Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

State-Space Reduction Techniques Exploiting Specific Constraints for Quantum Search Initialization, Application to an Outage Planning Problem

1 Hopia, 52 Rue de Dunkerque, Paris, 75009, France

2 Welinq, 40 Rue des Boulangers, Paris, 75005, France

3 IQM GermanyGmbH, Georg-Brauchle-Ring 23–25, München, 80992, Germany

* Corresponding Author: Rodolphe Griset. Email:

# Former Affiliation: EDF R&D, 7 Boulevard Gaspard Monge, Palaiseau, 91120, France

§ Former Affiliation: Arnold-Sommerfeld-Center for Theoretical Physics, LMU, München, 80539, Germany

Journal of Quantum Computing 2025, 7, 81-105. https://doi.org/10.32604/jqc.2025.066064

Received 28 March 2025; Accepted 10 November 2025; Issue published 08 December 2025

Abstract

Quantum search has emerged as one of the most promising fields in quantum computing. State-of-the-art quantum search algorithms enable the search for specific elements in a distribution by monotonically increasing the density of these elements relative to the rest of the distribution. These kinds of algorithms demonstrate a theoretical quadratic speed-up on the number of queries compared to classical search algorithms in unstructured spaces. Unfortunately, the major part of the existing literature applies quantum search to problems whose size grows exponentially with the input size without exploiting any specific problem structure, rendering this kind of approach not exploitable in real industrial problems. In contrast, this work proposes exploiting specific constraints of an outage planning problem, consisting in setting outage dates of production units under specific fuel management constraints and resource constraints limiting the number of outages in parallel, to build an initial superposition of states with size almost quadratically increasing as a function of the problem size. This state space reduction, inspired by the quantum walk algorithm, constructs a state superposition corresponding to all paths in a state-graph, embedding spacing constraints between outages. Our numerical results on quantum emulators highlight the potential of the state-space reduction approach. In our simplified use case, the number of iterations required to reach a 90% probability of measuring a feasible solution is reduced by a factor between 2 and 4. More importantly, the squared ratio between the number of possible configurations and the number of valid solutions shifts from exponential to linear behavior, demonstrating that the quadratic speedup offered by Grover-based algorithms becomes sufficient in this setting. While these results are based on a simplified scenario and further investigation is needed to generalize them to large-scale industrial problems, they illustrate the promise of structure-aware initialization in significantly improving the efficiency of quantum search by focusing on a smaller, more relevant solution space.Keywords

Since the introduction of the renowned Grover search algorithm [1], which demonstrated a quadratic speedup in searching for a solution in an unsorted database, quantum search has emerged as one of the most promising fields of quantum computing. This family of algorithms relies on a so-called oracle function to identify elements of interest in a space of possible solutions. The algorithm begins with an initial state superposition, typically a uniform one, which is easy to build. It then iteratively increases the density of marked elements by switching their phase and using this switch to rotate from the initial state superposition to a superposition where the marked elements have high density. The basic Grover algorithm suffers from the soufflé problem, i.e., without the exact specific number of iterations, the algorithm is likely to run for too short or too long, undershooting or overshooting the desired output distribution [2]. Over time, algorithms based on Grover have been extended to search for several marked elements [3] and to avoid the soufflé problem by adapting the rotation to only increase the density of marked elements at each iteration [4]. While Grover-based algorithms are conceptually appealing, there is little work applying these algorithms to real-world industrial use cases. In fact, this type of algorithm is primarily employed to identify the optimal or near-optimal solutions to optimization problems, which necessitate a substantial depth and a high qubit fidelity not available in current NISQ (Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum) computers. Secondly, the majority of operational research problems solved in the industry have a state-space of an exponential size with the input data, for which a quadratic speed-up might be insufficient to justify moving from a classical high performance computer (HPC) to a quantum computer (QC) in the near future. In this article, we leverage the fact that quantum search algorithms do not require a specific initial state superposition. By initializing the quantum search with a superposition that already satisfies part of the problem’s constraints, we can reduce the effective search space and thus the overall complexity. These constraints eliminate infeasible solutions from the initial space, resulting in a superposition—referred to as the reduced space state—with support only on feasible configurations. This reduction directly impacts the quantum search complexity. The proposed algorithm exploits this principle by partitioning the problem’s constraints into two categories. The first includes constraints with exploitable structure, which are embedded directly into the construction of the reduced space state through a quantum walk inspired algorithm. The second includes constraints without such structure, which are handled by the quantum oracle during the search process. We introduce this categorization in the context of a specific scheduling problem involving a set of units and associated outages to be scheduled on each unit. The problem features fuel management constraints, inducing spacing constraints between successive outages on the same unit. Additionally, outages across different units share resources—both human and material—limiting the number of outages that can be executed in parallel.

In classical settings, resource constraints make the problem computationally challenging, whereas fuel level management can be efficiently handled using an extended state graph formulation. Our approach leverages this extended state graph to construct a reduced state space, upon which quantum search is applied to address the resource constraints. We developed a quantum-walk-inspired method to build the reduced space state. While Grover’s algorithm and its derivatives have been widely proposed to tackle various applied problems, this approach of state-space reduction via quantum walk is, to the best of our knowledge, new. It should be noted that this makes our approach somewhat problem-specific, so caution should be taken when generalizing.

Similar ideas have been studied to improve the initial state of a different kind of quantum algorithms, namely variational optimization algorithms. In particular, the standard quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA) [5] also starts with the superposition of all computational basis states and, through the application of specific unitaries, tries to find the states that best solve an optimization problem. Hadfield et al. [6] proposed an evolution of QAOA, the quantum alternating operator ansatz (QAOAnsatz), which works similarly but starts with the superposition of only the states satisfying a fixed constraint1 . Correspondingly, the QAOAnsatz algorithm is designed to maintain states satisfying this constraint throughout the computation. This technique can also be used to bias the initial state superposition toward good solutions using classical heuristics [7], which act as a kind of warm-start for variational algorithms.

This work introduces a novel framework for integrating constraint-driven state-space reduction (SSR) directly into the quantum search process. Unlike prior studies that typically apply Grover’s algorithm to unstructured or uniformly initialized superpositions, our approach constructs an initial state superposition that reflects the problem’s structure using a quantum-walk-inspired method. Drawing inspiration from classical decomposition algorithms, the key idea is to exploit the structured component of the problem—considered the “easy” part—to reduce the search space before applying quantum search to the unstructured (i.e., “hard”) component. This strategy differs fundamentally from classical approaches, where the complexity often lies in the exponential number of solutions to the “easy” part, which becomes a bottleneck. In contrast, our method leverages quantum state preparation to encode feasibility directly into the initial superposition, thereby pruning the search space and allowing Grover’s algorithm to focus on the truly hard part. While the difficulty remains in the unstructured component, this targeted use of quantum search improves scalability and efficiency. Although the concept of preparing a non-uniform initial superposition is not new in quantum computing, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the distinction between structured and unstructured components of a problem has been explicitly exploited to guide the construction of the initial quantum state. This represents a novel contribution to the design of quantum algorithms for combinatorial optimization.

Building on this framework, our contributions are the following:

• We propose a structure-aware quantum search framework that explicitly exploits the internal structure of the problem. Inspired by classical decomposition techniques such as column generation and dynamic programming on networks, our approach separates the problem into a structured (easy) component and an unstructured (hard) component.

• The structured part—defined by fuel level management constraints—is used to construct a non-uniform quantum superposition via a quantum-walk-inspired scheme. This initialization enables a more efficient quantum search over the unstructured component using Grover’s algorithm, reducing the overall solution space and improving scalability.

• We apply this framework to a simplified outage planning problem, demonstrating how quantum algorithms can be adapted to structured industrial use cases.

• As a proof of concept, we implement this scheme on a simplified use case using a quantum emulator. We compare the impact of problem size on both full and reduced state-space approaches, highlighting the potential of structure-aware initialization to improve scalability and efficiency in quantum search.

This article is organized as follows: Section 2 details the state of the art of quantum search algorithms. Section 3 presents the industrial motivations and the simplified use case. Section 4 shows the direct application of a quantum search approach to this simplified use case. Section 5 introduces the proposed state-space reduction technique inspired by discrete quantum walk. Finally, Section 6 gives numerical results showcasing the scaling of our method.

2 State of the Art of Quantum Search Algorithms

The first quantum search algorithm introduced was Grover’s algorithm [1]. This algorithm relies on a special quantum gate called the oracle, which “marks” the target state by flipping its quantum phase. The oracle is used in conjunction with the Grover diffusion operator, which reflects all states about the equal superposition state. The algorithm alternates the application of the oracle and the Grover diffusion operator, which amplifies the amplitude of the target state in the superposition while suppressing the amplitudes of all other states. After approximately

Despite its advantages, Grover’s algorithm has several limitations. These have been addressed by more advanced quantum search techniques that extend Grover’s approach. One such method is amplitude amplification [3], which generalizes Grover’s algorithm by dividing the search space into two orthogonal subspaces: a “bad” subspace and a “good” subspace containing M valid solutions. Assuming the oracle can mark the good subspace, the algorithm iteratively applies the oracle and the diffusion operator, similarly to Grover’s algorithm. This process increases the amplitude of the good states while decreasing that of the bad states. After approximately

If the number of good states is not known in advance, amplitude amplification in its standard form cannot be directly applied. Without knowledge of M, the number of marked (i.e., good) states, it is impossible to determine the optimal number of Grover iterations. Performing too few iterations results in a superposition still dominated by bad states, while too many iterations can reverse the amplification effect, increasing the amplitude of bad states and suppressing the good ones.

This limitation is addressed by fixed-point search algorithms [4], which are designed to monotonically converge toward the good subspace, avoiding the risk of overshooting. These algorithms are based on the quantum singular value transformation (QSVT) [9], a powerful framework that generalizes many quantum algorithms. Theoretically, QSVT-based search algorithms retain the quadratic speedup of Grover’s algorithm. In practice, however, the actual speedup depends on the user’s uncertainty about the number of marked elements.

Assuming there are at least M marked elements, the algorithm can be executed with

In the extreme case when most of the states are good, amplitude amplification can be used for deleting the bad states with super-exponential speedup [10]. Classically, this process would take

3.1 Use Case: Production Unit Outage Planning Problem

We consider an Outage Planning Satisfiability Problem involving a set of production units

This work builds on the feasibility aspect of an outage planning problem [11], without incorporating the non-convex cost function associated with outage scheduling. In that problem, a set of units requiring periodic shutdowns is considered, and the goal is to determine outage dates under resource constraints. These include limits on the number of simultaneous outages across different units and minimum spacing between successive outages of the same unit, reflecting operational requirements such as fuel management and maintenance cycles.

Maintenance planning is critical for energy producers, as it significantly influences short-term electricity market dynamics. These problems are typically large-scale and complex, involving scheduling constraints, technical limitations, and uncertainty. The main objective is usually to meet demand at minimal cost under uncertain future conditions. Despite extensive research, optimal solutions remain elusive, and industrial approaches often rely on metaheuristics.

Quantum computing offers a promising avenue by generating high-quality candidate solutions that can serve as input for classical optimization algorithms or expert analysis. Given the difficulty of fully formalizing all constraints and cost components, our approach does not aim for optimality but rather for feasibility. Specifically, we propose a quantum-based method to generate feasible solutions to the maintenance planning problem. This paper presents a first step in that direction by formulating and solving the feasibility version of the problem using a quantum search approach.

3.3 Simplified Case and State Graph

Given the limitations of current quantum hardware and emulators, we introduce two simplifying assumptions to focus on the core idea of constructing an initial state superposition via quantum walk techniques, while also reducing circuit complexity.

Assumption 1. Unitary outage duration: All outages are assumed to have a fixed duration, which is included in the reload S.

Assumption 2. Unitary capacity and resource consumption: The resource constraint has unit capacity, meaning that no two outages from different units can be scheduled at the same time.

Our approach relies on building a quantum state in a superposition of feasible outage dates respecting fuel management. This superposition is constructed by associating each feasible combination of outage dates for a single unit with a path in a rooted acyclic graph and then quantum-walking among all such paths in superposition. The structure of this graph is derived under the following last assumption:

Assumption 3. Disjoint time windows for outages of different indices: We assume

Assumption 3 implies that, for a given unit, the possible dates for each outage index

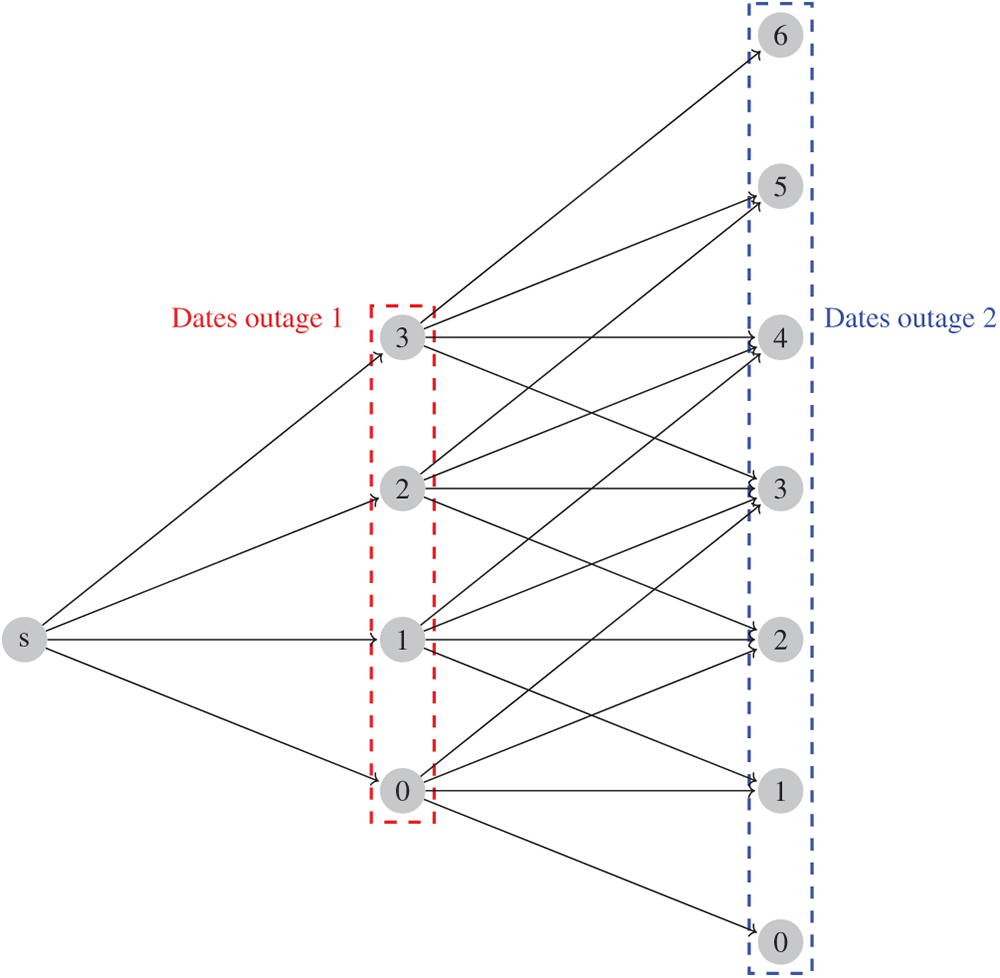

Fig. 1 illustrates the graph structure of a unit for

Figure 1: Graphical representation of the state-graph of the simplified instance for one unit and |K|=2

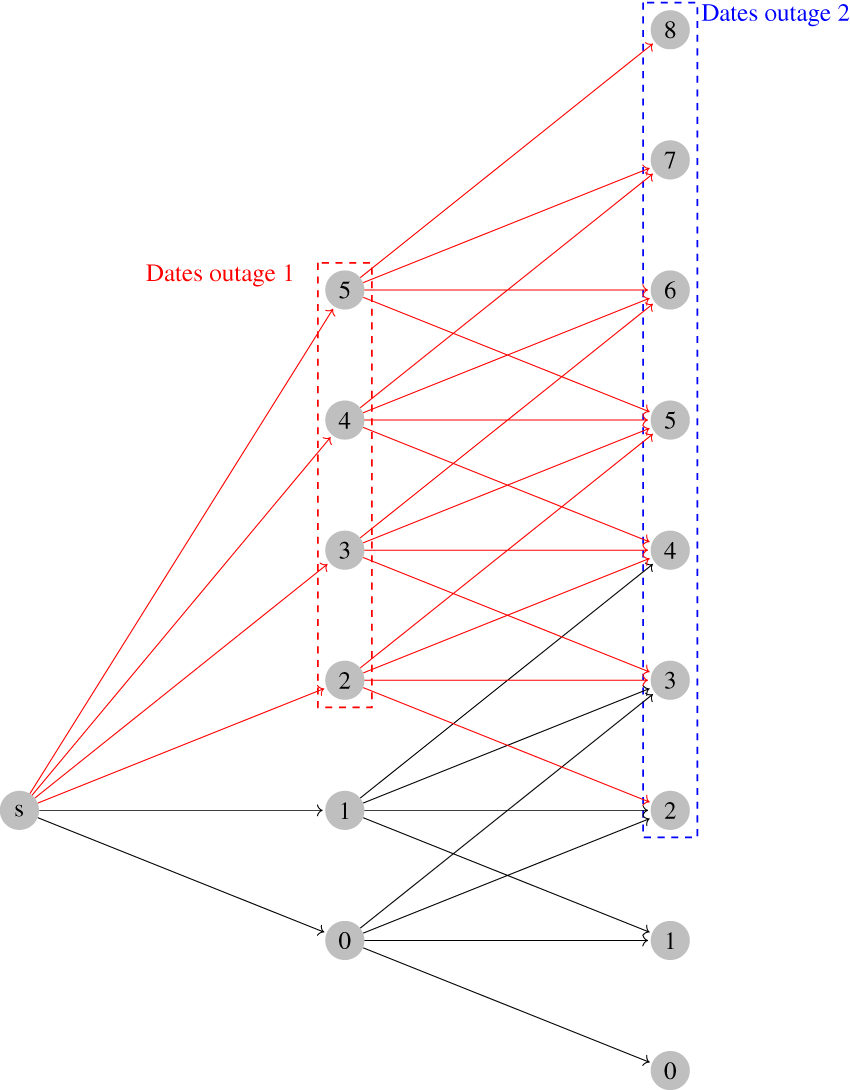

A complete simplified problem instance with

Note that only Assumption 3 is strictly necessary to enable the embedding of fuel constraints into a graph structure. Assumptions 1 and 2 are introduced to simplify the presentation of our approach, but could be relaxed at the cost of increased circuit complexity, requiring a higher number of qubits and quantum gates.

4 Direct Quantum Search Approach

This section describes the direct quantum search tailored to the simplified use case.

The first step of a quantum search is to define an encoding scheme that maps problem solutions to quantum states.

Different units have different initial fuel levels denoted by

Figure 2: Shifted labels two units with an offset of two

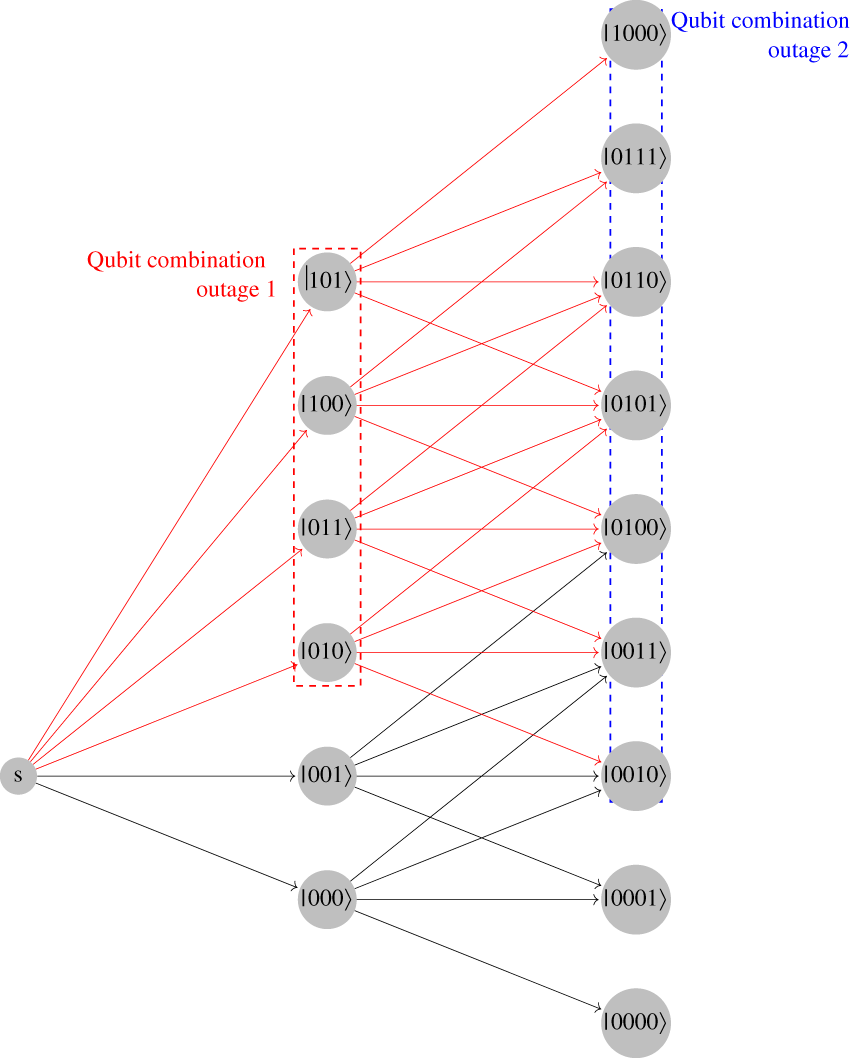

Fig. 3 replaces node labels of Fig. 2 with their equivalent qubit combination.

Figure 3: Qubit combination corresponding to the configuration of Fig. 2

Once we have defined the encoding, the idea is to apply a quantum search algorithm to generate feasible solutions to our planning problem. The textbook quantum search algorithm starts by putting the system in a superposition of all possible qubit combinations by applying a Hadamard gate to each qubit. Then, we need to define an oracle circuit which will mark qubit combinations that respect the following constraints:

• Outage dates respect fuel level constraints.

• Resource constraints between outages.

As fuel level constraints are local on each unit we can define an oracle which checks whether a given unit planning respects those constraints and combine the result on a unique flag qubit at the end of the circuit. This circuit takes

As this kind of operation was not natively supported by Qiskit when we started the project, Appendix A details how we set a flag qubit to encode the comparison statements

At this point, we have two flag qubits whose states encode the truth value of the statements

An alternative (more illustrative) approach would use all of the flag qubits as a control in a multi-controlled NOT gate which acts on yet another “ultimate” flag qubit. The state of this flag qubit would then encode the truth value of all the time windows and spacing constraints. The oracle would then just need to apply a phase gate on this one qubit.

This circuit uses

Resource constraints bring additional limitations for outages of the same index

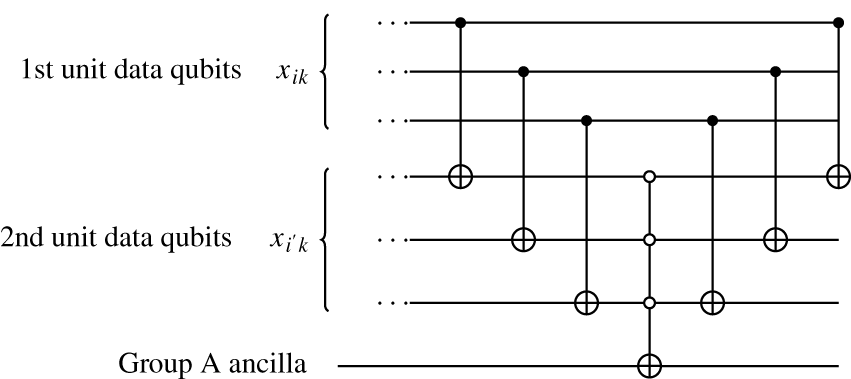

For each resource constraint concerning units

Figure 4: The circuit showing how each ancilla qubit in group A is set up using the data qubits

As a last step, we apply a multi-controlled NOT gate, controlled by all the ancillas in group A being in the

Figure 5: The quantum circuit showing how ancilla B is acted on controlled by ancillas A

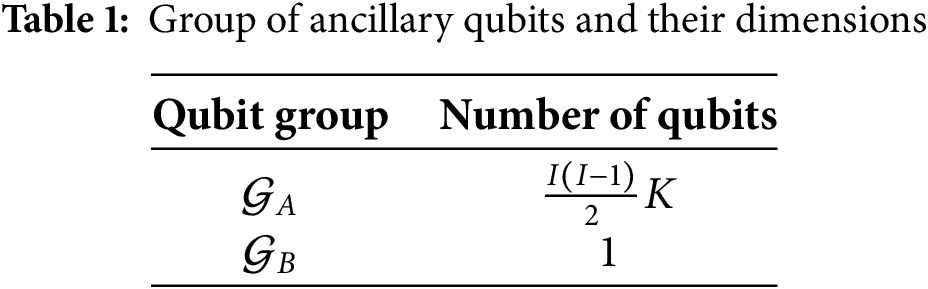

From the above we can see that the qubit requirements only grow quadratically with the number of machines and slightly more than linearly with the number of time steps, namely

The amplitude amplification algorithm selectively amplifies the states with the flag qubit set to

Here,

where

Standard amplitude amplification is only applicable when the proportion of valid solutions—i.e., the number of basis states satisfying the oracle constraints—is known precisely. In our case, since this proportion is unknown, we employ fixed-point amplitude amplification, which converges regardless of the number of valid solutions [12]. Specifically, if there are M valid states among N total basis states, standard amplitude amplification requires exactly

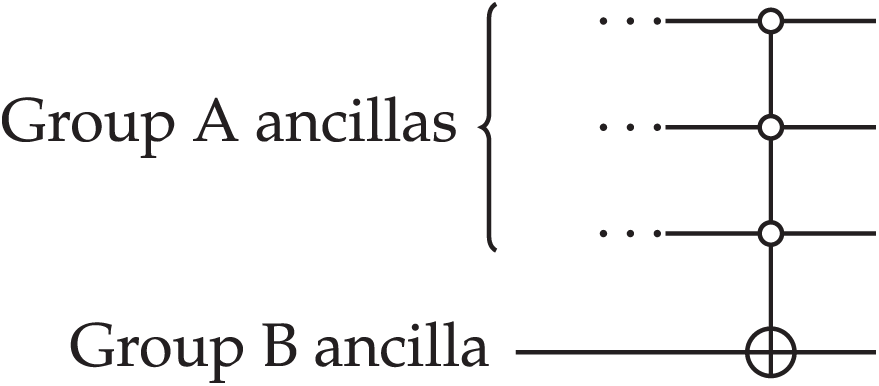

As discussed in Section 4, quantum search provides a theoretical quadratic speedup for exploring an unstructured solution space. However, the number of iterations required by a quantum search algorithm depends on the ratio between the total number of possible qubit configurations and the number of valid solutions. In the simplified use case without offset Section 3.3, the full search space has size

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

We observe that the expected number of iterations increases exponentially with both the number of outages (Fig. 6) and the number of units (Fig. 7), making exhaustive quantum search infeasible for large instances. This exponential growth arises from the ratio N/M, where N is the total number of possible qubit combinations and M is the number of valid solutions. Even in the simplified use case considered here—featuring fixed outage durations, unit resource capacities, disjoint time windows, and only two units—the ratio N/M grows rapidly with11 the problem size. This suggests that the theoretical quadratic speedup offered by Grover’s algorithm is insufficient to make full-space search practical, even for relatively small instances.

To address this limitation, the next section introduces an improved quantum search strategy. Instead of initializing the algorithm with a uniform superposition over the entire state space, we construct a reduced superposition that includes only those qubit combinations satisfying time window and spacing constraints. This state-space reduction significantly decreases the ratio N/M, thereby reducing the number of required Grover iterations and enabling more scalable quantum search for realistic problem instances.

5 Quantum Walk Inspired State-Space Reduction Exploiting Regular State-Graph Structure

In classical operations research, exploiting problem structure is a key strategy for improving tractability. Techniques such as extended formulations and dynamic programming on networks allow for efficient representations of complex polytopes. These methods are particularly effective when a subset of constraints induces a structured solution space. Quantum search algorithms, as previously discussed, begin with an initial superposition of states and use an oracle to mark “good” solutions. The algorithm then amplifies the amplitudes of these marked states through iterative rotations. The efficiency of this process depends on the initial ratio of good to bad states: a higher ratio leads to fewer iterations and faster convergence. In this section, we introduce a method to increase this ratio by constructing an initial superposition that reflects the structure of a subset of constraints. Specifically, when the feasible solution space corresponds to paths in an oriented rooted graph, we use a quantum-walk-inspired mechanism to generate a superposition over only feasible states. This approach embeds constraint satisfaction directly into the initial state preparation, reducing the search space before Grover’s algorithm is applied. This strategy represents a departure from prior work, which typically assumes uniform superpositions and handles constraint satisfaction entirely within the oracle. By integrating constraint-driven state-space reduction (SSR) into the initialization phase, we enable a more scalable and targeted quantum search. The novelty of our approach lies in explicitly leveraging the structured/unstructured decomposition of the problem to guide quantum state preparation—a concept inspired by classical decomposition techniques such as column generation, but adapted to the quantum context for the first time.

5.1 Introduction to Quantum Random Walks

A quantum walk is a straightforward generalization of a classical random walk, consisting of discrete steps. In each step, the “walker” randomly chooses a step to take from a set of possible steps in a structured space, which in our case corresponds to the rooted directed graph shown in Fig. 1. At each step, the walker is located at one of the nodes of the graph, and the set of possible steps corresponds to the outgoing edges of that node. An edge is randomly selected, and the walker moves along the edge to the neighboring node. Since the position of the walker is random, it can be expressed as a probability distribution.

In a quantum random walk (QRW) [13], instead of randomly choosing a step, the walker takes a superposition of all available steps. Therefore, the position of the walker is not represented by a probability distribution but by a superposition of quantum states. A quantum walk is described by a quantum state that evolves under both a unitary operator (representing the “coin flip” step) and a conditional shift operator (representing the movement of the walker). Although classical random walks use probabilities to describe the likelihood of transitions between states, QRWs use quantum amplitudes to govern the spread of the walker’s quantum state over the space. This kind of approach comprises the following components:

• Coin Flip Operator (

where

• Shift Operator (

where

Consequently, the Hilbert space of the system is given by the product of the coin and shift Hilbert spaces:

The evolution of the walker’s state is induced by the global evolution unitary operator acting on the state:

In the present study, we use an approach inspired by the above quantum walk method to construct the superposition of feasible states. The walker moves through the graph of possible outages, respecting the refueling constraints of the units. The quantum walk is not used to find the best solution, but merely to construct a superposition of all feasible outage schedules for each unit separately.

5.2 Quantum-Walk-Inspired State Space Reduction

As discussed in the previous sections, quantum random walks (QRWs) facilitate the construction of a superposition of states within a graph-like structure, specifically a tree in our case. Our work exploits this technique to build a superposition of paths within the network that correspond to feasible schedules for a set of machines, subject to operational constraints such as time windows and spacing. This is accomplished by allowing the QRW to explore the corresponding space of paths on the tree, with each new step performed on new qubit data.

This algorithm, called Feasible Path Algorithm, will act as follows:

1. Each set of data qubits represents the state associated with a given unit. The walk starts by the initialization of the system with

Now, each step of the quantum walk corresponds to a decision or transition between possible scheduling choices of a single or multiple units.

2. We iteratively apply the quantum-walk-based scheme on all qubits associated with outage

(a) The coin operator (

(b) The shift operator (

After |K| steps, the walker has explored all paths of the graph and hence the data qubits are in superposition of all possible paths:

At this point, we have obtained a superposition of all possible paths, which can be used as an initial state for the amplitude amplification algorithm with the resource constraint oracle, as described in Section 3.2.

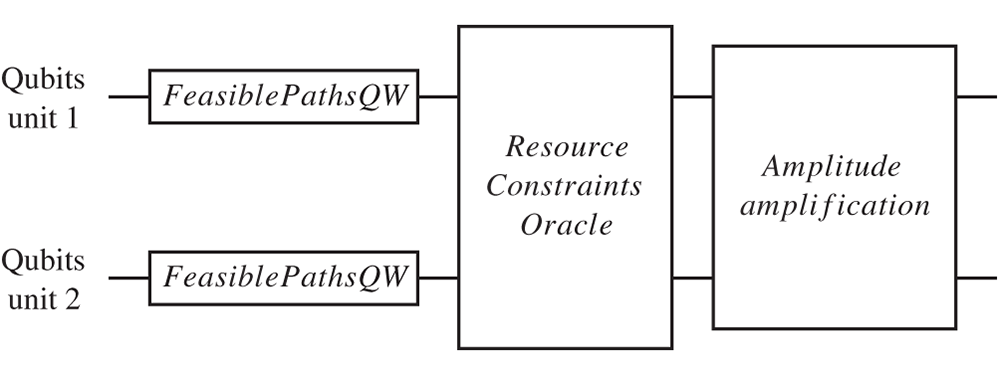

The method described above constitutes the initial phase of our approach to achieving a potentially enhanced quantum search speedup. First, we employ a quantum walk to explore the space of paths, introducing a path superposition that serves as the initial state for the quantum search. Notably, this new algorithm requires only the oracle for resource constraints and not the feasible path oracle anymore, since the initial state includes only elements that satisfy the fuel constraints. Fig. 8 shows the structure of the improved algorithm, where FeasiblePathsQW represents the initial state construction.

Figure 8: Structure of the reduced search algorithm based on the quantum walk based method described in Section 4.2

According to this algorithm, every step is performed onto different sets of qubits. Overall, to construct the feasible paths, we require only

5.3 Reduced Search Space Size Analysis on the Simplified Example

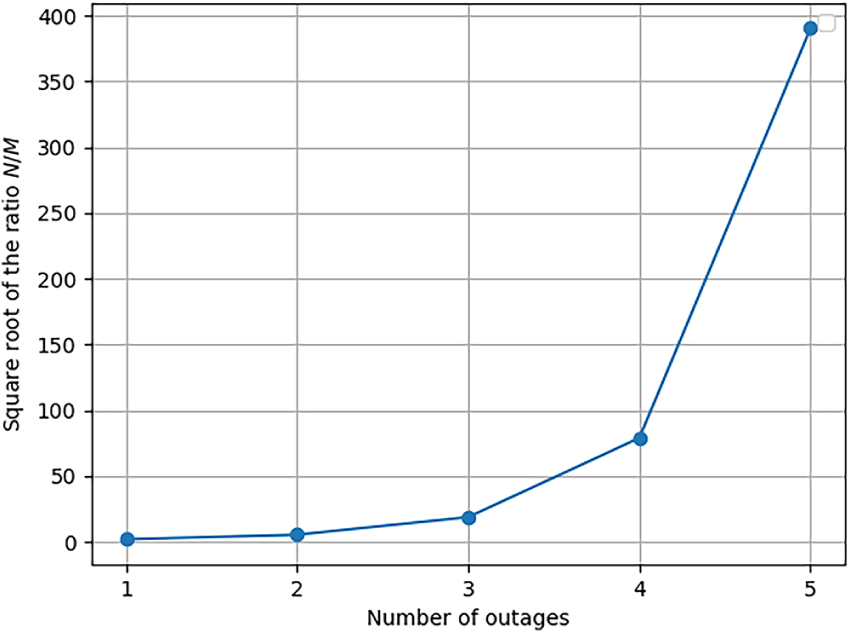

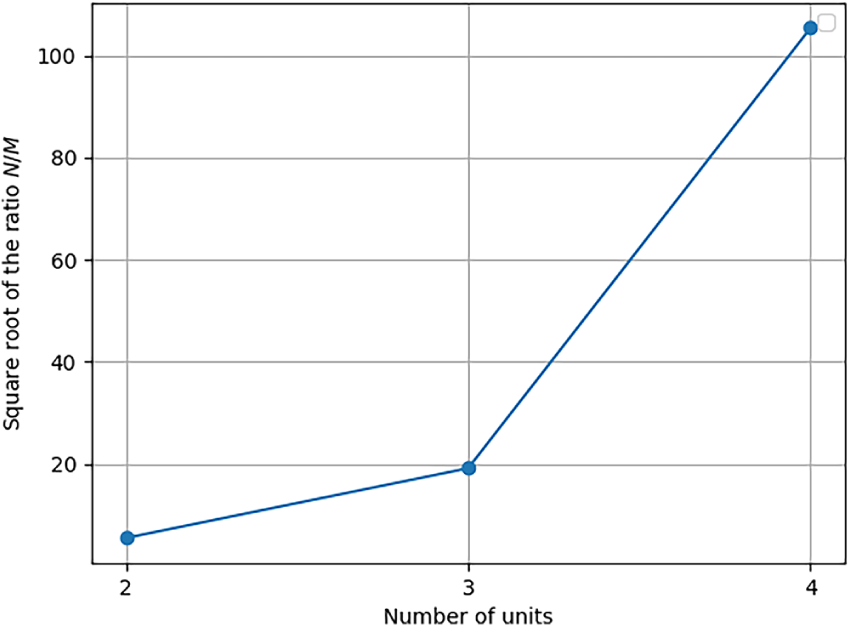

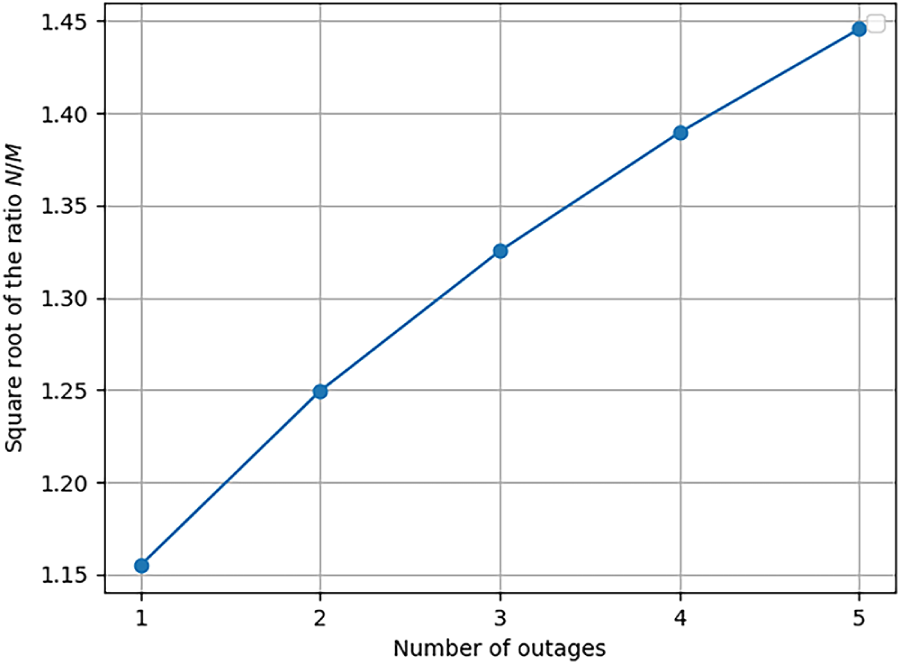

As in Section 4.3, we analyzed the square root ratio between the number of marked elements and the number of possibilities in the reduced search space for the simplified case of Section 3.3. The coin operator has a dimension equal to the number of accessible nodes from a given node, denoted by C. Therefore, the number of possible paths of length |K| in a single graph (i.e., the size of the reduced search space for one unit) is

Figure 9: Reduced space

Figure 10: Reduced space

6.1 Quantum Search Implementation

To demonstrate our algorithm, we build the corresponding quantum circuit in Qiskit 0.45.0 [14]. At the high level, the circuit is relatively simple:

1. From the problem description, calculate how many qubits are needed and initialize them (starting in

2. Put the qubits in the initial state for the search.

3. Apply the QSVT-based fixed point search.

4. Optionally, measure the state and check that the search was successful.

The main part of the circuit is the QSVT-based fixed point search. In essence, the fixed point search is alternating application of the two oracles with a custom list of phase angles, generated via the pyqsp Python package [9,15,16], applied to the marked states (not merely flipping the phase).

There are two sets of oracles: one for the naive quantum search described in Section 4 and the other for the state-space reduction approach presented in Section 5. In both cases, one oracle marks the initial state and the other oracle marks the good states. In the state-space-reduction approach, the initial state is built by a quantum-walk-like approach. Two qubits are used as a 4-state coin: in each time step, the state of qubits from the previous time step is coherently copied onto the current-time-step register and controlled by the coin qubits, it is incremented by +0/+1/+2/+3 in binary (using quantum arithmetic based on Fourier transform). Thus, an initial state is created, which consists of the coherent superposition of all feasible outage paths of all units. An oracle to mark this state is built by un-computing the initial state back to all-

For the approach without the state space reduction, the initial state is the standard superposition of all computational basis states (obtained by applying Hadamard gates to all the data qubits). The first oracle marks this state (by “uncomputing” the Hadamard gates and then marking the all

The fixed-point search algorithm needs to have a pre-defined number of iterations (which is also necessary to calculate the angles in pyqsp), but as long as this is large enough (see Section 2), we expect the final state to contain predominantly correct solutions. While there is already quantum hardware, with sufficient number of qubits to demonstrate a toy-sized version of our problem, the limiting factor is circuit depth. Repeated application of the QSVT oracles requires either error-corrected quantum HW (not yet available) or perfect quantum simulators, which is what we use in our experiment. The test has been performed on AMD Ryzen 5 PRO 5650U with Radeon Graphics 2.30 GHz and 16.0 Go of RAM.

6.2 Impact of the Search Space Reduction

In this section, we analyze the numerical improvement induced by the state space reduction circuit. As presented in [4], the fixed-point quantum search does not exhibit a monotonic improvement in the probability of finding a marked element. Instead, it has two phases: the probability first increases until it reaches 100%, then follows a pseudo-sinusoidal pattern with a minimum that depends on the settings of the fixed-point search.

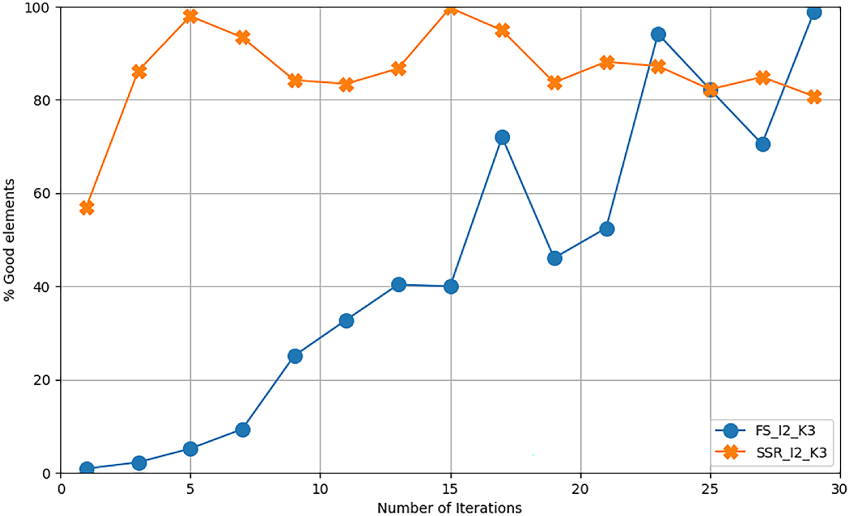

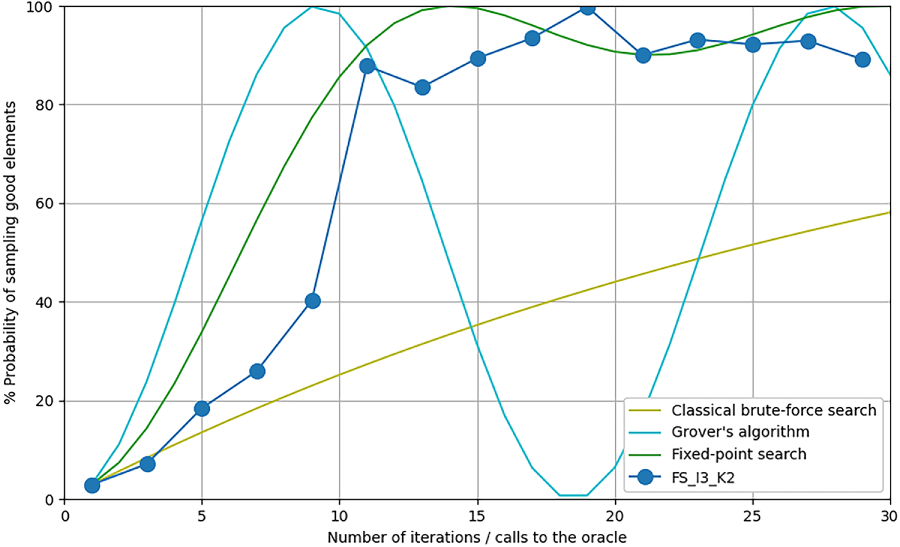

Fig. 11 compares the percentage of marked elements obtained depending on the number of iterations of the fixed-point quantum search for both the full search (FS_I2_K2) and the reduced search (SSR_I2_K2), using two units and two outages without offsets. As expected, both methods show an initial increasing phase followed by the pseudo-sinusoidal pattern. The percentage of marked elements is higher than 60% at the beginning for the reduced search and below 20% for the full search. The reduced search reaches a percentage of 99.16% of marked elements after only 5 iterations and then enters the pseudo-sinusoidal phase, with the percentage of marked elements never falling below 77% in subsequent iterations. In contrast, the full search requires 13 iterations to reach a percentage of marked elements greater than 99% and then enters the pseudo-sinusoidal phase. This result confirms the theoretical improvement induced by the state space reduction.

Figure 11: State space reduction impact: 2 units, 2 outages per unit

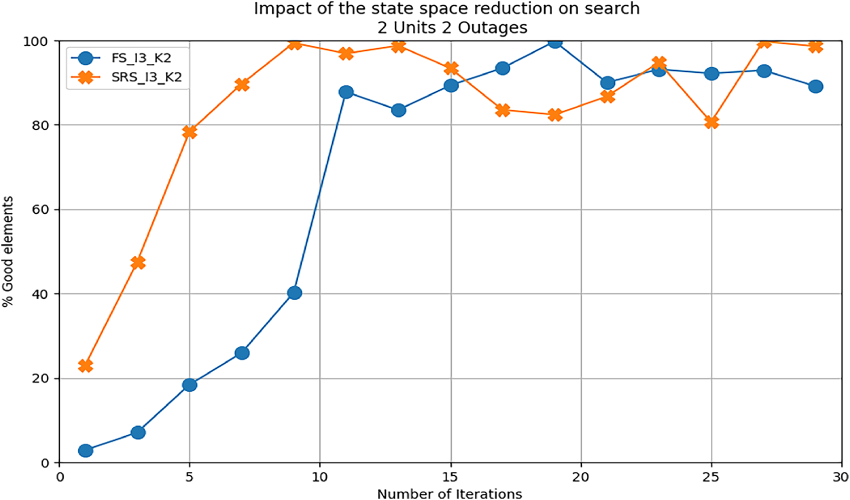

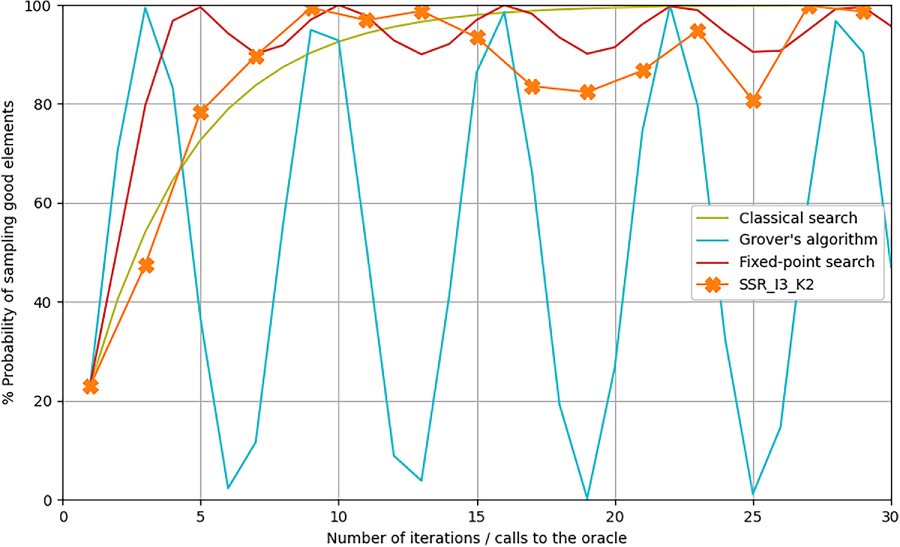

Figs. 12 and 13 respectively show the results for 2 machines with 3 outages and 3 machines with 2 outages using our approach. Due to emulator limitations, we could not extend beyond these values. As discussed in Sections 4.3 and 5.3, the square root ratio between the number of possibilities and the number of solutions increases linearly with the number of outages in the reduced search, while it increases exponentially in the full search. This is clearly illustrated in Fig. 12, where the full search space starts with a very low probability of finding good elements and requires 29 iterations to reach a probability higher than 99%. In contrast, the reduced search starts at approximately 57% and still reaches 99% in just 5 iterations.

Figure 12: State space reduction: 3 outages per units

Figure 13: State space reduction: 3 units with 2 outages per units

The impact of increasing the number of units (Fig. 13) is more challenging for the reduced search approach, as the search complexity increases exponentially. Here, a high probability of finding a solution is achieved after 9 iterations—still better than the full search approach, which takes twice this number of iterations to reach this value. While these results are based on small-scale instances due to current hardware limitations, they are intended as a proof of concept to illustrate the potential benefits of structure-aware initialization. We do not claim general conclusions, but rather aim to highlight promising trends that warrant further investigation on larger systems.

6.3 Quantitative Comparison with Theory and Error Analysis

In this section, we provide a detailed analysis of the discrepancy between our experimental results and the theoretical predictions of the quantum search algorithm. Fig. 14 compares the theoretical performance of the ideal fixed-point quantum search algorithm, as described in Eq. (1) of [4], for both the full search space (Fixed-Point Search, FS) and the reduced search space (State-Space Reduction, SSR), with our experimental data. Note that the fixed-point quantum search configuration represents a trade-off between rapid initial convergence and the threshold of the success probability during the oscillatory phase. The theoretical fixed-point algorithm exhibits a faster initial rise in success probability and reaches a higher threshold. Our experimental results generally follow the same trend but consistently fall below the theoretical curve. This discrepancy primarily arises from the suboptimal rotation angles used in the fixed-point algorithm. These angles are computed numerically using the pyqsp Python package, which may not always yield globally optimal parameters [15].

Figure 14: Comparison between experiments and theoritical behavior of the fixed point quantum search algorithm

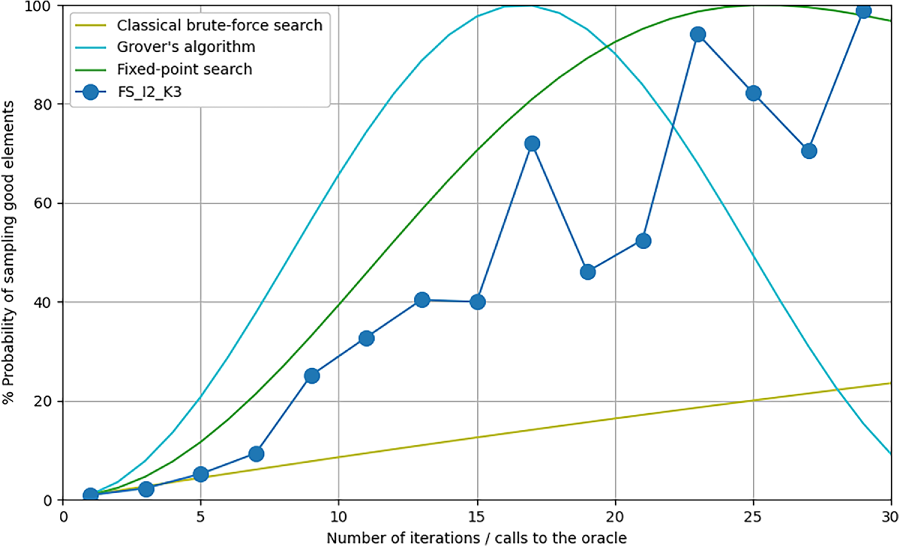

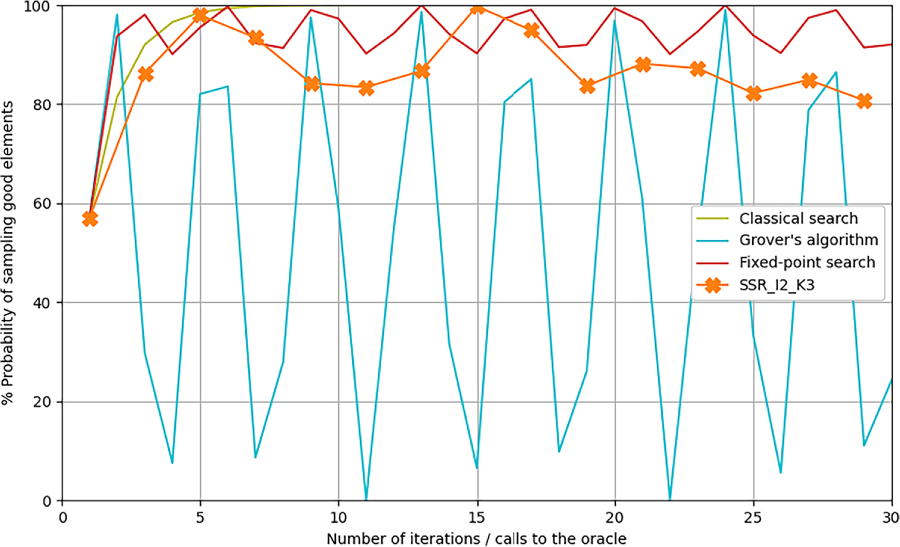

To further contextualize our results, we compare our experimental implementation against both classical and ideal quantum baselines. The first baseline is classical exhaustive search. In the full-space setting, this corresponds to brute-force evaluation over all possible bitstrings. In the reduced-space setting, it takes the form of a tree search constrained to the reduced search space. While computationally inefficient, these classical baselines provide reference points for understanding quantum speedup. We also include the theoretical performance of the standard Grover algorithm under the assumption of a known number of marked elements, assumption which is only feasible for toy instances considered here but not for real instances. Figs. 15 and 16 show this comparison for three units and two outages, while Figs. 17 and 18 illustrate the same for two units and three outages. In all cases, Grover’s algorithm achieves the steepest increase in success probability per iteration, but also exhibits the well-known oscillatory behavior that limits its applicability when the number of marked elements is unknown. In contrast, the fixed-point algorithm—both in theory and in our implementation—offers smoother and more stable convergence. Despite its slower rate, our implementation consistently outperforms classical exhaustive search, except in the specific case shown in Fig. 18, where the limited size of the reduced space enables the tree search to quickly find a solution. Notably, state-space reduction improves the performance of both Grover’s and fixed-point algorithms by increasing the proportion of marked states in the initial superposition. This leads to significantly faster convergence, as seen in both the theoretical and experimental results.

Figure 15: Comparison with theory: full space search with 3 units and 2 outages

Figure 16: Comparison with theory: state-space reduction search with 3 units and 2 outages

Figure 17: Comparison with theory: full space search with 2 units and 3 outages

Figure 18: Comparison with theory: state-space reduction search with 2 units and 3 outages

6.4 Potential Scaling up of the Approach

Our implementation serves as a proof of concept for state-space reduction techniques applied to a simplified scheduling problem. However, as mentioned in Section 3, it corresponds to a simplified model for outage planning problems of production units. To apply our approach to real-size industrial instances, we need to scale it up, which will require a number of qubits and a circuit depth that we currently cannot achieve on a quantum emulator. Here, we evaluate these future requirements for our approach. Note, however, that our circuit has not been designed to optimize circuit depth, which means it might be possible to reduce this depth by dedicated work on this aspect. We also assume that we can reset ancilla qubits during computation, which decreases the number of required qubits but increases the circuit depth.

An industrial instance will typically have the following range of values for the problem parameters:

• Number of units:

• Number of outages:

• Number of possibilities for anticipation:

• The maximum offset

In the following of this section, we will fix

The amount of qubits required by the full search space approach is:

• Data qubits:

• Ancilla qubits for resource constraints:

• Ancilla qubits for time constraints oracle:

Overall, for high values of |K| and |I| the number of ancilla qubits is dominated by the resource constraint one which gives the following formula for the amount of qubits:

The state-space reduction-based approach requires only

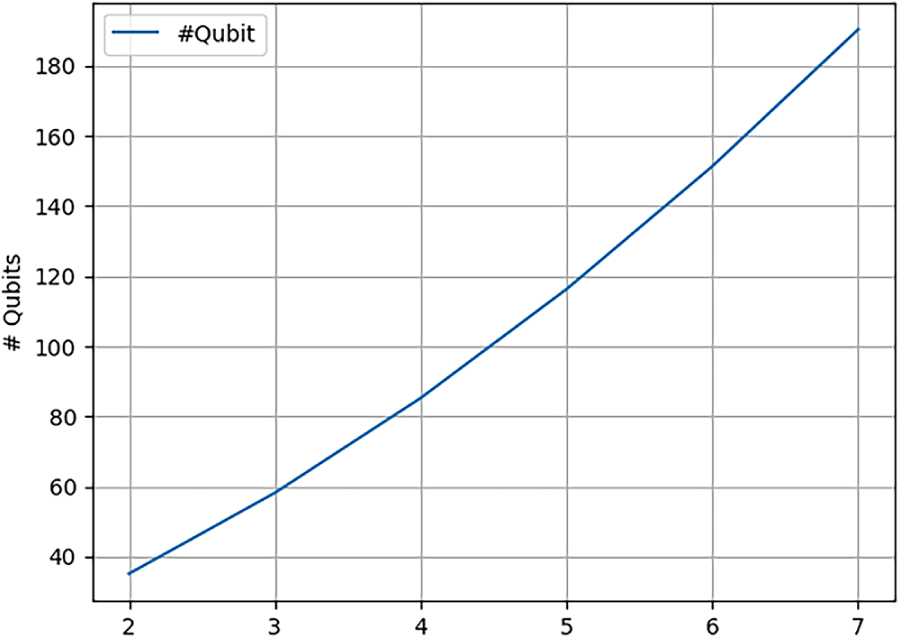

Figure 19: Qubit requirement for 2 to 8 units with 4 outages per unit

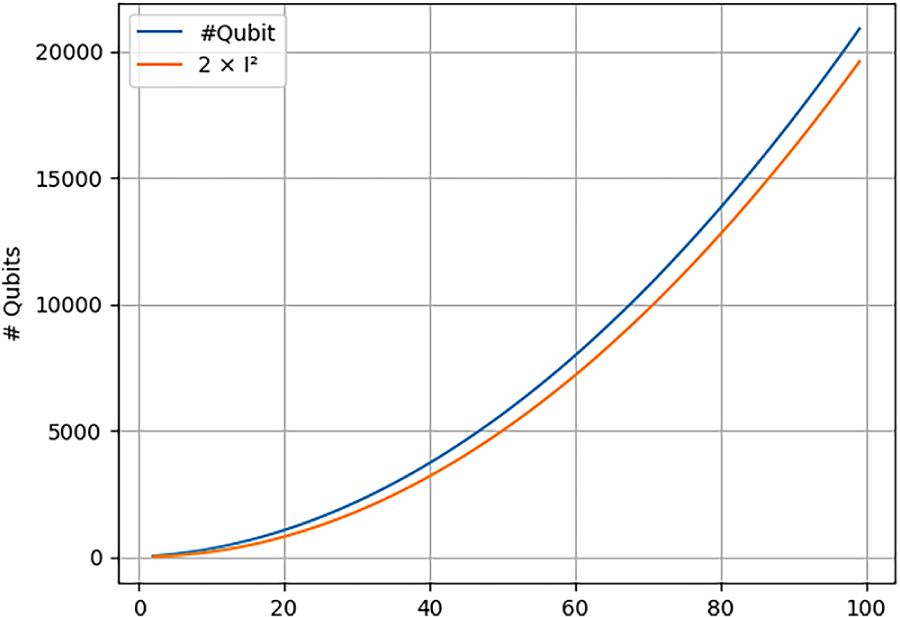

It is observed that 100 qubits are sufficient to solve instances with up to 4 units, which is the typical size for a single production geographical nuclear site, for instance. Two sites might be accounted for with approximately 230 qubits, while the French nuclear fleet—comprising 56 reactors—would require at least 6000 qubits. Fig. 20 extends the analysis to 100 units and compares it with the curve associated with

Figure 20: Evaluation of the number of required logical qubits for 4 outages by units, extrapolation to up to 100 units

The circuit depth analysis is more complex due to the potential future capabilities of quantum machines to natively implement advanced gates and the inherent challenge of optimizing quantum circuit depth, which can lead to high constants when circuits are not optimized. The depth of the fixed-point quantum search algorithm is primarily determined by the depth of the oracles, which is multiplied by the number of iterations of the algorithm.

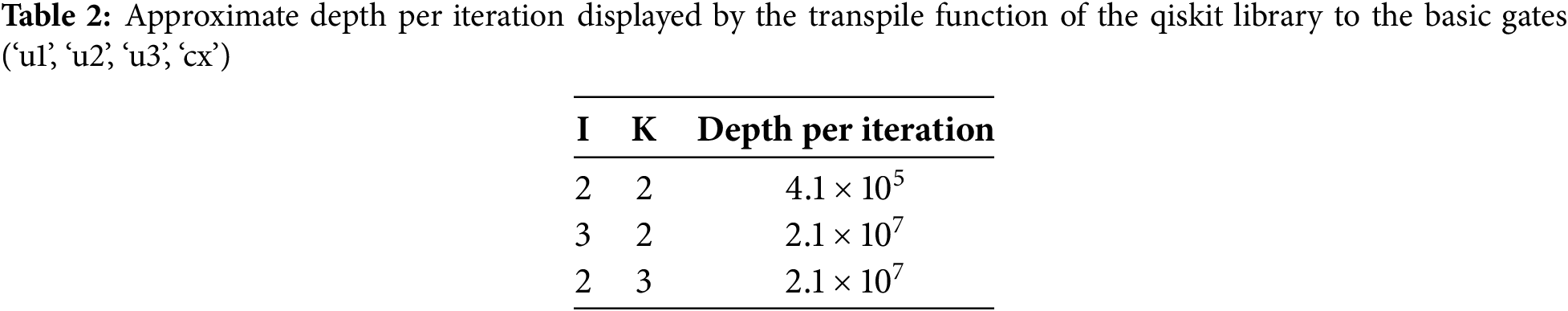

As mentioned in Section 4.2, the resource constraint oracle has a theoretical depth of

However, these asymptotic behaviors can obscure potential high-value constants in the circuit depth. Hence, we used the transpile function from the Qiskit library to compute the circuit depth associated with our previous experiments. This transpile function expresses our circuit in terms of the basic single-qubit gates (‘u1’, ‘u2’, ‘u3’) and the CNOT two-qubit gate (‘cx’). For more details, refer to the Qiskit documentation [14]. Table 2 shows the output of the transpile function, with values around forty thousand per iteration for 2 machines and 2 outages, and twenty million per iteration when we add one machine or one outage. These values far exceed the numbers given in the next 3-5 years in the public roadmaps of quantum computing companies.

These circuit depths almost certainly aren’t feasible without employing quantum error correction (QEC). QEC allows exponentially small gate errors (virtually no errors) at the cost of an overhead in the number of qubits, meaning that if we want to use a few hundred error-corrected qubits, the quantum computer will probably have to have a few tens of thousands of physical qubits. Quantum computers of that size do appear in the roadmaps of some quantum computing companies (in the 5–10 year range) [17–19]. While progress is hard to predict, recent results show rapid improvements in QEC [20–22].

This work explored the practical use of quantum search in the near future, assuming the availability of fault-tolerant quantum computers (FTQC). It was motivated by the observation that the quadratic speedup offered by Grover’s algorithm may not be sufficient in practice, as the ratio between the number of possible and valid solutions often grows exponentially with problem size in combinatorial optimization. However, since quantum search imposes no constraints on the initial state, it becomes relevant if one can exploit problem structure to construct an initial superposition where this ratio grows only polynomially. The proposed state-space reduction (SSR) approach leverages the structure of specific constraints to build a reduced initial superposition, while retaining quantum search for the unstructured part of the problem. We developed a proof of concept based on a quantum-walk-inspired algorithm to generate feasible solutions for a simplified outage planning problem—a specific scheduling problem where fuel level constraints induce a structure that can be efficiently embedded in a state graph. While quantum walks are typically used for search, our use of a quantum-walk-inspired mechanism serves a different purpose: it constructs a non-uniform initial superposition over feasible states. This allows us to encode feasibility directly into the quantum state, reducing the effective search space and enabling Grover’s algorithm to focus on the unstructured component of the problem. Our analysis of the search space, with and without SSR, and the numerical results obtained using a quantum emulator, highlight the potential of this approach. With a similar number of qubits, the reduced superposition grows only quadratically with the number of solutions, enabling fewer Grover iterations, shallower circuits, and improved scalability. Our implementation on a simplified use case using Qiskit demonstrated both the promise of SSR and the challenge posed by circuit depth in practical applications. Future work could extend this technique to more general scheduling problems or to cases where the state graph induced by fuel level management is more complex. In such harder problems, the generated pool of feasible solutions could serve as input to classical post-processing or expert analysis. Comparing SSR-based quantum search with classical methods would also be valuable. Finally, this approach could be generalized to other domains by adapting the quantum-walk-inspired initialization to different graph structures—such as those found in grid optimization or electric vehicle routing—where structural constraints can be exploited to reduce the search space. These extensions could pave the way for significant advances in solving real-world industrial problems.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the European project NEASQC.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme Grant Agreement No. 951821.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Rodolphe Griset; methodology, Rodolphe Griset, Ioannis Lavdas and Jiří Guth Jarkovský; software, Rodolphe Griset and Jiří Guth Jarkovský; validation, Rodolphe Griset; formal analysis, Rodolphe Griset; writing—original draft preparation, Rodolphe Griset, Ioannis Lavdas and Jiří Guth Jarkovský; writing—review and editing, Rodolphe Griset. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the articles.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A Comparing Numbers in Qiskit

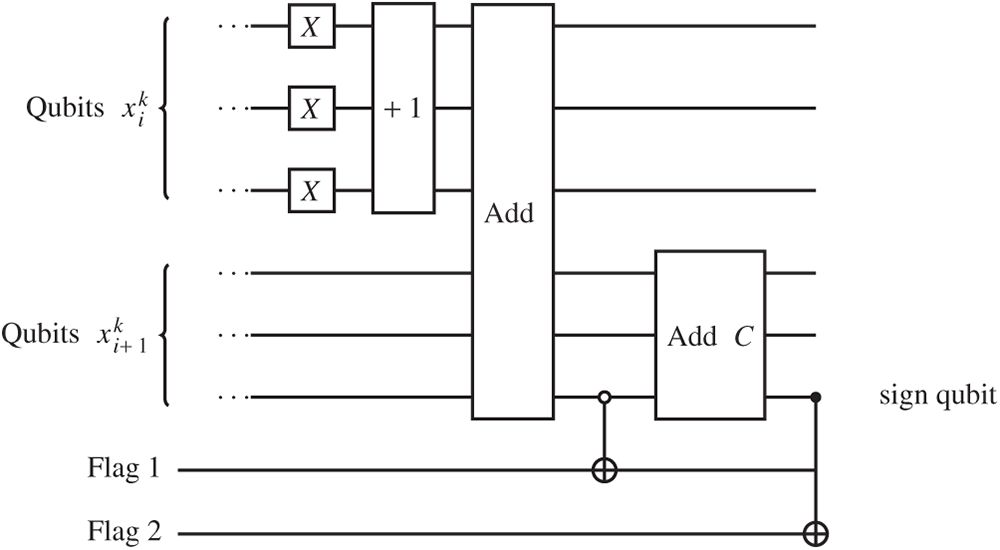

The version of Qiskit used in our implementation did not natively support subtraction operations. To work around this, we implemented subtraction using the two’s complement representation of binary numbers. In this representation, negative numbers are encoded by inverting all bits and adding one, using an additional (qu) bit to represent the sign. The sum of a number and its two’s complement yields zero due to overflow.

Let’s assume we want to check whether

We follow the steps below:

1. Compute the two’s complement of

(a) Invert all bits:

(b) Add 1:

So,

2. Add

3. Check the sign qubit (the overflow bit): it is 1, but the result

4. Compute the two’s complement of

(a) Invert all bits:

(b) Add 1:

So,

5. Add

6. Undo the transformations to restore the original values:

(a) Subtract

(b) Subtract

(c) Subtract 1 from

(d) Invert all bits of

In this example, we find that

The circuit showing steps 1–5 is depicted in Fig. A1.

Figure A1: The circuit showing the setup of the time windows constraint oracle

Appendix B The +1 Gate

The (+1)-gate, given by

where

Some simple examples can be seen below:

There are multiple possible implementations of the above operation. The one used in our case is implemented by a quantum Fourier transform (QFT), followed by a series of single-qubit rotation gates and then followed by another QFT. Implementing the QFTs before and after the rotations requires

Appendix C Feasible Paths Algorithm Application

In this appendix, we detail the practical implementation of the circuit representing the Feasible Paths (FP) algorithm introduced in Section 4, specifically for constructing quantum states in Qiskit. We focus on the case of a unit without offset, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

This circuit uses two ancilla qubits,

1. Copy the state of the data qubits

2. Apply Hadamard gates to the coin ancilla qubits

3. Apply the +1 gate to

4. Apply the +1 gate twice to

To illustrate this process, we consider the example of two outages with zero offset, as shown in Fig. 1. In this configuration, the first outage is encoded in the first two qubits of the initial multi-qubit state. We begin by applying Hadamard gates to these qubits to generate an equal superposition:

This superposition represents all possible paths from the source node, corresponding to the possible outage dates of the first outage set. We then apply the FP circuit to construct the full superposition of paths leading to the second outage set:

1. Apply two CNOT gates:

where

2. Apply Hadamard gates to

3. Apply the +1 gate to qubits

4. Apply the +1 gate twice to qubits

Each row in the resulting superposition corresponds to a set of feasible paths from a specific node in the first outage set to nodes in the second outage set. Each column represents the evolution of paths from different initial nodes. The ancillary qubits determine the control logic for path generation, while the state of qubits

1Common constraints include, for example, a fixed Hamming weight (number of qubits in the

2Alternatively

References

1. Grover LK. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In: Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing; 1996 May 22–24; Philadelphia, PA, USA. New York, NY, USA: ACM; 1996. p. 212–9. doi:10.1145/237814.237866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Brassard G. Searching a quantum phone book. Science. 1997;275(5300):627–8. doi:10.1126/science.275.5300.627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Brassard G, Hoyer P, Mosca M, Tapp A. Quantum amplitude amplification and estimation. Contemp Math. 2002;305:53–74. [Google Scholar]

4. Yoder TJ, Low GH, Chuang IL. Fixed-point quantum search with an optimal number of queries. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;113(21):210501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.210501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Farhi E, Goldstone J, Gutmann S. A quantum approximate optimization algorithm. arXiv:1411.4028. 2014. [Google Scholar]

6. Stuart H, Zhihui W, Bryan O’G, Eleanor GR, Davide V, Rupak B. From the quantum approximate optimization algorithm to a quantum alternating operator ansatz. Algorithms. 2019;12(2):34. doi:10.3390/a12020034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dam WV, Eldefrawy K, Genise N, Parham N. Quantum optimization heuristics with an application to knapsack problems. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE); 2021 Oct 17–22; Broomfield, CO, USA. p. 160–70. doi:10.1109/QCE52317.2021.00031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bennett CH, Bernstein E, Brassard G, Vazirani U. Strengths and weaknesses of quantum computing. SIAM J Comput. 1997;26(5):1510–23. doi:10.1137/S0097539796300933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Martyn JM, Rossi ZM, Tan AK, Chuang IL. Grand unification of quantum algorithms. PRX Quantum. 2021;2(4):040203. doi:10.1103/PRXQuantum.2.040203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu Y. Deleting a marked state in quantum database in a duality computing mode. Chin Sci Bull. 2013;58(24):2927–31. doi:10.1007/s11434-013-5925-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Griset R, Bendotti P, Detienne B, Porcheron M, Şen H, Vanderbeck F. Combining Dantzig-Wolfe and benders decompositions to solve a large-scale nuclear outage planning problem. Eur J Oper Res. 2022;298(3):1067–83. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2021.07.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gilyén A, Su Y, Low GH, Wiebe N. Quantum singular value transformation and beyond: exponential improvements for quantum matrix arithmetics. In: Proceedings of the 51st Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC ’19). New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2019. p. 193–204. doi:10.1145/3313276.3316366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kempe J. Quantum random walks: an introductory overview. Contemp Phys. 2003;44(4):307–27. doi:10.1080/00107151031000110776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Javadi-Abhari A, Treinish M, Krsulich K, Christopher JW, Lishman J, Gacon J, et al. Gambetta, quantum computing with qiskit. arXiv:2405.08810. 2024. [Google Scholar]

15. Chao R, Ding D, Gilyen A, Huang C, Szegedy M. Finding angles for quantum signal processing with machine precision. arXiv:2003.02831. 2020. [Google Scholar]

16. Dong Y, Meng X, Whaley KB, Lin L. Efficient phase-factor evaluation in quantum signal processing. Phys Rev A. 2021;103(4):041067. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.103.042419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gambetta J. IBM quantum roadmap [Online]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/roadmaps/quantum/. [Google Scholar]

18. Google Quantum AI Team, Google Quantum Computing Roadmap [Online]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 16]. Available from: https://quantumai.google/roadmap. [Google Scholar]

19. IQM Quantum Computers, IQM Development Roadmap [Online]. 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.meetiqm.com/technology/roadmap. [Google Scholar]

20. Paetznick A, Da Silva MP, Ryan-Anderson C, Bello-Rivas JM, Campora JP III, Chernoguzov A, et al. Demonstration of logical qubits and repeated error correction with better-than-physical error rates. arXiv:2404.02280. 2024. [Google Scholar]

21. Google Quantum AI Team. Quantum error correction below the surface code threshold. arXiv:2408.13687. 2024. [Google Scholar]

22. Eberhardt JN, Pereira FRF, Steffan V. Pruning qLDPC codes: towards bivariate bicycle codes with open boundary conditions. arXiv:2412.04181. 2024. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools