Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Additive Manufacturing of Polymer Metamaterials for Vibration Isolation: A Review

1 School of Transportation and Logistics Engineering, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, 430070, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Materials Processing and Die & Mould Technology, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, 430074, China

* Corresponding Author: Lei Yang. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(2), 307-338. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.062620

Received 23 December 2024; Accepted 03 April 2025; Issue published 14 July 2025

Abstract

Vibration isolation is vital in engineering machinery, as it not only seriously affects the service life of machine components but also reduces the operating efficiency. Recently, metamaterials have been proposed for customized vibration-isolation needs through various functional designs. As a synthetic material, polymer materials have the advantages of good elasticity, low density, high specific strength, good corrosion resistance and easy processing, making it an ideal raw material for vibration-isolation metamaterials. At the same time, the rapid development of additive manufacturing (AM) provides a feasible method for preparing polymeric vibration-isolation metamaterials with complex structures. In this paper, we systematically analyze the vibration-isolation mechanism of metamaterials, review the applications of metamaterials in vibration isolation and the research on polymer metamaterials, and survey the AM process methods for polymer metamaterials. Finally, the prospects and directions for the development of polymer vibration-isolation metamaterials are envisioned, providing new ideas for further research on polymer metamaterials in the field of vibration isolation.Keywords

Since the advent of mechanical structures, vibrations have been a common issue in mechanical systems, often causing accelerated wear, reduced efficiency, and increased operational costs [1]. From aerospace to manufacturing, the demand for effective vibration isolation has grown increasingly urgent, especially as mechanical systems become more complex and performance demands rise. Traditional vibration-isolation methods (e.g., passive damping materials) often fail to provide sufficient efficiency or adaptability to respond to changing operational conditions [2]. This limitation has driven the search for more advanced solutions.

Metamaterials, meticulously designed with properties uncommon in natural materials, represent a new class of artificial composite engineering materials [3]. By programming and arranging internal microstructures, these materials exhibit unique properties and physical effects not found in natural materials allowing them to manipulate waves, including mechanical, sound, or electromagnetic waves [4]. This adaptability enables customized vibration-isolation systems fine-tuned to specific frequencies and conditions [5,6]. Additionally, metamaterials, often referred to as multifunctional materials, can be tailored to exhibit unique electromagnetic, optical [7], acoustic, thermal [8], and mechanical properties [9], enabling diverse industrial applications. For example, structural topology optimization has been used to create metamaterials with a negative Poisson’s ratio [10–12], demonstrating excellent performance in indentation resistance [13–15], lightweight design, impact resistance, energy absorption, and vibration damping [16]. These characteristics position metamaterials as a cutting-edge solution to modern vibration challenges.

Among various types of metamaterials, polymer-based metamaterials stand out due to their inherent advantages, including low density, high elasticity, and ease of processing [17,18]. These properties make polymers ideal candidates for developing vibration-isolation metamaterials, especially in applications where lightweight and cost-effective solutions are critical [19]. Moreover, the versatility of polymers enables a wide range of functional designs, facilitating the creation of efficient vibration-isolation structures [20].

The rapid advancements in AM have further enhanced the potential of polymer-based metamaterials [21]. By precisely fabricating complex and customized structures, AM facilitates the creation of polymer-based metamaterials optimized for vibration isolation [22]. This technology offers unprecedented design flexibility, enabling the production of geometries and features that are difficult or impossible to achieve using traditional manufacturing methods. In addition to polymers, the development of AM polymer laminated composites [23] has also provided great convenience for fields such as vibration isolation, sensing [24], and biomedicine [25].

This paper provides a comprehensive review of recent advances in polymer-based metamaterials for vibration isolation. It first discusses the types of metamaterials and their vibration-isolation mechanisms, followed by a review of the current research on polymer-based metamaterials. It then summarizes AM techniques suitable for complex polymer structures. Subsequently, it evaluates the latest advancements in polymers for each AM technique. Finally, this review offers specific insights into the prospects and future directions of applying polymer-based metamaterials in vibration isolation.

This review analyzed peer-reviewed articles from 1998 to 2024, sourced from Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and PubMed. Using keywords like “polymer metamaterials,” “vibration isolation,” and “AM,” an initial screening of 1451 papers narrowed the selection to 160 relevant studies. Only AM-fabricated polymer metamaterials with vibration testing data were included, while theoretical or non-polymer studies were excluded. Data extraction covered materials, AM methods, structural designs, and damping performance for a comprehensive analysis.

2 Vibration-Isolation Principles of Metamaterial

Metamaterials manipulate wave propagation through three primary mechanisms: phononic crystals, local resonance, and energy dissipation. Each mechanism is analyzed below.

2.1 Vibration-Isolation Mechanism of Metamaterials

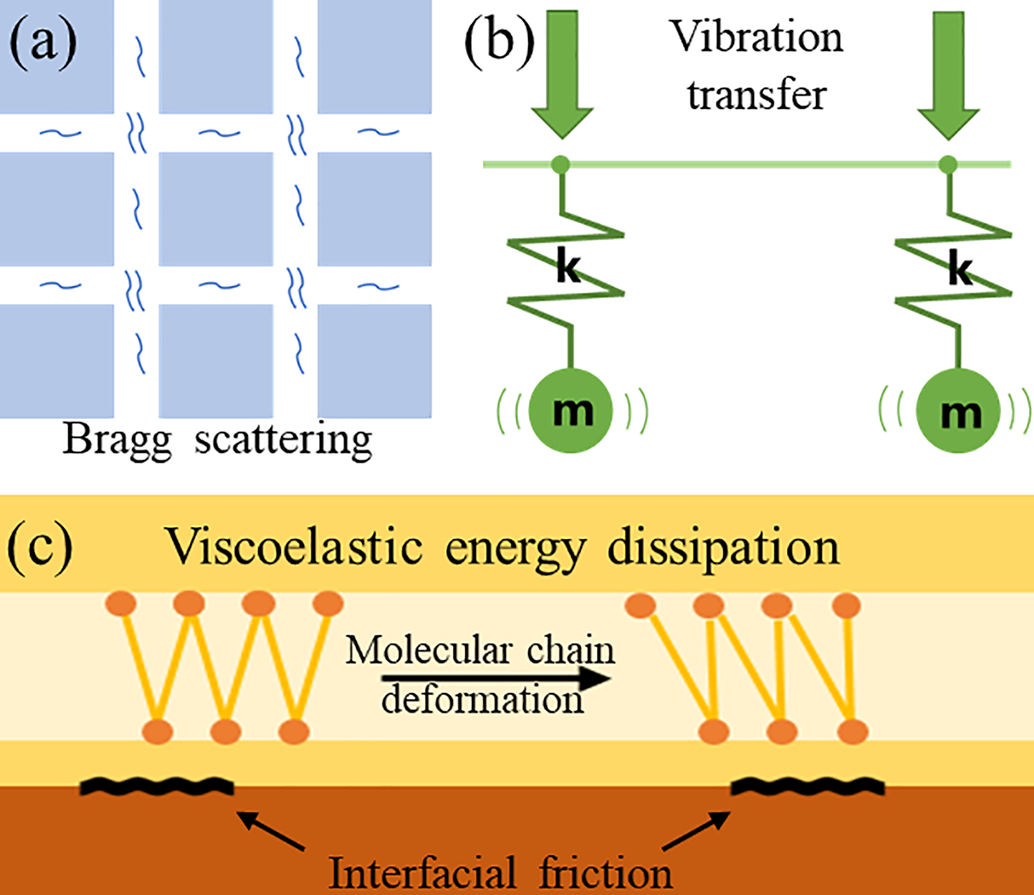

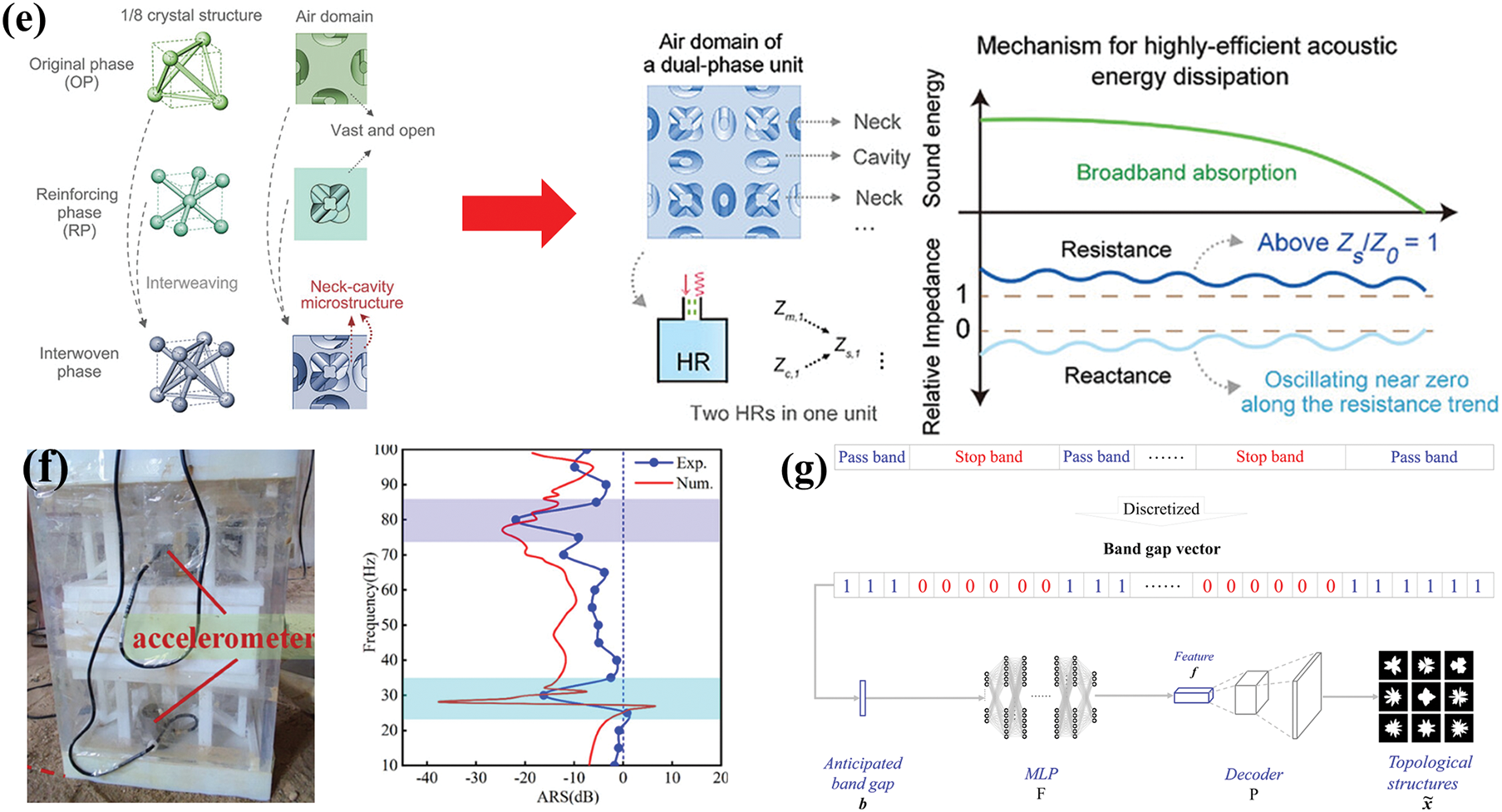

The vibration attenuation capability of metamaterials stems from their precise control over wave behavior, primarily through mechanisms of local resonance, phononic crystals, and energy dissipation [26,27]. These principles enable effective manipulation of the propagation path, frequency range, and phase state of elastic or acoustic waves, thereby suppressing or isolating vibrations. In practical applications, these mechanisms typically rely on unique microstructural designs and optimized material properties, demonstrating exceptional vibration-isolation performance [28,29]. Fig. 1 shows three vibration-isolation mechanisms: the phononic crystal effect from periodic structures, resonant units for local resonance, and two energy dissipation mechanisms. The fundamental principles and characteristics of these three mechanisms are discussed below.

Figure 1: Schematic diagrams of three vibration isolation mechanisms. (a) Periodically arranged phononic crystals, (b) Resonance unit consisting of mass-spring, (c) Viscoelastic energy dissipation and interfacial friction dissipation

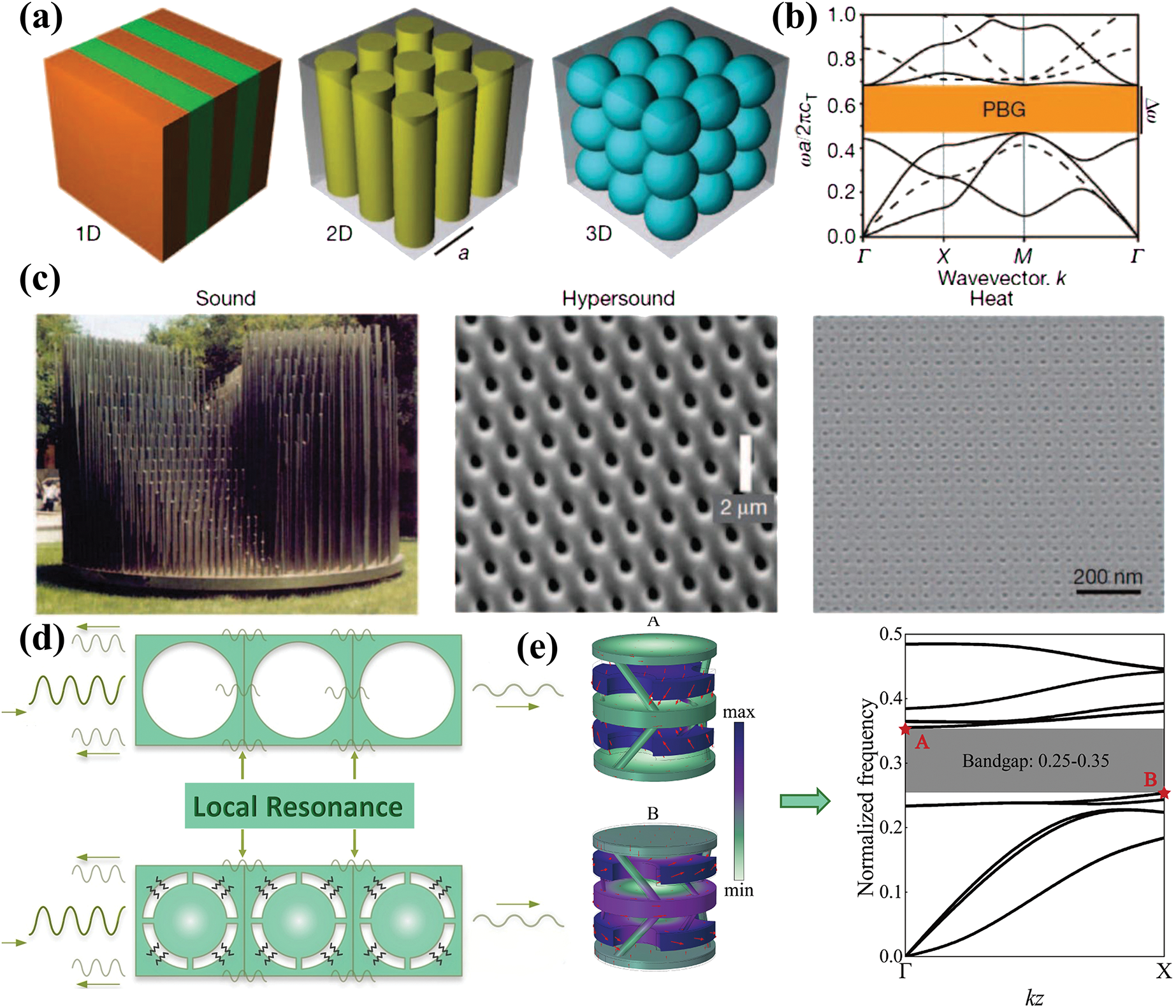

The vibration attenuation mechanism of phononic crystals is based on their periodic structures and Bragg scattering. When elastic or acoustic waves encounter the periodic heterostructures of a phononic crystal [34], the interference between scattered waves and incident waves generates bandgaps within specific frequency ranges, where wave propagation is prohibited (as shown in Fig. 2a,b) [30]. The essence of the Bragg scattering mechanism lies in the destructive phase interference that occurs when the wavelength matches the periodicity of the crystal structure, thereby blocking wave propagation [28].

Figure 2: Vibration-isolation mechanisms and several typical applications (a) Representation of phononic crystals, [30] (Copyright 2020, with permission from Elsevier), (b) Dispersion curves [30] (Copyright 2020, with permission from Elsevier), (c) examples of phononic crystal efficiency at different wavelength scales [30] (Copyright 2020, with permission from Elsevier), (d) Schematic of local resonance, (e) Band gap induced by a hand-shaped resonator [31] (Copyright 2024, with permission from Elsevier), (f) Energy dissipation system for vibration isolation based on friction and damping [32] (Copyright 2021, with permission from Elsevier), (g) Nonlinear vibration isolation system based on spring damping [33] (Copyright 2024, with permission from Elsevier)

The position and width of the bandgap are determined by the geometric dimensions of the periodic structure, the material properties, and the arrangement of the scatterers within the crystal. By adjusting these parameters, the bandgap can be designed to cover the desired frequency range [35], enabling effective vibration isolation and suppression. Fig. 2c demonstrates the application of phononic crystal bandgap at different wavelength scales [30]. Additionally, since Bragg scattering depends on the ratio of the structure’s periodicity to the wavelength, phononic crystals are more suited for high-frequency vibration attenuation compared to local resonance. This characteristic makes phononic crystals widely applicable in high-frequency vibration isolation, acoustic filtering, and wave energy control, providing a robust theoretical and practical foundation for the design of vibration-isolation metamaterials. While phononic crystals excel in high-frequency attenuation, their limitations in low-frequency applications necessitate complementary mechanisms, as discussed in the following subsection on local resonance.

Local resonance attenuates vibrations through interactions between embedded resonant units and elastic waves [36]. As shown in Fig. 2d, when external elastic waves excite these resonant units, they undergo strong localized resonance within specific frequency ranges, coupling with the propagating waves [13]. This coupling effect significantly dissipates or confines wave energy [37], forming a local resonance bandgap that prevents wave propagation within the targeted frequency range (Fig. 2e) [38]. The vibration of the resonant units induces destructive interference with the elastic waves through reverse coupling, disrupting wave phases and substantially reducing their energy [39,40].

The frequency position and width of the local resonance bandgap are primarily governed by the mass, stiffness, and damping properties of the resonant units [41,42]. Unlike the Bragg scattering mechanism, which relies on the wavelength matching the structural periodicity, local resonance can create bandgaps even when the wavelength is much larger than the unit structure’s scale [43,44]. This allows local resonance to exhibit superior wave attenuation capabilities in the low-frequency range [45]. Fig. 2e demonstrates the bandgap performance of a hand-type resonator in the low-frequency range [31]. By optimizing the properties of the resonant units, the bandgap can be finely tuned to meet specific vibration-isolation requirements [43,44]. This characteristic renders local resonance highly valuable for applications in low-frequency vibration isolation and noise control.

To provide a cohesive understanding of energy dissipation mechanisms in metamaterials, it is essential to examine how internal material properties and interface interactions contribute to vibrational energy attenuation. Viscoelastic dissipation focuses on the intrinsic molecular behavior of materials under dynamic loading, while interfacial friction dissipation emphasizes energy loss caused by relative motion at material boundaries [46]. Together, these mechanisms offer complementary pathways for energy dissipation [47], playing a crucial role in enhancing the vibration-isolation performance of metamaterials.

The mechanism of viscoelastic dissipation relies on the molecular motion characteristics of the material [48]. Under external forces, viscoelastic materials exhibit both elastic and viscous behaviors, and this principle can apply to vibration and noise control [49]. The spring damping model shown in Fig. 2f,g [32,33], the elastic component corresponds to the reversible deformation of molecular chains, which stores energy, while the viscous component corresponds to the relative sliding or internal friction of molecular chains, leading to energy dissipation in the form of heat [50]. When the frequency of vibration loading increases, the molecular chains in the viscoelastic material fail to fully follow the external force variation, resulting in hysteresis. This phase lag between stress and strain directly causes energy loss [51]. Moreover, the time-dependent nature of viscoelastic properties enables these materials to absorb and attenuate dynamic vibrational energy effectively [51].

The mechanism of interfacial friction dissipation arises from relative movement at the material interfaces (Fig. 2f) [32]. As vibrations propagate through layered or composite metamaterials, microscopic sliding or separation occurs at the interfaces between different materials, generating frictional forces [52]. The work done by these frictional forces dissipates mechanical energy as heat. Additionally, interfacial friction dissipation is often accompanied by wave scattering effects. Discontinuities at the interfaces alter the propagation path and energy distribution of the waves, further reducing their transmission strength [53]. The efficiency of this dissipation mechanism depends on the interfacial contact conditions, such as surface roughness [54], interface stiffness, and friction coefficients [55]. These parameters interact to influence the overall attenuation of vibrational energy.

3 Synergistic Design of Polymer Metamaterials for Vibration Isolation

Polymer-based metamaterials have emerged as a promising solution for vibration isolation due to their unique combination of viscoelastic damping [56–58], lightweight design [59], and compatibility with additive manufacturing (AM). However, their performance hinges on a synergistic interplay between material properties, structural geometry, and AM process capabilities.

3.1 Material-Structure-Performance Relationships in AM-Fabricated Metamaterials

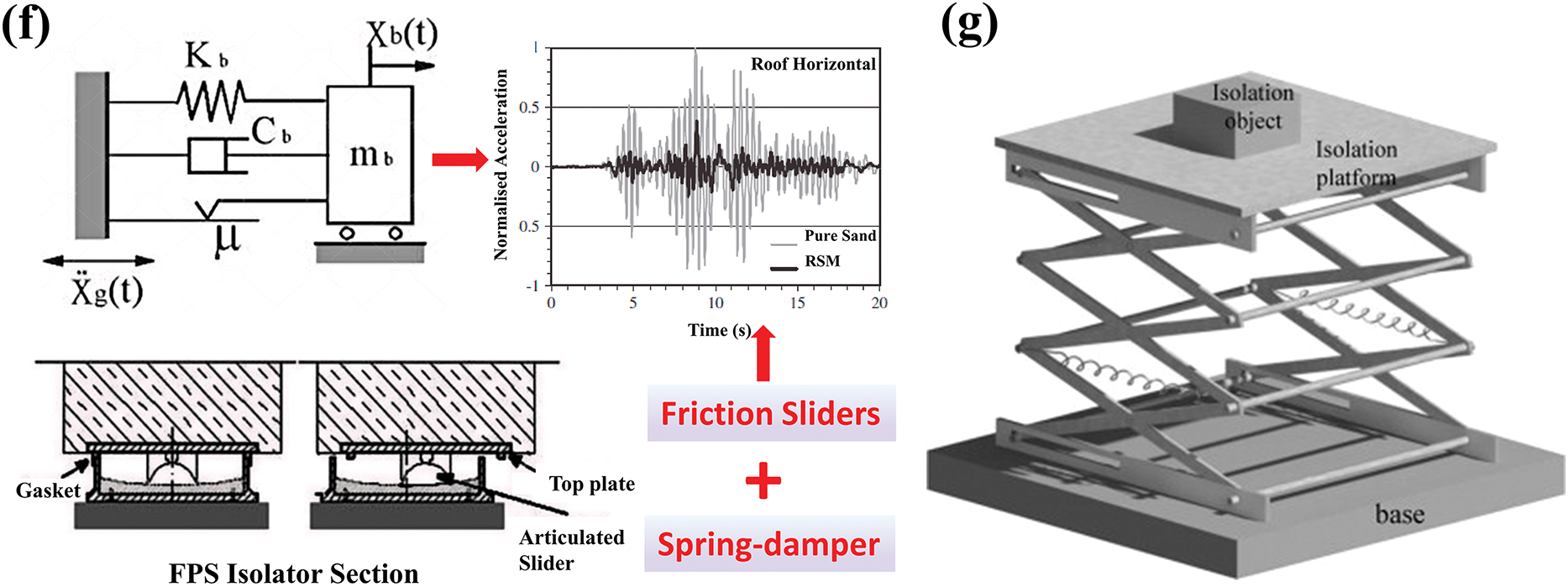

The interplay between AM processes and material properties introduces critical trade-offs. For instance, FDM achieves multi-material integration (Fig. 3c), combining rigid PLA frameworks with TPU damping layers for hybrid honeycombs [60]. Material jetting’s (MJ’s) reliance on photopolymers limits thermal stability, as seen in tricycle suspension systems where viscoelastic absorbers degraded above 80°C [61]. Similarly, selective laser sintering (SLS) of PA12 lattices achieves high structural integrity (15–20 MPa compressive strength) but suffers from 15%–20% damping loss due to residual porosity, underscoring the need for post-processing or hybrid designs.

Figure 3: Applications of polymer vibration-isolation metamaterials (a) hierarchical honeycomb structure for wave attenuation [59] (Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier), (b) band gaps of negative Poisson’s ratio acoustic metamaterials [13] (Copyright 2022, with permission from Elsevier), (c) PLA-TPU composite polymer metamaterials [60] (Copyright 2022, with permission from Elsevier), (d) band gap characteristics of lattice structures [15] (Copyright 2017, with permission from American Chemical Society), (e) efficient sound energy dissipation mechanism [57] (Copyright 2024, with permission from John Wiley and Sons), (f) seismic metamaterial barrier and isolation mechanism [64] (Copyright 2024, with permission from John Wiley and Sons), (g) band gap manipulation technology [30] (Copyright 2020, with permission from Elsevier)

These examples illustrate how AM processes dictate not only manufacturability but also functional performance. VP’s ultra-high resolution enables PDMS phononic crystals (Fig. 3d) with 200 μm periodicity for high-frequency isolation (2.5–5 kHz) [30], while FDM’s scalability facilitates meter-scale TPU structures for low-frequency applications, albeit with anisotropic damping (20% reduction along the Z-axis) [62]. By aligning material selection, structural design, and AM capabilities, this synergy unlocks unprecedented opportunities for customized vibration control, while highlighting the necessity of process-aware co-design to mitigate inherent limitations.

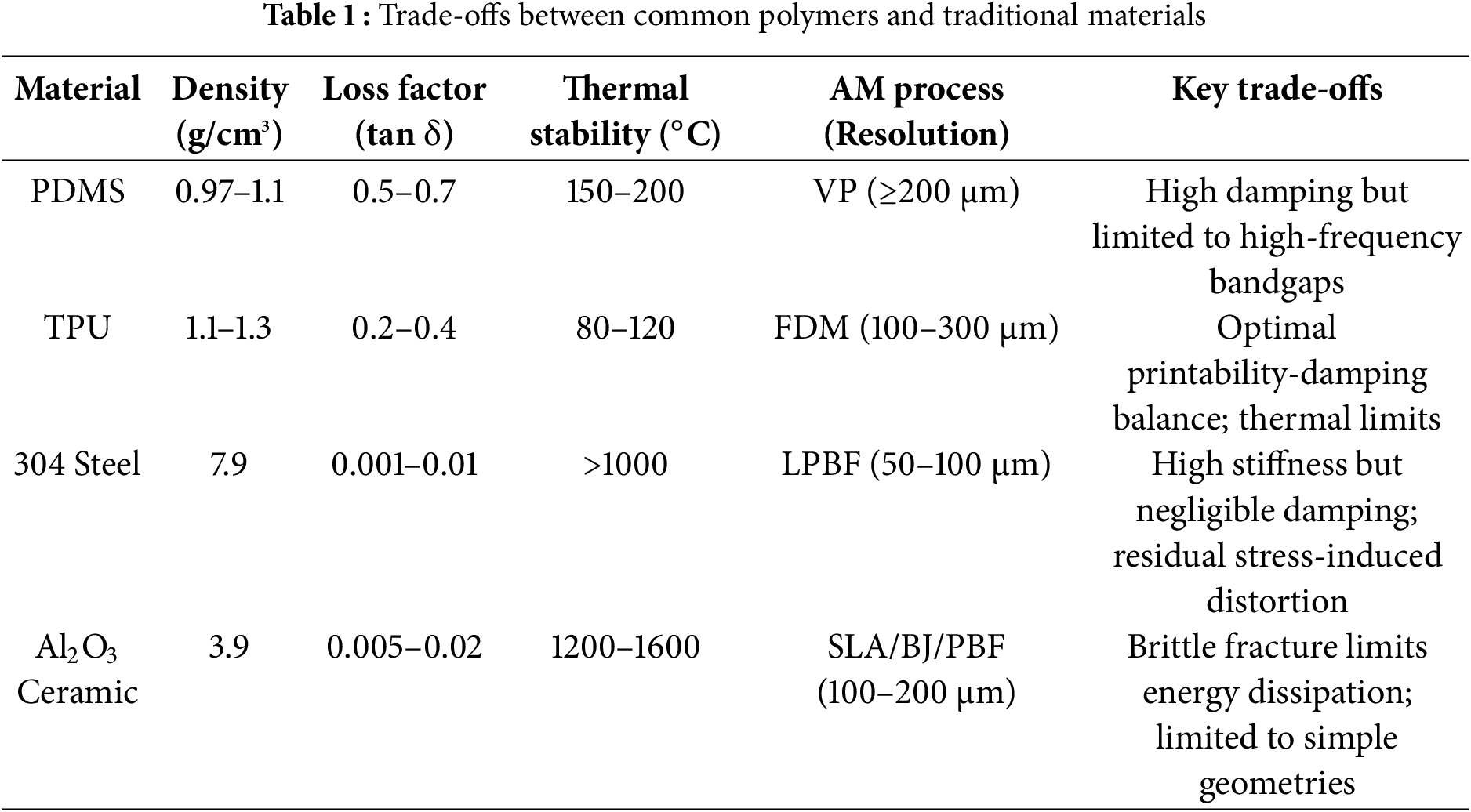

3.2 Polymer Material Design for Vibration Isolation

The selection and design of polymer materials for metamaterial-based vibration isolation require a critical balance between intrinsic material properties, additive manufacturing (AM) compatibility, and application-specific constraints. Table 1 summarizes the trade-offs among common polymers and conventional materials, highlighting polymers’ superior damping efficiency (tan δ > 0.1) and AM adaptability compared to metals and ceramics. For instance, PDMS achieves a loss factor of 0.5–0.7, enabling 70% higher energy dissipation than stainless steel [32], but its limited resolution in vat photopolymerization (VP) restricts Bragg bandgap design to frequencies above 2 kHz, as shown in Li et al.’s study of VP-printed PDMS phononic crystals [30]. In contrast, TPU’s compatibility with fused deposition modeling (FDM) allows scalable fabrication of lattice structures, though anisotropic interlayer voids reduce Z-axis damping by 20% compared to isotropic bulk material [59].

The glass transition temperature (Tg) critically governs polymer performance boundaries. TPU’s low Tg (−50°C) ensures effective rubbery-state damping at room temperature (tan δ ≈ 0.3), but its damping efficiency declines sharply above 80°C due to excessive chain mobility—a limitation absent in high-Tg polymers like PEEK (Tg ≈ 143°C). Syam et al. [63] demonstrated this trade-off in SLS-printed PA12-PEEK hybrid lattices, which retained 80% compressive strength at 200°C but exhibited minimal damping (tan δ < 0.1), confining their use to high-stability, low-damping environments.

3.3 Metamaterial Structural Design for Targeted Bandgaps

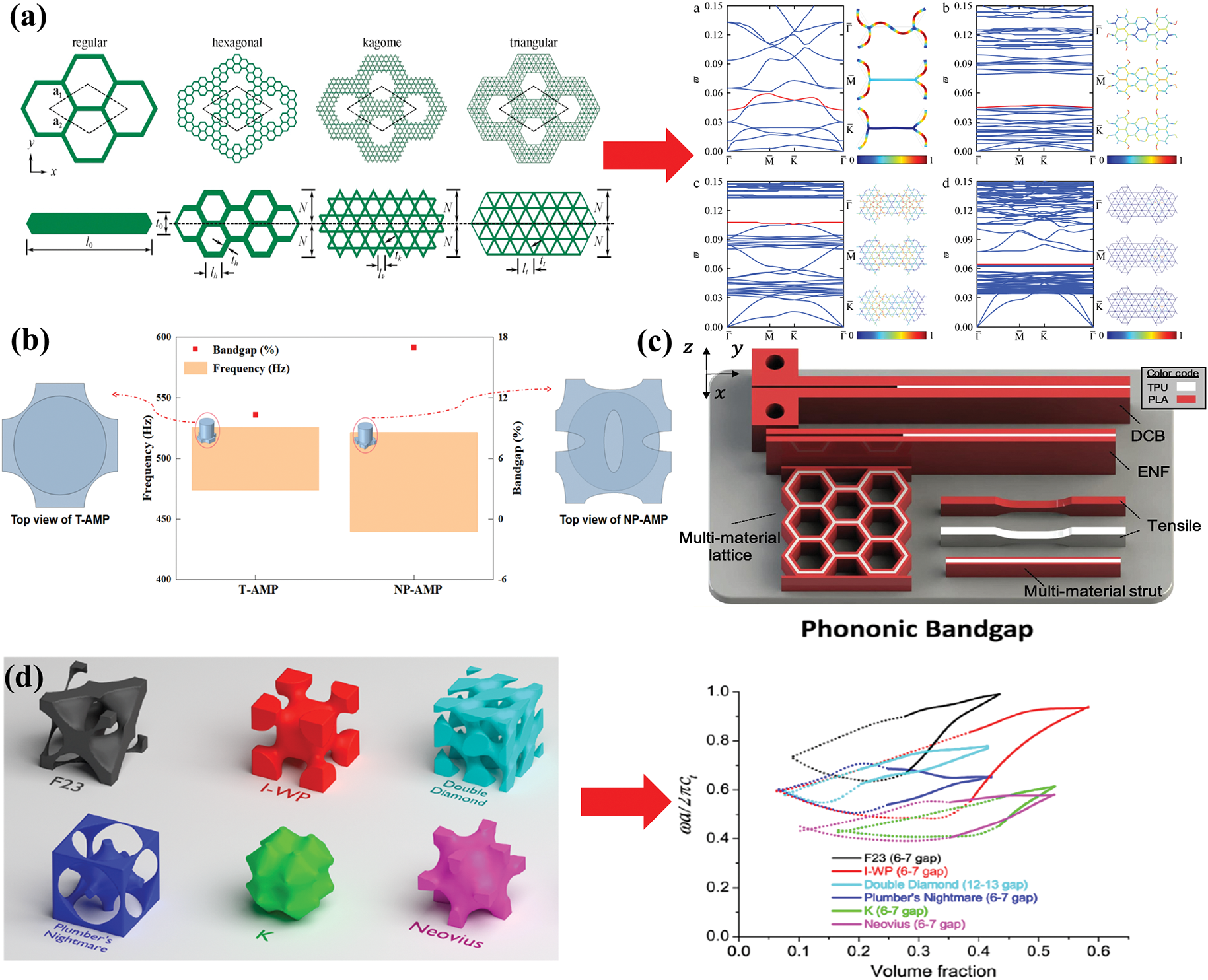

The vibration-isolation performance of polymer metamaterials is governed by three dominant structural archetypes—2D/3D lattices, auxetic architectures, and foam-like graded designs—each exploiting distinct wave manipulation mechanisms through AM-enabled geometric control.

2D/3D lattices utilize periodic arrangements to induce Bragg scattering bandgaps. For example, the bandgap size can be controlled by adjusting the hierarchical structure of a 2D honeycomb lattice. As shown in Fig. 3a, the number of bandgaps increases from one to three as the hierarchy progresses from the first to the fourth level [59]. Specifically, the maximum bandgap ranges for the three hierarchical structures are 0.047–0.079, 0.108–0.133, and 0.064–0.078, respectively.

Auxetic structures leverage negative Poisson’s ratio to widen the bandgap through strain-dependent stiffness modulation. Fig. 3b illustrates a negative Poisson’s ratio structure derived from a 2D phononic metamaterial. Compared to the pre-optimized structure, the new auxetic 2D structure exhibits a bandgap starting frequency of 439.72 Hz (previously 474.05 Hz), with the bandgap width increasing to 17% (compared to 10.3% before optimization) [13].

3D lattice structures provide enhanced spatial stiffness and mechanical response through a three-dimensional interwoven network. They are particularly suitable for applications with complex wave propagation characteristics. As shown in Fig. 3d, within different TPMS structures, the network configuration can be tailored for a larger phononic bandgap by reducing the thickness of the struts bridging the unit cells. Among them, the IWP structure achieves a bandgap width of 0.41 [15]. Fig. 3e illustrates an interwoven biphasic design, where the intricate neck-cavity configuration forms Helmholtz resonators (HRs), which are crucial for effective sound absorption [57]. The incident acoustic energy is completely absorbed and dissipated as heat. In terms of vibration energy dissipation, resonators are an excellent choice. Ding et al. explored a large-scale metamaterial vibration isolation barrier consisting of a 5 × 5 array of resonators (Fig. 3f), which exhibited significant localized resonance attenuation in two distinct frequency ranges, induced by first-order and second-order vertical resonances, around 30 and 80 Hz, respectively [64]. Furthermore, data-driven approaches based on deep learning can also be used to manipulate bandgaps. As shown in Fig. 3g, Li et al. utilized image-based finite element analysis and deep learning-assisted methods to design phononic crystal structures with desired bandgaps. These approaches provide a new paradigm for optimizing the bandgap design and vibration reduction functionality of metamaterials [30].

4 AM of Polymeric Metamaterials

To effectively explore the application of AM in polymer-based metamaterials, it is essential to first understand the key AM technologies utilized in their fabrication. These technologies enable the precise construction of complex geometries, offering tailored mechanical properties that are crucial for vibration isolation and other advanced functionalities.

The examples in Section 2 illustrate that metamaterials exhibit complex porous or hollow structures on both macro and micro scales, which are challenging to achieve using conventional subtractive manufacturing or casting methods. AM is an advanced fabrication technique that creates complex structures by adding material layer by layer. Compared to traditional subtractive manufacturing, AM offers significant advantages, such as eliminating the need for complex molds, reducing material waste, and enabling the production of intricate shapes that are difficult or impossible to achieve with conventional methods. With continuous technological advancements, AM has been widely adopted across industries such as aerospace, automotive, healthcare, and construction. In the field of polymer materials, AM presents unprecedented opportunities for the rapid fabrication of complex metamaterials.

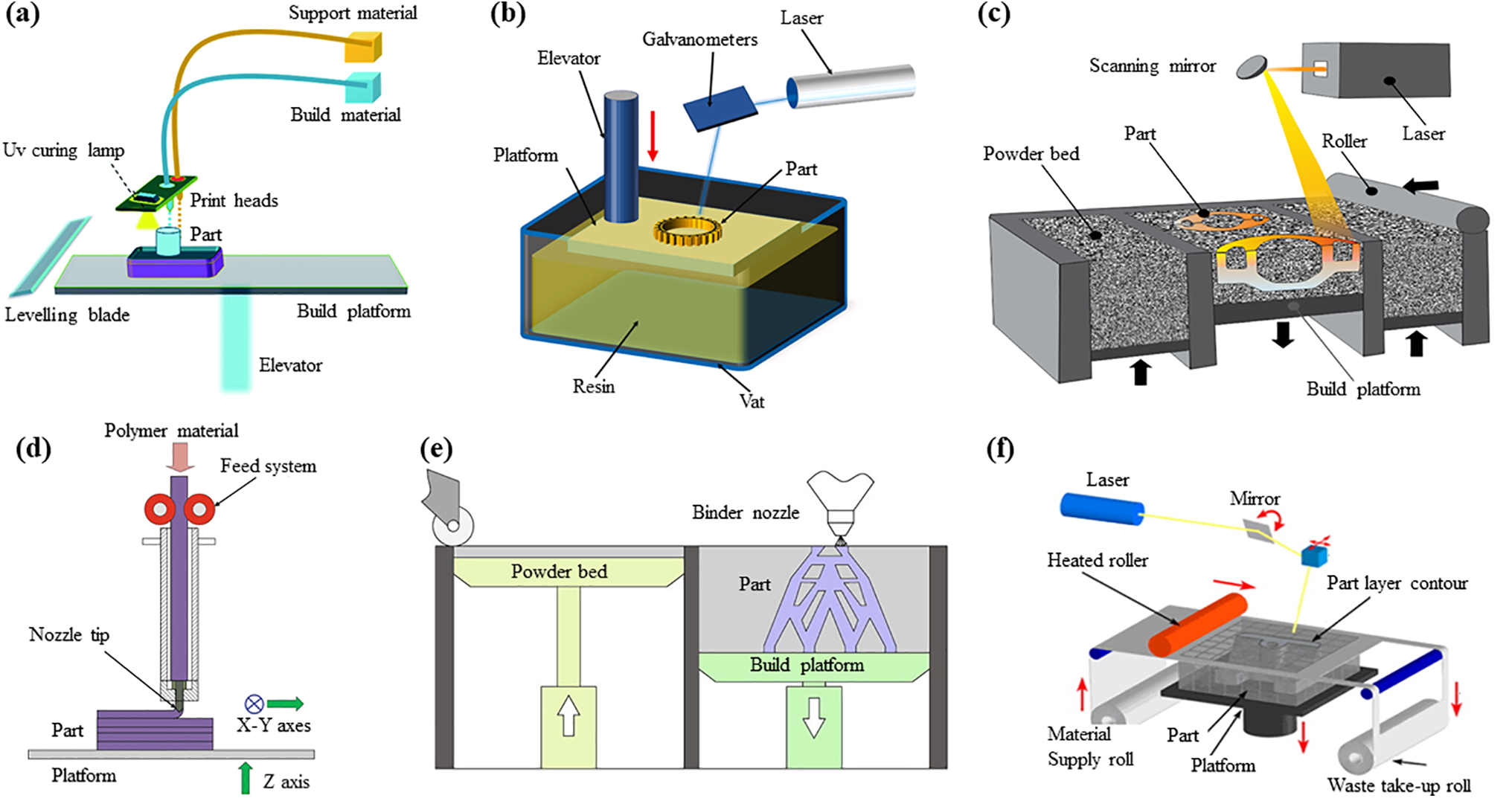

As shown in Fig. 4, polymer AM technologies encompass various molding methods, including material jetting (MJ), vat photopolymerization (VP), powder bed fusion (PBF), material extrusion (ME), binder jetting (BJ), and sheet lamination (SL). Each of these techniques has unique characteristics and suitability for specific applications. Below, we provide a detailed overview of these AM techniques and discuss their potential and advantages in fabricating polymer-based metamaterials for vibration isolation.

Figure 4: Summary of polymer AM processes. (a) MJ [65] (Copyright 2018, with permission from Creative Commons 4.0), (b) VP [66] (Copyright 2021, with permission from Elsevier), (c) PBF [67] (Copyright 2021, with permission from Elsevier), (d) ME [68], (e) BJ [69] (Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier), (f) SL [70] (Copyright 2012, with permission from Elsevier)

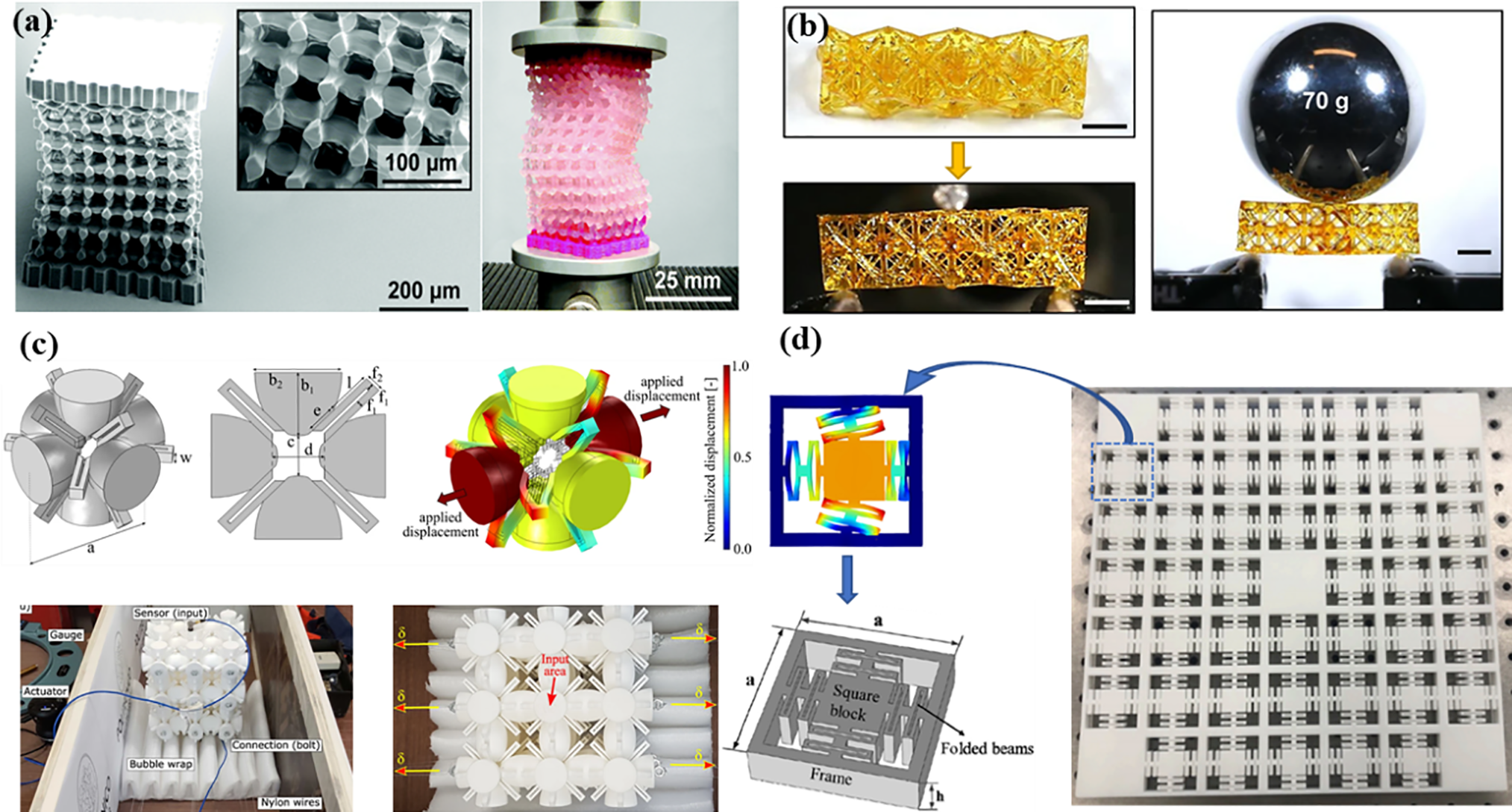

MJ is a 3D printing technique that precisely jets liquid material from a nozzle and cures it layer by layer. This method typically uses photopolymer resins or other thermosetting polymers as raw materials, which solidify under light or heat. The primary advantages of MJ are its high resolution and surface quality, allowing the production of intricate details and complex geometries with layer thicknesses as low as 16 μm [65]. It is particularly suitable for fabricating vibration-isolating polymer-based metamaterials requiring high precision (as shown in Fig. 5a).

Figure 5: Research of polymer vibration-isolation metamaterials. (a) Soft mechanical metamaterials fabricated by MJ [78] (Copyright 2019, with permission from Creative Commons 4.0), (b) Lattice metamaterials with repairable, memory, and tunable properties fabricated by DLP [79] (Copyright 2020, with permission from Creative Commons 4.0), (c) 3D auxetic metamaterials with ultra-wide tunable band gaps fabricated by SLS [80] (Copyright 2018, with permission from Creative Commons 4.0), (d) 3D low-frequency vibration-isolation plate of ‘frame-spring-mass’ system fabricated by FDM [62] (Copyright 2020, with permission from Elsevier)

4.2 Polymer AM Research Status and Vibration-Isolation Applications

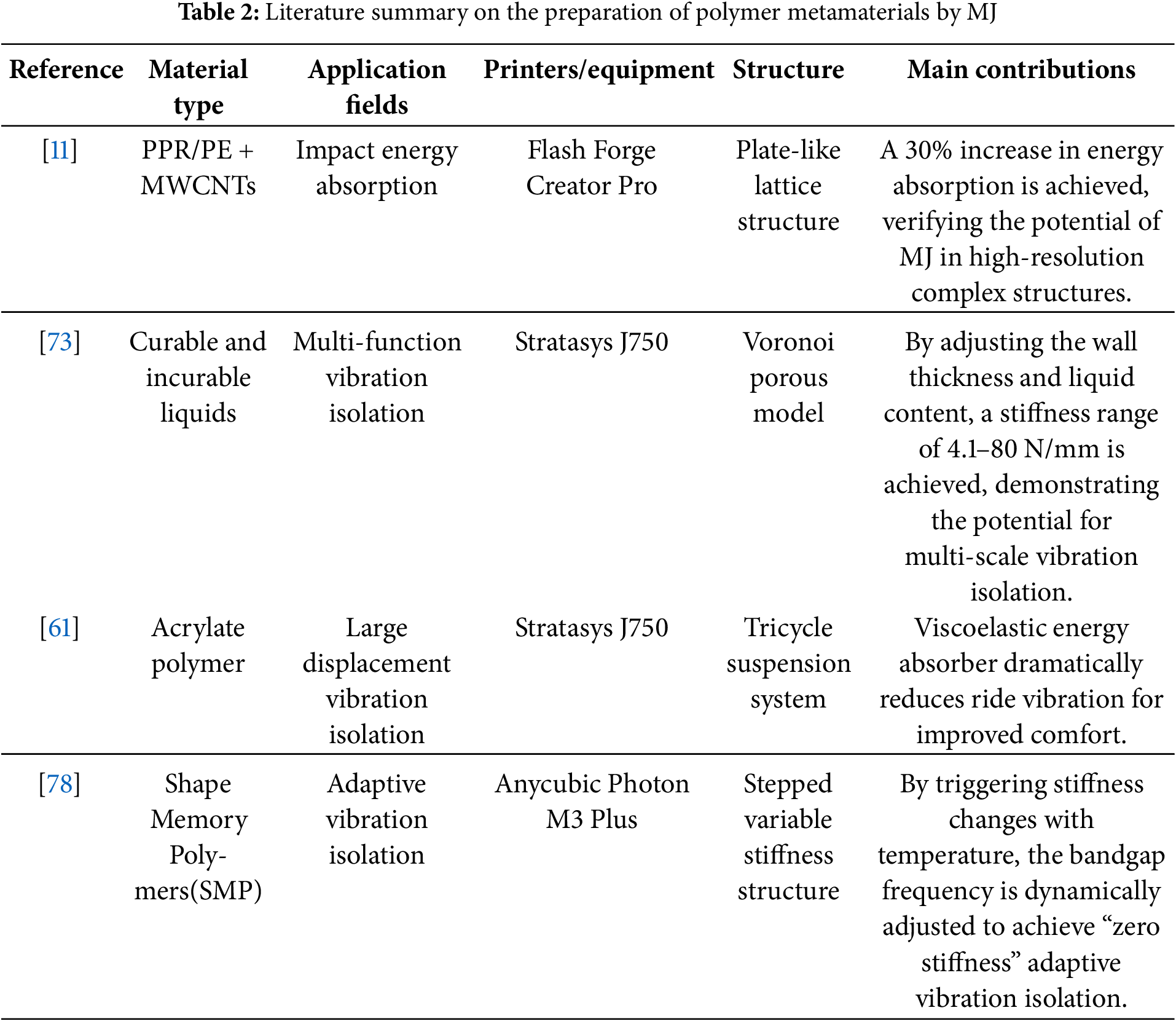

To explore the role of additive manufacturing (AM) in vibration isolation, we now look at the key AM techniques. Each method offers unique advantages for creating polymer-based metamaterials with tailored properties. In order to better exhibit the characteristics of each AM technology, we have drawn tables in each subsection (e.g., Tables 2–6).

Given its characteristics, MJ has immense potential in AM of microstructures. Compared to other AM techniques, MJ offers significant advantages in dimensional accuracy and surface finish of polymer structures. Compared to three-dimensional printing (3DP) and selective laser sintering (SLS), MJ-produced 3D models achieve superior surface and dimensional accuracy [71]. Salmi et al. printed skull models using SLS, 3DP, and MJ technologies, measuring their dimensional accuracy, and found MJ had the lowest dimensional error, averaging 0.18% [72]. Compared to FDM, MJ better addresses dimensional accuracy issues. For instance, Lee et al. [73] compared denture models fabricated using FDM and MJ. They reported MJ-produced models had smoother surfaces due to thinner layer thicknesses (FDM: 0.330 mm; MJ: 0.016 mm). Dizon et al. [74] compared polymer parts fabricated using stereolithography appearance (SLA), FDM, and MJ technologies, noting that SLA and MJ had excellent surface finish, with MJ providing higher dimensional accuracy than SLA.

MJ is well-suited for creating fine structures and complex geometries, enhancing vibration-isolation performance. Brown-Moore used MJ to fabricate Voronoi porous models, adjusting wall thickness and liquid content to achieve stiffness ranges from 4.1 to 80 N/mm, showcasing multifunctional, multiscale vibration-isolation potential [75]. Lipton et al. developed a tricycle suspension system for large displacement applications in harsh environments, reporting that viscoelastic energy absorbers fabricated using MJ significantly reduced vibration during riding, improving comfort [61]. Mora et al. highlighted practical applications of MJ in rigid and soft lattice structures, noting that adjusting geometric features of different topologies using the same material significantly improved energy absorption efficiency by approximately 30%, which is critical for vibration isolation [76]. Vdovin et al. used Vero White material to fabricate resonant honeycomb coupling tubes for frequency ranges of 300–600 Hz, reporting that MJ-printed parts had double the sound power absorption capacity of standard mineral wool absorbers [77]. However, MJ technology is not environmentally friendly due to process and material limitations (e.g., ABS, PLA, etc.), which generate polluting gases during the printing process.

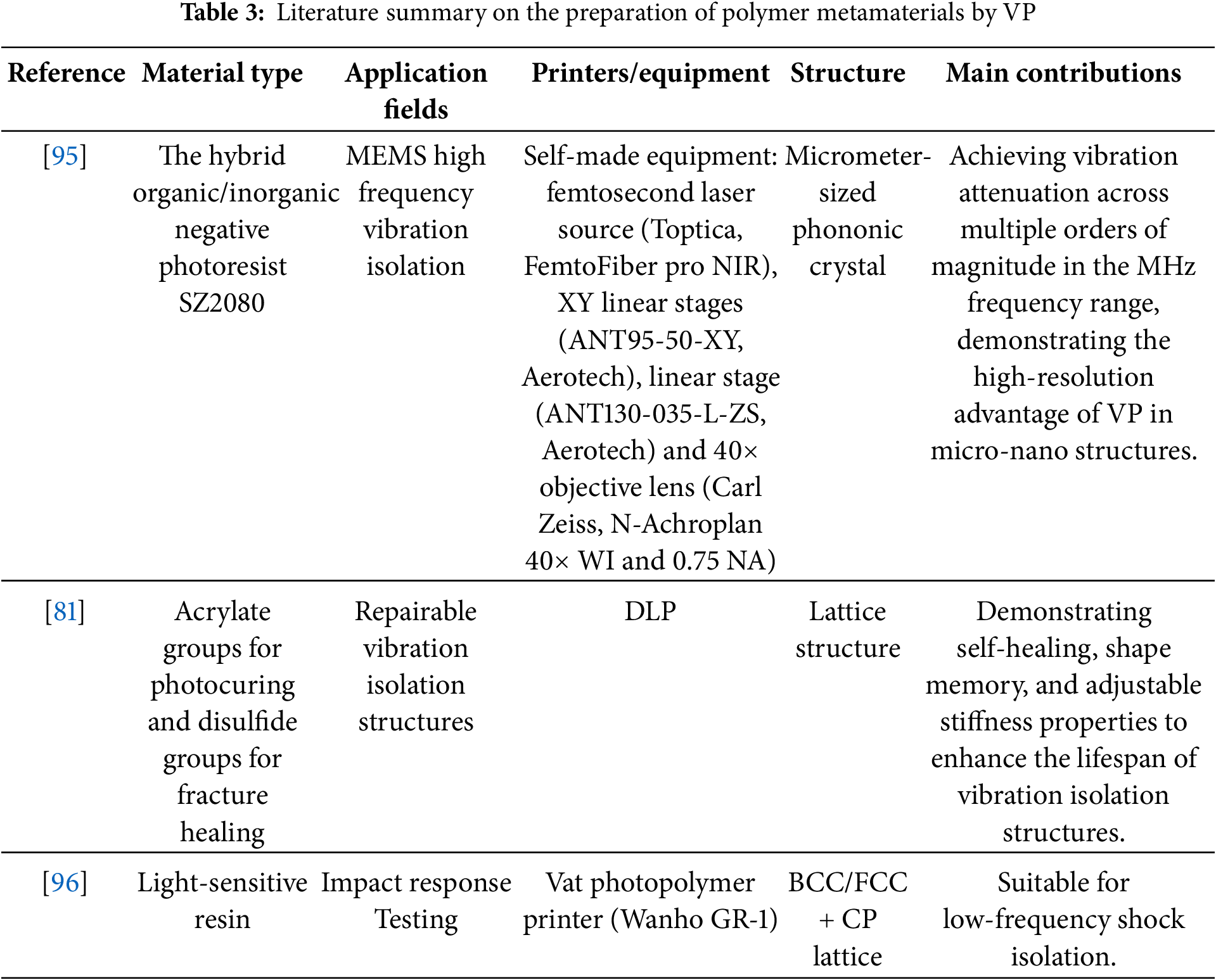

VP involves curing photopolymer resins layer by layer using ultraviolet (UV) light to form 3D objects [81]. This technique offers exceptionally high resolution, making it ideal for creating intricate and precise structures (as shown in Fig. 5b). Its main variants include SLA, digital light processing (DLP) [82,83], and two-photon polymerization (TPP). Due to its precise control over the curing process, VP is particularly useful in applications requiring meticulous control of material microstructures. SLA was the first technology introduced for polymer AM [84], and many researchers have used it to fabricate high-precision polymer structures applicable across various industries [85–88]. In recent years, DLP and TPP have become research hotspots due to their faster fabrication speeds and higher accuracy [89]. Compared to point-by-point fabrication, DLP’s layer-by-layer scanning offers advantages in printing speed and energy efficiency, representing the second generation of VP 3D printing technology [90]. Grigoryan et al. [91] utilized a mixture of PEGDA and gelatin methacrylate as raw materials, employing DLP technology to fabricate functional microvascular structures and mitral valves. The fabricated structures demonstrated high precision and biocompatibility in experiments. To enhance DLP’s precision and efficiency across different photopolymer materials, Li et al. [92] developed a theoretical model to predict the Jacobs working curve, which describes the relationship between UV energy and cured material thickness, to determine optimal printing parameters for each material. They explained that by characterizing three physical properties—solid absorptivity, liquid absorptivity, and gelation time—Jacobs working curve can be determined, and experimental results validated the model’s accuracy. As one of the highest-resolution 3D printing techniques, TPP offers resolutions down to 100 nm, enabling broad applications in micro-nano devices such as microneedle patches [93] and micro-optical components [94].

The high resolution of VP has demonstrated significant advantages in micro-nano vibration-isolation applications. Zega et al. [95] utilized TPP technology to fabricate vibration isolators for microelectromechanical systems, designed to mitigate the effects of high-frequency oscillating components on such devices. They reported that phononic crystals fabricated using TPP exhibited attenuation factors across multiple orders of magnitude, effectively isolating vibrations in the frequency range of hundreds of kHz to several MHz, a result attributed to TPP’s high-resolution printing capabilities. Doungkom et al. [96] employed DLP technology to fabricate lattice structures with micron-scale features and investigated the vibration-isolation performance of three designs under impact loading. They noted that compared to solid structures and face-centered cubic with cubic perimeter (FCC + CP), the body-centered cubic with cubic perimeter (BCC + CP) configuration exhibited the highest pulse response and average shock transfer rate, making it particularly suitable for vibration-isolation applications under forces below 300 N. Wang et al. [97] provided a comprehensive review of the applications of VP technology in metamaterials, highlighting its advantages in speed and resolution, which form a solid foundation for its use in mechanical and acoustic metamaterial vibration isolation. Additionally, VP can produce structures with microfeatures such as micropores and thin walls [98], which are critical for tuning wave propagation characteristics and vibration-isolation performance. The ability to create complex microstructures is essential for optimizing vibration isolation at specific frequencies.

PBF is a process in which polymer powders are selectively melted layer by layer using lasers or electron beams to create solid objects [99,100]. While commonly used for metals and plastics, it is also suitable for high-performance polymers such as polyamides (e.g., PA12, PA11), polyetherketoneketone (PEKK), and PEEK [66]. One of the main advantages of PBF is its ability to produce parts with high mechanical strength and thermal stability [101] while also enabling the fabrication of complex geometries [102].

Models produced by PBF technology exhibit high precision but have slightly lower density compared to the other two methods. Improving model density is a critical challenge for LPB technology. Density is influenced not only by printing parameters but also by the packing density of the powder bed [103–105]. Tan et al. [106] developed a discrete element model to simulate powder bed packing, helping to understand void formation during the process. They found that increasing the powder layer thickness improves packing density, enhances model density, and reduces surface roughness, while higher spreading speeds negatively impact packing quality and density. Eshraghi et al. [107] achieved 99.5% density in polymer nanocomposites by adding 3 wt% graphite nanoplatelets to polyamide-12 powder. Furthermore, PBF process parameters and material properties significantly affect model density. Caulfield et al. [108] found that increasing laser energy density within a certain range improves the density of polyamide parts fabricated by PBF. Higher energy densities promote better particle fusion, resulting in stronger parts. Chatham et al. [109] suggested setting the powder bed temperature below the crystallization onset of poly (phenylene sulfide) (255°C) to minimize side reactions such as chain extension, branching, and cross-linking during printing. After optimization, the fabricated parts achieved a density of 1.18 g/cm3. Dechet et al. [110] introduced a novel polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) material with high crystallinity, narrow particle size distribution, and an average particle size of 36 μm, produced through liquid-liquid phase separation and crystallization. This material exhibited excellent flowability at 200°C in PBF systems, significantly improving density and precision.

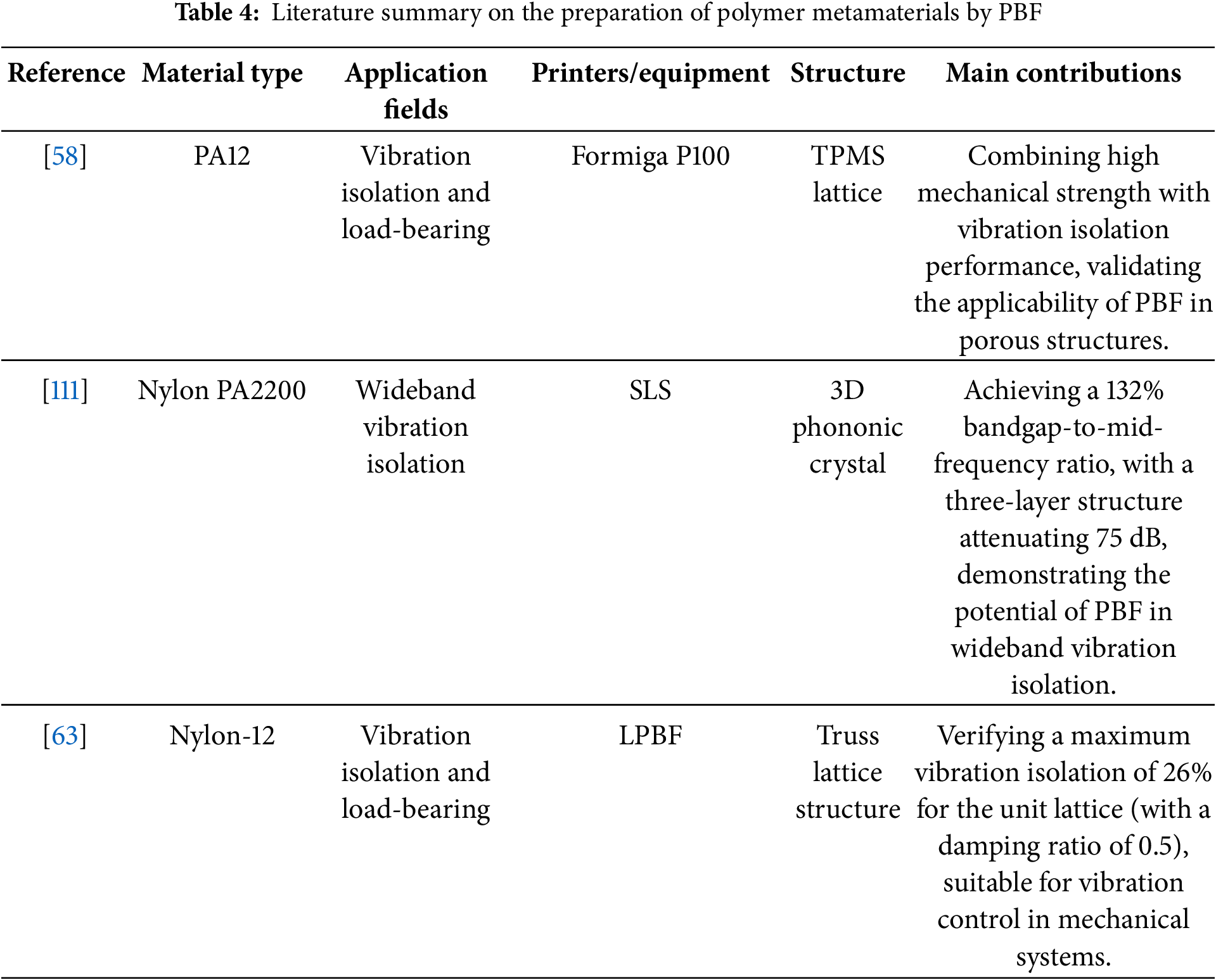

For polymer-based metamaterials in vibration isolation, PBF facilitates microstructure control, mechanical optimization, and vibration-isolation customization (as shown in Fig. 5c). D’Alessandro et al. [111] utilized SLS to fabricate 3D phononic crystals with ultra-wide bandgaps, achieving a 132% bandgap-to-midgap ratio and an attenuation rate of 75 dB for three-layer crystals. Syam et al. [63] fabricated lattice structures from Nylon-12 using SLS, achieving high vibration-isolation and load-bearing performance, with a maximum vibration reduction of 26% per unit cell at a damping ratio of 0.5.

ME is among the most commonly used AM techniques, widely applied in fabricating ceramics [112–115] and polymers [116–118]. FDM is a widely used example [119–121]. FDM is considered ideal for polymers due to its ability to handle common melting temperatures and its relatively fast fabrication speed. Thermoplastics such as ABS [122], PLA [123,124], PMMA [125], polyethylene (PE) [126], TPU [127] and polypropylene (PP) [128] are most commonly used in this method. These materials are heated, extruded through a nozzle, and deposited layer by layer to form 3D objects. The primary advantages of ME are its cost-effectiveness and ease of use, making it ideal for large-scale production and rapid prototyping [129]. However, the mechanical properties and precision of FDM-manufactured components have remained suboptimal. In this regard, many researchers have explored the relationship between printing parameters, quality, and strength [120,130]. Beniak et al. [131] analyzed the significance of layer thickness and extrusion temperature on dimensional accuracy. The results showed that extrusion temperature had a greater impact on dimensional accuracy, with accuracy improving as the extrusion temperature decreased. Mohamed et al. [132] used the Taguchi method to develop a regression model for six process parameters—layer thickness, build orientation, road width, number of contours, air gap, and raster angle—to predict the nonlinear relationship between FDM process parameters and dimensional accuracy. Chohan et al. [133] employed steam smoothing to improve the precision of ABS material printing. They evaporated a mixture of decafluoropentane and trans-dichloroethylene, introducing the vapor into the FDM print chamber. The results showed significant improvement in the surface layer pattern of printed parts, with dimensional errors of 0.35%, 0.19%, and 0.41% in the neck, middle, and top of the printed hip joint components, respectively. Furthermore, printing parameters are closely related to the mechanical properties of the components. Li et al. [134] found that the tensile strength of components is closely related to the interface bonding state, which is determined by thermal transitions, and used a bilinear elastic softening cohesive zone model to analyze the maximum load-bearing capacity under different interface bonding states. Wang et al. [135] were the first to use finite element analysis to simulate the melting conditions and flow behavior of PEEK material in the channel, developing a constitutive equation for dynamic viscosity. They optimized process parameters experimentally to improve density, reduce internal defects, and enhance interlayer bonding. They stated that with a heating temperature of 440°C, a layer thickness of 0.1 mm, and a print speed of 20 mm/s, the component density reached 92%, tensile strength 76 MPa, and surface roughness as low as 7.8 μm.

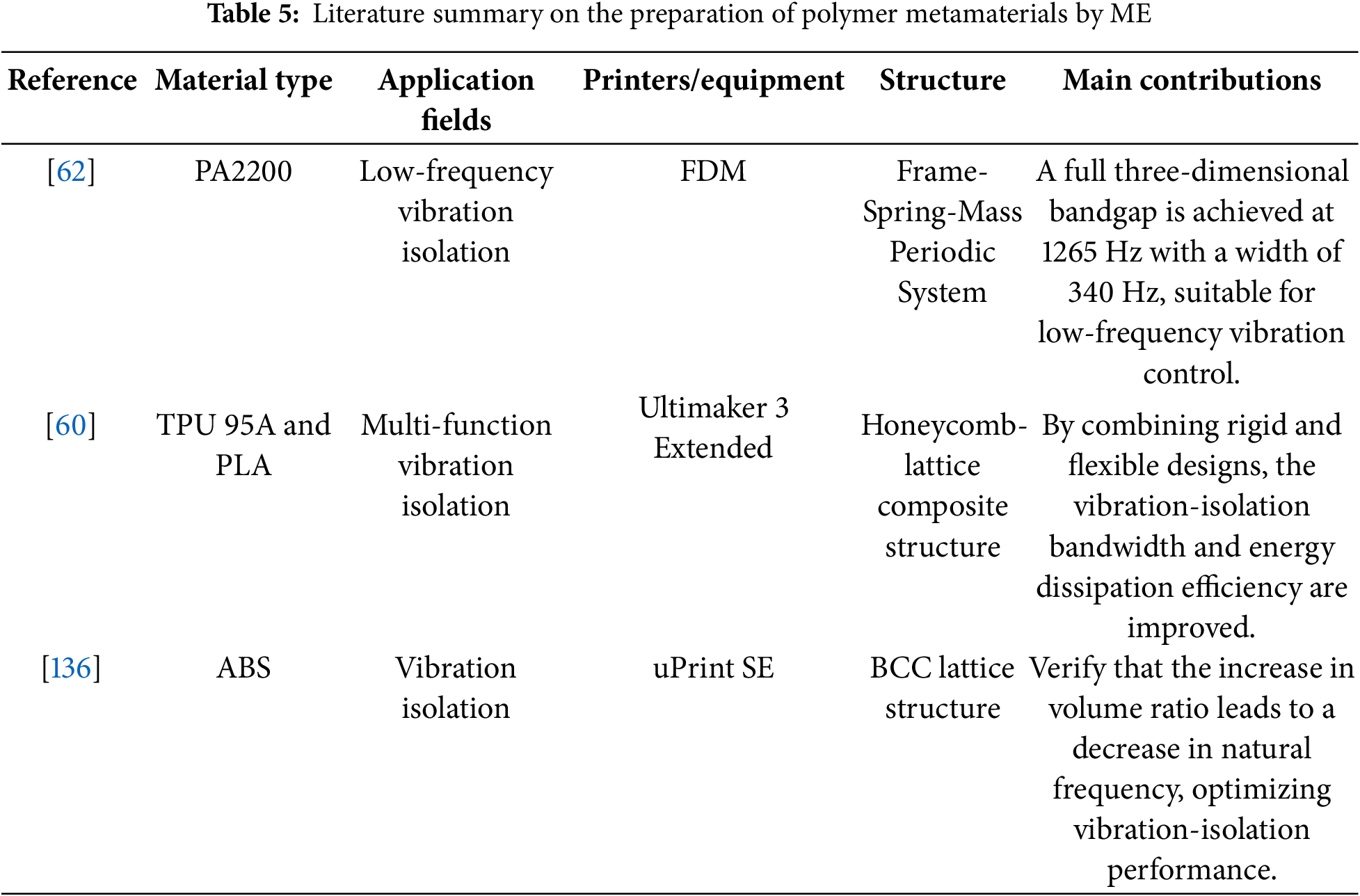

In the context of polymer-based vibration-isolation metamaterials, ME can effectively produce components with complex geometries (as shown in Fig. 5d). Monkova et al. [136] used FDM technology to fabricate BCC lattice structures from ABS material to study the impact of volume ratio on vibration-isolation characteristics. They found that the inherent frequency of ABS components decreases as the volume ratio increases. Yao et al. [62] proposed a novel metamaterial vibration-isolation plate with a periodic “frame-spring-mass” system, fabricated using FDM-formed polyamide components. This structure achieves a complete 3D bandgap around 1265 Hz, with a width of 340 Hz. This structure shows potential for low-frequency vibration isolation and stress wave mitigation.

BJ is an AM technique that uses a binder to bond powder layers together to form solid objects. Unlike other AM methods, BJ does not require heat to melt materials, making it a faster and more cost-effective process. BJ can produce complex parts without the need for supports, making it suitable for creating hollow structures. However, parts produced using BJ have lower strength, are prone to deformation or fracture, and suffer from poor forming quality and density due to uneven powder distribution. The bonding between the binder and the base powder significantly affects the forming quality. Colton et al. [137] studied the effective saturation of printed lines under different droplet printing parameters. The results showed that increasing droplet speed and droplet distance both decrease the effective saturation of the binder in different powders. Research on pure polymers using BJ is limited, whereas studies on polymer composites have been more extensive. For example, Inzana et al. [138] fabricated a calcium phosphate and collagen composite scaffold for bone regeneration. Commonly used polymers in BJ, such as PLA, polycaprolactone (PCL), and collagen [139], have advanced the field of biomedical applications and demonstrated the advantages of polymer composites.

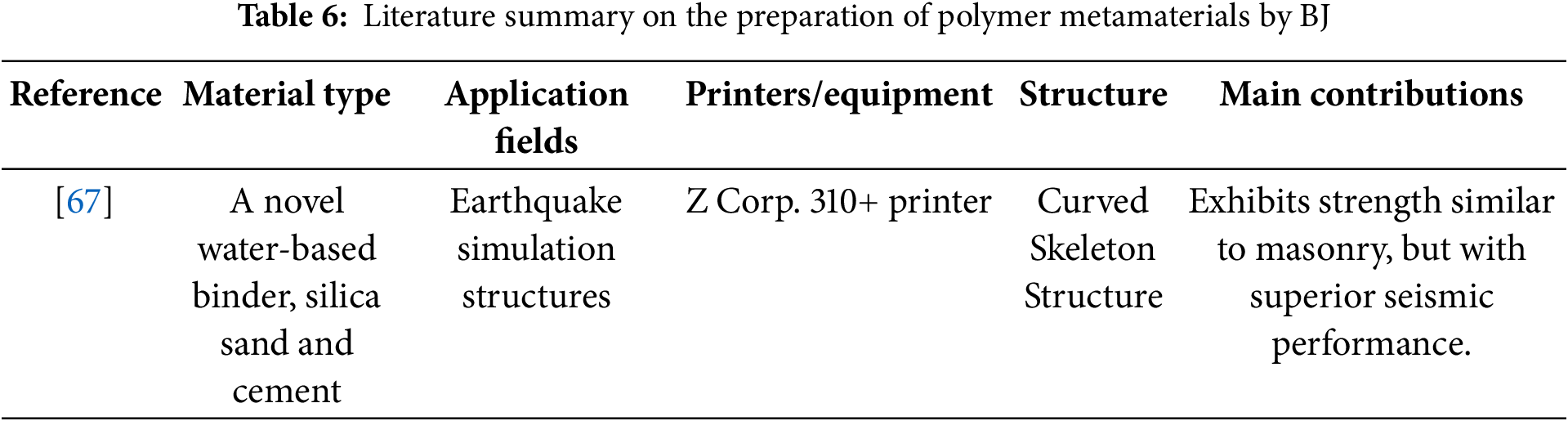

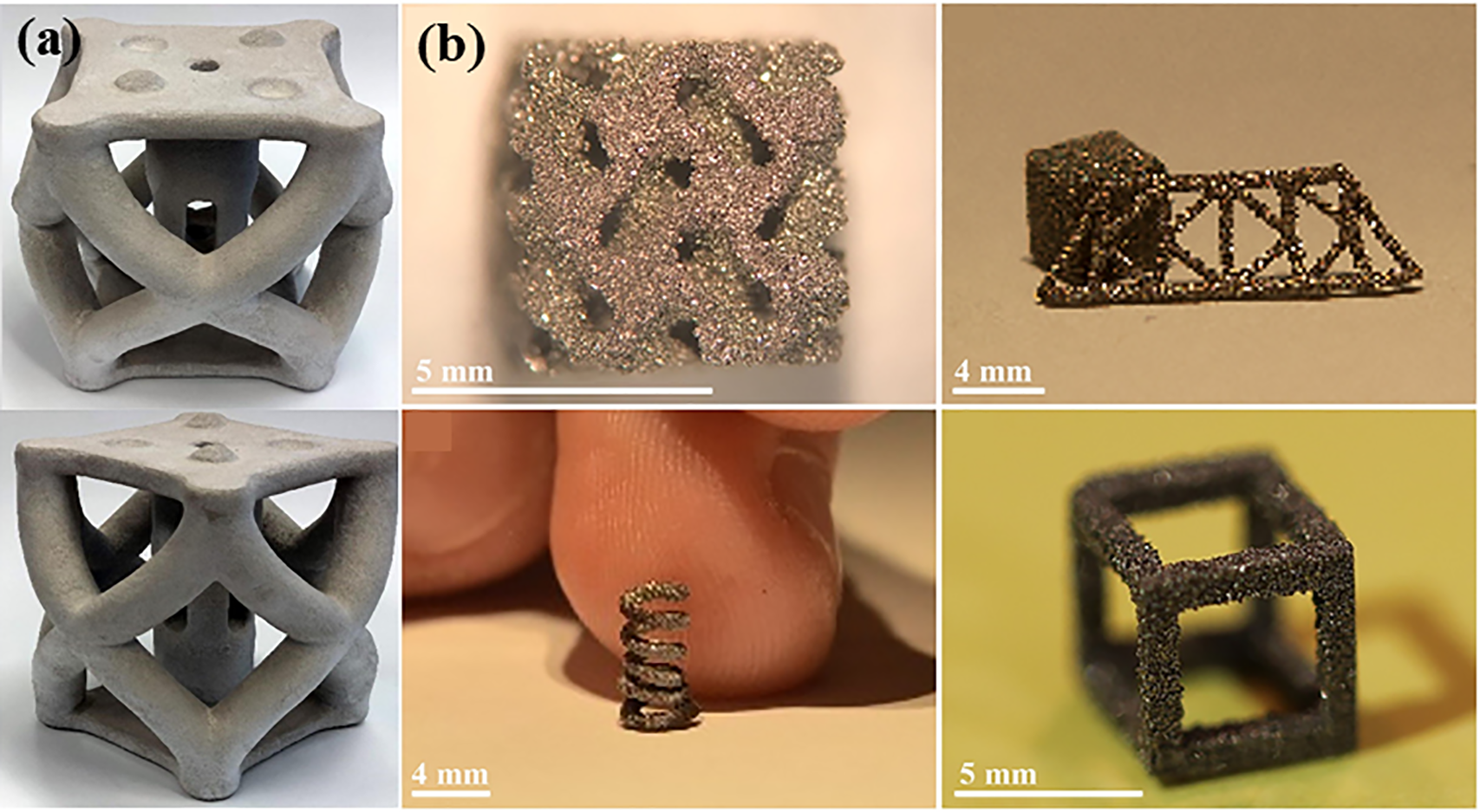

There are not a lot of vibration-isolation applications for BJ., with most studies focusing on cement [67](Fig. 6a), metal [140] (Fig. 6b), sand mold [141] ceramic powders, and polymer binders. For example, Del Giudice et al. [142] used polymer furfuryl alcohol resin as a binder and GS19 quartz sand as powder to fabricate small structures for seismic response simulation. They reported that the small brick-like structures fabricated with BJ exhibited strength similar to masonry but with better seismic performance. Gaytan et al. [143] suggested that BaTiO3 fabricated via BJ could serve as part of a vibration control system with a coupled damper. BJ, as an AM technique capable of producing large parts, can be used for rapid production of large-scale vibration-isolation structures, with potential for further processing to improve mechanical properties. With a wide range of material choices and fast production speed, BJ has significant potential for future development in polymer-based vibration-isolation structures.

Figure 6: Applications of BJ and SL. (a) Spraying of water-based cement-compatible liquid adhesives onto dry cement mixed with fine round-grained silica powder using BJ [67] (Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier), (b) 4D printing of Ni-Mn-Ga magnetic shape memory alloy [140] (Copyright 2018, with permission from Elsevier)

The application of SL in pure polymer fields is limited, and there are almost no reports in the field of polymer-based vibration-isolation metamaterials; thus, it will not be further discussed in this paper.

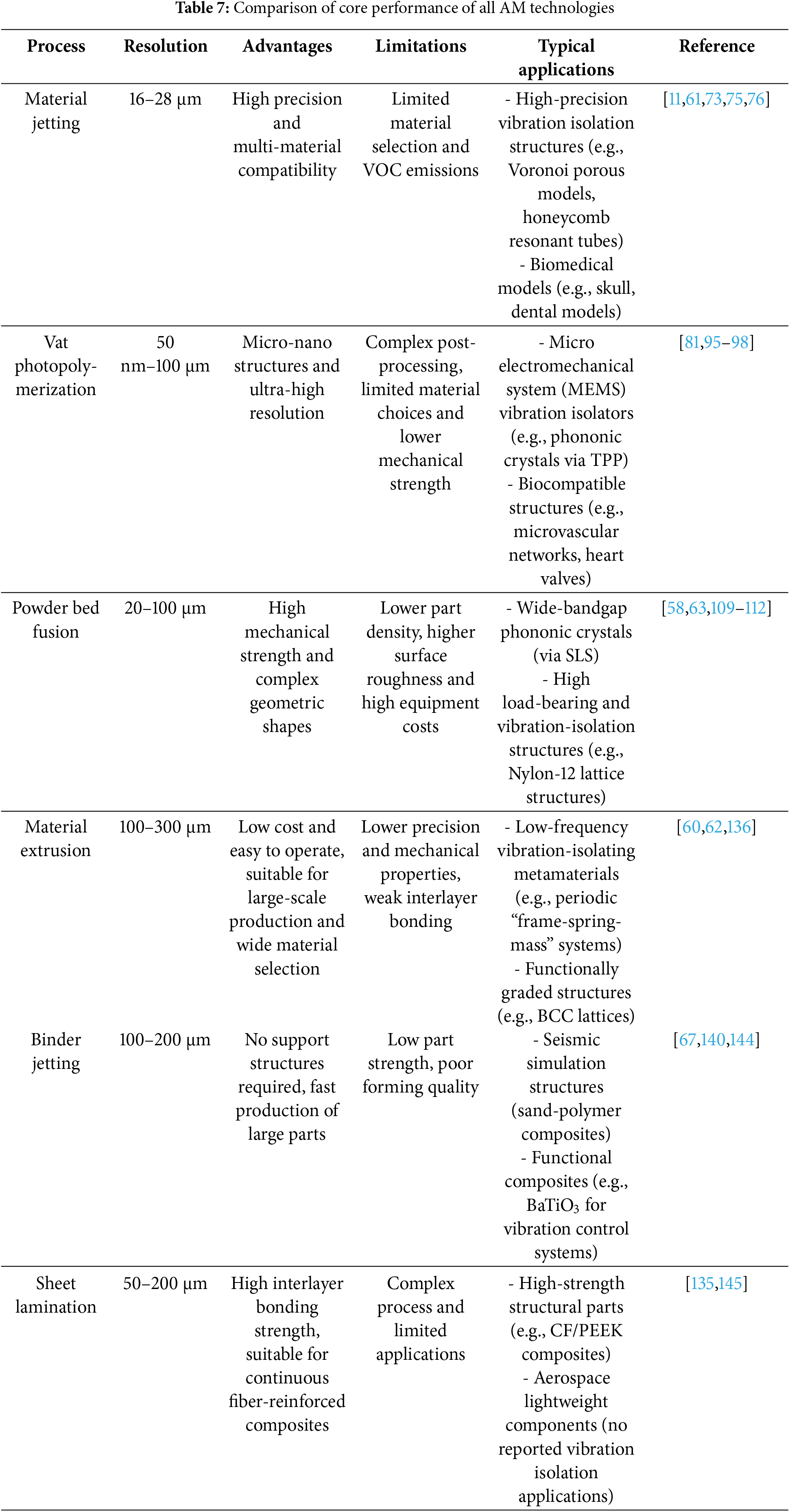

Current research on AM technologies for polymer-based metamaterials in vibration isolation reveals significant differences in performance and limitations across various techniques. As shown in Table 7, we summarize a table to visualize the characteristics of the polymer additive manufacturing process. MJ achieves exceptional precision, with resolutions up to 16 μm and excellent surface quality, making it particularly suited for the fabrication of intricate microstructures. However, its reliance on photopolymer resins with low thermal stability (<100°C) and the associated volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions limit its application in high-stability environments. VP, employing DLP and TPP, offers distinct advantages at the micro and nano scales, but is constrained by its dependence on specialized resins and relatively high costs. PBF enables the production of parts with high mechanical strength; however, the insufficient density (<95%) of fine lattice structures leads to a reduction in vibration isolation efficiency by approximately 15%, necessitating optimization of powder bed and laser parameters. ME, such as FDM, is cost-effective and widely accessible, but requires process optimization (e.g., layer thickness control and temperature adjustment) to improve interlayer bonding strength. BJ presents potential for rapid prototyping, but issues related to part strength and density limit its application in vibration isolation. Overall, AM technologies provide a new paradigm for performance optimization of metamaterials through customized structural designs. Future efforts should focus on hybrid manufacturing strategies (e.g., combining MJ and PBF) to balance resolution, material diversity, and scalability, while also developing environmentally friendly resins.

The influence of AM on metamaterials goes beyond merely the fabrication process; it also plays a crucial role in shaping their vibration-isolation performance. The choice of AM technology impacts key material characteristics, such as surface finish, internal porosity, and density, which, in turn, affect mechanical behavior and vibration isolation efficiency. High-precision processes like MJ and VP can produce metamaterials with smooth surfaces and detailed features, leading to more consistent material properties and better vibration isolation. Conversely, techniques like PBF, which enable the fabrication of self-supporting structures, allow for the creation of materials with unique porosity and complex geometries that enhance damping and facilitate vibration isolation over a broader frequency range. Additionally, AM’s ability to customize lattice architectures and complex geometries allows for the fine-tuning of mechanical resonances, improving vibration attenuation. However, process-induced defects, such as residual stresses or voids, may compromise the material’s mechanical integrity and energy dissipation, affecting the overall performance of vibration-isolation metamaterials. These factors underline the critical role of AM in both the fabrication and functional optimization of metamaterials for vibration isolation.

While AM-fabricated polymer metamaterials have demonstrated significant potential in vibration isolation, critical gaps and challenges remain that warrant attention. Most studies focus on conventional thermoplastics (e.g., TPU, PLA) due to their compatibility with FDM and SLS, but high-temperature polymers (e.g., PEEK, PEKK) are underutilized in AM processes like PBF, limiting applications in extreme conditions such as aerospace and automotive industries. Additionally, multi-material integration, particularly hybrid polymer-ceramic or polymer-metal metamaterials, is rarely explored, missing opportunities for broadband attenuation. Over 80% of experiments validate isolation performance under simplified sinusoidal vibrations in lab settings, neglecting real-world stochastic or transient excitations such as seismic shocks or machinery impacts. Furthermore, long-term durability studies addressing fatigue behavior or environmental aging (e.g., humidity, UV exposure) are scarce, raising concerns about reliability in industrial applications. Scalability is another issue, as AM techniques like VP and MJ achieve high resolution but are limited to small build volumes (<30 cm3), leaving large-scale applications (e.g., civil engineering) largely unexplored. Economic feasibility is also a barrier, as SLS and MJ processes require expensive equipment and materials, with cost-benefit analyses comparing AM to traditional manufacturing absent in most studies. From a design perspective, there is an overreliance on topology optimization, while bio-inspired or data-driven approaches (e.g., generative AI) are rarely integrated, limiting innovation in unit cell architectures. Moreover, the lack of standardized metrics for evaluating vibration-isolation efficiency complicates comparative analysis across studies. To address these gaps, future research should prioritize multi-material AM to combine stiff polymers with viscoelastic matrices, develop in-situ monitoring systems to detect defects during printing, and establish standardized testing protocols for dynamic loading scenarios. New researchers should avoid over-optimizing single-frequency bandgaps without considering trade-offs in mechanical strength or manufacturability and should steer clear of purely theoretical designs untested under realistic conditions, as experimental validation is critical for industrial relevance.

In this section, we survey the frontier research of recent years and look ahead to the future of vibration-isolation metamaterials in the context of traditional ideas

Vibration isolation is a widespread issue across fields ranging from aerospace to everyday machinery, with traditional methods often inadequate for adapting to complex and dynamic environments. Metamaterial-based vibration isolation, particularly polymer metamaterials, offers a novel solution by manipulating wave propagation characteristics through structural design rather than relying on material properties [57]. Among these, variable frequency band metamaterials have emerged as a key innovation [146], enabling adaptability to a range of vibration frequencies through tunable structural configurations [144]. Additionally, biomimetic metamaterials draw inspiration from nature’s efficient designs [147,148], mimicking biological structures to achieve advanced vibration-isolation capabilities. Similarly, ancient architectural structures, known for their ingenious energy dissipation and load distribution mechanisms, inspire a new class of metamaterials that integrate traditional wisdom with modern technology [149]. Together, these advancements represent a promising future for vibration-isolation metamaterials, driving innovation through adaptive, functional, and bio-inspired designs.

5.1.1 Variable Frequency Band Metamaterials

The concept of variable frequency band metamaterial structures refers to artificially designed structures capable of exhibiting specific properties across different frequency ranges by adjusting their geometric parameters, material properties, or external loading conditions. These structures can dynamically regulate wave propagation characteristics based on practical application needs, demonstrating flexible vibration-isolation and energy-absorption capabilities [144]. By incorporating adjustable elements, such as variable stiffness elastic structures, tunable masses, or smart materials, metamaterials can achieve bandgap shifting, width control, or multi-frequency responses across low to high-frequency ranges. This enhances their effectiveness in isolating vibrations and noise at various frequencies, offering broad application prospects in adaptive vibration control, reconfigurable acoustic devices, and intelligent mechanical systems.

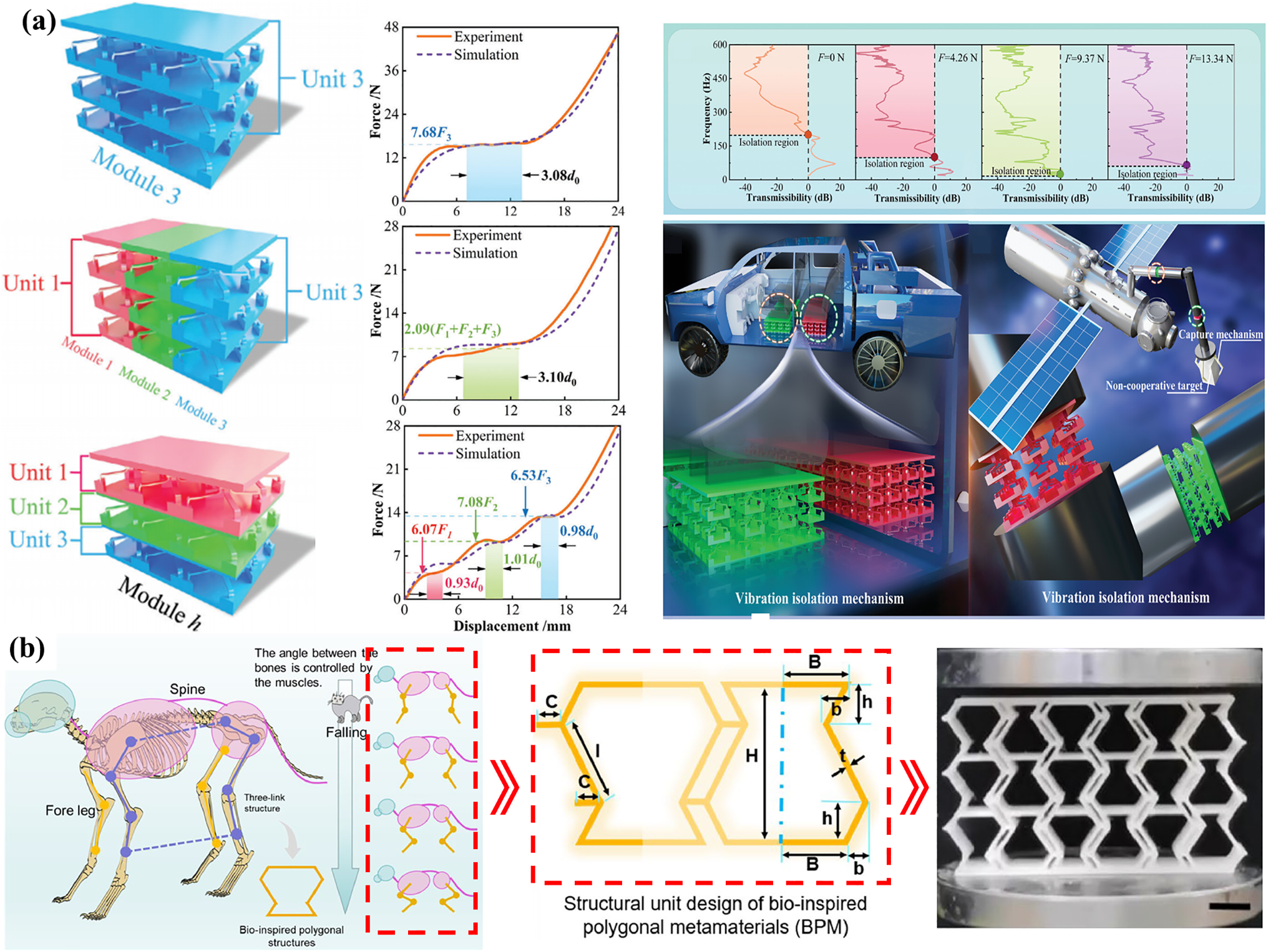

Zeng et al. [150] recently proposed a stepped mechanical metamaterial capable of achieving “zero stiffness” (as shown in Fig. 7a). These materials are constructed using a three-layer strategy of unit cells, modules, and 3D objects. These metamaterials offer excellent vibration-isolation performance, opening new possibilities for customizing force-displacement curves and providing opportunities to integrate multimodal vibration-isolation functions into precision equipment. Additionally, Guo et al. [151] provided a detailed discussion on the ability of gradient metamaterials to manipulate wavefronts and illustrated that by altering structural parameters, the acoustic response of unit cells (phase or amplitude) can be controlled. All these works show that it is feasible to utilize variable frequency band metamaterials in vibration isolation and lay a theoretical foundation for future application.

Figure 7: Prospect and direction of polymer vibration-isolation metamaterial applications. (a) Variable band stepped metamaterials [150] (Copyright 2024, with permission from John Wiley and Sons), (b) Variable stiffness metamaterials inspired by bionic structures [154] (Copyright 2024, with permission from Elsevier), (c) Mortise and tenon vibration-isolation inspired by ancient architectural structures [155] (Copyright 2024, with permission from Creative Commons 4.0)

5.1.2 Bionic Structured Metamaterials

The concept of bionic structure vibration-isolation metamaterials is inspired by natural biological structures to design artificial materials with exceptional vibration-isolation capabilities. By emulating the hierarchical, lightweight, and energy-dissipative characteristics observed in systems such as bones, plant stems, and animal shells, these metamaterials exhibit superior mechanical performance [152,153]. Integrating bionic design principles with advanced material engineering allows for the creation of structures with tailored vibration-isolation properties, including efficient energy absorption and adaptive responses.

As shown in Fig. 7b, Zhou et al. [154], drawing inspiration from the safe landing mechanism of cats falling from heights, proposed a bioinspired polygonal skeleton structure (Fig. 7b) to explore its potential applications in vibration isolation. Their study revealed that by adjusting the distance between the bioinspired legs and the extensibility of the spine, the structure can transition from nonlinear positive stiffness to negative stiffness, effectively suppressing vibrations under various excitations.

5.1.3 Antique Architectural Metamaterials

Inspired by the ingenious structural designs of ancient architecture, vibration-isolation metamaterials integrate traditional building techniques with modern material science. Historical structures, such as timber frameworks and interlocking joints, exhibit remarkable resilience to vibrations, particularly seismic forces, due to their structural flexibility and energy-dissipation mechanisms [145,149]. By applying these design principles to contemporary metamaterials, innovative solutions can be developed that utilize geometry, material properties, and structural configurations. These biomimetic metamaterials mimic the load distribution and damping characteristics of ancient architecture, delivering superior vibration-isolation performance for applications in civil engineering, cultural heritage preservation, and modern infrastructure.

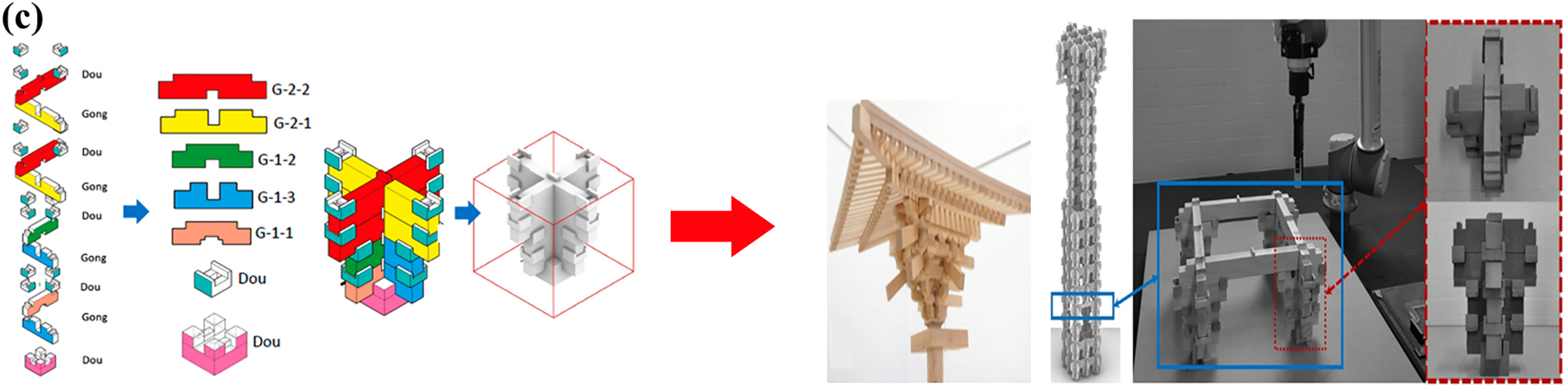

As shown in Fig. 7c, Zhao et al. [155] introduced Dougong (a set of brackets), providing a new perspective that emphasizes the long history of traditional Chinese mortise-and-tenon structures in vibration isolation. By joining and fixing wooden blocks of different structures, an environmentally friendly and reliable vibration-isolation structure can be achieved, providing new ideas for polymer metamaterials.

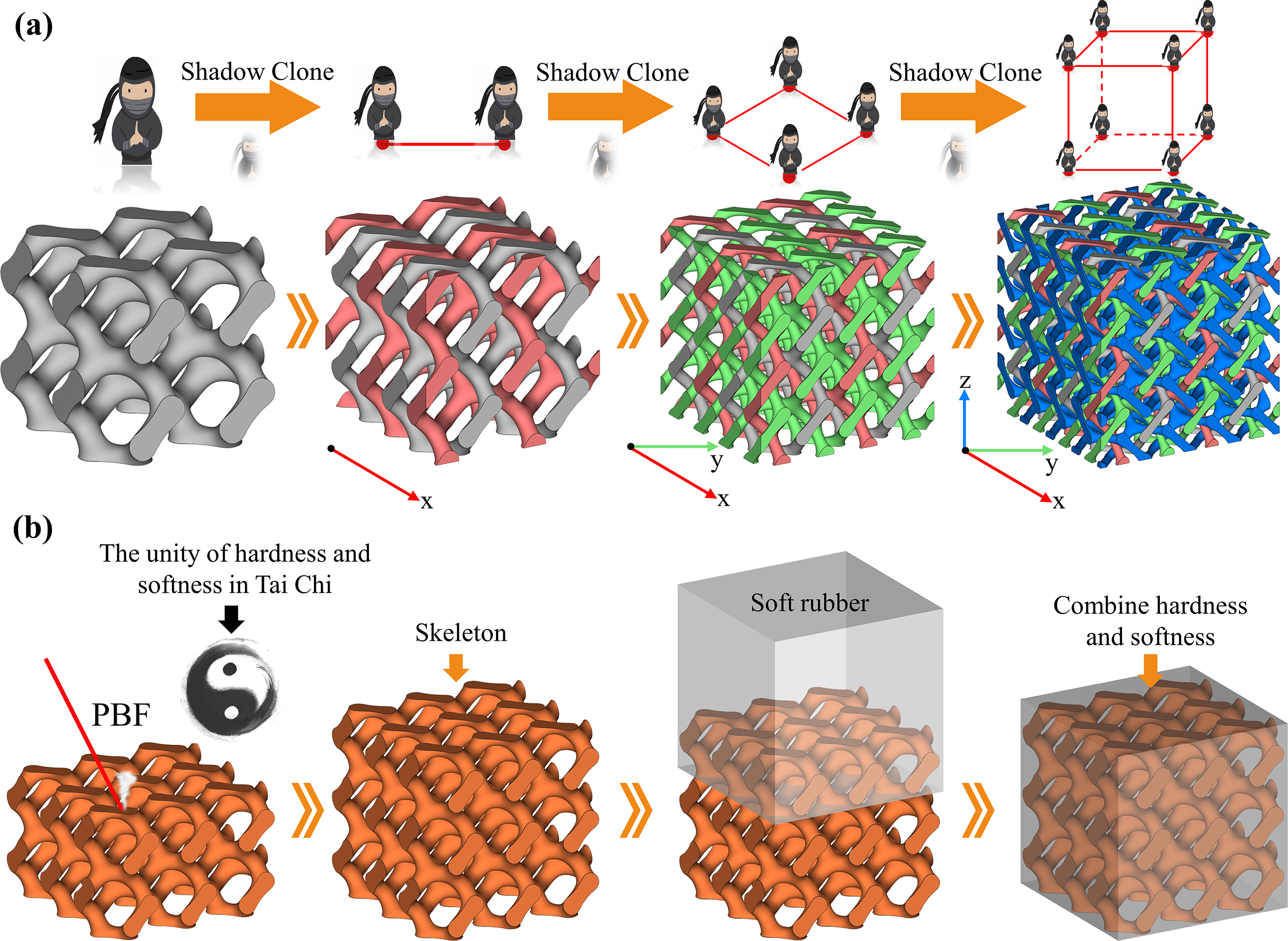

As research on metamaterials deepens, how to break through traditional design frameworks to achieve multifunctionality and dynamic adaptability has become an important challenge. This paper proposes an innovative design concept based on cultural metaphors, integrating the dynamic cloning idea of Japan’s “Shadow Clone” ninjutsu with the philosophical wisdom of China’s Daoist “combine Hardness and Softness,” providing a new perspective for the development and application of future metamaterials (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Vibration isolation inspired by Japanese Ninjutsu and Chinese Taoism: (a) “Shadow Clone” multiple metamaterial, (b) “ Hardness and Softness” complex phase metamaterial

The “Shadow Clone” in Japanese ninjutsu achieves multi-task collaboration through cloning, inspiring researchers to design metamaterials with dynamic reconfigurable characteristics. Such materials can achieve multimodal responses through embedded intelligent units (such as shape memory polymers, piezoelectric materials, or electromagnetic drive structures) (Fig. 8a). For example, in the ship shaft system, metamaterials can adjust the local resonance frequency in real-time according to changes in propeller speed, forming multiple dynamic “clones” to suppress vibrations across different frequency bands. Specifically, when the shaft system encounters low-frequency vibrations, the units trigger local resonance bandgaps through stiffness adjustments. In aerospace applications, periodically arranged phononic crystal structures block the transmission of high-frequency vibrations through Bragg scattering. This multimodal collaborative mechanism is similar to the decentralized control strategy of “Shadow Clone,” significantly broadening the effective vibration-isolation bandwidth and adapting to dynamic load requirements under complex working conditions.

The Daoist concept of “Combination of Hardness and Softness” emphasizes the balance between rigidity and flexibility, which can be mapped to the multi-scale composite design of metamaterials. As shown in Fig. 8b, by combining a high-rigidity framework (such as carbon fiber reinforced polymers) with a high-damping flexible phase (such as soft rubber), gradient or interwoven structures can be formed to achieve synergistic optimization of load-bearing and vibration isolation. In the fields of shipping or aerospace, the rigid skeleton can bear mechanical loads, while the internal flexible damping layer absorbs vibrational energy through viscoelastic dissipation and interfacial friction mechanisms, simultaneously meeting the dual requirements of lightweight design and high load capacity.

This review systematically analyzes current research on polymer metamaterials for vibration isolation from three key aspects. First, it discusses the vibration-isolation mechanisms of metamaterials, emphasizing three primary mechanisms: phononic crystals, local resonance, and energy dissipation. Second, it highlights application examples of vibration-isolation metamaterials in the polymer field, revealing the potential of mainstream polymers and their material advantages in developing efficient vibration-isolation structures. Finally, it comprehensively reviews advancements in AM techniques and their applications in fabricating complex polymer metamaterials, including MJ, VP, and PBF. These technological advancements not only enhance the manufacturing precision and design flexibility of polymer metamaterials but also lay a solid foundation for their broad application in vibration isolation. Additionally, based on existing studies, this review outlines future development directions for polymer metamaterials, suggesting that variable frequency bands, bio-inspired structures, and ancient architectural designs could offer valuable inspiration for exploring their applications in vibration isolation, and combines traditional ideas with the development of metamaterials.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52475398, 52235008, and U2341270).

Author Contributions: Paper conception and design: Lei Yang, Jiefei Huang; data collection: Jiefei Huang, Hao Zhou, Mengying Chen; analysis and interpretation of results: Jiefei Huang, Hao Zhou, Mengying Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Jiefei Huang, Hao Zhou, Mengying Chen; reviewing it critically for important intellectual content: Lei Yang; final approval of the version to be published: Lei Yang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This study did not generate any new datasets. All data analyzed are from publicly available sources, as cited in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ledezma-Ramírez DF, Tapia-González PE, Ferguson N, Brennan M, Tang B. Recent advances in shock vibration isolation: an overview and future possibilities. Appl Mech Rev. 2019;71(6):060802. doi:10.1115/1.4044190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mao HB, Huang YZ, Yang TL. Isolation performance analysis of a porous material vibration isolator. Appl Mech Mater. 2015;741:405–10. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.741.405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li Y, Baker E, Reissman T, Sun C, Liu WK. Design of mechanical metamaterials for simultaneous vibration isolation and energy harvesting. Appl Phys Lett. 2017;111(25):251903. doi:10.1063/1.5008674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Elmadih W, Chronopoulos D, Syam WP, Maskery I, Meng H, Leach RK. Three-dimensional resonating metamaterials for low-frequency vibration attenuation. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):11503. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-47644-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. An X, Lai C, He W, Fan H. Three-dimensional meta-truss lattice composite structures with vibration isolation performance. Extreme Mech Lett. 2019;33:100577. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2019.100577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gao N, Zhang Z, Deng J, Guo X, Cheng B, Hou H. Acoustic metamaterials for noise reduction: a review. Adv Mater Technol. 2022;7(6);2100698. doi:10.1002/admt.202100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Grimberg R. Electromagnetic metamaterials. Mater Sci Eng B. 2013;178(19):1285–95. doi:10.1016/j.mseb.2013.03.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen J, Wang H, Wang K, Wei Z, Xu W, Wei K. Mechanical performances and coupling design for the mechanical metamaterials with tailorable thermal expansion. Mech Mater. 2022;165:104176. doi:10.1016/j.mechmat.2021.104176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tanaka T, Ishikawa A. Towards three-dimensional optical metamaterials. Nano Converg. 2017;4(1):34. doi:10.1186/s40580-017-0129-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Qin H, Yang D. Vibration reduction design method of metamaterials with negative Poisson's ratio. J Mater Sci. 2019;54(22):14038–54. doi:10.1007/s10853-019-03903-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Andrew JJ, Verma P, Kumar S. Impact behavior of nanoengineered, 3D printed plate-lattices. Mater Des. 2021;202(29):109516. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2021.109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Oladapo BI, Ismail SO, Ikumapayi OM, Karagiannidi PG. Impact of rGO-coated PEEK and lattice on bone implant. Colloids Surf B. 2022;216:112583. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Tao Z, Ren X, Zhao AG, Sun L, Zhang Y, Jiang W, et al. A novel auxetic acoustic metamaterial plate with tunable bandgap. Int J Mech Sci. 2022;226(5):107414. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2022.107414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang Z, Zhang Q, Zhang K, Hu G. Tunable digital metamaterial for broadband vibration isolation at low frequency. Adv Mater. 2016;28(44):9857–61. doi:10.1002/adma.201604009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Hur K, Hennig RG, Wiesner U. Exploring periodic bicontinuous cubic network structures with complete phononic bandgaps. J Phys Chem C. 2017;121(40):22347–52. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b07267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jiao P, Mueller J, Raney JR, Zheng XR, Alavi AH. Mechanical metamaterials and beyond. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):6004. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-41679-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Almesmari A, Baghous N, Ejeh CJ, Barsoum I, Abu Al-Rub RK. Review of additively manufactured polymeric metamaterials: design, fabrication, testing and modeling. Polymers. 2023;15(19):3858. doi:10.3390/polym15193858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Veerabagu U, Palza H, Quero F. Review: auxetic polymer-based mechanical metamaterials for biomedical applications. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022;8(7):2798–824. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.2c00109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Yin S, Rayess N. Characterization of polymer-metal foam hybrids for use in vibration dampening and isolation. Procedia Mater Sci. 2014;4:311–6. doi:10.1016/j.mspro.2014.07.564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Surjadi JU, Gao L, Du H, Li X, Xiong X, Fang NX, et al. Mechanical metamaterials and their engineering applications. Adv Eng Mater. 2019;21(3):1800864. doi:10.1002/adem.201800864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Askari M, Hutchins DA, Thomas PJ, Astolfi L, Watson RL, Abdi M, et al. Additive manufacturing of metamaterials: a review. Addit Manuf. 2020;36:101562. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2020.101562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Khan I, Farooq U, Tariq M, Abas M, Ahmad S, Shakeel M, et al. Investigation of effects of processing parameters on the impact strength and microstructure of thick tri-material based layered composite fabricated via extrusion based additive manufacturing. J Eng Res-Kuwait. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.jer.2023.08.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Khan I, Barsoum I, Abas M, Rashid AA, Koç M, Tariq M. A review of extrusion-based additive manufacturing of multi-materials-based polymeric laminated structures. Compos Struct. 2024;349-50:118490. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2024.118490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sanz-Pena I, Hopkins M, Carrero NR, Xu H. Embedded pressure sensing metamaterials using TPU-graphene composites and additive manufacturing. IEEE Sens J. 2023;23(15):16656–64. doi:10.1109/JSEN.2023.3283460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Suhas P, Quadros JD, Mogul YI, Ma M, Abdul A, Muneer B, et al. A review of mechanical metamaterials and additively manufacturing techniques for biomedical applications. Mater Adv. 2025;6(3):887–908. doi:10.1039/D4MA00874J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ji JC, Luo Q, Ye K. Vibration control based metamaterials and origami structures: a state-of-the-art review. Mech Syst Signal Pr. 2021;161:107945. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.107945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yan S, Wu L, Meng Z, Tan X, Liu W, Wen Y, et al. Double-strip metamaterial for vibration isolation and shock attenuation. Int J Mech Sci. 2024;282:109686. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2024.109686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sun P, Xu S, Wang X, Gu L, Luo X, Zhao C, et al. Sound absorption of space-coiled metamaterials with soft walls. Int J Mech Sci. 2024;261:108696. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2023.108696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhou J, Li LT. Metamaterial technology and its application prospects. Strateg Stud Chin Acad Eng. 2018;20(6):69–74. doi:10.15302/J-SSCAE-2018.06.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Li X, Ning S, Liu Z, Yan Z, Luo C, Zhuang Z. Designing phononic crystal with anticipated band gap through a deep learning based data-driven method. Comput Method Appl M. 2020;361(36):112737. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2019.112737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang R, Ding W, Fang B, Feng P, Wang K, Chen T, et al. Syndiotactic chiral metastructure with local resonance for low-frequency vibration isolation. Int J Mech Sci. 2024;281:109564. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2024.109564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang C, Ali A. The advancement of seismic isolation and energy dissipation mechanisms based on friction. Soil Dyn Earthq Eng. 2021;146:106746. doi:10.1016/j.soildyn.2021.106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sun X, Jing X, Xu J, Cheng L. Vibration isolation via a scissor-like structured platform. J Sound Vib. 2014;333(9):2404–20. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2013.12.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kumar R, Kumar M, Chohan JS, Kumar S. Overview on metamaterial: history, types and applications. Mater Today Proc. 2022;56(11):3016–24. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.11.423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Maurya SK, Pandey A, Shukla S, Saxena S. Double negativity in 3D space coiling metamaterials. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):33683. doi:10.1038/srep33683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Dalela S, Balaji PS, Jena DP. A review on application of mechanical metamaterials for vibration control. Mech Adv Mater Struc. 2022;29(22):3237–62. doi:10.1080/15376494.2021.1892244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Huang HH, Sun CT, Huang GL. On the negative effective mass density in acoustic metamaterials. Int J Eng Sci. 2009;47(4):610–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijengsci.2008.12.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li Y, Zhang H. Band gap mechanism and vibration attenuation characteristics of the quasi-one-dimensional tetra-chiral metamaterial. Eur J Mech A Solids. 2022;92(1):104478. doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2021.104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang P, Shim J, Bertoldi K. Effects of geometric and material nonlinearities on tunable band gaps and low-frequency directionality of phononic crystals. Phys Rev B Condens Matter Mater Phys. 2013;88(1):014304. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.88.014304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ma T, Su X, Wang Y, Wang Y. Effects of material parameters on elastic band gaps of three-dimensional solid phononic crystals. Phys Scripta. 2013;87(5):055604. doi:10.1088/0031-8949/87/05/055604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Javid F, Wang P, Shanian A, Bertoldi K. Architected materials with ultra-low porosity for vibration control. Adv Mater. 2016;28(28):5943–8. doi:10.1002/adma.201600052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Elmadih W, Syam WP, Maskery I, Chronopoulos D, Leach R. Mechanical vibration bandgaps in surface-based lattices. Addit Manuf. 2019;25:421–9. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2018.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Sugino C, Xia Y, Leadenham S, Ruzzene M, Erturk A. A general theory for bandgap estimation in locally resonant metastructures. J Sound Vib. 2017;406(13):104–23. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2017.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ma H, Wang K, Zhao H, Zhao C, Xue J, Liang C, et al. Harnessing chiral buckling structure to design tunable local resonance metamaterial for low-frequency vibration isolation. J Sound Vib. 2023;565:117905. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2023.117905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Yang XW, Lee JS, Kim YY. Effective mass density based topology optimization of locally resonant acoustic metamaterials for bandgap maximization. J Sound Vib. 2016;383:89–107. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2016.07.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Pan P, Ye L, Shi W, Cao H. Engineering practice of seismic isolation and energy dissipation structures in China. Sci China Technol Sci. 2012;55(11):3036–46. doi:10.1007/s11431-012-4922-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Liu C, Jing X, Daley S, Li F. Recent advances in micro-vibration isolation. Mech Syst Signal Pr. 2015;56(3):55–80. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2014.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhou XQ, Yu DY, Shao XY, Zhang SQ, Wang S. Research and applications of viscoelastic vibration damping materials: a review. Compos Struct. 2016;136:460–80. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2015.10.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Benjeddou A. Advances in hybrid active-passive vibration and noise control via piezoelectric and viscoelastic constrained layer treatments. J Vib Control. 2001;7(4):565–602. doi:10.1177/107754630100700406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Babaei B, Velasquez-Mao AJ, Pryse KM, McConnaughey WB, Elson EL, Genin GM. Energy dissipation in quasi-linear viscoelastic tissues, cells, and extracellular matrix. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2018;84:198–207. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.05.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Jia J, Shen X, Hua H. Viscoelastic behavior analysis and application of the fractional derivative maxwell model. J Vib Control. 2007;13(4):385–401. doi:10.1177/1077546307076284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Liu H, Yang B, Wang C, Han Y, Liu D. The mechanisms and applications of friction energy dissipation. Friction. 2023;11(6):839–64. doi:10.1007/s40544-022-0639-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. López I, Busturia JM, Nijmeijer H. Energy dissipation of a friction damper. J Sound Vib. 2004;278(3):539–61. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2003.10.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Patil DB, Eriten M. Effect of roughness on frictional energy dissipation in presliding contacts. J Tribol. 2016;138(1):011401. doi:10.1115/1.4031185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Park JY, Salmeron M. Fundamental aspects of energy dissipation in friction. Chem Rev. 2014;114(1):677–711. doi:10.1021/cr200431y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Liang K, Jing Y, Zhang X. Design of broad quasi-zero stiffness platform metamaterials for vibration isolation. Int J Mech Sci. 2024;281:109691. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2024.109691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Li Z, Zeng K, Guo Z, Wang Z, Yu X, Li X, et al. All-in-one: an interwoven dual-phase strategy for acousto-mechanical multifunctionality in microlattice metamaterials. Adv Funct Mater. 2024. doi:10.1002/adfm.202420207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Abueidda DW, Bakir M, Al-Rub RKAbu, Bergström JS, Sobh NA, Jasiuk I. Mechanical properties of 3D printed polymeric cellular materials with triply periodic minimal surface architectures. Mater Des. 2017;122(9):255–67. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2017.03.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Chen Y, Wang L. Harnessing structural hierarchy to design stiff and lightweight phononic crystals. Extreme Mech Lett. 2016;9(9–10):91–6. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2016.05.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Yavas D, Liu Q, Zhang Z, Wu D. Design and fabrication of architected multi-material lattices with tunable stiffness, strength, and energy absorption. Mater Des. 2022;217(8):110613. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2022.110613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Lipton JI. Material jetting of suspension system components. In: International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium; 2023 Aug 14–16; Austin, TX, USA. p. 1998–2005. doi:10.26153/tsw/51098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Yao Z, Zhao R, Zega V, Corigliano A. A metaplate for complete 3D vibration isolation. Eur J Mech A Solids. 2020;84:104016. doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2020.104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Syam WP, Jianwei W, Zhao B, Maskery I, Elmadih W, Leach R. Design and analysis of strut-based lattice structures for vibration isolation. Precis Eng. 2018;52:494–506. doi:10.1016/j.precisioneng.2017.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Ding H, Huang N, Xu C, Xu Y, Cao Z, Zeng C, et al. A locally resonant metamaterial and its application in vibration isolation: experimental and numerical investigations. Earthq Eng Struct D. 2024;53(13):4099–113. doi:10.1002/eqe.4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Sireesha M, Lee J, Kranthi KA, Babu VJ, Kee B, Ramakrishna S. A review on additive manufacturing and its way into the oil and gas industry. RSC Adv. 2018;8(40):22460–8. doi:10.1039/C8RA03194K. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Zhang F, Zhu L, Li Z, Wang S, Shi J, Tang W, et al. The recent development of vat photopolymerization: a review. Addit Manuf. 2021;48(6109):102423. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2021.102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Nouri A, Rohani Shirvan A, Li Y, Wen C. Additive manufacturing of metallic and polymeric load-bearing biomaterials using laser powder bed fusion: a review. J Mater Sci Technol. 2021;94:196–215. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2021.03.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Gibson I, Rosen DW, Stucker B, Khorasani M. Additive manufacturing technologies. 3rd ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2021. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-56127-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Ingaglio J, Fox J, Naito CJ, Bocchini P. Material characteristics of binder jet 3D printed hydrated CSA cement with the addition of fine aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2019;206(4):494–503. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.02.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Ahn D, Kweon J, Choi J, Lee S. Quantification of surface roughness of parts processed by laminated object manufacturing. J Mater Process Tech. 2012;212(2):339–46. doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2011.08.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Ramola M, Yadav V, Jain R. On the adoption of additive manufacturing in healthcare: a literature review. J Manuf Technol Mana. 2019;30(1):48–69. doi:10.1108/JMTM-03-2018-0094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Salmi M, Paloheimo K, Tuomi J, Wolff J, Mäkitie A. Accuracy of medical models made by additive manufacturing (rapid manufacturing). J Cranio Maxill Surg. 2013;41(7):603–9. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2012.11.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Lee K, Cho J, Chang N, Chae J, Kang K, Kim S, et al. Accuracy of three-dimensional printing for manufacturing replica teeth. Korean J Orthod. 2015;45(5):217–25. doi:10.4041/kjod.2015.45.5.217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Dizon JRC, Valino AD, Souza LR, Espera AH, Chen Q, Advincula RC. 3D printed injection molds using various 3D printing technologies. Mater Sci Forum. 2020;1005(1):150–6. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.1005.150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Brown-Moore TK, Balaji S, Williams T, Jeffrey L. Fabrication of liquid-filled voronoi foams for impact absorption using material jetting technology. In: 2022 International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium; 2022 Jul 25–27; Austin, TX, USA. p. 653–60. doi:10.26153/tsw/44187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Mora S, Pugno NM, Misseroni D. 3D printed architected lattice structures by material jetting. Mater Today. 2022;59(5):107–32. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2022.05.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Vdovin R, Tomilina T, Smelov V, Laktionova M. Implementation of the additive polyjet technology to the development and fabricating the samples of the acoustic metamaterials. Procedia Eng. 2017;176:595–9. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.02.302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Janbaz S, Bobbert FSL, Mirzaali MJ, Zadpoor AA. Ultra-programmable buckling-driven soft cellular mechanisms. Mater Horiz. 2019;6(6):1138–47. doi:10.1039/C9MH00125E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Yu K, Du H, Xin A, Lee KH, Feng Z, Masri SF, et al. Healable, memorizable, and transformable lattice structures made of stiff polymers. NPG Asia Mater. 2020;12(1):26. doi:10.1038/s41427-020-0208-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Alessandro LD, Zega V, Ardito R, Corigliano A. 3D auxetic single material periodic structure with ultra-wide tunable bandgap. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2262. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-19963-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Zhou S, Liu G, Chen A, Su J, Zhang Y, Wang C, et al. Effect of molecular weight and chemical structure of plasticizer on suspension property, binder removal, and sintered performance for zirconia toughened alumina ceramics fabricated by vat photopolymerization. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2024;44(15):116730. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2024.116730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Xu X, Zhou S, Wu J, Zhang C, Liu X. Inter-particle interactions of alumina powders in UV-curable suspensions for DLP stereolithography and its effect on rheology, solid loading, and self-leveling behavior. J Eur Ceram Soc. 2021;41(4):2763–74. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Xu X, Zhou S, Wu J, Liu Y, Wang Y, Chen Z. Relationship between the adhesion properties of UV-curable alumina suspensions and the functionalities and structures of UV-curable acrylate monomers for DLP-based ceramic stereolithography. Ceram Int. 2021;47(23):32699–709. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.08.166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Wu H, Fahy WP, Kim S, Kim H, Zhao N, Pilato L, et al. Recent developments in polymers/polymer nanocomposites for additive manufacturing. Prog Mater Sci. 2020;111:100638. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2020.100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Celikci N, Ziba CA, Dolaz M, Tümer M. Comparison of composite resins containing UV light-sensitive chitosan derivatives in stereolithography (SLA)-3D printers. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;281:136057. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Mukhtarkhanov M, Perveen A, Talamona D. Application of stereolithography based 3D printing technology in investment casting. Micromachines. 2020;11(10):946. doi:10.3390/mi11100946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Weng Z, Zhou Y, Lin W, Senthil T, Wu L. Structure-property relationship of nano enhanced stereolithography resin for desktop SLA 3D printer. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2016;88(1):234–42. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2016.05.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Wang J, Goyanes A, Gaisford S, Basit AW. Stereolithographic (SLA) 3D printing of oral modified-release dosage forms. Int J Pharmaceut. 2016;503(1–2):207–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.03.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Carlotti M, Mattoli V. Functional materials for two-photon polymerization in microfabrication. Small. 2019;15(40):1902687. doi:10.1002/smll.201902687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Pagac M, Hajnys J, Ma Q, Jancar L, Jansa J, Stefek P, et al. A review of vat photopolymerization technology: materials, applications, challenges, and future trends of 3D printing. Polymers. 2021;13(4):598. doi:10.3390/polym13040598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Grigoryan B, Paulsen SJ, Corbett DC, Sazer DW, Fortin CL, Zaita AJ, et al. Multivascular networks and functional intravascular topologies within biocompatible hydrogels. Science. 2019;364(6439):458–64. doi:10.1126/science.aav9750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Li Y, Mao Q, Yin J, Wang Y, Fu J, Huang Y. Theoretical prediction and experimental validation of the digital light processing (DLP) working curve for photocurable materials. Addit Manuf. 2021;37(2):101716. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2020.101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Faraji Rad Z, Prewett PD, Davies GJ. High-resolution two-photon polymerization: the most versatile technique for the fabrication of microneedle arrays. Microsyst Nanoeng. 2021;7(1):71. doi:10.1038/s41378-021-00298-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Liberale C, Cojoc G, Candeloro P, Das G, Gentile F, De Angelis F, et al. Micro-optics fabrication on top of optical fibers using two-photon lithography. IEEE Photonic Tech L. 2010;22(7):474–6. doi:10.1109/LPT.2010.2040986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Zega V, Pertoldi L, Zandrini T, Osellame R, Comi C, Corigliano A. Microstructured phononic crystal isolates from ultrasonic mechanical vibrations. Appl Sci. 2022;12(5):2499. doi:10.3390/app12052499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]