Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Manufacturing a Biodegradable Container for Planting Plants Based on an Innovative Wood-Polymer Composite

Department of Architecture and Design of Wood Products, Kazan National Research Technological University, Kazan, 420015, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Ksenia Anikeeva. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Eco-friendly Wood-Based Composites: Design, Manufacturing, Properties and Applications – Ⅱ)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(11), 2235-2252. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0128

Received 08 July 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

The use of wood-polymer composites (WPC) based on a polymer matrix and wood filler is a modern, environmentally friendly direction in material science. However, untreated wood filler exhibits poor adhesion to hydrophobic polymers due to its hydrophilic lignocellulose fibers. To address this, ozone treatment is employed to enhance compatibility, reduce water absorption, and regulate biodegradation rates. This study investigates the hypothesis that ozone modification of wood filler improves adhesion to thermoplastic starch, thereby enhancing the physico-mechanical properties and controlled biodegradation of WPCs under compost conditions. A comprehensive analysis was conducted on composites containing untreated and ozonated wood flour, focusing on tensile strength, bending resistance, impact strength, and biodegradation kinetics. Results showed significant improvements in mechanical properties for modified composites: tensile strength increased by 20%–25%, bending resistance by 15%–30%, and impact strength by 15%–20% compared to untreated samples. The optimal composition identified contained 70% ozonated wood flour and 30% thermoplastic starch (70WF/30P), demonstrating excellent mechanical strength (flexural strength of 18–22 MPa), complete biodegradation within 140 days, and operational stability. The study revealed correlations between surface modification, interphase interaction, and biodegradation kinetics, advancing fundamental knowledge of lignocellulosic filler modification methods. These findings are crucial for developing eco-friendly composite materials with applications in biodegradable packaging and agricultural products, offering both scientific insights and practical solutions for sustainable material development.Keywords

Modern trends in the development of biodegradable polymer composites are increasingly focused on creating not only environmentally friendly, but also functionally advanced materials capable of withstanding high mechanical loads. An important achievement in recent years has been the integration of nanoarming agents such as cellulose nanofibers (CNF) and lignin into polymer matrices to increase strength, fracture toughness, and impact resistance.

For example, a recent study by Ghiaskar and Damghani Nouri (2024) [1] presents elastomeric nanocomposites reinforced with CNF and lignin, which demonstrate significant improvements in performance during high-speed impact and quasi-static indentation. The authors showed that adding 3–5 wt.% of cellulose nanofibers and 7%–10% by weight of lignin powder leads to an increase in the modulus of elasticity by 40%–60% and an increase in energy absorption upon impact due to effective crack scattering and activation of deformation mechanisms at the nanoscale. Of particular importance is the established synergy between CNF and lignin: lignin acts not only as a filler, but also as a natural binding agent that improves interfacial interaction and reduces agglomeration of nanofibers.

These results emphasize the importance not only of choosing a natural filler, but also of purposefully controlling its dispersion, distribution in the matrix, and interfacial interactions to achieve high performance properties. Although this work uses a synthetic elastomeric matrix, the reinforcement approach through the combined use of lignocellulosic components can also be extrapolated to biodegradable thermoplastic systems such as thermoplastic starch-based composites (TPC).

In recent decades, the increased interest in environmentally friendly materials has stimulated the development of research in the field of biodegradable composites. According to literature data, interfacial adhesion in systems based on wood flour and biopolymers such as thermoplastic starch can be less than 0.8–1.2 MPa, which is significantly lower than in modified systems using surface treatment [2]. Wood-polymer composites (WPC) based on thermoplastic starch (TPS) and wood filler are a promising alternative to traditional plastics, especially in agriculture and the packaging industry. However, the key problem remains low adhesion between the hydrophilic wood filler and the polymer matrix, which worsens the mechanical properties of the material. To solve this problem, methods of modifying the surface of wood particles are used, such as ozonation, chemical treatment and thermal activation. The main aspect for creating a high-quality WPC with high operational and physicochemical properties is the selection and modification of the wood filler. One of the key areas in the field of WPC creation is the physicochemical modification of the wood filler to increase adhesion to the polymer matrix. According to a number of authors, the main problem is the poor compatibility of hydrophilic wood with hydrophobic thermoplastic matrices such as polyethylene or polypropylene [3,4]. Correct processing of the wood component of the biocomposite can significantly improve its compatibility with the polymer matrix and enhance the characteristics of the final material. In their study [5], Galyavetdinov et al. found that untreated wood flour has a number of significant drawbacks: high water absorption (up to 25% by weight), low chemical resistance and weak adhesion to polymer matrices, which leads to a decrease in the performance characteristics of the resulting composite materials.

Thus, in [6], various methods of surface treatment of wood are considered, including alkaline treatment, ozonation and plasma treatment. The authors come to the conclusion that combined approaches give the greatest effect in improving the properties of WPC. Similar conclusions are presented in the study [7], which shows that chemical modification of cellulose fibers can reduce water absorption and improve the mechanical properties of the composite. One of the main difficulties in creating effective wood-polymer composites is the need to maintain the environmental friendliness of the material while ensuring high performance properties. The difficulty lies in the fact that most traditional modification methods require the use of chemical reagents that can be toxic or contradict the principles of “environmentally friendly materials” [8]. In addition, there is a problem of scalability of laboratory methods for industrial production. Some authors point out that, although many technologies show good results in laboratory conditions, their implementation on an industrial scale is difficult due to high energy consumption and the complexity of controlling the process parameters [9,10]. Another urgent task is to predict the behavior of the composite under various operating conditions, especially under conditions of high humidity, temperature changes and the effects of microorganisms [11,12].

Most foreign studies are focused on the use of innovative modification methods, such as the use of ionic liquids, nanocells, photocatalytic processes and bioenzymes [13,14]. For example, in [15] a method for modifying wood fibers using enzymes is proposed, which allows preserving the structural integrity of the fiber and improving its compatibility with the matrix without the use of chemical reagents.

One of the effective methods for improving the properties of wood filler is its ozonation. As studies have shown [16], ozone treatment leads to the formation of carbonyl and carboxyl groups on the surface of wood fibers, which increases their polarity and improves interaction with the polymer matrix. Similar results were obtained in [17], where two-stage modification (heat treatment and ozonation) made it possible to reduce the water absorption of the composite by 40%–50% and increase its strength by 20%–30%. These data are consistent with the findings of [18], which note that chemical activation of the surface of wood flour is critically important for creating materials with desired properties.

Thermoplastic starch obtained by plasticization with glycerin is widely used as a biodegradable matrix for WPC. Its advantages include availability of raw materials, low cost, and complete biodegradability [18]. However, TPC has low mechanical strength and high hydrophilicity, which limits its application. To overcome these disadvantages, researchers propose combining TPC with reinforcing fillers such as wood flour [19]. The optimal ratio of components (70% wood flour and 30% TPC) provides a balance between strength and biodegradation rate.

Studies of the mechanical properties of WPCs demonstrate that modification of the wood filler significantly improves tensile strength, bending strength, and impact toughness [18]. For example, ozonation increases the tensile strength by 20%–25% compared to untreated samples [18]. In addition, the rate of biodegradation of composites with modified wood flour is higher, which is associated with improved surface accessibility for microorganisms [16]. The complete decomposition cycle of such materials takes 140 days, which makes them suitable for the production of biodegradable containers.

Recent studies highlight the growing demand for sustainable composite materials in agriculture. Pandey et al. [20] provide a comprehensive review of natural fiber-reinforced composites for agricultural applications, emphasizing the importance of biodegradability, mechanical performance, and cost-effectiveness. The authors identify biocomposites based on starch, cellulose, and lignocellulosic fillers as promising candidates for products such as planting containers, mulch films, and seed tapes. In this context, our work aligns with current trends by developing a fully biodegradable wood-polymer composite based on thermoplastic starch and ozonated wood flour. The use of ozone treatment as a green modification method distinguishes our approach from chemical treatments involving toxic reagents, while ensuring improved interfacial adhesion and controlled decomposition kinetics—key requirements for agricultural applications.

Modern research in the field of WPCs is aimed at finding new methods for modifying fillers and optimizing the composition of composites. For example, studies [19,21–23] emphasize the importance of using secondary resources and sustainable production processes. A promising direction is also a combination of different types of treatment (chemical, thermal, plasma) to achieve the maximum effect [16]. The aim of this work is to study a wood-polymer composite based on thermoplastic starch and two types of wood filler to determine the performance properties of the material, which is subsequently used to manufacture biodegradable containers for planting closed-root plants. The tasks that must be completed to achieve this goal are as follows:

1. It is necessary to manufacture pilot samples of the wood-polymer composite.

2. Study the tensile and bending strength of the obtained samples.

3. Determination of the impact strength of the material.

4. Determination of the optimal composition of components for the manufacture of biodegradable containers.

5. Manufacturing biodegradable containers.

6. Study the rate of biological decomposition of the obtained containers.

In this study, a wood-polymer composite was manufactured based on wood flour obtained from wood processing waste and thermoplastic starch. Thermoplastic starch (TPS) was obtained by plasticizing corn starch 30 wt.% glycerin at 130°C for 7 min on Brabender equipment. The use of glycerin as a plasticizer ensures sufficient mobility of the chains and the formation of a thermoplastic matrix suitable for processing by pressing. Wood flour is obtained from waste sawn pine (Pinus sylvestris). The particles were sieved through a sieve with a mesh size of 1–2 mm, which ensured the uniformity of the fractional composition. The resulting material is characterized by a high degree of grinding, uniformity of structure and increased specific surface area, which makes it a promising filler for polymer and composite materials. To manufacture WPC, sawmill secondary wood resources of two types were used as a filler: untreated and ozonized (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Samples of fillers: (a) untreated; (b) ozonation for 120 min, ozone concentration 40 mg/L, temperature 40°C

The mixing of the wood-polymer composite material components took place in the Measuring Mixer 350E chamber of the Brabender PLAsti-Corder Lab-Station mixing equipment, for 7 min at a temperature of 130°C and a rotor speed of 30 rpm. The resulting mixture was subjected to rolling through UBL-6175 laboratory rollers with a gap of 4 mm; the resulting material is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Resulting sample of composite material

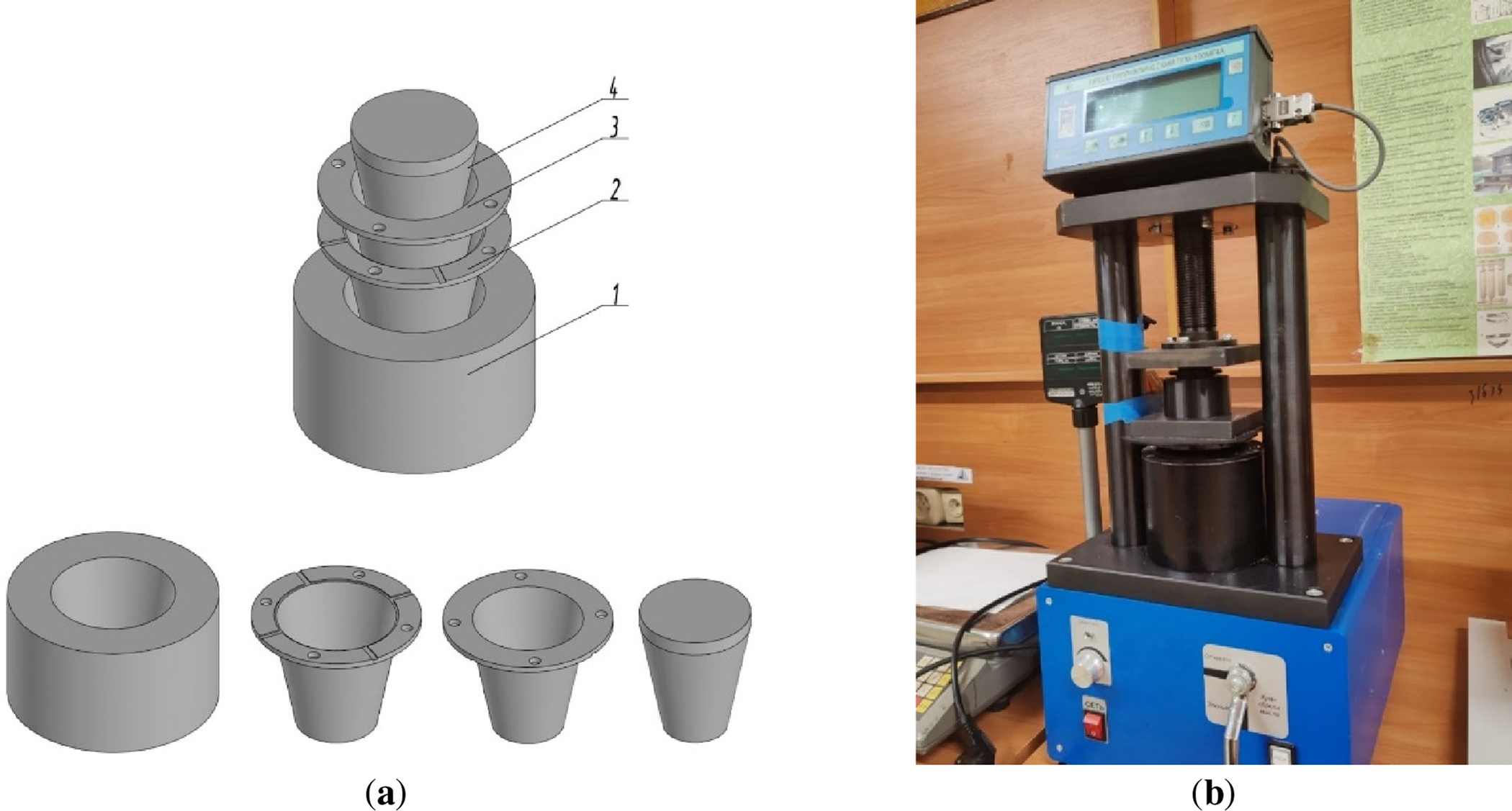

To produce experimental samples of biodegradable containers, a mold was designed and manufactured (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3: A mold for casting biodegradable containers: (a): 3D model, where: 1—base; 2—lower part of the mold; 3—upper part of the mold; 4—punch; (b): External appearance of the mold for casting biodegradable containers

The principle of operation of the mold is to heat the base 1 and punch 4 to a temperature of 170°C, load the wood-polymer composite between the lower 2 and upper 3 parts of the mold and melt it in the mold for 5 min under a pressure of 70 bar in the press. The appearance of the process is shown in Fig. 1b. After that, the mold is cooled in cold water to room temperature, followed by the extraction of the resulting sample.

The performance properties of the composites were studied on samples obtained by injection molding. To obtain experimental samples, pre-crushed material was loaded into the injection molding machine. Casting took place at a temperature of 160°C and an injection pressure of 8 bar, then samples without defects were selected.

Infrared spectroscopy (IR spectroscopy) is used to study the molecular composition of substances by analyzing their ability to absorb infrared radiation at different frequencies, absorption occurs due to vibrations of various chemical bonds in the sample.

Using IR Fourier spectroscopy, two samples of wood flour were studied: untreated (control sample); subjected to two-stage processing—thermal modification and ozonation. The study was carried out on a Frontier IR Fourier spectrometer (PerkinElmer) using an attenuated total internal reflection (ATR) attachment.

The obtained spectra and wavenumber indicators are shown in the figures. Wavenumbers on the graph are used to identify various functional groups in the molecular structure of the sample based on characteristic absorption zones.

All mechanical tests were carried out five times for each composite composition. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). For each type of sample (untreated and ozonated filler, 5 component ratios), at least 15 blanks were produced, from which the 5 best in quality (without visible defects, bubbles, cracks) were selected for subsequent tests.

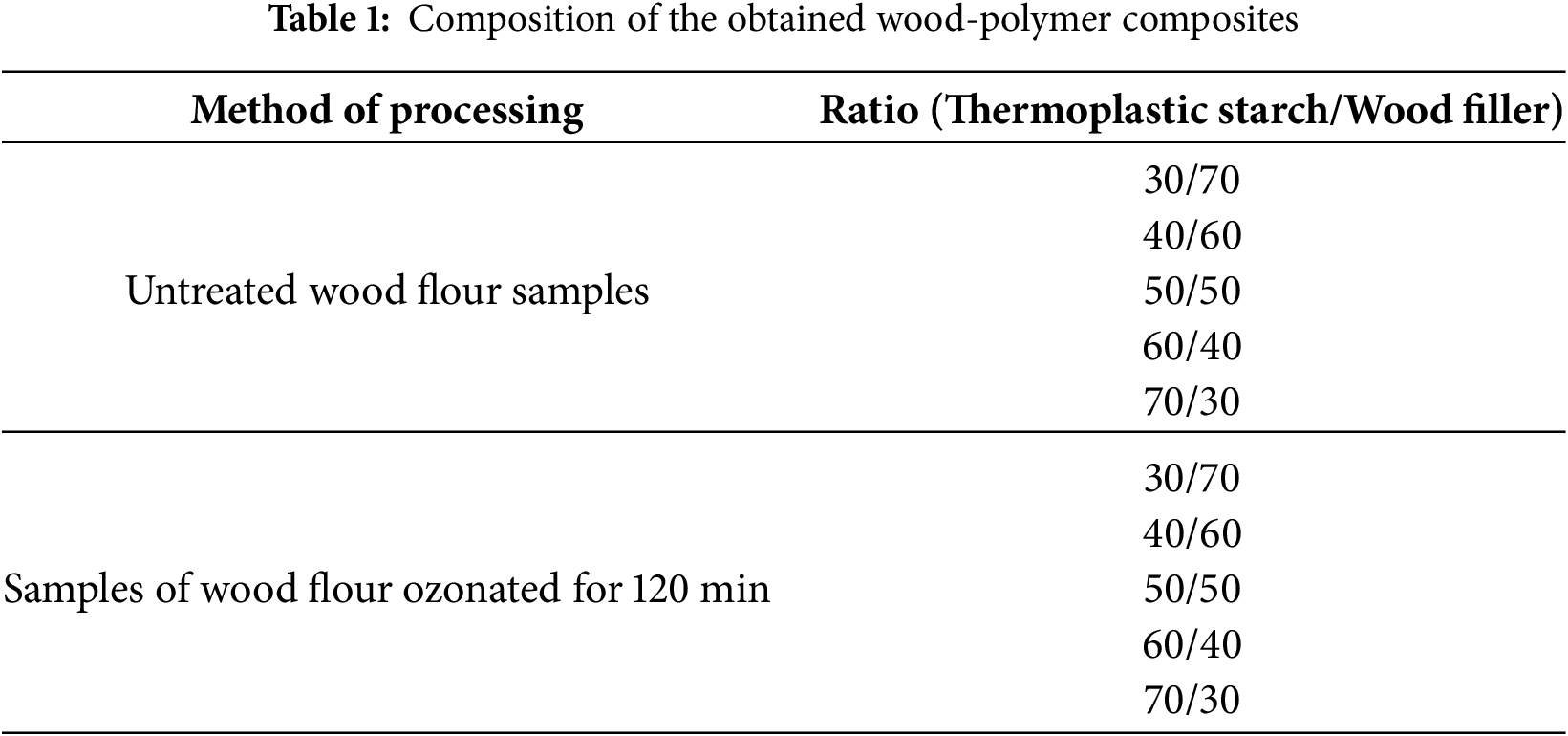

To study the properties of the material and select the optimal ratio of components in the mixture, 10 experimental samples of wood-polymer composite were obtained, their composition is shown in Table 1.

The tensile strength of wood-polymer composites was determined according to the method established in GOST 11.262-2017 on a two-column universal testing machine of the GOTECHAl-7000M series with a 5 kN sensor, a distance between clamps of 60 mm. The test samples were stretched at a constant tensile speed of 50 mm/min until rupture.

The Izod impact strength was determined according to GOST 19109-2017 on a pendulum impact tester GT-7045-MDL, at a temperature of 22°C. The samples were destroyed under the action of a pendulum with an impact energy of 5.5 J and a movement speed of 3.46 m/s and an incidence angle of 150°.

Studies to determine the biodegradation rate of wood-polymer composite were conducted in accordance with the requirements of GOST R 57225-2016. Wood chips were mixed with cattle excrement, 65% water, sea sand and vermiculite. The samples were weighed, placed in a container with compost for 180 days, after which the material was weighed again and the biodegradation rate was calculated. Composting temperature: maintained in the range of (58 ± 2)°C for the first 14 days (thermophilic decomposition phase), then decreased to (30 ± 2)°C. The pH of the medium was measured weekly and averaged 7.2–7.8. Ventilation: was provided by daily stirring of the samples in the compost. The samples (50 × 50 × 2 mm) were weighed to an accuracy of 0.001 g before being placed in compost and removed for weighing through 14, 28, 56, 84, 112, 140 and 180 days.

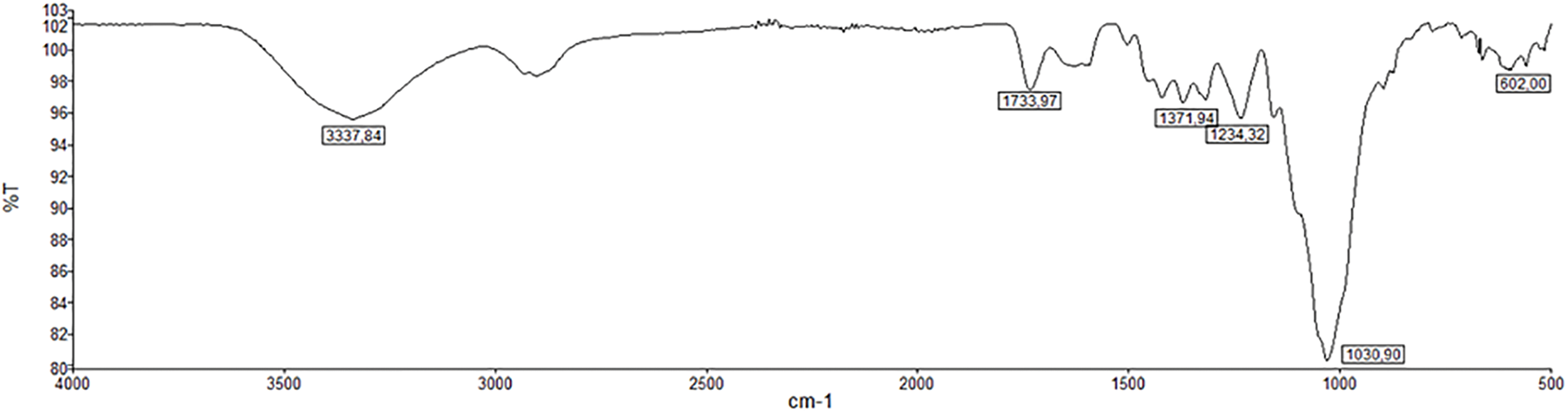

Fig. 4 shows the infrared spectrum of the ozonized wood flour sample. Based on the analysis of the peaks in the graph, it can be concluded that the peak around 3337 cm−1 reflects vibrational movements of the O-H bonds, which may reflect water, phenols, alcohols or acids. This peak is relatively broad, which is characteristic of vibrations of the bound forms of hydroxyl groups, possibly due to hydrogen bonds.

Figure 4: Infrared spectrum of the ozonized wood flour sample

The peak at 1733 cm−1 corresponds to C=O stretching characteristic of carbonyl groups of aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids and esters. Ozonation may have led to the formation of additional carbonyl groups in the structure of pine flour.

The peak near 1371 cm−1 may correspond to C-H bending vibrations in methyl and methylene groups. In the range of 1370–1234 cm−1 there may be bands associated with various bending and stretching vibrations in the molecular structure of wood. The peak near 1234 cm−1 may be associated with C-O vibrations.

The sharp peak at 1030 cm−1 is associated with vibrations of Si-O or C-O bonds, depending on the chemical composition of the sample.

The peak at 602 cm−1 may be characteristic of bending vibrations of bonds in aromatic rings or with other heavy atoms in the molecule. Under the influence of ozone, wood flour, consisting of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, undergoes complex oxidation processes that lead to significant changes in the chemical composition and structure of its components. Ozonation affects each of these components of wood differently: Cellulose is a polymer of beta-1,4-glycosidic bonds between D-glucose molecules. Ozone actively affects the carbon bonds in the cellulose polymer chain, causing them to break. This leads to the formation of fragmented chains with terminal functional groups [24,25]. When carbon bonds are broken, new carbonyl groups (C=O) are formed, which can be detected by peaks in the infrared spectrum at about 1733 cm−1. These groups can be formed as a result of the synthesis of aldehydes or ketones. Once carbonyl groups are formed, they can be reduced to alcohols (OH), which explains the broad peak at around 3337 cm−1, characteristic of hydroxyl groups. Hemicellulose is a less ordered polymer containing various monosaccharides such as gellan gum, mannan, and others. It is more sensitive to oxidation than cellulose due to the presence of primary and secondary alcohol groups: ozone reacts with the primary and secondary alcohol groups in hemicellulose, converting them to the corresponding carbonyl groups. This process enhances the peak at around 1733 cm−1. Hemicellulose contains many ether groups that can be destroyed by ozonation, which can lead to a change in the peak at around 1030 cm−1, associated with C-O bonds. Oxidation can result in the formation of additional hydroxyl groups (OH), which is also reflected in the peak at about 3337 cm−1.

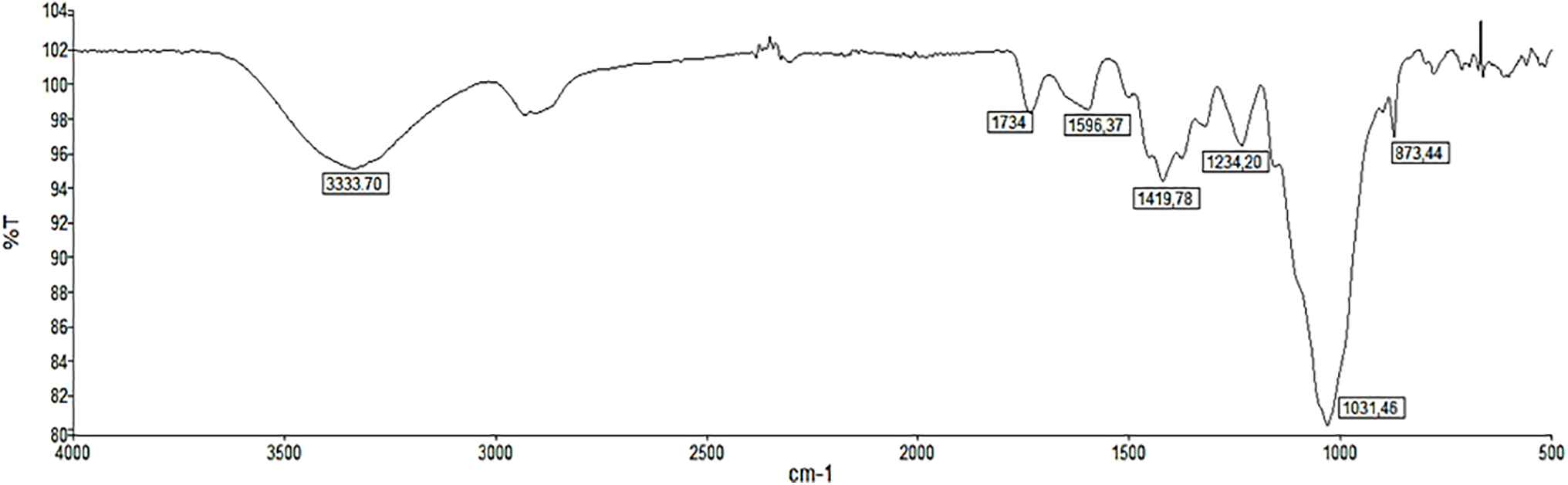

The infrared spectrum of unprocessed wood flour is shown for comparison with the ozonated sample to highlight changes in chemical structure after treatment (Fig. 5). The spectrum exhibits characteristic absorption bands corresponding to the main components of lignocellulosic material. A broad band at 3333.70 cm−1 is attributed to O–H stretching vibrations from hydroxyl groups in cellulose, hemicellulose, and adsorbed moisture. The peak at 1734 cm−1 arises from C=O stretching in carbonyl groups, primarily associated with acetyl and uronic ester groups in hemicellulose or lignin. Absorptions at 1596.37 cm−1 and 1419.78 cm−1 are assigned to aromatic skeletal vibrations of lignin and C–H deformation in cellulose, respectively. The band at 1243.20 cm−1 corresponds to C–O stretching in guaiacyl units of lignin, while the strong signal at 1031.46 cm−1 is due to C–O–C pyranose ring stretching in cellulose. An additional peak at 873.44 cm−1 may be related to β-glycosidic linkages or out-of-plane C–H bending in aromatic structures. These features confirm the presence of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in the unprocessed wood flour and provide a reference for identifying chemical modifications induced by ozonation, particularly in oxygen-containing functional groups.

Figure 5: Infrared spectrum of the unprocessed wood flour sample

Lignin is a complex aromatic polymer that plays a key role in providing the structural strength of wood. Under the influence of ozone, the following processes occur: ozone actively affects the aromatic rings of lignin, causing their partial destruction. However, the aromatic structures are not completely destroyed, as evidenced by the preservation of the peak at about 602 cm−1, associated with bending vibrations in the aromatic rings. The destruction of the aromatic rings leads to the formation of carbonyl groups, which is confirmed by an increase in the intensity of the peak at about 1733 cm−1. Ozonation can cause a rearrangement of the intermolecular bonds of lignin, which can be manifested in a change in the peaks associated with C-O bonds (for example, about 1030 cm−1).

To objectively assess the effect of ozonation on the chemical structure of wood flour, a quantitative analysis of the intensity of peaks in the IR spectra of untreated and ozonated wood flour was carried out. The relative intensity of the peaks was normalized by the C–O peak at 1030 cm−1 (typical for cellulose). It was found that after ozonation:

The intensity of the C=O peak at 1733 cm−1 increased by 68%, which indicates a significant formation of carbonyl and carboxyl groups.

The O–H peak at 3337 cm−1 became wider and increased by 42%, indicating an increase in the content of hydroxyl groups, probably due to hydrolysis and oxidation.

The peak at 1234 cm−1 (C–O in lignin and hemicelluloses) decreased by 23%, indicating partial destruction of hemicelluloses.

The peak at 602 cm−1 (deformation fluctuations of aromatic rings of lignin) decreased by 15%, which confirms the partial destruction of aromatic structures under the influence of ozone.

These quantitative changes confirm that ozonation leads to a deep chemical modification of the surface of wood flour, including oxidation, bond breaking and the formation of polar functional groups, which improves adhesion to the WPC matrix.

Ozonation of wood flour causes complex oxidation of all the main components of wood: cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. This process leads to the rupture of carbon chains, the formation of new functional groups (in particular, carbonyl and hydroxyl), partial degradation of aromatic rings of lignin and the reorganization of intermolecular bonds. These changes significantly modify the chemical composition and structure of wood, which can find application in various technological processes, such as improving the solubility of wood, increasing the reactivity of components or preparing wood for further processing.

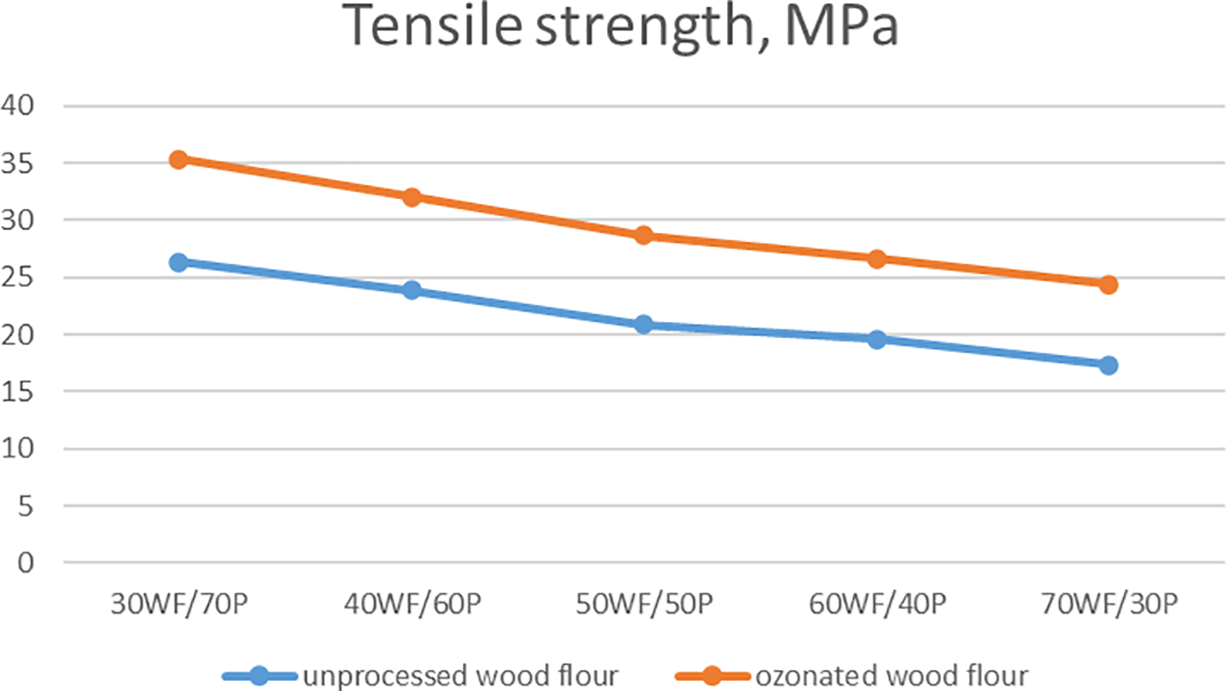

Fig. 6 shows the results of the study of the material for tensile strength.

Figure 6: Dependence of the tensile strength of wood-polymer composite on the composition and type of modification of wood filler

Analyzing the data presented in the graph, it should be noted that with a low content of wood flour in the composite, corresponding to 30%–40%, the polymer matrix provides high plasticity and uniform stress distribution. However, with an increase in the content of wood filler (>50%), agglomerates of particles arise, creating stress concentrators, which leads to premature failure under tension. High wood content (70%) reduces the deformation capacity of the composite, making it more brittle.

Ozonation effectively modifies the wood component within composites by introducing oxygen-containing groups (–OH, –COOH, C=O), thereby enhancing surface polarity. This treatment significantly improves the wettability of the wood fibers by the polymer matrix and reduces their hydrophobicity, which is crucial for achieving compatibility with hydrophilic TPC.

Ozonation increases the tensile strength of the composite, which is facilitated by increased adhesion, is facilitated by increased adhesion, since oxygen groups on the wood surface form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups of the TPC. In addition, there is an improvement in dispersion—chemically modified particles are less agglomerated, being evenly distributed in the matrix. During the action of ozone, the number of voids at the phase boundary also decreases, which increases the load-bearing capacity of the material.

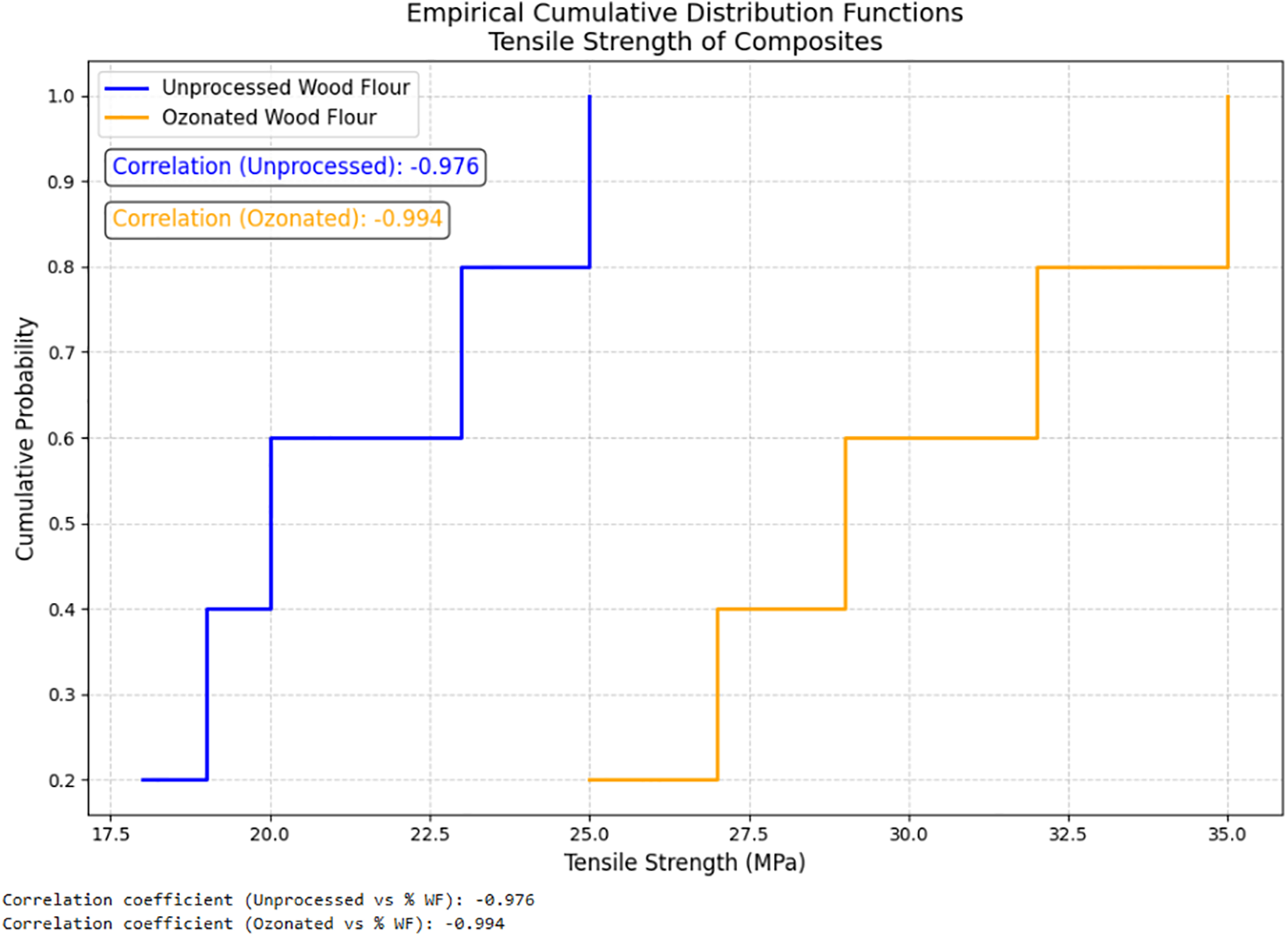

The empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of tensile strength for polymer composites filled with unprocessed and ozonated wood flour are presented in Fig. 7. The ECDF curves illustrate the distribution of tensile strength values across different wood flour loadings (30–70 wt.%). The shift of the ECDF for ozonated wood flour toward higher strength values indicates a significant improvement in mechanical performance compared to unprocessed wood flour. This suggests enhanced interfacial adhesion between the ozonated filler and the polymer matrix, likely due to increased surface polarity and reactivity of the wood flour after ozonation. The strong negative correlation coefficients (r = −0.987 for unprocessed, r = −0.989 for ozonated) between wood flour content and tensile strength confirm a consistent decrease in strength with increasing filler concentration, which is typical for particulate-filled composites due to stress concentration and agglomeration effects. However, the consistently higher strength values for ozonated samples at all loading levels demonstrate the effectiveness of ozonation in mitigating property degradation, making it a promising surface modification technique for natural fiber-reinforced composites.

Figure 7: Empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDF) of tensile strength for polymer composites filled with unprocessed and ozonated wood flour

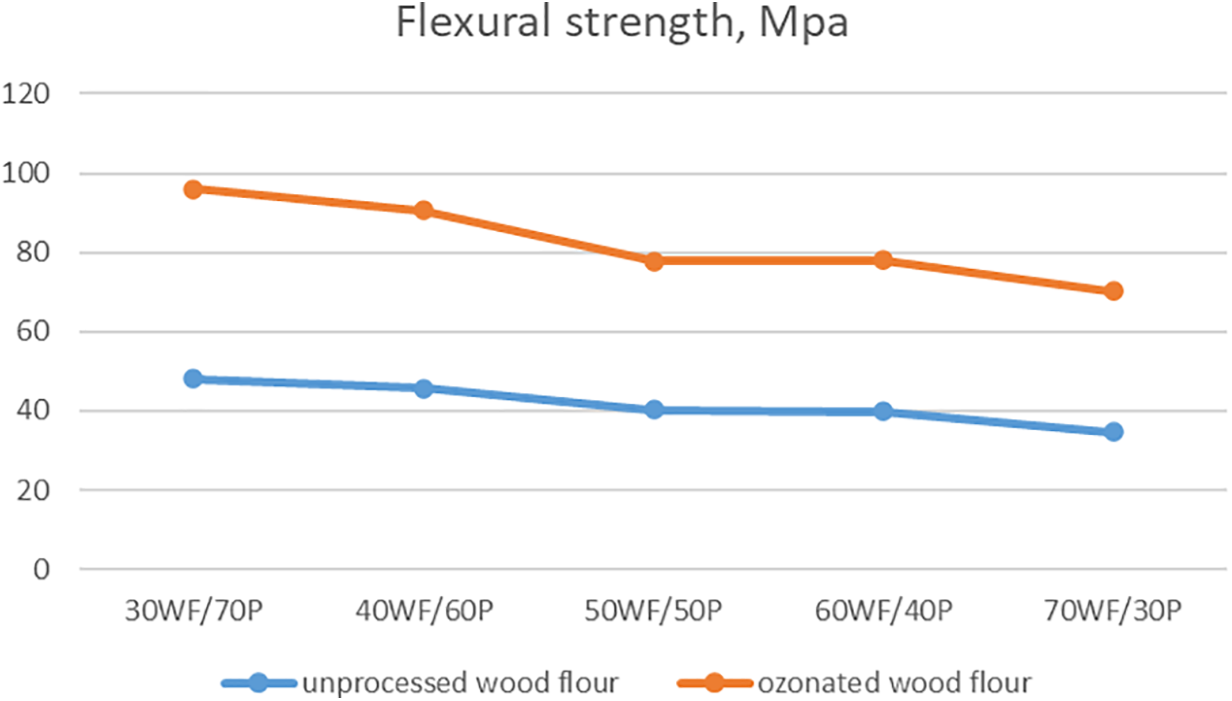

Fig. 8 shows a graph of the dependence of the bending strength of a wood-polymer composite on the composition and type of modification of the wood filler.

Figure 8: Dependence of the bending strength of wood-polymer composite on the composition and type of modification of wood filler

The graph in Fig. 8 clearly shows the fact that the bending strength decreases with increasing wood flour content. This effect is explained by changes in the composite structure. At low wood concentrations, the polymer matrix of thermoplastic starch forms a continuous phase, effectively distributing mechanical stresses. Wood particles act as a reinforcing element, increasing the rigidity of the system without significantly reducing plasticity. However, when the filler content increases above 50%, a qualitative change in the morphology of the material occurs: rigid wood flour particles begin to form their own framework, which leads to the appearance of local stress concentrators. At the micro level, this is manifested in the formation of defects at the phase boundary and a decrease in the material’s ability to redistribute loads. An important aspect is the effect of surface treatment of the wood filler. Ozonation leads to a noticeable increase in strength characteristics in the entire studied range of compositions. This effect is associated with a complex of physicochemical changes at the phase boundary. Ozone treatment induces the formation of active oxygen-containing groups (carbonyl, carboxyl and hydroxyl) on the surface of wood particles, which significantly improves their wettability by the polymer matrix. At the molecular level, this leads to increased adhesive interaction through the formation of hydrogen bonds between the polar groups of the modified filler and the hydroxyl groups of thermoplastic starch. In addition, chemical modification of the surface reduces the tendency for wood flour particles to agglomerate, promoting their more uniform distribution in the volume of the composite.

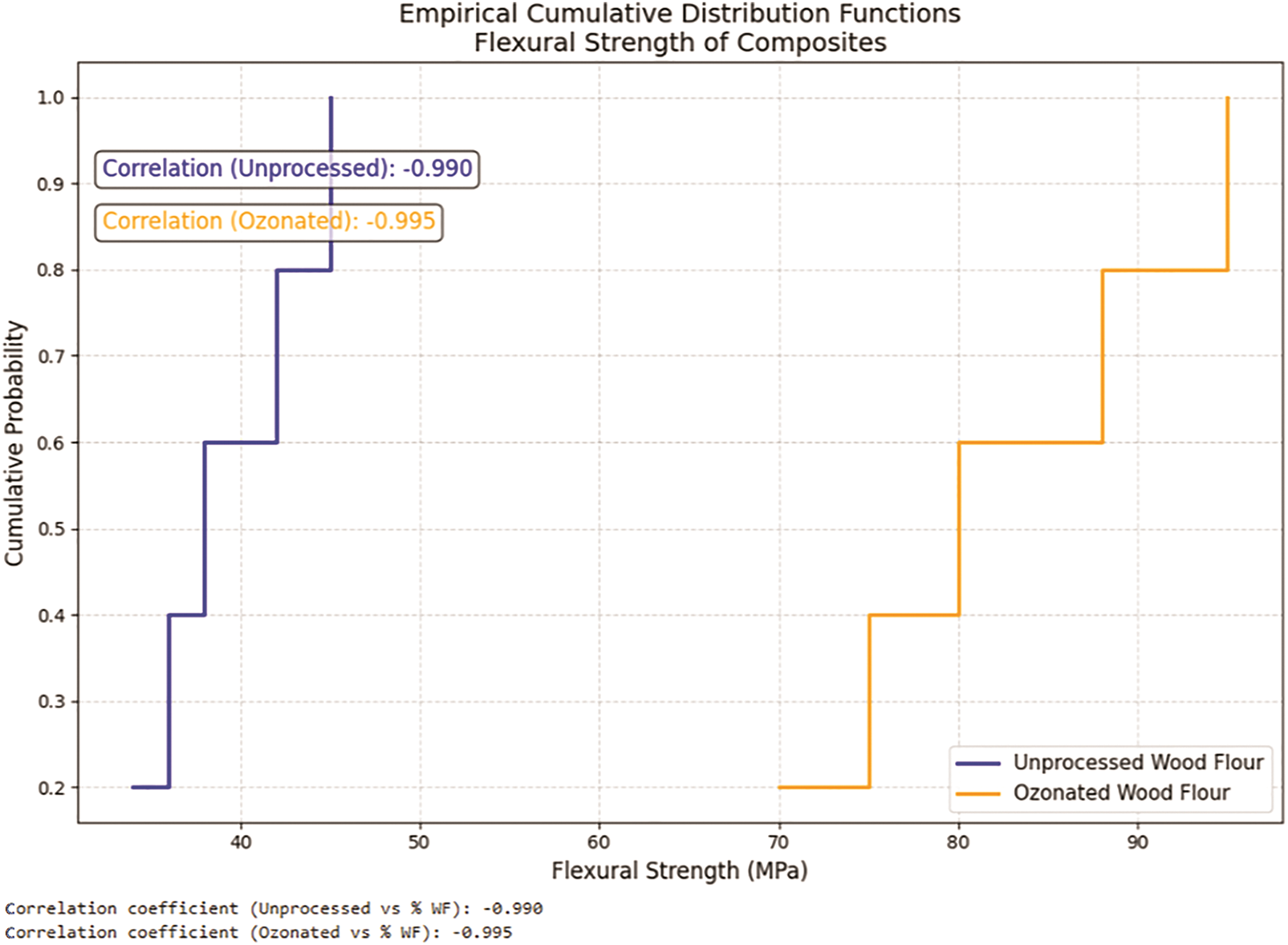

The empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of flexural strength for composites with unprocessed and ozonated wood flour are presented in Fig. 9. The ECDF curves demonstrate that ozonated wood flour composites exhibit significantly higher flexural strength across all loading levels compared to unprocessed counterparts, indicating improved filler-matrix interaction due to surface modification. A strong negative correlation between wood flour content and flexural strength is observed for both materials (r = −0.990 for unprocessed, r = −0.995 for ozonated), reflecting the typical decline in mechanical properties with increasing filler concentration. Nevertheless, the consistently higher strength distribution of ozonated samples highlights the effectiveness of ozonation in enhancing the mechanical performance of wood flour-reinforced polymer composites.

Figure 9: Empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDF) of flexural strength for polymer composites filled with unprocessed and ozonated wood flour

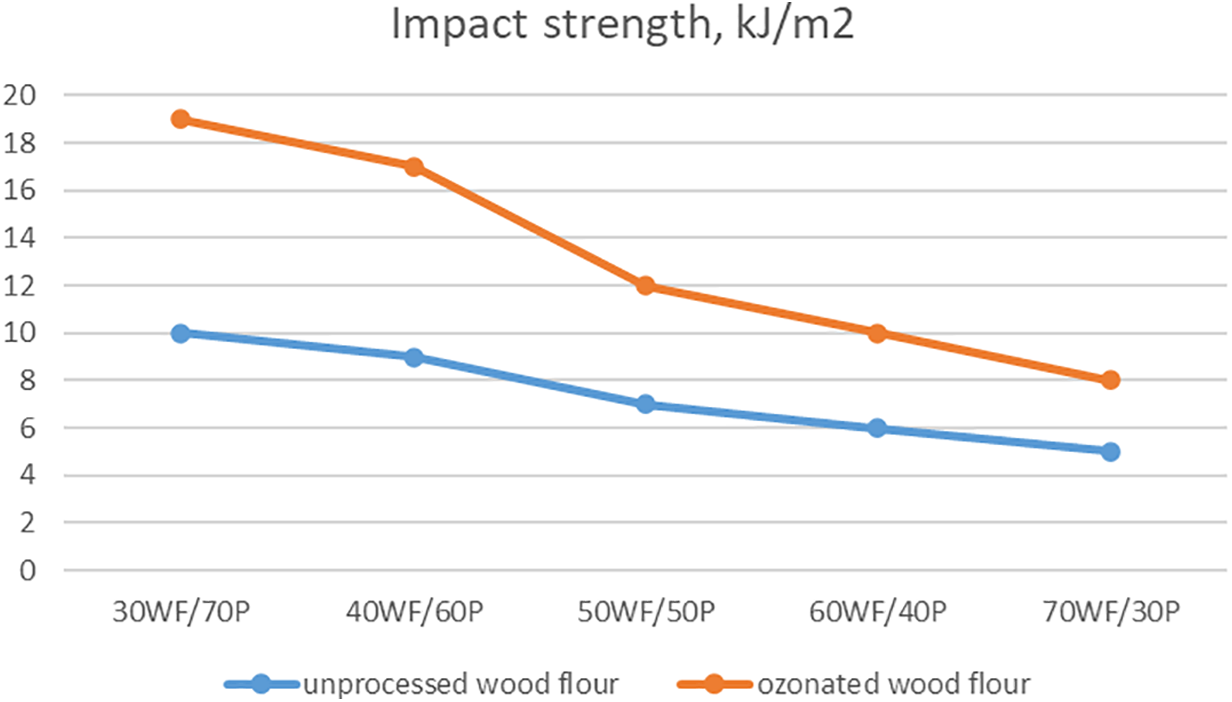

Fig. 10 shows a graph of the impact strength of a wood-polymer composite vs. the composition and type of modification of the wood filler.

Figure 10: Dependence of impact strength of wood-polymer composite on composition and type of modification of wood filler

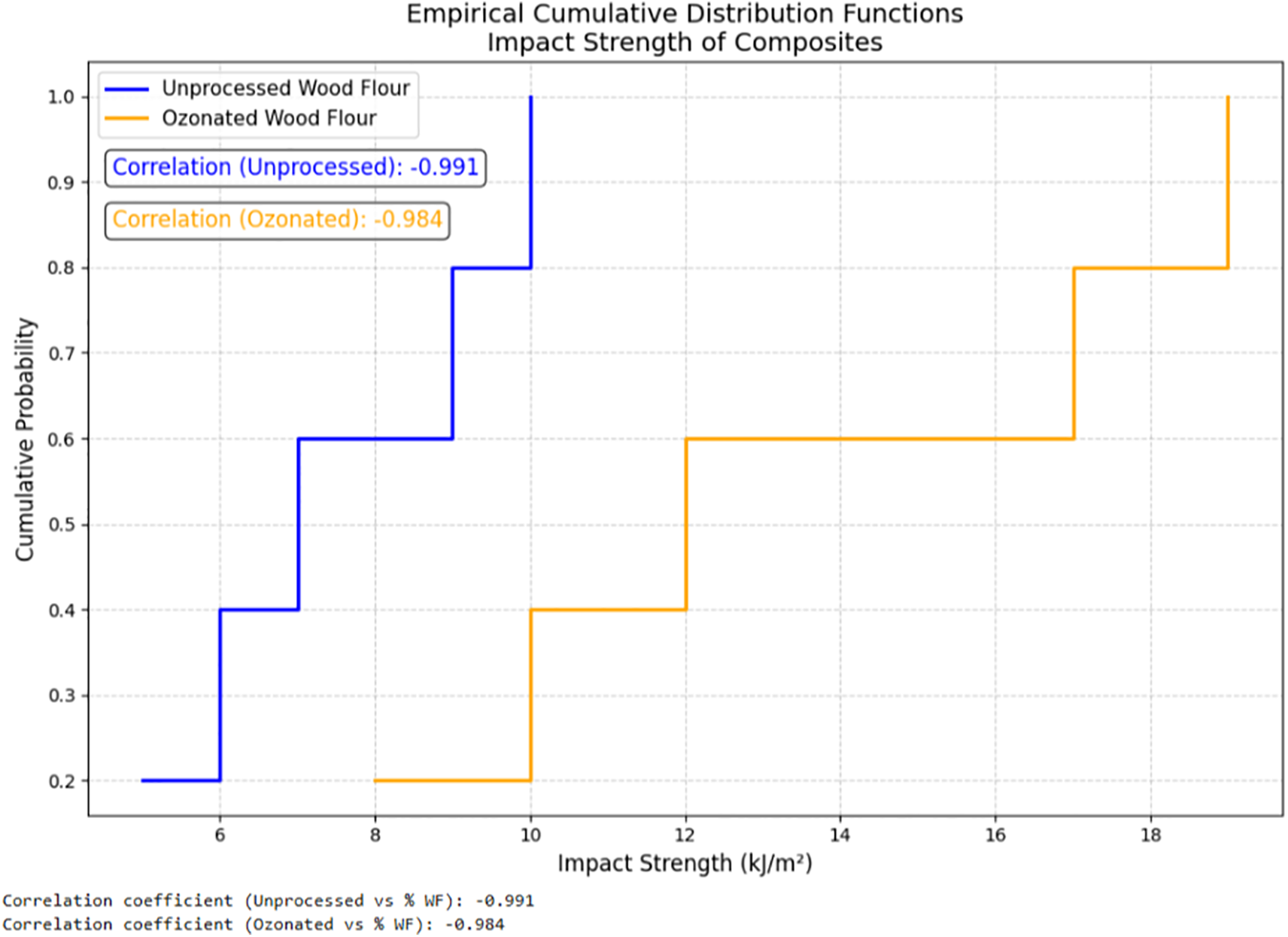

The empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of impact strength for polymer composites filled with unprocessed and ozonated wood flour are presented in Fig. 11. The ECDF curves illustrate the distribution of impact strength values across different wood flour loadings (30–70 wt.%). The ECDF for ozonated wood flour (orange line) consistently exhibits higher impact strength compared to the unprocessed wood flour (blue line), indicating enhanced mechanical performance due to surface modification. This improvement is evident from the shift of the orange curve toward higher strength values. Strong negative correlation coefficients between wood flour content (%) and impact strength (kJ/m²) further support these observations: for unprocessed wood flour, the correlation coefficient is r = −0.991. For ozonated wood flour, the correlation coefficient is r = −0.984. These high negative correlation coefficients confirm a consistent decrease in impact strength with increasing filler concentration, which is typical for particulate-filled composites due to stress concentration and agglomeration effects. However, the consistently higher strength values for ozonated samples at all loading levels demonstrate the effectiveness of ozonation in mitigating property degradation, making it a promising surface modification technique for natural fiber-reinforced composites.

Figure 11: Empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDF) of impact strength for polymer composites filled with unprocessed and ozonated wood flour

When analyzing the dependence of impact strength on the composition of the composite, a nonlinear nature of the change in the indicators is observed (Fig. 11). In the region of low concentrations of wood flour (30%–40%), the material demonstrates relatively high values of impact strength, which is due to the predominance of the polymer matrix, which is able to effectively absorb and dissipate impact energy due to plastic deformation. However, with an increase in the filler content over 50%, a sharp decrease in impact strength occurs, which is associated with a qualitative change in the destruction mechanism. At the micro level, this is manifested in the transition from viscous destruction with the formation of a zone of plastic deformation to brittle destruction with rapid propagation of cracks along the phase boundaries. Of particular interest is the effect of wood flour ozonation on the impact strength of composites. In the entire studied range of compositions, the modified filler provides higher values compared to the untreated analogue. This effect is multifactorial in nature and is associated with profound changes in the structure of the interphase layer. Ozone treatment leads to the formation of active centers on the surface of wood particles, which significantly improves adhesion to the polymer matrix. As a result, under impact, energy is effectively transferred from the matrix to the filler, and the process of crack initiation and propagation is hindered.

It is important to note that under impact loads, not only the absolute strength of the interphase bond is critical, but also the system’s ability to redistribute energy through various dissipation mechanisms. In this context, optimal results are demonstrated by composites with a moderate content (30%–40%) of ozonized wood flour, which combines sufficient filler rigidity with the preservation of the plastic properties of the matrix. The data obtained are of great practical importance for the development of wood-polymer composites with specified impact resistance characteristics. They show that by targeted modification of the filler surface and optimization of the composition, it is possible to significantly improve the material’s resistance to dynamic loads. The conducted studies of the mechanical properties of wood-polymer composites based on thermoplastic starch and wood flour with different ratios of components and methods of filler modification allow us to draw comprehensive conclusions about the feasibility of using the 70WF/30P composition for the production of biodegradable planting containers. Analysis of three key characteristics—tensile strength, bending strength and impact toughness—revealed a general pattern: with an increase in the proportion of wood flour from 30% to 70%, there is a gradual decrease in the plasticity and impact resistance of the material with a simultaneous increase in its rigidity. The highest values of mechanical strength are observed with a wood filler content of 30%–40%, where the polymer matrix still retains the ability to effectively redistribute mechanical loads. Of particular importance is the modification of wood flour by ozonation, which in all the studied compositions provides an improvement in mechanical characteristics by 15%–30% compared to the untreated filler. This effect is due to the formation of active oxygen-containing groups on the surface of wood particles, which significantly improves adhesion to the polymer matrix and promotes a more uniform distribution of the filler in the volume of the material. However, even the modified filler does not fully compensate for the decrease in impact strength and deformation capacity at high concentrations of wood flour (70%).

Despite the fact that optimal mechanical properties are achieved with a wood flour content of 30%–40%, a composition with a ratio of 70WF/30P is preferable for biodegradable planting containers. Thus, the choice of the wood flour-dominated composition (70WF/30P) for the production of biodegradable planting containers is a technically and economically sound solution that provides the necessary balance between performance characteristics and biodegradation rate (Fig. 12).

Figure 12: An experimental sample of the resulting biodegradable container

This solution is based on a comprehensive consideration of several critical factors. Firstly, a high proportion of wood filler ensures accelerated biodegradation of the material in soil conditions, which is a key requirement for this type of product. Secondly, even with a 70% WF content, the material retains sufficient rigidity to maintain its shape during operation, especially when using an ozonized filler, which improves interphase interaction. Thus, the choice of the wood flour-dominated composition (70WF/30P) for the production of biodegradable planting containers is a technically and economically sound solution that provides the necessary balance between performance characteristics and biodegradation rate [25–29].

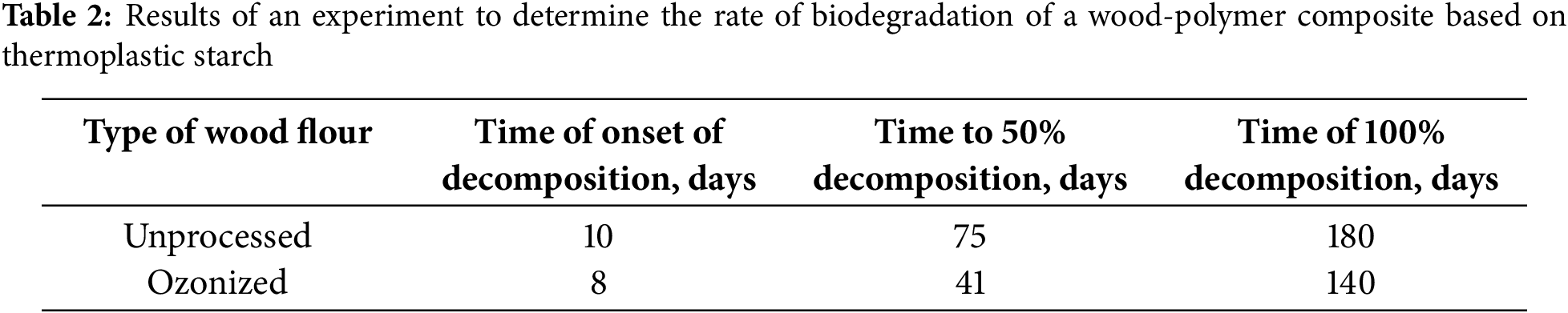

Based on the selected 70WF/30P composition, an experiment was conducted using ozonated wood flour to evaluate the biodegradation rate of the material in a compost medium. Composite samples were placed in a compost medium containing active microorganisms and regularly assessed for weight change. The data obtained during the experiment to determine the biodegradation rate of the material are shown in Table 2.

During the experiment, it was found that the containers began to decompose in the prepared compost after 8–10 days, and the full biodegradation cycle takes 5–6 months, depending on the type of wood filler in the WPC. The treatment of the wood filler significantly affects the biodegradability of the wood-polymer composite, which allows for targeted regulation of its degradation kinetics. Ozonation is an effective method for activating wood particles, which opens up broad prospects for the development of environmentally friendly materials based on natural components.

Analysis of the results showed that the rate of biological decomposition of samples with untreated pine flour was the lowest compared to WPC with treated filler, this is due to the low reactivity of the untreated filler and weak interaction with the composite matrix. During the treatment of flour with ozone, all stages of biodegradation were accelerated by 13%–20%, since ozonation allows the creation of active functional groups on the surface of wood particles (hydroxyl, carbonyl and carboxyl) [3,4], which improves the adhesion between the components of the composite and simplifies the access of microorganisms to biodegradation.

The results obtained can be used to optimize the technologies for creating biocomposites with controlled decomposition times in environmental conditions and open up prospects for the large-scale introduction of biocomponents in agriculture.

The results of the experiment showed that the 70WF/30P composite demonstrates a satisfactory biodegradation rate that meets the requirements for planting containers. By the 12th week of the experiment, the samples lost up to 70% of their original mass, while the degradation process occurred uniformly throughout the entire volume of the material. It is important to note that even at the late stages of decomposition, the material retained sufficient structural integrity to perform its functions as a planting container throughout the growing season.

The data obtained confirmed that the selected composition 70WF/30P not only has acceptable mechanical characteristics for its intended use, but also demonstrates predictable biodegradation kinetics in natural conditions. This allows us to recommend this material for the production of environmentally friendly planting containers that retain functionality for the required service life and are then effectively disposed of in a compost environment without the formation of microplastics or other harmful residues.

The peaks in the region of 1234.26 cm−1 are related to vibrations characteristic of C-O bonds in esters, alcohols and carbohydrates (cellulose, hemicelluloses). During heat treatment, hemicellulose and cellulose decompose, which in turn leads to the rupture of carbon-oxygen bonds C-O in esters and alcohols. The peaks in the region of 873.44 cm−1 are associated with deformation vibrations of carbon-oxygen bonds (C-H and C-O) in the beta-glucoside units of cellulose, as well as with the movements of methyl or methylene groups. At elevated temperatures, thermal destruction of individual cellulose chains occurs, which leads to the destruction of glucosidic bonds (-C-O-C-). Ozonation also leads to the destruction of these bonds with the formation of carbonyl groups, as evidenced by an increase in the intensity of the band in the region of 1317.73 cm−1. An increase in the intensity of the band at the level of 601.51 cm−1 indicates deformation vibrations in the phenolic structures of lignin, occurring during the ozonation process [30].

The experimental results demonstrated a significant improvement in the physico-mechanical properties of composites when using ozonated wood flour. It was established that ozone treatment leads to the formation of carbonyl and carboxyl groups on the surface of wood fibers, which significantly enhances their adhesion to the thermoplastic starch matrix. This is confirmed by a 20%–25% increase in tensile strength, a 15%–30% improvement in flexural resistance, and a 15%–20% enhancement in impact strength compared to control samples containing unmodified filler. The most balanced combination of mechanical properties and biodegradability was achieved with a composition of 70% ozonated wood flour and 30% thermoplastic starch (70WF/30P). This formulation exhibits a flexural strength of 18–22 MPa, meeting the requirements for planting containers, and a complete degradation period of 140 days, making it suitable for agricultural applications.

The study of composite biodegradability revealed a significant influence of wood filler treatment on the material’s degradation rate. It was found that ozonated samples begin to degrade in composting conditions within 8–10 days, whereas untreated counterparts start degrading after 10–12 days. The full biodegradation cycle for the 70WF/30P composite with ozonated flour takes 140 days, which is 40 days faster than for untreated samples. This effect is attributed to the increased hydrophilicity of the wood fiber surface after ozonation, facilitating microbial access to the material.

The practical significance of this work lies in the potential application of the developed formulations for manufacturing biodegradable packaging and agricultural products. Using containers made from this material can address the problem of plastic waste accumulation in agriculture, as they completely decompose in soil without generating microplastics. Furthermore, the use of wood processing waste as a filler reduces production costs and supports the principles of a circular economy. Notably, the selected 70WF/30P composition not only possesses adequate mechanical properties for its intended application but also demonstrates predictable biodegradation kinetics under natural conditions, making it promising for large-scale implementation.

This study contributes significantly to the fundamental understanding of lignocellulosic filler modification methods and the development of new environmentally friendly composite materials. The obtained data expand the knowledge of how filler surface properties influence interfacial interactions in composites and their effects on mechanical performance and biodegradability. The identified patterns can be utilized for designing other types of biodegradable materials with tailored properties.

The developed biodegradable composite based on thermoplastic starch and ozonated wood flour demonstrates promising mechanical properties and a controlled biodegradation rate, making it a suitable material for manufacturing agricultural planting containers. Ozone treatment of the filler significantly enhances the interfacial interaction between wood flour and the polymer matrix, as evidenced by increased tensile, flexural, and impact strength compared to composites with untreated filler. These findings are consistent with studies showing that surface modification of natural fibers improves adhesion and, consequently, the overall performance of composite materials.

The produced containers maintain structural integrity throughout the growing season, which is critical for practical application, and fully decompose in soil within 140 days without leaving microplastic residues. The degradation rate can be tailored by adjusting the degree of ozonation or the matrix composition, enabling material adaptation to different climatic conditions and crop types. The obtained results confirm the potential of the proposed composite as an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional plastic containers in sustainable agriculture.

From a practical standpoint, the successful laboratory-scale performance of this composite highlights its potential for real-world application in horticulture and organic farming, where single-use plastic waste is a major environmental concern. The use of wood processing waste as a filler not only reduces production costs but also promotes circular economy principles by valorizing industrial by-products. However, several challenges must be addressed before large-scale industrial implementation. First, the ozonation process, while effective, requires specialized equipment and controlled conditions, which may increase energy consumption and production complexity. Second, the material’s performance under prolonged exposure to high humidity, temperature fluctuations, and diverse microbial activity in real soil environments needs further validation beyond laboratory tests. Finally, the long-term effects of decomposition products on soil health and plant growth require thorough ecotoxicological assessment. Addressing these limitations will be crucial for ensuring both the functional reliability and environmental safety of the final product.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the Department of Architecture and Design of Wood Products at Kazan National Research Technological University for providing the necessary laboratory facilities and technical support.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Foundation for Assistance to Innovations, under the “Student Startup” competition (agreement No. 3075ГССС15-L/99398 dated 03 October 2024). The grant was awarded to K. Anikeeva. https://fasie.ru/.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ksenia Anikeeva, Ruslan Safin; data collection: Ksenia Anikeeva; analysis and interpretation of results: Ksenia Anikeeva, Ruslan Safin; draft manuscript preparation: Ksenia Anikeeva; critical review and final approval: Ksenia Anikeeva, Ruslan Safin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable. This research does not involve human participants, human data, or animal subjects, and therefore does not require ethics approval.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study. The research was conducted in the absence of any personal, financial, or professional relationships that could be construed as influencing the work reported in this paper.

References

1. Ghiaskar A, Damghani Nouri M. High-velocity impact behavior and quasi-static indentation of new elastomeric nanocomposites reinforced with cellulose nanofibers and lignin powder. Polym Compos. 2024;45(3):2500–16. doi:10.1002/pc.27935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yáñez-Pacios AJ, Martín-Martínez JM. Surface modification and adhesion of wood-plastic composite (WPC) treated with UV/ozone. Compos Interfaces. 2018;25(2):127–49. doi:10.1080/09276440.2017.1340042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rabbi MS, Islam T, Islam GMS. Injection-molded natural fiber-reinforced polymer composites—a review. Int J Mech Mater Eng. 2021;16(1):15. doi:10.1186/s40712-021-00139-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Akter M, Uddin MH, Anik HR. Plant fiber-reinforced polymer composites: a review on modification, fabrication, properties, and applications. Polym Bull. 2024;81(1):80–5. doi:10.1007/s00289-023-04733-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Khan SH, Rahman MZ, Haque MR, Hoque ME. Characterization and comparative evaluation of structural, chemical, thermal, mechanical, and morphological properties of plant fibers. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

6. Galyavetdinov NR, Safin RR, Ilalova GF, Prokopyev AA. Study of physical and mechanical characteristics of biocomposites with wood flour filler. Syst Methods Technol. 2023;3(59):94–9. (In Russian). doi:10.18324/2077-5415-2023-3-94-99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li M, Pu Y, Thomas VM, Yoo CG, Ozcan S, Deng Y, et al. Recent advancements of plant-based natural fiber-reinforced composites and their applications. Compos Part B Eng. 2020;200(2):108254. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Akter M, Uddin MH, Tania IS. Biocomposites based on natural fibers and polymers: a review on properties and potential applications. J Reinf Plast Compos. 2022;41(17–18):705–42. doi:10.1177/07316844211070609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. More AP. Flax fiber-based polymer composites: a review. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2022;5(1):1–20. doi:10.1007/s42114-021-00246-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mahmud S, Hasan KF, Jahid MA, Mohiuddin K, Zhang R, Zhu J. Comprehensive review on plant fiber-reinforced polymeric biocomposites. J Mater Sci. 2021;56(12):7231–64. doi:10.1007/s10853-021-05774-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sathishkumar GK, Ibrahim M, Mohamed Akheel M, Rajkumar G, Gopinath B, Karpagam R, et al. Synthesis and mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced epoxy/polyester/polypropylene composites: a review. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19(10):3718–41. doi:10.1080/15440478.2020.1848723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Das PP, Chaudhary V, Ahmad F, Manral A, Gupta S, Gupta P. Acoustic performance of natural fiber reinforced polymer composites: influencing factors, future scope, challenges, and applications. Polym Compos. 2022;43(3):1221–37. doi:10.1002/pc.26455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Laycock B, Pratt S, Halley P. A perspective on biodegradable polymer biocompositesfrom processing to degradation. Funct Compos Mater. 2023;4(1):10–5. doi:10.1186/s42252-023-00048-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Islam MZ, Sarker ME, Rahman MM, Islam MR, Ahmed AF, Mahmud MS, et al. Green composites from natural fibers and biopolymers: a review on processing, properties, and applications. J Reinf Plast Compos. 2022;41(13–14):526–57. [Google Scholar]

15. Kuram E. Advances in development of green composites based on natural fibers: a review. Emergent Mater. 2022;5(3):811–31. doi:10.1007/s42247-021-00279-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Andrew JJ, Dhakal HN. Sustainable biobased composites for advanced applications: recent trends and future opportunities-a critical review. Compos Part C Open Access. 2022;7(9):100220. doi:10.1016/j.jcomc.2021.100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Safiullina AK, Safin RR, Mukhametzyanov SR, Gulnaz SA, Aigul SR. Ozone processing as a method for increasing adhesional properties of wood. Int Multidiscip Sci GeoConf SGEM. 2020;6(1):403–9. doi:10.5593/sgem2020/6.1/s26.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Timerbaeva AL, Safin RR, Khasanshina RT, Ziatdinov RR. Use of thermal treatment of wood filler in the production of particle boards. Woodwork Ind. 2017;2:54–60. [Google Scholar]

19. Anikeeva KG. The effect of two-stage filler processing on the properties of a wood-polymer composite. Agrar Sci J. 2024;6(6):88–98. doi:10.28983/asj.y2024i6pp88-98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pandey JK, Ahn SH, Lee CS, Mohanty AK, Misra M. Recent advances in the application of natural fiber based composites. Macromol Mater Eng. 2010;295(11):975–89. doi:10.1002/mame.201000095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Anikeeva KG, Kaynov PA, Safin RR, Petrov VI. Effect of physicochemical modification of wood filler on the mechanical properties of biodegradable wood-polymer composite. Woodwork Ind. 2024;3:62–7. [Google Scholar]

22. Sanyang ML, Huda S, Jawaid M, Ibrahim NA, Abdan K. Development of fully biodegradable green composites from thermoplastic starch and nano-fibrillated cellulose: effect of glycerol content on mechanical and water barrier properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;254:127243. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mousavi SR, Zamani MH, Estaji S, Tayouri MI, Arjmand M, Jafari SH, et al. Mechanical properties of bamboo fiber-reinforced polymer composites: a review of recent case studies. J Mater Sci. 2022;57(5):3143–67. doi:10.1007/s10853-021-06854-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ferreira AF, Silva CJ, Soares BG, Aouada FA. Chitosan-modified cellulose nanocrystals for reinforcing polylactic acid biocomposites: enhanced dispersion and interfacial interaction. Polym Test. 2024;130:108298. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2024.108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Biswas K, Khandelwal V, Maiti SN. Mechanical and thermal properties of teak wood flour/starch filled high density polyethylene composites. Int Polym Process. 2019;34(2):209–18. doi:10.3139/217.3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Müller CMO, Laurindo JB, Yamashita F. Effect of cellulose fibers on the crystallinity and mechanical properties of starch-based films at different relative humidity values. Carbohydr Polym. 2009;77(2):293–9. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.12.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chakhtouna H, Benzeid H, Zari N, Qaiss AEK, Bouhfid R. Recent advances in eco-friendly composites derived from lignocellulosic biomass for wastewater treatment. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2024;14(11):12085–111. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-03159-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Espino RR, Mendoza MT, Díaz O. Egradable pots made from agro-industrial waste for nursery plant production: a sustainable alternative to plastic containers. Waste Manag. 2020;118(1):438–47. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2020.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Shah BL, Selke SE, Auras R. Life cycle assessment of biodegradable plant pots made from starch-based composites: environmental impacts and end-of-life scenarios. J Clean Prod. 2023;421(11):138487. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Moritzer E, Richters M. Injection molding of wood-filled thermoplastic polyurethane. J Compos Sci. 2021;5(12):316. doi:10.3390/jcs5120316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools