Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Unveiling Ionic Conductivity and Ion Transport Properties in Polyvinyl Alcohol-Based Gel Polymer Electrolytes with Quaternary Ammonium Iodide

1 School of Physics, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, 11800, Malaysia

2 Energy Studies Research Group, School of Physics, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, 11800, Malaysia

* Corresponding Authors: M. F. Aziz. Email: ; A. R. M. Rais. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 1097-1109. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.071129

Received 01 August 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

To study the behavior of structural dynamics, ionic conductivity and ion transport properties, the gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) was developed using polyvinyl alcohol in combination with potassium iodide, dimethyl sulfoxide, ethylene carbonate, propylene carbonate and tetra-N-propylammonium iodide (C12H28IN), The GPEs were synthesized via a solution mixing technique, systematically varying the tetra-N-propylammonium iodide concentration to optimize ionic transport properties. The gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) preparation was initially dissolving the potassium iodide and tetra-N-propylammonium iodide in a measured combination of ethylene carbonate, propylene carbonate, and dimethyl sulfoxide within a glass container. Subsequently, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was introduced into the salt solution and continuously stirred at 100°C until a uniform mixture was formed. The solution was then allowed to cool to 30°C and resulting GPE exhibited a gel-like consistency. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was employed to evaluate ionic conductivity, dielectric behavior, and ion transport properties at the temperature of 25°C. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was utilized to investigate the structure of the gel polymer electrolyte. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was applied to describe the structural interactions between salts and polymer in the GPEs. Notably, the gel polymer electrolytes containing 30 wt.% tetra-N-propylammonium iodides exhibited a remarkable ionic conductivity of approximately 9.70 mS cm−1 at the temperature of 25°C.Keywords

The exploration and development of polymer electrolytes have attracted considerable attention as potential alternatives to conventional liquid electrolytes in electrochemical energy storage systems such as lithium-ion batteries, supercapacitors, and dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) [1–3]. Polymer electrolytes consist of polymer matrices embedded with ionic salts, which facilitate ionic conduction while providing mechanical stability and improved safety compared to liquid systems [4–6]. Their advantages include broad electrochemical stability windows, excellent thermal resistance, good mechanical properties, and significantly reduced leakage risks [7,8].

Polymer electrolytes are generally classified into two main types: solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) and gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs), based on their physical structure and interaction with solvents [9,10]. Recent studies have highlighted GPEs as especially promising due to their ability to combine the ionic conductivity of liquid electrolytes with the mechanical integrity of solids [11]. In GPEs, the polymer matrix effectively immobilizes the liquid component, thus enhancing safety by preventing leakage and maintaining dimensional stability. Notably, GPEs have demonstrated room-temperature ionic conductivity values in the range of 10−4 to 10−3 S cm−1, approaching the performance of conventional liquid electrolytes [12–14].

A wide variety of host polymers have been investigated for use in GPEs. Commonly studied polymers include polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyacrylonitrile (PAN), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), and polyethylene oxide (PEO) [15–19]. Among these, PVA has particular interest due to its desirable characteristics, including high dielectric constant, hydrophilicity, chemical resistance, non-toxic nature, and excellent thermal and mechanical stability [20–22].

The inclusion of dopant salts in the polymer matrix plays a crucial role in enhancing ionic conductivity and electrochemical performance. These salts dissociate into mobile ions, facilitating ion transport during the charge-discharge cycles. The interaction between the polymer host and salt significantly influences both conductivity and mechanical integrity. Salts with low lattice energy, such as iodide (I−) and metal-based salts, tend to dissociate more readily in polar polymer matrices, resulting in improved ion transport behavior [23–25].

In the present work, a gel polymer electrolyte (GPE) system based on polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) incorporating tetra-N-propylammonium-potassium iodide salts was prepared to examine its effect on ionic conductivity. The investigation also extended to elucidate the underlying ionic transport mechanism within the GPE matrix. In addition, X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to study the structural of the GPE and Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to characterize the structural interactions between PVA and the incorporated tetra-N-propylammonium-potassium iodide salts, revealing insights into the polymer-salt dynamic interactions.

2.1 Gel Polymer Electrolytes Preparation

In this research, the ethylene carbonate (EC) and propylene carbonate (PC) were sourced from Sigma Aldrich, while dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was obtained from Friendmann Schmidt Chemicals. Tetra-N-propylammonium iodide (TPAI) and potassium iodide (KI) salts were also supplied by Sigma Aldrich.

For the synthesis of gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs), a specific amount of TPAI and KI was initially dissolved in a measured combination of EC, PC, and DMSO within a glass container (refer Table 1). Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was subsequently added to the salt solution and stirred continuously at 100°C for 4 h. The resulting homogeneous mixture was then cooled to 30°C, after which the prepared GPE was stored in a desiccator containing silica gel to maintain a low-humidity environment and prevent moisture absorption.

2.2 Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Ionic Conductivity

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was employed to elucidate the electrical properties of the GPE samples. The impedances were measured using a HIOKI LCR Hi-Tester AC impedance analyzer, operating within the frequency range of 1 Hz to 100 kHz at the temperature of 25°C. The GPE samples were sandwiched between two stainless steel blocking electrodes. The ionic conductivity (σ) was calculated by extracting the bulk resistance (Rb) from the Nyquist plot, based on Eq. (1).

The thickness of the gel polymer electrolyte (GPE) is denoted by t, while the bulk resistance, Rb is determined from the low-frequency x-axis intercept of the Nyquist plot. The A refers to the effective contact area of the GPE within the cell configuration.

In this study, to gain deeper insights into ion transport properties, key transport parameters, including the diffusion coefficient (D), ionic mobility (μ), and charge carrier number density (n), were scientifically calculated using the following equations [26]:

The relaxation time τ is expressed as τ = 1/ω, where ω represents the angular frequency corresponding to the intercept point at the apex of the Nyquist plot. The symbol kb denotes Boltzmann’s constant, while e is the fundamental electric charge constant (1.602 × 10−19 C). The term k2 is defined as the reciprocal of capacitance C, with C obtained through Nyquist plot fitting analysis. The vacuum permittivity is given by ε0 = 8.85 × 10−14 F cm−1, and εr represents the relative permittivity (dielectric constant) of the material.

The crystalline characteristics of the prepared gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) were investigated by X-ray diffraction measurements employing a BTX-II Olympus Benchtop diffractometer. The diffraction patterns were recorded using Cu Kα radiation, which possesses a wavelength of 1.5406 Å.

2.5 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

The identification of functional groups present in the gel polymer electrolyte, including alkyl, hydroxyl, and amino moieties, was performed using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. In this study, a Nicolet iS10 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) was employed for spectral acquisition. The measurements were conducted over the wavenumber range of 4000 to 650 cm−1, with resolution of 2 cm−1.

3.1 Ionic Conductivity and Ion Transport Properties Analysis

Aziz et al. [27] previously examined the ionic conductivity behavior of poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA)-based gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) incorporating varying concentrations of potassium iodide (KI) at ambient temperature. Their findings revealed that a composition containing 35 wt.% KI demonstrated the highest ionic conductivity, reaching almost at 13 mS cm−1. Motivated by these results, the present investigation extends this work by incorporating a quaternary ammonium-potassium iodide complex, specifically tetra-N-propylammonium potassium iodide, into the PVA matrix to assess its influence on the electrical properties of the resulting GPE.

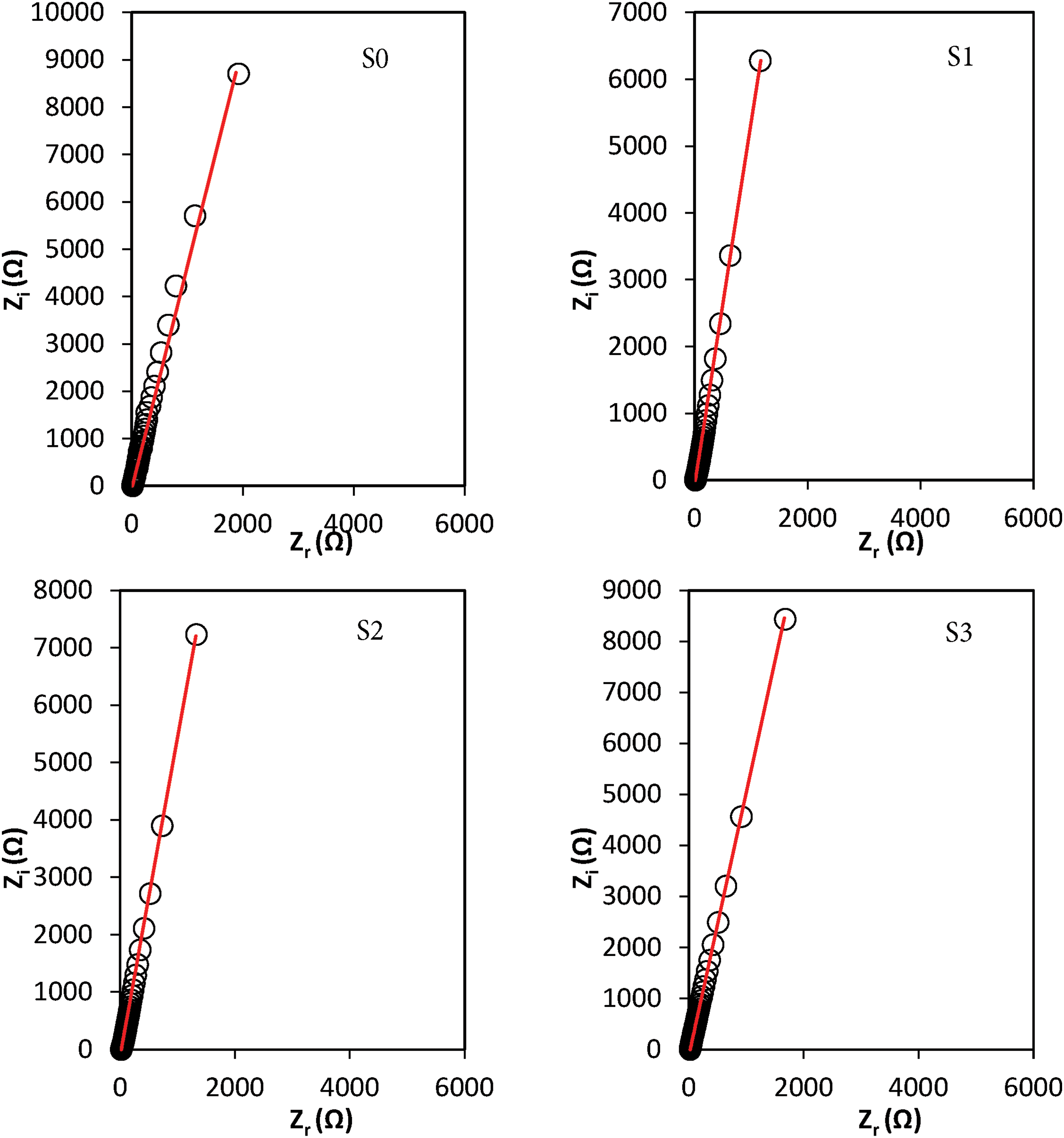

Impedance spectroscopy was employed to determine the bulk resistance (Rb), extracted from the semicircular region of the complex impedance (Nyquist plot). These plots were modeled through iterative parameter fitting to achieve accurate representation, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Each impedance profile exhibited a characteristic tilted spike, indicative of a parallel combination of resistive and capacitive elements. This behavior is commonly attributed to the presence of a constant phase element (CPE), often described as a “leaky capacitor” or bulk capacitance, in series with Rb. The orientation of the spike along the imaginary axis is typically associated with interfacial polarization phenomena at the electrode-electrolyte boundary, consistent with observations reported by Mazuki et al. [26].

Figure 1: Nyquist plot for the GPEs containing various amounts of tetra-N-propylammonium iodide-potassium iodide

The real (Zr) and imaginary (Zi) components of impedance were modeled using the following relationship:

here, R denotes the bulk resistance, p represents the depression angle reflecting non-ideal capacitive behavior, k−1 corresponds to the effective capacitance due to the electrical double layer (EDL), and ω is the angular frequency (2πf). A noticeable reduction in Rb was observed with variation TPAI-KI content, which is attributed to the enhanced concentration and mobility of ionic charge carriers [26].

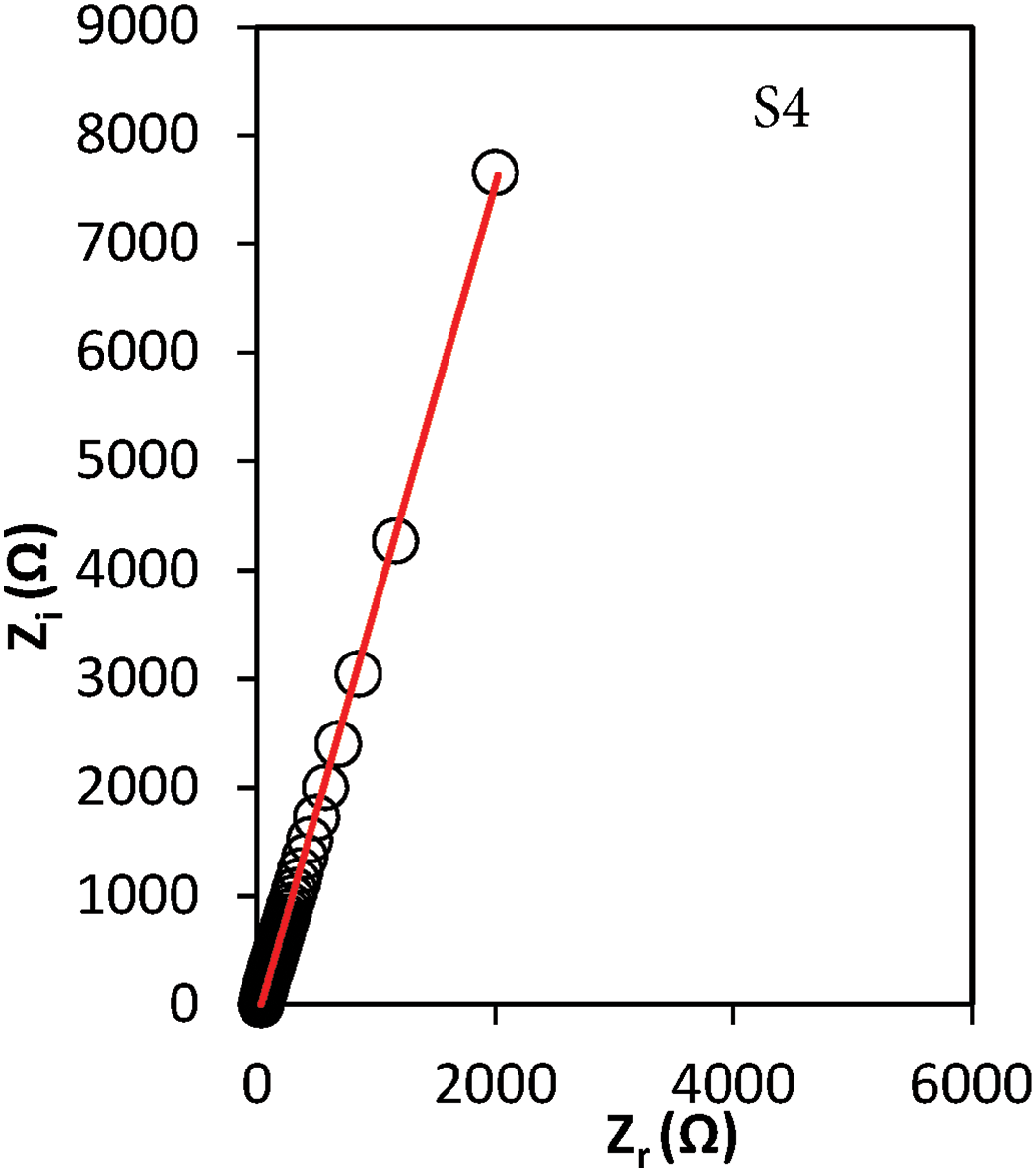

The dielectric response of polymer electrolyte systems complexed with tetra-N-propylammonium-potassium iodide salts was investigated to understand interfacial polarization and charge dynamics. Dielectric constant (εr) variations across frequency at ambient conditions are presented in Fig. 2, which clearly indicates a downward trend with increasing frequency. This decline is attributed to the reduced ability of dipolar and space charge polarization to follow the rapidly alternating electric field at higher frequencies. At lower frequencies, charge carriers tend to accumulate at the electrode-electrolyte interface, enhancing polarization. However, this effect diminishes at higher frequencies due to the periodic field reversal [28]. All GPE compositions exhibited similar behaviour, confirming that interfacial effects dominate the dielectric response in the low-frequency region. Additionally, Nyquist plots revealed only a characteristic spike without a semicircular arc, suggesting minimal bulk contribution and highlighting predominant electrode polarization, which consistent with previous similar polymer–salt systems [21,22].

Figure 2: Frequency dependence of the dielectric constant for GPEs at 25°C

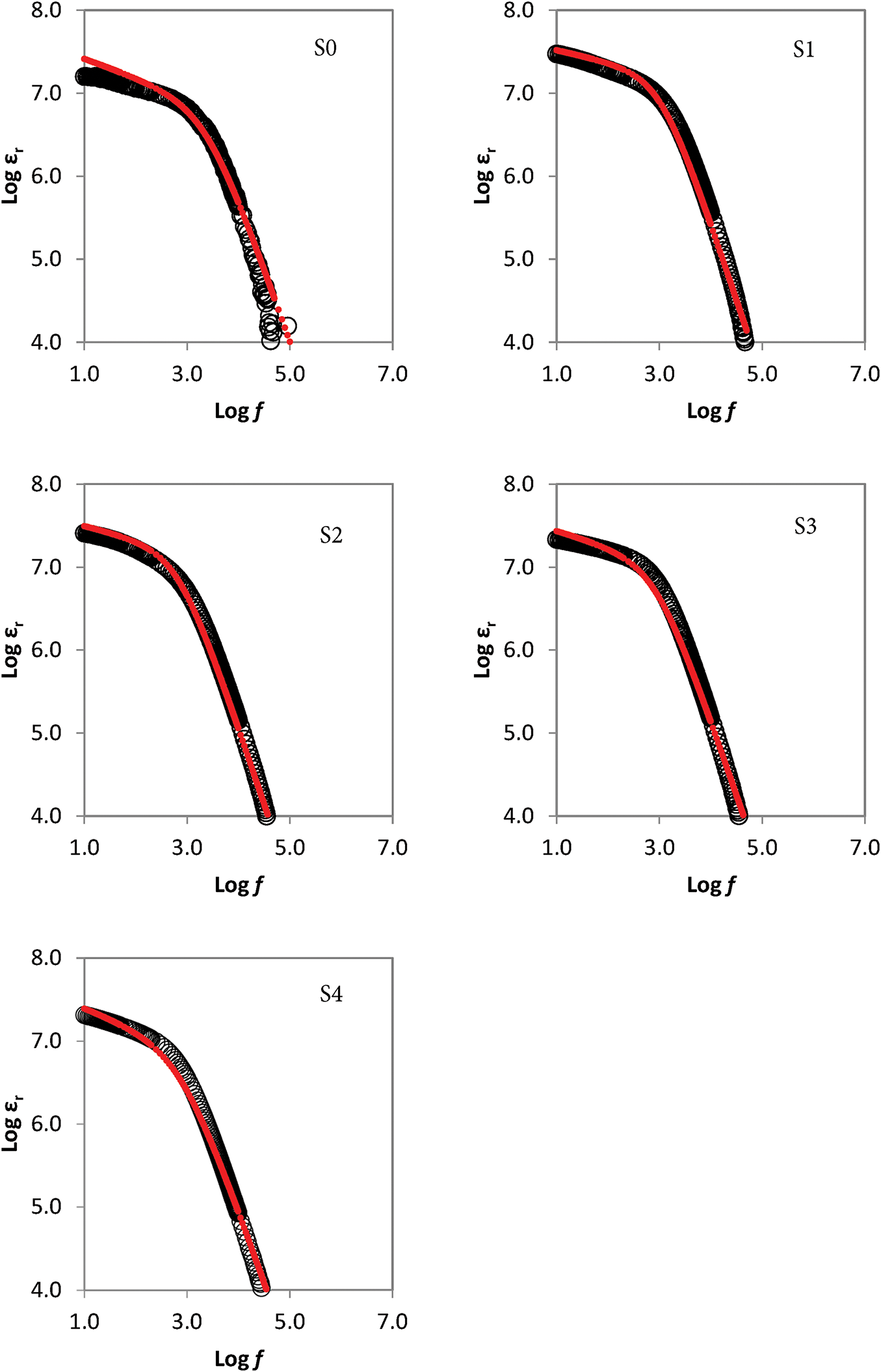

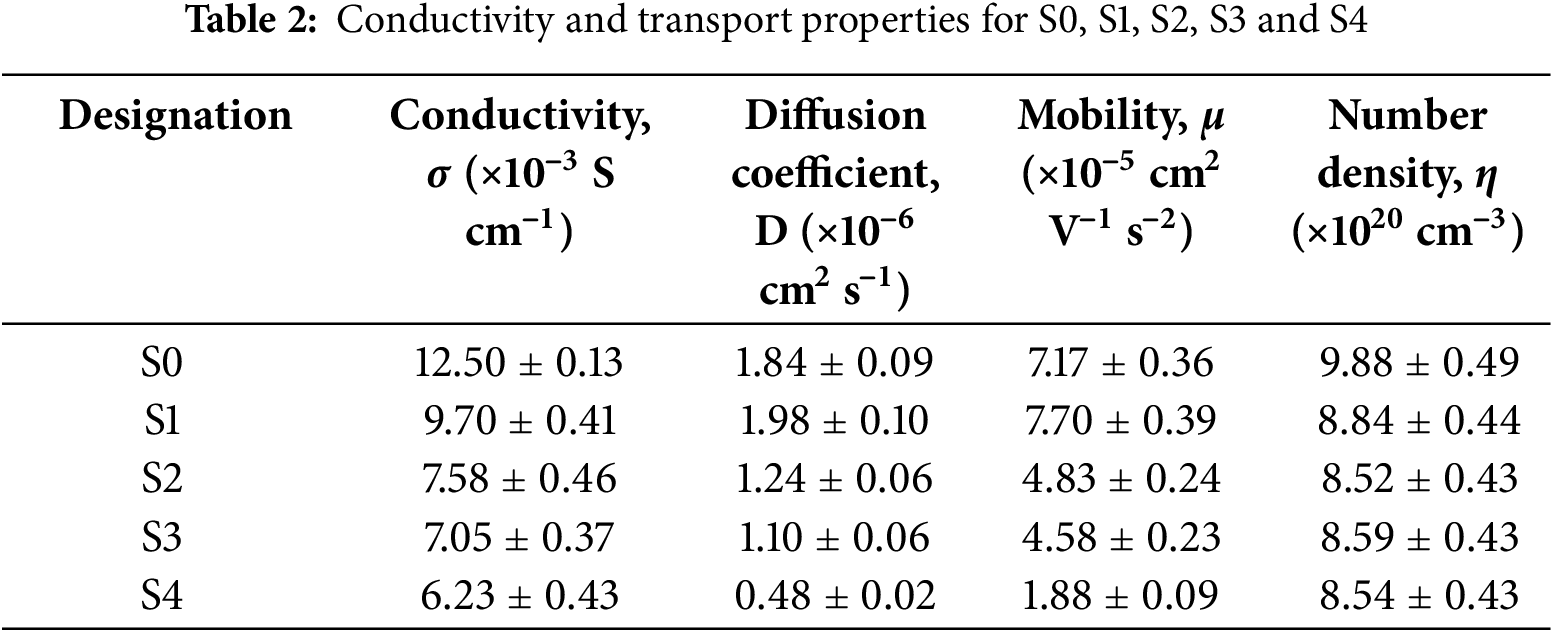

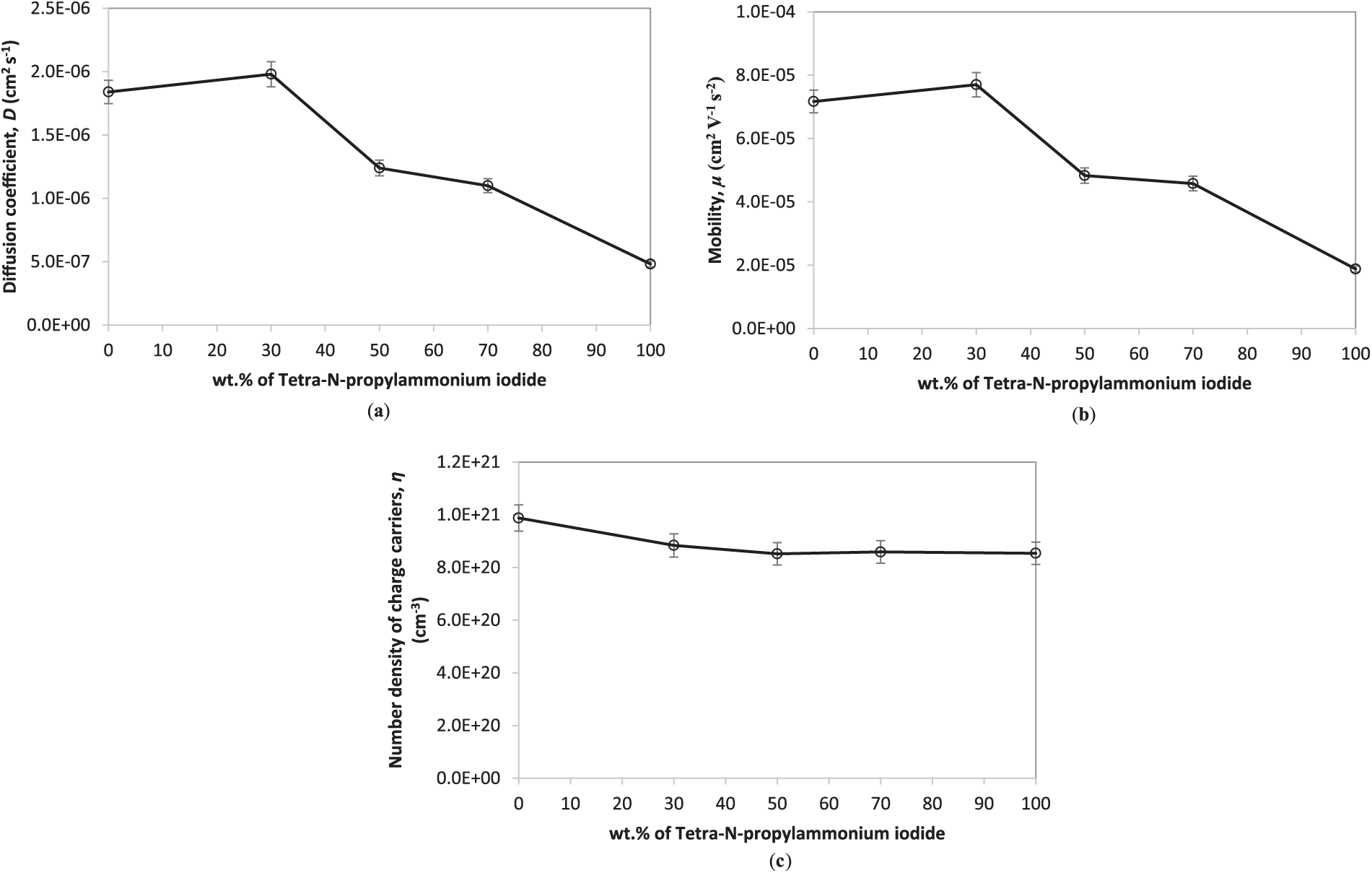

The ion transport behavior in the gel polymer electrolyte (GPE) system was analyzed through impedance spectroscopy using Nyquist plot fitting. Key transport parameters, namely the diffusion coefficient (D), ionic mobility (μ), and ion number density (η), were extracted based on the low-frequency spike characteristic of electrode polarization (refer Table 2). As illustrated in Fig. 3a,b, both μ and D values declined upon the addition of tetrapropylammonium iodide (TPAI) to the polymer electrolyte system. The observed decrease in ionic mobility and diffusivity is primarily associated with the bulky nature of the TPA+ cation, which impedes the segmental motion of the polymer chains and restricts the free volume available for ion migration [12,13]. Furthermore, the strong electrostatic interaction between the quaternary ammonium ions and polymer backbones may reduce the flexibility of the host matrix, thereby limiting ion dissociation and transport [25]. An increase in TPAI content can also promote ion association or clustering, resulting in a lower population of free charge carriers contributing to ionic conduction [14,29].

Figure 3: (a) Diffusion coefficient (D), (b) mobility (μ), and (c) number density of charge carriers (η) for GPEs containing various amounts of tetra-N-propylammonium iodide at 25°C

Fig. 3c presents the variation in number density of charge carrier (η) as a function of tetra-n-propylammonium iodide (TPAI) concentration in the gel polymer electrolyte (GPE) system. An initial KI content leads to a rise in charge carrier density, attributed to enhanced salt dissociation and the generation of mobile ions as shown by S1 sample. However, beyond the addition of TPAI concentration, a decline in charge carrier density is observed. This reduction is primarily due to ion-pairing and the formation of neutral aggregates, which effectively reduce the number of free charge carriers. Furthermore, the bulky tetra-n-propylammonium cations exhibit lower mobility due to steric hindrance, impeding their movement through the polymer matrix. This limitation not only restricts ionic transport but also contributes to ion aggregation, ultimately diminishing both the charge carrier density and the overall ionic conductivity of the system [12].

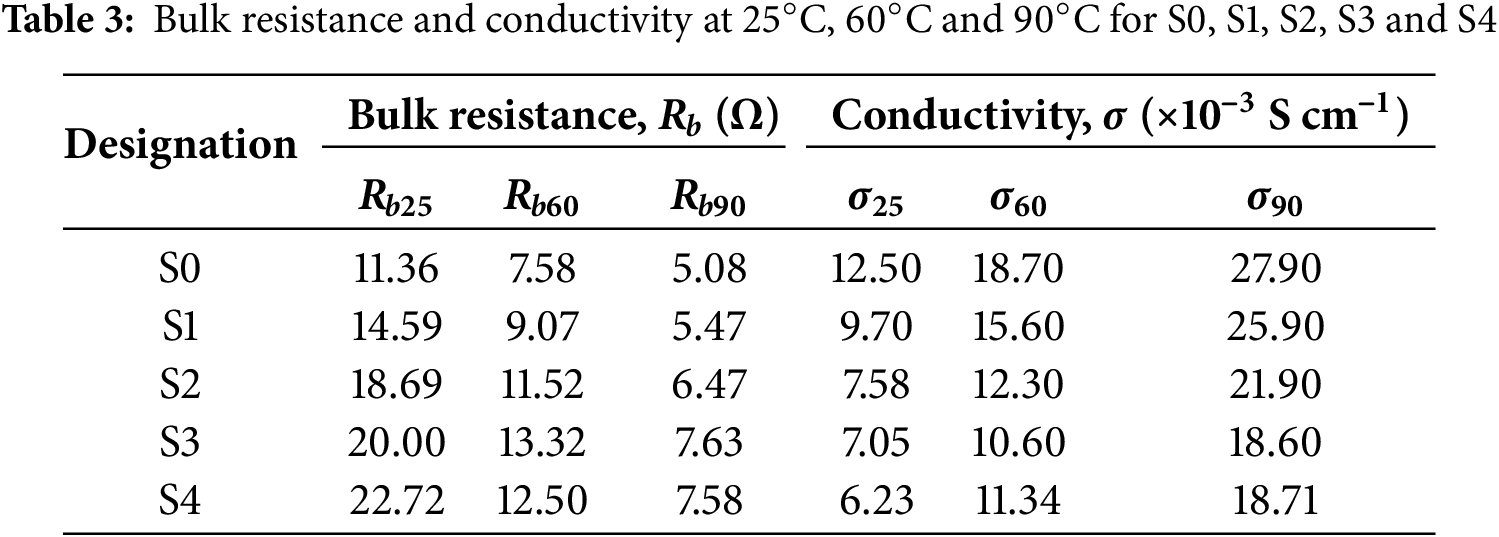

Table 3 presents the bulk resistance (Rb, Ω) and conductivity (σ, S cm−1) values for samples S0, S1, S2, S3, and S4 at three different temperatures: 25°C, 60°C, and 90°C. The data clearly indicate that as the temperature increases, the bulk resistance (Rb) decreases while the ionic conductivity increases. This behavior suggests that higher thermal energy enhances the mobility of charge carriers within the gel polymer electrolyte (GPE). The increase in ionic mobility with temperature is consistent with the thermally activated conduction mechanism, where ions able to overcome potential barriers more easily at elevated temperatures [27]. Consequently, the observed improvement in conductivity at higher temperatures demonstrates that the developed GPE exhibits good thermal stability and able to sustain efficient ionic transport under elevated operating conditions. This characteristic makes the GPEs promising for electrochemical devices, particularly those that are required to function reliably at high temperatures [27].

For comparison, Table 4 presents the ionic conductivity values (σ) reported in earlier and recent studies at room temperature (25°C). Gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) prepared using polymers such as polyacrylonitrile (PAN), polyurethane acrylate (PUA), and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) generally exhibit conductivities in the range of 0.05 to 3.30 × 10−3 S cm−1. In contrast, when polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is employed as the host polymer, significantly higher conductivity values have been achieved, exceeding 6.60 × 10−3 S cm−1. This suggests that PVA possesses considerable potential as a host polymer for developing high-performance gel polymer electrolytes in various electrochemical devices [27].

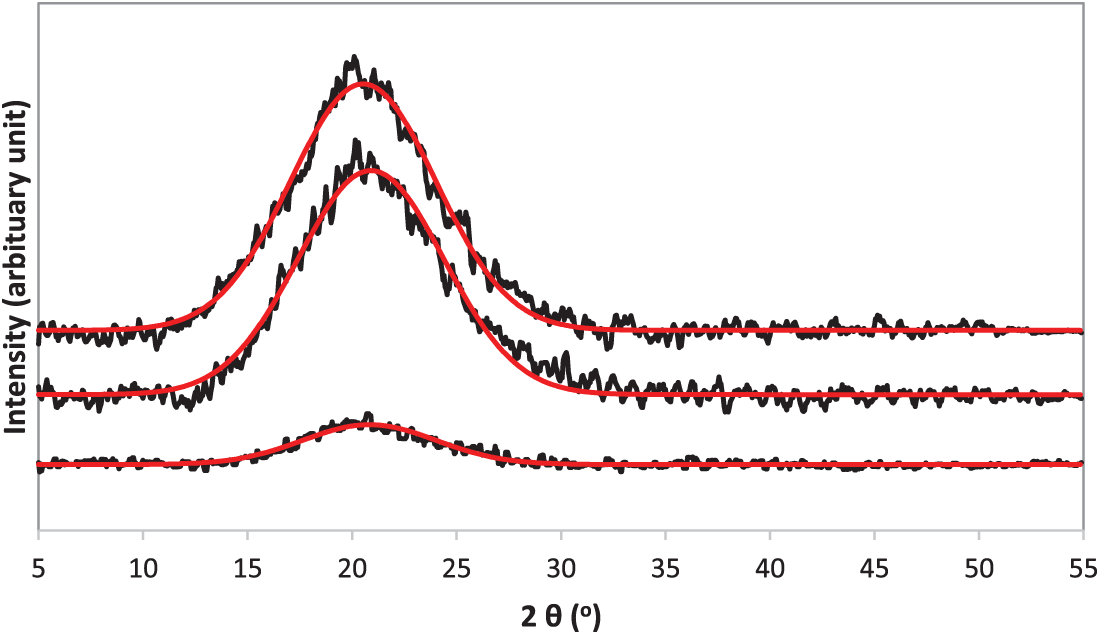

According to Fig. 4, a broad amorphous peak is observed at approximately 2θ ≈ 20°, for the S0 (100 wt.% KI), S1 (30:70 wt.% TPAI-KI) and S4 (100 wt.% TPAI). The experimental XRD patterns are accompanied by red fitting lines, confirming a strong agreement between the measured data and the fitted curves. The presence of this broad halo indicates that the gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) undergo a structural transformation from a semi-crystalline to a predominantly amorphous phase. Such an amorphous arrangement reduces the degree of polymer chain packing and increases the free volume within the electrolyte matrix, thereby creating more flexible pathways for ion migration. This structural modification is directly associated with improved ionic conductivity, as the enhanced segmental motion of polymer chains facilitates faster ion transport [30].

Figure 4: XRD pattern for S0 (100 wt.% KI), S1 (30:70 wt.% TPAI-KI) and S4 (100 wt.% TPAI)

3.3 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis

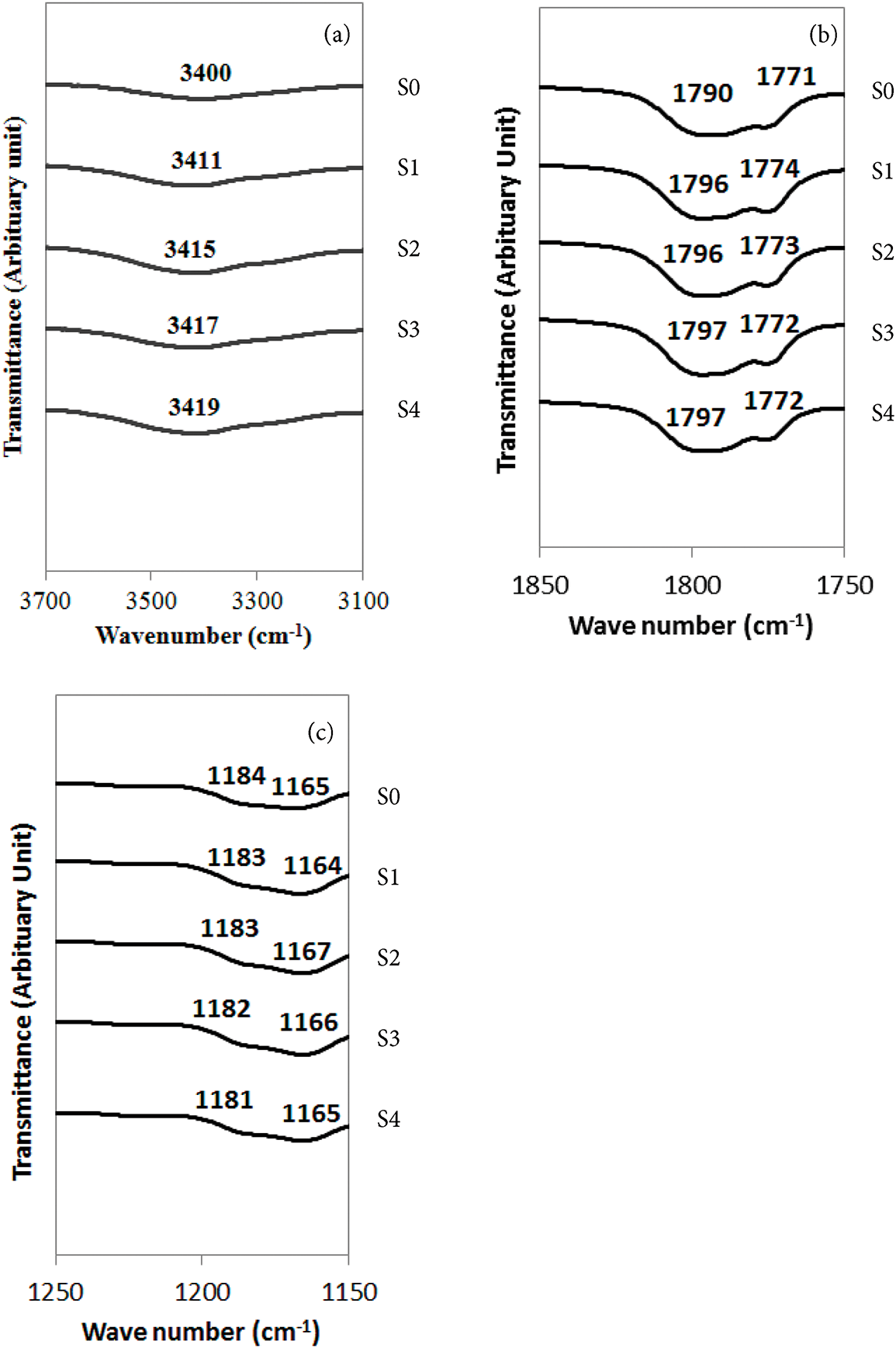

Fig. 5a illustrates the FTIR spectral profiles of PVA-based gel polymer electrolytes containing the various amount of tetra-N-propylammonium iodide-potassium iodide within the wavenumber range of 3700–3100 cm−1. The O–H stretching vibrations were identified at 3400, 3411, 3415, 3417, and 3419 cm−1 for samples S0, S1, S2, S3, and S4, respectively. Accordingly, the noticeable shift in all samples showing the significant interaction of the polyvinyl alcohol with the tetra-N-propylammonium iodide-potassium iodide [11].

Figure 5: FTIR spectra (a) 3100–3700 cm−1 (b) 1850–1750 cm−1 and (c) 1250–1150 cm−1 for GPEs containing various amounts of tetra-N-propylammonium iodide

Further FTIR analysis, depicted in Fig. 5b,c, was conducted in the regions 1850–1750 cm−1 and 1250–1150 cm−1 to evaluate the C=O and C–O–C functional groups, respectively. The characteristic absorption bands are summarized in Table 5. The C=O stretching bands initially present at 1771 and 1790 cm−1 (S0 sample) remained essentially unchanged (S4 sample), indicating that the interaction PVA-based gel polymer electrolytes with tetra-N-propylammonium iodide-potassium iodide primarily affects the ether linkages rather than the carbonyl functionalities. In contrast, upon introduction of the tetra-N-propylammonium iodide-potassium iodide, the C–O–C stretching vibrations observed in the S0 sample (1165 and 1184 cm−1) underwent a discernible shift for the S3 sample (1167 and 1187 cm−1), suggesting chemical interaction [11].

Gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) based on polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), potassium iodide (KI), and tetra-N-propylammonium iodide (TPAI) were successfully synthesized using a solution mixing technique. The systematic variation of TPAI concentration demonstrated a significant impact on the structural dynamics and ion transport behavior of the GPEs. The sample containing 30 wt.% TPAI exhibited the highest ionic conductivity of 9.70 mS cm−1 at 25°C, indicating enhanced ion mobility and favorable dielectric properties. The XRD analysis of the gel polymer electrolytes indicates an amorphous structure, which contributes to enhanced conductivity. FTIR analysis confirmed strong interactions among PVA, TPAI, and KI, contributing to the formation of a well-coordinated ionic environment within the polymer matrix. These findings highlight the potential of TPAI-incorporated PVA-based GPEs for high-performance electrochemical applications.

Acknowledgement: Authors thank Universiti Sains Malaysia, Bridging Grant with Project No.: R501-LR-RND003-0000002095-0000.

Funding Statement: The authors received funding from Universiti Sains Malaysia under the Bridging Grant (Project No: R501-LR-RND003-0000002095-0000) to support this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, M. F. Aziz and A. A. Rahim; methodology, M. F. Aziz; software, M. F. Aziz; validation, M. F. Aziz and A. R. M. Rais; formal analysis, M. F. Aziz; investigation, M. F. Aziz; resources, M. F. Aziz; data curation, M. F. Aziz and A. A. Rahim; writing—original draft preparation, M. F. Aziz; writing—review and editing, M. F. Aziz and A. R. M. Rais; visualization, M. F. Aziz; supervision, M. F. Aziz; project administration, M. F. Aziz; funding acquisition, M. F. Aziz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ram Prasanth S, Prasannavenkadesan V, Katiyar V, Achalkumar AS. Polymer electrolytes: evolution, challenges, and future directions for lithium-ion batteries. RSC Appl Polym. 2025;3(3):499–531. doi:10.1039/d4lp00325j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Raghavan P, Fatima MJ. Polymer electrolytes for energy storage devices. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2021. doi:10.1201/9781003144793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sharma P, Banerjee D. Biopolymers as solid polymer electrolytes: advances, challenges, and future prospects. Prabha Mater Sci Lett. 2025;4(2):128–47. doi:10.33889/pmsl.2025.4.2.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sima FA, Ghafari A, Akbari S. Polymer-based electrolytes for safer and more efficient battery systems. NanoSci Technol J. 2024;15:1–16. [Google Scholar]

5. Zhou X, Zhou Y, Yu L, Qi L, Oh KS, Hu P, et al. Gel polymer electrolytes for rechargeable batteries toward wide-temperature applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2024;53(10):5291–337. doi:10.1039/d3cs00551h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Aruchamy K, Ramasundaram S, Divya S, Chandran M, Yun K, Oh TH. Gel polymer electrolytes: advancing solid-state batteries for high-performance applications. Gels. 2023;9(7):585. doi:10.3390/gels9070585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Liu J, Wang Z, Yang Z, Liu M, Liu H. A protic ionic liquid promoted gel polymer electrolyte for solid-state electrochemical energy storage. Materials. 2024;17(23):5948. doi:10.3390/ma17235948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Cyriac V, Ismayil, Mishra K, Rao A, Khellouf RA, Masti SP, et al. Eco-friendly solid polymer electrolytes doped with NaClO4 for next-generation energy storage devices: structural and electrochemical insights. Mater Adv. 2025;6(10):3149–70. doi:10.1039/d5ma00107b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sadiq M, Raza MMH, Chaurasia SK, Zulfequar M, Ali J. Studies on flexible and highly stretchable sodium ion conducting blend polymer electrolytes with enhanced structural, thermal, optical, and electrochemical properties. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2021;32(14):19390–411. doi:10.1007/s10854-021-06456-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Aziz MFA, Safie NE, Azam MA, Adaham TAIT, Yu TJ, Takasaki A. A comprehensive review of filler, plasticizer, and ionic liquid as an additive in GPE for DSSCs. AIMS Energy. 2022;10(6):1122–45. doi:10.3934/energy.2022053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Aziz MF, Rahim AA, Razak ESA, Jaaffar SNA, Buraidah MH, Shukur MF. Enhanced ion transport and structural dynamics in gel polymer electrolytes containing a plasticizer prospect for DSSC application. Ionics. 2025;31(6):6103–15. doi:10.1007/s11581-025-06270-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chowdhury FI, Islam J, Arof AK, Khandaker MU, Zabed HM, Khalil I, et al. Electrocatalytic and structural properties and computational calculation of PAN-EC-PC-TPAI-I2 gel polymer electrolytes for dye sensitized solar cell application. RSC Adv. 2021;11(37):22937–50. doi:10.1039/d1ra01983j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Bandara TMWJ, Karunathilaka DGN, Ratnasekera JL, Ajith De Silva L, Herath AC, Mellander BE. Electrical and complex dielectric behaviour of composite polymer electrolyte based on PEO, alumina and tetrapropylammonium iodide. Ionics. 2017;23(7):1711–9. doi:10.1007/s11581-017-2016-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Gao Y, Mo Y, Qi S, Li M, Ma T, Du L. Enhancing ion transport in polymer electrolytes by regulating solvation structure via hydrogen bond networks. Molecules. 2025;30(11):2474. doi:10.3390/molecules30112474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Alipoori S, Mazinani S, Aboutalebi SH, Sharif F. Review of PVA-based gel polymer electrolytes in flexible solid-state supercapacitors: opportunities and challenges. J Energy Storage. 2020;27(1):101072. doi:10.1016/j.est.2019.101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Teo LP, Buraidah MH, Arof AK. Polyacrylonitrile-based gel polymer electrolytes for dye-sensitized solar cells: a review. Ionics. 2020;26(9):4215–38. doi:10.1007/s11581-020-03655-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xu T, Li J, Gong R, Xi Z, Huang T, Chen L, et al. Environmental effects on the ionic conductivity of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)-based quasi-solid-state electrolyte. Ionics. 2018;24(9):2621–9. doi:10.1007/s11581-017-2397-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gurusamy R, Lakshmanan A, Srinivasan N, Ramani A, Renganathan RT, Venkatachalam S. PVDF/PEO/HNT-based hybrid polymer gel electrolyte (HPGE) membrane for energy applications. Ionics. 2022;28(8):3777–86. doi:10.1007/s11581-022-04602-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang Y, Zhu C, Bai S, Mao J, Cheng F. Recent advances and future perspectives of PVDF-based composite polymer electrolytes for lithium metal batteries: a review. Energy Fuels. 2023;37(10):7014–41. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.3c00678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kadhum M, Jawad MK, Alsammarraie AMA. Investigate the conductivity and dielectric properties of polymer electrolytes address for correspondence. Indian J Nat Sci. 2018;9(50):14891–9. [Google Scholar]

21. Yamada Pittini Y, Daneshvari D, Pittini R, Vaucher S, Rohr L, Leparoux S, et al. Cole–Cole plot analysis of dielectric behavior of monoalkyl ethers of polyethylene glycol (CnEm). Eur Polym J. 2008;44(4):1191–9. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2008.01.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mazuki NF, Rasali NMJ, Saadiah MA, Samsudin AS. Irregularities trend in electrical conductivity of CMC/PVA-NH4Cl based solid biopolymer electrolytes. AIP Conf Proc. 2018;2030(1):020221. doi:10.1063/1.5066862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dissanayake MAKL, Jayathissa R, Seneviratne VA, Thotawatthage CA, Senadeera GKR, Mellander BE. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) based quasi-solid electrolyte with binary iodide salt for efficiency enhancement in TiO2 based dye sensitized solar cells. Solid State Ion. 2014;265(3):85–91. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2014.07.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hosseini S, Ghahramani M, Bakhshi H. The effect of ZrO2-g-poly(methyl acrylate-co-maleic anhydride) on the performance of polyacrylonitrile gel polymer electrolyte in lithium ion batteries. J Mater Chem A. 2025;13(16):11486–504. doi:10.1039/d4ta08951k. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Noor IM, Rojudi ZE, Ghazali MIM, Tamchek N, Nagao Y. Novel polymer electrolyte based polyurethane acrylate for low-cost perovskite solar cells applications. Mol Cryst Liq Cryst. 2023;761(1):7–21. doi:10.1080/15421406.2023.2173770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mazuki NF, Kufian MZ, Nagao Y, Samsudin AS. Correlation studies between structural and ionic transport properties of lithium-ion hybrid gel polymer electrolytes based PMMA-PLA. J Polym Environ. 2022;30(5):1864–79. doi:10.1007/s10924-021-02317-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Aziz MF, Noor IM, Sahraoui B, Arof AK. Dye-sensitized solar cells with PVA–KI–EC–PC gel electrolytes. Opt Quantum Electron. 2014;46(1):133–41. doi:10.1007/s11082-013-9722-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Jawad MK, Majid SR, Al-Ajaj EA, Suhail MH. Preparation and characterization of poly (1-vinylpyrrolidone-co-vinyl acetate)/PMMA polymer electrolyte based on TPAI and KI. Adv Phys Theor Appl. 2014;29:14–22. [Google Scholar]

29. Bakar R, Darvishi S, Aydemir U, Yahsi U, Tav C, Menceloglu YZ, et al. Decoding polymer architecture effect on ion clustering, chain dynamics, and ionic conductivity in polymer electrolytes. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2023;6(7):4053–64. doi:10.1021/acsaem.3c00310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Aziz MF, Azam MA, Buraidah MH, Arof AK. Effect of the potassium iodide in tetrapropyl ammonium iodide-polyvinyl alcohol based gel polymer electrolyte for dye-sensitized solar cells. Optik. 2021;247(6346):167978. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.167978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools