Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Customer-employee exchange work through psychological safety and self-efficacy for improved hotel employees’ work engagement

School of Management Engineering and Business, Hebei University of Engineering, Handan, 056038, China

* Corresponding Author: Fan Deng. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 797-805. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068735

Received 05 June 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between customer-employee exchange (CEX) and employee work engagement (vigor, dedication, absorption), and the role of psychological safety and self-efficacy mediate that relationship. Survey data were collected from 329 Chinese hotel employees (females = 52.9%, tenure: 1–3 years = 50.5%). The results following ordinary least squares regression and the SPSS PROCESS macro indicate that higher customer-employee exchange is associated with employee vigor, dedication, and absorption. Psychological safety and self-efficacy mediate the relationship between customer-employee exchange and vigor and dedication to be stronger, while the work absorption mediating effect is not significant. Our findings underscore the importance of adopting a social exchange theory lens for high-quality customer–employee exchange in service settings–and how this exchange translates into engagement through the socio-cognitive mechanisms of psychological safety and self-efficacy. These findings suggest a need for human resources managers in the hotel industry to engage in customer-employee exchange practices for higher employee work engagement.Keywords

In the current highly competitive hospitality service industry, employees are key to service quality for improved business performance and development (Kim & Qu, 2020). Engaged employees exhibit high levels of energy (vigor), actively participate in their work, show enthusiasm (dedication), and immerse themselves in (absorption) their tasks (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Necessarily employee work engagement is associated with the quality and efficiency of service delivery, which in turn impacts customer satisfaction and loyalty—factors that collectively shape an organization’s market competitiveness and brand reputation (Hassan et al., 2023). In service-oriented enterprises, customers serve not only as the primary points of contact and service recipients for employees, but also as core participants in the value creation process of the business. For employees to deliver to organization goals, they need a level of workplace psychological safety and sense of self-efficacy, self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to complete tasks (Bandura, 2011). Workplace psychological safety refers to individuals’ subjective perceptions of interpersonal relationships, team dynamics, and the organizational environment in which they can be authentic selves (Kahn, 1990). However, the hospitality industry is varied and they ways they engage customers in service co-creation would ne unique to the industry sector. We aimed to investigate these relationships in the hotel industry sector.

Customer-employee exchange and work engagement

Customer-employee exchange is by the quality of social interaction during service encounters with customers (Kim & Qu, 2020; Ma & Qu, 2011). In the hotel industry, services are highly interactive, with employees primarily tasked with serving customers (Victorino et al., 2005), which would require high levels of employee work engagement. This assumes an individual employee’s with stable disposition or tendency to prioritize customers’ needs and satisfaction (Lee & Wei, 2023). Unlike traditional antecedents of employee work engagement, which focus on stable organizational or personal factors, CEX highlights the dynamic, reciprocal interactions between customers and employees. Through these high-quality exchanges—characterized by trust, support, and responsiveness—employees gain valuable social and psychological resources. This energizes them and promotes greater involvement in their work, leading to higher levels of vigor, dedication, and absorption beyond what would be expected from their preexisting attitudes alone (Kim & Qu, 2020).

Vigor refers to employees’ ability to maintain high energy levels, resilience, and the capacity to confront challenges at work (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Customer-employee exchange (CEX) facilitates this vigor by providing emotional support and positive feedback, which help employees sustain their psychological vitality and energy. When customers express positive emotions and satisfaction, employees not only experience an enhanced sense of self-worth but also gain access to valuable emotional resources from customers. This positive feedback can boost employees’ energy and stress resilience, thereby enhancing their overall vigor. Haryati Shaikh Ali and Oly Ndubisi (2011) emphasize that high-quality customer interactions can build employees’ self-confidence, making them more likely to exhibit vigor at work and willing to invest greater effort in resolving challenges they encounter.

Dedication refers to employees’ high level of commitment to their work, a sense of meaningfulness in what they do, and a genuine passion and enthusiasm for their roles (Schaufeli et al., 2006). When individuals are recognized with dignity, respect, and appreciation for their contributions, they are likely to derive a meaningful sense of satisfaction from these interactions (May et al., 2004). Social exchange theory further explains that positive interaction experiences between employees and customers encourage employees to exhibit citizenship behaviors that benefit the customers (Scott, 2007). When employees perceive positive feedback from customers, they often feel motivated to reciprocate, seeking to repay the customers’ trust and support through increased work engagement (Lawler, 2001; Putra et al., 2017).

Absorption refers to the state in which employees are fully immersed in their work, experiencing time as passing quickly and finding it difficult to detach themselves from their tasks (Schaufeli et al., 2006). When interactions with customers are positive and meaningful, employees are more likely to invest greater cognitive and emotional resources into their work, leading to heightened attention to tasks and challenges. This deep engagement not only allows employees to find fulfillment and enjoyment during their interactions with customers but also strengthens their ongoing focus and commitment to their work. A meta-analysis by Mazzetti et al. (2023) indicates that when employees engage in their work, positive emotional feedback plays a crucial role in enhancing work engagement, which is essential for improving employees’ levels of focus.

Psychological safety mediation

Psychological safety would mediate the relationship between CEX and work engagement, assuming supportive leadership (Liu et al., 2020), and management practices in which employees can experiment, learn from mistakes, and contribute ideas without fear of penalty (Edmondson, 1999; Kahn, 1990).

In the context of hotel enterprises, customer-employee exchange (CEX) plays a crucial role in shaping psychological safety. Customers are not only primary contacts for employees but also active partners in co-creating value (Li & Hsu, 2016). High-quality interactions with customers, characterized by respect, politeness, and constructive feedback, provide social support and foster employees’ sense of belonging and acceptance (Lerman, 2006). This relational reinforcement enhances employees’ psychological safety, making them more willing to share ideas, engage in teamwork, and take initiative in their service activities (Li & Hsu, 2016).

Empirical evidence shows that employees who perceive a psychologically safe environment exhibit higher engagement, stronger organizational commitment, and more positive attitudes toward teamwork (De Clercq & Rius, 2007). In essence, psychological safety serves as the key mechanism through which relational inputs from customer interactions translate into enhanced engagement and discretionary effort among hotel employees.

As previously noted, self-efficacy defines individuals’ intrinsic belief in their ability to perform or engage in specific behaviors to achieve their preferred goals. In the service industry, positive feedback and support from customers are key sources for enhancing employees’ self-efficacy. For instance, when customers express satisfaction and gratitude, employees often feel that their work is recognized, which boosts their self-efficacy. This positive feedback mechanism helps fulfill employees’ psychological needs, leading to higher levels of engagement in their work. Furthermore, effective customer-employee exchange has lasting impacts on employees’ self-efficacy (Kim & Qu, 2020). For instance, ongoing positive feedback can help employees develop a more robust belief in their self-efficacy, thereby enhancing their creativity, adaptability, and work engagement.

Specifically, employees with high self-efficacy possess intrinsic motivation to pursue their goals and believe they can meet job demands, which stimulates their high levels of engagement at work (Luthans et al., 2007). Such employees tend to view their work as an opportunity for personal growth and achievement, resulting in a greater sense of work engagement and responsibility. The degree of self-efficacy directly influences how employees commit to their work, subsequently affecting their sustained focus and engagement with tasks.

Theoretical basis. Social Exchange Theory (SET) is considered one of the principal conceptual frameworks for understanding workplace behavior (Cropanzano et al., 2017). Through social exchange mechanisms, supportive interactions with both colleagues and customers are internalized, motivating employees to reciprocate with proactive behaviors, knowledge sharing, creativity, and improved performance (Ahmad et al., 2019). According to SET, the fundamental principles of interpersonal interaction are reciprocity and exchange. Employees gain social and emotional rewards through their interactions with customers, which in turn stimulates their work engagement. Positive feedback from customers, such as politeness, praise, or satisfaction, enhances employees’ emotional resources and encourages them to engage more actively in their work.

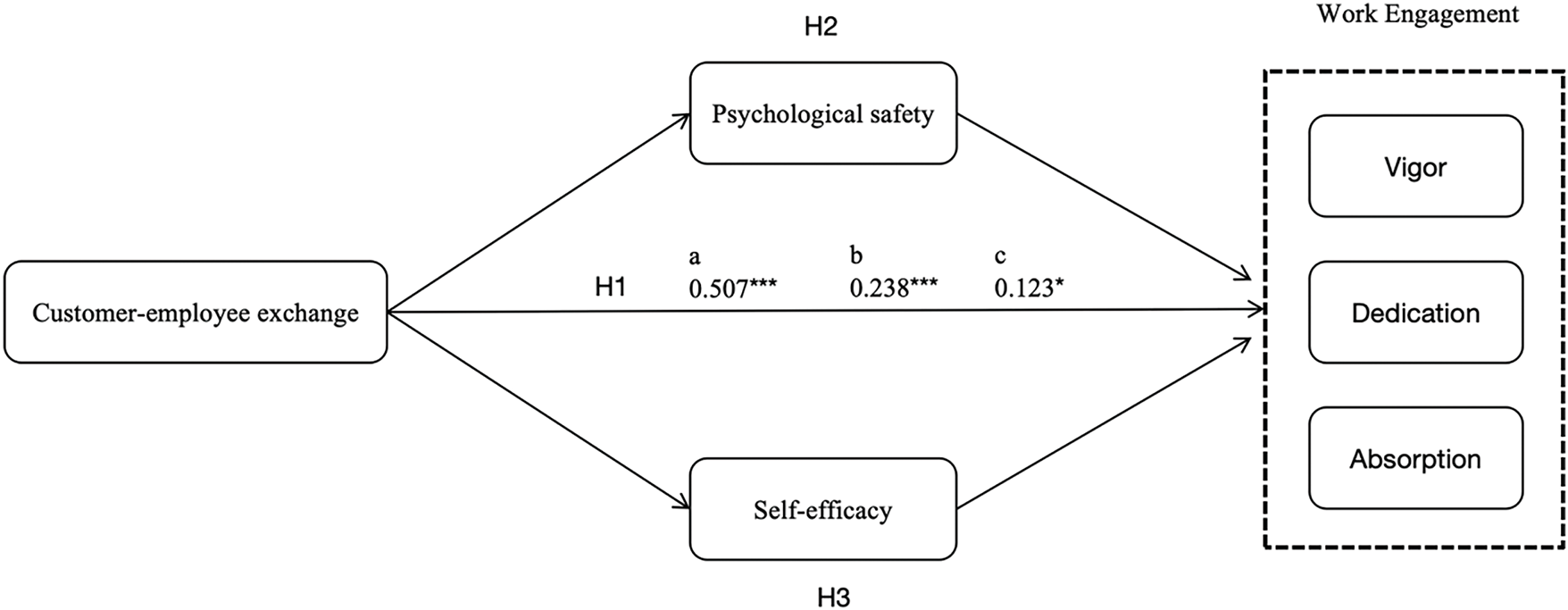

Goal of the study. This study examined customer-employee exchange and employee work engagement relationships with psychological safety and self-efficacy, We propose to test the following hypotheses based on our conceptual model (see Figure 1):

Figure 1: Hypothetical model. Note. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

H1. Customer-employee exchange is associated with higher work engagement.

H2. Psychological safety mediates the customer-employee exchange and work engagement relationship to be stronger.

H3. Employee self-efficacy mediates the customer-employee exchange and work engagement to be stronger.

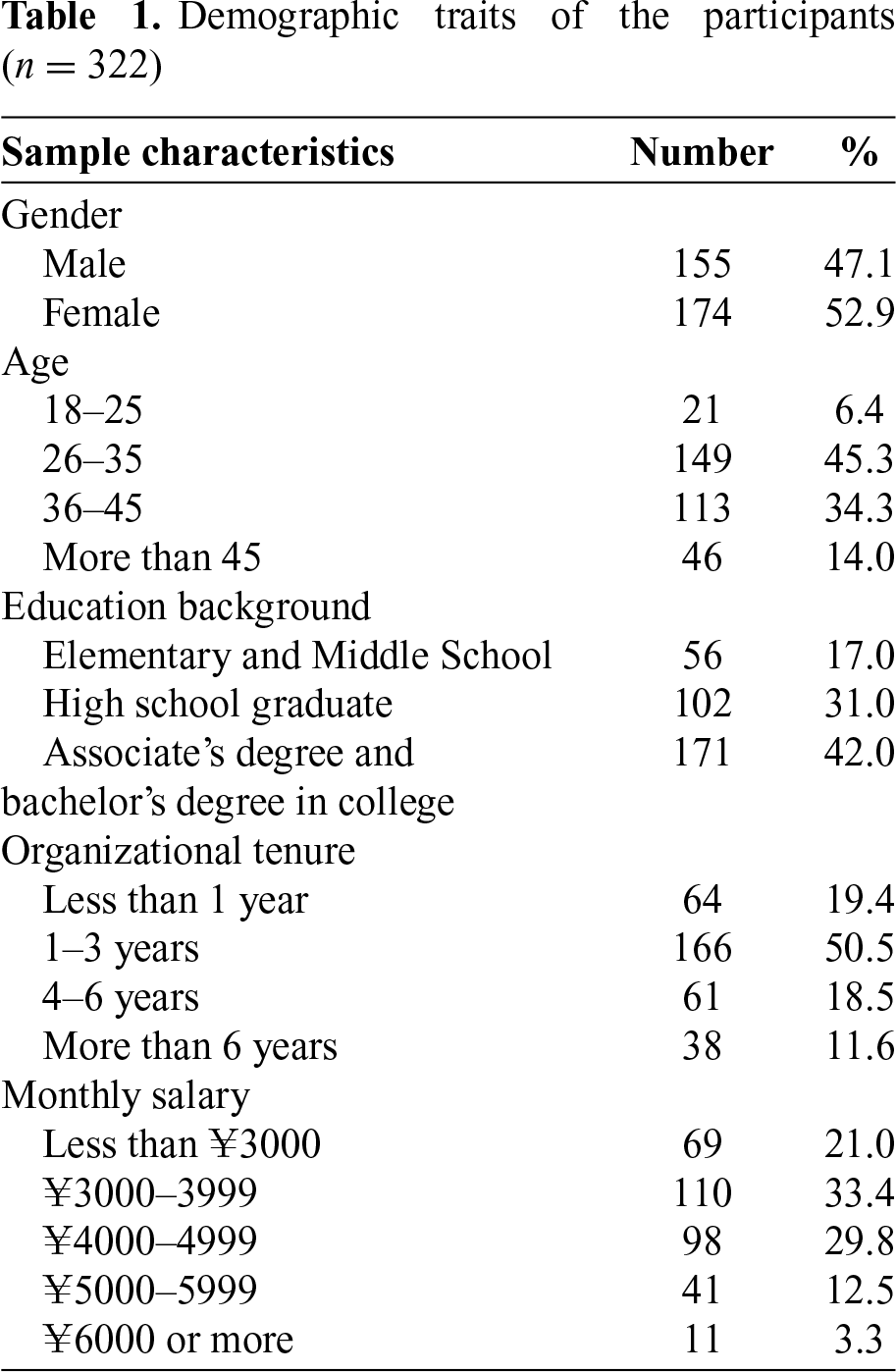

For this study, a total of 329 hotel employees in China were recruited by demographics, the sample comprised 47.1% males, and 52.9% females. The majority of participants were in the age groups of 26–35 years (45.3%) and 36–45 years (34.3%). Regarding educational background, most respondents held an Associate’s degree or bachelor’s degree in college (42.0%) or had completed high school (31.0%). Only 19.4% of respondents had less than one year of experience in the hotel industry, while the remaining participants had over one year of work experience in hotels. And the characteristics of the collected samples are presented in Table 1.

Measures of the constructs were adopted from existing English language publications, which were back-translated into Chinese. Items were scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Customer-employee exchange was measured on a twelve-item scale adopted from Keith et al. (2004). Participants indicated their agreement with statements such as “Customers and I are committed to the preservation of a good relationship”. Scores from this scale achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.932 in the present study.

Psychological safety was measured by using three items, adopted from May et al. (2004). It includes statements like “I’m not afraid to be myself at work”. The present study, scored from this scale, achieved a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.777.

We measured self-efficacy utilizing an 8-item scale developed by Chen et al. (2001). Example item is “I will be able to achieve most of the goals that I have set for myself”. Scale scores demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.933 in the present study.

Work engagement was assessed based on the dimensions of vigor, dedication, and absorption, as proposed by Schaufeli et al. (2006). Each dimension was measured using three items, totaling nine items. A sample item is “I feel powerful and alive at work”. Scores from this scale achieved Cronbach alpha reliabilities of 0.866, 0.776, and 0.770, respectively.

Control variables in the analysis included gender, age, educational background, organizational tenure, and monthly salary.

We used ordinary least squares (OLS) to conduct regression analysis. Specifically, we regressed customer-employee exchange on the three dimensions of work engagement: vigor, dedication, and absorption. Then we used the SPSS process macro to examine the mediation hypotheses, we conducted bootstrap analyses with 5000 repetitions using bootstrapped samples. We calculated 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (95% BC CI) to assess the (conditional) indirect effects, following the approach outlined by Preacher and Hayes (2008) and Preacher et al. (2007).

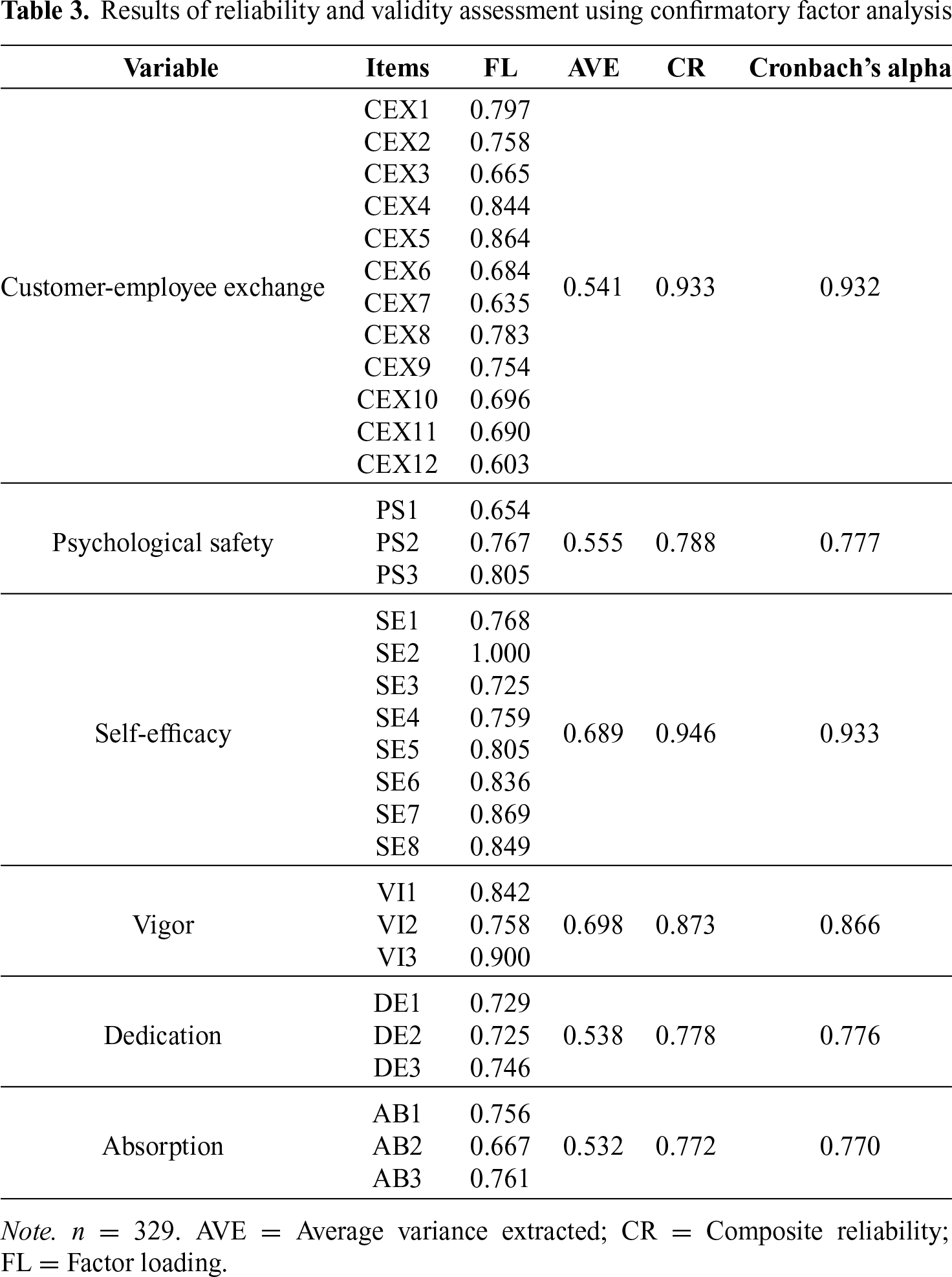

To assess the reliability and validity of the measurements, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The results of the EFA are presented in Table 2. Subsequently, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), with the results outlined in Table 3. This table lists the convergent validity, loadings, and average variance extracted (AVE) for our measurement model. For a few items with external loadings still below 0.7, we followed the recommendations of Hair et al. (2019) and decided to retain these items, as long as the AVE exceeded 0.50, rather than removing them.

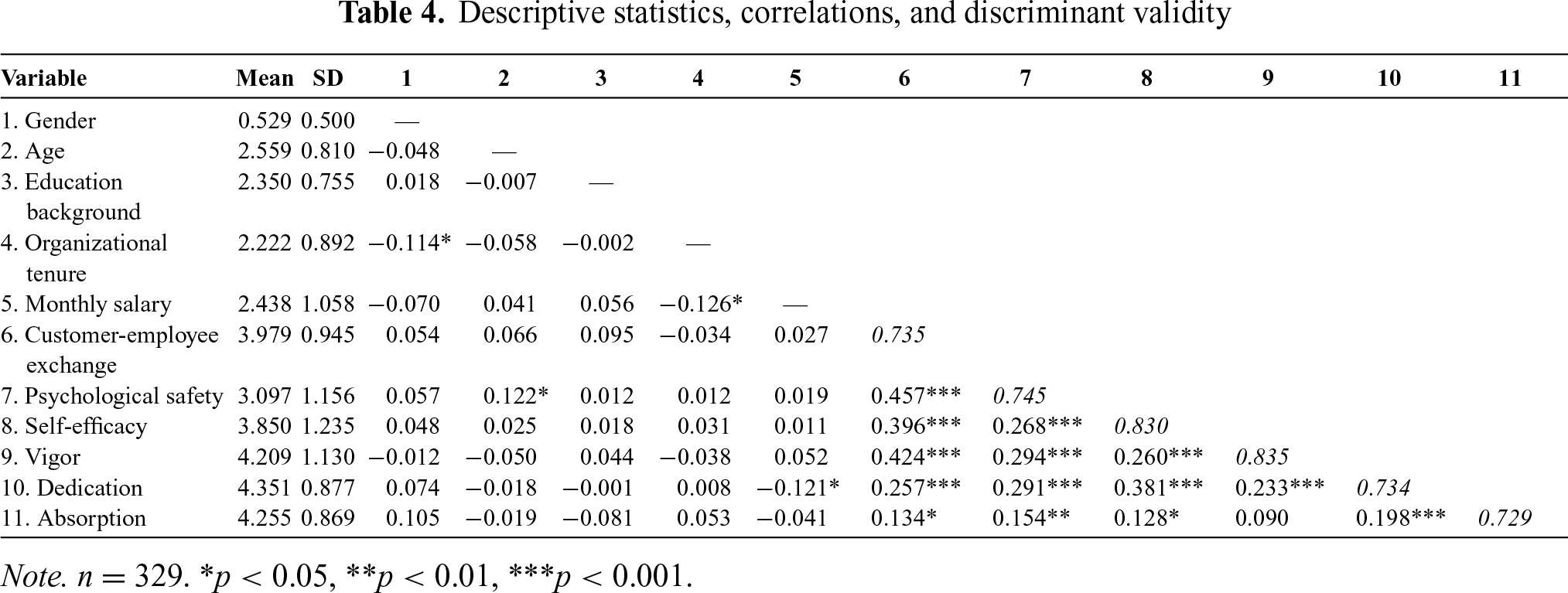

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics and correlations among the variables. There were significant correlations among variables. Customer-employee exchange was positively correlated with vigor (r = 0.424, p < 0.001), dedication (r = 0.257, p < 0.001), and absorption (r = 0.134, p < 0.05). Additionally, customer-employee exchange was also positively correlated with the two hypothesised mediators: interpersonal trust (r = 0.457, p < 0.001) and critical consciousness (r = 0.396, p < 0.001).

Direct effects of customer-employee exchange on work engagement

We tested all direct hypotheses using ordinary least squares (OLS), these relationship as depicted in Figure 1. Hypothesis 1 proposed a positive relationship between customer-employee exchange and the three dimensions of work engagement (β = 0.507, p < 0.001), (β = 0.238, p < 0.001), (β = 0.123, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 1a, Hypothesis 1b and Hypothesis 1c were supported.

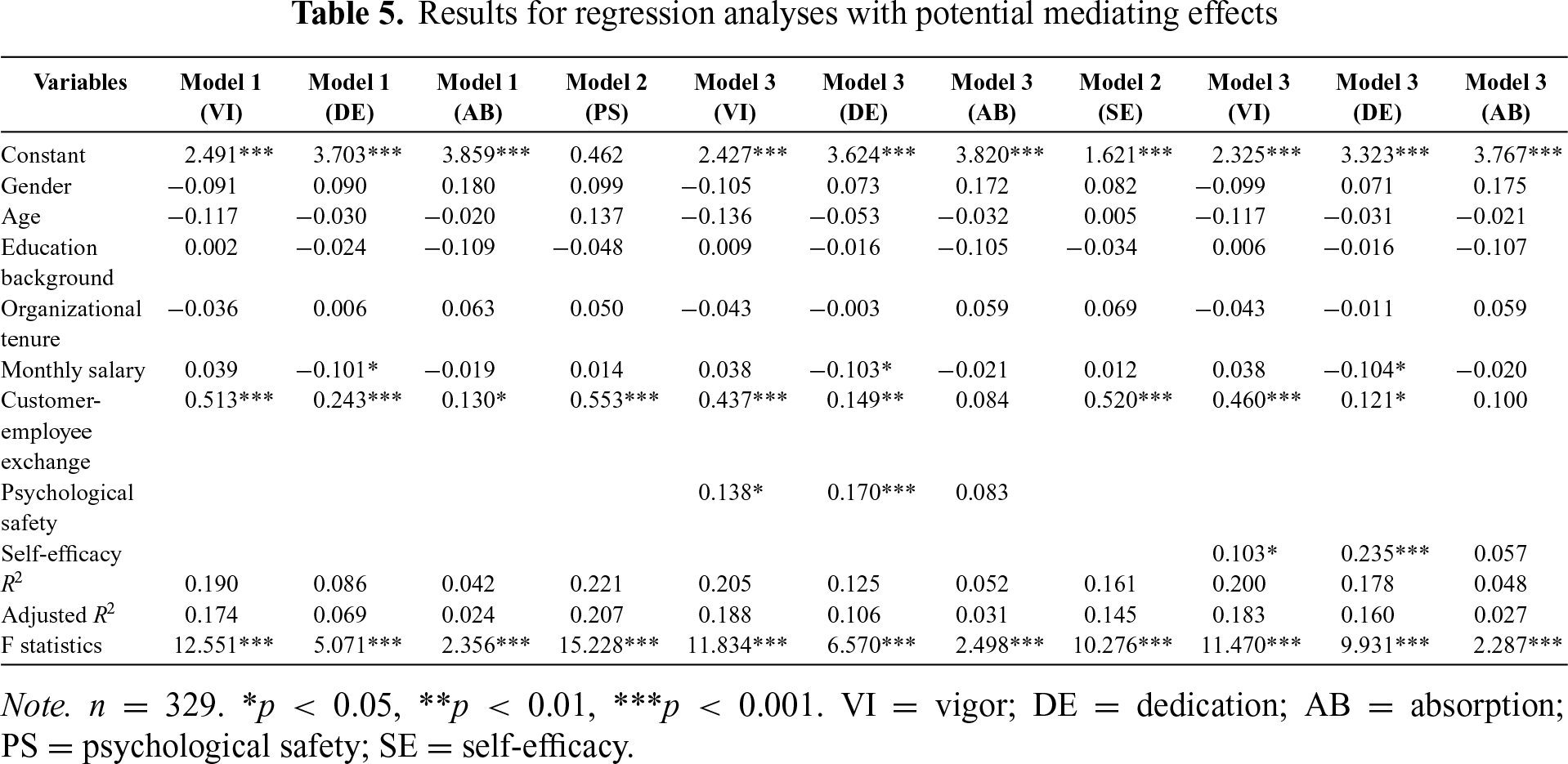

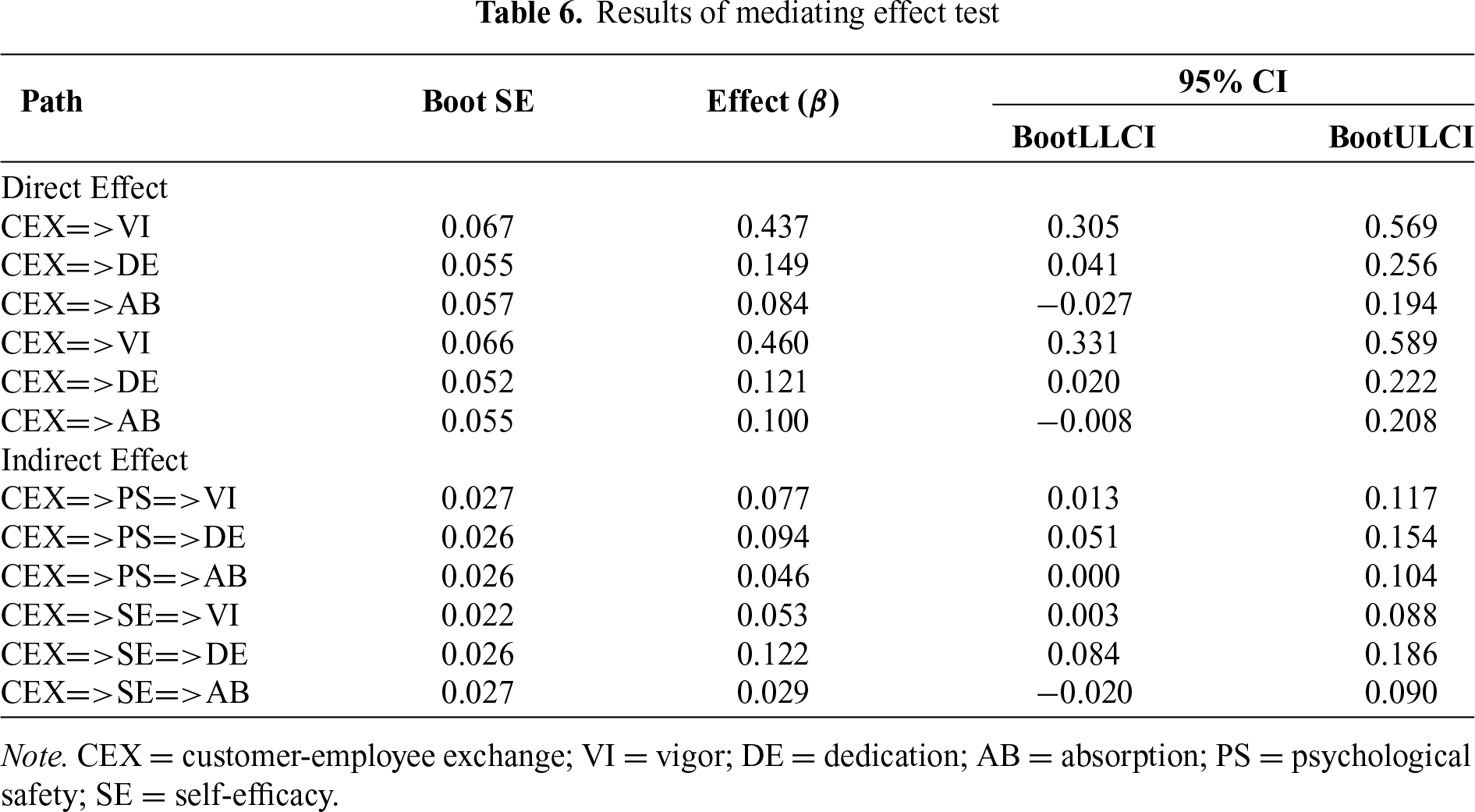

Indirect effects of psychological safety and self-efficacy

We used model 4 in the SPSS process macro to further validate the mediating effect. The results of the mediation effect are shown in Tables 5 and 6. Customer-employee exchange has a positive and significant indirect effect via psychological safety on vigor (β = 0.077, 95% BC CI [0.013, 0.117]) and dedication (β = 0.094, 95% BC CI [0.051, 0.154]). Therefore, hypothesis 2a and 2b are supported. In addition, customer-employee exchange has a positive and significant indirect effect via self-efficacy on vigor (β = 0.053, 95% BC CI [0.003, 0.088]) and dedication (β = 0.122, 95% BC CI [0.084, 0.186]). Thus, Hypothesis 3a and Hypothesis 3b were supported. However, the mediating effect of psychological safety (β = 0.046, 95% BC CI [0.000, 0.104]) and self-efficacy (β = 0.029, 95% BC CI [−0.020, 0.090]) between customer-employee exchange and absorption are not significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 2c and 3c are not supported.

This study found that: (i) customer-employee exchange has a significant positive impact on vigor, dedication, and absorption as dimensions of work engagement; (ii) psychological safety mediates the positive effects of customer-employee exchange on vigor and dedication; and (iii) self-efficacy also serves as a mediator in the positive relationship between customer-employee exchange and both vigor and dedication. However, the mediating effects of psychological safety and self-efficacy on the relationship between customer-employee exchange and absorption are not significant.

Firstly, high-quality customer-employee exchange can significantly enhance employees’ work engagement. According to existing literature, the antecedents of employee work engagement can be classified into job demands and personal resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007, 2017). At the interpersonal and social relational levels, one of the most researched resources is social support, characterized by the social atmosphere in the work environment, which includes relationships with supervisors and colleagues (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Jolly et al., 2021; Lesener et al., 2020). According to social exchange theory (SET), the fundamental dynamics of interpersonal interactions are based on principles of reciprocity and exchange (Cropanzano et al., 2017). The work engagement of employees in the service industry largely depends on the relationship between customers and employees; those employees who derive benefits from customers are more willing to reciprocate with greater engagement in their work (Lawler, 2001). Thus, this can lead to more positive levels of work engagement.

Secondly, psychological safety mediates the positive effects of customer-employee exchange on vigor and dedication. This may be explained by the fact a positive customer-employee exchange not only enables employees to receive immediate feedback but also provides emotional support and understanding when facing work challenges (Lerman, 2006). This form of social support contributes to a heightened sense of psychological safety, making employees more willing to share ideas, engage in teamwork, and take initiative in their work. Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to accomplish tasks (Bandura, 2011). In the service industry, positive feedback and support from customers are key sources for enhancing employees’ self-efficacy. Employees with high self-efficacy typically exhibit greater vigor and dedication because they have confidence in their abilities and are more inclined to accept challenging tasks. This positive attitude and behavior not only enhance their work enthusiasm but also contribute to improved quality and efficiency in task completion (Chan et al., 2017).

Thirdly, self-efficacy mediates the customer-employee exchange work engagement, likely though “resource reciprocity” (Lavoie et al., 2021). This may not be the case for the: “absorption” effect if the tasks themselves lack challenge or interest, as with “highly repetitive and low in creativity” jobs of front desk registration, housekeeping.

Implications for research and practice

Our study provides the following three contributions. First, we position customer-employee exchange (CEX) as a critical antecedent of hotel employees’ work engagement through the lens of social exchange theory. Given the hotel industry’s high-interaction nature—where employees’ core role is customer service (Kim & Qu, 2020). Our findings reveal that CEX significantly shapes work engagement highlights its actionable value. Unlike more stable exchanges (e.g., leader-member exchange), CEX is dynamic and context-dependent; however, its impact on employee behavior is substantial. Guided by the reciprocity principle (Kim & Qu, 2020), hotel managers can proactively enhance CEX quality by:

(1) Training frontline staff in “customer interaction literacy” (e.g., recognizing and responding to customer emotional cues, de-escalating conflicts);

(2) Establishing a “communication feedback paths”, because communication that conveys a positive attitude, demonstrates understanding and builds rapport fosters a sense of being valued (Deng & Zhu, 2025); and

(3) Equipping employees with tools to manage challenging customer encounters (e.g., clear service protocols for handling complaints) to reduce negative CEX experiences. These steps help employees perceive more supportive, positive customer interactions, which in turn drive greater work engagement.

Second, this study found psychological safety and self-efficacy make for stronger CEX and employee work engagement. Managers could enhance psychological safety for employee openness to learning opportunities and self-efficacy with “success-building” tasks (e.g., assigning junior employees to low-complexity customer service roles first, then gradually increasing challenges) and providing specific, positive feedback on employees CEX performance (e.g., “Your empathy during that guest complaint really helped resolve the issue”). Such practices would—reinforce employees confidence in their service capabilities. These actions strengthen the mediating role of psychological safety and self-efficacy, amplifying CEX positive impact on work engagement.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations warrant attention and offer opportunities for future research. First, our study relies on cross-sectional data to examine the impact of customer-employee exchange (CEX) on employee work engagement. However, the stability of CEX may fluctuate more significantly compared to leader-member exchange (LMX) and peer relationships. The inherent variability of CEX suggests that it may be less stable in the short term, which could limit the generalizability of our findings. Future research could adopt a longitudinal design to capture the dynamic nature of CEX over time and explore its potential long-term effects on employee outcomes. Furthermore, in this study, the mediating hypotheses regarding psychological safety and self-efficacy between CEX and absorption were not supported. This finding encourages us to consider additional mediators that influence the effects of CEX on employee engagement more thoroughly. This result also suggests two directions for future research: (1) incorporating more appropriate mediating variables (e.g., “perceived task enjoyment,” “task challenge assessment”); and (2) focusing on “high-creativity service positions” to further validate the link between CEX and absorption. Moreover, future studies could employ qualitative research methods, such as interviews, to further investigate employees’ psychological states in this process. Such insights could provide a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding for promoting sustainable growth in the hotel industry. Finally, these findings should be interpreted in light of the Chinese hotel context. The Chinese collectivistic cultural norms that emphasize harmony, customer primacy, and respect for hierarchy may heighten the effect of CEX on vigor and dedication, while the standardized nature of hotel services may restrict employees’ absorption. In contrast, in individualistic cultural contexts that value autonomy, direct communication, and task orientation, CEX may operate through different mechanisms. Future research is needed to examine these cross-cultural differences to assess the generalizability of our results.

This study results indicate that customer-employee exchange is associated with hotel employees’ work engagement. High-quality CEX provides employees with immediate feedback, emotional support, and understanding, which in turn encourages them to reciprocate with higher levels of work performance. Psychological safety and self-efficacy play key mediating roles in this process: psychological safety increases employees’ willingness to share ideas and engage in teamwork, while self-efficacy enhances their confidence in their abilities, making them more willing to take on challenging tasks and thereby further boosting vigor and dedication. Practically, hotel managers can strengthen the impact of CEX on work engagement by training frontline staff in customer interaction skills, establishing positive communication and feedback mechanisms, providing tools to manage challenging customer encounters, and designing “success-building” tasks with specific positive feedback. These practices help employees perceive more supportive and positive customer interactions, ultimately fostering greater overall work engagement.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The research was self-funded.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the author.

Ethics Approval: This experiment was approved by the Ethics Committee of the author’s institution.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Ahmad, I., Donia, M. B. L., & Shahzad, K. (2019). Impact of corporate social responsibility attributions on employees’ creative performance: The mediating role of psychological safety. Ethics & Behavior, 29(6), 490–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2018.1501566 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bandura, A. (2011). The social and policy impact of social cognitive theory. In: Social Psychology and Evaluation, pp. 33–70. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Chan, X. W., Kalliath, T., & Brough, P. (2017). Self-efficacy and work engagement: Test of a chain model. International Journal of Manpower, 38(6), 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-11-2015-0189 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E. L., Daniels, S. R., & Hall, A. V. (2017). Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 479–516. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0099 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

De Clercq, D., & Rius, I. B. (2007). Organizational commitment in Mexican small and medium-sized firms: The role of work status, organizational climate, and entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Small Business Management, 45(4), 467–490. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2007.00223.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deng, F., & Zhu, S. (2025). Do you want to continue? The effect of communication and knowledge sharing on franchisee’s intention to continue. Business Process Management Journal, 17(4), 64. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-12-2024-1237 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Haryati Shaikh Ali, S., & Oly Ndubisi, N. (2011). The effects of respect and rapport on relationship quality perception of customers of small healthcare firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 23(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/13555851111120452 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hassan, M. M., Jambulingam, M., Alagas, E. N., Uzir, Md U. H., & Halbusi, H. A. (2023). Necessities and ways of combating dissatisfactions at workplaces against the Job-Hopping Generation Y employees. Global Business Review, 24(6), 1276–1301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920926966 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jolly, P. M., Kong, D. T., & Kim, K. Y. (2021). Social support at work: An integrative review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(2), 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2485 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Keith, J. E., Lee, D.-J., & Leem, R. G. (2004). The effect of relational exchange between the service provider and the customer on the customer’s perception of value. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 3(1), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1300/j366v03n01_02 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim, H., & Qu, H. (2020). Effects of employees’ social exchange and the mediating role of customer orientation in the restaurant industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89, 102577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102577 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lavoie, R., Main, K., & Stuart-Edwards, A. (2021). Flow theory: Advancing the two-dimensional conceptualization. Motivation and Emotion, 46(1), 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-021-09911-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lawler, E. J. (2001). An affect theory of social exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 107(2), 321–352. https://doi.org/10.1086/324071 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, R. P., & Wei, S. (2023). Do employee orientation and societal orientation matter in the customer orientation—Performance link? Journal of Business Research, 159, 113722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113722 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lerman, D. (2006). Consumer politeness and complaining behavior. Journal of Services Marketing, 20(2), 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040610657020 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lesener, T., Gusy, B., Jochmann, A., & Wolter, C. (2020). The drivers of work engagement: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal evidence. Work & Stress, 34(3), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2019.1686440 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, M., & Hsu, C. H. C. (2016). Linking customer-employee exchange and employee innovative behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 56, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.04.015 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, C., Wang, C., & Wang, H. (2020). How do leaders’ positive emotions improve followers’ person-job fit in China? The effects of organizational identification and psychological safety. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-09-2019-0388 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ma, E., & Qu, H. (2011). Social exchanges as motivators of hotel employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: The proposition and application of a new three-dimensional framework. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(3), 680–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2010.12.003 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mazzetti, G., Robledo, E., Vignoli, M., Topa, G., Guglielmi, D. et al. (2023). Work engagement: A meta-analysis using the job demands-resources model. Psychological Reports, 126(3), 1069–1107. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211051988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Putra, E. D., Cho, S., & Liu, J. (2017). Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation on work engagement in the hospitality industry: Test of motivation crowding theory. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(2), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358415613393 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scott, K. D. (2007). The development and test of an exchange-based model of interpersonal workplace exclusion [Doctoral dissertation]. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky. [Google Scholar]

Victorino, L., Verma, R., Plaschka, G., & Dev, C. (2005). Service innovation and customer choices in the hospitality industry. Managing Service Quality: an International Journal, 15(6), 555–576. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520510634023 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools