Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sustainable Egg Packaging Waste Biocomposites Derived from Recycled Wood Fibers and Fungal Filaments

1 Cellulose laboratory, Latvian State Institute of Wood Chemistry, Riga, LV-1006, Latvia

2 Faculty of Forest and Environmental Sciences, Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies, Jelgava, LV-3001, Latvia

* Corresponding Author: Ilze Irbe. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Eco-friendly Wood-Based Composites: Design, Manufacturing, Properties and Applications – Ⅱ)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(11), 2139-2154. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0107

Received 03 July 2025; Accepted 17 September 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Growing environmental concerns and the need for sustainable alternatives to synthetic materials have led to increased interest in bio-based composites. This study investigates the development and characterization of sustainable egg packaging waste (EPW) biocomposites derived from recycled wood fibers and fungal mycelium filaments as a natural binder. Three formulations were prepared using EPW as the primary substrate, with and without the addition of hemp shives and sawdust as co-substrates. The composites were evaluated for granulometry, density, mechanical strength, hygroscopic behavior, thermal conductivity, and fire performance using cone calorimetry. Biocomposites, composed exclusively of egg packaging waste, exhibited favorable fire resistance, lower total heat release (THR) and total smoke release (TSR), extended time to ignition (TTI), reduced hygroscopicity, and higher flexural strength. Biocomposites, containing hemp shives, demonstrated improved compressive strength and thermal insulation but showed weaker fire resistance. Biocomposites, incorporating sawdust, showed intermediate properties with the longest flameout time (TTF) and highest heat release values. Overall, the results demonstrate that EPW-based biocomposites can be tailored through substrate composition to achieve desirable combinations of mechanical, thermal, and fire-retardant properties, highlighting their potential as sustainable alternatives to conventional synthetic materials in building and packaging applications.Keywords

The slow but persistent transition from synthetic polymers to renewable sources represents an essential strategy of civilization in mitigating environmental degradation, addressing climate change, and promoting a sustainable industrial future. So far, the increasing global reliance on synthetic polymers, particularly fossil fuel-derived plastic materials, has resulted in severe environmental, economic, and health-related consequences [1]. One of the harshest effects is the accumulation of plastic debris in oceans and freshwater systems leading to alarming levels of microplastic contamination, infiltrating food chains and human health systems [2]. Furthermore, the production and disposal of synthetic polymers release large amounts of greenhouse gases, exacerbating climate change [3]. As a response, Europe has prioritized the development and adoption of renewable materials to mitigate these pressing issues while fostering a circular economy. The European Union has taken a leadership role in implementing policies and research initiatives that promote renewable materials as viable substitutes. Legislative frameworks, such as the European Green Deal [4] and the Single-Use Plastics Directive [5], emphasize the reduction of synthetic polymer consumption while encouraging the development of bio-based and biodegradable alternatives from renewable sources. In addition to regulatory actions, scientific and technological advancements have contributed to the feasibility of renewable materials in industrial applications [6,7]. Simultaneously, consumer demand for environmentally friendly products has pressured industries to integrate sustainable materials into their production processes.

Sustainable materials are designed to minimize environmental impact throughout their lifecycle, from production to disposal. They are primarily made from renewable resources, such as plant-based fibers, biodegradable polymers, and recycled materials, ensuring a reduced dependence on finite fossil fuels [8]. Biocomposites are composed of more than one component utilizing the interaction to ensure and improve the properties of the obtained materials [9].

Mycelium biocomposites (MB) are innovative, sustainable materials derived from the fungal hyphae —filamentous, thread-like structures that form the mycelium, the primary vegetative body of a fungus. The majority of fungal species employed in MB belong to white-rot fungi from the phylum Basidiomycota. White-rot fungi are the most efficient and versatile degraders of lignocellulosic biomass, owing to their ability to secrete a broad range of hydrolytic and oxidative enzymes [10], which efficiently mineralize lignin in addition to the wood polysaccharides to CO2 and H2O [11]. These biocomposites are produced through the cultivation of mycelium on organic substrates, mostly lignocellulosic waste, where the fungal network grows and binds the substrate into a solid structure [12]. Due to their biodegradability [13], lightweight properties, and potential for customization, mycelium-based materials have gained attention in various industries, including packaging [14], construction [15,16] and textiles [17] as eco-friendly alternatives to conventional synthetic materials. The unique ability of mycelium to interact with bio-based substrates and form durable, versatile materials position it as a promising solution in the transition toward a more sustainable economy in the field of renewable materials [14].

Various cellulose-containing raw materials can be used as substrates for MB [18]. Cellulose fibers are known as multiple-use recyclable raw material from a renewable primary source, such as wood or other lignocellulosic plants. The current paper fiber recycling rate in Europe is 79.3% which means that most of the used paper and board was recycled, and every fiber completes on average 4.8 recycling cycles [19] while the theoretical number of recycling reaches 25 [20]. Recycled fibers are mainly used to re-create newsprint and packaging materials, as well as to develop innovative composite materials such as reinforced cement materials [21,22], high-density polyethylene (HDPE) composites [23], high-strength foam materials [24], superabsorbents [25], polyurethane elastomer composites [26], polypropylene composites [27]. However, large amounts of secondary fibers are used to form three-dimensional shaped molded fiber products for different applications, such as electronic packaging, specialty items, and food packaging [28,29], which can be further recycled in new packaging or used for more advanced applications, e.g., as a nanocellulose source for active food packaging [30].

According to Eurostat, the EU generates around 84 million tons of packaging waste in a year, with paper and cardboard accounting for over 40% [31]. Since most egg cartons are made from molded fiber derived from recycled paper, they represent a relevant portion of this category. For example, in Germany alone, it is estimated that approximately one billion egg cartons are used each year [32]. Given that a typical fiber carton weighs around 45–50 g, this results in roughly 45,000 to 50,000 t of packaging material annually in just one country. Across Europe, the total volume is undoubtedly higher, making egg packaging an important stream in discussions on waste reduction and material sustainability.

Despite extensive research on recycling and upcycling of molded fiber product waste, no existing studies have specifically addressed its application as a substrate for MB. The proposed study aims to fill the detected gap by developing MB using molded fiber-based egg packaging waste (EPW) as substrate. Although the main component, cellulose fibers, comes from natural and renewable sources, the possible presence of unexpected emerging pollutants [33] synthetic manufacturing additives [29] and other biological and chemical contaminants [34] should be considered when using EPW as a substrate for biocomposites. The study aimed to develop EPW mycelium biocomposites and analyse their mechanical and hygroscopic properties, thermal conductivity, and reaction to fire.

All ingredients used to develop biocomposites were sourced locally. The primary substrate-molded fiber-based EPW was obtained using recycled pulp obtained from SIA “V.L.T.” (Valmiera, Latvia), a manufacturer of molded fiber products. Based on the supplier’s information, the EPW was composed of mixed waste paper (such as journals, books, newspapers, and office paper), cardboard, printing house waste, and waste from egg packaging production and synthetic wet-strength resin Maresin PST 150 (Mare S.p.A, Ossona, Italy).

The co-substrates, hemp shives (HS), were purchased from a local hardware store, while silver birch sawdust (BS) was obtained from a wood processing company (SIA Osukalns, Jekabpils, Latvia). Both materials are readily available and derived from renewable resources, supporting the efficient and sustainable utilization of industrial by-products. Wheat bran (WB) was obtained from a commercial supplier. WB is a cheap and widely used by-product, which is a well-suited growth additive, promoting the lignocellulolytic enzyme production by the majority of basidiomycetes. WB, as an additional supplement, is the primary source of nutrition that supports mycelial biomass increment.

Three different compositions of EPW biocomposites were prepared with primary- and co-substrates, each mixed with 8% WB and 75% distilled water (Table 1).

Substrate particle size distribution and fraction proportions were determined with an AS200 analytical sieve shaker (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany) using vertically arranged sieves of 10, 7, 5, 3, and 1 mm. The mass retained on each sieve after sieving was determined, and its proportion relative to the total sample weight was calculated.

The basidiomycete Trametes versicolor (L.) Lloyd 1920 was initially cultured on Malt Extract Agar (MEA) medium containing 5% malt extract and 3% agar for 14 days at 22 ± 2°C and 70 ± 5% relative humidity (RH) to prepare inoculum for liquid cultivation. Mycelial growth in liquid medium was carried out in a composition containing (per 1000 mL of distilled water): 15.0 g glucose, 3.0 g peptone, 3.0 g yeast extract, 0.8 g NaH2PO4, 0.4 g K2HPO4, and 0.5 g MgSO4, adjusted to pH 6. All reagents were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (Schneldorf, Germany). Cultivation proceeded in a Multitron incubator shaker (Infors HT, Basel, Switzerland) at 27°C and 150 rpm for 14 days.

Following cultivation, mycelial pellets were homogenized using a Waring laboratory blender (Waring Commercial, Torrington, CT, USA) and evenly mixed with sterile substrates in 4 L filter patch bags. Incubation of the inoculated bags was carried out in the dark at 20 ± 2°C and 70 ± 5% RH for 14 days (Fig. 1). Subsequently, the mycelium-substrate mixture was transferred into molds (200 mm × 200 mm × 40 mm) for a second growth phase under the same environmental conditions for an additional 7 days. Upon completion, the EPW biocomposites were removed from the molds followed by drying at 70°C for 24 h to terminate fungal growth and assess moisture content. Moisture content (%) was calculated based on the weight difference between wet and dry samples. The dried panels were then sectioned into different specimen sizes with a bandsaw for further testing.

Figure 1: Development stages of EPW mycelium biocomposites: (A) initial cultivation in filter patch bags; (B) secondary growth in molds; (C) final biocomposite panels

Each specimen was weighed and its length, width, and thickness measured with a digital caliper. Volume and density were subsequently calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2):

where V is volume (cm3), l is length (mm), w is width (mm), and h is height (mm).

where ρ is density (g·cm−3), m is mass (g), and V is volume (cm3).

Compression tests were conducted on five parallel specimens measuring 30 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm using a Zwick/Roell Z010 (ZwickRoell, Ulm, Germany) universal testing machine. The procedure followed a modified ISO 844:2021 [35] standard under controlled laboratory conditions of 23°C and 50% RH. The mechanical load at 10% relative deformation of the specimen was determined. The compression speed corresponded to 10% def/min, and the preload was 2 N. During the test, a force-displacement graph was recorded, from which the compressive modulus of elasticity (E) was determined by drawing a tangent to the steepest part of the curve. Both the compressive strength at 10% deformation (σ10) and E were calculated automatically by the software.

Flexural strength was evaluated on five parallel specimens measuring 170 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm using a Zwick/Roell Z010 (ZwickRoell, Ulm, Germany) universal testing machine. The flexural test was conducted according to ISO 1209-2:2007 [36] under controlled laboratory conditions of 23°C and 50% RH. The load was applied at a rate of 10 mm min−1 with a 1 N pre-load, using a three-point bending configuration with a 150 mm support span. The maximum flexural strength (σfM) and modulus of elasticity (Ef) were calculated automatically by the software.

Thermal conductivity measurements were performed using a Linseis HFM 200 (Linseis GmbH, Selb, Germany) in line with ISO 8301:1991 [37], with the cold and hot plates set at 0°C and 20°C, respectively, yielding a ΔT of 20°C. Three replicate specimens, each measuring 200 mm × 200 mm × 30 mm, were analyzed.

Hygroscopic sorption was measured in accordance with ASTM C1498-01:2017 [38]. Three specimens of each EPW biocomposite composition, measuring 30 mm × 30 mm × 30 mm, were selected and dried in an oven at 50°C to a constant mass. The specimens were then placed in a climate chamber Binder MKF 240 (Binder GmbH, Tuttlingen, Germany) at 23°C, and exposed to a series of test environments with RH increasing from 60% to 90%. The specimens were periodically weighed until equilibrium was reached in each environment. The equilibrium moisture content (%) for each test condition was calculated based on the difference between the constant mass in each environment and the dry weight of the specimen, using Eq. (3).

where u is equilibrium moisture content (%), m is mean mass of the specimens at equilibrium (g), m0 is mean mass of the dry specimens (g).

Subsequently, the adsorption isotherms were constructed.

The cone calorimetry method was used to evaluate the heat release characteristics of EPW biocomposites during combustion. Reaction to fire was assessed using an FTT Dual Cone Calorimeter (Fire Testing Technology Ltd., East Grinstead, UK) following ISO 5660-1:2015 [39]. Four replicate specimens measuring 100 mm × 100 mm × 30 mm were exposed to a constant external heat flux of 35 kW·m−2. The study assessed critical fire performance indicators such as time to ignition, time to flameout, total heat release, peak heat release rate, time to peak heat release rate, total smoke release, and heat release rate.

The statistical analysis was conducted using R 4.2 and the RStudio IDE. Data manipulation and summary statistics (mean and standard deviation) were handled using the dplyr package. Normality of residuals within each substrate group was assessed visually using Quantile-Quantile (Q-Q) plots generated with the qqplotr package. Homogeneity of variances across substrate groups was formally tested using Levene’s test from the rstatix. The significance of differences across groups was tested using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was employed for post-hoc pairwise comparisons between substrate means. Differences with p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The correlation was quantified using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

3.1 Characterization of EPW Mycelium Biocomposites

Moisture is a critical parameter for the successful development of fungal mycelium, as it directly influences the organism’s physiological processes. In the present study, the moisture content of the finalized EPW biocomposites ranged from 56% to 58%, which falls within the optimal range for fungal growth. Decay fungi typically thrive at moisture levels between 40% and 80% [40]. In addition to moisture, the substrate composition plays a pivotal role in the development of mycelium-based composites. The choice of substrate not only supports mycelial growth but also markedly impacts the properties of the produced biocomposite. Depending on the substrate used, the content of polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, and chitin in mycelium may vary, thereby impacting the morphology, density, and functional properties of the resulting biocomposite.

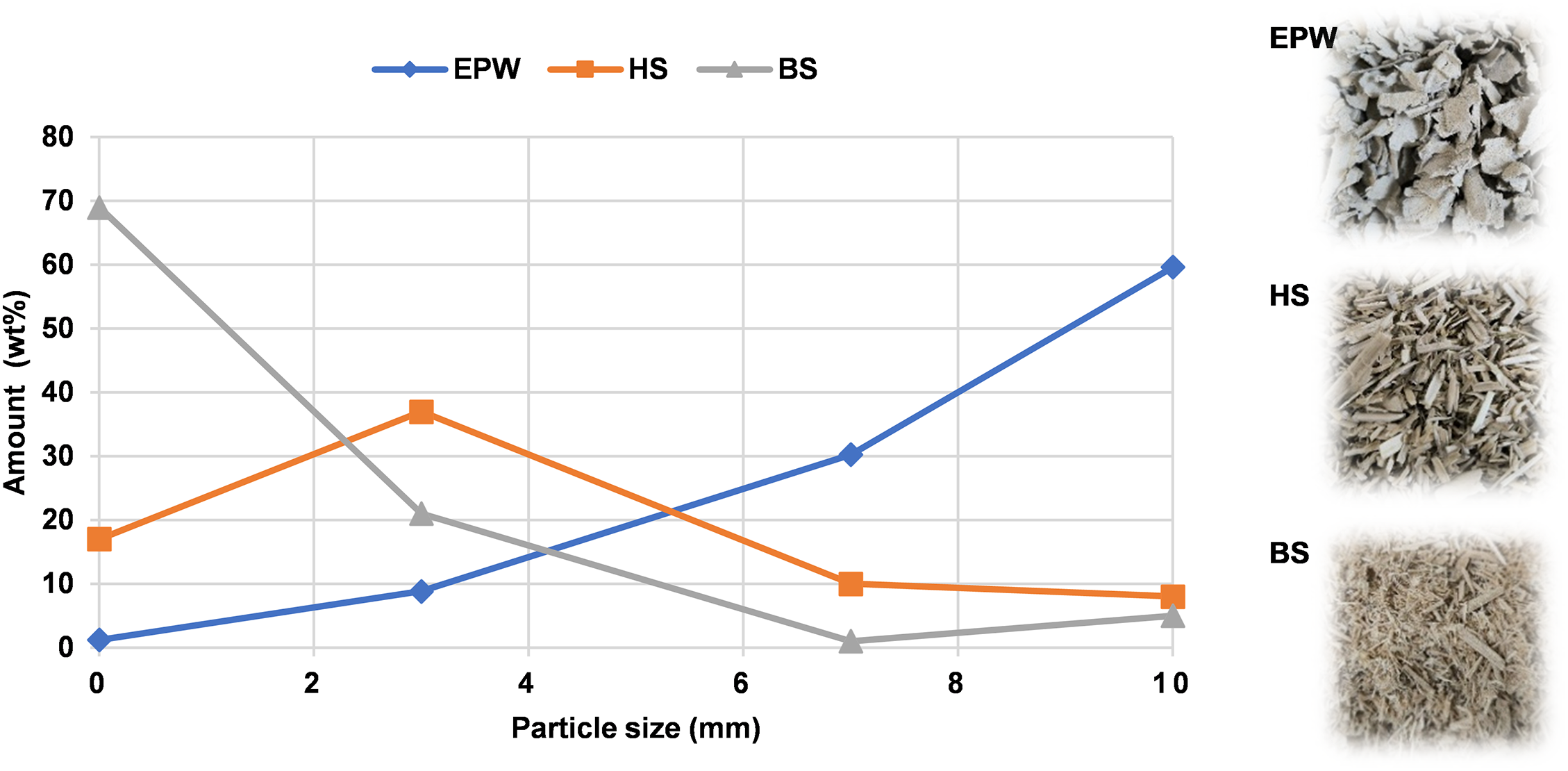

The raw substrates used in EPW biocomposites exhibited distinct particle size distributions (Fig. 2). EPW, present in all formulations, contained 60% coarse particles (≥10 mm). Birch sawdust had the highest proportion of fine particles (<3 mm), comprising 70% of its mass, whereas hemp shives were richer in medium-sized particles (≥3 mm), accounting for 37%. These differences are likely to influence the microstructure and properties of the composites.

Figure 2: Particle size distribution of raw materials used in biocomposites. EPW: egg packaging waste substrate; HS: hemp shive co-substrate; BS: birch sawdust co-substrate

Lignocellulose, a key structural component of wood and non-wood fibers, represents a major renewable resource. The white rot fungus Trametes versicolor degrades cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin simultaneously at relatively uniform rates [41]. Among the combinations (Table 1), EPW1, comprising egg packaging waste and wheat bran, proved effective for composite development. EPW, derived from recycled paper, contains approximately 35% cellulose, 19% lignin, 21% ash, 20% hemicelluloses, and 4.5% extractives [42]. Its high ash content is attributed to non-fibrous impurities such as fillers, pigments, ink residues, and synthetic binders. Nevertheless, these impurities, including wet-strength resins, did not inhibit fungal colonization. EPW2 biocomposites, incorporating 50% hemp shives, demonstrated effective fungal colonization. Hemp shives are composed of approximately 50% cellulose, 20% hemicelluloses, and 10% lignin [43]. EPW3 composites incorporated 50% birch sawdust as a co-substrate, which contains approximately 43% cellulose, 25% hemicelluloses, and 23% lignin [44]. Substrate moisture, particle size, and chemical composition collectively contributed to favorable fungal growth and successful biocomposite formation, as examined in the following sections.

EPW1 biocomposites, composed solely of egg packaging waste, exhibited significantly higher density compared to EPW2 and EPW3 combinations containing hemp and sawdust co-substrates, respectively (Table 2). The density of the composites was closely linked to the substrate composition and particle size distribution. EPW1, comprising 60% coarse particles (>10 mm), yielded the densest composite (0.24 g·cm−3). In contrast, EPW2, incorporating hemp shives with a porous, loose structure, resulted in the lowest density (0.15 g·cm−3). EPW3 composites, combining fine sawdust and coarse EPW particles, showed intermediate density (0.19 g·cm−3). These results align with reported density ranges for mycelium-based composites (0.06–0.30 g·cm−3), where agricultural by-product fillers such as straw yield lower densities than forestry residues like sawdust [45]. Similarly, Teeraphantuvat et al. [46] demonstrated that MB density increases with higher paper waste content, with the highest values (0.32 g·cm−3) observed in sawdust-based composites containing 40% paper waste.

Compressive strength of EPW mycelium biocomposites ranged from 0.18 to 0.32 MPa, while the compressive modulus of elasticity varied between 2.90 and 8.11 MPa (Table 2). EPW2 samples containing hemp exhibited significantly higher compressive strength (p < 0.05) compared to EPW1 and EPW3. Although cellulose fibers possess high strength and stiffness [47], the higher density and predominance of coarse particles in EPW1 likely hindered fungal colonization, reducing compressive strength. Conversely, the porous structure introduced by hemp shives in EPW2 facilitated improved fungal growth, enhancing mechanical performance. Similar trends were observed by Teeraphantuvat et al. [46], who reported decreased compressive strength with 40% paper waste addition in sawdust composites, while a 30% paper waste addition to corn husk composites improved strength. Elsacker et al. [48] demonstrated that MB with dense fungal colonization exhibit higher compressive stiffness, highlighting the significant influence of fungal morphology and substrate interaction on composite properties. Their study reported the highest compressive stiffness (0.51 MPa) in composites with hemp additions, whereas wood-based samples showed the lowest stiffness (0.14 MPa). In the current study, the lower density of hemp-containing composites can be attributed to the inherently low density of hemp particles (0.068 g·cm−3) rather than overall composite density. Fungal growth in the void spaces of hemp composites likely created air pockets supporting sustained hyphal development. Consequently, dense mycelium networks contributed to improved compressive properties, as observed in EPW2 samples.

The highest flexural strength and modulus of elasticity were observed in EPW1 biocomposites, reaching 0.95 and 26 MPa, respectively (p < 0.05) (Table 2). EPW3 exhibited significantly higher flexural strength (0.89 MPa) than EPW2 (0.63 MPa). Both co-substrates containing composites (EPW2 and EPW3) showed similar flexural moduli (~18 MPa), which were significantly lower than that of EPW1. Flexural properties positively correlated with density, as the denser EPW1 composite also demonstrated superior mechanical performance. Similar trends were reported by Appels et al. [49], where MB with higher density (beech sawdust) had higher flexural strength (0.26 MPa) and modulus (9 MPa), compared to lower-density rapeseed straw-based composites (0.22, 3 MPa). In contrast, Teeraphantuvat et al. [46] found that adding 40% paper waste reduced flexural strength in corn husk and sawdust biocomposites. This and previous studies [50,51] emphasize that the mechanical performance of mycelium-based materials is influenced by multiple factors, including fungal species, substrate type, growth conditions, and compaction. Therefore, direct comparisons across studies should be approached with caution, and results interpreted within the context of specific experimental setups.

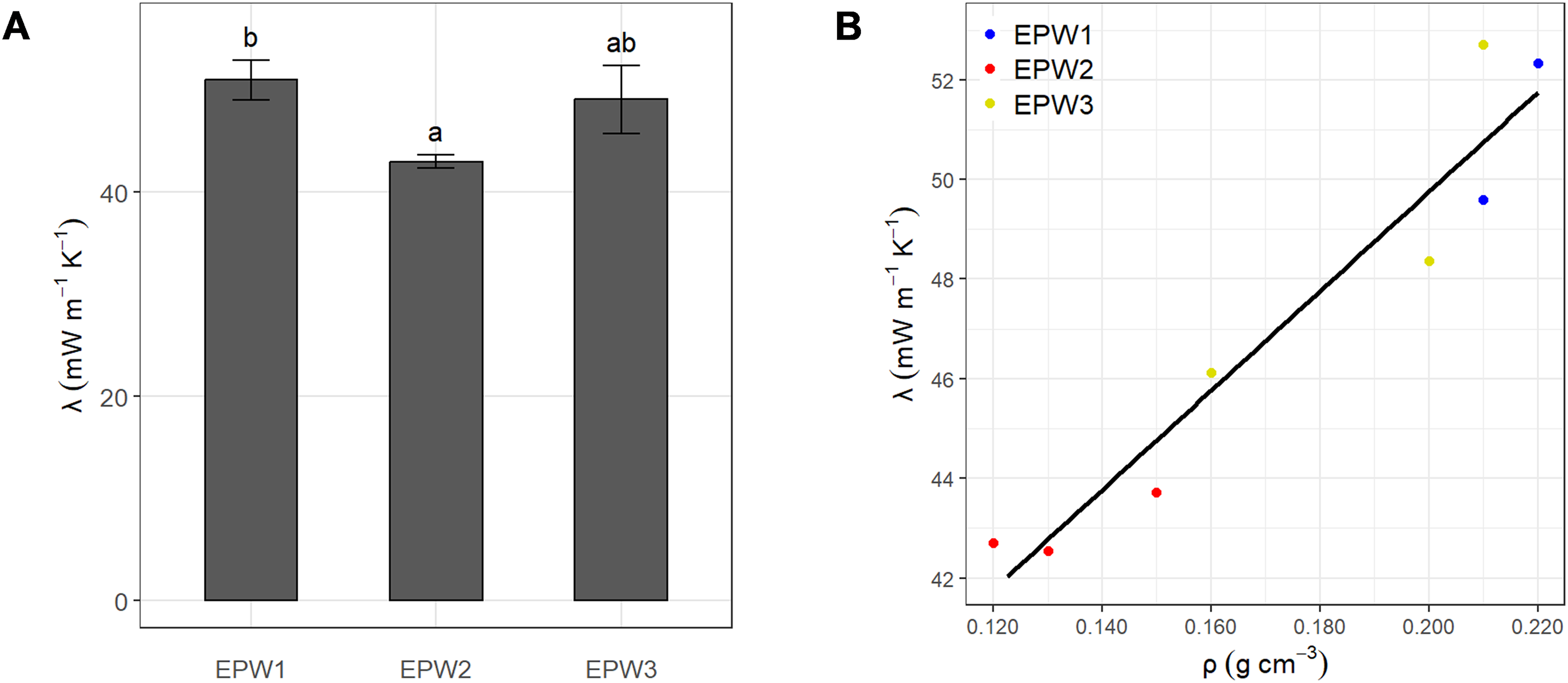

Average thermal conductivity (λ) values ranged from 43 to 51 mW·m−1·K−1, with the lowest observed in the hemp-containing EPW2 composite (Fig. 3A). Composition of biocomposites significantly affected thermal conductivity (p = 0.024), with λ for EPW2 significantly lower than EPW1 (p = 0.029) and marginally lower than EPW3 (p = 0.052). The addition of hemp shives or birch sawdust influenced the thermal conductivity of the biocomposites due to differences in microstructure and particle size of these co-substrates. Hemp shives contain a relatively high proportion of hollow-core structures, which increase porosity and contribute to lower thermal conductivity by limiting heat transfer. In contrast, birch sawdust exhibits a denser and more compact microstructure, with approximately twice the bulk density (~200 kg/m3) of hemp. Moreover, a finer sawdust particle size may enhance the number of contact points within the matrix, thereby increasing thermal conductivity.

Figure 3: Thermal conductivity (A) and its correlation with density (B) of EPW mycelium biocomposites. EPW: egg packaging waste; Compositions 1–3 correspond to different substrate formulations. Different letters (a–b) indicate statistically significant differences between composites (p = 0.029)

A strong positive correlation was found between thermal conductivity and composite density (R = 0.959, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3B). EPW2, having the lowest density, exhibited the lowest λ, while EPW1 showed the highest values for both density and conductivity. Thermal conductivity in porous biocomposites is influenced by the balance between solid and air phases. Lower-density materials tend to have a higher air content and more void spaces, which reduce the overall thermal conductivity due to air’s poor ability to conduct heat.

Thermal conductivity values reported for mycelium-based composites in the literature range from 40 to 180 mW·m−1·K−1. Elsacker et al. [48] evaluated MB made from flax, hemp, and straw, finding the lowest thermal conductivity (40 mW·m−1·K−1) and moderate density (0.10 g·cm−3) in hemp-based composites. In contrast, flax-based composites showed poorer insulation (60 mW·m−1·K−1) due to higher density (0.14 g·cm−3). Schritt et al. [52] developed T. versicolor MB using beech sawdust and spent mushroom substrate, reporting thermal conductivities of 63–77 mW·m−1·K−1 at densities of 0.19–0.20 g·cm−3. These values exceed those of our birch sawdust-based EPW3 composite, which demonstrated a lower thermal conductivity of 49 mW·m−1·K−1. Holt et al. [53] developed biocomposites using Ganoderma sp. and processed cotton biomass, reporting high λ values of 100–180 mW·m−1·K−1, more than twice the highest conductivity observed in the present study. Wimmers et al. [54] tested five tree species and nine fungal strains, yielding thermal conductivities of 51–55 mW·m−1·K−1, slightly exceeding our results.

The λ values of EPW biocomposites are comparable to those of conventional insulation materials such as expanded polystyrene (37 mW·m−1·K−1), glass wool (36 mW·m−1·K−1), and wood fiber wool (50 mW·m−1·K−1) [55]. Given their competitive thermal performance, coupled with potentially lower production costs and embodied energy, mycelium-based insulation panels present a promising sustainable alternative to traditional materials.

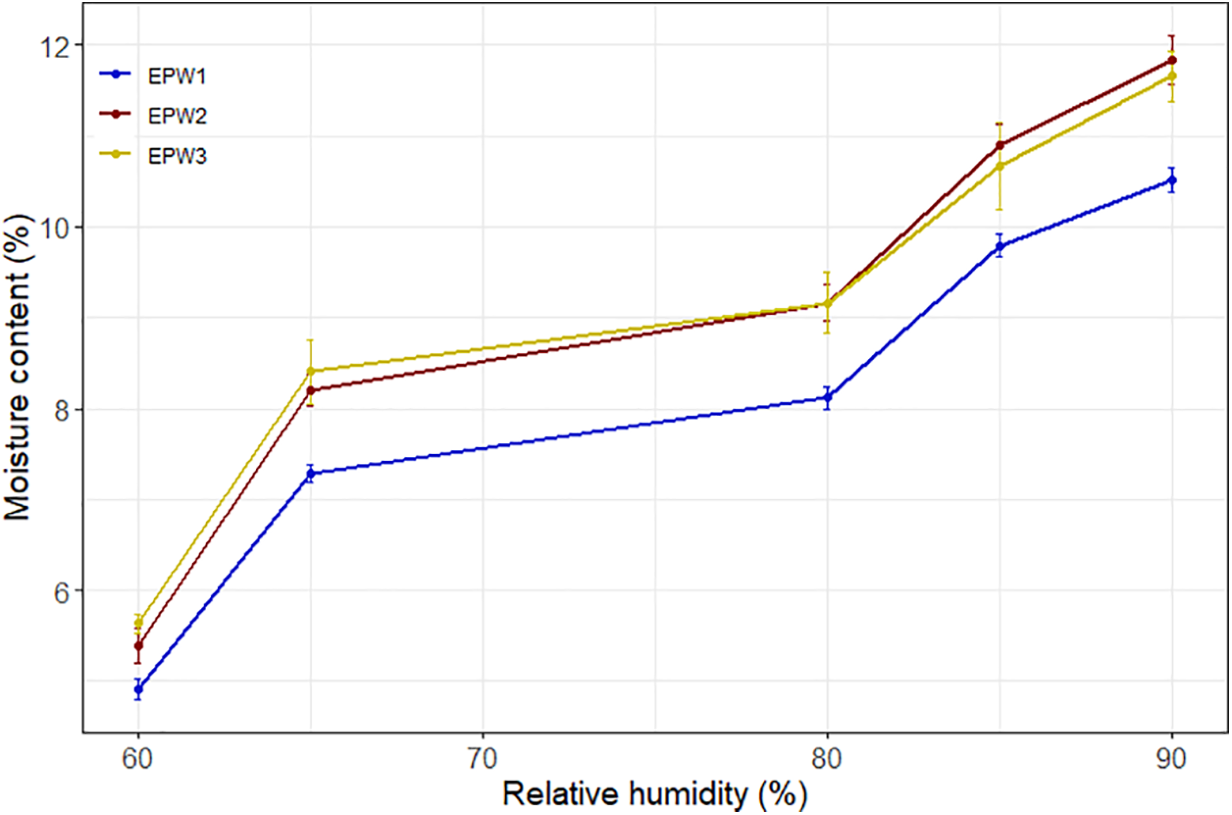

Moisture content of the EPW biocomposites increased significantly with rising relative humidity (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4). EPW1 showed the lowest moisture uptake, ranging from 4.9% at 60% RH to 10.5% at 90% RH. In contrast, EPW2 and EPW3 exhibited higher values, increasing from 5.4%–5.6% to 11.7%–11.8%, respectively. Moisture content in EPW1 was significantly lower than in EPW2 and EPW3 (p = 0.002).

Figure 4: Hygroscopic sorption isotherms of EPW mycelium biocomposites. EPW: egg packaging waste; Compositions 1–3 correspond to different substrate formulations. Error bars indicate SD

RH is a critical yet often underestimated environmental factor affecting composite material performance. Moisture content of composite materials varies significantly with RH, temperature, and material composition, influencing long-term durability. It is essential that newly developed materials contribute to maintaining indoor relative humidity within the optimal range of 40%–60% [56]. Mold development typically occurs at RH levels between 80%–95%, depending on temperature, exposure time, and material surface properties [57]. While some materials tolerate high RH without mold formation, others are susceptible at RH as low as 75% [58]. Water absorption studies show that solid wood absorbs the least moisture, followed by plywood, with wood composites showing the highest uptake [59]. Furniture and building industry panels such as medium-density fibreboard (MDF), particleboard, and oriented strand board (OSB) can reach 15%–20% moisture content at 97% RH [60]. In contrast, EPW biocomposites demonstrated superior performance, maintaining moisture content below 12% at 90% RH, highlighting their competitiveness as a sustainable and moisture-resistant alternative.

The cone calorimeter is a widely accepted method for evaluating the fire performance of polymer-based materials. Parameters such as moisture content, physical characteristics, and chemical composition significantly influence the flammability [61]. In this study, the fire behavior of EPW biocomposites was characterized by measuring time to ignition (TTI), time to flameout (TTF), total heat release (THR), peak heat release rate (pHRR), time to peak heat release rate (TTP), total smoke release (TSR) (Table 3), and heat release rate (HRR) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Heat release rate (HRR) curves of EPW mycelium biocomposites. EPW: egg packaging waste; Compositions 1–3 correspond to different substrate formulations

EPW1 samples exhibited the highest average time to ignition (TTI) at 16 s, significantly longer than EPW2 (10 s), but not statistically different from EPW3 (12 s) (Table 3). EPW2 showed the shortest TTI among all samples, likely due to the incorporation of hemp shives into the substrate. Hemp shives are known to exhibit low TTI values (~11 s), consistent with the present findings, and contribute minimally to fire conditions when used in composite materials such as hempcrete [62].

The thermal degradation behavior of lignocellulosic components also influences ignition characteristics. Hemicellulose decomposes at 250°C–370°C, cellulose undergoes depolymerization above 300°C, and lignin exhibits gradual degradation with major mass loss occurring above 380°C [63,64]. The higher ash content in paper waste [42], and consequently, in EPW1 compared to the hemp (EPW2) and sawdust (EPW3) co-substrates, may contribute to delayed ignition. Additionally, the presence of mycelium may enhance fire resistance. Mycelium has been reported to exhibit flame-retardant behavior, including high char residue and water vapor release during combustion, offering potential as a sustainable, fire-safer alternative to synthetic polymers [65].

Time to flameout (TTF) is a critical parameter in assessing the fire safety of materials, particularly in construction, where shorter flame durations reduce the risk of fire rapid propagation. In this study, TTF values for EPW mycelium biocomposites ranged from 595 to 963 s (Table 3). EPW3 samples, containing sawdust as a co-substrate, exhibited the longest flameout times, whereas EPW1 samples showed the shortest TTF. For comparison, sansevieria fiber-reinforced polyester composites have reported TTF values of 1883 s [66], while silicon-based composites composed of ash and silicone rubber display TTFs between 417 and 705 s [67]. The variation in TTF observed here is strongly dependent on the substrate composition. EPW1, consisting solely of egg packaging waste, demonstrates flameout times comparable to silicon composites but approximately three times lower than sansevieria polyester composites. Moreover, rigid polyurethane/polyisocyanurate foams demonstrate substantially shorter TTFs, between 69 and 175 s [68], emphasizing the comparatively enhanced fire resistance of the EPW biocomposites studied.

Lower heat release properties correlate with improved flame resistance of materials. Among the tested samples, the EPW1 biocomposite, with egg packaging waste as the primary substrate, exhibited the lowest total heat release (THR) of ~12 MJ·m−2. MJ (Table 3). The inclusion of hemp (EPW2) and sawdust (EPW3) co-substrates increased the THR values, with EPW3 reaching 26 MJ·m−2. This may be attributed to the lower density of the co-substrate-containing composites. The influence of density on fire behavior has also been reported for bio-aggregate composites [69], where specimens with the lowest gypsum content exhibited inferior fire resistance compared to their denser counterparts. Similar THR values, ranging from 10 to 20 MJ·m−2, were observed for lignocellulosic biomass insulation materials, which are lower than those of certain wood composites [70]. Elevated THR in co-substrate-containing EPW composites indicates a greater potential for heat release, thereby increasing fire hazard severity.

Heat release rate (HRR) is a critical metric for evaluating fire risk, as higher HRR promotes flame spread. Peak heat release rate (pHRR) is particularly indicative of fire performance. EPW1 showed the lowest pHRR of 112 kW·m−2 at 28 s time to peak (TTP), whereas EPW3 exhibited the highest pHRR of 165 kW·m−2 at 23 s. EPW2 also displayed a higher pHRR than EPW1 (Table 3; Fig. 5). The addition of hemp or sawdust co-substrates increased the heat release and accelerated TTP. Shewalul et al. [62] reported that incorporation of hemp shives in hemp blocks reduced pHRR significantly, from 189 s to 23 kW·m−2, highlighting the influence of substrate composition. In comparison, sansevieria polyester composites demonstrated a markedly higher pHRR of 459 kW·m−2 [66], underscoring the relatively favorable fire performance of the EPW biocomposites examined in this study.

To ensure favorable fire-retardant performance, materials should exhibit minimal total smoke release (TSR) during combustion. Smoke contains fine soot particles and toxic vapors that can irritate the eyes and respiratory tract, while also reducing visibility and obstructing evacuation routes during fire events, thereby increasing life safety risks. In this study, TSR values for EPW biocomposites ranged from 5 m2·m−2 (EPW1 and EPW3) to 12 m2·m−2 (EPW2) (Table 3). Although EPW2 exhibited the highest average smoke release, the differences among compositions were not statistically significant. By contrast, rigid polyurethane foam has reported TSR values between 400 and 990 m2·m−2 [71], which corresponds to values nearly 100 times higher than those of EPW composites. Thus, EPW biocomposites represent a promising bio-based alternative to conventional synthetic materials, offering substantially lower smoke toxicity during combustion.

The properties of EPW mycelium biocomposites can be effectively tailored through the selection of both primary and co-substrates. The inclusion of hemp and sawdust co-substrates significantly influenced the mechanical, thermal, and fire performance characteristics.

EPW1 biocomposites, composed solely of egg packaging waste, exhibited a balanced combination of mechanical, thermal, and fire performance properties relative to EPW2 and EPW3 combinations containing hemp or sawdust co-substrates. Enhanced fire performance of EPW1, characterized by prolonged time to ignition, lower total heat release, and reduced smoke emission, highlights its potential as a fire-retardant alternative to conventional synthetic materials for building insulation. EPW1 composites, with the highest density and flexural strength, are appropriate for structural or load-bearing applications. Lower hygroscopicity of EPW1 contributes to the suitability of the composites in environments with variable moisture exposure, such as packaging and interior panels in humid climates. Among the three formulations, EPW2 with hemp shives exhibited enhanced compressive strength, the lowest density, and thermal conductivity, making it the most suitable for thermal insulation or packaging applications where lightweight materials are preferred. EPW3 showed intermediate values and may serve as a versatile option for general-purpose biocomposites. This formulation-dependent property variation demonstrates the potential to tailor EPW mycelium composites for specific end uses through controlled substrate processing. Egg packaging waste can be considered a promising substrate for inclusion in mycelium-based composites, as it did not inhibit fungal colonization despite the presence of a high content of non-fibrous impurities and synthetic wet-strength resins. Supplementation with wheat bran was essential for successful fungal colonization of the EPW substrate.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the Latvian State Institute of Wood Chemistry for support by providing scientific infrastructure for this research. We are grateful to Dr. Mikelis Kirpluks for the processing of cone calorimetry data.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Latvian Research Council FLPP project No. lzp-2023/1-0633 “Innovative mycelium biocomposites (MB) from plant residual biomass with enhanced properties for sustainable solutions”.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ilze Irbe, Inese Filipova; methodology, Laura Andze; investigation, Ilze Irbe; resources, Inese Filipova, Laura Andze; writing—original draft preparation, Ilze Irbe; writing—review and editing, Inese Filipova, Laura Andze; project administration, Inese Filipova; funding acquisition, Ilze Irbe. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The article contains no studies involving human or animal subjects.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Seewoo BJ, Wong EVS, Mulders YR, Goodes LM, Eroglu E, Brunner M, et al. Impacts associated with the plastic polymers polycarbonate, polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride, and polybutadiene across their life cycle: a review. Heliyon. 2024;10(12):e32912. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zheng Y, Hernando MD, Barceló D, Wang C, Li H. Climate change exacerbates microplastic pollution: environmental behavior and human health risks. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 2025;45:100608. doi:10.1016/j.coesh.2025.100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Stoett P, Scrich VM, Elliff CI, Andrade MM, Grilli NDM, Turra A. Global plastic pollution, sustainable development, and plastic justice. World Dev. 2024;184:106756. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2024.106756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. The European green deal [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 May 12]. Available from: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019–2024/european-green-deal_en. [Google Scholar]

5. European Parliament. Directive (EU) 2019/904 [Internet]. Joensuu, Finland: University of Eastern Finland Law School. 2019 [cited 2025 May 18]. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/eudr/2019/904. [Google Scholar]

6. Luo T, Hu Y, Zhang M, Jia P, Zhou Y. Recent advances of sustainable and recyclable polymer materials from renewable resources. RCM. 2024;4(2):100085. doi:10.1016/j.recm.2024.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Mohammed M, Oleiwi JK, Mohammed AM, Jawad AJAM, Osman AF, Adam T, et al. A review on the advancement of renewable natural fiber hybrid composites: prospects, challenges, and industrial applications. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(7):1237–90. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.051201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Vinod A, Sanjay MR, Suchart S, Jyotishkumar P. Renewable and sustainable biobased materials: an assessment on biofibers, biofilms, biopolymers and biocomposites. J Clean Prod. 2020;258:120978. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Correa JP, Montalvo-Navarrete JM, Hidalgo-Salazar MA. Carbon footprint considerations for biocomposite materials for sustainable products: a review. J Clean Prod. 2019;208:785–94. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.10.099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Baldrian P, Valásková V. Degradation of cellulose by basidiomycetous fungi. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2008;32(3):501–21. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00106.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Daniel G. Fungal degradation of wood cell walls. In: Kim YS, Funada R, Singh AP, editors. Secondary xylem biology. Charts 8. Boston, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2016. p. 131–67. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-802185-9.00008-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Camilleri E, Narayan S, Lingam D, Blundell R. Mycelium-based composites: an updated comprehensive overview. Biotechnol Adv. 2025;79:108517. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2025.108517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Irbe I, Loris GD, Filipova I, Andze L, Skute M. Characterization of self-growing biomaterials made of fungal mycelium and various lignocellulose-containing ingredients. Materials. 2022;15(21):7608. doi:10.3390/ma15217608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jo C, Zhang J, Tam JM, Church GM, Khalil AS, Segrè D, et al. Unlocking the magic in mycelium: using synthetic biology to optimize filamentous fungi for biomanufacturing and sustainability. Mater Today Bio. 2023;19:100560. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Alaneme KK, Anaele JU, Oke TM, Kareem SA, Adediran M, Ajibuwa OA, et al. Mycelium based composites: a review of their bio-fabrication procedures, material properties and potential for green building and construction applications. Alex Eng J. 2023;83:234–50. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2023.10.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jin Y, De G, Wilson N, Qin Z, Dong B. Towards carbon-neutral built environment: a critical review of mycelium-based composites. Energy Built Environ. Forthcoming 2025. doi:10.1016/j.enbenv.2025.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Amobonye A, Lalung J, Awasthi MK, Pillai S. Fungal mycelium as leather alternative: a sustainable biogenic material for the fashion industry. SM&T. 2023;38:e00724. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2023.e00724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Qiu Y, Hausner G, Yuan Q. Investigation of hybrid substrates of waste paper and hemp hurds for mycelium-based materials production. Mater Today Sustain. 2025;30:101101. doi:10.1016/j.mtsust.2025.101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Monitoring Report 2023, European Declaration on Paper Recycling 2021–2030 [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://austropapier.at/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/23-00-EPRC-Recycling-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

20. Eckhart R. Recyclability of cartonboard and carton 2021 [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.procarton.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/25-Loops-Study-English-v3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

21. Adediran AA, Oladele IO, Omotosho TF, Adesina OS, Olayanju TMA, Fasemoyin IM. Water absorption, flexural properties and morphological characterization of chicken feather fiber-wood sawdust hybrid reinforced waste paper-cement bio-composites. Mater Today. 2021;44:2843–8. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ashori A, Tabarsa T, Valizadeh I. Fiber reinforced cement boards made from recycled newsprint paper. Mater Sci Eng A. 2011;528(25):7801–4. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2011.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang X, Di J, Xu L, Lv J, Duan J, Zhu X, et al. High-value utilization method of digital printing waste paper fibers-Co-blending filled HDPE composites and performance improvement. Polym Test. 2022;116:107790. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2022.107790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang X, Li N, Chen C, Zhou Z, Li K. Characteristics of natural corn starch/waste paper fiber composite foams treated by organic-inorganic hybrid hydrophobic coating technology. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;281:136432. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Sang W, Cui S, Wang X, Liu B, Li X, Sun K, et al. Preparation and properties of multifunctional polyaspartic acid/waste paper fiber-based superabsorbent composites. J Environ Chem Eng. 2022;10(5):108405. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2022.108405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lei W, Fang C, Zhou X, Li Y, Pu M. Polyurethane elastomer composites reinforced with waste natural cellulosic fibers from office paper in thermal properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;197:385–94. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Grubb CA, Keffer DJ, Webb CD, Kardos M, Mainka H, Harper DP. Paper fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites from nonwoven preforms: a study on compression molding optimization from a manufacturing perspective. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2024;185:108339. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2024.108339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Debnath M, Sarder R, Pal L, Hubbe MA. Molded pulp products for sustainable packaging: production rate challenges and product opportunities. BioResources. 2022;17(2):3810–70. doi:10.15376/biores.17.2.Debnath. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Didone M, Saxena P, Brilhuis-Meijer E, Tosello G, Bissacco G, Mcaloone TC, et al. Moulded pulp manufacturing: overview and prospects for the process technology. Packag Technol Sci. 2017;30(6):231–49. doi:10.1002/pts.2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Raghav GR, Nagarajan KJ, Palaninatharaja M, Karthic M, Kumar RA, Ganesh MA. Reuse of used paper egg carton boxes as a source to produce hybrid AgNPs-carboxyl nanocellulose through bio-synthesis and its application in active food packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;249:126119. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Eurostat. Packaging waste statistics. Eurostat Statistics Explained [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Packaging_waste_statistics. [Google Scholar]

32. Presseschleuder. Egg packaging: Germany uses over 1 billion cartons annually [Internet]. Presseschleuder. [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.presseschleuder.com/2025/03/egg-packaging/. [Google Scholar]

33. Mofokeng NN, Madikizela LM, Tiggelman I, Chimuka L. Emerging contaminants as unintentional substances in paper and board: a case of unexpected pharmaceuticals detection in the paper recycling chain. J Hazard Mater. 2024;472:134419. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.134419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Semple KE, Zhou C, Rojas OJ, Nkeuwa WN, Dai C. Moulded pulp fibers for disposable food packaging: a state-of-the-art review. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2022;33:100908. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. ISO 844:2021. Rigid cellular plastics—determination of compression properties. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standartization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

36. ISO 1209-2:2007. Rigid cellular plastics—determination of flexural properties. Part 2: determination of flexural strength and apparent flexural modulus of elasticity. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standartization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

37. ISO 8301:1991. Thermal insulation—determination of steady-state thermal resistance and related properties—heat flow meter apparatus. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standartization; 1991. [Google Scholar]

38. ASTM C1498-01:2001. Standard test method for hygroscopic sorption isotherms of building materials. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: ASTM International; 2001. [Google Scholar]

39. ISO 5660-1:2015. Reaction-to-fire tests—heat release, smoke production and mass loss rate. Part 1: heat release rate (cone calorimeter method) and smoke production rate (dynamic measurement). Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standartization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

40. Schmidt O. Wood and tree fungi: biology, damage, protection, and use. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

41. Goodell B, Nicholas DD, Schultz TP. Wood deterioration and preservation. Washington, DC, USA: American Chemical Society; 2003. [Google Scholar]

42. Souza AG, Rocha DB, Kano FS, Rosa D. Valorization of industrial paper waste by isolating cellulose nanostructures with different pretreatment methods. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2019;143:133–42. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.12.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Diakité M-S, Lequart V, Hérisson A, Chenot É., Potel S, Leblanc N, et al. Processing hemp shiv particles for building applications: alkaline extraction for concrete and hot water treatment for binderless particle board. Appl Sci. 2024;14(19):8815. doi:10.3390/app14198815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lachowicz H, Wróblewska H, Sajdak M, Komorowicz M, Wojtan R. The chemical composition of silver birch (Betula pendula Roth.) wood in Poland depending on forest stand location and forest habitat type. Cellulose. 2019;26(5):3047–67. doi:10.1007/s10570-019-02306-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Jones M, Mautner A, Luenco S, Bismarck A, John S. Engineered mycelium composite construction materials from fungal biorefineries: a critical review. Mater Des. 2020;187:108397. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Teeraphantuvat T, Jatuwong K, Jinanukul P, Thamjaree W, Lumyong S, Aiduang W. Improving the physical and mechanical properties of mycelium-based green composites using paper waste. Polym. 2024;16(2):262. doi:10.3390/polym16020262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Jakob M, Mahendran AR, Gindl-Altmutter W, Bliem P, Konnerth J, Müller U, et al. The strength and stiffness of oriented wood and cellulose-fibre materials: a review. Prog Mater Sci. 2022;125:100916. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2021.100916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Elsacker E, Vandelook S, Brancart J, Peeters E, De Laet L. Mechanical, physical and chemical characterisation of mycelium-based composites with different types of lignocellulosic substrates. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0213954. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Appels FVW, Camere S, Montalti M, Karana E, Jansen KMB, Dijksterhuis J, et al. Fabrication factors influencing mechanical, moisture- and water-related properties of mycelium-based composites. Mater Des. 2019;161:64–71. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2018.11.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Haneef M, Ceseracciu L, Canale C, Bayer IS, Heredia-Guerrero JA, Athanassiou A. Advanced materials from fungal mycelium: fabrication and tuning of physical properties. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):41292. doi:10.1038/srep41292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Antinori ME, Contardi M, Suarato G, Armirotti A, Bertorelli R, Mancini G, et al. Advanced mycelium materials as potential self-growing biomedical scaffolds. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):12630. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-91572-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Schritt H, Vidi S, Pleissner D. Spent mushroom substrate and sawdust to produce mycelium-based thermal insulation composites. J Clean Prod. 2021;313:127910. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.127910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Holt GA, Mcintyre G, Flagg D, Bayer E, Wanjura JD, Pelletier MG. Fungal mycelium and cotton plant materials in the manufacture of biodegradable molded packaging material: evaluation study of select blends of cotton byproducts. J Biobased Mater Bioenergy. 2012;6(4):431–9. doi:10.1166/jbmb.2012.1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Wimmers G, Klick J, Tackaberry L, Zwiesigk C, Egger K, Massicotte H. Fundamental studies for designing insulation panels from wood shavings and filamentous fungi. BioResources. 2019;14(3):5506–20. doi:10.15376/biores.14.3.5506-5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Kunič R. Forest-based bioproducts used for construction and its impact on the environmental performance of a building in the whole life cycle. In: Kutnar A, Muthu SS, editors. Environmental impacts of traditional and innovative forest-based bioproducts. Singapore: Springer; 2016. p. 173–204. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-0655-5_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Sterling EM, Arundel A, Sterling TD. Criteria for human exposure to humidity in occupied buildings. ASHRAE Trans. 1985;91:61. [Google Scholar]

57. Viitanen H, Vinha J, Salminen K, Ojanen T, Peuhkuri R, Paajanen L, et al. Moisture and bio-deterioration risk of building materials and structures. J Build Phys. 2010;33(3):201–24. doi:10.1177/1744259109343511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Johansson P, Ekstrand-Tobin A, Svensson T, Bok G. Laboratory study to determine the critical moisture level for mould growth on building materials. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2012;73:23–32. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.05.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Yang DQ. Water absorption of various building materials and mold growth. No. 08-10657. In: Proceedings of the IRG/WP 39th Annual Meeting; 2008 May 25–29; Istanbul, Turkey. [Google Scholar]

60. Sala CM, Robles E, Gumowska A, Wronka A, Kowaluk G. Influence of moisture content on the mechanical properties of selected wood-based composites. BioResources. 2020;15(3):5503–13. doi:10.15376/biores.15.3.5503-5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Soni RK, Teotia M, Sharma A. Cone calorimetry in fire-resistant materials. In: Rivera Armenta JL, Flores-Hernández CG, editors. Applications of calorimetry. Rijeka, Croatia: IntechOpen; 2022. [Google Scholar]

62. Shewalul YW, Quiroz NF, Streicher D, Walls R. Fire behavior of hemp blocks: a biomass-based construction material. J Build Eng. 2023;80:108147. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2023.108147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Stevulova N, Cigasova J, Estokova A, Terpakova E, Geffert A, Kacik F, et al. Properties characterization of chemically modified hemp hurds. Materials. 2014;7(12):8131–50. doi:10.3390/ma7128131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Dorez G, Ferry L, Sonnier R, Taguet A, Lopez-Cuesta JM. Effect of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin contents on pyrolysis and combustion of natural fibers. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2014;107:323–31. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2014.03.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Jones M, Bhat T, Kandare E, Thomas A, Joseph P, Dekiwadia C, et al. Thermal degradation and fire properties of fungal mycelium and mycelium—biomass composite materials. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):17583. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-36032-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Ramanaiah K, Ratna Prasad AV, Hema Chandra Reddy K. Mechanical, thermophysical and fire properties of sansevieria fiber-reinforced polyester composites. Mater Des. 2013;49:986–91. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2013.02.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Kim Y, Hwang S, Choi J, Lee J, Yu K, Baeck S-H, et al. Valorization of fly ash as a harmless flame retardant via carbonation treatment for enhanced fire-proofing performance and mechanical properties of silicone composites. J Hazard Mater. 2021;404:124202. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Borowicz M, Paciorek-Sadowska J, Lubczak J, Czupryński B. Biodegradable, flame-retardant, and bio-based rigid polyurethane/polyisocyanurate foams for thermal insulation application. Polymers. 2019;11(11):1816. doi:10.3390/polym11111816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Bumanis G, Andzs M, Sinka M, Bajare D. Fire resistance of phosphogypsum- and hemp-based bio-aggregate composite with variable amount of binder. J Compos Sci. 2023;7(3):118. doi:10.3390/jcs7030118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Andzs M, Tupciauskas R, Berzins A, Pavlovics G, Rizikovs J, Milbreta U, et al. Flammability of plant-based loose-fill thermal insulation: insights from wheat straw, corn stalk, and water reed. Fibers. 2025;13(3):24. doi:10.3390/fib13030024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Kairytė A, Kirpluks M, Ivdre A, Cabulis U, Vaitkus S, Pundienė I. Cleaner production of polyurethane foam: replacement of conventional raw materials, assessment of fire resistance and environmental impact. J Clean Prod. 2018;183:760–71. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools