Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cotton Residue Biomass-Based Electrochemical Sensors: The Relation of Composition and Performance

Departamento de Química, Universidade Regional de Blumenau (FURB), Blumenau, 89012900, SC, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: Eduardo Guilherme Cividini Neiva. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Renewable Nanostructured Porous Materials: Synthesis, Processing, and Applications)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 1899-1912. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0130

Received 30 June 2025; Accepted 10 September 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

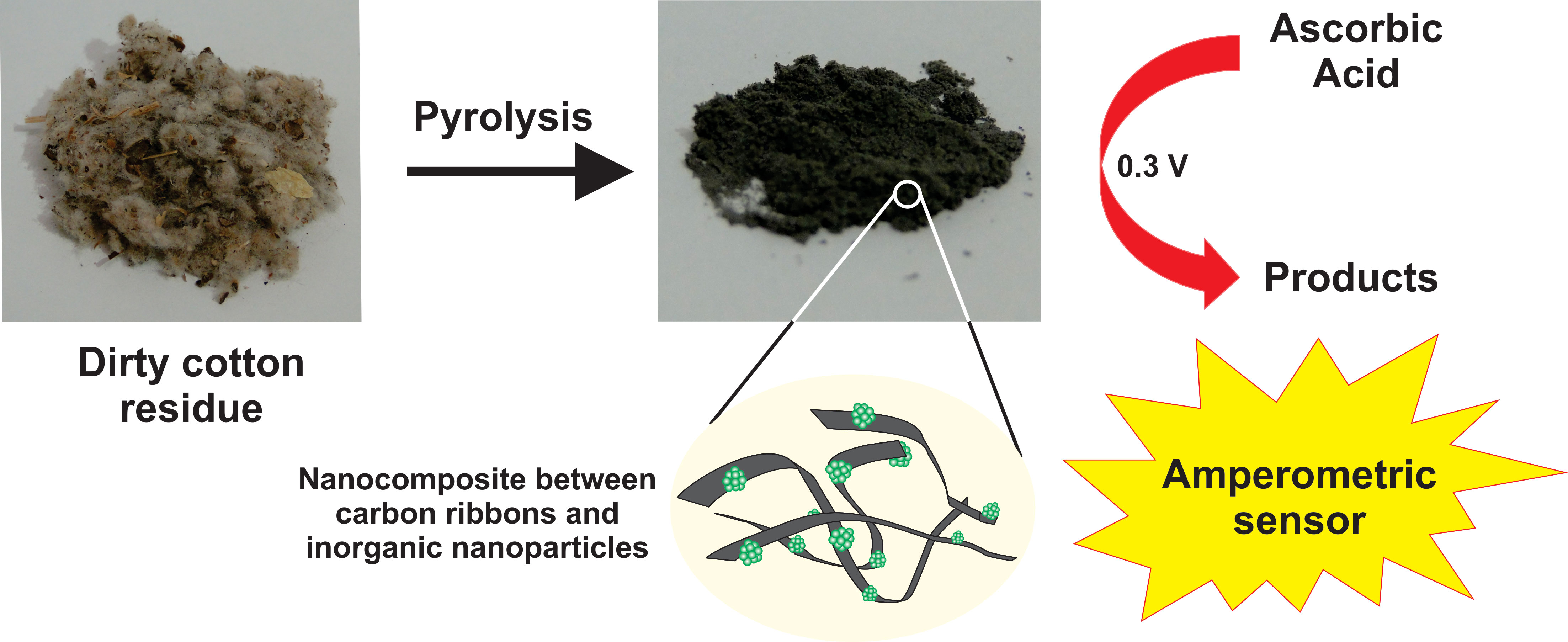

Here, we report a comprehensive study on the characterization of cotton biomass residue, its conversion into carbon-based materials via pyrolysis, and its application as an electrochemical sensor for ascorbic acid (AA). The compositions, morphologies, and structures of the resulting materials were investigated using XRD, FTIR, TGA, SEM, and EDS. Pyrolysis was carried out in an air atmosphere at different temperatures (300°C and 400°C) and durations (1, 60, and 240 min), leading to the transformation of lignocellulosic cotton residue into carbon-based materials embedded with inorganic nanoparticles, including carbonates, sulfates, chlorates, and phosphates of potassium, calcium, and magnesium. These inorganic nanoparticles exhibited irregular shapes with sizes ranging from 50 to 150 nm. The pyrolysis conditions significantly influenced both the mass ratio and the crystallinity of the inorganic phases, with treatment at 400°C for 60 min resulting in enhanced crystallinity and an inorganic content of 54.4%. The cotton biomass-based nanomaterials were used in the construction of carbon paste electrodes (CPEs) and evaluated in PBS for AA oxidation. The electrocatalytic performance increased with the inorganic nanoparticle content. Among all, the sample pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min demonstrated the highest sensitivity (3.31 ± 0.16 μA (mmol·L−1)−1), along with low limits of detection (2.90 ± 1.87 μmol·L−1) and quantification (9.66 ± 6.23 μmol·L−1). These promising sensor characteristics highlight the potential of cotton biomass residue as a renewable source of electroactive nanomaterials, considering the simplicity of the carbon material preparation process and the ease of electrode fabrication.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileAlthough cotton fibers are mainly composed of cellulose, a linear polysaccharide consisting of β-D-glucopyranosyl residues linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, and with a carbon content as high as 44%, the processing of cotton, including cultivation, harvesting, and spinning, generates a significant amount of voluminous, bulky lignocellulosic residues that occupy a large area in landfills [1]. Purification of cotton fibers during the spinning process by yarn producing textile companies generates further residues containing short cotton fibers and trash (cotton seed fragments, leaves stalk residues, etc.) [2,3]. According to Holtz et al. [4], the waste generated by the textile industry amounts to approximately 8% of all processed cotton, with low rates of decomposition in the soil and is poorly included in animal diets. Furthermore, the production of end-of-life waste textiles is increasing, and approximately 40% of this waste is composed of cellulosic fibers, which are incinerated or used in landfills [1].

In line with the principles of a green economy and sustainable society development, biomass-derived carbon materials have attracted significant attention in recent years due to their abundance, low cost, non-toxicity, and renewable nature [5,6]. Raw cotton, a biomass composed of entangled microscale cellulose fibers, is lightweight, flexible, and can be readily transformed into carbon materials through thermal annealing [7]. Cotton fibers are considered the purest form of plant cellulose, containing approximately 90% cellulose [8], which makes them a highly appealing precursor for carbon material production. Consequently, waste cotton textiles present a promising, cost-effective, and efficient alternative for obtaining carbon materials suitable for electrochemical applications. Typically, however, cotton-derived carbon materials require additional activation and modification processes to enhance their functionality and performance—particularly for energy storage purposes [9]. These extra steps, however, tend to increase both the processing time and overall production costs. Nevertheless, activated carbon can be obtained through the pyrolysis of different biomasses. Potham and Ramanujam developed a rapid and simple method involving pre-carbonization and pyrolysis of chitosan, followed by a neutralizing acid treatment [10]. Zhang et al. produced activated carbon using plane tree fruit biomass pyrolyzed at 700°C, 800°C, and 900°C [11]. In both studies, the obtained materials exhibited high electroactivity for energy storage, highlighting the potential of biomass-based carbon precursors for electrochemical applications.

Ascorbic acid (AA), commonly known as vitamin C, is an antioxidant widely present in foods and biological samples [12]. Its detection and quantification are crucial, as both excessively high and low concentrations may lead to food quality deterioration and various health issues. AA is frequently added to foods and beverages to enhance their appearance [13]. Moreover, it plays an essential role in the biosynthesis of carnitine, collagen, and neurotransmitters [14]. According to the European Food Safety Authority, the recommended daily intake of AA for healthy adults is approximately 90 mg [15]. Elevated levels of AA may result in renal and gastrointestinal disturbances [16], whereas a deficiency can lead to scurvy and negatively impact the immune system, cholesterol levels, protein metabolism, and iron absorption [17,18]. Although several studies have explored the use of biomass to obtain various forms of carbon, with or without metal nanoparticles, for the electrochemical detection of AA, many require multiple preparation steps, rely on biomass in its natural state, or require the use of additional metal precursors [19–23].

In this study, we present the characterization of two types of cotton residues, their thermal conversion into carbon-based materials, and their application as electroactive materials for the detection of AA. The resulting materials were analyzed using various structural, morphological, and compositional techniques. This approach to carbon material production demonstrates a viable, low-cost, and sustainable method for fabricating sensors from biomass waste—an abundant, inexpensive, and renewable resource—without the need for additional purification or activation steps.

Two different lignocellulosic residues from cotton spinning were obtained from Hantex Resíduos Têxteis (Gaspar, Santa Catarina, Brazil), denominated cotton filter powder (CFP) and dirty cotton residue (DCR). HCl (Dinâmica, 37%), nujol (Mantecorp, 100%), graphite (Fischer Chemical, analytical grade), AA (Sigma, 99%), NaCl (analytical grade, Vetec), KCl (analytical grade, Dinâmica), uric acid (UA, 99%, Sigma), urea (99.5%, Merck), fructose (99%, Sigma), glucose (99.5%, Sigma), NaH2PO4 anhydrous (Vetec, 99%), and Na2HPO4 anhydrous (Vetec, 99%) were used as received. The aqueous solutions were prepared using deionized water.

2.2 Chemical Characterization of Cotton Residue

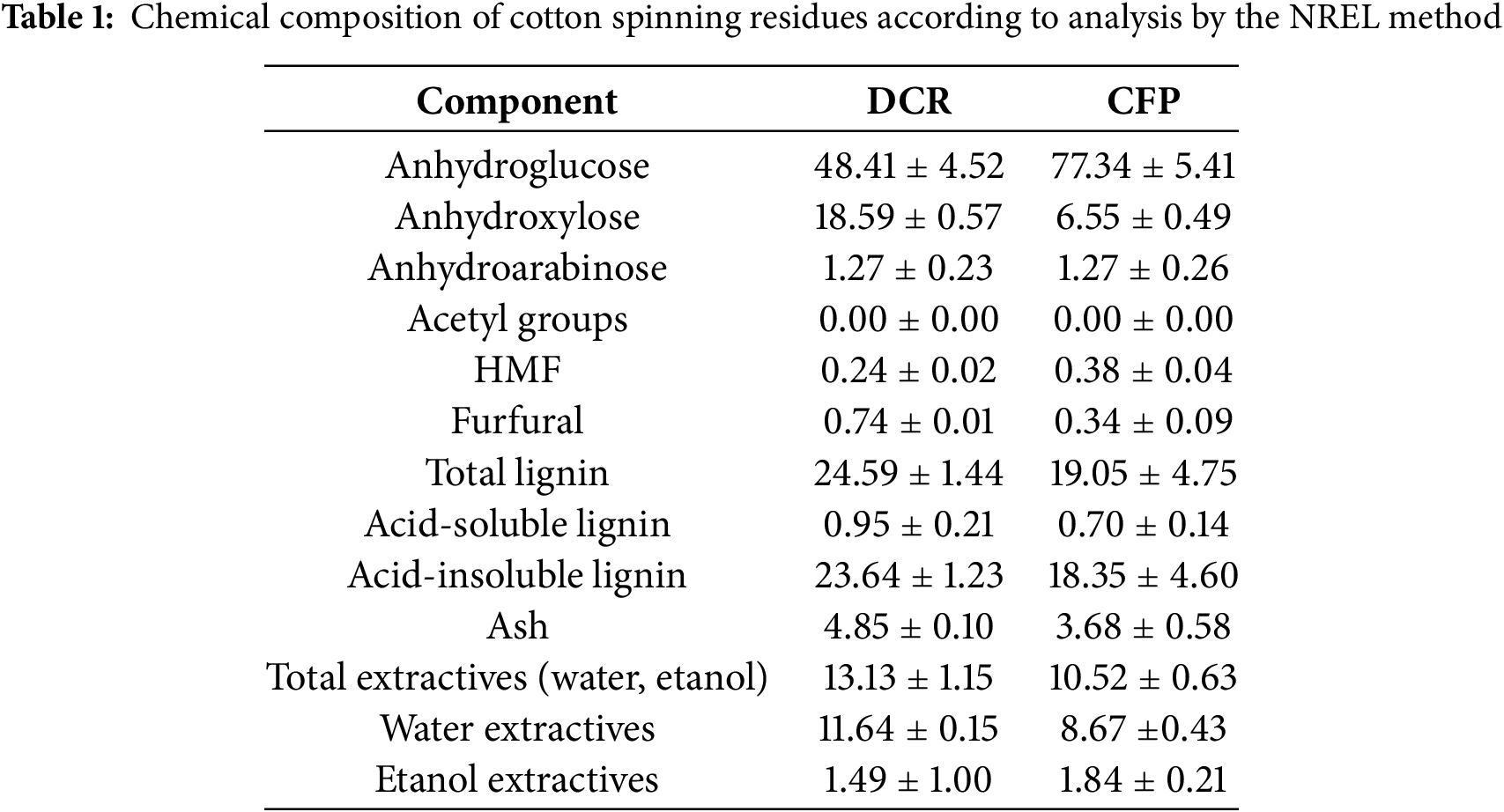

The chemical composition of CFP and DCR was characterized regarding their total moisture, total lignin, and polysaccharide contents according to the well-established NREL methods [24,25]. Acid-insoluble lignin was quantified gravimetrically, while acid-soluble lignin was determined by UV spectrophotometry of biomass acid hydrolysates. The glucan and hemicellulose (containing predominantly xylose and arabinose groups) contents were determined using a Thermo-Scientific 3000 Ultra high-performance liquid chromatograph (UHPLC) system equipped with a Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87H column, a DAD 3000 detector, and a refractive index (RI) detector. Analyses were performed at 65°C with 5 mmol·L−1 H2SO4 as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.6 mL·min−1. Quantitative analyses were performed by external calibration using standard solutions of glucose, xylose, arabinose, and acetic acid. In addition, total extractives and ash of untreated DCR and CFP were determined as recommended by the NREL/TP-510-42619, NREL/TP-510-42622 and ISO 8968-1:2014 methods [26], respectively. All analyses were conducted in triplicate and are presented as mean values with their corresponding standard deviations.

2.3 Pyrolysis of Cotton Biomass

The DCR biomass was pyrolyzed in a muffle furnace under an air atmosphere, placed in porcelain crucibles. The pyrolysis was conducted at 300°C for 60 and 240 min, and at 400°C for 1 and 60 min.

The cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 300°C for 240 min was purified using a 6 mol L−1·HCl aqueous solution at room temperature for 24 h under stirring. Afterwards, the material was washed several times through centrifugation with deionized water until it reached pH 7.

2.4 Morphological and Structural Characterizations

The X-ray diffraction analyses (XRD) were carried out using a Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffractometer operating at 30 mA and 40 kV with CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å).

FT-IR spectra were collected using a Bruker instrument in attenuated total reflection mode (ATR) with 20 scans and a resolution of 4 cm−1.

Thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) were carried out using a Perkin Elmer 4000 under a synthetic air atmosphere at 10°C min−1 from 60°C to 800°C, with a pre-treatment of 100°C for 20 min to remove adsorbed moisture.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained using a Tescan Field Emission Gun (FEG) microscope, equipped with a secondary electron detector and operating at 10 kV. For SEM analyses, samples were placed on Cu adhesive tapes. Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analyses were also performed on the same equipment using an Oxford accessory.

2.5 Electrochemical Characterization and Electroanalytical Application

The electrochemical measurements were carried out using a Palmsens potentiostat in a three-electrode system with modified carbon paste electrodes (CPEs) as the working electrode (WE), Ag/AgCl (NaCl saturated) as the reference electrode (RE), and a Pt wire as the auxiliary electrode (AE). The cyclic voltammograms of the CPE were recorded from 0.1 to 1.0 V at 50 mV·s−1. The chronoamperometric detections of AA were carried out at an applied potential of 0.3 V under magnetic stirring with four successive additions of 0.1 mmol·L−1 AA. Cyclic voltammograms were also recorded in 1 mmol·L−1 [Fe(CN)6]4− and 0.1 mol·L−1 NaCl aqueous solution using scan rates from 5 to 100 mV·s−1. Reproducibility and repeatability were assessed by performing four successive additions of 0.1 mmol·L−1 AA.

To prepare the modified CPE, the pyrolyzed cotton biomass, Nujol and graphite were mixed in a proportion of 20/20/60, respectively, and homogenized for 20 min in a mortar with a pestle. The resulting paste was then packed into a cavity of approximately 1 mm deep and 1 mm wide in a plastic tube containing a copper wire, polished on glossy paper.

The non-modified CPE was prepared by mixing Nujol and graphite in a proportion of 20/80, respectively.

Cotton Residue Characterization

Characterization of both cotton residues revealed similar results to other cotton residues [27,28] and previous analyses of the same type of residue [26,27,29]. However, as the material received from the textile company that purifies and resells these residues is quite heterogeneous, certain variations in its composition are expected. According to the chemical characterization (Table 1), the DCR residue, which presented a higher ash content, was considered more suitable for pyrolysis. Therefore, all further experiments were carried out using DCR.

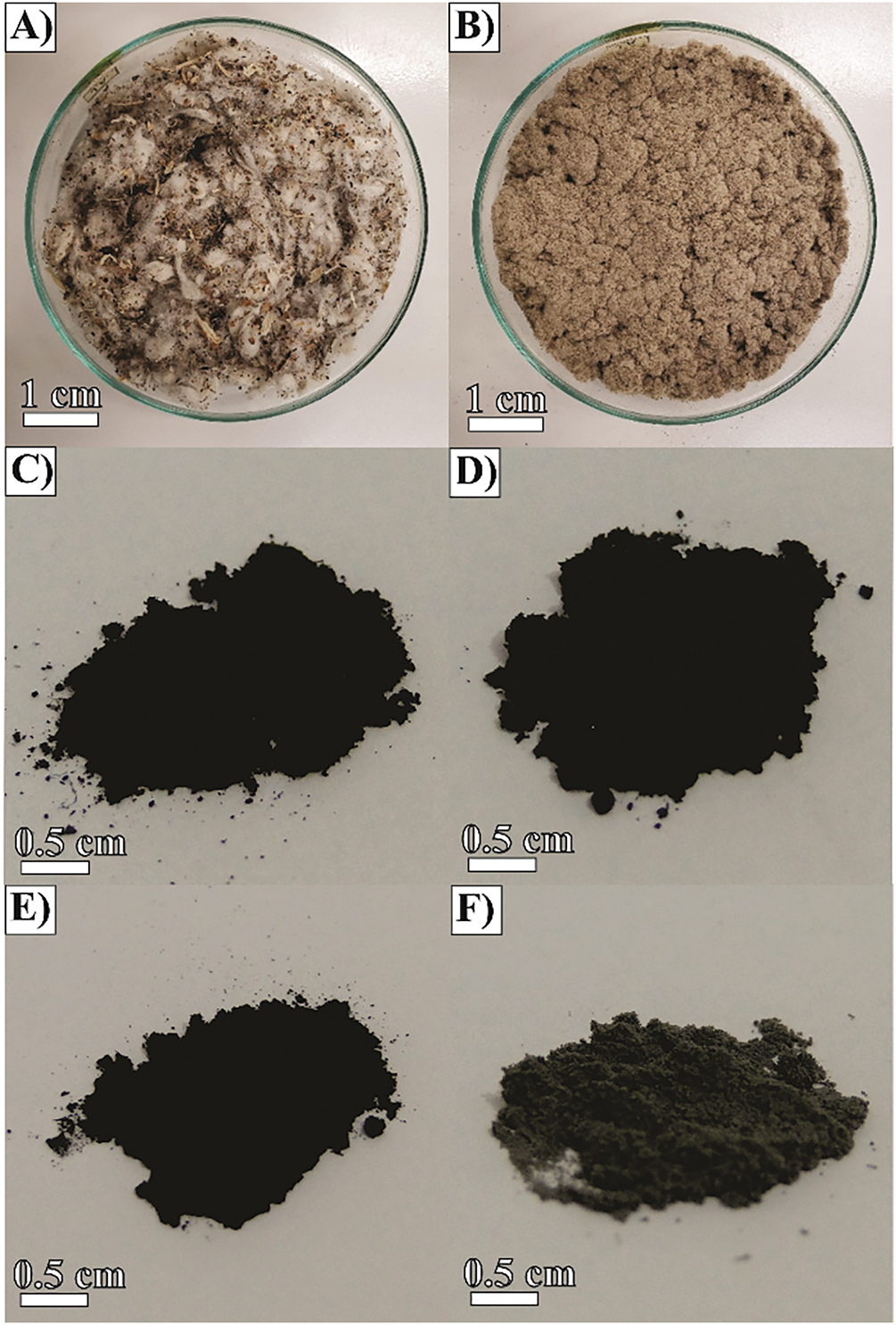

The cotton biomass DCR before and after pyrolysis presents different aspects, as can be seen in the photographic images in Fig. 1. The precursor shows a typical yellowish white coloration with brown stems (Fig. 1A). After pyrolysis, all the biomasses became black, except that pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min, which turned gray (Fig. 1E). These colors suggest different compositions. The black appearance suggests that biomasses were mainly converted into carbon. However, at 400°C for 60 min, the gray color indicates a high proportion of inorganic compounds, such as oxides, indicating oxidation of the material. The materials were weighed after pyrolysis, yielding conversion ratios of 26%, 15%, 76% and 7% for the cotton biomass DCR pyrolyzed at 300°C for 60 and 240 min, and 400°C for 1 and 60 min, respectively. As expected, longer durations and higher temperatures of pyrolysis led to a higher consumption of the carbon content, increasing the inorganic ratio in the samples. To better understand the composition of these materials, several characterizations techniques were employed, including XRD, FTIR, TGA/DTGA, SEM, and EDS.

Figure 1: Photographic images of cotton residues (A) DCR (dirty cotton residue) and (B) CFP (cotton filter powder), and pyrolyzed DCR (C) at 300°C for 60 min, (D) 240 min, (E) 400°C for 1 min, and (F) 60 min

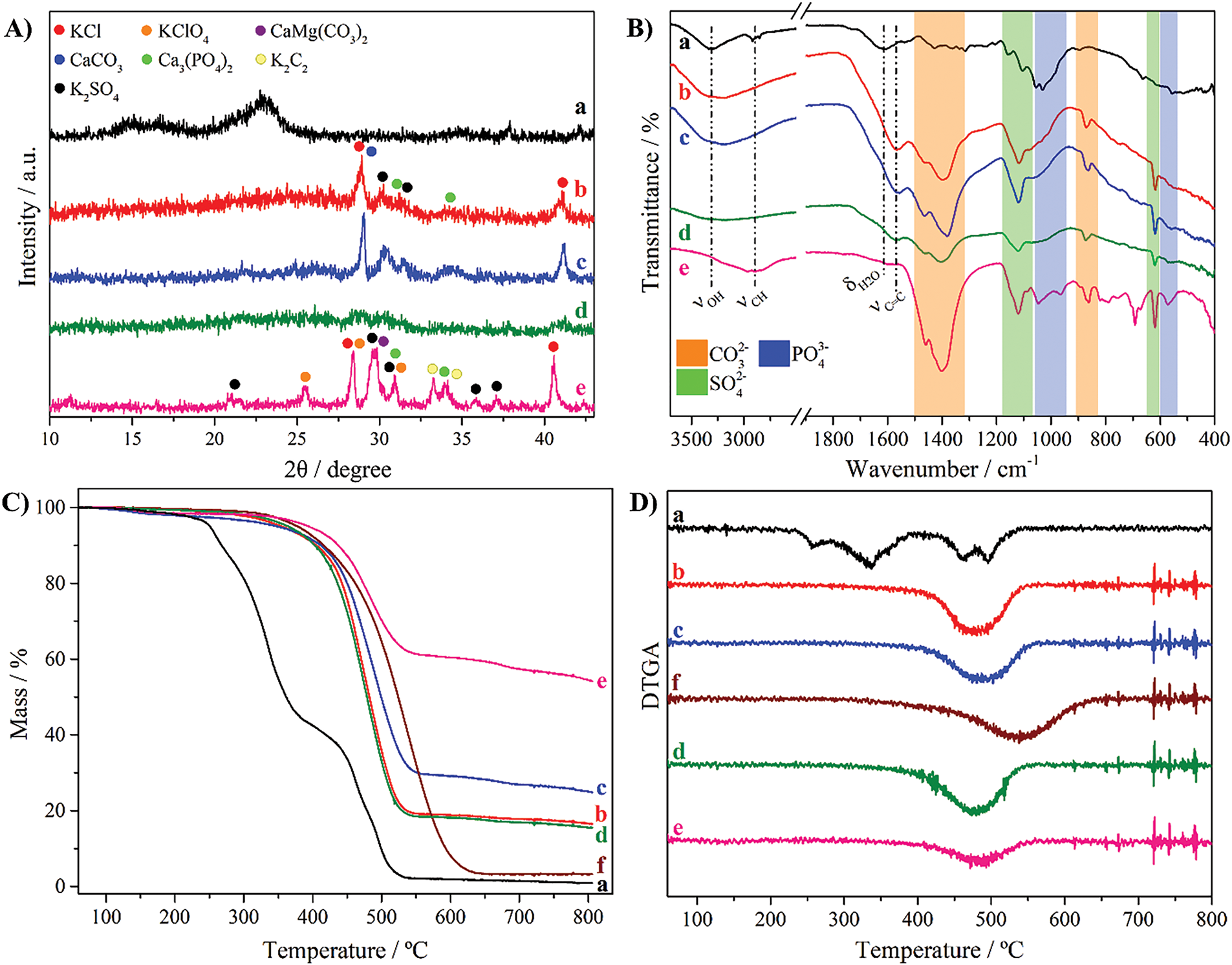

The XRD patterns of the cotton residue biomass-based compounds are depicted in Fig. 2A. It is clear to see the differences between pyrolyzes conditions and the cotton biomass precursor. The latter exhibits a broad signal at 22.9° attributed to its amorphous structure. When pyrolyzed at 300°C for 60 and 240 min, the same set of peaks was observed, corresponding to KCl, CaCO3, K2SO4, and Ca3(PO4)2 (ICDD PDF 00-041-1476, 01-080-3276, 04-017-4456, and 04-010-4348, respectively). However, longer pyrolysis times increased the peak intensity, while also producing narrower and slightly shifted peaks. This phenomenon indicates an increase in the crystallinity of these compounds. Probably due to the short time of pyrolysis at 400°C (1 min), no peaks were raised for this condition. Differently, at 400°C for 60 min produced several peaks attributed to K2SO4, KClO4, KCl, CaMg(CO3)2, Ca3(PO4)2, and K2C2 (ICDD PDF 04-017-4456, 00-007-0211, 00-041-1476, 00-043-0697, 04-010-4348, and 01-076-1714, respectively).

Figure 2: (A) XRD patterns, (B) FTIR spectra, (C) TGA and (D) DTGA curves of cotton biomass (a) and cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 300°C for 60 (b) and 240 min (c), and 400°C for 1 (d) and 60 min (e). (f) corresponds to the cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 300°C for 240 min purified with 6 mol·L−1 HCl aqueous solution. The TGA analyses were carried out in an air atmosphere at 10°C min−1

The cotton biomass presented typical bands in the FTIR spectrum (Fig. 2B) at 3310 (νOH), 2913/2860 (νCH), 1730 (νC=O), 1614 (δH2O), 1525 (νC=C), 1427 (δC-OH and δ-CH2-), 1309 (δCH3) and 1156/1105/1053/1028 cm−1 (νC-O-C and νC-OH) [30]. These bands indicate the presence of hydroxyl, carboxylic acid, carbonyl, ester, and other functional groups present in the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin polysaccharides [30]. In contrast, all the pyrolyzed biomass materials presented a band at 1566 cm−1 (νC=C) typical of carbon-based materials. In addition, these materials also showed bands at 1466/1392 (νCO32−), 1117 (νSO42−), 1044/964 (νPO43−), 867 (δOCO of CO32−), 619 (δOSO of SO42−) and 567 cm−1 (νPO43−), confirming the presence of carbonate, sulphate, and phosphate compounds [31–33]. Thus, the pyrolysis at 400°C for 1 min produced these compounds with very low crystallinity, leading to the absence of peaks in XRD (Fig. 2A).

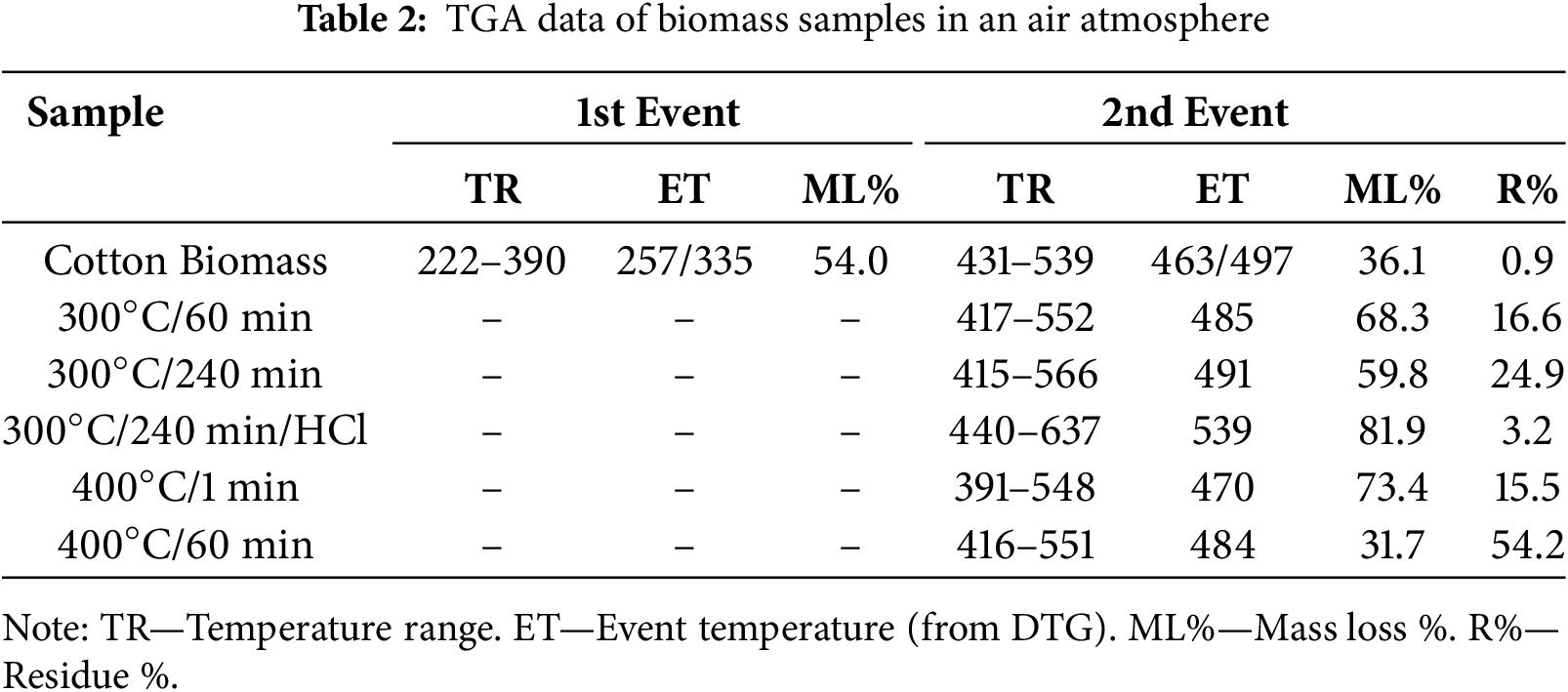

The thermogravimetric curves of biomass-based compounds in synthetic air atmosphere are shown in Fig. 2C. The cotton biomass exhibited two events of mass loss from 222°C to 390°C and from 431°C to 539°C. These events corresponded to 54.0% and 36.1% of mass loss, and average temperatures of 306°C and 495°C (Fig. 2D), respectively. They are related to degradation of the cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin to aliphatic char, followed by its oxidation to CO and CO2, respectively [34], leading to a final residue of 0.9%. In contrast, the pyrolyzed materials exhibited a similar profile with only one mass loss event at higher temperatures attributed to the oxidation of the carbon structure. However, they showed different residue percentages, which were attributed to the inorganic content in each sample. As can be seen in Table 2, the longer the pyrolysis time and the temperature of pyrolysis, the higher the residue %, reaching up to 54.2% for the pyrolysis at 400°C for 60 min. This behavior is expected due to the pyrolyzes being performed under air atmosphere, leading to the oxidation of cotton biomass. The material pyrolyzed at 300°C for 240 min was purified with 6 mol·L−1 HCl aqueous solution and analyzed by TGA. As can be seen in Table 2, this treatment was effective and led to a residue of 3.2%. In addition, the lower inorganic content in this material led to a higher thermal stability of the carbon structure, indicating that these species catalyze the carbon oxidation.

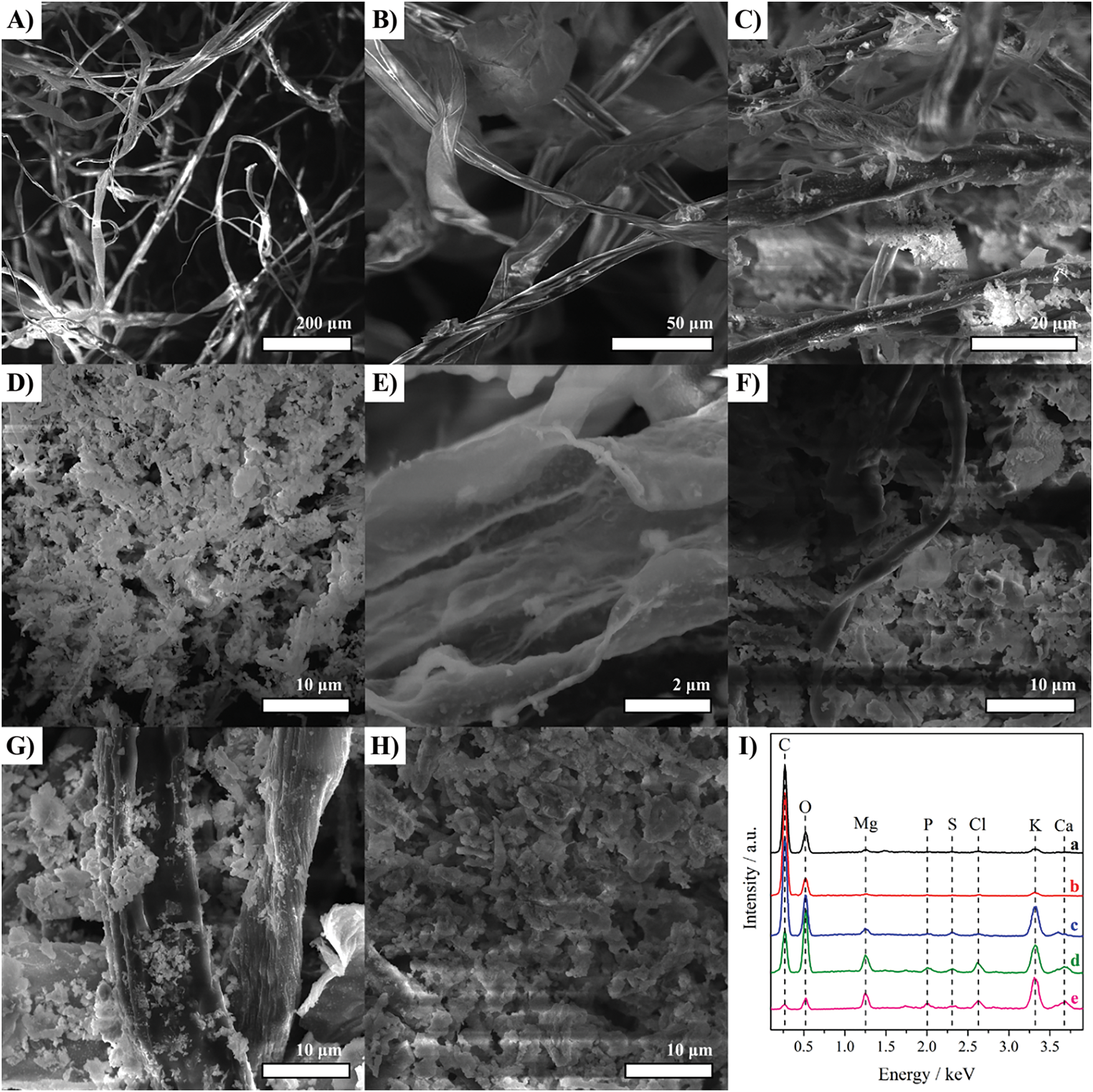

The morphology of cotton biomass-based materials was evaluated by SEM and the images are presented in Fig. 3. As seen in Fig. 3A,B, the raw cotton biomass is composed of long ribbons ranging from 10 to 30 µm. The pyrolyzed materials also exhibited these ribbons depending on the amount of residual carbon in each sample. Besides, they also presented nanoparticles (bright particles) distributed throughout the samples, corresponding to the inorganic compounds identified in the previous characterization techniques (Fig. 2). These nanoparticles ranged between 50 to 150 nm with no defined shape. The EDS spectra (Fig. 3I) corroborate the presence of compounds based on K, S, O, C, Cl, Ca, P, and Mg. Excluding C (related to the ribbons) and O, K exhibited the highest % for all the samples. In addition to the spectra from the wide view, point spectra recorded from each sample indicate that these elements are well distributed (not shown).

Figure 3: (A,B) SEM images of cotton biomass and (C–E) cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 300°C for 60 and (F) 240 min, and (G) 400°C for 1 and (H) 60 min. (I) EDS spectra of cotton biomass (a) and cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 300°C for 60 (b) and 240 min (c), and 400°C for 1 (d) and 60 min (e)

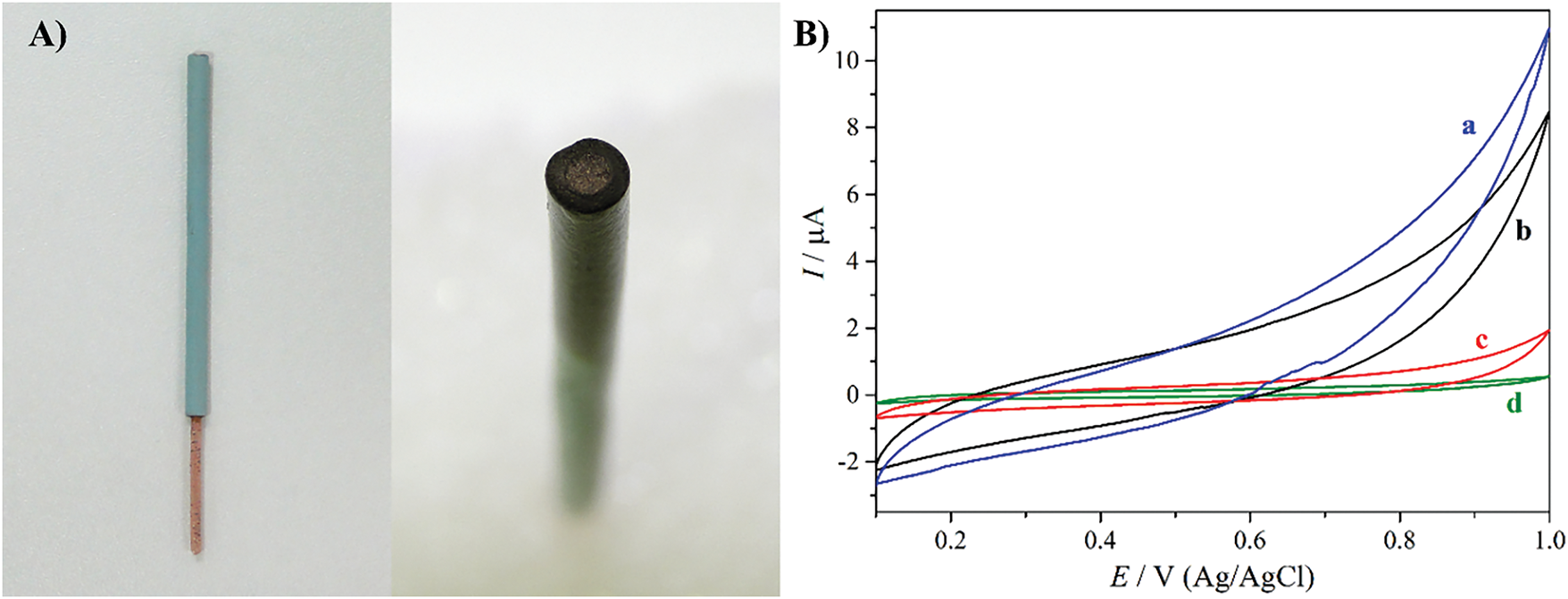

To evaluate the electrochemical response of the biomass-based material, modified carbon paste electrodes (CPE) were prepared (Fig. 4A). The modified CPE was analyzed in 0.1 mol·L−1 PBS solution and the voltammograms are shown in Fig. 4B. None of the pyrolyzed materials showed redox processes in the medium. However, the biomass pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min and 300°C for 240 min exhibited higher capacitive current and solvent oxidation evolution. This behavior is related to the presence of the inorganic compounds described above. Their nanometric size provides a high surface area, enabling the accumulation of more ions on their surface and thus increasing their capacitive behavior. In addition, the higher solvent oxidation for these samples indicates a better electrocatalytic response. The crucial role of these inorganic compounds is confirmed by analyzing the CPE modified with the biomass pyrolyzed at 300°C for 240 min after HCl purification. The absence of the inorganic compounds led to a profile very similar to the non-modified CPE, highlighting their importance.

Figure 4: (A) Photographic image of a modified CPE and (B) 30th voltammetric cycles of CPEs modified with cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min (a) and 300°C for 240 min pristine (b), and after HCl purification (c), and non-modified CPE (d). The cyclic voltammograms were recorded at 50 mV·s−1 in 0.1 mol·L−1 PBS solution

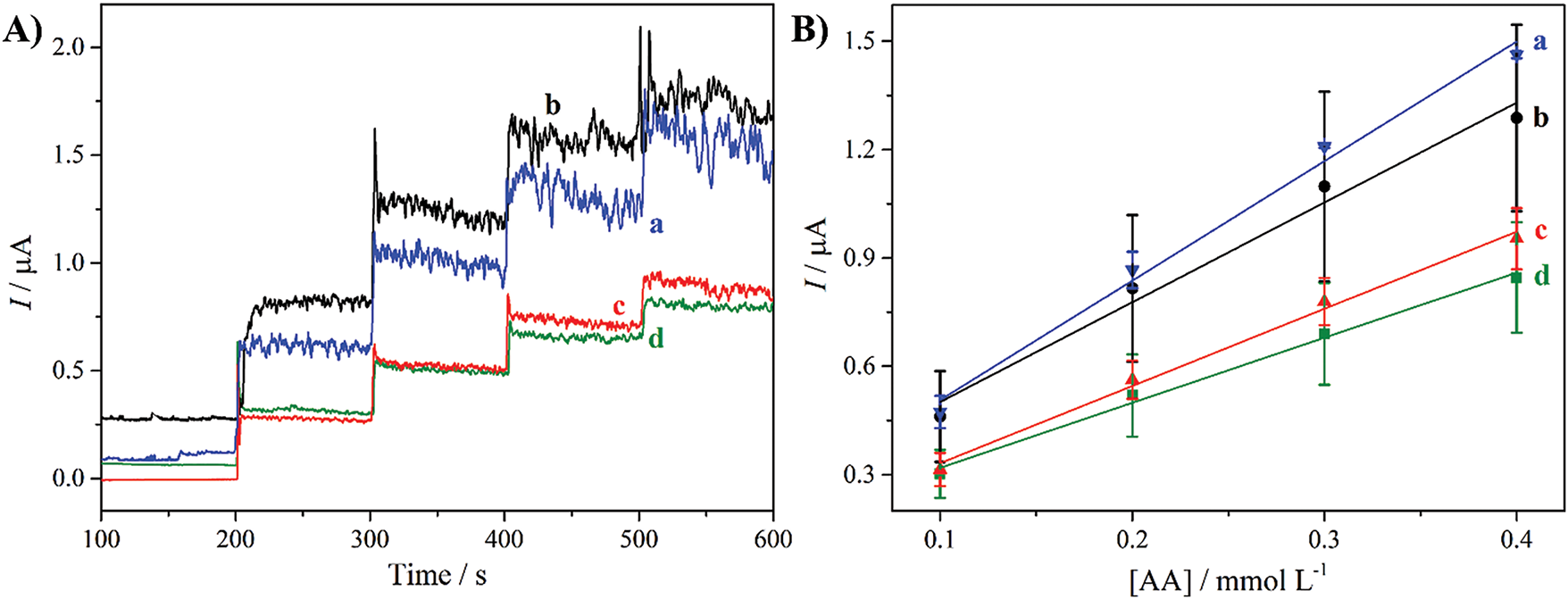

The potential of the biomass-based CPE for electrochemical sensors was evaluated for detecting AA by chronoamperometry (Fig. 5A), applying 0.3 V. This correspond to the optimized potential used in recent studies described by the authors for the detection of AA in PBS (pH 7), using carbon-based materials [35]. All the CPEs presented electrocatalytic response to oxidation of the AA in PBS, evidenced by the current increments for each AA addition. The absence of redox processes in the cyclic voltammograms indicates a direct electrocatalytic mechanism [35]. The analytical curves were constructed based on these current increments as a function of the AA concentration in the electrochemical cell (Fig. 5B). It is evident that the CPE possesses different sensitivities, which correspond to the angular coefficients from the fits of the experimental data. The cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min showed the highest sensitivity (3.31 ± 0.16 μA (mmol·L−1)−1), followed by the materials obtained at 300°C for 240 min, before and after HCl purification, and the nonmodified-CPE (2.76 ± 0.46, 2.14 ± 0.13, and 1.80 ± 0.30 μA (mmol·L−1)−1, respectively). The higher sensitivity exhibited by the cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min is probably due to the higher proportion of inorganic nanoparticles, which increases the electroactive surface area (ECSA) of the CPE. The ECSA values were obtained by cyclic voltammetry analysis in a 1 mmol·L−1 [Fe(CN)6]4− and 0.1 mol·L−1 NaCl aqueous solution, with varying the scan rates (Fig. S1) [36]. The non-modified CPE, and the CPEs modified with cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 300°C for 240 min (pristine and after HCl purification), and at 400°C for 60 min, presented ECSA values of 0.0022, 0.0025, 0.0032, and 0.0042 cm2, respectively. As expected, the cotton biomass-based CPE obtained at 400°C for 60 min showed the highest ECSA, confirming the influence of the inorganic nanoparticles.

Figure 5: (A) Chronoamperograms and (B) analytical curves of CPEs modified with cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min (a) and 300°C for 240 min pristine (b), and after HCl purification (c), and non-modified CPE (d). The chronoamperometries were carried out with 4 consecutive additions of 0.1 mmol·L−1 AA, applying 0.3 V under magnetic stirring

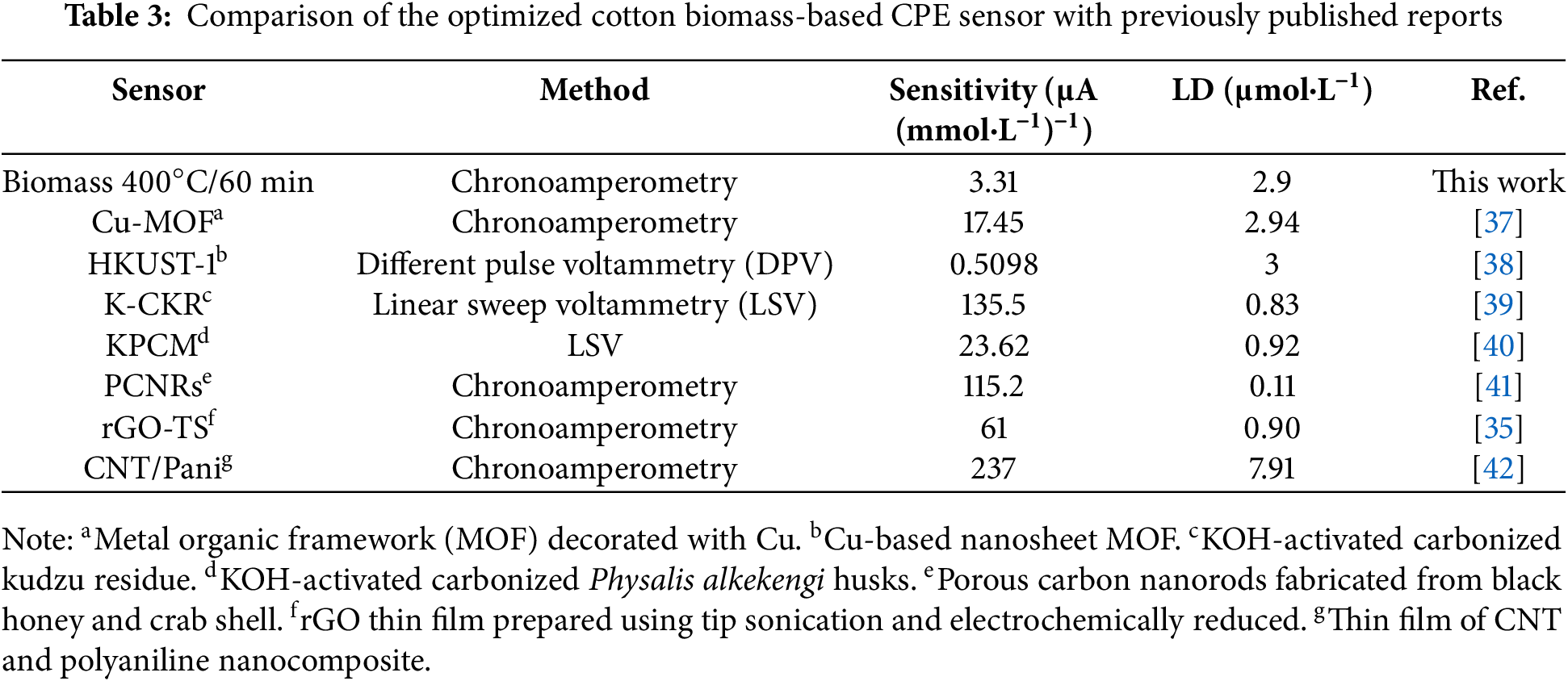

The limit of detection (LD) and the limit of quantification (LQ) were calculated for the cotton biomass residue pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively. Here, s represents the standard deviation of the blank (0.0033 µA) and α the sensitivity (3.31 ± 0.16 μA (mmol·L−1)−1). The LD and LQ values were 2.90 ± 1.87 and 9.66 ± 6.23 μmol·L−1, respectively. These low LD and LQ are quite reasonable when compared with other sensors from the literature for the detection of AA (Table 3). Although the modified CPE was not able to detect lower levels of AA when compared to literature reports, it is worth mentioning that this electroactive material is easy to synthesize and permits facile electrode preparation, making it a promising candidate for this purpose.

The reproducibility and repeatability of the optimized sensor were evaluated in terms of sensitivity (Fig. 6). The reproducibility across six experiments showed satisfactory results, with a standard deviation of 15%, despite one discrepant measurement. Regarding repeatability, the CPE exhibited a decrease in sensitivity for consecutive measurements performed on the same day, indicating that the sensor can be reliably used up to two times. Repeatability across different days was also assessed, and again showed a reduction in sensitivity. These behaviors could be attributed to the leaching of inorganic nanoparticles caused by washing the CPE surface between analyses. Nevertheless, the simple renewal of the CPE surface offsets this limitation, enabling rapid restoration of the electrode.

Figure 6: (A) Reproducibility and (B) repeatability of the CPEs modified with cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min for AA detection in 0.1 mol·L−1 PBS solution, applying 0.3 V. (C) Repeatability across consecutive days. The sensitivities in (A) are expressed as percentages of the mean sensitivity of all experiments, and for (B,C) as percentages of the sensitivity of the first experiment

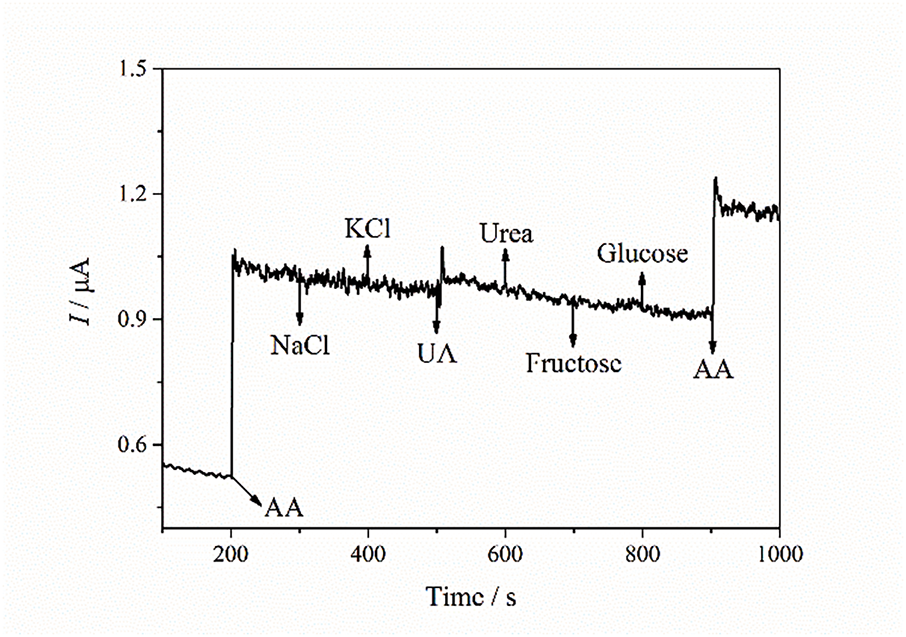

The influence of possible interferents on AA detection using the biomass carbon-based CPE was evaluated for NaCl, KCl, UA, urea, fructose, and glucose (Fig. 7). It is evident that the developed sensor is selective for AA detection, as no current signal was recorded for the other compounds. However, the last AA addition resulted in a lower current increase (0.25 µA) compared to the first addition (0.51 µA), despite having the same concentration. This behavior is likely due to the high concentration of other species in the medium (a total of 6 mmol·L−1), which may hinder the access of AA to the electrode surface.

Figure 7: Chronoamperogram of the CPEs modified with cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min with additions of 0.1 mmol·L−1 AA and 1 mmol·L−1 NaCl, KCl, UA, urea, fructose, glucose, and 0.1 mmol·L−1 AA

Carbon-based nanomaterials were produced by the pyrolysis of cotton biomass residue. The morphological and structural characteristics of the inorganic nanoparticles, as well as their mass ratio within the carbonaceous matrix, were directly dependent on the temperature and time of pyrolysis. Their electroanalytical potential for the detection of AA in PBS was evaluated by constructing CPEs. The carbon-based nanomaterials showed electroactivity for the analyte detection, which was dependent on the inorganic nanoparticles’ ratio. The cotton biomass pyrolyzed at 400°C for 60 min presented the highest sensitivity, leading to low LD and LQ of 2.90 ± 1.87 and 9.66 ± 6.23 μmol·L−1, respectively. The optimized CPE also demonstrated very good reproducibility and selectivity, although it could be used reliably only twice. The good electroanalytical performance of this cotton biomass-based CPE, associated with its easy obtention and preparation, makes it a promising sensor for AA detection.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank CLAIMS-FURB MultiLab-SC for FT-IR and TGA analyses. The authors thank professor Dr. Aldo José Gorgatti Zarbin and the Materials Chemistry Group-UFPR for the SEM/EDS and XRD analyses.

Funding Statement: The authors acknowledge the financial support of Brazilian agencies FAPESC/ACAFE, CAPES, CNPq and Nationals Institutes of Science and Technology of Carbon Nanomaterials (INCT-Nanocarbon, 421701/2017-0) and Nanomaterials for Life (INCT NanoLife, 406079/2022-6). J.P.M.C.A. acknowledges his scientific initiation (PIBIT) grant from CNPq, D.O.S. thanks CAPES for his post-doctoral grant (PNPD/CAPES 2017-2019), J.A. is grateful for his grant from CNPq (CNPq 303633/2023-9) and the financial support from FAPESC through various projects (contracts: 2018TR1546, 2023TR001521 and 2024TR002662). A.E.S. and E.T.F. thank FAPESC for the research fellowships, respectively.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software and Visualization: Anna Elisa Silva, Eduardo Thiago Formigari, Eduardo Guilherme Cividini Neiva; Chemical characterization of the cotton residues: João Pedro Mayer Camacho Araújo, Dagoberto de Oliveira Silva; Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing: Anna Elisa Silva, Eduardo Guilherme Cividini Neiva, Jürgen Andreaus; Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision: Eduardo Guilherme Cividini Neiva, Jürgen Andreaus. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Eduardo Guilherme Cividini Neiva, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0130/s1.

References

1. Lu L, Fan W, Meng X, Xue L, Ge S, Wang C, et al. Current recycling strategies and high-value utilization of waste cotton. Sci Total Environ. 2023;856:158798. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Pandirwar AP, Khadatkar A, Mehta CR, Majumdar G, Idapuganti R, Mageshwaran V, et al. Technological Advancement in harvesting of cotton stalks to establish sustainable raw material supply chain for industrial applications: a review. BioEnergy Res. 2023;16(2):741–60. doi:10.1007/s12155-022-10520-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Primaz CT, Ribes-Greus A, Jacques RA. Valorization of cotton residues for production of bio-oil and engineered biochar. Energy. 2021;235(8):121363. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.121363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Holtz M, Borges GM, Furlan SA, Wisbeck E. Cultivo de Pleurotus ostreatus utilizando resíduos de algodão da indústria têxtil. Rev Cien Amb. 2009;3(1):37–51. (In Portuguese). doi:10.18316/113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Adeniyi AG, Iwuozor KO, Emenike EC, Sagboye PA, Micheal KT, Micheal TT, et al. Biomass-derived activated carbon monoliths: a review of production routes, performance, and commercialization potential. J Clean Prod. 2023;423(47):138711. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Sekhon SS, Kaur P, Park J-S. From coconut shell biomass to oxygen reduction reaction catalyst: tuning porosity and nitrogen doping. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;147:111173. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Saha K, Deka J, Kumar A, Mondal M, Bora BR, Bakli C, et al. Carbonized cotton fibers for ultrahigh power-density electrokinetic energy harvesting. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2024;7(1):176–85. doi:10.1021/acsaem.3c02409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Umair MM, Zhang Y, Tehrim A, Zhang S, Tang B. Form-stable phase-change composites supported by a biomass-derived carbon scaffold with multiple energy conversion abilities. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2020;59(4):1393–401. doi:10.1021/acs.iecr.9b06288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dhiman N, Sharma V, Ghosh S. Perspective on biomass-based cotton-derived nanocarbon for multifunctional energy storage and harvesting applications. ACS Appl Electron Mater. 2023;5(4):1970–91. doi:10.1021/acsaelm.3c00022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Potham S, Ramanujam K. A novel hierarchical porous activated carbon-organic composite cathode material for high performance aqueous zinc-ion hybrid supercapacitors. J Power Sources. 2023;557:232551. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2022.232551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang S, Dai P, Liu H, Yan L, Song H, Liu D, et al. Nanoantenna featuring carbon microtubes derived from bristle fibers of plane trees for supercapacitors in an organic electrolyte. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2020;3(12):12627–34. doi:10.1021/acsaem.0c02540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Njus D, Kelley PM, Tu Y-J, Schlegel HB. Ascorbic acid: the chemistry underlying its antioxidant properties. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;159:37–43. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.07.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Moon KM, Kwon E-B, Lee B, Kim CY. Recent trends in controlling the enzymatic browning of fruit and vegetable products. Molecules. 2020;25(12):2754. doi:10.3390/molecules25122754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bhoot HR, Zamwar UM, Chakole S, Anjankar A, Bhoot H. Dietary sources, bioavailability, and functions of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and its role in the common cold, tissue healing, and iron metabolism. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e49308. doi:10.7759/cureus.49308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Rondanelli M, Peroni G, Fossari F, Vecchio V, Faliva MA, Naso M, et al. Evidence of a positive link between consumption and supplementation of ascorbic acid and bone mineral density. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):1012. doi:10.3390/nu13031012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Gęgotek A, Skrzydlewska E. Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activity of ascorbic acid. Antioxidants. 2022;11(10):1993. doi:10.3390/antiox11101993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Sabatier M, Rytz A, Husny J, Dubascoux S, Nicolas M, Dave A, et al. Impact of ascorbic acid on the in vitro iron bioavailability of a casein-based iron fortificant. Nutrients. 2020;12(9):2776. doi:10.3390/nu12092776. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Liebling EJ, Sze RW, Behrens EM. Vitamin C deficiency mimicking inflammatory bone disease of the hand. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2020;18(1):45. doi:10.1186/s12969-020-00439-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Wang Y, Xu Y, Zhao G, Zheng Y, Han Q, Xu X, et al. Utilization of nitrogen self-doped biocarbon derived from soybean nodule in electrochemically sensing ascorbic acid and dopamine. J Porous Mater. 2021;28(2):529–41. doi:10.1007/s10934-020-01018-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bi Y, Hei Y, Wang N, Liu J, Ma C-B. Synthesis of a clustered carbon aerogel interconnected by carbon balls from the biomass of taros for construction of a multi-functional electrochemical sensor. Anal Chim Acta. 2021;1164:338514. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2021.338514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Ahmed J, Faisal M, Algethami JS, Alsaiari M, Jalalah M, Harraz FA. CeO2·ZnO@biomass-derived carbon nanocomposite-based electrochemical sensor for efficient detection of ascorbic acid. Anal Biochem. 2024;692:115574. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2024.115574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Santhosh AS, Sandeep S, James Bound D, Nandini S, Nalini S, Suresh GS, et al. A multianalyte electrochemical sensor based on cellulose fibers with silver nanoparticles composite as an innovative nano-framework for the simultaneous determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine and paracetamol. Surf Interfaces. 2021;26(9):101377. doi:10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li W, Guo F, Zhao Y, Liu Y. A sustainable and low-cost route to design NiFe2O4 Nanoparticles/biomass-based carbon fibers with broadband microwave absorption. Nanomater. 2022;12(22):4063. doi:10.3390/nano12224063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sluiter A, Hames B, Hyman D, Payne C, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, et al. Determination of total solids in biomass and total dissolved solids in liquid process samples. Golden, CO, USA: National Renewable Energy Laboratory; 2008. Contract No.: NREL/TP-510-42621. [Google Scholar]

25. Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D, et al. Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Golden, CO, USA: National Renewable Energy Laboratory; 2012. Contract No.: NREL/TP-510-42618. [Google Scholar]

26. Fockink DH, Andreaus J, Ramos LP, Łukasik RM. Pretreatment of cotton spinning residues for optimal enzymatic hydrolysis: a case study using green solvents. Renew Energy. 2020;145(20):490–9. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.06.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Agblevor FA, Batz S, Trumbo J. Composition and ethanol production potential of cotton gin residues. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2003;105:219–30. doi:10.1385/ABAB:105:1-3:219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Jeoh T, Agblevor FA. Characterization and fermentation of steam exploded cotton gin waste. Biomass Bioenerg. 2001;21(2):109–20. doi:10.1016/S0961-9534(01)00028-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. de Siqueira FG, de Siqueira EG, Jaramillo PMD, Silveira MHL, Andreaus J, Couto FA, et al. The potential of agro-industrial residues for production of holocellulase from filamentous fungi. Int Biodeter Biodegr. 2010;64(1):20–6. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2009.10.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sartova K, Omurzak E, Kambarova G, Dzhumaev I, Borkoev B, Abdullaeva Z. Activated carbon obtained from the cotton processing wastes. Diam Relat Mater. 2019;91(3):90–7. doi:10.1016/j.diamond.2018.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Patil SS, Patil PS. 3D Bode analysis of nickel pyrophosphate electrode: a key to understanding the charge storage dynamics. Electrochim Acta. 2023;451(6):142278. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2023.142278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yang P, Yang H, Wang N, Du C, Pang S, Zhang Y. Hygroscopicity measurement of sodium carbonate, β-alanine and internally mixed β-alanine/Na2CO3 particles by ATR-FTIR. J Environ Sci. 2020;87(7):250–9. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2019.07.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Vidya YS, Lakshminarasappa BN. Preparation, characterization, and luminescence properties of orthorhombic sodium sulphate. Phys Res Int. 2013;2013(1):641631. doi:10.1155/2013/641631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Pan Y, Wang W, Liu L, Ge H, Song L, Hu Y. Influences of metal ions crosslinked alginate based coatings on thermal stability and fire resistance of cotton fabrics. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;170(3):133–9. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.04.065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Silva AE, Zeplin G, Neiva EGC. Controlling of graphene size for better electrochemical sensors. Mater Sci Eng B. 2025;321:118527. doi:10.1016/j.mseb.2025.118527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Silva AE, de Souza VHR, Neiva EGC. Crumpled graphene/Ni(OH)2 nanocomposites applied as electrochemical sensors for glucose and persistent contaminants. Appl Surf Sci. 2023;622:156967. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.156967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ling W, Hao Y, Wang H, Xu H, Huang X. A novel Cu-metal-organic framework with two-dimensional layered topology for electrochemical detection using flexible sensors. Nanotechnol. 2019;30(42):424002. doi:10.1088/1361-6528/ab30b6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Shen T, Liu T, Mo H, Yuan Z, Cui F, Jin Y, et al. Cu-based metal-organic framework HKUST-1 as effective catalyst for highly sensitive determination of ascorbic acid. RSC Adv. 2020;10(39):22881–90. doi:10.1039/D0RA01260B. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Dai J, Huang JH, Xiong YQ, Gao LF. Electrochemical sensing platform for ascorbic acid detection based on porous carbon derived from kudzu root residues. ChemistrySelect. 2024;9(34):e202402313. doi:10.1002/slct.202402313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Jin B, Liu S, Jin D. Electrochemical sensor based on carbon material derived from Physalis alkekengi L. husks for the analysis of ascorbic acid. Asia-Pac J Chem. 2023;18(2):e2871. doi:10.1002/apj.2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Liao L, Ding J, Xu Y, Ma T, Fang T, Li S, et al. Sustainable strategy for fabricating porous carbon nanorods with enhanced electroactivity for determination of ascorbic acid. Waste Biomass Valori. 2024;16(6):3253–65. doi:10.1007/s12649-024-02868-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Lisboa FS, Neiva EGC, Bergamini MF, Marcolino Junior LH, Zarbin AJG. Evaluation of carbon nanotubes/polyaniline thin films for development of electrochemical sensors. J Braz Chem Soc. 2020;31:1093–100. doi:10.21577/0103-5053.20190274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools