs, and techniques that parents and caregivers utilize with the children in their care. On the other hand, it may be linked to emotional regulation deficits caused by parenting stress (e.g., economic stress). Parents with greater difficulties in emotion regulation tend to engage more frequently in negative parenting practices and respond to their children with unsupportive behaviors (Zimmer-Gembeck et al., 2022). Although the Strict-Detached Profile represents the smallest proportion, its low parent–child relationship quality and high levels of coercive parenting behaviors indicate a heightened risk of child behavioral problems, such as difficulties in forming healthy peer relationships and expressing emotions (Scaramella & Leve, 2004). Prior research has consistently linked such parenting characteristics to increased levels of aggression, anxiety, and impaired social functioning in children (Goagoses et al., 2023; Spera, 2005). Given these risks, greater attention should be directed toward this family profile in both empirical research and policy interventions.

The Constrained-Collaborative profile exhibits a typical pattern of moderate to high control combined with moderate warmth: coercive discipline scores are relatively high (M = 2.02), while positive encouragement (M = 3.39) and parent-child relationship (M = 3.49) are at moderate levels. Parents in this class are highly consistent in rule enforcement but show limited flexibility in emotional responsiveness, which may reflect a balance between external social pressures and a diminished sense of parenting efficacy.

Notably, their family adjustment ability (M = 3.06) is significantly better than the Strict-Detached profile but lower than the Harmonious-Aligned. This profile has a relatively high proportion, suggesting that many families face challenges in balancing discipline with emotional support, which may have long-term implications for child development. This also supports previous research and highlights the importance of cultural context. For example, parenting beliefs among Chinese and African American parents differ from those of White and Latino parents—the former tend to adopt more controlling approaches, while the latter emphasize a more accepting attitude toward children and set fewer behavioral demands (Ashdown & Faherty, 2020). In China, parents often face multiple sources of stress simultaneously rather than in isolation—for example, traditional cultural norms, societal expectations, children’s behavioral difficulties, and family-related risks (Wang et al., 2020). These stressors may lead parents to adopt harsh disciplinary practices that manifest more in children’s psychological distress than in physical punishment, thereby potentially undermining emotional support within the parent–child relationship (Liu et al., 2022). Such parenting approaches may represent adaptive strategies in a culture that highly values behavioral conformity and social harmony, as is the case in China.

The Harmonious-Aligned profile, as the dominant type, performs best across dimensions such as positive encouragement, parent-child relationship, and family cooperation, while scoring the lowest on coercive discipline. This class represents the largest proportion of families, reflecting a system characterized by collaborative development. This shift may reflect the influence of Western parenting practices (Xu et al., 2005). However, it also suggests that contemporary Chinese parents’ adoption of warm and supportive parenting is not necessarily in conflict with the traditional collectivist cultural context, as emotional support and close relationships may serve as essential bonding mechanisms within parent–child dynamics (Lu et al., 2023). Parents in this group guide children’s behavior through emotional resonance rather than coercive methods, while sustaining high levels of cooperation and conflict resolution. This advantage likely stems from the positive interplay of internal family resources and effective emotional regulation practices among parents. As demonstrated in previous research, caregivers’ appropriate expression of their own emotions significantly contributes to the socialization of children’s emotion regulation skills (Qiu & Shum, 2022).

Family functioning is more balanced when parents effectively manage conflicts, emotional expression, and daily matters (Jones & Prinz, 2005), which creates a stable environment that helps infants and toddlers develop self-regulation and socioemotional skills. The high-quality parent-child relationship and family cooperation in this profile indicate that parents provide a stable emotional safety net through consistent emotional responses and positive interactions (Cui et al., 2018). This warm, sensitive, and balanced parenting environment may enhance emotional regulation abilities, allowing infants and toddlers to show greater initiative and adaptability in social situations (Repetti et al., 2015). The Harmonious-Aligned profile, which combines control with child autonomy, helps children learn to trust others and effectively manage negative emotions.

This study found that parenting and family adjustment may relate to child development through the pathway of effortful control, which reflects children’s self-regulation abilities. Effortful control is an early manifestation of executive function and serves as a critical psychological resource for emotional regulation and social functioning (Santens et al., 2020). However, effortful control is not an innate or fixed trait; it is significantly shaped by early environmental factors, particularly parenting behaviors and the overall emotional climate of the family. For instance, in Strict-Detached families, where high coercive discipline is prevalent (as with traditional Chinese values) the strict discipline would seem like alack of emotional support risking weak infants’ effortful control (Petrenko et al., 2019). Behrendt et al. (2020) noted that infants may experience heightened anxiety when confronted with coercive rules, impairing their ability to develop effective self-regulation strategies and increasing the risk of socioemotional problems. In contrast, Harmonious-Aligned families, characterized by low coercive discipline and high emotional support, enhance toddlers’ effortful control by providing a secure psychological environment (Eisenberg et al., 2009).

Implications for Research and Practice

This study provides significant guidance for family education practices. The findings reveal the profiles of parenting and family adjustment, as well as the pathways through which they are associated with socioemotional competence via effortful control. This provides a theoretical foundation for subsequent interventions and fills the gap between policy support and practical implementation.

Second, parenting support training interventions should focus on enhancing positive parenting skills, specifically teaching non-coercive responses and emotional support strategies to improve the parent-child relationship (Sanders et al., 2014). Given the relevance of cultural context, such programs could focus on positive reinforcement, helping parents manage stress and improve their psychological well-being (Thompson et al., 2013).

Finally, these interventions may face challenges, such as limited access to trained facilitators, low parental engagement due to time constraints, and resistance to changing coercive discipline practices. To address this, policymakers could prioritize funding for regions with higher proportions of at-risk family profiles, identified through community surveys, and offer flexible training formats, such as online modules, to increase accessibility and accommodate cultural attitudes toward parenting. These strategies ensure that research findings translate into meaningful improvements in family education practices, optimizing early childhood development across diverse family contexts.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, the participants were all from China, and the sample was disproportionately composed of older toddlers (30–36 months), which may limit the generalizability of the findings to younger age groups. Future research should consider recruiting a more age-balanced and diverse sample, and conducting cross-cultural comparisons to enhance external validity. Second, the study employed a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to make causal inferences. The mediation results reported in this study should therefore be understood as statistical associations rather than evidence of causal mechanisms. Future research using longitudinal or experimental designs is needed to further validate the proposed pathways and clarify the directionality of effects. Finally, this study primarily relied on parent-reported data, which may be subject to bias. Future research could combine observational methods and teacher reports to enhance the objectivity of the data.

This study utilized latent profile analysis to identify three distinct parenting and family adjustment profiles in Chinese families: Strict-Detached, Constrained-Collaborative, and Harmonious-Aligned. The results reveal that families characterized by lower levels of parenting behavior and family adjustment are associated with poorer toddler socioemotional competence, typically in the context of high control and limited emotional support. In contrast, families with more positive parenting and better adjustment tend to be linked with more favorable socioemotional development, supported by strong emotional bonds. Effortful control emerges as a key mediating factor in these associations, highlighting how family dynamics are related to child development through children’s self-regulation capacities.

The study findings highlight the importance of family profiles for the design of interventions to improve parenting behaviours across diverse family types in enhancing child development.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jiaqi Lu, Fang Wang; data collection: Jiaqi Lu; analysis and interpretation of results: Fang Wang, Jiaqi Lu; draft manuscript preparation: Jiaqi Lu, Fang Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of College of Preschool Education, Capital Normal University (Approval Number: EC24120115). It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Ashdown, B. K., & Faherty, A. N.(Eds.) (2020). Parents and caregivers across cultures. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35564-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baumrind, D. (2012). Differentiating between confrontive and coercive kinds of parental power-assertive disciplinary practices. Human Development, 55(2), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1159/000337962 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Behrendt, H. F., Wade, M., Bayet, L., Nelson, C. A., III, & Enlow, M. B. (2020). Pathways to social-emotional functioning in the preschool period: The role of child temperament and maternal anxiety in boys and girls. Development and Psychopathology, 32(3), 961–974. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Belsky, J. (2008). Family influences on psychological development. Psychiatry, 7(7), 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mppsy.2008.05.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, I. J., Zhang, H., Wei, B., & Guo, Z. (2019). The model of children’s social adjustment under the gender-roles absence in single-parent families. International Journal of Psychology, 54(3), 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Coe, J. L., Micalizzi, L., Huffhines, L., Seifer, R., Tyrka, A. R., & et al. (2024). Effortful control, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems among preschool-aged children experiencing adversity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 33(2), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02741-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Crnic, K. A. (2024). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: Developmental psychopathology perspectives. Development and Psychopathology, 36(5), 2369–2375. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579424001135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cui, J., Mistur, E. J., Wei, C., Lansford, J. E., Putnick, D. L., & et al. (2018). Multilevel factors affecting early socioemotional development in humans. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 72(10), 172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-018-2580-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eisenberg, N., Chang, L., Ma, Y., & Huang, X. (2009). Relations of parenting style to Chinese children’s effortful control, ego resilience, and maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 21(2), 455–477. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457940900025X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Engel, K. D., Lunkenheimer, E., & Corapci, F. (2023). Do maternal power assertive discipline and warmth interact to influence toddlers’ emotional reactivity and noncompliance? Infant and Child Development, 32(5), e2442. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2442 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Feldman, J. S., Dolcini-Catania, L. G., Wang, Y., Shaw, D. S., Nordahl, K. B., & et al. (2023). Compensatory effects of maternal and paternal supportive parenting in early childhood on children’s school-age adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 59(6), 1074–1086. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fiese, B. H., & Fisher, M. (2019). Family context in early childhood education. In: Handbook of research on the education of young children (pp. 284–301). Abingdon, UK: Talylor Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

Fiese, B. H., & Winter, M. A. (2008). Family influences. In Encyclopedia of infant and early childhood development. (vol. 1–3, pp. 492–501). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Inc. [Google Scholar]

Gartstein, M. A., & Rothbart, M. K. (2003). Studying infant temperament via the revised infant behavior questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development, 26(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-6383(02)00169-8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gartstein, M. A., Bridgett, D. J., Young, B. N., Panksepp, J., & Power T. (2013). Origins of effortful control: Infant and parent contributions. Infancy. 18(2), 149–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7078.2012.00119.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Goagoses, N., Bolz, T., Eilts, J., Schipper, N., Schütz, J., et al. (2023). Parenting dimensions/styles and emotion dysregulation in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Psychology, 42(22), 18798–18822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03037-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guo, M., Morawska, A., & Filus, A. (2017). Validation of the parenting and family adjustment scales to measure parenting skills and family adjustment in Chinese parents. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 50(3), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2017.1320947 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lamb, M. E. (2012). Mothers, fathers, families, and circumstances: factors affecting children’s adjustment. Applied Developmental Science, 16(2), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2012.667344 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lansford, J. E. (2017). An international perspective on parenting and children’s adjustment. In: Handbook on positive development of minority children and youth (pp. 107–122). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43645-6_7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lansford, J. E., Godwin, J., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Bornstein, M. H., et al. (2018). Longitudinal associations between parenting andyouth adjustment in twelve cultural groups: Cultural normativeness of parenting as a moderator. Developmental Psychology, 54(2), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, Y., Cui, N., Kok, H. T., Deatrick, J., & Liu, J. (2019). The relationship between parenting styles practiced by grandparents and children’s emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(7), 1899–1913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01415-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Liu, Y., & Merritt, D. H. (2018). Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression among Chinese children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Children and Youth Services Review, 88(6), 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.019 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, L. L., Wang, M., & Zhao, J. (2022). Parental reports of stress and anxiety in their migrant children in China: The mediating role of parental psychological aggression and corporal punishment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 131(1), 105695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lu, H. J., Zhu, N., Chen, B. B., & Chang, L. (2023). Cultural values, parenting, and child adjustment in China. International Journal of Psychology, 59(4), 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.13100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Luo, R., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Song, L. (2013). Chinese parents’ goals and practices in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(4), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.08.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mortensen, J. A., & Barnett, M. A. (2019). Intrusive parenting, teacher sensitivity, and negative emotionality on the development of emotion regulation in early head start toddlers. Infant Behavior and Development, 55, 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2019.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pereira, A. M., Pereira, A. I., & Marques, T. (2021). Effortful control assessed by parental report and laboratory observation and adjustment in early childhood. Analise Psicologica, 39(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14417/ap.1742 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Petrenko, A., Kanya, M. J., Rosinski, L., McKay, E. R., & Bridgett, D. J. (2019). Effects of infant negative affect and contextual factors on infant regulatory capacity: The moderating role of infant sex. Infant and Child Development, 28(6), 64. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2157 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Planalp, E. M., Braungart-Rieker, J. M., Lickenbrock, D. M., & Zentall, S. R. (2013). Trajectories of parenting during infancy: The role of infant temperament and marital adjustment for mothers and fathers. Infancy, L(1), E16–E45. https://doi.org/10.1111/infa.12021 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pontoppidan, M., Niss, N. K., Pejtersen, J. H., Julian, M. M., & Væver, M. S. (2017). Parent report measures of infant and toddler social-emotional development: A systematic review. Family Practice, 34(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmx003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Preston, K. S. J., Pizano, N. K., Garner, K. M., Gottfried, A. W., Gottfried, A. E., et al. (2022). Identifying family personality profiles using latent profile analysis: Relations to happiness and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 189(4), 111480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111480 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Putnam, S. P., Gartstein, M. A., & Rothbart, M. K. (2006). Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: The early childhood behavior questionnaire. Infant Behavior and Development, 29(3), 386–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Qi, Z., & Du, Y. (2020). Chinese parenting and the collective desirable path through sociopolitical changes. In: B. K. Ashdown, A. N. Faherty (Eds.Parents and caregivers across cultures. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-35590-6_9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Qiu, C., & Shum, K. K. M. (2022). Relations between caregivers’ emotion regulation strategies, parenting styles, and preschoolers’ emotional competence in Chinese parenting and grandparenting. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 59(4), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.11.012 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Repetti, R. L., Sears, M. S., & Bai, S. (2015). Social and emotional development in the context of the family. In: International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences: Second edition (pp. 156–161). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

Roubinov, D. S., & Boyce, W. T. (2017). Parenting and SES: Relative values or enduring principles? Current Opinion in Psychology, 15(5), 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sanders, M. R., Morawska, A., Haslam, D. M., Filus, A., & Fletcher, R. (2014). Parenting and family adjustment scales (PAFASValidation of a brief parent-report measure for use in assessment of parenting skills and family relationships. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45(3), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0397-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Santens, E., Claes, L., Dierckx, E., & Dom, G. (2020). Effortful control–A transdiagnostic dimension underlying internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Neuropsychobiology, 79(4–5), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1159/000506134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Scaramella, L. V., & Leve, L. D. (2004). Clarifying parent-child reciprocities during early childhood: The early childhood coercion model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7(2), 89–107. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:CCFP.0000030287.13160.a3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Skinner, A. T., Gurdal, S., Chang, L., Oburu, P., & Tapanya, S. (2022). Dyadic coping, parental warmth, and adolescent externalizing behavior in four countries. Journal of Family Issues, 43(1), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X21993851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Smetana, J. G. (2017). Current research on parenting styles, dimensions, and beliefs. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Spera, C. (2005). A review of the relationship among parenting practices, parenting styles, and adolescent school achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 125–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-005-3950-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Gaertner, B., Popp, T., Smith, C. L., et al. (2007). Relations of maternal socialization and toddlers’ effortful control to children’s adjustment and social competence. Developmental Psychology, 43(5), 1170–1186. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Squires, J., Bricker, D., & Twombly, E. (2015). Ages & Stages Questionnaires®: Social-Emotional, Second Edition (ASQ®: SE-2A parent-completed child monitoring system for social-emotional behaviors. Baltimore, ML, USA: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

Thompson, S., Hiebert-Murphy, D., & Trute, B. (2013). Parental perceptions of family adjustment in childhood developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 17(1), 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629512472618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Væver, M. S., Smith-Nielsen, J., & Lange, T. (2016). Copenhagen infant mental health project: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial comparing circle of security-parenting and care as usual as interventions targeting infant mental health risks. BMC Psychology, 4(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0166-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, H., Han, Z. R., Yan, J. J., Ahemaitijiang, N., & Hui, M. (2020). Dispositional mindfulness moderates the relationship between family risks and Chinese parents’ mental health. Mindfulness, 12(3), 672–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01529-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Whiteside-Mansell, L., Bradley, R. H., McKelvey, L., & Fussell, J. J. (2009). Parenting: Linking impacts of interpartner conflict to preschool children’s social behavior. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 24(5), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2007.08.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wu, M. Y. (2012). The concept of guan in the Chinese parent-child relationship. In: The psychological wellbeing of East Asian youth (pp. 29–49). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4081-5_2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xie, H., Waschl, N., Bian, X., Wang, R., Chen, C-Y., et al. (2021). Validity studies of a parent-completed social-emotional measure in a representative sample in China. Applied Developmental Science, 25(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2021.1977642 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xu, Y., Farver, J. A. M., Zhang, Z., Zeng, Q., Yu, L., et al. (2005). Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent-child interaction. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250500147121 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhong, J., He, Y., Chen, Y., & Luo, R. (2020). Relationships between parenting skills and early childhood development in rural households in western China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Rudolph, J., Kerin, J., & Bohadana-Brown, G. (2022). Parent emotional regulation: A meta-analytic review of its association with parenting and child adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46(1), 63–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/01650254211051086 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools