Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Trait mindfulness among music-talented students: Effects of grit, resilience and flow

1 Department of Education and Learning Technology, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, 300193, Taiwan

2 Research Center for Educational System and Policy, National Academy for Educational Research, New Taipei City, 237201, Taiwan

* Corresponding Author: Wei-Cheng Chien. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 599-607. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.066823

Received 18 April 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study examined how trait mindfulness relates to grit and resilience in students and whether flow mediates these links. The study sample comprised 432 gifted and talented music students (females = 275, mean age = 14.52, SD = 0.50). The students completed four measures assessing trait mindfulness, flow, grit, and resilience, each with established psychometric validity and reliability. The findings from structural equation modeling indicate trait mindfulness had substantial direct effects on flow, resilience, and grit among students. Flow had a significant mediating effect on the relationship between trait mindfulness and grit for enhanced grit. However, the mediating effect of flow between trait mindfulness and resilience was not statistically significant. Male students self-reported higher levels of resilience than female students. These findings support the theoretical proposition that trait mindfulness underpins adaptive coping and sustained goal pursuit, with flow acting as an important mediating mechanism. For music-talented students facing intensive training and performance pressures, incorporating mindfulness-based interventions and flow-inducing activities into gifted education programs. This would strengthen resilience and grit, promoting both artistic achievement and psychological well-being.Keywords

Gifted and talented people have high mindfulness, or presence of mind, their concentration, emotional integration, and self-awareness (Tang et al., 2015; Wheeler et al., 2017). Through their professional development, people with mindfulness overcome external expectations and pressures on themselves. They also have a sense of flow, which is the psychological state of deep immersion and optimal experience during task engagement, wherein individuals lose self-consciousness and experience a distorted sense of time while maintaining full focus on the activity (Custodero, 2002; O’Neill, 1999; Chirico et al., 2015). Conceivably, musically talented students may possess higher levels of grit, defined as the enduring passion and sustained effort directed toward long-term objectives despite the presence of obstacles or setbacks (Duckworth, 2016; Credé, 2018). They are also likely to exhibit enhanced resilience, which refers to the capacity to adapt successfully to adversity while maintaining psychological well-being and goal-directed functioning (Bacchi & Licinio, 2017; Thompson et al., 2011). These attributes are particularly salient in the context of music education, where students must engage in repetitive practice, manage performance-related stress, and pursue high standards of artistic excellence.

Adolescents in music-talented classes represent a unique population that combines early cognitive and emotional development with intense performance demands. Their education often entails long hours of solitary practice, high parental and institutional expectations, and frequent public evaluation—all of which may increase vulnerability to burnout, anxiety, and psychological distress if not supported by appropriate internal coping mechanisms (Czajkowski et al., 2021; Jelen, 2021; Cohen & Bodner, 2021). Such stressors often include the pressure to achieve professional-level performance standards at a young age, intense competition, and self-imposed perfectionism, which can heighten performance anxiety and erode long-term motivation if unmanaged (Diaz, 2018; López-Íñiguez & McPherson, 2023; Holmes, 2017). Mindfulness, by fostering attentional control and emotional regulation, may help mitigate these challenges and support sustained musical engagement (Dvorak & Hernandez-Ruiz, 2021). Consequently, understanding the psychological traits that underpin grit and resilience in this group is of critical importance for educational psychology and talent development research. While previous research has examined the associations between trait mindfulness and grit primarily among adult populations, limited empirical attention has been directed toward adolescents who are in the process of identity formation and professional development. Given that musical expertise demands the integration of complex cognitive, technical, and expressive skills (Czajkowski et al., 2021; Dvorak & Hernandez-Ruiz, 2021; Hernandez-Ruiz & Dvorak, 2021; Shapiro & Weisbaum, 2020), students identified as musically talented may uniquely benefit from psychological constructs such as mindfulness, resilience, grit, and flow. However, empirical investigations exploring the role of flow in the relationship between trait mindfulness, grit, and resilience among musically gifted adolescents remain scarce. This line of inquiry holds practical significance for developing targeted psychological interventions and pedagogical strategies to support the long-term development and mental health of music-talented adolescents.

The mediating role of flow between trait mindfulness and adaptive outcomes such as grit and resilience can be understood within the perspectives of positive psychology, the theory of mindfulness, and flow theory. Positive psychology emphasises the cultivation of strengths and optimal functioning, providing a framework for understanding how positive mental states can enhance motivation and adaptability. The theory of mindfulness highlights the role of present-moment awareness and attentional control in facilitating optimal engagement (Dvorak & Hernandez-Ruiz, 2021), while flow theory explains how such engagement in challenging yet manageable tasks fosters intrinsic motivation and enjoyment (Custodero, 2002; O’Neill, 1999). Together, these perspectives suggest that flow serves as a psychological mechanism through which mindfulness promotes sustained effort (grit) and adaptive coping (resilience) in music-talented students facing the demands of long-term training.

Although trait mindfulness, resilience, flow, and grit are interrelated constructs within positive psychology, they are conceptually distinct. Trait mindfulness refers to a stable tendency to maintain present-moment awareness and non-judgmental attention to experiences (Thompson et al., 2011), whereas resilience describes an adaptive capacity to recover from stress or adversity (Bacchi & Licinio, 2017; Li et al., 2017). Flow is characterised by deep absorption and optimal experience during goal-directed activities (Mao et al., 2020), differing from mindfulness in its emphasis on task engagement rather than open monitoring. Grit reflects sustained passion and perseverance toward long-term goals (Duckworth, 2016; Credé, 2018), distinguishing it from resilience by its focus on enduring effort over extended periods rather than recovery from specific setbacks. Recognising these distinctions supports the theoretical rationale for examining their unique and combined contributions within the proposed model.

Trait mindfulness has been found to enhance artistic awareness among students learning music (Czajkowski et al., 2021; Dvorak & Hernandez-Ruiz, 2021). It contributes to music instrumental skills and interpretation (Czajkowski et al., 2021). In studies involving music professionals, higher levels of mindfulness have been associated with improved practice efficiency, reduced performance anxiety, and greater consistency in performance quality (Jelen, 2021; Cohen & Bodner, 2021). Mindfulness training interventions have further been shown to support attentional control and emotional regulation during high-stakes performances, thereby facilitating both technical accuracy and expressive depth (Diaz, 2018). Beyond individual performance, research in music education highlights the importance of pedagogical environments that foster both psychological skills and artistic growth. A scoping review of gifted music learners’ education emphasised the role of caring, student-centred approaches in promoting sustained engagement and well-being (López-Íñiguez & McPherson, 2023). Similarly, policy-oriented analyses have underscored that effective music education must move beyond talent myths to integrate structured opportunities for developing cognitive, emotional, and creative capacities (Scripp et al., 2013). Such findings underscore the potential value of mindfulness as a psychological resource that not only enhances individual musical performance but also aligns with broader educational strategies for nurturing gifted and talented students.

Mindful students would also have high levels of grit. Grit motivates individuals to strive forward and maintain positive beliefs in leading a more virtuous and proactive life (Duckworth, 2016), and is associated with greater determination and endurance when facing adversity and setbacks (Credé, 2018). In the music profession, grit has been found to predict sustained engagement in deliberate practice, higher achievement levels, and greater resilience in managing performance-related challenges (Olander & Saarikallio, 2022; Persellin & Davis, 2017). Studies with collegiate and professional musicians have shown that those with higher grit scores tend to maintain consistent practice routines, recover more effectively from performance failures, and persist in pursuing long-term artistic goals despite external pressures and competition (López-Íñiguez & McPherson, 2023; Scripp et al., 2013). Such findings suggest that grit, when supported by mindfulness, can play a crucial role in helping music-talented students sustain motivation and achieve excellence over extended periods of training and performance demands.

Trait mindfulness and resilience

Students who possess resilience have high learning motivation, academic performance, self-efficacy, and sense of identity (Bacchi & Licinio, 2017; Li et al., 2017). Previous research has indicated a correlation between trait mindfulness and resilience (Aini et al., 2021; Mutavdžin & Bogunović, 2019; Thompson et al., 2011). In music training, individuals face various setbacks, and resilience helps them adapt to an open mindset and positive psychological state (Holmes, 2017). Empirical studies have shown that resilient musicians are better able to recover from performance failures, sustain practice motivation during demanding rehearsal schedules, and adapt to the pressures of auditions and public performances (López-Íñiguez & McPherson, 2023; Diaz, 2018; Hess, 2019). Resilience in this context is also linked to the development of effective coping strategies, reduced stress reactivity, and long-term persistence in artistic goals (Scripp et al., 2013; Guo, 2025). Collectively, this evidence highlights resilience as a crucial psychological resource in high-level music performance, supporting both academic success and emotional well-being in music-talented students.

Existing research suggests that trait mindfulness may serve as a psychological resource that strengthens resilience by enhancing emotional regulation, attentional control, and adaptive coping strategies (Thompson et al., 2011; Aini et al., 2021; Mutavdžin & Bogunović, 2019). Students with higher trait mindfulness are more capable of recognising and accepting challenging experiences without excessive rumination, thereby reducing stress reactivity and maintaining goal-directed functioning (Bacchi & Licinio, 2017; Li et al., 2017). In the context of music-talented education, such mindful awareness can facilitate a constructive interpretation of performance setbacks, helping students recover more effectively and sustain motivation for long-term artistic development.

Flow contributes to alleviating anxiety and strengthening resilience (Mao et al., 2020). In the music-class students’ learning process, when they enter a state of flow, they can regulate their inner anxiety with a heightened sense of pleasure, thereby adapting to various external environments and achieving internal psychological balance. Therefore, it is believed that flow may influence resilience. Flow may also serve as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between trait mindfulness and resilience, as the heightened attentional control and emotional regulation fostered by flow enable students with higher trait mindfulness to recover more effectively from challenges and maintain adaptive functioning (Thompson et al., 2011; Mao et al., 2020). Flow may also serve as a mediator in the relationship between trait mindfulness and grit (Mutavdžin & Bogunović, 2019). In the context of music learning and performance, flow experiences have been associated with enhanced practice quality, increased persistence, and reduced susceptibility to performance anxiety (Custodero, 2002; Antonini Philippe et al., 2021). For instance, O’Neill (1999) found that young musicians who frequently experienced flow during practice demonstrated higher levels of concentration and greater willingness to engage in deliberate practice over extended periods. Similarly, Chirico et al. (2015) reported that flow states in musical activities promoted emotional regulation and intrinsic motivation, which in turn supported perseverance in skill development. These findings suggest that, within music-talented programs, flow not only enhances performance quality but may also function as a psychological mechanism that links mindfulness to grit by sustaining motivation and adaptive coping in the face of long-term training demands.

Accordingly, we posit that the trait mindfulness of music-class students facilitates the emergence of flow, helping them regulate stress and sustain deep task engagement. In our model, flow functions as the mediating mechanism linking trait mindfulness to both grit and resilience, with grit and resilience specified as parallel outcome variables. Prior work indicates that mindfulness can support attentional focus and task absorption that give rise to flow (Mohebi et al., 2021; Lee, 2022; Ovington et al., 2018), and that flow, in turn, enhances persistence and adaptive coping (Rahimpour et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2021; Chirico et al., 2015; Mao et al., 2020). Thus, the experience of flow is expected to transmit the effects of trait mindfulness to greater perseverance toward long-term goals (grit) and improved recovery from challenges (resilience).

The present study investigates the interrelationships among trait mindfulness, flow, resilience, and grit in junior high school students enrolled in music-talented classes. Drawing upon positive psychology, the theory of mindfulness, and flow theory, this study conceptualises flow as a key psychological mechanism through which mindfulness fosters sustained effort (grit) and adaptive coping (resilience). Given the psychological demands and challenges associated with music education, understanding these associations can provide valuable insights into the motivational and emotional processes that support persistence and adaptability in young music learners. Accordingly, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

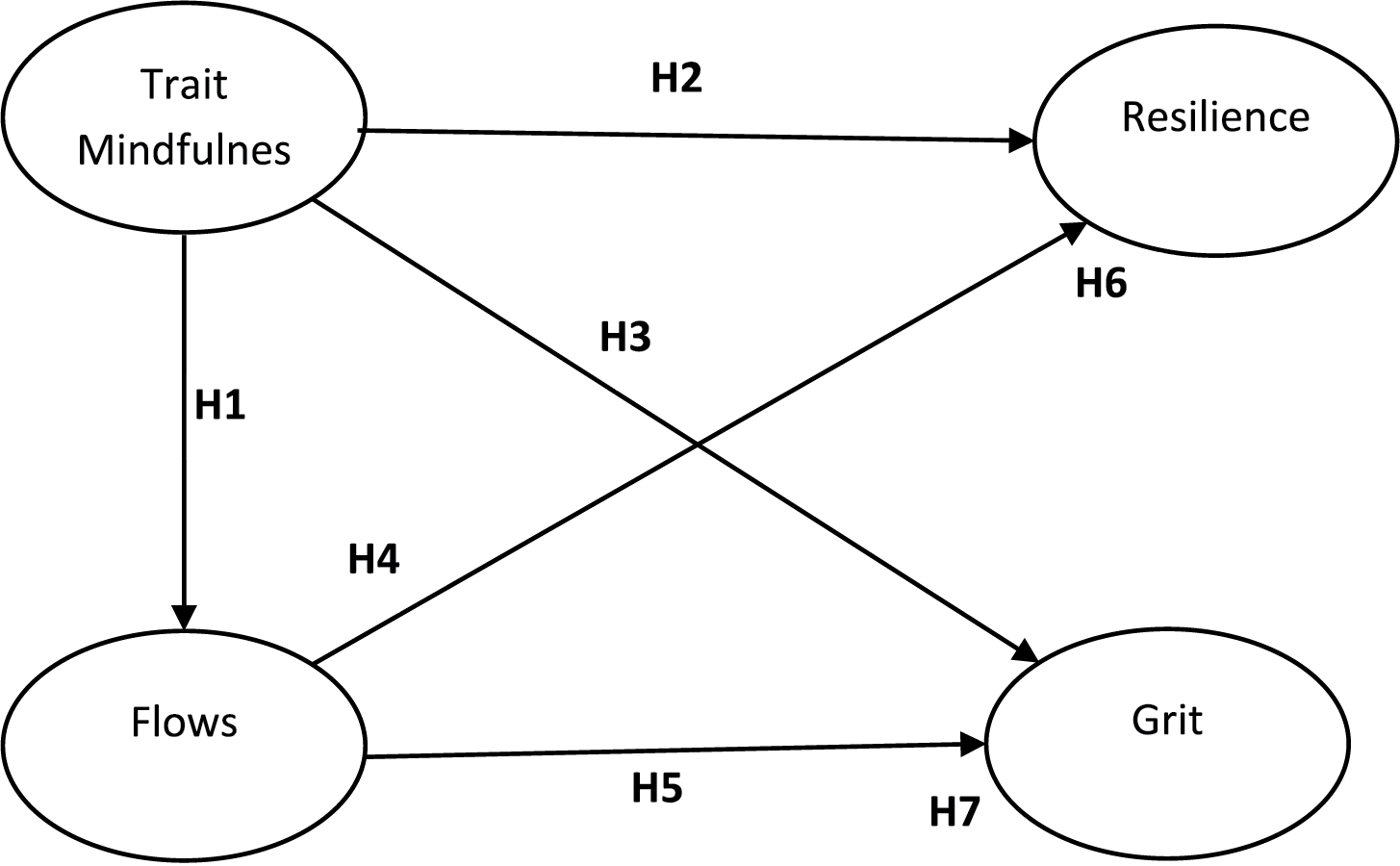

H1: Trait mindfulness is significantly and positively related to flow.

H2: Trait mindfulness is significantly and positively related to resilience.

H3: Trait mindfulness is significantly and positively related to grit.

H4: Flow is significantly and positively related to resilience.

H5: Flow is significantly and positively related to grit.

H6: Flow mediates the relationship between trait mindfulness and resilience.

H7: Flow mediates the relationship between trait mindfulness and grit.

The conceptual model summarising these hypotheses is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research framework diagram

Overall, this study makes several contributions to the literature. First, it extends research on mindfulness and positive psychology to the context of junior high school students enrolled in music-talented classes, a population that has been underrepresented in previous empirical studies. Second, it advances an integrated model in which flow is examined as a mediating mechanism linking trait mindfulness to resilience and grit, thereby addressing the interrelationships among these constructs rather than studying them in isolation. Third, by focusing on a high-pressure educational environment that demands both technical proficiency and emotional regulation, this study provides insights with direct implications for talent development programs and educational psychology interventions.

The study sample consisted of 432 junior high school students enrolled in officially designated music-talented classes in Taiwan. These classes are specialized educational tracks designed for students who demonstrate exceptional musical aptitude. Admission into these classes is highly competitive and based on a combination of formal auditions, theoretical knowledge assessments, and evaluations of prior musical training and performance achievements. Students in these programs receive intensive instruction in their primary instrument or voice, music theory, and ensemble performance, in addition to the standard junior high school curriculum. Cluster sampling was employed to select participants from several schools offering music-talented classes. Among the participants, 157 were boys (36.34%) and 275 were girls (63.66%). In terms of age distribution, 207 students were 14 years old (47.92%), and 225 students were 15 years old (52.08%). All participants had undergone multiple years of formal music training and engaged in daily practice sessions as part of their curriculum, with frequent participation in school concerts, competitions, and public performances.

Self-report questionnaires were used in this study to measure the four main constructs. The instruments were translated into Chinese and culturally adapted for junior high school students in Taiwan. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Trait Mindfulness was assessed using the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) developed by Greco et al. (2011), consisting of 10 items. A sample item is: “When things do not go well, I do not get upset easily.” The scale showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.93). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good model fit: χ² = 80.27, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.95; AGFI = 0.91; NFI = 0.93; CFI = 0.95; RMR = 0.03; RMSEA = 0.07. Flow was measured using the Flow Short Scale (Engeser & Rheinberg, 2008), which comprises 10 items that assess the degree of absorption and enjoyment during musical engagement. A representative item is: “I find it easy to concentrate.” The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.97). CFA results supported a good model fit: χ² = 57.48, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.94; AGFI = 0.91; NFI = 0.96; CFI = 0.98; RMR = 0.02; RMSEA = 0.05. Grit was evaluated using the Short Grit Scale (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009). A sample item is: “I stay enthusiastic about things I am passionate about.” The internal consistency was excellent (α = 0.95), and CFA results indicated a good model fit: χ² = 57.81, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.95; AGFI = 0.92; NFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.96; RMR = 0.02; RMSEA = 0.07. Resilience was measured using a revised version of the Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008). A representative item is: “I can bounce back quickly after experiencing something upsetting.” The internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.90). CFA results showed satisfactory model fit: χ² = 29.09, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.97; AGFI = 0.94; NFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.98; RMR = 0.02; RMSEA = 0.07.

Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board. The study aims were explained to participants, and it meets the exemption criteria for ethical review and informed consent set by the Research Ethics Committee of National Tsing Hua University. Data were collected during regular music-talented classes using self-report questionnaires on trait mindfulness, flow, grit, and resilience. Standardised instructions were provided, participation was voluntary and anonymous, and completion took approximately 25 min under researcher supervision.

Data were analysed using SPSS for independent-sample t-tests to examine gender differences in trait mindfulness, flow, resilience, and grit. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was conducted in Mplus to test the effects of trait mindfulness on resilience and grit, as well as the mediating role of flow. Mediation analysis employed the bootstrap resampling method (1000 samples), and significance was determined using bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

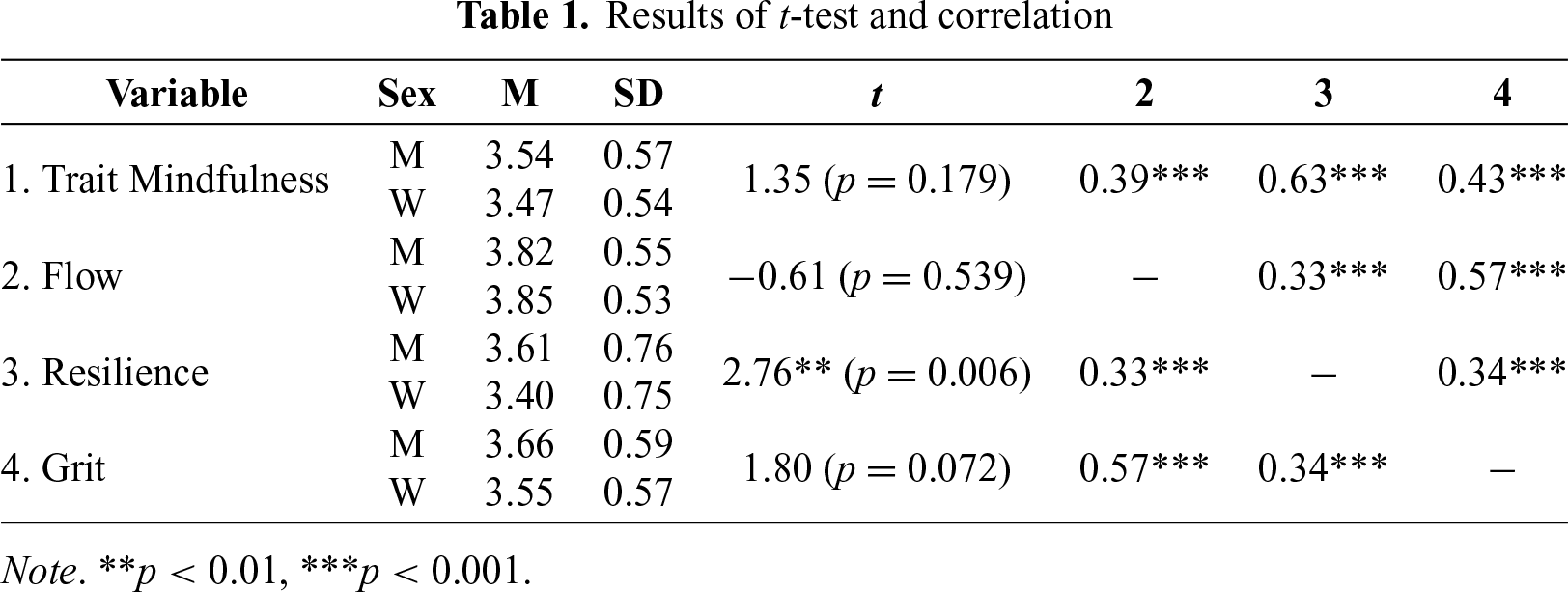

Table 1 summarized the t-test analysis results and zero-order correlations among sex, trait mindfulness, flow, resilience, and grit. The t-test results indicated no significant differences between sex and trait mindfulness, flow, and grit. However, a significant difference was found in resilience, with men exhibiting higher levels of resilience than women. The zero-order correlations suggest significant associations among mindfulness, flow, resilience, and grit traits, indicating preliminary interrelationships.

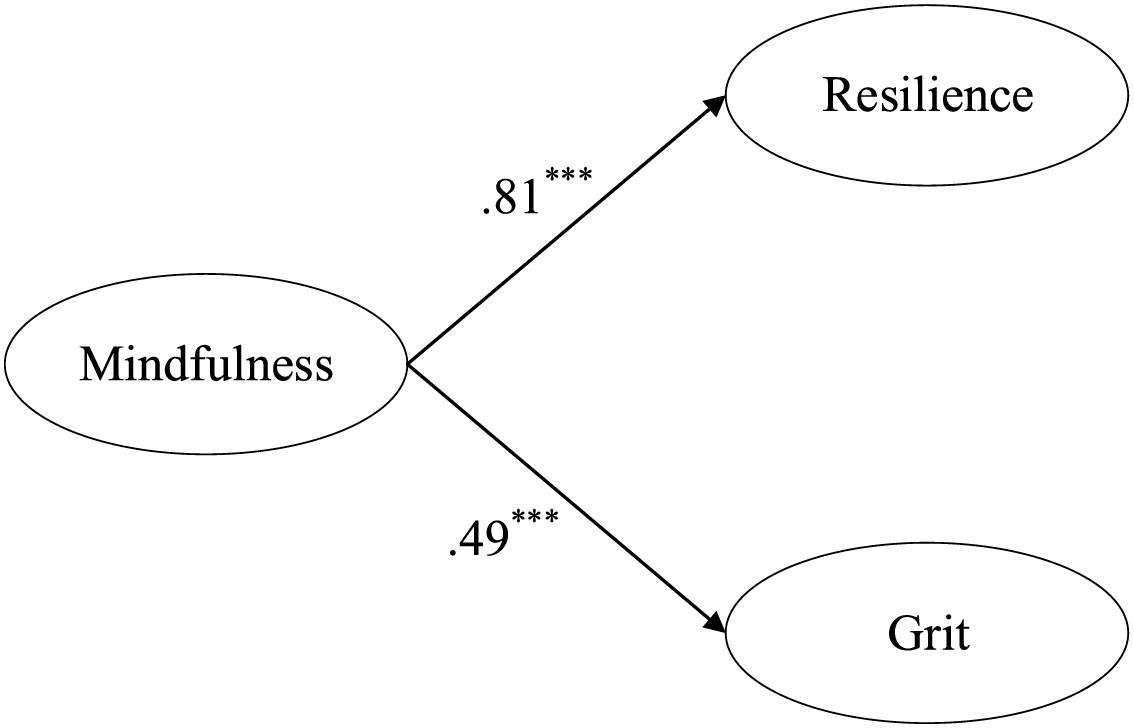

To examine the mediating role of flow in the model, following Baron and Kenny’s (1986) suggestion, SEM was first conducted to examine the direct effects of trait mindfulness on resilience and grit. The goodness-of-fit test showed good model fit with χ2 = 119.14 (p < 0.001), GFI = 0.95, AGFI = 0.92, NFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.96, RMR = 0.02, RMSEA = 0.06. The standardised estimates are presented in Figure 2. The standardised coefficient for the direct effect of trait mindfulness on resilience was 0.81 (p < 0.001), and that on grit was 0.49 (p < 0.001). These results indicate that trait mindfulness had a significant direct effect on resilience and grit.

Figure 2: The standardised estimates of the direct effects model in SEM. Note. ***p < 0.001.

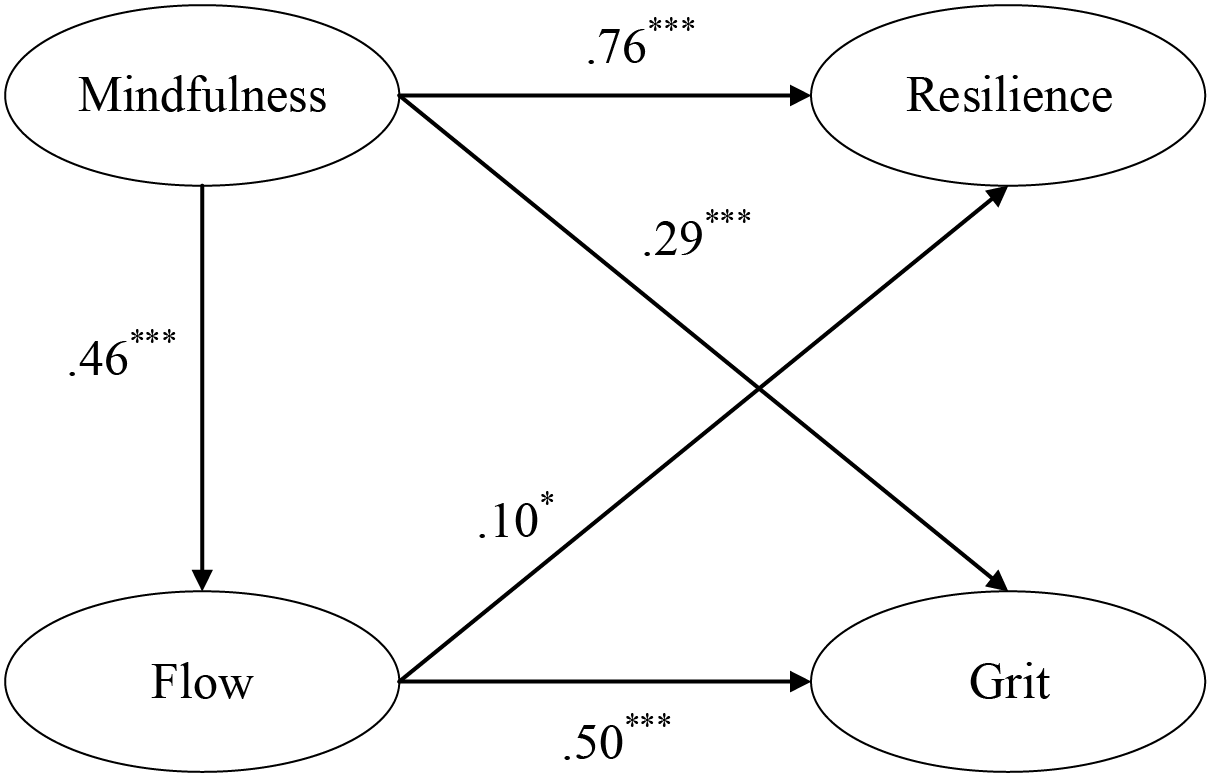

Using SEM, the influence of trait mindfulness on resilience and grit was analysed, with flow as a mediating variable. The goodness-of-fit test revealed a good model fit, with χ2 = 226.46 (p < 0.001), GFI = 0.92, AGFI = 0.87, NFI = 0.91, CFI = 0.93, RMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.08. The standardised estimates are presented in Figure 3. According to Figure 3, in the overall model, trait mindfulness had significant direct effects on flow, resilience, and grit, with standardised coefficients of 0.46 (p < 0.001, H1 supported), 0.76 (p < 0.001, H2 supported), and 0.29 (p < 0.001, H3 supported), respectively. Flow had significant direct effects on resilience and grit, with standardised coefficients of 0.10 (p = 0.039 < 0.05, H4 supported) and 0.50 (p < 0.001, H5 supported), respectively, although the effect of flow on resilience was relatively small. In the direct effects model (Figure 2), trait mindfulness had a significant direct effect on resilience (β = 0.81, p < 0.001) and grit (β = 0.49, p < 0.001). However, in the mediation model (Figure 3), trait mindfulness had direct effects on resilience (β = 0.76, p < 0.001) and grit (β = 0.29, p < 0.001), but trait mindfulness did not have an indirect effect on resilience through flow (β = 0.46 * 0.10 = 0.05, p = 0.086 > 0.05, H6 not supported). Conversely, it had an indirect effect on grit through flow (β = 0.46 * 0.50 = 0.23, p < 0.001, H7 supported). Comparing the results of the mediation model in Figure 3 with the direct effects model in Figure 2, it can be concluded that the significant direct effect of trait mindfulness on grit decreased from 0.49 to 0.29, indicating a significant mediating effect of flow, thus suggesting a ‘partial mediating effect’.

Figure 3: The standardised estimates of the mediation model in SEM. Note. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

This study utilised t-tests to analyse sex differences in trait mindfulness, flow, resilience, and grit. These results were consistent with previous research findings that showed no significant sex differences in trait mindfulness, flow, or grit (Chen & Hsieh, 2014; Chou, 2019; Czerwiński et al., 2022; Ornoy & Cohen, 2021). However, this study found that men exhibited higher levels of resilience than women, which aligns with the findings of Valenzuela et al. (2020). While the present study found no significant gender differences in trait mindfulness, flow, or grit, previous research in music education contexts has reported gender-related variations in these constructs. For example, Gan et al. (2023) found that female participants scored higher on the describing and observing facets of mindfulness, whereas males scored higher on nonreactivity. Quadir et al. (2014) reported that female learners exhibited significantly higher mean flow scores than males in an English learning achievement system. Similarly, Sigmundsson and Leversen (2024) observed that males scored higher in flow, while females scored higher in grit. Such differences may be attributable to variations in age composition or cultural background.

Using SEM, this study examined the direct effects of trait mindfulness on resilience and grit among music-class students. The results revealed that trait mindfulness had significant positive direct effects on resilience and grit, aligning with research suggesting that it contributes to the development of resilience (Aini et al., 2021; Mutavdžin & Bogunović, 2019; Thompson et al., 2011) and grit (Lee, 2022; Mohebi et al., 2021; Rusadi et al., 2021; Vela et al., 2018). It can be inferred that students with higher levels of trait mindfulness demonstrated higher levels of resilience and grit. This study found that flow has a positive direct effect on both resilience and grit, which is consistent with research suggesting that flow enhances resilience (Liu et al., 2021; Mao et al., 2020), and that there is a relationship between flow and grit (Dickinson, 2020; Miksza & Tan, 2015; Rahimpour et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2021; Von Culin et al., 2014). However, this study found that the direct impact of flow on resilience was relatively small. When comparing the direct effects of trait mindfulness and flow on resilience and grit, the influence of trait mindfulness on resilience far outweighed that of flow. This is likely because the pressures and setbacks experienced during training are the primary challenges that students in music classes need to overcome in terms of resilience (Cohen & Bodner, 2021; Kotera et al., 2021; Mutavdžin & Bogunović, 2019), and trait mindfulness, compared to flow, is more effective in releasing and regulating stress. However, in terms of grit, the influence of flow was significantly greater than that of trait mindfulness, even though both factors had notable effects. This is because the demonstration of grit by music-class students is primarily influenced by their diligent willpower (Dickinson, 2020; Von Culin et al., 2014), and the experiences gained through flow in the process of repeated practice more easily reinforce the development of grit (Miksza & Tan, 2015; Tan et al., 2021; Von Culin et al., 2014).

The mediation analysis results provided evidence that trait mindfulness did not mediate the relationship between flow and resilience. Although some studies have suggested the possibility of an intermediate effect of flow on the relationship between trait mindfulness and resilience (Beerse et al., 2020; Mutavdžin & Bogunović, 2019), this study confirms that while there is a relatively small mediating effect, it does not reach a significant level of 0.05. However, it should be noted that this study cannot rule out the possibility that the lack of significance may be due to the insufficient sample size. Furthermore, the mediation analysis results revealed that trait mindfulness had a significant indirect effect on the development of grit through the mediating role of flow. Students who possess trait mindfulness can enhance their grit in learning behaviours through their state of flow. This finding aligns with Dickinson’s (2020) notion that the experience of flow generated during continuous practice contributes to developing diligent willpower and realizing personal potential (Wang et al., 2020). It enables rapid skill improvement and sustained efforts toward higher goals (Cohen & Bodner, 2021; Woody, 2020). The present study provides evidence supporting the partial mediating effect of flow on the influence of trait mindfulness on grit. This is consistent with Raphiphatthana and Jose’s (2020) research, which suggests the presence of mediating variables in the relationship between trait mindfulness and grit.

In conclusion, under the mediating effect of flow, music-class students with trait mindfulness are more likely to approach their learning goals and career development proactively, determined, confident, and self-affirmingly. This enhances their learning plasticity and enables them to succeed in their musical journeys. Learning specialised music subjects requires a significant investment of time and effort in mastering technical skills and achieving a perfect expression of musical compositions. These factors motivate students’ learning and enrich their learning experiences. Therefore, traits of mindfulness, flow, resilience, and grit are indispensable motivational characteristics in the music-learning process.

This study investigated the relationships between mindfulness, flow, resilience, and grit traits in music-class students. The results indicated no significant sex differences in mindfulness, flow, and grit. However, male students exhibited higher levels of resilience than female students, suggesting that men can better regulate their anxiety, tension, and discomfort in music learning. Furthermore, this study revealed that trait mindfulness encompasses the motivational factors that sustain music-class students’ continuous learning and the intrinsic drive to adapt to the learning and performance environment, enabling them to enjoy their learning experiences. This, in turn, strengthens their sense of determination and resilience in pursuing their musical journey. In recent years, research on trait mindfulness has increased, primarily focusing on empirical studies investigating the associations between pairs of variables. The aim was to understand the developmental status of students’ psychological or behavioural performance under such traits. However, this approach overlooks the potential mediating factors of trait mindfulness in the process, thereby neglecting other factors that may influence the development of dependent variables. Flow generation relies on external guidance, and trait mindfulness is an excellent guiding medium. If music-class students can generate flow through trait mindfulness, their perception of time and temporary self-consciousness will change during the learning and practice processes. With high skill mastery, they can achieve self-rewarding performance, entering a state of total immersion in the activity. Thus, they can effectively regulate negative emotions such as fear and stress through a heightened sense of pleasure, constantly striving for higher learning goals, and unlocking their self-potential to achieve self-fulfilment. Therefore, this study examined the mediating role of flow and explored the impact of trait mindfulness on resilience and grit in music-class students. Although flow did not significantly mediate the relationship between trait mindfulness and resilience, trait mindfulness still exerted a robust direct influence on resilience. Higher levels of trait mindfulness enhance resilience, indicating solid psychological resilience that enables students to cope with various challenges and adversities. However, this study confirmed that trait mindfulness directly influences grit and exerts a significant indirect impact on grit through the mediating effect of flow. As trait mindfulness increases, the flow level improves, leading to a substantial enhancement in grit performance. Thus, trait mindfulness can strengthen students’ grit expression through the manifestation of flow.

The study enriches the literature by highlighting the pivotal role of flow in the psychological functioning of music-talented adolescents, offering a theoretically grounded and empirically tested model that integrates mindfulness, resilience, and grit. Theoretically, it extends positive psychology and flow frameworks by positioning flow as a mediating mechanism that links dispositional mindfulness to both sustained effort and adaptive coping, thereby clarifying the interplay among these constructs in a high-pressure educational context. In music classes, students must maintain continuous awareness of their self-expression, exerting control over breathing, performance techniques, and musical interpretation while relying on heightened sensory perception. Cultivating mindfulness traits and emphasising present-moment focus and self-awareness can enhance self-presentation abilities, support the regulation of fears and negative emotions, and promote acceptance and non-judgment when facing failures or setbacks. With refined observation, awareness, and acceptance, students can explore personal musical interpretation styles through professional performances, ultimately delivering superior musical outcomes with heightened aesthetic sensibility. These findings not only advance understanding of how positive psychological resources interact in demanding music-class education settings but also inform the design of targeted interventions to enhance grit and resilience among students in music-talented programs.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all participants who took the time to complete the questionnaire. Their valuable contributions and willingness to share their experiences made it possible for this study to be successfully completed.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chuan-Chung Hsieh, Ting-Jung Chang; data collection: Ting-Jung Chang; analysis and interpretation of results: Chuan-Chung Hsieh, Wei-Cheng Chien; draft manuscript preparation: Wei-Cheng Chien. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [Wei-Cheng Chien], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board. The study aims were explained to participants, and it meets the exemption criteria for ethical review and informed consent set by the Research Ethics Committee of National Tsing Hua University

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aini, D. K., Stück, M., Sessiani, L. A., & Darmuin, D. (2021). How do they deal with the Pandemic? The effect of secure attachment and mindfulness on adolescent resilience. Psikohumaniora: Jurnal Penelitian Psikologi, 6(1), 103–116. http://10.21580/pjpp.v6i1.6857. [Google Scholar]

Antonini Philippe, R., Kosirnik, C., Ortuño, E., & Biasutti, M. (2021). Flow and music performance: Professional musicians and music-class students’ views. Psychology of Music, 50(4), 1023–1038. https://doi.org/10.1177/03057356211030987 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bacchi, S., & Licinio, J. (2017). Resilience and psychological distress in psychology and medical students. Academic Psychiatry, 41(2), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-016-0488-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beerse, M. E., Van Lith, T., & Stanwood, G. (2020). Therapeutic psychological and biological responses to mindfulness-based art therapy. Stress and Health, 36(4), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2937 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, P.-F., & Hsieh, Y.-M. (2014). A study of the relationship among the positive traits, music passion and subjective well-being of the students in college concert bands. Journal of Student Organization, 2, 29–50. https://doi.org/10.6909/JSO.201401_(2).0002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chirico, A., Serino, S., Cipresso, P., Gaggioli, A., & Riva, G. (2015). When music flows. State and trait in musical performance, composition and listening: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 906. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00906 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chou, S.-C. (2019). An investigation of career development and planning strategies for musically gifted junior high school students in Taiwan. School Administrators Research Association, 119, 100–113. https://doi.org/10.6423/HHHC.201901_(119).0004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cohen, S., & Bodner, E. (2021). Flow and music performance anxiety: The influence of contextual and background variables. Musicae Scientiae, 25(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864919838600 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Credé, M. (2018). What shall we do about grit? A critical review of what we know and what we don’t know. Educational Researcher, 47(9), 606–611. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X18801322 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Custodero, L. A. (2002). Seeking challenge, finding skill: Flow experience and music education. Arts Education Policy Review, 103(3), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632910209600288 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Czajkowski, A. L., Greasley, A. E., & Allis, M. (2021). Mindfulness for singers: A mixed methods replication study. Music and Science, 4, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/20592043211044816 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Czerwiński, S. K., Lawendowski, R., Kierzkowski, M., & Atroszko, P. A. (2022). Can perseverance of effort become maladaptive? Study addiction moderates the relationship between this component of grit and well-being among music academy students. Musicae Scientiae, 27(3), 10298649221095135. https://doi.org/10.1177/10298649221095135 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Diaz, F. M. (2018). Relationships among meditation, perfectionism, mindfulness, and performance anxiety among collegiate music students. Journal of Research in Music Education, 66(2), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429418765447 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dickinson, S. (2020). Grit and flow as prescriptions for self-actualization. Journal of Wellness, 2(2), 4. https://doi.org/10.18297/jwellness/vol2/iss2/4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Duckworth, A. L. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance. New York, NY, USA: Scribner. [Google Scholar]

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT-S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dvorak, A. L., & Hernandez-Ruiz, E. (2021). Comparison of music stimuli to support mindfulness meditation. Psychology of Music, 49(3), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735619878497 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Engeser, S., & Rheinberg, F. (2008). Flow, performance and moderators of challenge-skill balance. Motivation and Emotion, 32(3), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9102-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gan, R., Wei, Y., Sun, L., Zhang, L., Wang, J., et al. (2023). Age and sex-specific differences of mindfulness traits with measurement invariance controlled in Chinese adult population: A pilot study. Heliyon, 9(9), e19608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19608 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Greco, L. A., Baer, R. A., & Smith, G. T. (2011). Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 606–614. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022819 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guo, Y. (2025). Enhancing resilience and well-being in music education majors: Promoting academic and emotional development. GBP Proceedings Series, 5, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.71222/hk44sa03 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hernandez-Ruiz, E., & Dvorak, A. L. (2021). Music and mindfulness meditation: Comparing four music stimuli composed under similar principles. Psychology of Music, 49(6), 1620–1636. https://doi.org/10.1177/030573562096979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hess, J. (2019). Moving beyond resilience education: Musical counterstorytelling. Music Education Research, 21(5), 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1647153 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Holmes, P. (2017). Towards a conceptual framework for resilience research in music training and performance: A crossdiscipline review. Music Performance Research, 8, 114–132. [Google Scholar]

Jelen, B. (2021). The relationships between music performance anxiety and the mindfulness levels of music teacher candidates. International Education Studies, 14(10), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v14n10p116 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kotera, Y., Green, P., & Sheffield, D. (2021). Positive psychology for mental well-being of UK therapeutic students: Relationships with engagement, motivation, resilience and self-compassion. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20, 1611–1626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00466-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, M. (2022). Nursing students’ grit, socio-cognitive mindfulness, and achievement emotions: Mediating effects of socio-cognitive mindfulness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 3032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, H., Martin, A. J., & Yeung, W.-J. J. (2017). Academic risk and resilience for children and young people in Asia. Educational Psychology, 37(8), 921–929. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1331973 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, F., Zhang, Z., Liu, S., & Zhang, N. (2021). Examining the effects of brief mindfulness training on athletes’ flow: The mediating role of resilience. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2021, 6633658. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6633658 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

López-Íñiguez, G., McPherson, G. E. (2023). Caring approaches to young, gifted music learners’ education: A PRISMA scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1167292. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1167292 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mao, Y., Yang, R., Bonaiuto, M., Ma, J., & Harmat, L. (2020). Can flow alleviate anxiety? The roles of academic self-efficacy and self-esteem in building psychological sustainability and resilience. Sustainability, 12(7), 2987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072987 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Miksza, P., & Tan, L. (2015). Predicting collegiate wind players’ practice efficiency, flow, and self-efficacy for self-regulation: An exploratory study of relationships between teachers’ instruction and students’ practicing. Journal of Research in Music Education, 63(2), 162–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429415583474 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mohebi, M., Sadeghi-Bahmani, D., Zarei, S., Gharayagh Zandi, H., & Brand, S. (2021). Examining the effects of mindfulness-acceptance-commitment training on self-compassion and grit among elite female athletes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010134 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mutavdžin, D., Bogunović, B. (2019). Learning preferences of the musically gifted. In: Proceedings of PAM-IE Belgrade 2019, Belgrade, Serbia. [Google Scholar]

Olander, K., & Saarikallio, S. (2022). Experiences of grit and flourishing in Finnish comprehensive schools offering long-term support to instrument studies: Building a new model of positive music education and grit. Finnish Journal of Music Education, 25(2), 89–111. [Google Scholar]

Ornoy, E., Cohen, S. (2021). The effect of mindfulness meditation on the vocal proficiencies of music education students. Psychology of Music, 50(5), 03057356211062262. https://doi.org/10.1177/03057356211062262 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ovington, L. A., Saliba, A. J., & Goldring, J. (2018). Dispositions toward flow and mindfulness predict dispositional insight. Mindfulness, 9(2), 585–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0800-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

O’Neill, S. (1999). Flow theory and the development of musical performance skills. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 141, 129–134. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40318998 [Google Scholar]

Persellin, D., Davis, V. (2017). Harnessing the power of failure in your music classroom: Grit, growth mindset, & greatness. Southwestern Musician, 85(7), 68–73. [Google Scholar]

Quadir, B., Yang, J.-C., & Chen, Y.-H. (2014). Gender differences in flow state in an English learning environment achievement system. In: H. Ogata, et al. (Eds.Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Computers in Education (ICCE 2014) (pp. 744–749Asia-Pacific Society for Computers in Education. [Google Scholar]

Rahimpour, S., Arefi, M., & Manshaii, G. (2019). The effectiveness of mindfulness education on flow and grit of female high school students. Studies in Learning and Instruction, 11(1), 70–91. [Google Scholar]

Raphiphatthana, B., & Jose, P. E. (2020). The relationship between dispositional mindfulness and grit moderated by meditation experience and culture. Mindfulness, 11(3), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01265-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rusadi, R. M., Sugara, G. S., & Isti’adah, F. N. (2021). Effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on academic grit among university student. Current Psychology, 42(6), 4620–4629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01795-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scripp, L., Ulibarri, D., & Flax, R. (2013). Thinking beyond the myths and misconceptions of talent: Creating music education policy that advances music’s essential contribution to twenty-first-century teaching and learning. Arts Education Policy Review, 114(2), 54–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2013.769825 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shapiro, S., Weisbaum, E. (2020). History of mindfulness and psychology. In: Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.678 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sigmundsson, H., & Leversen, J. S. R. (2024). Exploring gender differences in the relations between passion, grit and flow. Acta Psychologica, 251(1), 104551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2024.104551 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P.et al. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tan, J., Yap, K., & Bhattacharya, J. (2021). What does it take to flow? Investigating links between grit, growth mindset, and flow in musicians. Music and Science, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059204321989529 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Thompson, R. W., Arnkoff, D. B., & Glass, C. R. (2011). Conceptualizing mindfulness and acceptance as components of psychological resilience to trauma. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 12(4), 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838011416 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Valenzuela, R., Codina, N., & Pestana, J. V. (2020). Gender-differences in conservatoire music practice maladjustment. Can contextual professional goals and context-derived psychological needs satisfaction account for amotivation variations? PLoS One, 15(5), e0232711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232711 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Vela, J. C., Smith, W. D., Whittenberg, J. F., Guardiola, R., & Savage, M. (2018). Positive psychology factors as predictors of Latina/o college students’ psychological grit. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 46(1), 2–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12089 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Von Culin, K. R., Tsukayama, E., & Duckworth, A. L. (2014). Unpacking grit: Motivational correlates of perseverance and passion for long-term goals. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(4), 306–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.898320 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Z., Yang, X., & Zhang, X. (2020). Relationships among boredom proneness, sensation seeking and smartphone addiction among Chinese college students: Mediating roles of pastime, flow experience, and self-regulation. Technology in Society, 62, 101319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101319 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wheeler, M. S., Arnkoff, D. B., & Glass, C. R. (2017). The neuroscience of mindfulness: How mindfulness alters the brain and facilitates emotion regulation. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1471–1487. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0742-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Woody, R. H. (2020). Dispelling the die-hard talent myth: Toward equitable education for musical humans. American Music Teacher, 70(2), 22–25. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools