Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Performance Evaluation of Hierarchically Structured Superhydrophobic PVDF Membranes for Heavy Metals Removal via Membrane Distillation

1 Centre for Rural Development and Technology, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, New Delhi, 110016, India

2 Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3E5, Canada

* Corresponding Authors: Pooja Yadav. Email: ; Vivek Kumar. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 1181-1197. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.072564

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 26 November 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

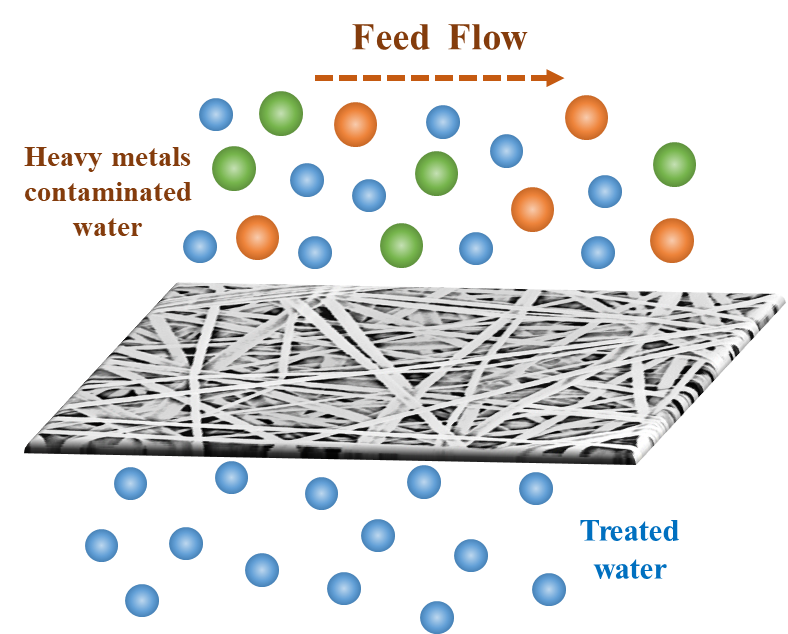

Heavy metal contamination in water sources is a widespread global concern, particularly in developing nations, with various treatment approaches under extensive scientific investigation. In the present study, we fabricated electrospun composite polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanofibrous membranes exhibiting hierarchical surface roughness and superhydrophobicity for the removal of heavy metal ions via vacuum membrane distillation (VMD) process. The membranes were prepared by incorporating optimized dosing of silica nanoparticles, followed by a two-step membrane modification approach. These membranes exhibited notable characteristics, including elevated water contact angle (152.8 ± 3.2°), increased liquid entry pressure (127 ± 6 kPa), and reduced average pore size (0.28 ± 0.03 μm). The study demonstrated the efficacy of fabricated membranes in VMD process, specifically for the removal of heavy metals such as arsenic and iron from aqueous solutions. The membrane produced stable permeate flux of 12.7 kg·m−2·h−1 for arsenic-containing feed and 13.2 kg·m−2·h−1 for iron-containing feed, and excellent rejection of >99.9% over a 12-h testing period without any observed wetting of membrane pores. These performance results were compared with those of typical commercial PVDF and pristine electrospun PVDF membranes. Consequently, the developed membrane demonstrated high efficiency and scalability as a water treatment option, showing significant potential for industrial heavy metal removal and the treatment of contaminated groundwater.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Groundwater is one of the most valuable natural assets on Earth. In recent decades, there has been a substantial rise in its exploitation due to rising population and developmental activities across various regions globally [1]. Therefore, ensuring safe drinking water to the world’s population is a significant challenge; however, in the 21st century, there has been a notable rise in global efforts to address groundwater quality issues. Over the last decade, there have been numerous reports of groundwater contamination from various chemical constituents exceeding the WHO limits in aquifers worldwide, making them non-potable. For instance, recently, the increasing presence of arsenic (As) pollution in groundwater has emerged as a significant concern, both globally and in the Indian peninsula [2]. Similarly, the presence of high levels of iron (Fe) has been reported in many states of India [3]. Further comprehensive details are elaborated in subsequent sections.

Arsenic is the most toxic element present in the environment, and the presence of high levels of arsenic poses adverse health effects on humans through drinking water contamination. Arsenic contamination in water is generally inorganic, existing in forms arsenate (As(V)) and arsenite (As(III)), and is traced back to natural causes like weathering and erosion of rocks, volcanic emissions, leaching from arsenic rich minerals and several anthropogenic activities such as ceramic manufacturing industries, petroleum refining, agricultural chemicals, mining wastes [4]. Arsenic contamination (exceeding WHO permissible limit of 10 μg/L) has been reported in groundwater of approximately 108 countries, among these, almost 80 countries are from the continents Asia, Europe, and Africa, including Nepal, China, Bangladesh, India, Thailand, Pakistan, Hungary, Serbia, Romania, Tanzania, Ethiopia and others [5]. Moreover, arsenic contamination has been frequently reported in groundwater of about 20 Indian states, including Assam, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Chandigarh, Himachal Pradesh, Bihar and the Ganga basin region [4]. Human exposure to arsenic may cause dysfunction of respiratory, dermal, gastrointestinal and neurological organs; the higher levels of arsenic are fatal to infants and children [6]. Chemical oxidation, electrocoagulation, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), ion exchange, adsorption, and membrane-based filtration are commonly used treatment technologies for arsenic decontamination from water [7]. The process of adsorption is widely accepted due to easy operation and high removal efficiency; however, it is dependent on the regenerative ability of adsorbents [8].

Iron is one of the most abundant elements found on Earth, and an important nutrient for humans, present in haemoglobin, myoglobin and several other proteins [9]. The presence of iron in water bodies is due to rainwater percolation and anthropogenic activities like the dumping of industrial and domestic waste, and in groundwater is due to the leaching of rocks [10]. The WHO permissible limit for iron in drinking water is 0.3 mg·L−1, higher concentrations (2–10 mg·L−1) of iron have been reported in West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Assam and other eastern states of India [11]. Consumption of water with high levels of iron may lead to hemochromatosis and cause severe damage to various body organs. Generally, physical impairment such as joint pain, eye disorders, and fatigue are results of initial exposure followed by heart disorders and cancer on prolonged consumption of water having high iron concentration [9]. The conventional treatment processes for iron removal include ion exchange, precipitation, filtration, adsorption, and electrocoagulation [9].

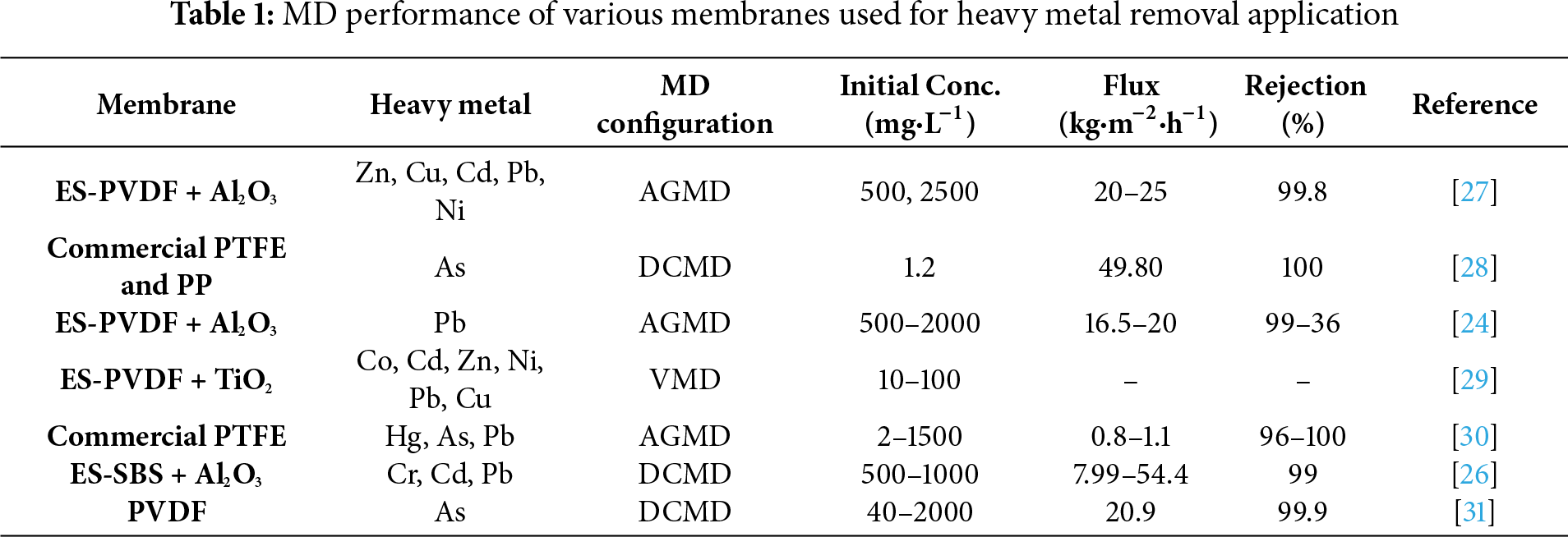

The escalating heavy metal contamination and associated health risks mandate effective heavy metal removal processes to mitigate elevated contamination levels and produce safe and clean water. The researchers and practitioners are highly accepting membrane technology for the removal of heavy metals owing to the high rejection offered by membranes even at low pollutant concentration [12]. The membrane-based treatment processes are easy to build, operate, scale up, and control, and usually safe for the environment; however, these processes face challenges like membrane fouling, low permeability and selectivity, and high energy input for the pressure requirement [13]. The process of membrane distillation (MD) is an emerging technology and is mostly being used for desalination and resource recovery applications [13]. MD functions as a thermally driven process, where the feed and permeate solutions are separated by the hydrophobic microporous membrane. As the feed solution is heated, the temperature difference creates a vapor pressure gradient across the membrane, causing movement of vapors from the feed side to the permeate side through the micro-sized pores of the membrane. These vapors are collected and condensed on the permeate side [14]. MD processes offer less fouling, high contaminant rejection, can be easily integrated with other processes, and may utilize solar/waste heat as the operational temperature and pressure requirements are low [14]. Limiting factors such as frequent membrane wetting, lower rejection and permeate flux hinder the applicability and commercialization of MD process. These factors are usually associated with the membrane fabrication technique [15]. The conventional membrane fabrication techniques like phase inversion and stretching suffer various drawbacks [16]; however, numerous studies have reported the development of new membranes with high hydrophobicity and improved mechanical and permeation properties to produce high flux and excellent rejection during long run operations [17,18]. Recently, the electrospinning technique has gained attention owing to its ability to fabricate nanofibrous membranes of desired properties, such as high porosity and hydrophobicity, crucial for obtaining high flux and preventing membrane pore wetting during MD operations [19]. The electrospun nanofiber membranes (ENMs) offer additional features such as the high surface-to-volume ratio, good mechanical resistance, adjustable pore size and thickness, and interconnected structure [20]. Although the membranes prepared from the single polymer are usually prone to frequent pore wetting due to lower liquid entry pressure (LEP), various modification strategies have been adopted to produce membranes of high hydrophobicity and reduced pore size for MD applications [21]. As reported in the literature, superhydrophobic (water contact angle > 150°) membranes could be obtained by creating hierarchical surface roughness using micro/nano sized materials during the fabrication or modification process of membranes [22]. The high surface roughness has numerous air pockets, which assist in water resistance. Various nanomaterials, such as aluminum oxide (Al2O3), silica oxide (SiO2), and titanium dioxide (TiO2), have been used to achieve superhydrophobic membrane surfaces. Moreover, hydrophobic modification is often carried out by incorporating/coating fluorine-containing agents that provide excellent self-cleaning properties [23]. Table 1 summarizes studies, including the MD process application in the removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater. As seen, while most of the studies reported in the literature have used commercial or phase inversion membranes, the implementation of electrospun nanofiber MD membranes for heavy metal removal is limited. For instance, a study by Attia et al. reports utilization of Al2O3 NPs imbedded PVDF nanofibers for effective removal of lead (Pb) from highly concentrated wastewater [24]. Another study from the same research group reported fabrication of superhydrophobic membranes by electrospraying Al2O3 NPs onto electrospun PVDF nanofibers to produce a high permeate flux of 18.67 kg·m−2·h−1 using a synthetic solution of heavy metals as feed (Pb, Zn, Cu, Cd, Ni) during a long run operation of 30 h [25]. Moreover, Khraisheh et al. reported superior flux rate of 54.4 kg·m−2·h−1 while treating heavy metal (Cr, Cd, Pb) contaminated water using Al2O3 NPs functionalized electrospun styrene-butadiene-styrene (SBS) membranes [26].

As stated earlier, the heavy metal removal application of MD process is not explored much; moreover, limited research is available on the implementation of nanofibrous membranes for heavy metal decontamination via MD. The lack of high-performing and anti-wetting membranes is a major bottleneck in the commercialization of MD process; therefore, further exploration of different fabrication and modification approaches is required. The current study utilizes novel superhydrophobic nanofiber membranes for the removal of heavy metals from synthetic wastewater. These membranes were prepared by following a unique two-step modification strategy that involves acid pre-treatment and fluorination of composite PVDF membranes, as mentioned in our previous study. The modified membranes were characterized for morphological, chemical, and permeability properties and their heavy metal removal potential was investigated within a continuous VMD operation. Therefore, unlike previous works, this study evaluates the continuous VMD operation of composite SiO2-PVDF nanofibrous membranes for heavy metal systems (As and Fe), emphasizing long-term flux stability, anti-wetting performance, and structural stability. This contribution provides new experimental evidence on the sustained performance and durability of superhydrophobic nanofibrous membranes for real-world heavy metal decontamination.

The PVDF polymer powder (MW 441,000 g·mol−1) was procured from Arkema Inc. (Philadelphia, PA, USA). The additives lithium chloride (LiCl), silica nanoparticles (SiO2, particle size 15 nm) and FAS compound (1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorodecyltriethoxysilane, FAS 17) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich Canada Ltd. (Oakville, ON, Canada). Other chemicals, such as acetone, hydrochloric acid, and hexane, were supplied by Caledon Laboratories (Georgetown, ON, Canada). The solvent N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) was supplied by Fisher Chemicals (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Other chemicals, including sodium arsenite (NaAsO2), iron sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O), and iso-propyl alcohol were obtained from Sigma Aldrich Ltd. (St. Louis, MO, USA). A commercial PVDF membrane (Durapore® Microfiltration Membrane) of pore size of 0.22 μm was procured from Merck Millipore Ltd. (Darmstadt, Germany) and used as reference membrane for comparison of MD performance of fabricated membranes. From now on, the commercial membrane is represented as C-PVDF.

The synthetic feed solutions were obtained by dissolving the required amounts of heavy metal salts into distilled water. For example, the 1000 mg·L−1 stock solution for arsenic was prepared by dissolving 1.733 g of NaAsO2 in 1000 mL of DW water. Similarly, the stock solution for iron-contaminated water was obtained by dissolving 4.982 g of FeSO4·7H2O in 1000 mL of DI water. These stock solutions were diluted to obtain the feed solution of desired concentrations of iron and arsenic.

Dry PVDF powder was completely dissolved in a solvent mixture of DMF and acetone (in ratio 6:4) to have 13.5 wt% polymer dope solution to prepare pristine PVDF membranes. For silica-doped PVDF membranes, SiO2 nanoparticles were sonicated for 30 min in pre-mixed acetone/DMF solution, followed by the addition of PVDF solution and through mixing. The resulting solution was composed of 13.5 wt% PVDF and 6 wt% SiO2 nanoparticles. Trace amounts (0.04%) of additive LiCl were added to each solution to increase solution conductivity and enhance electrospinning ability. The polymer solutions were stirred overnight at 150 rpm and 75°C temperature to ensure thorough mixing of components.

The prepared polymer solutions were subjected to the electrospinning (HDE Electric Ltd., Georgetown, ON, USA, Model-KH-1-1) process to fabricate nanofiber membranes. For this, the solution was loaded into a plastic syringe, horizontally placed at a certain distance (10 to 15 cm) from the rotating drum collector (grounded). A syringe pump controlled the solution flow rate, and high voltage supply was connected to the metallic needle of the syringe. The high voltage generates electrostatic field between the needle and collector, such that, the polymer droplet appearing on the needle tip is deformed into conical shape (also known as Taylor cone) immediately, and fiber jet is ejected from the Taylor cone once the electrostatic force surpasses the surface tension of the solution. The solvent vaporizes along the tip-collector distance (TCD) and fibers deposit on the collector. Once the desired thickness is attained, the fiber mat is dried and stored in desiccator for further usage.

2.4 Modification of the Fabricated Membranes

The SiO2-doped fabricated membranes were subjected to a two-step modification scheme, which includes acid pre-treatment followed by fluorination of the membrane surface. During acid-pretreatment, the fabricated membranes were dipped into aqueous solution of hydrochloric acid (1 M concentration) at 60°C. After one hour, the membranes were thoroughly washed with deionized water, followed by drying (at 25°C). The acid-treated membranes were immersed overnight in 1% FAS17 solution at room temperature, followed by through washing using hexane and drying at 80°C. The resultant membranes were stored in desiccator until further use. In subsequent sections, these membranes are referred to as modified PVDF or M-PVDF membranes. The detailed description of the fabrication and modification process is discussed elsewhere [21].

2.5.1 Structural and Compositional Characterization

The morphology of the membrane top surface was observed under scanning electron microscopy (SEM MIRA Tescan). Prior to SEM observation, small pieces of membrane samples were coated with thin layer of gold nanoparticles using a sputter coating system. The coated samples were fixed on metal stubs using carbon tape and observed within a high-vacuum chamber. For determining the surface roughness, the membranes were examined using atomic force microscopy (AFM, WITec ALPHA300 A, Ulm, Germany). A surface area of dimension 2 μm × 2 μm was analyzed using tapping mode, and the data procured was analyzed using Gwyddion (Czech Metrology Institute, Praha, Czech Republic) software. The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (Thermo NICOLET-IS-50) technique was employed for analysis of bonding behaviour and functional groups within the membrane. The transmission was observed within wave number range of 600–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 2 cm−1 using attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory.

2.5.2 Membrane Permeability and Stability

The porosity of the membranes was estimated by the gravimetric method. The membrane samples were submerged in iso-propyl alcohol for one hour, and the weight of fully wetted and oven-dried membranes was measured with an analytical balance and used in the following equation:

where, ε represents the porosity, m1 (g), m2 (g), ρl (g·m−3), and ρp (g·m−3) denote the weight of the wetted membrane sample, weight of dried membrane sample, density of iso-propyl alcohol and the polymer, respectively. Finally, the average porosity of the three samples was considered. Furthermore, the SEM images of the membranes were analysed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). For this, the average pore size of randomly selected 100 pores was calculated. For studying the stability of the fabricated composite membrane, a small piece of dried membrane sample was stirred in distilled water for 24 h at 200 rpm. Following this, the membrane sample was dried and its weight was compared to the initial weight to calculate percentage leaching. Further, the leaching solution was analyzed under Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS, Agilent 7900) technique to observe any leaching of SiO2 nanoparticles.

2.5.3 Wettability and Liquid Entry Pressure

The wetting property of fabricated membranes was investigated by measuring the water contact angle (WCA) of the membrane surface. For this, tiny droplet (2 μL) of deionized water was placed onto dry membrane sample using an automatic micro syringe and examined under contact angle analyser (KRUSS DSA100). The average of five water contact angle readings at different locations was considered. Liquid entry pressure (LEP) of the membrane is a key property for evaluating the wettability of the membrane. In this study, LEP was obtained by using home made set-up which consisted of a membrane cell (surface area: 17.4 cm2), a peristaltic pump and pressure gauge. LEP was measured by securing dry membrane sample into the cell, followed by pressurizing DI water from the feed side, the pressure value was recorded on the appearance of first drop of DI water on the permeate side. This test was repeated thrice for each membrane.

2.6 Vacuum Membrane Distillation Operation

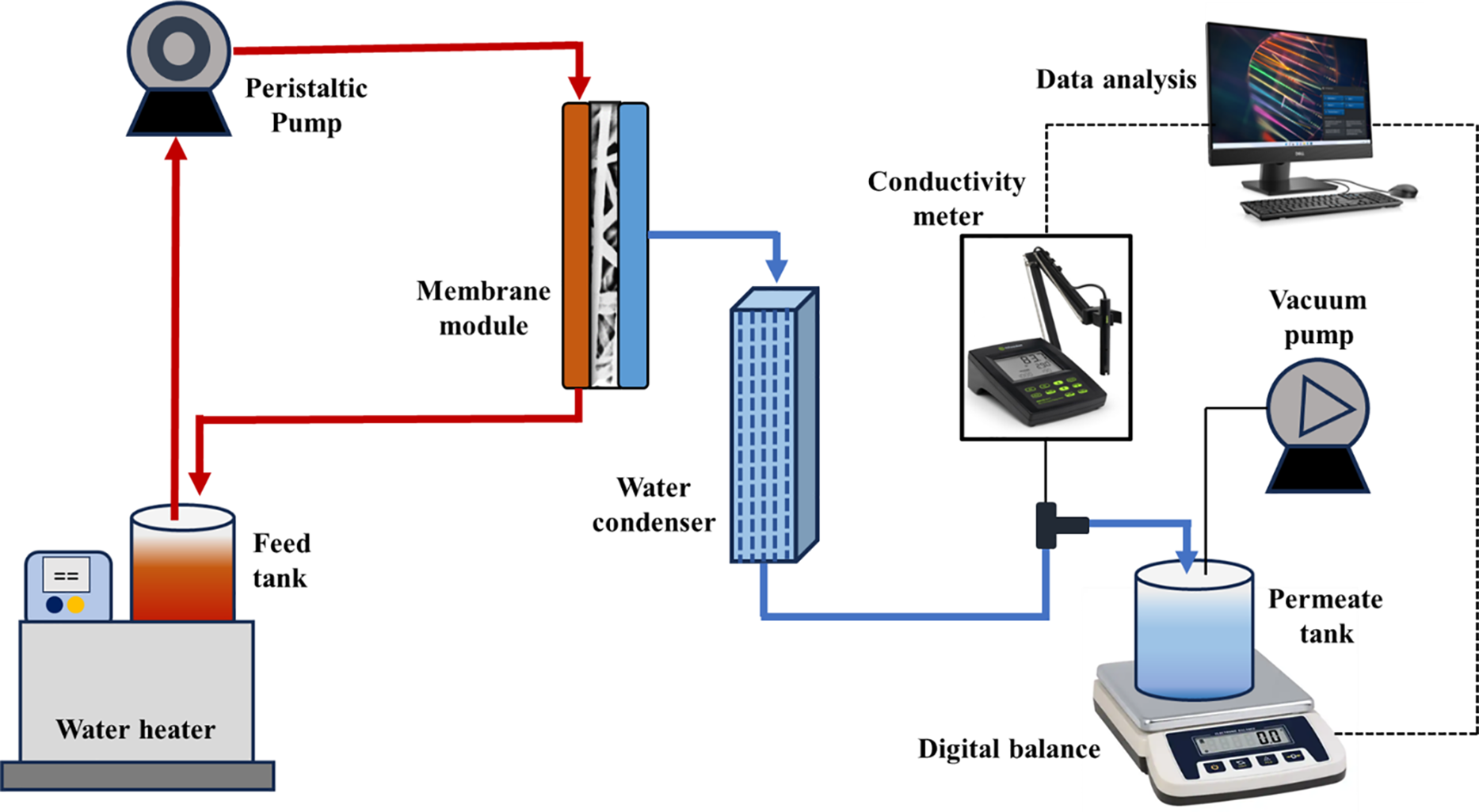

The membranes fabricated in this study were used in a lab-scale custom-made VMD set-up (represented in Fig. 1) for their performance analysis. The setup includes a feed side; having a feed tank, a water heater, and a peristaltic pump, and a permeate side; composed of a condenser, a vacuum pump, and a permeate tank. Both feed and permeate sides are connected to a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane module of 48 cm2 effective area. The feed tank was placed in a water bath heating system that includes a controller and a heater coil. The hot feed (40°C to 80°C) was circulated between the membrane module and feed tank via a peristaltic pump (flow rate 120 mL·min−1). The water vapors on the permeate side were collected using a vacuum pump (Rocker 300, at 6 kPa vacuum) and condensed within a copper tube condenser (at 25°C). The weight of condensed permeate was recorded using an electrical balance. The heavy metal concentration in feed and permeate was determined using the ICP-MS technique. The permeate flux, J in kg·m−2·h−1 and rejection rate, R% were obtained using the following equations:

where, Δm, a, Δt, ρ, Cf, and Cp denote the weight of permeate (kg), effective area of membrane (m2), time duration (h), permeate density (g·cm−3), concentration of feed (mg·L−1) and concentration of permeate, respectively.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of homemade VMD bench scale apparatus used for this study

3.1.1 Structural and Compositional Analysis

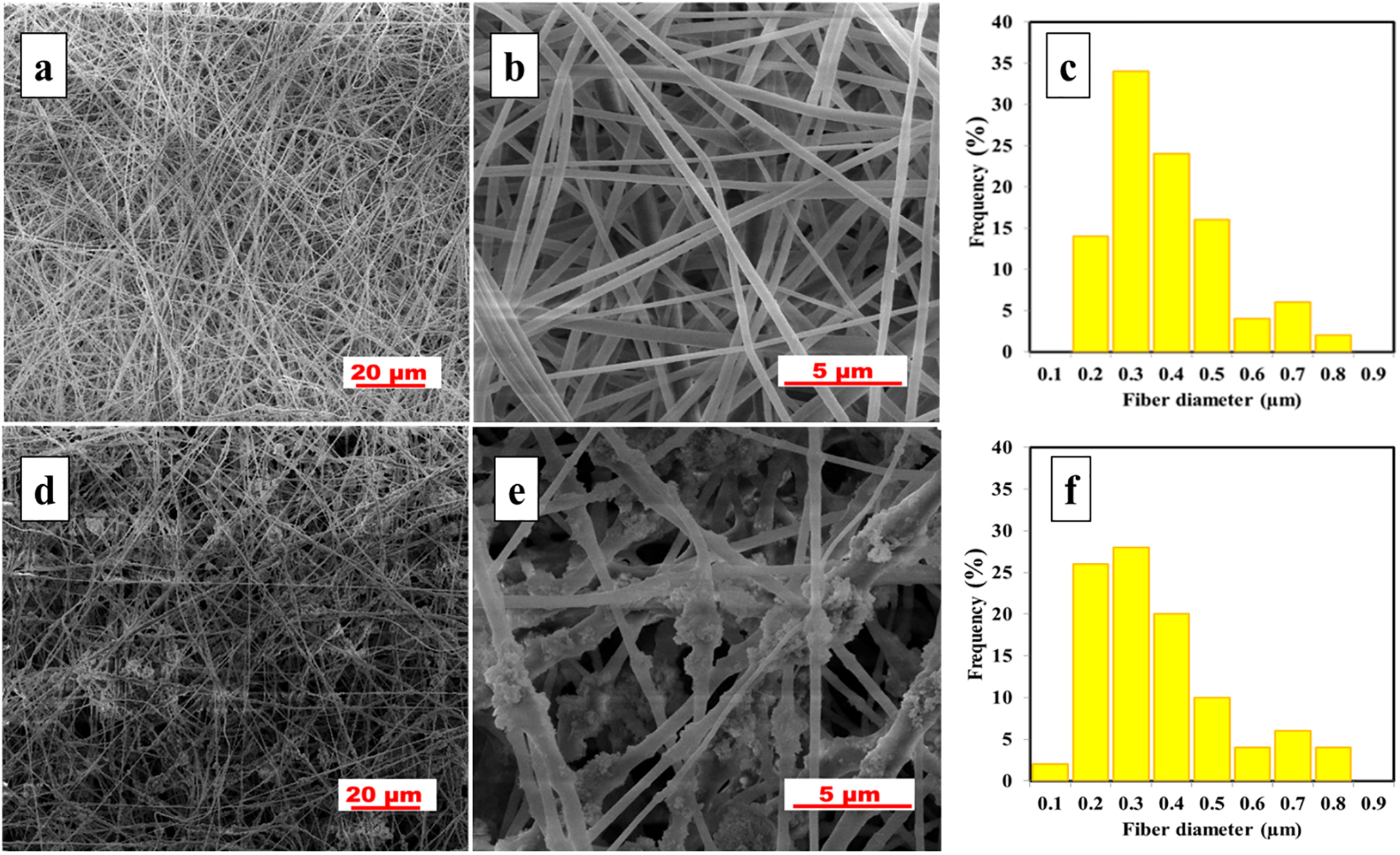

The detailed surface morphology of the pristine and modified composite membranes was investigated using SEM. Fig. 2 displays fiber diameter distribution and SEM images of both membranes at various magnifications. As represented (Fig. 2a,b), the pristine membrane surface has bead-free ultrafine fibers of uniform cylindrical structure. The average fiber diameter obtained for the pristine membrane was 338 ± 139 nm, which is slightly higher than reported in our previous study [21]. On the other hand, the composite membrane displayed rough surface structure due to the deposition of nanoparticles, as represented in Fig. 2d,e. The incorporation of SiO2 nanoparticles resulted in the formation of small localized agglomerates, which increased the overall fiber diameter of the M-PVDF membrane. The agglomeration of nanoparticles within the fibers is attributed to their small size, high concentration and high tendency of agglomeration [32]. When compared to pristine PVDF membrane, the fiber diameter distribution (Fig. 2c,f) of the modified PVDF membrane shifted to smaller sizes and the average fiber diameter was reduced to 308 ± 153 nm; which is likely due to the increase in dope solution conductivity upon addition of nanoparticles.

Figure 2: SEM images of pristine PVDF (a,b) and M-PVDF (d,e) membranes at various magnifications. The histograms images (c,f) illustrate fiber diameter distribution in pristine and modified PVDF membranes, respectively

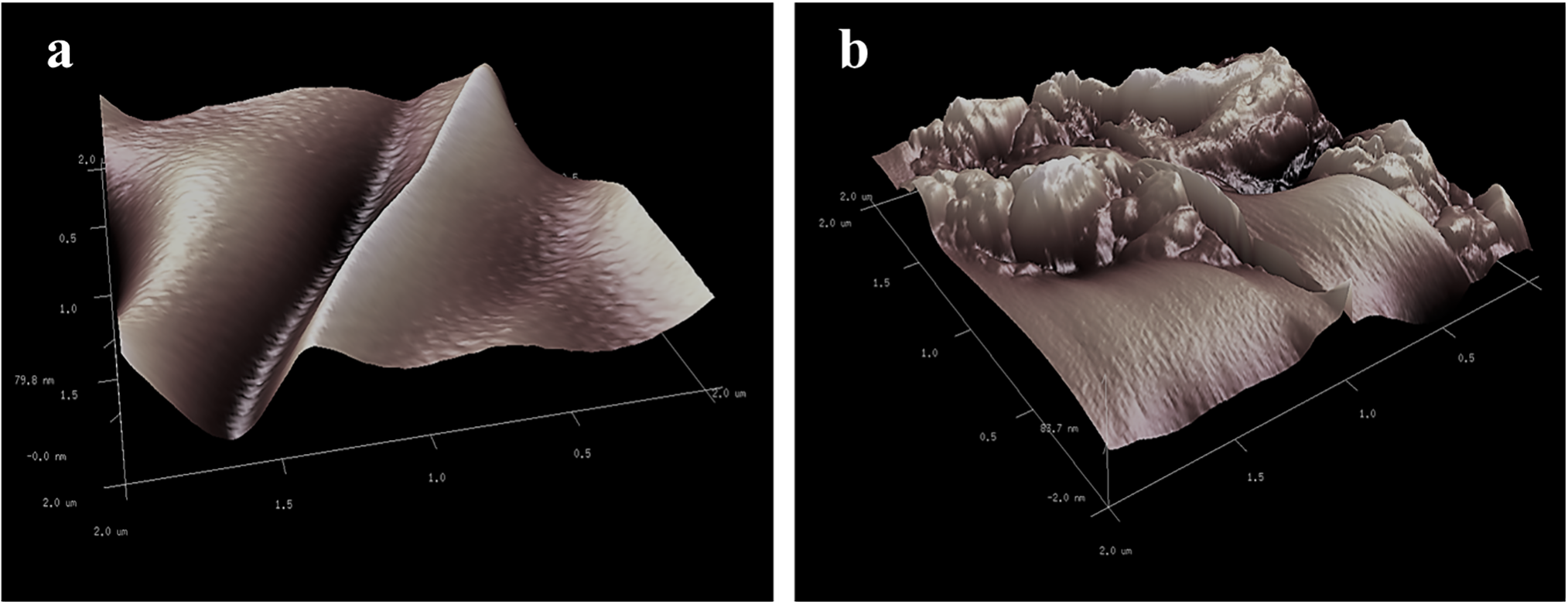

The topology of prepared membranes was also analyzed under AFM, and the 3D images are represented in Fig. 3. The peaks and valleys displayed in the image correspond to the surface roughness. The root means square roughness (Sq) values calculated from these peaks and valleys were 190.6 nm and 224.2 nm for pristine and modified membrane samples, respectively. It can be noticed that the addition of SiO2 nanoparticles increased the surface roughness of the membrane, which has also been reported earlier [33]. Additionally, the agglomerated hydrophobic nanoparticles led to the formation of small beads creating hills and valleys, which contribute to the increased surface roughness [34].

Figure 3: AFM topographic images (2 μm × 2 μm) of (a) pristine membrane and (b) modified PVDF membrane samples

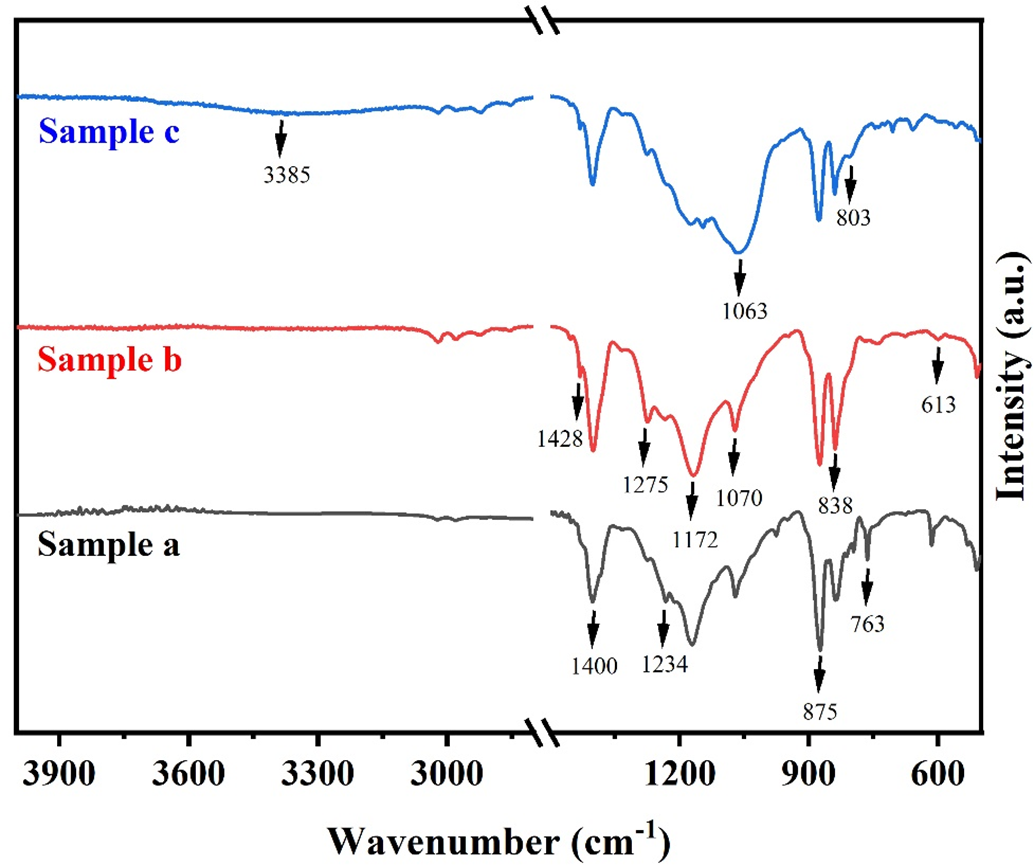

The pristine PVDF, M-PVDF, and C-PVDF membranes were observed using ATR-FTIR and the data collected was examined for the presence of functional groups within each membrane. As indicated in Fig. 4, the absorption bands at 613, 763, 875 and 1070 cm−1 are indicative of α-phase, bands at 838 and 1275 cm−1 are dedicated to β-phase, and bands at 1234 cm−1 is indicative of γ-phase of PVDF [35]. Similarly, the absorption peaks appearing 1172 and 1400 cm−1 are representing combination of α, β, and γ phase [36]. These characteristic peaks of PVDF are seen in all membrane samples, as shown in Fig. 4. The emerging peaks at 803 and 1063 cm−1 within the spectrum of modified PVDF membrane (sample c) are assigned to symmetric and asymmetric Si–O–Si stretching vibration, respectively. These peaks are an indication of the successful incorporation of SiO2 NPs. Further, the peaks appearing at 1148 and 1205 cm−1 are assigned to C–F stretching from the FAS coating onto the membrane (sample c). Moreover, the low intensity broad band appearing between 3175 to 3500 cm−1 signifies the presence of residual –OH bonds post modification. After acid pre-treatment of membranes, the formation of –OH bonds occurs, facilitating active sites for the coating of FAS compound in subsequent modification step [21]. Therefore, it may be inferred from the resultant FTIR spectrum, that the composite PVDF membranes were successfully modified.

Figure 4: FTIR analysis spectra of (Sample a) commercial PVDF membrane, (Sample b) pristine PVDF membrane, and (Sample c) modified PVDF membrane

3.1.2 Membrane Wettability and Liquid Entry Pressure

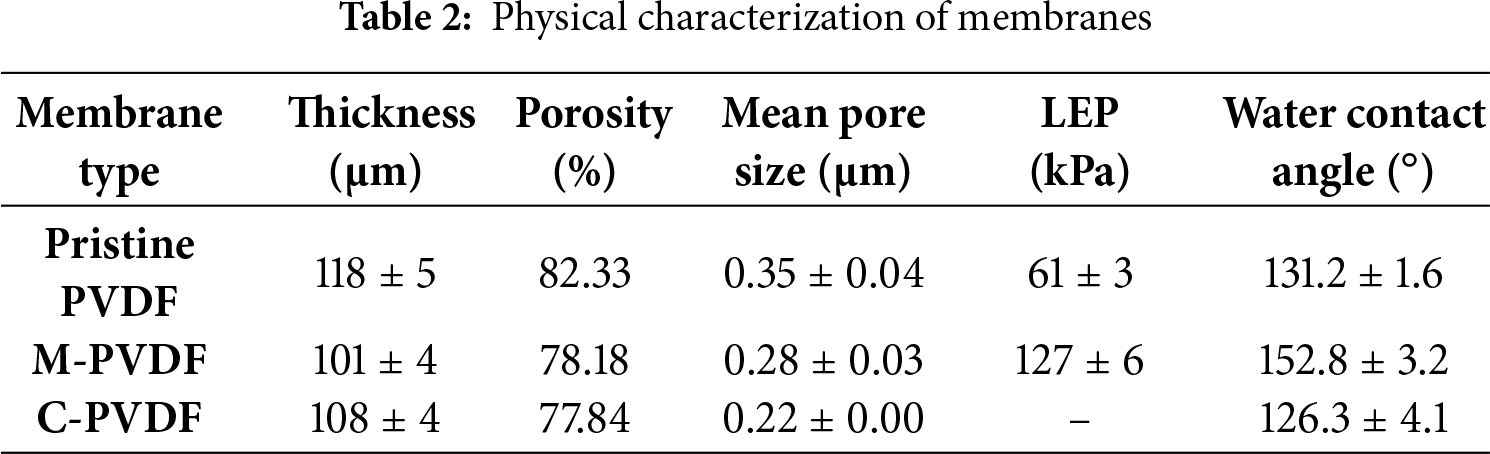

The membrane hydrophobicity or anti-wetting property is a crucial attribute for MD application of the membrane. Increased hydrophobicity improved water repellency and lowers the risk of membrane wetting during long-term operations [22]. Two approaches have been frequently utilized to enhance membrane hydrophobicity: augmenting membrane surface roughness and lowering surface energy. The water contact angle of the electrospun pristine PVDF membrane (131.2 ± 1.6°) was higher than that of the commercial PVDF membrane (126.3 ± 4.1°) prepared by phase inversion. The high WCA of PVDF nanofiber membrane is attributed to the high surface roughness caused by the overlapping of nanofibers in electrospun membranes [25]. The M-PVDF membrane displayed the highest water contact angle of 152.8 ± 3.2°, and therefore exhibited super-hydrophobic property. The increased hydrophobicity of the modified PVDF membrane is credited to two factors: increased surface roughness by SiO2 NPs and reduced surface energy subsequent to the successful bonding of silane compound onto the membrane surface. It is noteworthy that the acid pretreatment during the modification process creates multiple hydroxyl (OH) groups on silica nanoparticles, thereby enhancing their condensation reaction with silane groups during FAS coating [21]. As a result, this process leads to a further increase in water contact angle values of the modified PVDF membrane.

Liquid entry pressure, another pivotal attribute of the membrane, is the pressure above which liquid molecules will penetrate through membrane pores, hence providing the operating pressure limit for the membrane distillation process. Hence, LEP values of the membrane is an important parameter in assessing membrane wetting resistance, separation efficiency, and stability in long-run operations. As per the Young-Laplace equation, the LEP is controlled by the pore size, pore geometry, and hydrophobicity of the membrane [37]. The LEP values obtained for membrane samples are indicated in Table 2. The pristine membrane exhibited LEP values of 61 ± 3 kPa, which increased to 127 ± 6 kPa for M-PVDF membrane. The significant increase in LEP values upon modification is attributed to increased surface hydrophobicity and reduced pore size [38].

3.1.3 Pore Size, Porosity, and Membrane Stability

This section includes the permeability parameters of the membrane, i.e., porosity and pore size distribution. It is crucial for MD membrane applications to have narrow pore-size distribution and high porosity in order to obtain enhanced performance in terms of solute rejection, permeate flux, and membrane wetting [26]. Moreover, the membrane pore size is controlled by multiple factors such as polymer and solution properties, electrospinning operational parameters, and post-processing treatments [23]. While large pore size and high porosity are favorable in achieving higher permeation rates, these attributes concurrently elevate the risk of membrane wetting and reduce membrane rejection efficiency [34]. In the current study, optimal operating conditions were utilized (as mentioned in Section 2.3), rather than specifically examining the effects of solution preparation and operational parameters. Table 2 represents the mean pore size values of the pristine, modified, and commercial membranes as 0.35, 0.28, and 0.22 μm, respectively. The drop in mean pore size of the modified PVDF membrane is associated with two factors: reduced fiber diameter and agglomeration of silica nanoparticles. The porosity or void volume fraction of the membrane is another parameter that impacts the flux performance of the membrane. High porosity results in larger surface area for evaporation or increased number of diffusion channels, thereby enhancing the heat transfer coefficient and reducing heat transfer conduction, ultimately leading to higher permeate flux [34]. It is evident from Table 2 that all membranes used in this study exhibited high porosity levels, i.e., >75%. Moreover, the porosity values for the modified PVDF membrane are lower than that of the pristine PVDF membrane. This disparity can be ascribed to nanoparticle agglomeration at high loading percentage and occupying porous space between the fibers [39].

3.2 Membrane Performance in VMD Process

In the present section, the performance of the fabricated membranes was investigated in terms of permeation flux and rejection and compared with that of the commercial PVDF membrane in a VMD process.

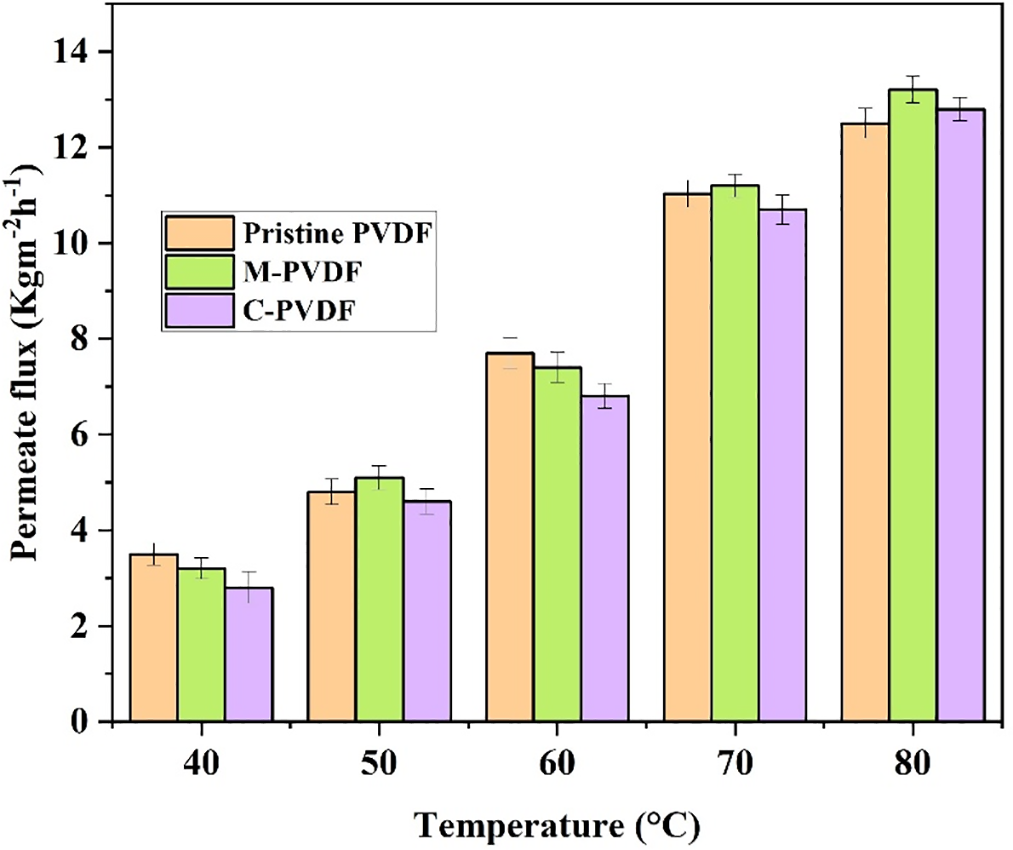

3.2.1 Effect of Feed Temperature

The impact of varying feed temperature on permeate flux and rejection was studied between temperature range 40°C to 80°C in VMD setup. This experimental investigation was conducted using 3.5 wt% salt solution as the feed, while maintaining other operational parameters at constant values, such as a feed flow rate of 120 mL·min−1 and permeate side temperature of 25°C. As represented in Fig. 5, the permeate flux increased exponentially with increasing temperature, irrespective of the type of membrane used. For instance, the permeate flux for M-PVDF membrane surged from 3.2 to 13.2 kg·m−2·h−1, indicating an approximately 312% increase, as the feed solution temperature escalated from 40°C to 80°C. Similarly, an increase of 257% and 357% was observed in the same feed temperature range for pristine and C-PVDF membranes, respectively. These percentage increases are calculated with respect to each membrane’s initial flux at 40°C. The exponential increase in permeate flux is attributed to increased vapor pressure on the feed side with increasing feed temperature. As membrane distillation is a thermally driven process, the feed temperature has a direct effect on vapor pressure on the feed side and hence enhances the membrane driving force and associated permeation flux [40]. In MD process, the relationship between mass flux (J) and transmembrane vapor pressure difference is linear, expressed as:

where C is membrane permeability. pmf and pmp represent the partial vapor pressure on the feed and permeate side that could be evaluated at feed and permeate side temperature, respectively, using the Antoine equation [41,42].

Figure 5: Membrane performance as a function of feed (3.5 wt% NaCl) solution temperature in a VMD test

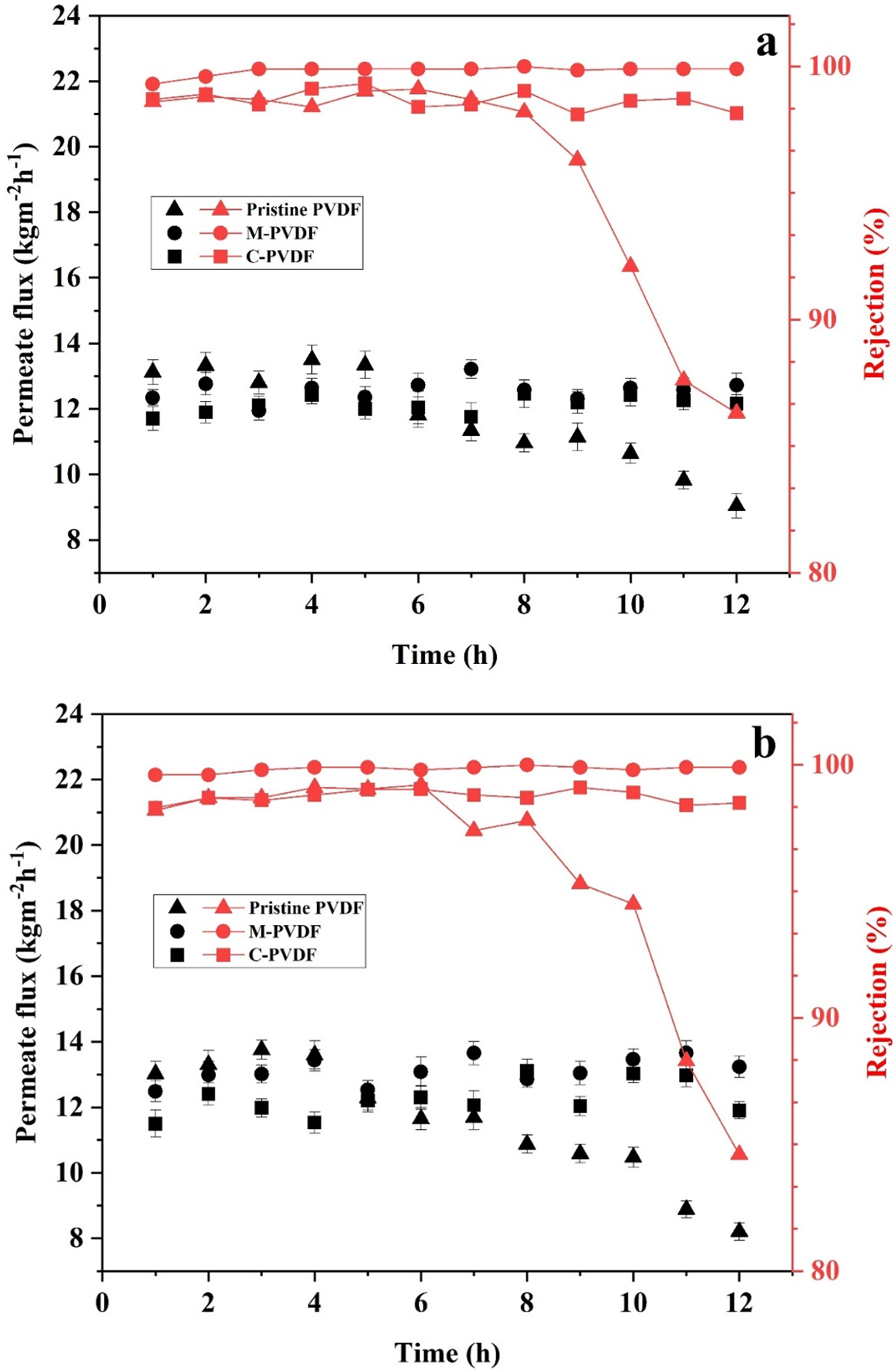

3.2.2 Heavy Metal Decontamination

The heavy metal (Fe and As) removal performance of all membrane samples was assessed using 50 mg·L−1 feed concentration, 70°C feed solution temperature, at fixed flow rate of 120 mL min−1, and vacuum of 6 kPa in a continuous VMD process. The collected permeate was monitored for weight and concentration after each hourly interval. Fig. 6a,b illustrates the trend of permeation flux and rejection rates over time for arsenic and iron feed solutions, respectively. The initial hours of operation showed consistent permeate flux trends for all membranes and both types of feed solutions, indicating that the electrospun membranes were capable of producing stable flux and rejection during continuous MD operation. Also, the permeation fluxes of electrospun membranes (pristine and modified PVDF) were better than those of commercial membranes, likely due to the distinctive characteristics of the electrospun membranes, such as interconnected pore structure and high porosity. Fig. 6a illustrates that while using arsenic-contaminated feed solution, the initial water permeate flux of the superhydrophobic modified PVDF membrane was 12.34 kg·m−2·h−1, slightly lower than the permeate flux 13.12 kg·m−2·h−1, displayed by the pristine membrane, a consequence attributed to the reduced porosity and pore size in the modified PVDF membrane. However, the M-PVDF membranes containing SiO2 exhibited stable permeate flux of approximately 12.7 kg·m−2·h−1 and rejection of 99.9% throughout the process, which illustrates that solely water vapors passed through the membrane, while the nonvolatile solutes were rejected. The permeate flux of the pristine membrane depleted after 5 to 6 h of operation due to insufficient hydrophobicity and bigger mean pore size. Apart from reducing flux, the obvious depletion in solute rejection from ~99% to 86.3% was also observed in pristine PVDF membrane within 12 h of VMD operation. The observed decline in flux and rejection rate observed for the pristine PVDF membrane can be attributed to its lower hydrophobicity and larger pore size, which likely allowed partial penetration of the feed solution into the pores, hindering vapor transport from the feed to the permeate side. The pristine membrane (having 131.2° WCA and 0.35 μm mean pore size) possesses weaker water repellence compared to the modified M-PVDF membrane (having 152.8° WCA and 0.28 μm mean pore size). This structural difference explains the reduced flux and solute rejection in the pristine membrane during prolonged operation. Similar behavior has also been reported in our previous work [21]. Moreover, benefitting from lower mean pore size and sufficient hydrophobicity, the C-PVDF membrane produced consistent permeate flux and effectively rejected solutes (up to 99%) during long run MD operation, despite experiencing low water production rates of approximately 12 kg·m−2·h−1. Similarly, as represented in Fig. 6b, when iron-contaminated water was used as feed, the pristine PVDF membrane produced highest initial flux of 13.5 kg·m−2·h−1, which eventually reduced to 8.2 kg·m−2·h−1 within 12 h of operation. The M-PVDF membrane maintained stable flux of approximately 13.2 kg·m−2·h−1, without any drop in flux or rejection, which indicates that the membrane has not been subjected to fouling during the long run operation. Moreover, the C-PVDF membrane performed effectively, producing steady permeate flux of 12 kg·m−2·h−1 and solute rejection of approximately 98.5%. The water permeates collected during VMD test of M-PVDF membrane was also analyzed for silica to ensure no leaching of SiO2 nanoparticles occurred during the operation. Furthermore, membrane stability was verified by no loss of membrane weight on stirring M-PVDF sample for 24 h in distilled water. The ICP-MS analysis of the leaching solution indicated no detectable amount of silica, hence assuring the structural stability of the modified PVDF membrane. Although C-PVDF and M-PVDF showed comparable flux and rejection, the modification process enhanced surface hydrophobicity, fouling resistance, and long-term operational stability of the modified membrane.

Figure 6: Permeate flux and rejection percentage of pristine PVDF, M-PVDF, and C-PVDF membrane samples during continuous VMD operation for removal of (a) arsenic and (b) iron

Furthermore, synthetic heavy metal solution containing other metal ions (Na+, Ca2+, K+, and Mg2+), was used as feed to evaluate the MD performance of the optimized M-PVDF membrane in the presence of other ions (Fig. 7). This test was conducted under identical operational conditions, with a fixed flow rate of 120 mL·min−1, a feed solution temperature of 70°C, and a vacuum of 6 kPa. The feed concentration of each metal ion (Na+, Ca2+, K+, and Mg2+) was maintained at 100 mg·L−1 and that of arsenic or iron was kept at 50 mg·L−1. The permeate was collected for metal ion analysis after few hours of continuous operation, and examined under ICP-MS technique. As is evident, the M-PVDF membrane produced stable flux while maintaining high rejection, showcasing high potential in inorganic heavy metals removal from a high concentration feed during long-term operation without compromising the permeate flux.

Figure 7: Rejection percentage of various metal ions while using (a) arsenic feed solution and (b) iron feed solution during VMD operation using modified PVDF membrane

Recent global policies have begun restricting the use of fluorinated materials because of their persistence in the environment. For instance, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) has proposed broad limits on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has issued new guidance on PFAS emissions and disposal. As PVDF is a partially fluorinated polymer, such regulations may affect its large-scale use in future water treatment systems. To address this, future work could focus on recycling or recovery of PVDF membranes, using reduced-fluorine coatings, or developing fluorine-free alternatives that offer comparable hydrophobicity and stability.

The current work uniquely demonstrates the stable long-term performance of hierarchically structured SiO2-PVDF nanofibrous membranes for the removal of arsenic and iron from aqueous solutions under VMD operation. These membranes were prepared by incorporating silica nanoparticles within PVDF polymer dope solution, which was then run through the electrospinning process. The resultant membranes were modified by following a two-step modification approach to impart surface superhydrophobicity to the membranes. The optimized modified membranes (M-PVDF) showed high rejection for both metal ions (Fe and As), rendering them suitable for the treatment of drinking water, where the iron and arsenic contamination levels surpass the permissible limits. Moreover, the fundamental characteristics of modified membranes, such as roughness, permeability, and wettability, were evaluated and compared to those of pristine and commercial membranes. The results demonstrate that post-modification, the values of water contact angle and liquid entry pressure significantly improved by 21.6° and 66 kPa, respectively. Moreover, during the long run VMD operation, the modified membrane achieved stable permeate flux of 12.7 kg·m−2·h−1 and 13.2 kg·m−2·h−1 for arsenic and iron aqueous solutions, respectively, while maintaining significantly high rejection for both metal ions. As a result, these findings can provide a foundation for future research and implementation of the membrane distillation process for heavy metals removal.

Acknowledgement: The author (Pooja Yadav) is grateful to Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi and Ministry of Human Resource and Development (MHRD), Government of India, New Delhi for providing research fellowship.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Pooja Yadav: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition; Ramin Farnood: supervision, resources, writing—review and editing; Vivek Kumar: project administration, supervision, resources, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Patra S, Ghosh PK. Assessing severity in groundwater contamination by arsenic, iron and manganese and deciphering its heterogeneity in a sub-tropical monsoon region. Environ Pollut. 2025;375(1):126325. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2025.126325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sultan MW, Qureshi F, Ahmed S, Kamyab H, Rajendran S, Ibrahim H, et al. A comprehensive review on arsenic contamination in groundwater: sources, detection, mitigation strategies and cost analysis. Environ Res. 2025;265(16):120457. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2024.120457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Sharma GK, Jena RK, Ray P, Yadav KK, Moharana PC, Cabral-Pinto MMS, et al. Evaluating the geochemistry of groundwater contamination with iron and manganese and probabilistic human health risk assessment in endemic areas of the world’s largest River Island. India Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2021;87(6):103690. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2021.103690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tiwari R, Satwik S, Khare P, Rai S. Arsenic contamination in India: causes, effects and treatment methods. Int J Eng Sci Tech. 2021;13(1):146–52. doi:10.4314/ijest.v13i1.22s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kumar M, Goswami R, Patel AK, Srivastava M, Das N. Scenario, perspectives and mechanism of arsenic and fluoride co-occurrence in the groundwater: a review. Chemosphere. 2020;249(2):126126. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hashemi SA, Mousavi SM, Ramakrishna S. Effective removal of mercury, arsenic and lead from aqueous media using Polyaniline-Fe3O4-silver diethyldithiocarbamate nanostructures. J Clean Prod. 2019;239(4):118023. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nazaripour M, Reshadi MAM, Ahmad Mirbagheri S, Nazaripour M, Bazargan A. Research trends of heavy metal removal from aqueous environments. J Environ Manag. 2021;287:112322. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yadav P, Farnood R, Kumar V. HMO-incorporated electrospun nanofiber recyclable membranes: characterization and adsorptive performance for Pb(II) and As(V). J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9(6):106507. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2021.106507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Khatri N, Tyagi S, Rawtani D. Recent strategies for the removal of iron from water: a review. J Water Process Eng. 2017;19(5):291–304. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2017.08.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hossain MA, Haque MI, Parvin MA, Islam MN. Evaluation of iron contamination in groundwater with its associated health risk and potentially suitable depth analysis in Kushtia Sadar Upazila of Bangladesh. Groundw Sustain Dev. 2023;21(2):100946. doi:10.1016/j.gsd.2023.100946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Narayanan MSS, Pitchaimani VS, Sivakumar M, Dinesh Kumar T, Abishek SR, Karuppannan S. Spatial assessment of heavy metal contamination in groundwater in the Kadaladi region, Tamil Nadu. India Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):27704. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-12120-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Aijaz MO, Karim MR, Omar NMA, Othman MHD, Wahab MA, Akhtar Uzzaman M, et al. Recent progress, challenges, and opportunities of membrane distillation for heavy metals removal. Chem Rec. 2022;22(7):e202100323. doi:10.1002/tcr.202100323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Shaheen A, AlBadi S, Zhuman B, Taher H, Banat F, AlMarzooqi F. Photothermal air gap membrane distillation for the removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater. Chem Eng J. 2022;431(2):133909. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.133909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Niknejad AS, Bazgir S, Sadeghzadeh A, Shirazi MMA. Evaluation of a novel and highly hydrophobic acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene membrane for direct contact membrane distillation: electroblowing/air-assisted electrospraying techniques. Desalination. 2021;500:114893. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2020.114893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kebria MRS, Rahimpour A, Salestan SK, Seyedpour SF, Jafari A, Banisheykholeslami F, et al. Hyper-branched dendritic structure modified PVDF electrospun membranes for air gap membrane distillation. Desalination. 2020;479:114307. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2019.114307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Woo YC, Yao M, Shim WG, Kim Y, Tijing LD, Jung B, et al. Co-axially electrospun superhydrophobic nanofiber membranes with 3D-hierarchically structured surface for desalination by long-term membrane distillation. J Membr Sci. 2021;623:119028. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2020.119028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Razmgar K, Saljoughi E, Mousavi SM. Preparation and characterization of a novel hydrophilic PVDF/PVA/Al2O3 nanocomposite membrane for removal of As(V) from aqueous solutions. Polym Compos. 2019;40(6):2452–61. doi:10.1002/pc.25115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rowley J, Abu-Zahra NH. Synthesis and characterization of polyethersulfone membranes impregnated with (3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane) APTES-Fe3O4 nanoparticles for As(V) removal from water. J Environ Chem Eng. 2019;7(1):102875. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2018.102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shaulsky E, Nejati S, Boo C, Perreault F, Osuji CO, Elimelech M. Post-fabrication modification of electrospun nanofiber mats with polymer coating for membrane distillation applications. J Membr Sci. 2017;530:158–65. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2017.02.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Seyed Shahabadi SM, Rabiee H, Seyedi SM, Mokhtare A, Brant JA. Superhydrophobic dual layer functionalized titanium dioxide/polyvinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene (TiO2/PH) nanofibrous membrane for high flux membrane distillation. J Membr Sci. 2017;537:140–50. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2017.05.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yadav P, Farnood R, Kumar V. Superhydrophobic modification of electrospun nanofibrous Si@PVDF membranes for desalination application in vacuum membrane distillation. Chemosphere. 2022;287:132092. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Li B, Yun Y, Wang M, Li C, Yang W, Li J, et al. Superhydrophobic polymer membrane coated by mineralized β-FeOOH nanorods for direct contact membrane distillation. Desalination. 2021;500:114889. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2020.114889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pan CY, Xu GR, Xu K, Zhao HL, Wu YQ, Su HC, et al. Electrospun nanofibrous membranes in membrane distillation: recent developments and future perspectives. Sep Purif Technol. 2019;221:44–63. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2019.03.080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Attia H, Alexander S, Wright CJ, Hilal N. Superhydrophobic electrospun membrane for heavy metals removal by air gap membrane distillation (AGMD). Desalination. 2017;420:318–29. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2017.07.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Attia H, Johnson DJ, Wright CJ, Hilal N. Robust superhydrophobic electrospun membrane fabricated by combination of electrospinning and electrospraying techniques for air gap membrane distillation. Desalination. 2018;446:70–82. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2018.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Khraisheh M, AlMomani F, Al-Ghouti M. Electrospun Al2O3 hydrophobic functionalized membranes for heavy metal recovery using direct contact membrane distillation. Int J Energy Res. 2021;45(6):8151–67. doi:10.1002/er.5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Attia H, Johnson DJ, Wright CJ, Hilal N. Comparison between dual-layer (superhydrophobic–hydrophobic) and single superhydrophobic layer electrospun membranes for heavy metal recovery by air-gap membrane distillation. Desalination. 2018;439:31–45. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2018.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Pal P, Manna AK. Removal of arsenic from contaminated groundwater by solar-driven membrane distillation using three different commercial membranes. Water Res. 2010;44(19):5750–60. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2010.05.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Moradi R, Monfared SM, Amini Y, Dastbaz A. Vacuum enhanced membrane distillation for trace contaminant removal of heavy metals from water by electrospun PVDF/TiO2 hybrid membranes. Korean J Chem Eng. 2016;33(7):2160–8. doi:10.1007/s11814-016-0081-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Alkhudhiri A, Hakami M, Zacharof MP, Abu Homod H, Alsadun A. Mercury, arsenic and lead removal by air gap membrane distillation: experimental study. Water. 2020;12(6):1574. doi:10.3390/w12061574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Qu D, Wang J, Hou D, Luan Z, Fan B, Zhao C. Experimental study of arsenic removal by direct contact membrane distillation. J Hazard Mater. 2009;163(2–3):874–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.07.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Anis SF, Singaravel G, Hashaikeh R. Hierarchical nano zeolite-Y hydrocracking composite fibers with highly efficient hydrocracking capability. RSC Adv. 2018;8(30):16703–15. doi:10.1039/c8ra02662a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Gupta I, Chakraborty J, Roy S, Farinas ET, Mitra S. Nanocarbon immobilized membranes for generating bacteria and endotoxin free water via membrane distillation. Sep Purif Technol. 2021;259:118133. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2020.118133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lee E, Kyoungjin A, Hadi P, Lee S, Chul Y. Advanced multi-nozzle electrospun functionalized titanium dioxide/polyvinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene (TiO2/PVDF-HFP) composite membranes for direct contact membrane distillation. J Membr Sci. 2016;524:712–20. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2016.11.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ke G, Jin X, Hu H. Electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride/polyacrylonitrile composite fibers: fabrication and characterization. Iran Polym J. 2020;29(1):37–46. doi:10.1007/s13726-019-00773-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kaspar P, Sobola D, Částková K, Knápek A, Burda D, Orudzhev F, et al. Characterization of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) electrospun fibers doped by carbon flakes. Polymers. 2020;12(12):2766. doi:10.3390/polym12122766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Qasim M, Samad IU, Darwish NA, Hilal N. Comprehensive review of membrane design and synthesis for membrane distillation. Desalination. 2021;518:115168. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2021.115168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Li Z, Liu Y, Yan J, Wang K, Xie B, Hu Y, et al. Electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride/fluorinated acrylate copolymer tree-like nanofiber membrane with high flux and salt rejection ratio for direct contact membrane distillation. Desalination. 2019;466:68–76. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2019.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Deng L, Liu K, Li P, Sun D, Ding S, Wang X, et al. Engineering construction of robust superhydrophobic two-tier composite membrane with interlocked structure for membrane distillation. J Membr Sci. 2020;598:117813. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2020.117813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Attia H, Osman MS, Johnson DJ, Wright C, Hilal N. Modelling of air gap membrane distillation and its application in heavy metals removal. Desalination. 2017;424:27–36. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2017.09.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Qtaishat M, Matsuura T, Kruczek B, Khayet M. Heat and mass transfer analysis in direct contact membrane distillation. Desalination. 2008;219(1–3):272–92. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2007.05.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chiam CK, Sarbatly R. Vacuum membrane distillation processes for aqueous solution treatment—a review. Chem Eng Process Process Intensif. 2013;74:27–54. doi:10.1016/j.cep.2013.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools