Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Recent Advancements in Biochar Functionalization from Crop Residues for a Green Future

1 Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering Technology, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2092, South Africa

2 Center for Industrial Biotechnology Research, Siksha ‘O’ Anusandhan (SOA) Deemed to be University, PO: Khandagiri, Bhubaneswar, 751030, India

* Corresponding Author: Omojola Awogbemi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Biochar Based Materials for a Green Future)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(11), 2191-2233. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0112

Received 13 June 2025; Accepted 08 August 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Increased human and industrial activities have exacerbated the release of toxic materials and acute environmental pollution in recent times. Biochar, a carbon-rich material produced from biomass, is gaining momentum as a versatile material for attaining a sustainable environment. The study reviews the application of functionalized biochar for energy storage, environmental remediation, catalysis, and sustainable agriculture, aiming to achieve a greener future. The deployment of crop residues as a renewable feedstock for biochar, and their properties, compositions, modification, and functionalization techniques are also discussed. Additionally, the avenues for applying functionalized biochar to achieve a greener future, future trends and innovations, challenges, and future research directions are highlighted. Despite the limitations of scalability, ecotoxicological risks, logistical issues, lack of characterization protocols, high production costs, poor social acceptance, and inadequate policy and regulatory frameworks, functionalized biochar offers a better surface area, improved porosity, enhanced functional groups, and higher recoverability, leading to improved performance, adsorption capacity, biodegradability, and applications in specialized fields. Future research should prioritize standardization, scalability, cost reduction strategies, expansion of application areas, integration of emerging tools such as artificial intelligence and predictive modeling, and the development of policy and regulatory frameworks, ensuring that biochar’s full potential is harnessed effectively to support a low-carbon, resource-efficient future and global sustainability goals.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Environmental issues such as pollution, global warming, and climate change are among the most pressing challenges affecting human health and the ecosystem globally today. Increasing population growth, overdependence on fossil-based (FB) energy sources, and rising industrial activities have exacerbated environmental pollution, negatively impacted air quality, and pose a significant ecological challenge [1]. Apart from these unwanted consequences, human activities such as urbanization, increased agricultural activities and food production, and improper waste disposal and management continue to release greenhouse gases (GHG) and other anthropogenic gases that threaten the Earth and its inhabitants. The global emission of GHGs has increased significantly in recent decades due to increased consumption of FB fuels for transportation, heat, and electricity generation, manufacturing, and other human activities [2]. A recent report indicated that the global GHG emissions, which were 8.69 billion tonnes (t) in 1900, rose to 22.13 billion t in 1960 and further to 53.82 billion t in 2023 [3]. The astronomical rise in GHG emissions has led to a rise in global temperature, environmental pollution, changes in weather patterns, and other climate change consequences. During the same period, the global population increased from about 1.6 billion in 1900 to 3.015 billion in 1960 and further to 8.092 billion in 2023 [4]. Fig. 1 shows the global population and GHG emissions between 1900 and 2023.

Figure 1: Trend in global GHG emissions and global population from 1900 to 2023. Data culled from [3,4]

A green future refers to a sustainable and environmentally friendly vision for the world, where societies prioritize clean energy, resource conservation, and ecological balance. It involves adopting practices that reduce carbon emissions, promote renewable energy, ensure economic stability, support a circular economy, and contribute to overall well-being. Biochar, a carbonaceous and charcoal-like solid material produced from the pyrolysis of biomass, is emerging as a versatile material with promising applications in diverse fields and contributing to a greener future. Pyrolysis is a thermochemical process involving heating of appropriate feedstock at high temperatures (typically 400°C–700°C), in an anaerobic environment, to produce biooil, syngas, and a solid residue called biochar. Feedstocks are the raw materials, such as agricultural waste, animal manure, forest residues, sewage sludge, etc., that are subjected to thermochemical degradation to produce biochar and other useful products. Biochar production is also an effective strategy for waste conversion, repurposing, management, and turning organic residues into valuable resources. Similarly, biochar is being integrated into construction materials, coatings, and even carbon-based electronics for sustainable innovation and energy security [5]. Crop residues such as stalks, shells, peels, straws, cobs, wood chips, etc., have been used as feedstock for biochar generation due to their ready availability, accessibility, renewability, versatility, low cost, and high carbon content. The deployment of crop residues for biochar production also supports resource recovery, circular economy, reduces open burning and landfill use, contributes to sustainable waste management strategies, and promotes sustainable agriculture. Some of the environmental benefits of biochar production and application include serving as a long-term carbon sink, reducing the emissions of methane and nitrous oxide, protecting groundwater, and helping in the remediation of contaminated soils [6,7].

Over the recent past and with increased applications and advancement of research into the production and utilization of biochar, there is a need to increase the effectiveness and areas of applications of biochar. These quests have led to research into biochar modification through functionalization. Biochar functionalization is crucial for enhancing its properties and expanding its applications in environmental and industrial fields to meet the contemporary demands [7]. Functionalization of biochar enhances the surface chemistry and ensures better adsorption efficiency in capturing heavy metals, organic contaminants, and other emerging pollutants. Functionalized biochar enjoys improved active sites and can be customized for catalysis, biomedical, chemical reactions, energy storage, soil remediation, and other specialized applications. Modified biochar exhibits greater stability, durability, regenerability, and reusability, ensuring long-term effectiveness in environmental applications [8,9]. In recent studies, functionalized biochar has been used to enhance anaerobic digestion [10], improve the electrochemical properties of secondary batteries [11], biomedical applications [12], adsorption of heavy metals [13], removal of toxic chemicals for wastewater [14], and other applications to ensure environmental sustainability [15]. These advancements in biochar utilization have made further study on the techniques and application of functionalized biochar a worthwhile venture.

In their separate studies, Seo et al. [16], Haris et al. [17], and Kumar et al. [18] investigated the synthesis, properties, characterization, application, benefits, limitations, and future research directions of biomass-derived biochar in various sectors. While acknowledging the multifarious and effective application of biochar, they recommended further study to promote sustainable, economic, large-scale, and eco-friendly biochar production and utilization, ultimately supporting biorefinery and circular economy. Researchers opine that functionalization of biochar enhances its physicochemical properties, surface chemistry, porosity, surface geometry, the adsorption capacity, and tailors it towards more effective applications in energy storage [19], carbon capture [20], pollutants removal [21], wastewater treatment [22], soil remediation [23], catalytic activities [24], microbial processing [25], sustainable agriculture [26], and environmental sustainability [27]. Other state-of-the-art studies on the methodology, progress, challenges, and future perspectives to harness the power of functionalized biochar for novel applications in catalysis, resource recovery, microbiological, and bio-electrochemical systems have also been reported [28,29]. In their separate research, Eltaweil et al. [30], Wibowo et al. [31], and Ma et al. [32] investigated the influence of modification techniques such as doping, ball milling, biological, etc., on the performance and effectiveness of biomass-derived biochar. Though they acknowledged the effectiveness of modified biochar for various applications, they were unanimous in recommending further studies to overcome the technical, economic, infrastructural, and environmental challenges in the process. Various review papers and perspectives have been published in the recent past to advance research in the preparation, modification, and application of functionalized biochar [33,34]. Table 1 summarizes the highlights of some of the recent review articles on the production and application of functionalized biochar for various applications. None of the previous reviews has specifically focused on the application of functionalized biochar for energy storage, environmental remediation, catalysis, and sustainable agriculture towards achieving a greener future, which is the main crux of this study. The work of Xiao [35] and Lu et al. [36] was limited to the application of thermal air oxidation for biochar modification, while Venkatachalam et al. [37], Qu et al. [38], and Alawa et al. [39] deployed modified biochar for the removal of cadmium and other pollutants from contaminated soil. Despite the obvious benefits of functionalized biochar, some noticeable challenges, including scarce active sites, inadequate active functional groups, underdeveloped pore structure, high production costs, concerns for secondary pollution, etc., have been identified, which necessitates further study [40,41].

From the foregoing, it is clear that the preponderance of existing reviews provided narrow information on the production and utilization of functionalized biochar. With increased demand for low-cost, sustainable, and waste-derived biochar, the need for improved biochar to meet the global demand has never been more urgent. There is a need to publish a new review to update existing information, capture new data, aggregate recent outcomes, and suggest future research directions in the field. These are the motivations behind this study. The aim of the study, therefore, is to review recent advancements in biochar functionalization as a sustainable pathway towards achieving a green future. The objective of the study is to provide new insights into the modification of crop residue-derived biochar and its application for a greener future. Unlike the available reviews on the subject, including Dong et al. [41], Huang et al. [42], and Singh et al. [43], this intervention contains an exhaustive discussion on the description, benefits, and limitations of various biochar functionalization techniques and application of functionalized biochar for energy storage, environmental remediation, catalysis, and sustainable agriculture, in one document. The inclusion of case studies, future trends, and innovations sets it apart from previous works and further contributes to the novelty of the study. In this study, separate sections are dedicated to crop residues as renewable feedstock for biochar, methods of biochar modification, biochar functionalization techniques, application of functionalized biochar for a green future, case studies and innovations, challenges, future research directions, and conclusions. The scope of this review is limited to the review of synthesis, activation, modification, and application of functionalized biochar derived from crop residues for a green future, using information extracted from recently published literature. The actual biochar synthesis, modification, characterization, and utilization are beyond the scope of this study. The outcome of this study will update existing information and provide new insights, guidance, and motivation for researchers, environmentalists, and other stakeholders in biochar modification and application towards achieving the circular economy and sustainability.

2 Crop Residues as Renewable Feedstock for Biochar

2.1 History and Definition of Biochar

Biochar has its historical roots in the Amazon Basin of South America, over 2500 years ago, where indigenous people created a dark, charcoal-rich residue to improve soil fertility. However, modern-day renaissance and scientific understanding of biochar came with the work of Justus von Liebig around the mid-19th century. The work of the German chemist laid the foundation and renewed scientists’ interest in research into the production and potential application in areas other than agriculture and soil improvement [45]. Other historical information has shown that biochar was applied for agricultural purposes in Japan, Korea, and other Asian countries. Subsequently, the awareness of biochar increased with many countries forming National Biochar Societies to initiate, champion, and expand the frontiers of research in biochar. Since the first meeting of the International Biochar Advocacy Organization held in Australia in 2007, the quantum and intensity of biochar research has increased in all its ramifications [45,46]. Today, with the surging population, an increase in human activities, rising industrialization, and technological advancements, research into the feedstock selection, production techniques, and utilization avenues of biochar has increased tremendously.

According to the International Biochar Initiative, biochar is a solid carbonaceous residue generated through the thermochemical degradation of various biomass at elevated temperature in an oxygen-controlled environment [47]. In their recent study, Awogbemi and Kallon [48] defined biochar as a solid, hard, charcoal-like, and carbon-rich residue obtained from the high-temperature decomposition of biomass under a controlled environment. According to Hagemann et al. [49] and Wiinikka et al. [50], biochar is different from charcoal and activated carbon. Charcoal is described as a solid carbon-rich woody material usually produced from woody biomass and other waste materials as feedstock and used as fuel and reducing agent in metallurgical and metal processing. Activated carbon, also a carbonaceous solid residue produced from biomass materials like coal, lignite, tar pitch, and other similar feedstocks. Comparatively, biochar is obtained during the pyrolysis of biomass, while activated carbon is produced from physical or chemical modification of biochar. Charcoal is a product of wood carbonization and is commonly used as a renewable solid fuel [48,51].

2.2 Biochar Feedstock and Generation

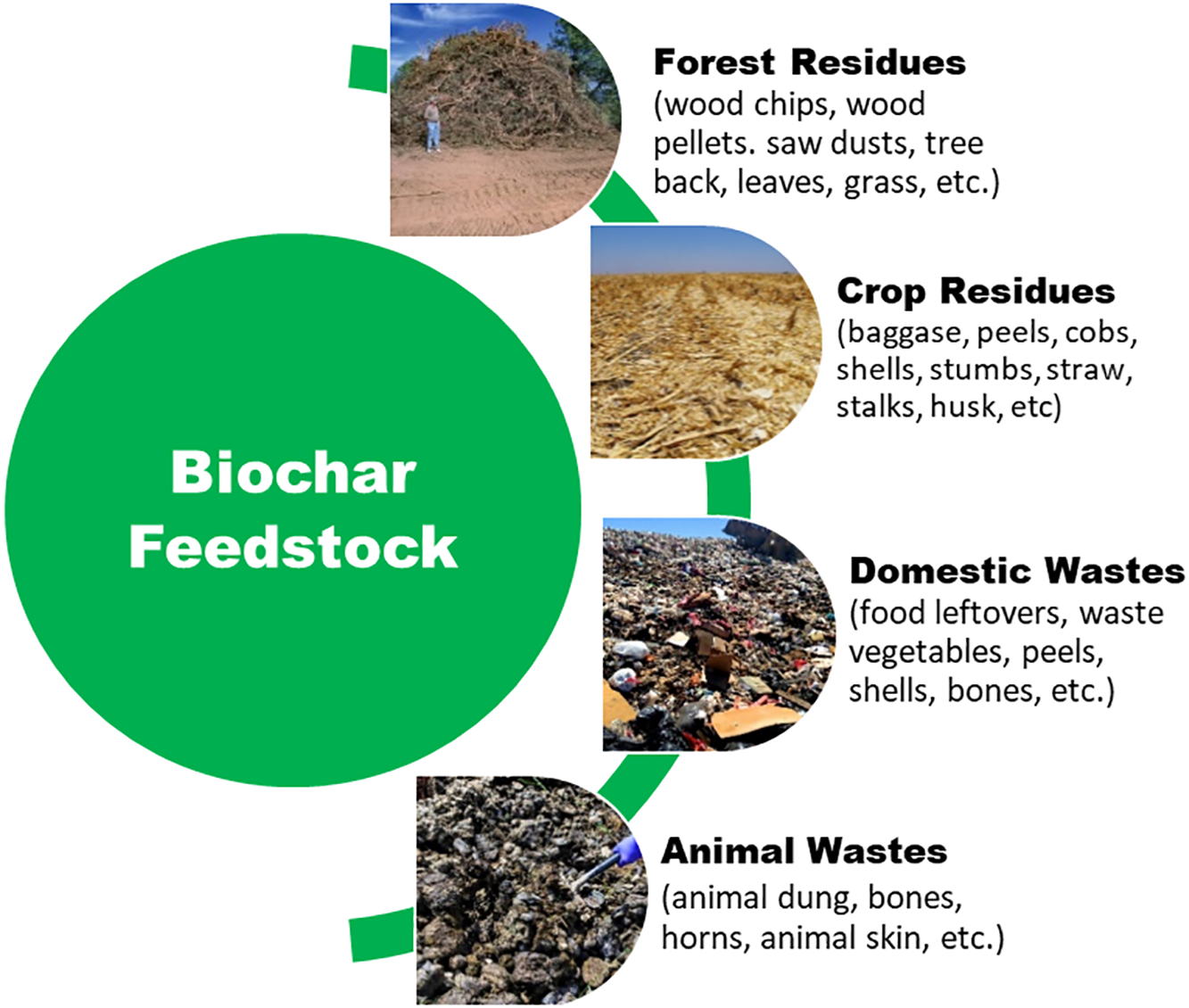

Primarily, biochar can be produced from any carbon-rich organic material. However, to align with the concept of circular bioeconomy, recycling, and for economic and environmental sustainability, lignocellulose biomass such as agricultural waste, crop residues, food leftovers, animal bones and horns, animal wastes, mill residues, algae, etc., have been used as feedstock to manufacture biochar [52]. The construction of biochar from waste biomass supports sustainable waste management, reduces the cost of waste disposal, helps divert waste from landfills, reduces the need for open burning of waste, and minimizes the emission of toxic gases from open burning. The conversion of waste materials to useful biochar supports job creation, creates additional income to farmers and households, and helps in meeting some of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [53]. Prominent waste materials that have been used as feedstock for biochar production can be categorized as forest waste, crop residues, domestic waste, and animal waste, as shown in Fig. 2. The choice of crop residues as feedstock for biochar production supports food security, prevents the food vs. fuel debate, and cost-effective production of biochar.

Figure 2: Categories of biochar feedstock

Crop residues are increasingly being used as feedstock for biochar production due to their abundance, renewability, easy accessibility, low cost, easy digestibility, and environmental sustainability. Biochar manufactured from crop residues such as cotton stalks, soybean straw, pigeon pea stalks, rice husks, sugarcane bagasse, and corn cobs is easily converted, demonstrates high carbon content and low ash content, and offers several environmental and agricultural benefits [54]. Phadtare and Kalbande [55] assessed the potential of cotton stalks, soybean straw, and pigeon pea stalks for biochar production. They reported that the crop residues generated high-yield and quality biochar, which can be used for soil enhancement. In a similar study, biochar derived from pigeon pea stalk exhibited maximum cation exchange capability, improved fixed carbon, energetic retention efficiency, and good agronomic characteristics, which can be exploited for soil carbon sequestration and use as solid fuel [56]. The cradle-to-gate analyses of biochar constructed from rice husk, sugarcane bagasse, and corn cob reveal that the process is cost-effective, eco-friendly, has a lesser environmental impact, and demonstrates low global warming potential, while demonstrating a high potential for carbon sequestration [57].

Conversion of feedstock to useful biochar involves a series of processes including collection and sorting of waste biomass, preparation and pretreatment, selection of conversion technique and processing parameter, feedstock conversion, and product separation. Feedstock for biochar is collected from farms, households, industries, abattoirs, and other locations where they are sorted and separated before being transported to the location of the conversion plant. At the conversion site, the feedstocks are screened to remove any unwanted materials and prevent contamination of the feedstock, preparatory to loading them into the conversion chamber. Most feedstocks, due to their composition, nature, types, etc., are recalcitrant, intractable, and difficult to convert; hence, they need to be pretreated. Pretreatment of biochar feedstock is a series of processes deployed to adjust, modify, and transform raw biomass before its actual conversion. The pretreatment techniques alter the moisture content, composition, physical, chemical, surface, and biological characteristics of the biomass [58]. Recent studies by Awogbemi and Kallon [59], Ramos et al. [60], and Prasad et al. [61] classified biomass pretreatment approaches into physical, chemical, biological, physicochemical, and green solvent-based techniques and extensively discussed the major examples, benefits, and drawbacks of each pretreatment technique. Fig. 3 shows the major biomass pretreatment techniques. Pretreatment of feedstock enhances the feedstock quality, improves the structural properties, reduces contaminants, and prepares the feedstock for the conversion process. In some cases, wet biomass is dehydrated to reduce the moisture content and reduce decay or insect infestation, while other biomass may be cut into smaller pieces to increase the surface contact during conversion [62,63]. Though the cost of pretreatment adds to the production costs and needs extra energy, manpower, machinery, and other logistics, pretreatment enhances the digestibility and biodegradability of the feedstock and ensures the generation of quality products. When compared with untreated feedstock, pretreated feedstock requires less time, energy, and cost for conversion, demonstrates higher conversion efficiency, and ensures improved biochar yield [64].

Figure 3: Major biochar feedstock pretreatment techniques and their examples

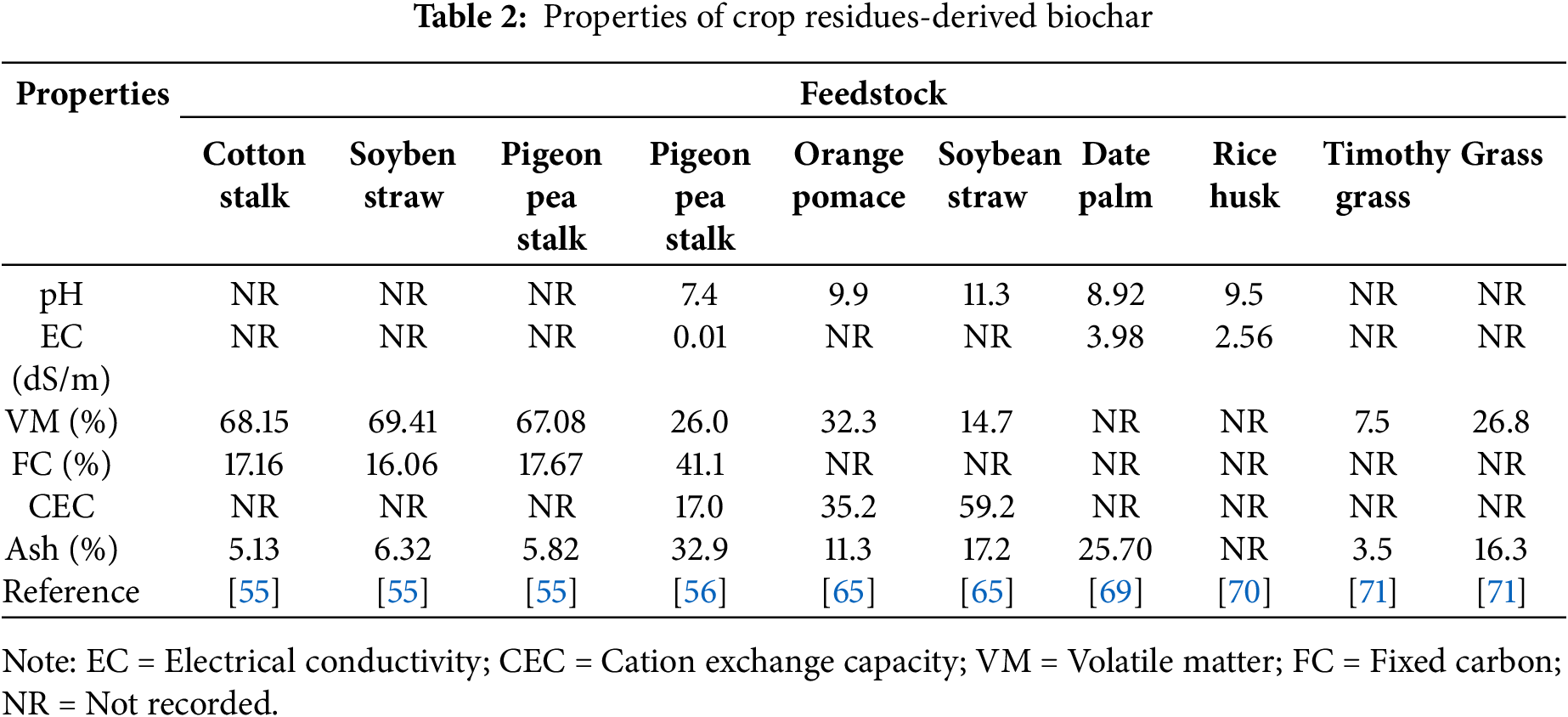

The key properties of biochar are the characteristics that determine and make it valuable for various applications, including agriculture, environmental remediation, and energy storage. The properties of biochar, such as physical properties, chemical properties, elemental composition, and surface characteristics, are largely dependent on the feedstock type, pyrolysis temperature, and residence time [65]. Among the important properties of biochar are density, particle size, pore size and volume, structural porosity, specific surface area, grindability, thermal conductivity, heat capacity, hydrophobicity, and water retention capacity. The required chemical properties of biochar include carbon content, volatile matter, ash content, pH, electrical conductivity, reactivity, functionality, proportion of atoms, and cation exchange capacity (CEC) [66,67]. The presence of essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen in biochar influences its utilization area. The limiting potential property of biochar allows it to act as a liming agent, alter soil pH, and improve the soil microbial activity. Biochar’s electrochemical conductivity is an important property that influences soil redox reactions, affecting nutrient availability and microbial interactions [68]. The elemental composition (CHNO), atomic ratios (O/C and H/C), surface area, total volume, micropore volume, and average pore size are some of the characteristics of biochar that determine its applications. Table 2 shows the physical and chemical properties of some crop residue-derived biochar, while Table 3 compiles the elemental composition, atomic ratios, surface area, total volume, micropore volume, and average pore size of some crop residue-derived biochar.

3 Methods of Biochar Modification

The raw biochar manufactured through the pyrolysis or carbonization of biomass exhibits inappropriate properties and lower quality in physical, chemical, compositional, and structural characteristics, such as reduced pores, smaller surface area, and fewer surface functional groups. These inadequacies impact the properties and performance of biochar during application, necessitating modification. Biochar modification involves the process of altering and adjusting the properties of biochar to improve performance. Biochar activation primarily focuses on increasing the surface area and porosity of biochar and can be achieved through physical, chemical, or biological methods. The goal of biochar activation is to get biochar with enhanced surface area, porosity, and adsorption capacity. For effective biochar activation, the specific activation method and parameters must be carefully chosen. The choice activation method depends on the anticipated application of the biochar, while the activation parameters, such as temperature, time, and activator type, can significantly affect the output of the activation and the final properties of the biochar [73].

Physical activation of biochar involves exposing biochar to oxidizing agents like steam, air/oxygen, or CO2 treatment at high temperatures, usually 350°C–1100°C. During the steam activation, biochar is exposed to steam maintained at high temperature and in the process removes impurities, volatile compounds, and enhances the pore volume [74]. Products of steam activation are commonly used for water purification and gas adsorption systems to remove heavy metals and organic pollutants. The CO2 activation involves treating biochar with CO2 at elevated temperature, where the CO2 acts as an oxidizing agent, thereby creating a highly porous structure. CO2-activated biochar is applied as a catalyst and for the production of supercapacitors for energy storage applications. Air/oxygen activation is achieved through controlled oxidation of biochar to enhance the surface configuration and functionality, making biochar more effective for soil amendment, nutrient retention, and pollutant removal [75,76].

Chemical biochar activation is a process that enhances the surface properties of biochar by introducing chemical agents that modify its structure and functionality. This method is widely used to improve biochar’s adsorption capacity, catalytic activity, and overall effectiveness in environmental and industrial applications. The process involves the addition of activators such as acids, alkalis, or metal oxides to modify the biochar’s structure. The chemical activation can be done during pyrolysis or as a post-treatment process after the biochar is produced [77]. During the alkaline activation, NaOH, KOH, or similar alkalis react with the carbon materials in the biochar to increase the surface area and create micropores. Alkaline activated biochar is commonly used as supercapacitors for energy storage, as catalysts, and for carbon capture due to its improved surface area. The use of acidic activators such as H2SO4 or H3PO4 in biochar modification is to introduce functional groups that enhance ion exchange and adsorption. Chemical activation of biochar can also be achieved through metal impregnation when metals such as iron, copper, or zinc are infused into the biochar to improve its catalytic properties for applications such as biomass hydrolysis and biodiesel production [78,79]. The addition of oxidizing agents like hydrogen peroxide or nitric acid to biochar can also modify the surface chemistry and enhance the absorption property of biochar [80].

Biological activation of biochar is the deployment of microorganisms, enzymes, or organic compounds to modify and enhance the effectiveness of biochar for various biochemical, bioremediation, and adsorption applications [81]. This can be achieved through microbial inoculation, during which biochar is infused with beneficial microbes such as bacteria and fungi to alter its biochemical characteristics and enhance its ability to support plant growth and soil health. Biological activation through composting integration involves mixing compost with biochar to allow organic matter and nutrients to bind to its surface and improve soil fertility. The addition of specific enzymes to biochar modifies its surface chemistry, alters the functional group, and enhances its effective application for bioremediation and wastewater treatment. The soaking of biochar in nutrient-rich solutions (such as manure or plant extracts) improves its adsorption capacity and microbial activity [82,83]. Patra et al. [84] reported that enzyme-treated biochar demonstrated improved biochemical characteristics and enhanced biochar application in bioremediation, soil amendment, anaerobic digestion, and removal of organic pollutants.

4 Biochar Functionalization Techniques

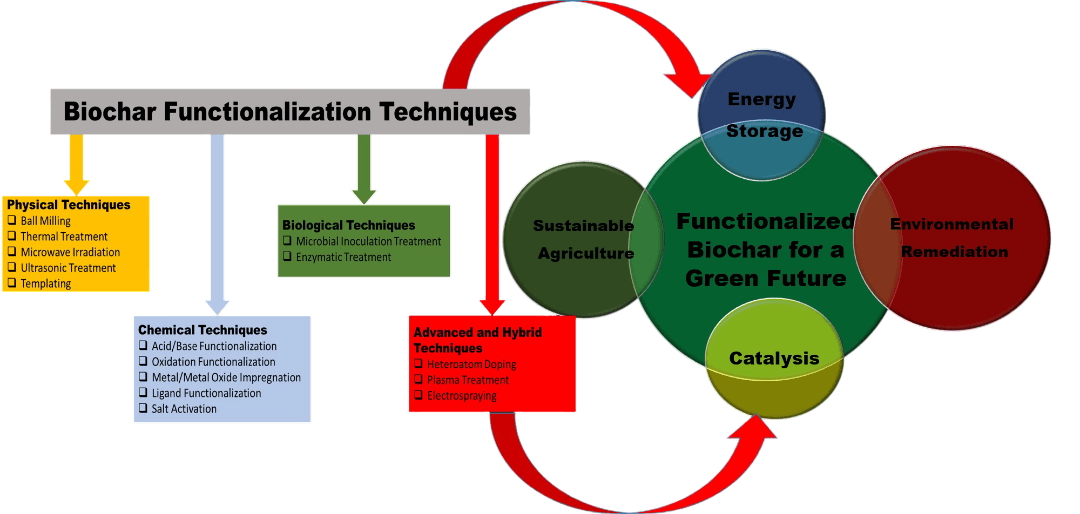

Biochar functionalization refers to the process of modifying the surface chemistry of biochar to enhance its properties for specific applications. While raw biochar has inherent porosity and adsorption capabilities, functionalization further enhances its effectiveness in environmental and industrial applications. This involves introducing functional groups, metals, non-metals, or polymers to improve their reactivity, adsorption capacity, and catalytic performance. Biochar functionalization can be achieved through physical techniques, chemical techniques, biological techniques, and other techniques (Fig. 4). The functionalization techniques aim to improve the physicochemical properties, electrochemical characteristics, and surface active sites of raw biochar, leading to improved performance across various applications. While activation improves the physical structure of biochar, functionalization modifies the chemical properties for specialized applications. Table 4 summarizes the operating conditions, benefits, limitations, and areas of application of major functionalization techniques.

Figure 4: Major biochar functionalization techniques and their examples

4.1 Physical Biochar Functionalization Techniques

Physical biochar functionalization involves modifying the surface properties of biochar through mechanical, thermal, or structural treatments without the use of chemicals. These techniques enhance biochar’s porosity, surface area, and adsorption capacity, making it more effective for environmental and industrial applications [85]. Physical functionalization of biochar is achieved through ball milling, thermal treatment, microwave irradiation, and ultrasonic treatment. During ball milling, biochar is pulverized into finer particles using mechanical milling to increase the surface area and improve its adsorption properties. Though ball milling biochar functionalization appears simple and easily achievable, the biochar quality depends on milling type, ball size, vibrational amplitude, rotational type, milling medium, speed, duration, feedstock-to-balls, and other operational parameters. To improve the quality of the product, the high-energy ball milling technique can be employed at elevated temperatures and pressures for the synthesis of micro- and nano-sized biochar particles [86,87]. Though ball milling alone does not create new chemical bonds, the process exposes and amplifies existing oxygen-containing groups, like hydroxyl (OH), carboxyl (COOH), and carbonyl (C=O), by breaking down the carbon matrix in the raw biochar. The ball milling technique of biochar functionalization exemplifies a greener, cost-effective, and eco-friendly approach for producing biochar-based nanomaterials from biomass resources. However, the challenges of inaccurate measurement of process parameters, lack of control over particle morphology, and possible formation of agglomerates require process optimization and other theoretical investigations [88,89].

Thermal treatment is a physical biochar functionalization technique that modifies biochar’s pore structure and surface properties by exposing it to controlled elevated temperatures. This process enhances porosity, surface area, and surface chemistry, making biochar more effective for various applications. Thermal treatment also boosts existing oxygen-containing groups like OH and COOH, thereby enhancing surface area and porosity, indirectly affecting functional group exposure. The modification can occur during the biochar production when pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, and residence time are adjusted and optimized to fine-tune biochar’s structural properties [35]. Kim and Jung [89] reported that biochar manufacture at 600°C–800°C demonstrated increased surface area and microporosity, making it ideal for adsorption of pollutants. Post-pyrolysis heat treatment is a form of modification where biochar is subjected to additional thermal processing to remove impurities and enhance its adsorption capacity [90]. Biochar functionalized by thermal treatment shows increased specific surface area, improved adsorption capacity, better graphitization, and more resistance to degradation, and is applied for energy storage, soil amendment, carbon sequestration, pollutants adsorption, and environmental remediation [91].

The microwave irradiation functionalization technique involves exposing biochar to microwave energy, causing dipole rotation and ionic conduction, which induces efficient, rapid, and uniform heating and structural changes, improving its surface morphology, porosity, functional groups, and creating more active sites. The process occurs typically between 400°C–900°C, 500–2000 W, for 5–30 min, and in an inert gas (nitrogen or argon) environment [92,93]. In a recent study, Zhang et al. [94] employed microwave irradiation to increase the micropore structure and absorptive characteristics of raw biochar for various applications. They reported that the functionalized biochar demonstrated excellent reusability, improved pollutant absorption, CO2 capture, catalysis, and wastewater treatment. The microwave irradiation functionalization technique introduces OH, C=O, COOH, and sulfonic (–SO3H) functional groups thereby enhancing the porosity, surface area, and oxygen-containing groups of raw biochar for adsorption and catalysis applications. The application of the microwave irradiation functionalization technique is cost-effective, consumes low energy, ensures environmental sustainability, and improves the utilization of biochar. The limitations of the technique include high cost of specialized equipment, challenges in industrial-scale implementation, and feedstock sensitivity [95]. With appropriate R&D in process parameters optimization, implementation of hybrid modification methods, and industrial scale development, microwave irradiation biochar functionalization can become a more useful and effective biochar modification technique.

Ultrasonic treatment biochar functionalization is a technique that enhances biochar properties using ultrasound waves. The process involves exposing biochar to ultrasonic energy, which induces cavitation, exfoliation, and structural modifications, improving its surface area, porosity, and functional groups. During the process, ultrasonic waves at 20–40 kHz and 100–1000 W are applied to break down raw biochar particles, thereby enhancing their dispersion in solutions during applications [96]. Ultrasonic treatment of biochar is energy efficient, sustainable, and guarantees fast and uniform modification of biochar. Ultrasonically functionalized biochar demonstrates improved porosity and adsorption capacity, sustainability, and better bioremediation, notwithstanding the high cost of specialized ultrasonic reactors, limited scalability, and other technical challenges. In their separate studies, Wang et al. [97] and Shafawi et al. [98] ultrasonically modified raw biochar to trigger the sonocatalytic performance and promote the adsorption ability of raw biochar for the removal of heavy metals in water, the adsorption of carbon dioxide, and soil remediation. They recommended further study on optimization of ultrasonic parameters and further research to address the scalability issue and promote industrial-scale development.

Templating biochar functionalization is a technique used to modify biochar properties by introducing a structured template during synthesis. This method enhances the surface area, porosity, and functional groups of biochar, making it more effective for applications such as adsorption, catalysis, and energy storage. During templating, raw biochar is heated to between 400°C and 900°C for several hours in the presence of templates such as silica, zeolites, and metal oxides, and in the process, creates well-organized porous structures in the biochar. The templating technique can be categorized as either soft templates or hard templates. Soft templates use surfactants, block copolymers, and ionic micelles to control porous structures in raw biochar [99]. On the other hand, hard templates involve the use of zeolites, silica, metal oxides, clay materials, and other inorganic porous solids for raw biochar functionalization [100]. Previous studies by Zheng et al. [101] and Hu et al. [102] employed templating technique for the functionalization of raw biochar to enhance its absorbability and ensure higher removal efficiency of tetracycline and other pollutants from wastewater. The technique produced structured biochar with physicochemical properties for the specific applications, with an adsorption capacity of 238.7 mg/g. Templating is energy efficient, modifies the pore structure, and ensures improved porosity and adsorption capacity of raw biochar. However, the high cost of specialized templating materials, prohibitive setup expenses, and the need for additional template removal setup are some of the challenges of the process [29,103].

4.2 Chemical Biochar Functionalization Techniques

In contrast to physical functionalization, chemical biochar functionalization involves modifying biochar properties using chemical treatments to enhance its surface chemistry, adsorption capacity, catalytic activity, and environmental applications. This process typically includes acid/base treatments, oxidation, metal impregnation, and polymer grafting to introduce functional groups that improve biochar’s reactivity.

Acid/base biochar functionalization involves treating biochar with acidic/alkaline solutions to enhance its surface properties. This process introduces functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and sulfonic groups, improving its adsorption capacity, catalytic activity, and chemical reactivity. The process entails using common acids such as H2SO4, HNO3, H3PO4, or alkaline solutions like NaOH, KOH, Ca(OH)2, etc., at concentrations 0.1–2 M, and temperatures between 50°C and 150°C to introduce functional groups, enhance surface charge, porosity, and adsorption capacity [104]. The pH control ensures the adjustment of the acidity to achieve optimal functionalization and prevents excessive degradation. The acid/base functionalization introduces hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups to enhance surface acidity, hydrophilicity, and metal adsorption capacity. Yameen et al. [29] and Varkolu et al. [105] in their separate studies modified raw biochar from various biomass sources by acid functionalization for various applications. The acid-functionalized biochar demonstrated enhanced efficiency in the removal of arsenic and lead from contaminated water and better CO2 adsorption capacity in industrial settings. Acid-functionalized biochar was effective in the removal of dye and other organic pollutants, showed better porosity and surface configuration, and improved chemical stability. However high cost of acid and environmental concerns arising from handling and disposal of spent acids are some of the limitations of the process. Optimization of acid concentration, use of alternative acids, and further studies of details characterization to assess modification are the recommended areas of improvement [106].

Oxidation functionalization involves treating biochar with oxidizing agents such as nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide, or ozone to introduce functional groups like carboxyl, hydroxyl, and carbonyl. This process enhances biochar’s adsorption capacity, catalytic activity, hydrophilicity, and chemical reactivity. Raw biochar reacts with an appropriate oxidizing agent, such as nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide, ozone, or piranha solution, at 50°C–150°C to facilitate functional group attachment [107]. The application of oxidation functionalization introduces hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl groups to the raw biochar, boosting surface polarity and reactivity for adsorption and catalysis applications. Di Vincenzo et al. [108] reported that oxidized biochar has been successfully used to remove heavy metals from contaminated water and for CO2 adsorption in industrial applications. The oxidized biochar was effective in pollutant removal, demonstrated improved catalysis, and greater resistant to environmental degradation. Researchers have recommended the use of alternative oxidation methods, thorough washing to remove excess oxidizing agents, and optimization of oxidizing agent concentration to balance functionalization and structural integrity as areas of further studies [109].

Unlike the oxidation technique, the metal/metal oxide functionalization method involves impregnating biochar with metal or metal oxide nanoparticles (e.g., Fe, Cu, Zn, TiO2, MnO2) to improve its reactivity, stability, adsorption capacity, and electrochemical properties. The process enhances biochar’s ability to act as a catalyst, adsorbent, or electrode material. The common impregnation techniques, wet impregnation, sol-gel synthesis, precipitation, or hydrothermal treatment, are carried out at 50°C–300°C for several hours to facilitate metal/metal oxide attachment [110]. Dey and Ahmaruzzaman [111] and Ramos et al. [112] demonstrated the impregnation of raw biochar with nano metal, nano metal oxides, and nano nonmetal to improve its physical adsorptive and electrochemical properties for sustainable biorefinery, electrocatalysis, and energy storage applications. Metal/metal oxide impregnation functionalization is effective in enhancing the adsorptive, structural stability, and catalysis capabilities of raw biochar, making the product suitable for batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells. This is achieved by the introduction of metal atoms (Fe, Zn, Cu, etc.) to improve the catalytic or redox-active sites for specific applications. However, the high cost of metal/metal oxide nanoparticles, handling of residues, and environmental concerns regarding the disposal of metal-functionalized biochar are potent limitations that must be addressed through more R&D [113].

Ligand functionalization involves chemically modifying raw biochar by attaching ligands such as amine (-NH2), thiol (-SH), carboxyl (-COOH), and phosphate (-PO4). These ligands enhance biochar’s ability to interact with metal ions, organic pollutants, and biomolecules, making it more effective in adsorption, catalysis, and environmental remediation. Reactions between raw biochar and ligand through covalent bonding, electrostatic interactions, or chelation at specified conditions facilitate the attachment of ligand to the surface of the biochar, thereby modifying the structure for effective operation [114]. Raw biochar modified with lignands shows enhanced adsorption, improved catalytic properties, and better chemical stability. Huang et al. [115] reported that raw biochar manufactured from wheat straw and modified with phosphate was effective in the removal of 99.98% phosphorus, arsenic, and lead from contaminated water. Raw biochar modified with ligands demonstrates better adsorption, improved chemical stability, and enhanced catalytic properties. Ligand leaching, high cost of ligands, and environmental concerns about the disposal of modified biochar are some of the limitations of the process. Ligand-functionalized biochar is useful in wastewater treatment, as a catalyst for chemical reactions, energy storage, and applied in drug delivery and biosensing [116].

Salt activation functionalization of biochar is a technique used to enhance its surface properties by introducing molten salts or salt solutions such as KCl, NaCl, and ZnCl2 that modify its porosity, adsorption capacity, and catalytic activity. The process improves biochar’s structural and chemical properties and enhances biochar’s ability to adsorb pollutants, catalyze reactions, and store energy [117]. The raw biochar is activated with the appropriate salts through molten salt impregnation, salt-assisted pyrolysis, or salt leaching at 400°C–900°C, depending on the salt and biochar source. Egun et al. [118] investigated the production, usefulness, and applications of molten salts activated raw biochar. The activated biochar showed improved specific surface area and was effective in energy storage, catalysis, and pollutant adsorption. Salt activation of raw biochar ensures superior adsorption of pollutants from water and air, improves environmental remediation and chemical synthesis, and exhibits excellent resistance to degradation in harsh environments [119]. Some of the drawbacks of the process include structural damage, high cost of salts and equipment, and environmental concerns arising from the disposal of salt-functionalized biochar.

4.3 Biological Biochar Functionalization Techniques

Another approach to biochar functionalization is the biological technique, which involves the use of microbial inoculation and enzymatic treatment. Microbial inoculation treatment of biochar is a technique used to enhance its biological activity by introducing beneficial microorganisms. The process involves integrating raw biochar with beneficial microbes such as nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, and mycorrhizal fungi. This process improves biochar’s ability to support soil health, nutrient cycling, and pollutant removal. The inoculation is done by soaking, spraying, or mixing biochar with microbial cultures for a specified duration [120]. Gryta et al. [121] and Sharma et al. [122] modified raw biochar with microorganisms to alter the composition and physicochemical properties of biochar for diverse applications. The microbial-inoculated biochar was used for bioremediation, to improve soil fertility, and promote soil aeration and moisture retention. The challenges of microbial survival, maintaining microbial viability, and the high cost of specialized equipment are some of the limitations of the process. Further studies are required to optimize microbial selection based on soil and crop requirements and conduct DNA sequencing, microbial activity assays to assess the effects of the modifications [123].

Enzymatic treatment of biochar is an innovative technique that enhances its surface properties by integrating enzymes onto biochar to enhance its ability to degrade pollutants, catalyze biochemical reactions, and improve nutrient cycling. The process leverages biochar’s porous structure to provide a stable environment for enzyme activity. Enzymes such as laccase, peroxidase, cellulase, and protease are immobilized through physical adsorption, covalent bonding, entrapment, or cross-linking at 25°C–60°C to ensure enzyme stability [124]. The process introduces enzyme-linked groups (e.g., phenolic, carboxyl, amine), enabling targeted catalytic and environmental applications. Mota et al. [125] reported that enzymatic immobilization of raw biochar modified the physicochemical, chemical structure, and stability of the biochar for various applications. Enzyme-coated biochar demonstrated enhanced drug delivery capabilities, improved oxidation reaction, and better biodegradation of organic pollutants in wastewater. Though the process is sustainable and occurs at low temperatures, the high cost of some enzymes and equipment, possible structural damage to the biochar, and enzyme leaching limit the application of the process [126].

4.4 Advanced and Hybrid Biochar Functionalization Techniques

Due to advancements in research, advanced and hybrid biochar functionalization techniques, such as heteroatom doping, plasma treatment, and the electrospraying technique, have been developed. Heteroatom doping involves introducing non-carbon elements into the biochar matrix through chemical or physical methods. These heteroatoms alter the electronic structure, surface functional groups, and porosity of biochar. The process entails doping heteroatoms such as nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, and boron into raw biochar at 400°C–900°C for a few hours. Depending on the doping atom, the functionalization process introduces P-O, P=O, -SH, -SO, -SO2, B-C, B-O, pyrrolic-N, graphitic-N to biochar surface. The doping can occur before pyrolysis (pre-decoration doping) or after pyrolysis (post-decoration doping) [127]. Sun et al. [128] and Yang et al. [129] in their separate studies on the fabrication, characterization, doping methods, and functions of heteroatom-doped biochar reported that the modified biochar demonstrated increased surface area, porosity, adsorption, and better electrochemical performance. The heteroatom-doped biochar was effective for CO2 adsorption, energy storage, contaminant removal, and other environmental remediation purposes. However, there is a need for more research to devise cost reduction measures, explore alternative doping methods, and optimize heteroatom concentration to balance functionalization and structural integrity [130].

Plasma treatment involves exposing biochar to ionized gases (plasma) to introduce functional groups (-OH, -COOH, C=O), increase porosity, and improve surface reactivity. Different types of plasma, non-thermal plasma, dielectric barrier discharge, and radio-frequency plasma, have been used to expose gases such as oxygen (O2), nitrogen (N2), argon (Ar), and chlorine (Cl2) at temperatures less than 200°C [131]. Zhou et al. [132] carried out non-thermal plasma surface functionalization to promote more oxygen-containing functional groups and promote follow-up applications. The plasma-treated biochar demonstrated improved metal-adsorption rate and higher adsorption capacity of heavy metals and other pollutants. Though plasma treatment enhances the electrochemical performance of the biochar, the process requires complex and expensive equipment, and excessive plasma exposure may result in structural damage to the biochar. There is a need to optimize plasma exposure time, conduct thorough characterization, and explore alternative plasma sources to ensure cost reduction and sustainability [8].

Electrospraying is an advanced technique used to modify biochar by dispersing fine droplets of functionalizing agents onto its surface. It involves applying a high-voltage electric field to a liquid suspension containing biochar and functionalizing agents. Voltages ranging from 5–30 kV are applied to the fine droplets of solvents such as ethanol, acetone, and other water-based solutions, to be deposited at controlled flow rates between 0.1–5 mL/h for precise deposition [133]. Depending on the sprayed material, the process introduces OH, COOH, or doped with N, P into the biochar, enhancing its integration of biochar into nanofibrous matrices for energy or environmental applications. This process generates fine droplets that deposit onto biochar, leading to uniform coating and improved surface characteristics. Li et al. [134] carried out simultaneous electrospinning and electrospraying to modify the raw biochar to enhance the electrochemical, adsorption properties of the biochar, and uniform surface modification. The process requires expensive and specialized electrospraying systems, and the inappropriate disposal of spent electrosprayed biochar may trigger environmental issues.

5 Application of Functionalized Biochar for a Green Future

As the world seeks sustainable solutions to environmental challenges, functionalized biochar emerges as a promising tool for advancing green technology. From soil enrichment and carbon sequestration to wastewater treatment and renewable energy storage, functionalized biochar serves as an eco-friendly innovation poised to mitigate climate change while promoting circular economies. Functionalized biochar application areas in achieving a green future include energy storage, environmental remediation, catalysis, and sustainable agriculture (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Pictorial representation of areas of application of functionalization biochar for a green future

5.1 Application for Energy Storage

Energy storage is crucial for maintaining a stable, efficient, and sustainable energy system. It helps balance supply and demand, ensuring that excess energy generated during peak production periods can be stored and used later when demand rises. For renewable energy sources like solar and wind, storage is essential to address intermittency, since the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow. Beyond renewables, energy storage enhances grid reliability, reduces dependence on fossil fuels, and improves energy access in remote areas. It also plays a key role in reducing GHG emissions and promoting a transition to a cleaner, more resilient energy future [29]. Functionalized biochar plays a significant role in energy storage by enhancing the performance of electrochemical devices such as batteries, supercapacitors, and fuel cells. By applying appropriate functionalization techniques such as heteroatom doping, metal impregnation, and chemical activation, biochar gains improved conductivity, porosity, and stability, making it an efficient material for energy storage applications. In supercapacitors, functionalized biochar offers a high surface area and tunable pore structures, facilitating improved charge storage and faster energy transfer. In lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries, it serves as an electrode material, improving cycling stability and charge retention. Additionally, biochar-based materials contribute to hydrogen storage and electro catalysis, supporting sustainable energy conversion processes. Generally, appropriate biochar functionalization technique enhances energy storage application of raw biochar by introducing redox-active functional groups, like OH, COOH, C=O, and heteroatom dopants, that improve surface reactivity, electrical conductivity, and ion-accessibility. Similarly, biochar functionalization treatments like activation, templating, and ball milling increase micro/mesoporosity, facilitating charge storage and ion transport through expanded surface area and tailored pore architecture [135,136].

In a study, Zhou et al. [132] deployed a non-thermal plasma functionalization technique to modify biochar for energy storage. The biochar was activated with KOH at 800°C, resulting in a better surface area, pore volume, and over 30% improvement in the performance of the supercapacitor electrode. The deployment of acid functionalization for the modification of raw biochar manufacture from date seed waste resulted in improved porosity, enhanced surface chemistry, excellent leakage resistance, and congruent heat charging and discharging capabilities, leading to improved thermal energy storage capabilities [137]. Similarly, biochar manufactured from date seeds waste and walnut shells were modified using appropriate functionalization techniques for thermal energy storage applications. It was reported that modified biochar demonstrated improved surface functionalities, porosity, and pore structure, resulting in improved thermal conductivity, better thermal cycling reliability, thermal stability, and excellent thermal storage capabilities [138,139]. Kalidasan et al. [140] in their study impregnated raw biochar constructed from coconut shell with polyethylene glycol for energy storage applications. The energy storage enthalpy of the modified biochar rose from 141.2–150.1 J/g while the thermal conductivity increased by over 114%. Other case studies of the application of functionalized biochar for energy storage applications are summarized in Table 5. Most researchers agree that the implementation of appropriate functionalization techniques improves thermal conductivity, latent heat storage capacity, and long-term durability, making modified biomass-derived biochar a promising material for sustainable energy storage applications.

5.2 Application for Environmental Remediation

Increased human and industrial activities have exacerbated environmental degradation, resulting in massive releases of pollutants, disrupting the ecosystem, and impacting human health. Environmental remediation is essential for restoring the ecosystems, protecting human health, and safeguarding the environment from pollution and contamination. It addresses issues like soil degradation, water pollution, and air contamination, ensuring that affected areas can be restored for safe use. Functionalized biochar is a powerful tool for environmental remediation, offering enhanced capabilities for removing pollutants from soil and water. By modifying biochar with specific functional groups, researchers have improved its adsorption properties, making it more effective in capturing heavy metals, organic contaminants, and excess nutrients [144,145]. Functionalized biochar can efficiently remove heavy metals, organic pollutants, and excess nutrients from wastewater. Remediation of contaminated soil can be achieved by the application of functionalized biochar to remove pollutants, thereby improving soil health and boosting agricultural production. pollutants. Effluents from fuel combustion, industrial processing, and open burning lower air quality, reduce visibility, and impact human health, can be captured and removed by functionalized biochar [129,146]. Shafawi et al. [98] report that some functionalized biochar can be specifically designed to capture and store CO2, contributing to environmental remediation and climate change mitigation. Generally, biochar derived from crop residues adsorbs pollutants from contaminated soil and wastewater through multiple physicochemical mechanisms, including pore-filling, electrostatic interactions, and ion exchange processes. Biochar’s high surface area and porous structure facilitate the physical entrapment of contaminants, while the presence of surface functional groups such as carboxyl and hydroxyl moieties facilitates chemical binding and ion substitution with heavy metals, organic compounds, and other pollutants [147,148]. These mechanisms collectively contribute to biochar’s effectiveness in environmental remediation applications. In general terms, deployment of appropriate biochar functionalization techniques enhances environmental remediation by increasing porosity through chemical activation and templating, which create micro and mesopores that improve contaminant diffusion and adsorption capacity. At the same time, the introduction of surface functional groups such as COOH, OH, NH2, and heteroatom dopants, like N, S, P, etc., boosts surface reactivity and enables specific interactions such as ion exchange, complexation, and redox reactions with heavy metals and organic pollutants [146,148].

Raw biochar constructed from wood chips was modified by the addition of TiO2 for the removal of quinolone antibiotics from wastewater. The functionalized biochar showed improved surface chemistry and porosity, leading to enhanced adsorption capacity and degradation efficiency of 88.4% [149]. A study by Ijaz et al. [150] demonstrated how raw biochar constructed from pine waste (Pinus gerardiana) was modified by heteroatom doping for the removal of methyl blue and lead (II) from complex wastewater. As a result of the modification, the surface area of the functionalized biochar increased from 90–164 m2/g, leading to better adsorption capacity and 96.2% pollutant uptake efficiency. A similar study by Yang et al. [151] modified walnut shell-derived biochar with Fe and Zn for the removal of Pb(II) from wastewater. The impregnation of raw biochar with Fe/Zn atoms facilitates electron transfer by providing additional electrons, while the carbon structure in the biochar doped with Fe/Zn atoms displays substantial adsorption capacity for Pb (II). The influence of the modification by Fe/Zn led to increased adsorption capacity from113.00 mg/g for raw biochar to 661.34 mg/g for functionalized biochar. Raw biochar produced from various crop residues, such as corn straw, pinewood sawdust, etc., was modified for the removal of pollutants from contaminated soil. The functionalized biochar showed better surface area, porosity, and active functional groups were effective in the removal of lead and cadmium [152,153] and arsenic and antimony [154], leading to improved adsorption capacity and pollutant removal efficiency. Dissanayake et al. [155] and Chatterjee et al. [156] modified raw biochar manufactured from wood chip biomass for CO2 capture application. The functionalized biochar showed improved surface area, micropore volume, microporosity, and adsorption capacity, which influenced CO2 capture. The modified biochar was regenerated and reused more than 10 times, and demonstrated CO2 adsorption 7–9 times higher than raw biochar. Functionalized biochar stands out among environmental remediation methods due to its high adsorption capacity, cost-effectiveness, and environmental sustainability. Additionally, its surface modifications improve catalytic activity, making it a versatile tool for wastewater treatment, pollutant adsorption, and carbon capture. Compared to other methods, biochar offers a low-energy, reusable, and eco-friendly alternative for long-term environmental remediation. Table 6 shows the summary of the application of functionalized biochar for environmental remediation.

Functionalized biochar has emerged as a promising catalyst for sustainable energy applications, including energy conversion. By modifying its surface chemistry and porosity, biochar can enhance catalytic activity for processes like biodiesel production, water splitting, and fuel cells. Additionally, metal-supported biochar catalysts have shown effectiveness in biorefinery processes, electrocatalysis, and hydrogen evolution reactions. Due to increased attention to sustainable bioenergy, functionalized biochar is gaining attention as a versatile catalyst due to its large surface area, tailored functional groups, and environmental benefits. Biochar generated from crop residues and other biomass can be modified with metals, non-metals, or polymers to enhance catalytic performance. Functionalized biochar can be deployed for biomass hydrolysis and dehydration, esterification and transesterification reactions, and as catalyst supports for biomass pyrolysis, gasification, and bio-oil upgrading [29,157]. Some recent studies have even explored novel techniques for enhancing the surface area and tailoring the surface functional groups of raw biochar to improve its performance and versatility as low-cost and eco-friendly catalysts. Functionalization of biochar enhances the porosity of raw biochar through various techniques, etches the carbon matrix, and generates hierarchical pore structures that improve mass transfer and active site accessibility, making it useful for catalysis applications. The incorporation of raw biochar with heteroatoms such as N, S, P, etc., or metal nanoparticles introduces electron-donating groups and catalytic centers, increasing surface reactivity and enabling specific interactions such as acid-base catalysis, redox reactions, and π-π interactions with reactants [158,159].

Researchers had modified raw biochar manufactured from various crop residues to support esterification and transesterification reactions to enhance biodiesel production. The deployment of metal impregnation [160], thermal treatment [161], and acid functionalization [162] techniques to modify raw biochar and turn it into efficient heterogeneous catalysts has been successful in transforming triglycerides into a quality biodiesel yield and enhancing ester content. The combination of high surface area, tunable porosity, and functional groups makes functionalized biochar an efficient and sustainable alternative to conventional catalysts. The modified biochar demonstrates easy separability, recovery, regeneration, reusability, stability, low toxicity, and achieves high biodiesel yield with minimal energy input. To further demonstrate the catalytic application of functionalized biochar, Farooq et al. [163] and Yang et al. [164] deployed different techniques to modify raw biochar manufactured from crop residue. The functionalized biochar demonstrated increased porosity, stability, surface area, and functional groups, better electron transfer, and resistance to carbon deposition, leading to improved hydrogen generation. Zhao et al. [165] and Stasi et al. [166] demonstrated the application of the metal functionalization technique to modify raw biochar as an effective catalyst for the steam reforming of methane. The functionalization process led to high stability, prevented coke formation, and introduced more functional groups to promote the dispersion of the catalyst for steam reforming and hydrogen production, causing high conversion efficiency. In their separate studies, Li et al. [167] and Lee et al. [168] modified raw biochar produced from crop residues to catalyze chemical reactions. The functionalized biochar demonstrated high surface area, excellent catalytic performance, tunable porosity, and rich functional groups, leading to the production of high-quality tetrahydrofuran and 1,4-butanediol. Table 7 summarizes the outcome of the application of functionalized biochar for catalysis.

5.4 Application for Sustainable Agriculture

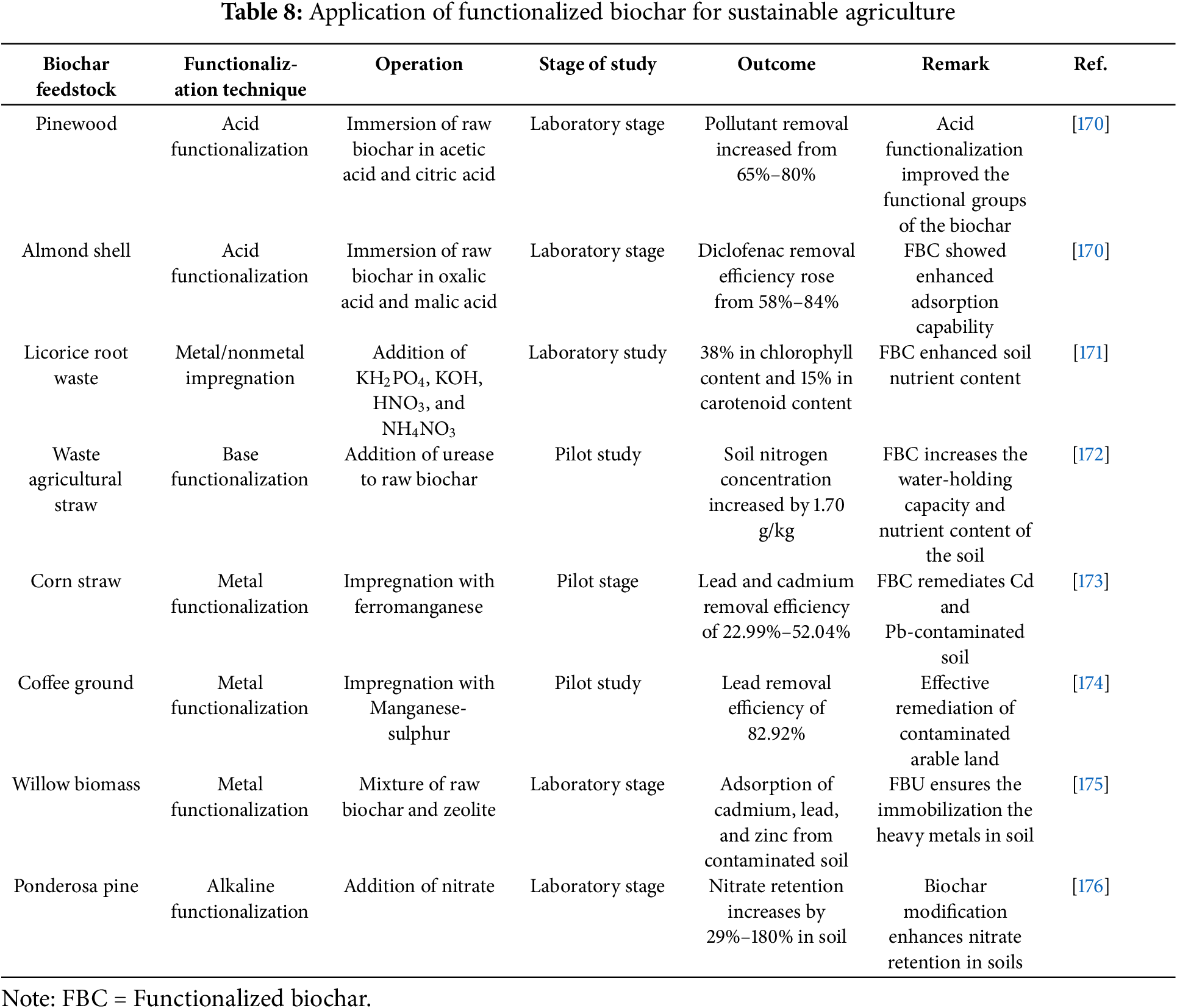

Functionalized biochar has significant applications in sustainable agriculture, offering multiple benefits for soil health, crop productivity, and environmental conservation. Raw biochar can also be modified for other special applications such as pH regulation, pest and disease suppression, water management, and microbial activity enhancement. Functionalized biochar manufactured from crop residues helps to improve soil fertility, enhance nutrient retention, and reduce soil contamination, thereby contributing to sustainable agriculture [44,169]. In a study, raw biochar generated from pinewood and almond shells was functionalized by organic acids for the adsorption of pollutants. The functionalized biochar showed improved surface area, porosity, and better micropore structure for the removal of diclofenac from contaminated soil [170]. The application of functionalized biochar as a soil conditioner to increase soil nutrients, enhance plant growth, and maximize crop production was investigated. Biochar produced from licorice root waste was modified with the addition of KH2PO4, KOH, HNO3, and NH4NO3 to regulate soil pH and improve nutrient content. The modification of biochar with nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium led to excellent slow-release nutrient carrier material, improved nutrients in the soil, and better plant growth [171]. Similar study by Gao et al. [172] on the effect of the addition of urease to modify raw biochar on the soil nutrient, water holding capacity, and plant growth. The outcome of their study revealed that functionalization of raw biochar increases the soil nitrogen concentration, lowers ammonia loss, and ensures higher nitrate content. The impregnation of raw biochar produced from corn waste with ferromanganese aids the removal of lead and cadmium from contaminated soil and inhibits the accumulation of heavy metals in wheat grain [171]. The deployment of appropriate functionalization technique for raw biochar modification enhances porosity, ensures chemical activation and structural tailoring, which increases water retention, aeration, and nutrient accessibility in soil matrices. The introduction of surface functional groups and nutrient-enriched moieties including COOH, NH2, and NPK compounds, improves cation exchange capacity and fosters specific interactions with soil microbes and plant roots, thereby promoting nutrient cycling and crop productivity and accelerating sustainable agriculture [169,173]. Other applications of functionalized biochar in sustainable agriculture are summarized in Table 8.

6 Future Trends and Innovations

Functionalized biochar is set to play a pivotal role in sustainable development, with exciting innovations shaping its future. To ensure continuous relevance and expand application areas of biochar, there is need for increased research and innovations, leading to cost-effectiveness, eco-friendliness, and sustainability.

6.1 Advanced Biochar Production and Functionalization Techniques

Development of new techniques like low-temperature pyrolysis and gasification to improve efficiency, ensure scalability, and integration of more readily available waste streams into the feedstock basket will revolutionize biochar production. The effectiveness of biochar modification can be improved by developing novel, hybrid, low-energy consumption, and eco-friendlier functionalization techniques. Integration of automation and digital monitoring systems into biochar production and modification will ensure consistent quality, reduce energy consumption, and promote sustainability.

6.2 Expand Functionalized Biochar Application Areas

There is an urgent need to expand biochar application beyond water treatment, agriculture, biodiesel production, pollution remediation, and energy storage. The integration of biochar into the construction industry as green building materials and additives in cement and concrete will reduce construction costs, improve insulation, enhance fire resistance, lower emissions from construction activities, and significantly reduce carbon footprints. In the textile and garment industry, functionalized biochar can be explored for antibacterial fabrics, fire and safety applications, and in dye adsorption to reduce wastewater pollution [177]. Integrating functionalized biochar into food packaging and preservation as a biodegradable material will extend shelf life, absorb moisture, and prevent spoilage. The high surface area, excellent adsorption properties, and biocompatibility of functionalized biochar can be explored in the drug delivery systems, wound healing, and tissue engineering in the biomedical sector. In the cosmetics and personal care industries, modified biochar can be incorporated into skin care products for detoxification and oil absorption, as well as for hair care formulations to improve scalp health. Coating seeds with modified biochar can help to maintain seed conditioning, prevent insect infestation, and improve germination rates, while biochar can be used as livestock feed additives to improve digestion and reduce methane emissions, driving agricultural innovations [178,179]. Future biochar formulations in precision agriculture may include embedded sensors that monitor soil health in real time, optimizing nutrient delivery and reducing waste. Functionalized biochar can also be explored as a reinforcement material in biodegradable plastics, enhancing durability while maintaining eco-friendliness.

6.3 Integration of Biochar into Circular Economy

Biochar production and application are viable channels for converting crop residues and organic waste into valuable products, reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers and promoting sustainable farming practices. Functionalized biochar promotes soil regeneration and sustainability by enhancing soil fertility and overall health, water retention, and microbial activity, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers. The conversion of agricultural waste into biochar and bioenergy production from a biochar closed-loop system and in line with the circular economy, to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, minimize waste, and support sustainability. The incorporation of functionalized biochar into wastewater treatment, green agriculture, biodegraded construction materials, and composites supports circular water management, promotes sustainable manufacturing and material reuse, and contributes to resource recovery [180].

Governments and industries are recognizing biochar’s role in circular economy models, leading to incentives and policies that encourage its adoption in carbon credit systems and sustainable development. Biochar’s integration into policy frameworks and market strategies is accelerating the enactment and implementation of policies to promote biochar adoption, focusing on carbon credits, agricultural incentives, and waste management regulations. As governments refine carbon credit regulations and businesses explore new applications, biochar is poised to become a cornerstone of sustainable development, leading to sustained growth in the biochar market.

7 Challenges and Future Research Directions

Functionalized biochar holds immense promise for sustainability, but its widespread adoption faces several challenges. These challenges can be categorized as technical, economic, environmental, and policy regulations. Biochar production and functionalization techniques are costly, consume energy, and require specialized equipment and expertise, making large-scale production expensive. High costs are also incurred during the disposal and management of spent biochar. Governments should subsidize the cost of production and specialized equipment and incentivize biochar producers and users. Biochar properties vary and depend greatly on feedstock, production methods, and pyrolysis conditions. These factors lead to numerous parameters, variation in properties, and inconsistencies in performance. Researchers should develop and adopt optimum production parameters for each feedstock to reduce inconsistencies due to feedstock type and production parameters. Further research is needed to optimize biochar formulations and effectiveness for different industries. Lack of global standards for biochar makes it difficult to ensure uniform quality control and standardization across applications. There is limited awareness among farmers, citizens, and industry players, with many unfamiliar with biochar’s benefits, slowing its integration into mainstream sustainability efforts. Education and policy incentives are needed to increase adoption rates. Biochar’s role in carbon markets is still evolving, requiring clearer guidelines and regulations. Governments need to formulate implementable policies and regulatory frameworks to streamline incentives for biochar-based sustainability projects. Biochar production and modification processes generate air pollutants, while the disposal of spent biochar exacerbates environmental concerns. Implementation of sustainable solutions such as the use of renewable energy, sustainable waste management practices, etc., should be integrated into biochar production, functionalization, and application to minimize environmental impact along the value chain.

The preparation and application of functionalized biochar also raise ecotoxicological concerns that warrant careful evaluation. There is a feasible risk involving metal leaching, particularly when biochar is modified with metals such as Cu, Zn, or Fe to enhance its reactivity. Under variable environmental conditions, especially acidic pH or redox fluctuations, these metals may be desorbed, leading to contamination of soil and aquatic systems and posing toxicity risks to microbial and plant life [181]. Additionally, the long-term stability of surface functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine) is often compromised by microbial degradation, photolysis, or chemical transformations, potentially diminishing the material’s efficacy and releasing previously adsorbed contaminants. Aging processes may also result in the release of dissolved organic matter and biochar-derived nanoparticles, which can alter microbial communities and facilitate pollutant transport. These risks are further influenced by feedstock composition, pyrolysis conditions, and environmental exposure scenarios [182]. Therefore, comprehensive risk assessments, including leaching tests, aging simulations, and ecotoxicity evaluations, are essential to ensure the safe and sustainable deployment of functionalized biochar in environmental matrices.

Apart from the ecotoxicological risks, it is equally important to address the broader challenges, including characterization protocols, logistical issues, regulatory barriers, social acceptance, and impact on the vulnerable in society. A major challenge to the process of biochar functionalization is the absence of standardized characterization protocols, which complicates the comparison of results across studies and hinders regulatory validation. This inconsistency is further exacerbated by the diversity of feedstocks and functionalization techniques, leading to variable physicochemical profiles [29]. Also, from a logistical standpoint, the transportation and storage of biochar are nontrivial due to its low bulk density, hygroscopic nature, and potential fire hazards. Moreover, while functionalized biochar shows promise in biomedical, body care, and food-related applications, regulatory frameworks remain underdeveloped, with unresolved concerns about biocompatibility, purity, toxicity, and long-term safety. Lack of social acceptance also plays a pivotal role, particularly in marginalized communities where skepticism toward novel technologies may be rooted in historical inequities, ancient social biases, or a lack of participatory engagement [40,183]. Without inclusive governance and equitable access, the deployment of such innovations risks reinforcing existing disparities rather than alleviating them.

Emerging tools such as artificial intelligence (AI) and predictive modeling are increasingly instrumental in advancing the functionalization, formulation, and application of biochar. Machine learning algorithms can decipher complex, nonlinear relationships among synthesis parameters, enabling the prediction and optimization of surface area, porosity, and functional group distribution [184,185]. These tools facilitate the design of tailored biochar materials for specific environmental or industrial applications, such as pollutant adsorption or soil amendment. Predictive models also support the selection of optimal feedstocks and pyrolysis conditions, reducing experimental costs and enhancing reproducibility. Furthermore, AI-driven simulations can forecast long-term performance and environmental interactions, aiding in risk assessment and lifecycle analysis [186,187]. Integrating these technologies accelerates innovation and supports the development of high-performance, application-specific biochar systems.

The following research domains are recommended to further explore innovative applications and enhance their efficiency in sustainability efforts.

i. Development of novel and multi-functional biochar composites for diverse specialized applications in biomedical, energy storage, wastewater purification, smart agriculture, cosmetics and body care, and green construction.

ii. Further exploration of biochar’s role in biochar-based fertilizers, seed coating, and precision agriculture with embedded sensors for real-time soil health monitoring and improvement.

iii. Investigate modified biochar application in drug delivery systems for targeted therapies, antimicrobial properties for medical coatings, and wound healing applications.

iv. Multidisciplinary study on modified biochar application for hydrogen production catalysts for clean energy solutions and supercapacitors, and batteries for renewable energy storage.

v. Development and implementation of digital monitoring and smart sensors to track biochar production, modification, and performance in real time, ensuring consistent quality and efficiency.

vi. Study the techno-economic feasibility, environmental impact assessments, life cycle assessment and development of standardized regulations for biochar quality and carbon credit integration for large-scale biochar production.