Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Polystyrene-Grafted Molybdenum Disulfide Filled Polypropylene Composites for Enhanced Laser Marking Performance

1 Nuclear Power Operation Management Co., Ltd., CNNC, Haiyan, 314300, China

2 Key Laboratory of Environmental Friendly Polymer Materials, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Changzhou University, Changzhou, 213164, China

* Corresponding Author: Zheng Cao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Modification Methods for Polymers)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 1125-1141. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.073300

Received 15 September 2025; Accepted 25 November 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

Polypropylene (PP) has low inherent susceptibility to common industrial lasers, which poses a significant challenge for laser-based marking. To improve the laser sensitivity of PP, molybdenum disulfide grafted with polystyrene (MoS2-g-PS) was synthesized via in-situ free radical polymerization and used as a laser-sensitive filler for PP composites prepared by melt blending. The composites were then marked with a 1064 nm semiconductor laser, producing clear and legible patterns. The marked surfaces were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), colorimetry, Raman spectroscopy, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). The results demonstrate that the PP/MoS2-g-PS composites exhibit significantly improved laser markability compared to both pure PP and PP/MoS2 composites, yielding superior marking quality. When the MoS2-g-PS content was 0.02 wt% and the laser current intensity was 11 A, a clearly recognizable QR code pattern was obtained with high resolution and legibility. The mechanism of laser-induced marking on the PP/MoS2-g-PS composites involves efficient absorption of near-infrared (NIR) laser energy and photothermal conversion by the MoS2 core, while the surrounding PS layer carbonizes upon laser irradiation. The synergistic effect between MoS2 and PS effectively enhance the laser marking performance of PP.Keywords

Conventional printing technologies face significant limitations in modern industry. Identifiers on goods are frequently rendered illegible during storage and handling due to mechanical abrasion, friction, or chemical exposure. Furthermore, these conventional methods are often ineffective for application on curved or textured surfaces [1,2]. Laser marking, a product of contemporary high-tech laser technology, effectively overcomes these shortcomings due to its inherent advantages. It has consequently established itself as a leading emerging printing and marking technology. This technique exploits the principle of inducing physical and chemical modifications in polymer materials by irradiating them with laser light of specific wavelengths and energies. The technology offers key advantages, including high efficiency, superior mark quality, ease of automation, low operating costs, and environmental benefits due to its ink-free, volatile-free process. Recent rapid advancements have propelled its adoption across numerous sectors like food packaging, automotive, and electronics for applications ranging from marking medical devices and electronic chips to anti-counterfeiting labels on automotive parts. Consequently, deepening the understanding of laser-polymer interaction mechanisms and to enhance material response for high-contrast, high-definition markings is of great importance [3–5].

The laser labeling of polymeric materials is greatly influenced by both polymer chain structure and laser processing conditions. Polymers such as acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene copolymer (ABS) [6], polycarbonate (PC) [7], and polystyrene (PS) [8] exhibit a strong response to NIR lasers at 1064 nm. Due to their high residual carbon content and tendency to carbonize readily at high temperatures, these materials can be marked directly via laser irradiation. In contrast, other polymers—including polyolefins like polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE), as well as polyamide (PA) and thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU)—exhibit poor laser absorption and performance [9]. For these materials, clear, high-contrast markings with strong machine readability cannot be achieved by laser surface treatment alone. Typically, the treated surfaces yield poor-quality, single-colour patterns that fall short of high-contrast, high-definition requirements—especially for machine-readable features such as graphics and QR codes. Although raising laser power or extending exposure time can produce polyolefin surfaces with adequate contrast, these measures typically impair clarity and overall quality while increasing process cost and compromising commercial viability. Therefore, physical and chemical modification strategies are employed to enhance the laser-marking ability of polyolefin polymers. The two principal approaches are incorporation of laser-sensitive additives into the polymer matrix and development of inherently laser-markable polymer formulations. The incorporation of laser marking additives, such as mica [10], iron oxide (Fe3O4) [11], carbon nanotubes [12], antimony trioxide (Sb2O3) [13], bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) [14], and titanium dioxide (TiO2) [15]—enhances the laser marking ability of polymer materials. These additives efficiently absorb laser energy and induce localized physical or chemical changes—such as foaming, engraving, or color change—in the polymer matrix. The result is high-contrast markings with sharp outlines, long-term stability, and excellent machine readability. In contrast, inherently laser-markable polymers such as polycarbonate (PC), polyphenylene ether (PPO), and polyimide (PI) contain up to 20–50 wt% carbon residue at 800°C, which enables direct carbonization and contrast formation under laser irradiation without additives [16,17].

Polypropylene (PP) is a commodity plastic valued for its low density, high transparency, superior mechanical and processability performance, and resistance to acids, alkalis, and organic solvents. These attributes render it suitable for diverse applications in the automotive, appliance, machinery, and packaging sectors [18]. The widespread use of PP products necessitates durable surface markings such as QR codes, logos, and identification numbers. However, the material’s inherent smoothness and low surface energy hinder the effective adhesion of traditional inks, producing markings that are readily abraded and lack durability [19]. Consequently, laser etching is considered a promising route for marking PP, but its inherently weak laser-energy absorption and absence of laser-responsive moieties continue to hinder the achievement of high-quality marks. Previous studies have focused on addressing this issue. Liu et al. synthesized a laser-sensitive polystyrene-grafted antimony trioxide additive (Sb2O3-g-PS). Compared to unmodified Sb2O3, the PS shell readily carbonizes and turns black under laser irradiation, more effectively enhancing the laser marking contrast and quality on PP [20]. Nevertheless, intensive research is still required to improve the near-infrared (NIR) laser response of PP composites to achieve high-definition, high-contrast markings.

Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2), a two-dimensional material, exhibits significant potential for applications in fields such as energy storage, electrochemistry, microwave absorption, and electromagnetic shielding [21]. This promise stems from its unique layered structure, which confers a range of advantageous properties: excellent electrical conductivity, a high specific surface area, and robust mechanical strength. MoS2 is a lustrous black-grey powder with a tunable band gap, broad absorption bandwidth and outstanding photoelectric performance. It also exhibits excellent chemical and thermal stability, being insoluble in water and dilute acids and generally inert to metals and metal oxides [22]. MoS2 retains effective lubrication under extreme conditions—high or low temperature, high load, high speed, chemical corrosion and ultra-high vacuum—thereby extending service intervals, cutting operating costs and improving working environments. It is also used as a release agent for non-ferrous metals and as a forging lubricant. In recent years MoS2, a prototypical two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenide, has become a focal material in emerging-materials research owing to its unique physicochemical properties. Its applications span diverse fields such as electrochemistry [23], sensing [24], medicine [25], photocatalysis [26], and ion storage [27,28]. Furthermore, MoS2 shows significant promise for use in energy storage systems and microwave-absorbing materials and devices [29–31].

In our previous work, it is found that the laser markability of PP can be effectively improved when the amount of Sb2O3-g-PS reaches 2 wt% [32]. In this work, MoS2 was functionalized with PS via free radical polymerization, yielding MoS2-g-PS laser-sensitive particles. Finally, PP/MoS2-g-PS composites were fabricated via melt blending, their laser marking performance was systematically investigated under different laser currents, and the underlying marking mechanism was elucidated. Compared with Sb2O3, the grafting of PS alleviates the agglomeration of MoS2, and the specific surface area can further reach to dozens or even hundreds of times that of Sb2O3 by lamellar sliding during melt blends. Therefore, MoS2 with higher specific surface area can effectively absorb energy and induce the carbonization of PS and PP around it, producing excellent markability under a significantly lower addition. This work provides a viable solution for achieving high-quality laser marking on polypropylene products in applications such as automobiles, medical devices, and precision instruments.

PP (GM1600E, MFR = 16 g/10 min) was purchased from Sinopec Shanghai Petrochemical Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Styrene (St, AR) and polyvinyl pyrroliketone (PVPK30, Mw = 40,000 g/mol) was supplied from Aladdin Reagent Co., Ltd. MoS2 (1T phase, 1.5 μm, XF184-1) was bought from Nanjing Xianfeng Nano Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). 3-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (KH570) (>98%) was bought from Nanjing Chuangshi Chemical Aid Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Ethanol (AR) and tetrahydrofuran (THF, AR) were received from Shanghai Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

An ethanol–water mixture (pH 5.5, adjusted with acetic acid) was prepared, and KH570 (2 wt%) was added and hydrolysed for 1.5 h. MoS2 powder was introduced and the suspension reacted at 85°C for 2 h under vigorous stirring. After cooling, the solid was filtered, washed with ethanol, and dried to give KH570-modified MoS2 (MoS2-KH570). The modified MoS2-KH570 (2 g) and PVP (3 g) were dispersed in ethanol (150 mL) by 15 min sonication, transferred to a 250 mL three-neck flask, and heated to 75°C under nitrogen. A styrene/AIBN (5/0.025 g) solution was added dropwise, and the polymerization was proceeded for 20 h. The product was collected, washed sequentially with ethanol (3 × 100 mL, to remove excess PVP) and THF (3 × 100 mL, to extract free PS), and dried. Gentle grinding afforded MoS2-g-PS particles.

2.3 Preparation of the PP/MoS2-g-PS Composites

The MoS2 and MoS2-g-PS particles were melt-blended with PP using an internal mixer (Su-70, Changzhou Suyan Technology Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China) at 30 rpm and 180°C. The resulting composites were then compression-molded into sheets using a plate vulcanizer (YF-8017, Yangzhou Yuanfeng Experimental Machinery Factory, Yangzhou, China) with both the upper and lower plates set to 180°C. The mass contents of MoS2 and MoS2-g-PS are both 0.02%.

The prepared PP, PP/MoS2, and PP/MoS2-g-PS composite samples were molded into pieces for laser marking. The marking was performed using a pulsed Nd:YAG laser marking machine (KDD-50, Changzhou Kaitai Laser Technology Co., Ltd., Changzhou, China) operating at a wavelength of 1064 nm. The laser processing parameters were set as follows: a focal length of 220 mm, a spot size of 40 μm, a pulse repetition frequency of 4 kHz, a marking current of 11 A, a dot diameter of 0.2 mm and a linear scanning speed of 800 mm/s.

2.5 Instrumentation and Characterization

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was performed using a Nicolet iS50R spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The infrared spectra of the MoS2, MoS2-KH570 and MoS2-g-PS samples were acquired in reflectance mode. The spectral range was set from 500 to 4000 cm−1.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a 209 F3 thermal analyzer (Netzsch, Selb, Germany). The powder samples were tested under a nitrogen atmosphere with a flow rate of 20 mL/min. The temperature was ramped from 50°C to 800°C at a heating rate of 20°C/min.

The original camera was used to capture and record the macroscopic morphology changes of the sample surface of each orthogonal test group. The chromatic difference test was calibrated with a black and white standard sample (7000 A, X-Rite, Grand Rapids, MI, USA), and then the sample was tested for contrast of light and shade. The unlabeled area and the substrate surface laser labeled area (15 × 15 mm) as the standard and contrast sample, respectively. The corresponding ΔL were recorded and analyzed.

Raman spectroscopy was performed on the laser-marked patterns of the pure PP and PP/MoS2-g-PS composite samples using a DXR 2 Raman spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

The morphology of the MoS2 particles, both before and after surface coating, was examined using a JEM-2100F transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL, Akishima, Japan) operated at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV.

The laser-irradiated region of 1 mm × 1 mm was excised and cryofractured in liquid nitrogen to expose the internal morphology. The fractured surface was then sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold for 60 s using a Smart Coater to enhance conductivity. The cross-sectional morphology of the composite was subsequently observed on a JSM-6360LA scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL, Akishima, Japan) with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV.

The surface wettability of the PP, PP/MoS2, and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites was evaluated by measuring the water contact angle before and after laser marking. The measurements were conducted using a Power EAcH dynamic contact angle analyzer (Shanghai Zhongchen Digital Technology Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). For consistency, the static contact angle recorded at 1 s after the water droplet made contact with the surface was used for analysis.

The tensile properties of the PP, PP/MoS2, and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites were evaluated using a WDT-30 universal testing machine (Shenzhen Kaiqiangli Experimental Instrument Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). Standard dumbbell-shaped specimens were prepared from the compression-molded sheets using a die-cutting machine. The dimensions of the narrow section of the dumbbell specimens were 20 mm in length, 4 mm in width, and 2 mm in thickness. Tensile tests were performed at a crosshead speed of 20 mm/min with an initial gauge length of 20 mm.

The surface electrical resistance of the PP, PP/MoS2 and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites both before and after laser marking was measured using a FT-3110 four-point probe meter (Ningbo Ruike Micro Intelligent Technology Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China) in accordance with the Chinese national standard GBT 1410-2006.

3.1 Surface Grafting of MoS2 with PS

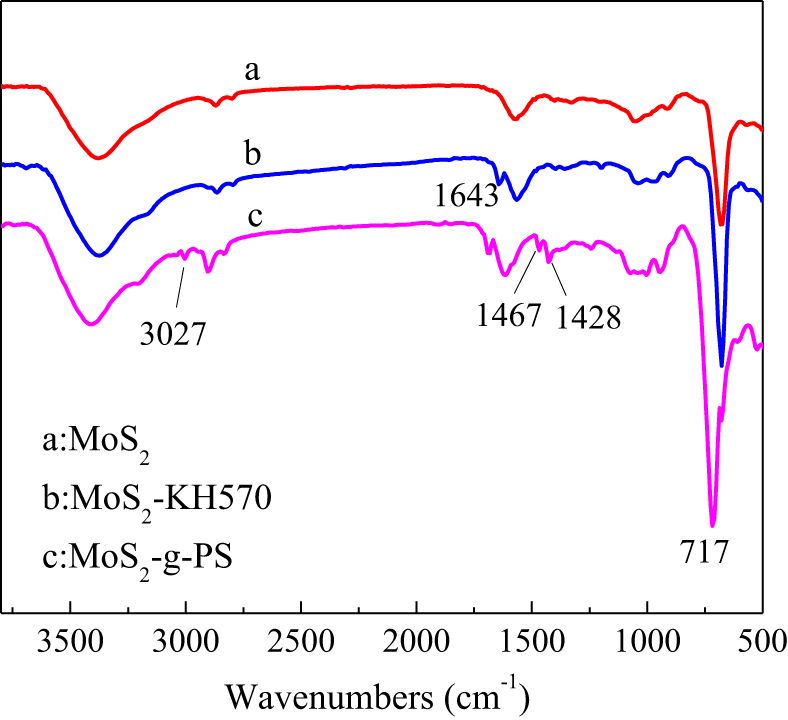

Fig. 1 presents the FT-IR spectra of MoS2 before and after modification. The silane coupling agent KH-570 contains alkoxy groups and carbon-carbon double bonds (C=C), which facilitates its grafting onto the MoS2 surface. In spectrum of MoS2-KH-570, the appearance of an absorption peak at 1643 cm−¹, attributed to the C=C stretching vibration, indicates the successful grafting of KH-570 through the undergo hydrolysis and condensation of alkoxy groups with hydroxyl groups on the MoS2 surface [33]. Subsequently, upon addition of the St monomer, the C=C bonds on the KH-570-modified MoS2 surface undergo free radical polymerization with the C=C bonds in St, resulting in the formation of MoS2-g-PS. The peaks observed at 3027 (aromatic C-H stretch), 1459 and 1490 (benzene ring skeletal vibrations), and 700 cm−¹ (aromatic C-H out-of-plane bending vibration) are all characteristic of PS [34]. These findings confirm the successful grafting of PS onto the MoS2 surface.

Figure 1: FT-IR spectra of MoS2, MoS2-KH570 and MoS2-g-PS

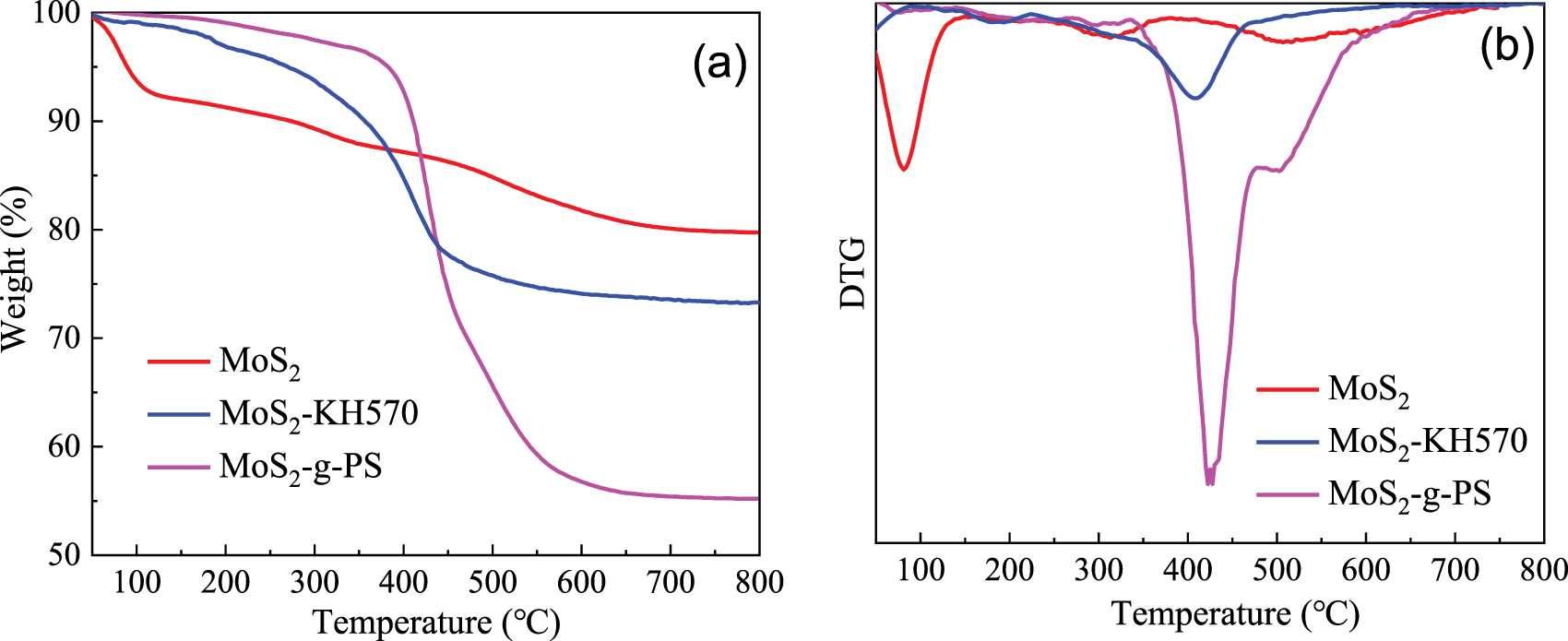

Fig. 2 shows the TGA and DTG curves of MoS2, MoS2-KH570 and MoS2-g-PS. In Fig. 2a, the TGA curve of pure MoS2 shows a slight mass below 100°C, which is attributed to the evaporation of physically adsorbed water. Above 120°C, MoS2 exhibits high thermal stability, with only a gradual mass loss observed upon further heating, and the final weight loss ratio is 20.3% [35]. This gradual loss is likely due to the collapse of the layered structure and the release of interlayer species at elevated temperatures. After grafting KH570, the weight loss ratio of MoS2-KH570 decreases obviously before 100°C, which is because KH570 improved the hydrophobicity of MoS2 surface. Meanwhile, the obvious weight loss in the range of 300°C–450°C corresponds to the decomposition of grafted KH570, resulting in the final weight loss ratio increasing to 26.8%. Subsequently, the MoS2-g-PS shows a significantly different thermal degradation profile. There is no significant weight loss before 390°C, indicating successful and stable grafting of PS onto the MoS2 surface. A sharp weight loss in the range of 410°C–610°C is associated with the decomposition of the grafted PS chains and the MoS2 structure itself at a higher temperature, and the final weight loss ratio is significantly increased to 44.8%. According to TGA curves of MoS2-g-PS and MoS2-KH570, it can be estimated that the grafting ratio of PS is 18% [36]. In Fig. 2b, the pure MoS2 exhibits a degradation peak with the highest rate of 96°C, mainly due to the rapid volatilization of the bound water on the surface and the interlayer water. Accordingly, the weight loss peak of the DTG curve of MoS2-KH570 at 405.5°C corresponds to the decomposition of KH570. Further, two degradation peaks appear in the curve of MoS2-g-PS. The first peak at 423.6°C is mainly due to the decomposition of PS, and the second degradation peak at 510.3°C is mainly attributed to the accelerated interlayer collapse of MoS2.

Figure 2: (a) TGA and (b) DTG curves of MoS, MoS2–KH570 and MoS2-g-PS

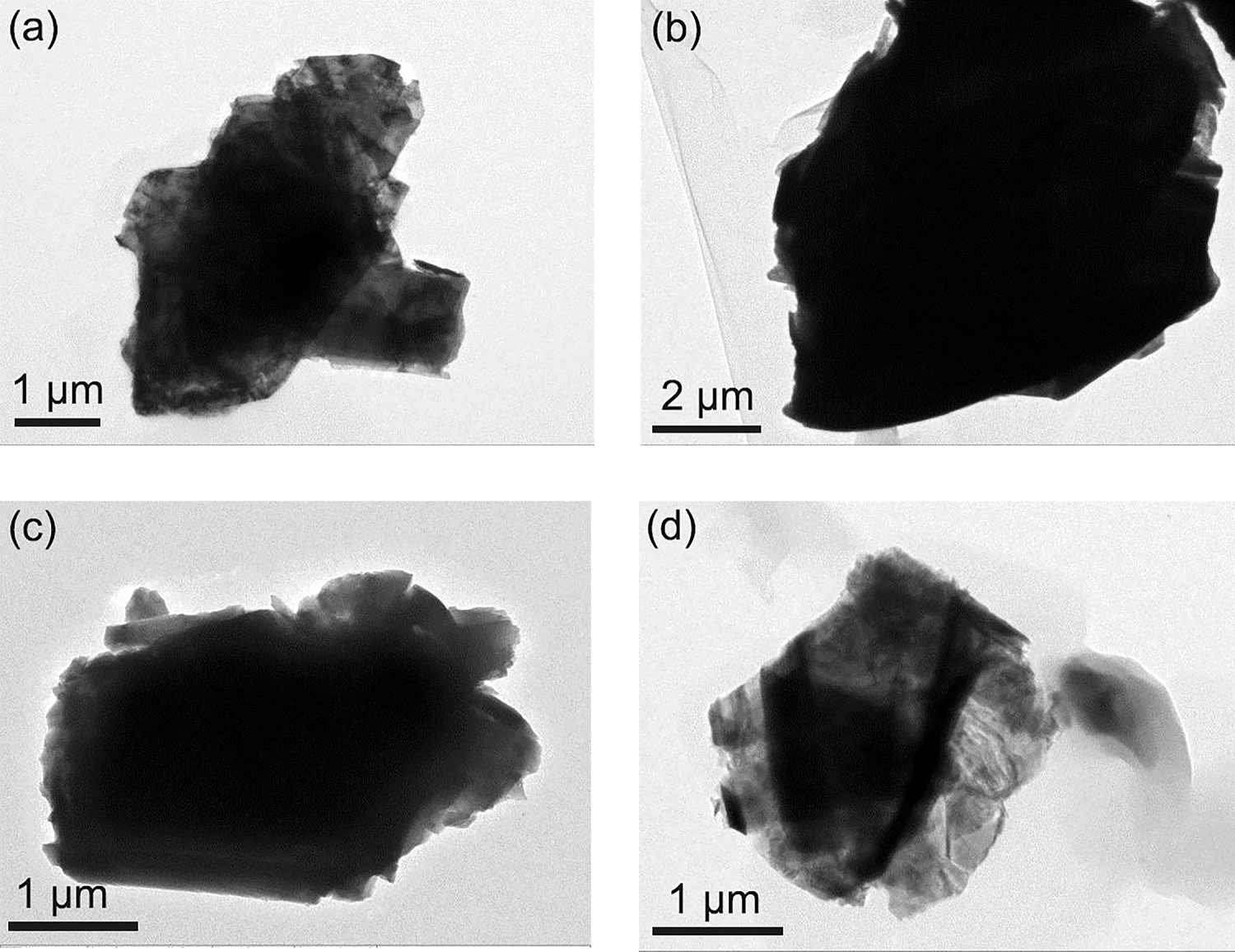

Fig. 3 presents the TEM images of MoS2 and MoS2-g-PS particles at different magnifications. Fig. 3a,b shows unmodified MoS2 particles at different magnifications. The MoS2 powder exhibits a characteristic two-dimensional lamellar structure, with the layers closely stacked and cross-linked in an irregular morphology. In Fig. 3c,d, MoS2-g-PS reveals that the grafting of PS induces some agglomeration of the MoS2 particles, and leaves light-gray layer coating the surface of the MoS2. Thus, a relatively complete core-shell structure with the inorganic MoS2 as the core and the polymer PS as the shell is formed. Furthermore, it is evident that the PS coating envelops numerous MoS2 particles. This core-shell structure is a result of free radicals, generated from the initiator AIBN, attacking the carbon-carbon double bonds introduced by the KH-570 on the MoS2 surface. This reaction initiates the graft polymerization of St monomer directly from the particle surface, ultimately forming the continuous polystyrene coating [37].

Figure 3: TEM photos of (a,b) MoS2 and (c,d) MoS2-g-PS

3.2 Laser Labeling of PP/MoS2-g-PS Composites

Fig. 4 presents the laser marking results for pure PP, PP/MoS2, and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites with the same filler content of 0.02 wt% under identical laser processing parameters. The marked pattern is a 15 × 15 mm QR code on the grey-white matrix material. As shown in Fig. 4a, the QR code on the pure PP surface is blurred, with discontinuous and non-uniform carbonization. Large carbon particles are visible, indicating poor marking quality. This is primarily due to the weak absorption of near-infrared laser energy by PP; most of the laser energy is transmitted through the material rather than being absorbed to induce carbonization, leading to inefficient energy utilization. Fig. 4b shows the PP/MoS2 composite. The carbonized surface appears more continuous and uniform than that of pure PP. However, carbon deposition at the edges of the code is insufficient, resulting in low contrast and poor scannability of the QR code. Fig. 4c demonstrates the result for the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite. This sample exhibits a uniform, high-contrast carbonized surface with clear pattern definition and strong edge sharpness. The QR code is easily scannable, indicating high practical applicability. This superior performance is attributed to the strong near-infrared laser absorption of MoS2, combined with the enhanced laser responsiveness imparted by the grafted polystyrene. The phenyl rings in the PS chains carbonize readily under laser irradiation, facilitating extensive and uniform carbon formation at lower energy thresholds, thereby producing a clear, well-defined, and highly recognizable mark.

Figure 4: Laser characterization of the (a) PP, (b) PP/MoS2 and (c) PP/MoS2-g-PS composites

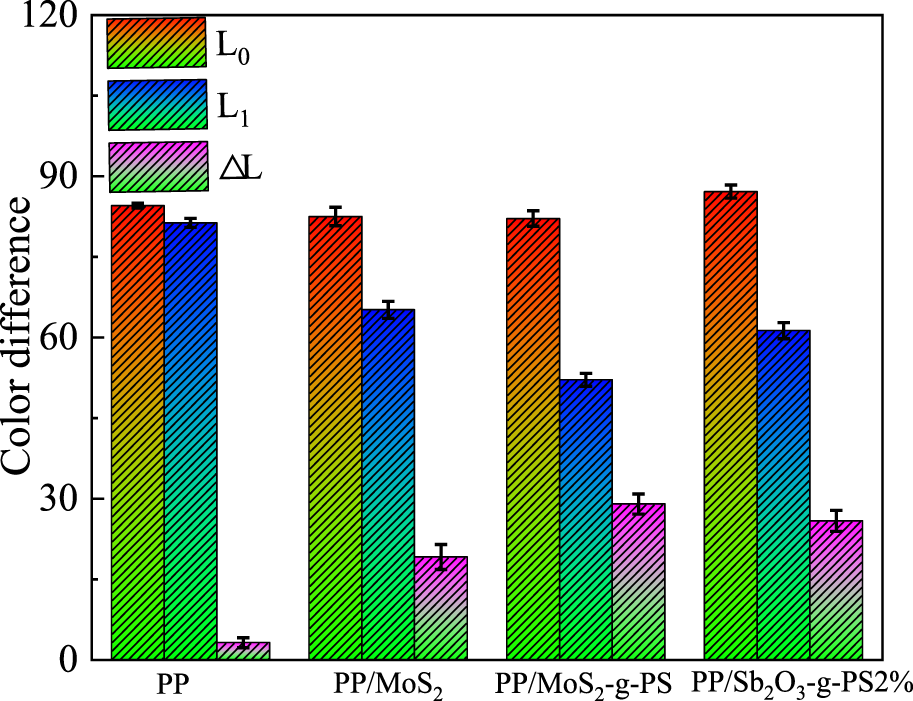

Fig. 5 presents the color difference values (|ΔL|) for pure PP, PP/MoS2, and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites laser-marked under identical parameters. The |ΔL| value was 3.21 for pure PP, which represents the lightness contrast and quantifies the laser marking response [38]. This low value indicates very poor contrast and minimal carbonization. The incorporation of pure MoS2 into the PP matrix significantly increased the |ΔL*| value to 19.15, demonstrating a substantial enhancement in laser absorption and marking contrast. Furthermore, the addition of the MoS2-g-PS resulted in the highest |ΔL*| value of 29.01. This indicates that the surface modification of MoS2 with PS further amplifies the laser responsiveness of the composite, yielding the greatest visual contrast for the marked patterns. Importantly, the laser marking effect of PP composites at a lower MoS2-g-PS content (1 wt% of Sb2O3-g-PS) can be better than that of PP/Sb2O3-g-PS composites.

Figure 5: Color difference values before and after laser labeling of PP, PP/MoS2, PP/MoS2-g-PS and PP/Sb2O3-g-PS composites

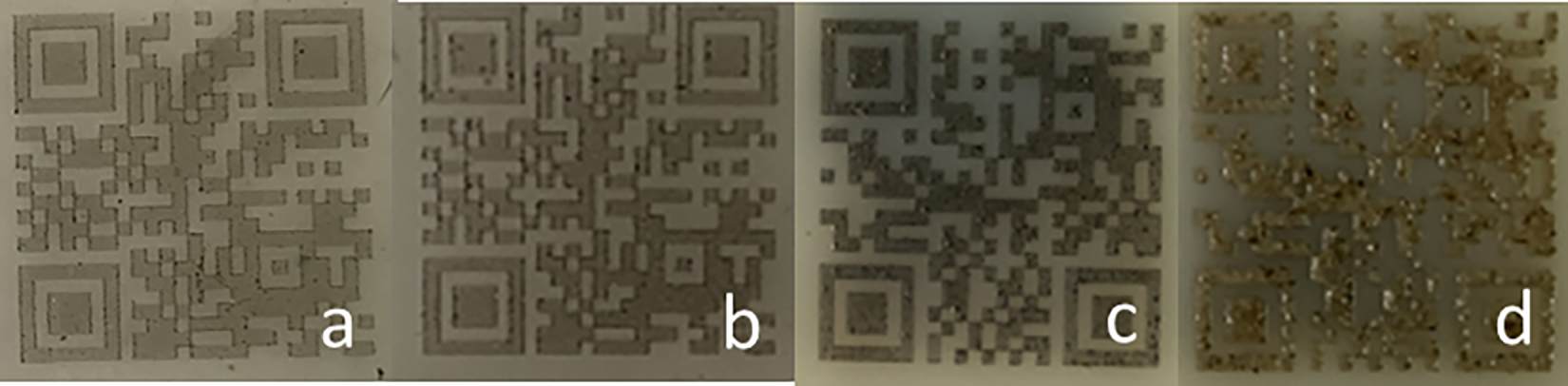

Fig. 6 illustrates the effect of laser current intensity on the marking quality of a PP/MoS2-g-PS composite. The marked pattern is a 25 × 25 mm QR code on an off-white matrix. Fig. 6a–d corresponds to laser currents of 9, 10, 11, and 12 A, respectively. As the current intensity increases, the degree of surface carbonization becomes more pronounced, resulting in a corresponding increase in pattern clarity and contrast. However, at the highest current of 12 A, the excessive laser energy causes severe surface ablation. This leads to slight bubbling and non-uniform carbon deposition, particularly at the edges of the pattern, consequently reducing the overall clarity and quality of the laser mark. This occurs despite the composite’s high responsiveness to near-infrared laser radiation.

Figure 6: Labeling effects of PP/MoS2-g-PS composites at different currents (a) 9 A; (b) 10 A; (c) 11 A; (d) 12 A

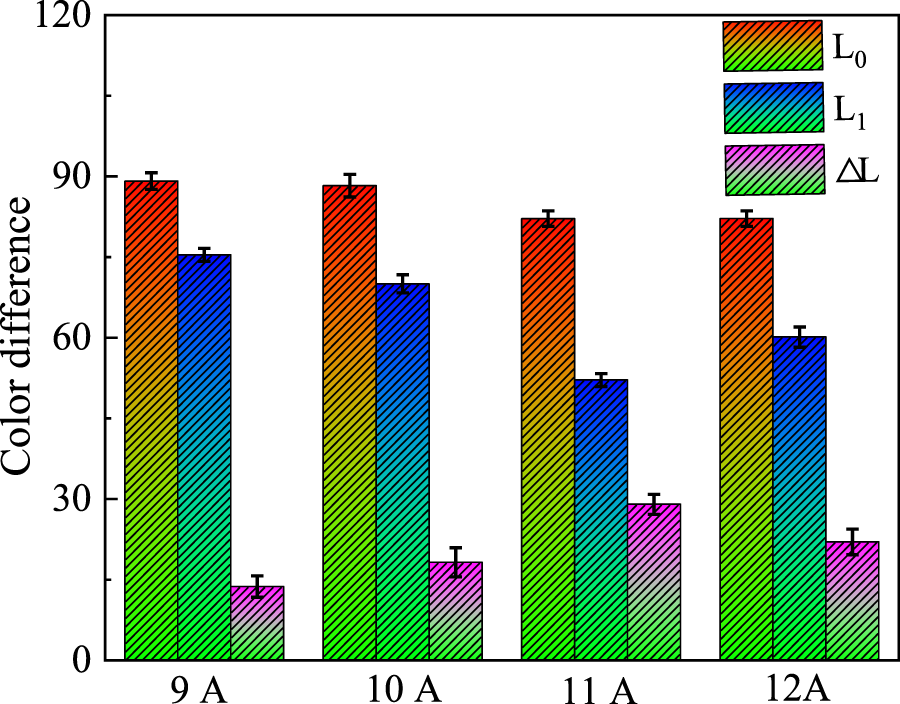

Fig. 7 shows the color difference values (|ΔL|) of the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite as a function of laser current intensity. The |ΔL| value increases with rising current, indicating a corresponding enhancement in contrast due to greater carbonization. This trend demonstrates the strong and increasing responsiveness to NIR laser energy. However, a threshold is observed at 12 A, which is due to the excessive energy causes severe surface ablation and lead to a decrease in |ΔL*|. The internal temperature of the polymer becomes excessively high, resulting in bubbling and non-uniform carbonization [39]. The above results show that there is a threshold for the laser intensity of PP/MoS2-g-PS composites, and further increasing the current will not improve the laser response, but cause damage through ablation and reduce the marking quality.

Figure 7: Color difference values of PP/MoS2-g-PS composites before and after laser labeling at different currents

3.3 Raman Analysis of Laser-Labeled Surfaces of PP/MoS2-g-PS Composites

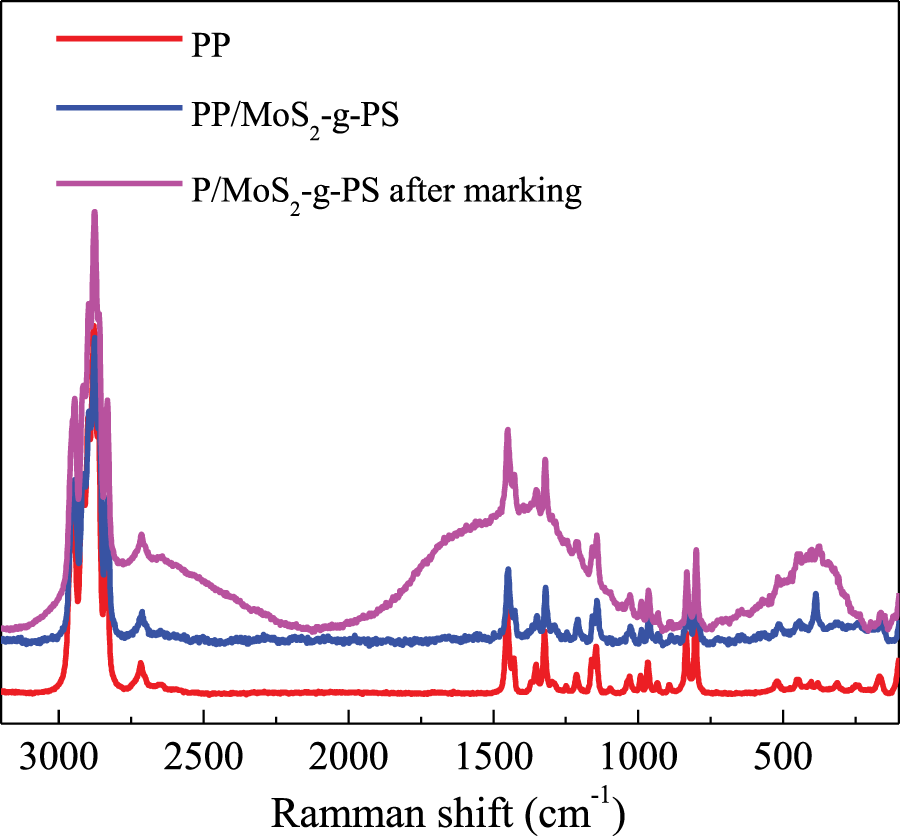

Fig. 8 presents the Raman spectra of pure PP and the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite before and after laser marking. The pure MoS2 displays the characteristic Raman peaks around 380 and 410 cm−¹ (E¹2g and A1g modes) [40]. As for the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite after laser marking, a prominent broad peak (D and G band) appears between 1000 and 2000 cm−¹, which is the characteristic of amorphous carbon, while the characteristic peaks of PP are still retained [41]. This indicates that the laser energy pyrolyzed the polymer matrix, generating a large amount of amorphous carbon on the surface. Crucially, the characteristic peaks of MoS2 remain present in the spectrum, and no new chemical species are detected. This confirms that MoS2 itself did not decompose during the laser marking process. MoS2 functions primarily as a highly effective laser-sensitive additive, absorbing energy and facilitating the carbonization of the polymer matrix without undergoing chemical change itself.

Figure 8: Raman spectra of PP and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites before and after laser labeling

3.4 Near-Infrared Absorption Spectra of PP/MoS2-g-PS Composites

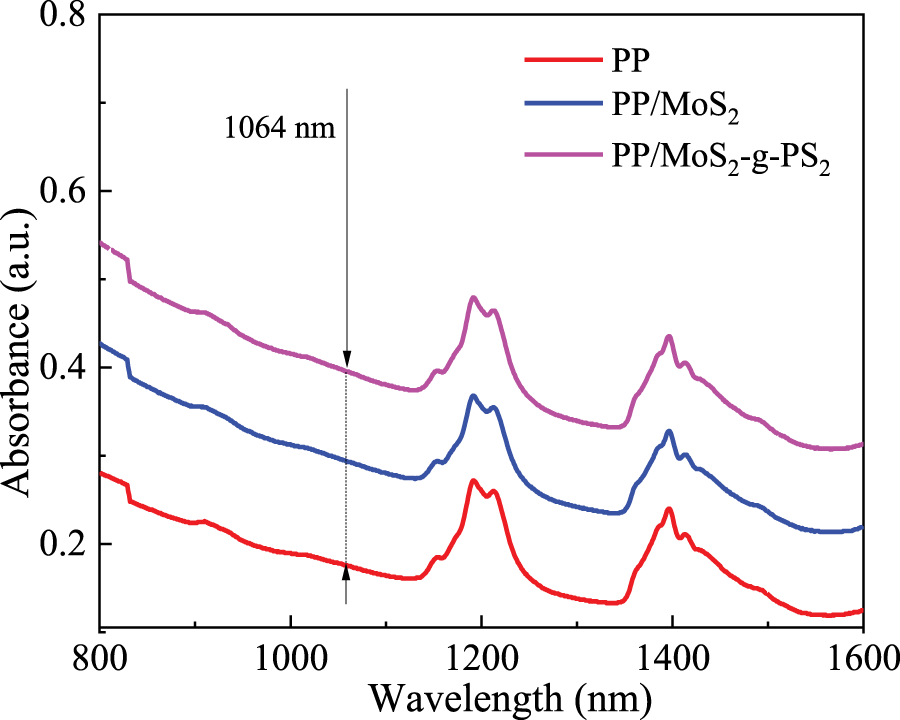

Fig. 9 shows the UV-vis-NIR spectra of pure PP, PP/MoS2, and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites. These spectra are acquired to demonstrate the enhanced NIR laser responsiveness imparted by the MoS2-based additives. It is evident that the pure PP exhibits minimal absorption at the 1064 nm wavelength. In contrast, the PP/MoS2 composite shows significantly higher absorption at 1064 nm. The PP/MoS2-g-PS composite demonstrates the highest absorption intensity at this wavelength, exceeding that of both pure PP and the PP/MoS2 composite. These results confirm that MoS2 significantly enhances the NIR absorption capability of the composite. Furthermore, the surface modification of MoS2 with PS provides an additional increase in absorption. This improved absorption directly correlates with the higher |ΔL*| values and superior contrast observed in the laser-marked PP/MoS2-g-PS samples, as the absorbed laser energy is more efficiently converted into heat. The local temperature far exceeds the decomposition temperature of PS in a short time, and the high carbon residue rate of PS. The local temperature far exceeds the decomposition temperature of PS in a short time, leading to more effective carbonization due to the high char residue rate of PS.

Figure 9: UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra of PP, PP/MoS2 and PP/MoS2-g-PS composite

3.5 SEM Analysis of the Laser-Labeled Surface of PP/MoS2-g-PS Composites

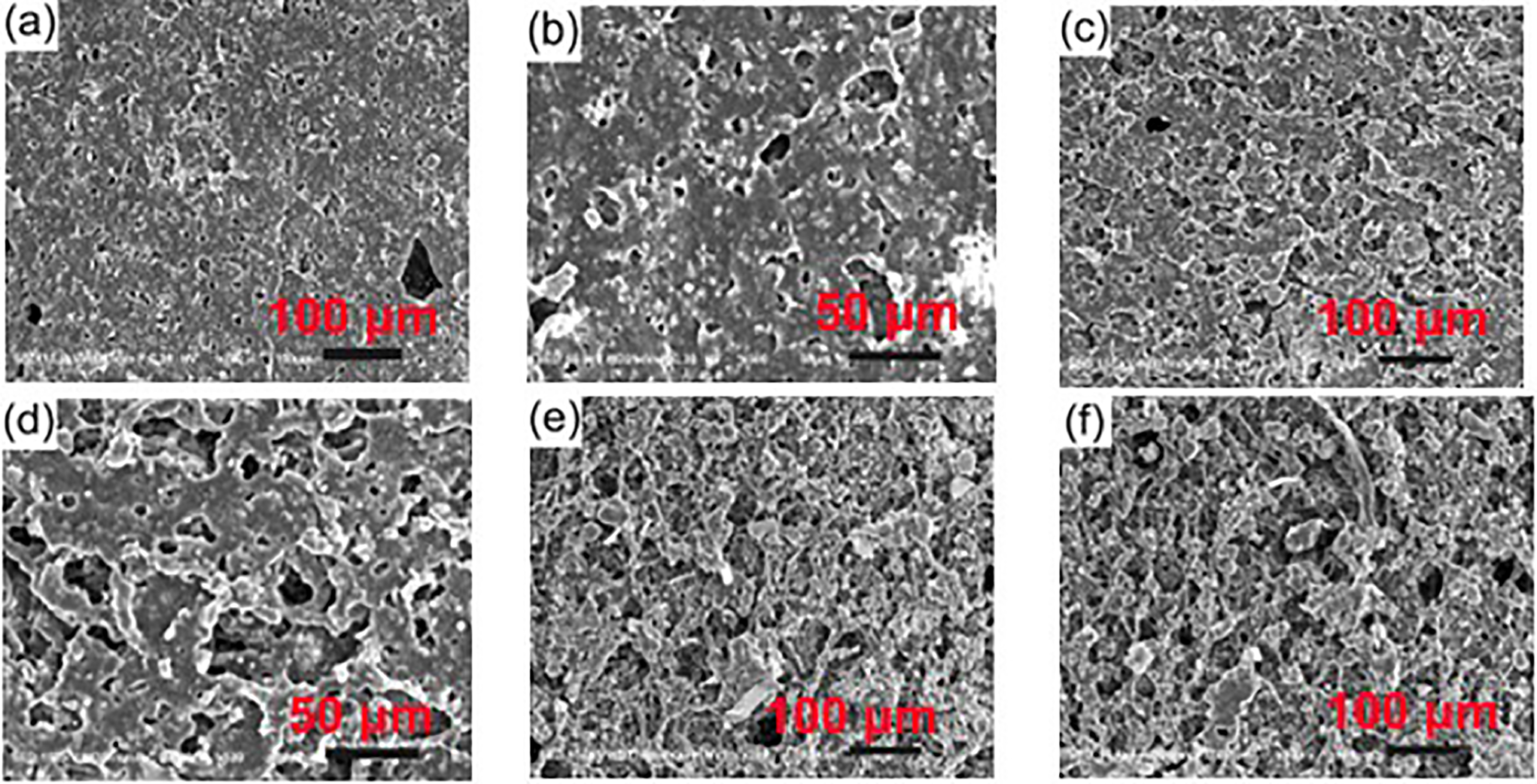

Fig. 10 presents SEM images of laser-marked surfaces for pure PP, PP/MoS2, and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites at different magnifications. As shown in Fig. 10a,b, the pure PP surface exhibits minimal ablation and low carbon deposition. This is due to the poor responsiveness of pure PP to near-infrared laser radiation, resulting in inefficient energy absorption and minimal surface modification. Fig. 10c,d depicts the PP/MoS2 composite. The addition of MoS2 significantly enhances the laser absorption, leading to more pronounced ablation traces and a higher degree of surface carbonization compared to pure PP. As for the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite in Fig. 10e,f exhibits the most severe surface modification characterized by the formation of gully-like cracks and extensive carbonization. This enhancement stems from a synergistic mechanism wherein the MoS2 core efficiently harvests laser energy and the PS shell readily carbonises, focusing the energy into local ablation pits that coalesce into a uniform, high-contrast carbon film clearly delineated from the unmarked matrix.

Figure 10: SEM images of (a,b) PP, (c,d) PP/MoS2 and (e,f) PP/MoS2-g-PS composites

3.6 Contact Angle Analysis of Laser Labeled Surface of PP/MoS2-g-PS Composite

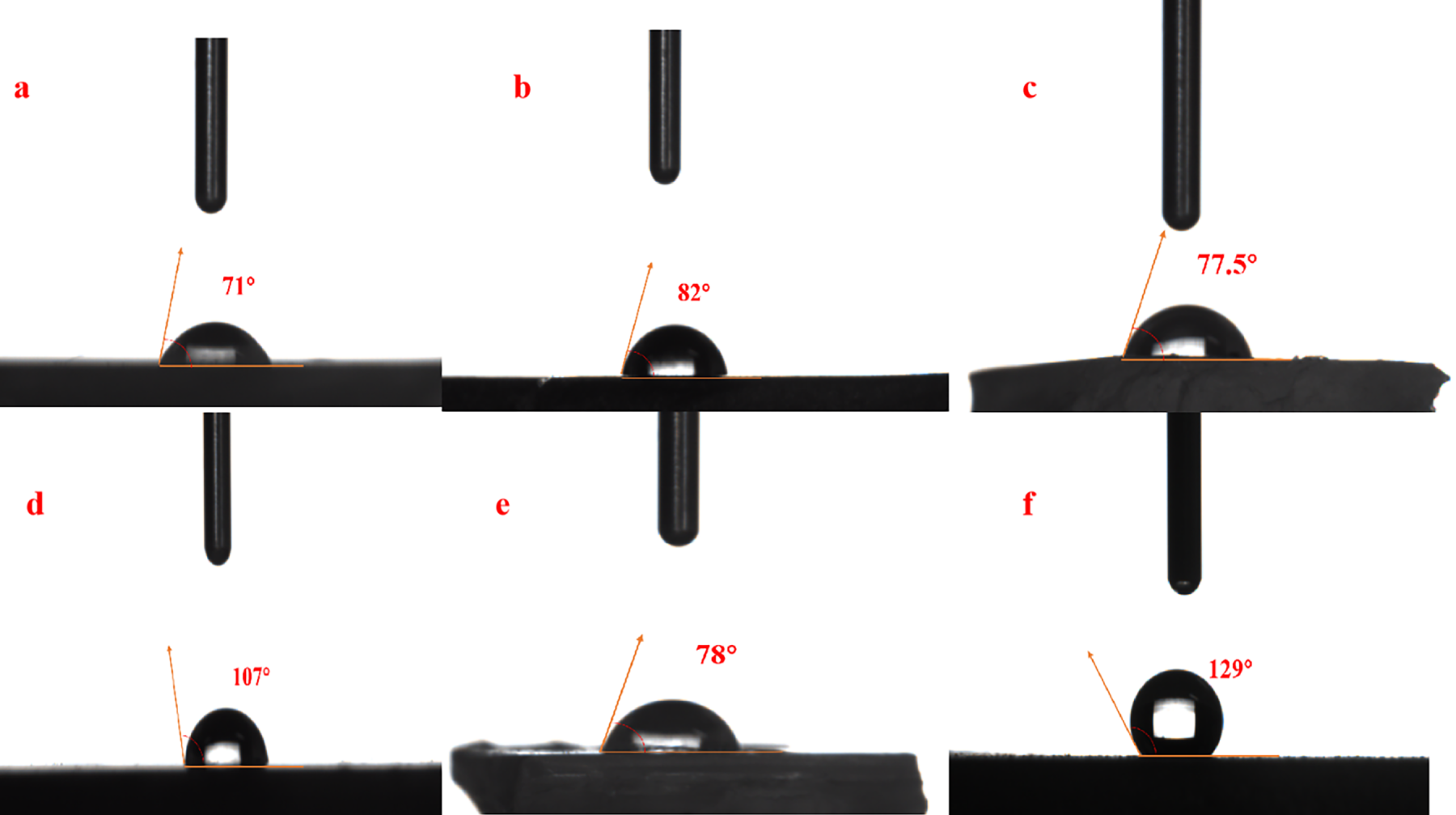

Fig. 11 presents the water contact angles of the composites before and after laser marking. Pure PP shows the smallest contact angle increase after marking, which is attributed to the poor near-infrared laser responsiveness of PP. The lower energy absorption and minimal surface carbonization result in a negligible change in surface wettability. After the introduction of MoS2, a significant change in contact angle from 77.5° to 107° is observed after marking at an 11 A laser current. The strong near-infrared laser absorption capacity of MoS2 leads to severe surface ablation, extensive carbonization, and a transition to a more hydrophobic surface [42]. Fig. 11e,f shows the results for the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite, which exhibits the most pronounced change. The contact angle reaches 129° under the same lasing conditions (11 A). This superior performance is due to a synergistic effect of both the MoS2 core and the PS shell. Due to the strong absorption ability of MoS2 to NIR energy, PS with high carbon content is highly prone to carbonization, enhancing the overall carbon yield and creating a rougher, more textured carbonized surface morphology. This increased surface roughness, combined with the hydrophobic nature of the carbon layer results in a higher contact angle. Compared to the PP/MoS2 composite, the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite demonstrates a higher degree of carbonization, which contributes to higher marking clarity, contrast, and potentially greater durability and stability of the laser-marked pattern.

Figure 11: The surface contact angles of (a,b) PP, (c,d) PP/MoS2 and (e,f) PP/MoS2-g-PS composites before and after laser labeling

3.7 Mechanical Properties of PP/MoS2-g-PS Composites

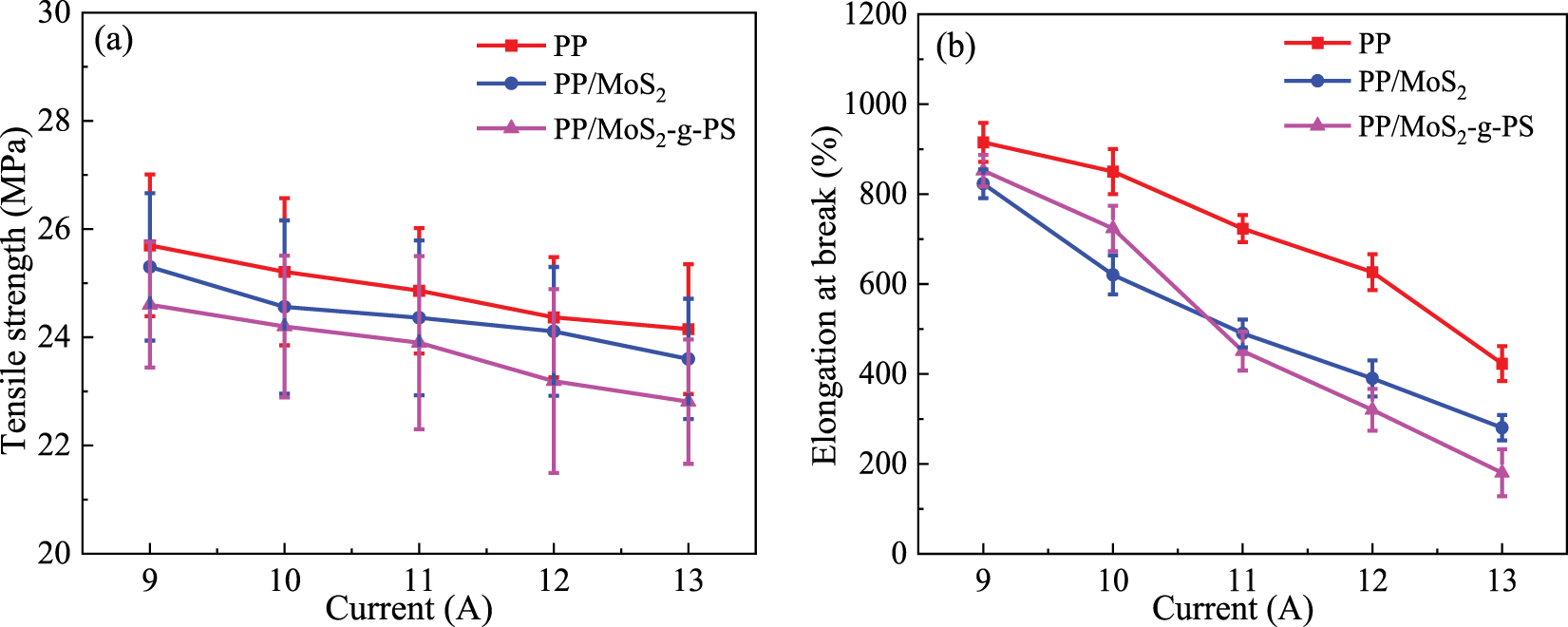

Fig. 12 shows the tensile properties of pure PP, PP/MoS2, and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites after laser marking at different current intensities. The elongation at break of all specimens decreased markedly with increasing current, the drop being substantially greater than that in tensile strength. Consequently, the surface-layer failure mode changed from ductile yielding to brittle fracture. Pure PP exhibited typical plastic failure and very high elongation at break. After laser marking, a rigid, cross-linked, graphite-like brittle structure formed in the carbonized zone, which lost virtually all capacity for plastic deformation. Upon stretching, stress could no longer be dissipated by chain-segment motion, and microscopic defects therefore propagated rapidly into cracks, causing a sharp drop in elongation at break [43]. In terms of tensile strength, the brittle carbonized layer itself has a highly crosslinked and carbonized structure, which can bear the stress on the matrix to some extent until the fracture occurs [44]. However, there are also differences between different samples. Pure PP absorbs less laser energy, resulting in lower surface ablation, shallower pits, and consequently less decrease in mechanical properties. The tensile properties of the composites show a more complex decline. On the one hand, the intense laser-energy absorption by MoS2 produces severe surface damage—cracks and deep ablation pits that act as stress concentrators. On the other hand, the poor compatibility between unmodified MoS2 and the PP matrix further amplifies stress concentration during tensile loading, resulting in premature failure. The tensile properties of the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite deteriorate more sharply than those of the PP/MoS2 system. This accelerated decline is attributed to severe surface ablation caused by the synergistic laser-energy absorption of MoS2 and PS, which produces deep surface defects. In addition, the carbonization of PS generates fine carbon particles within the matrix. These particles, together with the inherent inhomogeneity of the composite, act as stress concentrators during stretching, collectively cause a substantial reduction in mechanical performance.

Figure 12: (a) Tensile strength and (b) elongation at break of PP, PP/MoS2 and PP/MoS2-g-PS composites after laser labeling at different currents

3.8 Surface Resistance after Laser Labeling of PP/MoS2-g-PS Composite

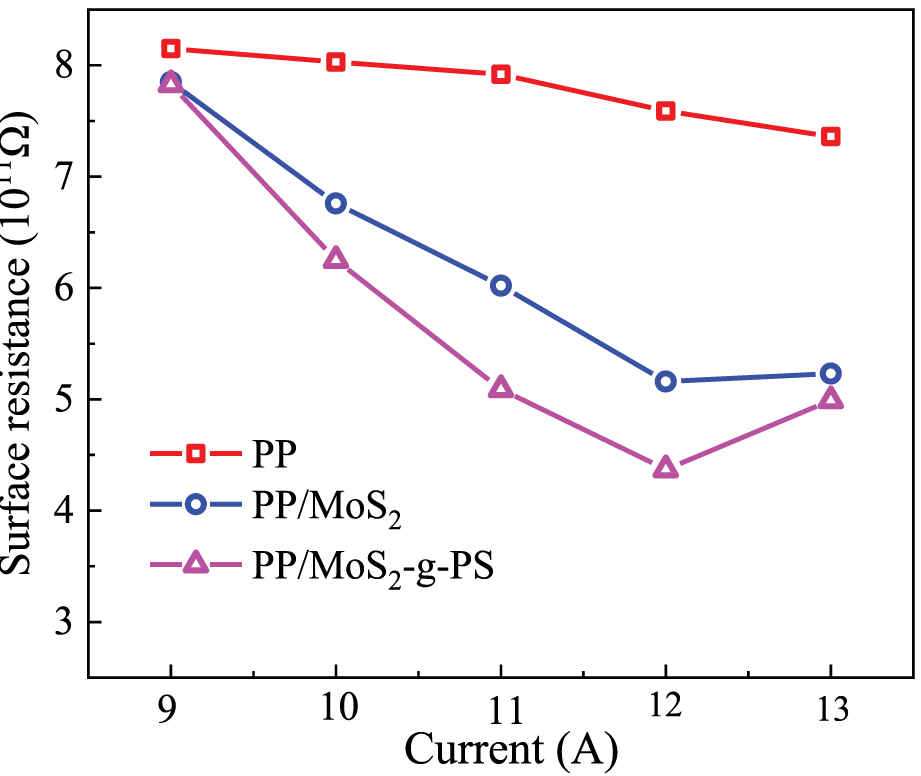

Fig. 13 shows the surface resistance of pure PP, PP/MoS2 and PP/MoS2-g-PS as a function of laser-current power. For all materials, resistance decreased modestly with increasing current, attributable to the formation of a conductive carbonized surface layer. However, when the laser current exceeds a certain threshold (e.g., 13 A), the surface resistance increases. This occurs because excessive laser energy induces local overheating, causing the polymer matrix to bubble and foam; these voids disrupt the continuity and density of the carbon layer. Since the laser operates in pulsed mode, the marking trace consists of discrete spots that coincide with foam pores at high power, producing a porous, non-uniform carbon film. Consequently, the net reduction in surface resistance remains <1 decade and is insufficient to impart bulk electrical conductivity. Thus, resistance variations serve solely as an indirect gauge of the density and continuity of the laser-formed carbon layer, rather than conferring significant conductive properties on the composites.

Figure 13: Surface resistance values of different composites after laser labeling at different currents

As a rendering of the laser marker, Fig. 14 displays the laser-marked QR code effect on a 0.02 wt% PP/MoS2-g-PS composite, processed at a laser current of 11 A. The resulting QR code exhibits high clarity and contrast, enabling rapid and successful scanning and recognition by standard QR code readers.

Figure 14: Laser-labeled QR code map of PP/MoS2-g-PS composite

This study demonstrates that the incorporation of a MoS2-g-PS additive markedly improves the laser marking performance of polypropylene (PP), which is attributed to a synergistic effect between the strong NIR absorption of MoS2 and the high laser-induced carbonization rate of the grafted PS layer. Compared to pure PP and PP/MoS2 composite, the PP/MoS2-g-PS composite with a MoS2 content of 0.02 wt% achieves optimal mark clarity, yielding a maximum lightness contrast (ΔL*) of 29.01 a reasonable mechanical properties under a laser current of 11 A. The findings establish a straightforward, economical, and scalable method for fabricating environmentally friendly laser-markable PP composites using MoS2-based additives, thereby presenting a strategy with potential applicability to other engineering polymers. Owing to their performance, these composites hold significant promise for applications in areas demanding high-definition and efficient marking such as electronic appliances, automobile industry, medical equipment, food packaging, security and anti-counterfeiting.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank School of Materials Science and Engineering, Changzhou University for material test.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation: Minglei Hu; resources, data curation: Wei Zhang and Bin Hu; writing—review and editing, supervision, Haicun Yang, Fuqiang Chu, and Zheng Cao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li H, Liang J. Recent development of printed micro-supercapacitors: printable materials, printing technologies, and perspectives. Adv Mater. 2020;32(3):e1805864. doi:10.1002/adma.201805864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Nsilani Kouediatouka A, Ma Q, Liu Q, Mawignon FJ, Rafique F, Dong G. Design methodology and application of surface texture: a review. Coatings. 2022;12(7):1015. doi:10.3390/coatings12071015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen YC, Salter PS, Niethammer M, Widmann M, Kaiser F, Nagy R, et al. Laser writing of scalable single color centers in silicon carbide. Nano Lett. 2019;19(4):2377–83. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b05070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Feng J, Zhang J, Zheng Z, Zhou T. New strategy to achieve laser direct writing of polymers: fabrication of the color-changing microcapsule with a core-shell structure. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11(44):41688–700. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b15214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zang X, Shen C, Chu Y, Li B, Wei M, Zhong J, et al. Laser-induced molybdenum carbide-graphene composites for 3D foldable paper electronics. Adv Mater. 2018;30(26):e1800062. doi:10.1002/adma.201800062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Jakubowicz I, Yarahmadi N. Review and assessment of existing and future techniques for traceability with particular focus on applicability to ABS plastics. Polymers. 2024;16(10):1343. doi:10.3390/polym16101343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Mezera M, Alamri S, Hendriks WAPM, Hertwig A, Elert AM, Bonse J, et al. Hierarchical micro-/nano-structures on polycarbonate via UV pulsed laser processing. Nanomater. 2020;10(6):1184. doi:10.3390/nano10061184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Kościuszko A, Czyżewski P, Rojewski M. Modification of laser marking ability and properties of polypropylene using silica waste as a filler. Materials. 2021;14(22):6961. doi:10.3390/ma14226961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang C, Dai Y, Lu G, Cao Z, Cheng J, Wang K, et al. Facile fabrication of high-contrast and light-colored marking on dark thermoplastic polyurethane materials. ACS Omega. 2019;4(24):20787–96. doi:10.1021/acsomega.9b03232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yu Z, Wang JH, Li Y, Bai Y. Glass fiber reinforced polycarbonate composites for laser direct structuring and electroless copper plating. Polym Eng Sci. 2020;60(4):860–71. doi:10.1002/pen.25345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Awasthi A, Kumar D, Marla D. Understanding the role of oxide layers on color generation and surface characteristics in nanosecond laser color marking of stainless steel. Opt Laser Technol. 2024;171:110469. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.110469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhou J, Cheng J, Zhang C, Wu D, Liu C, Cao Z. Controllable Black or White laser patterning of polypropylene induced by carbon nanotubes. Mater Today Commun. 2020;24:100978. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.100978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jagodziński B, Rytlewski P, Moraczewski K, Trafarski A, Karasiewicz T. The effect of antimony (III) oxide on the necessary amount of precursors used in laser-activated coatings intended for electroless metallization. Materials. 2022;15(15):5155. doi:10.3390/ma15155155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Cheng J, Zhou J, Lin Z, Wu D, Liu C, Cao Z, et al. Locally controllable laser patterning transfer of thermoplastic polyurethane induced by sustainable bismuth trioxide substrate. Appl Surf Sci. 2021;550:149299. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.149299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Clemente MJ, Lavieja C, Peña JI, Oriol L. UV-laser marking of a TiO2-containing ABS material. Polym Eng Sci. 2018;58(9):1604–9. doi:10.1002/pen.24749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shivakoti I, Kibria G, Pradhan BB. Predictive model and parametric analysis of laser marking process on gallium nitride material using diode pumped Nd: YAG laser. Opt Laser Technol. 2019;115:58–70. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2019.01.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yang J, Xiang M, Zhu Y, Yang Z, Ou J. Influences of carbon nanotubes/polycarbonate composite on enhanced local laser marking properties of polypropylene. Polym Bull. 2023;80(2):1321–33. doi:10.1007/s00289-022-04123-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Khatami P, Nabavi SF, Farshidianfar A. A comprehensive review of laser marking: an in-depth exploration of processes, methods, parameters, materials, and applications. Weld World. 2025;69(11):3415–42. doi:10.1007/s40194-025-02129-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li Z, Zhang B, Li K, Zhang T, Yang X. A wide linearity range and high sensitivity flexible pressure sensor with hierarchical microstructures via laser marking. J Mater Chem C. 2020;8(9):3088–96. doi:10.1039/c9tc06352h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu C, Lu Y, Xiong Y, Zhang Q, Shi A, Wu D, et al. Recognition of laser-marked quick response codes on polypropylene surfaces. Polym Degrad Stab. 2018;147:115–22. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.11.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xing Y, Wan Y, Wu Z, Wang J, Jiao S, Liu L. Multilayer ultrathin MXene@AgNW@MoS2 composite film for high-efficiency electromagnetic shielding. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(4):5787–97. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c18759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Peng Z, Su Y, Jafari M, Siaj M. Engineering interfacial band hole extraction on chemical-vapor-deposited MoS2/CdS core-shell heterojunction photoanode: the junction thickness effects on photoelectrochemical performance. J Mater Sci Technol. 2023;167:107–18. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2023.05.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Wang L, Fan Z, Yue F, Zhang S, Qin S, Luo C, et al. Flower-like 3D MoS2 microsphere/2D C3N4 nanosheet composite for highly sensitive electrochemical sensing of nitrite. Food Chem. 2024;430:137027. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Jin L, Wu S, Mao C, Wang C, Zhu S, Zheng Y, et al. Rapid and effective treatment of chronic osteomyelitis by conductive network-like MoS2/CNTs through multiple reflection and scattering enhanced synergistic therapy. Bioact Mater. 2023;31:284–97. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2023.08.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Sun Y, Yang YL, Chen HJ, Liu J, Shi XL, Suo G, et al. Flexible, recoverable, and efficient photocatalysts: MoS2/TiO2 heterojunctions grown on amorphous carbon-coated carbon textiles. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;651:284–95. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2023.07.177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ma J, Xu Y, Duan B, Qiu Y, Liang J, Xu Y, et al. In situ growth of 1T-MoS2 nanosheets on NiS porous-hollow microspheres for high-performance potassium-ion storage. Appl Surf Sci. 2023;639:158193. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.158193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xie A, Guo R, Wu L, Dong W. Anion-substitution interfacial engineering to construct C@MoS2 hierarchical nanocomposites for broadband electromagnetic wave absorption. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;651(6):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2023.07.169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Fang Y, Zheng W, Hu T, Xiao H, Li L, Yuan W. An ultrahigh-capacity dual-ion battery based on a free-standing graphite paper cathode and flower-like heterojunction anode of tin disulfide and molybdenum disulfide. ChemSusChem. 2024;17(1):e202301093. doi:10.1002/cssc.202301093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Al-Ansi N, Salah A, Drmosh QA, Yang GD, Hezam A, Al-Salihy A, et al. Carbonized polymer dots for controlling construction of MoS2 flower-like nanospheres to achieve high-performance Li/Na storage devices. Small. 2023;19(52):e2304459. doi:10.1002/smll.202304459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen C, Lee CS, Tang Y. Fundamental understanding and optimization strategies for dual-ion batteries: a review. Nanomicro Lett. 2023;15(1):121. doi:10.1007/s40820-023-01086-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Sufyan Javed M, Zhang X, Ali S, Shoaib Ahmad Shah S, Ahmad A, Hussain I, et al. Boosting the energy storage performance of aqueous NH4+ symmetric supercapacitor based on the nanostructured molybdenum disulfide nanosheets. Chem Eng J. 2023;471:144486. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.144486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Cao Z, Lu G, Gao H, Xue Z, Luo K, Wang K, et al. Preparation and laser marking properties of poly(propylene)/molybdenum sulfide composite materials. ACS Omega. 2021;6(13):9129–40. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c00255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wang L, Li R, Wang C, Hao B, Shao J. Surface grafting modification of titanium dioxide by silane coupler KH570 and its influences on the application of blue light curing ink. Dyes Pigm. 2019;163:232–7. doi:10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.11.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Khan IA, Hussain H, Yasin T, Inaam-ul-Hassan M. Surface modification of mesoporous silica by radiation induced graft polymerization of styrene and subsequent sulfonation for ion-exchange applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2020;137(26):48835. doi:10.1002/app.48835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhou K, Tang G, Gao R, Guo H. Constructing hierarchical polymer@MoS2 core-shell structures for regulating thermal and fire safety properties of polystyrene nanocomposites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2018;107:144–54. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.12.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Mardani H, Roghani-Mamaqani H, Khezri K, Salami-Kalajahi M. Polystyrene-attached graphene oxide with different graft densities via reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization and grafting through approach. Appl Phys A. 2020;126(4):251. doi:10.1007/s00339-020-3428-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Du R, Gao B, Men J, An F. Characteristics and advantages of surface-initiated graft-polymerization as a way of “grafting from” method for graft-polymerization of functional monomers on solid particles. Eur Polym J. 2020;127:109479. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2020.109479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Brihmat-Hamadi F, Amara EH, Lavisse L, Jouvard JM, Cicala E, Kellou H. Surface laser marking optimization using an experimental design approach. Appl Phys A. 2017;123(4):230. doi:10.1007/s00339-017-0802-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Singh AK, Sahu A, Anand PI. Unraveling spatial variations of graphenization of Kapton polyimide via CO2 laser interaction: a comprehensive theoretical simulation and Raman spectroscopy mapping study. Appl Phys A. 2023;129(11):799. doi:10.1007/s00339-023-07083-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Windom BC, Sawyer WG, Hahn DW. A Raman spectroscopic study of MoS2 and MoO3: applications to tribological systems. Tribol Lett. 2011;42(3):301–10. doi:10.1007/s11249-011-9774-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Tarasenka N, Stupak A, Tarasenko N, Chakrabarti S, Mariotti D. Structure and optical properties of carbon nanoparticles generated by laser treatment of graphite in liquids. Chemphyschem. 2017;18(9):1074–83. doi:10.1002/cphc.201601182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Zhou Z, Li B, Shen C, Wu D, Fan H, Zhao J, et al. Metallic 1T phase enabling MoS2 nanodots as an efficient agent for photoacoustic imaging guided photothermal therapy in the near-infrared-II window. Small. 2020;16(43):e2004173. doi:10.1002/smll.202004173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Lu G, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Wang K, Gao H, Luo K, et al. Surface laser-marking and mechanical properties of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene copolymer composites with organically modified montmorillonite. ACS Omega. 2020;5(30):19255–67. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c02803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Basavaraj E, Ramaraj B, Siddaramaiah. Polycarbonate/molybdenum disulfide/carbon black composites: physicomechanical, thermal, wear, and morphological properties. Polym Compos. 2012;33(4):619–28. doi:10.1002/pc.22179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools