Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Psychological capital effects on employability among tertiary students are mediated by career values and learning engagement

School of Education, Department of Psychology, Jianghan University, Wuhan, 430056, China

* Corresponding Author: Xianglian Yu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 565-573. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.067055

Received 24 April 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the mediating roles of career values and learning engagement in the relationship between psychological capital and employability among university students. Data were collected from 5434 students across three Chinese universities (male = 1930; female = 3504; M = 23.84 years, SD = 2.55). Regression analyses indicated that psychological capital significantly predicted higher employability. Both career values and learning engagement independently and jointly mediated this relationship, thereby strengthening the overall effect. Psychological capital not only directly enhanced students’ employability but also exerted indirect effects through career values and learning engagement. These findings align with Resource-Based Theory, which conceptualizes psychological capital as a core internal resource that fosters employability through value-driven motivation and academic engagement. The results contribute to a deeper understanding of the psychological mechanisms underpinning employability among university students. Practically, the study highlights the importance of integrating psychological resource development, career values clarification, and learning engagement enhancement into higher education programs to better support students’ career readiness. Promoting constructive career values—such as professional growth, social contribution, and alignment with personal goals—may facilitate more adaptive career decisions and strengthen employability.Keywords

In today’s increasingly competitive and rapidly evolving global labor market, university graduates face mounting employability challenges. Employability is commonly defined as an individual’s capacity to secure, sustain, and, when necessary, regain employment (Locke et al., 2002). Enhancing the employability of university students has become a critical strategy for mitigating employment pressures. Prior research demonstrates that employability is not only a prerequisite for entry into the workforce but also a fundamental condition for ensuring high-quality and sustainable employment outcomes among tertiary students (Scandurra et al., 2023). Resource-Based Theory (RBT) suggests that essential resources—such as human, social, and psychological capital—are irreplaceable assets that can be transformed into employability within occupational contexts, thereby shaping job-related behaviors and performance (Wernerfelt, 1984). Early studies highlighted that students’ self-evaluations significantly predict their perceived employability (Mazalin & i Parmač Kovačić, 2015). As the field has advanced, internal psychological factors have increasingly been recognized as key predictors of employability, with career adaptability emerging as one of the most critical (Kwon, 2019). Psychological capital, conceptualized as a positive psychological state, has been empirically shown to predict employability robustly (Harari et al., 2021). Additionally, career values and learning engagement have drawn scholarly attention as potential determinants of employability. Whether students with well-defined career values and strong learning engagement can more effectively meet labor market demands and demonstrate greater employability warrants further investigation. Accordingly, this study aims to systematically examine the relationship between psychological capital and employability among university students, with a specific focus on the mediating roles of career values and learning engagement.

Psychological capital and employability

Psychological capital refers to a set of positive psychological states that enable individuals to enhance their personal development and performance. It comprises four core components: hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism (Luthans et al., 2005). Since its introduction, research on psychological capital has predominantly centered on the fields of management and career development, producing substantial empirical evidence. University students, situated at a pivotal stage of life and career exploration, particularly benefit from psychological capital. As a positive psychological resource, it fosters an optimistic outlook on the future, encourages exploration of career pathways aligned with individual resources, and thereby establishes a solid foundation for strengthening employability (Ashriyana & Lestari, 2023). Furthermore, graduates with high levels of career proactivity can harness psychological capital to actively enhance their employability (Ayala Calvo & Manzano García, 2021) . Psychological capital also plays a critical role in helping students manage stress, a factor that significantly contributes to employability development (Huang et al., 2025). Drawing upon Positive Organizational Behavior theory, Luthans emphasized the malleability of psychological capital and its essential role in cultivating competitive advantages in the labor market (Zhang et al., 2024). Numerous empirical studies have consistently confirmed the positive predictive effect of psychological capital on university students’ employability (Caballero et al., 2020; Dai & Pham, 2024; Tung & Huong, 2023).

Career values refer to the orientations individuals hold regarding career choices and occupational behaviors, reflecting how they judge the attractiveness and importance of different occupations and representing the manifestation of personal values in career decision-making (Schwartz, 1999). Research indicates that the employment goals of contemporary university students often display a strong pragmatic orientation, with career choices tending to meet immediate personal needs (Kim et al., 2024). This pragmatic trend underscores the importance of aligning personal values with career trajectories, as such alignment can stimulate sustained motivation and career engagement. Career values are commonly conceptualized across three core dimensions: prestige/status, security/maintenance, and growth/development. Prestige/status reflects the pursuit of social recognition and professional respect; security/maintenance emphasizes job stability, safety, and predictability; and growth/development highlights opportunities for skill enhancement, personal advancement, and self-fulfillment. Each dimension exerts a unique influence on shaping career-related attitudes and behaviors. For instance, students who prioritize growth and development are more likely to actively engage in learning and career planning, thereby enhancing their employability (Ling & Fang, 1999). Achievement Goal Theory posits that students with higher self-efficacy are more inclined to set mastery-oriented goals (Nicholls, 1984), which, in turn, promote employability development and yield intrinsic satisfaction (Heintalu et al., 2025). Similarly, Holland’s vocational interest theory suggests that individuals are drawn to careers that align with their skills and personalities, enabling them to maximize success and realize self-worth (Holland, 1997). When students’ career values are highly aligned with the external employment environment, they are more likely to receive positive reinforcement, such as recognition for job performance and opportunities for advancement, which strengthens occupational self-efficacy and fosters favorable perceptions of employability (Tan et al., 2025). Empirical findings further demonstrate that career values significantly predict employability. For example, McKenzie and Bennett (2022) found that strong career values enhance students’ professional identity, motivating proactive efforts to improve employability; Quinlan and Renninger (2022) similarly emphasized the predictive role of vocational interests in shaping employability outcomes.

Learning engagement is defined as a positive psychological state closely associated with academic and work-related activities (Schaufeli et al., 2002). From the perspective of ecological systems theory, microsystems represent the core environments that shape individual development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). For university students—who are positioned at the intersection of school and society—both academic and social environments play a critical role in influencing learning engagement (Skinner et al., 2022). For example, peer interactions can shape students’ motivational and emotional profiles, and these positive psychological experiences significantly affect the degree to which students engage in learning (Bond & Bedenlier, 2019). Self-efficacy has also been shown to positively predict learning engagement: students with a confident and positive outlook on their academic abilities derive greater enjoyment from the learning process and invest more effort and perseverance (Woreta et al., 2025). Conversely, negative emotional states can undermine engagement. Adolescents experiencing negative emotions often exhaust psychological resources, leading to learning burnout and diminished engagement (Barratt & Duran, 2021). According to student involvement theory, the development of personal competence depends on the extent and quality of academic engagement (Astin, 1984). Students who demonstrate higher levels of academic involvement tend to develop stronger employment-related insights, display more positive psychological states when facing employment, and are more willing to devote time to acquiring specialized knowledge, thereby strengthening their employability (Mooney, 2023).

Chain mediation of career values and learning engagement

Self-determination theory posits that when individuals’ behaviors are consistent with their values, motivation is more likely to be internalized and transformed into autonomous motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Clear and positive career values not only provide students with well-defined learning goals and intrinsic motivation but also promote higher levels of concentration and sustained engagement in learning activities through self-identification (Lu et al., 2025). Students with a strong sense of professional identity are therefore more likely to exhibit elevated learning engagement, driven by a heightened sense of belonging and responsibility toward their chosen field (Yang et al., 2025). Accordingly, students with higher psychological capital are more likely to develop clear and positive career values, which subsequently enhance learning engagement and, ultimately, foster stronger employability.

According to data from the Ministry of Education of China, the number of college and university graduates in 2024 is projected to reach 11.79 million, marking an increase of 210,000 compared with the previous year. However, in contrast to the growing number of job seekers, the job market—constrained by an economic slowdown—has failed to expand sufficiently to meet rising employment demand. This imbalance has intensified employment pressures on university graduates, with the “difficulty in securing employment” emerging as a critical social concern (Zhang et al., 2025a). Enhancing students’ employability has therefore become a key strategy to alleviate these employment challenges.

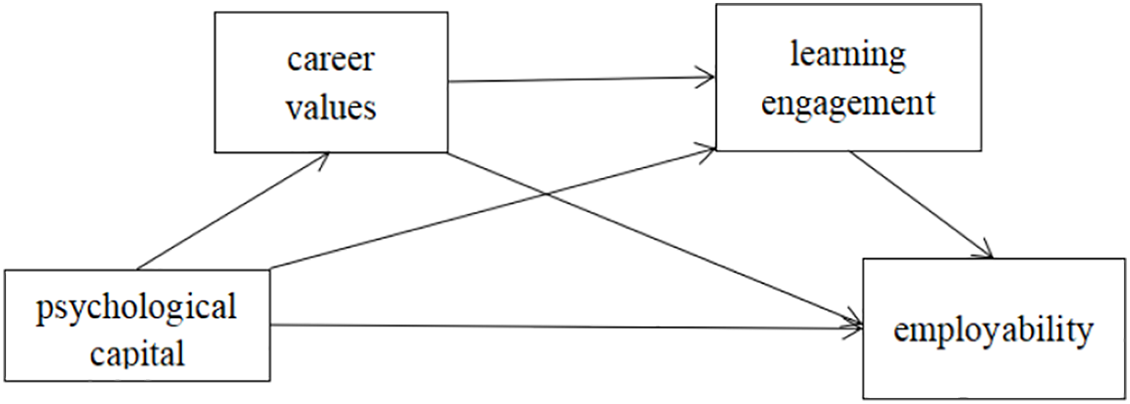

The present study seeks to examine the relationship between psychological capital and employability, while exploring the mediating roles of career values and learning engagement in this process. Based on the conceptual model presented in Figure 1, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H1: Psychological capital positively predicts tertiary students’ employability.

H2: Career values mediate the relationship between psychological capital and employability.

H3: Learning engagement mediates the relationship between psychological capital and employability.

H4: Career values and learning engagement jointly exert a chain mediating effect on the relationship between psychological capital and employability.

Figure 1: The theoretical model of the impact mechanism of psychological capital on the employability among tertiary students

A total of 5434 students participated in this study, including 1930 males and 3504 females. Among them, 1389 were freshmen, 431 sophomores, 1691 juniors, 176 seniors, and 1747 graduate students. The participants’ mean age was 23.84 years (SD = 2.55).

Psychological capital questionnaire

Psychological capital was assessed using the Psychological Capital Questionnaire-24 (PCQ-24), developed by Luthans et al. and translated into Chinese by Chaoping Li (Luthans et al., 2007). The PCQ-24 comprises 24 items across four dimensions: self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). Higher total scores indicate higher levels of psychological capital. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Career values were measured using the Professional Values Questionnaire (PVQ) developed by Wenshuan Ling and colleagues (Ling & Fang, 1999). The PVQ contains 22 items divided into three dimensions: prestige, health/security, and self-development. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “least important” to 5 = “most important”), with higher scores reflecting more positive career values. Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.96.

Although widely recognized international instruments such as the Career Values Scale (CVS) and the Work Values Inventory (WVI) have been frequently used in prior research, the PVQ was selected for this study due to its stronger cultural relevance and contextual suitability. CVS and WVI were originally developed in Western contexts, and some of their dimensions (e.g., “power and status,” “achievement motivation”) may be interpreted differently by Chinese students, potentially introducing cultural bias. In addition, the abstract wording of those instruments may reduce comprehension and response accuracy in non-Western populations. In contrast, the PVQ was specifically designed for Chinese university students, incorporating constructs and language closely aligned with their career development realities, and has demonstrated strong psychometric validity in prior Chinese samples. Therefore, the PVQ was deemed most appropriate for this study, enhancing both validity and interpretability of the findings.

Learning engagement was assessed with the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale–Student (UWES-S) developed by Schaufeli et al. and revised into Chinese by Laitan Fang et al. (Fang et al., 2008). The UWES-S comprises 17 items grouped into three dimensions: vigor, dedication, and absorption. Students rated items on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “never” to 7 = “always”). Higher total scores indicate stronger learning engagement. Cronbach’s α was 0.96 in this study.

Employability was measured using the Employability Self-Assessment Scale (ESAS) developed by Zhaohong He and colleagues (He & Lyu, 2012). The ESAS includes 26 items across five dimensions: self-development, interpersonal communication, employment confidence, practical ability, and adaptability. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). Higher total scores indicate greater employability. Cronbach’s α was 0.96 in this study.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan Wudong Hospital (approval number: 2024-wdyyll-033). All participants provided informed consent prior to participation and were assured of their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Data were collected via an anonymous online survey, which students voluntarily completed on their smartphones. The survey required approximately 20 min to complete and included measures of psychological capital, career values, learning engagement, employability, as well as demographic information such as gender, age, and academic year. A pilot test was conducted with 60 students from one sampled university to ensure the clarity and cultural appropriateness of the items before the formal data collection.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.0. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the study variables were first computed. To assess potential common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was performed. Subsequently, the chain mediation model was tested using Model 6 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018), with psychological capital as the independent variable, employability as the dependent variable, and career values and learning engagement as sequential mediators. A bias-corrected bootstrap procedure with 5000 resamples was employed to estimate the indirect effects, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were generated. Mediation was considered significant when the CI did not include zero.

To examine potential common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The results indicated that seven factors had eigenvalues greater than 1, with the first factor explaining 32.46% of the variance—below the critical threshold of 40%. Thus, common method bias was not a serious concern in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Correlation analyses revealed significant positive associations among psychological capital, career values, learning engagement, and employability. In addition, gender was significantly correlated with career values and learning engagement, while grade level, place of origin, only-child status, and cadre experience were significantly correlated with psychological capital and employability. Accordingly, these demographic variables were controlled for in the subsequent analyses.

Following standard procedures for mediation analysis, all variables were standardized, with psychological capital specified as the independent variable, employability as the dependent variable, and career values and learning engagement as mediators. Based on the correlation results (Table 1), gender, grade level, place of origin, only-child status, and cadre experience were included as control variables. Model 6 of the PROCESS macro was used to test the chain mediation effect, and the results are reported in Table 2.

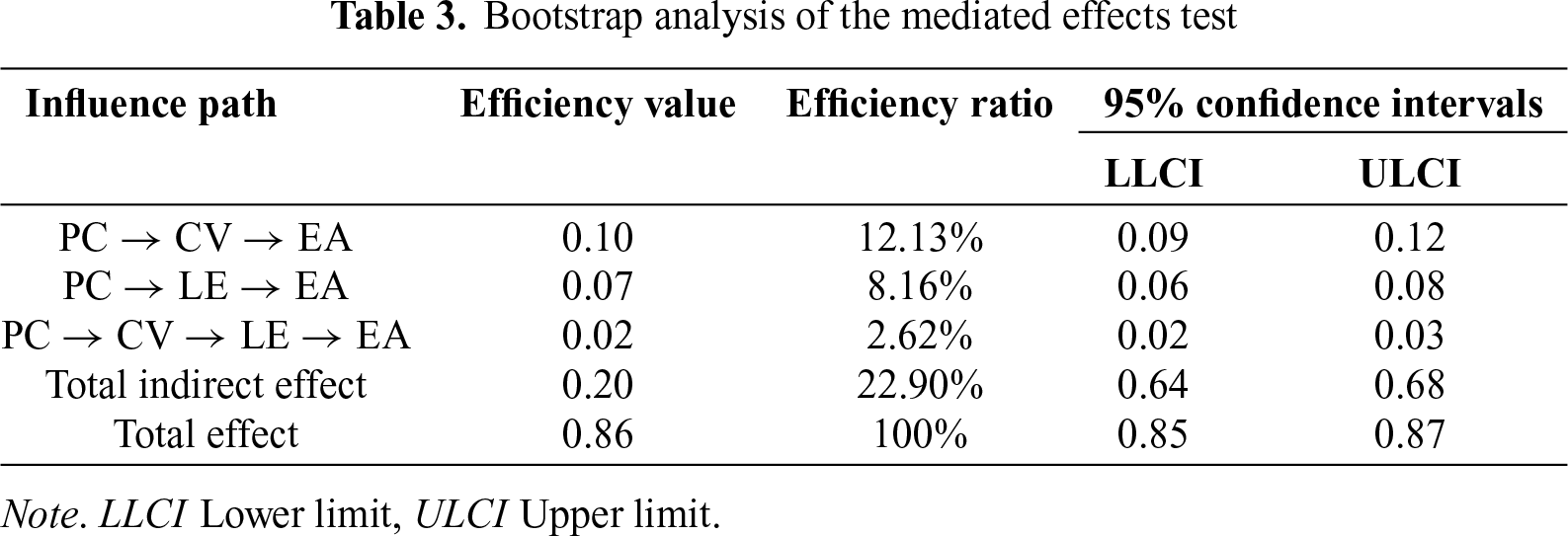

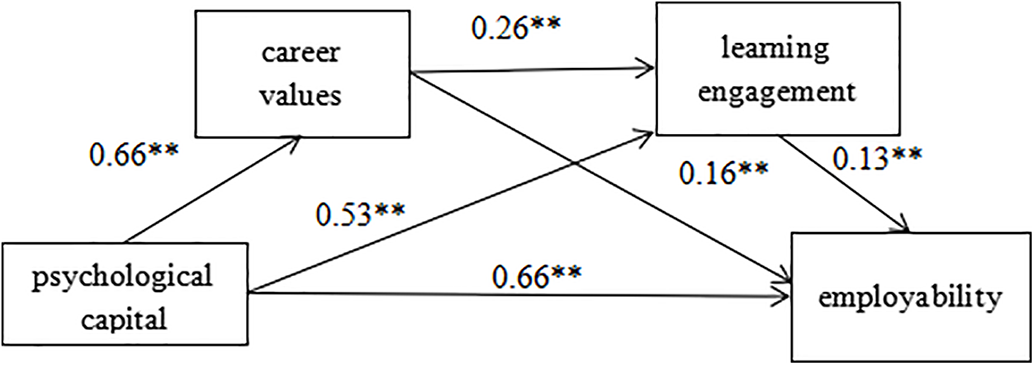

A bias-corrected bootstrap analysis with 5000 resamples was conducted, and the estimated indirect effects with corresponding 95% CIs for the three mediation pathways are shown in Table 3. Results indicated that the 95% CIs for all three indirect paths did not include zero, demonstrating statistically significant mediation effects. Specifically, career values and learning engagement jointly mediated the relationship between psychological capital and employability. The total indirect effect was 0.20, accounting for 22.90% of the total effect. The proportions of the indirect effects for the three pathways were 12.13%, 8.16%, and 2.62%, respectively. The overall chain mediation model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Chain mediation model diagram of career values, learning engagement between psychological capital and employability. Note. **p < 0.01.

This study findings confirmed that psychological capital is positively associated with university students’ employability, consistent with previous findings (Agnihotri et al., 2023). Psychological capital—comprising self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism (Luthans et al., 2007)—represents a set of internal psychological resources that enhance individuals’ capacity to cope with challenges and pursue goals. Each component contributes uniquely to employability. Self-efficacy strengthens students’ confidence in performing career-related tasks such as job searching, networking, and interview preparation. Hope fosters goal-directed motivation and planning, enabling students to establish clear career pathways and adapt strategies in uncertain contexts. Resilience facilitates recovery from setbacks such as job rejections or academic failures, sustaining long-term career engagement. Optimism encourages students to interpret career challenges as opportunities rather than threats, thereby promoting proactive behaviors that support professional growth. Person-environment fit theory provides a useful framework for understanding this mechanism, as it emphasizes that congruence between individual attributes and environmental demands facilitates adaptation and performance (Edwards, 2008). Psychological capital thus functions as a personal resource that enhances students’ capacity to explore opportunities, adapt to challenges, and strengthen career-related competencies (Zhou et al., 2024). Students with higher psychological capital generally display more positive and adaptive attitudes, better workplace adjustment, and greater professional competitiveness, while those with low psychological capital are more vulnerable to negative emotions and self-doubt, hindering their employability (Ayala Calvo & Manzano García, 2021). These findings underscore the importance of psychological capital as both a protective factor in uncertain labor markets and a proactive force driving long-term career success. Practically, universities and career service providers should regard psychological capital as a foundational competency and integrate its cultivation into employability-enhancing interventions such as resilience training, strengths-based coaching, and optimism-focused counseling.

Second, this study verified the mediating role of career values in the relationship between psychological capital and employability. Career Construction Theory (CCT) emphasizes that individuals’ career development behaviors are guided by their career values, and that psychological capital shapes these values by influencing how students interpret careers and construct meaning (Brown & Lent, 2020). Ling & Fang (1999) identified three dimensions of career values: development, maintenance, and prestige/status. Students with higher psychological capital are more likely to prioritize growth and development, thereby investing in learning, skills acquisition, and career planning. The maintenance dimension highlights the pursuit of job stability, fair compensation, and long-term security; psychological capital supports rational planning and stress management that facilitate informed career decisions. The prestige/status dimension reflects aspirations for recognition and respect, which psychological capital helps students pursue with greater persistence and optimism. From the perspective of person-vocation fit (Holland, 1997; Kristof-Brown et al., 2005), career values influence how students evaluate career options and engage in career-related behaviors. This theoretical lens strengthens the explanatory power of career values as a mediating mechanism. Empirical evidence aligns with this interpretation: Zhang et al. (2025b) demonstrated that psychological capital enhances career values through improved self-efficacy and positive affect, which subsequently foster adaptive career behaviors. Accordingly, strengthening students’ psychological capital can cultivate positive career values—such as growth orientation, social contribution, and alignment with personal goals—that encourage more adaptive career choices and, ultimately, enhance employability.

Third, the results indicated that learning engagement mediates the relationship between psychological capital and employability. Conservation of Resources theory (Hobfoll, 2002) explains this mechanism: as a key psychological resource, psychological capital promotes the accumulation and preservation of other valuable resources, including engagement. Individuals with high psychological capital tend to invest more actively in academic research, coursework, and skill-building activities to expand their cognitive and social resources, thereby enhancing both self-efficacy and employability (Baluku et al., 2021; Schönfeld & Mesurado, 2025). Moreover, prior studies suggest that the predictive effect of psychological capital on learning engagement is particularly pronounced in contexts with strong social support (Barratt & Duran, 2021). Thus, psychological capital functions as a catalyst for sustained engagement in learning, which in turn fosters employability development.

Fourth, this study confirmed the chain mediating role of career values and learning engagement. Psychological capital enhances optimism and confidence, which shape the development of positive career values and, in turn, motivate students to devote more energy to learning and skill acquisition (Xie et al., 2023; Eldor et al., 2020). Learning engagement thereby serves as a bridging mechanism: career values translate psychological capital into active participation in academic and career preparation behaviors, which ultimately reinforce employability (Mooney, 2023). This chain mediation pathway is consistent with the assumptions of the Context-Process-Outcome Model (Roeser et al., 1996), which suggests that external resources (e.g., psychological capital) affect individual competence development by shaping internal values and engagement behaviors.

Finally, Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences. As both psychological capital and employability evolve over time, future longitudinal or cross-lagged designs should be employed to capture dynamic relationships. Second, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires may introduce social desirability or self-perception biases. Future studies should adopt multi-source data collection methods, including interviews, peer or teacher ratings, and behavioral assessments, to improve objectivity and reliability. Third, while this study focused on individual-level psychological mechanisms, contextual factors such as institutional support, family environment, and peer networks may also play critical roles. For example, access to career counseling services, scholarships, mentorship, and internships can bolster students’ confidence and skills, while emotional support from families and alumni networks may buffer employment-related stress. Future research should integrate both individual and environmental factors to develop a more comprehensive understanding of employability formation.

Grounded in Resource-Based Theory, this study constructed a chain mediation model to examine the roles of career values and learning engagement in the relationship between psychological capital and university students’ employability. The findings demonstrated that psychological capital significantly and positively predicts employability, with career values and learning engagement serving as key mediating mechanisms. Specifically, psychological capital shapes students’ career values, which subsequently enhance their learning engagement, ultimately fostering the development of employability. The establishment of this model enriches the contextual application of Resource-Based Theory and broadens understanding of the psychological mechanisms that influence employability in higher education. From a practical perspective, the results provide valuable implications for the design and implementation of employability development programs and career guidance services in universities. By integrating psychological capital cultivation with career values clarification and engagement-enhancing interventions, institutions can more effectively support students in building sustainable career competencies. Future research should further test the cross-cultural applicability of this model and adopt longitudinal designs to capture the dynamic evolution of psychological capital, career values, learning engagement, and employability across students’ academic and professional trajectories.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (OpenAI) for language polishing support. All substantive ideas, analyses, and interpretations are solely those of the authors.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Hubei Provincial Department of Education 2024 Annual Provincial Education Science Planning Project (Grant No. 2024ZX021), and Provincial Teaching and Research Project of Hubei Province Colleges and Universities (Grant No. 2023298).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xianglian Yu, Yunbo Shen; data collection: Yunbo Shen; analysis and interpretation of results: Yunbo Shen, Jie Wu; draft manuscript preparation: Yunbo Shen, Jie Wu; supervision: Xianglian Yu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Xianglian Yu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Wuhan Wudong Hospital (approval number: 2024-wdyyll-033). This study involved human participants. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation in the study, in accordance with ethical guidelines and institutional review board (IRB) requirements. All procedures adhered to the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Agnihotri, S., Shiva, A., & Khan, F. N. (2023). Investigating forms of graduate capital and their relationship to perceived employability: An application of PLS predict and IPMA. Higher Education, Skills and Work-based Learning, 13(1), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-07-2022-0146 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ashriyana, S. R., & Lestari, K. A. (2023). Employability of students in vocational secondary school: Role of psychological capital and student-parent career congruences. Heliyon, 9(2), e13214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of Tertiary Student Personnel, 25(4), 297–308. [Google Scholar]

Ayala Calvo, J. C., & Manzano García, G. (2021). The influence of psychological capital on graduates’ perception of employability: The mediating role of employability skills. higher Education Research and Development, 40(2), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1738350 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baluku, M. M., Mugabi, E. N., Nansamba, J., Matagi, L., Onderi, P., & Otto, K. (2021). Psychological capital and career outcomes among final year university students: The mediating role of career engagement and perceived employability. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 6(1), 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-020-00040-w [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Barratt, J. M., & Duran, F. (2021). Does psychological capital and social support impact engagement and burnout in online distance learning students? The Internet and Higher Education, 51(3), 100821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2021.100821 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bond, M., & Bedenlier, S. (2019). Facilitating student engagement through educational technology: Towards a conceptual framework. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2019(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.528 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development experiments by nature and desing. Children & Youth Services Review, 2(4), 433–438. [Google Scholar]

Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (2020). Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781394258994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Caballero, G., Álvarez-González, P., & López-Miguens, M. J. (2020). How to promote the employability capital of university students? Developing and validating scales. Studies in Higher Education, 45(12), 2634–2652. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1807494 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dai, K., & Pham, T. (2024). Graduate employability and international education: An exploration of foreign students’ experiences in China. Higher Education Research & Development, 43(6), 1227–1242. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2024.2325155 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. In: Perspectives in social psychology. New York, NY, USA: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Edwards, J. R. (2008). Person-environment fit in organizations: An assessment of theoretical progress. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 167–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520802211503 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eldor, L., Westring, A. F., & Friedman, S. D. (2020). The indirect effect of holistic career values on work engagement: A longitudinal study spanning two decades. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 12(1), 144–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fang, L. T., Shi, K., & Zhang, F. H. (2008). Research on reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Student. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(6), 618–620. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Harari, M. B., McCombs, K., & Wiernik, B. M. (2021). Movement Capital, RAW model, or circumstances? A meta-analysis of perceived employability predictors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 131, 103657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103657 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. A regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

He, Z. H., & Lyu, Z. H. (2012). Establishing a self-assessment scale of tertiary students’ employability. Higher Education Forum, (11), 123–126. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-9719.2012.11.036 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Heintalu, K., Saks, K., Edisherashvili, N., & Dekker, I. (2025). The conceptualisation of goal setting and goal orientation in higher education: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 48(3), 100709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2025.100709 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.6.4.307 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory ofpersonalities and work environments. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

Huang, Z., Ismail, I. A., Ghazali, A. H. A., D’Silva, J. L., Abdullah, H. & Zhang, Z. (2025). Uncovering a suppressor effect in the relationship between psychological capital and employment expectations: A chain mediation model among vocational undergraduates. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1461983. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1461983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kim, S., Creed, P. A., & Hood, M. (2024). Protean career processes in young adults: Relationships with perceived future employability, educational performance, and commitment. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 24(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-023-09584-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individual’s fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kwon, J. E. (2019). Work volition and career adaptability as predictors of employability: Examining a moderated mediating process. Sustainability, 11(24), 7089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11247089 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ling, W. Q., & Fang, L. L. (1999). Research on the career values of Chinese tertiary students. Acta Psychologica Sinica, (3), 342–348. (In Chinese). https://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/Y1999/V31/I3/342. [Google Scholar]

Locke, W., Harvey, L., & Morey, A. (2002). Enhancing employability, recognising diversity: Making links between higher education and the world of work. London, UK: Universities UK. [Google Scholar]

Lu, G. F., Luo, Y., & Huang, M. Q. (2025). The impact of career calling on learning engagement: The role of professional identity and need for achievement in medical students. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 238. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-06809-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572. [Google Scholar]

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Li, W. (2005). The psychological capital of Chinese Workers: exploring the relationship with performance. Management and Organization Review, 1(2), 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2005.00011.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mazalin, K., & i Parmač Kovačić, M. (2015). Determinants of higher education students’ self-perceived employability. Društvena Istraživanja, 24(4), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2005.00011.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

McKenzie, S., & Bennett, D. (2022). Understanding the career interests of Information Technology (IT) students: A focus on choice of major and career aspirations. Education and Information Technologies, 27(9), 12839–12853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11141-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mooney, R. (2023). Dark Triad traits, engagement with learning, and perceptions of employability in undergraduate students. Industry & Higher Education, 37(4), 524–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/09504222221140829 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91(3), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.91.3.328 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Quinlan, K. M., & Renninger, K. A. (2022). Rethinking employability: How students build on interest in a subject to plan a career. Higher Education, 84(4), 863–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00804-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Roeser, R. W., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. C. (1996). Perceptions of the school psychological environment and early adolescents’ psychological and behavioral functioning in school: The mediating role of goals and belonging. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88(3), 408–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.88.3.408 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scandurra, R., Kelly, D., Fusaro, S., Cefalo, R., & Hermannsson, K. (2023). Do employability programmes in higher education improve skills and labour market outcomes? A systematic review of academic literature. Studies in Higher Education, 49(8), 1381–1396. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2265425 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 464–481. [Google Scholar]

Schönfeld, F. S., & Mesurado, B. (2025). Basic psychological needs and psychological capital as predictors of academic engagement in students. Research in Human Development, 6(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2025.2524295 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schwartz, S. H. (1999). A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Applied Psychology, 48(1), 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1999.tb00047.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Skinner, E. A., Rickert, N. P., Vollet, J. W., & Kindermann, T. A. (2022). The complex social ecology of academic development: A bioecological framework and illustration examining the collective effects of parents. Teachers Educational Psychologist, 57(2), 87–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2038603 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tan, J., Li, J., & Yi, X. (2025). How can general self-efficacy facilitate undergraduates’ employability? A multiple mediation model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(4), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15040514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tung, D., & Huong, B. T. T. (2023). The role of social self-efficacy and psychological capital in IT graduates’ employability and subjective career success. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2204630. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2204630 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050207 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Woreta, G. T., Zewude, G. T., & Józsa, K. (2025). The mediating role of self-efficacy and outcome expectations in the relationship between peer context and academic engagement: A social cognitive theory perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15050681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xie, J., Luo, X., Zhou, Y., Zhang, C., Li, L., et al. (2023). Relationships between depression, self-efficacy, and professional values among Chinese oncology nurses: A multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 22(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01287-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yang, L., Wang, Y., Niu, Z., Ren, M., & Wang, L. (2025). Professional identity and learning engagement: Chain mediating effect among Chinese preservice teachers. Social Behavior and Personality, 53(4), e13821. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.13821 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, L. Y., Liu, Q. Y., & Liu, Y. (2025a). tertiary students’ career exploration experience and career anxiety: The role of objective employment pressure and self-concept clarity. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology, 33(3), 476–480. (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2025.03.031 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, X., Shen, Y., Xu, J., & Cui, G. (2025b). How does career-related parental support benefit career adaptability of medical imaging technology students in Asia-Pacific LMICs? The roles of psychological capital and career values. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1508926. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1508926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, L., Wider, W., Fauzi, M. A., Jiang, L., Tanucan, J. C. M., & Naces Udang, L. (2024). Psychological capital research in HEIs: Bibliometric analysis of current and future trends. Heliyon, 10(4), e26607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhou, W., Feng, Y., & Jin, Q. (2024). How psychological capital impacts career growth of university students? the role of academic major choice. Journal of Career Development, 51(4), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/08948453241253594 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools