Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Characteristics of Three Bamboo Species and Their Potential as Raw Materials for Oriented Strand Board Production

1 Department of Forest Products, Faculty of Forestry, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Medan, 20155, Indonesia

2 Centre of Excellence for Bamboo (PUI Bamboo), Universitas Sumatera Utara, Kampus USU Padang Bulan, Medan, North Sumatra, 20155, Indonesia

3 Department of Forest Management, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Ir Sutami 36A, Surakarta, 57126, Indonesia

4 Research Center for Biomass and Bioproducts, National Research and Innovation Agency, Cibinong, 16911, Indonesia

5 School of Life Sciences and Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Gedung Labtex XI, Jalan Ganesha 10, Bandung, 40132, Indonesia

6 Department of Furniture Design, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Technology, Poznan University of Life Sciences, ul. Wojska Polskiego 38/42, Poznan, 60627, Poland

7 Department of Wood Industry, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Cawangan Pahang Kampus Jengka, Shah Alam, 26400, Malaysia

8 Tropical Wood and Biomass Research Group, Faculty of Bioengineering and Technology, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Jeli Campus, Jeli, Kelantan, 17600, Malaysia

9 Faculty of Forest Industry, University of Forestry, Sofia, 1797, Bulgaria

* Corresponding Author: Apri Heri Iswanto. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Eco-friendly Wood-Based Composites: Design, Manufacturing, Properties and Applications – Ⅱ)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(11), 2253-2279. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0058

Received 27 April 2025; Accepted 20 May 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Indonesia, with its vast forested regions, has experienced significant deforestation, adversely affecting the wood industry. As a result, alternative sources of lignocellulosic biomass are required to mitigate this impact. Among the abundant lignocellulosic raw materials in Indonesia, particularly in Sumatra, bamboo stands out as a promising substitute. Bamboo is a highly versatile resource, suitable for various applications, including its use as a composite raw material to replace traditional wood-based products. This research work aimed to investigate and evaluate the characteristics—morphology, anatomy, physical and mechanical properties, chemical composition, starch content, and natural resistance—of three bamboo species: hitam bamboo (Gigantochloa atroviolacea), betung bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper), and belangke bamboo (Gigantochloa pruriens), as well as their suitability for the production of oriented strand boards (OSB). The lumen values of the bamboo samples ranged between 10 and 15 μm, with hitam and betung bamboo exhibiting medium-thickness cell walls (>5 μm). Based on fiber dimension analysis, belangke, and betung bamboo are classified within quality class II, whereas hitam bamboo falls into class I. The highest recorded tensile, shear, and compressive mechanical strength values were observed at the tips of hitam bamboo, measuring 563.43 MPa, 15 MPa, and 6.87 kN/mm2, respectively. The bamboo samples underwent three different treatments: (1) immersion in water for 24 h, (2) autoclaving at 120°C for 1 h, and (3) a control group with no treatment. OSB panels were produced with dimensions of 20 cm × 20 cm × 1 cm (length × width × thickness) using isocyanate adhesive and conditioned for 14 days. The physical and mechanical properties of the OSBs were evaluated based on the Japan Industrial Standard (JIS) A 5908:2003 and the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) 0437.0:2011 criteria. The density of the laboratory-produced OSB panels ranged from 0.60 to 0.73 g/cm3, moisture content varied from 5.4% to 8.1%, water absorption ranged between 31.6% and 45.8%, and thickness swelling was recorded at 5.1% to 16.3%. The modulus of elasticity (MOE) ranged from 2745.1 to 7813.3 MPa, the modulus of rupture (MOR) from 30.8 to 58.8 MPa, and internal bonding (IB) from 0.27 to 0.47 MPa. Overall, all OSB panels produced in this study met the specifications outlined in JIS A 5908 (2003) and CSA 0437.0 (2011), demonstrating the viability of these bamboo species as raw materials for OSB production.Keywords

Indonesia is home to one of the largest forested areas globally, ranking third in tropical forest coverage after Brazil and the Democratic Republic of the Congo [1]. According to data from the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), the country experienced deforestation amounting to 113.5 thousand hectares between 2020 and 2022, underscoring the ongoing environmental challenges and the necessity of sustainable forest management strategies [2]. Deforestation has significantly impacted the timber industry by reducing the availability of wood, necessitating the exploration of alternative lignocellulosic biomass sources as substitutes. Among various non-wood lignocellulosic feedstocks, bamboo stands out as an abundant yet underutilized resource. Indonesia is home to 156 bamboo species, with 88 (56% of the total) classified as endemic, meaning they are found exclusively within the country. The considerable diversity of bamboo species presents significant opportunities for optimized utilization. Currently, the island of Sumatra is the center of Indonesian bamboo biodiversity with the greatest number of endemic species compared with other islands in Indonesia, namely, 80 species, 32 of which are endemic Widjaja species [3].

The inherent nature and characteristics of bamboo play a crucial role in determining its optimal applications. Due to morphological similarities, bamboo species can be challenging to distinguish visually [4]. The properties of bamboo are influenced by various factors, including species variation, growth location, and topographical conditions. Several key factors impact the fundamental physical and mechanical attributes of bamboo, such as age, height position, diameter, specific gravity, and moisture content [5]. Bamboo serves as a highly versatile material, widely utilized across multiple industries, including art equipment, furniture production, traditional crafts, lightweight construction, and composite materials. Notably, bamboo fibers have been incorporated into polymer composite products to enhance reinforcement properties. One prominent bamboo-based composite product currently under development is an oriented strand board (OSB) [6]. Maulana et al. [7] describe OSB as a structural composite panel that serves as a viable alternative to plywood in various applications. A key advantage of using belangke bamboo (Gigantochloa pruriens), hitam bamboo (Gigantochloa atroviolacea), and betung bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper) in this study is their native presence in North Sumatra. The utilization of these locally available bamboo species presents an opportunity for optimizing indigenous plant resources as raw materials for composite production, contributing to more sustainable manufacturing practices [8].

Multiple studies have demonstrated that OSB panels fabricated from betung and belangke bamboo exhibit the following physical properties: density values ranging from 0.70 to 0.71 g/cm3, moisture content between 10.12% and 11.36%, thickness swelling from 10.74% to 13.97%, and water absorption ranging from 29.52% to 31.45% [9]. These results surpass those of wood-based OSB and comply with the commercial OSB requirements established by the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) 0437.0 (Grade O-1) [10]. Despite its advantages, bamboo remains vulnerable to biological degradation. Huang et al. [11] reported that bamboo is susceptible to various harmful organisms, including blue mold, ambrosia beetles, dry wood termites, and dry wood dust when utilized in composite applications. Additionally, the high starch content of bamboo can present challenges during the gluing process [12]. To mitigate these limitations, modifications or treatments of raw materials are essential to enhance OSB properties. Several studies indicate that steam treatment is more effective than other treatment methods in improving board resistance and dimensional stability [9,13].

Beyond its industrial applications, bamboo plays a crucial role in environmental conservation, particularly in soil improvement and land rehabilitation. The plant’s extensive root system, biochar potential, and contributions to organic matter offer significant benefits for enhancing soil properties, making bamboo an essential resource for sustainable land management. One of bamboo’s key contributions to soil improvement is its extensive root network, which helps prevent soil erosion and enhances soil structure. Bamboo roots create a dense matrix that stabilizes the soil, making them highly effective for slope protection and erosion control in degraded landscapes [14]. Additionally, fallen bamboo leaves and decaying roots contribute organic matter that enriches soil fertility, improving nutrient retention capacity [15]. This natural process supports sustainable agriculture by reducing dependence on chemical fertilizers, further promoting soil health and long-term productivity. In addition to organic enrichment, bamboo-derived biochar has been identified as a valuable soil amendment. Biochar, produced through the pyrolysis of bamboo biomass, improves soil porosity, enhances water retention, and increases cation exchange capacity—factors that collectively contribute to improved soil fertility and plant growth [16]. Studies indicate that the incorporation of bamboo biochar into acidic soils significantly enhances soil pH and nutrient availability, making it an effective approach for land restoration and agricultural sustainability [17]. These findings highlight bamboo’s dual contribution—its potential as a raw material for OSB, an engineered wood product offering sustainability advantages over conventional timber, and its role in ecological conservation through soil rehabilitation and sustainable land management.

While numerous studies have examined bamboo as a raw material in the processed wood industry, research on its application in OSB production remains relatively limited. Furthermore, there is a gap in understanding how variations in the physical and mechanical properties of different bamboo species influence OSB performance. Previous studies have largely focused on specific bamboo species without fully considering the effects of species variation and initial treatments on adhesion and durability in OSB manufacturing. Additionally, limited research has explored the optimal integration of bamboo fiber with environmentally friendly adhesives in OSB production, highlighting opportunities for further investigation to enhance the dimensional stability and mechanical durability of OSB panels. Thus, the objective of this study was to investigate and evaluate the characteristics—morphology, anatomy, physical and mechanical properties, chemical composition, starch content, and natural resistance—of three endemic bamboo species from North Sumatra: hitam bamboo (Gigantochloa atroviolacea), belangke bamboo (Gigantochloa pruriens), and betung bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper), as well as their suitability for OSB production.

The materials used in this study were bamboo betung (Dendrocalamus asper), hitam bamboo (Gigantochloa atroviolacea), belangke bamboo (Gigantochloa pruriens), hot water, cold water, ethanol benzene 1:2, NaOH 17% and 8.3%, CH3COOH 10%, H2SO4 72%, NaClO2 25% and acetone, sulfuric acid solution (H2SO4) 1.25%, 25% and 75%, NaOH solution 3.25%, phenolphthalein indicator solution (PP), and Luff-Schoorl solution in starch testing. Isocyanate adhesive (solids content 99.5% and viscosity 212.4 mPa), produced by Poly Oshika Co., Ltd. in Tokyo, Japan and supplied by PT. Polikimia Asia Pasifik Permai (Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia) was used for bonding the OSB boards.

2.2 Morphological Study of Bamboo

Bamboo plant samples were obtained using the exploration method, with specimens collected directly from the field [3]. The observed characteristics included tube shape, coloration, and length. Additionally, the branching patterns of each bamboo-segment were recorded, along with the shape and size of the stalk and the surface morphology of the leaves for each species.

2.3 Anatomical Structure of Bamboo

Test samples were collected from both the nodes and internodes of bamboo to examine key structural parameters. The observed characteristics included the arrangement of bamboo shoot tissue and the anatomical features of mature bamboo stems at the internodes. To prepare transverse sections of bamboo shoots, samples were obtained from young shoots and mature stems of three bamboo species. The bamboo specimens were cut, followed by the removal of both outer and inner layers. The prepared samples were then sectioned into pieces measuring 2 cm × 2 cm × 1 cm. These specimens were subsequently placed on slides and examined under a microscope [18].

2.4 Physical Properties of Bamboo

The physical property tests were conducted following the ISO 22157: 2019 standard [19], with sample dimensions of 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 1 cm. These tests assessed moisture content, specific gravity, and shrinkage. The moisture content test involved measuring the initial weight of the bamboo (BB) before placing it in an oven at 103 ± 2°C for 24 h. After drying, the weight was measured again (BKT) to determine moisture loss. Specific gravity was calculated by comparing the mass of bamboo to its volume under air-dry conditions. For the shrinkage test, bamboo column samples measuring 10 cm in both height and length were analyzed. The outer diameter (dl), inner diameter (dd), and bamboo linearity (p) were recorded under air-dry conditions. The samples were then subjected to further drying in an oven at 103 ± 2°C to evaluate dimensional changes.

2.5 Mechanical Properties of Bamboo

The mechanical properties of bamboo were evaluated by the Japanese standard JIS A 5908 (2003) [20]. The compression test sample dimensions were adjusted based on the bamboo’s outer diameter (dl). Specifically, the height and length of the sample were equal to its outer diameter. For bamboo specimens with a diameter of less than 2 cm, the sample height was set to twice the outer diameter to ensure accurate assessment. Tensile test samples were prepared following the specifications outlined in the ISO 22157: 2019 standard [19].

2.6 Chemical Properties of Bamboo

The raw materials were prepared by the testing standards established by the Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry (TAPPI, Peachtree Corners, GA, USA), specifically TAPPI T 257 cm-02 and TAPPI T 264 cm-97. Several modifications based on previous studies were incorporated to optimize the preparation process [21,22]. Betung and hitam bamboo were selected for analysis. Each test sample was processed using a ring flaker, hammer mill, or disk mill until it passed through a No. 40–60 mesh sieve. The samples were then either air-dried or oven-dried at a maximum temperature of 40°C if residual moisture was present. Subsequently, the chemical composition of the bamboo samples was assessed through a series of tests, including extractive content analysis, ash content determination, lignin content evaluation, holocellulose quantification, and α-cellulose assessment. These analyses were conducted using five distinct methods based on the specified determination procedures.

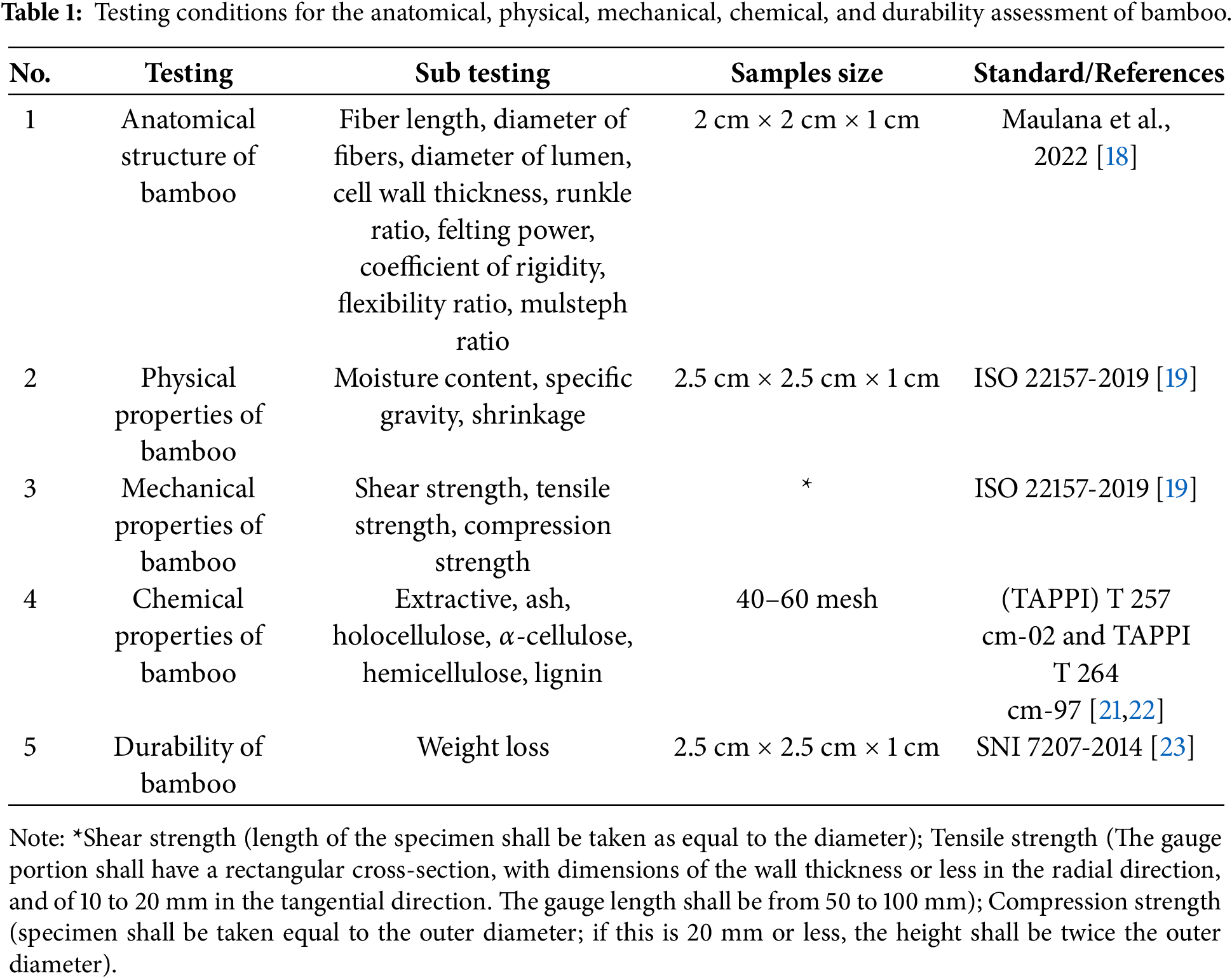

This test was conducted following the SNI 7207-2014 standard [23], which outlines laboratory procedures for assessing the resistance of wood, including bamboo, against subterranean termites. The samples were prepared with dimensions of 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 0.5 cm and were randomly selected from three bamboo species, with five repetitions per species. The testing conditions for the anatomical, physical, mechanical, chemical, and durability assessment of bamboo are shown in Table 1.

2.8 Preparation of the Raw Materials for Manufacturing Oriented Strand Board (OSB)

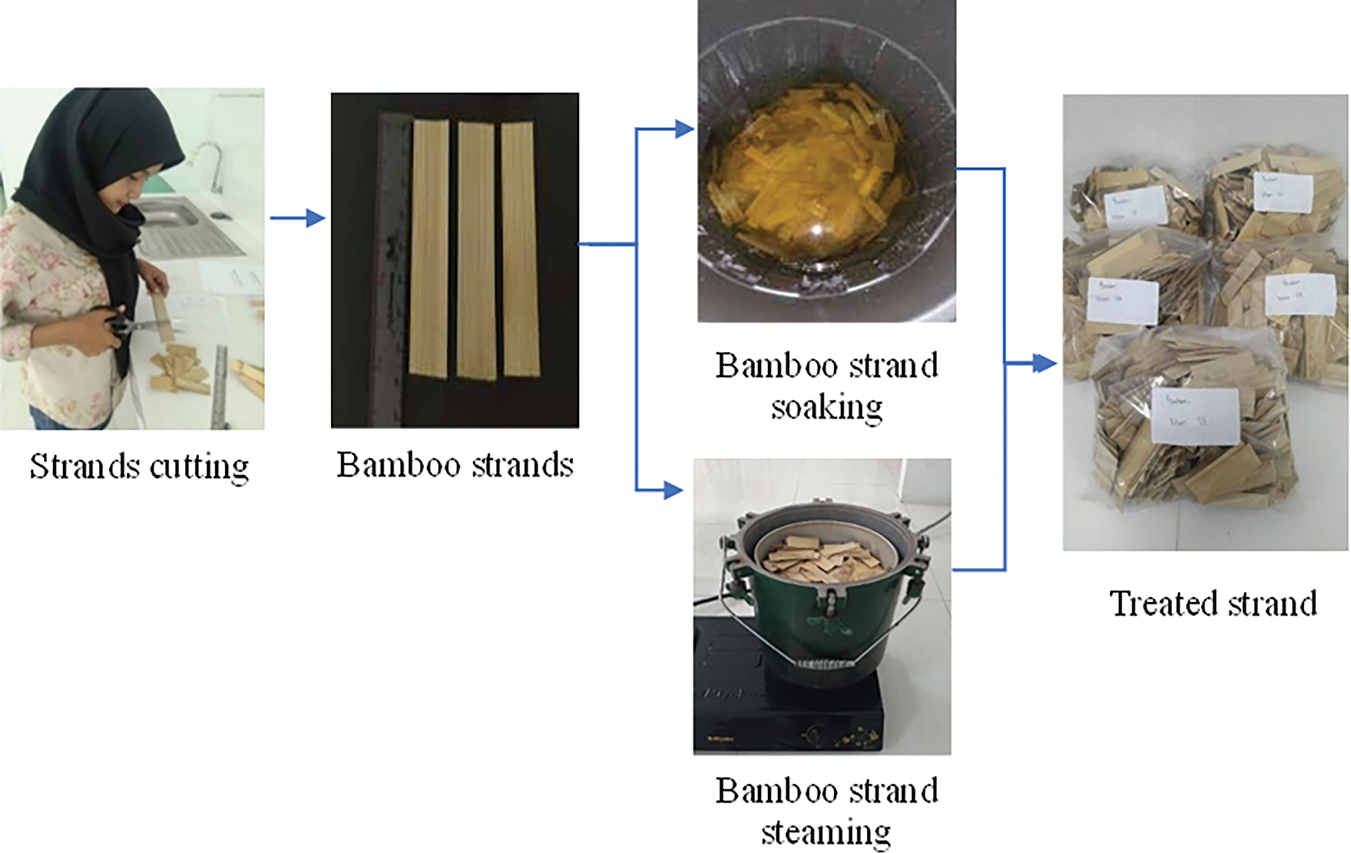

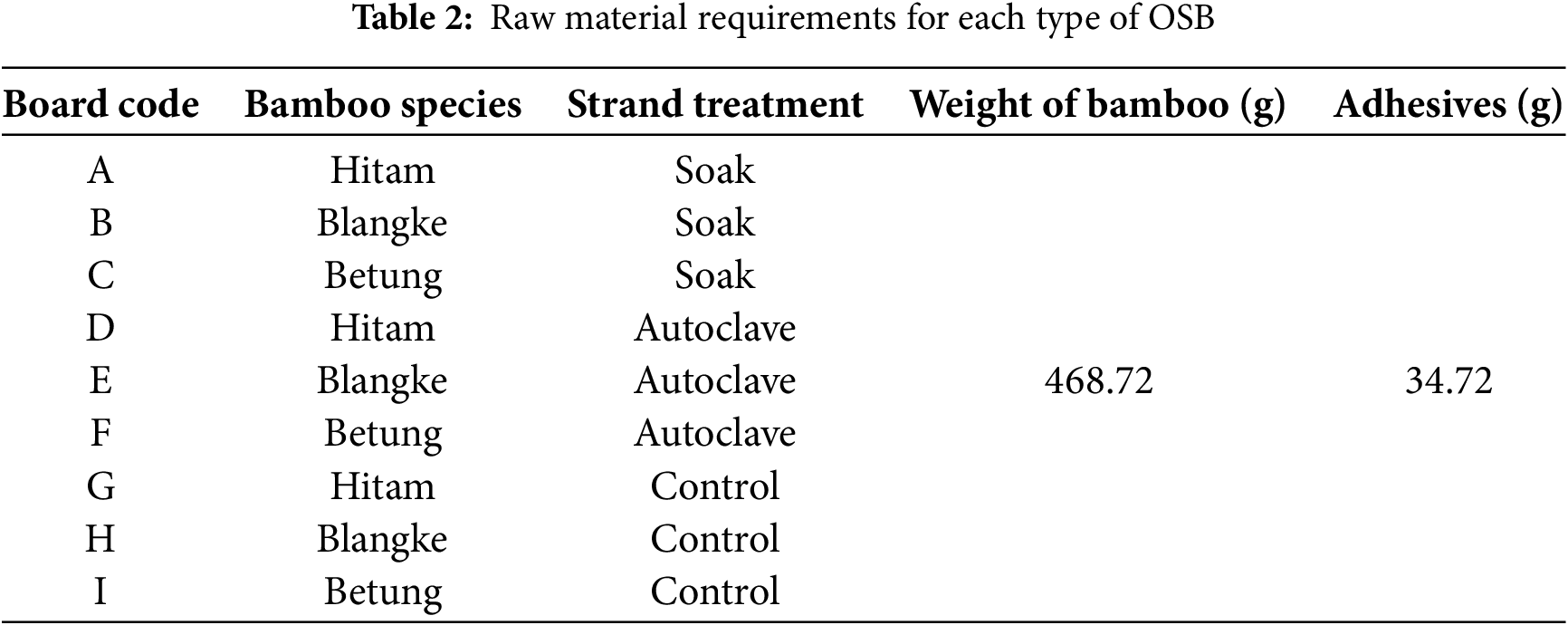

The bamboo strands used in this work measured 7.5 cm in length, 2.5 cm in width, and 0.1 cm in thickness. To enhance the properties of OSB, the strands underwent a pretreatment process involving immersion in cold water for 24 h. Each bamboo type was soaked separately in a 40 L bucket. Additionally, an autoclave treatment was conducted for 1 h at a temperature of 120°C without prior soaking, serving as the control condition. Following the initial treatment, the samples were oven-dried until the moisture content reached 8% (Fig. 1). Under laboratory conditions, OSB panels were fabricated with dimensions of 25 cm × 25 cm × 1 cm and a target density of 0.75 g/cm3. The panels were composed of 8% adhesive by weight. Table 2 provides details on the raw material quantities required for OSB panel production.

Figure 1: Raw material preparation and strand treatment scheme

The strands were mixed with 8% isocyanate adhesive and then arranged in a 25 × 25 cm2 mold with a perpendicular orientation between layers. Hot-pressing was carried out at a temperature of 160°C for 7 min at a pressure of 4.4 MPa. These hot press parameters were determined based on preliminary trials for OSB panel fabrication under laboratory conditions. A total of 27 boards were produced using three different bamboo species. These boards underwent three distinct treatment processes, with the entire experimental procedure repeated three times (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Manufacturing scheme of the OSB board

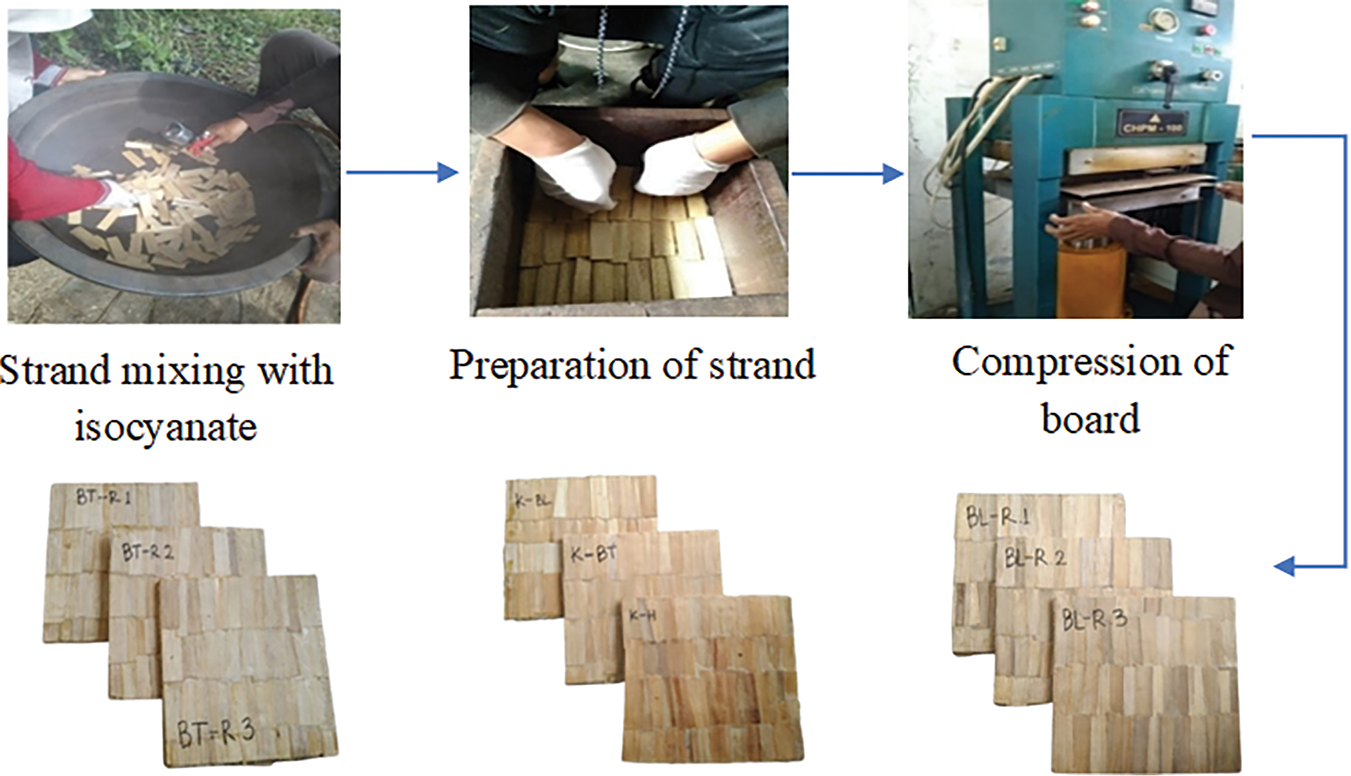

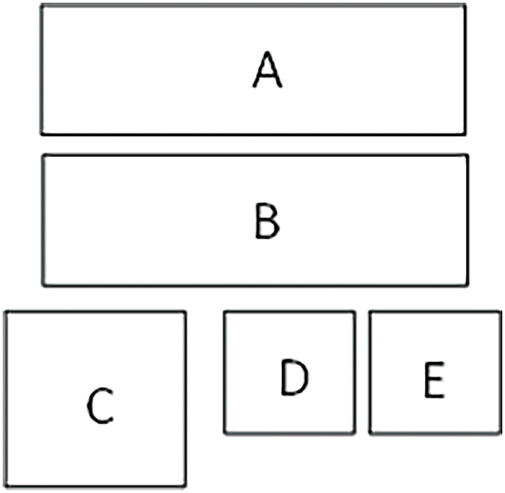

Following a 14-day conditioning process, the boards were cut into test samples of varying dimensions in accordance with the JIS A 5908 (2003) [20] standard. These samples were subjected to physical property evaluations, including density, moisture content, water absorption, and thickness swelling assessments. Additionally, mechanical property testing was conducted to determine internal bonding (IB) strength, modulus of rupture (MOR), and modulus of elasticity (MOE). Seven different testing methodologies were employed for each determination, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Dimensions of test specimen. (A) = Size 20 cm × 5 cm for the MOE and MOR test samples. (B) = Size 20 cm × 5 cm for the MOE and MOR test samples. (C) = Size 10 cm × 10 cm for density and moisture content test samples. (D) = Size 5 cm × 5 cm for the internal bonding (IB) test samples. (E) = Size 5 cm × 5 cm for the water absorption and thickness swelling test samples

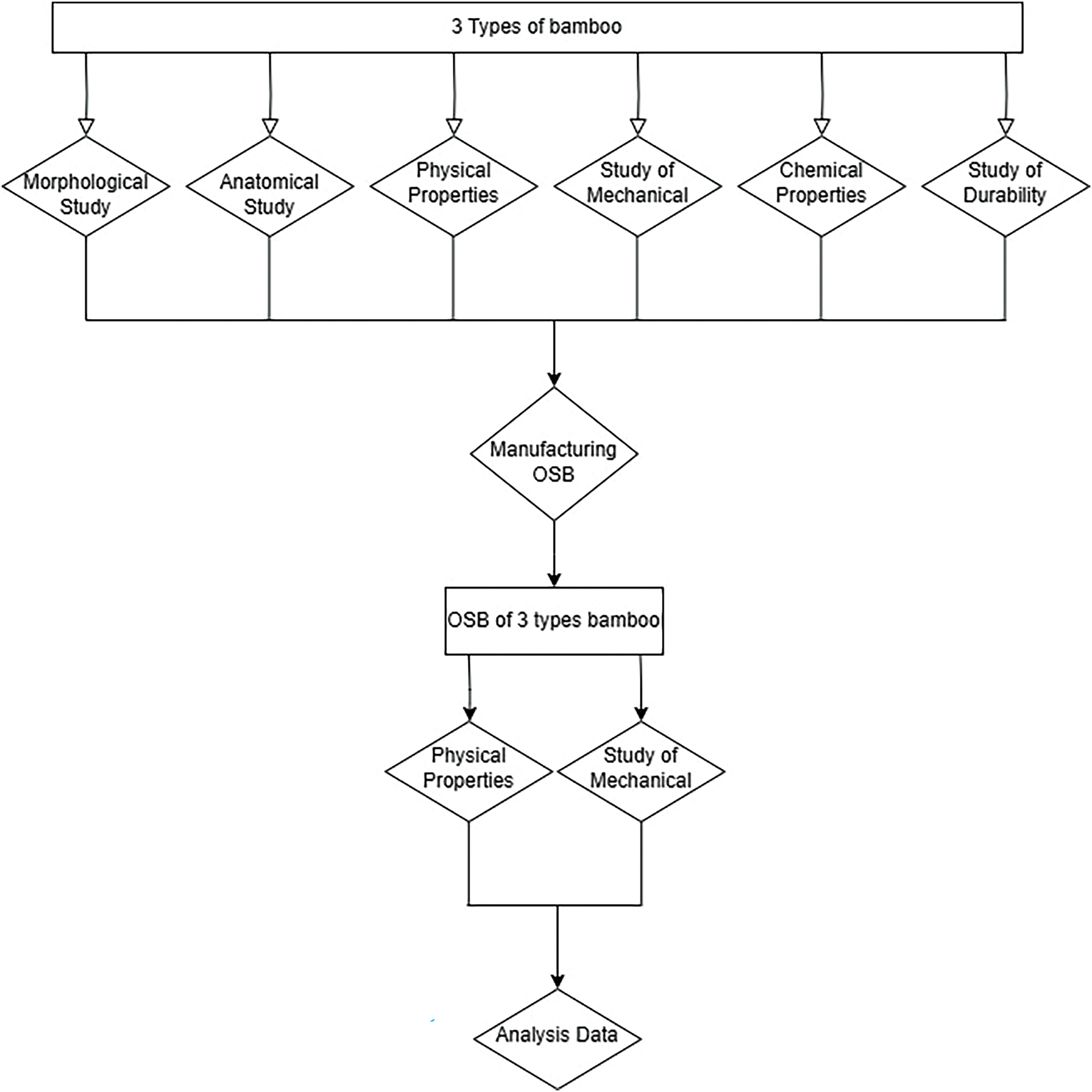

Morphological data analysis was performed using descriptive methods, presented in the form of descriptions and diagrams. For other tests, including physical and mechanical properties, data analysis was conducted using the two-factor Factorial Completely Randomized Design method, with a significance level (p-value) of 5% and a 95% confidence interval. In contrast, anatomical analysis, chemical composition evaluation, starch content measurement, and bamboo durability testing were analyzed using the Non-Factorial Completely Randomized Design method, also applying a p-value of 5% and a 95% confidence interval. The research methodology is visually represented in the flowchart in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The flowchart of this research

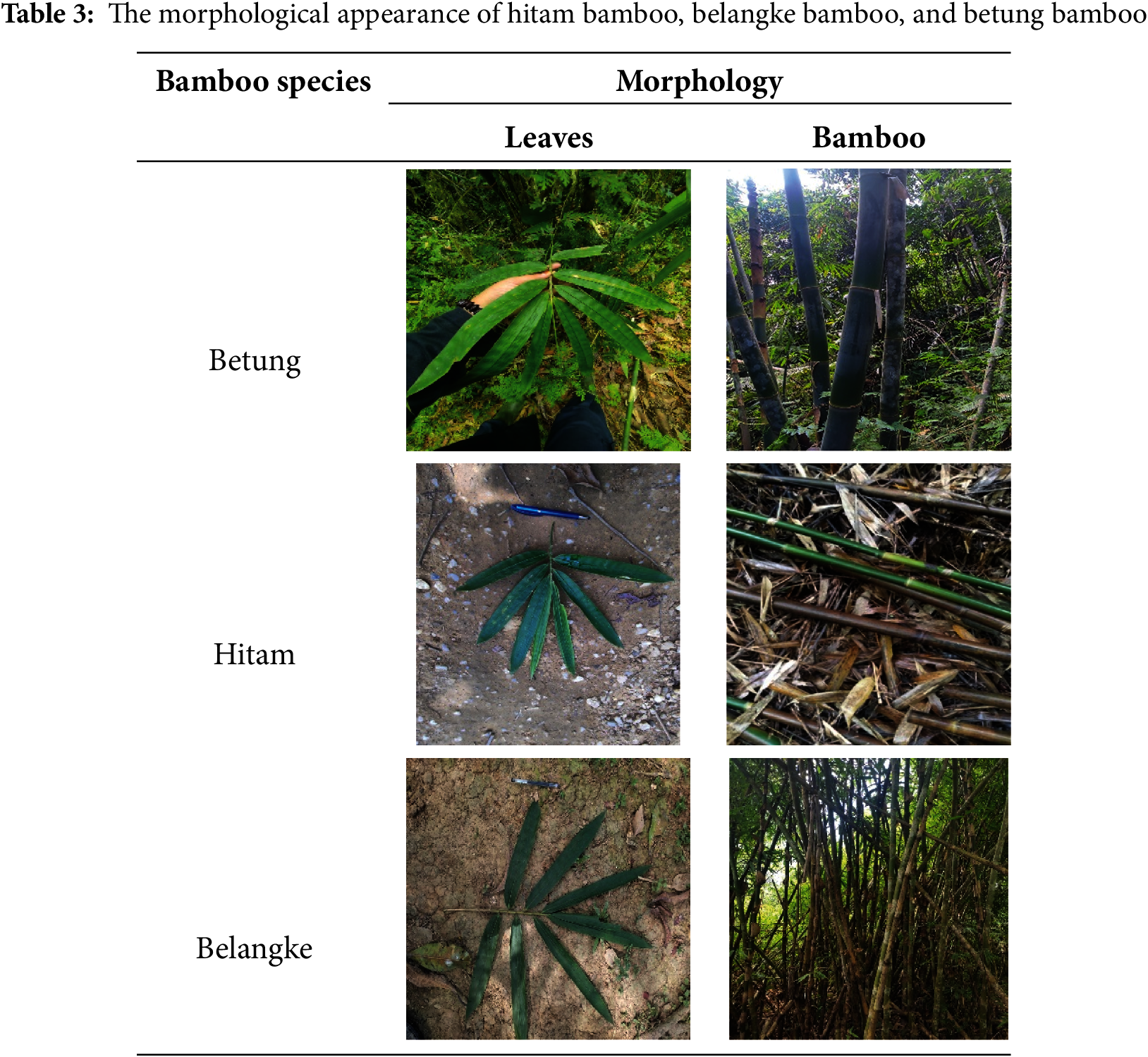

The fundamental characteristics of bamboo were determined through visual assessments, specifically morphological analysis. This evaluation included an examination of bamboo stems, which consist of cavities and segments that vary in length and wall thickness. Based on the identification of bamboo plant samples in the Langkat Region of North Sumatra, three dominant bamboo species were found to exhibit the highest population density in the area: belangke bamboo (Gigantochloa pruriens), hitam bamboo (Gigantochloa atroviolacea), and betung bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper). A comparative summary of the morphological characteristics of these three bamboo species is provided in Table 3.

Morphologically, the three bamboo types share similar characteristics, including the presence of bamboo sheaths, leaf sheaths, sword-shaped leaves, pointed leaf tips, alternate leaf arrangement, smooth leaf margins, and segmented stems. However, hitam bamboo differs in coloration from the other two types, exhibiting black and brown hairs. All three species can reach heights of 15–20 m and exhibit conical shoots, three to four branches, and green leaves with distinctive white stripes.

Betung bamboo is the tallest among the studied species, typically reaching heights of 6–8 m with up to eight branches. According to Hartono et al. [22], betung bamboo possesses a basal stem diameter of 26 cm and can grow as tall as 25 m, classifying it as a large bamboo species [24]. Known for its strong and durable stems, betung bamboo is widely used in construction and building materials. Additionally, its young shoots are valued as traditional culinary ingredients. Hitam bamboo exhibits a distinct morphology, characterized by blackish-green shoots with orange tips and a dense covering of brown-to-black hairs. This species can grow up to 15 m in height and is frequently incorporated into artistic and decorative products due to its unique coloration and aesthetic appeal [12].

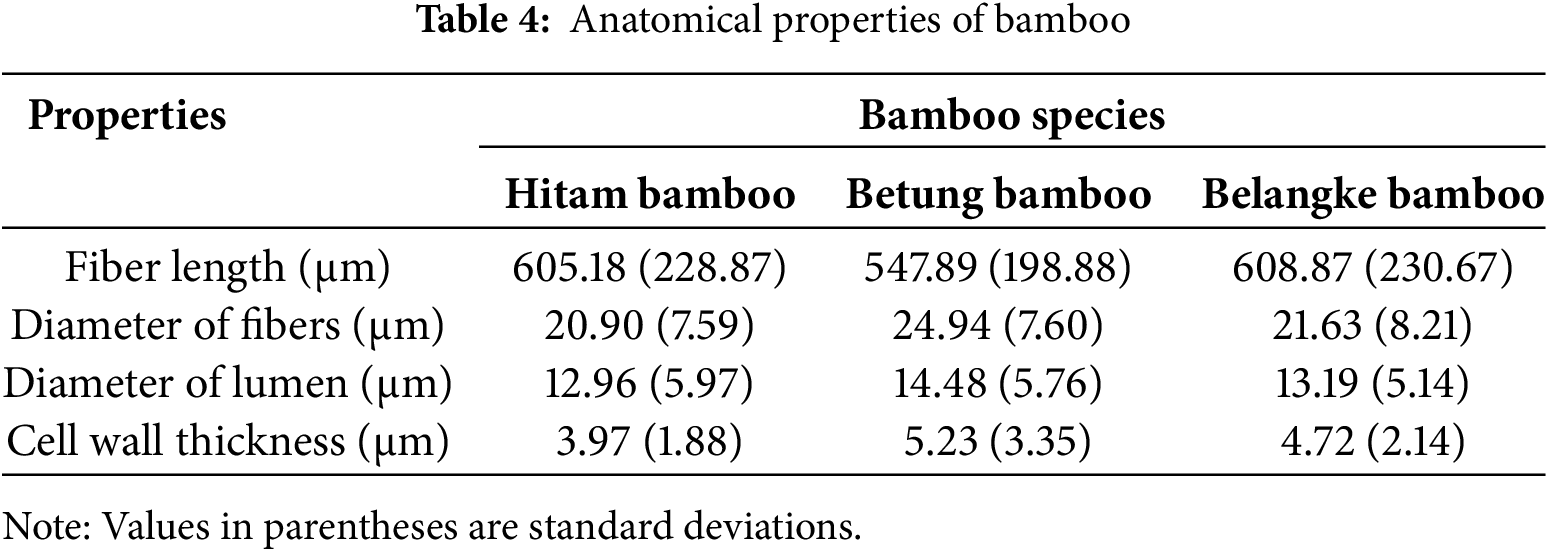

Bamboo fiber length measurements were conducted on three distinct bamboo species: belangke bamboo (Gigantochloa pruriens), hitam bamboo (Gigantochloa atroviolacea), and betung bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper). Fiber length refers to the measurement of a fiber from one end to the other, representing a crucial parameter in evaluating bamboo’s structural and mechanical properties. The average fiber length values for these three bamboo species are summarized in Table 4.

The three studied bamboo species exhibited fiber lengths ranging from 500 to 700 μm. Based on the Indonesian assessment criteria for wood fiber used in pulp and paper production, these bamboo species were categorized as quality class III, characterized by fiber lengths under 1000 μm. Despite this classification, these bamboo fibers possess favorable properties for pulp manufacturing [25]. Fiber length plays a crucial role in determining paper quality, as longer fibers generally enhance tear strength [26]. Statistical analysis revealed that the bamboo species examined did not show significant variation in fiber length, with a confidence interval of 95%.

The fiber diameter of the bamboo samples averaged 22.49 μm, with betung bamboo exhibiting the largest fiber diameter and hitam bamboo the smallest (Table 4). The fiber diameters of the three bamboo species encompass medium and large classifications, contributing to good pulp quality. Fibers with diameters of ≥40 μm are particularly well-suited as raw materials for pulp and paper production, as larger fiber diameters enhance the slenderness ratio, facilitating the formation of high-quality sheets. Slender fibers enable strong inter-fiber bonding, resulting in sheets with superior mechanical strength [27]. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in fiber diameter among the bamboo species, with a confidence interval of 95%.

Betung bamboo exhibited the highest lumen value, with an average diameter of 14.48 μm (Table 4). A larger lumen diameter enhances the suitability of bamboo fibers as raw materials for pulp and paper production. While a wide lumen diameter results in a thinner cell wall, leading to lower tear strength in pulp, it simultaneously improves tensile, bursting, and folding strength [28]. Statistical analysis confirmed significant differences in lumen diameter among the bamboo species, with a confidence interval of 95%. Furthermore, Tukey’s test indicated that belangke bamboo had the most substantial impact on lumen diameter variation.

Cell wall thickness is determined by measuring fiber diameter and dividing the lumen diameter by two. The fiber wall thickness of hitam bamboo and betung bamboo falls within the medium-sized fiber wall thickness category, ranging from 5–15 μm. In contrast, belangke bamboo is classified in the thin fiber wall category, as its thickness measures ≤5 μm (Table 4). Statistical analysis using the non-factorial completely randomized design method revealed no significant differences in anatomical cell wall thickness among the bamboo species.

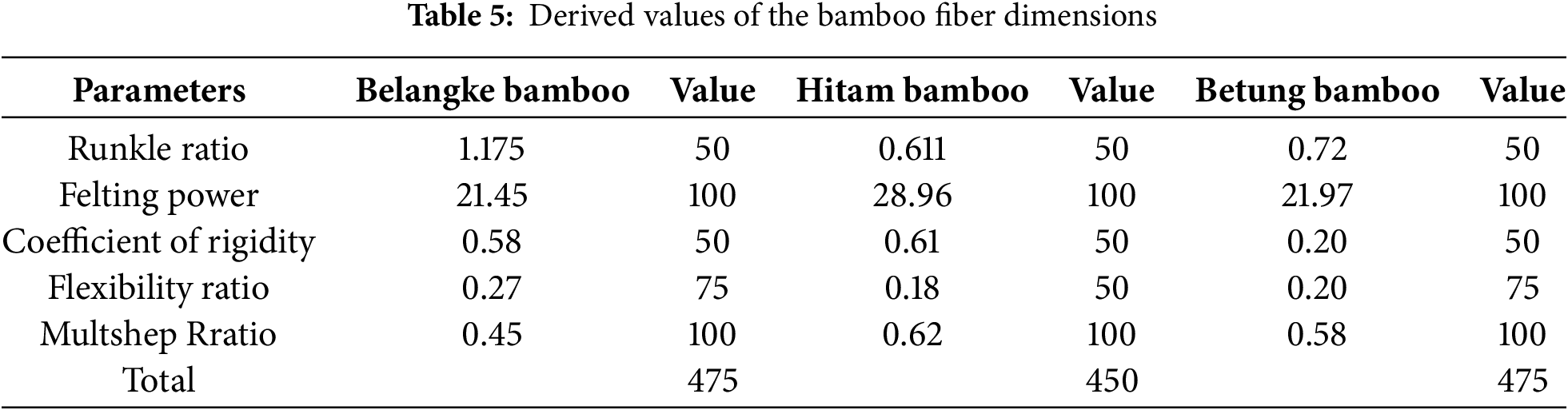

Based on quality class grouping, belangke bamboo and betung bamboo were classified as quality class I, each achieving a value of 475, whereas hitam bamboo was categorized under quality class II, with a total value of 450. Belangke bamboo exhibited the longest fibers among the three species, which enhances fiber bonding during the paper-forming process [29]. Fiber length plays a crucial role in paper strength, pulp washing efficiency, and sheet smoothness [30]. The analysis of fiber dimension derivatives indicates that belangke bamboo possessed the highest runkle ratio value, signifying its thin fiber walls and wide fiber diameter. These characteristics facilitate fiber flattening during sheet formation, leading to a broader contact surface between fibers, thereby improving adhesion and making belangke bamboo an optimal raw material for pulp and paper production in high-quality classifications. However, the other bamboo species, such as hitam bamboo and betung bamboo, also exhibit potential as raw materials for pulp and paper when considering additional fiber dimension parameters [26].

Hitam bamboo had the highest felting power (Table 5), indicating that its fibers are more tightly arranged compared to fibers from other types of bamboo. The felting power value is directly related to the tensile strength of bamboo, as demonstrated in the mechanical property tests, where hitam bamboo exhibited the greatest tensile strength values [31].

The multshep ratio (MR) was the highest in hitam bamboo, whereas betung bamboo exhibited the lowest MR value. Despite the variation, all bamboo species had MR values exceeding 0.15, classifying them within quality class III. MR represents the ratio of fiber wall thickness cross-sectional area to the total fiber cross-sectional area. A lower MR value corresponds to a larger lumen diameter, which facilitates cell flattening and enhances folding capacity. This property contributes to the formation of high-quality pulp sheets with superior flexibility, density, and structural integrity [26]. Belangke bamboo demonstrated the highest flexibility ratio, reflecting its widest lumen diameter and smallest fiber diameter. Consistent with the findings of Sarogoro and Emerhi [32], an elevated flexibility ratio yields paper with superior breaking length strength, improved pliability, and enhanced flattening characteristics, while the pulp maintains high tensile strength. The coefficient of rigidity (CR) value exhibits an inverse relationship with bamboo’s tensile strength. This correlation is substantiated by tensile strength test results across the three bamboo varieties, where betung bamboo demonstrated the highest tensile strength. These findings align with CR test results showing betung bamboo’s lowest CR value of 0.20 [32].

3.3 Physical Properties of Bamboo

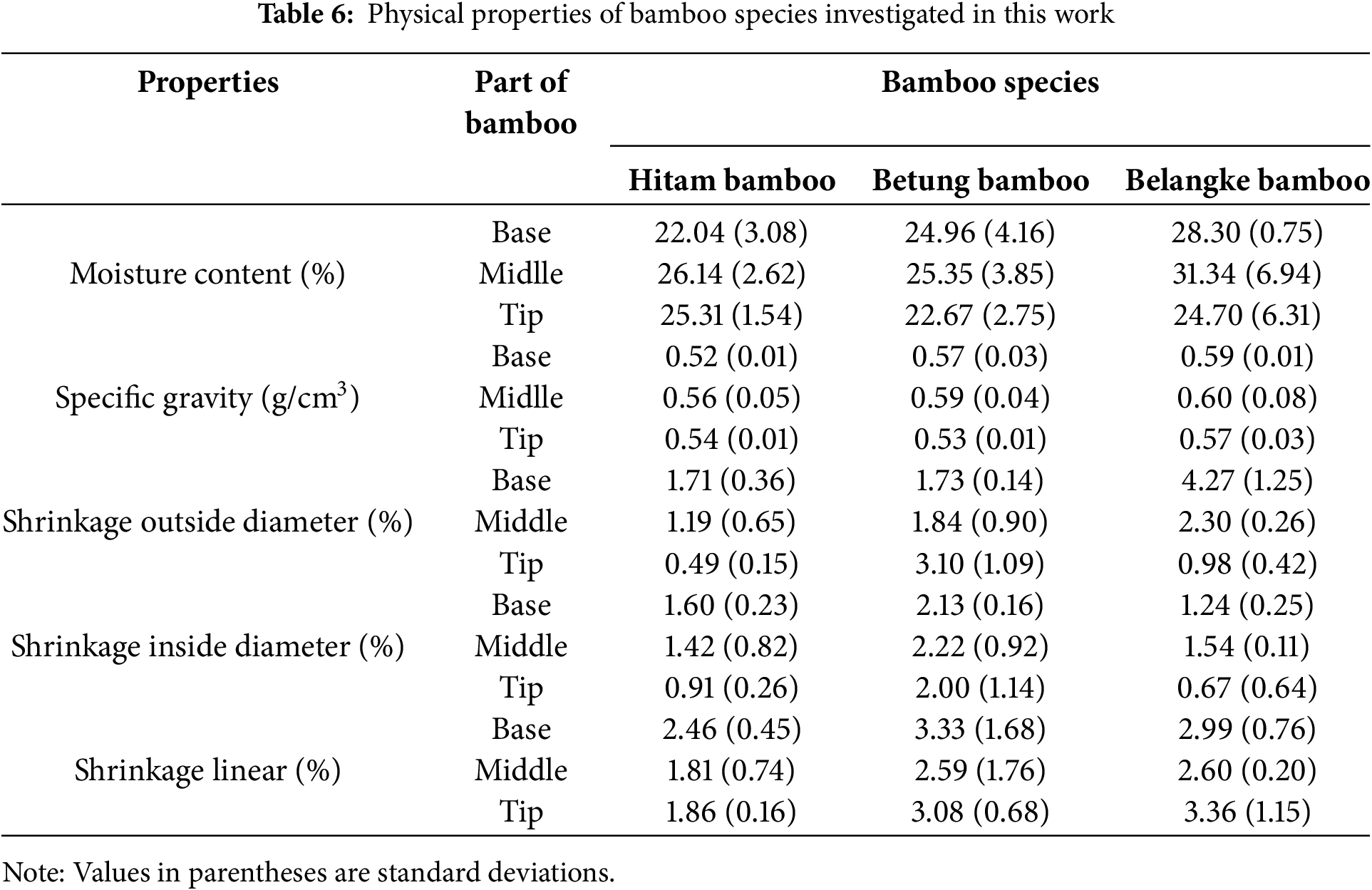

The moisture content of the bamboo samples ranged from 26% to 30% (Table 6), with belangke bamboo exhibiting the highest moisture content and betung bamboo the lowest. These values are consistent with findings from a previous study by [22], which analyzed six bamboo species in North Sumatra and reported an average moisture content of 20% to 25%. Statistical analysis using a two-factor factorial completely randomized design method, with a 95% confidence interval, revealed that neither bamboo species nor bamboo position had a significant effect on moisture content test results.

The specific gravity of the bamboo species ranged from 0.58 to 0.60 (Table 6), with betung bamboo exhibiting the highest specific gravity and hitam bamboo the lowest. This variation was attributed to betung bamboo’s higher concentration of cell wall material per unit volume, which increases its density. A higher specific gravity indicates a greater proportion of cell walls, directly influencing the mechanical strength of the material, particularly the MOR values [22]. These findings are consistent with the results of the cell wall anatomy test, in which betung bamboo demonstrated the highest specific gravity. Statistical analysis, conducted using a two-factor factorial completely randomized design with a 95% confidence interval, revealed that neither bamboo species nor position significantly affected specific gravity test results.

Based on the average shrinkage values, betung bamboo exhibited the highest outer diameter shrinkage, while belangke bamboo showed the lowest shrinkage at the middle section, with values ranging from 5% to 10% (Table 6). Outer diameter shrinkage at the base and middle sections was greater than inner diameter shrinkage and linear shrinkage. This trend is attributed to the vascular bundles—responsible for transport functions—which are more densely distributed on the outer portion of bamboo than on the inner portion [18]. Inner diameter shrinkage ranged from 1.5% to 5%. In hitam bamboo, the highest inner diameter shrinkage was observed at the base, whereas in betung bamboo, it was greatest at the tip. Belangke bamboo exhibited the most significant shrinkage in the middle section compared to the base and tip. Linear shrinkage generally increased from the tip to the base of the bamboo stem. Overall, the highest shrinkage percentage occurred at the tip of the bamboo, while the lowest was observed at the base. This pattern aligns with the increasing proportion of vascular bundles from the base to the tip, which directly influences shrinkage behavior [18]. Analysis of variance confirmed significant differences in inner diameter shrinkage among the three bamboo species at a 95% confidence interval, with variation depending on both stem position (base, middle, and tip) and bamboo type.

Tukey’s test confirmed that both bamboo species and stem position significantly influenced inner diameter shrinkage. Variance analysis of outer diameter shrinkage among the three bamboo species indicated statistically significant differences at the 95% confidence interval. Furthermore, Tukey’s test demonstrated that betung bamboo and belangke bamboo had a significant effect on the reduction of inner diameter. Regarding linear shrinkage, variance analysis revealed statistically significant differences based on both stem position (base, middle, and tip) and bamboo species at the 95% confidence interval. Tukey’s test further identified belangke bamboo as having the most pronounced effect on linear shrinkage.

3.4 Mechanical Properties of Bamboo

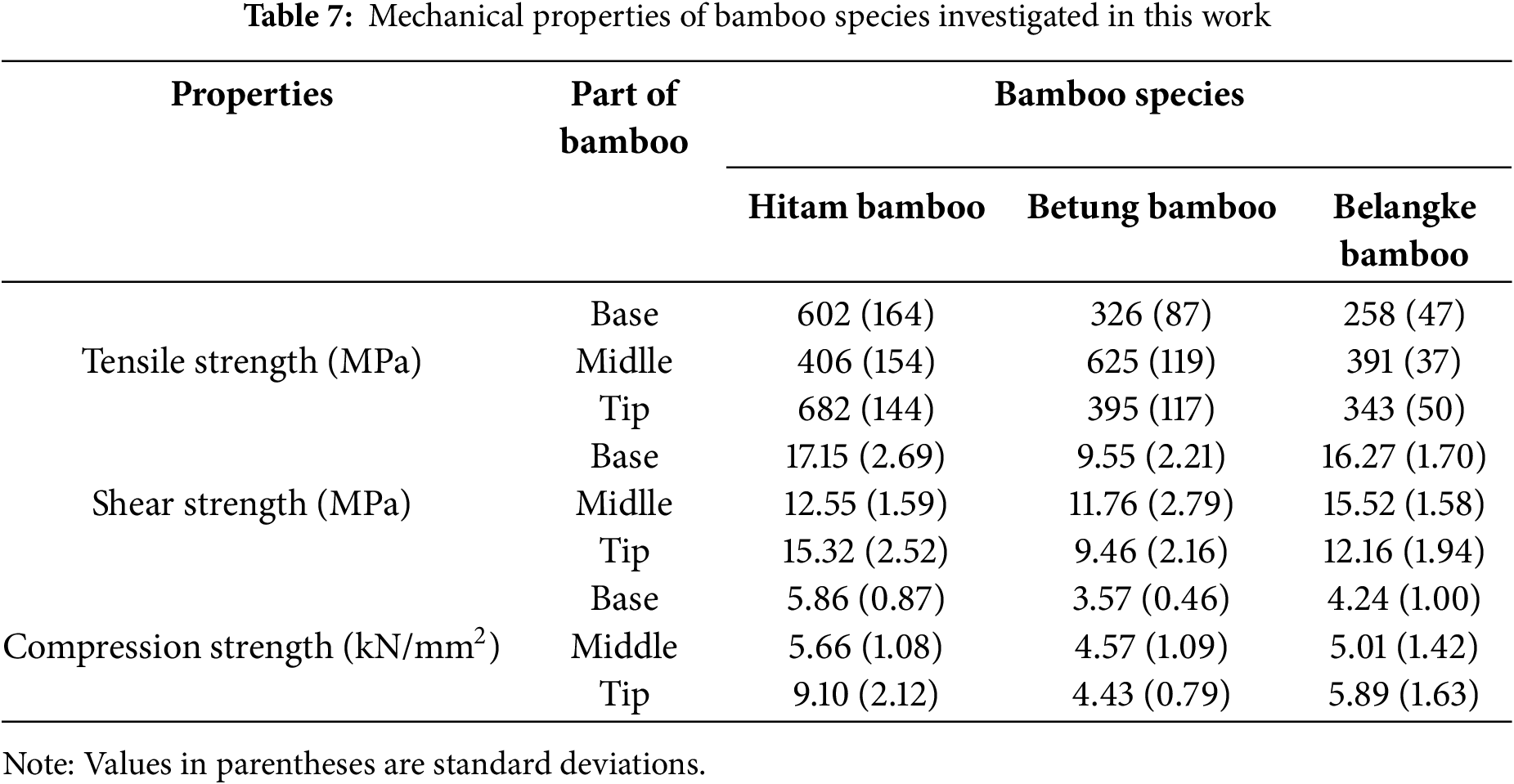

The shear strength values of the three bamboo species varied depending on stem position, ranging from 9.5 to 19 MPa at the base (Table 7). The highest shear strength was recorded in belangke bamboo at the base, whereas betung bamboo exhibited the lowest value. In the middle section, belangke bamboo again demonstrated the highest shear strength at 12.19 MPa, while hitam bamboo recorded the lowest at 9.22 MPa. For the end shear test, hitam bamboo showed the highest shear strength at 15.31 MPa, whereas betung bamboo had the lowest at 7.45 MPa. These variations are primarily attributed to differences in cell wall thickness, cell size, and the number of thick-walled cells, which generally increase from the base to the tip of the bamboo. The tip of the bamboo contains the highest proportion of matrix vessels, which directly affects shear strength. As matrix vessel density increases, shear strength tends to decrease [18]. Additionally, lower shear strength values are associated with reduced lignin content. Mariana et al. [33] reported that lignin plays a crucial role in enhancing the stiffness of secondary walls, reinforcing cohesion between wood tissues, and improving mechanical properties, particularly in the transverse direction. This relationship explains the low shear strength observed in betung bamboo, as it has the lowest lignin content among the studied species [33].

The tensile strength test of the stem positions of three types of bamboo, as shown in Table 7, reveals that hitam bamboo had the highest average value at the base (601.89 MPa) and the lowest at the tip (257.93 MPa). Betung bamboo ranked first in tensile strength at the middle position (624.67 MPa), with the lowest value at the tip (390.71 MPa). Belangke bamboo showed a significant decrease in tensile strength from the base to the tip, with values of 682.28 MPa at the base, 394.77 MPa in the middle, and 343.14 MPa at the tip. Variations in the tensile strength of bamboo are influenced by differences in moisture content from the base, middle, and tip of the bamboo. Amiruddin et al. [34] reported that tensile strength increases as bamboo moisture content rises. This relationship is reflected in the physical properties of hitam bamboo, which exhibits the highest moisture content, with values progressively increasing from the base to the tip. According to Maulana et al. [18], fiber length affects the mechanical properties of tensile strength, and bamboo with longer fibers has the highest tensile strength value. This is in accordance with the research on fiber length shown in Table 4, which revealed that the hitam bamboo type had the longest fibers and has the greatest tensile strength. In addition to differences in anatomical structure, the chemical components of bamboo can also cause these differences. Lignin and α-cellulose contents have a significant effect on the mechanical properties of bamboo [8]. Lignin plays a crucial role in contributing to stiffness properties, while cellulose, characterized by its linear polymer structure and high crystalline fraction, influences the overall mechanical integrity of bamboo fibers. The results indicated that hitam bamboo exhibited the highest average lignin and α-cellulose contents among the studied bamboo species, suggesting its strong structural potential for various applications.

The compressive strength values of all three bamboo species decreased progressively from the base to the tip, with the tip exhibiting the lowest compressive strength. Hitam bamboo demonstrated the highest compressive strength at the tip (9.77 kN/mm2) and the lowest in the middle (3.24 kN/mm2) (Table 7). According to Hartono et al. [22], mechanical strength variation at different stem positions is primarily attributed to differences in moisture content. Additionally, compressive strength is influenced by the proportion of outer skin in the cross-section. The base of the bamboo displays the highest compressive strength, likely due to variations in fiber length and wall thickness [31]. Hartono et al. [22] also reported a negative correlation between compressive strength and fiber diameter. Betung bamboo, which has the largest fiber diameter among the studied species, exhibited lower compressive strength as a result [24].

The analysis of variance of the compression test conducted on the three bamboo species revealed statistically significant differences in compressive strength based on both stem position (base, middle, and tip) and bamboo species, with a confidence interval of 95%. Tukey’s test further identified betung bamboo as having the most pronounced effect on compressive strength, with the base and tip positions exerting the most significant influence on strength values. Conversely, variance analysis of shear and tensile strength assessments indicated no statistically significant differences at a 95% confidence interval based on either stem position or bamboo species.

3.5 Chemical and Durability Properties of Bamboo

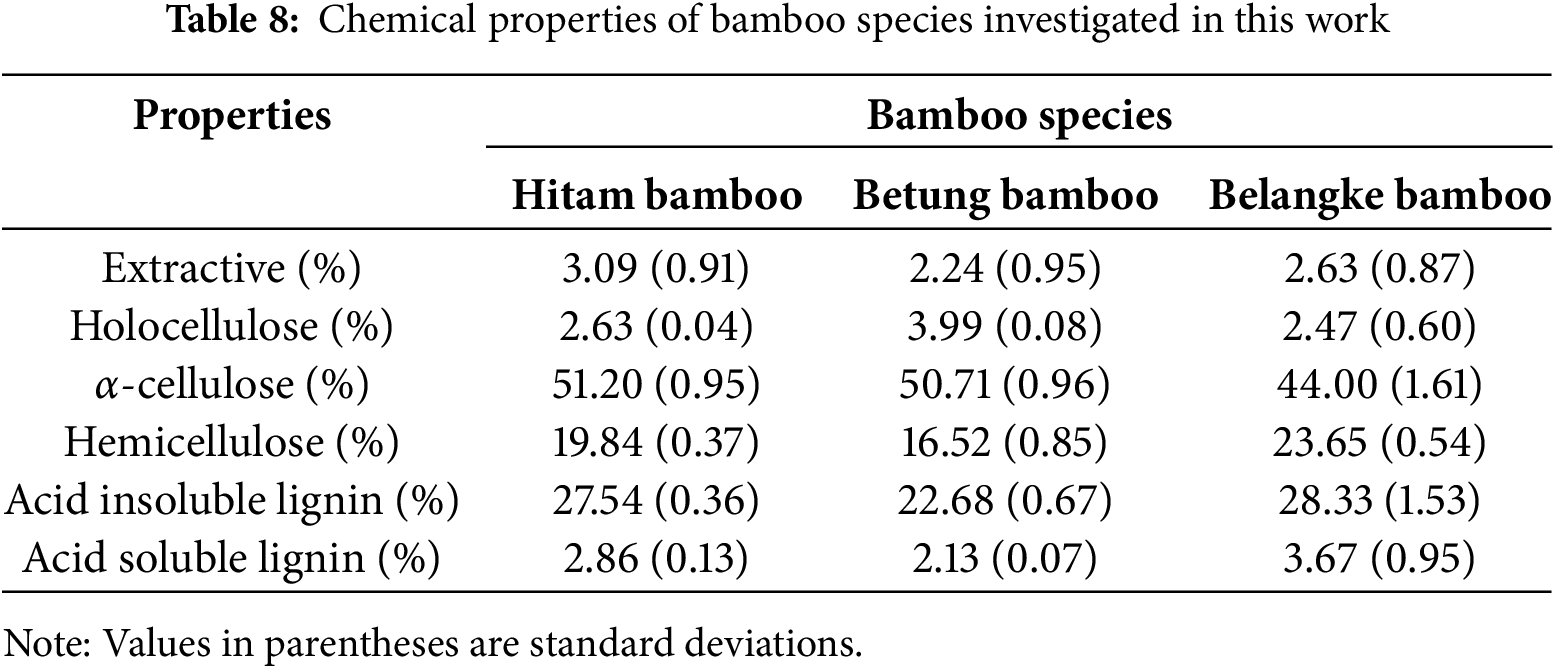

The highest extractive content was observed in hitam bamboo at 2.93%, followed by betung bamboo at 2.37%, while belangke bamboo exhibited the lowest value at 2.1% (Table 8). These findings align with Rusch et al. [35], who reported that extractive content in bamboo typically ranges from 3% to 8%. Similarly, Gu et al. [36] noted that bamboo extractives generally fall within a 3% to 5% range. The relatively low extractive content (<5%) in the studied bamboo species may be attributed to their smaller pore structures, limiting the accumulation of extractive substances. Higher extractive content results from the deposition of photosynthesis-derived glucose. Extractive content plays a crucial role in durability, particularly in determining resistance to biological threats. While bamboo extracts are typically nontoxic, all bamboo species require preservation due to their heightened susceptibility to powder beetles, fungi, and termites compared to wood [29]. The physical, mechanical, and chemical properties of bamboo vary depending on extractive content [22]. Bamboo extractives primarily consist of resin, lipids, wax, tannins, pentosan, hexosan, starch, and silica. Extractive content dissolved in ethanol-benzene solutions has been reported to range from 1.93% to 7.95%. Variance analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in extractive content among the three bamboo species at a 95% confidence interval.

Hitam bamboo exhibited the lowest ash content at 2.45%, followed by belangke bamboo at 3.08%, while betung bamboo recorded the highest value at 4.22% (Table 8). These findings indicate that betung bamboo contains a higher inorganic residue following the combustion of organic material. Lower ash content is generally preferable, as it signifies a reduced presence of mineral components. Variance analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in ash content among the three bamboo species at a 95% confidence interval.

Table 8 presents the average lignin content of the three bamboo species, showing that hitam bamboo exhibited the highest acid-insoluble lignin (AIL) content at 27.54%, followed by belangke bamboo at 26.3%, while betung bamboo recorded the lowest value at 22.7%. These findings align with those of [22], which reported that lignin content in six bamboo species from North Sumatra ranges between 22.12% and 36.61%. Regarding acid-soluble lignin (ASL), belangke bamboo demonstrated the highest content at 3.48%, followed by hitam bamboo at 2.86%, and betung bamboo at 2.12%. These results are consistent with the findings of Darwis and Iswanto [37], who examined the chemical properties of 10 bamboo species in North Sumatra and reported an average ASL content ranging from 3% to 5% [37]. Variance analysis confirmed statistically significant differences in AIL content among the three bamboo species at a 95% confidence interval, with Tukey’s test indicating that betung bamboo had the most pronounced influence. Conversely, variance analysis of ASL content revealed no statistically significant differences among the bamboo species at the same confidence level.

Holocellulose, a fiber devoid of extractives and lignin, typically exhibits a white to yellowish coloration and constitutes the total carbohydrate or polysaccharide content of the raw material [38]. According to the average holocellulose content values presented in Table 8, the studied bamboo species exhibited holocellulose concentrations ranging from 63% to 68%. Betung bamboo displayed the highest holocellulose content at 68.69%, followed by belangke bamboo at 65.12%, while hitam bamboo recorded the lowest value at 64.18%. The analysis of variance confirmed statistically significant differences in holocellulose content among the three bamboo species at a 95% confidence interval. Additionally, Tukey’s test identified betung bamboo as having the most pronounced influence on holocellulose concentration.

Table 8 presents the average α-cellulose content across the three bamboo species, with hitam bamboo exhibiting the highest value at 53.04%, followed by belangke bamboo at 48.16%, and betung bamboo at 41.79%. These findings align with those of [22], which reported α-cellulose content in six bamboo species from North Sumatra ranging between 40% and 55%. Cellulose content in bamboo stems varies due to environmental factors that influence fiber characteristics, including type, quantity, size, shape, physical structure, and chemical composition. This variability is supported by Rusch et al. [35], who highlighted the impact of growing conditions on cellulose accumulation [35]. The analysis of variance analysis confirmed statistically significant differences in α-cellulose content among the three bamboo species at a 95% confidence interval. Additionally, Tukey’s test identified belangke bamboo as having the most pronounced effect on α-cellulose variation.

Hemicellulose is an amorphous polymer closely associated with cellulose and lignin, forming an integral component of plant cell walls. Unlike cellulose, which has a crystalline structure, hemicellulose consists of a heterogeneous group of polysaccharides with branched chains, contributing to its flexibility and solubility. It plays a crucial role in strengthening the plant’s structure while maintaining its ability to retain moisture. Due to its structural properties, hemicellulose establishes a stronger bond with lignin than with cellulose, forming a network that enhances the mechanical integrity of bamboo fibers while also enabling efficient water retention [38]. The average hemicellulose content among the three bamboo species ranged from 17.47% to 23.64% (Table 8). Betung bamboo exhibited the lowest hemicellulose content at 17.47%, while belangke bamboo recorded the highest at 23.64%, which corresponds with its previously noted high moisture content. The analysis of variance analysis confirmed statistically significant differences in hemicellulose content among the three bamboo species at a 95% confidence interval. Tukey’s test further identified belangke bamboo as having the most pronounced influence on hemicellulose variation.

Starch is a carbohydrate stored within the pore cells of bamboo, filling cavities and playing a crucial role in the plant’s physiological processes [29]. The starch content directly influences bamboo’s natural resistance to subterranean termite attacks; lower starch concentrations improve termite resistance, while higher starch levels make bamboo more susceptible to infestations. The analysis of starch content using the in-house method revealed that betung bamboo exhibited the highest starch concentration at 7.08%, whereas belangke bamboo recorded the lowest value at 3.13%. These findings underscore the impact of starch accumulation on bamboo durability and susceptibility to biological degradation.

The weight loss of the three bamboo species following subterranean termite attacks ranged from 0.2% to 2.08%. The extent of weight reduction varied among species, with betung bamboo exhibiting both the lowest and highest recorded weight loss. According to SNI 7207-2014 [23], which establishes wood resistance standards—including bamboo—all three species can be classified as highly resistant to termite attack, as their weight loss remained below the 3.5% threshold. Bamboo’s natural durability is primarily influenced by its starch content, as starch serves as a key nutrient for subterranean termites. Starch content analysis revealed that betung bamboo had the highest starch concentration (7.08%), which directly corresponded with its highest recorded weight loss of approximately 2%. Conversely, belangke bamboo, with the lowest starch content, exhibited minimal weight reduction in the natural resistance test. This finding aligns with research by Felisberto et al. [39], which established a strong correlation between starch concentration and bamboo durability.

Lignin is a structural component in bamboo that subterranean termites find unpalatable, as they primarily digest cellulose while leaving lignin largely intact. Consequently, bamboo species with higher lignin content tend to exhibit greater resistance to termite attacks. Belangke bamboo demonstrated a high lignin content of 26.3%, whereas betung bamboo had a lower lignin concentration of 22.7%. This trend correlates with termite-induced weight loss, with belangke bamboo exhibiting the lowest percentage of weight reduction and betung bamboo experiencing the highest susceptibility to termite infestation. The analysis of variance analysis of resistance test results revealed statistically significant differences in termite susceptibility among the three bamboo species at a 95% confidence interval. Furthermore, Tukey’s test identified hitam bamboo and betung bamboo as having the most pronounced effects on resistance variability.

3.6 Physical Properties of OSB

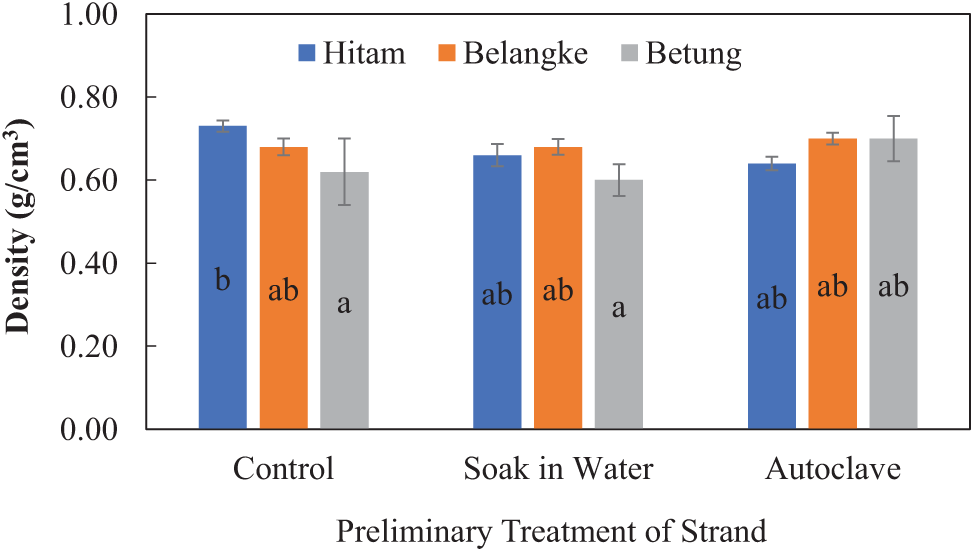

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the density of the oriented strand board (OSB) varied between 0.60 and 0.73 g/cm3 across the research samples. The hitam bamboo board subjected to the control treatment (board code G) exhibited the highest density, whereas the betung bamboo board undergoing the soaking treatment (board code C) demonstrated the lowest density. The data suggest that untreated (control) boards maintained the highest density, likely due to the absence of extractive substance solubility caused by soaking. The soaking process reduces density by increasing the dissolution of extractives, thereby altering the physical properties of the board. Additionally, Pędzik et al. [40] identified other contributing factors to the lower density of treated boards, including the effects of spring-back—the tendency of the board to revert to its original shape—and the loss of raw material particles during the manufacturing process. These variables further influence density and structural integrity in OSB production [40].

Figure 5: Density value of the OSB boards. Letters a, b, and ab indicate significant differences in statistical analysis

This study produced boards classified as medium-density boards, as their density values fell within the range defined by Nourbakhsh et al. [41], who specify medium-density boards as having a density between 0.59 and 0.80 g/cm3. Furthermore, according to the JIS A 5908 (2003) standard [20], board density should range from 0.4 to 0.9 g/cm3, meaning that the values obtained in this study conform to established industry standards. The board density is influenced by various factors, including the type of wood used and the level of compressive force applied during board sheet production. These variables play a crucial role in determining the final density and structural properties of the boards [42].

The results of the density variance analysis test revealed that the interaction between treatment and bamboo type had a significant effect on the density value, with a 95% confidence interval. This is further supported by the findings of the Duncan multiple range test (DMRT), confirming the interaction of the two influencing factors. The data revealed that there was no significant difference between the betung-soaked board and the control betung board, black autoclave, or black-soaked board. Moreover, the betung control board was significantly different from all OSB boards. The properties and characteristics of particleboard are strongly influenced by its density [43]. Overall, the resulting density values meet the Japanese Industrial Standard (2003) [20], which specifies a density range of 0.4–0.9 g/cm3.

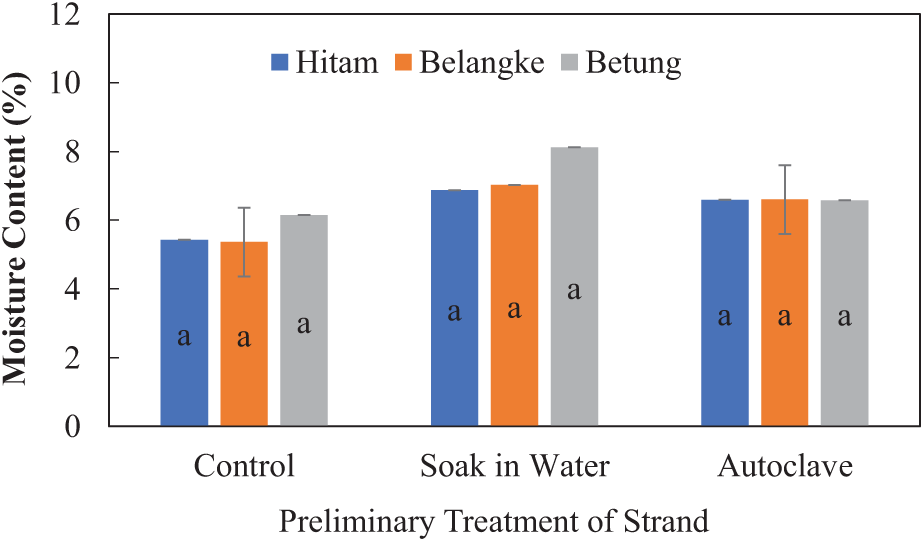

Fig. 6 illustrates that the moisture content of the oriented strand board (OSB) ranged from 5.36% to 8.12%. The betung bamboo board subjected to the soaking treatment (board code C) exhibited the highest moisture content, whereas the belangke bamboo control board (board code H), which did not undergo soaking, recorded the lowest moisture content. The data indicate that the moisture content of the betung bamboo OSB increased following soaking, surpassing that of the other boards. The initial strand treatment, which involved soaking in cold water for 24 h followed by autoclaving, aimed to reduce extractive substances within the bamboo strands, potentially influencing the board’s moisture retention characteristics.

Figure 6: Moisture content of the OSB boards. The same letter a indicates no significant difference in statistical analysis

Findings from this study indicate that soaking bamboo strands in water as a pretreatment increases board moisture content compared to untreated boards. Moisture content is closely linked to density, with higher-density boards exhibiting lower moisture levels. However, excessive moisture may weaken adhesive bonding, compromising the structural integrity of the board. Tolessa et al. [44] reported that the presence of extractive substances negatively affects water resistance, as these compounds interfere with moisture stability in particleboard. A high concentration of extractives can impair water resistance properties, reducing the board’s ability to maintain a stable moisture content. Presoaking bamboo strands is an effective strategy for minimizing extractive substances, thereby enhancing water resistance and improving the overall durability of the final product [45].

The analysis of variance revealed that the interaction between bamboo type and initial treatment did not have a statistically significant impact on board moisture content at a 95% confidence interval. However, both the treatment factor and bamboo type factor independently exhibited significant differences in moisture content at the same confidence level. Duncan’s Multiple Range Test further demonstrated that the control board of belangke bamboo was not significantly different from the control boards of hitam bamboo or betung bamboo. Additionally, the moisture performance of the betung autoclave-treated board showed no significant difference from that of the hitam autoclave-treated board, belangke autoclave-treated board, hitam soaking-treated board, or belangke soaking-treated board. However, the betung bamboo soaking-treated board displayed a statistically significant difference compared to all other oriented strand board (OSB) types. Overall, the moisture content values obtained in this study were within the acceptable range of 5% to 13%, as specified by the JIS A 5908-2003 standard [20], ensuring satisfactory compliance with industry guidelines.

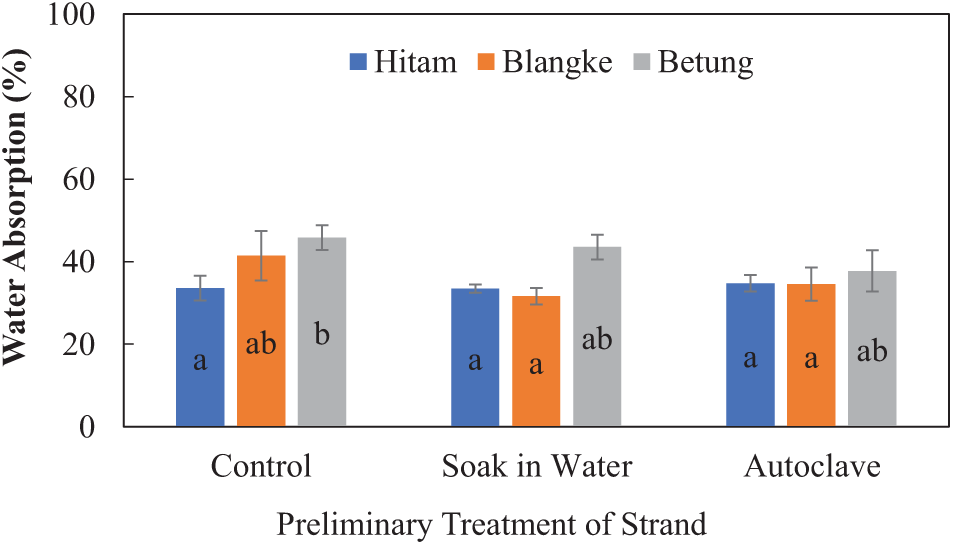

Fig. 7 illustrates that the water absorption values of the oriented strand board (OSB) ranged from 31.60% to 45.82%. The control-treated betung bamboo board (board code I) exhibited the highest water absorption value, whereas the soaking-treated betung bamboo board (board code B) recorded the lowest. Additionally, Fig. 7 shows that the belangke bamboo soaking-treated board demonstrated lower water absorption compared to the other boards. Karlinasari et al. [12] reported an inverse relationship between water absorption and bulk density (BD), indicating that variations in BD directly influence moisture retention properties [12].

Figure 7: Water absorption value of the OSB boards. Letters a, b, and ab indicate significant differences in statistical analysis

According to research conducted by Karlinasari et al. [12], the water absorption value of oriented strand board (OSB) increases along the low face layer due to the structural composition of betung bamboo. Unlike other bamboo species, betung bamboo possesses two fiber bundle layers, whereas belangke and hitam bamboo contain only a single fiber bundle layer. Additionally, betung bamboo has demonstrated superior dimensional stability compared to other bamboo species, making it more resistant to water absorption. This increased stability is attributed to its unique anatomical composition, which influences the board’s moisture retention properties. Based on this explanation, increasing the surface layer of OSB bamboo enhances its dimensional stability, reducing susceptibility to moisture-related expansion and deformation.

Boards with lower density tend to exhibit higher water absorption due to increased porosity compared to high-density boards. The greater pore volume in low-density boards allows for enhanced water penetration, leading to higher moisture retention. The water absorption process is directly proportional to soaking duration, meaning that prolonged exposure results in a greater influx of water filling the board’s cavities [46]. Among the bamboo species tested, untreated betung bamboo exhibited the highest moisture content, which contributed to weakened adhesive strength. Gao et al. [31] further established that board density significantly influences water absorption capacity, underscoring the importance of density control in optimizing board durability and adhesive performance [47].

The analysis of variance revealed that the interaction between initial treatment and bamboo species had a statistically significant effect on water absorption at a 95% confidence interval. Furthermore, Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) indicated that the water absorption performance of the belangke bamboo soaking-treated board was not significantly different from that of the hitam bamboo soaking-treated board, the hitam bamboo control board, the belangke bamboo autoclave-treated board, or the hitam bamboo autoclave-treated board. However, significant differences were observed when compared to the belangke bamboo control board, the betung bamboo soaking-treated board, and the betung bamboo control board. Additionally, the betung bamboo control board exhibited statistically significant differences from all other board types. While the JIS A 5908 [20]standard does not specify a benchmark for water absorption values, this test serves as an essential evaluation of the composite board’s resistance to water exposure. Its results are particularly relevant for exterior applications or conditions frequently affected by environmental moisture, including humidity and precipitation.

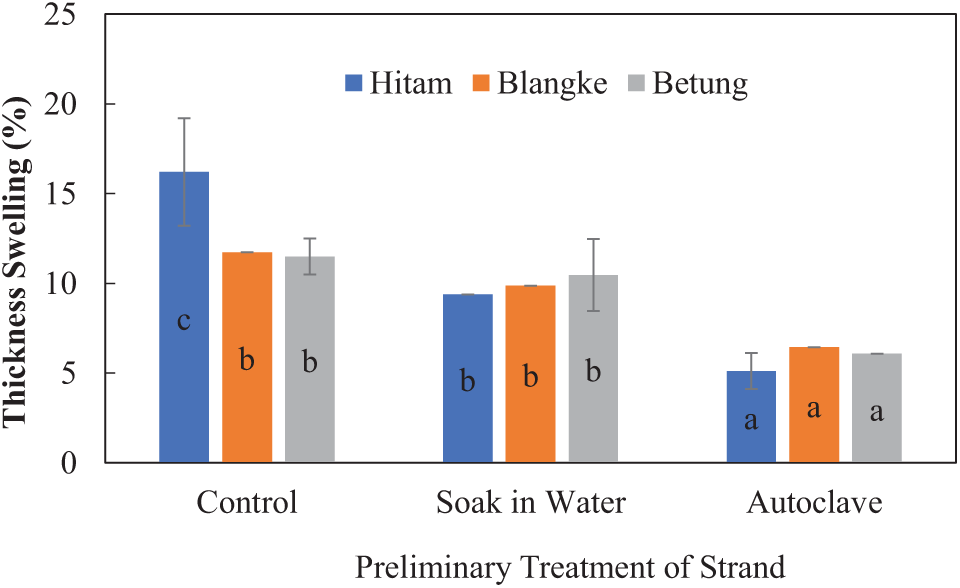

Fig. 8 illustrates that the thickness swelling values of the oriented strand board (OSB) ranged from 5.11% to 16.27%. The hitam bamboo board subjected to autoclave treatment (board code D) exhibited the lowest thickness swelling, whereas the control-treated hitam bamboo board displayed the highest swelling value. The reduced thickness swelling in the autoclaved hitam bamboo board is attributed to the autoclave process, which induces swelling in the vessel cells. This treatment facilitates the reduction of extractive substances within the strand, subsequently enhancing adhesive absorption and integration into the fiber structure. Yousefi et al. [48] established a strong correlation between thickness swelling and water absorption, noting that increased water intake within the fiber network leads to more pronounced dimensional expansion. These findings underscore the impact of moisture retention on the structural integrity and stability of OSB boards.

Figure 8: Thickness swelling of the OSB boards. Letters a, b, and c indicate significant differences in statistical analysis

The analysis of variance conducted on thickness development revealed a statistically significant interaction between initial treatment and bamboo species, with a confidence interval of 95%. Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) further indicated that the hitam bamboo autoclave-treated board was not significantly different from the betung bamboo autoclave-treated board or the belangke bamboo autoclave-treated board. Additionally, the soaked hitam bamboo board exhibited no significant differences compared to the soaked belangke bamboo board, soaked betung bamboo board, betung control board, or belangke control board. Extractive substances dissolved in cold water are believed to remain adhered to the surface of the strands [49]. This residual presence may inhibit adhesive bonding during OSB fabrication, leading to increased thickness development. Among all tested boards, only the hitam bamboo control board exhibited a thickness swelling value that did not meet the industry standards. However, the remaining boards demonstrated compliance with established thresholds, including the JIS A 5908:2003 standard [20] (maximum allowable swelling of 12%) and the CSA 0.437.0:2011 standard (maximum allowable swelling of 15%).

3.7 Mechanical Properties of OSB

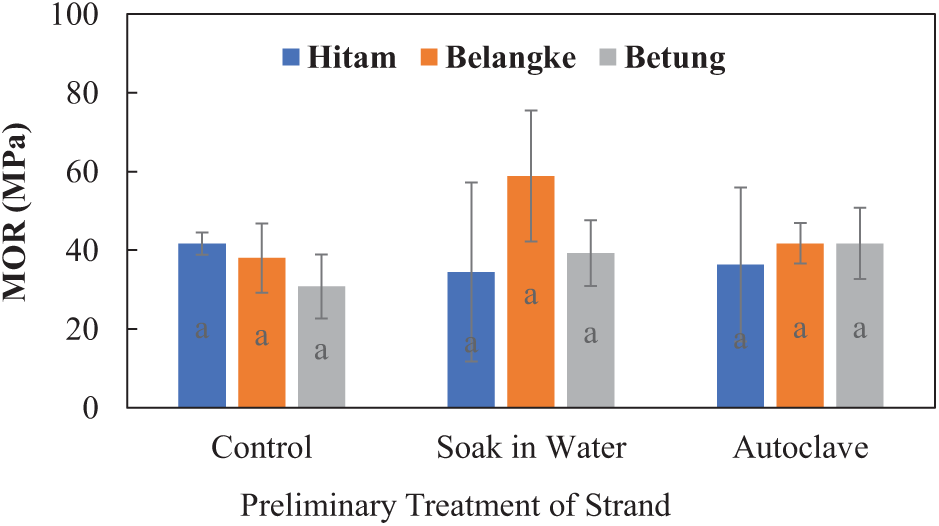

Fig. 9 illustrates that the modulus of rupture (MOR) values of the oriented strand board (OSB) ranged from 30.79 to 58.84 MPa. The highest MOR value was observed in the hitam bamboo board subjected to soaking treatment (board code A), whereas the lowest MOR value was recorded in the untreated (control) betung bamboo board (board code I). A similar trend was identified in the modulus of elasticity (MOE) values, demonstrating a consistent relationship between soaking treatment and mechanical performance. Strayhorn et al. [50] reported that MOR values tend to increase following soaking treatment, as extractive substances dissolve in water, thereby enhancing adhesive bonding and improving overall structural integrity. Previous studies presented MOR values for OSB ranging from 24.81 to 45.11 MPa, which, while lower than the average MOR findings in this study, further support the positive impact of soaking on mechanical properties.

Figure 9: Modulus of rupture of the OSB boards. The same letter a indicates no significant difference in statistical analysis

The analysis of variance revealed that the interaction between initial treatment and bamboo species did not have a statistically significant effect on the modulus of rupture (MOR) of the board at a 95% confidence interval. Bamboo contains silica in the form of robust fibers, which contribute to its exceptional strength and resistance. Silica is concentrated within the cell tissue, particularly in the cell walls, enhancing the plant’s structural integrity, pressure resistance, and flexibility—key attributes that allow bamboo to grow tall and withstand environmental stresses. As bamboo matures, it absorbs silica from its surroundings and incorporates it into its cellular structure, reinforcing its mechanical properties. The MOR is influenced by multiple factors, including adhesive type, adhesive adhesion quality, and particle size [51]. As a mechanical property, MOR reflects the board’s ability to endure loading conditions until reaching its maximum breaking point [52]. Results from this study confirmed that the measured MOR values were satisfactory and complied with official standards, specifically exceeding the minimum requirement of 7.85 MPa outlined in the JIS A 5908-2003 and CSA 0.437.0-2011 standards.

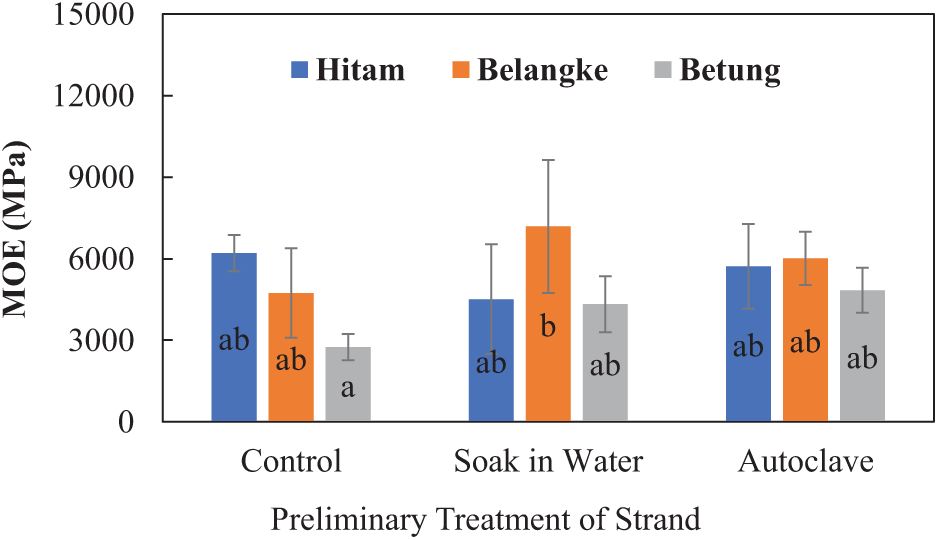

Fig. 10 illustrates that the MOE values of the oriented strand board (OSB) ranged from 2745 MPa to 7183 MPa. The highest MOE value was recorded in the belangke bamboo board subjected to immersion treatment (board code B), while the lowest MOE value was observed in the control-treated betung bamboo board (board code I). A similar trend was observed for the modulus of rupture (MOR) values, reinforcing the relationship between initial treatment and mechanical performance. Strayhorn et al. [50] reported that soaking bamboo strands in water enhances the flexural stiffness of the board by improving fiber integration and adhesive bonding. In alignment with these findings, the present study confirmed that the strand board pretreated with belangke bamboo exhibited the highest flexural stiffness, further supporting the positive effects of soaking treatment [50].

Figure 10: Modulus of elasticity of the OSB boards. Letters a, b, and ab indicate significant differences in statistical analysis

The analysis results indicated that the interaction between initial treatment and bamboo species did not have a statistically significant effect on the modulus of elasticity (MOE) at a 95% confidence interval. However, the bamboo species factor alone exhibited statistically significant differences in MOE at the same confidence level. Subsequent Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) analysis revealed that the belangke bamboo soaking-treated board demonstrated significant differences compared to both the betung bamboo soaking-treated board and the betung control board. These findings contrast with those of Li et al. [53], whose research reported lower average MOE values for their OSB samples compared to the results obtained in this study [53].

Analysis of several bamboo species revealed minimal elemental content, making it challenging to identify significant variations relative to carbonization temperature [54]. Among the tested varieties, betung bamboo and belangke bamboo exhibited higher magnesium and calcium concentrations compared to other species, with betung bamboo demonstrating the highest silica content. Previous research has shown that specific treatments can enhance the silica concentration in bamboo. Solution-based treatments increase silica availability through direct incorporation, whereas thermal processing liberates bound silica from the plant matrix. However, treatment-induced silica variation is influenced by multiple factors, including (1) treatment methodology, (2) environmental conditions, and (3) bamboo species characteristics. Consequently, while certain treatments can elevate silica levels, the extent of their impact varies significantly depending on these interacting factors.

According to Fauziyyah et al. [55], the MOE value is influenced by multiple factors, including adhesive composition, adhesive type, bond strength, and particle size. Additionally, the use of isocyanate adhesives has been identified as a key determinant in MOE performance [55]. Isocyanate adhesives offer several advantages over conventional adhesives, including high reactivity, strong adhesion properties, and long-lasting durability. These characteristics contribute to the development of products with superior physical and mechanical properties [56]. The findings of this study confirmed that the measured MOE values met the official requirements set forth by the JIS A 5908 standard [20], which stipulates a minimum MOE of ≥2000.5566 MPa. Furthermore, the results also satisfied the CSA 0.437.0 standard, which requires a minimum MOE threshold of 1274.8645 MPa, demonstrating compliance with established industry benchmarks.

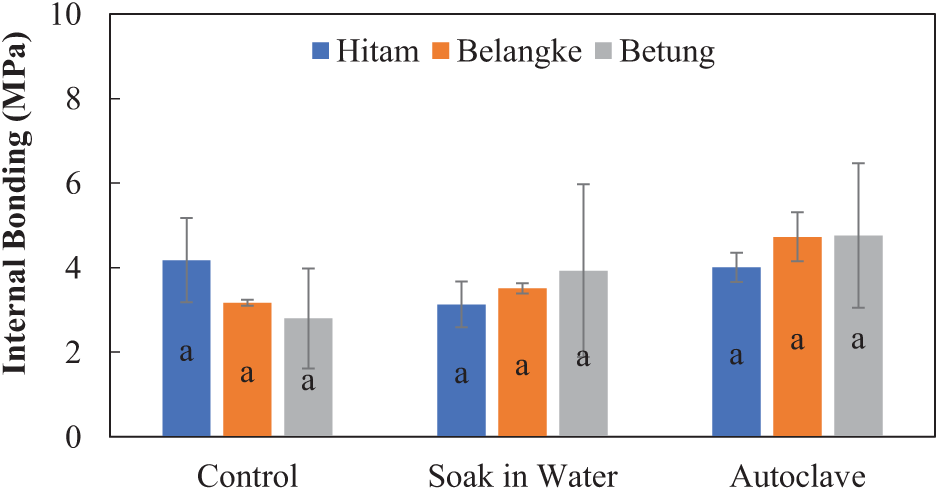

Fig. 11 illustrates that the internal bond (IB) strength ranged from 0.2746 to 0.4688 MPa. The lowest IB value (0.2746 MPa) was recorded in untreated betung bamboo boards (control, board code I), while the maximum value (0.4688 MPa) was achieved in autoclave-treated betung bamboo boards (board code F). This enhancement can be attributed to the steam treatment’s effectiveness in reducing extractive content, thereby improving adhesive penetration into the strands and ultimately strengthening the OSB boards. These findings align with Maulana et al. [57], who confirmed that steam treatment enhances OSB properties. Adhesive composition plays a crucial role in determining the internal bonding characteristics of OSB. Higher adhesive content typically results in improved physical and mechanical performance [58]. Isocyanate adhesives offer distinct advantages in this regard, e.g., superior surface penetration resistance, ability to form minimal external and internal contact angles due to higher viscosity [59], formation of strong chemical bonds through reactive (-NCO) groups that interact with hydrogen-containing compounds [60] and excellent solubility in various solvents owing to low molecular weight, enabling deep penetration into porous structures.

Figure 11: Internal bonding value of the OSB boards. The same letter a indicates no significant difference in statistical analysis

The analysis of variance revealed that the interaction between initial treatment and bamboo species did not have a statistically significant effect on IB strength. However, steam treatment was shown to improve bond quality by minimizing extractive loss, thereby enhancing adhesive penetration and overall board integrity. This study yielded superior IB values compared to those reported by Albayudi et al. [61], whose findings ranged from 0.0726 MPa to 0.1304 MPa—significantly lower than the values obtained in the present study. According to research by Aisyah et al. [62], steam pretreatment prior to board production can substantially enhance IB strength. During steam exposure, free sugars present in wood particles undergo conversion into furan intermediates. These intermediates subsequently transform into furan resins, which reinforce both IB strength and dimensional stability of the board [62]. The IB values recorded in this study met the JIS 5908 standard, which requires a minimum IB strength of 0.1471 MPa. Furthermore, all boards complied with the CSA 0.437.0 standard, except for the betung control board, as the CSA standard mandates an IB value of ≥0.3334 MPa.

Based on research findings, bamboo represents a highly promising feedstock for manufacturing OSB panels. The physical and mechanical testing of OSB demonstrated the following property ranges: density values between 0.60 and 0.73 g/cm3, moisture content between 5.36% and 8.12%, water absorption between 31.60% and 45.82%, thickness swelling between 5.11% and 16.27%, MOE values between 2745.08 and 7183.27 MPa, MOR values between 30.79 and 58.84 MPa, and IB strength values between 0.2746 and 0.4668 MPa. Among the OSB samples tested, the best-performing board was autoclave-treated betung bamboo (board code F), achieving a score of 55. The autoclave steam process effectively reduced starch content, improving adhesive bonding and enhancing the manufacturing quality of OSB derived from betung bamboo. Overall, all boards produced in this study met the requirements outlined in the JIS A 5908 (2003) standard and the CSA 0.437.0 (2011) standard, confirming their suitability for industrial application. Future research directions could explore various pretreatment methods, including thermal and chemical modifications, to improve the adhesion and dimensional stability of OSB boards. Investigating bamboo-based OSB with environmentally friendly adhesives could further support the development of sustainable green materials. Additionally, further studies could focus on assessing the resistance of bamboo-based OSB to environmental factors such as high humidity, fungal attacks, and extreme temperature variations, ensuring long-term durability in construction applications. Further exploration could also examine the effects of different growing environments such as lowland regions, mountainous areas, and locations with varying rainfall and temperature conditions on bamboo quality and its effectiveness as an OSB material. A broader understanding of these environmental influences would provide valuable insights into optimizing bamboo-based materials for diverse industrial applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the TALENTA research World Class University, Universitas Sumatera Utara and the University of Forestry, Sofia, Bulgaria.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the TALENTA research grant scheme of the “Kolaborasi Nasional Penerima Dana Hibah WCU (World Class University) Universitas Sumatera Utara” in the year 2022 (Number: 353/UN5.2.3.1/PPM/KP-TALENTA/2022). This research was also supported by the project “Development, Exploitation Properties and Application of Eco-Friendly Wood-Based Composites from Alternative Lignocellulosic Raw Materials”, Project No. HHC-b-1290/19.10.2023, carried out at the University of Forestry, Sofia, Bulgaria.

Author Contributions: Apri Heri Iswanto: data curation, methodology, supervision, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. Nabila Nabila: data curation and methodology. Rika Elfina: data curation and methodology. Luthfi Hakim: supervision, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. Tito Sucipto: writing—review and editing. Manggar Arum Aristri: writing—review and editing. Muhammad Adly Rahandi Lubis: writing—review and editing. Widya Fatriasari: writing—review and editing. Jajang Sutiawan: writing—review and editing. Atmawi Darwis: writing—review and editing. Tomasz Rogoziński: writing—review and editing. Lee Seng Hua: writing—review and editing. Lum Wei Chen: writing—review and editing. Petar Antov: writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Apri Heri Iswanto, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Nugroho HYSH, Nurfatriani F, Indrajaya Y, Yuwati TW, Ekawati S, Salminah M, et al. Mainstreaming ecosystem services from Indonesia’s remaining forests. Sustainability. 2022;14(19):12124. doi:10.3390/su141912124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ministry of Environment and Forestry. Data Perkembangan Deforestasi Tahun 2020–2022. Jakarta, Indonesia: Direktorat Jenderal Planologi Kehutanan dan Tata Lingkungan, Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan; 2022. (In Indonesian). [cited 2025 Apr 20]. Available from: https://pktl.menlhk.go.id/. [Google Scholar]

3. Rijaya I, Fitmawati. Jenis-jenis bambu (Bambusoideae) di pulau Bengkalis, Provinsi Riau, Indonesia. Floribunda. 2019;6(2):41–52. doi:10.32556/floribunda.v6i2.2019.229 (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chaydarreh KC, Li Y, Zhou Y, Hu C. Processing, properties, potential and challenges of bamboo-based particleboard for modern construction: a review. Eur J Wood Wood Prod. 2025;8(1):1–17. doi:10.1007/s00107-024-02187-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Siam NA, Uyup MKA, Husain H, Mohmod AL, Awalludin MF. Anatomical, physical, and mechanical properties of thirteen Malaysian bamboo species. BioResources. 2019;14(2):3925–43. doi:10.15376/biores.14.2.3925-3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Barbirato GHA, Gauss C, Lopes Júnior WE, Martins R, Fiorelli J. Optimization of castor oil polyurethane resin content of OSB panel made of Dendrocalamus asper bamboo. Cienc Florest. 2022;32(1):187–205. doi:10.5902/1980509846908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Maulana S, Purusatama BD, Wistara NJ, Sumardi I. Effect of steam treatment on strand and shelling ratio on the physical and mechanical properties of bamboo oriented strand board. J Ilmu Teknol Kayu Trop. 2016;14(2):136–43. doi:10.51850/jitkt.v14i2.206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li X, Sun C, Zhou B, He Y. Determination of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin in moso bamboo by near infrared spectroscopy. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):17210. doi:10.1038/srep17210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Maulana S, Damanik MQ, Maulana MI, Fatrawana A, Sumardi I, Wistara NJ, et al. Ketahanan oriented strand board bambu betung dengan perlakuan steam pada strand terhadap cuaca (durability of oriented strand board prepared from steam-treated betung bamboo to natural weathering). J Ilmu Teknol Kayu Trop. 2019;17(1):34–46. [Google Scholar]

10. Maulana MI, Nawawi DS, Wistara NJ, Sari RK, Nikmatin S, Maulana S, et al. Change of chemical components content in andong bamboo due to steam treatment. J Ilmu Dan Teknol Kayu Trop. 2018;16(1):83–92. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/209/1/012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Huang L, He J, Tian CM, Li DW. Chapter 19–bambusicolous fungi, diseases, and insect pests of bamboo. In: Asiegbu FO, Kovalchuk ABTFM, editors. Forest microbiology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. p. 415–40. [Google Scholar]

12. Karlinasari L, Sejati PS, Adzkia U, Arinana A, Hiziroglu S. Some of the physical and mechanical properties of particleboard made from betung bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper). Appl Sci. 2021;11(8):3682. doi:10.3390/app11083682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang Q, Wu X, Yuan C, Lou Z, Li Y. Effect of saturated steam heat treatment on physical and chemical properties of bamboo. Molecules. 2020;25(8):1999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Kaushal R, Singh I, Thapliyal SD, Gupta AK, Mandal D, Tomar JMS, et al. Rooting behaviour and soil properties in different bamboo species of Western Himalayan Foothills, India. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–17. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61418-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Huang Z, Li Q, Bian F, Zhong Z, Zhang X. Effects of bamboo-sourced organic fertilizer on the soil microbial necromass carbon and its contribution to soil organic carbon in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) forest. Forests. 2025;16(3):553. doi:10.3390/f16030553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang SH, Shen Y, Lin LF, Tang SL, Liu CX, Fang XH, et al. Effects of bamboo biochar on soil physicochemical properties and microbial diversity in tea gardens. PeerJ. 2024;12(12):1–18. doi:10.7717/peerj.18642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wu Y, Guo J, Tang Z, Wang T, Li W, Wang X, et al. Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) expansion enhances soil pH and alters soil nutrients and microbial communities. Sci Total Environ. 2024;912(193–201):169346. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.169346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Maulana MI, Jeon WS, Purusatama BD, Kim JH, Prasetia D, Yang GU, et al. Anatomical characteristics for identification and quality indices of four promising commercial bamboo species in Java, Indonesia. BioResources. 2022;17(1):1442–53. doi:10.15376/biores.17.1.1442-1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. ISO 22157:2019. Bamboo structures—determination of physical and mechanical properties of bamboo culms—test methods. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization; 2019. [Google Scholar]

20. JIS A 5908 2003. Japanese industrial standard for particleboard. Tokyo, Japan: Japanese Industrial Standard; 2003. [Google Scholar]

21. Maulana MI, Marwanto M, Nawawi DS, Nikmatin S, Febrianto F, Kim NH. Chemical components content of seven Indonesian bamboo species. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020;935(1):12028. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/935/1/012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hartono R, Iswanto AH, Priadi T, Herawati E, Farizky F, Sutiawan J, et al. Physical, chemical, and mechanical properties of six bamboo from Sumatera Island Indonesia and its potential applications for composite materials. Polymers. 2022;14(22):4868. doi:10.3390/polym14224868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. SNI 7207: 2014. Uji Ketahanan Kayu Terhadap Organisme Perusak Kayu. Jakarta, Indonesia: Badan Standardisasi Nasional; 2014. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

24. Putri AR, Alam N, Adzkia U, Amin Y, Darmawan IW, Karlinasari L. Physical and mechanical properties of oriented flattened bamboo boards from ater (Gigantochloa atter) and betung (Dendrocalamus asper) bamboos. J Sylva Lestari. 2023;11(1):1–21. doi:10.23960/jsl.v11i1.614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Maulana MI, Jeon WS, Purusatama BD, Nawawi DS, Nikmatin S, Sari RK, et al. Variation of anatomical characteristics within the culm of the three gigantochloa species from Indonesia. BioResources. 2021;16(2):3596–606. doi:10.15376/biores.16.2.3596-3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chaudhary U, Malik S, Rana V, Joshi G. Bamboo in the pulp, paper and allied industries. Adv Bamboo Sci. 2024;7(10):100069. doi:10.1016/j.bamboo.2024.100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Supartini S, Dewi LM. Anatomical structure and fiber quality of Parashorea malaanonan (Blanco) Merr. J Ilmu Dan Teknol Kayu Trop. 2010;8(2):169–76. [Google Scholar]

28. Aprianis Y, Rahmayanti S. Fiber dimensions and their derived values of seven wood species from Jambi province. J Penelit Has Hutan. 2018;27(1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

29. Loiwatu M, Manuhuwa E. Chemical component and anatomical feature of three bamboo species from Seram, Maluku. AgriTECH. 2016;28(2):76–83. [Google Scholar]

30. Larsson PT, Lindström T, Carlsson LA, Fellers C. Fiber length and bonding effects on tensile strength and toughness of kraft paper. J Mater Sci. 2018;53(4):3006–15. doi:10.1007/s10853-017-1683-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gao X, Zhu D, Fan S, Rahman MZ, Guo S, Chen F. Structural and mechanical properties of bamboo fiber bundle and fiber/bundle reinforced composites: a review. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;19(1):1162–90. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.05.077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Sarogoro D, Emerhi EA. Runkel, flexibility and slenderness ratios of Anthocleista djalonensis (A) wood for pulp and paper production. Afr J Agric Technol Env. 2016;5(2):27–32. [Google Scholar]

33. Mariana M, Alfatah T, Abdul Khalil HPS, Yahya EB, Olaiya NG, Nuryawan A, et al. A current advancement on the role of lignin as sustainable reinforcement material in biopolymeric blends. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;15(1):2287–316. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.08.139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Amiruddin AA, Parung H, Sibela N, Fajar MN, Arifin H. The effect of bamboo water content on the tensile strength of bamboo. IOP Conf Ser Earth Env Sci. 2022;1117(1):12008. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1117/1/012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Rusch F, Wastowski AD, de Lira TS, Moreira KCCSR, de Moraes Lúcio D. Description of the component properties of species of bamboo: a review. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023;13(3):2487–95. doi:10.1007/s13399-021-01359-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Gu S, Lourenço A, Wei X, Gominho J, Wang G, Cheng H. Structural and chemical analysis of three regions of bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Materials. 2024;17(20):5027. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4372670/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Darwis A, Iswanto AH. Morphological characteristics of Bambusa vulgaris and the distribution and shape of vascular bundles therein1. J Korean Wood Sci Technol. 2018;46(4):315–22. doi:10.5658/wood.2018.46.4.315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Seta FT, Sugesty S, Kardiansyah T. Making of nitrocellulose from various commercial dissolving pulps as propellant raw materials. J Selulosa. 2014;4(02):97–106. [Google Scholar]

39. Felisberto MHF, Beraldo AL, Costa MS, Boas FV, Franco CML, Clerici MTPS. Bambusa vulgaris starch: characterization and technological properties. Food Res Int. 2020;132(1–2):109102. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Pędzik M, Janiszewska D, Rogoziński T. Alternative lignocellulosic raw materials in particleboard production: a review. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;174(3):114162. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Nourbakhsh A, Ashori A, Jahan-Latibari A. Evaluation of the physical and mechanical properties of medium density fiberboard made from old newsprint fibers. J Reinf Plast Compos. 2010;29(1):5–11. doi:10.1177/0731684408093972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Korai H. Effects of density profile on bending strength of commercial particleboard. Prod J. 2022;72(2):85–91. doi:10.13073/fpj-d-21-00070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Si S, Zheng X, Li X. Effect of carbonization treatment on the physicochemical properties of bamboo particleboard. Constr Build Mater. 2022;344(1):128204. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.128204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Tolessa A, Woldeyes B, Feleke S. Chemical composition of lowland bamboo (Oxytenanthera abyssinica) grown around Asossa Town. Ethiopia World Sci News. 2017;74:141–51. [Google Scholar]

45. Zhao B, Hu S. Promotional effects of water-soluble extractives on bamboo cellulose enzymolysis. BioResources. 2019;14(3):5109e20. doi:10.15376/biores.14.3.5109-5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]