Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Perceived teacher autonomy support and college students’ creativity: The mediating role of academic engagement and the moderating role of emotions

1 Faculty of Language Studies and Human Development, University Malaysia Kelantan, Kota Baru, 16100, Malaysia

2 Faculty of Arts and Law, Nanchang Institute of Technology, Nanchang, 330044, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiao Huang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 641-650. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.066349

Received 06 April 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study examined the perceived teacher autonomy support effects on college students’ creativity, and the role of academic engagement and affect (positive and negative emotions) in that relationship. The study sample comprised 637 undergraduates (366 females, 271 males). Results from structural equation modelling with a moderated mediation framework indicated that perceived teacher autonomy support positively predicted college students’ self-reported creativity. Academic engagement partially mediated the relationship between autonomy support and creativity, whereby higher perceived autonomy support predicted greater academic engagement, which subsequently promoted creativity. Both positive and negative emotions strengthened the link between autonomy support and engagement; high levels of positive and negative emotions triggered stronger moderation than low states. These findings align with Self-Determination Theory and affective perspectives, indicating that both positive and context-dependent negative emotions can enhance engagement in supportive contexts. Implications highlight the importance of autonomy-supportive teaching and emotional regulation strategies to foster creativity.Keywords

In the field of higher education, research on innovation and entrepreneurship has attracted increasing attention in recent years, with university students, as the main agents of such behaviors, gaining considerable academic interest (Cui et al., 2024; Nabi et al., 2017). In this study, creativity is defined as the capacity to generate ideas, solutions, or products that are both novel and appropriate within a specific context (Runco & Jaeger, 2012). It is widely regarded as a critical prerequisite and a core indicator of innovation, as well as a key learning outcome within educational assessment frameworks (Shu et al., 2020). While creativity is closely related to innovation, the two are not synonymous: creativity emphasises the cognitive and imaginative processes involved in idea generation, whereas innovation focuses on the practical application and transformation of these ideas (Sawyer & Henriksen, 2023). To adapt to real-time changes, foster innovation, and resolve increasingly complex difficulties, creativity has become an essential resource for individual development (Aldosari & Alsager, 2023). However, compared with other subfields in psychology, the research on creativity remains relatively limited (Sawyer & Henriksen, 2023). Therefore, examining creativity as an independent yet fundamental component of innovation not only contributes to the refinement of the theoretical framework, but also offers valuable insights into strategies for fostering students’ creativity within higher education.

As central figures in instructional practice and teacher–student interaction, educators play a pivotal role in cultivating individuals equipped with creativity and an innovative mindset, especially within education-oriented societies (Vermeulen et al., 2022). Teachers can effectively nurture students’ creativity by providing a safe and supportive learning environment and engaging in targeted, differentiated instructional strategies (Mostafavi et al., 2020). Nonetheless, the influence of teacher support on student creativity has not been thoroughly investigated. Autonomy support, a key concept in SDT, refers to teachers encouraging students to initiate learning, think independently, and make meaningful choices (Deci & Ryan, 2000). According to SDT, when the learning environment—particularly the classroom context shaped by the teacher—meets students’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, intrinsic motivation is strengthened, engagement is enhanced, and creativity is more likely to flourish (Richardson & Mishra, 2018; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Cui et al., 2024). This theoretical framework provides the basis for examining the mechanisms and boundary conditions through which teacher autonomy support may influence creativity.

However, not all teachers succeed in establishing autonomy-supportive environments conducive to creativity development (Salmanpour et al., 2024), suggesting that other unexamined factors may mediate or moderate the relationship between teacher autonomy support and student creativity. Previous studies have shown that when teachers support students’ learning goals and behaviors through instructional strategies, students’ academic engagement is positively stimulated (Reeve et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022). Notably, the degree of student participation and engagement in learning processes is one of the key factors influencing creativity development (Miller & Dumford, 2016). To the best of our knowledge, existing research has yet to provide conclusive evidence linking student academic engagement with creativity (Alvarez-Huerta et al., 2021). Moreover, although there is a growing body of literature exploring the connection between teacher autonomy support and academic engagement, few studies offer a comprehensive analysis of this relationship (Yang et al., 2022), and there remains a lack of research investigating academic engagement as a mediating variable in the link between teacher autonomy support and student creativity.

Furthermore, emotions—both positive and negative—can significantly influence students’ motivation and creativity (Fredrickson, 2001). It is therefore necessary to broaden the scope of emotion-related research and explore the relationship between students’ emotions and academic engagement (Linnenbrink-Garcia & Pekrun, 2011). Although SDT often treats emotion as a consequence of motivational processes, recent studies increasingly highlight the role of emotion as a preceding factor in these dynamics (Printer, 2023). Emotional experiences can expand individuals’ cognitive flexibility and promote proactive behavior, while also helping them accumulate various personal resources and capacities (Fredrickson, 2001). To avoid the limitations of treating emotion merely as an outcome or antecedent, the present study positions emotion (both positive and negative) as a moderating variable.

However, the moderating role of emotions in the relationship between perceived teacher autonomy support and academic engagement remains underexplored. This study addresses this gap by testing a moderated mediation model that integrates teacher autonomy support, emotions, academic engagement, and creativity. In doing so, it contributes to Self-Determination Theory by clarifying the motivational mechanisms through which autonomy support fosters creativity, highlights the dual role of positive and negative emotions as contextual factors shaping engagement, and advances the literature by applying a moderated mediation framework. Overall, this study aims to provide theoretical insights into the interaction between social contexts and psychological processes, while offering practical guidance on fostering creativity through supportive classroom environments.

Teacher autonomy support and creativity

Teacher autonomy support, within Self-Determination Theory, involves recognising students’ perspectives, providing choices and learning materials, and fostering students’ autonomy in their learning. Recent studies in online and classroom settings have demonstrated that such autonomy support, including perspective-taking, value/interest support, and reduced controlling behaviour, significantly enhances students’ motivation, self-efficacy, and learning engagement (Miao & Ma, 2023; Reeve & Cheon, 2024). Teacher assistance provides students with knowledge, skills, and experiences, fostering an autonomous classroom environment (Orakci & Durnali, 2023). Teachers facilitate students’ comprehension and engagement with subject matter and promote their ability to autonomously and critically address real-world learning challenges (Fu et al., 2023). In a teacher-supported learning environment, students do not feel pressured, willingly participate in learning, and are motivated by the teacher to accomplish educational objectives (Ryan & Deci, 2004).

According to SDT, when teachers create an autonomy-supportive environment that fulfils students’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, students are more likely to engage deeply in learning, exhibit higher intrinsic motivation, and apply creative thinking in problem-solving (Jang et al., 2010; Tegeh et al., 2022). This theoretical perspective provides a clear rationale for anticipating a positive relationship between students’ perceived teacher autonomy support and their creativity.

Initial studies indicate that educators communicate the importance they attribute to creativity and promote it in the classroom using diverse messages and strategies (Hennessey & Amabile, 1987; Runco & Johnson, 2002). Soh (2017) posits that teachers assist students in problem-solving and managing frustrations by utilising diverse materials and providing a comprehensive array of learning resources. This supportive teaching behaviour fosters the development of students’ creativity. Teachers should encourage students to engage in creative activities by emphasising the final creative products and the cognitive and behavioural processes demonstrated throughout the creative journey (Beghetto, 2007).

The mediating role of academic engagement

Academic engagement has garnered significant attention from researchers and is crucial for both academic success and outcomes (Gutiérrez & Tomás, 2019; Oriol-Granado et al., 2017). Students’ engagement in school encompasses behavioural, affective, and cognitive dimensions, aiming to capture the comprehensive spectrum of their contributions and interactions within the learning process (Fredricks et al., 2004). Within the SDT framework, autonomy-supportive teaching enhances academic engagement by fulfilling students’ psychological needs, thereby promoting greater willingness to invest effort, explore ideas, and persist in challenging tasks, which are behaviours closely tied to creativity development (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Patzak & Zhang, 2025).

Research has shown that students’ academic engagement is a significant predictor of their beliefs in creative confidence (Alvarez-Huerta et al., 2021). Furthermore, motivation and robust engagement are essential components for stimulating and achieving creativity (Yuan et al., 2019). While prior studies have examined direct and indirect relationships between teacher autonomy support, engagement, and creativity, the mediating role of engagement in this pathway remains underexplored.

The moderating role of emotions

The emotions displayed by students throughout learning activities and outcomes are termed academic emotions (Pekrun et al., 2007). For instance, Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2012) contended that emotions, as an important experience of students’ learning environments, can profoundly influence students’ involvement and performance in learning. According to the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, 2001), positive emotions expand individuals’ thought–action repertoires, fostering cognitive flexibility, openness to new experiences, and proactive behaviours, which in turn enhance academic engagement (Oriol-Granado et al., 2017). From an SDT perspective, emotions can function as contextual factors that either facilitate or hinder academic engagement initiated by autonomy-supportive teaching (Shen et al., 2024). Within autonomy-supportive learning environments, such broadened cognitive and behavioural tendencies may amplify students’ willingness to invest effort and persist in learning tasks, thereby facilitating creative outcomes.

While positive emotions are generally associated with beneficial academic and creative outcomes, evidence suggests that certain negative emotions, particularly activated forms such as frustration or dissatisfaction, can also, under specific conditions, play a constructive role. Control-Value Theory proposes that when learners perceive adequate control over a valued task, negative achievement emotions can signal a discrepancy between current and desired performance, prompting corrective and effortful behaviour (Pekrun et al., 2007). Supporting this perspective, Nelson et al. (2018) found that encouraging and supporting individuals to experience and acknowledge their emotional reactions to failure increased subsequent task-focused effort and reduced self-protective cognitions that otherwise inhibit improvement. In the context of autonomy-supportive teaching, such emotionally driven motivation may transform the potentially detrimental effects of negative emotions into catalysts for deeper engagement and persistence.

Drawing on these perspectives, the present study conceptualises emotions as moderators in the link between perceived teacher autonomy support and academic engagement. For a more complete understanding of the teacher autonomy and student creative potential, there is need to examine the role of both positive and negative emotions (Lai & Wu, 2019).

This stidy examined the perceived teacher autonomy support effects on college students’ creativity, and the role of academic engagement and affect (positive and negative emotions) in that relationship. We tested three research hypotheses based on our conceptual model (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Research framework diagram

Hypothesis 1: Perceived teacher autonomy support predicts student creativity with academic engagement.

Hypothesis 2: Academic engagement mediates the relationship between teacher autonomy support and creativity for higher student creativity potential.

Hypothesis 3: Both positive and negative emotions positively regulate the relationship between teacher autonomy support and academic engagement.

Hypothesis 4: The indirect effect of perceived teacher autonomy support on students’ creativity through academic engagement is moderated by emotions (both positive and negative).

A random sample survey was administered to Chinese university students between 16 February and 18 May 2024. Prior to data collection, all participants were informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Written informed consent was obtained, with assurances of confidentiality and anonymity and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Respondents completed the questionnaire independently within the first two weeks of recruitment. After excluding invalid responses, 637 valid questionnaires were retained from the 698 distributed, yielding an effective response rate of 91.3%. The final sample comprised 366 females (57.5%) and 271 males (42.5%), with no restrictions on academic major. Participants included 126 first-year students (19.8%), 257 second-year students (40.3%), 89 third-year students (14.0%), and 165 fourth-year students (25.9%).

Teacher autonomy support scale

The Teacher Autonomy Support Scale (TASS: Williams & Deci, 1996), comprises six items. Sample statements include “I feel that my teacher provides me with choices and options”, “My teacher encourages me to ask questions” and “My teacher tries to understand how I see things before suggesting a new way to do things”. The scale utilises a 5-point Likert format, where the total score is the aggregate of all responses, with elevated scores signifying greater autonomy support from the teacher in the classroom. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for TASS exceeds 0.89 in prior research (Jang et al., 2012). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for TASS scores was 0.91, with the validated factor analysis results as follows: χ2/df = 3.58 (p < 0.001), GFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.06, and SRMR = 0.02.

The Academic Engagement Scale (ASE: Schreiner & Louis, 2011), comprises 10 items, featuring statements such as “I often discuss with my friends what I’m learning in class”, “I feel as though I am learning things in my classes that are worthwhile to me as a person” and “I can usually find ways of applying what I’m learning in class to something else in my life”. The statements”It is hard to pay attention in many of my classes” and “In the last week, I’ve been bored in class a lot of the time” were inverted. The scale utilises a 5-point Likert format, with the total score representing the aggregate of all entries; higher scores signify enhanced participation in the learning process. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for ASE scores is 0.80, as reported in previous studies (Heo et al., 2021). The Cronbach’s α coefficient for ASE scores in the study was 0.94, and the findings of the validated factor analysis were: χ2/df = 3.90 (p < 0.001), GFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.02.

The Emotion Scale (ES: Watson et al., 1988) comprises 20 items on two dimensions: positive emotion (10 items, e.g., interested, excited, enthusiastic, proud, inspired)and negative emotion (10 items, e.g., distressed, upset, guilty, nervous, afraid). Participants rated the extent to which they had experienced each emotion during the past few weeks on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Elevated scores in positive emotions signify that individuals encounter an increased frequency of positive feelings, whilst elevated scores in negative emotions denote that individuals experience a greater prevalence of negative emotions. The current study revealed a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.95 for positive emotions and 0.93 for negative emotions. The validated factor analyses in this study yielded the following results: χ2/df = 2.98 (p < 0.001), GFI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.03.

The Creativity Scale (CS: Miller & Dumford, 2016) comprises 7 items. It includes items such as “Tried to generate as many ideas as possible when approaching a task”, “Asked other people to help generate potential solutions to a problem”, and”Incorporated a previously used solution in a new way”. A four-point Likert scale was employed, with the total score representing the sum of all entries, where higher scores signify an increased probability of student creativity. The Cronbach’s α coefficient for CS scores in the present study was 0.89, with validated factor analysis results as follows: χ2/df = 3.94 (p < 0.001), GFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSE = 0.07, SRMR = 0.03.

The research examined the mediating effect with teacher self-support as the independent variable, students’ creativity as the dependent variable, age as a control variable, and academic engagements as the mediating variable. All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0. To examine the hypothesised mediation and moderation effects, we employed Hayes’ PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 4.2), which is capable of estimating bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals for indirect effects. Specifically, Model 7 of PROCESS was used to test the moderated mediation model, with 5000 bootstrap resamples generating 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals. Descriptive statistics, reliability coefficients, and correlation analyses were first computed to examine the preliminary relationships among the variables. All continuous variables were mean-centred prior to the analysis to reduce multicollinearity.

This study employed KMO and Bartlett’s Sphericity tests utilising SPSS 26.0, yielding a KMO value of 0.96, approximate χ2 = 18,787.12, df = 903, p < 0.001, signifying that the data were highly appropriate for exploratory component analysis. The data obtained from this study were further tested for common method bias using Harman’s one-way test. The results of exploratory factor analysis showed that a total of five eigenroot factors greater than one were analysed, with the first of these explaining 31.85% of the total variance, which is less than the critical value of 40% (Harman, 1976). In addition, a validated factor analysis with a set number of common factors of 1 showed a poor fit to the one-way model (χ2/df = 12.40 (p < 0.001), GFI = 0.35, CFI = 0.47, TLI = 0.44, RMSEA = 0.13). Consequently, it can be assumed that the data of this study do not suffer from serious common methodological bias.

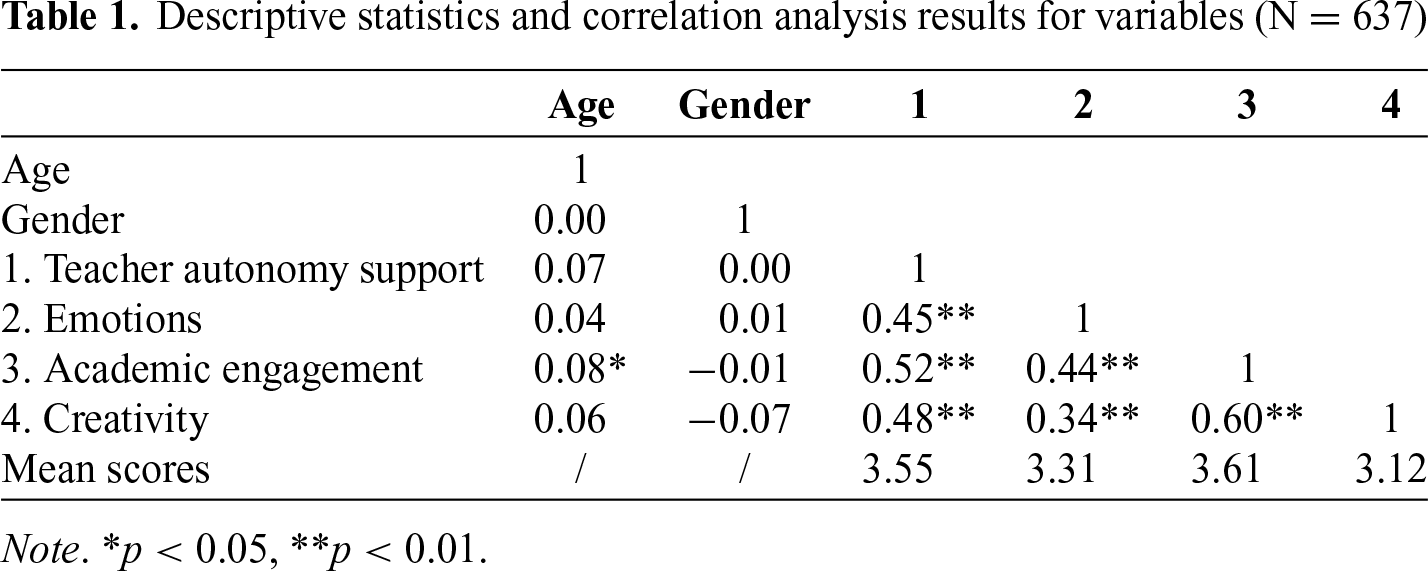

From Table 1, the Pearson’s product-moment correlation analysis indicated a significant positive correlation between teacher autonomy support and positive emotions (r = 0.52, p < 0.01) as well as negative emotions (r = 0.13, p < 0.01). Additionally, teacher autonomy support exhibited a significant positive correlation with emotions (r = 0.45, p < 0.01), academic engagement (r = 0.52, p < 0.01), and creativity (r = 0.48, p < 0.01). Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was observed between emotions and both academic engagement (r = 0.44, p < 0.01) and creativity (r = 0.34, p < 0.01). Lastly, a significant positive correlation was found between academic engagement and creativity (r = 0.60, p < 0.01). Gender was not correlated with any of the main variables, and there was a significant positive correlation between age and academic engagement (r = 0.08, p < 0.01), so age needs to be included in the consideration of variable control when conducting subsequent analyses.

On a five-point scale, mean scores were 3.55 for perceived teacher autonomy support, 3.31 for overall emotions (combined positive and negative affect), 3.61 for academic engagement, and 3.12 for creativity, indicating generally moderate to moderately high levels across variables.

Teacher autonomy support and student creativity potential

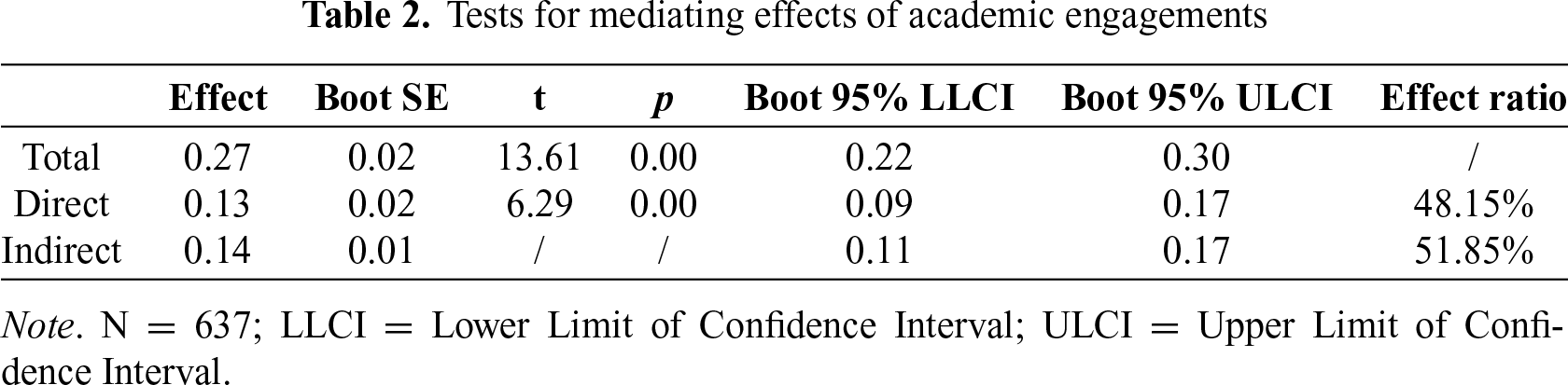

The results of Table 2 indicated that students’ perception of teacher self-support considerably and positively influenced their creativity (β = 0.27, p < 0.001), the findings support Hypothesis 1. Upon the introduction of academic engagement, teacher autonomy support demonstrated a strong positive predictive relationship with academic engagement (β = 0.49, p < 0.001), which in turn exhibited a substantial positive predictive relationship with creativity (β = 0.28, p < 0.001). Simultaneously, the influence of teacher autonomy support on creativity was considerable (β = 0.13, p < 0.001). The bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap method test indicated that the direct effect of teacher autonomy support on creativity was 0.13. The mediating effect of academic engagement between teacher autonomy support and creativity was significant, with an indirect effect value of 0.14, Boot SE = 0.01. The proportion of the indirect effect to the total effect was 51.85 per cent, and the 95 per cent confidence interval [0.11, 0.17] does not include 0, suggesting that academic engagement can indirectly influence the development of students’ creativity. So the results support Hypothesis 2.

Testing the moderating effects of emotions

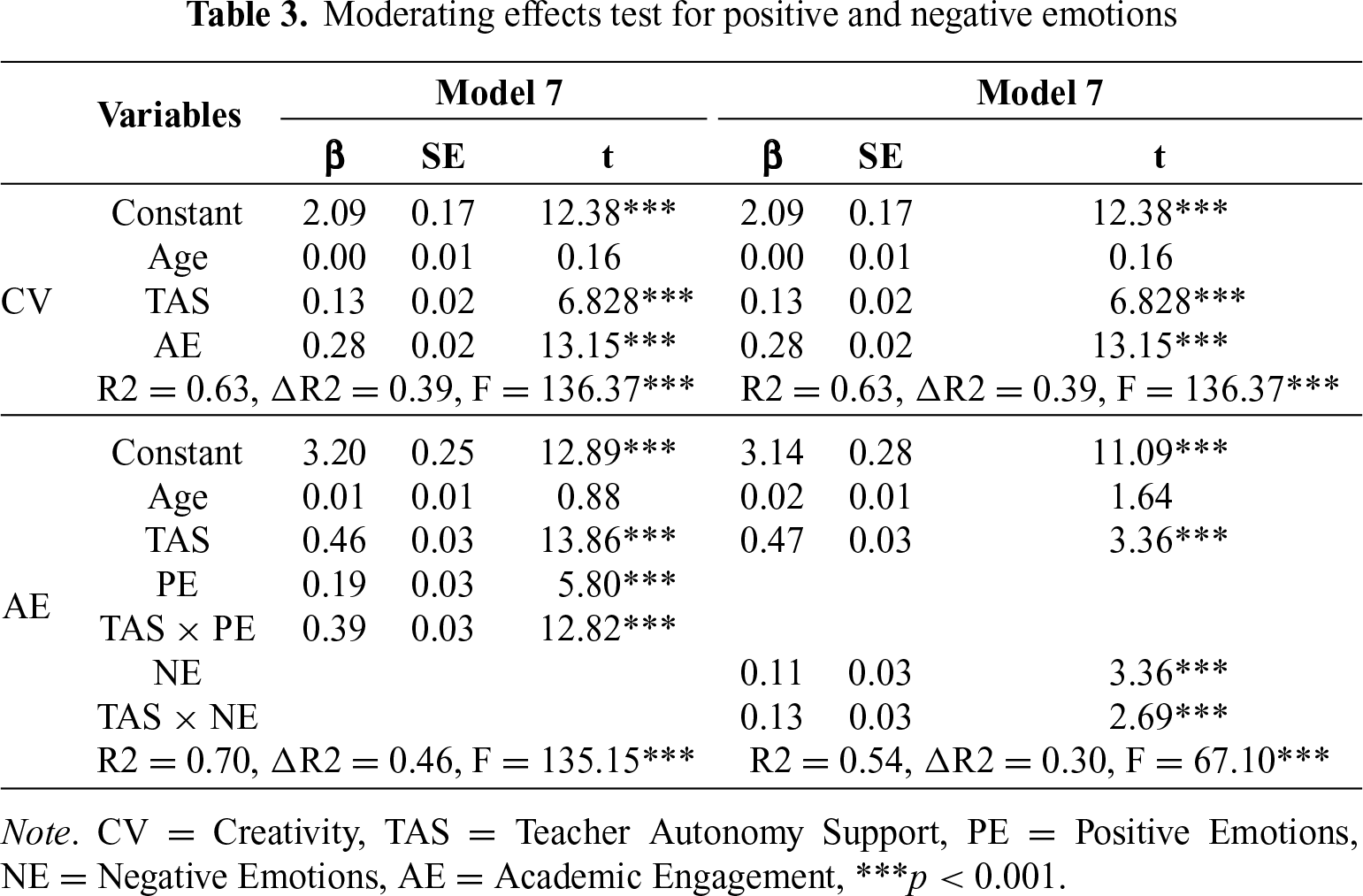

The findings presented in Table 3 indicate that the interaction between teacher autonomy support and positive emotions significantly predicts academic engagement (β = 0.39, p < 0.001). The 95% confidence interval [0.40, 0.53] excludes 0, implying that students’ positive emotions serve as a moderator in the relationship between teacher autonomy support and academic engagement. The interaction between teacher autonomy support and negative emotions significantly predicted academic engagement (β = 0.13, p < 0.001), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.41, 0.54] that did not include 0. This indicates that negative emotions moderated the relationship between teacher autonomy support and academic engagement. The data indicate that students’ positive emotions exert a more significant moderating effect on the relationship between teacher autonomy support and academic engagement compared to negative emotions.

To elucidate the moderating effects of positive and negative emotions on the link between teacher autonomy support and academic engagement, simple slope analyses were employed to examine the moderating functions of each emotion individually. Initially, positive emotions were categorised into a high positive emotion group and a low positive emotion group, and the impact of autonomy support from teachers on academic engagement was evaluated for each group of students independently. The findings illustrated in Figure 2 demonstrate that students exhibiting elevated positive emotions experience a substantial increase in academic engagement as teacher autonomy support rises (βsimple = 0.84, p < 0.001); conversely, students with diminished positive emotions also show a notable increase in academic engagement with heightened teacher autonomy support (βsimple = 0.08, p < 0.05). This indicates that the influence of teacher autonomy support on academic engagement is more pronounced in students exhibiting elevated levels of positive affect.

Figure 2: The moderating role of positive emotions

Secondly, negative emotions were classified into high and low negative emotion groups to examine the impact of teacher autonomy support on students’ academic engagement. The findings illustrated in Figure 3 indicate that for students exhibiting elevated negative emotions, academic engagement tends to rise with increased teacher autonomy support (βsimple = 0.59, p < 0.001). Conversely, for students with diminished negative emotions, academic engagement significantly increases with heightened teacher autonomy support (βsimple = 0.36, p < 0.001). This indicates that the predictive effect of teacher autonomy support on academic engagement was greater among students who possessed higher levels of negative affect. Thus, when moderating the relationship between teacher autonomy support and creativity, high levels of positive affect had a stronger moderating effect than high levels of negative affect. Based on the above results, research hypothesis 3 is supported.

Figure 3: The moderating role of negative emotions

To further examine whether emotions moderated the indirect effect of teacher autonomy support on creativity via academic engagement, we tested a moderated mediation model. The moderated mediation analysis revealed significant indices for both positive emotions (BootSE = 0.013, 95% CI [0.085, 0.135]) and negative emotions (BootSE = 0.010, 95% CI [0.017, 0.056]). These findings indicate that the indirect effect of teacher autonomy support on creativity via academic engagement varies by students’ emotional states. Positive emotions exerted a stronger moderating effect, while negative emotions also facilitated the indirect pathway, albeit to a lesser degree. Based on these results, Hypothesis 4 is supported, demonstrating that both positive and negative emotions moderate the pathway from teacher autonomy support through academic engagement to creativity.

This study revealed that students’ perception of teacher autonomy support significantly predicts their creativity, aligning with the findings of Richardson and Mishra (2018). This outcome confirms the multifaceted desire for teacher autonomy support and enhances the explanatory capacity of Self-Determination Theory in fostering student creativity. In a trustworthy and completely supportive atmosphere, students effectively utilise learning materials and resources to interact freely and resolve problems (Ryan & Deci, 2004; Soh, 2017). Students actively participate in learning and exploration, develop and resolve new challenges through transformation, and foster innovation (Sawyer & Henriksen, 2023). The aim of fostering creativity transcends mere active learning and exploration by students, as well as the attainment of teacher-established objectives; it underscores the importance of the learning process within a supportive environment (Richardson & Mishra, 2018). As an educator, it is essential to foster students’ creative endeavours promptly and to appreciate their innovative actions and thought processes (Beghetto, 2007). This implies that concentrating solely on the pragmatic applications and objectives of creativity may consequently restrict the environment in which creativity might thrive. Consequently, a comprehensive study of the correlation between teacher autonomy support and creativity aims to enhance the learning environment for students and to cultivate creativity as an intrinsic characteristic of the students.

The research finding further indicated that students’ perception of instructor autonomy influences their creativity via learning engagement, a conclusion consistent with Reeve et al. (2020). The researchers observed that a supportive learning environment, coupled with teacher autonomy, can enhance resilience by encouraging students’ purposeful participation in learning. Aldosari and Alsager (2023) assert that creative individuals possess superior coping, innovation, and problem-solving abilities. Collectively, resilience may be perceived as an indicator of creativity. Research indicates that individuals enhance their creativity in response to their surrounding environment (Forgeard, 2024). The classroom setting is crucial for students’ creative development. Students’ academic engagement is significantly improved when they have experiential teaching and learning activities from educators who create an atmosphere that aligns their learning interests with their psychological requirements (Wang et al., 2017). Rather than concentrating on students’ academic achievements and performance, educators cultivate a secure, supportive, and transparent classroom environment that inspires student participation in activities (Yuan et al., 2019). When students demonstrate a robust eagerness to participate in significant learning activities and embrace tough endeavours, it serves as compelling proof of their emerging creative behaviours (Beghetto & Schreiber, 2017; Yuan et al., 2019). Consequently, enhancing creativity through a supportive atmosphere is more advantageous after incorporating a fresh viewpoint on learning engagement, as this focus significantly contributes to the development of students’ creativity.

In addition, finding indicated that both positive and negative emotions positively modulated the impact of teacher autonomy support on academic engagement. In addition, the findings indicated that both positive and negative emotions significantly moderated the relationship between teacher autonomy support and academic engagement. Consistent with prior research, students benefiting from autonomy-supportive teaching reported heightened positive affect, which in turn facilitated engagement and learning outcomes (Patrick et al., 1993; Oriol-Granado et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2019). Within the SDT framework, such environments satisfy students’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, thereby fostering positive dispositions and sustained engagement (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Hardre & Reeve, 2003). Moreover, students with higher levels of positive emotions demonstrated a stronger predictive effect of teacher autonomy support on creativity. This suggests that positive affect amplifies the engagement pathway, increasing motivation, persistence, and creative outcomes (Sadoughi & Hejazi, 2021).

Importantly, the study also confirmed that negative emotions can exert constructive influences. While prior studies suggest that negative emotions may undermine effort (Li et al., 2025), the present results indicate that, under conditions of strong teacher autonomy support, students experiencing higher levels of negative emotions showed greater academic engagement than their low-negative counterparts. This finding resonates with evidence that certain activated negative emotions, such as frustration, can stimulate perseverance and adaptive coping (Chaaya et al., 2025), thereby reinforcing engagement rather than diminishing it (Pekrun et al., 2002).

Furthermore, the moderated mediation analysis demonstrated that both positive and negative emotions influenced the indirect pathway from teacher autonomy support to creativity through academic engagement. An experimental study has confirmed that under specific conditions, negative emotions can be associated with higher academic or creative engagement (Akinola & Mendes, 2008). This indicates that when students perceive strong teacher autonomy support, even in a negative emotional state, they can promptly adjust their academic engagement to enhance their creativity levels.

Implications for Research and Practice

This study has several theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, it advances Self-Determination Theory by showing that academic engagement serves as a key psychological mechanism through which autonomy support fosters creativity, while emotions act as contextual factors that shape the strength of these processes. This study contributes to the literature by clarifying the dual role of emotions in the educational process. While positive emotions are generally associated with beneficial outcomes, our findings indicate that negative emotions can also play a constructive role by positively moderating the association between teacher autonomy support and academic engagement. This challenges the prevailing notion that negative emotions should always be eliminated, and instead advances a more balanced perspective recognising their potential adaptive functions (Chaaya et al., 2025). In this sense, students who receive substantial autonomy support from teachers may leverage both positive and negative emotional experiences to sustain effort and foster deeper engagement.

Practically, the results underscore the pivotal role of teachers in cultivating autonomy-supportive classroom climates that nurture engagement and creativity. Practices such as offering meaningful choices, acknowledging students’ perspectives, and recognising effort regardless of outcomes can sustain students’ participation in creative activities (Beghetto, 2007; Yuan et al., 2019). Crucially, teachers should aim not only to foster positive emotions but also to channel negative emotions productively, enabling students to use them as motivational resources within safe, supportive, and open learning environments (Lawman & Wilson, 2013; Roeser et al., 1996).

Limitations and Future Directions

Numerous limitations must be acknowledged while analysing the study’s conclusions. Initially, the data acquired in this study stemmed from the participants’ self-reports, which may not adequately reflect individual subjectivity in data analysis; also, the scope and depth of the measurement constructs require future expansion. Future studies should incorporate a more extensive qualitative data analysis, including supplementary interviews, to elucidate the findings in greater detail.

Secondly, the research participants in this study were exclusively Chinese university students, indicating that the findings may have limitations regarding cross-cultural generalisability. Despite researchers from various nations examining the enhancement of student creativity through teacher autonomy support, there is a paucity of studies investigating the primary indicator of heightened academic engagement. Consequently, further research may be undertaken in diverse cultural settings to ascertain the generalisability of this study’s findings.

Third, our study involved individuals from several disciplines, and there is no assurance that the findings are fundamentally robust among those specialising in specific fields. Consequently, other researchers are encouraged to examine various disciplines to provide more compelling proof for the conclusions.

Finally, this study employed emotion as a moderating variable and established that positive and negative emotions influenced the link between teacher autonomy support and creativity. Nevertheless, concentrated emphasis was absent on a more precise classification of the two emotions categories: happiness, perseverance, and contentment, and sadness, worry, and fear within negative emotions. Future research could further delineate the classification of emotions to enhance findings and broaden the study’s depth and breadth to some degree.

This study demonstrated that teacher autonomy support fosters students’ creativity, with academic engagement serving as a partial mediator. Both positive and negative emotions moderated the effect of autonomy support on engagement, with stronger impacts under high emotional intensity. This implies that the constructive value of negative emotions has also been substantiated in this study. These findings advance understanding of the mechanisms linking autonomy support to creativity and highlight the importance of fostering supportive classroom environments that leverage both positive and negative emotions to sustain engagement and innovation.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank all the students who generously contributed their time to participate in this study. We are also grateful to Li Zhen and Yan Luo for their valuable assistance in the conduct of the research and the collection of data.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiao Huang, Suqing Chen; data collection: Xiao Huang; analysis and interpretation of results: Xiao Huang, Suqing Chen, Fairuz A’dilah Binti Rusdi; draft manuscript preparation: Xiao Huang, Fairuz A’dilah Binti Rusdi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Xiao Huang], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Metaverse Industrial College of Jiangxi University of Science and Technology (Approval Number: 2024-0208). Although this committee is not directly affiliated with the authors’ current institution, it was responsible for overseeing research involving Chinese university students, who were the participants of this study.

Informed Consent: To ensure participant privacy and ethical compliance, all participants were informed of the purpose and procedures of the study and provided their signed informed consent.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Akinola, M., & Mendes, W. B. (2008). The dark side of creativity: Biological vulnerability and negative emotions lead to greater artistic creativity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(12), 1677–1686. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208323933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Aldosari, M. S., & Alsager, H. N. (2023). A step toward autonomy in education: Probing into the effects of practicing self-assessment, resilience, and creativity in task supported language learning. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 434. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01478-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Alvarez-Huerta, P., Muela, A., & Larrea, I. (2021). Student engagement and creative confidence beliefs in higher education. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40(2), 100821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2021.100821 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beghetto, R. A. (2007). Ideational code-switching: Walking the talk about supporting student creativity in the classroom. Roeper Review, 29(4), 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783190709554421 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beghetto, R. A., Schreiber, J. B. (2017). Creativity in doubt: Toward understanding what drives creativity in learning. In: R. Leikin, B. Sriraman (Eds.Creativity and giftedness: Interdisciplinary perspectives from mathematics and beyond (pp. 147–162Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38840-3_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chaaya, R., Sfeir, M., Khoury, S. E., Malhab, S. B., & Khoury-Malhame, M. E. (2025). Adaptive versus maladaptive coping strategies: insight from Lebanese young adults navigating multiple crises. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1464. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22608-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cui, G., Zhao, Z., Yuan, C., Du, Y., Yan, Y., et al. (2024). The influence of teachers’ autonomy support on students’ entrepreneurial enthusiasm: A mediation model with student gender as a moderator. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(2), 100966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2024.100966 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Forgeard, M. (2024). Creativity and resilience: Creativity from, or through adversity? Creativity Research Journal, 37(2), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2023.2299639 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fu, D., Liu, Y., & Zhang, D. (2023). The relationship between teacher autonomy support and student mathematics achievement: A 3-year longitudinal study. Educational Psychology, 43(2–3), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2023.2190064 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gutiérrez, M., & Tomás, J. M. (2019). The role of perceived autonomy support in predicting university students’ academic success mediated by academic self-efficacy and school engagement. Educational Psychology, 39(6), 729–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2023.2299639 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hardre, P. L., & Reeve, J. (2003). A motivational model of rural students’ intentions to persist in, versus drop out of, high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(2), 347. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.347 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis (3rd ed.Chicago, IL, USA: U Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

Hennessey, B. A., Amabile, T. M. (1987). Creativity and learning: What research says to the teacher. West Haven, CT, USA: National Education Association, Professional Library. [Google Scholar]

Heo, H., Bonk, C. J., & Doo, M. Y. (2021). Enhancing learning engagement during COVID-19 pandemic: Self-efficacy in time management, technology use, and online learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(6), 1640–1652. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12603 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jang, H., Kim, E. J., & Reeve, J. (2012). Longitudinal test of self-determination theory’s motivation mediation model in a naturally occurring classroom context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1175. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028089 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(3), 588. https://doi.org/10.23887/jet.v6i2.44417 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lai, Y.-C., & Wu, P.-H. (2019). The effects of students’ perceived teachers’ autonomy support, teachers’ psychological control, self-determination motivation, academic emotions on learning engagement of elementary school students: Taking math as example. Journal of Education & Psychology, 42(4), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.3966/102498852019124204002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lawman, H. G., Wilson, D. (2013). Self-determination theory. In: M. D. Gellman, J. R. Turner (Eds.Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine (pp. 1735–1737New York, NY, USA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, Y., Gao, J., Guo, L., Lu, Y., & Li, Y. (2025). How teacher autonomy support and emotional violence shape adolescent achievement emotions: The mediating effect of teacher-student relatedness. Journal of Adolescence, 1(3), 15. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.70033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., & Pekrun, R. (2011). Students’ emotions and academic engagement: Introduction to the special issue. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.11.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Miao, J., & Ma, L. (2023). Teacher autonomy support influence on online learning engagement: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and self-regulated learning. SAGE Open, 13(4), 21582440231217737. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231217737 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Miller, A. L., & Dumford, A. D. (2016). Creative cognitive processes in higher education. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 50(4), 282–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.77 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mostafavi, H., Yoosefee, S., Seyyedi, S. A., Rahimi, M., & Heidari, M. (2020). The impact of educational motivation and self-acceptance on creativity among high school students. Creativity Research Journal, 32(4), 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2020.1821561 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nelson, N., Malkoc, S. A., & Shiv, B. (2018). Emotions know best: The advantage of emotional versus cognitive responses to failure. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 31(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2042 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Orakci, Ş., & Durnali, M. (2023). The mediating effects of metacognition and creative thinking on the relationship between teachers’ autonomy support and teachers’ self-efficacy. Psychology in the Schools, 60(1), 162–181. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22770 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Oriol-Granado, X., Mendoza-Lira, M., Covarrubias-Apablaza, C.-G., & Molina-López, V.-M. (2017). Positive emotions, autonomy support and academic performance of university students: The mediating role of academic engagement and self-efficacy. Revista De Psicodidáctica (English Ed.), 22(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1387/RevPsicodidact.14280 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Patrick, B. C., Skinner, E. A., & Connell, J. P. (1993). What motivates children’s behavior and emotion? Joint effects of perceived control and autonomy in the academic domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 781. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Patzak, A., & Zhang, X. (2025). Blending teacher autonomy support and provision of structure in the classroom for optimal motivation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 37(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-025-09994-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., & Perry, R. P. (2007). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: An integrative approach to emotions in education. In: Emotion in education (pp. 13–36Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3702_4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pekrun, R., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). Academic emotions and student engagement. In: Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 259–282Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Printer, L. (2023). Positive emotions and intrinsic motivation: A self-determination theory perspective on using co-created stories in the language acquisition classroom. Language Teaching Research, 23, 269. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688231204443 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Reeve, J., & Cheon, S. H. (2024). Learning how to become an autonomy-supportive teacher begins with perspective taking: A randomized control trial and model test. Teaching and Teacher Education, 148(1), 104702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2024.104702 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Reeve, J., Cheon, S. H., & Yu, T. H. (2020). An autonomy-supportive intervention to develop students’ resilience by boosting agentic engagement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(4), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025420911103 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Richardson, C., & Mishra, P. (2018). Learning environments that support student creativity: Developing the SCALE. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 27(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2017.11.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Roeser, R. W., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. C. (1996). Perceptions of the school psychological environment and early adolescents’ psychological and behavioral functioning in school: The mediating role of goals and belonging. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 408. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.88.3.408 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2012.650092 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Runco, M. A., & Johnson, D. J. (2002). Parents’ and teachers’ implicit theories of children’s creativity: A cross-cultural perspective. Creativity Research Journal, 14(3–4), 427–438. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326934CRJ1434_12 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ryan, R. M., Deci, E. L. (2004). Autonomy is no illusion: Self-determination theory and the empirical study of authenticity, awareness, and will. In: J. Greenberg, S. L. Koole, T. Pyszczynski (Eds.Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 449–479New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Sadoughi, M., & Hejazi, S. Y. (2021). Teacher support and academic engagement among EFL learners: The role of positive academic emotions. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70(1), 101060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101060 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Salmanpour, O., Tabatabaei, O., Salehi, H., & Yunus, M. M. (2024). Impact of the online Stoodle software program on Iranian EFL teachers’ autonomy, creativity, and work engagement. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 9(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-023-00227-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sawyer, R. K., Henriksen, D. (2023). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197747537.001.0001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schreiner, L. A., & Louis, M. C. (2011). The engaged learning index: implications for faculty development. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 22, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

Shen, H., Ye, X., Zhang, J., & Huang, D. (2024). Investigating the role of perceived emotional support in predicting learners’ well-being and engagement mediated by motivation from a self-determination theory framework. Learning and Motivation, 86(20), 101968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2024.101968 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shu, Y., Ho, S.-J., & Huang, T.-C. (2020). The development of a sustainability-oriented creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship education framework: A perspective study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1878. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Soh, K. (2017). Fostering student creativity through teacher behaviors. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 23(3), 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.11.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tegeh, I. M., Santyasa, I. W., Agustini, K., Santyadiputra, G. S., & Juniantari, M. (2022). Group investigation flipped learning in achieving of students’ critical and creative thinking viewed from their cognitive engagement in learning physics. Journal of Education Technology, 6(2), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.23887/jet.v6i2.44417 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Vermeulen, M., Kreijns, K., & Evers, A. T. (2022). Transformational leadership, leader-member exchange and school learning climate: Impact on teachers’ innovative behaviour in the Netherlands. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(3), 491–510. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143220932582 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, J., Liu, R.-D., Ding, Y., Xu, L., Liu, Y., et al. (2017). Teacher’s autonomy support and engagement in math: Multiple mediating roles of self-efficacy, intrinsic value, and boredom. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 767. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yang, D., Chen, P., Wang, H., Wang, K., & Huang, R. (2022). Teachers’ autonomy support and student engagement: A systematic literature review of longitudinal studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 925955. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.925955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yuan, Y. H., Wu, M. H., Hu, M. L., & Lin, I. C. (2019). Teacher’s encouragement on creativity, intrinsic motivation, and creativity: The mediating role of creative process engagement. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 53(3), 312–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.181 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools