Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Effect of Alkalization Fiber on Mechanical, Microstructure, and Thermal Properties of Sugarcane Bagasse Fiber Reinforced PLA Biocomposite

1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Universitas Jember, Kampus Tegalboto, Jember, 68121, Indonesia

2 Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Chemical and Energy Engineering, University of Technology Malaysia, Johor Bahru, 81310, Malaysia

3 Centre for Advanced Composite Materials (CACM), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), Johor Bahru, 81310, Malaysia

4 Advanced Engineering Materials and Composite Research Centre (AEMC), Department of Mechanical and Manufacturing Engineering, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, 43400, Malaysia

5 Research Centre for Chemical Defence, Defence Research Institute (DRI), Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia, Kem Sungai Besi, Kuala Lumpur, 57000, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Mochamad Asrofi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Harnessing the Potential of Natural Fiber Composites: A Paradigm Shift Towards Sustainable Materials )

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 1979-1992. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0033

Received 07 February 2025; Accepted 12 May 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

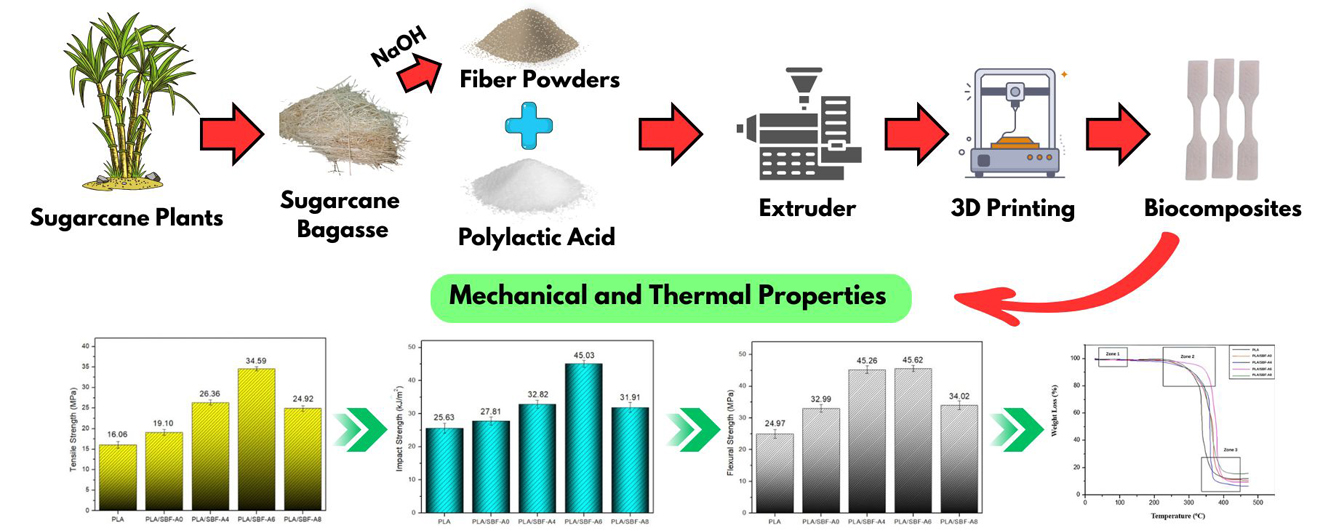

Biocomposites are one of the environmentally friendly materials as a substitute for synthetic plastics used for various applications in the automotive, household appliances industry, and interiors. In this study, biocomposites from Polylactic Acid (PLA) and sugarcane bagasse fibers (SBF) were made using the 3D Printing method. The effect of alkalization with NaOH of 0 (untreated), 4%, 6%, and 8% of the fibers were studied. The SBF in PLA was kept at 2% v/v from the total biocomposite. The characterization of all biocomposite tested using tensile, flexural, impact, scanning electron microscope (SEM), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR). The tensile test results showed that the 6% NaOH concentration on the fibers had the highest tensile strength of 34.59 MPa compared to pure PLA. The flexural and impact strengths of the biocomposite samples in the treatment also showed the highest results of 45.62 MPa and 45.03 kJ/m2, respectively. SEM imaging also confirmed the presence of good bonding between the matrix and fibers. The thermal stability of biocomposite showed an increase in the degradation point after alkalization. There was a change in the chemical functional group in the biocomposite with fibers treated by 6% NaOH at a wavenumber of 1150–1030 cm−1. These results indicate that PLA biocomposites have competitive properties for application in various industrial sectors.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

In today’s era, the use of plastic materials is necessary for various human activities, such as vehicle components, household appliances, interiors, and packaging [1–3]. However, plastics derived from petroleum (synthetic) have a negative impact on the environment due to their environmentally unfriendly nature [4]. One solution to replace synthetic plastic is the development of biocomposite materials.

Biocomposites are a combination of two or more materials, where one of the constituent elements is from nature. Generally, biocomposites are composed of a matrix as a binder and a filler as reinforcement [5]. In the last five years, PLA as a matrix in biocomposites has developed rapidly due to its environmentally friendly nature, abundant availability, and competitive mechanical properties compared to synthetic plastics [6,7]. However, pure PLA has disadvantages, such as low mechanical properties and poor thermal stability [8]. The presence of natural fibers is an alternative way to improve the weaknesses of pure PLA [9].

The addition of natural fibers into PLA has been reported by several previous researchers, such as hemp/flax [10], natural rubber/rice straw [11], and prosopis juliflora bark powder [12]. In their research, the solution casting method is a way to produce biocomposites. They reported that the addition of fibers into the matrix improves the mechanical and thermal properties of biocomposites. For example, PLA filled with 3% eucalyptus microfiber increases the tensile strength and thermal degradation point of the biocomposite [13]. However, the addition of natural fibers into the PLA matrix does not always improve the properties of the biocomposite. This occurs due to the poor surface interface bond between the matrix and the fibers. This phenomenon was observed in a study related to the PLA matrix and lemongrass filler [14].

The interfacial bond between the matrix and the fiber is the key to improving the properties of the biocomposite. Alkalization treatment with sodium hydroxide is one alternative to increase the surface adhesion between the matrix and reinforcement [15]. Several previous studies related to alkalization treatment on fibers have successfully improved the properties of biocomposites when combined with a PLA matrix. Previous reports related to the alkalization treatment on fibers and their biocomposites have been widely reported by several researchers [16,17]. Previous research reported that the preparation of betel leaf fiber using alkalization effectively increased the mechanical properties of PLA-based biocomposites. The comparison of these values was proven in PLA biocomposites from betel leaf fibers before and after alkalization with 3% filler loading, showing different values, namely 19.48 and 26.34 MPa, respectively. A similar case was also reported that alkalization treatment of sorghum bagasse increased interfacial bonding with PLA [18]. However, in previous studies, the fabrication process of the biocomposite used solution casting.

In this study, sugarcane bagasse fiber was subjected to alkalization and combined with the PLA matrix to become biocomposite filaments through extruder mixing. The resulting biocomposite filaments were used as 3D printing ink materials to make finished biocomposite products. Biocomposite products were tested for tensile, impact, flexural, microstructure, and thermal stability. To our knowledge, there has been no report on the study of PLA reinforced by alkalized sugarcane bagasse-based biocomposites that were processed by 3D printing.

This study used polylactic acid (PLA) in pellet form (density 1.25 g/cm3) produced by Indofilam, Indonesia as the matrix material. Sugarcane bagasse was obtained from traders around Jember, East Java, Indonesia. Bagasse fiber has a density value of 0.77 g/cm3 and a size of 177 microns.

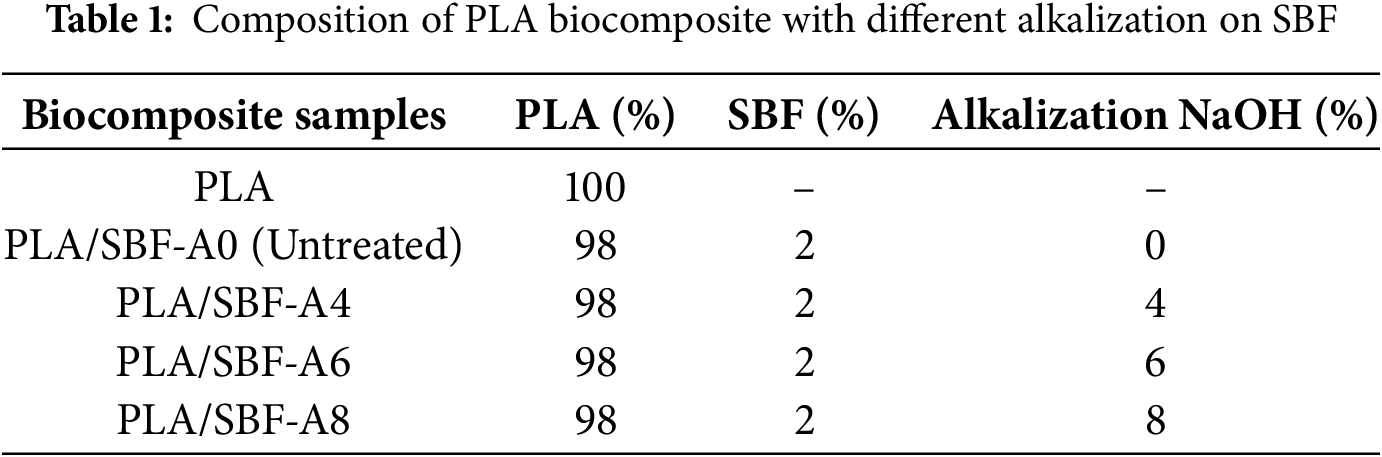

2.2 Preparation of Sugarcane Bagasse Fiber (SBF)

Sugarcane bagasse was dried in the sun for one week to reduce its water content. The dried sugarcane bagasse was ground with an ice blender to obtain powdered fiber. Next, the sugarcane bagasse fiber (SBF) was alkalized using NaOH solution with concentrations of 0% (untreated), 4%, 6%, and 8%. The SBF was then neutralized using distilled water until the pH reached 7. The SBF was dried in an oven at 60°C for 3 h. Finally, the SBF was filtered using a mesh sieve to achieve a more uniform size of approximately 177 microns.

2.3 Preparation of Biocomposite Filament

PLA and SBF were mixed manually in a volume percentage of 98% PLA and 2% SBF. This composition was maintained in all biocomposites, and the difference was in the concentration of alkalization (Table 1). The biocomposite filament was prepared using a single-screw extruder (Wellzoom Type B, Shenzhen, China). The biocomposite mixture was fed into the extruder with parameters of 155°C, 25 rpm, and a nozzle diameter of 1.75 mm. Furthermore, the biocomposite filament was prepared as a 3D printing ink material.

2.4 Printing of Biocomposite Specimens

The finished biocomposite product was printed and adjusted to the ASTM D638 type 5 standard for tensile testing (63.50 mm × 9.53 mm × 3 mm) through a 3D printing machine (Creality Ender 3 V3, Shenzhen Creality 3D Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). In addition, the biocomposite products were also printed according to ASTM E23 and ASTM D790-17 standards for impact testing and flexural testing, respectively. The printing parameters of the biocomposite by 3D printing include nozzle diameter 0.8 mm, nozzle temperature 200°C, layer temperature 60°C, raster angle 0°, layer height 0.2 mm, printing speed 50 mm/s, and bulk density 100%. The scheme of the biocomposite manufacturing process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic of preparation SBF, filament making, and specimen printing of biocomposite

A 5 kN Tensilon Universal Testing Machine was used as the tensile test instrument. The tensile test specimens were 3D printed according to the ASTM D638 type V standard, and their thickness and width were measured at five points each in the gauge length region. The tensile test was conducted at a speed of 1 mm/min at room temperature.

Impact test specimens were formed according to the ASTM E23-12C standard using 3D printing machine tools. Tests were conducted using an impact testing machine at room temperature.

All specimens were prepared in accordance with ASTM D790 standards and tested by the three-point flexural method. Flexural tests were conducted to determine the properties of all biocomposites using a flexural testing machine.

2.5.4 Morphological Observation

The fracture morphology of all biocomposites tested was observed using a digital microscope and a scanning electron microscope (SEM) Hitachi SU-3500 with a magnification of 5000× at 5 kV voltage. The morphological structure was identified at the fracture point after the tensile test. Observations were made at room temperature.

2.5.5 Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

All samples were prepared with a weight of 5 mg to analyze the thermal stability. The test setup was carried out at 30–500°C with a heating rate of 10°C/min under nitrogen conditions.

2.5.6 Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR)

The chemical functional groups present within the analyzed samples were characterized utilizing a Perkin-Elmer Frontier FTIR spectrometer. Each sample was meticulously sectioned into films measuring 1 × 1 cm. Spectral data were collected across the wavenumber range of 4000–1000 cm−1.

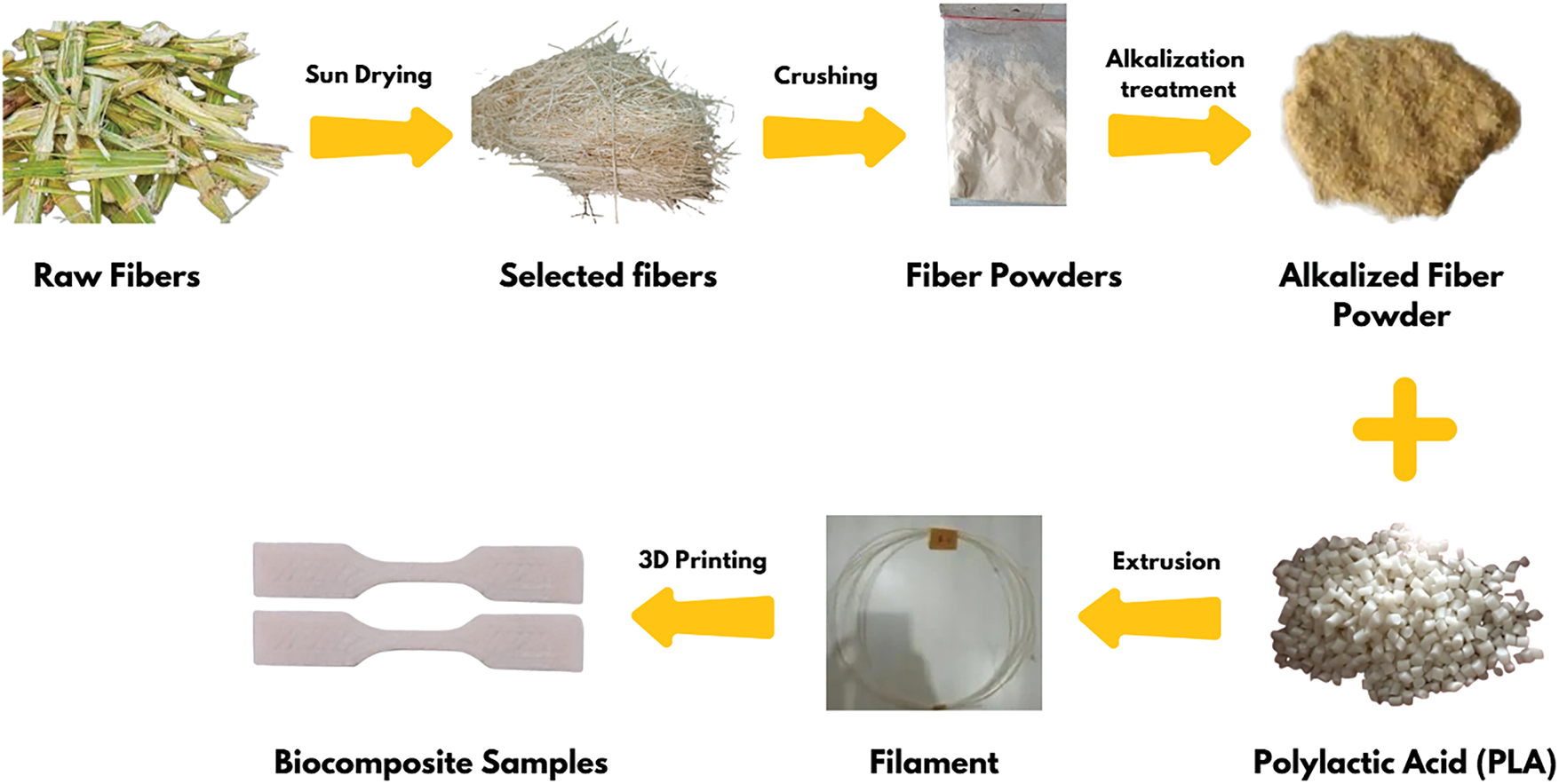

Fig. 2 shows the tensile results of PLA/SBF biocomposites with different alkalization treatments. The tensile strength of pure PLA increased from 16.06 to 34.59 MPa along with the increase in alkalization concentration to 6%. The increase occurred due to the well-formed interfacial bond between the fiber and PLA matrix. Good interfacial bonding between fiber and PLA matrix results in good compatibility and can increase tensile strength [19]. The role of alkalized fibers results in a cleaner and more reactive fiber surface, thus increasing the interaction between the fiber and the polymer matrix [20]. The results of this research are in accordance with previous research [19,20]. In SBF with 8% NaOH treatment, the tensile strength of the biocomposite decreased by 9.67 MPa compared to the 6% alkalization treatment on the fiber (Fig. 2a). This is because the high concentration of NaOH causes damage to the fiber [21]. Other factors contributing to the difference in tensile strength values are several defects such as cracks, debonding, and cavities in the matrix [22].

Figure 2: Tensile properties of all biocomposites tested: (a) Tensile strength; (b) Elongation at break

The addition of alkalization concentration to SBF increases the elongation at break (Fig. 2b), where pure PLA initially has an elongation of 3.23%, increasing to 13.12% (6% alkalized fiber) [23,24]. This phenomenon indicates good interfacial bonding of fiber and PLA, which results in increased ductility properties. However, in the 8% alkalization treatment, there was a decrease in elongation. This is due to excessive depolymerization of cellulose bonds [21,25].

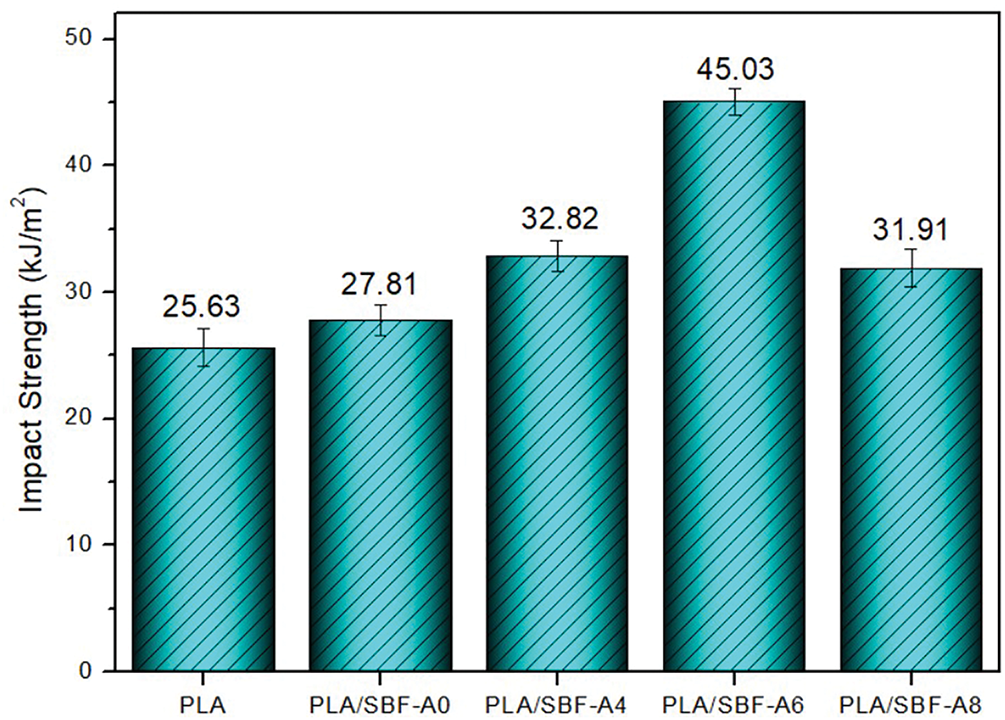

The impact test results can be seen in Fig. 3, where the impact strength of pure PLA was achieved at 25.63 kJ/m2. Increasing the concentration of alkalization showed an increasing trend in the biocomposite, namely 27.81, 32.87, and 45.03 kJ/m2 for fiber alkalization treatments of 0% (untreated), 4%, and 6%, respectively. The high impact strength is caused by good fiber and matrix interfacial bonding [26]. Increased impact strength occurs due to the role of fibres that undergo alkalization treatment. This results in a more reactive surface due to the reduction of lignin and hemicellulose layers, allowing the fibres to bond well with the PLA matrix [27]. This phenomenon is similar to previous studies [27,28]. These results are also in line with tensile strength.

Figure 3: Impact strength of biocomposite before and after alkalization treatment with different concentrations

However, a decrease in impact strength occurred in fibers with an 8% alkalization treatment, resulting in 31.91 kJ/m2. This occurs because the amount of sediment residue increases due to the increasing alkalization treatment on the fiber [26,29]. In addition, impact strength is also influenced by building direction, infill percentage, and layer height [30].

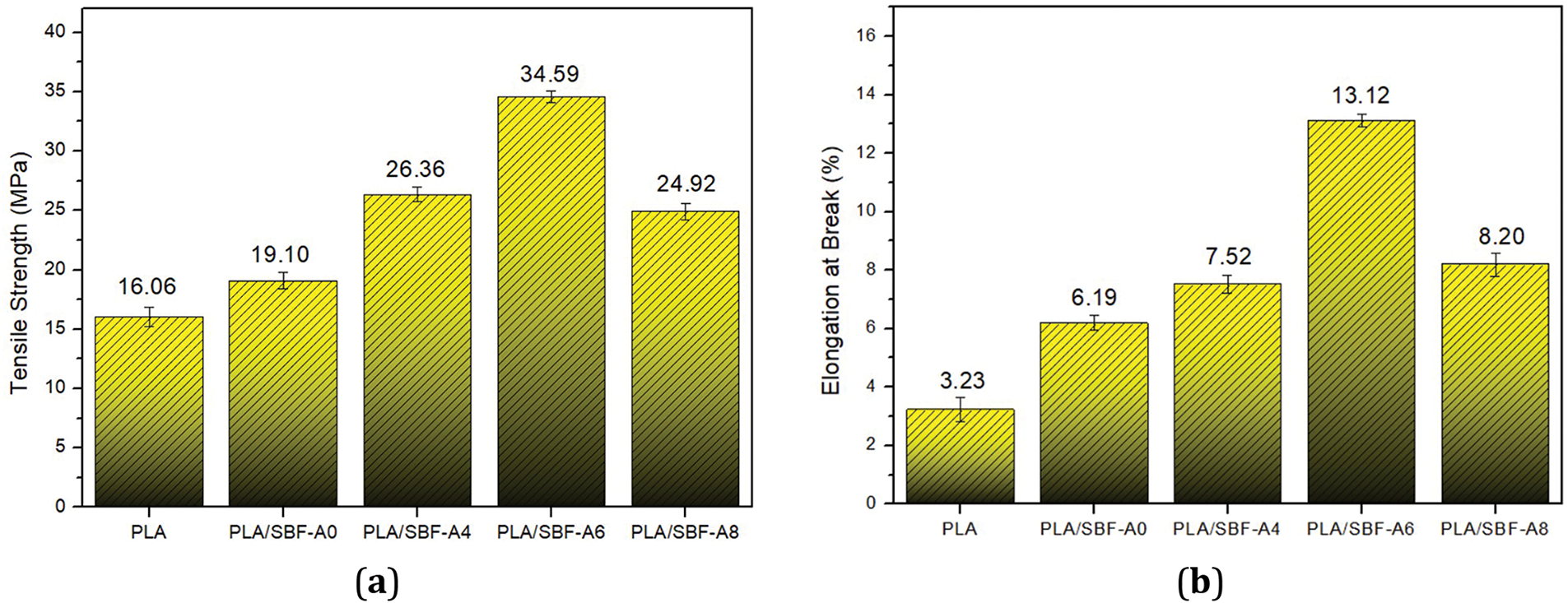

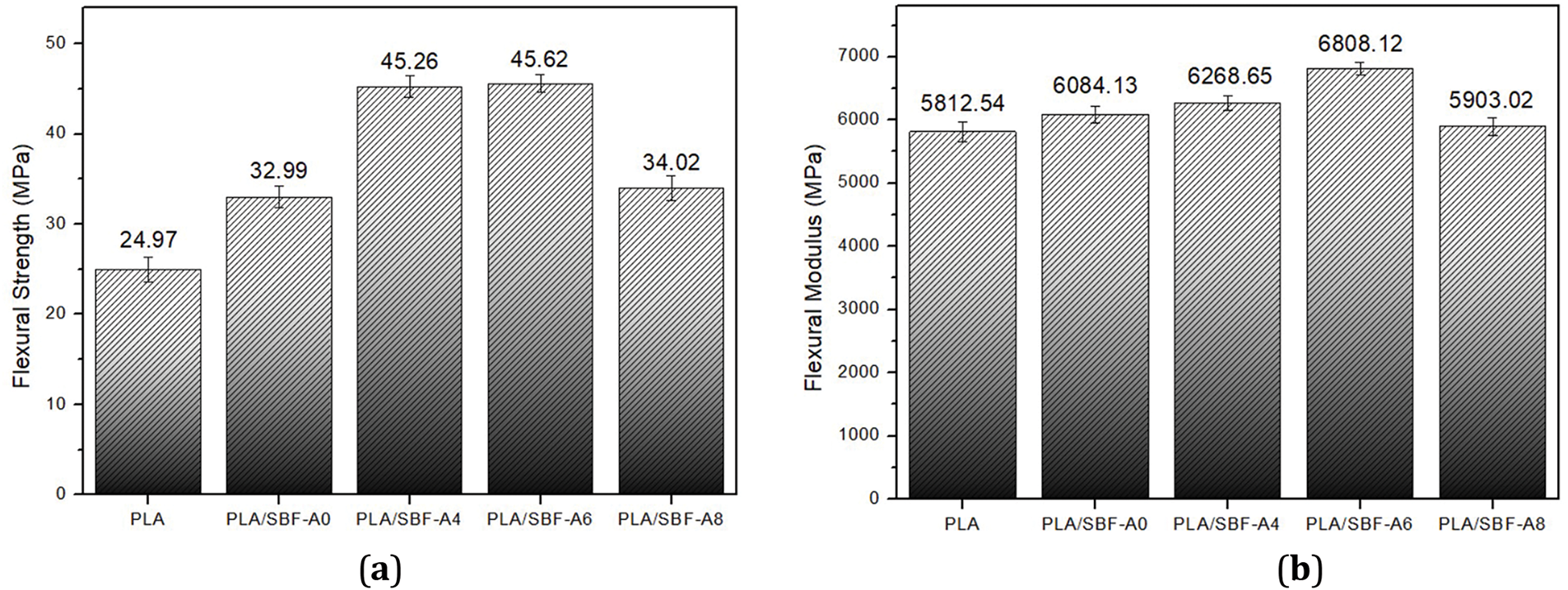

Fig. 4 shows the flexural strength of PLA/SBF biocomposites with different alkalization treatments. The flexural strength value of pure PLA is 24.97 MPa then increases to 32.99 MPa in PLA/SBF biocomposites (without alkalization treatment). This proves that the addition of SBF as a reinforcement increases the flexural strength of PLA. This phenomenon is similar to previous studies on PLA and hemp fiber biocomposites [31].

Figure 4: Flexural properties of all biocomposites tested: (a) Flexural strength; (b) Flexural modulus

The highest flexural strength value is found in the biocomposite with alkalization treatment on SBF of 6% at 45.62 MPa. The increase in value after alkalization is due to the release of lignin, hemicellulose, and wax content in the fibers, resulting in a more responsive surface when bonded to the matrix [32]. This is also supported by other studies that utilize coconut and pineapple fibers in the PLA matrix, which report similar results [33]. However, the flexural strength value decreased after fiber alkalization treatment by 8%. This decrease is due to the fibers being damaged from the high NaOH content. This damage results in a decrease in the mechanical properties of the biocomposite [27,34].

The flexural modulus produced the same upward trend as the flexural strength. The highest flexural modulus value was at the 6% alkalization treatment of the fibers, at 6808.12 MPa. Although the increase is not significantly different, it proves that the alkalization treatment of the fibers increases the elastic modulus of PLA [35]. Similar research reported an increase in the elastic modulus value with the addition of sisal, kenaf, and jute fibers in biocomposites [35].

The flexural modulus decreased at the highest alkalization variation of 8%, which was 5903.02 MPa, because there was porosity, indicating that the bond between the matrix and fiber was not good. This event can occur due to the influence of the alkalization treatment. The properties of the fibers produced after the alkalization treatment vary depending on the parameters used, such as processing temperature, solution concentration, and soaking time [32,36,37].

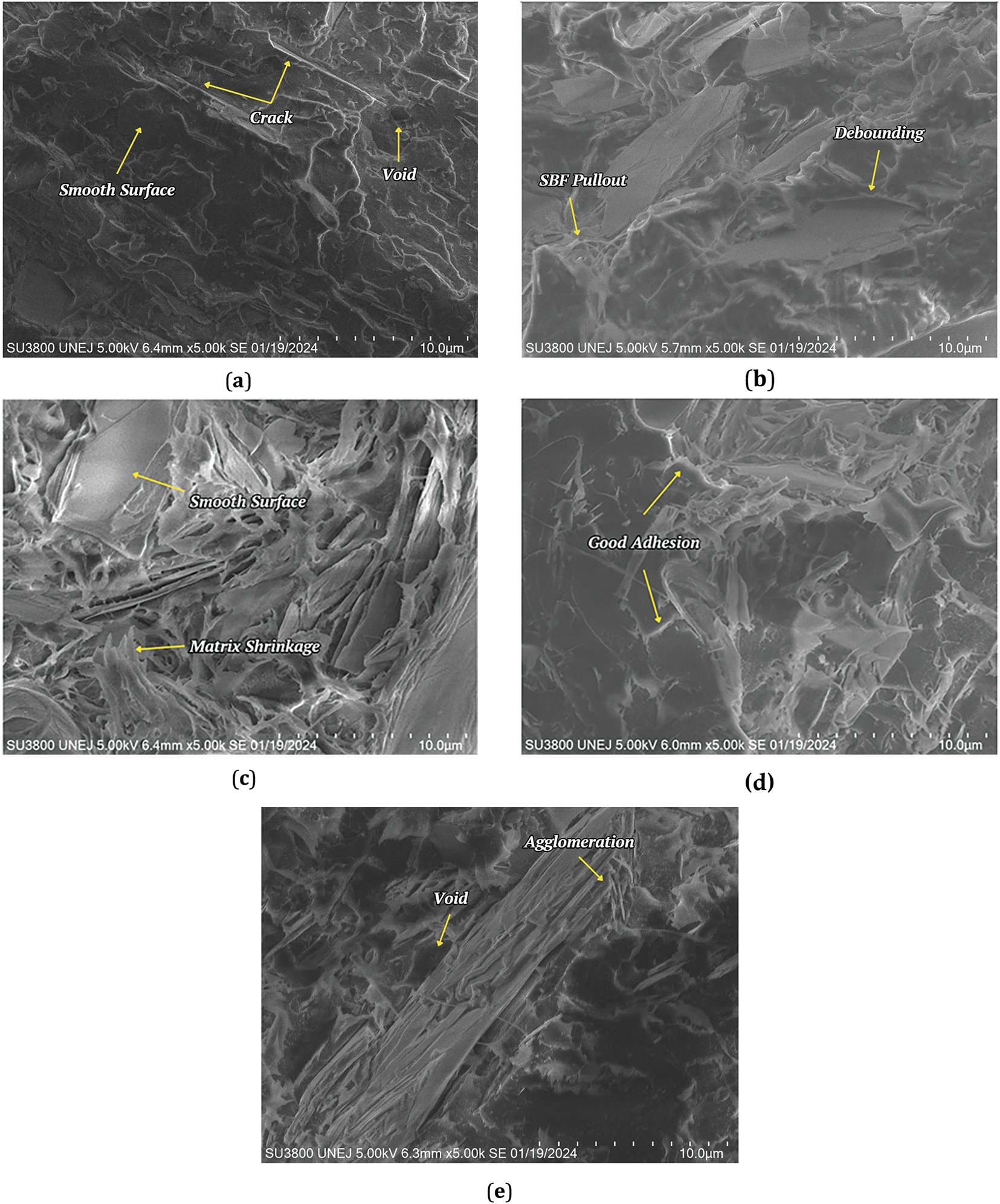

3.4 Fracture Morphology by SEM

Fig. 5a–e shows the results of the microstructure test on the fracture of the samples: pure PLA, PLA/SBF-A0, PLA/SBF-A4, PLA/SBF-A6, and PLA/SBF-A8. The surface of the pure PLA sample (Fig. 5a) looks more even and smoother [38,39]. This result confirms the morphology test with SEM and is similar to previous studies [40,41].

Figure 5: Fracture morphology by SEM: (a) PLA; (b) PLA/SBF-A0 (untreated); (c) PLA/SBF-A4; (d) PLA/SBF-A6; (e) PLA/SBF-A8

Fig. 5b (PLA/SBF without alkalization treatment) shows the failure of a matrix rich in fiber pull-out on the fracture surface. This matrix richness occurs because the amount of fiber used is insufficient and the fiber distribution in the composite is uneven. These results are in line with previous studies related to hybrid composites of hemp and sisal fibers [42]. Fig. 5c shows the fracture microstructure of the PLA biocomposite with sugarcane bagasse fiber that has undergone 4% alkalization treatment. From the figure, it can be seen that there is a shrinkage of the matrix (matrix-covered fibers) which indicates that the alkalization-treated fibers have a good bond with the matrix, thus requiring a greater force to pull the fibers out of the matrix [43]. However, with 4% NaOH treatment, there are still areas of smooth fracture surface. This indicates that there are still some areas in the sample that are dominated by the matrix without fibers, although there are not many of them. Meanwhile, Fig. 5d (SBF treatment with 6% alkalization) shows that PLA and SBF have a good bond that is dominant throughout the fracture surface. This is supported by the increased number of OH groups on the fiber surface after the alkalization process, so that the contact area with the matrix becomes larger [44]. Fig. 5e shows the rough fracture surface of the sample with voids, and agglomeration. Interestingly, there are no visible fibers pulled out on the fracture, even though the surface is predominantly rough. This is due to the brittle fibers resulting from the high alkalization treatment concentration. High alkalization concentrations can corrode fibers resulting in structural damage [45]. These findings confirm the cause of the decrease in mechanical properties that occurred.

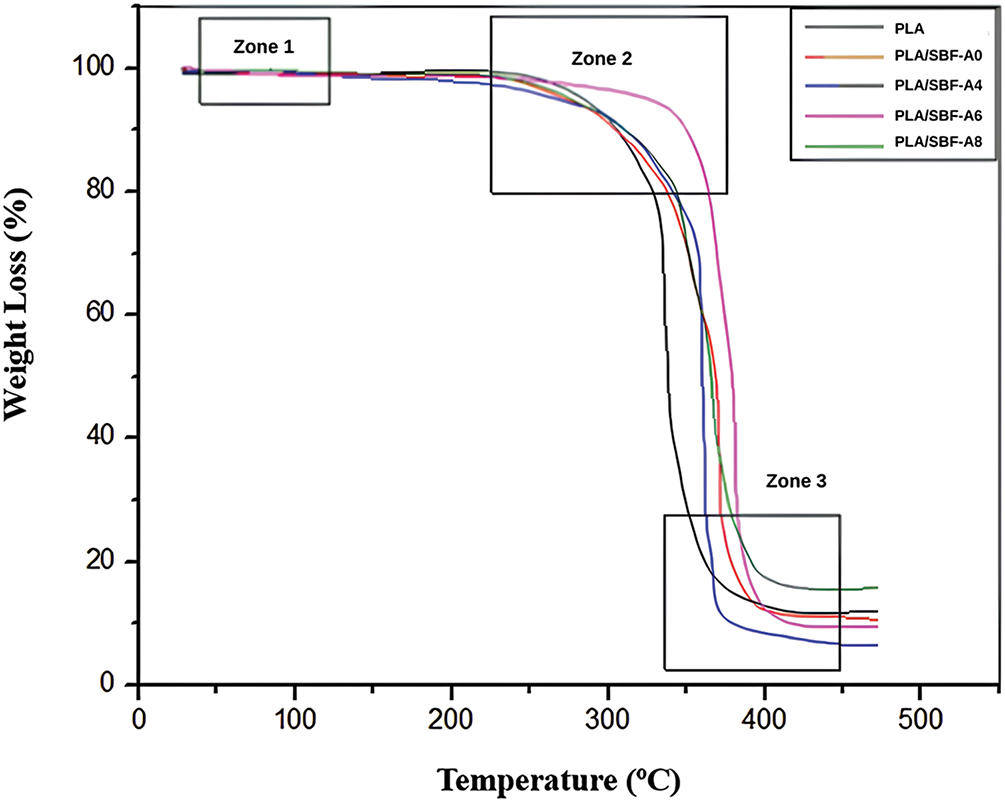

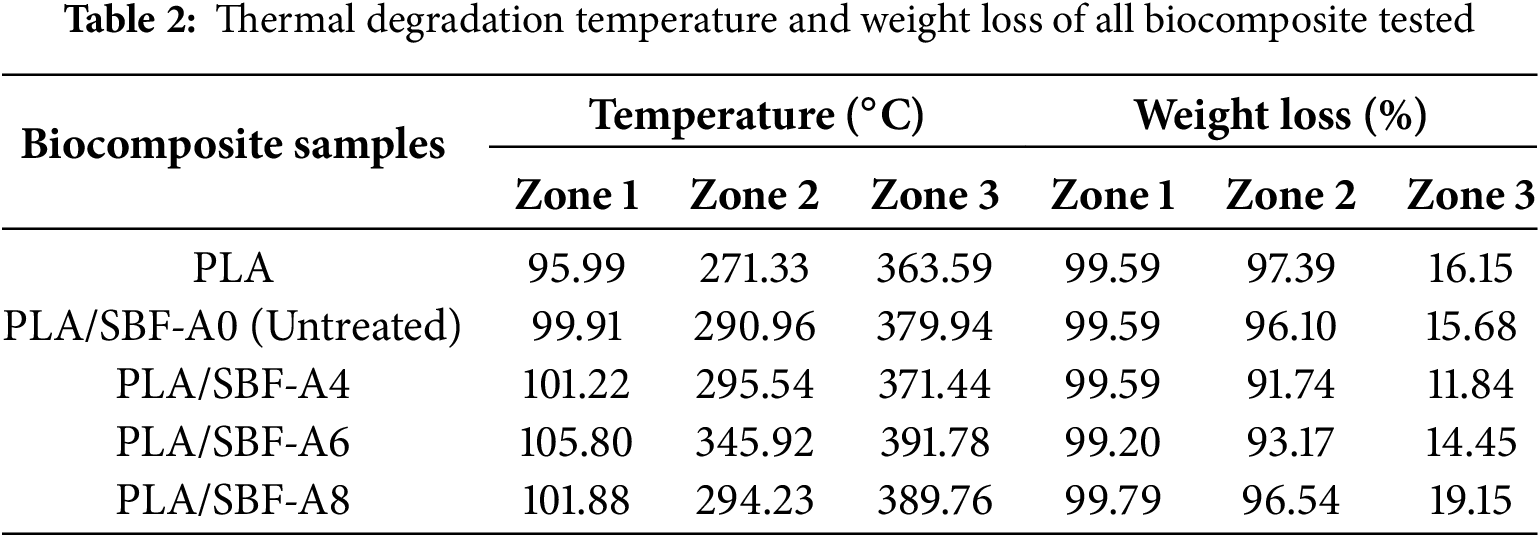

Fig. 6 shows the graph of TGA test results of PLA/SBF biocomposites. Zone 1 (95–105°C) shows minor mass reduction (1–5 wt%), and mass degradation is caused by the evaporation of moisture content in the biocomposite material [46]. This is evidenced by the decrease in mass percentage in the biocomposite material. In zone 2 (270–350°C), mass degradation will occur in all variations due to the loss of the main constituent components of biocomposites. The main constituent components are PLA [47] and SBF. There is an improvement in properties due to the addition of SBF to PLA. The initial temperature of structural degradation of PLA increased after alkalization SBF rather than PLA alone. PLA/SBF-A6 is the best in thermal stability as it can withstand a temperature of 345.92°C before undergoing significant mass degradation due to the evaporation of the biocomposite content from the polymer matrix and the inner structure of the fiber. In this case, the mass reduction between zone 2 to zone 3 reaches 85 wt%. The mass reduction from the thermal stability testing process is presented in Table 2.

Figure 6: Thermal stability of PLA and its biocomposites

Alkalization treatment improves the thermal stability of natural fibers by increasing the fiber surface content [48]. Another influencing factor is that lignin has higher thermal stability than cellulose because it acts as a barrier to fiber degradation due to environmental influences [49]. The thermal stability of PLA/SBF-A6 is also supported by good bending strength values due to the lignin content that is still present in the fiber. This causes the resulting biocomposite to be strong and have the best thermal stability. However, there are limitations to its properties, such as lack of elasticity and flexibility based on its elastic modulus and bending strain values. In zone 3 (360–390°C), significant mass degradation has occurred. This occurs because the main constituent components of the biocomposite have evaporated in the form of PLA matrix and cellulose structure in SBF, leaving residual substances such as charcoal and residue of 1–20 wt% of the total weight. The residues from the thermal degradation process are presented in Table 2. This finding is supported by previous studies [50–53].

3.6 Chemical Functional Groups Change

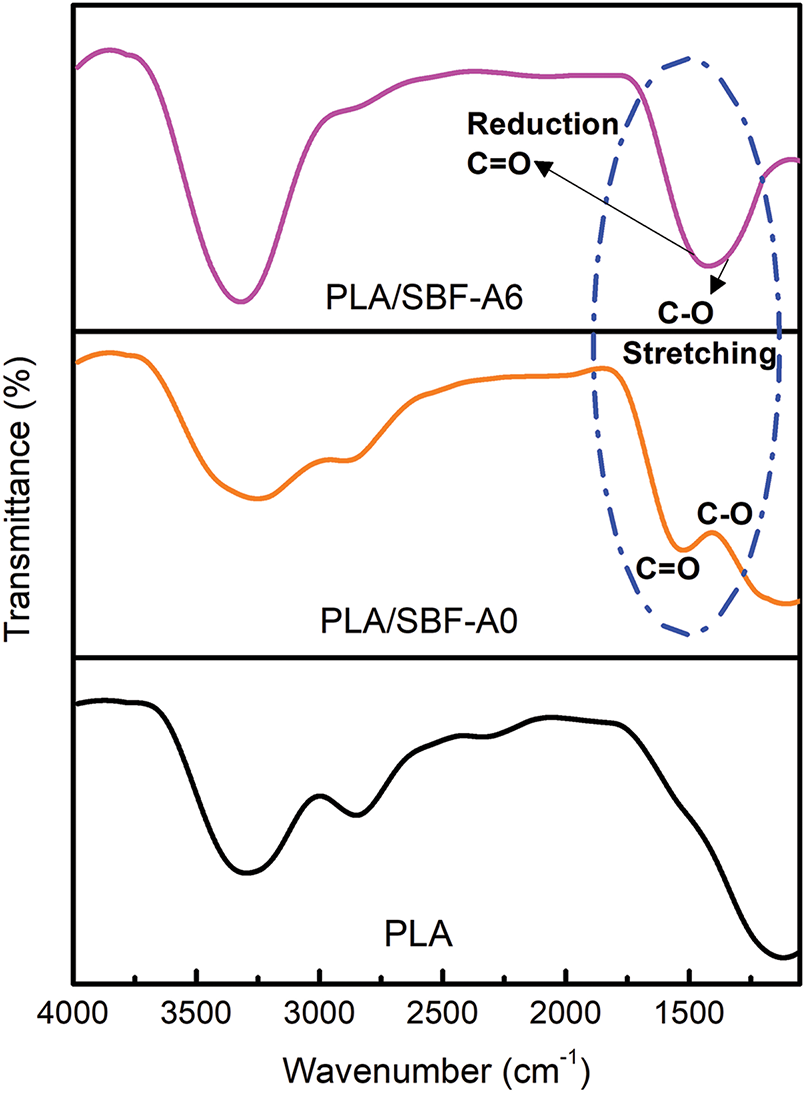

Fig. 7 shows the FTIR spectra of the biocomposite. The peak detected between 3500–3200 cm−1 indicates stretching vibrations of hydroxyl (OH) groups in the cellulose structure [54]. The peak at 2800–3000 cm−1 can be associated with stretching vibrations of the CH group [55]. The peaks at 1700 and 1650 cm−1 indicate stretching of the carboxyl and acetyl carbonyl groups of hemicellulose, respectively [56].

Figure 7: Chemical functional group changes of PLA and its biocomposite

The peak intensity decreases around 1750 to 1250 cm−1 (Fig. 7), which indicates the stretching of CO and C=O in hemicellulose, respectively. This phenomenon indicates a reduction in the hemicellulose content of the filler fiber (SBF) in the PLA matrix. Meanwhile, the peak around the range of 1150–1030 cm−1 indicates the removal of lignin content due to the influence of chemical treatment as shown by the stretching of C-O and C-H vibrations [57–59]. These results are similar to those discussed in previous studies where stretching of carboxylic acids and esters from hemicellulose occurs at a wave peak of around 1739 cm−1 (untreated) and disappears in treated fibers. On the other hand, the decrease in the C-O stretching peak indicates that fibers treated with alkali can retain cellulose that is purer from impurities such as lignin [60,61].

The addition of alkalization treatment on SBF increased tensile, impact, and flexural strength, with the highest values observed in the 6% NaOH treatment. This is due to the good bonding of the fiber and matrix interface. Meanwhile, 8% NaOH on SBF decreased the mechanical properties of the biocomposite because of fiber damage and excessive residue buildup on the surface. The morphological structure of the pure PLA biocomposite fracture shows a smooth and flat (homogeneous) surface. PLA/SBF biocomposites without alkalization treatment exhibited debonding between fibers and the matrix, as well as matrix-rich and fiber pull-out failures on the fracture surface. Alkalization-treated fibers led to the formation of a compact structure due to their even dispersion, supported by a wider contact area with the matrix, as their surface contained more cellulose OH groups. FTIR analysis also confirmed the reduction of hemicellulose due to alkalization treatment characterized by a decrease in peak intensity around 1750 and 1250 cm−1. On the other hand, the removal of lignin was characterized by a change in the peak between 1030–1150 cm−1. The best thermal stability was also achieved by PLA/SBF-A6, which was able to withstand temperatures up to 345.92°C according to TGA analysis. With the mechanical and thermal properties of PLA/SBF biocomposites, they have the potential to be good materials in various applications such as automotive and household components.

Acknowledgement: We thanks to Institute for Research and Community Services (LPPM), Universitas Jember, Indonesia for the funding with the International Research Collaboration Scheme. In addition, we also thank to Abduh for providing a place for discussion.

Funding Statement: This research was funded and supported by the Institute of Research and Community Service (LPPM), Universitas Jember, for International Research Collaboration Scheme with project number: 3565/UN25.3.1/LT/2023.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, data curation, project administration, funding acquisition, and supervision: Mochamad Asrofi. Writing—original draft: Mochamad Asrofi, Muhammad Oktaviano Putra Hastu, Muhammad Luthfi Al Anshori, Feyza Igra Harda Putra. Research assistant and investigation in laboratory: Mochamad Asrofi, Muhammad Oktaviano Putra Hastu, Muhammad Luthfi Al Anshori, Feyza Igra Harda Putra, Revvan Rifada Pradiza, Haris Setyawan, Muhammad Yusuf, and Mhd Siswanto. Formal analysis, data validation, and writing review and editing: R.A. Ilyas and Muhammad Asyraf Muhammad Rizal. Supervision and validation: Salit Mohd Sapuan. Formal analysis: Mohd Nor Faiz Norrrahim and Victor Feizal Knight. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The detailed data obtained through this study and presented in this article can be requested from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Czapla A, Ganesapillai M, Drewnowski J. Composite as a material of the future in the era of green deal implementation strategies. Processes. 2021;9(12):2238. doi:10.3390/pr9122238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Uzoma AE, Nwaeche CF, Al-Amin M, Muniru OS, Olatunji O, Nzeh SO. Development of interior and exterior automotive plastics parts using kenaf fiber reinforced polymer composite. Eng. 2023;4(2):1698–710. doi:10.3390/eng4020096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Din MI, Ghaffar T, Najeeb J, Hussain Z, Khalid R, Zahid H. Potential perspectives of biodegradable plastics for food packaging application-review of properties and recent developments. Food Addit Contam Part A. 2020;37(4):665–80. doi:10.1080/19440049.2020.1718219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Litchfield SG, Schulz KG, Kelaher BP. The influence of plastic pollution and ocean change on detrital decomposition. Mar Pollut Bull. 2020;158(2):111354. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kuan HTN, Tan MY, Shen Y, Yahya MY. Mechanical properties of particulate organic natural filler-reinforced polymer composite: a review. Compos Adv Mater. 2021;30(5):26349833211007502. doi:10.1177/26349833211007502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rajeshkumar G, Seshadri SA, Devnani GL, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, Maran JP, et al. Environment friendly, renewable and sustainable poly lactic acid (PLA) based natural fiber reinforced composites—a comprehensive review. J Clean Prod. 2021;310(1):127483. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Sergi C, Bavasso I, Frighetto G, Tirillò J, Sarasini F, Casalini S. Linoleum waste as PLA filler for components cost reduction: effects on the thermal and mechanical behavior. Polym Test. 2024;138:108548. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2024.108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sanivada UK, Mármol G, Brito FP, Fangueiro R. PLA composites reinforced with flax and jute fibers—a review of recent trends, processing parameters and mechanical properties. Polymers. 2020;12(10):2373. doi:10.3390/polym12102373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Borysiuk P, Boruszewski P, Auriga R, Danecki L, Auriga A, Rybak K, et al. Influence of a bark-filler on the properties of PLA biocomposites. J Mater Sci. 2021;56(15):9196–208. doi:10.1007/s10853-021-05901-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Pokharel A, Falua KJ, Babaei-Ghazvini A, Nikkhah Dafchahi M, Tabil LG, Meda V, et al. Development of polylactic acid films with alkali-and acetylation-treated flax and hemp fillers via solution casting technique. Polymers. 2024;16(7):996. doi:10.3390/polym16070996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Pongputthipat W, Ruksakulpiwat Y, Chumsamrong P. Development of biodegradable biocomposite films from poly(lactic acidnatural rubber and rice straw. Polym Bull. 2023;80(9):10289–307. doi:10.1007/s00289-022-04560-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Rathinavel S, Prakash JA, Balavairavan B, Prithviraj M, Saravankumar SS, Ganeshbabu A. Characterization of anti bacterial biocomposite films based on poly lactic acid and prosopis juliflora bark powder. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;282(3):137103. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.137103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Silva CG, Campini PA, Rocha DB, Rosa DS. The influence of treated eucalyptus microfibers on the properties of PLA biocomposites. Compos Sci Technol. 2019;179:54–62. doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2019.04.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jing H, He H, Liu H, Huang B, Zhang C. Study on properties of polylactic acid/lemongrass fiber biocomposites prepared by fused deposition modeling. Polym Compos. 2021;42(2):973–86. doi:10.1002/pc.25879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mohammed M, Rahman R, Mohammed AM, Adam T, Betar BO, Osman A, et al. Surface treatment to improve water repellence and compatibility of natural fiber with polymer matrix: recent advancement. Polym Test. 2022;115(8):107707. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2022.107707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jamadi AH, Razali N, Petrů M, Taha MM, Muhammad N, Ilyas RA. Effect of chemically treated kenaf fibre on mechanical and thermal properties of PLA composites prepared through fused deposition modeling (FDM). Polymers. 2021;13(19):3299. doi:10.3390/polym13193299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhu Z, Hao M, Zhang N. Influence of contents of chemical compositions on the mechanical property of sisal fibers and sisal fibers reinforced PLA composites. J Nat Fibers. 2020;17(1):101–12. doi:10.1080/15440478.2018.1469452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mukaffa H, Asrofi M, Hermawan Y, Qoryah RDH, Sapuan SM, Ilyas RA, et al. Effect of alkali treatment of piper betle fiber on tensile properties as biocomposite based polylactic acid: solvent cast-film method. Mater Today. 2022;48:761–5. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.02.218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Amiri A, Ulven CA, Huo S. Effect of chemical treatment of flax fiber and resin manipulation on service life of their composites using time-temperature superposition. Polymers. 2015;7(10):1965–78. doi:10.3390/polym7101493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu H, He H, Peng X, Huang B, Li J. Three-dimensional printing of poly(lactic acid) bio-based composites with sugarcane bagasse fiber: effect of printing orientation on tensile performance. Polym Adv Technol. 2019;30(4):910–22. doi:10.1002/pat.4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mohanty AK, Misra M, Drzal LT. Surface modifications of natural fibers and performance of the resulting biocomposites: an overview. Compos Interfaces. 2001;8(5):313–43. doi:10.1163/156855401753255422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Adekomaya O, Adama K. Glass-fibre reinforced composites: the effect of fibre loading and orientation on tensile and impact strength. Niger J Technol. 2017;36(3):782–7. doi:10.4314/njt.v36i3.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Teli MD, Terega JM. Effects of alkalization on the properties of Ensete ventricosum plant fibre. J Text Inst. 2019;110(4):496–507. doi:10.1080/00405000.2018.1492321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mallick N, Soni A, Pai D. Improving the mechanical, water vapor permeability, antimicrobial properties of corn-starch/poly vinyl alcoholfilm (PVAeffect of Rice husk fiber (RH) & Alovera gel (AV). In: Proceedings of the National Conference on Advanced Materials and Applications (NCAMA 2019); 2019 Dec 21–22; Raipur, India. [Google Scholar]

25. Nassiopoulos E, Njuguna J. Thermo-mechanical performance of poly(lactic acid)/flax fibre-reinforced biocomposites. Mater Des. 2015;66(10):473–85. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2014.07.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jaafar CNA, Rizal MAM, Zainol I. Effect of kenaf alkalization treatment on morphological and mechanical properties of epoxy/silica/kenaf composite. Int J Eng Technol. 2018;7(4):258–63. doi:10.14419/ijet.v7i4.35.22743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Frącz W, Janowski G, Bąk Ł. Influence of the alkali treatment of flax and hemp fibers on the properties of PHBV based biocomposites. Polymers. 2021;13(12):1965. doi:10.3390/polym13121965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Rajeshkumar G, Hariharan V, Indran S, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, Maran JP, et al. Influence of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) treatment on mechanical properties and morphological behaviour of Phoenix sp. fiber/epoxy composites. J Environ Polym Degrad. 2021;29(3):765–74. doi:10.1007/s10924-020-01921-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Prasanna GV, Kumar JN, Kumar KA. Optimisation & mechanical testing of hybrid biocomposites. Mater Today. 2019;18(8):3849–55. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2019.07.324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kamaal M, Anas M, Rastogi H, Bhardwaj N, Rahaman A. Effect of FDM process parameters on mechanical properties of 3D-printed carbon fibre-PLA composite. Prog Addit Manuf. 2021;6(1):63–9. doi:10.1007/s40964-020-00145-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Reddy SRT, Prasad AR, Ramanaiah K. Tensile and flexural properties of biodegradable jute fiber reinforced poly lactic acid composites. Mater Today. 2021;44(9):917–21. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.10.806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sahu P, Gupta MK. A review on the properties of natural fibres and its bio-composites: effect of alkali treatment. J Mater. 2020;234(1):198–217. doi:10.1177/1464420719875163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Siakeng R, Jawaid M, Asim M, Fouad H, Awad S, Saba N, et al. Flexural and dynamic mechanical properties of alkali-treated coir/pineapple leaf fibres reinforced polylactic acid hybrid biocomposites. J Bionic Eng. 2021;18(6):1430–8. doi:10.1007/s42235-021-00086-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Rangappa SM, Siengchin S, Parameswaranpillai J, Jawaid M, Ozbakkaloglu T. Lignocellulosic fiber reinforced composites: progress, performance, properties, applications, and future perspectives. Polym Compos. 2022;43(2):645–91. doi:10.1002/pc.26413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Boumaaza M, Belaadi A, Bourchak M. The effect of alkaline treatment on mechanical performance of natural fibers-reinforced plaster: optimization using RSM. J Nat Fibers. 2021;18(12):2220–40. doi:10.1080/15440478.2020.1724236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Reddy KO, Maheswari CU, Shukla M, Song JI, Rajulu AV. Tensile and structural characterization of alkali treated Borassus fruit fine fibers. Composites. 2013;44(1):433–8. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.04.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kabir MM, Wang H, Lau KT, Cardona F. Chemical treatments on plant-based natural fibre reinforced polymer composites: an overview. Composites. 2012;43(7):2883–92. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.04.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yeo JCC, Muiruri JK, Koh JJ, Thitsartarn W, Zhang X, Kong J, et al. Bend, twist, and turn: first bendable and malleable toughened PLA green composites. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(30):2001565. doi:10.1002/adfm.202001565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Olonisakin K, Fan M, Zhang X-X, Ran L, Lin W, Zhang W, et al. Key improvements in interfacial adhesion and dispersion of fibers/fillers in polymer matrix composites; focus on PLA matrix composites. Compos Interfaces. 2022;29(10):1071–120. doi:10.1080/09276440.2021.1878441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang Y, Liu S, Wang Q, Ji X, Yang G, Chen J, et al. Strong, ductile and biodegradable polylactic acid/lignin-containing cellulose nanofibril composites with improved thermal and barrier properties. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;171:113898. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Bartos A, Nagy K, Anggono J, Purwaningsih H, Móczó J, Pukánszky B. Biobased PLA/sugarcane bagasse fiber composites: effect of fiber characteristics and interfacial adhesion on properties. Composites. 2021;143(4):106273. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2021.106273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Pappu A, Pickering KL, Thakur VK. Manufacturing and characterization of sustainable hybrid composites using sisal and hemp fibres as reinforcement of poly(lactic acid) via injection moulding. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;137:260–9. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.05.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Wang F, Zhou S, Yang M, Chen Z, Ran S. Thermo-mechanical performance of polylactide composites reinforced with alkali-treated bamboo fibers. Polymers. 2018;10(4):401. doi:10.3390/polym10040401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Ramachandran A, Rangappa SM, Kushvaha V, Khan A, Seingchin S, Dhakal HN. Modification of fibers and matrices in natural fiber reinforced polymer composites: a comprehensive review. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2022;43(17):2100862. doi:10.1002/marc.202100862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Sari NH, Suteja Fatriasari W. Integration of biopolyesters and natural fibers in structural composites: an innovative approach for sustainable materials. J Renew Mater. 2025. doi:10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Asrofi M, Abral H, Kurnia Y, Sapuan SM, Kim H. Effect of duration of sonication during gelatinization on properties of tapioca starch water hyacinth fiber biocomposite. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;108:167–76. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.11.165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Siakeng R, Jawaid M, Ariffin H, Sapuan SM, Asim M, Saba N. Natural fiber reinforced polylactic acid composites: a review. Polym Compos. 2019;40(2):446–63. doi:10.1002/pc.24747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Neto JSS, Lima RAA, Cavalcanti DKK, Souza JPB, Aguiar RAA, Banea MD. Effect of chemical treatment on the thermal properties of hybrid natural fiber-reinforced composites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2019;136(10):47154. doi:10.1002/app.47154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Song X, He W, Han X, Qin H. Fused deposition modeling of poly(lactic acid)/nutshells composite filaments: effect of alkali treatment. J Environ Polym Degrad. 2020;28(12):3139–52. doi:10.1007/s10924-020-01839-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zhu Z, Wu H, Ye C, Fu W. Enhancement on mechanical and thermal properties of PLA biocomposites due to the addition of hybrid sisal fibers. J Nat Fibers. 2017;14(6):875–86. doi:10.1080/15440478.2017.1302382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Al Abdallah H, Abu-Jdayil B, Iqbal MZ. The effect of alkaline treatment on poly(lactic acid)/date palm wood green composites for thermal insulation. Polymers. 2022;14(6):1143. doi:10.3390/polym14061143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Zhao S, Chen S, Ren S, Li G, Song K, Guo J, et al. Preparation and performance of pueraria lobata root powder/polylactic acid composite films. J Renew Mater. 2023;11(6):2531–53. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.026066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Knez N, Kariž M, Knez F, Ayrilmis N, Kuzman MK. Effects of selected printing parameters on the fire properties of 3d-printed neat polylactic acid (PLA) and wood/PLA composites. J Renew Mater. 2021;9(11):1883–95. doi:10.32604/jrm.2021.016128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Siakeng R, Jawaid M, Asim M, Saba N, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, et al. Alkali treated coir/pineapple leaf fibres reinforced PLA hybrid composites: evaluation of mechanical, morphological, thermal and physical properties. Express Polym Lett. 2020;14(8):717–30. doi:10.3144/expresspolymlett.2020.59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Rout AK, Kar J, Jesthi DK, Sutar AK. Effect of surface treatment on the physical, chemical, and mechanical properties of palm tree leaf stalk fibers. BioResources. 2016;11(2):4432–45. doi:10.15376/biores.11.2.4432-4445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Asaithambi B, Ganesan GS, Ananda Kumar S. Banana/sisal fibers reinforced poly(lactic acid) hybrid biocomposites; influence of chemical modification of BSF towards thermal properties. Polym Compos. 2017;38(6):1053–62. doi:10.1002/pc.23668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Sekar SM, Nagarajan R, Selvakumar P, Ismail SO, Krishnan K, Mohammad F, et al. Isolation of microcrystalline cellulose from wood and fabrication of polylactic acid (PLA) based green biocomposites. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(8):1455–74. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.052952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Dungani R, Bakshi MI, Hanifa TZ, Dewi M, Syamani FA, Mahardika M, et al. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanofiber (CNF) from kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus) bast through the chemo-mechanical process. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(6):1057–69. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.049342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Jamadi AH, Razali N, Malingam SD, Taha MM. Effect of fibre size on mechanical properties and surface roughness of PLA composites by using fused deposition modelling (FDM). J Renew Mater. 2023;11(8):3261–76. doi:10.32604/jrm.2023.028280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Negawo TA, Polat Y, Buyuknalcaci FN, Kilic A, Saba N, Jawaid M. Mechanical, morphological, structural and dynamic mechanical properties of alkali treated Ensete stem fibers reinforced unsaturated polyester composites. Compos Struct. 2019;207(7):589–97. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.09.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Paul S, Joseph A, Hridhya PD, Badawi M, Ajithkumar TG, Parameswaranpillai P, et al. Extraction of highly crystalline and thermally stable cellulose nanofiber from Heliconia psittacorum L.f. leaves. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;308:142264. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.142264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools