Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Perfectionism and writing performance: Self-efficacy and motivation mediation

Faculty of Modern Languages and Communication, Department of English, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, 43400, Selangor, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Ye Tao. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 671-679. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.066530

Received 10 April 2025; Accepted 04 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the role of self-efficacy and motivation in the relationship between perfectionism and writing performance. Participants were 500 Chinese EFL (English as a Foreign Language) undergraduates (females = 34%, Mage = 21.56 years, SD = 2.27). The students completed the Self-Reported Writing Proficiency Scale, the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale for Chinese, the Second Language Writer Self-Efficacy Scale, and the English Writing Motivation Questionnaire. Results from Structural Equation Modeling (SEM, Amos 29.0) revealed that perfectionism predicted writing performance positively for students with positive (adaptive) perfectionism, but negatively for those with negative (maladaptive) perfectionism. Self-efficacy and motivation mediated these relationships, strengthening the link between perfectionism and writing performance. Specifically, positive perfectionism significantly enhanced writing ability by increasing self-efficacy and motivation, whereas negative perfectionism significantly reduced self-efficacy and motivation, thereby inhibiting writing performance. These findings are consistent with the Dual-Process Model of Perfectionism, which posits that perfectionism can function through both positive and negative pathways. The model highlights that students with positive perfectionism exhibit higher levels of self-efficacy and motivation, whereas those with negative perfectionism demonstrate the opposite pattern.Keywords

Perfectionism, is the pursuit of excessively high standards, and can be either adaptive or maladaptive (Fang & Liu, 2022; Goulet-Pelletier et al., 2022; Samfira & Palos, 2021; Song et al., 2023). Among students, perfectionism can influence their orientations toward writing performance. Writing is inherently complex, shaped by a constellation of factors including cognitive strategies, affective states, cultural contexts, and psychological dispositions. (Tao & Yu, 2024). In today’s interconnected and globalized world, proficient English writing has become a critical skill for achieving academic excellence and advancing professional careers (Hossain, 2024). When students write in a second/foreign language, the pressure associated with perfectionism may be heightened. Much depends on student’s self-efficacy and motivation. However, to our knowledge, no study has specifically examined the relationship between perfectionism and writing performance among second/foreign language learners while also considering the roles of self-efficacy and motivation. The present study aims to address this gap by investigating these factors among Chinese EFL undergraduates.

Perfectionism and writing performance

Second/foreign language writing requires a wide range of cognitive, linguistic, and metacognitive abilities, including grammatical knowledge, vocabulary control, genre awareness, and the capacity to plan, monitor, and revise texts (Al-Othman & Abdul-Aziz, 2024; Xu & Zhu, 2025). Successful writers must integrate these skills while managing the additional cognitive load of composing in a non-native language. Research has demonstrated that proficiency in these areas directly influences writing performance (Teng & Zhang, 2024), especially under the pressure of academic or high-stakes tasks. Furthermore, affective factors interact with cognitive demands, further influencing writing outcomes.

In the domain of second/foreign language writing, perfectionism has been shown to exert a dual impact (Lin, 2020). On the one hand, positive perfectionism can motivate learners to pursue linguistic precision and structural coherence, thereby improving the overall quality of their writing (Naz et al., 2021). On the other hand, negative perfectionism is often associated with anxiety, procrastination, and avoidance behaviors. Such tendencies heighten the fear of making mistakes, contribute to writing paralysis, and often result in weaker academic performance (Lee et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022; Lin & Muenks, 2022; Noor, 2023). Although perfectionism may promote self-discipline, it can simultaneously undermine writing performance by fostering excessive self-criticism and diminishing confidence, especially when students encounter failure or critical feedback (Mo et al., 2022).

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their capacity to perform tasks and achieve desired outcomes (Koutroubas & Galanakis, 2022). In the context of writing, self-efficacy influences not only the quantity and quality of students’ output but also their resilience when encountering challenges (Shkëmbi & Treska, 2023). High levels of writing self-efficacy promote persistence, strategic planning, and active engagement, enabling learners to overcome linguistic and structural difficulties. Conversely, low self-efficacy is often associated with avoidance behaviors, reduced effort, and negative writing experiences, all of which hinder writing development (Huang et al., 2024; Radjuni et al., 2024). Therefore, writing self-efficacy functions as a protective factor, fostering resilience and supporting long-term improvement in writing competence (Irie, 2021; Teng & Wang, 2023).

Closely related to self-efficacy is the concept of motivation—a key psychological driver of writing engagement and achievement. Motivation can be defined as the internal drive or external incentive to act, determining the effort, persistence, and focus individuals devote to achieving a goal (Medalia & Saperstein, 2011). In the writing context, task-specific motivation encourages learners to invest time and energy in improving their writing skills. For Chinese learners in particular, motivation is shaped by a complex interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic motivation stems from genuine interest and personal satisfaction, whereas extrinsic motivation is driven by rewards such as academic grades, career opportunities, or social recognition (Hu, 2022). Both forms of motivation enhance writing effort, though their sustainability and quality may vary depending on the source.

The influence of self-efficacy and motivation on the relationship between perfectionism and writing performance must be understood within a cultural framework. We therefore briefly consider the Chinese educational context as background.

For Chinese learners, English writing has become more than a tool for communication; it now represents a gateway to educational resources, international engagement, and professional advancement (Guo et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2021; Jo, 2021; Zhang & Zhang, 2022). Within Chinese higher education, strong English writing proficiency is regarded not only as a reflection of linguistic competence but also as evidence of higher-order cognitive abilities such as logical reasoning, critical thinking, and adherence to academic conventions. Consequently, English writing performance plays a pivotal role in students’ academic achievement and recognition on international platforms.

Rooted in Confucian traditions, Chinese students are often characterized as diligent, achievement-oriented, and sensitive to failure (Liang & Matthews, 2023; Muyunda & Yue, 2022). This cultural emphasis on academic excellence and face-saving may foster adaptive forms of perfectionism but can also amplify maladaptive tendencies when external expectations from family, peers, and society are internalized (Jun et al., 2022; Song & Ren, 2022). Furthermore, the legacy of exam-driven, teacher-centered education often emphasizes rote memorization over creativity and self-expression. Such practices may suppress intrinsic motivation and weaken self-efficacy (Wu, 2021), leading students to perceive writing success as externally defined and difficult to attain. This, in turn, increases their susceptibility to performance anxiety and self-doubt.

In summary, the relationships among perfectionism, self-efficacy, and motivation form a critical foundation for understanding the psychological dynamics that influence writing performance. Although prior research has examined the individual effects of these variables on academic performance and language learning (Liu et al., 2024; Wan et al., 2023), significant gaps remain, particularly in relation to English as a Foreign Language (EFL) writing among Chinese learners.

The present study aims to investigate the relationship between perfectionism and writing performance, with a particular focus on whether self-efficacy and motivation mediate this relationship. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed (see Figure 1 for hypothesized model).

Figure 1: Hypothesized model of the study

H1: Positive perfectionism is significantly positively associated with English writing performance, whereas negative perfectionism is significantly negatively associated with English writing performance.

H2: Both self-efficacy and motivation singularly mediate the relationship between perfectionism (positive and negative) and writing performance.

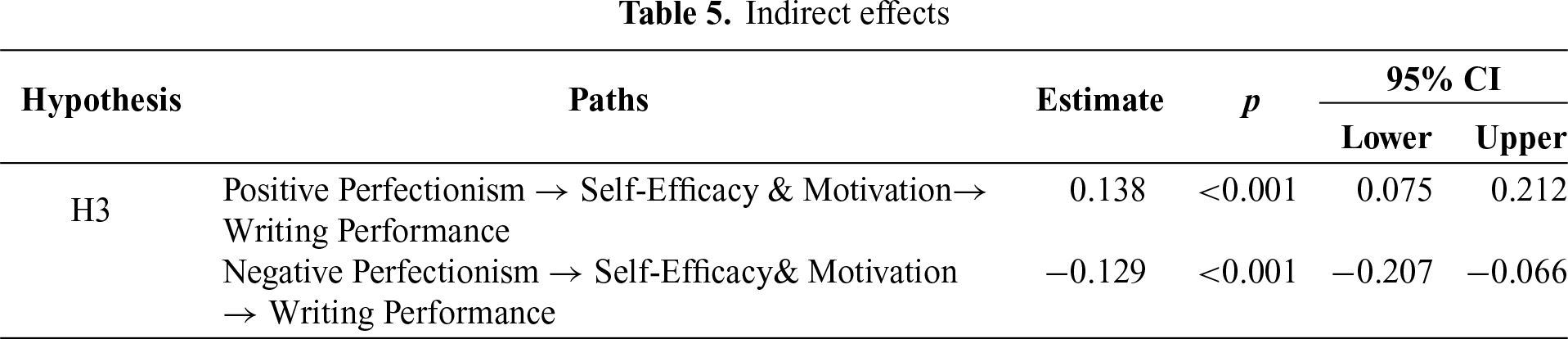

H3: The joint mediating effects of self-efficacy and motivation significantly influence the relationship between perfectionism (positive and negative) and writing performance.

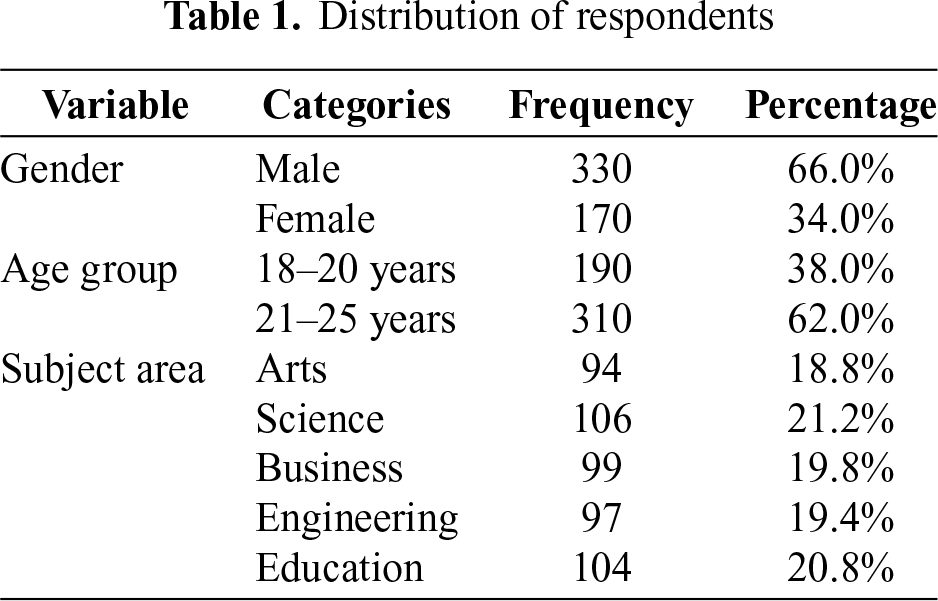

The participants of this study consisted of 500 university students recruited from three provinces in China: Anhui, Jiangxi, and Yunnan (females = 34%, Mage = 21.56 years, SD = 2.27). They represented a range of disciplines, including engineering, business, education, the arts, and the sciences, and all were EFL learners. The age distribution indicated that the majority of participants (62%) were between 21 and 25 years old, reflecting a typical undergraduate population (see Table 1 for demographics).

The participants completed validated instruments assessing Writing Performance (WP; Tao & Yu, 2024), Perfectionism (PERF; Zi & Zhou, 2006), Self-Efficacy (SE; Teng et al., 2018), and Writing Motivation (MOT; Luo, 2020). All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The Self-Reported Writing Proficiency Scale (Tao & Yu, 2024) was employed to assess participants’ overall writing performance. This unidimensional instrument comprises five items (e.g., “I can express my thoughts clearly in written English”). In the present study, the scale demonstrated acceptable internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79.

This study employed the 27-item Chinese version of the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Zi & Zhou, 2006), covering five core dimensions: concern over mistakes (CM; 6 items; e.g., “If I can’t do as well as others, it means I am an inferior person”), doubts about actions (DA; 4 items; e.g., “Even when I do things carefully, I often feel that I haven’t done them quite right”), parental expectations (PE; 5 items; e.g., “My parents set very high standards for me”), personal standards (PS; 6 items; e.g., “I expect myself to achieve more in my daily work or study than most people do”), and organization (OR; 6 items; e.g., “It is very important to me to be organized and systematic”). Based on Zi and Zhou (2006), CM, DA, and PE were categorized as indicators of negative perfectionism, whereas PS and OR were categorized as indicators of positive perfectionism. In the present study, the scale demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency across all dimensions, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.904 for PS, 0.906 for OR, 0.896 for CM, 0.842 for DA, and 0.880 for PE.

The Second Language Writer Self-Efficacy Scale (Teng et al., 2018) comprises 20 items on three core dimensions: linguistic self-efficacy (LSE; 7 items), which pertains to confidence in using language accurately and fluently efficacy (e.g., “I can write compound and complex sentences with grammatical structure”); self-regulatory efficacy (SRSE; 6 items), which reflects the ability to plan, monitor, and revise one’s writing effectively (e.g., “I can think of different ways to help me to plan before writing”); and performance self-efficacy (PSE; 7 items), which captures the perceived capacity to meet academic standards and audience expectations (e.g., “I can master the writing knowledge and strategies being taught in writing courses”). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the LSE, SRSE, and PSE were 0.910, 0.899, and 0.916, respectively.

The English Writing Motivation Questionnaire used in this study was adapted from Gardner’s Attitude/Motivation Test Battery (AMTB). The measure comprises 22 items to assess motivation related to writing tasks in two dimensions: intrinsic motivation (IN; 12 items), which reflects learners’ internal interest in and enjoyment of writing (e.g., “I am very interested in English writing”), and extrinsic motivation (EM; 10 items), which captures motivation driven by external rewards or pressures, such as academic grades, parental expectations, or anticipated career benefits (e.g., “I practice English writing to improve my writing scores and achieve high marks in exams”). In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.946 for IN and 0.935 for EM, indicating excellent reliability.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universiti Putra Malaysia (JKEUPM-2024-437). All participants provided informed consent and were assured of voluntary participation and data confidentiality. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the institution’s ethical standards and were by the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses were conducted using SPSS 29.0. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed via AMOS 29.0 to test the hypothesized mediation model, in which self-efficacy and motivation served as mediating variables. Path coefficients were estimated using bootstrap resampling with 5000 iterations, and 95% confidence intervals were applied to examine the significance of the mediating effects.

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors employed GPT-4 (OpenAI) as a language-support tool. The AI was used exclusively for language polishing and improving clarity of expression. No AI tool was used for data analysis, result interpretation, or drawing conclusions. All outputs from the tool were critically reviewed, edited, and verified by the authors to ensure accuracy and appropriateness.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

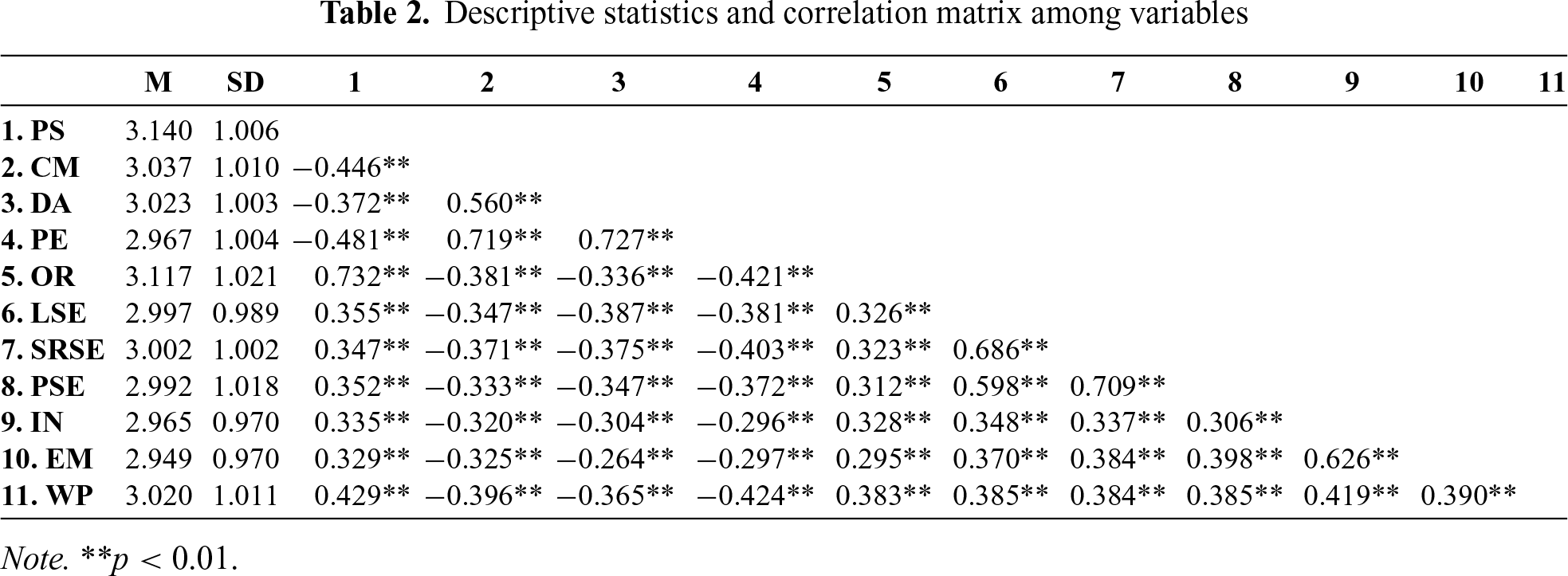

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the primary variables of the study. The results reveal statistically significant correlations among all dimensions of positive perfectionism, negative perfectionism, writing self-efficacy, writing motivation, and English writing performance.

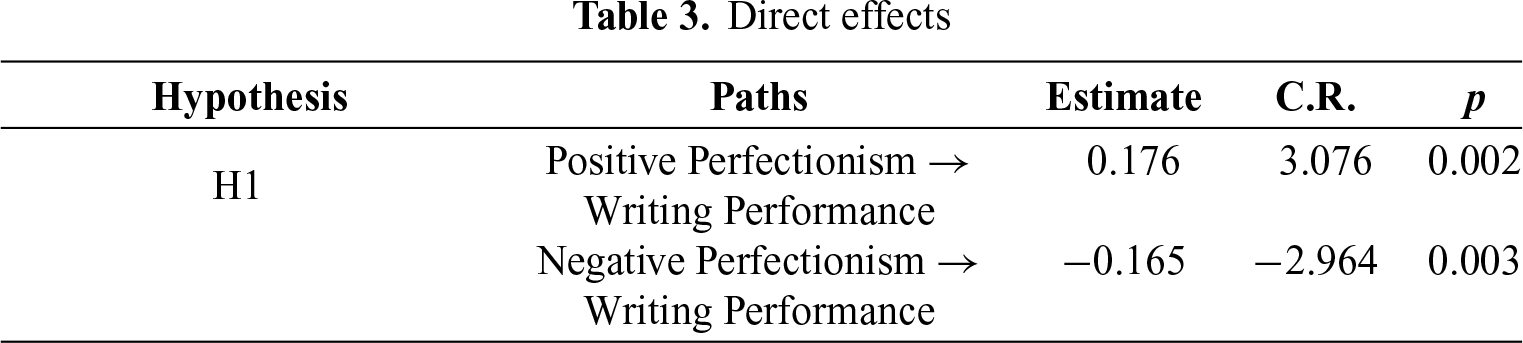

Direct effects of perfectionism on English writing performance

Prior to testing the indirect model, this study examined the direct effects of perfectionism on English writing performance. As shown in Table 3, the structural equation modeling results revealed that positive perfectionism exerted a significant positive effect on writing performance (β = 0.176, p = 0.002), while negative perfectionism had a significant negative effect on writing performance (β = −0.165, p = 0.003), thereby supporting Hypothesis 1.

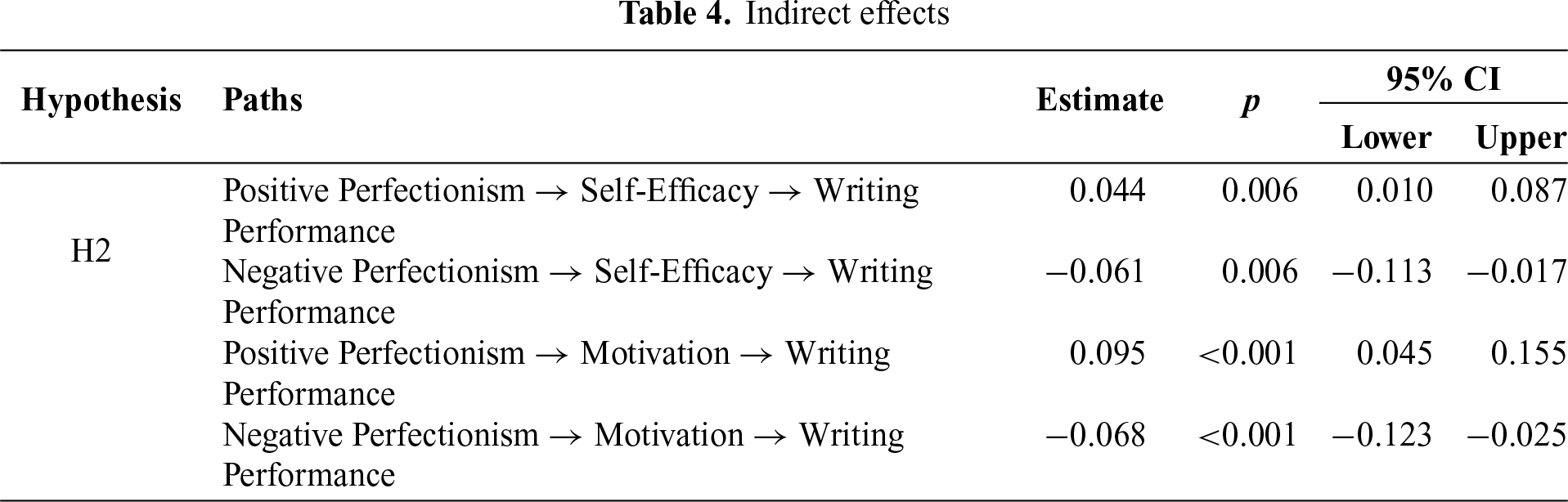

Self-efficacy and motivation mediation

A mediation model was constructed with perfectionism (positive and negative) as the independent variable, self-efficacy and motivation as mediators, and English writing performance as the dependent variable. Standardized coefficients for the structural paths are presented in Figure 2. The model demonstrated a good fit to the data: CMIN/DF = 2.389, NFI = 0.969, IFI = 0.982, CFI = 0.981, TLI = 0.972, RMSEA = 0.053, RMR = 0.055.

Figure 2: Path coefficients of the hypothesized model

As shown in Table 4, the indirect effect analysis demonstrated that self-efficacy significantly mediated the relationship between both positive and negative perfectionism and writing performance. Specifically, positive perfectionism exerted a significant positive indirect effect on writing performance through self-efficacy (β = 0.044, p = 0.006, 95% CI [0.010, 0.087]). In contrast, negative perfectionism exerted a significant negative indirect effect through self-efficacy (β = −0.061, p = 0.006, 95% CI [−0.113, −0.017]).

Furthermore, motivation significantly mediated the effects of perfectionism on writing performance. Positive perfectionism was positively associated with writing performance through increased motivation (β = 0.095, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.045, 0.155]), whereas negative perfectionism was negatively associated with writing performance through reduced motivation (β = −0.068, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.123, −0.025]). These results support Hypothesis 2, indicating that both self-efficacy and motivation singularly mediate the relationship between perfectionism (positive and negative) and writing performance.

The joint mediating effects of self-efficacy and motivation

In addition to demonstrating that self-efficacy and motivation singularly mediate the relationship between perfectionism (positive and negative) and writing performance, this study also constructed a composite mediation model that incorporates both self-efficacy and motivation.

As presented in Table 5, the results demonstrated that positive perfectionism exerted a significant positive effect on writing performance through the joint mediation of self-efficacy and motivation (β = 0.138, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.075, 0.212]). Conversely, negative perfectionism exerted a significant negative effect on writing performance through the joint mediation of self-efficacy and motivation (β = −0.129, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.207, −0.066]). These results provide strong support for Hypothesis 3.

The results of this study reveal significant direct effects of both positive and negative perfectionism on the writing performance of EFL learners. Specifically, positive perfectionism was found to be a significant positive predictor of writing performance, while negative perfectionism exerted a detrimental effect. These findings align with the Dual-Process Model of Perfectionism proposed by Slade and Owens (1998), which distinguishes between positive and negative perfectionism. Although both types of perfectionism may produce similar outward behaviors, their underlying motivations, emotional states, and cognitive processes differ substantially. Positive perfectionism is associated with adaptive behaviors such as persistence and constructive goal pursuit, while negative perfectionism is linked to maladaptive tendencies including anxiety and avoidance. Consistent with previous studies (Gunyakti Akdeniz et al., 2024; Osenk et al., 2020; Stoeber & Otto, 2006), the current findings highlight the multidimensional nature of perfectionism: positive perfectionism fosters higher goal pursuit and greater effort investment, whereas negative perfectionism is more likely to result in procrastination, heightened anxiety, and writing burnout. This indicates that positive perfectionism can serve as a motivational resource that promotes students’ persistence and goal attainment, thereby increasing the likelihood of superior performance in writing tasks. In contrast, individuals with negative perfectionism may experience performance deficits during writing tasks (Chen et al., 2022; Flett & Hewitt, 2002; Jia et al., 2025; Rezaei-Gazki et al., 2024).

A further contribution of this study is the identification of self-efficacy as a mediator between perfectionism and writing performance. This result supports Bandura’s (1986) Social Cognitive Theory, which emphasizes the pivotal role of self-efficacy in shaping individuals’ behavioral outcomes. Students with higher self-efficacy demonstrated greater confidence in their ability to complete writing tasks and achieve academic standards, which is consistent with findings from previous studies in EFL contexts (Kong & Teng, 2023; Teng, 2024; Teng & Teng, 2024). Learners with positive perfectionism tended to exhibit high self-efficacy, enabling them to regulate emotions, persist through difficulties, and ultimately perform better in writing tasks (Bandura, 1997; Kozłowska & Kuty-Pachecka, 2022). Conversely, students characterized by negative perfectionism were more prone to excessive self-criticism and fear of failure, which weakened self-efficacy and produced self-doubt, anxiety, and disengagement (Madigan, 2019).

The findings also demonstrate that motivation serves as a mediator in the relationship between perfectionism and writing performance. The results indicate that positive perfectionism was associated with higher levels of intrinsic motivation, which, in turn, enhanced writing performance. This finding is consistent with Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), which suggests that individuals who engage in writing out of personal interest or a desire for self-growth tend to produce creative and higher-quality work. Conversely, negative perfectionism was more likely to be driven by extrinsic motivation, such as fear of failure and external evaluation pressure. Although such motivation may drive short-term engagement, it is unsustainable and more likely to result in burnout, anxiety, and poorer writing outcomes over time (Ma, 2024).

Importantly, this study underscores the joint mediating roles of self-efficacy and motivation in the relationship between perfectionism and writing performance. The identification of a joint mediating pathway underscores the importance of addressing both belief systems and motivational states when seeking to support student writers. These results indicate that positive perfectionism strengthens belief in one’s writing ability and sustains motivation, thereby enhancing writing outcomes. In contrast, negative perfectionism undermines students’ belief in their potential for success and diminishes their desire to strive, ultimately leading to writing burnout, reduced engagement, or poor performance. These results reinforce previous evidence emphasizing the importance of self-efficacy and motivation in shaping writing performance (Sakinah et al., 2025; Zhang, 2024).

This study is theoretically significant because it highlights the mediating effects of self-efficacy and motivation in the relationship between perfectionism and writing performance. It emphasizes the importance of viewing writing competence as a multi-dimensional construct and demonstrates how it is influenced by psychological and contextual factors. The findings provide deeper insight into the processes involved in writing achievements in EFL contexts.

This study supports the hypothesized relationships among perfectionism, self-efficacy, motivation, and writing performance, while also uncovering the underlying mediation mechanisms. The findings highlight that writing performance is influenced by perfectionism both directly and indirectly through self-efficacy and motivation, thereby advancing our understanding of cognitive and motivational factors in writing research.

From a pedagogical perspective, students with higher levels of self-efficacy and motivation are more likely to transform their perfectionist tendencies into improved writing performance. Thus, a key priority should be to develop a supportive learning environment that enhances student engagement and self-efficacy, ultimately promoting writing success.

Classroom-based interventions should primarily aim at enhancing students’ self-efficacy through constructive feedback and opportunities for mastery experiences. In addition, the application of motivational strategies, such as focusing on task relevance and goal-setting, can sustain students’ interest in writing, both intrinsically and extrinsically (Mikami, 2017). At the policy level, curriculum designers are suggested to consider advancing the integration of psychological and motivational support into English writing programs (Rahimi, 2024).

Limitations and future directions

Despite the valuable contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the usage of self-reported measures may have introduced response bias, as participants tended to over- or under-report their abilities. Future studies should incorporate objective assessments, such as performance-based tasks or teacher evaluations, to validate self-reported data. Second, the cross-sectional design restricts causal interpretations. Longitudinal research is recommended to explore how these relationships develop over time. Third, the exclusive focus on Chinese undergraduate students limits the generalizability of the findings. Comparative studies across diverse cultural and educational contexts are needed to examine the interaction between perfectionism and writing performance. Finally, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of writing success, future research should explore additional psychological factors, such as resilience, stress management, and metacognitive writing strategies.

This study provides evidence that both positive and negative facets of perfectionism influence writing performance. Self-efficacy and motivation were found to mediate the relationship between perfectionism and writing performance in the EFL context. These findings highlight the importance of encouraging positive perfectionist behaviors while mitigating the detrimental effects of negative perfectionism. The practical implication for educators and policymakers includes the need for targeted support that balances the pursuit of academic excellence with the promotion of students’ emotional well-being. Student counselling and academic development services for improved writing performance should focus on strengthening learners’ self-efficacy and fostering both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to enhance writing success. In summary, this study not only confirms the direct role of self-efficacy in enhancing writing performance but also highlights its mediating role in transforming perfectionist tendencies into constructive outcomes.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to their teachers and fellow classmates for their invaluable support and assistance in this study. Moreover, during the preparation of this manuscript, the authors utilized GPT-4 (OpenAI) for language editing and clarity improvements. The authors have carefully reviewed and revised the output and accept full responsibility for all content.

Funding Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, writing—original draft preparation: Ye Tao; analysis, writing—review and editing: Ilyana Jalaluddin; supervision, project administration: Zalina Mohd Kasim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Ye Tao, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universiti Putra Malaysia (JKEUPM-2024-437). All participants provided informed consent and were assured of voluntary participation and data confidentiality. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were following the institution’s ethical standards and were by the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Al-Othman, M., & Abdul-Aziz, A. (2024). EFL students develop cognitive and metacognitive self-regulated writing strategies using automated feedback: A case study. Theory & Practice in Language Studies (TPLS), 14(5), 1525. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1405.26 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY, USA: W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

Chen, W. W., Yang, X., & Jiao, Z. (2022). Authoritarian parenting, perfectionism, and academic procrastination. Educational Psychology, 42(9), 1145–1159. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2021.2024513 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fang, T., & Liu, F. (2022). A review on perfectionism. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 10(1), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2022.101027 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2002). Perfectionism and maladjustment: An overview of theoretical, definitional, and treatment issues. In: Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 5–31). Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Goulet-Pelletier, J. C., Gaudreau, P., & Cousineau, D. (2022). Is perfectionism a killer of creative thinking? A test of the model of excellencism and perfectionism. British Journal of Psychology, 113(1), 176–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gunyakti Akdeniz, H., Bayhan Karapinar, P., Metin Camgoz, S., & Tayfur Ekmekci, O. (2024). Seeking the balance in perceived task performance: The interaction of perfectionism and perceived organizational support. Current Psychology, 43(16), 14712–14724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05473-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guo, Y., Guo, S., Yochim, L., & Liu, X. (2022). Internationalization of Chinese higher education: Is it westernization? Journal of Studies in International Education, 26(4), 436–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315321990745 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hossain, K. I. (2024). Reviewing the role of culture in English language learning: Challenges and opportunities for educators. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 9, 100781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2023.100781 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hu, N. (2022). Investigating Chinese EFL learners’ writing strategies and emotional aspects. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network, 15(1), 440–468. [Google Scholar]

Hu, X., Subramaniam, I., & Li, Q. (2021). The current situation of English writing teaching in China under the background of internet. In: 2021 International Conference on Internet, Education and Information Technology (IEITNew York, NY, USA: IEEE, 367–370. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEIT53597.2021.00087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, F., Wang, Y., & Zhang, H. (2024). Modelling generative AI acceptance, perceived teachers’ enthusiasm and self-efficacy to English as a foreign language learners’ well-being in the digital era. European Journal of Education, 59(4), e12770. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12770 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Irie, K. (2021). Self-efficacy. In: S. Mercer, S. Ryan (Eds.The routledge handbook of the psychology of language learning and teaching (pp. 100–111). New York, NY, USA: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429321498 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jia, Y., Yue, S., Fang, M., & Wang, X. (2025). Bridging perfectionism and innovation—a moderated-mediation model based on achievement goal theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1468489. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1468489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jo, C. W. (2021). Exploring general versus academic English proficiency as predictors of adolescent EFL essay writing. Written Communication, 38(2), 208–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088320986364 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jun, H. H., Wang, K. T., Suh, H. N., & Yeung, J. G. (2022). Family profiles of maladaptive perfectionists among Asian international students. The Counseling Psychologist, 50(5), 649–673. https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000221089643 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kong, A., & Teng, M. F. (2023). The operating mechanisms of self-efficacy and peer feedback: An exploration of L2 young writers. Applied Linguistics Review, 14(2), 297–328. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2020-0019 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Koutroubas, V., & Galanakis, M. (2022). Bandura’s social learning theory and its importance in the organizational psychology context. Psychology, 12(6), 315–322. https://doi.org/10.17265/2159-5542/2022.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kozłowska, M. A., & Kuty-Pachecka, M. (2022). When perfectionists adopt health behaviors: Perfectionism and self-efficacy as determinants of health behavior, anxiety and depression. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 11(4), 326. https://doi.org/10.5114/cipp/156145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lee, A. R. X. E., Ishak, Z., Talib, M. A., Ho, Y. M., Prihadi, K. D., et al. (2024). Fear of failure among perfectionist students. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE), 13, 643–651. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v13i2.26296 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liang, Y., & Matthews, K. E. (2023). Are confucian educational values a barrier to engaging students as partners in Chinese universities? Higher Education Research & Development, 42(6), 1453–1466. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2138276 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, L. (2020). Perfectionism and writing performance of Chinese EFL college learners. English Language Teaching, 13(8), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n8p35 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, S., & Muenks, K. (2022). Perfectionism profiles among college students: A person-centered approach to motivation, behavior, and emotion. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 71, 102110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2022.102110 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, S., He, L., Wei, M., Du, Y., & Cheng, D. (2022). Depression and anxiety from acculturative stress: Maladaptive perfectionism as a mediator and mindfulness as a moderator. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 207. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000242 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, W., Zhang, R., Wang, H., Rule, A., Wang, M., et al. (2024). Association between anxiety, depression symptoms, and academic burnout among Chinese students: The mediating role of resilience and self-efficacy. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 335. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01823-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Luo, Y. (2020). Investigating influences of English writing motivation and writing strategyon the English writing performance of non-English major college students [Master’sthesis]. Nanchang, China: Jiangxi Normal University. [Google Scholar]

Ma, Y. (2024). The impact of academic self-efficacy and academic motivation on Chinese EFL students’ academic burnout. Learning and Motivation, 85, 101959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2024.101959 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Madigan, D. J. (2019). A meta-analysis of perfectionism and academic achievement. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 967–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09484-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Medalia, A., & Saperstein, A. (2011). The role of motivation for treatment success. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(suppl_2), S122–S128. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbr063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mikami, Y. (2017). Relationships between goal setting, intrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy in extensive reading. Jacet Journal, 61, 41–56. https://doi.org/10.32234/jacetjournal.61.0_41 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mo, C. Y., Jin, J., & Jin, P. (2022). Relationship between teachers’ teaching modes and students’ temperament and learning motivation in Confucian culture during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 865445. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.865445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Muyunda, G., & Yue, L. (2022). Confucius’ education thoughts and its influence on moral education in China. International Journal of Social Learning (IJSL), 2(2), 250–261. https://doi.org/10.47134/ijsl.v2i2.141 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Naz, S., Hassan, G., & Luqman, M. (2021). Influence of perfectionism and academic motivation on academic procrastination among students. Journal of Educational Sciences & Research, 8(1), 13. [Google Scholar]

Noor, B. (2023). Pressure and perfectionism: A phenomenological study on parents’ and teachers’ perceptions of the challenges faced by gifted and talented students in self-contained classes. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1225623. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1225623 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Osenk, I., Williamson, P., & Wade, T. D. (2020). Does perfectionism or pursuit of excellence contribute to successful learning? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Assessment, 32(10), 972. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Radjuni, M., Sahraeny, S., & Latief, M. R. A. (2024). The relationship between self-efficacy and EFL students’ speaking performance: A case study of english department students. SHIELD: Journal of Studies on Human Interaction, Education, and Language Development, 1(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

Rahimi, M. (2024). Effects of integrating motivational instructional strategies into a process-genre writing instructional approach on students’ engagement and argumentative writing. System, 121, 103261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103261 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rezaei-Gazki, P., Ilaghi, M., & Masoumian, N. (2024). The triangle of anxiety, perfectionism, and academic procrastination: Exploring the correlates in medical and dental students. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05145-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sakinah, R., Dewi, R., & Nappu, S. (2025). The relationship between students’ motivation, self-efficacy, and their writing achievement. IDEAS: Journal on English Language Teaching and Learning, Linguistics and Literature, 13(1), 2962–2978. https://doi.org/10.24256/ideas.v13i1.5687 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Samfira, E. M., & Paloş, R. (2021). Teachers’ personality, perfectionism, and self-efficacy as predictors for coping strategies based on personal resources. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 751930. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.751930. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Shkëmbi, F., & Treska, V. (2023). A review of the link beetween self-efficacy, motivation and academic performance in students. European Journal of Social Science Education and Research, 10(1s), 23–31. [Google Scholar]

Slade, P. D., & Owens, R. G. (1998). A dual process model of perfectionism based on reinforcement theory. Behavior Modification, 22(3), 372–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/01454455980223010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Song, A., & Ren, Z. (2022). Distressing experiences of Chinese schooling winners: School infiltration in Chinese family parenting. Cogent Education, 9(1), 2034245. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186x.2022.2034245 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Song, T., Wang, W., Chen, S., Li, W., & Li, Y. (2023). Examining the effects of positive and negative perfectionism and maternal burnout. Personality and Individual Differences, 208, 112192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112192 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tao, Y., & Yu, J. (2024). Cultural threads in writing mastery: A structural analysis of perfectionism, learning self-efficacy, and motivation as mediated by self-reflection in Chinese EFL learners. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01572-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Teng, L. S. (2024). Individual differences in self-regulated learning: Exploring the nexus of motivational beliefs, self-efficacy, and SRL strategies in EFL writing. Language Teaching Research, 28(2), 366–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211006881 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Teng, L. S., Sun, P. P., & Xu, L. (2018). Conceptualizing writing self-efficacy in English as a foreign language context: Scale validation through structural equation modeling. Tesol Quarterly, 52(4), 911–942. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.432 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Teng, M. F., & Teng, L. S. (2024). Validating the multi-dimensional structure of self-efficacy beliefs in peer feedback for L2 writing: A bifactor-exploratory structural equation modeling approach. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 3(3), 100136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmal.2024.100136 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Teng, M. F., & Wang, C. (2023). Assessing academic writing self-efficacy belief and writing performance in a foreign language context. Foreign Language Annals, 56(1), 144–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12638 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Teng, M. F., & Zhang, L. J. (2024). Assessing self-regulated writing strategies, working memory, L2 proficiency level, and multimedia writing performance. Language Awareness, 33(3), 570–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2023.2300269 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wan, X., Huang, H., Peng, Q., Zhang, Y., Liang, Y., et al. (2023). The role of self-efficacy and psychological resilience on the relationship between perfectionism and learning motivation among undergraduate nursing students: A cross-sectional descriptive study. Journal of Professional Nursing, 47, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2023.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wu, C. (2021). Training teachers in China to use the philosophy for children approach and its impact on critical thinking skills: A pilot study. Education Sciences, 11(5), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050206 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xu, W., & Zhu, X. (2025). A cross-linguistic approach to investigating metacognitive regulation in writing among Chinese EFL learners: Insights for its trait/state distinction. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 35(1), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12615 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, R. P. (2024). A study on the self-efficacy of English writing among junior high school students. Advances in Education, 4(11), 749–753. https://doi.org/10.12677/ae.2024.14112124 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, X. S., & Zhang, L. J. (2022). Sustaining learners’ writing development: Effects of using self-assessment on their foreign language writing performance and rating accuracy. Sustainability, 14(22), 14686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142214686 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zi, F., & Zhou, X. (2006). Reliability and validity of the Chinese frost multidimensional perfectionism scale. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 14(4), 560–563. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools