Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The dynamics of social and psychological capital conversion in career adaptability: A network analysis

Department of Sociology, Changchun University of Science and Technology, Changchun, 130000, China

* Corresponding Author: Zhijun Liu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 575-586. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.067476

Received 05 May 2025; Accepted 02 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study examined the relationships among social support, career decision-making self-efficacy, goal orientation, and career adaptability, highlighting the bridging roles of career decision-making self-efficacy and goal orientation. A total of 1433 Chinese university students (female = 70.7%; urban = 55.3%, mean age = 19.73 years, SD = 1.60 years) completed validated measures of career adaptability, social support, career decision-making self-efficacy, and goal orientation. Network analysis revealed that social support was associated with higher career adaptability indirectly through career decision-making self-efficacy and goal orientation, which function as key bridging mechanisms. Moreover, urban college students demonstrated greater effectiveness in utilizing career decision-making self-efficacy and goal orientation to convert social capital compared to their rural counterparts. These findings extend career capital theory by elucidating the central mediating role of psychological capital in transforming social resources into adaptive career outcomes. The results underscore the importance of tailored career counseling interventions that integrate social and psychological assets to enhance student career development.Keywords

Students possess various career resources, which can help them navigate the challenges of entering the labor market (Ngoma & Dithan Ntale, 2016). Among these, the impact of social capital and psychological capital on career development has been widely acknowledged (Gheyassi & Alambeigi, 2024; Xu et al., 2024). Social capital refers to resources derived from enduring social networks that individuals perceive as accessible and usable (Bourdieu, 2012). Psychological capital refers to an individual’s positive psychological resources, including efficacy, hope, optimism, and resilience (Luthans et al., 2007). Career adaptability refers to an individual’s capacity to cope with changes in career roles and maintain balance (Chen et al., 2023; Haenggli & Hirschi, 2020). The relationships among social and psychological capital in students’ career adaptability is little known in the context of developing country contexts. We aimed to address this gap in the literature in the Chinese context.

Social and psychological capital in careers

Social capital is a crucial form of capital, encompassing resources derived from social relationships and networks. It reflects an individual’s ability to build and leverage personal connections as relational resources (Portes, 1998). As a component of career capital, social capital serves as a vital resource that facilitates career growth and advancement. When necessary, it can be leveraged to enhance an individual’s cognitive abilities and self-efficacy, thereby enabling the effective fulfillment of career roles (Zhang & Huang, 2021). Moreover, it helps individuals access more information and opportunities (Zhang et al., 2010) and serves as a vital resource during career transitions (Fugate et al., 2004). College graduates transitioning from school to the workforce who possess higher levels of social capital generally experience better career adaptation (Sou et al., 2022).

Psychological capital refers to a positive psychological state developed through an individual’s growth and life experiences, encompassing key components such as self-efficacy and goal orientation (Fathi et al., 2023; Sun, 2025). It is a distinctive and measurable psychological resource that enables individuals to sustain a strong sense of internal control while pursuing their goals (Dóci et al., 2023). It enhances competitive advantage (Luthans et al., 2005) and facilitates career development (Peng & Chen, 2023). To embrace growth and change, individuals need to cultivate psychological capital, which enhances adaptability and supports career development and success (Lupşa et al., 2020).

Notably, social capital and psychological capital are considered crucial for career adaptability, as they involve skills such as resource integration and coping with challenges—abilities that extend beyond the traditional scope of human capital. In l’contrast, social and psychological capitals are more strongly associated with higher employability than human capital alone (Direnzo et al., 2015).

Social support, a core component of social capital, refers to the psychological or physical assistance provided by one’s social network (Sneed & Cohen, 2014). It plays a critical role in reducing career-related stress and enhancing self-regulation skills (Creed et al., 2009), which, in turn, positively impacts career planning and alleviates career anxiety (Park et al., 2022). Social support helps individuals overcome setbacks, build resilience, and reduce the negative effects of career stress (Glozah & Pevalin, 2014). Existing literature suggests that social support affects individuals’ career adaptability, with those who receive positive support tending to adapt better to their careers (Dewani & Nuzulia, 2024; Hou et al., 2019). It also supports career planning, decision-making, and managing professional challenges, thereby enhancing confidence in their career choices (Septyven & Wijono, 2024). It is noteworthy that among the various forms of social support, support from family exerts a significant influence on an individual’s career development. Family serves as the primary and most accessible source of information, shaping individuals’ interests and facilitating the development of skills relevant to specific careers. Moreover, support from family in the career choice process is manifested through the provision of resources and by serving as role models or ideal figures (Zulfiani et al., 2021).

Career decision-making self-efficacy is a crucial component of psychological capital, reflecting an individual’s confidence in managing career planning and decision-making tasks (Taylor & Betz, 1983). Career decision-making self-efficacy is a key determinant of career adaptability (Xing & Rojewski, 2018), supporting career identity clarity (Savickas, 2002). Savickas et al. (2018) highlight that increasing self-efficacy enables individuals to succeed in future career development tasks, thereby further enhancing career adaptability. Previous literature indicates that career decision-making self-efficacy, as an adaptive response, plays a significant role in influencing individuals’ adaptation outcomes (Jiang et al., 2022; Savickas et al., 2018). Individuals with higher career decision-making self-efficacy are more likely to engage in career exploration and planning, as well as make deliberate efforts to pursue their career objectives (Rogers & Creed, 2011).

Goals are the targets of mental action sequences, and they provide the cognitive component that anchors hope theory (Snyder et al., 1997). Therefore, goal orientation, another essential component of psychological capital, is a resource for individuals’ goal-directed behavior (AhmadiGatab & Taheri, 2011), which provides a psychological framework for interpreting success and failure (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). In the context of career development, goal orientation is critical to career adaptability (Dweck, 1986), as it enables individuals to improve their adaptability and overcome challenging situations (Yousefi et al., 2011). Existing literature shows that university students with higher goal orientation are more likely to perceive life events (e.g., role transitions) as drivers of career development rather than obstacles, thereby promoting self-regulation and facilitating successful career adaptability (Tolentino et al., 2014).

Previous literature has demonstrated that social support, career decision-making self-efficacy, and goal orientation significantly influence career adaptability (Hou et al., 2014; Karatepe & Olugbade, 2017; Tolentino et al., 2014). However, these studies often focus on isolated relationships and have been criticized for oversimplifying the complexity of these interactions by relying on a limited number of latent variables, resulting in a constrained understanding of their underlying intricacies (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). To address this limitation, network analysis has emerged as an alternative approach.

Career adaptability comprises four dimensions: career concern, career control, career curiosity, and career confidence (Porfeli & Savickas, 2012). Effective career adaptability enables individuals to manage career development and overcome decision-making difficulties (Salim et al., 2023). It also enhances self-efficacy (Matijaš & Seršić, 2021; Pajic et al., 2018), improves job search success and employment quality (Pan et al., 2018; van der Horst et al., 2021), and contributes to greater subjective well-being (Ramos & Lopez, 2018). Furthermore, career adaptability helps mitigate the negative effects of significant career changes on adaptation effectiveness (Rudolph & Zacher, 2021). In contrast, individuals with poor career adaptability often avoid making career decisions, experience frustration when outcomes deviate from expectations, and struggle to accomplish their career goals (Salim et al., 2023; Savickas, 2013).

The Career Capital Theory offers a novel framework for addressing career adaptability challenges among individuals (Järlström et al., 2020). This theory explains individual career development through the lens of career competitive advantage. It posits that personal resources and relationships, which contribute to positive career outcomes, form part of an individual’s career capital (Inkson & Arthur, 2001). Career capital is an essential resource for individuals seeking well-matched employment. It integrates personal assets and advantages that reflect an individual’s competitiveness in the job market, thereby facilitating career outcomes and contributing to career development and well-being (Xu et al., 2022).

In the context of China’s dual economy, urban and rural individuals exhibit notable differences in career development. Research has indicated significant disparities in the diversity of social capital between university students from urban and rural backgrounds (Fung, 2015). Urban students tend to have greater access to perceived social support than their rural counterparts, which contributes to higher levels of career decision-making self-efficacy (Chen et al., 2021). Accordingly, rural students have been found to demonstrate lower levels of career adaptability compared to those from urban areas (Hou & Liu, 2021).

This study employed network analysis to examine the relationships between social support, career decision-making self-efficacy, goal orientation, and career adaptability. It tested the following hypotheses.

H1: social support, career decision-making self-efficacy, goal orientation, and career adaptability are interrelated. Moreover, career decision-making self-efficacy, and goal orientation serve as key bridging mechanisms that link social support to career adaptability.

H2: The relational network among social support, career decision-making self-efficacy, goal orientation, and career adaptability may vary between university students from urban and rural areas in China.

By employing network analysis as a comprehensive methodological approach, this study investigates how social and psychological capitals jointly facilitate the development of career adaptability, particularly within the Chinese socio-economic context. The insights derived from this analysis are intended to inform targeted interventions aimed at supporting individuals in navigating their career transitions effectively.

A random sampling method was employed to conduct an online survey of 1500 undergraduate students from four universities in northeastern China. To ensure consistency in testing conditions and minimize external interference, the survey platform was accessible only between 8:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. each day, over a two-week period.

Data quality checks were performed, resulting in the exclusion of 67 respondents (4.5%) who failed attention check items, responded too quickly (less than 2 s per item; Huang et al., 2012), or streamlining (patterns based on clicking through the survey, e.g., flat lining; DeSimone & Harms, 2018). After screening, 1433 valid responses were retained, yielding a response rate of 95.5%. The final sample comprised 1014 females (70.7%), with a mean age of 19.73 years (SD = 1.60). Of these participants, 793 (55.3%) were from urban areas and 640 (44.7%) from rural areas.

The Chinese version of the Career Adaptability Scale was adapted in this study to measure participants’ career adaptability (Hou et al., 2012). This scale consists of 24 items (e.g., “I am fully prepared for my future career”, “Thinking about what my future will be like”, “Being curious about new opportunities”) The scale uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not strong, 5 = Strongest). The higher scores indicate stronger career adaptability. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for scores from the career concern to career confidence subscales ranged from 0.840 to 0.896, and the Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.948.

The Chinese version of the Perceived Social Support Scale, developed by Zimet et al. (1988), was used to assess the extent of social support individuals perceive from various sources, including “support from family” (Sfa), “support from friends” (Sfr), and “support from others” (SO). The scale is a 12-item self-reported instrument (e.g., “My family really tries to help me”, “My friends really try to help me”, “I can talk about my problems with my family”). The items are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (ranging from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 7, “strongly agree”), with a higher score indicating a greater level of perceived social support. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the subscales from support from family to support from friends ranged from 0.914 to 0.931, while the Cronbach’s α for the total scale was 0.965.

Career decision-making self-efficacy

The Chinese version of the Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy Scale was revised by Peng and Long (2001). The scale aims to assess the effectiveness of self-efficacy expectations in understanding and resolving career decision difficulties and their correlation. It consists of 39 items (e.g., “You are capable of identifying the occupation or job that you are best suited for”, “Seek information relevant to your career or professional interests”, “Even in times of discouragement, persist in working toward your career goals”),and participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (f1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicating more career decision-making self-efficacy. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the subscales from assessment to collection ranged from 0.883 to 0.930, while the Cronbach’s α for the overall scale was 0.980.

Goal orientation was assessed using a modified version of VandeWalle’s (1997) 13-item scale, which measures three distinct orientations: learning orientation (5 items), proving orientation (4 items), and avoiding orientation (4 items). Sample items for each orientation include: for learning orientation, “For me, development of my skills is important enough to take risks”; for proving orientation, “I enjoy it when others are aware of how well I am doing”; and for avoiding orientation, “I prefer to avoid situations where I might perform poorly.” Participants rated their agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a stronger endorsement of the respective orientation. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the subscales ranged from 0.833 to 0.898, and the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the total scale was 0.933.

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Sociology at Changchun University of Science and Technology (Approval No. 20250219). Participants consented to the study. We explained to participants that they were free to discontinue the study without penalty. They were also informed that all data collected were to be used only for research purposes.

We adopted network analysis to address this gap, with its techniques providing the following advantages: (1) Unlike three-variable regression, which may not accurately estimate mediation effects (MacKinnon et al., 2000), network analysis captures all possible connections, rapidly constructing models of relationships between multiple variables. It clearly illustrates the complexity of these connections (Liang et al., 2023) and allows for the exploration of complex capital relationships, aiding researchers in identifying key factors.

(2) Network analysis also identifies and quantifies influential symptoms or factors that serve as bridging connections, revealing their co-occurrence (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). This allows for a deeper understanding of the dynamic relationships between forms of capital and how one form contributes to another.

Visualized network analysis was performed in the present study. The analysis used a graphical least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO; Friedman et al., 2008) regularization based on the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC; Chen & Chen, 2008), known as the EBIC glasso model. In the network, the centrality of nodes representing the research variables is determined by strength centrality, which is defined as the sum of the absolute weights of the edges connecting the node to all the other nodes (Valente, 2012). The greater the strength of a node, the more centrally it is positioned within the network, and its importance to the overall network increases. This can be used to emphasize the individual value of a particular node. Node centrality stability is also evaluated using the correlation stability coefficient (CS coefficient), with a recommendation that the coefficient should ideally exceed 0.5 to ensure interpretability and stability (Epskamp et al., 2018). Edge stability was estimated by calculating the 95% confidence interval using the bootstrap method (with 1000 bootstrap samples). A smaller overlap indicates higher stability.

Furthermore, to identify the key nodes that connect different factors in the network, both the one-step Bridge Expected Influence (BEI1) and two-step Bridge Expected Influence (BEI2) were separately examined. BEI1 measures the expected influence of a given node on adjacent nodes within other factors, while BEI2 not only includes the BEI1 of the given node but also considers the indirect effects that might occur through other nodes on different factors (Jones et al., 2021; Robinaugh et al., 2016). We used the 80th percentile of the Bridge Expected Influence (BEI1) as the threshold to identify key bridging nodes/factors (Jones et al., 2021; Liang et al., 2023).

Finally, the Network Comparison Test (NCT) was used to compare the network structures, global network strength, and the differences between each edge in urban and rural areas. The NCT is a two-tailed permutation test (performed 1000 times in this study), similar to the Item Differential Functioning (DIF) test, used to assess response differences between subgroups (Van Borkulo et al., 2017). The NCT evaluates three hypotheses: (1) whether the overall structure of the network is identical across subgroups; (2) whether the strength of the connections between nodes/factors remains consistent across networks from different subgroups; and (3) whether the overall strength of the network is equivalent across networks.

Network analysis was performed using R software. The packages used in the analysis, including bootnet, Network Tools, and Network Comparison Test.

Following the recommendations of relevant scholars, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess potential common method bias (Aguirre-Urreta & Hu, 2019). The unrotated principal component analysis revealed that the first factor accounted for 46.46% of the total variance. Although this exceeds the commonly cited 40% threshold, it remains below the more conservative 50% cutoff, which is considered acceptable (Aguirre-Urreta & Hu, 2019). Therefore, the results suggest that common method bias is within an acceptable range, allowing subsequent analyses to proceed with reasonable confidence.

Descriptive statistical analysis

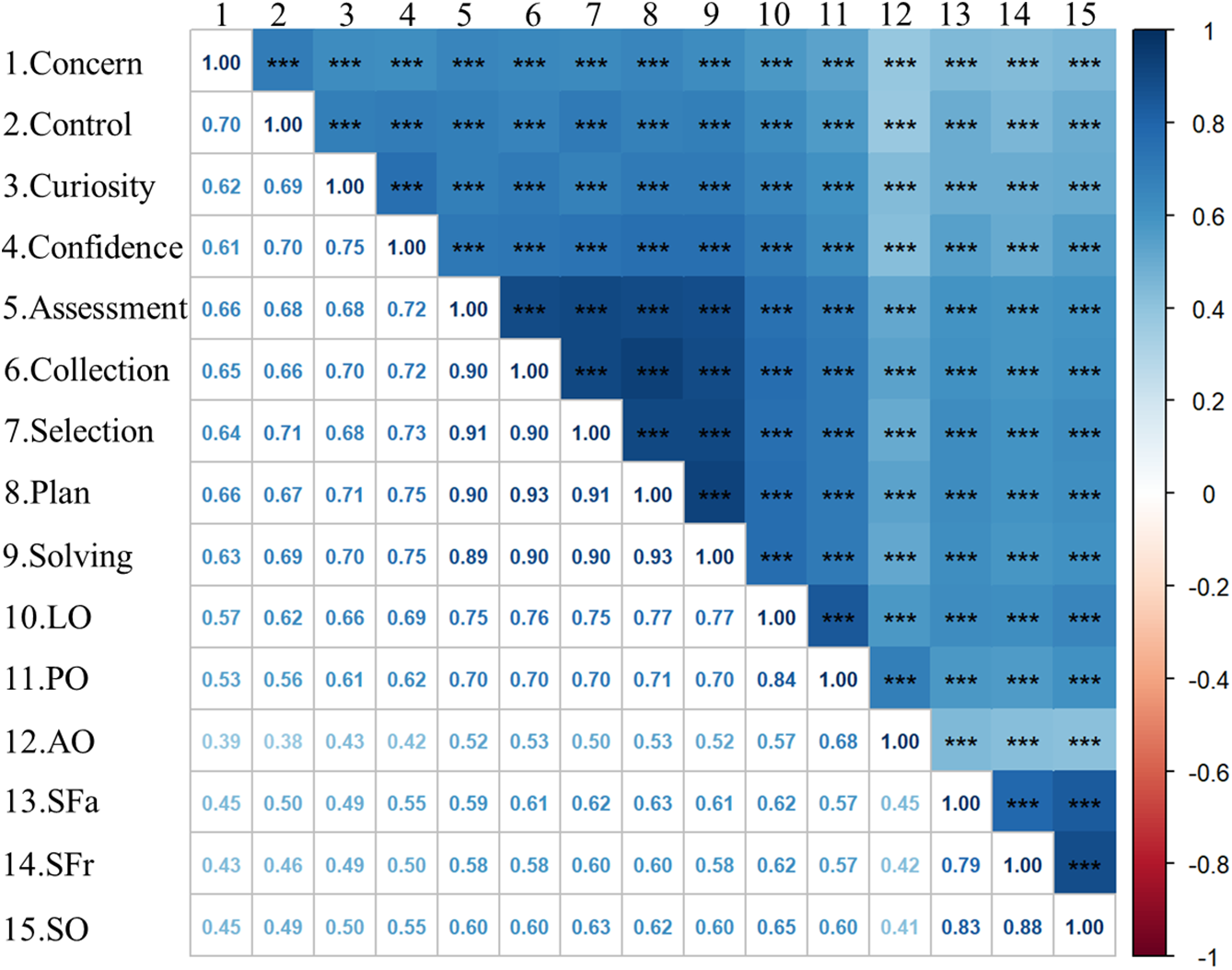

Descriptive statistical results are summarized in Figure 1. Correlation analyses revealed significant interrelations among social support, career decision-making self-efficacy, goal orientation, and career adaptability (ps < 0.001), thereby satisfying the prerequisites for mediation analysis.

Figure 1: Correlation matrix of career capital components and career adaptability. Note. LO = learning orientation; PO = proving orientation; AO = avoiding orientation; SFa = Support from Family; SFr = Support from Friends; SO = Support from Others; *** p < 0.001.

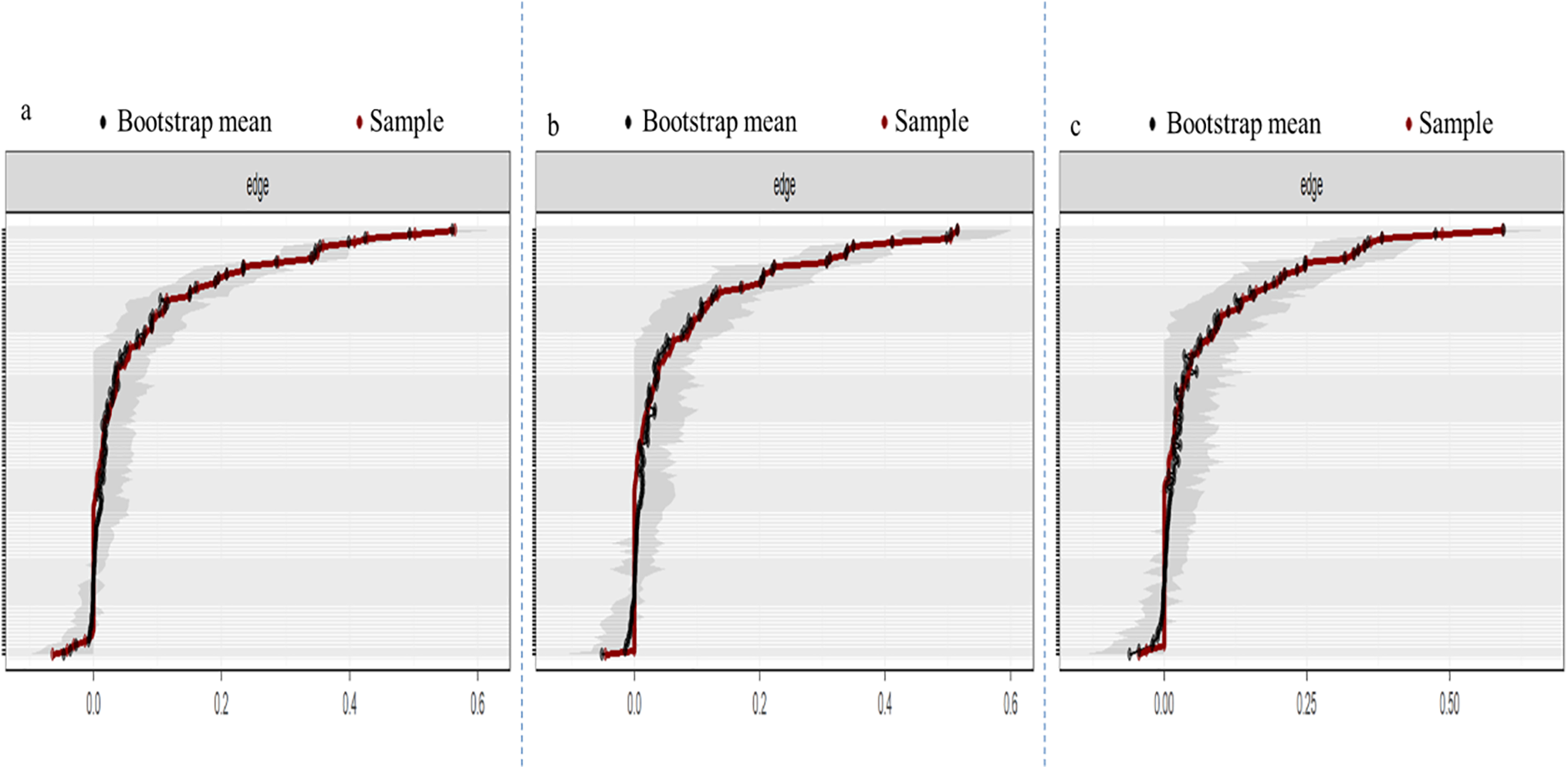

Stability test of network analysis

The results of the network analysis indicate high stability for the overall, urban, and rural networks, with satisfactory edge weight stability across all three. Centrality coefficients are also acceptable (overall network = 0.75; urban = 0.75; rural = 0.672). The confidence intervals for edge estimates are narrower for the overall and urban networks, while the rural network exhibits broader intervals. Nonetheless, the stability coefficients exceed the recommended threshold (Epskamp et al., 2018), confirming the stability of all networks. Refer to Figure 2.

Figure 2: Bootstrap confidence intervals for edge weights. Note. The red line indicates the sample value, the shaded area represents the bootstrap confidence interval, and each horizontal line denotes an edge in the network; a = overall network; b = urban network; c = rural network.

Overall network model of career capital and career adaptability

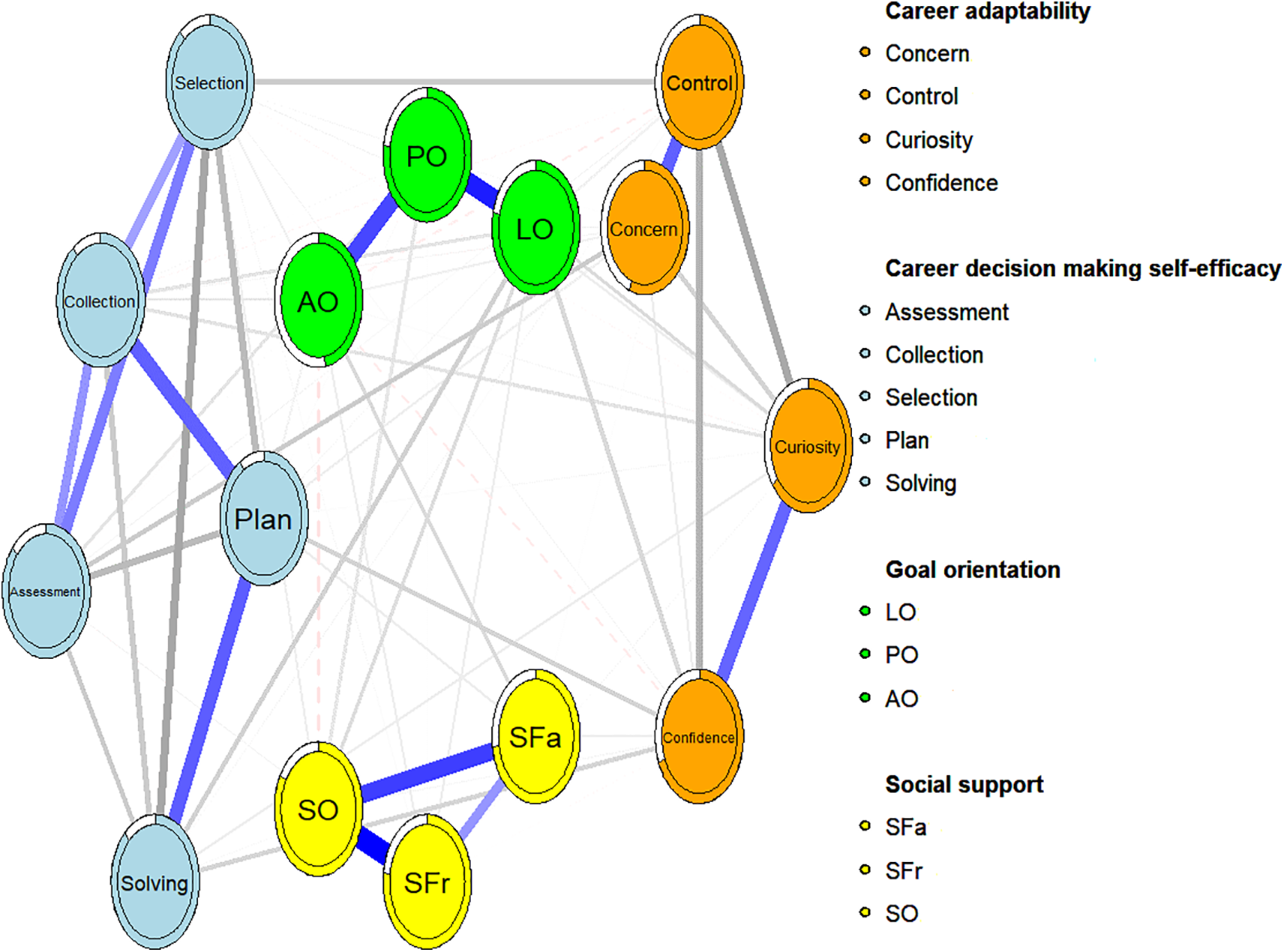

Figure 3 illustrates the network analysis of relationships among social support, career, and career adaptability (n = 1433).

Figure 3: Network model of career capital components and career adaptability. Note. Black edges represent positive correlations, blue edges indicate strong positive correlations (partial correlations > 0.2), and red dashed lines indicate negative correlations. Thicker lines represent stronger correlations, while thinner lines represent weaker correlations. This notation applies throughout.

The network analysis indicates that the ‘Plan’ node and ‘Support from Others’ (SO) are significant, with high strength centralities (Plan = 1.22; SO = 1.23). These top centrality scores suggest that these nodes play pivotal roles in connecting other elements within the network—for example, various forms of support influencing career confidence and concern through the ‘Plan’ node. The prominent centrality of this node underscores its essential bridging role in the career adaptability network, emphasizing that career decision-making self-efficacy, as a key component of psychological capital, facilitates the flow of information among different types of capital.

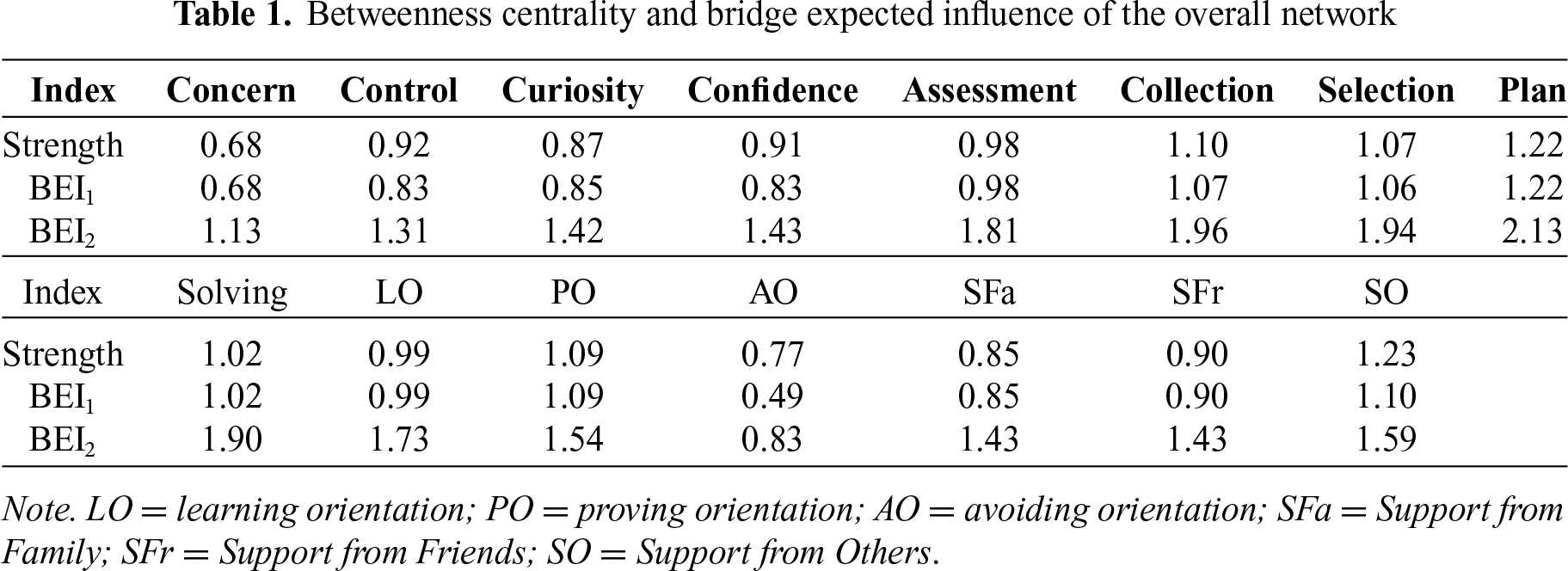

Meanwhile, Estimates from BEI1 and BEI2 indicate that the ‘Plan’ node in career decision-making self-efficacy (BEI1 = 1.22) and the ‘PO’ node in goal orientation (BEI1 = 1.09) have relatively high bridge expected influence. Similar patterns were observed for the two-step bridge expected influence, with ‘Plan’ showing the highest scores (BEI1 = 1.22; BEI2 = 2.13). These findings suggest that ‘Plan’ plays a crucial role not only in directly linking key nodes (e.g., connecting career concern and confidence) but also in mediating indirect influences among various dimensions of capital (e.g., social support, other psychological capitals). This emphasizes the central bridging function of psychological capital within the network (see Table 1).

Overall, social support, as a component of social capital, does not exert a direct influence on career adaptability but acts indirectly through psychological capital. Career decision-making self-efficacy and goal orientation, as components of psychological capital, not only directly influence an individual’s career adaptability within the network but also enhance the overall synergy of the network through their bridging effects between nodes. Notably, family support, as a key aspect of social capital, has been observed to directly influence career adaptability in specific contexts. These findings underscore the distinct but interconnected roles of psychological and social capitals within the career adaptability network. Therefore, the results support H1.

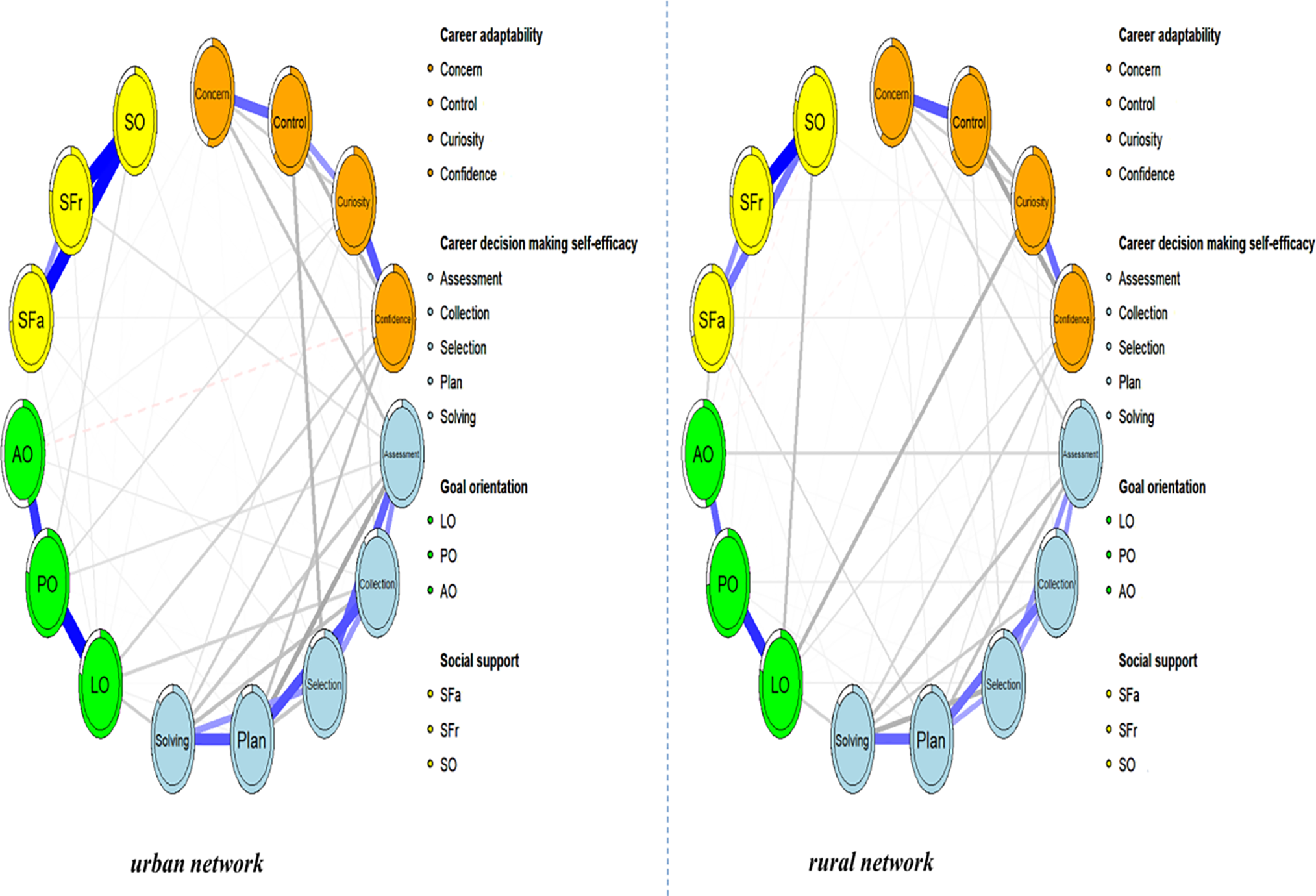

Comparison of career adaptability networks in urban and rural areas

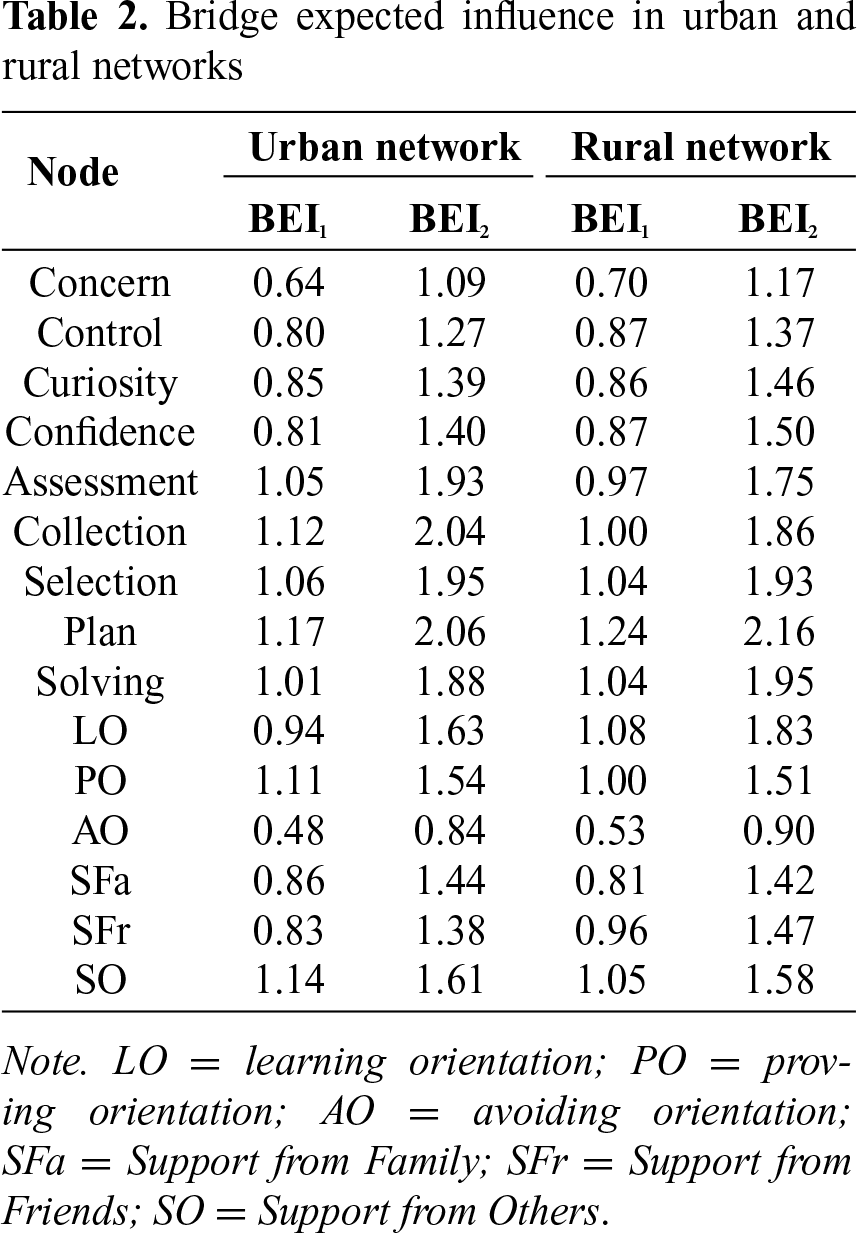

Comparison of career adaptability networks between urban and rural areas revealed significant differences in network structure and key nodes through Bridge Expected Influence (BEI) analysis (see Table 2). In the urban network (n = 793), the most crucial nodes were career decision-making self-efficacy and social support. Specifically, within the career decision-making self-efficacy, nodes such as ‘Plan’ (BEI1 = 1.17), ‘Collection’ (BEI1 = 1.12), and within social support, ‘Support from Others’ (SO; BEI1 = 1.14), exceeded the 80th percentile in BEI1. The BEI2 values further confirmed these nodes’ bridging roles, with ‘Plan’ (2.06), ‘Collection’ (2.04), and ‘Support from Others ‘ (1.61) showing high influence scores.

By contrast, the rural network (n = 640) demonstrated a different pattern, with goal orientation notably more prominent. Key nodes included career decision-making self-efficacy, goal orientation, and social support. Nodes such as ‘Plan’ (BEI1 = 1.24), ‘Learning Orientation’ (BEI1 = 1.08), and ‘Support from Others’ (BEI1 = 1.05) exceeded the 80th percentile. Interestingly, goal orientation played a stronger bridging role in the rural network than in the urban one.

Network comparison test (NCT) revealed a significant difference in network structure between urban and rural samples (M = 0.19, p < 0.05). Conversely, no significant difference was observed in overall network strength (S = 0.1284, urban = 7.04, rural = 7.17, p = 0.54). The edge invariance test was not performed to prevent increased Type I error, as the NCT indicated structural differences but suggested similar global network strength (Van Borkulo et al., 2017). This suggests that despite similar global network strength, the underlying mechanisms and roles of key nodes differ across urban and rural college students.

Overall, urban students appear to rely primarily on career decision-making self-efficacy, whereas rural students utilize both career decision-making self-efficacy and goal orientation to translate social capital into career capital (see Figure 4). Therefore, the results support H2.

Figure 4: Network analysis models of college students in urban and rural settings

First, in contrast to prior studies that emphasize the direct effects of isolated capital dimensions (Hou et al., 2019), our network analysis demonstrates that social capital primarily influences career adaptability indirectly through psychological capital. That is, social capital, as a distal resource, needs to be transformed into proximal psychological resources to enhance adaptive capacities. Although social capital is considered a distal form of capital, it plays an essential and influential role in the development of individuals’ career adaptability. When facing potential pressures and challenges in the future, individuals are likely to proactively build and maintain social relationships, which serve as a key resource to enhance their adaptability (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Social capital is, therefore, an essential resource for career success. Individuals with greater social capital are more likely to engage in proactive career behaviors, which are crucial for achieving career success (Zulfiani et al., 2021).

Second, another key finding of this study is that support from family social capital, can directly influence individuals’ career adaptability in certain contexts. This suggests that, while social capital typically affects career adaptability through indirect pathways, it may have a direct impact on career adaptability in specific situations. Individuals who receive strong support from family tend to exhibit higher levels of career adaptability (Andini et al., 2025). Support from family addresses individuals’ intrinsic psychological needs for relatedness, autonomy, and competence (Deci & Ryan, 2000). On the one hand, during the career exploration stage, family members can facilitate individuals’ career readiness by guiding them through key developmental tasks such as educational and vocational decision-making (Guan et al., 2018). On the other hand, when individuals face career-related challenges, reliable support from family offers timely comfort, encouragement, care, and practical advice, motivating them to adopt a positive psychological mindset in the face of future challenges (Peila-Shuster, 2017). These findings underscore the vital role of support from family in shaping career adaptability and position it as a significant driver of adaptive capacity in career development (Savickas, 2013). Higher levels of family support are associated with greater career adaptability, whereas lower levels of family support are linked to lower career adaptability.

It is undeniable that social capital provides supportive resources for career adaptability; however, its effect is contingent upon the bridging influence of psychological capital, which plays a central role in enhancing career adaptability. Previous research has shown a significant positive correlation between psychological capital and career adaptability, with psychological capital serving as a mediator (Zyberaj et al., 2022). Similarly, this study shows that career decision-making self-efficacyand goal orientation, as components of psychological capital, are directly associated with career adaptability and function as a bridging mechanism. Psychological capital refers to an individual’s positive psychological resources, which contribute to their attitudes, behaviors, and performance (Luthans et al., 2007). As Tomlinson (2017) emphasized in his capital model, psychological capital plays a crucial role in enhancing an individual’s ability to cope with adversity and solve problems. Individuals with higher levels of psychological capital may exhibit stronger adaptability and resilience, especially when faced with increased uncertainty in the work environment (Zacher, 2014). And thus, they benefit from this capital in the form of career success. In the context of career development, psychological capital transforms external social support (social capital) into internal resources (Gu et al., 2021), thereby influencing the process of acquiring knowledge and skills. These resources can be measured, developed, and guided to enhance adaptability, particularly in the workplace (Baig et al., 2021). Therefore, psychological capital can be portrayed as going beyond human (what you know) and social (who you know) capital to gain a personal competitive advantage through investment or development of ‘who you are’ (the actual self) and ‘what you intend to become (your possible self; Luthans et al., 2007). Moreover, Santos et al. (2018) found that compared with social capital, psychological capital predominantly drives an individual’s career performance. Consequently, psychological capital, as an intrinsic driving force of career adaptability, is crucial for individuals in maintaining adaptability and a positive attitude when facing career uncertainty. It plays an important role in the career adaptability process of individuals, helping them to cope with the pressures, challenges, and obstacles encountered during the job search process in a more proactive manner.

Another significant contribution of this study lies in the identification of urban-rural differences in career capital networks. Due to the enduring dual social structure in contemporary Chinese society, urban and rural residents experience significant disparities across multiple domains of development. Among these, social capital, as a form of social structure, functions as a metaphor for advantage. It consists of a hierarchy of positions that resembles a pyramid. Beyond the differences in network quality and structure between urban and rural contexts, individuals occupying higher positions within the structure tend to have broader access to resources and a more expansive perspective (Lin, 2001). By contrast, individuals in rural areas are generally situated at lower levels of the social hierarchy, possessing relatively limited social capital. Lacking a competitive edge in the labor market, they are more likely to have a constrained career outlook and place disproportionate emphasis on familial influences during their career development. While disparities in social capital persist, psychological capital serves as a core individual resource—one that forms the foundation for acquiring other types of capital (Luthans et al., 2004). It is closely linked to personal growth and development, and positive changes in psychological capital can enhance individuals’ readiness for career advancement (Kirrane et al., 2017). Even within structurally unequal contexts, different psychological dimensions of psychological capital can play a compensatory role.

Recent scholarship has increasingly emphasized that social capital is no longer the most decisive factor; rather, psychological capital is seen as a critical driver that enables individuals to navigate adversity and enact meaningful change within their environments (Mardika et al., 2024). It empowers individuals to fulfill their responsibilities and accomplish tasks despite structural constraints (Luthans et al., 2006). Empirical evidence indicates that rural youth face more limited opportunities for career development and encounter greater challenges in accessing education and social mobility. More critically, disparities in social class foster distinct internalized cultural, psychological, and subjective orientations—factors that transcend income, parenting styles, and educational attainment, and contribute to the formation of unique self-construal (Soresi et al., 2014). Thus, it is both logical and necessary for rural students to develop psychological capital as a means of compensating for structural disadvantages.

Implications for student counseling and development practice

This study advances the existing literature by adopting an integrative career capital framework to explore the dynamic interplay between social capital, psychological capital, and career adaptability. By conceptualizing these constructs as interconnected components within a network analysis model, our research sheds light on the nuanced pathways through which capital resources interact, demonstrating how capital can be cyclically transformed and utilized to acquire other forms of capital, while also revealing critical urban-rural disparities in career development mechanisms. These findings offer valuable insights for career interventions, introducing a new approach that emphasizes the importance of delivering personalized and targeted services based on the unique characteristics of different groups. This approach helps individuals receive the most effective support, thereby enhancing their career adaptability.

Limitations and future directions

Four key limitations should be considered. First, while this study extends prior research (Chen et al., 2021; Fung, 2015) by highlighting urban–rural differences in specific dimensions of social and psychological capital, it falls short of explaining the underlying mechanisms driving these differences. Moreover, the analysis does not account for intra-group heterogeneity within the urban and rural samples, thereby overlooking structural disparities that may exist within each group. Future research should employ more nuanced, stratified approaches to uncover how social and psychological capital interact across varying urban and rural contexts and through what mechanisms they jointly contribute to individuals’ career adaptability. Such efforts would strengthen the interpretive depth and practical relevance of the findings.

Second, this study focuses on social capital and psychological capital effects on career adaptability among urban and rural individuals, without considering human capital as an analytical variable. However, previous literature has indicated that human capital forms the foundation of individuals’ performance in the labor market (Tomlinson, 2017) and is regarded as a core element of employability (Clarke, 2018), playing a crucial role in career adaptability. Thus, while the role of human capital in career adaptability is undeniable, it was not included in the current analysis due to the specific focus of this study. Future research should consider incorporating human capital to offer a more comprehensive understanding of how human, social, and psychological capital collectively influences career adaptability among individuals.

Third, this study does not account for how social capital and psychological capital impacts career adaptability across different cultural contexts. This limitation may constrain the generalizability and applicability of the theoretical framework. Future research that incorporates cross-cultural comparative analysis would provide a more comprehensive perspective, offering a more refined theoretical foundation for career adaptability interventions on a global scale.

Finally, this study employed a cross-sectional design, collecting data at a single point in time, which restricted the ability to observe the dynamic relationships of these factors over time. Future research could employ longitudinal designs to further investigate the long-term effects and evolving patterns of these forms of capital on people’s career adaptability, thus providing more comprehensive and persuasive conclusions.

This study, grounded in the framework of career capital theory, uses network analysis to explore the intricate relationships between social capital, psychological capital, and individual career adaptability. The results indicate that both social and psychological capitals have significant impacts on career adaptability, with psychological capital playing a key bridging role in transforming external social capital into adaptive capacities. Additionally, the study reveals differences in the associations between social capital, psychological capital, and career adaptability across urban and rural groups, suggesting that the influence of these forms of capital on career adaptability operates differently in distinct geographical contexts.

These findings align with previous studies that highlight marked differences in social and psychological capital between urban and rural populations (Fung, 2015). Therefore, future career development interventions should be tailored to the regional characteristics of students to more effectively enhance their career adaptability.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by “planning subject for the 14th five year plan of national education sciences of China (DBA210296).”

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhijun Liu; data collection: Junlong Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhijun Liu; draft manuscript preparation: Zhijun Liu and Junlong Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Changchun University of Science and Technology (Approval No. 20250219).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Aguirre-Urreta, M. I., & Hu, J. (2019). Detecting common method bias: Performance of the Harman’s single-factor test. ACM SIGMIS Database: The DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 50, 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1145/3330472.3330477 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

AhmadiGatab, T., & Taheri, M. (2011). The relationship between psychological health, happiness and life quality in the students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30(3–14), 1983–1985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.385 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Andini, F. A., Josephine, A., & Riasnugrahani, M. (2025). Family influence and career adaptability: The mediating role of future time perspective. Personifikasi: Jurnal Ilmu Psikologi, 16(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.21107/personifikasi.v16i1.25655 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baig, S. A., Iqbal, S., Abrar, M., Baig, I. A., Amjad, F., et al. (2021). Impact of leadership styles on employees’ performance with moderating role of positive psychological capital. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 32(9–10), 1085–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2019.1665011 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bourdieu, P. (2012). Le capital social: Notes provisoires. Idées économiques Et Sociales, 169(3), 63–65. https://doi.org/10.3917/idee.169.0063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, J., & Chen, Z. (2008). Extended Bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika, 95(3), 759–771. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/asn034 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, H., Liu, F., & Wen, Y. (2023). The influence of college students’ core self-evaluation on job search outcomes: Chain mediating effect of career exploration and career adaptability. Current Psychology, 42(18), 15696–15707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02923-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chen, S., Xue, Y., Chen, H., Ling, H., Wu, J., et al. (2021). Making a commitment to your future: Investigating the effect of career exploration and career decision-making self-efficacy on the relationship between career concern and career commitment. Sustainability, 13(22), 12816. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212816 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Clarke, M. (2018). Rethinking graduate employability: The role of capital, individual attributes and context. Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), 1923–1937. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1294152 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Creed, P. A., Fallon, T., & Hood, M. (2009). The relationship between career adaptability, person and situation variables, and career concerns in young adults. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

DeSimone, J. A., & Harms, P. D. (2018). Dirty data: The effects of screening respondents who provide low-quality data in survey research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(5), 559–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9514-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dewani, Y. R., & Nuzulia, S. (2024). Does social support contribute to career adaptability? Study at the final year student. Jurnal Indonesia Sosial Teknologi, 5(3), 946–969. https://doi.org/10.59141/jist.v5i3.946 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Direnzo, M. S., Greenhaus, J. H., & Weer, C. H. (2015). Relationship between protean career orientation and work-life balance: A resource perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(4), 538–560. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1996 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.10.1040 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dóci, E., Spruyt, B., De Moortel, D., Vanroelen, C., & Hofmans, J. (2023). In search of the social in psychological capital: Integrating psychological capital into a broader capital framework. Review of General Psychology, 27(3), 336–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680231158791 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fathi, J., Naderi, M., & Soleimani, H. (2023). Professional identity and psychological capital as determinants of EFL teachers’ burnout: The mediating role of self-regulation. Porta Linguarum, (2023c), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.vi2023c.29630 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2008). Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics, 9(3), 432–441. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxm045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: A psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fung, K. Y. (2015). Network diversity and educational attainment: A case study in china. Journal of Chinese Sociology, 2(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40711-015-0014-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gheyassi, A., & Alambeigi, A. (2024). The mediating role of career adaptability between proactive personality and entrepreneurial intention of agricultural students. Journal of Entreneurship and Agriculture, 11(1), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.61186/jea.11.1.121 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Glozah, F. N., & Pevalin, D. J. (2014). Social support, stress, health, and academic success in Ghanaian adolescents: A path analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 37(4), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gu, J., Yang, C., Zhang, K., & Zhang, Q. (2021). Mediating role of psychologicalcapital in the relationship between social support and treatment burden among olderpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Geriatric Nursing, 42(5), 1172–1177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2021.07.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Guan, Y., Wang, Z., Gong, Q., Cai, Z., Xu, S. L., et al. (2018). Parents’ career values, adaptability, career-specific parenting behaviors, and undergraduates’ career adaptability. The Counseling Psychologist, 46(7), 922–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000018808215 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Haenggli, M., & Hirschi, A. (2020). Career adaptability and career success in the context of a broader career resources framework. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119(1), 103414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103414 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hou, Z. J., Leung, S. A., Li, X., Li, X., & Xu, H. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale—China form: Construction and initial validation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 686–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hou, C., & Liu, Z. (2021). Tacit knowledge mediates the effect of family socioeconomic status on career adaptability. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(6), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.9974 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hou, C., Wu, L., & Liu, Z. (2014). Effect of proactive personality and decision-making self-efficacy on career adaptability among Chinese graduates. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(6), 903–912. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.6.903 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hou, C., Wu, Y., & Liu, Z. (2019). Career decision-making self-efficacy mediates the effect of social support on career adaptability: A longitudinal study. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 47(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.8157 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, J. L., Curran, P. G., Keeney, J., Poposki, E. M., & DeShon, R. P. (2012). Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9231-8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Inkson, K., & Arthur, M. B. (2001). How to be a successful career capitalist. Organizational Dynamics, 30(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0090-2616(01)00040-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jiang, R., Fan, R., Zhang, Y., & Li, Y. (2022). Understanding the serial mediating effects of career adaptability and career decision-making self-efficacy between parental autonomy support and academic engagement in Chinese secondary vocational students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 953550. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.953550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jones, P. J., Ma, R., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Bridge centrality: A network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 353–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Järlström, M., Brandt, T., & Rajala, A. (2020). The relationship between career capital and career success among Finnish knowledge workers. Baltic Journal of Management, 15(5), 687–706. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-10-2019-0357 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Karatepe, O. M., & Olugbade, O. A. (2017). The effects of work social support and career adaptability on career satisfaction and turnover intentions. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(3), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.12 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kirrane, M., Lennon, M., O’Connor, C., & Fu, N. (2017). Linking perceived management support with employees’ readiness for change: The mediating role of psychological capital. Journal of Change Management, 17(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2016.1214615 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liang, G., Barnhart, W. R., Cheng, Y., Lu, T., & He, J. (2023). The interplay among BMI, body dissatisfaction, body appreciation, and body image inflexibility in Chinese young adults: A network perspective. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 29(1), 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2023.07.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, N. (2001). Social capital: A theory of social structure and action. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Lupşa, D., Vîrga, D., Maricuţoiu, L. P., & Rusu, A. (2020). Increasing psychological capital: A pre-registered meta-analysis of controlled interventions. Applied Psychology, 69(4), 1506–1556. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12219 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Li, W. (2005). The psychological capital of Chinese workers: Exploring the relationship with performance. Management and Organization Review, 1(2), 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2005.00011.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luthans, F., Luthans, K. W., & Luthans, B. C. (2004). Psychological capital: Beyond human and social capital. Business Horizons, 47(1), 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2003.11.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luthans, F., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Lester, P. B. (2006). Developing the psychological capital of resiliency. Human Resource Development Review, 5(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305285335 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1(4), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026595011371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mardika, H. A., Suharto, B., & Syahputra, D. N. (2024). The role of psychological capital and readiness for change in rural tourism: A phenomenological study. Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology, 13(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.12928/jehcp.v13i1.27467 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Matijaš, M., & Seršić, D. M. (2021). The relationship between career adaptability and job-search self-efficacy of graduates: The bifactor approach. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(4), 683–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/10690727211002281 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ngoma, M., & Dithan Ntale, P. (2016). Psychological capital, career identity and graduate employability in Uganda: The mediating role of social capital. International Journal of Training and Development, 20(2), 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12073 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pajic, S., Keszler, Á., Kismihók, G., Mol, S. T., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2018). Antecedents and outcomes of Hungarian nurses’ career adaptability. International Journal of Manpower, 39(8), 1096–1114. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-10-2018-0334 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pan, J., Guan, Y., Wu, J., Han, L., Zhu, F., et al. (2018). The interplay of proactive personality and internship quality in Chinese university graduates’ job search success: The role of career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 109(2), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.09.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Park, S. Y., Cha, S. B., Joo, M. H., & Na, H. (2022). A multivariate discriminant analysis of university students’ career decisions based on career adaptability, social support, academic major relevance, and university life satisfaction. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 22(1), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09480-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peila-Shuster, J. J. (2017). Women’s career construction: Promoting employability through career adaptability and resilience. In: M. Coetzee (Ed.Psychology of career adaptability, employability and resilience (pp. 283–297). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66954-0_17 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peng, J. C., & Chen, S. W. (2023). Learning climate and innovative creative performance: Exploring the multi-level mediating mechanism of team psychological capital and work engagement. Current Psychology, 42(15), 13114–13132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02617-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Peng, Y. X., & Long, L. R. (2001). Study on the scale of career decision-making self-efficacy for university students. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 2, 38–43. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1006-6020.2001.02.007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Porfeli, E. J., & Savickas, M. L. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale-usa form: psychometric properties and relation to vocational identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 748–753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ramos, K., & Lopez, F. G. (2018). Attachment security and career adaptability as predictors of subjective well-being among career transitioners. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104(3), 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.10.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rogers, M. E., & Creed, P. A. (2011). A longitudinal examination of adolescent career planning and exploration using a social cognitive career theory framework. Journal of Adolescence, 34(1), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rudolph, C. W., & Zacher, H. (2021). Age inclusive human resource practices, age diversity climate, and work ability: Exploring between-and within-person indirect effects. Work, Aging and Retirement, 7(4), 387–403. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waaa008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Salim, R. M. A., Istiasih, M. R., Rumalutur, N. A., & Situmorang, D. D. B. (2023). The role of career decision self-efficacy as a mediator of peer support on students’ career adaptability. Heliyon, 9(4), e14911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14911. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Santos, A. S., Reis Neto, M. T., & Verwaal, E. (2018). Does cultural capital matter for individual job performance? A large-scale survey of the impact of cultural, social and psychological capital on individual performance in Brazil. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 67(8), 1352–1370. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-05-2017-0110 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Savickas, M. L. (2002). Career construction: a developmental theory of vocational behavior. In: D. Brown (Ed.Career choice and development (pp. 149–205). San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

Savickas, M. L., Porfeli, E. J., Hilton, T. L., & Savickas, S. (2018). The student career construction inventory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106, 138–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.01.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Septyven, D. R., & Wijono, S. (2024). Social support and career adaptability: A study on early career employees. Philanthropy: Journal of Psychology, 8(2), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.26623/philanthropy.v8i2.10961 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sneed, R. S., & Cohen, S. (2014). Negative social interactions and incident hypertension among older adults. Health Psychology, 33(6), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Snyder, C. R., Cheavens, J., & Sympson, S. C. (1997). Hope: An individual motive for social commerce. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 1(2), 107–118. [Google Scholar]

Soresi, S., Nota, L., Ferrari, L., & Ginevra, M. C. (2014). Parental influences on youth’s career construction. In: Handbook of career development. New York, NY, USA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9460-7_9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sou, E. K., Yuen, M., & Chen, G. (2022). Career adaptability as a mediator between social capital and career engagement. The Career Development Quarterly, 70(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12289 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun, Y. (2025). Psychological capital and subjective well-being: A multi-mediator analysis among rural older adults. BMC Psychology, 13(1), 315. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02407-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Taylor, K. M., & Betz, N. E. (1983). Applications of self-efficacy theory to the understanding and treatment of career indecision. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 22(1), 63–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(83)90006-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tolentino, L. R., Garcia, P. R., Lu, V. N., Restubog, S. L., Bordia, P., et al. (2014). Career adaptation: The relation of adaptability to goal orientation, proactive personality, and career optimism. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.11.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tomlinson, M. (2017). Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability. Education + Training, 59(4), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2016-0090 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Valente, T. W. (2012). Network interventions. Science, 337 (6090), 49–53. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1217330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Van Borkulo, C. D., Wichers, M., Boschloo, L., Schoevers, R. A., Kamphuis, J. H., et al. (2017). The contact process as a model for predicting network dynamics of psychopathology. Retrieved from:https://www.researchgate.net/profile/claudia-van-borkulo-/publication/336810093_the_contact_process_as_a_model_for_predicting_network_dynamics_of_psychopathology/links/5db3015d4585155e2701052d/the-contact-process-as-a-model-for-predicting-network-dynamics-of-psychopathology.pdf. [Google Scholar]

van der Horst, A. C.,, Klehe, U. C., Brenninkmeijer, V., & Coolen, A. C. (2021). Facilitating a successful school-to-work transition: Comparing compact career-adaptation interventions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 128(3), 103581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103581 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

VandeWalle, D. (1997). Development and validation of a work domain goal orientation instrument. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 57(6), 995–1015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164497057006009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xing, X., & Rojewski, J. W. (2018). Family influences on career decision-making selfefficacy of Chinese secondary vocational students. New Waves Educational Research and Development, 21(1), 48–67. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/Ej1211290.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Xu, Q., Hou, Z., Zhang, C., Cui, Y., & Hu, X. (2024). Influences of human, social, and psychological capital on career adaptability: Net and configuration effects. Current Psychology, 43(3), 2104–2113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04373-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xu, Q., Hou, Z., Zhang, C., Yu, F., & Li, T. (2022). Career capital and well-being: A configurational perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10196. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Yousefi, Z., Abedi, M., Baghban, I., Eatemadi, O., & Abedi, A. (2011). Personal and situational variables, and career concerns: Predicting career adaptability in young adults. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14(1), 263–271. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2011.v14.n1.23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zacher, H. (2014). Career adaptability predicts subjective career success above and beyond personality traits and core self-evaluations. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.10.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, J., & Huang, J. (2021). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy mediates the impact of the post-pandemic entrepreneurship environment on college students’ entrepreneurial intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 643184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.643184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, L., Liu, J., Loi, R., Lau, V. P., & Ngo, H. Y. (2010). Social capital and career outcomes: A study of Chinese employees. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(8), 1323–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2010.483862 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zulfiani, H., Khaerani, N. M., & Sosial, F. I. (2021). Interrelation between career adaptability and family support, gender and school type. Jurnal Psikologi Integratif, 8(2), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.14421/jpsi.v8i2.1888 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zyberaj, J., Seibel, S., Schowalter, A. F., Pötz, L., Richter-Killenberg, S., et al. (2022). Developing sustainable careers during a pandemic: The role of psychological capital and career adaptability. Sustainability, 14(5), 3105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14053105 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools