Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Digital mental health: Integrating psychotherapeutic innovations and technology—A Nigerian perspective

Department of Psychology, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam, 432106, Anambra, Nigeria

* Corresponding Author: C. I. Onyemaechi. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 843-851. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.069734

Received 29 June 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Despite high burden of mental disorders in Nigeria, access to care remains critically limited, with stigma, inadequate infrastructure, and economic constraints posing significant barriers. Integration of mental health and technology offers unprecedented opportunities to bridge this treatment gap. This paper explores the potential of digital mental health interventions like mobile applications and teletherapy, as viable solutions through which mental health services could be expanded. Leveraging Nigeria’s growing digital ecosystem and mobile phone penetration, these innovations can provide scalable, cost-effective, and culturally relevant interventions, particularly in underserved areas. However, challenges such as digital literacy gaps, socio-cultural resistance, data privacy concerns, and infrastructural limitations threaten widespread adoption. Through an analysis of current technological advancements, local initiatives, and the evolving landscape of digital mental health, this paper highlights the need for multisectoral collaboration between mental health professionals, tech innovators, and policymakers. Psychotherapeutic innovations with digital solutions can revolutionize mental health care in Nigeria.Keywords

When people talk about basic human rights, they often focus on rights to life and liberty, freedom of speech and expression, and other such rights. The rights to life and liberty are, therefore, among the most widely recognized human rights. However, the right to mental health often receives less emphasis in public discourse. The definition of health by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being (World Health Organization Interim Commission, 1948; World Health Organization, 2022; Morgan, 2009; Brook, 2017; Palla et al., 2021) is crucial in understanding why mental health is a basic human right. The WHO definition shows that health is not complete without its physical, mental, and social dimensions. A holistic view of health will include these three aspects of well-being. However, mental health has historically received less attention than physical health in both global and national health systems, especially in low-income countries such as Nigeria (Abdulmalik et al., 2019). Despite its importance, mental health care remains underfunded, understaffed, stigmatized. This results in poor access to services for those in need. The problem may thus be attributed to the treatment gap between those who need mental health care and those who can access such care (Kohn et al., 2004). This treatment gap can, to a large extent, be resolved by the integration of mental health care and technology. With rapid technological advancement, digital tools offer opportunities for mental health professionals to extend care to underserved populations (World Health Organization, 2006; 2011). American Psychiatric Association (2023) notes that almost 50% of the world’s mental health patients do not have access to treatment. This gap can be reduced with the integration of digital tools in health care delivery. For instance, just as digital tools now allow people in rural areas to access libraries and information resources that were once out of reach, similar technological approaches should be applied to expand access to mental health care. Digital mental health addresses this gap. Around the world, increasing numbers of clinicians and patients are adopting mHealth technologies such as smartphone applications more regularly (Young et al., 2019). However, the Nigerian case seems to be different, as the lack of use of these applications in the Nigerian mental health care space is glaring (Jack-Ide & Uys, 2013; Kola et al., 2021). This is due to a confluence of factors including the digital divide and socio-cultural skepticism toward technology-based mental health solutions.

This paper aims to explore opportunities that will address mental health challenges in Nigeria by leveraging digital technology. The discussion will emphasize the role of multisectoral collaboration between mental health professionals, tech innovators, and policymakers in developing scalable solutions. Additionally, the paper will explore how Nigeria’s growing digital ecosystem and tech-savvy population can drive adoption, with a focus on creating culturally relevant, linguistically appropriate tools and innovative funding mechanisms to support sustainable implementation.

This is a narrative review that aims to synthesize and critically appraise the global and Nigerian evidence on digital mental health interventions. The primary aim is to consolidate global evidence on digital psychotherapeutic innovations and analyze their applicability, challenges, and opportunities within Nigeria’s socio-cultural and economic context.

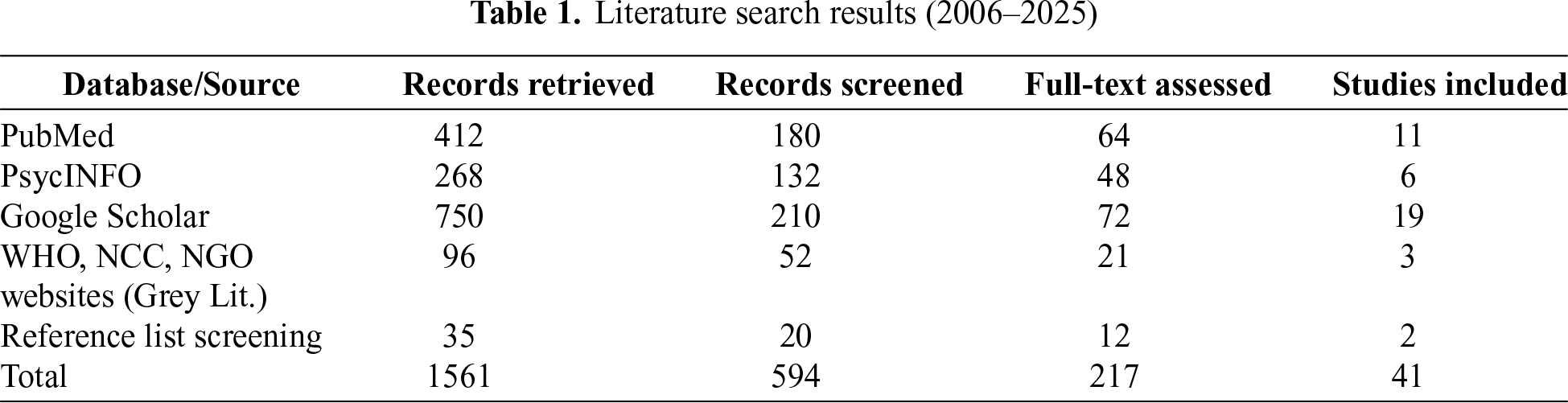

To ensure a comprehensive and reproducible review of the literature, a systematic search strategy was designed and executed in February 2025. The search was conducted across three major electronic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar. Additional searches were performed on the websites of key organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC) and Nigerian mental health non-profits. This was done to capture relevant grey literature.

The search syntax combined keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms within three major domains: Digital Technology (“digital health” or “e-health” or “mHealth” or “mobile health” or teletherapy or “mobile app”), Mental Health (“mental health” or “mental disorder” or psychotherapy or “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy” or CBT or “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy” or ACT or “Emotion-Focused Therapy” or EFT) and Context (“Nigeria” or “Sub-Saharan Africa” or “Low and Middle-Income Country”).

The researchers included only works published between 2006 and February 2025. The starting point was chosen as it marked the release of the WHO’s first Global Observatory for eHealth report. So, the period between 2006 and 2025 is the most appropriate and meaningful timeframe for analyzing the opportunities and challenges of integrating digital technology into Nigeria’s mental health system. The researchers included peer-reviewed journal articles, systematic reviews, and grey literature reports published in English that discussed the development, implementation, or evaluation of digital mental health tools. Articles were excluded if they focused solely on digital health in non-mental health contexts.

For the study selection process, two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified records while two other reviewers also independently retrieved and assessed the full texts of potentially relevant articles for final inclusion. Any discrepancies between both sets of reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus. Findings were synthesized thematically under key domains including global innovations, local initiatives, challenges, opportunities, and psychotherapeutic adaptations.

As shown in Table 1, a total of 1561 records were retrieved from all sources, of which 594 were screened. Following eligibility assessment, 217 full-text papers and reports were reviewed in detail, and 41 studies met inclusion criteria.

Thematically, included studies clustered into five main domains:

1. Global innovations in digital mental health

2. Local Nigerian initiatives

3. Identified challenges

4. Opportunities for adoption

5. Psychotherapeutic adaptations for Nigerian contexts

Global innovations such as internet-based CBT, ACT applications, and teletherapy platforms demonstrated efficacy across diverse populations. Nigerian-specific evidence highlighted initiatives like the Mentally Aware Nigeria Initiative (MANI) and mobile penetration trends that provide opportunities for scaling.

Psychotherapeutic adaptations for CBT, ACT, and EFT emphasized the necessity of cultural sensitivity, religious values, and locally relevant behavioral activation strategies.

This review demonstrates that digital mental health is both feasible and necessary in Nigeria. But widespread implementation remains constrained by systemic, cultural, and infrastructural barriers. While global models provide robust evidence of effectiveness, direct transferability is limited without cultural and contextual adaptation. Interventions must therefore address Nigeria’s unique socioeconomic realities, religious orientations, and stigma levels.

Findings suggest that local initiatives like Mentally Aware Nigeria Initiative (MANI) represent important entry points but require rigorous evaluation for sustainability and impact. Digital platforms that integrate local languages, faith-based frameworks, and community support systems are likely to gain higher acceptance. Collaboration across stakeholders (including government agencies, health professionals, tech startups, and international donors) will be essential to reduce the digital divide, strengthen ethical and privacy frameworks, and build digital literacy among providers and users. Overall, while challenges are formidable, Nigeria’s growing digital infrastructure and youth-driven tech culture provide fertile ground for innovation.

This discourse of digital mental health in Nigeria will be stronger with the highlight of the empirical realities regarding internet penetration, digital access, and mental health utilization. This contextual basis will help paint the necessary picture of the state of digital connectivity and the gap digital tools will fill in the mental health space.

Digital connectivity and mobile penetration in Nigeria

Since the introduction of mobile telephones in Nigeria in 2001 (Agwu & Carter, 2014; Nigerian Communications Commission, 2023), the digital landscape has seen exponential growth. The commission noted that the active subscribers in 2001 were around 400,000 and as at the end of 2016, they had grown to approximately 92 million. The same source also reports that the number of internet users in Nigeria stood at a 107 million in the same time period (Statista, 2025). This places Nigeria in the first place in any discussion concerning the number of internet users in Africa. It is also pertinent to note that 86.2% of Nigeria’s web traffic is generated via smartphones. This highlights mobile technology as the primary medium through which digital interventions can reach users. The breadth of network coverage is another critical factor. Internet usage clusters significantly in urbanized regions such as Lagos, Oyo, Ogun, Kaduna, and Abuja. For instance, only 9% of individuals with a DSM-IV (the diagnostic standard at the time of the study in reference) mental disorder in a 12-month period receive any form of treatment (Gureje & Lasebikan, 2006), with most not receiving even minimally adequate care. This demonstrates the huge treatment gap that exists between mental health care delivery and the patients who need the mental health care. This treatment gap is worsened by the acute shortage of professionals in the field, highlighting the need for other viable means of filling the gap to be explored since the traditional health care delivery has been deficient.

Technological Advancements in Digital Mental Health

Role of technology in addressing barriers

Considering the state of mental health in Nigeria, it becomes pertinent to look for solutions outside the traditional service delivery of mental healthcare. Digital technology provides a promising solution to the challenges facing mental healthcare in Nigeria by improving accessibility, scalability and affordability. Digital technology provides opportunities like the mHealth and telehealth. mHealth refers to the delivery of healthcare services, information, and support through mobile technology, including smartphones and tablets (Adaigbe et al., 2025). On the other hand, telehealth leverages virtual platforms and digital tools to provide patients with remote access to health information, preventive care, monitoring, and medical treatment (Mechanic et al., 2022).

Digital mental health platforms in Nigeria can play a transformative role by incorporating culturally tailored tools that nurture resilience through activities promoting psychological growth and meaningful engagement. Such interventions are particularly relevant in addressing mental health challenges among Nigerian youths, who often face adversity in environments with limited access to traditional mental health care (Nwobi et al., 2025),

Mobile apps, teletherapy platforms, and artificial intelligence-based tools provide opportunities to deliver mental health interventions directly to individuals. This resolves the issue of proximity and any stigma that may be rooted in an individual’s culture or religion. For example, teletherapy links patients with licensed therapists, even in remote areas, while mobile apps provide users with self-help resources, educational materials on mental health, and emergency intervention tools.

Psychotherapeutic innovations in digital space

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has attracted a lot of attention from researchers through the years as being effective (Olatunji et al., 2010; Agras & Bohon, 2021; Boness et al., 2023). Research-based Group CBT can be useful for the treatment of depressive symptoms, especially in patients with substance use disorders. The availability of web-based systems and mobile phones providing structured CBT packages, including web-based cognitive bias modification models shown to reduce anxiety (Eberle et al., 2024), have shown the sheer innovation of mental health delivery facilitated by digitizing CBT. These packages usually consist of modules on recognizing and challenging negative thought patterns, learning coping skills, and practicing relaxation skills. To be effective for the Nigerian population, these modules need to be adapted to address culturally relevant stressors like substance abuse and unemployment. Additionally, cognitive restructuring, which is a crucial component of CBT, must consider local belief systems. For instance, a client who says something like “My failure is caused by my village people,” should not be dismissed outrightly as “cognitive distortion”. The components of the digital CBT for Nigerians should be adapted to be culturally respectful while at the same time, promoting adaptive coping and strengthening recovery-supportive relationships within family and community systems (Jones et al., 2024). Instead of dismissing the client as having cognitive distortion, the client should get a response like “while it is understood that some people attribute failure to spiritual manipulations, let’s also explore practical steps we can take to improve your situation.” In this way, the cognitive restructuring component of CBT benefits from a culturally respectful adaptation for the Nigerian digital space. The “behavioral activation” component of CBT could also be adapted to suggest activities that are locally feasible and socially rewarding. These activities could include community gatherings, religious activities etc. Note that EFT digitization is in its early stage although it is gaining popularity via teletherapy sessions and guided self-help materials. Teletherapy sites facilitate direct interaction with therapists who have been trained in EFT. This enables clients to explore their emotional experience and strive towards interpersonal conflict resolution. Although EFT is very dependent on the therapeutic relationship, AI developments are being investigated to replicate empathy and allow emotional processing through virtual means. EFT could be adapted to for the Nigerian digital space. This would require integrating some culturally acceptable modes of emotional expression into therapy to reduce stigma and enhance acceptance.

Beyond established modalities such as CBT, EFT, and ACT, emerging narrative-based approaches are gaining attention for their capacity to integrate culture, emotion, and technology in innovative ways. Recent evidence suggests that emerging psychotherapeutic modalities such as digital storytelling are gaining global attention for their therapeutic potential (Ogbeiwi et al., 2024). A systematic review of 14 studies revealed that digital storytelling interventions can improve mood and enhance social connectedness, though the evidence for specific symptom reduction remains inconclusive. While these interventions are rooted in global contexts, they align well with Nigeria’s rich oral and narrative traditions, which have long served as cultural tools for healing and community connection. Therefore, digital storytelling offers an innovative pathway for culturally adapted digital mental health interventions in Nigeria, where storytelling, proverbs, and lived experiences are already central to meaning-making and emotional expression.

ACT largely acts to enhance psychological flexibility, that is the ability to be in the present moment with thoughts and emotions and being open to accepting them. It also acts to live in terms of one’s values (Zhang et al., 2018). Unlike conventional CBT, ACT addresses the change of one’s stance towards thoughts and feelings instead of altering their frequency or content (Hofmann & Asmundson, 2007). Digital ACT treatments most commonly comprise practice in mindfulness, value clarification instruments, and developing psychological flexibility strategies. The ACT in Daily Life (ACT-DL), for instance, has used a smartphone application that delivers visual prompts and exercises adapted from ACT sessions aimed at enhancing awareness and enabling patients to translate skills learned in the therapy into their daily settings (Vaessen et al., 2019). Adapting ACT to the Nigerian digital space would require that values clarification exercises be aligned with the spiritual and religious values central to Nigerian life. Nigeria is a society where Christianity, Islam, and traditional spirituality play important roles in shaping identity and purpose. As such, clients may find it easier to engage in ACT when values such as faith, service to God and spiritual discipline are integrated into the therapeutic process. For a Christian client for example, kindness and faithfulness may be guiding values. Such adaptations can enhance the acceptability of digital ACT in Nigeria.

Globally, these interventions have shown they are effective. But their direct applicability to Nigeria is still limited. Adaptation in the Nigerian context must address locally prevalent issues such as trauma related to insurgency and kidnapping, economic stressors from widespread unemployment and poverty, and substance use disorders. The dual burden of trauma from widespread insecurity and rising substance abuse in Nigeria presents a unique clinical picture that digital CBT modules must be designed to address. Despite the growing interest in digital health solutions, locally validated digital CBT modules or culturally tailored ACT and EFT interventions have not yet been systematically developed for Nigeria. This highlights the need for research into how these psychotherapeutic innovations can be translated, adapted and tested in Nigerian cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic realities.

Use of mobile apps and teletherapy in delivering therapy

Mobile Apps: These apps have self-help elements, symptom control and psychoeducation. They, in most instances, have evidence-based psychotherapeutic concepts such as CBT and ACT in guided activities and interactive exercises. For example, Headspace and Calm are mobile apps that provide mindfulness and stress management tools grounded in ACT principles. CBT Thought Diary is an app that provides tools for tracking and restructuring negative thoughts. There are also other apps like Youper that integrate AI to deliver personalized mental health support through conversation-based interfaces.

Teletherapy: This involves delivering psychotherapy services through phone calls, video conferencing, or text-based platforms. This mode of therapy enables clients to connect with licensed therapist regardless of geographical location. It makes mental health care more accessible. Platforms like BetterHelp and Talkspace offer a convenient alternative to in-person therapy. Teletherapy has proven effective for a wide range of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, and trauma (Trombello et al., 2017; Giovanetti et al., 2022), offering flexibility and convenience for both therapists and clients (Maier et al., 2021; Gherson et al., 2023).

Current State of Digital Mental Health in Nigeria

As Nigeria is experiencing a gradual growth in digital technology, many solutions to mental health have come to life as a consequence of the growth in digital technology. From web-based support groups and awareness initiatives to culturally tailored social media campaigns (Goodwin et al., 2024), mental health self-assessment tools and stress management apps, to telehealth programs that incorporate mental health consultation within their health care delivery. Evidence of Nigeria’s slow build-up of digital mental health solutions still persists. Let us take a brief look at a homegrown innovation that is a step in the right direction to solving mental health issues in Nigeria.

Mentally Aware Nigeria Initiate (MANI) is a pioneering not-for-profit organization in Nigeria, empowering the youth to take ownership of their mental health through learning, support, and advocacy. It was started in 2016 and has since been a force to reckon with raising awareness of mental health. According to the organization itself on its website, since its inception, it has delivered over 123,000 free counselling sessions. As Nigeria’s foremost youth-focused mental health organisation, MANI boasts a powerful force of more than 1500 passionate volunteers that relentlessly work towards the cause of mental well-being among young people. It taps into Nigeria’s growing internet users by operating predominantly online and through social media in an attempt to reach a broad audience.

The major roles of MANI involve creating mental health awareness, online support groups, emergency helplines, building capacity and training, outreach, and policy change advocacy. MANI employs social media platforms such as Instagram, X (formerly Twitter), and Facebook for disseminating mental health educational material. In conducting awareness campaigns, MANI de-stigmatizes mental health issues, creates understanding, and fosters free exchange of conversation on matters of mental health. Virtual support groups, however, provide members with a platform to communicate safely their experience and connect to others with non-judgmental support without exposing themselves to stigma. Virtual support groups within the online forum are typically organized under the guiding expertise of skilled volunteers such as psychologists, mental health advocates, who refer individuals in crisis situations. However, with the exclusion of online virtual groups, MANI addresses crises through emergency helplines. They address crises such as suicidal ideation and Major Depressive Disorders. This is achieved through free, confidential helplines that connect individuals to trained counsellors. There are over one hundred counsellors working with MANI to attend to people who need mental health support. They provide virtual helplines that play a critical role in providing immediate support and referrals for further treatment. MANI is involved equally in other activities, but the focus of the example being given is to show instances of growth in Nigeria’s digital mental health space.

At this point, it is important to state that the impact of MANI has not been rigorously evaluated through published empirical studies even though it represents a crucial step forward. The organisation has reported the number of counselling sessions as 123,000 but that number is just a measure of output and not outcome. There is still the need for research using validated scales to measure the changes in user’s pre- and post-intervention situations. This evidence gap is a significant barrier to scaling such local initiatives.

Challenges to digital mental health adoption in Nigeria

Any conversation about the challenges to the Nigerian digital mental health space must necessarily begin with the underdeveloped mental health sector. The disparity between the availability of healthcare services and the demand for mental health services in Nigeria is huge. Notably, mental health is conspicuously absent from key health sector documents, suggesting a glaring lack of policy attention to mental health services, including digital interventions (Abdulmalik et al., 2016). Nigeria continues to face entrenched challenges in mental health policy development, funding, research, legislation, workforce training and integration into primary health care not minding the advances made in public health policy (Wada et al., 2021). So far, the mental health infrastructure in Nigeria remains woefully insufficient to cater to the needs of its vast population. A stark illustration of this shortfall is the sole neuro-psychiatric hospital serving over four million people in the Niger Delta region (Jack-Ide &Uys, 2013). Furthermore, a mere 9% of individuals with 12-month DSM-IV (the diagnostic standard at the time of the study) disorders received any form of mental health treatment, with virtually none receiving minimally adequate care (Gureje & Lasebikan, 2006). This overall lack of mental health infrastructure and services extends to the digital space as well.

Socio-Cultural Factors: There is a significant knowledge gap regarding the nature of mental disorders, which is further compounded by the pervasive stigma surrounding mental health issues (Gureje & Lasebikan, 2006). This may be because in many parts of the country, the inhabitants are not open to knowledge that might challenge their culture and religion. This drives them not to seek knowledge about mental health issue as some cultures and religions attribute mental disorders to supernatural beliefs. Research has consistently revealed that supernatural beliefs for mental disorders are widespread in Nigeria, with a significant proportion of Nigerians attributing mental illnesses to supernatural forces such as evil spirits, witchcraft, sorcery, or punishment from God (Labinjo et al., 2020; Ogunwale et al., 2023). This pattern is also evident among older adults, where stigma and cultural interpretations remain strong barriers to accessing mental health care (Malah et al., 2025). This context significantly influences different attitudes such as stigma towards mental health, and it creates barriers to seeking professional help. This significantly limits engagement with digital mental health services even where they are available.

It is not just a misconception about the causes of mental illness but also skepticism towards technology-based tools. Many Nigerians resist technology-based tools. Such resistance reflects a broader mistrust of nontraditional methods in mental health care. There are various cultural factors that play roles in shaping attitudes towards mental health services and technology adoption in Nigeria. For example, the predominantly Muslim population in northern Nigeria practices Islam as a complete way of life. According to Sinai et al. (2017), this cultural context can create resistance to new technologies in mental health care. This is especially the case where the new technologies are perceived as conflicting with the traditional beliefs and practices.

Japa Syndrome: One of the things very noticeable about Nigerians is that the condition of the country is driving the citizens out of the country in droves. This condition is what is referred to as brain drain. These push factors motivate Nigerians including health professionals to leave the country. However, there are also pull factors in developed countries that motivate Nigerians to choose these countries over Nigeria. These pull factors such as better living and working conditions, higher salaries, including opportunities for career growth, further encourage this migration (Adebayo & Akinyemi, 2021). The brain drain contributes to critical staff shortages in the healthcare sector, which directly affects mental health services (Kollar & Buyx, 2013).

The Digital Divide: This is the gap that exists between the people with steady access to digital technologies and those who do not (Furuholt & Kristiansen, 2007). This gap exists on different levels that include the global, national and individual levels (Furuholt & Kristiansen, 2007). This concept has evolved over time, initially focused on the accessibility of computers and the internet. Research has shifted towards examining skills, usage and outcomes related to digital technologies (van Dijk, 2006; Wei et al., 2011). It must be noted, however, that internet penetration in Nigeria is gradually on the rise. But it is still unevenly distributed and rural communities and economically marginalized segments remain underserved. These regions are likely to experience patchy network coverage (Eboibi, 2017; Olanrewaju et al., 2021). Low digital literacy among the majority of Nigerians challenges the effective utilization of digital mental health tools, widening the access gap. Another dimension of the digital divide worth mentioning is its gendered dimension. In some parts of the country, socio-cultural norms and economic disparities may limit women’s access to smartphones or private spaces to engage in teletherapy. This would potentially marginalize women from digital mental health resources.

Cultural and Regional Differences in Adoption: The cultural and regional diversity in Nigeria influences how digital mental health interventions may be perceived and adopted. For instance, mental health issues in the predominantly Muslim northern regions are mostly seen through religious or spiritual frameworks. Many individuals in this region seek guidance primarily from imams or traditional leaders. This is also observed among the Christians in the Southern region who seek guidance from their pastors. This reliance on faith-based authorities may lead to skepticism toward digital mental health platforms unless such tools are endorsed or integrated into religious structures. Collaboration with these religious leaders could improve the acceptability of digital platforms in a way that they would be seen as complementary rather than contradictory to faith-based approaches.

Additionally, some parts of the country are more urbanized and have higher exposure to technology. These parts tend to show greater openness towards tech-based solutions. Broader social and structural determinants, including inequality and poor welfare infrastructure, also shape patterns of digital access and mental health vulnerability (Oyebamiji et al., 2025). However, cultural stigma around mental health persists even in these urban areas. This necessitates public awareness campaigns to encourage utilization.

The Potential for Harm: While there is a lot of potential for enhancing mental health treatment through digital technologies, there is also worth exploring the potential negative effects of more internet usage. A study on the relationship between internet addiction and psychological well-being among university students revealed a significant correlation between the two. This indicates the necessity of a balanced strategy towards the mental health application of digital technology, focusing on digital literacy and ethical use to prevent the risk of internet addiction as well as other adverse consequences. It further puts emphasis on the need to educate users of appropriate use of technology for mental health.

Ethical and Data Security Concerns: The adoption of online mental health platforms is accompanied by serious ethical issues, particularly regarding security and privacy of data. Many Nigerians distrust technology-based tools as Nigeria’s cybersecurity infrastructure and data protection regulations remain underdeveloped. The underdeveloped state of the data protection regulations increases the risk of data breaches, which undermines public trust in digital platforms. For example, the Nigerian banking industry, despite being recognized as one of the top performers in Africa, has shown inconsistencies in information governance, especially in data management. This lack of robust information governance has contributed to the vulnerability of banks to data breaches. This shows that Nigerians have experienced a significant lot in data breaches in the hands of their commercial banks. These experiences in data breaches have been transferred to other areas not just banks. So, with their data breaches experiences in the hands of the banks, it seems reasonable that Nigerians would also be wary of any platform that would collect their data. There are also concerns about whether these platforms comply with ethical guidelines and cultural norms, particularly in the absence of robust oversight and regulation.

Outside general data privacy, there are other complexities to be confronted for the ethical adoption of digital mental health in Nigeria. AI tools like diagnostic chatbots are mainly trained on Western data. This will most likely fail to recognize culturally-specific presentations of mental distress in Nigerians. This is mostly about algorithmic bias which poses a significant risk. Also, obtaining verifiable informed consent in the digital space of Nigerian mental health would require going beyond text-heavy forms. This necessitates different modes of communication including audio recorded explanations in local languages. With this mobile phone penetration, there is a significant opportunity to use mobile-based solutions to deliver mental health care. Both rural and urban populations rely on mobile phones, making them an accessible medium for teletherapy, mental health apps, and SMS-based mental health support. In particular, apps can be designed to offer self-help tools, provide access to professional consultations, and deliver mental health education. SMS-based services can be a low-cost way to reach individuals in areas with limited internet access.

Training mental health professionals in digital tools

Mental health professionals should be empowered with the skills to use digital tools. This aligns with global recommendations emphasizing that clinical psychology training should evolve to prioritize prevention, innovation, and technological competence as essential tools for reducing mental health burdens (Berenbaum et al., 2021). Research indicates a significant IT skill gap among both healthcare and psychology trainees in Nigeria and beyond (Adeleke et al., 2015; Dada & Jagboro, 2015; Hagstrom & Maranzan, 2019; Alalade et al., 2024). So, training programs should equip these professionals with the ability to use teletherapy platforms, manage online consultations, and employ AI-based diagnostic tools.

Collaborating with tech startups and international organizations

Nigeria’s thriving tech ecosystem provides fertile ground for collaborations between mental health stakeholders and tech startups. The recent Federal Republic of Nigeria (2022) provides an enabling legal and policy framework that supports innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation by promoting collaboration between government, academia, and the private sector. Leveraging this policy environment can accelerate the integration of technology-driven mental health solutions into national innovation agendas. For instance, Nigeria has developed its own version of Silicon Valley, known as “Yabacon Valley,” located in the Yaba district of Lagos, which showcases the nation’s commitment to fostering digital innovation. Strategic partnerships between mental health professionals and tech companies can therefore produce locally relevant, multilingual, and accessible mental health platforms aligned with the Startup Act’s goals of sustainable digital inclusion.

Nigeria’s thriving tech ecosystem provides fertile ground for collaborations between mental health stakeholders and tech startups. It is interesting to note that Nigeria has developed its own version of Silicon Valley, known as “Yabacon Valley” or “Nigeria’s Silicon Valley,” located in the Yaba district of Lagos. This emerging tech hub showcases Nigeria’s efforts to foster innovation and entrepreneurship in the digital economy. The foregoing is to establish that Nigeria indeed has a thriving tech ecosystem. That being the case, there should be partnerships between mental health professionals and the tech companies. These partnerships can result in solutions that are tailored for the local population, such as platforms available in multiple Nigerian languages. Collaboration with global agencies can offer funding, technical support, and international standards of excellence to produce digital mental health interventions of international quality while being culturally responsive. For instance, programs that incorporate digital elements into primary health care or those that raise awareness in the community through campaigns should be highly prioritized.

Inclusive and equitable design

The design of digital mental health solutions must be intentional bearing in mind that equity and accessibility should be at the center to avoid worsening existing disparities. This would require that developers include features such as voice-based interfaces and audio content for users with low literacy. This would ensure compatibility with screen readers for the visually impaired and creating data-light applications for areas with poor connectivity. Moreso, the design must consider socio-economic barriers like the fact that women in some parts of the country may lack private spaces for teletherapy sessions. Organisations representing people with disabilities and women’s groups should be partnered with to guide this inclusive design process and ensure these tools reach the most marginalized populations.

Limitations of the Review and Future Directions

While this paper provides a detailed overview of the integration of psychotherapeutic innovations and digital technology in the mental health care system of Nigeria, several limitations exist. In the first place, the review is purely non-empirical as it relies on existing literature. This implies that it may not fully capture the real-time complexities and user experiences of digital mental health platforms in Nigeria. Furthermore, there is limited locally published research on the effectiveness of digital interventions within diverse Nigerian cultural and socioeconomic settings. The cited platforms and the efficacy studies are largely from other countries that may be classified as high-income countries. Their outcomes may not be directly transferable to a country like Nigeria.

Future studies should focus on conducting community-based, empirical studies that will assess the feasibility, acceptability, and outcomes of digital mental health interventions tailored to Nigerian populations. Future empirical and community-based studies should investigate how variables such as culture, religion, gender, literacy, and rurality affect user engagement and mental health outcomes. Additionally, longitudinal studies are necessary to assess the sustained impact of these digital interventions over time. Policy-oriented should explore how to integrate digital mental health into national mental health frameworks. There is also the need for future studies to explore hybrid models that combine community-based psychosocial support with digital tools. This will ensure culturally grounded and technologically enabled care.

The integration of psychotherapeutic creativity with technology has the potential to transform Nigeria’s mental health landscape. Technologies such as teletherapy, AI-based interventions, and cell phone health applications can offer scalable and low-cost interventions more applicable to Nigeria’s specific cultural and socioeconomic environment.

Collaboration is necessary to realize this potential. Researchers need to set evidence-based studies as a priority to quantify the impact of digital interventions. Clinicians need to adopt digital tools but adhere to ethical practices, such as cultural competency and data privacy. All of these stakeholders can collectively bring a paradigm shift to mental health treatment that constructs a future where technology bridges gaps, enhances outcomes, and promotes national mental well-being.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: C. I. Onyemaechi, A. O. Onwudiwe; Data collection: S. C. Achebe, O. A. Ugwu, C. I. Onyemaechi, P. O. Philip; Analysis and interpretation of results: O. A. Ugwu, P. O. Philip; Draft manuscript preparation: A. O. Onwudiwe, C. I. Onyemaechi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable; all information presented is derived from previously published literature as cited in the manuscript

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Abdulmalik, J., Kola, L., & Gureje, O. (2016). Mental health system governance in Nigeria: Challenges, opportunities and strategies for improvement. Global Mental Health, 3(Suppl 2), e9. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2016.2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Abdulmalik, J., Olayiwola, S., Docrat, S., Lund, C., Chisholm, D. et al. (2019). Sustainable financing mechanisms for strengthening mental health systems in Nigeria. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13(1), 2581. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0293-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Adaigbe, E. B., Onyemaechi, C. I., Izuchukwu, C., Onuorah, A., Nwobi, O. B. et al. (2025). Artificial intelligence and the practice of psychology in Nigeria. Ojukwu Journal of Psychological Services, 1(2), 86–109. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15096265 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Adebayo, A., & Akinyemi, O. O. (2021). What are you really doing in this country?: Emigration intentions of nigerian doctors and their policy implications for human resource for health management. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 23(3), 1377–1396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00898-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Adeleke, I. T., Adebisi, A. A., Lawal, A. H., & Adio, R. A. (2015). Information technology skills and training needs of health information management professionals in Nigeria: A nationwide study. Health Information Management Journal, 44(1), 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/183335831504400104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Agras, W. S., & Bohon, C. (2021). Cognitive behavioral therapy for the eating disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 17(1), 417–438. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-110907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Agwu, E. M., & Carter, A. L. (2014). Mobile phone banking in Nigeria: Benefits, problems and prospects. International Journal of Business and Commerce, 3(6), 50–70. [Google Scholar]

Alalade, O., Saka, A. B., Njuangang, S., Dauda, J. A., & Ajayi, S. O. (2024). An in-depth analysis of facility management approaches in Nigeria’s ailing healthcare sector. Journal of Facilities Management, 23(4), 667–684. https://doi.org/10.1108/jfm-12-2023-0123 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

American Psychiatric Association (2023). Digital mental health 101: Resource document. Retrieved from: https://www.psychiatry.org/getattachment/b250c6ff-d1f5-4c4f-8ad1-f478fba5773d/Resource-Document-Digital-Mental-Health-101.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Berenbaum, H., Washburn, J. J., Sbarra, D., Reardon, K. W., Schuler, T. et al. (2021). Accelerating the rate of progress in reducing mental health burdens: Recommendations for training the next generation of clinical psychologists. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 28(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Boness, C. L., Votaw, V. R., Witkiewitz, K., Mchugh, R. K., Schwebel, F. J et al. (2023). An evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorder: A systematic review and application of the society of clinical psychology criteria for empirically supported treatments. Clinical Psychology, 30(2), 129–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Brook, R. H. (2017). Should the definition of health include a measure of tolerance? The Journal of the American Medical Association, 317(6), 585. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.14372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Dada, J. O., & Jagboro, G. O. (2015). Core skills requirement and competencies expected of quantity surveyors: Perspectives from quantity surveyors, allied professionals and clients in Nigeria. Construction Economics and Building, 12(4), 78–90. https://doi.org/10.5130/ajceb.v12i4.2808 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eberle, J. W., Daniel, K. E., Baee, S., Silverman, A. L., Lewis, E. et al. (2024). Web-based interpretation bias training to reduce anxiety: A sequential, multiple-assignment randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 92(6), 367–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Eboibi, F. E. (2017). A review of the legal and regulatory frameworks of Nigerian cybercrimes act 2015. Computer Law & Security Review, 33(5), 700–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2017.03.020 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Federal Republic of Nigeria (2022). Nigeria Startup Act, 2022. Official Gazette No. 164, Vol. 109. Retrieved from: https://uhy-ng-maaji.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/THE-NIGERIA-STARTUP-ACT-2022.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Furuholt, B., & Kristiansen, S. (2007). A rural-urban digital divide? The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 31(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2007.tb00215.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gherson, S., Tripp, R., Goudelias, D., & Johnson, A. M. (2023). Rapid implementation of teletherapy for voice disorders: Challenges and opportunities for speech-language pathologists. Journal of Voice, in press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2023.06.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Giovanetti, A. K., Nelson, E.-L., Ilardi, S. S., & Punt, S. E. W. (2022). Teletherapy versus in-person psychotherapy for depression: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Telemedicine and E-Health, 28(8), 1077–1089. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Goodwin, A. K. B., McNulty, C., Hanebutt, R., & Schaeffer, C. M. (2024). Social media recruitment of Black adolescents with internalizing concerns into a mental health help-seeking study. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 10(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000413 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gureje, O., & Lasebikan, V. O. (2006). Use of mental health services in a developing country. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0001-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hagstrom, S. L., & Maranzan, K. A. (2019). Bridging the gap between technological advance and professional psychology training: A way forward. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 60(4), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000186 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hofmann, S. G., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2007). Acceptance and mindfulness-based therapy: New wave or old hat? Clinical Psychology Review, 28(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jack-Ide, I. O., & Uys, L. (2013). Barriers to mental health services utilization in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria: Service users’ perspectives. Pan African Medical Journal, 14, 159. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2013.14.159.1970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jones, A. A., Strong-Jones, S., Bishop, R. E., Brant, K., Owczarzak, J. et al. (2024). The impact of family systems and social networks on substance use initiation and recovery among women with substance use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 38(8), 850–859. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0001007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kohn, R., Saxena, S., Levav, I., & Saraceno, B. (2004). The treatment gap in mental health care. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 82(11), 858–866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Kola, L., Abiona, D., Adefolarin, A. O., & Ben-Zeev, D. (2021). Mobile phone use and acceptability for the delivery of mental health information among perinatal adolescents in Nigeria: Survey study. JMIR Mental Health, 8(1), e20314. https://doi.org/10.2196/20314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kollar, E., & Buyx, A. (2013). Ethics and policy of medical brain drain: A review. Swiss Medical Weekly, 143, w13845. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2013.13845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Labinjo, T., Serrant, L., Ashmore, R., & Turner, J. (2020). Perceptions, attitudes and cultural understandings of mental health in nigeria: A scoping review of published literature. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23(7), 606–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1726883 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maier, C. A., Morgan-Sowada, H., & Riger, D. (2021). It’s splendid once you grow into it: Client experiences of relational teletherapy in the era of COVID-19. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 47(2), 304–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Malah, O. Z., Onwudiwe, A. O., Imade, B., Titilola, S. A., Olaniyi, A. O. et al. (2025). Stigma and cultural barriers to mental health care with the geriatric population in Nigeria. Journal of Disease and Global Health, 18(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/10.56557/jodagh/2025/v18i29505 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mechanic, O. J., Persaud, Y., & Kimball, A. B. (2022). Telehealth systems. Weston, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459384/. [Google Scholar]

Morgan, G. (2009). WHO should redefine health? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(6), 419. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.084731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Nigerian Communications Commission (2023). 2023 subscriber/network performance report. Policy, Competition and Economic Analysis Department. Retrieved from: https://www.ncc.gov.ng. [Google Scholar]

Nwobi, O. B., Onyemaechi, C. I., Izuchukwu, C., Onuorah, A., Adaigbe, E. et al. (2025). Integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in the practice of clinical psychology: The way forward in nigeria. Ojukwu Journal of Psychological Services, 1(2), 44–63. Retrieved from: https://psyservicesjournal.org.ng/wp-content/uploads/journal/published_paper/volume-1/issue-2/ZX2ysvSV.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Ogbeiwi, O., Khan, W., Stott, K., Zaluczkowska, A., & Doyle, M. (2024). A systematic review of digital storytelling as psychotherapy for people with mental health needs. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 34(2), 115–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000325 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ogunwale, A., Bifarin, O., & Fadipe, B. (2023). Indigenous mental healthcare and human rights abuses in Nigeria: The role of cultural synchronicity and stigmatization. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1122396. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1122396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Olanrewaju, G. S., Adebayo, S. B., Omotosho, A. Y., & Olajide, C. F. (2021). Left behind? The effects of digital gaps on e-learning in rural secondary schools and remote communities across Nigeria during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 2(4), 100092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Olatunji, B. O., Cisler, J. M., & Deacon, B. J. (2010). Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: A review of meta-analytic findings. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 33(3), 557–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Oyebamiji, H. I., Ani, N. C., Dahunsi, A. N., Onwudiwe, A. O., Abdulganeey, I. B., et al. (2025). Unseen struggles: Social determinants and structural inequalities shaping elderly mental health in Nigeria. Journal of Disease and Global Health, 18(2), 78–87. https://doi.org/10.56557/jodagh/2025/v18i29490 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Palla, G., Giannini, A., Guevara, M. M. M., Caretto, M., Simoncini, T. et al. (2021). Impact of polycystic ovarian syndrome, metabolic syndrome, and obesity on women’s health (pp. 149–160). Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63650-0_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sinai, I., Khan, M., Daroda, R., Anyanti, J., & Oguntunde, O. (2017). Demand for women’s health services in Northern Nigeria: A review of the literature. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 21(2), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2017/v21i2.11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Statista (2025). Number of Internet users in selected countries in Africa 2025. Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/505883/number-of-internet-users-in-african-countries/. [Google Scholar]

Trombello, J. M., Sánchez, A. C., Eidelman, S. L., Sánchez, K. E., Cecil, A. et al. (2017). Efficacy of a behavioral activation teletherapy intervention to treat depression and anxiety in primary care VitalSign6 program. The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 19(5), 17m02146. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.17m02146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Vaessen, T., Steinhart, H., Batink, T., Klippel, A., Van Nierop, M. et al. (2019). ACT in daily life in early psychosis: An ecological momentary intervention approach. Psychosis, 11(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2019.1578401 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2006). Digital divide research, achievements and shortcoming. Poetics, 34(4–5), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wada, Y. H., Rajwani, L., Anyam, E., Karikari, E., Njikizana, M. et al. (2021). Mental health in Nigeria: A neglected issue in public health. Public Health in Practice, 2(4), 100166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2021.100166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wei, K.-K., Chan, H. C., Tan, B. C. Y., & Teo, H.-H. (2011). Conceptualizing and testing a social cognitive model of the digital divide. Information Systems Research, 22(1), 170–187. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1090.0273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

World Health Organization (2006). Building foundations for eHealth: Progress of member states (Global Observatory for eHealth series, Vol. 3). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43599. [Google Scholar]

World Health Organization (2011). mHealth: New horizons for health through mobile technologies (Global Observatory for eHealth series, Vol. 3). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44607. [Google Scholar]

World Health Organization (2022). Mental health: Strengthening our response. Retrieved from: https://who-dev5.prgsdev.com/m/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response. [Google Scholar]

World Health Organization Interim Commission (1948). Summary report on proceedings, minutes and final acts of the International Health Conference held in New York from 19 June to 22 July 1946 (Official Records of the World Health Organization No. 2). United Nations/World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85573. [Google Scholar]

Young, A. S., Niv, N., Olmos-Ochoa, T. T., Cohen, A. N., Goldberg, R. W. et al. (2019). Mobile phone and smartphone use by people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 71(3), 280–283. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201900203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhang, C.-Q., Leeming, E., Hagger, M. S., Chung, P.-K., Hayes, S. C. et al. (2018). Acceptance and commitment therapy for health behavior change: A contextually-driven approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2350. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools