Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Synthesis of Hyperbranched Polyethyleneimine-Propylene Oxide-N-isopropylacrylamide (HPEI-co-PO-co-NIPAM) Terpolymer as a Shale Inhibitor

Oilfield Chemistry Department, China Oilfield Services Limited, Langfang, 065201, China

* Corresponding Author: Liquan Zhang. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 1159-1179. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.072450

Received 27 August 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

Addressing the persistent challenge of shale hydration and swelling in water-based drilling fluids (WBDFs), this study developed a smart thermo-responsive shale inhibitor, Hyperbranched Polyethyleneimine-Propylene Oxide-N-isopropylacrylamide (HPN). It was synthesized by grafting hyperbranched polyethyleneimine (HPEI) with propylene oxide (PO) and N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM), creating a synergistic hydration barrier through hydrophobic association and temperature-triggered pore plugging. Structural characterization by Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy and gel permeation chromatography (GPC) confirmed the successful formation of the HPN terpolymer, revealing a unique “cationic–nonionic” amphiphilic architecture with temperature-responsive properties. Performance evaluation demonstrated that HPN significantly outperforms conventional inhibitors, including potassium chloride (KCl), cationic polyacrylamide (C-PAM), polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyetheramine (PEA), and HPEI. It achieved a superior performance profile: a low yield point of 14.6 Pa, a maximum linear expansion of only 3.1 mm, and a high shale recovery rate of 62.8% at 20% bentonite content. The inhibition mechanism is attributed to a powerful synergy of electrostatic adsorption, hydrophobic association, and thermally induced aggregation, which provides robust performance under demanding conditions such as high salinity (200,000 mg/L NaCl) and high temperature (120°C). Thermogravimetric analysis confirmed excellent thermal stability, and the inhibitor exhibited low biological toxicity, complying with stringent environmental standards. These results establish HPN as an efficient, eco-friendly, and field-ready shale inhibitor well-suited for challenging drilling operations.Keywords

The safe and efficient extraction of oil and gas resources depends significantly on continuous innovation in drilling technology. Among key components, drilling fluid is often regarded as the “blood” of drilling operations, with its performance being crucial to overall success. WBDFs, in particular, are widely employed in oil and gas drilling due to their cost-effectiveness, environmental compatibility, and superior rheological properties [1–4]. However, when using water-based drilling fluids to handle highly reactive shale formations, the clay minerals in the formation are prone to hydration, swelling, and dispersion. This can lead to wellbore instability, collapse of shale layers, or even complete well abandonment. Such wellbore instability issues not only severely compromise drilling efficiency but also drive up exploration and development costs [5–7]. To effectively suppress the dispersion and swelling of clay, two methods can be employed: one involves intercalating inhibitors into the interlayer structure of clay minerals, and the other consists of coating the shale formation with high-molecular-weight polymers, thereby blocking the interaction between water and reactive shale [5]. Potassium chloride, as one of the earliest discovered shale inhibitors, is typically used at concentrations ranging from 2% to 20%. However, water-based drilling fluids containing more than 1 wt% of KCl significantly inhibit microbial activity and have failed standard mussel-shrimp bioassays. As a result, potassium-ion-enriched water-based drilling fluids are deemed unsuitable for deep-sea oil and gas drilling operations due to their toxicity toward marine organisms and failure to meet environmental requirements [8].

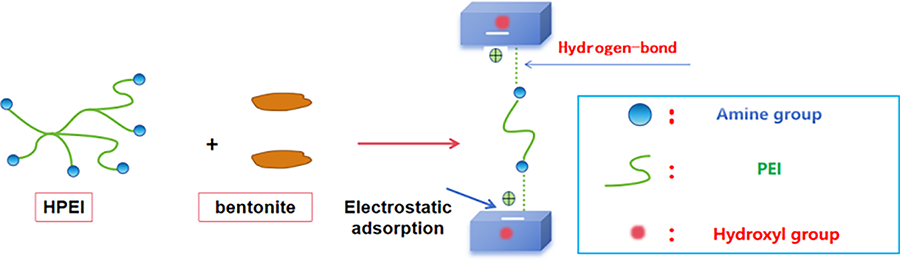

Extensive research efforts in recent years have led to the development of a comprehensive range of shale inhibitors. These compounds are generally classified as ionic polymers, non-ionic polymers, low-molecular-weight amines, ionic liquids, nanomaterials, or surfactants [9–13]. As a novel additive, hyperbranched polymers have been successfully incorporated into water-based drilling fluid systems to inhibit the hydration and swelling of shale. Compared to other linear amine-based inhibitors, hyperbranched amine-terminated polymers possess a quasi-spherical structure with terminal amine groups directly attached to their branching ends. This unique molecular configuration dictates both the chemical characteristics and inhibitory efficacy of hyperbranched polymers. Their adsorption mechanism stems from the highly branched architecture, terminated with amine groups, which enables strong attachment to clay surfaces and effectively suppresses shale hydration and expansion [14–17]. Yang et al. [18] reported that hyperbranched polyglycerols or hyperbranched polymers derived from ethylene carbonate exhibit remarkable structural properties and are considered superior shale inhibitors. Experimental studies have demonstrated that these hyperbranched structures offer better inhibition performance compared to their linear polyglycol counterparts. By enhancing the hydrophobicity of the hyperbranched polyglycol architecture, it is possible to inhibit reactive shale formations. Hyperbranched polyethyleneimine has been widely applied in sensors [19,20], membranes [21,22], and catalysts [23] due to its excellent environmental friendliness and adsorption properties [24–26]. Fig. 1 clearly illustrates its inhibition mechanism: polyethyleneimine (PEI) molecules intercalate into the interlayer spaces and replace cations, thereby promoting the migration of water molecules into the interlayer gaps through electrostatic repulsion. Simultaneously, the amino groups of PEI form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups on the clay surface, enabling the adsorption of PEI onto the clay. These electrostatic interactions collectively constitute the inhibition mechanism of PEI. However, despite possessing a large number of amine groups and strong adsorption capacity, HPEI suffers from drawbacks such as poor salt tolerance, incompatibility with anionic additives in drilling fluids, and poor thermal stability at high temperatures. These limitations severely restrict its application under complex oil and gas conditions.

Figure 1: The schematic mechanism for the inhibition of PEI with bentonite

This study developed an HPEI-based ternary copolymer called HPEI-PO-NIPAM using a molecular design approach. A performance comparison was made among six shale inhibitors: KCl, C-PAM, PEG, PEA, HPEI, and HPEI-PO-NIPAM. The advantages and innovations of HPEI-PO-NIPAM lie in its smartly designed “cationic–nonionic” amphiphilic structure, achieved by adding PO segments and NIPAM units. This design not only preserves the strong adsorption ability of HPEI but also significantly enhances the polymer’s hydrophobic adsorption on clay surfaces by incorporating numerous hydrophobic and amide groups. As a result, the product overcomes reliance on electrostatic adsorption alone and demonstrates exceptional salt tolerance. Additionally, including NIPAM units gives the polymer a distinctive temperature-responsive hydration property. In shale fractures, the copolymer can strengthen hydrophobic association in response to temperature changes, leading to improved plugging performance. Furthermore, the molecular design reduces the cationic density, greatly increasing compatibility with anionic treatment agents and making the product more environmentally friendly. Therefore, HPEI-PO-NIPAM is not just a simple mixture but a fully engineered product created through molecular design. It effectively addresses the main limitations of pure HPEI and represents a significant innovation in developing high-efficiency, salt-tolerant, and environmentally friendly shale inhibitors.

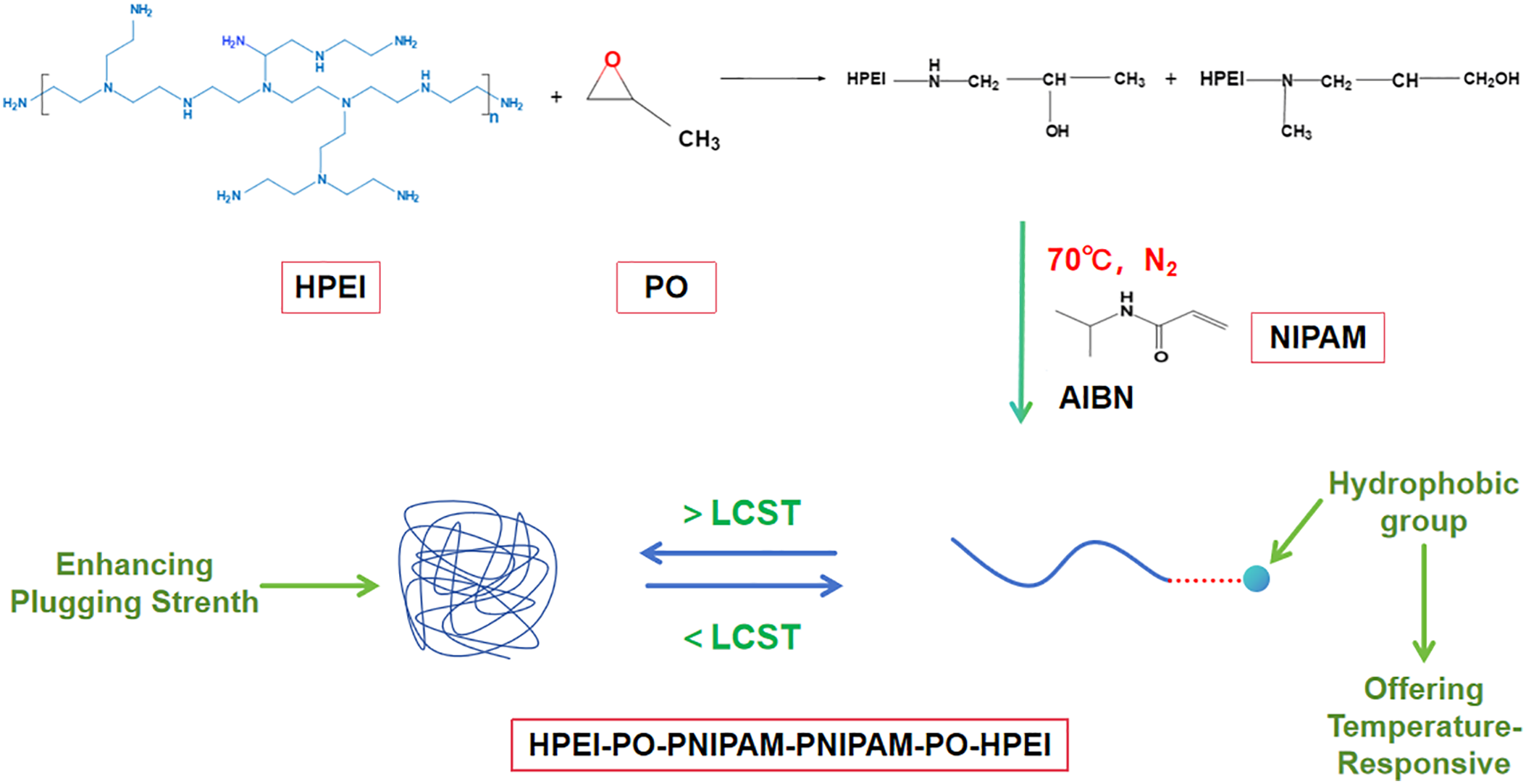

The experimental reagents and instruments used in this work are listed in Tables 1–3.

2.2 Synthesis of the Shale Inhibitor

2.2.1 Synthesis of the HPEI-PO

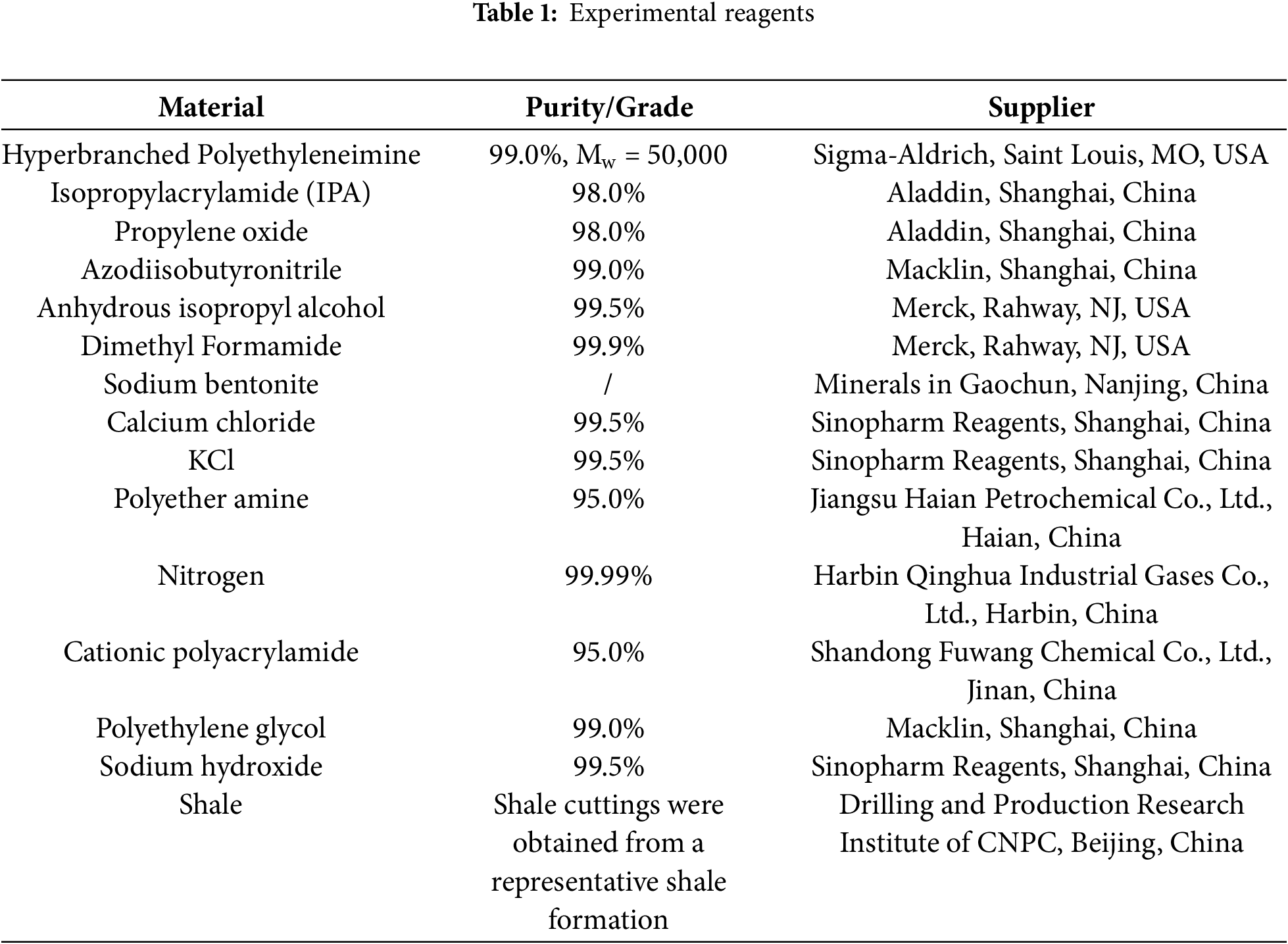

A quantity of 10.00 g of vacuum-dried HPEI was dissolved in 150 mL of IPA. The solution was stirred under a continuous N2 atmosphere for 20 min to thoroughly remove oxygen and moisture. Subsequently, the oil bath temperature was raised to 60°C and allowed to equilibrate. Then, PO was added dropwise to the vigorously stirred HPEI-IPA solution over 30 min to prevent localized overheating and violent reflux. After the addition was complete, the reaction mixture was stirred under reflux at 60°C under N2 for 6 h. Once the reaction was finished, the mixture was rapidly cooled in an ice-water bath to room temperature to quench the reaction. The crude product was first subjected to rotary evaporation (60°C water bath) to remove most of the isopropanol solvent, yielding a viscous liquid. This liquid was dissolved in a small amount of deionized water and transferred into a dialysis bag. Dialysis was carried out for 48 h with regular changes of the external dialysate to remove unreacted PO, byproducts, and salts completely. The purified product was obtained as a white solid, designated as HPEI-PO, which was stored sealed at 4°C for future use. The molecular structure of HPEI is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Structure of HPEI

2.2.2 Synthesis of P (HPEI-NIPAM)

The process of synthesizing HPEI-NIPAM was performed through a typical Michael addition reaction. Under a nitrogen atmosphere, 5.00 g of HPEI was dissolved in 50 mL of anhydrous methanol. While continuously stirring, 7.85 g of NIPAM monomer (at a molar feed ratio of 1:1 relative to the primary and secondary amine groups in HPEI) was slowly added to the solution. The mixture was then heated to 65°C and kept under reflux with stirring for 48 h. After the reaction finished, the mixture was cooled to room temperature, and most of the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. The crude product was dissolved in deionized water and purified by dialysis against deionized water using a dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cut-off of 3500 Da for 72 h. Finally, the dialyzed solution was freeze-dried to obtain approximately 7.2 g of HPEI-NIPAM as a white, flaky solid, with an 85% yield.

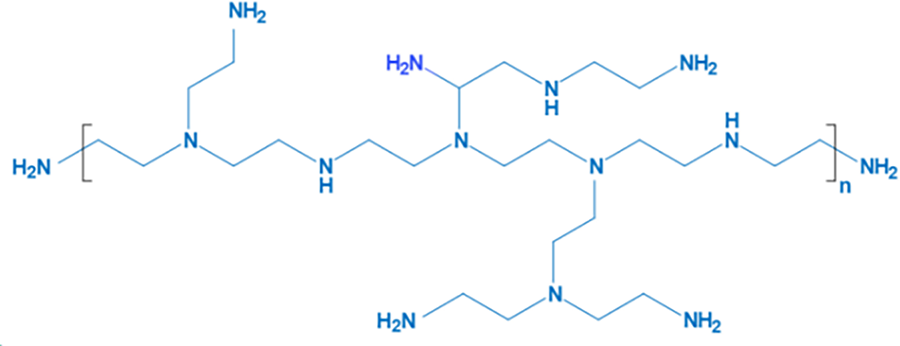

2.2.3 Synthesis of HPEI-PO-NIPAM

A quantity of 5.00 g of the synthesized HPEI-PO intermediate was dissolved in 50 mL of anhydrous isopropanol in a three-necked flask. To this solution, 22.6 g of NIPAM and 0.10 g of the initiator AIBN were added, corresponding to a NIPAM/HPEI-PO molar ratio of 20:1. The reaction was conducted at 70°C for 12 h under a N2 atmosphere with continuous stirring. The crude product was concentrated by rotary evaporation to remove IPA, then redissolved in deionized water and transferred into a dialysis bag (MWCO: 3500 Da). Purification was performed against deionized water for 72 h, with water changes every 12 h, to remove unreacted monomers and salts. The final product, a white solid identified as the HPEI-PO-NIPAM ternary copolymer (denoted as HPN), was obtained after freeze-drying. The typical yield for this step was 85–90%. The synthetic route of HPN is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Synthetic route of HPN

2.2.4 Optimization of Synthetic Formulation

The synthesis of HPN involved two key steps: the propoxylation of HPEI and the subsequent grafting of NIPAM chains. To determine the optimal formulation, both the molar ratio of PO to HPEI and the molar ratio of NIPAM to the resulting HPEI-PO intermediate were systematically optimized. First, a series of HPEI-PO intermediates was synthesized with varying PO/HPEI molar ratios (5:1, 10:1, 15:1, 20:1, and 30:1). Their performance as shale inhibitors was preliminarily evaluated via hot-rolling recovery tests at 120°C. Subsequently, using the optimally performing HPEI-PO intermediate, a second series of HPN terpolymers was synthesized with varying NIPAM/HPEI-PO molar ratios (5:1, 10:1, 15:1, 20:1, and 30:1). These final products were comprehensively evaluated based on their shale inhibition efficiency, temperature response, and salt tolerance to identify the overall best performer.

Molecular structures of the polymers were characterized using a Frontier FTIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer). Samples were prepared by grinding with potassium bromide (KBr) to form pellets. Spectra were acquired across the wavenumber range of 400 cm−1–4000 cm−1.

2.3.2 Molecular Weight Determination and Grafting Ratio Analysis

Molecular weight of HPN was measured by GPC Agilent 1260 Infinity Separations Module, USA at 25°C using DMF as solvent and calibrated with polystyrene standards. The grafting extent (GE) of NIPAM was calculated based on the increase in number-average molecular weight (Mn) from the HPEI-PO intermediate to the HPN terpolymer, according to the following equation:

where Mn, NIPAM is the molecular weight of the NIPAM repeating unit (113 g/mol).

2.4 Temperature-Responsive Test

The thermosensitive behavior of the polymer was characterized by measuring the transmittance of its aqueous solution at various temperatures. The polymer was dissolved in deionized water to prepare a solution with a concentration of 1 mg/mL. Using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature controller, the transmittance was monitored at a wavelength of 500 nm as the temperature varied. Heating and cooling cycles were conducted at a rate of 0.5°C/min to investigate the lower critical solution temperature (LCST) and its reversibility. The LCST was defined as the temperature at which transmittance reached 50%. With a UV-Vis spectrophotometer fitted with a constant temperature colorimetric tube holder, the change in transmittance at 500 nm was measured to assess the polymer’s temperature responsiveness. The polymer solution (1 mg/mL) was heated from 20°C to 50°C at a rate of 1°C/min. Transmittance was recorded at 0.5°C intervals. The turbidity point (Tcp) was defined as the temperature at which 90% of the transmittance was lost.

2.5 Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermal stability was assessed using a TGA-601S thermogravimetric analyzer. An Al2O3 crucible was zero-calibrated in the sample chamber. Precisely 0.4 g of the sample was weighed into the crucible, which was then returned to the chamber. The TGA program heated samples at 10°C/min under N2 atmosphere to a final temperature of 650°C. Thermograms of HPN were recorded and analyzed.

2.6 Evaluation of Inhibitory Performance

2.6.1 Clay Slurry-Making Experiment

Initially, five samples of a 1% HPN solution were prepared, and their pH was adjusted to 8 using 1 M NaOH. Then, bentonite was added to each sample while stirring at high speed to create slurries with bentonite concentrations of 4%, 8%, 12%, 16%, and 20% by weight. After stirring for 20 min at 10,000 rpm, the yield point of each slurry was measured and calculated using a six-speed rotational viscometer. A graph showing the yield point as a function of bentonite content was then created.

A linear swelling test is used to measure the expansion of shale cuttings soaked in a water-based drilling fluid. The swelling heights of Na-MMT in water and solutions with a concentration of 0.5% shale inhibitor (KCl, C-PAM, PEG, PEA, HPEI, and HPN) were determined with an M4600 high-temperature and high-pressure linear expansion instrument (Grace Instrument, Houston, TX, USA). A higher linear swelling rate indicates a high potential for hydration. The testing method is as follows: Five grams of bentonite were compacted at 10 MPa for 5 min. After taking it out, please place it in the sample slot of the expansion meter. Add the inhibitor solution (adjust the pH to 8) to the sample chamber, reset it to zero immediately, and start measuring the change in the expansion height of bentonite over time.

2.6.3 Rolling Recovery Rate Measurement

Twenty-five grams of mud shale cuttings (1.6–3.25 mm) were placed into an aging container. Add an inhibitor solution (pH adjusted to 8) to the container. Then, put the container in a roller oven and heat it at 120°C for 16 h. Afterwards, allow the system to cool, then decant the liquid. Dry the remaining cuttings at 105°C until constant weight is reached, and sieve them through a No. 30 sieve. The hot-rolling recovery rate is calculated as the percentage of the cuttings retained on the sieve relative to the initial weight of the cuttings.

2.6.4 High-Temperature High-Pressure (HTHP) Fluid Loss Test

Different concentrations of HPN were added to the WBDFs and stirred at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The WBDFs were hot-rolled at 120°C, 150°C, 180°C, and 210°C for 16 h. After aging, the HTHP filtration loss was determined using an HTHP filtration tester at the respective aging temperatures and under a pressure of 3.5 MPa.

Particle size distributions of HPN suspensions were determined by using a BeNano 90 (Dandong Bettersize Instruments, Dandong, China) nanoparticle size and zeta potential analyzer with a detection range of 0.3 nm to 10 μm. To prevent particle aggregation during measurements, samples were subjected to ultrasonic agitation at a fixed frequency of 1500 Hz and repeated three times to get the average value. All tests were conducted under conditions of pH = 8 (adjusted with 1 M NaOH) and inhibitor concentration of 1%.

2.7.2 Zeta Potential Measurements

The effect of temperature on the zeta potential value of bentonite solutions with different inhibitors was studied by BeNano 90 nanoparticle size and Zeta potential analyzer, and repeated three times to get the average value. All tests were conducted under conditions of pH = 8 (adjusted with 1 M NaOH) and inhibitor concentration of 1%.

The impact of WBDF on the environment was evaluated through biological toxicity tests, and the 50% lethal concentration was determined using the fluorescent bacteria method [27].

3.1 Optimization of Synthetic Formulation

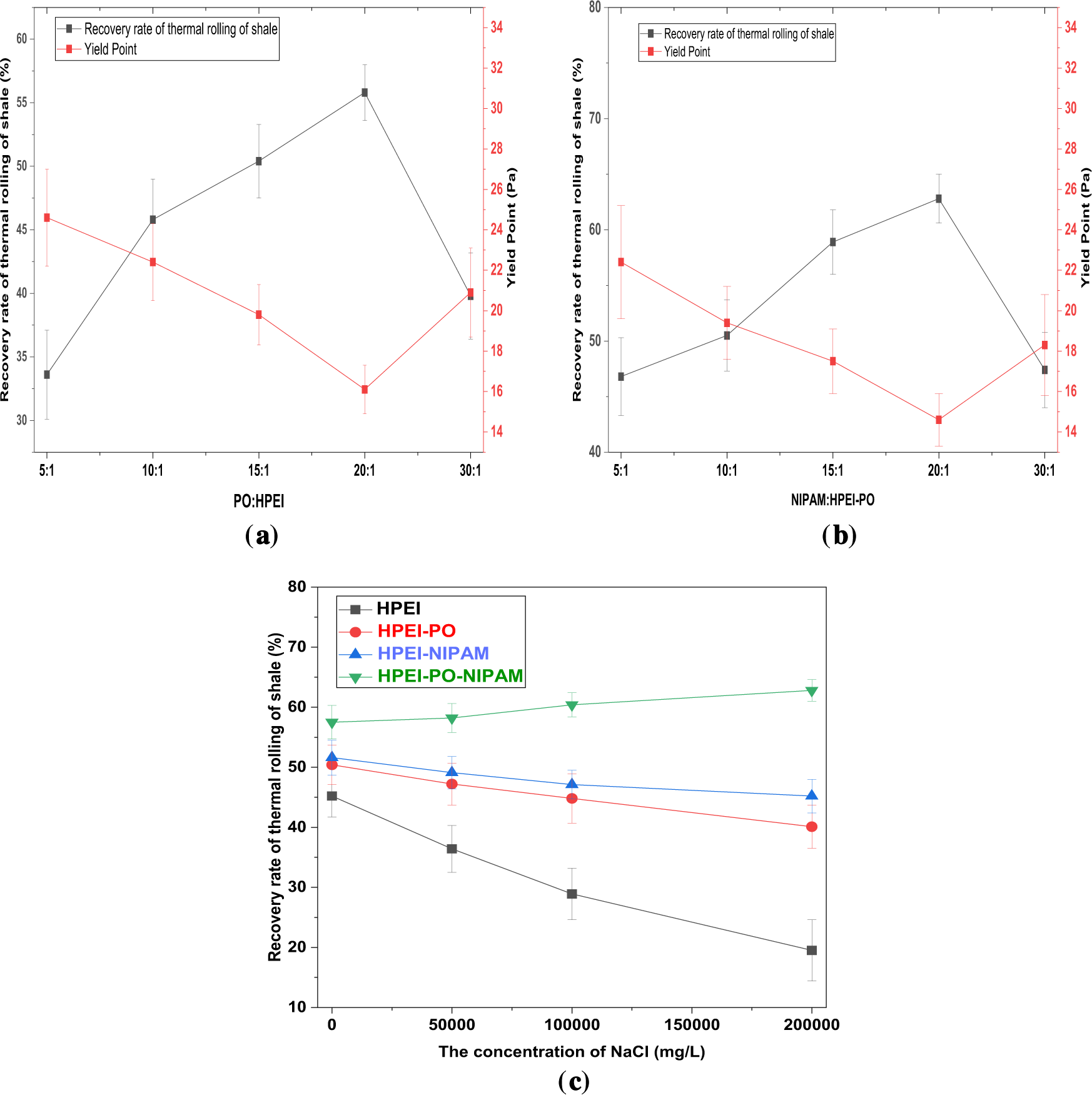

Based on a systematic investigation of the impact of different PO/HPEI molar ratios (5:1, 10:1, 15:1, 20:1, 30:1) on the shale inhibition performance of the HPEI-PO intermediate, it was observed that the hot-rolling recovery rate initially increased and then decreased with increasing PO ratio (Fig. 4a). At a PO/HPEI ratio of 10:1, the recovery rate reached its maximum, indicating that the introduction of PO chains at this ratio effectively enhanced the hydrophobic association capability of the polymer and promoted its adsorption on the clay surface. However, when the ratio was further increased to 20:1, the recovery rate slightly declined. This reduction may be attributed to excessive hydrophobization, which compromised the aqueous solubility and dispersibility of the inhibitor, thereby weakening its inhibitory efficacy.

Figure 4: (a) The effect of the PO/HPEI ratio on the hot rolling recovery rate of bentonite shale and the yield point. (b) The effect of the PO-HPEI/NIPAM ratio on the hot rolling recovery rate of bentonite shale and the yield point. (c) The effect of the PO-HPEI/NIPAM ratio on the hot rolling recovery rate of bentonite shale (Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3))

Building on these findings, the intermediate with a PO/HPEI ratio of 10:1 was selected for subsequent grafting with NIPAM. Further experiments examined the influence of different NIPAM/HPEI-PO molar ratios (5:1, 10:1, 15:1, 20:1, 30:1) on the performance of the final HPN product (Fig. 4b). The results demonstrated that a NIPAM/HPEI-PO ratio of 20:1 yielded the highest shale recovery rate of 62.8%, significantly outperforming other ratios. Lower grafting ratios (e.g., 5:1) provided insufficient thermosensitive units for effective high-temperature plugging, while higher ratios (e.g., 30:1) likely caused steric crowding of segments, hindering the interaction between the HPEI cationic backbone and the clay surface.

Additionally, Fig. 4c clearly shows the shale inhibition performance and salt tolerance of various functionalized polymers. Among them, the final terpolymer, HPEI-PO-NIPAM, exhibits the most remarkable performance. Its recovery rate is not only significantly higher than that of the other samples but also increases further as salt concentration rises to 200,000 mg/L, demonstrating a notable “salt-activated” enhancement effect. In contrast, unmodified HPEI, which depends solely on cationic electrostatic adsorption, suffers severe performance decline in high-salinity environments due to charge shielding. Samples grafted only with PO or NIPAM show some improvements in basic performance or temperature-sensitive properties, but their salt tolerance and synergistic effects are far below those of the terpolymer. This confirms that the hydrophobic adsorption from PO segments and the temperature-responsive behavior from NIPAM create a strong synergy in high-salinity environments. This allows HPN to convert harsh downhole conditions into a driving force for better plugging and inhibition, establishing it as an efficient, intelligent shale inhibitor suitable for challenging high-salinity drilling conditions. Therefore, the results indicate that the optimal synthesis ratios were PO/HPEI = 20:1 and NIPAM/HPEI-PO = 20:1. Under these conditions, the synthesized HPN exhibited excellent shale inhibition in subsequent comprehensive tests and was used for all detailed characterizations and mechanistic studies.

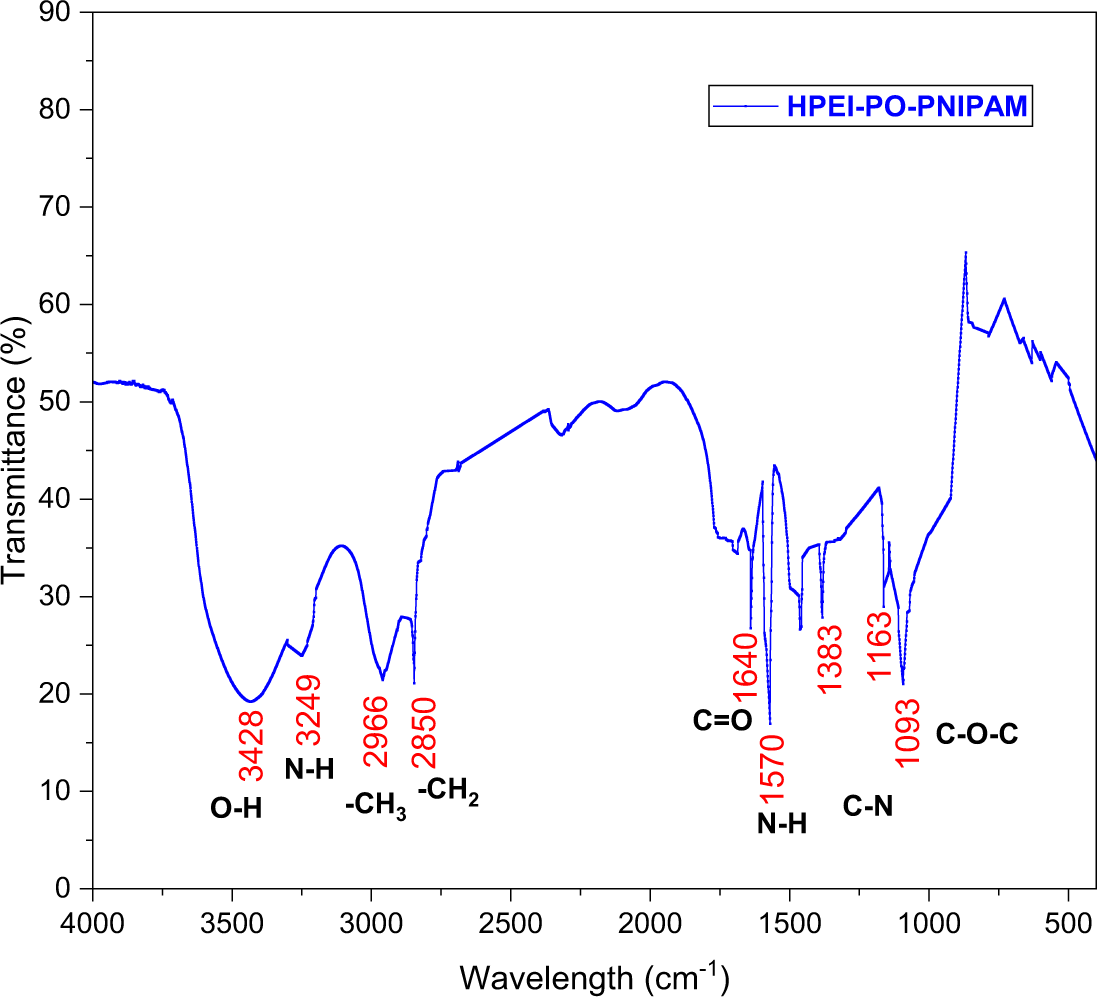

The successful synthesis of the HPN terpolymer was confirmed by FTIR spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. 5. The spectrum displays a broad absorption band between 3400 and 3700 cm−1, attributed to overlapping O–H stretching vibrations from the grafted PO chains and residual N–H stretches from the HPEI backbone. Strong evidence for NIPAM incorporation is indicated by a prominent peak near 1640 cm−1, characteristic of the amide I band (C=O stretch). Additionally, the amide II band (N–H bond) appears around 1570 cm−1. The effective grafting of PO is further confirmed by increased C-H stretching vibrations at 2850 cm−1 and 2966 cm−1, corresponding to methylene (–CH2–) and methyl (–CH3) groups, respectively, along with a distinct N–H stretch and C–O–C ether stretching vibrations at 1163 cm−1 and 1093 cm−1. This conclusively demonstrates the formation of the HPN terpolymer, consistent with the intended molecular structure.

Figure 5: FTIR spectrum of HPN

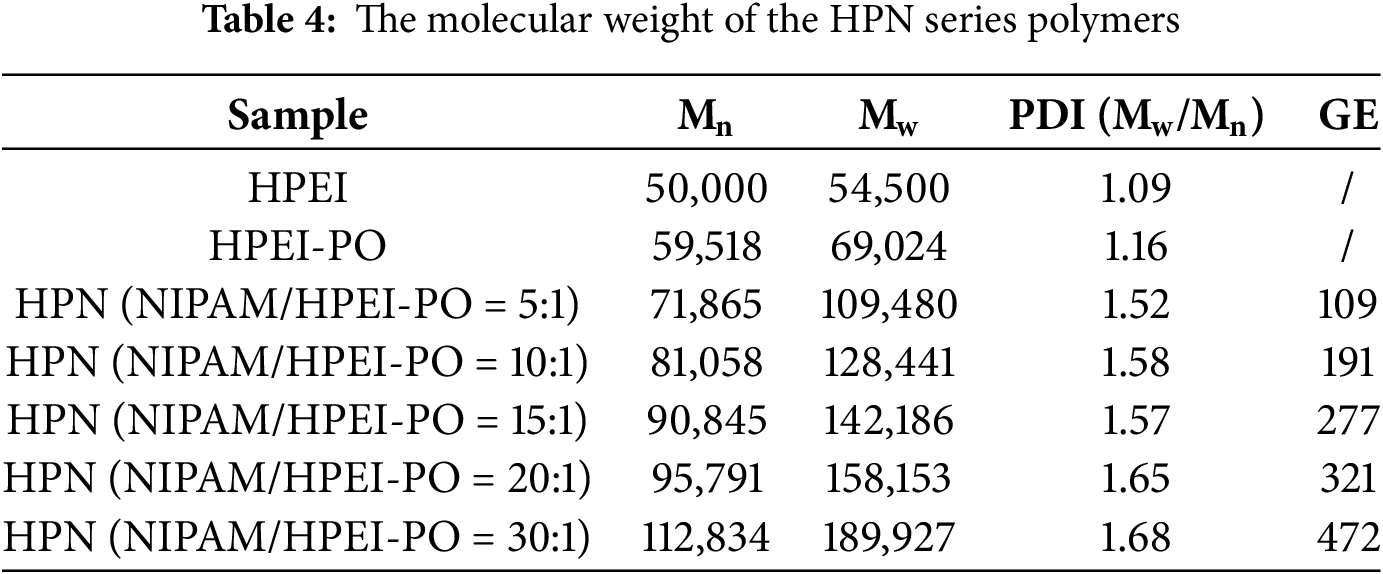

3.2.2 Molecular Weight Determination and Grafting Analysis

GPC results (Table 4) provide quantitative evidence for the successful stepwise synthesis of the HPN terpolymer. The systematic increase in number-average molecular weight (Mn) from 50,000 g/mol (HPEI) to 59,518 g/mol (HPEI-PO) confirms the formation of the intermediate. A subsequent and substantial rise in Mn from 71,865 g/mol to 112,834 g/mol with increasing NIPAM/HPEI-PO feed ratio (from 5:1 to 30:1) unambiguously demonstrates the successful grafting of NIPAM. The calculated GE significantly exceeds 100%, ranging from 109% to 472%. This clearly indicates the formation of multiple PNIPAM chains, each comprising numerous NIPAM units, grafted onto each HPEI-PO backbone, which is characteristic of a graft copolymerization process rather than single monomer attachment. Furthermore, the moderate polydispersity indices (PDI = 1.52–1.68) for all HPN samples are within the typical range for graft copolymers and rule out extensive cross-linking, which would typically result in a PDI > 2.5. In conclusion, the GPC data, through the demonstration of controlled molecular weight increase and distribution, offer compelling structural evidence for the successful synthesis of the HPEI-PO-NIPAM terpolymer.

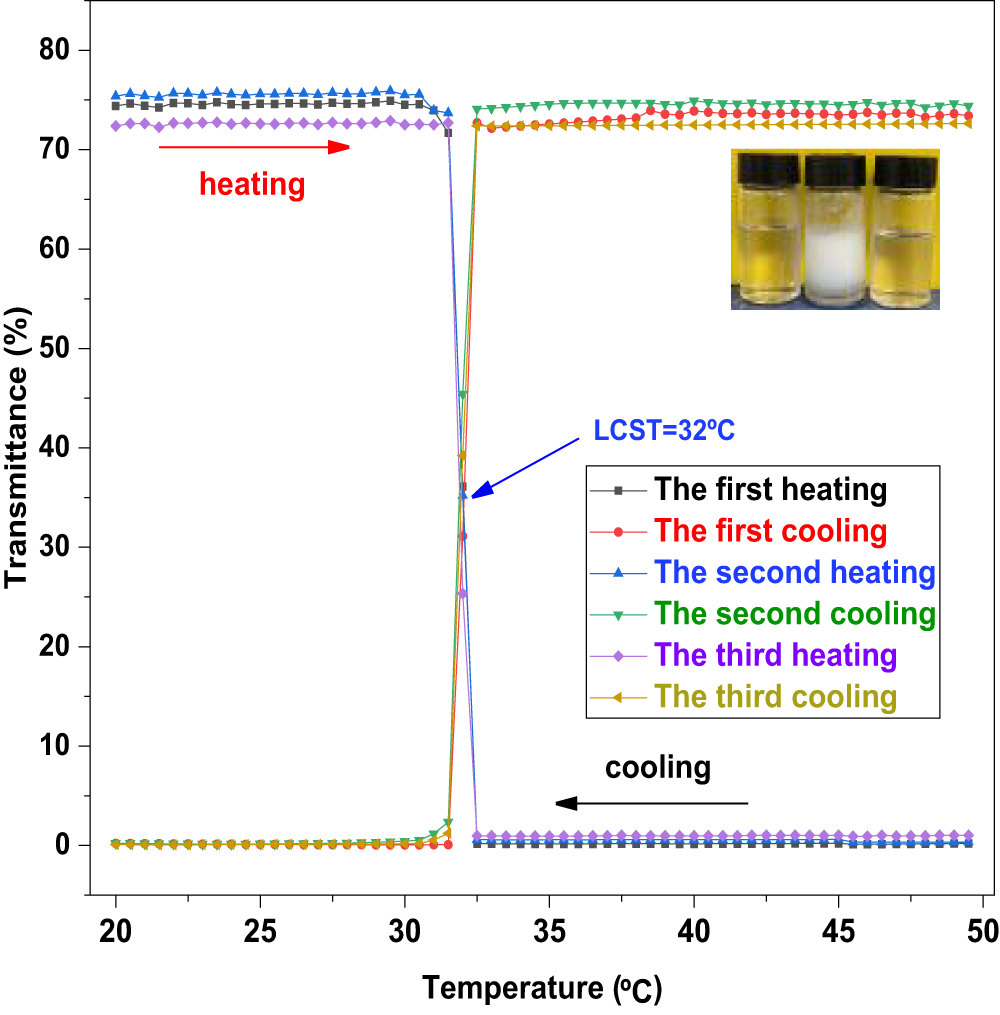

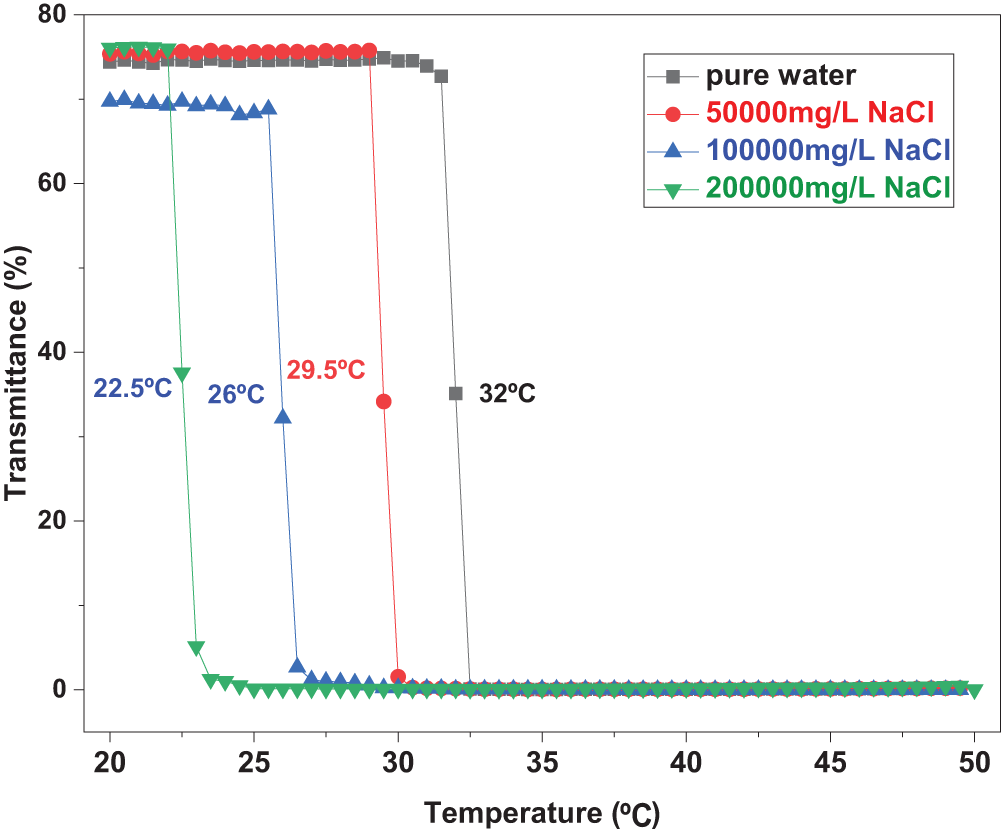

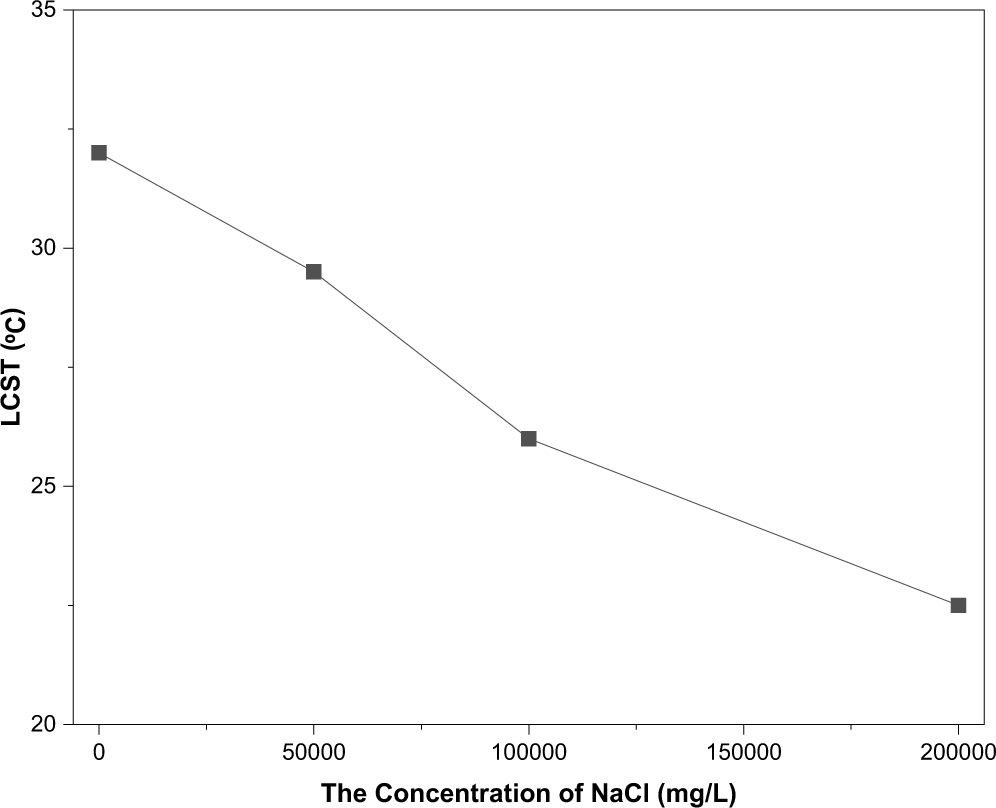

3.3 Temperature-Sensitive Test

The incorporation of NIPAM monomers imparts smart temperature-responsive properties to the HPN terpolymer, which is crucial for its application in downhole environments with varying temperatures. Fig. 6 shows the transmittance change of the HPN aqueous solution during three consecutive heating–cooling cycles. In each cycle, the transmittance decreases upon heating and recovers nearly completely upon cooling, demonstrating excellent reversibility. This confirms the highly reversible thermosensitive phase transition of the PNIPAM segments in HPN, indicating stable temperature-responsive behavior under repeated thermal cycling. As shown in Figs. 7 and 8, the transmittance of the HPN solution decreases significantly with increasing temperature, indicating phase separation due to the contraction of PNIPAM segments. Moreover, as the NaCl concentration increases from 0 mg/L to 200,000 mg/L, the LCST decreases almost linearly from 32°C to 22.5°C. The addition of NaCl disrupts the hydrogen bonds between the amide groups of PNIPAM and water molecules, increasing the polarity of the solution and promoting the formation of hydrophobic associative structures, thereby facilitating polymer aggregation. Furthermore, the presence of NaCl reduces the number of water molecules per unit volume around the copolymer, weakening hydrophilic interactions and making the polymer more prone to aggregation [28].

Figure 6: The light transmittance curves of HPN in pure water during three consecutive heating-cooling cycles

Figure 7: The variation curves of the light transmittance of HPN solution with temperature in different salt solutions

Figure 8: The curve of LCST varying with salt concentration

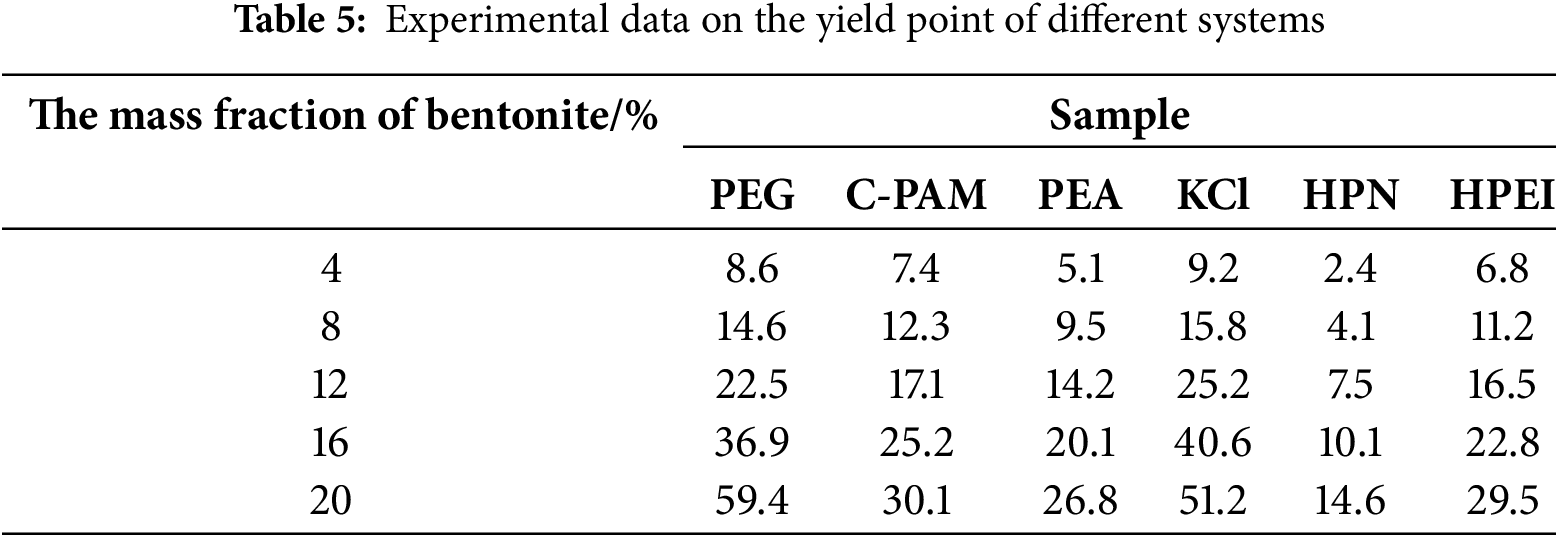

The clay slurry preparation experiment effectively demonstrates the inhibitory effect of shale inhibitors on clay hydration and dispersion. Table 5 displays the YP of bentonite slurries prepared with different inhibitor solutions. As shown in the figure, at a 20% bentonite concentration, the YP values for each inhibitor are as follows: 59.4 Pa (PEG), 30.1 Pa (C-PAM), 26.8 Pa (PEA), 51.2 Pa (KCl), 29.5 Pa (HPEI), and 14.6 Pa (HPN). Traditional inhibitors like KCl and PEA exhibited a significant increase in YP under high bentonite concentrations, indicating limited inhibition capability. In contrast, HPN consistently showed the lowest YP across all bentonite concentrations, demonstrating its effectiveness in suppressing clay hydration and preventing the formation of network structures, thereby significantly improving slurry rheological properties. This superior performance stems from HPN’s unique cationic-nonionic amphiphilic structure, which not only strongly adsorbs and encapsulates clay particles to inhibit hydration swelling but also leverages its hydrophobic groups and thermosensitive properties to enhance plugging and inhibition capabilities at elevated temperatures. Consequently, HPN achieves higher recovery rates and superior clay slurry inhibition at equivalent concentrations.

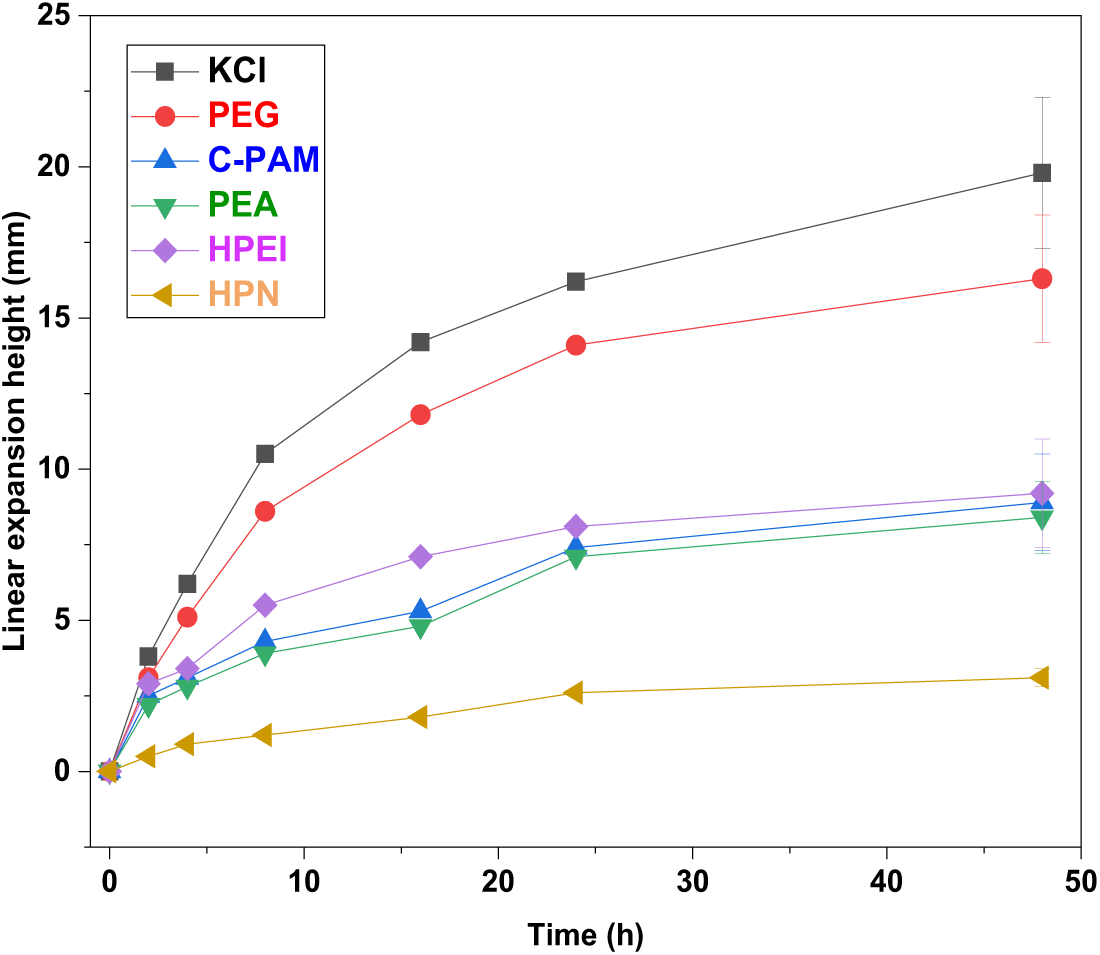

According to Fig. 9, the final swelling heights of several different types of inhibitors are 19.8 mm (KCl), 16.3 mm (PEG), 8.9 mm (C-PAM), 8.4 mm (PEA), and 3.1 mm (HPN). The curves for KCl and PEG exhibit steep slopes during the initial stage (0–10 h), indicating rapid expansion rates, before gradually stabilizing. In contrast, the curves for C-PAM and PEA show relatively gentle slopes, demonstrating their effectiveness in slowing the hydration expansion. The curve for HPN is the flattest, with minimal changes in swelling height throughout the experiment, highlighting its exceptional performance in inhibiting hydration swelling. This superiority is attributed to HPN’s hyperbranched cationic skeleton, amphiphilic structure, and hydrophobic interactions, which collectively form the most effective physical barrier and chemical adsorption, thereby achieving optimal inhibitory performance.

Figure 9: The curve of linear expansion height over time (Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3))

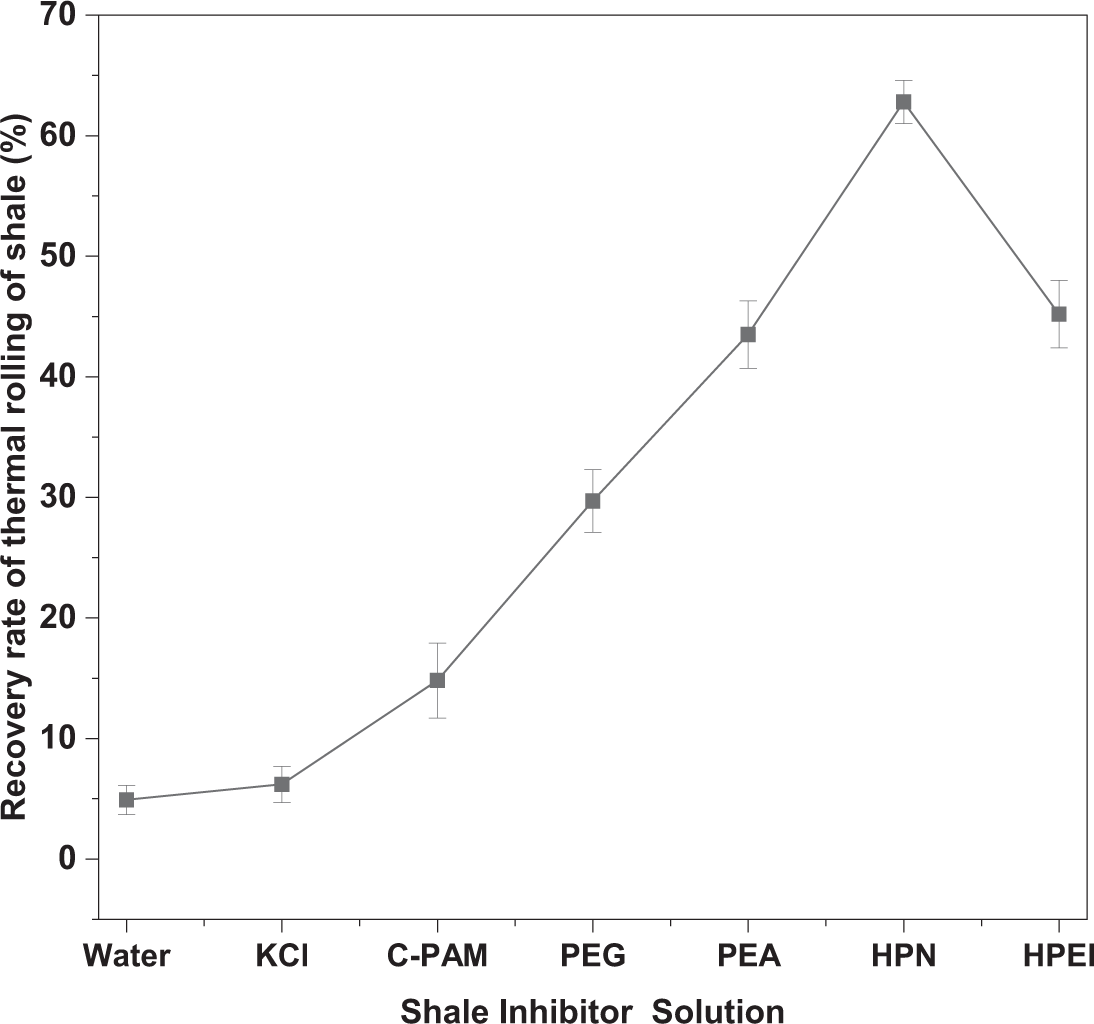

As shown in Fig. 10, under consistent concentration conditions, the recovery rate of shale cuttings in KCl solution was only 6.2%, representing a marginal increase of merely 1.3% compared to that in pure water. This minimal improvement indicates poor shale inhibition by KCl. In contrast, HPN significantly outperformed other inhibitors such as C-PAM, PEG, and PEA, achieving a recovery rate of 62.8%—ten times higher than that of KCl. These results demonstrate the superior shale inhibition capability of HPN.

Figure 10: Recovery of shale cuttings after being hot-rolled in HPN solutions and other inhibitors (Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3))

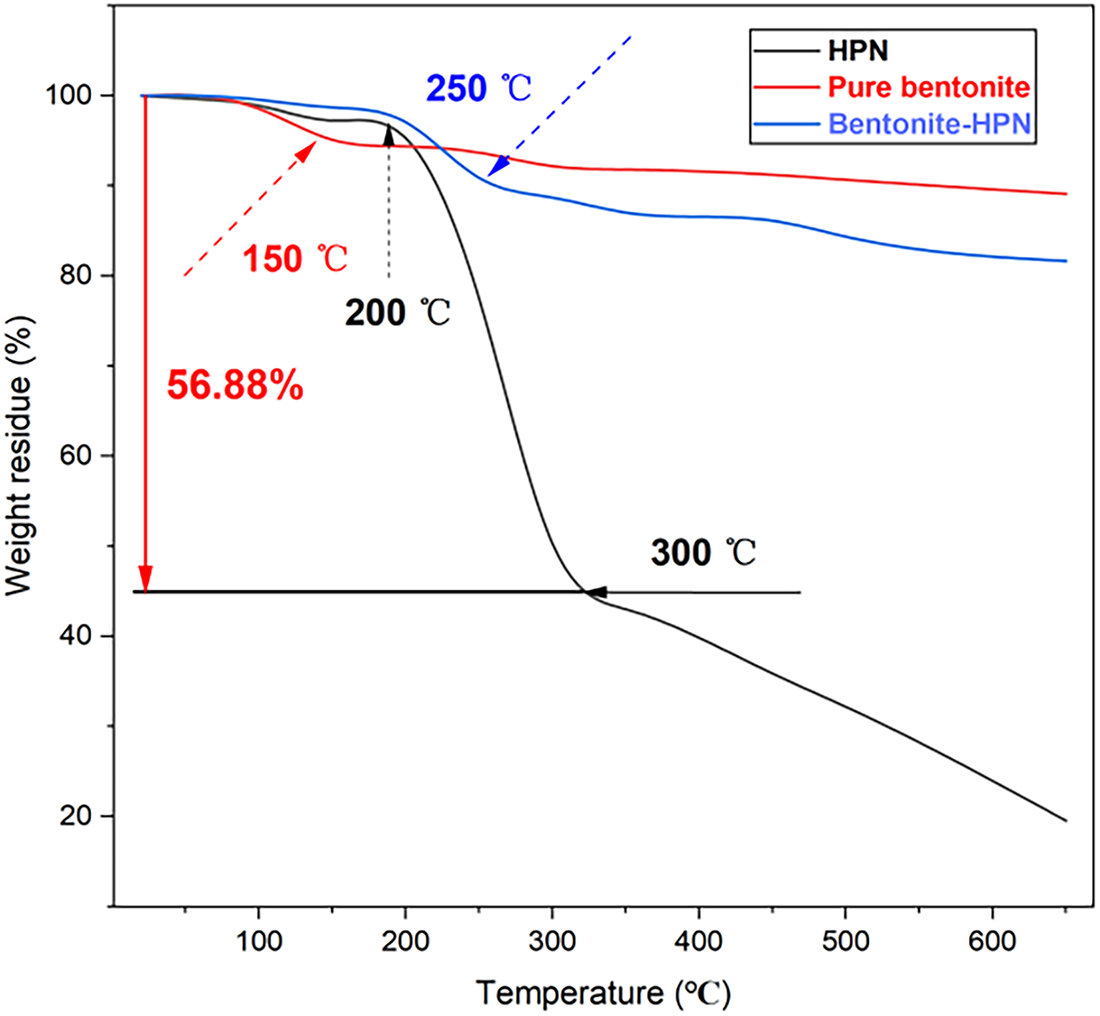

The thermal stability of HPN and its inhibitory effect on bentonite hydration were investigated by TGA, as shown in Fig. 11. According to previous studies, the steep decrease in TGA curves between room temperature and 200°C is primarily attributed to the evaporation of the water adsorbed between the layers [29]. The weight loss of bentonite at ≥200°C was attributed to the dehydroxylation of bentonite and degradation of organic components [30]. The TGA curve of the pure HPN polymer shows excellent thermal stability, with only about 4% mass loss below 250°C, which is mainly attributed to the evaporation of residual moisture. The major thermal decomposition of HPN occurs above 250°C, confirming the high thermal resistance of its hyperbranched backbone and grafted chains. The TGA curve of pure bentonite, in comparison, displays two main mass-loss stages: a 4.15% loss below 110°C due to the removal of physically adsorbed and interlayer water, and a further loss up to 10.12% by 550°C, attributed to dehydroxylation of the clay structure. Notably, in this study, the bentonite-HPN system shows markedly improved thermal and hydration stability compared to pure bentonite. The total mass loss below 250°C is only 9.11%, significantly lower than that of pure bentonite. This indicates that HPN not only possesses intrinsic thermal stability but also effectively hinders water penetration into the clay interlayers and retards its release, owing to the hydrophobic barrier formed by grafted PO and NIPAM groups on the clay surface. These results collectively demonstrate that HPN not only imparts enhanced thermal stability to bentonite but also maintains its own structural integrity under high-temperature conditions, validating its suitability for high-temperature drilling applications.

Figure 11: TGA analysis curve of HPN, pure bentonite, and bentonite-HPN

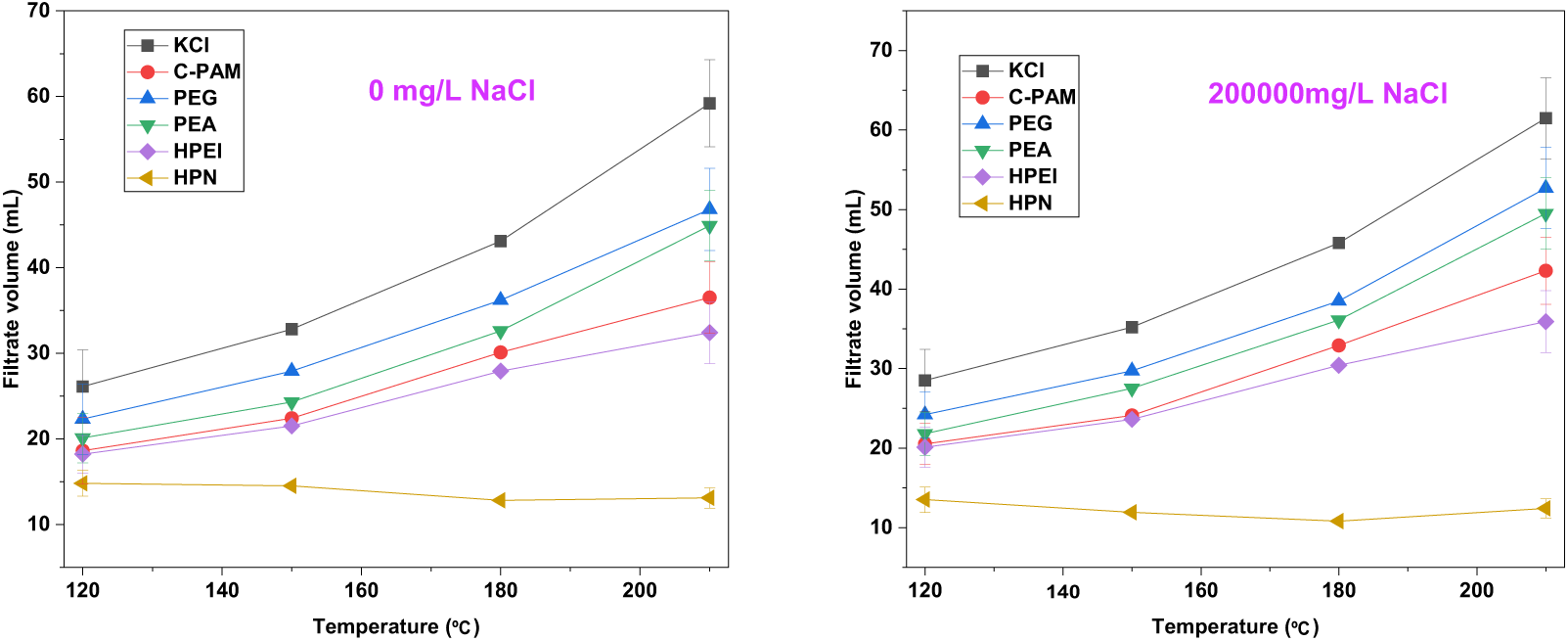

As shown in Fig. 12, the HTHP fluid loss tests demonstrated that HPN exhibits exceptional fluid loss control capability across a wide temperature range (120°C–210°C) and under high-salinity conditions (200,000 mg/L NaCl). Its fluid loss volume was consistently maintained at a low level (<16 mL) and even further decreased under high-temperature and high-salinity environments, whereas conventional inhibitors (e.g., KCl and C-PAM) showed a sharp increase in fluid loss with rising temperature. This performance is attributed to HPN’s synergistic mechanism: the cationic backbone anchors onto the clay surface via electrostatic interactions, forming an initial barrier; when the temperature exceeds the LCST, the PNIPAM chains undergo hydrophobic collapse and synergistically aggregate with the PPO segments, actively plugging micro-fractures; the high-salinity environment enhances hydrophobic association through the “salting-out” effect, advancing and strengthening the density of the plugging layer. Consequently, HPN harnesses downhole challenges like high temperature and salinity, ensuring efficient wellbore stabilization.

Figure 12: The variation curves of the HTHP fluid loss after being hot-rolled in HPN solutions and other inhibitors (Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3)). Error bars represent ± standard deviation (n = 3). For clarity, error bars are shown only for the 120°C and 210°C data points

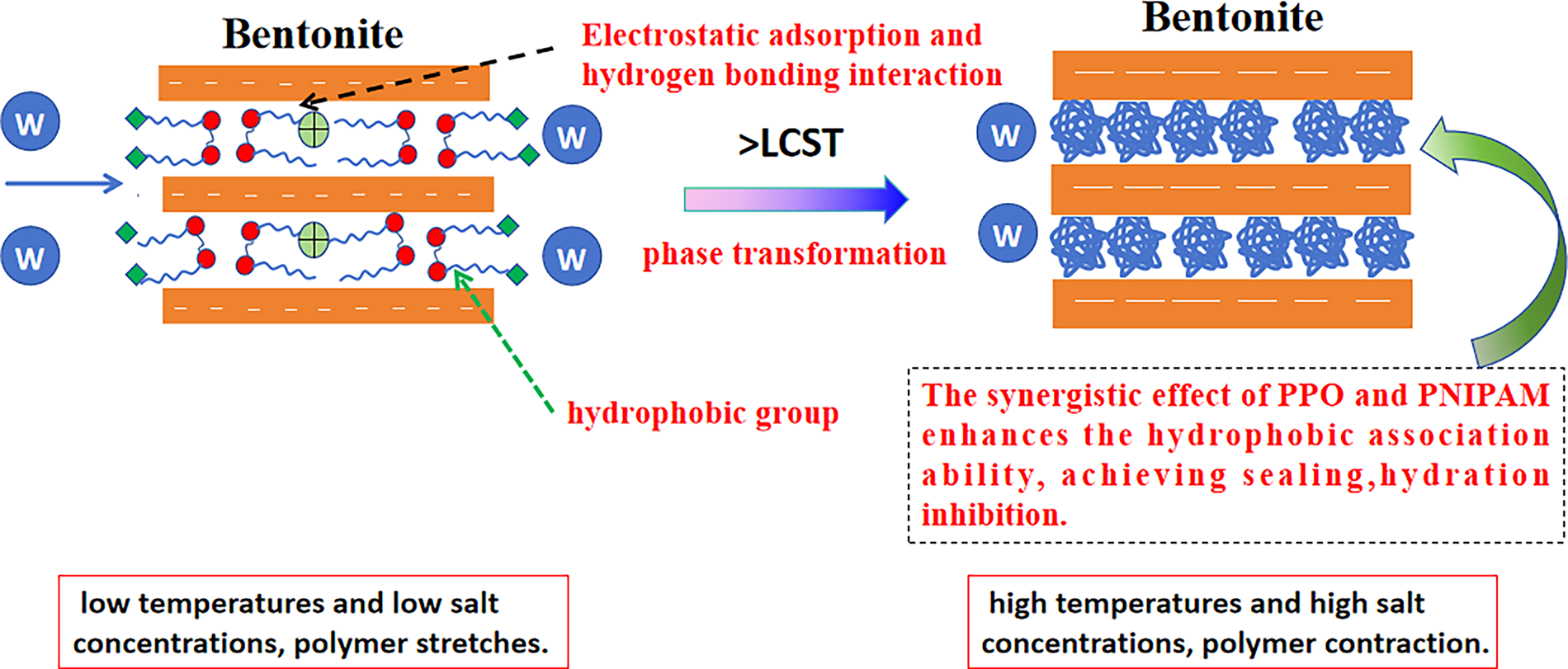

3.5 Analysis of the Synergistic Mechanism of HPN

HPN, as an intelligent shale inhibitor, achieves its exceptional performance through the synergistic interplay of its “cationic-hydrophobic-thermoresponsive” ternary molecular structure. The hyperbranched polyethyleneimine backbone, rich in cationic amine groups, first firmly anchors the polymer onto clay surfaces via robust electrostatic attraction and hydrogen bonding. Subsequently, the inherent hydrophobicity of the PPO segments provides fundamental hydrophobic shielding, while the PNIPAM chains, in their hydrophilic extended state below the LCST, form a hydrated coating layer, collectively inhibiting initial clay hydration. Ultimately, under the challenging downhole conditions of high temperature and high salinity, the temperature surpassing the LCST triggers the hydrophobic collapse of the PNIPAM chains. Concurrently, the “salting-out” effect from salt ions intensifies the hydrophobic association. These two mechanisms act in concert, driving the HPN molecules to form a dense physical sealing layer on the clay surface and within micro-fractures. This dynamic process ingeniously transforms environmental challenges—typically detrimental to conventional inhibitors—into signals for enhanced performance. Through the triple synergy of electrostatic anchoring, hydrophobic association, and thermoresponsive plugging, the mechanistic schematic is illustrated in Fig. 13.

Figure 13: Schematic diagram of the hydration inhibition mechanism of HPN

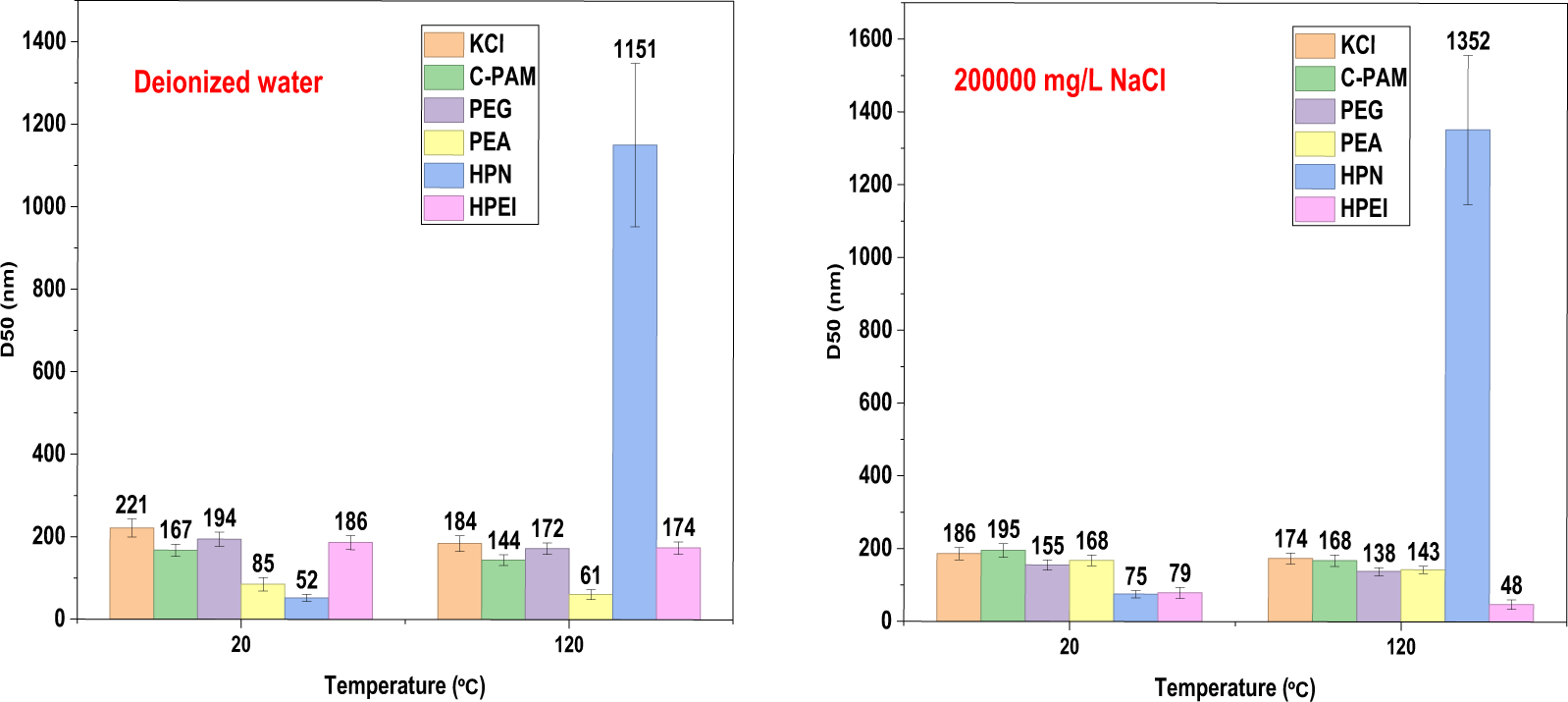

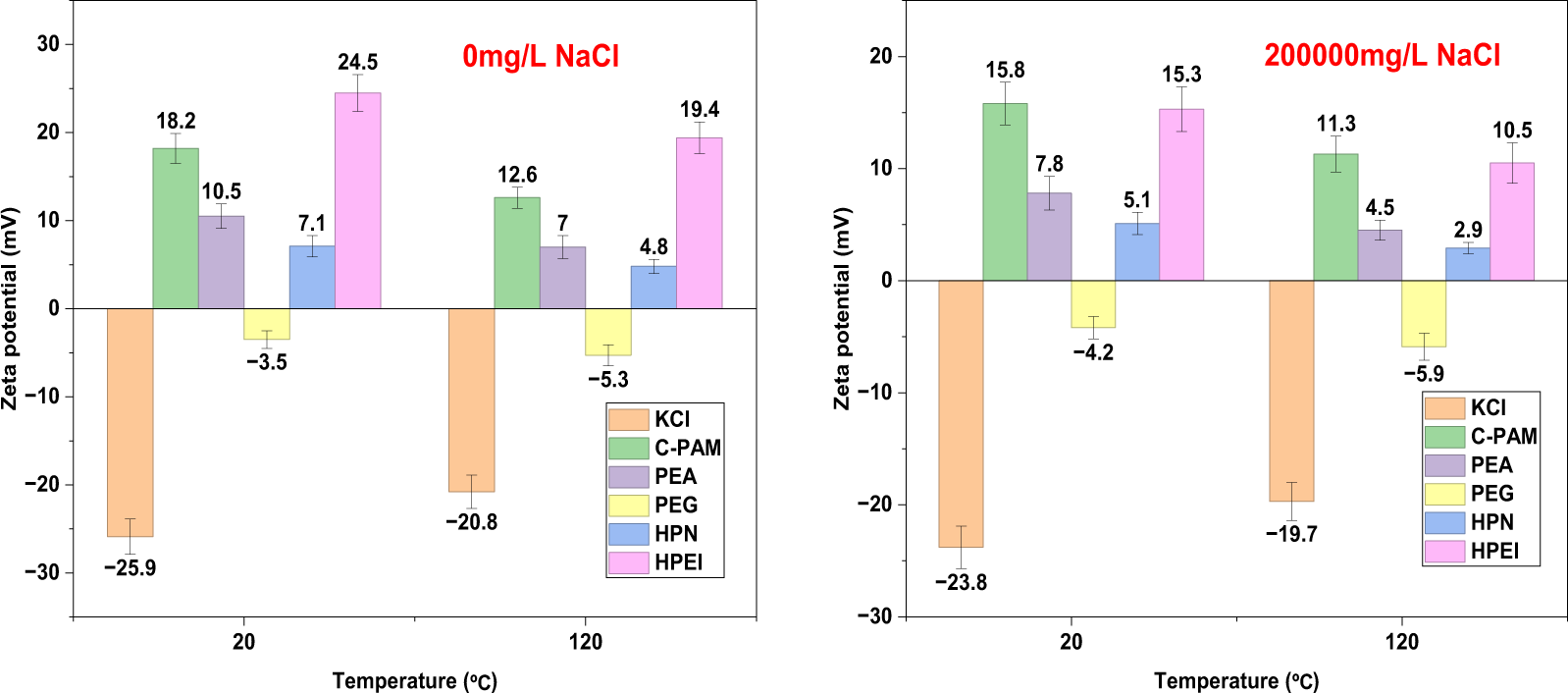

Fig. 14 and Table 6 clearly illustrate the changes in the average particle size (D50) of bentonite treated with five different inhibitors under varying conditions—before and after the LCST (20°C and 120°C) and at different NaCl concentrations. Among the five samples, HPN exhibits the most significant variation in particle size. Notably, only HPN shows a gradual increase in D50 under the combined influence of temperature and salt. In contrast, the other inhibitors display opposite trends. Specifically, in the absence of salt, the D50 of HPN-treated bentonite increases from 52 nm to 1151 nm, and further rises from 75 nm to 1352 nm under saline conditions. This is consistent with the LCST effect of salt on the polymer in Fig. 7, that is, salt causes the polymer to shrink and leads to aggregation. This indicates that HPN possesses superior flocculation and aggregation capabilities, thereby enhancing its effectiveness in preventing wellbore dispersion. This performance can be attributed to three main mechanisms: Low-Temperature Encapsulation and Dispersion Inhibition. At lower temperatures, the cationic backbone of HPN strongly adsorbs onto clay surfaces, while its hydrophilic segments form a hydrated barrier that effectively blocks water ingress and suppresses clay dispersion, thereby optimizing slurry rheology. High-Temperature Aggregation and Sealing: Elevated temperatures trigger the hydrophobic collapse of the temperature-sensitive segments, generating strong hydrophobic driving forces that promote the formation of dense, large aggregates capable of physically sealing formation fractures. Salt-Tolerance Synergy: Salt ions enhance the temperature-responsive behavior through a “salting-out” effect, inducing earlier and more robust aggregation under high-salinity conditions. This synergistic effect ensures improved performance rather than degradation.

Figure 14: The variation curves of the average particle size D50 of bentonite with different inhibitors at different temperatures and NaCl concentrations (Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3))

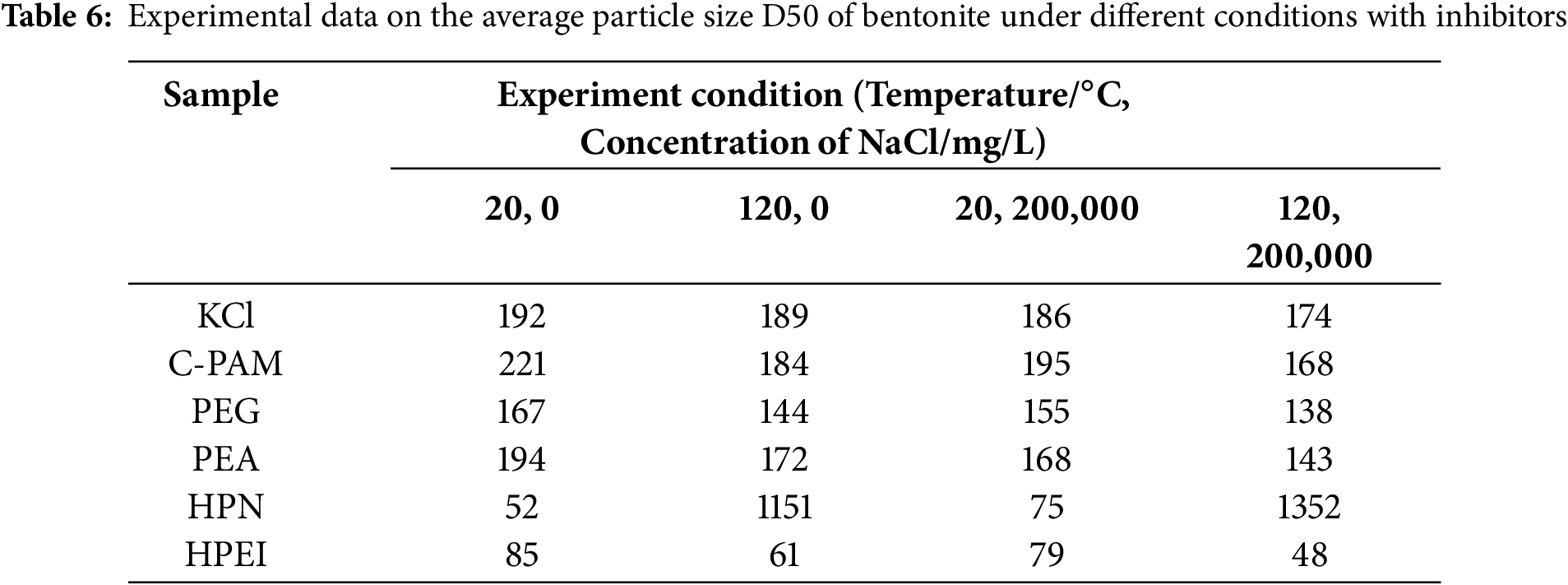

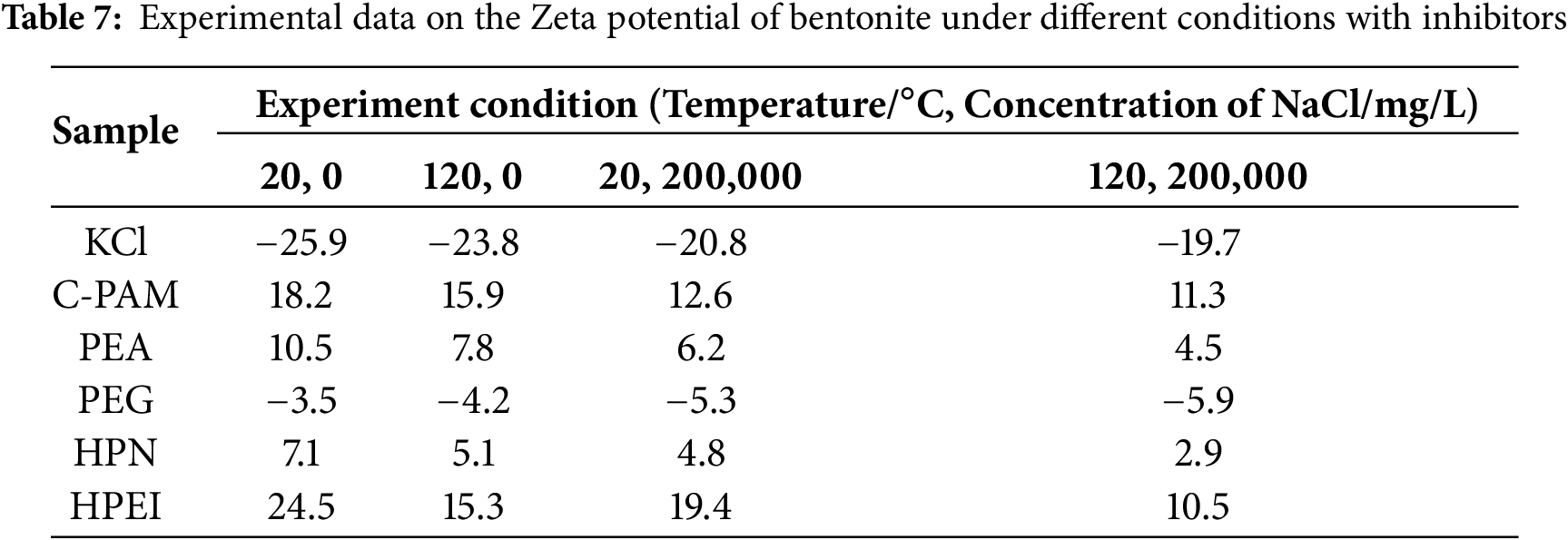

Zeta potential analysis reveals distinct electrochemical behaviors among the inhibitors (Fig. 15, Table 7). The corrected data align with theoretical expectations: KCl shows negative potentials, confirming its ion-exchange mechanism. C-PAM exhibits high but declining positive potentials under harsh conditions, highlighting its electrostatic dependency. PEA displays moderate positive charges, while PEG, as a non-ionic polymer, shows weak negative potentials, relying solely on steric hindrance. The key insight comes from HPN, which maintains a stable, weakly positive potential (+2.9 to +7.1 mV) across all conditions. This “weak but stable” profile reflects its smart molecular design: grafted PO and NIPAM chains reduce cationic density, shifting the mechanism from pure electrostatic adsorption to a robust synergy of hydrophobic association and temperature-responsive plugging. This transformation enables HPN to harness, rather than suffer from, challenging downhole conditions.

Figure 15: The variation curves of the Zeta potential of bentonite with different inhibitors at different temperatures and NaCl concentrations (Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3))

3.6 Biological Toxicity Analysis

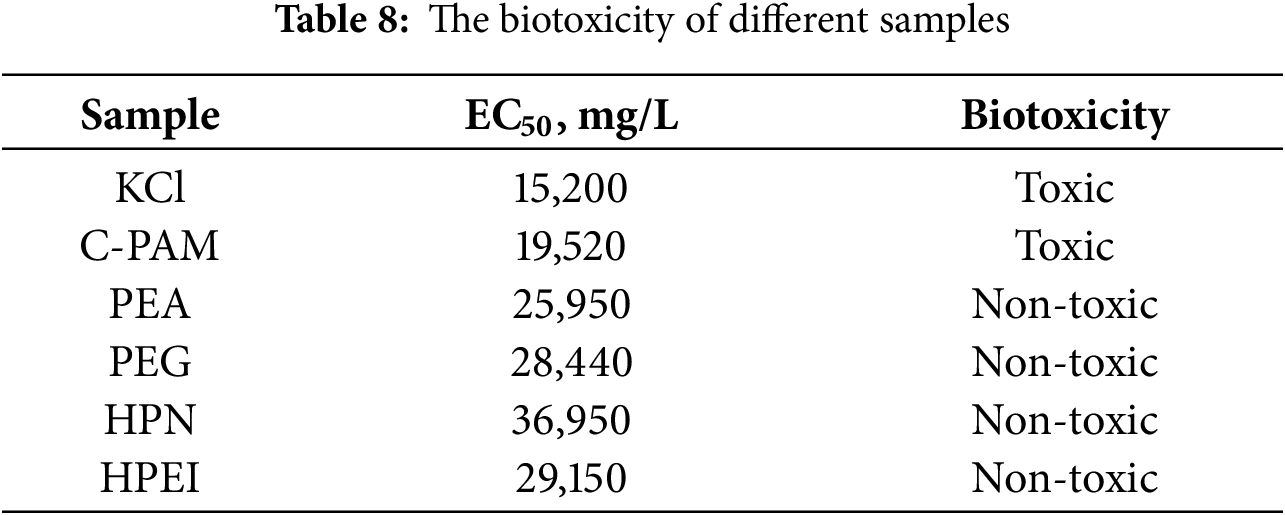

The EC50 of WBDF was tested by the luminescent bacteria method according to the relative industry standard (Q/SY 111–2007, Garding and determination of the biotoxicity of chemicals and drilling fluids—Luminescent bacteria test) [31], and the results are listed in Table 8. The EC50 results of the three groups of samples are as follows: 15,200 mg/L (KCl), 19,250 mg/L (C-PAM), 25,950 mg/L (PEA), 28,440 mg/L (PEG), 29,150 mg/L (HPEI), and 36,950 mg/L (HPN). According to the biological toxicity grade classification standard, when the EC50 was larger than 25,000 mg/L, WBDF was nontoxic. If the EC50 exceeded 30,000 mg/L, the emission standard was achieved [32]. Therefore, the experimental samples with the addition of HPN were considered completely non-toxic. On the contrary, the samples with the addition of C-PAM and KCl were toxic and could not meet the environmental protection emission requirements, having certain limitations.

In summary, this study successfully developed and evaluated a novel thermo-responsive terpolymer (HPN) as an efficient shale inhibitor. The following conclusions are drawn:

(1) Successful Synthesis and Structural Confirmation. The HPN terpolymer was successfully synthesized via a two-step grafting method. Beyond FTIR evidence, GPC verified a controlled molecular weight increase and high grafting efficiency, confirming a well-defined graft copolymer structure free of significant cross-linking.

(2) Exceptional and “Salt-Activated” Inhibition Performance. HPN outperformed conventional inhibitors (KCl, C-PAM, PEG, PEA, HPEI), achieving a low yield point (14.6 Pa), minimal swelling (3.1 mm), and high shale recovery (62.8%). Uniquely, it exhibited a “salt-activated” enhancement under high salinity (200,000 mg/L NaCl), overcoming the limits of electrostatic-dependent inhibitors.

(3) Synergistic Mechanism and Field Application Potential. HPN operates through a synergistic mechanism combining electrostatic adsorption, hydrophobic association, and thermoresponsive aggregation. This multi-modal action, along with proven thermal stability, effective fluid loss control, and low biotoxicity, makes HPN a promising and eco-friendly inhibitor for demanding drilling conditions.

Due to the limitations of time and experimental equipment, this study still has the following deficiencies. Future work will focus on validating the industrial readiness of HPN through standard API tests and compatibility studies with full drilling fluid formulations. To further elucidate the synergistic inhibition mechanism, advanced characterization techniques such as scanning electron microscopy will be employed to directly observe the morphological changes of shale surfaces and the formation of polymer-clay composites. Field trials are also recommended to fully assess its performance under realistic conditions.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the support from the Major Scientific and Technological Project of China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC-KJ135ZDXM38ZJ05ZJ).

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Major Scientific and Technological Project of China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC-KJ135ZDXM38ZJ05ZJ).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Wenjun Hu; data collection, Wenjun Hu; writing—review and editing, Liquan Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Xin X, Yu G, Chen Z, Wu K, Dong X, Zhu Z. Effect of non-newtonian flow on polymer flooding in heavy oil reservoirs. Polymers. 2018;10(11):1225. doi:10.3390/polym10111225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Aftab A, Ismail AR, Ibupoto ZH, Akeiber H, Malghani MGK. Nanoparticles based drilling muds a solution to drill elevated temperature wells: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;76:1301–13. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ikram R, Jan BM, Vejpravova J. Towards recent tendencies in drilling fluids: application of carbon-based nanomaterials. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;15(1):3733–58. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.09.114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Karakosta K, Mitropoulos AC, Kyzas GZ. A review in nanopolymers for drilling fluids applications. J Mol Struct. 2021;1227(2):129702. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Anderson RL, Ratcliffe I, Greenwell HC, Williams PA, Cliffe S, Coveney PV. Clay swelling—a challenge in the oilfield. Earth Sci Rev. 2010;98(3–4):201–16. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2009.11.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Pašić B, Gaurina Međimurec N, Matanović D. Wellbore instability: causes and consequences. Rud Geološko Naft Zb. 2007;19(1):87–98. doi:10.5586/asbp.1975.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Liu X, Xiao Y, Ding Y. Research progress and prospects of nano plugging agents for shale water-based drilling fluids. ACS Omega. 2025;10(6):5138–47. doi:10.1021/acsomega.4c07942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. O’Brien DE, Chenevert ME. Stabilizing sensitive shales with inhibited, potassium-based drilling fluids. J Petrol Technol. 1973;25(9):1089–100. doi:10.2118/4232-pa. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Saleh TA, Ibrahim MA. Advances in functionalized nanoparticles based drilling inhibitors for oil production. Energy Rep. 2019;5(2):1293–304. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2019.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Li Q, Zhu DY, Zhuang GZ, Li XL. Advanced development of chemical inhibitors in water-based drilling fluids to improve shale stability: a review. Petrol Sci. 2025;22(5):1977–96. doi:10.1016/j.petsci.2025.03.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Abdullah AH, Ridha S, Mohshim DF, Yusuf M, Kamyab H, Krishna S, et al. A comprehensive review of nanoparticles: effect on water-based drilling fluids and wellbore stability. Chemosphere. 2022;308(1):136274. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Ahmed HM, Kamal MS, Al-Harthi M. Polymeric and low molecular weight shale inhibitors: a review. Fuel. 2019;251(4):187–217. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2019.04.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ahmad HM, Murtaza M, Shakil Hussain SM, Mahmoud M, Kamal MS. Performance evaluation of different cationic surfactants as anti-swelling agents for shale formations. Geoenergy Sci Eng. 2023;230:212185. doi:10.1016/j.geoen.2023.212185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Chu Q, Lin L, Zhao Y. Hyperbranched polyethylenimine modified with silane coupling agent as shale inhibitor for water-based drilling fluids. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2019;182(3):106333. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2019.106333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Caminade AM, Beraa A, Laurent R, Delavaux-Nicot B, Hajjaji M. Dendrimers and hyper-branched polymers interacting with clays: fruitful associations for functional materials. J Mater Chem A. 2019;7(34):19634–50. doi:10.1039/c9ta05718h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhong H, Qiu Z, Sun D, Zhang D, Huang W. Inhibitive properties comparison of different polyetheramines in water-based drilling fluid. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2015;26(22):99–107. doi:10.1016/j.jngse.2015.05.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kiiza J, Xu J. Functional groups optimization at molecular-scale to improve polyamine treatment agent performance on sodium bentonite surface hydration inhibition under high-temperature/high-pressure failure. Chem Phys. 2025;594(44):112649. doi:10.1016/j.chemphys.2025.112649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang C, Liu J, Liu P, Wang W, Chen H, Bai L, et al. Phytic acid extracted cellulose nanocrystals for designing self-healing and anti-freezing hydrogels’ flexible sensor. Chem Eng J. 2024;493:152276. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.152276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li Y, Tang L, Zhu C, Liu X, Wang X, Liu Y. Fluorescent and colorimetric assay for determination of Cu(II) and Hg(II) using AuNPs reduced and wrapped by carbon dots. Microchim Acta. 2021;189(1):10. doi:10.1007/s00604-021-05111-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ye J, Ahmatjan Z, Wu H, Meng J. Hyperbranched polyethyleneimine as a building block of the surface grafting layer of a HCIC cellulose membrane adsorber for IgG separation. J Appl Polym Sci. 2025;142(30):e57233. doi:10.1002/app.57233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mavroidi B, Lyra KM, Pispas S, Sideratou Z, Tsiourvas D. Hyperbranched polyethyleneimine-coordinated copper(II) metallopolymers with preferential targeting to prostate cancer cells. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18(8):1189. doi:10.3390/ph18081189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Gu J, Lin T, Dai Y, Li H, Zhou Y, Liu X, et al. In situ synthesis of AuNPs by hyperbranched polyethyleneimine-functionalized apple pomace-derived cellulose as recyclable catalysts for 4-nitrophenol reduction. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;306(4):141799. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.141799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ferreira CC, Teixeira GT, Lachter ER, Nascimento RSV. Partially hydrophobized hyperbranched polyglycerols as non-ionic reactive shale inhibitors for water-based drilling fluids. Appl Clay Sci. 2016;132(7):122–32. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2016.05.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. An Y, Yu P. A strong inhibition of polyethyleneimine as shale inhibitor in drilling fluid. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2018;161:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2017.11.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jiang G, Qi Y, An Y, Huang X, Ren Y. Polyethyleneimine as shale inhibitor in drilling fluid. Appl Clay Sci. 2016;127:70–7. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2016.04.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Shamlooh M, Hamza A, Hussein IA, Nasser MS, Salehi S. Investigation on the effect of mud additives on the gelation performance of PAM/PEI system for lost circulation control. In: Proceedings of the SPE Europec Featured at 82nd EAGE Conference and Exhibition; 2021 Oct 18–21; Amsterdam, The Netherlands. doi:10.2118/205184-ms. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Li XL, Jiang GC, Xu Y, Deng ZQ, Wang K. A new environmentally friendly water-based drilling fluids with laponite nanoparticles and polysaccharide/polypeptide derivatives. Petrol Sci. 2022;19(6):2959–68. doi:10.1016/j.petsci.2022.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Deen GR. Solution properties of water-soluble “smart” poly(N-acryloyl-N′-ethyl piperazine-co-methyl methacrylate). Polymers. 2012;4(1):32–45. doi:10.3390/polym4010032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Alabarse FG, Conceição RV, Balzaretti NM, Schenato F, Xavier AM. In-situ FTIR analyses of bentonite under high-pressure. Appl Clay Sci. 2011;51(1–2):202–8. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2010.11.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Makhoukhi B, Villemin D, Didi MA. Preparation, characterization and thermal stability of bentonite modified with bis-imidazolium salts. Mater Chem Phys. 2013;138(1):199–203. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.11.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ma XY, Wang XC, Ngo HH, Guo W, Wu MN, Wang N. Bioassay based luminescent bacteria: interferences, improvements, and applications. Sci Total Environ. 2014;468:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yang X, Shang Z, Liu H, Cai J, Jiang G. Environmental-friendly salt water mud with nano-SiO2 in horizontal drilling for shale gas. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2017;156(1):408–18. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2017.06.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools