Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Sn-Lignosulfonate Catalyst for the Dehydration of Xylose into Furfural in a Biphasic System

1 State Key Laboratory of Advanced Papermaking and Paper-Based Materials, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, 510640, China

2 Guangzhou Institute of Energy Conversion, Chinese Academy of Sciences, CAS Key Laboratory of Renewable Energy, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of New and Renewable Energy Research and Development, Guangzhou, 510640, China

* Corresponding Author: Junli Ren. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(11), 2091-2107. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0060

Received 17 March 2025; Accepted 28 April 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

It is highly attractive for the catalysts prepared from renewable materials and/or industrial by-products. Herein, lignosulfonate (LS) as the by-product in the papermaking industry was utilized to fabricate Sn-containing organic-inorganic complexing catalysts (Sn(x)@LS) by a simple hydrothermal self-assembly process. The fabricated Sn(x)@LS played an excellent performance in the dehydration of xylose into furfural in the carbon tetrachloride (CTC)-water biphasic system, yielding 78.5% furfural at 180°C for 60 min. It was revealed that strong coordination between Sn4+ and the phenolic hydroxyl groups of LS created a robust organic-inorganic skeleton (-Ar-O-Sn-O-Ar-), simultaneously generating potent Lewis acidic sites, and sulfonic acid groups of LS acted as Brønsted acidic sites. Gromacs simulations verified that CTC did not form hydrogen bonds with xylose, which may reduce xylose consumption. The CTC phase effectively extracted furfural, thereby preventing its side reactions throughout the entire process. In addition, Sn(x)@LS exhibited excellent cyclic stability in at least five reaction cycles with only a 5.0% decrease in furfural yield. Thus, this work will give a new window for the catalysts prepared from LS as the industrial by-products in the production of platform chemicals, which is a sustainable chemical conversion process.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileBiomass is the largest carbon-neutral renewable resource, offering a promising alternative for energy and material production to reduce our dependence on finite fossil fuel sources and mitigate related environmental issues [1,2]. Furfural, as a high value-added platform chemical derived from biomass, can be converted into a wide range of important chemicals and fuels such as furfuryl alcohol, maleic acid, succinic acid, tetrahydrofuran, γ-valerolactone, and straight-chain alkanes, which have been widely used in the fields of petroleum refining, plastics, pharmaceuticals, and agrochemicals [3,4].

Currently, catalysts used for furfural production include homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts, heterogeneous catalysts have been increasingly researched and developed due to their advantages of low corrosiveness to equipment, good hydrothermal stability, ease of separation and recyclability. For instance, catalysts based on hydrotalcite [5], zeolite [6], acidic resins [7], bifunctional solid acids [8] and carbonaceous solid acid [9] have been applied. Among these heterogeneous catalysts, metal ion-loaded catalysts attract the attention of researchers due to their excellent catalytic activity and renewability. For example, P-ZrSBA-15 [10], SO3H@Fe/MC [11], Cr-deAl-Y [12], Cr-Mg-LDO@bagasse [13], Sn-MMT [14], have been widely prepared and investigated for furfural production from xylose. However, these catalysts still suffer from some drawbacks, such as the high cost of non-renewable feedstock and the complicated preparation process. Therefore, there is a pressing need to explore more efficient, sustainable, and economical catalysts. In the process of furfural preparation, not only does the catalyst play an important role, but also the solvent system plays a crucial role in determining the reaction environment, which in turn affects the conversion of xylose, as well as the generation, distribution, degradation, and separation of furfural products, ultimately affecting the furfural yield [15].

Water is an environmentally friendly solvent system, but its acidic form under high temperature tends to cause furfural molecules to polymerize and form humic substances, leading to lower yields [16,17]. A viable methodological approach involves conducting the reaction within an aqueous-organic biphasic configuration, where immiscible phases comprising polar aqueous media and non-polar organic solvents facilitate enhanced phase-segregated catalytic processes [18,19]. Thereafter, some organic solvents, including methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK) [20], 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MTHF) [21], toluene [22], cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) [23], and 1,4-dioxane [24] have been used for the biphasic dehydration of xylose. In the biphasic systems, organic solvents significantly influence the reactions. The solvent is the medium in direct contact with the reactants, products, and catalysts, and xylose conversion and furfural yield are affected by xylose solubility, furfural extraction, solvent distribution around xylose/furfural, hydrogen bonding, and solvent degradation behavior. Therefore, the selection of suitable organic solvents is crucial, and we can match solvents and catalysts to create a sustainable reaction system for the efficient production of furfural.

Lignin, as the second most abundant lignocellulosic biomass component in nature after cellulose, is a renewable resource with broad applications in industrial fields such as concrete additives, dispersants, coatings, modifiers, carbon materials, corrosion inhibitors, and surfactants [25]. Among its derivatives, lignosulfonate (LS), a typical sulfonated industrial lignin, exhibits unique structural characteristics that render it particularly promising for catalytic applications. Abundant active phenolic hydroxyl and alcohol hydroxyl groups present in its structure, enabling facile coordination with metal ions to form metal-biomolecule hybrid frameworks with tunable Lewis acid (LA) sites [26]. Meanwhile, due to the presence of a large number of sulfonic acid groups attached to aliphatic carbons via -C-S bonds in its structure, these sulfonic acid groups can be used as Brønsted acidic (BA) catalytic sites, thus avoiding the complicated sulfonation procedure. The good coordination properties with metals and inherent sulfonic acid groups make LS an ideal candidate for the fabrication of high-performance solid acid catalysts for furfural production [27].

In comparison with other solid catalysts such as carbon-based catalyst, cation exchange resin and modified zeolit, herein, this work aims to prepare a novel Sn-LS organic-inorganic complexing catalyst (Sn(x)@LS) through a simple hydrothermal molecular self-assembly strategy, using LS as the raw material from the by-products in the papermaking industry. The preparation process is simple by eliminating the need for sulfonation steps, thereby avoiding the use of hazardous sulfonating agents (e.g., concentrated H2SO4 or chlorosulfonic acid), also this method provides new ideas for the high value-added utilization of by-products from papermaking industry. This not only reduces environmental risks but also lowers operational costs. Significantly, the three distinctive features of Sn(x)@LS include the inherent BA sites, the strong LA catalytic sites formed by coordination interactions between Sn4+ and phenolic hydroxyl groups (-Ar-OH) and the robust inorganic-organic skeleton, in which this chemical bonding endows the catalyst with enhanced structural stability and exceptional reusability, as the anchored Sn species resist leaching under reaction conditions. The as-prepared Sn(x)@LS polyphenol polymer catalysts were used for the dehydration of xylose to produce furfural, resulting in a furfural yield of 78.5% under the carbon tetrachloride (CTC) and water biphasic system, where CTC formed a protective shell around furfural. In addition, excellent cycling stability was demonstrated over at least five reaction cycles. Therefore, high value-added catalysts and platform chemicals were prepared from biomass derivatives, which helps to open up new possibilities for cost-effective, environmentally friendly, and renewable biomass conversion processes.

D(+)xylose (≥99.5%, AR) was purchased from Tianjin Kermal Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China. Sodium lignosulfonate (≥99.5%, AR), Al(NO3)3 · 9H2O (≥99.0%, AR), Cu(NO3)2 · 3H2O (≥99.0%, AR), Cr(NO3)3·9H2O (≥99.0%, AR), Zr(NO3)4 · 5H2O (AR), SnCl4 · 5H2O (≥99.0%, AR), SnO2 (≥99.5%, AR), CTC (≥98.0%), methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK) (≥99.0%), methyl isopropyl ketone (MIPK) (≥99.0%), dimethyl carbonate (DMC) (≥99.0%), cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) (≥99.0%), 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (MTHF) (≥99.0%), ispropyl acetate (IPA) (≥99.0%) and toluene (PhMe) (≥99.0%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. NaCl (≥98.0%, AR) was purchased from the Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory, Guangzhou, China. Ethanol (≥98.0%, AR) was purchased from Huangyuancan Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. The standard xylose and furfural (≥99.0%, HPLC) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Industrial Corporation, St. Louis, MO, USA. All chemical reagents were obtained commercially purchased without further purification.

The Sn(x)@LS catalysts (x = 10, 15, 20, 25 or 30, which stands for the amount of Sn added, for example, x = 10 means the addition of 10% by mass of Sn to LS) were synthesized by a simple hydrothermal self-assembly method. In a typical preparation procedure of Sn(20)@LS catalyst, SnCl4 · 5H2O (2.954 g) and LS (5.0 g) were dissolved respectively in 15 and 50 mL of water and sonicated for 5 min to form an aqueous solution. After that, the two precursor solutions were combined and magnetically stirred at room temperature for 15 min. The homogenized mixture was subsequently transferred to a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave and subjected to hydrothermal treatment at 120°C for 12 h. After the hydrothermal reaction, the autoclave was rapidly cooled to room temperature via water quenching. The resulting dark brown precipitate was centrifuged and washed with deionized water and ethanol. The M(20)@LS catalysts (M = Sn, Zr, Al, Cr; the metal added is 20%) were synthesized just following the preparation process of Sn(20)@LS catalyst.

2.3 Procedures for Furfural Manufacturing from Xylose

The xylose conversion process was carried out in a hydrothermal reactor, which was a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave that had precision threads for pressing the Teflon-lined in a hermetic environment. Typically, xylose (0.1 g), solvent (15 mL), and catalyst (0–0.1 g) were mixed in a hydrothermal reactor. The reaction was performed at a certain temperature (160°C–190°C) with magnetic stirring for a required time (0–90 min). At the end of the reaction, the autoclave was quickly cooled to room temperature with running water. All the organic and aqueous solutions were respectively filtered with a 0.22 μm syringe filter before analysis.

2.4 Catalysts Characterization

Scanning electron microscopes (SEM) were taken using a field emission scanning electron microscope (SU8220, Hitachi) at an accelerated voltage of 5 kV. X-ray diffraction (XRD) in reflection mode was collected by D8Advance with CuKa radiation. The scanning step is 0.02°/2θ, and the diffractogram is measured in the range of 5°–90° (2θ). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis of catalyst structures was conducted on Bruker TENSOR 27 FT-IR spectrometer within the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was performed using a Kratos Axis Ultra DLD spectrometer under ultrahigh vacuum conditions. The thermal stability of different samples was examined using a Mettler Toledo thermal analyzer (TGA) with temperatures from 40°C to 800°C under flowing N2 (heating rate of 10 K/min). Pyridine-adsorbed FT-IR spectroscopy was performed on a PE-FTIR Frontier spectrometer (4000–400 cm−1, KBr pellet method) to characterize acid site distribution across catalysts. The acidity of different samples was characterized via NH3 temperature-programmed desorption (NH3-TPD) by TP5080 equipment. The contents of Sn and other metal ions in the catalysts were quantified by ICP-OES equipment (Agilent 720 EX).

The concentration of xylose and furfural in the aqueous phase and organic phase were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with a RID detector (Agilent 1260) and an HPX-87H column (BIO-RAD). The mobile phase was 5 mM H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.5 mL · min−1. The temperature of the detector and column oven was maintained at 40°C and 60°C, respectively. The concentrations of xylose and furfural were calculated by the external standard method. Xylose conversion and furfural yield were calculated based on the following Eqs. (1) and (2):

3.1 Characterization of Catalysts

Fig. 1a shows a schematic diagram of the preparation process and structural evolution of Sn(20)@LS catalyst. Firstly, LS is mixed with SnCl4 to form a homogeneous aqueous solution. In the subsequent hydrothermal process, due to complexation, Sn4+ reacts with the -Ar-OH in LS, and the degree of complexation gradually increases with time until the formation of a water-insoluble precipitate, which is washed to obtain the Sn(20)@LS catalyst. Fig. 1b,c shows the SEM images of Sn(20)@LS. Obviously, Sn(20)@LS is composed of a range of nanoparticles with varying sizes. SEM-mapping (Fig. 1d) shows a strong C, Sn, O and S signal in Sn(20)@LS and it also demonstrates that the elements C, Sn, O and S are uniformly distributed throughout Sn(20)@LS.

Figure 1: Synthesis procedure and morphology characterizations. (a) Hydrothermal synthesis process of Sn(x)@LS. (b, c) SEM images of Sn(20)@LS. (d) Elemental mappings of C, Sn, O, and S

Furthermore, the XRD patterns in Fig. 2a show that Sn(x)@LS exhibits few broadened diffractions without significant crystallinity, demonstrating distinct differences from the tetragonal (t) structure of highly crystalline SnO2 (Fig. S1). This proves that the Sn species does not exist in Sn(x)@LS as an oxide and the amorphous structure of Sn(x)@LS [28].

Figure 2: (a) XRD patterns of various catalysts. (b) FT-IR spectra of various catalysts. (c) C 1s, (d) O 1s, (e) Sn 3d. (f) S 2p XPS spectra of various catalysts. (g) TG and (h) DTG curves of various catalysts

In addition, the Sn(x)@LS catalysts were subjected to FT-IR analysis to determine the types of functional groups on the catalysts. As shown in Fig. 2b, a pronounced absorption band at 1610 cm−1, characteristic of conjugated aromatic C=C bond stretching vibrations, is preserved across both LS and Sn(x)@LS. The FT-IR spectra of LS and Sn(x)@LS show characteristic antisymmetric -Ar-OH stretching (LS, 1521 cm−1; Sn(x)@LS, 1510 cm−1) and symmetric -Ar-OH stretching (LS, 1460 cm−1; Sn@LS, 1456 cm−1) of the -Ar-OH on the LS chains [29]. The narrowing of these two different types of peaks from 61 to 54 cm−1 compared to the spectra of LS may be due to the coordination of the -Ar-OH of LS with Sn4+ ions. The altered transmittance at 1116 and 1045 cm−1 is attributed to the antisymmetric SO2 stretching vibration and S=O symmetric stretching vibration of the sulfonic acid group in the LS chain, respectively [30]. The samples also exhibit broadened absorption features at 653 and 530 cm−1, corresponding to characteristic vibrational signatures of sulfonic acid-derived -C-S bonds. These spectral characteristics are associated with residual sodium sulfite/bisulfite species embedded during the sulfite pulping protocol [31]. These FT-IR characteristic peaks indicate that there is still an abundance of sulfonyl functional groups.

The local environments of the elements C, O, Sn, and S in Sn(20)@LS were analyzed by XPS techniques to deconvolve the signals of C, O, Sn, and S to analyze their elemental valence and chemical states further. The measured spectra in Fig. S2 likewise confirm the presence of Sn, O, C, and S in Sn(20)@LS. In the high-resolution C 1s spectra of Sn(20)@LS and LS (Fig. 2c), the peaks at 284.8, 286.2 and 288.5 eV can be indexed to C-C/C=C, C-O/C-S, and C-C=O bonds, respectively [32]. The O 1s spectra of Sn(20)@LS and LS can be deconvoluted into three types of oxygen at 532.0, 533.3, and 536.1 eV corresponding to C-O-C, C=O, and C-OH bonds, respectively (Fig. 2d) [33]. Notably, the characteristic peak corresponding to the C-OH functional group disappears in the Sn(20)@LS catalyst compared to the LS framework. The disappearance of the peak of functional group C-OH upon loading Sn on the Sn(20)@LS catalyst compared to LS is likely attributed to the interaction and coordination between Sn4+ and the C-OH groups. The Sn 3d peaks indicate that interestingly, the binding energies of Sn 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 of Sn(20)@LS are elevated to 487.6 and 496.0 eV, respectively, compared to pure SnO2 487.1 and 495.5 eV (Fig. 2e). Combined with the altered O 1s spectrum of Sn(20)@LS, this phenomenon suggests that Sn4+ interacts and coordinates with O2− resulting in more positively charged Sn4+, thus exhibiting stronger Lewis acidity at the Sn4+ center [18]. For S 2p spectra, peaks at 168.3 and 169.5 eV correspond to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbits of the -SO3H group, respectively (Fig. 2f), which clearly indicates that still possesses a large number of sulfonic acid groups after the hydrothermal self-assembly process. These sulfonic acid groups in Sn(20)@LS can promote the formation of BA sites to facilitate the catalytic reaction [34]. The XPS results reveal that the functional groups in LS can stabilize the LA site (Sn) and in turn form -Ar-O-Sn-O-Ar- skeleton structures.

TG and DTG analyses were performed to investigate the thermal stability of Sn(x)@LS and LS across a temperature range of 40°C–800°C (Fig. 2g,h). The LS matrix exhibited sequential thermal degradation events at 100.7°C and 257.8°C, corresponding to the evaporation of physisorbed water and oxidative decomposition of organic constituents, respectively, demonstrating its inherent thermal instability. In contrast, the primary decomposition temperature of Sn(20)@LS shifted to 358.2°C relative to the decomposition temperature of LS of 257.8°C. The higher decomposition temperature verified the stability of the catalyst backbone of the Sn(20)@LS catalyst, which laterally confirms the coordination between LS and Sn4+ ions. In addition, the decomposition mass of Sn(20)@LS decreases gradually with the increase of the coordination amount of Sn4+ ions.

We examined and compared the acid properties of Sn(20)@LS and SnO2 using the NH3-TPD (elevated temperature programmed desorption) method. In general, the desorption of NH3 reflects the strength and density of the catalyst acidity. Compared to commercial SnO2 (0.041 mmol/g), Sn(20)@LS (1.439 mmol/g) has higher acidity and abundant acidic sites content (Fig. 3a). This is attributed to that the coordination between the -Ar-OH and Sn4+ promotes the formation of a robust -Ar-O-Sn-O-Ar- skeleton with highly acidic Sn4+ upon the hydrothermal treatment of LS and SnCl4.

Figure 3: (a) NH3-TPD of SnO2 and Sn(20)@LS. (b) Pyridine-adsorbed FT-IR spectra of SnO2, LS and Sn(20)@LS

To gain more insight into the LA and BA sites of the catalysts, pyridine-adsorbed FT-IR spectra were carried out under vacuum at two desorption temperatures, 110°C and 250°C, respectively. From Fig. 3b, it can be seen that Sn(20)@LS shows the LA band at the wavenumber of 1450 cm−1, BA band near wavenumbers of 1490, 1600, and 1640 cm−1, and both LA and BA bands at 1490 cm−1. The low-temperature desorption peak (110°C) corresponds to a weak acid center, and the high-temperature desorption peak (250°C) corresponds to a strong acid center [35]. The LA center of Sn(20)@LS is supposed to originate mainly from the Sn4+ center, and the BA center is mainly from -SO3H. BA sites (-SO3H) are formed because of the occurrence of proton exchange between Na+ and H+ [36]. In addition, quantitative analyses show that the LA amounts of Sn(20)@LS are 0.111 and 0.039 mmol/g at 110°C and 250°C, respectively, and the BA amounts are 0.036 and 0.026 mmol/g at 110°C and 250°C, respectively, which are significantly stronger than that of commercial SnO2 (Table S1). Meanwhile, the LA content of LS is 0.075 and 0.030 mmol/g at 110°C and 250°C, respectively. The result suggests that the coordination of Sn4+ significantly increases the LA content relative to LS.

3.2 Catalytic Properties of Catalysts and Effects of Organic Solvent Types

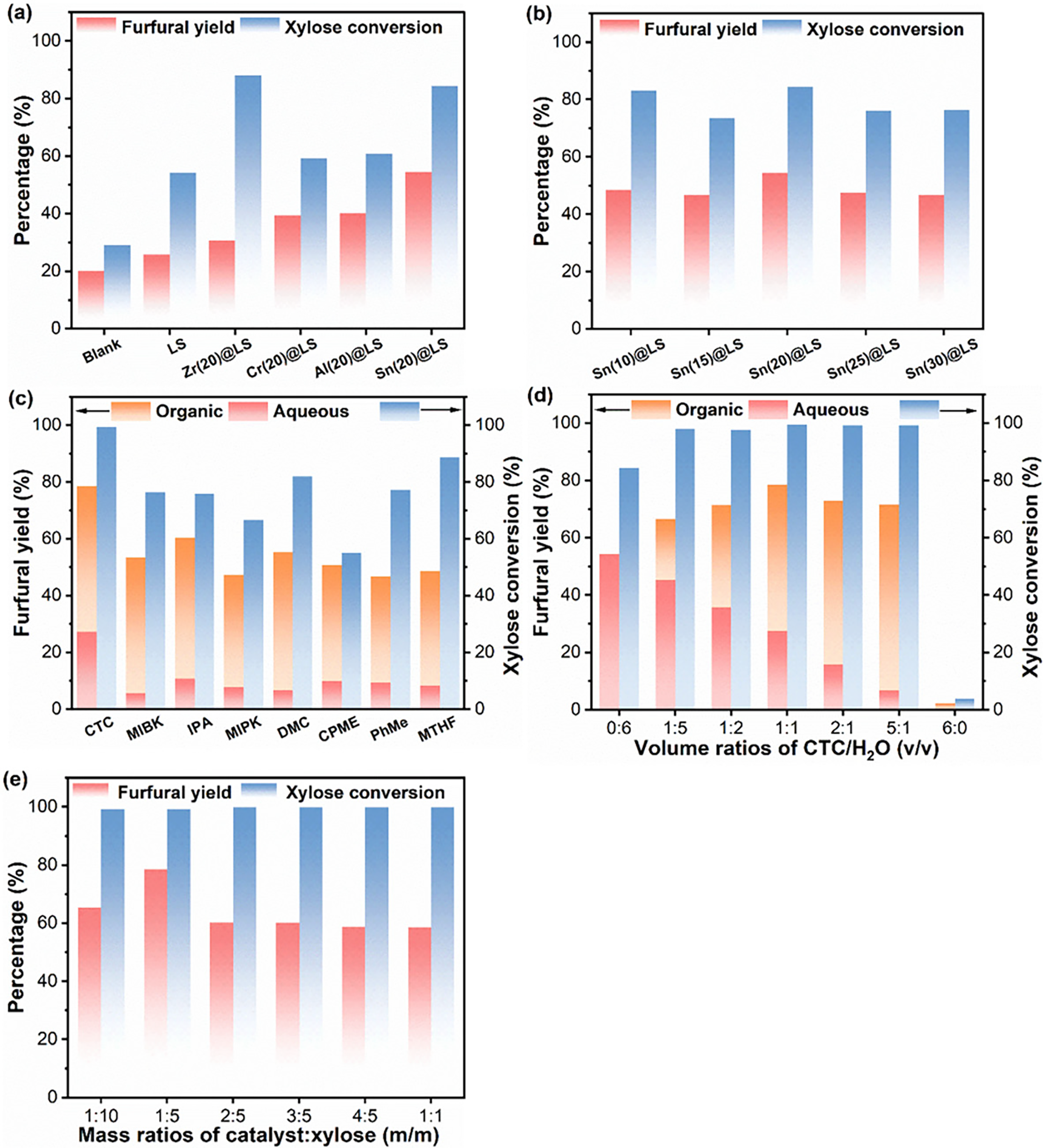

In the initial catalytic tests, water was first chosen as a typical solvent to assess the catalytic performance of as-prepared catalysts at 180°C for 60 min. In the absence of a catalyst, the conversion of xylose was 29.1%, with a furfural yield of 20.0% attributed to H+ ionization in water (Fig. 4a) [37]. When the precursor LS was employed as a catalyst for the xylose dehydration reaction, the abundance of sulfonic acid groups (-SO3H, Brønsted acid (BA) sites) contributed to xylose activation and conversion, making LS highly active and resulting in a xylose conversion of 54.2%. However, the addition of LS failed to improve the furfural yield significantly. It is worth mentioning that the production of furfural from xylose is a cascade process involving isomerization and dehydration, where isomerization serves as the pivotal rate-limiting step driven by Lewis acid (LA) sites [24,38]. Notably, with the introduction of metal species (Zr, Cr, Al, and Sn), the as-prepared M(20)@LS catalysts exhibited higher xylose conversion (59.1%–88.1%) and furfural yield (30.7%–54.4%). Specifically, when Sn(20)@LS was applied as the catalyst, up to 84.4% xylose conversion and 54.4% furfural yield were achieved. These results strongly demonstrate that the introduced metal species (LA sites) effectively modulated the acidic properties, playing a crucial role in promoting furfural production from xylose. As reported in previous studies, the Lewis acidity strength of the metal species in this study followed the order: Sn4+ (0.69) > Zr4+ (0.589) > Al3+ (0.583) > Cr3+ (0.5) [39,40]. Correlating with the experimental data, it was observed that the metal species’ efficacy in promoting furfural production aligned with their LA strength order, suggesting that—except for Zr4+—stronger LA sites enhanced furfural production. When Zr(20)@LS was used as the catalyst, 88.1% xylose conversion was attained, yet the furfural yield remained only 30.7%. This discrepancy may be attributed to Zr(20)@LS facilitating the conversion of xylose into alternative products and/or promoting further reductive transformation of furfural, thereby reducing the furfural yield [41].

Figure 4: (a, b) Activity evaluation of various catalysts at 180°C for 60 min, water as solvent for furfural production. (c) Solvent effect on furfural production. Reaction condition: 180°C for 60 min, organic solvent (7.5 mL), H2O (7.5 mL). (d) Effect of various volume ratios of CTC and water on furfural yield. Reaction condition: 180°C for 60 min. (e) Effect of catalyst dosage on furfural yield. Reaction condition: 180°C for 60 min, water (7.5 mL), CTC (7.5 mL)

In addition, the effect of Sn addition (10%–30%) during catalyst preparation was investigated, with results shown in Fig. 4b. The highest xylose conversion (84.4%) and furfural yield (54.4%) was achieved when Sn loading was increased from 10% to 20%. Notably, further increasing Sn content to 30% led to a significant decrease in both xylose conversion (76.3%) and furfural yield (46.8%), demonstrating that Sn loading significantly influences catalytic activity. As revealed in Table S2, the sulfur content (-SO3H groups) in the prepared catalysts varied with increasing Sn loading, indicating corresponding changes in Brønsted acid (BA) and Lewis acid (LA) sites. The Sn(20)@LS catalyst, containing optimal amounts of Sn (LA sites) and S (BA sites), exhibited substantially higher catalytic performance and furfural yield compared to other Sn(x)@LS catalysts. These results clearly demonstrate that balanced LA and BA sites synergistically enhance furfural production from xylose.

To gain insight into the solvent effect that was crucial for the conversion of xylose to furfural, eight mixed organic solvents (organic solvent: H2O = 1:1) were tested as the reaction medium. Fig. 4c demonstrated that xylose conversion and furfural yield were significantly affected by different solvents. The CTC-H2O system was particularly effective, achieving nearly quantitative xylose conversion (99.4%) and the highest furfural yield (78.5%) compared to the pure aqueous system and other biphasic systems under the same reaction conditions. The furfural yields of the other organic solvent-H2O systems were ranked from highest to lowest: IPA-H2O, DMC-H2O, MIBK-H2O, CPME-H2O, MTHF-H2O, MIPK-H2O, and PhMe-H2O. Gromacs simulations of the behavior of xylose and furfural in different biphasic organic solvents are explained in SI (Table S3). Molecular dynamics simulations showed that xylose and furfural were well confined in the aqueous and organic phases in the CTC-H2O and PhMe-H2O systems, respectively, whereas in the IPA-H2O, MIPK-H2O, and DMC-H2O system, xylose and furfural had chaotic trajectories due to the stronger mutual solubility of IPA, MIPK, and DMC with water (Fig. S3). The CTC-H2O system still had obvious phase separation after simulation, indicating that the CTC phase could effectively extract furfural throughout the reaction to avoid its side reaction, which might be one of the reasons for its higher furfural. Of the eight systems simulated, only IPA had a hydrogen bonding association with furfural, which may cause furfural to react with it and reduce the yield of furfural (Table S4). The lack of hydrogen bonding between the other organic solvents and furfural kept the furfural molecule in a relatively stable state and provided a protective shell for furfural. In addition, there is no hydrogen bonding produced between xylose and organic solvents in the CTC-H2O system, which may reduce the unwanted consumption of xylose. The radial distribution function curves showed that in the systems of CTC-H2O, MIBK-H2O, MIPK-H2O, CPME-H2O, and MTHF-H2O the density of water molecules around the xylose is higher and the molecular density of organic solvents is lower in these systems (Figs. S4 and S5). In IPA-H2O, DMC-H2O, and PhMe-H2O the molecules and the density of the water molecules decreased in these two systems, and it also indicated that IPA, DMC, and PhMe had a stronger affinity for xylose than the first five organic solvents, in agreement with the hydrogen bonding data.

Additionally, the ratio of organic solvent to water affected the dissolution of xylose as well as the extraction of furfural, thus, the effect of the ratio of CTC to H2O on the production of furfural from xylose was investigated. As shown in Fig. 4d, the yield of furfural was only 54.4% when deionized water was used as the reaction system (VCTC:VH2O = 0:6), which increased to 66.5% with the addition of CTC to the aqueous phase (VCTC:VH2O = 1:5). Then, the yield of furfural increased with the increasing volume ratio of CTC in the reaction system, reaching a maximum value of 78.5% as VCTC:VH2O increased to 1:1. As anticipated, the higher amount of organic solvent improved the ability of furfural to be extracted from the aqueous phase to the organic phase and reduced the occurrence of furfural side reactions. However, when VCTC:VH2O was increased further to 5:1, the yield of furfural decreased to 71.5%. Moreover, using pure CTC as the reaction system (VCTC:VH2O = 6:0), the furfural yield decreased to 2.3%. This is principally attributed to the water content in the system decreasing with increasing CTC content at a constant total volume, resulting in lower solubility of xylose as well as weaker interaction between xylose and the catalyst, which is not conducive to the cascade-catalyzed reaction of xylose to furfural.

In general, elevated catalyst dosages generally enhance product yields through accelerated reaction kinetics, yet excessive acidic conditions may paradoxically induce deleterious side processes including condensation and resinification, ultimately diminishing target compound productivity [42]. To elucidate this optimization balance on the conversion of xylose to furfural, a series of different catalyst dosages was used with a fixed dose of xylose (0.1 g) as the substrate. As shown in Fig. 4e, the effect of the catalyst to xylose mass ratio in the CTC-H2O system was investigated by reacting at 180°C for 60 min with Sn(20)@LS as the catalyst. Furfural yield increased as the mass ratio of catalyst to xylose increased from 1:10 to 1:5 reaching a maximum (78.5%) at 1:5. It indicated that the increase of catalyst dosage was favorable for the catalytic reaction. However, a decrease in furfural yield was observed when the mass ratio of catalyst to xylose continued to increase from 1:5 to 1:1. This is because the catalyst active sites are directly proportional to the amount of catalyst, when too much catalyst is added, excess active sites can lead to condensation and degradation of the products [43]. The addition of NaCl has the ability of phase separation, which is more favorable for furfural to enter the organic phase, thus increasing the yield of furfural [44–46]. Therefore, we replaced the aqueous phase with a saturated NaCl solution for xylose catalytic experiments (Table S5). In this work, the enhancement of furfural yield by NaCl was not significant and it would increase the cost of separation, so the aqueous solution was still used for the subsequent reaction.

3.3 Effects of Reaction Temperature and Reaction Time

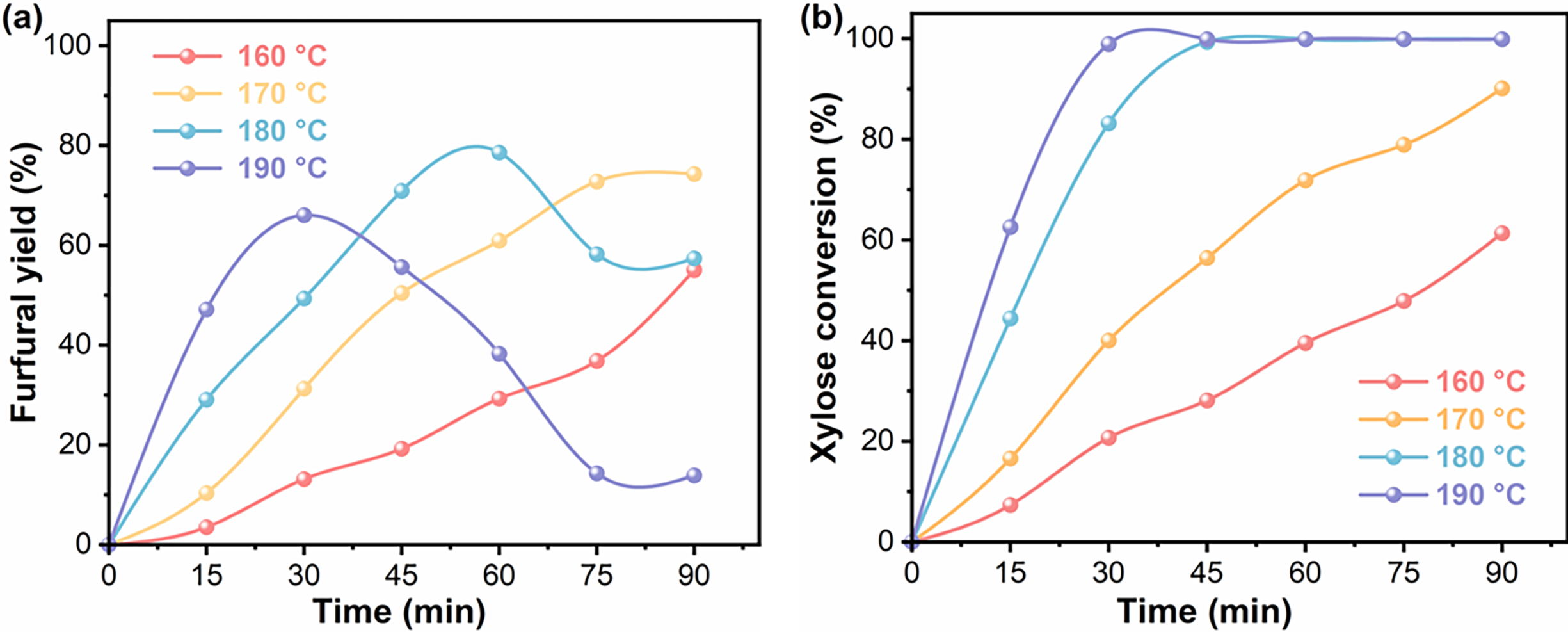

Thermodynamic parameters and temporal conditions critically govern furfural production efficiency in xylose conversion systems. Employing Sn(20)@LS as the catalyst, this investigation systematically evaluated thermal regimes (160°C–190°C) and reaction durations (15–90 min) as interdependent process variables. Fig. 5 quantitatively illustrated the resultant xylose transformation and optimized furfural yield profiles under these controlled operational parameters. The highest furfural yield and selectivity of 78.5% and 99.4%, respectively, were obtained at a reaction temperature of 180°C and a reaction time of 60 min. The furfural yield increased significantly as reaction time increased at reaction temperatures of 160°C and 170°C (3.5%–55.1%; 10.4%–74.3%). Because xylose conversion was low at low temperatures, increased time and temperature resulted in higher xylose conversion and thus higher furfural yield. When the temperature was further increased to 180°C, the furfural yield continued to increase for the first 60 min and achieved a maximum of 60 min. However, the furfural yield decreased when the reaction time was constantly extended, which was due to the side reaction of furfural under higher temperatures. Furfural’s furan ring and aldehyde group could lead to some yield-reducing reactions between furfural and intermediated to produce humic acid [43,47]. When the temperature was increased to 190°C, the maximum furfural yield was obtained at 30 min, after which the furfural yield decreased over time, suggesting that increasing the reaction temperature accelerated the xylose dehydration process and shortened the time to obtain the highest furfural yield. Excessively high temperatures could cause xylose and furfural polycondensation reactions, causing the deposition of insoluble by-products on the catalyst surface and diminishing the catalytic efficacy [12].

Figure 5: (a) Effects of reaction temperature on furfural yield. (b) Effects of reaction temperature on xylose conversion. Reaction condition: xylose (0.1 g), catalyst (0.02 g), water (7.5 mL), CTC (7.5 mL)

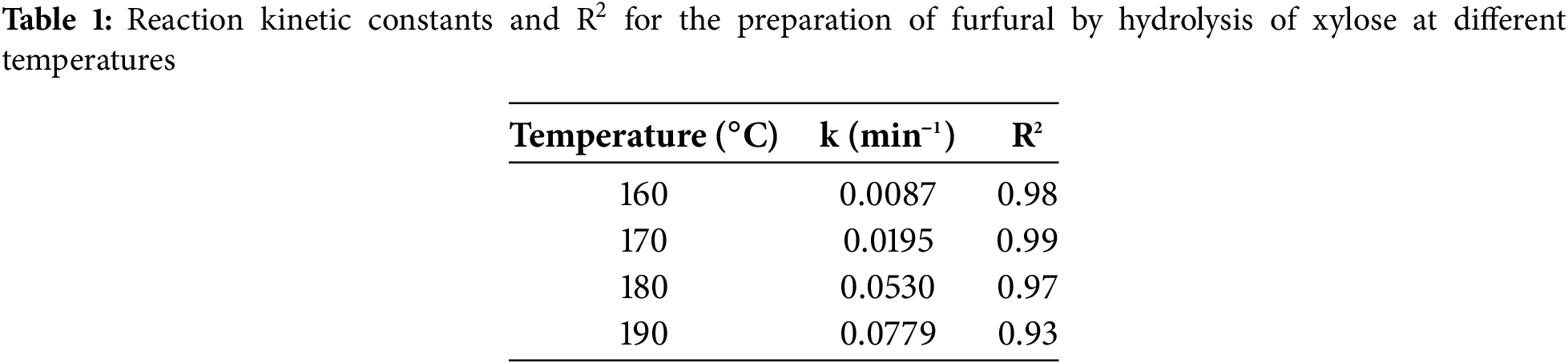

3.4 The Reaction Kinetics Study

The kinetics of furfural preparation from xylose is consistent with first-order reaction kinetics [38]. In this study, under the assumption that the total reaction rate is independent of the mass transfer effect, the corresponding reaction rate constants (k) are obtained by fitting -ln(Ct/C0) vs. reaction time at different temperatures (160°C, 170°C, 180°C, 190°C) and the results of the fitting are presented in Table 1. The rate constants for the reaction at 160°C, 170°C, 180°C, and 190°C are found to be 0.0087, 0.0195, 0.0530, and 0.0779 min−1, respectively. It can be found that the reaction rate increases with the increase of reaction temperature, proving that the temperature increase is favorable for the conversion of xylose (C0 and Ct represent the initial xylose concentration and the xylose concentration at time t, respectively).

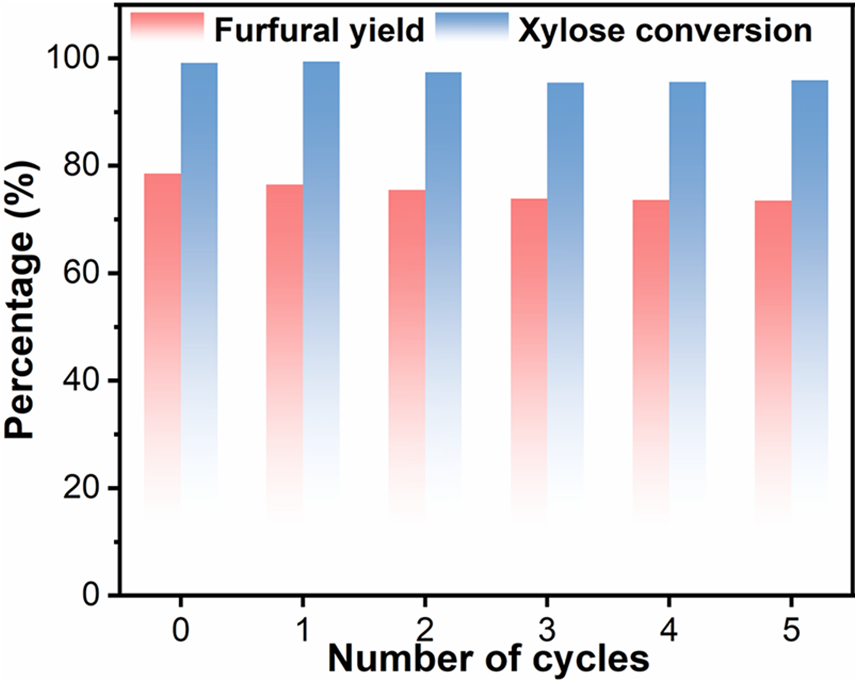

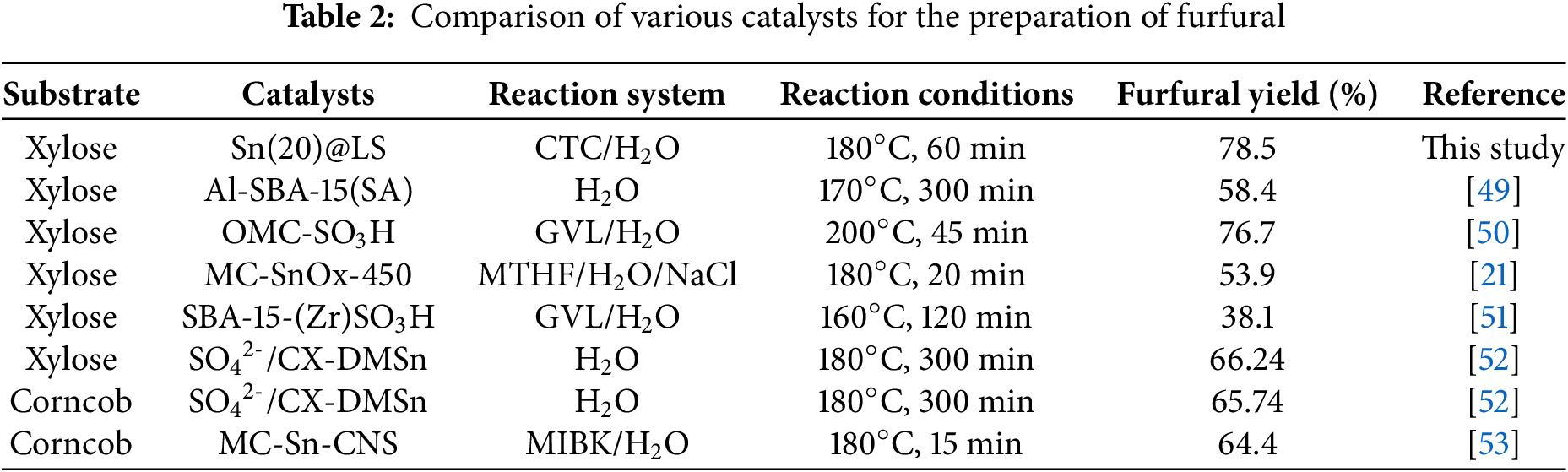

Recycling experiments were conducted to assess the recycling stability of the catalysts. The xylose conversion (from 99.4% to 95.9%) and furfural yield (from 78.5% to 73.5%) are only decreased in five consecutive reaction cycles (Fig. 6). The recycled Sn(20)@LS after the fifth run was characterized by SEM, XRD, FT-IR, TGA, and ICP-OES. SEM, XRD patterns, and FT-IR proved that the amorphous morphology and microstructures of the recovered Sn(20)@LS remained largely unchanged as compared to that of the fresh catalyst (Fig. S6a–d). The TG and DTG plots (Fig. S6e,f) showed an increase in catalyst weight loss after reuse, probably also due to carbon deposition. The carbonaceous matter on the catalyst could have come from the polymerization of xylose with furfural or furfural itself [48]. Elemental and ICP-OES analyses (Table S6) showed that after five rounds of reaction, the content of elemental S and Sn decreased (from 24.1% to 18.9%; from 1.1% to 1.0%), and the carbon content of the recycled catalyst increased (from 17.0% to 21.8%), indicating that carbon deposition occurred on the catalyst during furfural production in association with the TGA data. The above results suggest that the catalyst experiences a minor reduction in catalytic efficiency over five cycles due to the loss of sulfonate and Sn active sites, along with carbon deposition. The effects of the Sn(20)@LS catalyst in comparison with other research employing different reaction conditions are presented in Table 2. The Al-SBA-15(SA) catalyst exhibited a furfural yield of 40.3% after three catalytic cycles, which was restored to 47.2% following regeneration. For the OMC-SO3H catalyst, the furfural yield decreased by 17.7% to 59.0% after three cycles. Upon sulfonation regeneration, its yield recovered to 69.0%, but subsequently declined to 63.9% after an additional cycle. The MC-SnOx-450 catalyst maintained a furfural yield of 48.2% even after five cycles. Notably, SBA-15-(Zr)SO3H suffered a >50% reduction in furfural yield after five reuse cycles. The SO42-/CX-DMSn catalyst showed significant deactivation after six cycles (yield dropped markedly), but recovered to 63% through re-sulfonation. Although the MC-Sn-CNS catalyst underwent sulfonation pretreatment prior to each cycle, its yield progressively decreased to 44.5% after seven cycles. These comparative results demonstrate that our developed catalyst not only features simplified preparation and higher furfural yield, but also exhibits significantly enhanced cycling stability compared to the aforementioned catalytic systems.

Figure 6: Reusability of the Sn(20)@LS catalyst in xylose dehydration reaction. Reaction condition: 180°C for 60 min, xylose (0.1 g), catalyst (0.02 g), water (7.5 mL), CTC (7.5 mL)

To summarize, we have developed a Sn-based catalyst using LS, a by-product of the sulfite pulping process. The as-prepared Sn(20)@LS catalyst exhibits great performance in the xylose dehydration process, resulting in high furfural yield (78.5%) at 180°C for 60 min. Systematic characterization suggests that the synergistic effect of the LA sites (Sn) and the BA sites (-SO3H) in Sn(20)@LS contributes to its excellent catalytic performance in xylose dehydration. The synergistic interaction of these dual acidic sites and the robust organic-inorganic skeleton endow the Sn(20)@LS catalyst with outstanding activity and stability, achieving efficient catalytic conversion in the xylose dehydration reaction. Both solvents and catalysts play a crucial role in furfural preparation. Gromacs simulations verified that CTC did not form hydrogen bonds with xylose, which may reduce xylose consumption. The phase separation is still obvious after the simulation, which indicates that the CTC phase can effectively extract furfural and avoid its side reaction during the whole reaction process. Furthermore, this Sn(20)@LS can be continuously reused for at least five cycles with only a 5.0% decrease in catalytic performance furfural yield. In this study, high value-added catalysts and platform chemicals are prepared from biomass derivatives, which can help to reduce fossil energy dependence and mitigate related environmental issues and is a sustainable chemical conversion process.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their special thanks to State Key Laboratory of Advanced Papermaking and Paper-Based Materials.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22361132543), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Pre-Station) (No. 2023TQ0121), and State Key Laboratory of Pulp and Paper Engineering (No. 2024ZD05).

Author Contributions: Xueqin Liu: Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, methodology, writing—review & editing, writing—original draft. Qingchong Xu: Formal analysis, investigation. Yao Liu: Conceptualization, visualization, writing—review & editing. Junli Ren: Funding acquisition, writing—review & editing, supervision. Lihong Zhao: Writing—review & editing. Ruonan Zhu: Visualization, writing—review & editing, supervision. Xingjie Wang: Visualization, writing—review & editing, supervision. Wei Qi: Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0060/s1.

References

1. McKendry P. Energy production from biomass (part 1overview of biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2002;83(1):37–46. doi:10.1016/S0960-8524(01)00118-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Liu W, Ning C, Li Z, Li X, Wang H, Hou Q. Revealing structural features of lignin macromolecules from microwave-assisted carboxylic acid-based deep eutectic solvent pretreatment. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;194:116342. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ju Y, Zhang K, Gan P, Guo B, Xia H, Zhang L, et al. Functionalized covalent organic frameworks for catalytic conversion of biomass-derived xylan to furfural. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;294(6):139541. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.139541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zhou Q, Ding A, Zhang L, Wang J, Gu J, Wu TY, et al. Furfural production from the lignocellulosic agro-forestry waste by solvolysis method—a technical review. Fuel Process Technol. 2024;255(4):108063. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2024.108063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hu SL, Cheng H, Xu RY, Huang JS, Zhang PJ, Qin JN. Conversion of xylose into furfural over Cr/Mg hydrotalcite catalysts. Mol Catal. 2023;538:113009. doi:10.1016/j.mcat.2023.113009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang T, Li W, An S, Huang F, Li X, Liu J, et al. Efficient transformation of corn stover to furfural using p-hydroxybenzenesulfonic acid-formaldehyde resin solid acid. Bioresour Technol. 2018;264(9):261–7. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.05.081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Xu Z, Wu B, Wu C, Chen Q, Xu K, Shi Z, et al. Antifungal properties and preservation applications of resin acid modified chitosan derivatives. Food Biosci. 2025;66(5):106204. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2025.106204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang Y, Li B, Guan W, Wei Y, Yan C, Meng M, et al. One-pot synthesis of HMF from carbohydrates over acid-base bi-functional carbonaceous catalyst supported on halloysite nanotubes. Cellulose. 2020;27(6):3037–54. doi:10.1007/s10570-020-02994-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li M, Zhang Q, Luo B, Chen C, Wang S, Min D. Lignin-based carbon solid acid catalyst prepared for selectively converting fructose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;145:111920. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu P, Shi S, Wei R, Gao L, Zhang J, Xiao G. Dehydration of xylose and xylan to furfural using P-Zr-SBA-15 catalyst in aqueous or biphasic system. ChemistrySelect. 2023;8(16):e202300902. doi:10.1002/slct.202300902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Toumsri P, Auppahad W, Saknaphawuth S, Pongtawornsakun B, Kaowphong S, Dechtrirat D, et al. Facile preparation protocol of magnetic mesoporous carbon acid catalysts via soft-template self-assembly method and their applications in conversion of xylose into furfural. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2021;379(2209):20200349. doi:10.1098/rsta.2020.0349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Y, Dai Y, Wang T, Li M, Zhu Y, Zhang L. Efficient conversion of xylose to furfural over modified zeolite in the recyclable water/n-butanol system. Fuel Process Technol. 2022;237:107472. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2022.107472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Hu SL, Liang S, Mo LZ, Su HH, Huang JS, Zhang PJ, et al. Conversion of biomass-derived monosaccharide into furfural over Cr-Mg-LDO@bagasse catalysts. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2023;32:101013. doi:10.1016/j.scp.2023.101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li H, Ren J, Zhong L, Sun R, Liang L. Production of furfural from xylose, water-insoluble hemicelluloses and water-soluble fraction of corncob via a tin-loaded montmorillonite solid acid catalyst. Bioresour Technol. 2015;176:242–8. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2014.11.044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ye Q, Li Y, Zhong Z, Wang W, Zheng X, Du H, et al. Investigation on the synthesis of furfural via pyrolysis utilizing metal-loaded solid acid catalysts. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2024;181:106656. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2024.106656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cheng B, Wang X, Lin Q, Zhang X, Meng L, Sun RC, et al. New understandings of the relationship and initial formation mechanism for pseudo-lignin, humins, and acid-induced hydrothermal carbon. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(45):11981–9. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Yang T, Li W, Ogunbiyi AT, An S. Efficient catalytic conversion of corn stover to furfural and 5-hydromethylfurfural using glucosamine hydrochloride derived carbon solid acid in γ-valerolactone. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;161(52):113173. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.113173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Qing Q, Guo Q, Zhou L, Wan Y, Xu Y, Ji H, et al. Catalytic conversion of corncob and corncob pretreatment hydrolysate to furfural in a biphasic system with addition of sodium chloride. Bioresour Technol. 2017;226(2):247–54. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2016.11.118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Xu S, Pan D, Wu Y, Song X, Gao L, Li W, et al. Efficient production of furfural from xylose and wheat straw by bifunctional chromium phosphate catalyst in biphasic systems. Fuel Process Technol. 2018;175:90–6. doi:10.1016/j.fuproc.2018.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li H, Deng A, Ren J, Liu C, Wang W, Peng F, et al. A modified biphasic system for the dehydration of d-xylose into furfural using SO42−/TiO2-ZrO2/La3+ as a solid catalyst. Catal Today. 2014;234:251–6. doi:10.1016/j.cattod.2013.12.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhou N, Zhang C, Cao Y, Zhan J, Fan J, Clark JH, et al. Conversion of xylose into furfural over MC-SnOx and NaCl catalysts in a biphasic system. J Clean Prod. 2021;311:127780. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gong L, Zha J, Pan L, Ma C, He YC. Highly efficient conversion of sunflower stalk-hydrolysate to furfural by sunflower stalk residue-derived carbonaceous solid acid in deep eutectic solvent/organic solvent system. Bioresour Technol. 2022;351(3):126945. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.126945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Gómez Millán G, Hellsten S, King AWT, Pokki JP, Llorca J, Sixta H. A comparative study of water-immiscible organic solvents in the production of furfural from xylose and birch hydrolysate. J Ind Eng Chem. 2019;72(215):354–63. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2018.12.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Song W, Liu H, Zhang J, Sun Y, Peng L. Understanding Hβ zeolite in 1,4-dioxane efficiently converts hemicellulose-related sugars to furfural. ACS Catal. 2022;12(20):12833–44. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c03227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Jia G, Innocent MT, Yu Y, Hu Z, Wang X, Xiang H, et al. Lignin-based carbon fibers: insight into structural evolution from lignin pretreatment, fiber forming, to pre-oxidation and carbonization. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;226(6185):646–59. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Y, Shen X, Hu L, Wu Z, Wang X, Jiang Y. Zirconium-lignin hybrid catalyst for the Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction of biomass-derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(2):2045–61. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02381-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chen XY, Yuan B, Yu FL, Xie CX, Yu ST. Lignin: a potential source of biomass-based catalysts. Prog Chem. 2021;33(2):303–17. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

28. Zhou S, Dai F, Xiang Z, Song T, Liu D, Lu F, et al. Zirconium-lignosulfonate polyphenolic polymer for highly efficient hydrogen transfer of biomass-derived oxygenates under mild conditions. Appl Catal B Environ. 2019;248:31–43. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Konwar LJ, Samikannu A, Mäki-Arvela P, Mikkola JP. Efficient C-C coupling of bio-based furanics and carbonyl compounds to liquid hydrocarbon precursors over lignosulfonate derived acidic carbocatalysts. Catal Sci Technol. 2018;8(9):2449–59. doi:10.1039/C7CY02601C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xu H, Xiong S, Zhao Y, Zhu L, Wang S. Conversion of xylose to furfural catalyzed by carbon-based solid acid prepared from pectin. Energy Fuels. 2021;35(12):9961–9. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c00628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Konwar LJ, Samikannu A, Mäki-Arvela P, Boström D, Mikkola JP. Lignosulfonate-based macro/mesoporous solid protonic acids for acetalization of glycerol to bio-additives. Appl Catal B Environ. 2018;220(7):314–23. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.08.061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Shi Y, Chen P, Chen J, Chen D, Shu H, Jiang H, et al. Hollow Prussian blue analogue/g-C3N4 nanobox for all-solid-state asymmetric supercapacitor. Chem Eng J. 2021;404(6):126284. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chhabra T, Rohilla J, Krishnan V. Nanoarchitectonics of phosphomolybdic acid supported on activated charcoal for selective conversion of furfuryl alcohol and levulinic acid to alkyl levulinates. Mol Catal. 2022;519(7):112135. doi:10.1016/j.mcat.2022.112135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Li H, He J, Riisager A, Saravanamurugan S, Song B, Yang S. Acid-base bifunctional zirconium N-alkyltriphosphate nanohybrid for hydrogen transfer of biomass-derived carboxides. ACS Catal. 2016;6(11):7722–7. doi:10.1021/acscatal.6b02431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xing Y, Yan B, Yuan Z, Sun K. Mesoporous tantalum phosphates: preparation, acidity and catalytic performance for xylose dehydration to produce furfural. RSC Adv. 2016;6(64):59081–90. doi:10.1039/c6ra07830c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Li H, Yang T, Fang Z. Biomass-derived mesoporous Hf-containing hybrid for efficient Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction at low temperatures. Appl Catal B Environ. 2018;227:79–89. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.01.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lin Q, Liao S, Li L, Li W, Yue F, Peng F, et al. Solvent effect on xylose conversion under catalyst-free conditions: insights from molecular dynamics simulation and experiments. Green Chem. 2020;22(2):532–9. doi:10.1039/C9GC03624E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Guo W, Bruining HC, Heeres HJ, Yue J. Insights into the reaction network and kinetics of xylose conversion over combined Lewis/Brønsted acid catalysts in a flow microreactor. Green Chem. 2023;25(15):5878–98. doi:10.1039/D3GC00153A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Gagné OC, Hawthorne FC. Empirical Lewis acid strengths for 135 cations bonded to oxygen. Acta Crystallogr B Struct Sci Cryst Eng Mater. 2017;73(Pt 5):956–61. doi:10.1107/S2052520617010988. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Plumley JA, Evanseck JD. Periodic trends and index of boron LEwis acidity. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113(20):5985–92. doi:10.1021/jp811202c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Song J, Hua M, Huang X, Visa A, Wu T, Fan H, et al. Highly efficient Meerwein-Ponndorf–Verley reductions over a robust zirconium-organoboronic acid hybrid. Green Chem. 2021;23(3):1259–65. doi:10.1039/d0gc04179c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Gürbüz EI, Gallo JMR, Alonso DM, Wettstein SG, Lim WY, Dumesic JA. Conversion of hemicellulose into furfural using solid acid catalysts in γ-valerolactone. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52(4):1270–4. doi:10.1002/anie.201207334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Shen J, Gao R, He YC, Ma C. Efficient synthesis of furfural from waste biomasses by sulfonated crab shell-based solid acid in a sustainable approach. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;202(5):116989. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li Z, Luo Y, Jiang Z, Fang Q, Hu C. The promotion effect of NaCl on the conversion of xylose to furfural. Chin J Chem. 2020;38(2):178–84. doi:10.1002/cjoc.201900433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Luo Y, Li Z, Zuo Y, Su Z, Hu C. A simple two-step method for the selective conversion of hemicellulose in Pubescens to furfural. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2017;5(9):8137–47. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b01766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yang Y, Hu CW, Abu-Omar MM. Synthesis of furfural from xylose, xylan, and biomass using AlCl3 · 6H2O in biphasic media via xylose isomerization to xylulose. ChemSusChem. 2012;5(2):405–10. doi:10.1002/cssc.201100688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Dai Y, Yang S, Wang T, Tang R, Wang Y, Zhang L. High conversion of xylose to furfural over corncob residue-based solid acid catalyst in water-methyl isobutyl ketone. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;180(11):114781. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.114781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Vo ATH, Lee HS, Kim S, Cho JK. Clean and efficient synthesis of furfural from xylose by microwave-assisted biphasic system using bio-based heterogeneous acid catalysts. Clean Technol. 2016;22(4):250–7. doi:10.7464/ksct.2016.22.4.250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Rakngam I, Osakoo N, Wittayakun J, Chanlek N, Pengsawang A, Sosa N, et al. Properties of mesoporous Al-SBA-15 from one-pot hydrothermal synthesis with different aluminium precursors and catalytic performances in xylose conversion to furfural. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021;317:110999. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2021.110999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wang X, Qiu M, Tang Y, Yang J, Shen F, Qi X, et al. Synthesis of sulfonated lignin-derived ordered mesoporous carbon for catalytic production of furfural from xylose. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;187(46):232–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Cabrera-Munguia DA, Gutiérrrez-Alejandre A, Romero-Galarza A, Morales-Martínez TK, Ríos-González LJ, Sifuentes-López J. Function of Brønsted and Lewis acid sites in xylose conversion into furfural. RSC Adv. 2023;13(44):30649–64. doi:10.1039/D3RA05774G. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Cai D, Chen H, Zhang C, Teng X, Li X, Si Z, et al. Carbonized core-shell diatomite for efficient catalytic furfural production from corn cob. J Clean Prod. 2021;283(3):125410. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Zha J, Fan B, He J, He YC, Ma C. Valorization of biomass to furfural by chestnut shell-based solid acid in methyl isobutyl ketone-water-sodium chloride system. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194(5):2021–35. doi:10.1007/s12010-021-03733-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools